ABSTRACT

As the major architectural system in Myanmar, the Buddhist architectural heritage in the Ayeyarwady Basin is a concrete representation of the collision and integration of river basin cultures in time and space. The heritage carries the natural, historical, and cultural information of the local society, and reflects the highest achievements of architectural technology and art at that time. This paper takes the early Buddhist architecture in the Ayeyarwady Basin as the research object, adopts methods of literature research, field investigation and architectural typology to integrate the Buddhist resources in the three ancient world cultural heritage cities of Beikthano, Srikshetra and Bagan in different periods. Based on the diachronic analysis, the Buddhist architecture types in the basin are summarized. The main results obtained in this paper are as follows:First, the study points out that the development of Buddhist architecture in the Ayeyarwady Basin is affected by social history, water and land transportation, religious culture and many other factors. Second, it puts forward the basin characteristics of the Buddhist architectural form. Third, it summarizes the creativity in the form and technology of the Buddhist architecture in the Ayeyarwady Basin. Fourth, it reveals the development principles and religious culture of Buddhist architecture in the Ayeyarwady Basin.

1. Introduction

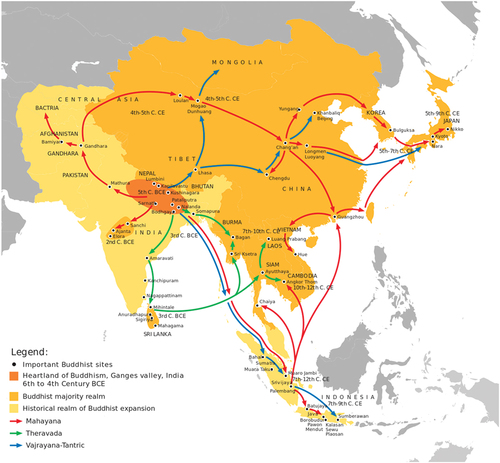

As the largest river in Myanmar, Ayeyarwady runs through the north and south of the territory. On the one hand, it provides abundant water sources, fertile soil and shipping traffic for all regions. More importantly, it serves as the main propagation path to guide the formation and expansion of urban agglomerations, the development of the culture led by Buddhism, the growth of Buddhist architecture driven by core culture.

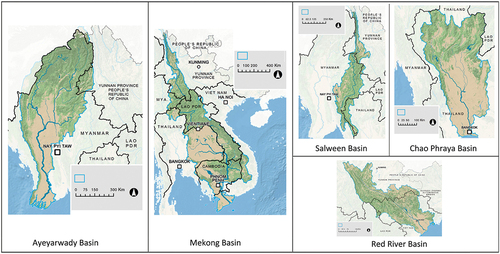

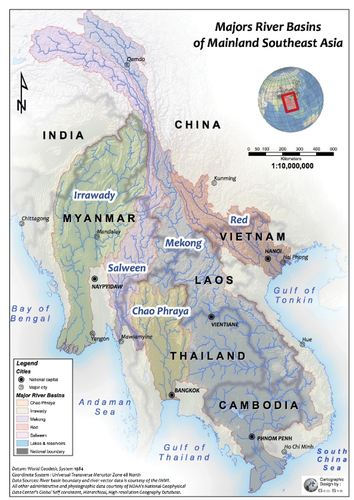

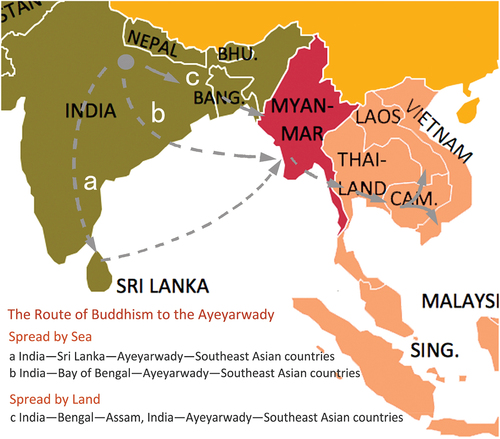

Since ancient times, the Ayeyarwady Basin has established contacts with China, India and other regions of Southeast Asia. It is not only a key hub connecting the cultural and trade routes around the world but also a crucial link and window for us to study the Buddhist architectural heritage in Southeast Asia. Southeast Asia initially accepted the religious culture of India introduced by sea and established national regimes of the Indianisation mode, with the cultural transmission path stretching from the Amaravati Port via the coast of the Bay of Bengal to the Andaman Sea-Western Coast of the Indochina Peninsula and the Malay Archipelago-East Coast of the Indochina Peninsula. Owing to this cultural transmission channel, the lower Ayeyarwady Delta, the lower Chao Phraya Delta, the Malay Archipelago and the lower Mekong Delta became the earliest accepters of Indian Buddhist culture in Southeast Asia (). The ancient Buddhist cities of Myanmar at that time were all developing along Ayeyarwady, and the Buddhist architecture emerging in the basin had a profound influence on the early religious architecture system in Myanmar and throughout Southeast Asia (, ).

Table 1. Overview of the five major river basins in the Indochina Peninsula.

Religious culture constitutes the foundation of the early culture of the Ayeyarwady Basin, while Buddhist culture, as the most important component of the Ayeyarwady culture, has deeply affected the development of Myanmar’s social system, economic trade, art and education (Cady Citation1958). Since the 11th century, Ceylon-originated Theravada has gradually developed into the dominant religious belief in the Ayeyarwady Basin (), being the focus of people’s ideology and the spiritual stronghold of individuals and nations for centuries (Luce Citation1969). As the carrier of the Buddhist culture – the core of geographical relations between Myanmar and Southeast Asia and the rest of the world, Buddhist architectural heritage reflects the natural, historical, economic and cultural aspects of the local society (Frederic Citation1965). This paper presents a spatio-temporal study on the early Buddhist architecture network of the Ayeyarwady Basin with the Buddhist culture as the clue, and the growth and evolution of the Buddhist architecture as the entry point. Moreover, classification and grouping were performed with the typological approach to summarize its development pattern and characteristics of Buddhist architecture, with an attempt to explore the cultural value and architectural innovation vocabulary of the architectural heritage, and interpret the history, geographical relations and cultural composition of Myanmar from a new perspective. This study is of theoretical value and practical significance to promote the conservation and utilization of the Buddhist culture and heritage. Also, it can serve as a research basis for the cultural exchanges and important strategic planning of countries with Myanmar and Southeast Asia.

