ABSTRACT

Based on historical documents and field investigations, this article analyzes the origin and development of the concept and form of the Chinese courtyard “TianJing” in vernacular residences to address common misunderstandings in previous studies. Focused on the scale standard in YingZaoFaYuan traditional building technology in the JiangNan region, TianJing is closely related to the main hall in dwellings reflecting the construction customs in different regions. Through the statistical analysis of the measured dimension data, this study shows the scale characteristics, demonstrating the cultural correlations of vernacular residences in different regions based on similarities. It explores the causes, rules and effects of and changes in traditional construction wisdom reflected by the historical geographic comparative background.

1. Introduction

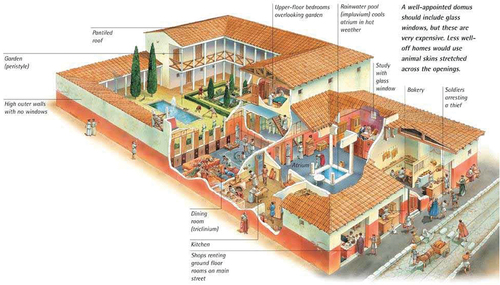

Courtyard, as a traditional living space type, is a common traditional residence language all over the world. It is the main form of traditional residential buildings in all periods of history, creating a variety of living, production and communication space, as well as the material carrier of different regional cultures. For example, Atrium in Greece (Vitruvius Citation1960), Impluvium in Rome (August Citation2010), Konaks in Turkey (Dönmez Citation2021), Persian residence in Iran (Farzaneh, Mehdi, and Seyed Citation2016) and Chowku in India (Malcolm and Rajan Citation2018) are all typical representatives of courtyard types in traditional residential buildings around the world. Chinese architecture is no exception. Similarly, with courtyard space as the main body, various palaces, halls and pavilions are organized to form the traditional architectural space with Chinese cultural connotation. As a unique type of Chinese courtyard, TianJing exists extensively in residential buildings and is a typical type of traditional residential culture.

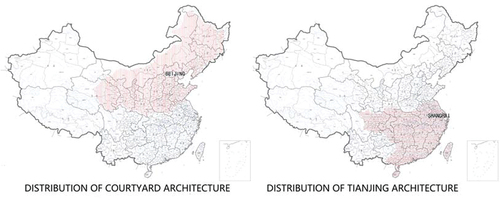

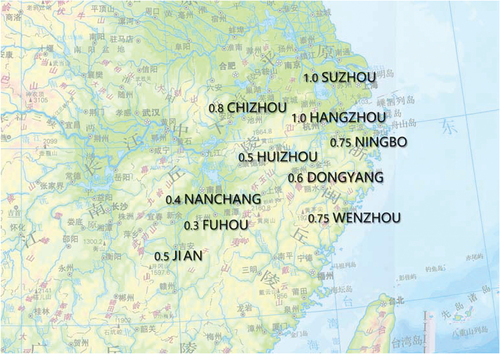

The Chinese character of “TianJing”, composed of the two words, “Tian” (sky) and “Jing” (well), refers to a type of courtyard in traditional architecture. When mentioned in literary works, TianJing is often referred to as HuiZhou Vernacular Architecture, which is related to many fantastical artistic conceptions loaded with high walls, triple doors, narrow windows and small yards in the traditional environment. However, this has led to the misunderstanding of TianJing as an architectural element. The TianJing-form is widely distributed in most of South China as the main type of traditional residence, from the JiangNan region, such as in SuZhou and HuiZhou, to the Southeast, LingNan, Southwest and other southern areas of China (), especially south of the Yangtze River (JiangNan region).

TianJing is an essential element of traditional residence construction as the central space connecting the main hall, wing room and gate house. It was considered a product of the courtyard living mode brought by the Han people from the Central Plains to the South and combined with the local Pile-House structure form in the Yangtze River Basin (Zhang Citation2002). As a representative residential type in southern China, TianJing is different from courtyards in the north and is influenced by geographical conditions, climatic conditions and construction customs. There are obvious geographical boundaries between the distribution range of TianJing and the other types of residences. However, what is the difference between TianJing and the these other types? Is it only the scale? Is it an outdoor space or an internal part? What is the standard size of TianJing and its relationship to other styles? Are they all the same in the JiangNan region? These questions have not been answered clearly in the current literature and are, only seen as concerning issues of space, form, function and cultural significance, such as wealth and prosperity. Although TianJing has a similar combination mode in vast South China, there are also explicit and invisible regional differences and geographical boundaries, which are worth studying from an architectural perspective.

2. Origin and definition

The Chinese word “TianJing” first originated from Sun Tzu’s Art of War in the Spring and Autumn Period (Sun Citation2001),Footnote1 as an ancient proper noun in geography indicating a place that is steep on all sides with a stream in the middle. This definition endured until the Tang Dynasty (Huang Citation1999) when it began to be used as an architectural element, initially describing a caisson ceiling at the top of buildings. The poem Chang’an Temple by Wen TingYun of the Tang Dynasty states: treasure oblique jade, TianJing inverted hibiscus (No. 577. Peng Citation1960). Another poem, TaiYe Pool Song, states: the billows shine on TianJing indefinitely, and the reflection swings and grows clear and emerald (No. 575. Peng Citation1960). In this period, TianJing, meaning courtyard, referred to the word “YueJing”,Footnote2 such as Li ShangYin’s poem Incense Song: the YueJing in the court is red, with a light shirt, which is gentleman’s intention (No. 541. Peng Citation1960). The meaning of TianJing primarily referring to military terrain still existed and indicated the decoration of the caisson ceiling, which is the same as “てんじょう” in Japanese.

