ABSTRACT

Taking Confucian temples in Southwest China as an example, this paper discusses the combination of traditional temple architecture in East Asia and mountain topography. Based on the fieldwork survey of 14 existing mountain Confucian temples in Southwest China, the paper provides the first systematic examination of the topographical influences on courtyard spatial layouts and landscape environment of Confucian Temple. The author discusses the topographical influences on the orientation and axis sequence organization of the Confucian temple. Then, the diversity of the guiding space layouts is explored by combining the theory of Figure-ground and Space Syntax. On this basis, the author takes the most representative “vertical interface” of the mountain Confucian temple as a point of departure for re-examining the plant configuration and water environment that match the mountain topography. The finding of the paper shows how to implement a set of mature building complex under mountain topography and create an amazing landscape environment in Southwest China during the 15th- 19th centuries. The work enriches the discourse in the study of the traditional temple in East Asia and provides the theoretical basis for the conservation of Confucian temple architectural heritage.

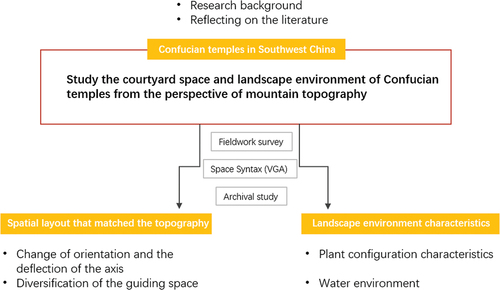

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research background

Confucian culture is the orthodox culture of China for over 2000 years, its influence is so broad that the Confucian temples used to be found throughout East Asian countries, and the official worship of the great sage was carried out in the spring and autumn equinoxes. “Confucian culture flows eastward into the sea, cultural prosperity revitalized the Shenzhou.” in < Yongzhao Temple nostalgia > by Shioya, a modern Japanese scholar, is the evidence of the rise of Confucian culture in Japan. In East Asia from the 7th century onwards, the Confucian temple was a renowned, intellectual and cultural center. In the process of spreading the Confucian temple to a wider space, the Confucian temple that was originally born in a flat area faces the complex topography in mountainous areas. This not only happened in China, Tomshima shrine and Idle Valley School Confucian temple in Japan; Hue Confucius Temple in Vietnam; Rural school Confucian temples in North Korea, including Qingzhou, Yangchuan, Gaoyang, Huairen, and so on, are all important representatives of mountain Confucian temples. The Confucian temple building complex formed by the orderly combination of single building units needs to consider the synchronization of buildings and topography more than the western mountain architecture. How did the ancient builders in various regions meet the challenge of topography and what spatial and environmental characteristics of the Confucian temple they have created are important topics in the study of Asian Architectural Heritage.

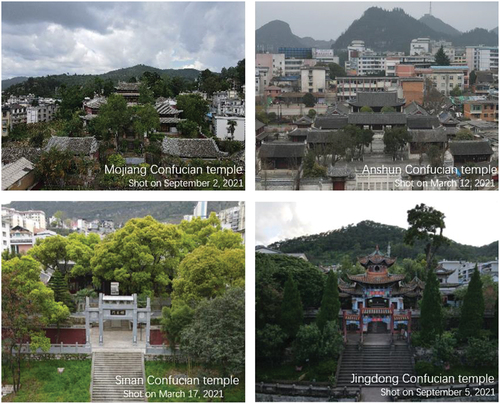

Southwest China consists of Yunnan, Guizhou, Sichuan, and Guangxi provinces. This area ushered in the peak of the development of mountain Confucian temples during the 15th to 19th centuries, especially in Yunnan and Guizhou provinces. The prosperity of Mountain Confucian temples is not only by the topographic factor but also related to the movement of “ Changing Tuguan to Liuguan” implemented by the central government to strengthen their control of Southwest China. On the one hand, Confucius (Kongzi),Footnote1 one of the great cultural heroes, was invited into the southwest frontier dedicated to the orthodox culture. On the other hand, the limited scale of cities built in this movement promoted the construction of Confucian temples in the suburbs along the mountain. A point worth emphasizing is that the development of mountain Confucian temples in Southwest China during the 15th to 19th centuries was not blocked by the invasion of Manchu rulers. During the establishment of the worship of Confucius, not only did the Han nationality literati circles spare no effort, Manchu rulers in the Qing Dynasty still respected it. “By not placing emphasis on rites or righteousness, the emperor runs the great risk of contributing to a weak, disordered, and chaotic larger community.” (Davidson Citation2016) This understanding of the Manchu emperor ensured the continuous development of the Confucian temple. During this period, 102 mountain Confucian temples were built in Yunnan and Guizhou provinces. These mountain Confucian temples were mainly distributed along the Miaojiang corridor, in the east of Yunnan Province, and in remote multi-ethnic settlements. Up to now, there are still more than 40 mountain Confucian temples with remains, of which more than 20 are remaining complete ().

Table 1. Distribution of mountain Confucian temples in Southwest China.

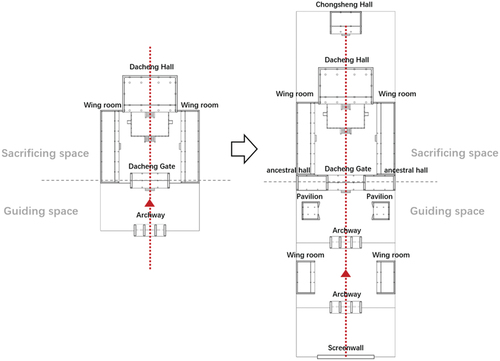

In addition, the 15th-19th century was also the development period for the building standard of the Confucian temple. The ancestral temples in the urban space were incorporated into the Confucian temple courtyard; the Lingxing archway and the Screen wall were enclosed to be the front of the courtyard space, which greatly promoted the expansion of the Confucian temple guiding space () (Qu Citation2000) (Kong Citation2018). The Confucian temple courtyard space linearly arranged by multiple courtyards was finally formed during this period, which was regarded as a tough standard related to the rites system (Pan Citation1987). Although this standard system has not been strictly implemented in every southwest Confucian temple, the expansion trend of the guiding space is significant. The constantly improving building standards of Confucian temples resonate with the complex and changeable mountain topography, it caused a diversified trend of the guiding space of Confucian temples in the process of expansion. The mountain Confucian temple in Southwest China will open the breakthrough to exploring the relationship between Confucian temple space and the topography.

