ABSTRACT

The subject of specialized history is a concept introduced from the West to China. During the first half of the twentieth century, Chinese historians consciously attempted a paradigm shift in historiography. The emergence of specialized histories means that the writing of histories is no longer decided by traditional historians but planned by scholars in their fields. In this context, the history of architecture quickly arose, as well as the history of gardens. This article focuses on the development of Chinese garden history in the past century. Reviewing the establishment, advancement, and increasingly interdisciplinary and intercultural direction of Chinese garden history, this paper attempts to explore the future of the discipline and its more diverse possibilities.

1. Introduction

When the study of Chinese gardens became an independent subject, there would inevitably be conflicts between tradition and modernity. The method of emphasizing site surveys and mapping has provided significant help in recording the classical gardens in China. However, many scholars have also noticed the incompleteness of Westernization in the research of Chinese gardens. At the end of the twentieth century, some of them discussed the contradiction between tradition and Westernization in Chinese gardens. For instance, Stanislaus Fung offered a simple sketch of three waves of scholarship, which can be considered “bursts of scholarly activity from the 1930s to the end of the 20th century” in “Longing and Belonging in Chinese Garden History”. It explained how Western techniques such as orthogonal drawing, spatial analysis and photography affected the modern understanding of Chinese gardens. (Fung Citation1999) Looking back at the development of Chinese garden history in the past century, the paradigm shift from traditional historiography to “New Historiography”Footnote1 that began in the early twentieth century was the key to creating a modern “Chinese garden history”.

Firstly, influenced by the idea of nationalism, Chinese reformers realized that Confucianism was not “absolute” any longer, changed dynastic history into national history, and transformed historical writing both in idea and form. (Wang Citation2001) This trend has also prompted Chinese scholars to reflect on the language, methods, thinking and historical materials of traditional Chinese historiography. As a result, in the 1930s, emerging scholars emerged at Peking University who explicitly supported following Western Sinology, like what Paul Pellio and Bernhard Karlgre did (Zhou and Chen Citation2012).

Then, these paradigm shifts also contributed to establishing specialized history. Specialized history should be the responsibility of professional scholars in the corresponding discipline instead of general historians (Liang Citation2013). It directly led to the participation of architects and landscape architects in the writing of garden history, which profoundly impacted the establishment of this discipline. Lai Delin (赖德霖) commented that many disciplinary histories, such as the history of literature, the history of philosophy, and the history of architecture that emerged in China since the beginning of the twentieth century, were all products of the specialized history (Lai Citation2014).

Finally, a specialized history had a substantial development in the history of Chinese architecture due to the establishment of the Chinese Architectural Society (Zhongguo yingzao xueshe 中國營造學社). They noticed the History of Chinese gardens and finally formed the modern historiography of Chinese gardens. Since then, the study of Chinese gardens has developed in two directions: site surveys and linear chronicles, and gradually approached the cross-cultural and interdisciplinary field.

This paper attempts to review the process of historical discourse’s formation in the Chinese garden, in addition to rethinking the possibilities of this discipline. In this paper, the research method is mainly a literature review, especially the historiography global comparative study and Chinese gardens. On the one hand, this paper compares the different historiographic attitudes of China and the West since the 1900s; the literature in this section focuses on the work of cross-cultural historians such as Edward Wang. On the other hand, it focuses on the establishment and development of specialized historiography in the field of Chinese architecture and gardens since the 1930s, such as Tong Jun’s (童寯1900-1983) Jiangnan yuanlin Zhi (江南园林志), Liu Dunzhen’s (刘敦桢 1897–1968) Suzhou gudian yuanlin (苏州古典园林) and Chen Congzhou’s (陈从周1918-2000) Suzhou yuanlin (苏州园林).