There is no indication of when the meaning of TianJing changed from caisson to yard, but it occurred no later than the Song Dynasty. The poem CeFan by Yany ZeMin of the Song Dynasty states: In the orchid room, people return at late night. Moonlight outside the window shining on the square TianJing (Tang Citation1965). This was probably an earlier record of TianJing referring to courtyards in the same way as today. At that time, few people still used the term specifically to describe the military terrain. TianJing has been widely used as describing a type of courtyard from the Ming and Qing Dynasties utill now and has been clearly used in this way in many traditional books, such as Key Points of Residence,Footnote3 Eight Bright Mirrors of Houses,Footnote4 and ClassicMeasures for Residence.Footnote5

In previous studies, TianJing was defined as an open space surrounded by three or four sides, and its scale was determined by the size of eaves, or it was simply defined as a narrow courtyard (Cihai Editorial Committee Citation1999). As a Chinese architectural entity, “Jing” (well) with the word “Tian” (sky) has become a space of “no use”.Footnote6 This space was always the core part of ancient houses, and a similar type in the West may offer reference value to compare the relevant definitions.

In ancient Greece in the 5th to 6th centuries BC, there were courtyard-style residences with pillars surrounding a yard enclosed by bedrooms, kitchen, master and rooms for the master and servants. The structure was called the “Peristyle” and the yard the “Atrium”. The Peristyle residence gradually matured and stabilized in the ancient Roman period. In the typical ancient Roman house (), there was a hollow square well in the centre of the roof and a square reservoir to receive rainwater at the corresponding position on the ground (), which was called the “Impluvium”Footnote7 (). According to an etymological analysis, “im-” means introverted and internal, and “-pluvium” refers to an object impacted by water. Therefore, Impluvium refers to the pool of water on the ground. However, Vitruvius summarized five types of eaves: Tuscanisch, Viersaulige, Korinthische, Displuriatum and Testudinatum. He also stipulated the design rules of the Impluvium scale; for example, the aspect ratio was generally 5:3 or 3:2, while the length to height ratio was approximately 4:3. (Vitruvius Citation1960).

Similarly, in ancient Egypt, “Megaron” was the main hall surrounded by groups of rooms, and in the Islamic world, residences centered on the Iwan Hall, with the functions of bringing daylight into the home and providing a space for rest and convenience (Leonardo Citation1990) (). This is similar to the Japanese term, which means the caisson and the highest place inside the structure. Thus, compared to the courtyard enclosed by rooms, TianJing may be interpreted as a “hollowed out” part of a building.

From a plane layout, there may be no obvious difference between TianJing and courtyard; both are open spaces surrounded by houses on three or four sides. However, the essential difference between them can be revealed by the roof above (). In the TianJing style, the “purlin lap purlin” frame method is connected between the main and wing houses, which use common columns to support their purlins. Because of the integrity of the frame, the roof is connected, and the cornice is closed. Although the cornice is staggered up and down, it is still connected to the cornice in the plane sense, forming a “wellhead”.

TianJing is defined as an open space between two buildings directly related to roof drainage in Chinese architectural documents YingZaoFaYuan, which summarize the rules of traditional building technology in the JiangNan region. In the book, “Jian” means the boundaryFootnote8 from the eaves between two houses. It is stipulated that the eaves should not extend beyond a home’s walls and that dripping from the eaves must fall in that home’s own TianJing (Yao Citation1986). “Jing”, a well, came to mean a yard with the image of water at the bottom. Similar to a well in the ground, TianJing connected the sky and collected the water from the eaves with an edge contact closure at the top. Compared with an indoor floor, the bottom of TianJing is often a sinking square pool or ring groove, with size, depth, shape, material and carving varying by region. These features distinguish them, whether connected to the upper cornice or the lower foundation (Chen Citation1999). Therefore, the dimensions of TianJingshould be defined as the size of the ground pool or the roof cornice enclosed.

3. Typology of TianJing

3.1. Type elements

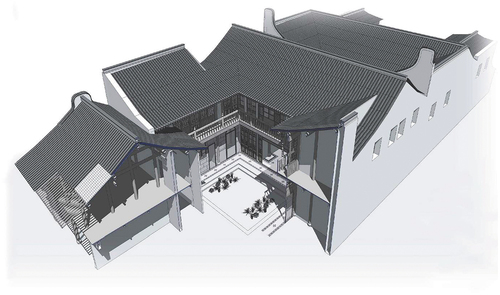

TianJing is connected to the main hall, wing rooms and entrance or enclosure, which are combined as a basic unit. As the central space of the plane unit, TianJing has not only the function of improving the internal environment of the house but also the spiritual significance of Chinese traditional humanism.

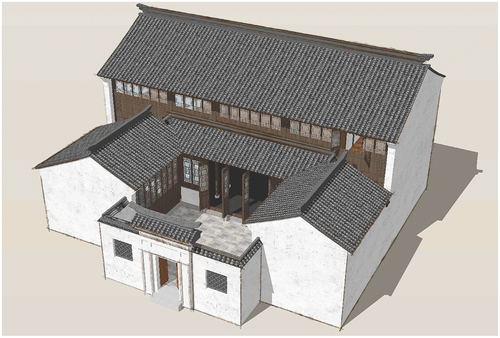

3.1.1. Hall and rooms

The main hall is usually an open or semi-open space with an odd number of bays located on the central axis as the significant part of dwellings (). To highlight its status, a lobby or entrance in the front to increase the spatial level, and the back hall is set behind to increase functions. These are called “three halls”: the front, main and back halls. In some large families, there are enclosed rooms with delicate porches or gardens behind the main hall. This not only shows the distinction of the host but also reflects the traditional living concept of symmetrical balance, internal and external differences and orderly levels.

There are three types of halls: open, semi-open and closed. The open type includes a single- or double-sided open hall and veranda hall, and the semi-open hall often appears in TianJing-style dwellings with the front open and the rear closed. If there is a back hall behind the main hall, it is usually closed as a living space. The open hall is generally located between the entrance and main hall, such as the Pass Hall in SiChuan and the Sedan Chair Hall in SuZhou. In addition, there are auxiliary rooms such as kitchens, firewood rooms, livestock pens and toilets, which are often arranged in the leftover area around the main building through the ingenuity of artisans, using idle space or according to the base conditions. This flexible design has no fixed form and adapts measures to local conditions, thus diversifying vernacular dwellings. The space of the settlement is also uneven, which gives traditional buildings rhythmic, orderly and vividly colorful characteristics.

