ABSTRACT

Seeing the potential of goshiwons, Korea’s low-cost single occupancy accommodation, to be a livable and affordable micro-house, this study aims to offer suggestions for future improvements based on the emerging theory of micro-housing. A quantitative approach with structural equation modeling (SEM) was first conducted to test six proposed hypotheses. The first three hypotheses are that there are positive correlations between the current livability of goshiwons and (i) location, (ii) quality of the building and shared facilities, and (iii) room condition. The next three hypotheses emphasize that improving these three physical aspects will improve the degree of livability. An interview qualitative approach to relevant respondents was also applied in which the result further explains the quantitative result. Room conditions that include limited access to natural light, poor air circulation, lack of storage, and poor soundproofing are the main issues for the poor living environment of goshiwon. For future improvements, the location of goshiwon should also be considered as an addition to room condition. This is because, while the location of goshiwons is beneficial in terms of proximity to various facilities, the respondents wished for goshiwons to be located in a quieter and safer environment, away from late-night entertainment establishments.

1. Introduction

Quoting The Korea Herald, one of the most prominent English-language news companies in Korea, goshiwons are defined as “a form of privately owned, low-cost, cocoon-like accommodation, usually larger rooms divided by thin walls and makeshift doors” (Kim Citation2017). The layout of goshiwon establishments can look similar to other single-occupancy housing types such as studios (better known as “one-room” in Korea) and dormitories, but also different in several ways. As shown in , tiny size with usually inadequate furniture, relatively cheap all-in monthly rent with little to no deposit, various shared facilities that can be used for free, and usually strategic location are the main attributes of goshiwons. Starting in the 1970s as an accommodation for students taking the national exam to enter universities, demand for goshiwons rose rapidly and transformed them into long-term accommodation for single occupancy (Jin and Choi Citation2018). Due to their high demand, there have been many variations of goshiwon-type housing, such as goshitel, livingtel, and one-roomtel. All of these offer slightly different quality, and the total of these types of housing surpassed 6,000 units in Seoul and continues to increase (Ryu and Kim Citation2021; Ko, Lee, and An Citation2016). Previous studies have suggested that despite their relatively low spatial quality, demand for goshiwons is still growing (Lee and Yoon Citation2010). Lee Jae Myung, governor of Gyeonggi Province, stated that maintaining goshiwons’ status as an option for low-cost housing in Korea needs to be followed by strict and proper development of regulations about quality (Newsis Citation2021).

Figure 1. The variety of how the interior of goshiwon looks like. Following the site location for this study, picture A was taken at a Goshiwon located in Mapo-gu, picture B was taken in Seongbuk-gu, and picture C was taken in Dongjak-gu area.

Not only to increase the housing supplies, improvement of goshiwons as single occupancy housing can also be beneficial to the general housing welfare in Korea, since it’s expected to expand the housing industry (Lee Citation2021). While developing goshiwons can take various directions and scales, physical aspects of the living environment need immediate attention because they affect residents’ well-being the most (Yeung-kurn, Pan-jun, and Tae-soo Citation2007). Hence, this research focuses on how to improve the physical aspects of the living environment in goshiwon-type housing. Previous studies have analyzed the satisfaction level of goshiwon residents, typology of goshiwons, and assessment of their quality based on Korea’s standard of residential buildings. Hence, the purpose of this study is to assess Goshiwon in a perspective that has never been explored before. We used the concept of micro-housing as the new perspective to present the possible direction for future development due to goshiwons’ physical attributes that are similar to the concept of micro-housing. As of 2021, there is no official and universal definition nor standard for micro-housing besides the etymology of a micro-house being “smaller than regular houses” and, although some cases include multiple occupants, single occupancy is the main target of its development (Batista and Farias Citation2021). Cities around the world such as New York, Boston, Kuala Lumpur, Tokyo, Hong Kong, and within Korea itself have developed their own definitions and specifications of micro-housing. Since every city is unique in population distribution and sociocultural elements, it is important to find the best adaptation of the micro-housing concept for Korea’s housing situation and goshiwons’ characteristics. This study synthesizes the essence of micro-housing concepts from various examples around the world and presents it to goshiwon tenants to first assess the physical components of the current livability of goshiwons, and second, to determine which components are important to improve the livability.

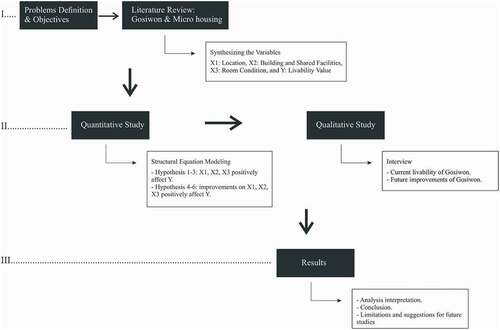

shows the research framework for this study. Three separate but interrelated stages were included. The first stage included defining the research problems and objectives and reviewing literature and cases around the world on the character of micro-housing that is suitable to the context of goshiwons. In this stage, variables used in the study were decided based on the review. In the next stage, the correlation between the independent and dependent variables was investigated twice, once for the current situation and once for improvement suggestions, through quantitative and qualitative approaches. The quantitative approach was conducted to gain general insight on which physical elements affect the livability of goshiwons, while the qualitative approach was used to gain a deeper understanding of the subject. The last stage included interpreting the data analysis, incorporating the results to possible suggestions for future improvements, acknowledging limitations of the current research, and making suggestions for future research. Although the research focuses on one specific housing situation in South Korea, we believed that the results can also contribute to the development of micro-housing in other countries as well, especially in other megacities that have similar issue as Seoul, such as Hongkong, Tokyo, and New York City (Fox and Humphries Citation2021). We tried to incorporate the results in global context in the Discussion section and included the desired impact of our research globally in the Conclusion.

