ABSTRACT

This paper examines the architectural significance of the first architectural drawings on Korean housing conditions produced between 1904 and 1932. Based on the political context of the time and place under investigation, most of the drawings produced at the time reflect Japan’s orientalist perspectives on its Asian neighbours. Nevertheless, due to the close socio-cultural relationships that existed between Japan and Korea in the early 1900s, shared contemporary architectural knowledge, such as positivism and human geography, played an important role in the creation of Korean architectural drawings. In this context, by closely communicating with the Japanese active in the Korean peninsula, Kil-Ryong Park developed his unique architectural approaches to analyse and create Korean housing conditions by producing poetic perspectival drawings without real-life qualities and devising architectural borders and thresholds, while meticulously examining the sites’ microscopic physical and environmental conditions. This research employs the hermeneutic research approach to address the gaps within existing scholarship which has so far focused only on the scientific and utilitarian characteristics of Park’s architectural work.

1. Introduction

This study examines the architectural drawings of three historically important architects who worked on visualising Korean building traditions in the early 1900s. Further, it sheds light on the manner in which the first modern Korean architect formulated his architectural ideas by both embracing and developing contemporary Japanese architectural knowledge that was circulated in the Korean peninsula. At the time, architecture was a new discipline in the modern Korean context. Hence, early architectural drawings were primarily made by Japanese architectural historians, such as Tadashi Sekino (1868–1935), who first came to Korean peninsula to investigate vernacular building traditions as part of Japanese colonial projects in 1904.Footnote1 Heavily influenced by the positivistic research trend popular in Japan, his drawings were not so much architectural in terms of visualizing the invisibleFootnote2 as being analytical and scientific where the subject simply described the physicality of architectural objects freed from their surrounding environments.

In the early 1920s, a new set of architectural drawings was introduced into the Korean colonial context. They were actualised by the efforts of Japanese folklorist Wajiro Kon (1888–1973), who had come to the Korean peninsula to investigate Korean vernacular housing, minka. Kon’s meticulously created hand drawings reflected the Japanese tradition of human geography of the time and depicted Korean people’s lifestyles in various architectural settings in detail. In many cases, the drawings even included everyday items, such as clothing, tools, and furniture. To create vivid atmospheres, Kon immersed himself in the people’s living scenes observed by him, due to which his drawings create architectural qualities that enable viewers to reproduce the same scenes before their eyes.Footnote3 A series of annotated texts placed next to the drawings played an important role in helping their poetic imaginations, as well.Footnote4

While doing his architectural apprenticeship under the Japanese in the early 1920s, Kil-Ryong Park, the first modern Korean architect, conducted field research on Korean minka with Yoshiyuki Iwatsuki, a Japanese architectural engineer, in 1923. As part of this research, Park made a series of architectural drawings depicting how Iwatsuki’s architectural ideas regarding the characteristics of Korean vernacular housing from various regions, which were based on the Japanese engineer’s observation of Korean people’s lives, influenced Park’s unique perspectives of Korean minka.Footnote5 In the early 1930s, as soon as he opened his own architectural practice, which was the first Korean architectural office, Park started popularising his own architectural ideas on reforming traditional Korean housing conditions and visualising them in newspapers and journals through carefully produced architectural drawings and texts.

Most of the architectural drawings produced by Park during his practice have not been passed down to the present time. Hence the aforementioned drawings and texts are the only sources to unveil the architectural ideas and intentions of the first modern Korean architect, which seem to have an important bearing on the contemporary architectural knowledge circulated in the Korean peninsula. Moreover, current research approaches on Park and his architectural significance, which focus only on the scientific and hygienic aspects of his contributions, have several shortcomings in that they formulate misconceptions regarding modern Korean architecture as being limited to efficient buildings alone.Footnote6 This biased conception causes one to understand architectural ideas from an engineering-oriented perspective alone, which undermines the possibility of these ideas becoming communicative settings in the modern Korean context.Footnote7

In this context, Park’s architectural legacy is important because his architectural drawings and texts reflect ideas that are not visible and, by using them appropriately, he developed his architectural creations by not only specifying utilitarian ideas for building but also considering borders, thresholds, demarcations, and orientations in designing interior and exterior conditions, which ultimately enabled the creation of modern scientific architectural atmospheres. In this regard, Park’s achievements through architectural drawings in his early years of practice reveal a unique characteristic of modern Korean architecture.

2. Methods and materials

As informed by the hermeneutic research approach,Footnote8 the author focuses on texts and architectural drawings found in governmental reports, journal articles, and books produced between 1904 and 1932. They include Chosen buraku chosa tokubetsu hokoku: dai 1-satsu (minka) [Special report on the investigation of the settlements of Joseon: vol. 1 (vernacular housing)], Chosen to Kenchiku [Joseon and Architecture], and Chosen bijutsu Shi [The History of Joseon Art]. Some of the figures used in this study are from Japanese and Korean archival materials. By rigorously reading and analysing these texts and drawings, the author tries to unpack the architectural meanings of modern Korean architectural representations.