2. The paradigm shift of historiography in China

Chinese garden history has been a well-established field of academic study for almost a hundred years. Alison Hardie pointed out that the subject of garden history was a concept introduced from the West to China when Chinese people started the May Fourth Movement in 1919 Hardie (Citation2003). During the first half of the twentieth century, some significant changes occurred at ideological and methodological levels in historiography. The ideological dimension refers to their sensitivity to nationalist concerns, while the methodological one aims to use scientific methods for historical research.Footnote2 In the methodological standard, Chinese intellectuals started to search for a new understanding of tradition. They broke away from the traditional Chinese historical norms of political or military history, pursuing the writing of scientific history.Footnote3

From the 1920s to the 1930s, leading historians in China put forward new reflections on historical evidence, including Hu Shi (胡适1981-1962), Fu Sinian (傅斯年1896-1950), and Gu Jiegang (顾颉刚1893-1980). It’s not difficult to find out that they all significantly changed epistemology. First, for that generation, the authority of the traditional Confucian ideology had collapsed. In their eyes, Confucian classics are just a kind of historical evidence instead of supreme ultimate truth. In addition, on this basis, they are also advocating a view of the development of history; the value of historical evidence in each era should be treated equally (Wang and Wang Citation2012). This new value of historical evidence was called by the famous Chinese educator Cai Yuanpei (蔡元培1868-1940) “the equal view”. The role of “the equal view” is multifaceted; on the one hand, it changed the leading position of Confucian classics. On the other hand, it extended the scope of historical evidence, not just texts. In addition, the “double evidence method” (二重证据法) proposed by Wang Guowei (王国维1877-1927) also emphasizes combining the evidence on paper and evidence in the site, which provided a new research idea for research methodology in the history of architecture and garden.

Moreover, the paradigm shift in Chinese historiography changed traditional historical writing to new history, bringing historians’ perspectives to various human activities. Liang Qichao’s (梁启超1873-1929) viewpoint of “specialized history” was the early ideology that guided the development of disciplinary history, making the specific disciplines could be in charge of the relevant scholars instead of historians.

“The history we need today should be divided into specialized and general history. Specialized history is supposed to be the history of law, the history of literature, the history of philosophy, and the history of art. In contrast, general history is the history of an inclusive culture. The historians who work on specialized history must be able to master the accomplishment of history and the attainment of specific subjects. This kind of history should be regarded as the responsibility of scholars in various disciplines rather than historians.”

(今日所需之史, 当分为专门史与普通史之两途。专门史如法制史, 文学史, 哲学史, 美术史等等; 普遍史即一般之文化史也。治专门史者, 不惟须有史学素养。此种事业, 与其责望诸史学家, 毋宁责望诸各该专门学者。) Footnote4

As Liang Qichao said, the history of architecture should be developed by the architects, not just the historians. A few decades later, Liang Qichao’s Son Liang Sicheng (梁思成1901-1972), a member of the Chinese Architectural Society, contributed to the history of architecture.

3. Chinese architectural society and garden history

In the 1920s, a group of overseas students returned to China, many of whom were engaged in architecture, including Liang Sicheng, Tong Jun, Liu Dunzhen, and some other Chinese architects who studied abroad (Ming and Yang Citation1998). In 1930, Zhu Qiqian, a politician of the new Chinese government, established a non-governmental academic organization named the Chinese Architectural Society. Many of these young architects became members of the organization (Zhu Citation1999).

Zhu Qiqian (朱启鈐1871-1964) explained the establishment of the new organization and expressed his expectation for the future of architecture in the article “Zhongguo yingzao xueshe yuanqi” (The origin of Chinese Architectural Society中国营造学社缘起)

“Li Mingzhong is a magnanimous and elegant man with talent, now taking the position of the Great Artisan (Jiang Zuo). Then, he worked with the craftsman and studied structures in detail, called paradigm (Fashi). It Changed the situation that principle (Dao) and implement (Qi) were separated, breaking the old habit value scholar-official and despise of the worker. Nowadays, we should thoroughly research how to read and use Li’s book. Make sure that people who study it would achieve mastery through a comprehensive study of the book. Afterwards, we must collect images and turn them into practical engineering books.

The terminology used in architecture, some objects have several names at the same time, and some objects’ names change at any time. Therefore, we should arrange and compare them and attach pictures to explain. Editing them into an architectural lexicon is not only suitable for guidance and explanation but also not contrary to etiquette. The palaces and rooms of the ancients found in traditional Confucian classics should be taken for evidence.