1.1. Literature review

Starting from the mid-19th century, the Ayeyarwady Basin has drawn attention from scholars engaged in research on cultural relics conservation, archaeology and architecture due to its rich architectural culture and heritage. In previous studies, however, the religious architecture in Myanmar and Southeast Asia where the Ayeyarwady Basin is located was often considered as an affiliate with India (Lall Citation2014), so its internalization development was ignored. Later on, scholars came to realize the symbiosis of indigenization and transplantation of the Buddhist architecture in Myanmar, put forward many relevant research topics, and conducted conservation (Pichard Citation1992; Elizabeth Citation2007). The greatest advances in our knowledge of premodern Myanmar have been made by archaeologists during these 20 years (Michael and Matrii Citation2012; Stargardt Citation2016). It often takes long to move from initial archaeological discovery to theoretical analysis and then to further research.

In 1975, a strong earthquake occurred in Myanmar, and many Buddhist pagodas and temples were severely damaged. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) extended assistance to Myanmar, provided funds and technical support, and carried out conservation mapping for important Buddhist cultural centers in Myanmar. For example, Inventory of Monuments at Pagan, written by Pichard, P., a French scholar, is a set of surveying and mapping collections, totaling 8 volumes (Pichard Citation1992). In 1991, the British scholar Stargardt, J. discovered the importance of Pyu in the history of Myanmar, and compiled The Ancient Pyu of Burma Vo1. I, which made great progress in the study of the ancient country of Myanmar (Stargardt Citation1991).

In 1986, Northern Illinois University was selected to be the Myanmar Research Center by the Myanmar Research Group of the Asian Research Association. In 2003, Richard, M.C., as a member of the Myanmar Research Center of Northern Illinois University, compiled The Art and Culture of Burma, and made a special study on the history of Myanmar’s art and culture (Richard Citation2003). In 2007, Elizabeth, H.M., a British scholar, wrote the professional archaeology book Early Landscapes of Myanmar, which deeply explored the early geomorphic features of Myanmar from the perspectives of archaeology, art and architecture (Elizabeth Citation2007). In 2014, the Department of Archaeology and the National Museum of Myanmar published World Heritage Pyu Ancient Cities: Halin, Beikthano, Sri Ksetra, written by the Ministry of Culture of Myanmar, which briefly introduced the three ancient cities and architectural heritage of Pyu (Ministry of Culture Citation2014).

In addition, archaeological reports include: Report on the Excavation at Beikthano by Aung Thaw, a Myanmar scholar (Thaw Citation1968); The Excavation of Halin by Myint Aung, a Myanmar scholar (Myint Citation1970); From the iron age to early cities at Sri Ksetra and Beikthano and Sri Ksetra, 3rd Century BCE to 6th Century CE: Indianization, Synergies, Creation by Stargardt, J., a British scholar (Stargardt Citation2016).

To sum up, from the existing international research, the study in the field of the Buddhist architecture in the Ayeyarwady Basin needs to be improved, and the problems are as follows:

From the perspective of architecture, a systematic theoretical framework has not been established internationally according to the regional special research on the Buddhist architecture across Myanmar, and the research foundation is weak. In Southeast Asia, a circle with basin culture as its historical development context, there has been no systemic analysis on its Buddhist heritage against the background of the Ayeyarwady Basin, and comparative analysis from a basin perspective is rare. To the overall research, it lacks systematic, thematic, horizontal and vertical theoretical depth. The scope of such research was limited to a country or parts of a city only, the results were not integrated, and the content was mostly simple, making it difficult to grasp the clues to the spatio-temporal evolution of the architectural heritage. The existing relevant research materials mostly come from local archaeological reports or cultural assistance projects. The author hopes that through this study, it can provide assistance for the regeneration of Buddhist architectural resources and the heritage protection in Myanmar in the future, and pave the way for the research direction of systematically constructing Southeast Asian historical cities and buildings.

However, the scope of such research was limited to a country or parts of a city only, the results were not integrated, and the content was mostly simple, making it difficult to grasp the clues to the spatio-temporal evolution of the architectural heritage. In Southeast Asia, a circle with basin culture as its historical development context, there has been no systemic analysis on its Buddhist heritage against the background of the Ayeyarwady Basin, and comparative analysis from a basin perspective is rare.

1.2. Regional analysis

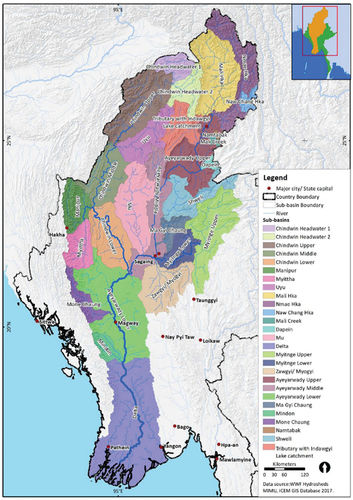

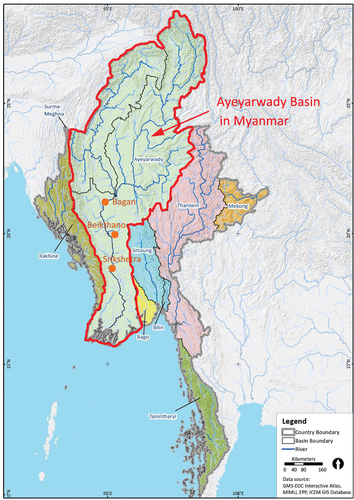

Ayeyarwady, the mother river of Myanmar, has both geographical and historical significance to Myanmar: it is specially located in the country and reflects the country’s history. The river stretches about 2,174 km and covers a basin area of 410,000 km2, accounting for 60% of the entire Myanmar.