3. Importance of drawingsFootnote9 in architectural imaginations

Even if computer-generated means of architectural representation, such as two-dimensional rendering images and three-dimensional digital models, have become very popular in contemporary architectural education and practice, architects continue to develop their ideas and concepts using hand drawings; hand-made physical models; and, sometimes, writings, as advocated by many eminent architectural academics of our time. As Robin Evans once argued that “it is true that imaginative work of architecture has for a long time been accomplished almost exclusively through drawing, though manifested almost exclusively in building”,Footnote10 among such architectural media, drawing is considered the most fundamental means by which architects imagine and design “good” architecture, as historically proven by great architects of all ages.

Hand drawings occupy an undeniably important position in the creation of architecture. Moreover, they provide viewers important clues to understand the embedded (hidden) architectural meanings or intentions. Commonly, but mistakenly, known as prototypical drawings for modern plans, sections, and elevations, according to Alberto Pérez-Gómez, the neat and clean drawings made by Palladio (1508–1580) for Villa La Rotonda represent his architectural ideals, rather than instructions for building construction.Footnote11 In this sense, an “architectural drawing is not a tool of reduction as contemporary architects and educators seem to misunderstand, rather it is the embodiment of architectural ideas” Pérez-Gómez (Citation1982). This imaginative and symbolic potential of architectural drawings was retained in later periods, as well. For instance, the famous etching series The Prisons by Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778), which seems indecipherable at first glance, indicates poetic architectural ideas.

In the testimonial essay titled “Paradoxes of the Ordinary” Moshen Mostafavi reaffirms that natural architectural drawings require several readings before they can realise the final product. This was clarified by Robin Evans in his essay “Translations from Drawing to Building”, as well. Mostafavi (Citation1997) By carefully analysing the work of Landhaus in Brick by Mies Van der Rohe, Sonit Bafna proves the possibility that “architectural drawings seem to function as works of architecture in their own right” Bafna (Citation2009). Even if the project is not meant for physical realisation, it draws our visual attention and makes us look for its invisible architectural qualities, such as material and structural properties; finally, it brings us experiential qualities with our enactive perceptual engagements to them.Footnote12

Architecture was imported into the modern Korean context as a new concept in the late 19th century. There is no evidence that Korean building traditions were formulated using autonomous architectural media portraying developing ideas.Footnote13 In this respect, the imaginative potential of architectural drawings in the sense of the aforementioned qualities never existed in the traditional Korean context. Instead, under Chinese cultural influences, the Korean building tradition was established by skilful craftspeople who did not consult any physical documents, and this tradition was passed down across generations for thousands of years. In the 18th century, some perspectival and axonometric paintings describing traditional built environments were produced.Footnote14 However, they are simple brush paintings that stylistically emulate their Chinese counterparts, and they were influenced by the contemporary scientific knowledge and skills introduced by Italian missionaries and merchants.Footnote15 .

Figure 1. An illustration of the Hwaseong Fortress published in 1801 (Source: Hwaseong Songyouk Eugye, The Construction Records of Hwaseong Fortress).

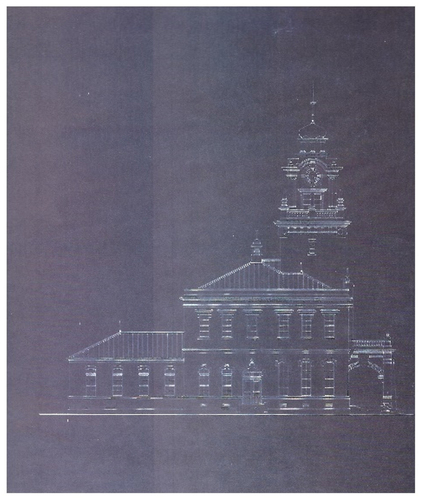

From the end of the 18th century, technical drawings started being circulated in the Korean peninsula, which signalled the beginning of modern architectural and civil engineering construction. Nevertheless, most of them were survey maps and topographical documents produced by the government for the nationwide application of a modern land use system. Under a more liberal and practical social atmosphere, the entire construction process of the Suwon Hwaseong Fortress was visually recorded for the first time between 1794 and 1796.Footnote16 However, the compiled documents are visual illustrations, rather than architectural drawings, supplementing post-construction textual records describing the building process. Toward the end of the 19th century, the Japanese and Western missionaries who started settling in the Korean peninsula produced construction drawings for their own purposes. Although these drawings are historically important since they portray the stylistic and material preferences of the time, it is difficult to find the aforementioned architectural qualities in these drawings. .

Figure 2. A construction drawing of Daehan Clinic, which was constructed in 1907 (Source: National Archives of Korea).

The potential of architectural drawings does not lie in their “notational” or “instrumental” qualities and representational accuracy. Rather, it is related to the depiction of future, entirely “imaginative”, buildings.Footnote17 When making drawings, architects mobilise their knowledge and personal experiences and project them to create visual narratives of human living conditions. By including “a special mode of visual attention”,Footnote18 architectural drawings create “communicative settings” that facilitate productive architectural experiences providing various levels of perceptual distance between the viewer and the viewed. Therefore, to understand the beginning of architectural drawings in the modern Korean context, it is important to study the efforts to modernise Korean building traditions that were initiated in the early 1900s. Even if they are limited to visual recordings of existing architectural objects, the drawings produced at the time reveal how architects mobilised, examined, and documented the period’s social norms and ideals.