Moreover, the objects themselves should be emphasized. Everything in architecture should be collected as data, such as a brick, a pillar, even a tomb, and the writing left behind, the ruins of temples, especially those preserved and recorded by archaeologists, artists, and collectors. The best traditional Chinese boundary painting (Jiehua) and powder sketch(Fenben) by the ancients painted the building realistically. Besides, these buildings’ patterns, models, and photos are in modern times. We should try to find all the above evidence.”

(李明仲以淹雅之材, 身任将作, 乃与造作工匠, 详悉讲究, 勒为法式。一洗道器分涂, 重士轻工锢习。今宜将李书读法用法, 先事研穷。务使学者, 融会贯通, 再博采图籍, 编成工科实用之书。

营造所用名词术语, 或一物数名, 或名随时异。亟应逐一整比, 附以图释, 纂成营造词汇。既宜导源训诂, 又期不悖于礼制。古人宫室制度之见于经史百家者, 皆宜取证, 并应注重实物。凡建筑所用, 一甓一椽, 乃至冢墓遗文, 伽蓝旧迹, 经考古家, 美术家, 收藏家, 所保存所记录者, 尤当征作资料。 希其援助。至古人界画粉本——实写真形, 近代图样模型影片, 皆拟设法访求。) (Zhu Citation1930).

From the texts above, we can find out the aim of establishing the Chinese Architectural Society is to set up the subject of architecture in China with scientific methods and systematic research. There are several basic methods for the establishment of architecture. First, to change the traditional habit, combine and implement the principles. Following the conventional theory, but also pay attention to the practical operation of craftsmen. Second, to unify professional terms, connect pictures with words, and complete the accurate collation of architectural vocabulary systematically. Third, to update the scope of historical evidence, combining the written records of architecture with the architecture itself. We should not only do the site survey of constructions that appeared in the classics but also collect the architectural documents, such as traditional Chinese realistic paintings and other records. Last, to use new techniques in modern times, like hand drawings, models, films, and photographs.

These new ideas were applied to the history of Chinese architecture, whether the challenges to old ideologies or the innovations to historical evidence. The Institute aimed to use scientific methods and systematic research to establish the field of Chinese architecture. In their publications, they paid attention to the physical environment of the buildings. Then was usually supported by publishing site survey reports of ancient buildings.

The works at that time were made by scholars like Liang Sicheng, under the context that many Chinese cultural relics were lost, and ancient buildings were severely damaged. This academic theses cover site surveys, textual criticism, and Western architectural drawing techniques. It continues to affect the discourse on the history of Chinese architecture. (Liang) Xia Zhujiu (夏铸九) thought Liang’s reports belonged to a typical academic thesis of the architecture school, with a similar writing structure. Xia regarded these papers as “national architectural discourse”, which has also significantly caused disputes between tradition and modernity in this field (Xia Citation1995).

This method was also brought into the research on the history of Chinese gardens by Liu Dunzhen and Tong Jun, who were also members of “The Institute for Research in Chinese Architecture”. In the first year of the Chinese Architectural Society, they started researching a significant book about Chinese gardens in the Ming dynasty, Yuan ye (园冶). Then, Liu Dunzhen and some other members of the Chinese Architectural Society began to transform their attention from traditional buildings to classical gardens in China.

4. The historical research of Chinese gardens

The key emphasis in the Chinese Architectural discipline was not the traditional Chinese garden. As a result, during wartime in the early twentieth- century, Tong Jun was the first Chinese scholar who did site surveys in Jiangnan gardens. His work Jiangnan yuanlin Zhi (江南园林志) was the only specialized work about the classical gardens in south China at that time. Nowadays, it is generally believed that Tong was the first scholar who started research on traditional Chinese gardens in modern times (Lai Citation2012).