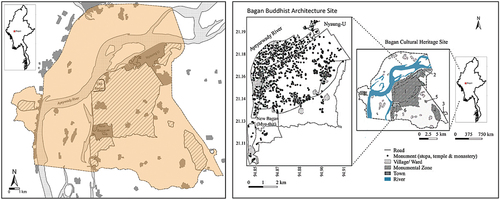

The ancient maritime trade started from India, passed across the Bay of Bengal, and reached the ancient country of the Mons in Southern Myanmar, and then developed along Ayeyarwady to the north. The lower reaches of Ayeyarwady served as a trade hub connecting China and Southeast Asian countries (). The route extended upstream along Ayeyarwady and connected to the Southern Silk Road, running through Myanmar and connecting it with other countries by the Ayeyarwady waterway. The sea-land trade network linked China, Myanmar and India closely and lifted the curtain for the political, economic and cultural exchanges among the three countries since then (Elizabeth Citation2010). The courier stations along Ayeyarwady saw the gradual advent of village settlements, large cities and Buddhist centers. The rise and boom of ancient kingdoms in Myanmar, such as the Pyu Kingdom and the Bagan Dynasty, were based on this trade network (Ministry of Culture Citation2014; Thaw Citation1972). Meanwhile, the key node cities along Ayeyarwady were also Buddhist cultural exchange centers under the sea-land trade network, spreading to Southeast Asia, India and China and setting the stage for cultural exchanges between Myanmar and various places. This paper mainly focused on the Buddhist architecture in the three ancient capitals of world cultural heritage in the Ayeyarwady Basin, i.e., Beikthano, Srikshetra and Bagan (). Among them, Beikthano and Srikshetra were two most important capitals of Pyu Kingdom. According to the latest archaeological research, the operation time of these two cities can be traced back to the first century AD or earlier (Hudson and Lustig Citation2008; Hudson Citation2019; Stargardt Citation2020). The evolution of Buddhist architecture in Bagan during the Bagan Dynasty had a profound impact on the development of traditional buildings in Myanmar and Southeast Asia.

2. Methods

2.1. Historical data collection and literature research

In this study, by reviewing ancient books, annals, journals, academic monographs and other literature related to the Myanmar Buddhist architectural culture, we intend to accurately regenerate the historical information, city structure, cultural trend and architectural style of various periods in the Ayeyarwady Basin, compare and summarize the historical information of each period, collate the research results of each period, identify the historical space context and evolution logic of the Buddhist architecture in the Ayeyarwady region of Myanmar, and summarize existing problems to provide a foundation for subsequent analysis.

2.2. Field research

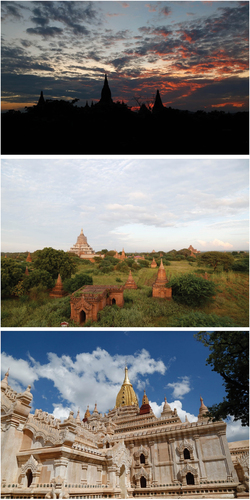

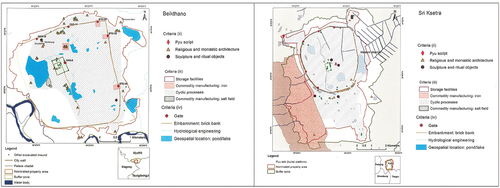

Field research was conducted to explore the spatial pattern, site selection and layout, styles and features, and carving art of the Buddhist architecture in the ancient cities of Beikthano, Srikshetra and Bagan of the Ayeyarwady Basin (); and first-hand information was obtained through fieldwork, on-site experience, interviews with residents and experts. Equipment such as multi-type UAVs and 3D laser scanners was used to conduct elaborate surveying and mapping of the Buddhist buildings in the ancient cities. Moreover, a variety of software was employed for data processing to acquire high-precision orthographic images, topographic maps and ancient architecture surveying diagrams, and to serve as an empirical basis for literature research.

2.3. Architectural typology and inductive comparison

This paper summarized the early Buddhist architecture system in the Ayeyarwady Basin from a horizontal perspective (society, history, religion, culture) and a vertical perspective (time). The Buddhist architectural heritage of various periods in the Ayeyarwady Basin were classified by applying the theories and methods of architectural typology. Additionally, this paper interpreted the “type selection” of the Buddhist heritage of various periods through refining and screening, extracted architectural prototypes, and analyzed the derivative style in each type and the causes for the conversion among different types. Such prototypes all feature uniqueness, relative stability, overall consistency and certain durability. Next, this paper conducted comparative analysis between this basin and adjacent river basins in Southeast Asia, to deduce the originality of the Ayeyarwady Basin, probe into the in-depth structure and change patterns that are reflected in the Buddhist architectural forms and determine its formal development; the study also intends to inspire architects to delve deep into the social effect, intrinsic value and historical and cultural continuity of the architectural heritage in this basin.

3. Development and evolution of Buddhist architecture in the Ayeyarwady Basin

Early Buddhist architecture in the Ayeyarwady Basin mainly come in three forms: stupas, temples, and viharas. Stupas and temples show obvious basin characteristics and originality, and are thereby the focus of this study (). The word “stupa” originated from India, and stupas in the Ayeyarwady Basin have evolved with the development of Buddhism (Williams Citation2010). Temples have an architectural structure similar to ziggurats. Compared with stupas that are in essence oblatory structures, temples have an interior space to accommodate Buddhist statues and prayers; Buddhist followers can pay homage around the Buddhist statues in the main hall, with an essential unity of function with the “curling” function of stupas.

3.1. The Pyu Kingdom (Before the 9th century AD)

The Pyu Kingdom was the earliest country with a recorded history in the Ayeyarwady Basin and one of the earliest countries where Buddhism was introduced in Southeast Asia (Stargardt Citation1991). The Pyu Kingdom made Beikthano (Magway Region) its capital in the early stage and set its capital in Srikshetra (Bago Region) later. Both cities reflect the characteristics of the urban planning system and the architectural style of the Pyu Kingdom over centuries (). This ancient country was destroyed by Nanzhao in 823 AD. The territory of the Pyu Kingdom in its heyday “extended from the Salween Basin in the east to Arakan and the present-day Manipo of India in the west, bordered Nanzhao in the north and adjoined the Bay of Bengal in the south”, according to historical information. Its vast territory covered the entire Ayeyarwady Basin. “There are hundreds of temples, the bricks are made of colored glaze, and painted with gold and silver … an emperor’s residence is nothing more than that”, according to The New Book of Tang Biography of the Pyu Kingdom (Ou and Song Citation1975). Ma Duanlin wrote in an article about the Pyu Kingdom in Literature Research that “boys and girls have their hair shaved at the age of seven … comprehend the principles of Buddhism, and become residents again” (Ma Citation2011). The literature showed that Buddhism was very popular in the Pyu Kingdom and temples were built all over the country ().