1.2. Reflecting on the literature

Confucian temples, as a type of architectural heritage all over East Asia, the comparison of Confucian temples in different countries at the architectural level has been the subject of much debate since the end of the 20th century. Scholars from other countries outside China, especially Korean scholars, have actively participated in the research on this topic. Jang (Citation2005) focuses on Korean traditional architecture including Confucian Temple, which has an asymmetric spatial form due to its adaptation to natural conditions. In the construction of the asymmetry with a bent axis or arbitrary arrangement, the building makes use of the hierarchic method rather than the spatial method to represent a hierarchy. Through the analysis of the natural environment, this Jang emphasizes the uniqueness of Korean Confucian temples. Na and Park (Citation2022) provide an overview of the existing significant heritage factors of the Temple of Literature in Vinh Long by comparative examination in relation to other surviving temples and analyzing its unique spatial characteristics. It points out that the layout of the temples was influenced by the Chinese Confucius’s principles and the notion of Feng Shui, and the buildings have many architectural elements that reveal Vietnam’s unique culture and local features. In these comparative studies, natural factors, including topography, have become an important angle for scholars to explore the spatial characteristics of Confucian temples in different countries.

The study of Confucian temples in China is more abundant, many Chinese scholars have conducted extensive investigations on Confucian temples, both local and international. Based on the investigation and statistics, they enumerate a series of mountain Confucian temples in China and explain the construction models that comply with the stratification of platforms (Peng Citation2011) (Kong Citation2011). In addition, the special research on Confucian temples in Yunnan Province makes a comprehensive investigation of the existing Confucian temples, covering more than 10 cases of mountain Confucian temples. The single building characteristics and courtyard space layout of each case are shown in a schematic way (Yang Citation2015). Zhou Citation2020) focuses on the Spatial Forms of The Confucian temple in the “Miaojiang Corridor in Guizhou province, attempts to analyze the indoor and outdoor connectivity, spatial permeability, and accessibility of Confucian temple buildings with the quantitative analysis of spatial syntax.

The brief literature review demonstrates that even though the study of mountain Confucian temples has attracted some attention, no comprehensive study regarding the characteristics of mountain Confucian temple spatial layouts has been examined, the quantitative and systematic research on the relationship between mountain topographic parameters and the spatial layouts of Confucian temples still needs to be explored. The research on the environmental characteristics of Confucian temples brought by topography is even less. For decades, architectural historical scholarship on China’s Confucian temples has been dominated by the study of Confucian temple courtyard spatial morphology in flat areas and Characteristics of single buildings (Wang Citation2013). This narrow scope of inquiry may be attributed to the fact that the building standard of the Confucian temple only stipulates the composition, and form of important buildings, while the expression of the spatial layout of the Confucian temple under the mountain topography is not stipulated in the process of formulating the standard. The topography factor, which was not fully considered in the building standard, led to the neglect of a research angle that is most suitable for exploring the diversity of space and environment. A point worth emphasizing is that the research on the relationship between architecture and topography has achieved the considerable number of research results from a worldwide perspective. A study on the relationship between Persian architecture and topography by Maryam Naghibi was published in 2021. The author selects 44 cases following berlanda’s categories, Analyze the code and data by MAXQDA and interprets the elements and strategies on how a building meets the ground in Persian case studies. (Nag, et al. Citation2021). Hoshyar and Ahmed (Citation2018) analyze several parameters influencing settlements in the Iraqi Kurdistan region, formed by topographical factors, and explain the influences of topographical factors that are defined as basic variables in the physical configuration of residential buildings. The research on the relationship between architecture and topography also involves traditional Buddhist temples, hospitals and other architectural types. (JANG Citation2015) (O’Keeffe, Virtuani, Citation2020) The above research findings bring inspiration to the research of Chinese traditional Confucian temples. At the same time, the research on the space and environment of mountain Confucian temples will also enrich the research framework in this field of worldwide concern. It has greatly prompted this comprehensive appraisal of the evidence in mountain Confucian temple in Southwest China.

1.3. Purpose of the study

This paper is a study of the courtyard space and environment of Confucian temples from the perspective of mountain topography. A quantitative analysis of the architectural information and topographic parameters of more than ten mountain Confucian temples in Southwest China is performed and the diversity of the spatial layout of the mountain Confucian temples is presented in the form of visual graphics. On this basis, the characteristics of environmental elements such as plants and water systems that match the mountain topography have also been systematically analyzed. This work will not only reveal the traditional construction wisdom of the combination of ancient temple buildings and topography in East Asia and bring inspiration to the protection of Confucian temple architectural heritage.