4. Architectural drawings produced by Tadashi Sekino and Wajiro Kon in the early 1900s

With the complete support of Tatsuno Kingo (1854–1919), one of the first students of the government-appointed British architect Josiah ConderFootnote19 (1852–1920) and the department head of Tokyo Imperial University, architect and professor Sekino Tadashi first investigated Korean archaeological remains in 1904 to find Japanese architectural origins in the Korean peninsula. As a temporary employee of the Japanese Government-General of Korea, Tadashi investigated Korean artistic and architectural traditions and, along with writing a large number of official governmental reports, published the first architectural history book titled Chosen bijutsu shi (The History of Joseon Art) in 1932 Sekino (Citation1932). In this process, since he possessed a scientific mentality, Sekino used a comparative research methodology and measured and analysed the sizes and forms of the discovered artefacts to historicise them by visually proving the spread of stylistic developments from Korea to Japan.

Around the end of the 19th century, positivism was a popular topic of interest among academics in Japan, where the scientific and materialistic modernisation propagated by the government was carried out in many areas of study.Footnote20 To teach history in the Faculty of Letters at the Tokyo Imperial University, the Japanese government hired the German philosopher Ludwig Riess (1861–1928), who was a student of Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886) and an expert in the empirical historical approach. In particular, in Japan, education in the newly established field of architecture was modelled on that in Great Britain, and a group of English architects, including Josiah Conder, came to Japan to visit the architecture department of the Tokyo Imperial University. In 1896, Banister Fletcher’s canonical work on architectural history was imported to the Japanese architectural circle, and his famous diagram showing a tree structure of European architectural traditions in relation to their adjacent geographical areas became popular among young Japanese architects, who attempted to conceptualise Japanese architectural history in a highly hierarchical and stylistic manner.Footnote21

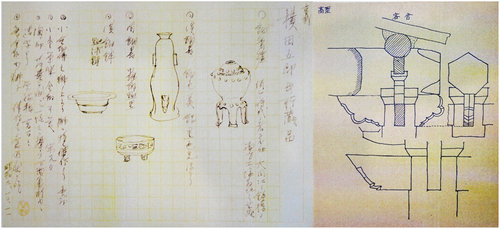

Being educated and practiced in this very specific academic atmosphere, Sekino was aware of the positivistic historical approach advocated by his colleagues and started using it to investigate Korean art and architectural traditions in the early 1900s. To understand and analyse these traditions, he used various types of documentation, including photographs, hand drawings, and texts.Footnote22 In particular, he was very interested in tracing the outlines and forms of objects that appeared totally detached from their surrounding environments. In this process, he emotionally and physically distanced himself from the artifacts that were under his careful visual inspection. As a result, he came to position himself as a passive “modern observer” of the views presented before his quasi-scientific eyes. .

Figure 3. Sekino’s architectural drawings of Korean living items and timber structural elements detached from their original places (Source: Sekino Tadashi Collection, Tokyo University).

Sekino’s varying interests included living items and even landscapes. When producing relevant hand drawings, he highlighted the objects’ three-dimensional qualities by adding shadows and perspectival techniques. His unique talent to extract physical forms is clearly depicted in his drawings of traditional Korean buildings. Similar to his consideration of still life drawings, Sekino regarded Korean architectural traditions objects that were free from their environmental settings and placed them in a three-dimensional space. Sometimes, he drew detailed architectural elements by separating them from the overall structure, whereas, at other times, he produced compositional drawings depicting structural ideas. In this manner, Sekino attempted to view Korean architecture as an object of mathematical and scientific investigations.

The idea of understanding architectural conditions as neutral and dismantlable objects of visual inspections became popular in the early colonial Korean context, and mainstream Japanese architects used this research methodology to study and document Korean building traditions. However, the early 1920s witnessed the emergence of a new perception on architectural conditions as detailed expressions of people’s everyday lives in relation to their environmental settings, and this perception was heavily influenced by the Japanese human geography tradition.Footnote23 Wajiro Kon (1888–1973) was one of the important proponents of this tradition. Despite being educated as an architect, Kon had a different perspective from the views of mainstream Japanese architects in the Tokyo Imperial University, such as Tadashi Sekino and Chuta Ito (1867–1954),Footnote24 who mainly focused on analysing physical forms and styles in architecture. Kon was very interested in discovering intimate relationships between people’s lifestyles and built environments and, in 1910, he started investigating the Japanese vernacular housing minka while travelling in Japanese areas with groups of archaeologists, folklorists, and geographers. .

Figure 4. Wajiro Kon’s architectural drawing portraying Korean people’s life in their built environments (Source: Chosen buraku chosa Tokubetsu hokoku: dai 1-satsu (minka)).

Following the Japanese Government-General of Korea’s invitation, Wajiro Kon investigated Korea’s traditional settlements in 1923 and 1924. In one of the occasions, he gave a lecture on Korean minka to the Korean public in Gyeongseong, which is the old name of Seoul. However, Kon’s onsite research intended to historicise Korean building traditions as inferior entities. Nevertheless, he was fascinated by the beauty of the peninsula’s architectural conditions. Revealing his inborn talent, Kon produced a large number of meticulous hand drawings of not only Korean native living environments but also furniture, clothing, and everyday living items detailing people’s ways of living. Consequently, this hands-on exercise became an invaluable asset for him in developing his unique research methodology, which is called Modernology. He used this methodology to rebuild the area in the aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923.