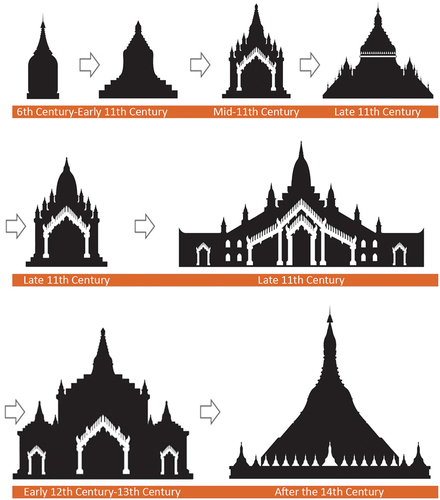

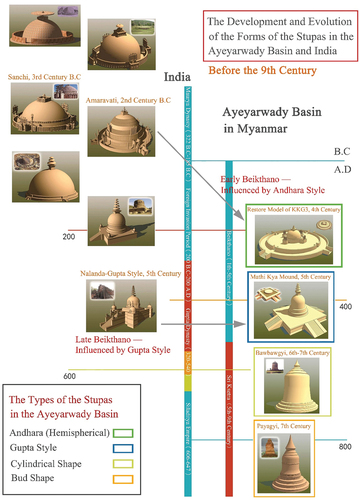

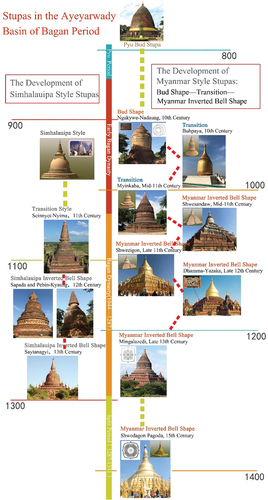

Initially, the stupas of Beikthano and Srikshetra in the Ayeyarwady Basin in the Pyu Kingdom were constructed on the prototype of the Amaravati Stupa (3rd to 2nd century BC) in the reign of Ashoka the Great. Later, influenced by the Gupta Empire (4th to 6th centuries AD), the building volume was elongated and the offering function of Indian stupas was maintained (Cooler Citation2003). In general, the changes in stupas from the Beikthano period to the Srikshetra period were mainly concentrated in the stupa body, and the stupas can be divided into four types: a. Hemisphere in the early Andhra (1st to 4th century AD); b. High dome shape in the Gupta Empire (5th to 6th century AD); c. Cylindrical shape (6th to 7th century AD); d. Bud shape (7th to 11th century AD) (, ). The gradual elongation of the inverted bowl increased the vertical proportion and the building height, which was based on the religious attribute of the buildings and followers’ respect for the Buddhist architecture, and was the external architectural representation of the conceptual change from “towards death” as a tomb in the original significance of a stupa to “towards life” as given by Buddhist followers.

Table 2. The evolution of the stupa characteristics during Pyu period.

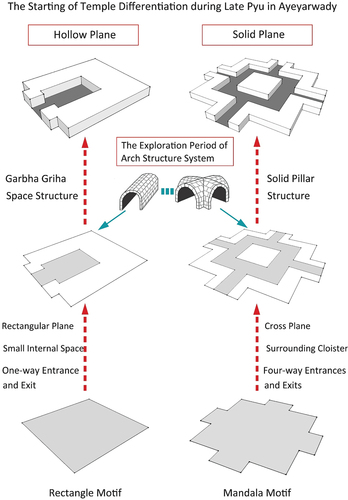

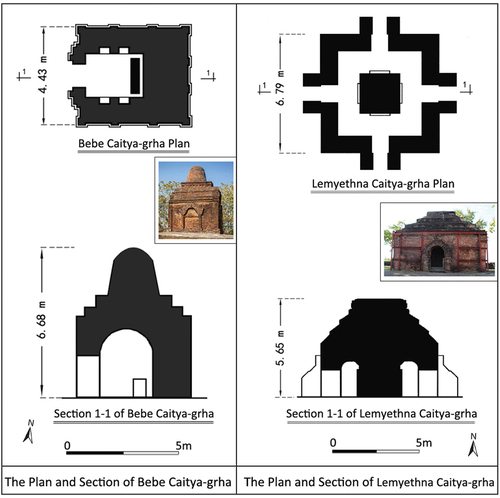

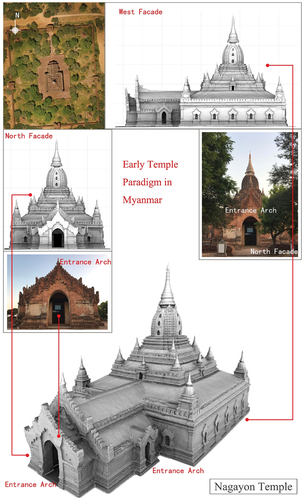

The development of Buddhism contributed to the advent of temples that had inner halls and could be used for worship (Buddha statues were enshrined and Buddha murals were painted inside) to meet the functional requirements. The temples in the Ayeyarwady Basin had a relatively fixed type in the early stage, which was mainly influenced by the Indian Brahmanism architecture. The characteristic of multi-component mixing of the Buddhist architectural form in the Ayeyarwady Basin was highlighted by the advent of main halls with Mandala graphs and the structure of a roof stupa (Thaw Citation1968). Besides, the arch technology was extensively applied to the temples in Srikshetra. Artisans tried to cover the interior space scientifically with various types of brick arches, which laid the foundation for the construction of large temples after the 11th century. For instance, the interior space of the small temple Yahanda-Gu adopted the arch structure, but its arch had a weak bearing capacity and a narrow span, so such a practice can only be seen as “the initial stage of the arch crown technology – an attempt to find a way to cover the interior space” (Lat Citation2010). After the 7th century AD, the Pyus started to adopt the method of steep laying of steep bricks to the construction of temples such as East Zegu caitya-grha, Bebe caitya-grha and Lemyethna caitya-grha, where the interior space was enlarged by increasing the load-carrying capacity with the help of the keystone. In the Ayeyarwady Basin, another innovation of the Pyus was a planar system of the “solid” type. Such structure brought an end to the use of the hollow garbhagriha chamber plane with Brahmanism characteristics in the early period and switched to the use of a masonry entity in the center of the inner hall for weight-bearing. An example is Lemyethna caitya-grha (built in the 7th-8th century AD), which had a large square column at the heart of the square Buddhist hall to support the heavy sikhara on the roof and became the prototype of large temples in the Bagan Dynasty ().