The wing rooms are arranged around the main hall, and the relationship among them is in accordance with the strict hierarchy and distribution of family generations and seniority They are generally ordered from east to west and from north to south in the JiangNan region.

3.1.2. TianJing

TianJing, connecting the hall and rooms, forms a complete living space. It can be a place for daily life and work or for visitors and friends as a saloon, which is a space full of vitality with cultural and practical value. The wellhead of TianJing is connected with eaves and rings. Even if the eaves of a house or room wall fall up and down, it is still a continuous eave in the plane sense, and the eaves of the front and compartment remain open. The pool at the bottom of the TianJing is generally not deep, and the depth, size, material and carving of the pool vary by region. Its main forms are ring groove, square pool and pit pool.

In the ring groove form, there is a port in the center of the well and a slightly deeper drainage ditch around it, called “earth-shaped TianJing” (). If there is only a square pool, no exposed drainage ditch, and the bottom is flat, the type is called “water-shaped TianJing” (). Houses in the Ming Dynasty mostly used the water-shaped TianJing without a port, and the TianJing was relatively deep. However, in the Qing Dynasty, there were many ports in TianJing, which attached great importance to finishes and pavement. Most were paved with slabstone, while others were paved with local materials (Huang Citation2008). The pit pool form had the function of water storage, with breast boards set at the edge (). Because of its ornamental nature, it was usually used in places of leisure, such as study and flower halls, to increase aesthetic interest.

There are two ways to drain the water from the roof into the TianJing pool. One is by an underground ditch in an organized way. The other is to use blind ditch cover layers of thin bricks with a pebble filter layer or to use a bluestone slab so that water can directly penetrate the ground and drain. The roof drainage is mainly unorganized, and far-reaching eaves make the rainwater flow directly into TianJing. There are also drainage pipes on the cornice for organized drainage ().

3.1.3. Combination mode

On the combination of traditional architectural space, the basic plane unit of TianJing can be divided into three modes: the “four in one”, which is fully surrounded by houses; the “three in one”, surrounded by houses on three sides and a wall in the front; and the “two in one”, surrounded by houses on two side sides face to face and walls on the other sides (). Various organizational models have two essential elements, house and walls, to create flexible courtyard space.

The main and front halls of the “two in one” are independent buildings that cannot form a whole, which is inconsistent with the characteristics of TianJing connecting the eaves on the top and the foundation on the bottom”. Therefore, the basic unit mode of TianJing architecture is generally “three in one” enclosed by houses and a wall and “four in one” enclosed all around by houses. The basic units are combined and expanded in both the vertical and horizontal directions. The combination mode is adapted to different external environmental conditions, and the architecture community has also created a vernacular style that is harmonious with nature, which reflects the flexibility and adaptability of Chinese buildings.

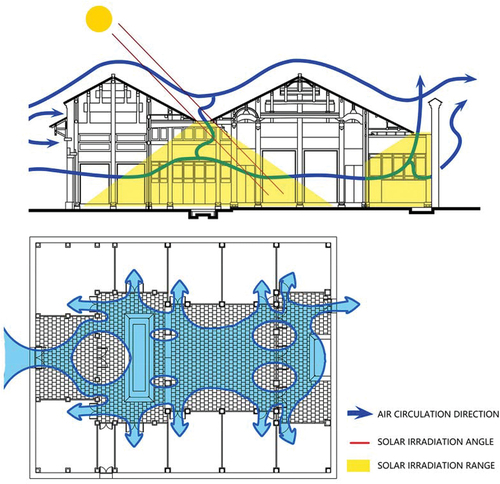

3.2. Physical characteristics

Traditional buildings are often enclosed by walls to prevent theft with few windows. The airflow in airtight rooms is not smooth, and natural wind dramatically attenuates after entering rooms, so it is difficult to achieve effective ventilation. Therefore, the ventilation of the whole house greatly benefits from the use of TianJing space, which is also effective for heat protection and dehumidification, adapted to the climate of South China. The halls in the south are generally open and connected with TianJing to form an air flow path. The building is ventilated by introducing the external natural wind to generate pressure throughout the TianJing. Even if there is no wind outside, the vertical thermal pressure difference formed can also produce a ventilation effect for sun shading and thermal buffering (). Research shows that the temperature in places with direct sunlight can be 15°C higher than that in the shade (Yuno Citation1975). Due to the large height width ratio of TianJing, the lower part is weakly exposed to the sun, while the upper part is strongly exposed. There is a vertical temperature difference between the upper and lower parts of the air, thus realizing thermal pressure ventilation. The greater the aspect ratio is, the better the effect is of hot pressure ventilation, which is commonly called “pulling wind” in folk terminology. In southern Fujian and Taiwan, this TianJing pattern is often referred to as the “deep well”.

The wind-pulling function and the interception of the gable can also prevent flames from spreading to surrounding areas through the air traction when a building is on fire. A house is separated into corresponding fire compartments by several TianJing. When a fire occurs, it can be controlled in one TianJing yard to prevent it from spreading to the entire house.

TianJing also plays a role in regulating indoor lightting. For example, the construction of dwellings in FuJian and GuangDong often uses the method of “Over-White”Footnote9 to integrate sky light directly into the hall (). The main rooms inside have windows facing the TianJing to meet demand for the indoor light.The bonsai, rockery and flower pool in TianJing also improve the microclimate inside the building, giving the indoor and outdoor spaces dual functions of use and aesthetics.

Figure 18. Over-white method of architecture construction in GuangDong (Lu Citation2003).