2. Literature review

Research in Korea’s housing prices by Kim and Cho (Citation2010) shows that “achieving the stability of housing prices in all sub-markets simultaneously is a virtually impossible policy goal”. It indicates that stability in housing markets tends to focus on specific markets in which single occupancy households are rarely included, although its number keeps growing yearly. That is one of many reasons why research on single occupancy housings such as goshiwons is very much needed. From a database collected from Google Scholar, 141 studies employing various methods were published in the past 20 years about goshiwons and mostly assessed the living conditions at the time. The first method was to compare the laws and regulations with the actual conditions. Results showed that a lot of goshiwons were operated as other residential types, which is against the law, and that the lack of ventilations and public spaces were the main issues (Yoo, Yang, and Kim Citation2019). Second, through residents’ satisfaction surveys, some negative points were identified. There are many cases where Goshiwons lack of public space where the residents could build some sense of community and have some social activities was highlighted (Cho et al. Citation2017). Surveys also proved that insufficient dining and storge space is also a big issue that needs to be addressed (Choi and Kim Citation2015). For future development, some studies suggest that designing goshiwons differently for each specific user might help improve the occupancy experience (Kim and Yoo Citation2021; Lee and Lee Citation2016). Installation of adaptive furniture that can fit the small size of a goshiwon is also suggested to make the room feel more spacious. Regardless of the low quality of the living environment, many people still chose a goshiwon due to its cheap rent, strategic location, and the availability of free services such as laundry machines and basic meals.

Meanwhile, there are 184 studies on micro-housing research that focus on classifying and identifying micro-house typologies and challenges. Defying the popular trend of big houses as the only acceptable option for a good home, micro-houses are starting to be considered for several reasons. First, they have arisen as one solution to the housing shortage that many megacities face (Harris and Nowicki Citation2020). Housing shortages especially in city centers can lead to more serious problems such as urban sprawl. Urban sprawl imposes a threat to the urban environment because it can create transportation problems and encourage inequality between citizens. Second is the increasing demand for minimalist living and how people see micro-houses as one way to achieve it (Lee and Lee, Citation2014). Various design concepts have also been suggested to make micro-housing livable, such as the focus on sharing resources and the usage of “bespoke design” that emphasizes unique design based on the size of the space (Shearer and Burton, Citation2019) To further understand the planning standard for goshiwons, a review of related laws and regulations is presented next. Design elements of livable micro-housing are also presented to discern which elements can feasibly be implemented in goshiwons.

2.1. Gaps in laws and regulations related to goshiwons

To increase the housing supply, Korea’s Housing Act enacted a new housing type called semi-housing in which non-dwelling facilities are considered to be housing facilities. Generally, semi-housing has four major types: dormitories, elderly welfare facilities, officetel, and goshiwons (Lee and Yang Citation2013). Among these four types, goshiwons are well known to have the worst living environment. There are three main factors that have dragged the living environment of goshiwons below the regular standard (CitationJin et al, Citation2018); Lee and Lee Citation2014):

As of 2021, there is no specific law that regulates the management, design, and minimum requirements of goshiwons. The Semi-housing Act comes closest, and there are other related laws such as the Enforcement Decree of the Building Act, specifically under the Multi-living Facility Building Standards, Special Act on Safety Management of Multi-Use Businesses, and an administrative rule called the Minimum Housing Standards (Jin and Choi Citation2018). This situation has left many gaps in goshiwons’ regulation and has prevented standardization that would guarantee the well-being of the residents.

Having started in the early 1970s, goshiwons were first introduced as study rooms to provide students an enclosed environment to prepare for national exams, such as the university entrance exam and civil servant exam (Lee Citation2020). Since then, the popularity of goshiwons started to increase; slowly their function evolved, and they began to become a regular housing option without a proper adjustment in their spatial design.

Compared to any other accommodations, goshiwons offer the cheapest monthly rent, a very low to no deposit, and a relatively flexible contract (some are available for a one- or three-month contract). Due to the low-cost rental, many physical elements of goshiwons were compromised, and most of the establishments only followed the minimum requirements from one of the related regulations (Lee and Lee, Citation2014).

To further understand the gap in laws and regulations related to goshiwons, a review of the current laws and regulations related to their physical characteristics was conducted, and the summary is presented in . The regulations displayed in are limited to the specifications of the rooms and shared facilities within the goshiwon premises. They exclude regulations of the relationship between goshiwons and other functions within the same buildings and regulations related to the location of goshiwons in general. Due to the confusing laws and regulations that sometimes overlap with each other, many goshiwon owners and managers do not comply with them. Furthermore, because there is no official definition of a goshiwon nor an official classification of them as residential establishments, it is difficult to determine which existing regulation suits goshiwons the most (Park et al. Citation2014). This has resulted in quality disparities in many goshiwons, especially in Seoul. Some goshiwons with higher rental prices have a higher standard and have more features similar to studio apartments, while the ones with lower rental prices tend to have a lower standard.

Table 1. Summary of regulations and laws related to the specifications of goshiwons.

2.2. Micro-housing: providing a living experience within a small space

As stated in the introduction, several countries, including Korea, have attempted to utilize micro-housing to create low-cost housing options or to prevent urban sprawl (Iglesias Citation2014). In Seattle, Toronto, and Tokyo, providing livable micro-housing has been one of the city’s priorities. Studies in micro-housing vary from the limitations of the development and strategies to develop it. The society has so far become both the catalyst and inhibitor of the development of micro-houses. If the minimalist trend in communities is the catalyst of micro-housing growth, funding constraints and oppositional tendency of not wanting micro-houses near their properties are two of the main inhibitors (Jackson et al. Citation2020). The key point in designing a micro-house is how to provide a proper and adequate living space within a very limited space. Even though there are some limitations of a micro-house to offering a full living experience compared to a bigger house, some basic criteria can be met. A good house is one that can accommodate the needs of its occupants. A livable house focuses on its occupants and makes them feel “at home.” While a good design is a subjective matter, there are some basic indicators for a house to be classified as livable.