2. Methodology

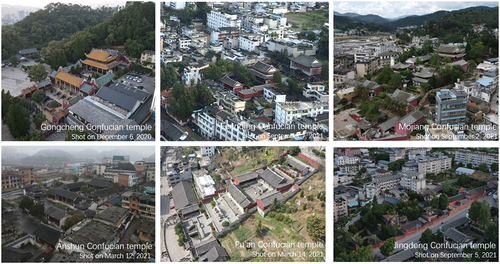

The fieldwork survey is used as the basic method to study the Mountain Confucian temple courtyard space and the environment. For the large amounts of mountain Confucian temple remains in Southwest China, extensive research by cultural relics departments and non-governmental organizations has identified them as important architectural heritage, and yet crucial areas have remained unmapped, especially the ceremonial centers and their surroundings, where dense forest obscures the traces of the construction activities that typically remain in evidence in surface topography. That was particularly the case for the surrounding topography and natural environment. All nominated temples in this paper have preserved the original topography around their main sacrificial courtyard and their sense of place as a Confucian sanctuary. Based on the field survey of these Confucian temple remains, a total of 14 Confucian temples in Southwest China were selected to research the Confucian temples’ spatial characteristics, including 12 cases in Yunnan and Guizhou Province, 1 in Guangxi, and 1 in Sichuan. The building information was gathered via observation, drawing, and written sources, such as the scale and layout of the courtyard space. Supported by the first-hand data obtained through fieldwork, a quantitative analysis of the Mountain Confucian temple courtyard spatial layouts and the environment was performed.

The gestalt notions of Figure-ground are used as a basic tool for an analysis of how buildings are arranged in the courtyard space and the relationship with topographic factors. This tool allows a clear and powerful reading of a space through a binary mapping of built space (object) and empty ground (field). As an analogy to the study of the structure of cities, the Figure-ground concept applies to the cognitive logic of Chinese traditional courtyard spaces as well. Therefore, this study schematizes each Single building in the Confucian Temple as an element of a figure and then examines how such buildings were arranged and how they were combined. Meanwhile, different genotypes of building combinations will be extracted in this process, it was carried out to discover the different building combinations employed in different topographic parameters, confirming the correlation between the change of the courtyard space layout and the topographic factors of the site.

Resorting to Space Syntax (VGA), mountain Confucian temple cases are analyzed from the perspective of worshipers’ visual perception. Space Syntax VGA is a commonly used technology to study the layout types of courtyard space. It can reflect the basic visual characteristics of space, such as the closure, penetration, and segmentation of space. Its method of space recognition was to serve as a theoretical basis for the study of the diversity of courtyard layouts. As an extension of the fieldwork survey, VGA was derived through the program DepthmapX based on the outline and drawings of the Confucian temple to visually understand its spatial structures. The influence of building combination genotypes and topographic factors on the visual effect of space can be reflected in visibility graphs.

An archival study is also conducted. The historical literature, pictures, and historical photographs have been comprehensively collected and sorted to make up for the lack of fieldwork survey and ensure the credibility of the research. Some of the Confucian temple cases involved in this paper have been transformed or partially demolished in urban construction in recent decades. The literature of the 15th-19th Century illuminates the construction process of the temple and the character of its spatial morphology and provides valuable evidence relating to the appearance of its courtyard layout and environment when it was at the peak of its prosperity. Not only the information at the material level but also traditional ideas are revealed in the historical literature. The tablet inscription used to be written after the construction or maintenance of ancient Confucian temples, containing the ancients’ understanding of the construction of the Confucian temple. The archival study makes the research perspective closer to the real situation of history and reveals the complexity of the history.

3. Exploring the spatial layout of Confucian temple that matched the mountain topography

3.1. The change of Confucian temple orientation and the deflection of the axis line

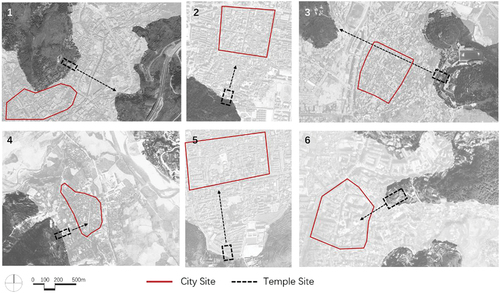

The principle of “Facing the South” in the Chinese traditional buildings is not only a natural choice but also an important principle related to the Confucian rites system. Confucian temples, as the architectural carrier of Confucian culture, generally abide by this criterion. Nevertheless, the principle was broken in the process of the development of the Confucian temple in the southwest mountainous area. The mountainous topographic conditions and unique Temple-City relationship in this area make the orientation of mountain Confucian temples changeable. On the one hand, the fit between the temple and the topography is realized in layers from low to high; on the other hand, Confucian temples pay special attention to the echo with urban space to highlight its important cultural status, which is one of the main values of Confucian temple construction in the movement of Changing Tuguan to Liuguan. Under the influence of this dual factor, the Confucian temple can only be built on the foot of the mountain facing the city, which makes it difficult to realize the ideal of “Facing the South”. Take six mountain Confucian temples as examples to illustrate this problem, including Pu’an, Tonghai, Puding, Jingdong, Dongchuan, and Mojiang, which bear the representative characteristics of the relationship between the Confucian temple, the city, and the mountain (, ). The seemed changeable orientation of Confucian temples implies the same logic that they all layout toward the city or the main road to the city with their backs against the mountains.

While the macro mountain trend and its relationship with the city lead to the changeable orientation of the Confucian temple, the subtle topographic leads to the axis line deflection of the Confucian temple. The results of the fieldwork survey show that the axis of most mountain Confucian temples in Southwest China have deflection angles ranging from 1° to 20°. This phenomenon extends much further than we currently conceive as strict Confucian etiquette did not allow arbitrary arrangement of its sacrificial buildings. To clarify the cause of axis line deflection, the author selects four cases with large axis deflection angles and draws the topographic map around the Confucian Temple combined with the elevation data (ASTER GDEM V2 30 M). The topographic maps show that the misalignment of the axis line in Confucian temple courtyard space is derived from neither Feng Shui nor the view of the mountain peak but from the natural topography of the site ().

Table 2. Axis deflection conforming to the topography.