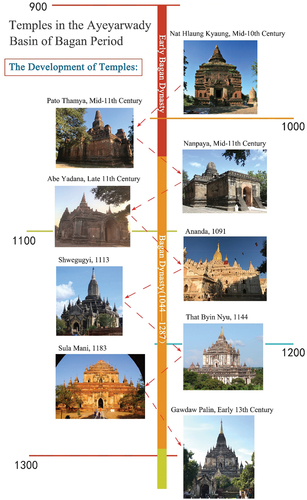

3.2. The Bagan Dynasty (11th to 13th century AD)

In 1044, King Anawrahta made Bagan the capital of his country and founded the first multi-ethnic (Bamar, Pyu, Shan, Mon and other nationalities) unified feudal dynasty in the history of Ayeyarwady. Bagan quickly became the gathering point of political culture and architectural art in the Ayeyarwady Basin and the development center of Theravada in Southeast Asia during this period, exerting a profound impact on the development of the Buddhist architecture and the social progress of various river basins. In February 1287, the army of the Yuan Dynasty captured Bagan, and the Ayeyarwady Basin entered a period of disintegration (Strachan Citation1990). Over the 200 odd years of the dynasty’s existence, many Buddhist buildings were constructed within a radius of 50 kilometers in the plain of the capital city of Bagan, and more than 2,200 buildings are well preserved so far, including stupas, temples and a small quantity of viharas (). These buildings saw a rapid development from the 11th to 12th centuries and became stable in the 13th century, which marked the completion of the evolution process from Indian characteristics and Ceylonese characteristics to localization (with the characteristics of the Ayeyarwady Basin).

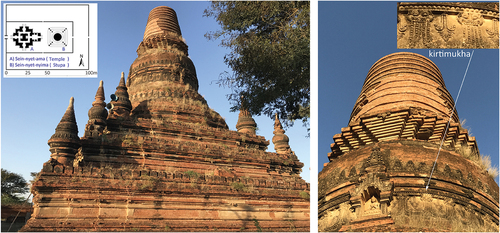

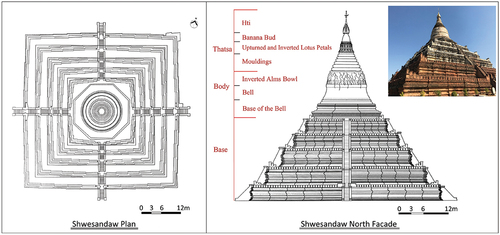

Due to the impact of the Pala Dynasty (8th century AD) and the shape of the stupas in Ceylon, the stupas of Bagan can be divided into four types according to time series: 1) Bud shape (7th to early 11th century AD); 2) Transition from the bud shape to the Myanmar-style inverted bell shape (early 11th century to mid-11th century); 3) Myanmar-style inverted bell shape (after the mid-11th century); 4) Sinhalese-style inverted bell shape (late 11th century to late 13th century, Ceylon was the direct source) (). The stupas of the Pyu, Mon, Myanmar, Ceylon and other nationalities appeared in different forms in the basin cultural environment. The mutual collision and integration among them ultimately induced the formation of the Myanmar-style stupas, such as Shwesandaw (built in the mid-11th century) (), Shwe-Zigon (built in 1090), and Mingalazedi (built in 1284). Compared with the stupas of Indian and Ceylonese styles, the most significant change in the Myanmar-style stupas was that the inverted bowl was directly covered with a sourin, without harmika, making the overall streamline smoother. In the subsequent many centuries, adjustments were made to the details of the shape of the stupas in the Ayeyarwady Basin based on the Myanmar-style stupas of the Bagan Dynasty.

Figure 17. The plan and facade of Shwesandaw Paya (mid-11th century), Myanmar-style inverted bell shape.

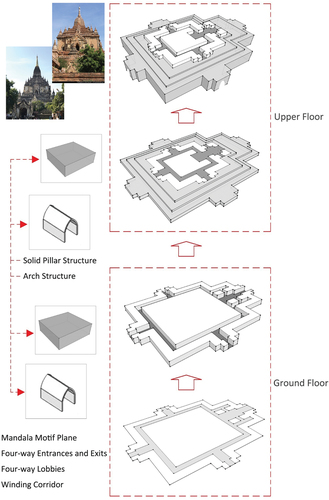

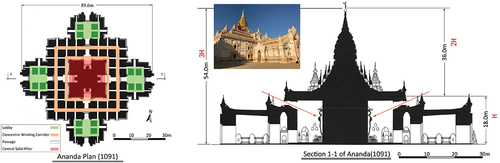

The architectural function of temples changed, from temples with small-sized and single inner halls to large and medium-sized temples with entrance halls, porches, central winding corridors and independent shrines (, ). The wall changed from thick to thin and the space changed from dark to bright (). Finally, the local architectural form of the river basin was formed.

Table 3. Changes in the temple style in different periods of the Bagan Dynasty.

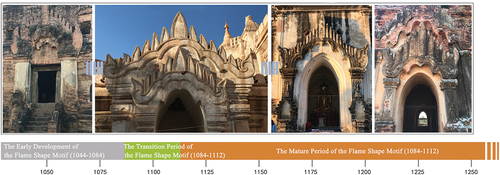

Due to the impact of India, the overall architectural style had obvious Hindu characteristics. For instance, multi-layer retracting-inward terraces were built on the roof of the inner hall, small stupas were built on the corner of the terrace, a high and corncob-shaped sikhara was often built in the middle of the roof, and the form was similar to that of the Hindu temples of South India in the 6th century AD. Also, the composition techniques of the Pala period can be strongly felt from the carving and murals on the inner and outer wall surfaces of such buildings. An example is the kirtimukha at the cornice of the outer wall, which resembled the lime sculpture of Hindu temple ruins in eastern India. Mon-style herringbone decorations, shaped like flames or monster’s fangs, were carved at the temple entrance and exit, on the window sashes, and above the arch of the niche for Buddha, as well as Buddha statues and various auspicious beasts. This arch motif was widely used in the temples of the middle and later periods of the Bagan Dynasty (). It was generally square or cross-shaped in the plane, with porches, entrance halls, entrances and exits on one side, the opposite side, or on four sides. The space from the porch to the entrance hall to the inner hall gradually increased and broadened layer by layer, which symbolized a transition from secularity to sacredness and highlighted the sense of moving forward and orderliness ().