3.3. Type characteristics

It is difficult to distinguish the southern TianJing architecture from the northern courtyard style in terms of shape. However, these two words are confused in many fields. For example, craftsmen in SiChuan believe that the two concepts are the same, while in HuNan, they call the yard inside the house TianJing and the dam outside the gate a courtyard. Previous studies have noted differences in style between TianJing and courtyards based on contiguous or decentralized layout relationships between buildings (Liu Citation1990). The two styles are distinguished by national and climatic characteristics from the TianJing style in the south and the courtyard in the north (Lu, Citation1995). The climate in the north is wet and dry, and courtyard houses are favored by the Han, Man and Hui people. In the south, it is wet, rainy and muggy. Many nationalities, such as the Han, Bai, and NaXi, use the TianJing style.

The traditional courtyard architecture can be traced back to the early Zhou Dynasty through the excavation of the Fengchu, which can be seen in the first complete layout of courtyard architecture in QiShan County, ShaanXi Province (. Fu Citation1998). The foundations of the houses at this site are higher than the ground, and all are connected except for the passageway at the doorway. The doors, halls and rooms have their own walls, making them independent buildings. Although the plane type of the site is connected with the platform foundation, it still belongs to the courtyard building type due to the independence between houses. The basic feature of the courtyard type is that the main houses are separated from each other and arranged independently, connected by corridors. It has the advantages of sunshine, wind protection and sand, and is suitable for the cold winter climate in northern China.

Figure 19. Plan of the FengChu building foundation in the Early Western Zhou dynasty in QiShan, ShaanXi (Fu Citation1998).

Based on the shape characteristics of the eaves and foundation, we can distinguish the differences between TianJing and courtyard, as shown in . The investigation, which cannot replace case studies, does not indicate that all the cases belong to the same mode. There is also some form of intermediary between different modes, which is of great significance for studying regional architectural types.

Table 1. Comparison of differences between TianJing and courtyard.

Due to population migration and cultural integration throughout history, there are numerous types of residential architecture in China. Through these differences, we can see that courtyard buildings are roughly distributed in northern China, including Northeast China, North China, ShanXi, ShaanXi, NingXia and other vast areas in the upper reaches of the Yellow River. The TianJing type mainly covers the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, including the southwest and southeast regions (Yu Citation2001).

The two types are distributed in a north–south pattern, corresponding to the courtyard in the north, which is sufficient to show the status and influence of TianJing as one of the two types of traditional residences. In the large-scale north–south transition zone between the Yellow River and the Yangtze River, the cultures of the Central Plains and the Southern Civilization collide, which is also reflected in the blending and mixing of the two classic forms ().

4. Scale of TianJing

4.1. Spatial rules

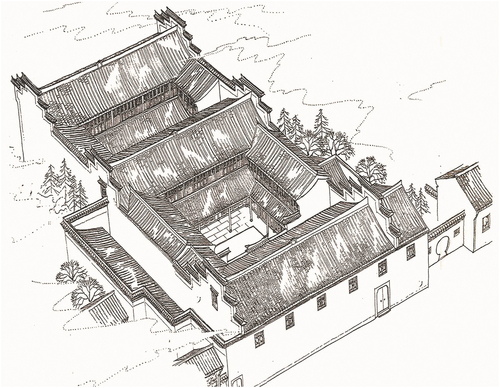

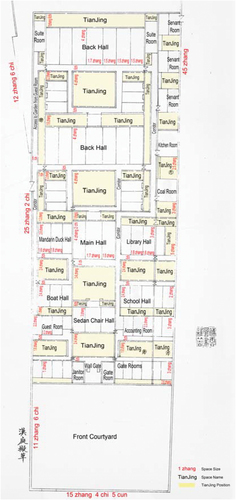

The number and types of TianJing in traditional Chinese dwellings are extremely rich. There are as many as 37 TianJing in one group of JiangNan dwellings in the book Yao ChengZu Drawings in YingZaoFaYuan assembled by Chen CongZhou Chinese traditional garden master (Chen Citation1979). In one picture, in front of the house is a large TianJing used as a courtyard outside (). In the houses, half of the TianJing is built on both sides to improve indoor lighting conditions, which is called “tiger eye TianJing”. There is also a port in the center of the pool in the TianJing, surrounded by drainage ditches, called “earth shaped TianJing”. There are also more slender TianJing whose scales are narrow due to limitations on land use, vividly called “eyebrow TianJing”.

Figure 21. Plane figure I of Yao ChengZu drawings in YingZaoFaYuan (Chen Citation1979).

The types of TianJing in other regions are more complex. For example, there are “dry TianJing” and “wet TianJing” in JiAn, Jiangxi Province, which are divided according to whether they receive rain directly. Some TianJing become a very narrow gap, which is called the “Door of Sky” in FuZhou. This narrow TianJing changes to a skylight in some buildings, whose function of receiving rainwater has disappeared so that they retain only the function of receiving daylight. In LiChuan, there is also an open and closed TianJing with guide logs and movable lattice sheds. In the southeast of Hubei Province, there is a Tian DouFootnote10 type with pyramids on the top of TianJing, which is called the “Dou Ting” (Funnel-Shaped Hall) by local artisans. The following takes TianJing in front of the main hall as an example to analyze the rules for scale determination and the regional differences in JiangNan region.

The book YingZaoFaYuan describes the construction methods of SuZhou style dwellings in detail, including a chapter named “Proportion of TianJing”, which describes the rules for determining its scale. The size of the TianJing depends on the size of the hall, while the width is the same as the bay of the hall or the main room minus the depth of the wing rooms. There is a formula in YingZaoFaYuan that specifies the dimensions of TianJing (Yao Citation1986).

The depth of the TianJing in the front of the hall depends on the depth of the room. The back TianJing ends at the boundary wall, and its depth is half that of the room. The TianJing of a multistory building is the same as that of the hall. If the TianJing is between two halls, the depth is based on the main hall behind. In architecture cases, the TianJing’s depth often slightly differs from that of the hall due to the land conditions and use requirements. Generally, the TianJing is smaller than the hall, and the difference is mainly two, four, six, and eight Chi to one Zhang (ten Chi), usually an even number.