From the four cases, the Confucian temple building group can fit the topography better through the control of two factors: the deflection angle and the number of deflections. The deflection angle of the axis line is about 3 ° in most cases. Although such a deflection angle is clearly visible on the plane, it is difficult to detect in the courtyard space. It hardly affects the Worshipers’ visual perception, while greatly reducing the artificial transformation of topography in the construction of Confucian temples. In terms of the axis deflection times, most mountain Confucian temples can make the Confucian temple buildings better fit the topography through one axis deflection. The axis of the Fuyuan temple has been deflected twice in accordance with the sharp turn of the mountain topography, one of which has an angle of 20 degrees, which is a rare Scene. Following the deflected axis line, the visual experience from the courtyard space is diverse. It not only guides the sight line upward along with the topography but also provides more observation angles at the same level.

As for the turning point of the axis line, the four cases all happen in the guiding space, which is consistent with the historical process of the continuous development of Confucian temples during the 15th-19th centuries. Due to the backward economy and the delay in the implementation of the building standard in the frontier areas, the growth process of Confucian temples in Southwest China has been greatly prolonged. The long construction cycle makes the Confucian temple lack unified planning at the initial site selection. The expanding guiding space is facing the challenge of topography, which is not well considered when the cornerstone was laid. In this case, setting a turning point and deflecting the axis in the guiding space becomes the most ideal scheme, which ensures the sustainability of the development of the Confucian temple courtyard space without the cost of relocation and reconstruction.

3.2. Diversification of the guiding space layouts under different topography

Compared with Confucian temples in flat areas, the courtyard spatial layouts of Confucian temples in mountainous areas show a diversified trend (). The paucity of textual records providing information on how the guiding space of the Confucian temple was conceived creates a problem, one compounded by our modern disciplinary separation of architecture and natural conditions. In this section, the spatial layouts of mountain Confucian temples are analyzed through the “Figure-ground” concept and different building combination genotypes are extracted to confirm the relationship between spatial layouts and topographic parameters. Based on the comprehensive investigation of Confucian temples in Southwest China, six typical representatives with a flexible layout of guiding space are selected. The “Figure-ground” model of the courtyard space, which transformed the plane into an abstract two-dimensional mode, is drawn. Then four building combination genotypes were extracted as topological types in the site Layout of Confucian Temples in China ().

Table 3. Genotypes extracted from the guiding space of the Confucian temple.

- Courtyard Enclosure

It is a common building combination of the Confucian temple in the flat area. The Dacheng gate, the archway, and the wing room located on both sides of them are enclosed into a courtyard.

- Pavilion Scattered

Several pavilions are arranged symmetrically on both sides of the axis or located on the central axis independently so that the layout of the guiding space is relatively scattered.

- Wing room Paralleled

Wing rooms are parallel to the boundary of the platform and arranged on both sides of the axis line. This building combination genotype divides the space horizontally in combination with the topography.

- Archway Independent

Separated from the “Courtyard Enclosure”, the independent archway has become the visual center of the guiding space.

One Confucian temple is usually composed of several building combination genotypes. Through the decomposition method, the complex and changeable spatial layout is presented more understandably. The four building combination genotypes extracted from these typical cases have a universal applicability in the case of the Confucian temple in Southwest China. On this basis, the complexity of the relationship between the guiding spatial layouts and their corresponding topographic parameters is analyzed.

A total of 8 cases were selected to analyze the relationship between the building combination genotypes and topographic parameters. The topographic data includes not only the macro data such as the total depth, total elevation difference, and average slope of the guiding space but also the detailed data such as the number of division platforms of the guiding space, the quantity of building bearing platform and their depth dimension (). Summarized from the statistical results of topographic parameters, the depth dimension of the building bearing platform corresponding to the Courtyard Enclosure genotype is 10.5 m-17.7 m and the corresponding average slope is 4°-8°; the depth dimension of the building bearing platform corresponding to the Pavilion Scattered genotype is 6.4 m-14.1 m and the corresponding average slope is 6°-17°; the depth dimension of the building bearing platform corresponding to the Wing room Paralleled genotype is 6.2 m-9.8 m and the corresponding average slope is 7°-17°; the archway Independent genotype has the minimum depth dimension of the building bearing surface with 3 m, which allows it to be built in a steep slope of 23°. The depth dimension of the building bearing platform is strictly linked to the building combination genotypes, and the topographic slope to some extent affected the stratification of the building bearing platform. This is a complex relationship, which depends not only on topographic characteristics but also on the way of manual intervention. It can be summarized as a general scope. When the slope is within 8°, the implementation of the Courtyard Enclosure genotype is hardly affected by the topography. With the increase in slope, the Courtyard enclosure genotype needs to combine with other genotypes based on the respective characteristics of the topography of each Confucian temple. When the slope exceeds 17°, the Courtyard enclosure genotype is difficult to implement. In this case, the combination of the other three genotypes makes the guiding space layout fragmented, which is necessary for the significant slope, transforming the Confucian temple into a composition of small volumes associated and articulated with each other. So far, the 23° topographic slope of the Pu’an Confucian temple is the steepest among the existing and officially built mountain Confucian temples in China. No building combination genotype can be carried out on such a steep slope but the Archway Independent genotype.

Table 4. Topographic parameters corresponding to building combination genotypes.

The changeable topographic conditions and the resulting diverse building combination genotypes greatly enrich the visual experience of the courtyard space of mountain Confucian temples. The author analyzes six cases by using Spatial Syntax (VGA) and tries to express the various visual feelings graphically. The detailed process of the analysis is as such. First, to draw plans of the Confucian temple for analysis.; second, import the CAD plan into DepthmapX software to draw visual graphics. For the plan of the Confucian temple with a ground elevation difference of more than 2.5 m, set a “split line”, and adopt the method of layered VGA analysis, which can intuitively reflect the blocking of the sight line in the courtyard with a large elevation difference. () shows the visual graphics of these cases. Regardless of the segmentation of topography and the change of building combination genotypes, it leads to the complexity of high visibility point distribution and different visual feelings such as centripetal, penetration, fragmentation, fragmentation, and other forms.