4. Results

After collation and comparison, this paper abstracted the characteristic vocabulary of the early Buddhist architectural heritage in the Ayeyarwady Basin.

4.1. Principles of site selection and layout by basin

4.1.1. Constructed facing the water (relying on Buddhism and the local water worship belief system)

In the Ayeyarwady Basin, the site selection of stupas and temples based on the principle of being built facing the water and constructed by the river was closely related to the national belief of water worship. On the one hand, the world and all Buddhas were born in the water; on the other hand, the holy water bringing purification and rebirth leads the pilgrimage route and symbolizes life and rebirth. Ayeyarwady runs from south to north and has numerous tributaries, making its historic significance, cultural nature and sanctity beyond doubt. Architects endowed the architecture with the sanctity of water through the integration of the relationship between the Buddhist architectural space and the Ayeyarwady basin, thereby arousing the cultural core of the architecture and making the architecture a place of spiritual transformation. For instance, Shwezigon, Lawkananda, Abe-Yadana and Nan-Hpaya were all built along the river, and the latter two had the entrance and exit set in the direction facing the water. Such layout of setting entrances and exits on the west side of temples was different from the east-facing architectural form prevalent in India and Southeast Asia. Its uniqueness was the joint result of the Buddhist belief, geographical environment and local water culture. Apart from Ayeyarwady, other natural lakes and artificial reservoirs and water ponds in the basin were also the elements to be taken into account for the selection of architectural orientation. Besides, for some temples in the Ayeyarwady Basin not built near the water, artisans would introduce water sources through etiquettes and regulations.

4.1.2. Constructed on highlands (relying on the mountain worship belief system in Buddhism)

The faith of holy mountain worship prevailed in Southeast Asia (Stadtner Citation2011), which was widely spread among the people and became one of the important factors for the site selection of Buddhist architecture. Therefore, Tantkyitaung, Tuyintaung and some other mountains became the auspicious places to construct Buddhist buildings in Ayeyarwady.

4.1.3. Constructed in loose layouts (relying on the divination system of Buddhism)

Apart from the two site selection principles of being constructed facing the water and constructed on highlands, there are many Buddhist buildings scattered far away from mountains, rivers and cities in the Ayeyarwady Basin. The seemingly loose layout is, in essence, a divine omen to awaken the land through the medium of auspicious beasts or other auspicious sacred objects in the Buddhist doctrine. As mentioned above, the intention of building the Shwe-Zigon paya was to “enshrine the frontal bone relics of the Buddha and later preserve the Buddha’s teeth returned from Ceylon.” It is one of the most important stupas in the Ayeyarwady Basin due to its great significance in the rank of the consecrated objects, architectural style and construction time. In addition to the principle of being constructed facing the water, the site selection of the Shwe-Zigon paya also followed the auspicious beast worship principle of “building the stupa where the white elephant prostrates”. It was described in Hmannan Yazawin that Anuruddha placed the Buddha’s frontal bone on the back of the white elephant and let it roam, and vowed that the place where the white elephant prostrated should be the place for the stupa. This site selection principle relying on the divination system of Buddhism revealed the reasons for the loose layout of the Buddhist architecture in the Ayeyarwady Basin.

4.2. Originality of the solid plane

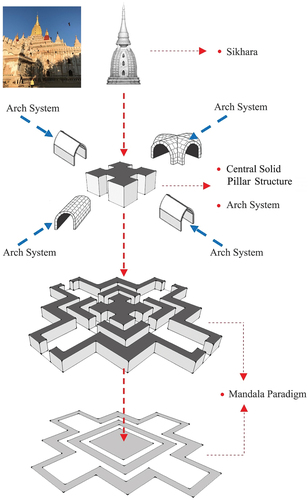

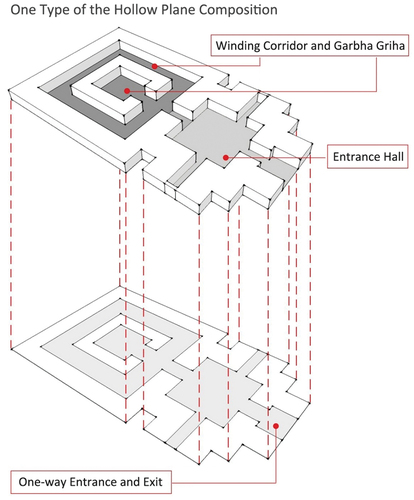

The Buddhist architecture in the Ayeyarwady Basin followed the Mandala paradigm in the plane, focused on the convergence from four directions to the center in space, and developed a unique local style system based on this, with the temple plane being the most typical. The temple plane of this basin is mainly divided into two types: 1) “Hollow” plane without column support: such garbha griha chamber form followed the Indian style and resembled the temple plane of other basins in Southeast Asia, and there was either a single inner hall or an extended ring corridor (there was a plane form in which the winding corridor walls were replaced by columns) (). 2) “Solid” plane with central pillars: Such plane form is different from that of the temples in other basins and marked a localized innovation of the Buddhist architecture in the Ayeyarwady Basin ().