The width of the TianJing is also restricted by the size of the hall. YingZaoFaYuan stipulates that the width of the main room in the hall should be double the width of the secondary room. If a house has five rooms, the side room can be the same as the secondary room (Yao Citation1986). Through analyzing Yao ChengZu Drawings in YingZaoFaYuan (), we can determine that the width of TianJing is generally equal to that of the three bays, the main hall minus the depth of the wing rooms and corridors on both sides, or the width plus the width of the left and right rooms based on the main room.

Table 2. TianJing scale statistics from the drawings in YingZaoFaYuan (Chen Citation1979).

The shape of the TianJing has the proportions of a rectangle in terms of its depth-to-width ratio. A folk FengShui book named LiQiTuShuo (Planning Qi Diagram Theory) states that the shape of the TianJing is square, not too long and narrow, like a single oar. The width-to-length ratio of the single paddle in folk rowing is approximately 1:5 ~ 1:4. In traditional JiangNan dwellings, there are few such narrow TianJings, except for the eyebrow TianJing type. Through statistical analysis and conversion of surveying and mapping data, the scale of traditional dwellings in different regions has been restored. The depth-to-width ratio of the front TianJing hall in JiangNan region is mostly concentrated in the range of 1:3 ~ 1:1. Another FengShui book YangZhai JingZhuan (Mansion Classics) states that all houses, both inner and outer halls, take TianJing as the place of fame and wealth. If the width of TianJing is 1 Zhang, a depth of 7 or 5 Chi is appropriate. It is reasonable to be as deep as 6 or 7 Cun to keep it clean. This aspect ratio of 1:2 ~ 2:3 occurs frequently. However, in JiangNan region, the depth-to-width ratio of many dwellings exceeds this range. In addition, the height from the cornice of TianJing to the ground is greater than the plane scale, forming a vertical bucket shape similar to a well.

4.2. Scale and ratio

Although TianJing-style dwellings share the same design principles, they show various architectural forms. This paper seeks to identify the from from the scale, shape, proportion and “Over White” of TianJing. At present, the JiangNan region is usually divided into the large JiangNan and small JiangNan. In a general sense, large JiangNan includes the areas south central to the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, namely, southern JiangSu, ShangHai, ZheJiang, southern AnHui and northern JiangXi provinces. In a narrow sense, JiangNan approximately comprises southern JiangSu to northern ZheJiang. The study samples were taken from a relatively large region for analysis. Considering the continuation of traditional culture, this research selects typical examples well preserved in JiangNan region and that can represent the characteristics of the region for the scale analysis.

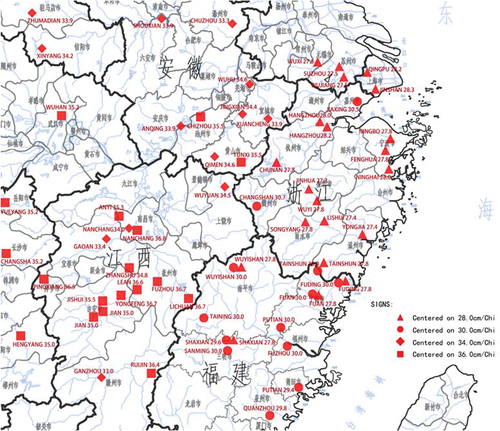

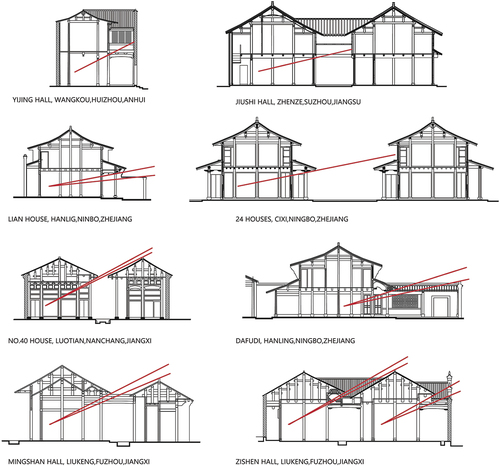

First, we collect the data of typical TianJing scales in different regions for statistics and restore the TianJing scales according to the local dimension standards used in construction in the regions ( and ). Then, the TianJing scale used for building design at that time, as well as the depth-to-width ratio and common size range in various regions, are obtained (). From this, we can identify obvious differences in the shapes and proportions of TianJing in different regions. Through the line-of-sight analysis of the dwelling sections, it is concluded that the Over-White of TianJing is related to the change in its scale in different regions. The statistical results are shown in .

Table 3. List of construction rulers found in the field investigation of JiangNan region11 (Unit: cm).

Table 4. Statistical table of TianJing scale data of some dwellings in JiangNan region.

Table 5. Statistical table of TianJing scale situation in JiangNan region.12

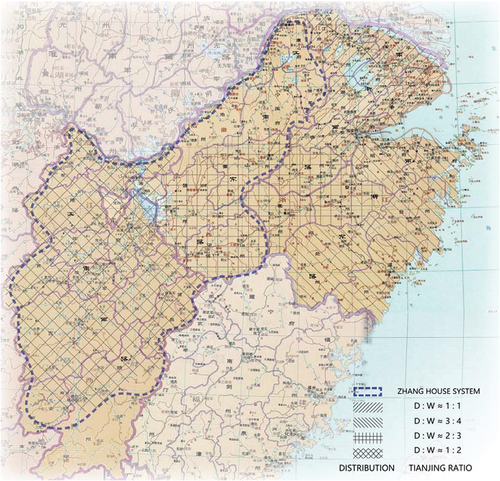

A book of Confucian Classics, LunHeng, it states: the area of house is within a square Zhang. This means that the scale of the TianJing is restricted by the Zhang House Rule. However, although JiangNan TianJing are smaller than the courtyards in the north, they are not completely limited by the rule, according to the statistical sources of surveying data. TianJing, in southern JiangSu, ShangHai and ZheJiang, is generally large in scale, while in other regions, they are mostly within an area of one Zhang. Through data analysis, the numerical characteristic distribution of the depth-to-width ratio of TianJing in JiangNan region is obtained (). As shown in the figure, in FuZhou, HuiZhou and DongYang, the geographically close central areas of the JiangNan region, the ratios are the smallest, ranging from 1:3 to 2:3, and the shape is somewhat narrow and long. Meanwhile, the ratio of the peripheral areas is large, and the TianJing scale tends to be square, in which the scale of the NingBo and ShaoXing area is similar to that of WenZhou and the same as that of HangZhou and SuZhou. The scale span of TianJing in HangZhou covers the proportion in the three surrounding regions, and the forms are relatively diverse. In HuiZhou and ChiZhou, AnHui province, the shapes of TianJing significantly differ, and the proportion is close to DongYang. The depth-to-width ratio in JiangXi is concentrated and the narrowest, with small regional differences.