Table 5. Visual graphic expression of the diversity of Confucian temple spatial layouts.

In one word, the topography operates effectively and directly on the physical configuration of the Confucian temple, especially on a steep slope. From the overall sequence organization to the specific layout of the guiding space, the ideal building standard based on the Confucian rites system is challenged under the natural topography. The Confucian temple spatial morphology adapted to the topography represents a unique artistic achievement.

4. Landscape environment characteristics suitable for mountain Confucian temples

The environmental elements involve plants and the Panchi-centric water system. In the mountain Confucian temple environment, not only the internal courtyard environment is affected by the topography but also the external vertical interface is set as a higher priority. They constitute the two most important aspects of the mountain Confucian temple environment. Based on these sensibilities, the author gives attention to the interior and exterior of the Confucian temple courtyard space and interprets the environmental and landscape characteristics from the vertical dimension.

4.1. Plant configuration characteristics of mountain Confucian temple

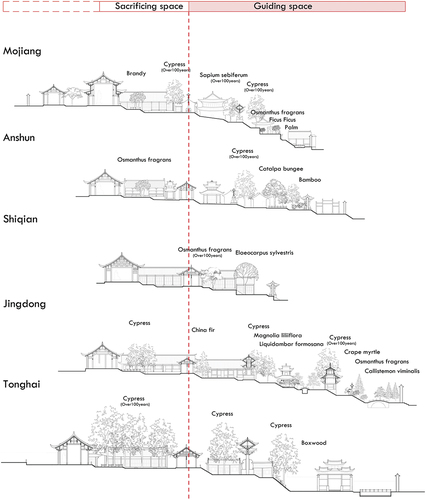

As for the plant configuration of the Confucian temple, it should be clarified that plants are not essential for the Confucian temple, which is different from the strict building standards. It is usually added after the completion of the Confucian temple according to the historical literature. From the fieldwork survey, plants in the Confucian temple in the mountainous area are less than that in the flat area. The steep topography makes it barely meet the basic sacrificial function, providing less space for planting, as the Pu’an Confucian temple proves. Despite the space limitations, most mountain Confucian temples coordinated the relationship between plant configuration and mountain topography properly, carried out greening gradually to set off the atmosphere of the courtyard space, and formed the characteristics of plant configuration of mountain Confucian temples. From the five mountain Confucian temples that are rich in vegetation, the plants were planted in different periods and reflect the sustainability of the traditional Confucian temple plant landscape. The influence of topography on plant configuration is most noticeably in the guiding space ().

Firstly, the plant configuration of the guiding space shows the characteristics of conforming to the terraced platform stratification. The terraced platform stratification divides the guiding space into multiple regions. Each platform has its own relatively independent flora, and the plant distribution shows a trend of horizontal expansion along with the platform. Not only the distribution but also the tree species selection shows differences due to the terraced platform stratification. For example, the distinction between Elaeocarpus sylvestris and Osmanthus blossoms in Shiqian Confucian temple; the distinction between catalpa bungee, bamboo, and cypress in Anshun Confucian temple; the distinction between cypress and Sapium sebiferum in Mojiang Confucian temple. The topography makes the plants fall in layers vertically and expand laterally along with the terraced platform. The interplay of different levels and vegetation makes the plant configuration as sequential as building.

Secondly, planting shrubs horizontally along the cliff face of the terraced platform is a special plant configuration method of the mountain Confucian temple, especially in those cases with large elevation differences. For example, in the plant configuration of the Mojiang Confucian temple, sweet scented osmanthus, ficus, palm, and other shrubs are planted in the front of the cliff surface of the first two floors of the terraced platform, and the edge of the platform is decorated with ground cover plants, which splits into a series of plant landscape that lace the cliff face of the terraced platform. Or the first floor of the terraced platform in Jingdong Confucian temple, Callistemon citrinus, Osmanthus fragrans, and crape myrtle are planted in three layers on the cliff surface. The rich combination of shrubs and trees weakens the topographic elevation difference. In ancient times, the selection of tree species, whether shrubs or trees, was completed by officials familiar with the Confucian ritual system rather than professionals. It leads to the plant configuration in the Confucian temple attaches great importance to the symbolism of Confucian culture but lacks professionalism. This phenomenon shapes the spiritual characteristics of the plant aesthetics of Confucian temples, which reflects the amateur ideal of Confucianism (Levenson Citation1965).

Thirdly, the plant configuration of the mountain Confucian temple not only considers the internal topographic conditions but also pays attention to the visual impact of the external vertical interface. The steep topography of the mountain Confucian temple promotes the external vertical interface to a more important position. According to records in < Local Chronicles of Tonghai in Qing Dynasty Emperor Daoguang period >: “Sun, an education official, passed through Tonghai and paid a visit to the Confucian temple. He praised Tonghai Confucian temple as the top of Yunnan Province of its spacious vision from top to bottom and the solemn and magnificent from bottom to top. The great landscape is not just artificial, but also shaped by the natural topography.” In order to clarify the landscape effect of plant configuration on the external vertical interface, the author tries to investigate the relationship between plant configuration and building combination genotypes on the external vertical interface of the Confucian temple from the height of ancient pavilions and city walls (). Two different plant configuration patterns are noteworthy:

Figure 6. Plant configuration and building combination genotypes on the external vertical interface.