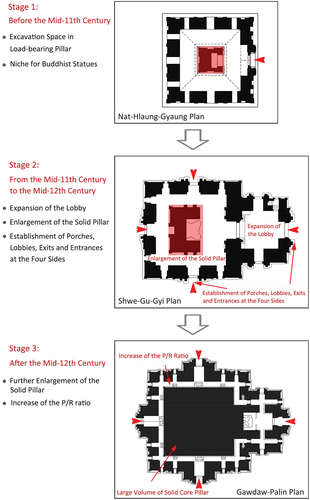

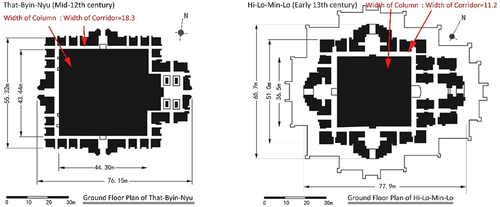

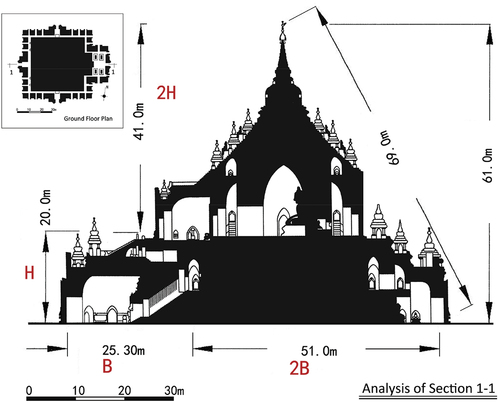

The solid plane system, where a brick pillar was built in the center of the inner hall to bear the load of the sikhara above the roof, with a veranda circling around, was invented by the Pyu Kingdom and made great progress in the Bagan Dynasty. The fact that this type has not been found in Indian temples is the proof of the de-Indianisation mode in the Buddhist architecture of the Ayeyarwady Basin. There are mainly three stages: 1) The solid pillar was small in volume, the wall of the outer wall surface was thick, the pillar width-to-corridor width (P/R) ratio was between 1 and 4. For instance, the P/R ratio of Nat-hlaung-gyaung and Gubyauk-Nge was about 1.2. 2) The temples saw a development from unidirectional lobbies and entrances to four-directional entrance halls, porches and entrances, the vestibule was expanded, and the solid pillar was widened, such as Shwe-Gu-Gyi. 3) The area of the central pillar was broadened and the load-bearing capacity increased to construct high, multi-storey, large temples, and the P/R ratio was greater than 10. For instance, the P/R ratio of That-Byin-Nyu was 18.3 and that of Hi-Lo-Min-Lo 11.2 (). Furthermore, polygonal planes such as pentagon and octagon were derived from the square inner hall and the central pillar also changed in shape.

4.3. Arch technology system

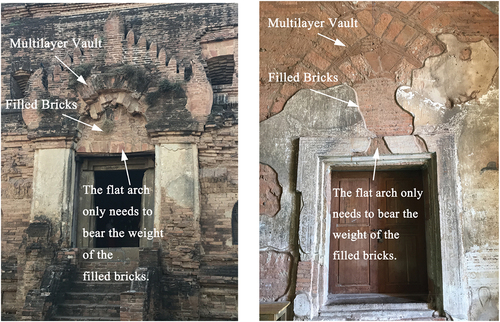

The arch technology was commonly used in the brick Buddhist buildings that covered the Ayeyarwady Basin and contained internal spaces to support large-volume roofs and top stupas. The specific development consists of the following four types: 1) Flat arch; 2) Corbel arch; 3) Tube arch (including the semi-tube arch, single-tube arch, cross-tube vault, multilayer tube vault); 4) Pointed arch (single-pointed arch, cross-pointed arch, multilayer pointed vault) (). The various types of arches met the load-bearing requirements of different parts. The analysis is detailed as follows: The flat arch and the corbel arch were mostly used in small-span spaces such as entrances, doors, windows, and the niche for Buddha. Sometimes, in order to reduce the load of the flat arch, artisans would continue to superimpose flat arches or supplement pointed arches and tube arches to help bear the upper weight. The gaps between the flat arch and the pointed arch and the tube arch were filled with bricks, and at this moment, the flat arch only had to bear the load of the filling bricks ().

The strong load capacity of the cylindrical arch and the pointed arch made them suitable for spaces of various spans, such as the entrance hall, corridor, and inner hall. The span of arches was generally about 7.5 m and can reach 8.64 m at the maximum (Royal Historical Commission Citation2010). The masonry materials have the following three types: 1) Brick masonry. A keystone was embedded in the center of the arch and gravels were used locally for reinforcement. For instance, when a pointed arch was built between the walls of the inner hall, a keystone was inserted in the center of the arch, and imposts were built at the junction of the wall and the arch body, so the load of the arch crown was shared by the keystone, imposts and the surrounding wall. As such, a solid roof structure and open interior space were formed. 2) Bricks and stones masonry. The stones were longer than the bricks to be embedded into the wall and a keystone was built in the center for reinforcement (). 3) All-stone masonry. The tube arch and the pointed arch have a similar application scope and masonry principle, but the pointed arch is more common due to its smaller lateral thrust and smaller structural load. Subsequently, multilayer arch crowns emerged to increase building height and reduce the structural load of the pointed arch and the cylindrical arch, including 1) partitioned multilayer arch crown; 2) contact-type multilayer arch crown.

5. Conclusion

Ayeyarwady is located at the intersection of Chinese and Indian civilizations and once welcomed the spread of the three major sects of Buddhism, making its local culture rich and strong and integrated with other composite cultural systems (He Citation2015; Dong, Citation2015). The Buddhist architecture spread from India to the Ayeyarwady Basin of Myanmar, underwent early development in Beikthano, Srikshetra and Bagan, and gradually evolved into the Ayeyarwady local style after the mutual collision, exclusion, absorption and integration of various forms among the Mon, Pyu and Myanmar people and other nationalities and regions. On the one hand, the deconstruction and remolding of the form and technology of the Indian religious architecture by the Ayeyarwady people led to the localization of the Buddhist architecture, which was best proved by the originality of the planar system and the once-prevalent arch technology system. On the other hand, influenced by the ideological concept of accumulating merits, the increased building volume, the growing complexity of the decorative motif and the trend of the exterior appearance toward gorgeousness reflected the secularization process of the Buddhist thoughts and theories in the Ayeyarwady Basin.

The innovativeness of this paper is summarized as follows.

First, this paper explores a new research field. The Ayeyarwady Basin originating from southwestern China is the critical node and hub for our research on the historical architecture in Southeast Asia, and its core architectural system – the Buddhist architecture – reflects the highest achievements of the social, historical and religious context and the local workmanship. Previous studies on this field are scarce. Thus, this study on the early Buddhist architecture in the Ayeyarwady Basin is a breakthrough in this research field.

Second, this paper put forward the basin characteristics of the Buddhist architectural form. The cultural and architectural expansion of the Indochina Peninsula countries in Southeast Asia exhibits the trend of basin development in combination with local characteristics. Based on this research background, this paper analyzed the types of the early Buddhist architecture in the Ayeyarwady Basin with the typological approach, then concluded the basin evolution characteristics of its Buddhist architecture, and preliminarily constructed a basin research network for the Buddhist architecture in Southeast Asia, represented by the Ayeyarwady Basin.