When staying at a proper house, the occupant(s) is more likely to want to spend time at their home rather than any other place (Streimikiene Citation2015). In the case of micro-housing, the most important indicator of livability is that it offers an environment that allows its residents to perform daily activities without compromising their physical or psychological health (Kim and Yoo Citation2021). To accommodate the aims of this study, cases of designing micro-house from around the world have been studied. Some design features that are possible in goshiwons as single-occupancy housing are highlighted and presented in . While the current laws and regulations related to goshiwons only cover the condition of the rooms and the building, the concept of micro-housing covers the micro, meso, and macro scales of the establishment. The micro scale concerns the condition of the room including its size, the available furniture, its ambience, the air circulation, and the lighting system. The mesoscale deals with the quality of the building, the relation with the other tenants in the same building, and the facilities that goshiwon occupants must share with each other, such as the kitchen and laundry room. The macro scale includes the location of the goshiwons and, most importantly, its proximity to other functions and urban facilities, such as parks, health facilities, and entertainment centers.

Table 2. Summary of spatial characteristics of micro-houses around the world.

As of today, most existing studies on goshiwons are related to the improvement directions and tenants’ motivations in choosing goshiwons as their housing option. However, there is very limited research that focuses on assessing goshiwons with a specific and relevant concept in housing study. Moreover, very limited sources have quantitatively assessed the improvements needed for goshiwons. As a new emerging concept, the current research on micro-housing focuses on the background, characteristics, and controversy surrounding the topic. This study differs from prior research in terms of background theory and the complexity of the methodology. This paper presents the analysis on the current livability and possible future development of goshiwons in multi-scale, as has been suggested by micro-housing principles. The long-term goal of this study is to help decision makers and officials develop policies on how to sustain goshiwons as an option for affordable single-occupancy housing in South Korea.

3. Methods

To conduct a thorough investigation on the issue, this study adopted a mixed-method research design. An exploratory approach with quantitative analysis of subjective data from questionnaires was combined with qualitative analysis of interview data. The main research instruments were a questionnaire with a five-point Likert scale that generated quantitative data and structured interviews that generated qualitative data. Since the key point of mixed-methods study is to link data and reveal how to integrate the data to derive a conclusion (Ivankova, Creswell, and Stick Citation2006), both forms of data were used to complement each other in drawing conclusions. Since the quantitative and qualitative data were complementary to each other, there was no need to collect the data in a specific order, and hence both were done side by side.

3.1. Sample and site location

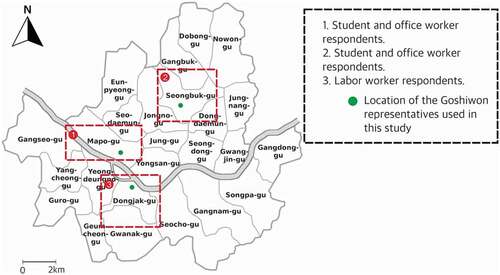

Since almost half of the goshiwons in South Korea are located in Seoul (Bae Citation2019), the focus of this study was the Seoul Metropolitan Area. Moreover, the characteristics of Seoul as a heavily populated and densely built city makes it suitable and purposeful for research related to micro-housing. An earlier study stated that graduate students, office workers, and labor workers account for most goshiwon occupants (Chea Citation2021). Hence, the respondents for the questionnaire were limited to those three groups and either had to be currently living in goshiwons or at least to have lived in goshiwons in the past ten years. For each group, a specific area in Seoul was visited where the population of the intended respondents could be easily found due to the zoning of the area (see ). Seongbuk and Mapo District, which are well known as educational and commercial areas, were chosen as the main sites to gather student and office worker respondents. The industrial area of Dongjak District was chosen as the main site to look for labor worker respondents. in Introduction section shows a representation of Goshiwon for each district. Additionally, the occupants of the three Goshiwons mentioned on the Introduction section contributed to more than 40% of the total responses used in this study.

The three Goshiwons mentioned are considered as representative because they were located within the designated sites and the occupants of each Goshiwon fit the intended respondents for this study. Out of 129 responses obtained from the online questionnaire, four responses were classified as “straightliners” because the same answers were selected for all of the questions, hence they were deemed invalid data. The age of the respondents varied from 20 to 45 years old with the highest number of respondents aged 26–30. Respondents at older ages of 35–45 belonged to the labor workers. The number of student respondents was the highest at 58.4% of the total respondents, followed by office workers and labor workers, with 27.6% and 13%, respectively. The validity of the answers given by the respondents were checked by running the outer loading and average variance extracted (AVE) test on the relevant software, explained on the next sub-section.

For the interview process, out of the initial plan of 14 respondents, only 12 people from occupational backgrounds similar to the questionnaire were successfully gathered to obtain detailed information on the subjects. The initial plan for the assortment of respondents was six students and four each of office and labor workers. However, due to the difficulties of finding suitable laborer respondents, only three people were considered. Out of the three, one respondent was a manager of a goshiwon establishment where labor workers were the main occupants. The manager was confirmed to be able to answer the questions with the same accuracy as the labor workers, and hence was considered a valid respondent. Two office worker respondents live in Goshiwon A shown in the Introduction section, three student respondents live in Goshiwon B, and all labor worker respondents live in Goshiwon C. The age range of the student respondents was 23–27 years old, 27–31 years old for the office worker respondents, and 38–53 years old for the labor worker. Eight of the interviewees were living in a Goshiwon when the interview was conducted while the others lived in one up till 6 months before the survey. Before the interviews were conducted, we made sure that all interviewees are capable to give information needed for this study. Due to the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic at the time of data collection, most of the interviews were not conducted face-to-face. A set of structured questions was prepared beforehand to ensure the comprehensiveness of the interview results and that each respondent received the same questions. The questions for the interview followed the same variables as the questionnaire and are explained in the next section. Furthermore, the questions were checked and approved by senior researchers that are experts in housing studies to confirm its validity.