In the Confucian temple with the genotype of Wing room Paralleled and Pavilion Scattered, trees are planted close to the central axis, and the facade of wing buildings and pavilions is deliberately presented. For example, in the guiding space of the Mojiang Confucian temple, the paired planting of Sapium sebiferum and cypress on both sides of the central axis block the Lingxing gate, while the wing rooms and the pavilions are highlighted. Or the four cypress trees in front of the Lingxing gate of the Anshun Confucian temple, which make the wing rooms arranged in parallel on both sides more prominent in the vertical interface. The above plants are ancient trees with a history of more than 100 years, which proves that the consideration of the relationship between plant configuration and building vertical interface has existed since ancient times. The genotype of Wing room Paralleled displays the typical frontal image of a traditional building on the vertical interface. The facade of the pavilion is more ornamental. As recorded in < Local chronicles of Jinning in Qing Dynasty Emperor Daoguang period >: “The pavilion stands in front of the hall like a bird spreading its wings, which is enough to make the Confucian temple magnificent.” These characteristics of building combination genotypes on the vertical interface made ancients put forward appropriate and coordinated plans in plant configuration.

In the Confucian temple with the genotype of Archway Independent, we come across a disparate plant configuration pattern. The plants comply with the terrace and plant laterally on both sides of the courtyard far from the center axis, shielding the buildings on both sides. The memorial archway raised by the topography on the central axis is particularly prominent on the vertical interface. Jingdong Confucian temple and Sinan Confucian temple are representative cases. Jingdong Confucian temple is located in a mountain with dense forest. Cypress trees block the buildings on both sides, making the Sishui archway and the pavilion behind it protrude from the grand mountain forest and point to the background peak. The integration of Confucian and Feng Shui concept is manifest in the planning of the site and the Confucian temple of its monuments, which unifies the humanities and natural landscape.

There is no doubt that topography and resulting diverse building combination genotypes have played a leading role in the plant configuration of mountain Confucian temples. Although human beings have given plants the long-standing renewal and evolution throughout history, the plant configuration principle in different periods has a certain inheritance. Because the topographical feature has marked the relationship of the Confucian temple with their Plant landscape from earliest times to the present day.

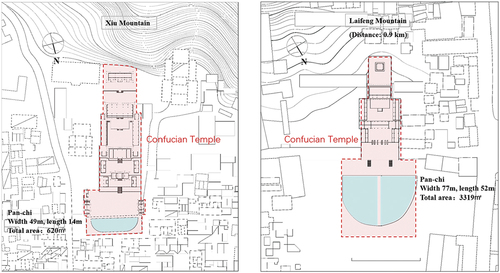

4.2. Water environment of the mountain Confucian temple

Confucianism advocates water, and the water environment of the Confucian temple is mainly reflected in Panchi. Panchi is a semicircular pool, which locates in the front part of the guiding space of the Confucian temple. It is endowed with ritual significance related to teaching. For the mountain Confucian temple in Southwest China, the natural water system at the foot of the mountain has become one of the choices to create an ideal Pan-chi. It is not only in line with the Confucian temple building standard but also can shape the environmental pattern of “ Fronting water and with hills on the back “ for the Confucian temple, which is the most advocated in the Feng Shui concept.

Tonghai and Tengchong Confucian temples are two suitable cases for exploring this phenomenon. Tonghai Confucian temple is fronting the lake with Xiu mountain on the back. Local officials in the Qing Dynasty reconstructed the lake for a long time and built stones on the bank to strengthen it. According to < Local Chronicles of Tonghai in Qing Dynasty Emperor Daoguang period >: “Tonghai Confucian temple is fronting the lake with a mountain on the back. Confucius’ morality is as high as the mountain, and Confucianism is as profound as the lake.” Pan-chi in Tengchong Confucian temple is also transformed from the lake. According to < Local Chronicles of Tengchong in Qing Dynasty Emperor Qianlong period >: “The Confucian temple should face the south according to the rites system. The northwest orientation of the Tengchong Confucian temple is caused by the Feng Shui concept. The Panchi is transformed from the Dache lake, and the site is surrounded by mountains, which gives the Confucian temple a magnificent appearance.”

Panchi, which is transformed from natural rivers, has two characteristics: large scale and irregular shape. Concerning the scale of Panchi, the Panchi width listed by Kongzhe is usually between 6–20 meters, there are four larger ones, including the Pan-chi of Jiangyin Confucian temple (width 30 m, depth 13.4 m), the Pan-chi of Jiading Confucian temple (width 42 m, depth 12.5 m), the Pan-chi of Jiangning Confucian temple (width 32 m, depth 16 m) and the Pan-chi of Anfu Confucian temple (width 30 m, depth 24 m). Compared with the Pan-chi in the mountain Confucian temple, which is transformed from natural lakes, the scale of the above Pan-chi is slightly inferior. The Pan-chi in Tonghai Confucian temple is 49 m wide and 14 m deep, with a total area of 620 square meters; The Pan-chi in Tengchong Confucian temple is 77 m wide and 52 m deep, with a total area of 3319 square meters (). The long-term existence of the grand Pan-chi water system is not only due to the original scale of natural lakes but also to the drainage system of the mountain Confucian temple that drops the rain into the Pan-chi, promoting its water circulation. The open water of Pan-chi transformed from natural lakes reflects the vertical interface of the mountain Confucian temple, further enhancing the external visual effects of the Confucian temple. Tonghai Confucian temple is located in a heavily wooded Xiu mountain forest, the Open water of Pan-chi reflects the protruding archway and the outline of the mountain behind it. Under the natural scenery pattern, Pan-chi does not need to coordinate with the scale of the building complex, but more like a natural element to create the impressive scenery. The Lingxing archway has also been enlarged, and its reference on the vertical interface is no longer other single buildings in the Confucian temple, but the magnificent mountains and forests behind it. The highly Fusion of Nature and Artificiality is the most noticeable strategy of the mountain Confucian temple environment. Its manifestation in the Confucian temple and the role of useful criteria in creating a constructive relationship with the context is impressive.