Third, this study summarized the creativity in the form and technology of the Buddhist architecture in the Ayeyarwady Basin. The comparison of Buddhist architecture in this basin with other regions shows: (1) The principles of basin-based site selection and layout include construction facing the water under the water worship belief, construction on highlands under the mountain worship belief and construction in loose layouts under divination. (2) Myanmar-style stupas supported by a large-volume base and without harmika had smooth and beautiful architectural outlines. (3) The Buddhist buildings in this basin are distinct from the planar system with a central solid pillar of the temples of the basins in India and the Indochina Peninsula. (4) The interior space of the buildings is covered with a unique arch structure system, which is combined with the “solid” planar system to jointly create conditions for the construction of large-volume temples in the Ayeyarwady Basin.

Limited by objective factors such as the article length and time, and subjective factors such as the authors’ research perspective in the course of this study, the following problems remain to be further discussed and studied:

First, the research requires detailed and in-depth analysis. Unlike the case study on urban architecture, research on basin architecture requires the collection of historical data, field research, analysis and verification of each layer and its influence factors, which leads to a huge workload. The difficulty in the collection of basic data is magnified by the following factors: The scarcity of local historical data in Myanmar of existing research, long time span, large spatial span and a large number of Buddhist architectural sites. It is hoped that a more comprehensive, profound and detailed research system can be constructed in both a bottom-up and a top-down manner in the future.

Second, the space and time in the research can be expanded. This paper focused on the ancient period before the 13th century. The timeline can be elongated in the future to conduct a more comprehensive analysis of the development trend, styles and characteristics of the Buddhist architecture in Myanmar.

Third, the research orientation can be extended. This study is mainly focused on the development history and characteristic evolution of the Buddhist architecture. It is the foundation of the research on architectural heritage conservation, urban heritage conservation, sustainable development and other issues related to local architecture, and provides sufficient historical analysis, methods and grounds for further research in this area. In the future, the research orientation can be extended to the spatial morphological evolution of the ancient city cluster of the Ayeyarwady Basin in the historical environment to analyze the influence of water culture and basin culture on urban construction.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Wei Dong’s studio and Professor Su Su for supporting the case study.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the text. Yicun Pang conceived and wrote the paper. Wei Dong and members of Wei Dong’s studio drew relevant pictures and proposed an innovative plan.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cady, J. 1958. A History of Modern Burma. New York, USA: Cornell University.

- Cooler, R. M. 2003. The Art and Culture of Burma. DeKalb, USA: Northern Illinois University.

- Dong, W. 2015. “An Initial Study on Urban History in Southeast Asia A Cultural Perspective from Southwest China.” . Architectural Journal 62: 18–23.

- Elizabeth, H. M. 2007. Early Landscapes of Myanmar. Bangkok, Thailand: River Books.

- Elizabeth, H. M. 2010. “Myanmar Bronzes and the Dian Cultures of Yunnan.” Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association, no. 7: 122–132.

- Frederic, L. 1965. The Temples and Sculptures of Southeast Asia. London, UK: Thames and Hudson.

- He, S. D. 2015. History of Myanmar. Kunming, China: Yunnan People’s Publishing House.

- Hudson, B. 2019. “Five Dynasties at Sriksetra?” Sri Ksetra or An Introduction of Pyu Kingdom. 331–337.

- Hudson, B., and T. Lustig. 2008. “Communities of the Past: A New View of the Old Walls and Hydraulic System at Sriksetra, Myanmar (Burma).” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 39: 269–296. doi:10.1017/S0022463408000210.

- Lall, V. 2014. The Golden Lands: Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand & Vietnam. New York, USA: Abbeville Press.

- Lat, K. 2010. Art and Architecture of Bagan and Historical Background with Data of Important Monuments. Yangon, Myanmar: Daw Nandi Lin(Mudon Sarpay).

- Luce, G. H. 1969. “Old Burma-Early Pagan.” New York, USA: Artibus Asiae.

- Ma, D. L. 2011. Literature Research. Beijing, China: Zhonghua Book Company.

- Michael, A. T., and A. T. Matrii. 2012. A History of Myanmar since Ancient Times: Traditions and Transformations. London, UK: Reaktion Books.

- Ministry of Culture. 2014. World Heritage Pyu Ancient Cities: Halin, Beikthano, Sri Ksetra. Yangon, Myanmar: Department of Archaeology and National Museum.

- Myint, A. 1970. “The Excavation of Halin.” Journal of Myanmar Society, no. 7.

- Ou, Y. X., and Q. Song. 1975. The New Book of Tang. Beijing, China: Zhonghua Book Company.

- Pichard, P. 1992. Inventory of Monuments at Pagan. Arran, Scotland: Kiscadale Publications.

- Richard, M. C. 2003. The Art and Culture of Burma. DeKalb, US: Center for Southeast Asian Studies, northern illinois university.

- Royal Historical Commission. 2010. Hmannan Maha Yazawin Daw Gyi; Li, M., Yao, B.Y. Beijing, China: Commercial Press.

- Stadtner, D. M. 2011. Sacred Sites of Burma: Myths and Folklore in an Evolving Spiritual Realm. Sandy Lane, UK: Antique Collectors Club.

- Stargardt, J. 1991. The Ancient Pyu of Burma Vo1.I. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Stargardt, J. 2016. “From the Iron Age to Early Cities at Sri Ksetra and Beikthano, Myanmar.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 47 (3): 341–365. doi:10.1017/S0022463416000230.

- Stargardt, J. 2020. “Sri Ksetra, 3rd Century BCE to 6th Century CE: Indianization, Synergies, Creation.” Primary Sources and Asian Pasts 11: 220–265.

- Strachan, P. 1990. Imperial Pagan. Honolulu, USA: University of Hawaii Press.

- Thaw, A. “Report on the Excavation at Beikthano.” Ministry of Union Culture: Yangon, Myanmar, 1968.

- Thaw, U. A. 1972. Historical Sites in Burma. Yangon, Myanmar: Ministry of Union Culture.

- Williams, J. G. 2010. The Stupa: Buddhism in Symbolic Form. Clinton, USA: Gwenfrewi Santes Press.