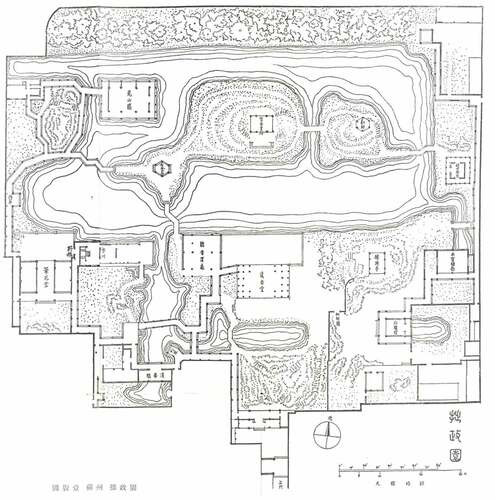

When Tong Jun made his field trip to the Jiangnan gardens in the 1930s, he took many photos and did some measuring work for these gardens (like ). However, Tong also noticed the difficulties and limitations of the methods of drawing plans for the gardens. The indeterminacy of the elements in a garden, including the plants, the rockeries, and the paths, is challenging to paint accurately. The wonders of these gardens are hard to describe unless in the gardens themselves.Footnote5 Tong mentioned the progress of field investigation and his attitude towards garden research in Jiangnan yuanlin Zhi.

“The author (I) drew the maps and took photographs of the splendid gardens I travelled through. The plans I painted were not precisely measured but a rough size. Mainly, the layout of the gardens was not rigidly standardized but lively and flexible, which was not necessary to measure with norms criteria.”

(著者旅行所经, 偶有佳构, 辄製图摄影。惟所绘平面图, 并非准确测量, 不过约略尺寸。盖园林排挡, 不拘泥于法式, 而富有生机与弹性, 非必衡以绳墨也。) (Tong Citation1963).Footnote6

Figure 1. The master plan of the garden of the unsuccessful politician in Jiangnan yuanlin zhi.Footnote6

Tong Jun also illustrated his points of view on the relationship between texts and images in the history of the Chinese gardens. He said that most of the researchers in the aspect of Chinese gardens, emphasize the writing record more than the images, except for some books such as Zhao Zhibi’s (赵之壁ca. 1771) Pingshan tang tu Zhi (平山堂图志) and Li Dou’s (李斗ca. 1817) Yangzhou huafang lu (扬州画舫录). Therefore, Tong started his site surveys of the classical gardens in the Jiangnan area during wartime. This method dominated the mainstream in Chinese garden research, while chronological works appeared until the 1980s.

5. Site survey and analysis

According to the contents of Tong Jun’s Jiangnan yuanlin Zhi, we could find out that the new research methods such as site surveys, mapping and photographing were the tendency in the subject of Chinese gardens in the twentieth century, although there were many opposites with the traditional methods. The choice between conventional and new research methodology has always been controversial among Chinese scholars since the intervention of western ideas. After Tong Jun, the related scholars carried out their works in the classical Chinese gardens; two were the representative personages in this field. Liu Dunzhen’s Suzhou gudian yuanlin (苏州古典园林) and Chen Congzhou’s Suzhou yuanlin (苏州园林), respectively, reflect the different emphasis of the two authors on the methodology of garden research.

Liu Dunzhen was a professional architect who once studied in Japan. He did not limit himself to the aspect of traditional Chinese architecture but turned his attention to classical Chinese gardens, which were not a concern to many scholars at that time. According to the recollections of Liu Dunzhen’s son, he began working in private gardens in Suzhou in 1954. First of all, the data on the natural environment, history, economy, culture, and the current situation of the gardens are collected as extensively and detailedly as possible. Meanwhile, the location, name, size, preservation, and history of all kinds of gardens in Suzhou were counted comprehensively. Then select the gardens for other writing records, photography, and mapping (Liu Citation2008).

Liu Dunzhen pursued accuracy in mapping. As long as it was in the garden, no matter the layout, or the buildings, rocks and rockeries, water, plants, and some other elements in the gardens, Liu and his staff tried their best to be detailed. For example, when drawing the master plans of each garden, even a tree or a rock, it was requested to be accurate about the location and name. Also, for the sections and elevations, everything they drew must be consistent with reality, including the height and crown width of all trees, the general pattern of branches and leaves, and the shape and character of the rocks. Once one mistake appeared, all of these paintings must be redrawn.Footnote7 ()

Figure 2. The master plan of the Garden of the Unsuccessful Politician in Suzhou gudian yuanlin (Liu Citation1979).