5. Discussion

5.1. Reflection on the separation of oriental cultural and natural heritage

The research on the space and environment of mountain Confucian temples in Southwest China reveals the integrity of Oriental culture and natural heritage, which is enough to trigger international reflection on heritage classification. < Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage >, approved during the UNESCO conference in 1972, classifies heritage types according to cultural and natural attributes. It results in the artificial separation between the natural and cultural values of many heritages and deliberately pushes culture and nature to more opposite extremes. This classification poses a challenge to the protection of Oriental architectural heritage represented by China, which was formed under the concept of “Unity of Man and Nature”

Firstly, buildings and their surroundings have notable connectivity in Chinese traditional mountain temples, the natural topography is the framework that unites architecture and natural landscape. The traditional Chinese temple architecture, which is known for the courtyard type combination of small buildings, shows more flexibility in the face of complex topographic conditions. The mountain Confucian temples in Southwest China show the unique charm of the combination of Oriental building complex and topography. The innovation of the location and combination of single buildings in the Confucian temple courtyard has brought a diversified spatial layout. This reflects the connection between architectural culture and nature, which exceeds the Confucian rites system. Moreover, the topography makes the originally gradually presented courtyard spaces (Li Citation2005) display on the vertical interface directly and forms a magnificent landscape under the coordination of water system and plant configuration. In this landscape, the Confucian temple seemed like growing from the foot of the mountain, which is indivisible from the natural environment.

Secondly, China’s inherent Feng Shui concept brings traditional architecture and the natural beauty of mountains and rivers closer. It has a set of ideal pursuits for the height and shape of the mountains around the buildings, as well as the location and flow direction of the river. For the Confucian temple built down the hillside, the macro landscape pattern is not only an important prerequisite for the construction of the Confucian temple but also an important part of the external macro-environment in its long development. By divination following the geographical and morphological features of the topography, the ancient builders expressed the distant view of the Confucian temple through the view of the mountain, further blurring the boundary between artificial buildings and the natural environment.

5.2. Suggestions for the protection of the mountain Confucian temple heritage

The protection of the diversity of courtyard space and environment of mountain Confucian temples should be taken seriously in the protection of Confucian temple architectural heritage. The diversity and complexity brought about by the topography is a reminder to the academic circles that the standardization trend of the Confucian temple is not definite. The Confucian temple building standard is far less rigid and fixed than previously thought, especially under the influence of natural factors that are beyond the Confucian rites system. Each mountain Confucian temple building has a spatial organization and layout that match the mountain topography and the external macro-environment, and the corresponding environmental shaping is more changeable, which should be given extra attention in the building restoration. Moreover, mountain Confucian temples exist not only in Southwest China but also in other mountainous areas of China and other East Asian countries. Changeable topography and the differences in building standards in various regions will greatly enrich the value and connotation of Asian Confucian temple architectural heritage. The establishment of the database of this architectural heritage type is necessary, although it will be a long-term work involving international cooperation. In addition to the existing architectural heritage of mountain Confucian temples in various regions, the integration of Archaeological Relics will help us understand the construction practice of the Substantial numbers of mountain Confucian temples that have disappeared in history. The extraordinary wisdom of the combination of architecture and topography still has reference significance in today’s mountain architectural design. The difference between traditional architecture and the View of Nature in East Asian countries will enlighten today’s architectural design with national characteristics.

Protection of the natural environment and the single building is equally important to inherit the value of mountain Confucian temples. The natural environment has a multiscalar role inside and outside the Confucian courtyard space. Inside the courtyard, plants and water systems play a role in setting off the sacrificial atmosphere and symbolism. Outside the courtyard, with the rising of the topography, the view opens to the mountain opposite and goes beyond the building complex, extending through the city. Not only the adjacent plants are combined with the Confucian temple buildings, but also the mountain scenery on the back and opposite it is incorporated. The natural environment of the Confucian Temples, shaped by the Feng Shui concept, creates a delicate setting for the sacrifice tradition of Kongzi worship and shapes a respectable city’s landscape as well. Although the concept of Feng Shui is more psychological compensation and has no scientific basis, it is hard to deny the shocking visual effect of the city’s historical landscape created under this principle and its heritage value. However, the survey results show that the current situation of Confucian temple heritage protection is limited to the courtyard space, and the surrounding mountain forest has been damaged by urban development. The integration conservation of architecture and the surrounding environment should be regarded as higher standards for future protection.

he optimal viewing point including the city wall and the public pavilion in the urban space should be affiliated with the Confucian temple heritage protection, which is a targeted strategy for the special viewing angle of the vertical interface of the mountain Confucian temple. The topography projects the vertical interface of the Confucian temple into the urban space. The traditional viewing point of the Confucian temple in the urban space and the related viewing corridor should be continuously and systematically protected in the urban renewal. For the traditional viewing point that no longer exists, proper replacement should be performed in combination with modern urban space. The significance of this strategy is related to the protection of Confucian intangible cultural heritage and spiritual inheritance. These traditional viewing points of the Confucian temple connect a series of natural and artificial creations with people’s spiritual activities, which are related to the past and present Kongzi worship in China. In history, Confucius’s worship and Cultural confidence led patrons to support laborious and expansive construction activities in this startling topography and secluded locale. The unparalleled cultural landscape is presented to the aboriginal people in Southwest China. The related poems, songs, and cultural activities that are carried by the viewing point have become a part of local customs. Ritual and righteousness transformation through education – make different nationalities’ forces coordinated. At present, the traditional custom of the Confucian society gradually disappeared under the drastic changes in urban life. Protection and reproduction of the relevance of viewing points have important implications. It is not only the improvement of the integrity of heritage protection but also the interpretation of the Confucian rites system and literati order in East Asia.