In GuangDong and FuJian, the design method of Over-White to control the scale of TianJing is a general requirement in residential construction. In the traditional construction of JiangNan region, the practice of Over-White is rare. However, some JiangNan dwellings have unconsciously created the effect of Over-White. For example, our analysis reveals a few Over-White phenomena in DongYang, FuZhou and NanChang. In Ji’An, JiangXi province, due to the long depth of the room, TianJing have gradually evolved into TianMen (Door of Sky) and TianYan (Eye of Sky), with almost no Over-White. In HuiZhou, southern JiangSu, western ZheJiang and other places, it is common to see multistory buildings surrounded by high walls. Although the TianJing size is similar, due to the overall increase in the roof height, they cannot achieve Over-White (). Conversations with local artisans suggest that there is no special Over-White practice in the construction of dwellings in JiangNan region.

The above data reveal the similarities or differences among various TianJing in different regions of JiangNan.The scales of TianJing in JiangXi Province are relatively consistent. HuiZhou is different from ChiZhou; both are in AnHui province but are close to DongYang in ZheJiang. Although ChiZhou is located on the South Bank of the Yangtze River, in the Ming Dynasty, it was subordinate to AnQing Prefecture north of the river, which borders HuiZhou. Eastern ZheJiang is relatively unified but is clearly different from western ZheJiang. It has been divided into East and West administrative regions since ancient times. From SuZhou to HangZhou, TianJing is consistent in scale, which is the standard range of water towns in JiangNan. However, HangZhou is relatively unique. Due to its proximity to NingBo and ShaoXing, its TianJing scale is also similar to the characteristics of those in NingShao.

4.3. Shape and adaptability

The distribution of various types of dwellings has obvious regional characteristics and is affected by geographical conditions and the social environment. The local architectural forms far from the core area show more significant formal changes. Many regions also have characteristics of two or more types, becoming multitype interactive influence zones. This phenomenon is influenced by population migration and cultural exchange. The convenience of transportation and the condition of the environment also determine the degree of interaction of different types.Footnote11

Previous research on northern courtyards found that the size of the yards gradually decreases with climate change from north to south and from cold to hot. For example, the average ratios of yard width to house height in JiLin, BeiJing, JiangSu and FuJian are 15:3, 10:3, 5:3, and 6:5, respectively. In the above areas, the noonday solar altitude angles of the summer solstice are 68°, 73°, 82°, 87°, and the angles of the winter solstice are 22°, 27°, 36°, 41°. From the perspective of architectural physics, northern China needs sunshine in winter. The solar angle is low, and there must be enough space between houses to ensure sufficient sunshine. In the south, the height angle is too large in summer, so sunshade is needed. To prevent too much sunlight, the space between houses must be reduced. From east to west, the terrain changes from low to high, and the courtyard space in traditional dwellings also changes from square to rectangular.

The depth-to-width ratio of the courtyard in JiLin is approximately 2:1, that in Beijing is approximately 1:1, that in Shanxi is 2:1, and that in Shaanxi exceeds 3:1 (). A previous study speculated that the main reason for this change is the northwest wind, which is the dominant wind direction in northern China. Generally, there are strong winds and sandstorms in the western region with a higher altitude, and the dwellings are narrow and long from north to south, which is conducive to diversion of wind and sand.

According to the survey of TianJing dwellings in the south, the scale ratio of TianJing also varies by region. Taking the changes of the TianJing scale in JiangNan as an example, the scale in southern JiangSu, ShangHai and ZheJiang is generally larger, while that in HuiZhou and JiangXi is limited by the Zhang House Rule, and the width is usually less than one Zhang. The shape of TianJing gradually changes from rectangular to square from west to east, forming a quadrate yard instead of a narrow yard. The depth-to-width ratio of TianJing in JiangXi is approximately 2:5, that in HuiZhou is 1:2, and that in SuZhou tends to be 1:1, as shown in the figure (). The appearances of TianJing dwellings vary with traditional construction systems in different regions, and the corresponding scale characteristics adapt to local geographical conditions according to specific rules.

5. Implication of regionality

Through the above analysis, it can be concluded that the distribution of TianJing types differs from the existing administrative divisions but is relatively close to historical administrative divisions. The concept of JiangNan region can be traced back to the pre-Qin period. From the pre-Qin Dynasty to the Sui Dynasty, the Central Plains region was always the geographical center of China. JiangNan often refers to the area south of the Yangtze River, including HuBei, HuNan and JiangXi provinces, which is the scope of ancient JingZhou.