Figure 3. The elevations of the Garden of the Unsuccessful Politician in Suzhou gudian yuanlin.Footnote8

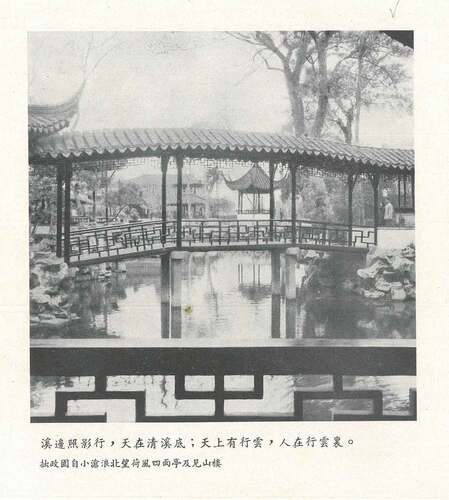

In contrast, Chen Congzhou played the role of an architect and a literator. His works were in line with Chinese literature and arts, with his comprehensive achievements in the appreciation of poetry, calligraphy, painting, and opera. His garden aesthetics thoughts can transcend the professional barriers of architecture and have more considerable cultural significance, which has been widely valued. For example, although there are some master plans and detailed constructions of the Garden of the Unsuccessful Politician (拙政园) in Suzhou yuanlin, the core of this book is its similar mode of traditional literature (Chen, Citation1956). The text is a small part of the book, and the significant part is that the photos of gardens juxtapose the Song verse. The juxtaposition between an image and text has something in common with the traditional literati’s album painting and poetry, allowing readers to have poetic associations. () This way of combining traditional literature with new technologies introduced from the West is something architects who had studied overseas during the same period did not notice.

Figure 4. The juxtaposition between photos and Song verse in the Garden of the Unsuccessful Politician in Suzhou Yuanlin.Footnote9

To sum up, the methods of the historical research of Chinese gardens since the 1930s followed the methodological reforms proposed by the Chinese Architectural Society. The scholars in architectural academia created a systemic discipline by combining the principle and implementation, updating the scope of historical evidence like site surveys and using new techniques in modern times such as photography. These scholars’ emphasis might differ; for instance, Liu Dunzhen cared a lot about the accurate measurement of the gardens; Tong Jun paid more attention to the analysis of texts; and Chen Congzhou focused on traditional Chinese artistic conception.

6. Linear chronicles

According to “Longing and Belonging in Chinese Garden History” by Stanislaus Fung, there were three academic waves in the history of the Chinese garden in the 20th century. In the 1930s, the first wave was led by Japanese scholars, such as Shina tei’en ron (On the gardens of China) by Oka Oji. It was not until the 1980s that Chinese scholars’ chronicle of Chinese classical gardens matchedFootnote8 the early Japanese works of the 1930s in scope and detail.Footnote9Footnote10 For instance, Zhang Jiaji’s (张家骥1932-2013) History of Chinese gardening (Zhongguo zaoyuan shi 中国造园史), Zhou Weiquan’s (周维权1927-2007) History of classical Chinese gardens (Zhongguo gudian yuanlin shi中国古典园林史), and Wang Yi’s (王毅) Gardens and Chinese culture (Zhongguo yuanlin wenhua中国园林文化) were the representatives of chronological Chinese garden history.

Compared with the books that I mentioned in the previous section, “site survey and analysis”, Zhou and Wang focused more on the origin of gardens and the rise and fall of gardens over thousands of years. They chose dynasties as some chapters to divide gardens into different periods. In historical evidence, Zhou Weiquan and Wang Yi relied upon the Chinese classics in gardening, literature, arts and many other fields.Footnote11 They found not only the relevant textual records but also landscape paintings about the gardens from the historical materials to support the research of the gardens, which have been damaged or disappeared.Footnote12

Zhou divided Chinese garden history into four periods according to the artistry of garden-making; respectively the Generating Period from Xian Qin (先秦)to Han (汉)(B.C 11th century – A.D 220); the Transition Period from the Wei (魏)to the North and South Dynasties (南北朝) (A.D 220–589); the Thrived Period from the Sui (隋) to the Tang Dynasty (唐朝) (A.D 589–960); the Pre-maturation Period from the Song (宋) to the early Qing Dynasty (清朝) (A.D 960–1736); and the Late-maturation Period from the mid-Qing to the late-Qing Dynasty (A.D 1736–1911) (Zhou Citation1990).