6. Conclusion

The present article, through an inspection of the topographic factor in the development of Confucian temple courtyard space and environment, aims to demonstrate the maxim that a re-reading of the topography in the study of Confucian temple architectural heritage can turn the today’s impoverished panorama described. These Confucian temple cases have different orientations and layouts but a uniform principle that conforms to the topography. In terms of specific space layout, due to the continuous growth and improvement of the guiding space of the Confucian temple, the whole guiding space can be regarded as several independent building combination genotypes, each consisting of main buildings, once again integrated into one temple. Ultimately it shows greater diversity in the spatial layout. The research findings can be summarized as follows:

Conforming to the relationship between mountain and city, the orientation of the Confucian temple is changeable rather than simplify “facing the South”. Meanwhile, the axis of the mountain Confucian temple is generally not a straight line but slightly deflected. And 3° is a common deflection angle in those cases with complex topography. Furthermore, the 4 building combination genotypes have their slope adaptation range, varying from 4° to 23°, which directly affects the visual effect of the guiding space. In addition, interpreting the environmental elements including plants and water systems based on the vertical dimension thinking is innovative. It reveals that the mountain Confucian temple is not only an enclosed sacred center but also a part of the urban historical landscape, which makes us cognizant of the power of mountain landscapes and topographies.

Although the cases involved in this study are only a small portion of mountain Confucian temples in history, they have revealed the Uniqueness and complexity of the space and environment. The richness of the characteristics of mountain Confucian temples in history is unimaginable. This paper is a preliminary study of the remaining mountain Confucian temple in Southwest China and hopes to put an important issue back on the front burner. Further study of mountain Confucian temples in history through literature and archaeological data could be expected. As Naghibi (Citation2021) has mentioned: “The design of topographic space relationships is one of the biggest challenges in landscape, but it also provides creative opportunity.” This is the general rule that spans the eastern and Western architectural cultures and beyond the times.

but

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Chen Xing

Chen Xing is a Ph.D. Candidate at the School of Architecture, Southeast University. As an architectural history researcher, while focusing on the research of traditional temple architecture, he paid special attention to their expression in urban space and the resulting urban historical landscape.

Sun Xiaoqian

Sun Xiaoqian is an Assistant Research Fellow at the School of Architecture, Southeast University. She received a Ph. D degree from Southeast University. Her primary research areas are stone materials of Chinese traditional architecture, the history of Chinese architecture.

Notes

1 Confucius was born at Qufu (Shandong Province), the capital of the state of Lu in 551 BCE. He is a great political and social thinker, his ideas, writings, and moral precepts were codified and provided a basis for Chinese societal and government organization for over 2000 years.

References

- Davidson, L. A. 2016. Inclusive Just War Theory: Confucian and Mohist Contributions. Colorado: Colorado State University.

- Hoshyar, Q. R., and A. I. Ahmed. 2018. Nature and Physical Configuration: A Study of Topographical Influences on the Physical Configuration of Mountain Settlements in the Iraqi Kurdistan Region, 275–285. CITIES’: IDENTITY THROUGH ARCHITECTURE AND ARTS.

- Jang, S.-H. 2005. “A Comparative Study on the Site Planning Structure of Confucian School and Sewon Architecture in Choseon Dynasty.” Journal of the Regional Association of Architectural Institute of Korea.

- JANG, G. E. 2015. “Phenomenological Reading on Symbols of Architecture Space in Korean Traditional Mountain Temples - with Special Reference to BuSeok Sa.” Environmental Philosophy null (20): 99–117. doi:10.35146/jecoph.2015.20.004.

- Kong, X. L. 2011. Research on Confucius Temple All over the World. Beijing: Central Compilation & Translation Press.

- Kong, Z. 2018. Study on the Building Standard of Confucius Temple, 46. Qingdao: Qingdao Press.

- Levenson, J. R. 1965. “Confucian China and Its Modern Fate.” Journal of Modern History.

- Li, Y. H. 2005. CATHAY’S IDEA-Design Theory of Chinese Classical Architecture. Tianjin: Tianjin University Press.

- Naghibi, M., M. Faizi, and A. Ekhlassi. 2021. “Comparative Study of Topographical Research on How the Architecture Meets the Ground in Persian Architecture.” Journal of Building Engineering 41 (2): 102274. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2021.102274.

- Na, L., and J. Park. 2022. “Cultural Heritage Values and Underlying Spatial Characteristics of the Temple of Literature in Vinh Long. Southern Vietnam.“ OPEN HOUSE INTERNATIONAL 47 (2): 282–295. doi:10.1108/OHI-06-2021-0128.

- O’Keeffe, T., and P. Virtuani. 2020. “Reconstructing Kilmainham: The Topography and Architecture of the Chief Priory of the Knights Hospitaller in Ireland, C .1170–1349.” JOURNAL OF MEDIEVAL HISTORY 46 (4): 449–477. doi:10.1080/03044181.2020.1788626.

- Pan, G. X. 1987. Study on Qufu Confucius Temple Architecture. Beijing: China Architecture& Building Press.

- Peng, R. 2011. Architecture and Environment of the Confucian Temple. Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou ancient books publishing house.

- Qu, Y. J. 2000. Research on the Capitals and Local Confucian Temples of the past Dynasties. Beijing: Encyclopedia of China Publishing House.

- Wang, G. X. 2013. Ten Books of Chinese Contemporary Architectural Historians, 697. Shenyang: Liaoning Fine Arts Publishing House.

- Yang, D. Y. 2015. Study on Yunnan Confucian Temple Architecture. Yunnan: Yunnan University Press.

- Zhou, B. 2020. A Study on the Spatial Forms of the Confucian Temple in the Corridor of the “Miaojiang Corridor”. Guizhou, China: Guizhou University.