Izumi Kuroishi studied Kon’s architectural drawings in great detail. She opined that Kon was well aware of a phenomenological approach in understanding architectural conditions Kuroishi (Citation1998). According to her, Kon formulated his methodology while pursuing his early design education at the Tokyo University of the Arts, where he came to believe that art could emerge from everyday life, due to which he understood the importance of direct experience of reality.Footnote25 Based on this perspective, he developed a unique method to make architectural drawings of human living scenes by combining it with the act of observing and partaking in these scenes. Moreover, Kon allowed his readers to actively experience his readers to actively experience the scenes depicted in his meticulously produced hand drawings, which were rich in material and tactile qualities and found identified the theatrical potential of architectural drawings, which told stories on human life situations and depicted attentive architectural moods and experiences.Footnote26 Kuroishi once argued that Kon elevated hand drawings to the level of architectural creations.

In particular, Kon’s early architectural drawings of Korean minka pioneered the most intimate level of visual expression in the early modern Korean architectural context by minimising the physical and emotional distance between himself and traditional Korean settlements. Further, in his creations, he added explanatory texts in the margins, which helped readers expand their poetic imaginations by hypothesising potential living conditions. His embodied perceptions helped uncover the hitherto hidden stories of Korean domestic life. Kon viewed the Korean minka in relation to its surrounding material and topographical and environmental conditions, both natural and artificial. Finally, Kon’s early architectural achievements influenced the architectural perspectives of Kil-Ryong Park (1898–1943), the first modern Korean architect.Footnote27

5. Visualising the invisible: architectural meanings of Kil-Ryong Park’s drawings

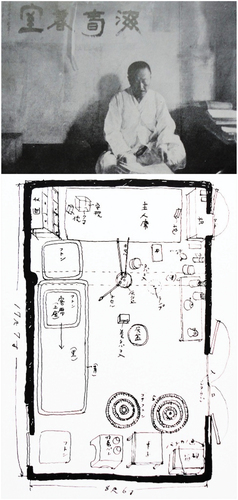

Kil-Ryong Park, who was educated by and who worked under the Japanese, is considered to be the first modern Korean architect who emerged from the Korean colonial space in the early 1920s. Because of the discriminative policies that were prevalent in the office culture of the Japanese Government-General of Korea, Koreans found it very difficult to obtain permanent government positions. Regardless, Park was able to overcome this issue and started work as an architectural assistant; he was followed by only a handful of Koreans, such as Yi Sang (1910–1937), who later became the most provocative modern avant-garde writer of the time.Footnote28 Due to the nature of the architectural education provided by the Japanese colonial government, Park was exposed to the positivistic architectural knowledge that circulated among the Japanese architects working in the Korean peninsula, most of whom were graduates of the Tokyo Imperial University.Footnote29 For 12 years as an architectural technician, Park was involved in important governmental projects, such as the Government-General Building in Gyeongseong and Joseon Exposition, all of which are known today for their dominant stylistic expressions. .

Figure 5. Renaissance Style design of the Japanese Government-General Building in Seoul designed with the Renaissance Style (Source: Chosen sotokufu shin cyousya syashin zu shuu mokuroku, 1).

As part of his public service, Park visited many areas in Korea with a Japanese architect Yoshiyuki Iwatsuki, who first coined the following statement: “Housing resembles people’s lives” Jung (Citation2015). This observation became very popular in the Korean colonial context of the 1930s. Park’s research trip in 1923 was a very special occasion since it enabled him to explore various types of vernacular housing that existed in the Korean peninsula; these explorations heavily influenced Park’s architectural ideas to develop Korean housing. As clearly specified by Iwatsuki in his article published in 1924, Park was responsible for documenting the characteristics of Korean minka by making several hand drawings of these houses. The tone of the article indicates that Iwatsuki and Park had common ideas on the minka’s architectural conditions in relation to their natural and environmental conditions, such as geographical and climatic ones, and the social, cultural, and political situations of the housing’s occupants, such as their customs, social status, religions, and political views. Moreover, they seriously considered personal instincts and interests Iwatsuki (Citation1924). As a keen reader and subscriber of Chosen to Kenchiku, the only architectural magazine that was regionally published at the time, Park was already well aware of Wajiro Kon’s similar architectural ideas on the Korean minka, which were published in 1922, 1923, and 1924 Kon (Citation1922); Kon (Citation1923); Kon (Citation1924).

In his later years at the Japanese Government-General of Korea, Park worked on finding ways to reform the Korean minka and contributed articles and architectural proposals to newspapers and journalsFootnote30 to share ideas with not only the educated Korean general public but also Japanese architects practicing in the Korean colonial context. It is well-known that Park was a member of the Korean Society of Science, and it is certain that he was blessed with a scientific mind that aimed to modernise traditional Korean housing conditions by providing design guidance and principles. Park’s architectural drawings of the time clearly indicate that he had progressed from his earlier joint minka research with Iwatsuki and was very interested in understanding the architectural conditions of the housing in relation to its physical and immaterial environments by visualising borders (demarcations) and thresholds with walls, floors, and doors in a more detailed manner, as well as providing orientational ideas for ventilation and lighting with suggestions for window placements. Moreover, Park described interior architectural elements to suggest people’s ideal ways of living in a traditional Korean setting. In particular, he carefully placed modern kitchen wares and supplies by considering their circulation and maintenance in the kitchen space and their connection to adjacent internal and external areas, such that the design maximises residents’ efficiency and well-being. .