On the other hand, Wang Yi divided the Chinese gardens into different periods under the standard of traditional Chinese ideology. For example, Wang believed that the gardens from mid-Tang Dynasty to the Song Dynasty (A.D 960–1279) followed the conception of “Heaven and earth in a pot” (壶中天地)Footnote13; then it turned into the concept “Mt. Sumeru in a Mustard Seed” (芥子纳须弥)Footnote14 from the Ming Dynasty (明朝) to the Qing Dynasty (A.D 1368–1911) (Wang Citation1990).

To some extent, such studies on the history of Chinese classical gardens are closely related to China’s political changes, economic development, and philosophical thoughts over thousands of years. However, different from any traditional Chinese Chronicles, the main content of these books is classical gardens rather than any historical figures and events. Garden historians like Zhou Weiquan and Wang Yi still closely follow traditional Chinese culture and history in their compilations. However, these garden chronicles were influenced by the “New Historiography” paradigm in writing mode. They began to focus on general descriptions rather than the poetic record of gardens in traditional Chinese literature.

7. Interdisciplinary and cross-cultural development of Chinese gardens

Since the late 20th century, the study of Chinese garden history has become more diversified. Since then, scholarly communications on Chinese gardens between China and the West have become more frequent. The interdisciplinary and cross-cultural research of the Classical Chinese gardens has become an inevitable tendency in this field.

Some Western scholars tried to explore Chinese gardens in art, sociology, religion, and economics. For instance, Joanna F. Hanlin Smith’s “Gardens in Ch’i Piao-chia’s Social World: Wealth and Values in Late-Ming Kiangnan” analyzed the individuality of the garden’s owner and the sociality of the late Ming (Handlin Smith Citation1992). The study of the Ming dynasty’s gardens in the late twentieth century has received considerable attention in the West. Craig Clunas published two significant works on Chinese gardens. The first is Superfluous Things: Material Culture and Social Status in Early Modern China (Clunas Citation1991). Then the other one, named Fruitful Sites: Garden Culture in Ming Dynasty China, analyzed the Chinese gardens from the aspect of economics (Clunas Citation1996).

On the other hand, many Chinese scholars have made some breakthroughs in the disciplinary study of Chinese gardens to get out of the limitation of architecture. For example, Hou Naihui (侯迺慧) published a book named Tangsong shiqi de gongyuan wenhua (唐宋时期的公园文化) (Hou Citation2010). in 1997, which discussed the publicity of gardens in the Tang and Song dynasty. This book’s in-depth study of the social culture of the tang and song dynasties shows the close connection between the history of Chinese gardens and social science. It is a research that has little to do with the architectural perspective. Later, Cao Lindi’s (曹林娣) Suzhou yuanlin bian’e yinglian jianshang (苏州园林匾额楹联鉴赏) (Cao Citation2011). is one of the works that try to understand Classical Chinese gardens differently. This book aims to analyze the inscribed boards and couplets in some classical gardens in Suzhou in the aspect of literature. Boards, couplets, and even brick carvings all represent the detailed description and wish of the garden by the owner or the literati who took part in the construction of this garden. Such an analytical method helps us have a better understanding of the artistic conception of a garden.

8. Conclusion

In sum, from the beginning of the twentieth century, the research on Chinese gardens has experienced more affluent development than in the past several thousand years. Suppose we put the history of the discipline of Chinese gardens into the context of the more macroscopic paradigm shift of Chinese historiography. In that case, we will find that China was forced to engage in various exchanges with other countries, which brought earth-shaking changes to its traditional culture in the early twentieth century. It has accepted the concept of “scientific history” introduced by the West. As a result, the content of historiography was related to every aspect of people’s lives, thus forming various independent disciplinary histories. Also, the historical evidence was broken out from the traditional Confucian classics and then extended over the scope of texts and images.