The administrative districts of the Tang Dynasty were divided into the three levels of Dao, Fu, Xian, while the administrative unit JiangNan Dao, named after JiangNan, first appeared. At that time, JiangNan Dao covered most areas south of the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, including JingZhou (southeastern HuBei, HuNan and GuiZhou) and YangZhou (JiangXi, southern AnHui, FuJian, southern JiangSu, ShangHai and ZheJiang). Because of its broad jurisdiction, JiangNan Dao was divided into East JiangNan Dao, West JiangNan Dao and QianZhong Dao in the flourishing Tang Dynasty. GuiZhou, western HuBei and western HuNan under the jurisdiction of QianZhong Dao withdrew from JiangNan area. In the Middle Tang Dynasty, East JiangNan Dao was divided into four Daos: western ZheJiang, eastern ZheJiang, southern AnHui and FuJian. West JiangNan mainly included JiangXi, eastern HuBei and HuNan. In this regard, the scope of the historical JiangNan region was somewhat consistent with the vast JiangNan definition today. In the Song Dynasty, the political and cultural center began to move southward. The JiangNan region include JiangNan West Dao (most of JiangXi and southeast HuBei), JiangNan East Dao (one Fu: JiangNing; seven Zhou: Xuan, Hui, Jiang, Chi, Rao, Xin and TaiPing; two Jun: NanKang and GuangDe), East of ZheJiang Dao (ShaoXing Fu) and West of ZheJiang Dao (Lin’An Fu). This area is still used today and is known as the large JiangNan. In the early Yuan Dynasty, the JiangNan region and its north–south expansion areas were divided into the provinces of HuGuang, JiangXi, JiangHuai and FuJian. In the Ming Dynasty, western ZheJiang was divided into two parts for political reasons. The north was divided into southern ZhiLi (NanJing), and the south was divided into ZheJiang province. In the Qing Dynasty, Southern ZhiLi in the Ming Dynasty was changed to the JiangNan province, which also included northern HuaiAn and JiangSu. Since then, JiangNan province has been divided into JiangSu province and AnHui province. The regional delimitation and administrative unit division for JiangNan region became increasingly blurred (Zhou Citation2007).Footnote12

By using the scope of JiangNan in historical geography to investigate its traditional dwellings, we can more clearly discern the relationships among different types of local residences in different regions (). For example, the TianJing similarity between SuZhou and HangZhou may be attributed to the connecting passage of ancient West ZheJiang Dao, from SuZhou to HangZhou with TaiHu Lake as the center. NingBo and ShaoXing (formerly known as YueZhou), DongYang (formerly known as WuZhou) and WenZhou, all of which belong to the East ZheJiang Dao, have similar scales. In ancient times, administrative divisions were mainly based on the locations of mountains and rivers. Natural and geographical conditions created channels for and obstacles to social and cultural exchanges in various regions.

Figure 27. Schematic diagram of the TianJing scale distribution in JiangNan region based on the historical map of the Southern song dynasty.

The four geographical regions in the Southern Song Dynasty, East and West JiangNan and ZheJiang Dao, converging at HuaiYu Mountain and XianXiaLing Mountain, were separated by mountains, but their terrain was flat when extended outward. The dimensions of TianJing vary greatly among regions, and their scale and shape ratio in mountainous and plain areas differs. However, the TianJing scales are close to the same in adjacent mountain dwellings. Furthermore, although the scales of various types of dwellings in the core region are relatively similar, they still have independent characteristics. In the small JiangNan Region, from NanJing and SuZhou to HangZhou and within the TaiHu Lake Basin, the economy and culture have been closely linked since ancient times, and its architectural form and scale also have similar characteristics that significantly differ from those of other regions. These differences, beyond current administrative districts, coincide with historical divisions influenced by geographical factors.

6. Conclusion

In traditional Chinese dwellings, courtyards and TianJing are the essence of ancient Chinese architecture (Zhang Citation2002). Courtyards, as a form of space, are a universal phenomenon worldwide. From Vitruvius’s Ten Books on Architecture to modernism and postmodernism, there are numerous architectural theories and in-depth discussions of courtyard space. However, TianJing, as a common form of yard in southern China, is a unique feature of Chinese architecture that does not exist abroad. As architecture is the carrier of residential culture, regional differences have frequently been mentioned, but in-depth discussion of TianJing is relatively rare. Especially for the TianJing space prototype and scale standard, a summary of technical rules and rational analysis of data are lacking. This paper takes only the scale of TianJing as an element of architectural cultural geography and analyzes traditional dwellings in various regions in an experimental discussion of the quantitative research of conventional architecture.

The statistical analysis of the data shows that in east and west JiangNan and ZheJiang historically, from the plains to the hills to the mountainous areas, the absolute size of TianJing has gradually decreased, and the plane shape has changed from square to rectangle. This dwelling type crosses the boundaries of current administrative divisions and is affected by multiple factors, such as natural geography, environmental climate, history and culture. Taking technical characteristics as clues, using the methods of data quantification and formal analysis, we deeply tap the cultural genes hidden in vernacular heritage. Historical geography explains the mathematical representation of regional architecture and the folk rules of vernacular construction, which can more intuitively reflect the development, dissemination, influence of and change in construction techniques.

Of course, due to the limited information available and the large number and variety of traditional dwellings, the results of this study cannot be accurately summarized. However, the scale analysis of TianJing has clearly reflected the differences and connections among various construction methods of different traditional residence types under historical administrative changes, which will enlighten the study of traditional architecture technology and typological regional systems.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could appear to influence the work reported in this paper.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This means dangerous terrain in war, such as streams, wells, sinks or gaps in the ground. Sun Tzu’s art of war: marching.

2 “Yue” means moon.

3 A FengShui book by Wu Ding in the Qing Dynasty states: TianJing in the house represents wealth and prosperity. The front of the house symbolizes the mountain. TianJing in a moderate size can gather wealth. The front room should not be high or low, and commensurately the guest and host can then get lucky.

4 A FengShui book from the Tang Dynasty and published in the Qing Dynasty states: TianJing is an important part of a residence related to wealth and prosperity, which must be flat and square, and not too wet or dirty. There are usually two closed passages on both sides of the hall, which can nourish the home. The scale of it is naturally symmetrical and square, which can be comfortable for the family. The position of the gate represents the Vital Qi, meanwhile the TianJing represents the Flourishing Qi. Qi, both Yin and Yang, is compact naturally, and not allowed space directly through. There are lyrics in the folk: the TianJing should be neither high nor deep, neither long nor partial, and then the family can accumulate money and wealth …

5 Another FengShui book by Gao JianNan in the Qing Dynasty states: All imperial houses have inner and outer halls, and TianJing is the ceremonial one in the palace with the wealth and fame.