Figure 6. Park’s architectural drawing of a reformed middle-class Gyongseong minka and its modernised kitchen space (with English text added) (Source: P Saeng, Jungbu joseonjibang jugaedaehan ilgochal (2), 56).

Park developed his quasi-scientific interest in creating idealistic architectural conditions further in the early 1930s. After resigning from his post at the Japanese Government-General of Korea, he started his own practice in the centre of Gyeongseong (Seoul) and worked with private clients to build small-sized projects in 1934. Prior to starting this effort, he was already working on propagating modern scientific (hygienic) ideas to the Korean general public by contributing a series of articles to Korean magazines and newspapers on how to reform traditional housing. As part of these efforts, he produced handmade perspectival drawings of interior architectural conditions and atmospheres, along with detailed plans and sections. Sometimes, he added annotated texts to the drawings to explain his unique architectural ideas. During this period, Park finally understood architecture as “a sapient working together of writing, drawing, and construction lines”.Footnote31

6. Visualisation of idealistic architectural atmospheres lacking real-life qualities

From 8 to 14 August 1932, Park contributed a series of articles on methods to reform the traditional Korean kitchen to the most influential newspaper of the time, Dong-A Ilbo (The Dong-A Daily Newspaper). To easily deliver his architectural ideas to a Korean audience, Park included perspectival drawings depicting imaginary scenes of the idealistic modern kitchen that, he believed, could play a leading role in reforming traditional Korean housing. Unlike their Japanese precedents,Footnote32 Park’s perspectival drawings comprise fine hard lines lacking any material or real-life qualities, and they create illustrative, didactic, and even futuristic atmospheres by portraying architectural prototypes for designing kitchen spaces. .

Figure 7. Park’s perspectival drawing of an ideal modern kitchen space (Source: Yeoseong, 1(1) (April 1936), 34).

Park developed several unique features in his visualisations of architectural ideas to design modern kitchens. By strictly adhering to perspectival drawing techniques, he intentionally placed the observer on a fixed position outside the scenes where he or she could view them only from a certain distance. This is very different from Kon’s hand drawings, where the observer is completely immersed in the depicted scenes and embodied human perception produces a series of stories on the details of the ways of living. Unlike Kon, Park shows what an ideal architectural model of a kitchen in the traditional Korean housing should look like and introduces scientific (efficient and hygienic) methods to design it using not only meticulously drawn interior architectural elements but also carefully arranged kitchen equipment and supplies without any clues to human presence.

Figure 8. A set of photograph and drawing by Wajiro Kon showing the interior atmosphere of Korean middle-class minka (Source: Chosen buraku chosa Tokubetsu hokoku: dai 1-satsu (minka)).

The educational significance of Park’s perspectival drawings is related to their lack of real-life qualities. Unlike Kon (whose animated drawings depict human living in detail), Park never included real moving people in his drawings, due to which the scenes create an atmosphere similar to that created by exotic and architectural pictures for commercial purposes, which maximally highlight their spatial qualities. On facing them, observers can visualise highly educated and enlightened, or idealised, modern human beings utilising technologically advanced spaces with new American lifestyles. In this sense, Park’s perspectival drawings are very modern in that they propagate the new and negate the old. .

Figure 9. Park’s perspectival drawings of reformed Korean kitchen spaces and technologically advanced kitchen wares with explanatory texts (Source: Jue daehaya [On Kitchen] (5), Dong-A Ilbo, 13 August 1932 (Left); Jue daehaya [On Kitchen] (6), 14 August 1932 (Right)).

![Figure 9. Park’s perspectival drawings of reformed Korean kitchen spaces and technologically advanced kitchen wares with explanatory texts (Source: Jue daehaya [On Kitchen] (5), Dong-A Ilbo, 13 August 1932 (Left); Jue daehaya [On Kitchen] (6), 14 August 1932 (Right)).](/cms/asset/09b6a6c3-cf57-4d26-84e2-81a8d0bf89ef/tabe_a_2171731_f0009_b.gif)

Furthermore, Park intended to visualise the detailed movements (circulation) and behaviours of the invisible modern person in a paradoxical manner. Accordingly, he described each kitchen item using a textual instruction of its specific use. For example, for the metal basket under the sink, the annotated text reads, it is for collecting garbage; for the hanger placed next to the entrance door, the text reads, it is for putting dish towels; for the closet under the sink, the text reads, it is for storing dishes; and for the table between the entrance and the sink, the text reads, it is for putting knives. By carefully looking at all the kitchen items and reading the relevant instructions, viewers can visualise enlightened human beings working very efficiently and hygienically in the kitchen space.