These two results are parts of the reasons that directly influence the emergence of Chinese garden history and its research methods. Scholars engaged in garden chronicles not only focused on traditional archaeological ways, collecting various historical records and pictures but also gave special attention to the relationship between the actual objects and the documents. The scholars who worked on the analysis of sites paid more attention to the scientific research methods and brought various modern research methods such as master plans, sections, axonometric drawings, and photographs. At this stage, there has been a fundamental innovation in the research of Chinese classical gardens.

Moreover, more scholars from different disciplines showed their interest in studying Chinese gardens, which proved that this subject still has considerable room for development in the cross-cultural and interdisciplinary aspects. By looking back on the result of the past hundred years, the hidden creativity in Chinese gardens, through some logical extension of different disciplines or technologies such as media, can have more possibilities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yan Liu

Yan Liu is a PhD candidate at the School of Architecture, The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her research focuses on the history and theory of classical Chinese gardens in in-tercultural and interdisciplinary contexts, especially the spatial experience and cultural memory in relation to phenomenology. The critical point of her dissertation is about the history and memory of the private gardens in the late Ming Dynasty.

Notes

1 Pei Yu 于沛, “Biandong zhong de xifang shixue” (变动中的西方史学). Dangdai Zhongguoshi Yanjiu 06 (2003), 62. According to Yu, In the development of Western historiography, the 19th century is called the “century of history”. In the 20th century, Western historiography gained new achievements under the banner of “New historiography”.

2 Wang, Inventing China Through History: The May Fourth Approach to Historiography, 04.

3 Ibid, 42.

4 The texts was translated by myself. See in Liang, Liang Qichao Zhongguo lishi yanjiufa; Liang Qichao Zhongguo, 39-40.

5 Ibids, 03-04.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid., 43.

8 Ibid., 314.

9 Ibid., 38.

10 Fung, “Longing and Belonging in Chinese Garden History”, 205-207.

11 Zhou, Zhongguo Gudian Yuanlinshi, 20.

12 Wang, Yuanlin yu Zhongguo wenhua, 717.

13 “Heaven and earth in a pot” (壶中天地) is a Daoist legend in Hou Hanshu (后汉书). A famous Daoist in Han Dynasty named Fei Zhangfang (费长房) met an old medicine seller. The old man who sold medicine jumped into the pot at the end of the market, Fei Changfang followed it, and obtained the technique of shrinking the ground. The reason why Wang Yi believes that gardens from the late Tang to the Song dynasty followed this rule is because the official-scholars have become obsessed with creating unique interests and techniques in small spaces since the Middle Tang dynasty. Until the end of the Song Dynasty, this custom continued. This changed very quickly with the garden of the large space before the mid-Tang Dynasty.

14 “Mt. Sumeru in a Mustard Seed” (芥子纳须弥) is a Buddhist tale. Mustard is a vegetable, and the seeds are like millet grains, and the Buddhist metaphor of “mustard seeds” is extremely small. Mount Meru was originally the name of a mountain in Indian mythology, and later used by Buddhism to refer to the residence of Emperor Shaktian and the Four Heavenly Kings, and the Buddhist family uses the metaphor of “Mount Meru” to be extremely large. Wang Yi believes that in the Ming and Qing dynasties, the literati’s pursuit of gardening was not only to carve in a relatively small space, but also to establish a cosmic system of “the unity of heaven and man”, so that the highly developed traditional cultural system could be hidden in it.

References

- Cao, L. 曹林娣. 2011. Suzhou Yuanlin Bian’e Yinglian Jianshang (苏州园林匾额楹联鉴赏). Beijing: Huaxia chubanshe.

- Chen, C. 1956. 陈从周. Suzhou yuanlin (苏州园林). 1–12. Shanghai: Tongji daxue chubanshe.

- Clunas, C. 1991. Superfluous Things: Material Culture and Social Status in Early Modern China. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Clunas, C. 1996. Fruitful Sites: Garden Culture in Ming Dynasty China. London: Reaktion Books.

- Fung, S. 1999. “Longing and Belonging in Chinese Garden History.” In Perspectives on Garden Histories, edited by M. Conan, 205–219. Washington, D.C: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

- Handlin Smith, J. F. 1992. “Gardens in Ch’ I Piao-Chia’s Social World : Wealth and Values in Late-Ming Kiangnan.” The Journal of Asian Studies 51 (1): 55–81. doi:10.2307/2058347.