3.2. The path model

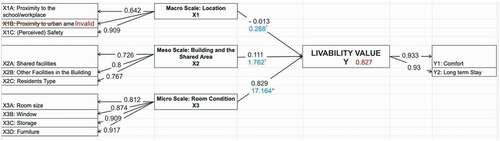

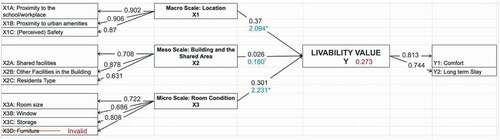

A path model was designed as the guideline for the data collection, based on the literature review conducted earlier. As seen in , this study investigates the correlation between the living environment of goshiwons as the independent variables and the tenants’ perceived livability as the dependent variables. Although livability is such a complex matter to measure, this study focuses on the physical aspects of it and after referring to micro-housing concept, we categorized the important physical components of livability into three variables with total of ten indicators. There are three independent variables in the model: (i) the location of the goshiwons, (ii) the building condition and the quality of the shared areas, and (iii) the room facilities and overall condition. Location was measured by the proximity of the goshiwons to important places for the residents and by how safe the residents felt about living in that area. The building and shared areas were measured by how satisfied the residents were with the areas other than their rooms, including other establishments in the building. Lastly, room condition was measured by all attributes that are related to the physical quality of the rooms. One dependent variable was proposed, the livability value, and it was measured by the comfort level of the residents and their willingness to stay long term.

Each of the independent variables had three to four indicators, and the dependent variable consisted of two indicators, both based on the earlier review of micro-housing physical attributes. The model was used for four observations in total: current livability (quantitative), improvement suggestions (quantitative), current livability (qualitative), and improvement suggestions (qualitative). The first two usages of the model were to measure the current situation, and the second two usages were to measure the possible future improvements. Hence, both the questionnaire and interview had two parts, one of which focused on the current living situation of goshiwons, the other of which focused on improvement suggestions based on the design principle in micro-housing. An example of the questionnaire points for each part is as follows:

“X3A: Room sizeCurrent living environment of Goshiwons: The room size allows me to do basic daily activities comfortably. Improvement suggestion: The comfort of Gosiwons would be improved if there is a minimum standard of room size that allows me to do basic daily activities comfortably (around 14 m2).”

Questions for the interview were also derived from the path model and related to the variables. A total of two open-ended questions were asked to the respondents. The first question was about the living environment of goshiwons, and the other question was about suggestions for future improvements. With the first question, the author tried to understand the reason why the respondents chose to stay in a goshiwon and to learn the experience of living in a goshiwon, especially the details related to the three scales of goshiwons’ physical environment. The second question aimed to gather detailed suggestions from the respondents to improve goshiwons’ livability. Furthermore, respondents’ tendency and willingness to stay in an improved goshiwon was also investigated through the interview process.

3.3. Data analysis

The questionnaires consisted of 24 indicators, and the respondents answered the questionnaire with agreement or disagreement in a five-point Likert scale (from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”). The first 12 points were related to the current living environment while the next 12 points were related to suggestions for improving goshiwons. Each set of the 12 points is distributed to three independent variables and one dependent variable. Independent variables include Goshiwon’s physical attributes that are divided into various scales as has been explained in previous section: (i) location as the macro scale, (ii) building and shared facilities condition as the messo scale, and (iii) room condition as micro scale. Degree of livability is the only dependent variable in this study. All 24 points were designed to be reflective indicators because manipulation towards the variable will also be reflected on the indicators (Dijkstra and Henseler Citation2015). The data from the questionnaire was then analyzed with SmartPLS software, which is well known to be reliable in analyzing the path model similar to the one used for this study. SEM was chosen for this study rather than the conventional multiple regression because SEM can present more significant statistical relationships between the independent and dependent variables (Nusair and Hua Citation2010). Additionally, the model used in this study involves latent and observed variables that are more efficient to be analyzed by the SEM method. Following the path model in , the obtained data were inputted into the smartPLS 3.0 for path modelling in two main steps.

The first step included checking the validity and reliability of the indicators in measuring the variables. After constructing model in the software, each indicator’s value of the outer loading and average variance extracted (AVE) were calculated to measure the validity. Next, the reliability test was conducted by calculating Cronbach’s alpha. The threshold of the outer loading, AVE, and Cronbach’s alpha to be considered valid and reliable are 0.5, 0.5, and 0.6, respectively (Hair, Ringle, and Sarstedt Citation2011). This process was done by running the PLS algorithm on the software. After the relationship of the independent variables and their indicators proved to be valid and reliable, the correlation evaluation between the independent variables and the dependent variable was conducted. In this step, the path coefficients of the model were measured to find out the positive or negative correlation between the independent and dependent variables. Next, through the bootstrapping process, the t statistic was also measured to ascertain the significance of each correlation. The universal standard of 1.96 was used to determine whether an independent variable significantly affected the dependent variable. Last, the predictive relevance through running the blindfolding method was measured to predict the validity of the entire model. From the predictive relevance, the appropriateness of the independent variables in predicting the dependent variable can be observed.