The presence of meticulously drawn small details enables Park’s perspectival drawings to allow viewers to imagine the architectural conditions that exist even outside the picture frames. These include areas blocked from views, such as the storage beneath the floor called mulchi for storing fire stull and food, and the basement under the kitchen hinted by its entrance. Advanced mechanical and systematic technologies can also be understood by the connection of water pipes to the sink’s faucet and that of the ventilation duct to the stove’s metal hood. Furthermore, viewers can hypothesise the air quality and lighting conditions affecting the kitchen’s atmosphere. By imagining the invisible through the visible, they can picture how the kitchen will work in the most controlled manner.

7. Visualising borders, demarcations, and thresholds

Park’s architectural drawings reveal that he considered the surrounding environmental and regional conditions while designing modern housing to satisfy their basic functions, such as lighting, ventilation, heating, and cooling. For this purpose, he created various types of architectural borders and thresholds between internal and external regions through windows, doors, walls, and even floors. In addition, Park created a series of thresholds for the architecture to interact with adjacent streets and neighbourhoods. It is not sufficient to simply indicate them as “gates”, as shown by a recent study.Footnote33 Rather, it is important to acknowledge that his architectural interests were very diverse in terms of understanding immaterial and material conditions. .

Figure 10. Park’s plan drawing of a small remodelled house and its surrounding site conditions (with English text added) (Source: Park, Gaelyang sojutaegui ilan, 45).

Figure 11. Park’s detailed plan and section drawings showing modern Korean kitchen spaces interacting with their adjacent microscopic physical and environmental conditions (with English text added) (Source: Jue daehaya [On Kitchen] (3), Dong-A Ilbo, 11 August 1932 (Left); Jue daehaya [On Kitchen] (4), 12 August 1932 (Right)).

![Figure 11. Park’s detailed plan and section drawings showing modern Korean kitchen spaces interacting with their adjacent microscopic physical and environmental conditions (with English text added) (Source: Jue daehaya [On Kitchen] (3), Dong-A Ilbo, 11 August 1932 (Left); Jue daehaya [On Kitchen] (4), 12 August 1932 (Right)).](/cms/asset/ddd84738-4bcd-4a26-967c-ccddc65c4855/tabe_a_2171731_f0011_b.gif)

Park’s microscopic architectural approach to clarify these conditions is clearly reflected in his detailed plan drawings; he carefully created a wide window facing south, to enable the flow of natural light into the kitchen and clear views of the backyard. To provide ventilation, he placed windows facing each other to facilitate natural airflow in the kitchen. This is the case with the placement of the burner and the hood close to the window, as well. These enable the direct eviction of cooking smoke to the outside. Further, Park aligned the kitchen’s floor level with the ground level so that the kitchen became a semi-outdoor space where people could freely move inside and outside through the door. Inside the kitchen, he designed a wooden floor called maru, which is elevated from the bottom; it worked as a transfer space from the kitchen to the adjacent room and could be used as a space to cook and store food, as a semi-kitchen space.

In addition, Park’s interest in creating borders and thresholds is reflected in the details of the sectional drawing, where there is an in-between space with doors on both sides. This space works as a border and as a connection that is open to both the kitchen and the room, through which residents can make visual and material exchanges on a daily basis. In the same drawing, Park reveals how the architecture sits on its ground, as well. He made use of the traditional Korean floor-heating system ondol; Park carefully considered how to design the foundation of the house in relation to the ground to incorporate the ondol system and decided on the placement of the furnace and facilitating the flow of smoke from one end to another. In this process, it is obvious that he studied topographical conditions and functionally designed various architectural levels accordingly.

8. Discussion and conclusions

By understanding the two contrasting architectural knowledges of the time, positivism, and Japanese human geography, as well as the ideas of Japanese architects who had developed the ideas into their own architectural expressions, the first modern Korean architect Kil-Ryong Park established unique architectural approaches to understand traditional Korean settlements. Based on the contemporary socio-cultural atmospheres that advocated the use of scientific knowledge (e.g. efficiency and hygiene) in proposing ways to reform every detail of Korean people’s lifestyles, Park’s architectural intentions can be considered highly educational, and his drawings portray architectural rules and principles to design ideal human living conditions.

Park took advantage of the perspectival techniques that were popular in Japanese sources to deliver his architectural ideas to the Korean general public. In particular, he never included material or real-life qualities in his scenes, where viewers could only look at the carefully choreographed living items from a fixed position at a certain distance. In this manner, Park aimed to create ideal architectural settings for a model home, and an enlightened modern person can imagine the viewers’ thoughts regarding these settings. Park also understood the importance of language in creating poetic architectural atmospheres and believed that the invisible movements of the hypothesised human, as well as the highly controlled mechanical and systematic, environments annotated in the scenes produce a didactic narrative.

Moreover, Park considered microscopic climatic and topographic conditions, which reveal his interest in creating architectural borders and thresholds both inside and outside his housing proposals; these clearly shown in his detailed plan and section drawings. In doing so, he proved that his architectural interests were not limited to create fictional project-related conditions. Rather, he tried to provide practical questions on how architecture interacts with its surrounding physical and neighbourhood conditions. Therefore, the architectural meanings of Kil-Ryong Park’s drawings lie at the intersection between the visible and invisible, and he not only created ideal modern architectural atmospheres and narratives portraying scientific and hygienic knowledge but also addressed practical issues associated with architectural construction.