- Hardie, A. 2003. “Introduction.” In The Chinese Garden: History, Art and Architecture, edited by M. Keswick, 9. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Hou, N. 侯迺慧. 2010. Songdai yualin jiqi shenghuo wenhua (宋代園林及其生活文化). Taipei: Sanmin shuju gufen youxian gongsi.

- Lai, D., 赖德霖. 2012. “Tongjun Sw Zhiye Renzhi, Ziwo Rentong He Xiandaixing Zhuiqiu (童寯的职业认知, 自我认同和现代性追求).” Jianzhushi 155 (1): 34.

- Lai, D.; 赖德霖. 2014. “Jingxue, Jingshizhixue, Xinshixue Yu Yingzaoxue He Jianzhushixue (经学, 经世之学, 新史学与营造学和建筑史学–现代中国建筑史学的形成再思).” Jianzhu Xuebao 9: 108–116.

- Liang, Q. 2013. 梁启超. Liang Qichao Zhongguo Lishi Yanjiufa; Liang Qichao Zhongguo Lishiyanjiufa Bubian (梁启超中国历史研究法 ; 梁启超中国历史研究法补编). 41. Changchun: Jilin renmin chubanshe.

- Liu, D.刘敦桢. 1979. Suzhou ghudian yuanlin (苏州古典园林) 1st. 313. Beijing: Zhongguo jianzhu gongye chubanshe.

- Liu, X., 刘叙杰. 2008. “Ji Fuqin Liu Dunzhen Dui Zhongguo Chuantong Gudian Yuanlin de Yanjiu He Shijian (纪父亲刘敦桢对中国传统古典园林的研究和实践).” Zhongguo Yuanlin 24 (8): 42–43.

- Ming, L., and Y. Yang杨永生, . 1998. Jianzhu sijie: Liu Dunzhen, Tong Jun, Liang Sicheng, Yang Tingbao(建筑四杰: 刘敦桢, 童寯, 梁思成, 杨廷宝). 7–31. Beijing: Zhongguo jianzhu gongye chubanshe.

- Tong, J. 1963. 童㝦. Jiangnan Yuanlin Zhi (江南园林志). 3. Beijing: Zhongguo gongye chubanshe.

- Wang, Y. 1990. 王毅. Yuanlin yu Zhongguo wenhua (园林与中国文化). 2. Shanghai: Shanghai renmin chubanshe.

- Wang, Q. E. 2001. Inventing China through History: The May Fourth Approach to Historiography, ed. D. L. Hall and R. T. Ames., 3–17. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Wang, F., and X. Wang王晓冰, . 2012. Fu Sinian: Zhongguo jindai lishi yu zhengzhi de geti shengming (傅斯年: 中国近代历史与政治中的个体生命). 331. Beijing: Xinzhi sanlian shudian.

- Xia, Z., 夏铸九. 1995. ““Yingzao xueshe, Liang Sicheng jianzhushi lunshu zhi lilun fenxi “ (營造學社——梁思成建築史論述之理論分析).” In Kongjian, lishi yu shehui: Lunwen xuan: 1987-1992 (空間, 歷史與社會 : 論文選1987-1992), 7. Taipei: Taiwan shehui yanjiu congkan.

- Zhou, W. 1990. 周维权. Zhongguo Gudian Yuanlinshi (中国古典园林史). 1–7. Beijing: Qinghua daxue chubanshe.

- Zhou, X., and Z. Chen, 陈喆华. 2012. “Shixue liubian xia de Zhongguo yuanlin shi yanjiu” (史学流变下的中国园林史研究).” Chengshi Guihua Xuekan 4: 114.

- Zhu, Q., 朱启鈐. 1930. “Zhongguo yingzao xueshe yuanqi (中國營造學社緣起).” Zhongguo yingzao xueshe huikan (中國營造學社匯刊) 1 (1): 1.

- Zhu, H., 朱海北. 1999. “Zhongguo Yingzao Xueshe Jianshi (中国营造学社简史).”.” Gujian Yuanlin Jishu 65 (4): 13.