For the interview data analysis, thematic analysis was used. In thematic analysis, the answers are grouped to find patterns or themes that are useful to answer the research question (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Three main phases of thematic analysis were conducted to find a pattern in the interview data before finally matching it up with the questionnaire results. The first phase was organizing the interview data. In this step, all oral interviews were written and relevant information was highlighted. The second phase was searching and reviewing themes. Information related to the four variables shown in the path model (location, building and shared areas, room condition, and livability value) was sought and reviewed. The last phase included the definition of each theme and utilizing information to help construct the conclusion.

4. Results

Following the aim of this study, the results were divided into two main parts: the physical aspects that affect the current livability of goshiwons and suggestions for future improvements. For both parts, the questionnaire results are presented first to convey general information about the research subjects, followed by the interview results to provide more detail.

4.1. Current living environment

While checking the validity and reliability, variable X1B: “Proximity to amenities” was invalid and unreliable in predicting its latent variables after the first data was inputted. After these indicators were eliminated, the values were once again inputted into the software, and confirmatory factor analysis was conducted again. The new result shows all indicators were valid and reliable to measure the correlation between the variables. shows the complete validity and reliability measurement of the indicators.

Table 3. Validity and reliability measures for the current living environment evaluation.

After the evaluation of the indicators was complete, the next step was to evaluate the correlation between the independent and dependent variables. Before evaluating the correlations, the Stone-Geisser’s Q2 value, also known as the predictive relevance evaluation, was calculated to check the model suitability (Geisser, Citation1974). The Q2 value can be obtained by running the blindfolding process in the SmartPLS software, and the suggested value for the model to be considered well structured is greater than 0. The proposed model has a Q2 value of 0.689, which indicates that the model is well constructed. The evaluation for correlation between independent and dependent variables was conducted through the path coefficient test as well as the t-statistic test to determine the significance. shows the result of the path coefficients and t statistics for each variable, written in black and blue, respectively. The result shows that location has a negative correlation with the livability value, while the other two variables have a positive correlation. However, only the room condition shows significant correlation with the livability value. Also shown in is that the R-squared value of the model is 0.827, which means that 82.7% of the current livability value of goshiwons is indeed determined by the location, building, shared facilities, and the room condition.

Figure 5. PLS algorithm and bootstrapping analysis result for the current livability of goshiwons. *p < 0.05 †0.05 < p < 1.

For the interview results, shows the core statements of each group of goshiwon tenants. Although all respondents agreed that location was the biggest advantage of choosing goshiwons as their residential place, almost all respondents also agreed that the only beneficial aspect about the location was the close proximity to their school or working places. For students and labor workers, the free meals were really appreciated, while the office workers seemed to more greatly appreciate having no deposit or extra utility bills. During interviews, students and office workers complained about goshiwons being in the same building as other facilities. The labor workers, who were notably older than the other tenants, expressed that living in goshiwons caused loneliness that could lead to depression. Lastly, all respondents agreed that there should be a minimum standard to ensure the appropriateness of goshiwons as a living environment.

Table 4. Tenants’ perceptions of the current living environment of the goshiwons.

4.2. Suggestions for future development

For analyzing the future development of goshiwons, similar to the current livability analysis, validity and reliability measures were first presented. After the evaluation was done, indicator X3D was proven to be invalid and hence had to be eliminated from the analysis. shows the complete validity and reliability measurements after the invalid indicator was removed.

Table 5. Validity and reliability measures for evaluation of future improvements.

Similar to the evaluation of the current living environment, the predictive relevance value was first measured. For analyzing the possible future improvements for goshiwons, the model only has predictive relevance of 0.122. The value is still considered relevant, but not as relevant as when the model was used to analyze the current livability of goshiwons. The path coefficient and t statistic tests were performed; the results are projected in , and it shows that all independent variables positively correlate with an increase in livability value. Improvements in the location and room condition affect the perceived livability of goshiwons significantly, while the improvements in building and shared areas are proven not to be significant. This indicates that if there were improvements in the location and room quality, tenants would see goshiwons as a more livable housing option. However, the R-squared value of the first model is only 0.273, meaning that the observed independent variables have a little contribution in predicting the livability value and that there are other factors that should be considered in improving the livability value of goshiwons.

Figure 6. PLS algorithm and bootstrapping analysis result for the future improvements. *p < 0.05 †0.05 < p < 1.

Based on the interview data presented in , even though most of the respondents agreed that goshiwons have strategic locations near schools or workplaces, inconveniences often arise from some types of neighboring facilities and businesses. Due to close proximity to universities and offices, the areas where goshiwons are located often attract late-night entertainment establishments as well. Students expressed that the safety could be compromised if a goshiwon were located near such establishments as nightclubs and bars. Similarly, the office workers also expressed their concern about the entertainment facilities and that those facilities can get too noisy and disturb the tenants. Regarding room improvements, students emphasized the need for a comfortable studying environment, such as the provision of a shared reading room or the improvement of the desk and chair in the room. For the office workers, good soundproofing seems to be the demand to enhance their sleep quality at night. Meanwhile, the labor workers were more concerned about fire safety due to the large number of rooms on one floor. One respondent recalled an incident that happened in 2018 in Seoul where a goshiwon establishment caught fire and killed seven of its occupants. In some goshiwons, the high number of rooms had created multiple double-loaded corridors that would make it more confusing to find the emergency exit in case of fire. Except students, there was a tendency for all respondents to maintain low interest in staying in goshiwons even with the improvements. Office workers would only live in goshiwons as a method of saving money to move to a better apartment. The labor workers stated that, even with the improvements, goshiwons already had a bad reputation as a living environment, and that if they had enough money they would opt to live in public housing.

Table 6. Tenants’ suggestions for the future development of goshiwons.