6 A classic, the Scripture of Ethics,states: Mix clay utensils, because the middle is empty, so we implement effect. Carved doors and windows covering a house, because the middle is empty, have the function of the house.

7 The impluvium is the sunken part of the atrium in a Greek or Roman house (domus). Designed to carry away the rainwater coming through the compluvium of the roof, it is usually made of marble and placed approximately 30 cm below the floor of the atrium. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Impluvium

8 YingZaoFaYuan states: Jian (boundary) sounds the same as Zhan (occupation) in the Wu dialect. This means that land or houses invade those of other people. (Yao Citation1986)

9 A method to deal with the spacing of ancient buildings. It is required to control the distance between the back hall and the front building. So that people sitting in the hall can see the ridge of the front roof through the door jambs. That is a white sky light can be seen between the roof ridge and the door jamb in the shadow. Therefore, it is called “Over-White”.

10 It is like a funnel in the sky.

11 In this table, survey data from the research group were taken from the project group supported by the science foundation in Tongji University. Liu (Citation2019); College of Architecture and Urban Planning TongJi University (Citation2014)

12 In view of the limited cases, scale statistics are approximations after averaging the limited data. The actual size will deviate slightly by time and place.

References

- August, M. 2010. Pompeii: Its Life and Art. translated by Kelswy. New York: General Books LLC.

- Chen, C. Z. 1979. “Yao ChengZu Drawings.” YingZaoFaYuan. Internal Information of Department of Architecture, Tongji University.

- Chen, L. G. 1999. “YingXing WenHua Yu ZhongGuo ChuanTong JianZhu Jing KongJian [Feminine Culture and Jing-Space in Chinese Traditional Architecture].” HuaZhong Architecture 1: 21–28.

- Cheng, J. J. 1991. “On “Door Light Ruler”: A Reply to Mr. H. W. Tang of the UK.” Ancient Architecture and Garden Technology 1: 16–21.

- Cihai Editorial Committee. 1999. “The Chinese Word Dictionary (1999 Edition).” 3310. Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House.

- College of Architecture and Urban Planning TongJi University. 2014. “Atlas of Various Regional Characteristic Residences in Traditional Towns.” National Building Standard Design Atlas, No. 11SJ937-1. China Planning Press.

- Dönmez, M. A. 2021. “Evaluation of Vernacular Architectural Features of Traditional Konya.” Engineering & Architectural Science 2 (A Multidisciplinary Approach). https://www.astanayayinlari.com/engineering-architectural-science2-a-multidiscipliner-approach-ekitap

- Farzaneh, S., S. Mehdi, and M. M. S. Seyed. 2016. “Investigation of Iranian Traditional Courtyard as Passive Cooling Strategy (A Field Study on BS Climate).” International Journal of Sustainable Built Environment 5 (1). doi:10.1016/j.ijsbe.2015.12.001.

- Fu, X. N. 1998. “A Preliminary Study on the Architectural Site of the Western Zhou Dynasty, QiShan FengChu in ShaanXi.” Collection of Essays on Fu Xinian’s Architectural History. Cultural Relics Publishing House.

- Huang, Z. L. 1999. “The Opening and Closing Type TianJing in JiangXi Vernacular Residences.” Architectural Journal 7: 57–59.

- Huang, H. 2008. “JiangXi MinJu [Jiangxi Residence].” China Architecture and Building Press.

- Leonardo, B. 1990. “Die Geschichte der Stadt.” Campus Verlag GmbH.

- Liu, Z. P. 1990. “ZhongGuo JuZhu JianShi [A Brief History of Chinese Residential Architecture].” China Architecture and Building Press.

- Liu, C. 2019. “A Craft Ruler: Investigation into Traditional Architecture Measurement Tools.” Doctoral Dissertation of TongJi University.

- Lu, Y. D. 1995. “ZhongGuo ChuanTong MinJu Yu WenHua [History and Culture of Chinese Residential Architecture].” South China University of Technology Press.

- Lu, Y. D. 2003. “ZhongGuo MinJu JianZhu [Chinese Residential Architecture].” South China University of Technology Press.

- Malcolm, C., and R. Rajan. 2018. “Low Energy Cooling and Ventilation in Indian Residences.” Science and Technology for the Built Environment 24 (8). doi:10.1080/23744731.2018.1522144.

- Peng, D. Q. 1960. “Quan Tang Shi. [Complete Poetry of the Tang].” ZhongHua Book Company. No. 16, 17.

- Sun, W.2001. “SunZi BingFa [Sun Tzu’s Art of War] (During Spring &. Autumn Period).” ZhongHua Book Company.

- Tang, G. Z. 1965. “Quan Song Ci. [Whole Song Ci].” No. 4. ZhongHua Book Company. 3006–3007.

- Vitruvius. 1960. The Ten Books on Architecture. translated by Morris, H. M. New York: Dover Publications.

- Wang, Z. F. 2008. “DongFang ZhuZhai MingZhu [Pearl of Oriental Residence: Folk Houses in DongYang, ZheJiang].” TianJin University Press.

- Yao, C. Z. 1986. “YingZao FaYuan [Original Construction Method].” China Architecture and Building Press.

- Yu, Y. 2001. “ZhongGuo DongNanXi JianZhu LeiXing QuXi YanJiu[Study on Architectural Flora Types of Southeast China].” China Architecture and Building Press.

- Yuno, Y. L. 1975. “Human Engineering of Sumitomo.” Kagoshima Publishing Association.

- Zhang, L. G. 2002. “Jiang Xue Qi Shuo [Seven Comments on Traditional Chinese Architecture].” China Architecture and Building Press. 50.

- Zhou, Z. H. 2007. “Sui WuYa ZhiLu [Follow the Boundless Journey].” SDX Joint Publishing Company.