This study approached the original texts and drawings of the first modern Korean architect, Kil-Ryong Park, from a hermeneutic approach and unveils the unexplored aspects of his architectural drawings. The study contributes to current scholarship investigating the beginnings of modern Korean architecture in terms of diversifying its research scope. However, this study does not explore how Park’s architectural legacy has survived in the works of subsequent Korean architects and architectural researchers in the pre and post war periods, indicating possible directions for future studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yoonchun Jung

Yoonchun Jung is an assistant professor at the Hongik School of Architecture. His work has been published at the Montreal Architectural Review, Journal of Architecture and Architectural Theory Review.

Notes

1 Numerous construction drawings were produced by Koreans in the late 19th century; however most of them are technical drawings and survey maps made for governmental purposes. They are not architectural drawings in the sense that they do not provoke “productive human imaginations and atmospheres”.

2 Architectural theoretician Alberto Pérez-Gómez describes the architectural importance of visualisation while analysing the architecture of John Hejduk in his collection of essays. See Pérez-Gómez (Citation2016).

3 Architectural historian Izumi Kuroishi introduced this Wajiro Kon’s unique architectural approach to his objects for investigation. See Kuroishi Citation1998).

4 French philosopher Paul Ricoeur (1913–2005) argued that creative human imagination has a linguistic origin. See Ricoeur, (Citation1979).

5 Regarding the research field trip made by Iwatsuki and Park, See Jung (Citation2015).

6 Previous studies on Kil-Ryong Park only highlight his architectural efforts on reforming Korean housing architecture with utilitarian ideas. See Soon-Ae (Citation1987); Seog-Ki (Citation1993).

7 Alberto Pérez-Gómez described the importance of architecture in the creation of communicative settings.

8 This research employs the hermeneutic research approach to highlight the importance of human imagination in interpreting old architectural texts. By maximising the poetic potentials of language and by tracing the discontinuities within official history, the research creates new stories that can and they can continuously generate important architectural discourses for the present and the future. See Pérez-Gómez Citation2016a).

9 In this paper, I use the term “drawing” to indicate “sketching”. Both the words have symbolic meanings and are different from the term “reductive diagram”, which refer to notational and instrumental aspects. See Sonit (Citation2008).

10 See Evans (Citation1984); To understand the importance of writing in architecture, see Sioli and Jung (Citation2018).

11 Alberto Pérez-Gómez argued that the drawings were modified in relation to site conditions at the time of physical construction.

12 See the essay by Sonit Bafna.

13 “Renaissance architectural drawing was perceived as a symbolic intention to be fulfilled in the building, while remaining an autonomous realm of expression”. See Alberto Pérez-Gómez, “Architecture as Drawing,” 2.

14 In the Western architectural perspective, Isometric and Axonometric drawings are not simply techniques for representation. They included provocative ideas regarding human conditions in built environments. See Pérez-Gómez and Pelletier (Citation2000).

15 To understand this context, see Sŏng-mi (Citation2015).

16 Hwaseong Fortress is widely known to have been designed by the prominent Silhak scholar Yakyong Jeong (1762–1863) of the Joseon dynasty; in this construction, Jeong designed a crane for the first time in Korea.

17 The term “notional” is borrowed from Sonit Bafna’s article to deliver ideas as opposed to the ideas for “imaginative”.

18 Sonit Bafna, “How architectural drawings work – and what that implies for the role of representation in architecture,” 535.

19 In 1877, British architect Josiah Condor was hired by the Japanese government to teach architecture at the Tokyo Imperial University.

20 Positivism refers to a philosophical theory that forms the basis of an ongoing debate relevant to multiple academic disciplines. Essentially, a positivist approach posits an objective reality, the knowledge of which can be discovered through empirical methods, while considering alternate forms of knowing (interpretation or intuition) meaningless. See Von Hayek (Citation1979).

21 “Banister Fletcher’s A History of Architecture was originally published in 1896 and in 1919 was the first historical book on architecture ever translated into Japanese, but it was not until the book’s sixth edition, in 1921, that a separate chapter on Japanese architecture was added. Ten years before the Japanese translation of the first edition, historian Chuta Ito criticized the book’s eurocentrism, but still used Fletcher’s theoretical structure to imagine his own parallel history of Japanese architecture – a simultaneity of acceptance and rejection that has come to define Japan’s relationship with western architectural history” Yatsuka (Citation2009).

22 They are stored at the Sekino Tadashi Collection in the Tokyo University.

23 Takeuchi argued that Japanese human geography as an independent field of study was initiated in relation to the emergence of localist Japanese consciousness toward the end of the 19th century. See Takeuchi (Citation2000). More ideas on the Japanese human geography are found in the same book; the Japanese human geography used Japanese geographical features to explain how the Japanese had formulated their peculiar living and dwelling conditions. (Ibid., 123).

24 As a process of incorporating Japanese building traditions into a realm of the Western concept of architecture, Chuta Ito invented the Japanese term Kenchiku to indicate architecture.

25 Ibid., 130.

26 By using their creativity, viewers can imagine a series of new detailed narratives on people’s ways of living.

27 Since Wajiro Kon’s first publication on Korean minka came out in 1922, it is most likely that Park already knew about Kon’s analyses on Korean minka. Further, Park mentioned Kon in one of his writings published in 1924.