5. Discussion

Although a goshiwon’s living environment is lacking in many aspects and it is far from the ideal residential space, many believe that it plays a crucial role in supplying low-cost housing options in Korea (Lee and Yoon Citation2010; Ryu and Kim Citation2021; Ko, Lee, and An Citation2016). Preliminary study on related laws and regulations led to an assumption that one of the main reasons for the deterioration of goshiwons is the absence of a law specifically tailored to them and that there are gaps between the current regulations. Due to similarities in many aspects, this paper used the core concepts of micro-housing to find crucial areas for improvement to transform goshiwons into a more livable space. Based on cases around the world, micro-housing concepts are implemented on three different scales: room, building, and neighborhood. Hence, this study used those three scales to investigate the current living environment and the pivotal aspects that need to be changed to improve the livability of goshiwon. Many previous studies have been conducted about users’ satisfaction in goshiwons and directions for goshiwons’ improvement separately (Ryu and Kim Citation2021; Lee and Yoon Citation2010). However, this study argues that it is important to study both aspects simultaneously to get results that are applicable to policy developments. Focusing only on the current situation would not be beneficial without knowing which elements to improve, and without investigating the current situation, suggestions for future improvement would not be valid.

Three aspects from different scales were observed in this study. The first variable concerns the location, which represents the macro scale aspect of a micro-house. In contrast to some of the previous studies (Kim Citation2014; Ko, Lee, and An Citation2016; Cho et al. Citation2017; Lee and Kim Citation2017), location was found to negatively affect the current livability of a goshiwon, and improving location positively affects the future livability of a goshiwon. However, location was not proven to significantly affect the users’ perception of the current livability, but improvements of it, significantly affects the future livability. This finding is valuable because, by default, location is believed to be the biggest value of goshiwons. From the interview results, it was understood that, although respondents appreciated the short distance from their goshiwon to their school or workplace, they found other facilities around it quite disturbing. This finding follows a previous study that stated goshiwons are often agglomerated around entertainment facilities such as arcades, pubs, and karaoke places (Koo Citation2019). This result indicates that although location is the main attraction of micro-housing, it needs to be understood more deeply and comprehensively. Close proximity to the school or workplace should not neglect the comfort and safety aspects of location. Another study in New York City suggests that proximity to open spaces is also important in aiming for low perceived density (Fisher-Gewirtzman Citation2017). Low perceived density helps to ease the crowded and stuffy feelings that often arise in high-density city center. The second variable concerns the shared facilities and other non-goshiwon facilities within the same building. Although it was not proven to significantly affect the current or future livability of a goshiwon, interview respondents mentioned that there were specific facilities they wished were not in the same buildings as the goshiwon, such as restaurants and pubs. A study by Byun and Choi (Citation2016) states that the living room is the center in traditional Korean houses and although younger respondents do not share the same value, older residents wished goshiwon could provide a centralized communal space.

The last variable focuses on the room condition of the goshiwon. As the most significant variable that positively affects the user’s perception of livability, room condition holds the critical value to transform a goshiwon into a livable micro-house. This is further supported by the interview result showing that respondents’ negative perception of a goshiwon’s living situation is mostly due to the poor room environment. Unlike the other variables in which the respondents had limited suggestions for improvement, more answers were given in terms of room improvement, showing how impactful the room condition was to the respondents. This result is in line with a previous study by Jin and Choi Citation2018 that says that the possibility of choosing a room that matches one’s needs elevates the resident’s satisfaction. Another study in Almaty proved that design in the smallest details could help improve the room quality in a micro house (Karatseyeva and Akhmedova Citation2022). The interview result also shows that each group of goshiwon residents has different needs that necessitate diversifying goshiwon facilities depending on the residents, as also shown in research by Yoo, Yang, and Kim (Citation2019). The last interview points show that, while graduate students had a higher tendency to live in goshiwons if the improvements were made, office and labor workers implied that if money were not an issue they would never choose goshiwons, even with improvements. This indicates that, although there are indeed several avenues for improving goshiwons’ livability, there is low trust from most of the residents for goshiwons to be a model of livable micro-house. Regarding the low interest in staying in Goshiwon even after the improvements, previous studies stated that micro-housing is not only about providing low-cost housing but also introducing and accommodating a new city lifestyle that are acceptable especially by the current generation (Soub and Memikoglu Citation2020; Karatseyeva and Akhmedova Citation2022).

6. Conclusion

Due to the deterioration of the living environment of goshiwons, despite their popularity as an option for affordable housing for single occupancy, specific laws and regulations are urgently needed to maintain the sustainability of goshiwons. In order to contribute to the study of required regulations, this study aims to investigate the current living situation of goshiwons and to recommend a set of possible directions for future development that can enhance their livability. Several attempts were made to distinguish this study from previous research. The first was the adaptation of the micro-housing concept to construct the path model, resulting in multi-scale variables to be studied. The second attempt was the usage of a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods to gain a more comprehensive result. This study observed goshiwon livability through three physical scales: room, building, and neighborhood or location. The result of this study indicates that the relatively poor condition of goshiwons is the significant cause of their low livability. The main reasons why goshiwons’ rooms are considered poor include (i) poor soundproofing quality, (ii) insufficient natural light and poor air circulation due to the small size or absence of windows, and (iii) the large number of rooms per floor that is perceived as a fire hazard. Although it is palpable that improving the room condition of goshiwons would lead to higher livability, this study proceeded with another set of observations that focused on how to improve the livability. Based on the results of the observations, we presented some important points that can be useful in determining directions for physical improvement of goshiwons as an alternative of livable micro-house in South Korea and other megacities with similar urban fabric and society issues, such as Hongkong and Tokyo .

First, for goshiwons to be considered a livable form of micro-housing, the statistical analysis suggests that room condition should be significantly improved by having a sufficient minimum room size and a window to allow natural light and air circulation. Those are the two basic requirements for a room to function properly. Next, the installation of proper soundproofing and a clear evacuation system are highly recommended to boost the comfort of the occupants. Second, although location is often believed to be the biggest benefit of living in a goshiwon, there should be regulations on how to ensure it is safe from crime and other disturbances. Interview results show that although all respondents most valued the strategic location of their goshiwon, tenants also wished for a safer and quieter area. Although through this study it was indicated that the livability of a goshiwon can be enhanced by improving several of its physical attributes, the sustainability of goshiwons needs to also consider people’s actual willingness and intention to occupy them. Reflecting in many micro-housing projects around the world, one of the keys to make it work is to not only focusing in providing cheap house but also to persuade people that “going small” doesn’t equal to sacrificing comforts. Results of this study indicate that careful planning in the neighborhood scale and room design that pays attention to details might be the key to change the image of Goshiwon into a more livable micro-house. Future research needs to be conducted on other non-physical features that can enhance goshiwons’ livability, such as how to improve the general image of goshiwons in the public’s eyes. Since this study is limited to only the physical aspects, future research should also include the social, cultural, and management dimensions to gain a deeper understanding of the uniqueness of the goshiwon and how to transform it into a better, more livable micro-house.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Odilia Renaningtyas Manifesty

Odilia Renaningtyas Manifesty is a PhD candidate at the Korea University Urban Lab (KUUL), Department of Architecture and a teaching staff at the Gadjah Mada University. Her research focuses on the association between urban space and how it affects human comfort and behavior.

Byunghak Min

Byunghak Min is a research professor at the Department of Smart City, Korea University. His research focuses on the sustainable operation of smart cities and strategies in urban design for energy consumption optimization.

Seiyong Kim

Seiyong Kim is a professor at the Department of Architecture, Korea University and the head of the Gyeonggi Housing & Urban Development Corporation. His research focuses on housing studies in Korea and strategies in creating livable urban space for future cities.

References

- Bae, J.-H. 2019, March 12. ““Lonely Island Gosiwon” 12,000 Places Nationwide, “Lonely Life” … Half of Them Focus on Seoul.” The Asia Business Daily, Accessed 9 February 2022 https://www.asiae.co.kr/article/2019031208194899592

- Batista, L., and H. Farias. 2021. January 1. “Can Micro-Housing Policies Enable Higher Liveability Standard in Urban Areas? Case Study of Cascais Historical Centre, Lisbon, Portugal.” Architecture and Urban Planning 17 (1): 1–5. doi:10.2478/aup-2021-0001.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Byun, N., and J. Choi. 2016. “A Typology of Korean Housing Units: In Search of Spatial Configuration.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 15 (1): 41–48. doi:10.3130/jaabe.15.41.

- Chea, S. 2021. “Number of single-person Households Surprises Even Statistics Korea.” Korea Jungang Daily. 3 August 2021. 06 November 2021.

- Choi, H. H., and M. J. Kim. 2015. December 31. “Single-Person Household Needs with a Focus on Interior Planning.” Korean Institute of Interior Design Journal 24: 163–170. doi:10.14774/jkiid.2015.24.6.163.

- Cho, S., Y. Lee, J. Park, and H. Lee. 2017. “Customized Planning of Community Shared House for Gosiwon Residents.” Journal of the Korean Housing Association 29 (2): 119.

- Dijkstra, T. K., and J. Henseler. 2015. “Consistent Partial Least Squares Path Modeling.” MIS Quarterly 39 (2): 297–316. doi:10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.2.02.

- Fisher-Gewirtzman, D. 2017. “The Impact of Alternative Interior Configurations on the Perceived Density of Micro Apartments.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 336–358.

- Fox, C., and M. Humphries. 2021. December 9. “29 Photos of Tiny Living Spaces Show How Overcrowded and Unaffordable the World Has Become.” Insider. Accessed 3 November 2022 https://www.insider.com/the-smallest-living-spaces-around-the-world-2019-10#in-tokyo-some-20-somethings-have-chosen-to-live-in-affordable-tiny-apartments-so-they-can-spend-their-money-in-other-ways-7

- Geisser, S. 1974. “A Predictive Approach to the Random Effect Model.” Biometrika 61 (1): 101–107. doi:10.1093/biomet/61.1.101.

- Hair, J. F., C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2011. “PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet.” Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 19 (2): 139–152. doi:10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202.

- Harris, E., and M. Nowicki. 2020. ““GET SMALLER”? Emerging Geographies of micro-living.” Area 52 (3): 591–599. doi:10.1111/area.12625.

- Iglesias, T. 2014. “The Promises and Pitfalls of micro-housing.” Zoning and Planning Law Report 37 (10): 1–12.

- Ivankova, N. V., J. W. Creswell, and S. L. Stick. 2006. “Using mixed-methods Sequential Explanatory Design: From Theory to Practice.” Field Methods 18 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1177/1525822X05282260.

- Jackson, A., B. Callea, N. Stampar, A. Sanders, A. De Los Rios, and J. Pierce. 2020. “Exploring Tiny Homes as an Affordable Housing Strategy to Ameliorate Homelessness: A Case Study of the Dwellings in Tallahassee, FL.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (2): 661. doi:10.3390/ijerph17020661.

- Jin, M.-Y., and S.-H. Choi. 2018. “Supply of Goshiwon, Status of Operations Management, and Future Policy Direction.” Land Housing Research 26 (3).