28 To understand the architectural importance of Yi Sang, see Jung (Citation2018).

29 Previous studies on Park clearly show that he took advantage of newly introduced scientific and utilitarian knowledge to reform traditional Korean housing conditions. Park compared Korean minka to the human body, using functional and biological terms to indicate architectural forms. See Saeng (Citation1928).

30 The main media for these efforts were Chosen to Kenchiku and Chosen, both of which were governmental magazines that propagated Japanese colonial policies in Korea.

31 Marco Frascari once argued that “architecture stems from a sapient working together of writing, drawing, and construction lines”. See Frascari (Citation2009).

32 Several contemporary Japanese perspectival drawings portray modern kitchen spaces. However, they are more realistic since they show traces of human presence in the depicted scenes.

33 See Woo (Citation2016). Woo argues that Park introduced gates in his architectural proposals.

References

- Bafna, S. 2009. “How Architectural Drawings Work - and What that Implies for the Role of Representation in Architecture.” Journal of Architecture 13 (5): 535.

- Evans, R. 1984. “In Front of Lines that Leave Nothing Behind.” AA Files 6: 96.

- Frascari, M. 2009. “Lines as Architectural Thinking.” Architectural Theory Review 14, (3): 200–212.

- Iwatsuki, Y. 1924. “Chosen Minka No Ie Gamae Ni Tsuite” [On Joseon Vernacular Housing Structure].” Chosen to Kenchiku 3 (11): 2–3.

- Jung, Y. 2015. “On Kil-Ryong Park: ‘Housing Is a Vessel Containing People’s Lives’.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 14, (2): 255–262.

- Jung, Y. 2018. “The Architecture of Yi Sang’s Nalgae.” In Routledge Companion on Architecture, Literature and the City, edited by J. Charley, 136–151. London: Routledge.

- Kon, W. 1922. “Chosen No Minka Ni Kansuru Kenkyu Ippan” [Regarding the Study Related to Joseon Vernacular Housing].” Chosen to Kenchiku 1 (5): 2–11.

- Kon, W. 1923. “Sotokufu Shinchosha Wa Rokotsu Sugiru [The Government-General Building Is Very Outspoken].” Chosen to Kenchiku 4 (2): 17–19.

- Kon, W. 1924. “Minka to Seikatsu [Vernacular Housing and Living].” Chosen to Kenchiku 10 (3): 1–8.

- Kuroishi, I. 1998. “Kon Wajiro: A Quest for the Architecture as a Container of Everyday Life.” PhD diss, University of Pennsylvania.

- Mostafavi, M. 1997. “Paradoxes of the Ordinary”. In Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays, 9. London: Janet Evans and Architectural Association Publications.

- Pérez-Gómez, A. 1982. “Architecture as Drawing.” Journal of Architectural Education 36 (2): 2.

- Pérez-Gómez, A. 2016a. “John Hejduk’s Critical and Poetic Architecture.” In Timely Meditations, Selected Essays on Architecture, 383. Vol. 1. Montreal: Right Angle International.

- Pérez-Gómez, A., and L. Pelletier. 2000. Architectural Representation and the Perspective Hinge. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Ricoeur, P. 1979. “The Function of Fiction in Shaping Reality.” Man and World 12 (2): 123–141.

- Saeng, P. 1928. ““Jungbu Joseonjibang Jugaedaehan Ilgochal(2)” [A Study on the Joseon Housing from the Central Region (2)].” Chosen 128: 55.

- Sekino, T. 1932. Chosen Bijutsu Shi [The History of Joseon Art]. Keijo: Joseonshi gakukai.

- Seog-Ki, S. 1993. ““Park Kil Ryong Ui Geonchugjagpum Teugseonge Gwanhan Yeongu” (The Characteristics of Park Kil-Ryong’s Architectural Works).” Master’s Thesis, Yonsei University.

- Sioli, A., and Y. Jung. 2018a. “Introduction”. In Reading Architecture: Literary Imagination and Architectural Experience, 1–5. London and New York: Routledge.

- Sŏng-mi, Y. 2015. Searching for Modernity: Western Influence and true-view Landscape in Korean Painting of the Late Choson Period. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Sonit, B. 2008. “How Architectural Drawings Work — And What that Implies for the Role of Representation in Architecture.” Journal of Architecture 13 (5): 540.

- Soon-Ae, C. 1987 ““Park Kil-Ryong ui saengaewa geonchugegwanhan yeongu” (A study on Park Kil Ryong’s Life and Architecture).” Master’s Thesis, Hongik University.

- Takeuchi, K. 2000. Modern Japanese Geography: An Intellectual History, 22. Tokyo: Kokon shoin.

- Von Hayek, F. A. 1979. The counter-revolution of Science: Studies on the Abuse of Reason, 124–125. Indianapolis: Library Press.

- Woo, D. 2016. “On Park Kil-ryong’s Discovering, Understanding, and Designing of Korean Architecture.” In Constructing the Colonized Land: Entwined Perspectives of East Asia around WWII, edited by I. Kuroishi, 193–214. London: Routledge.

- Yatsuka, H. 2009. “Autobiography of a Patricide: Arata Isozaki’s Initiation into Postmodernism.” AA Files 58: 68–71.