- Jin, S. J., K. H. Kim, and J. Kim. 2018. “An Empirical Study on the Housing Satisfaction and Continued Residential Intention of the Semi House Residents - Focused on the one-room Type Gosiwon in Seoul.” Journal of the Korea Real Estate Management Review, 18: 205–233.

- Karatseyeva, T., and A. Akhmedova. 2022. “Modern Tendency of Development of Architectural Typology on the Example of micro-apartment for Almaty City.” Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management. (ahead-of-print). doi:10.1108/ECAM-01-2022-0080.

- Kim, J. W. 2014. “A Study on the Satisfaction and the Needs of Students and Office Workers in Single Households: A Case of ChoongJungRo District in Sudeamoongu, Seoul.” Journal of Korea Design Knowledge 30 (8): 79–90.

- Kim, Da-sol. 2017. “[Feature] Gosiwon, Modern Time Refuge for House Poor.” The Korea Herald, September 24. Accessed 15 August 2022. https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20170924000045#:~:text=Gosiwon%20are%20a%20form%20of,almost%20always%20require%20handsome%20deposits

- Kim, K. H., and M. Cho. 2010. “Structural Changes, Housing Price Dynamics and Housing Affordability in Korea.” Housing Studies 25 (6): 839–856. doi:10.1080/02673037.2010.511163.

- Kim, J., and S. Yoo. 2021. “Perceived Health Problems of Young single-person Households in Housing Poverty Living in Seoul, South Korea: A Qualitative Study.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (3): 1067. doi:10.3390/ijerph18031067.

- Ko, J. Y., Y. S. Lee, and S. M. An. 2016. “Preferred Features of Communal Shared Housing of the Urban Young Adults and Adults Housing Poor-Focused on Single Household Living in the Deprived Area of Seoul.” KIEAE Journal 16 (2): 53–66. doi:10.12813/kieae.2016.16.2.053.

- Koo, H. 2019. “The Spatio-Temporal Distribution and Housing Conditions of a Gosiwon in Seoul.” Journal of the Korean Cartographic Association 19 (2): 105–118. doi:10.16879/jkca.2019.19.2.105.

- Lee, S. 2020. “Goshiwon of Noryangjin: A Preliminary Study of Goshiwon and the Effects of Its Confined Spatial Environment.” Doctoral dissertation, University of Cincinnati.

- Lee, E. 2021. “Housing Policy Suggestion for one-and two-member Households through Comparative Analysis between South Korea and Japan.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 20 (1): 114–122. doi:10.1080/13467581.2020.1782207.

- Lee, J. H., and Y. H. Kim. 2017. “The Planning Characteristics Analyzed by Spatial Composition of Domestic Share House.” KIEAE Journal 17 (4): 5–12. doi:10.12813/kieae.2017.17.4.005.

- Lee, S.-H., and E.-J. Lee . 2014. “Improving Residential Environment of Quasi-Housing through the Residents Satisfaction Survey on Indoor Public Spaces - Focused on the Go-shi-wons at Seoul.” Journal of the Architectural Institute of Korea Planning & Design 30 (4): 15–22. doi:10.5659/JAIK_PD.2014.30.10.15.

- Lee, S. H., and E. Lee. 2016. Understanding Residential Needs of Single or 2-Resident Households with a Focus on Communal Amenities of Multi-Family Housing Complexes. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 15(2), 263–270. doi:10.3130/jaabe.15.263.

- Lee, J.-S., and J.-S. Yang. 2013. “A Study of the Characteristics and Residential Patterns of Single-person Households and Their Policy Implications in Seoul.” Journal of Korea Planning Association 48 (3): 181–193.

- Lee, J.-E., and Y.-H. Yoon. 2010. “A Study on the Analysis of the Design Standards of Quasi-housing.” Journal of the Architectural Institute of Korea 30 (1): 35–36.

- Newsis. 2021, March 19. “Lee Jae Myung “The Goshiwon Is Also Stipulated by the Minimum Standard Law”.” Newsis, Accessed 2 August 2022 https://mobile.newsis.com/view.html?ar_id=NISX20210319_0001376982

- Nusair, K., and N. Hua. 2010. “Comparative Assessment of Structural Equation Modeling and Multiple Regression Research Methodologies: E-commerce Context.” Tourism Management 31 (3): 314–324. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2009.03.010.

- Park, C.-S., E.-D. Lee, Y.-S. Lee, and G. Ji-young. 2014. “Housing Conditions and Satisfaction of the “Gosiwon” Residents in Seoul.” Journal of the Korean Housing Association 103.

- Ryu, H.-J., and S.-K. Kim. 2021. “Content Analysis on the Amenities and Housing Service for Single-person Households.” Journal of the Korean Housing Association 32 (4): 1–11.

- Shearer, H., and P. Burton. 2019. “Towards a Typology of Tiny Houses.” Housing, Theory and Society 36 (3): 298–318. doi:10.1080/14036096.2018.1487879.

- Soub, N. M. H., and I. Memikoglu. 2020. “Exploring the Preferences for Micro-Apartments.” Online Journal of Art and Design 8 (2).

- Streimikiene, D. 2015. “Quality of Life and Housing.” International Journal of Information and Education Technology 5 (2): 140. doi:10.7763/IJIET.2015.V5.491.

- Yeung-kurn, P., K. Pan-jun, and H. Tae-soo. 2007. “Effects of Housing Environment on Value, Satisfaction and Repurchase Intention of Housing.” Journal of Distribution Science 5 (1): 89–105. doi:10.15722/jds.5.1.200706.89.

- Yoo, H. Y., J. W. Yang, and J. S. Kim. 2019. “A Study on the Direction of Improvement by Analyzing the Characteristics of Goshiwons for Urban Regeneration in Deteriorated Residential Blocks.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 18 (5): 392–403. doi:10.1080/13467581.2019.1661254.