ABSTRACT

The protection and development of traditional villages have become a pressing issue. This study deconstructed the driving elements of village revitalization into two major systems: the kernel and the regulation system, using the parallelogram law, Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP), and fuzzy membership functions integrated to form the PAF model of traditional village revitalization. The village revitalization can be classified into two types of primary modes and six types of secondary modes: core dominance and regulation dominance. Combining the characteristics of each model and the development status quadrant chart, two village revitalization paths were determined: 1) First, strengthen the core driving force of villages with low development in the third quadrant, promoting their independent development in the fourth quadrant, and optimizing their external development to achieve a state of high-quality development in the first quadrant; 2) optimize the external development environment first, promote third quadrant villages to enter the externally led development state of the second quadrant, and then enhance their competitiveness to reach a better development level in the first quadrant. Finally, it outlines a revitalization path that is consistent with village reality, including the continuation of the traditional style, protection of traditional buildings, and inheritance of excellent culture.

1. Introduction

Traditional Chinese villages are a significant non-renewable cultural heritage site with multiple values. They have a long history of morphological integrity, vernacular architecture (Wang et al. Citation2019), environmental harmony (Weilong, Shi, and Zhou Citation2019), cultural regionalism (Yang, Fang, and Wang Citation2019), and landscape uniqueness (Lei Liu Citation2018). Since 2012, the Ministry of Housing and Construction, in collaboration with several other ministries, has designated 6,819 villages as “Traditional Villages of China.” They are not only the source of agricultural civilization on a global scale and the most concentrated expression of China’s traditional culture, but also enrich cultural connotations, boost cultural confidence, and accelerate national rejuvenation. Along with urbanization, a large number of traditional villages and other historical areas are inevitably confronted with the crises of the survival, adaptation, evolution, transformation, and extinction of traditional culture (Liu, Zhang, and Zhang Citation2015), as well as difficulties such as sharp declines in quantity and quality, loss of characteristics, and hidden security risks(Yuan et al. Citation2018; Chao et al. Citation2020). At present, Chinese traditional villages face many problems, such as the overall quality of human settlements, unbalanced regional development, imperfect basic living facilities, and imperfect management and protection mechanisms. In addition, constructive destruction, ecological environmental pollution, aging of traditional buildings, and functional degradation also appear in the construction process of conservation development (Long et al. Citation2016). At the same time, traditional villages face hollowing problems, such as the abandonment of traditional buildings and the outflow of population (Chunla and Mei Citation2021). In general, traditional villages have fallen into difficulties such as an imbalance of the natural ecological environment, loss of history and culture, and gradual disintegration of traditional social structures. They are constantly disturbed by the external environment and lose their original unique charm. The conservation and development of traditional villages is a critical issue for people from all walks of life, and is a primary focus of current planning research.

The majority of earlier research focused on physical space reconstruction (Xiaoliang et al. Citation2019), traditional architecture restoration, habitat transformation (Wang et al. Citation2016), infrastructure support (Wei et al. Citation2017), industrial development (Tingyun et al. Citation2020), and archival management (Lin et al. Citation2021; Ren and Liu Citation2020). The majority of them focus on the sustainability of traditional village tourism (Hua and Guo Citation2017), and all parties agree that in developing tourism activities, the village’s endowment is the fundamental force, market factors are the decisive force, the government plays a leading role, and other factors, such as transportation and festivals, are facilitating forces (Song and Zhang Citation2019). To solve the many problems faced by traditional villages and achieve the above objectives, earlier studies adopted multidisciplinary integrated models ranging from qualitative to quantitative and then to computer simulation in theory and practice, including value assessment models (Liu et al. Citation2022b; Jing, Jialu, and Yunyuan Citation2020), spatial analysis models (Haoran et al. Citation2022; Leili and Zhang Citation2022), and social network models (Liu et al. Citation2022a; Wei, Wang, and Zhang Citation2021; Zhou and Hou Citation2021). There are better solutions to the specific problems faced by traditional villages, but the existing models mostly start from the single level of the village itself or the region as a whole and thus lack a systematic perspective combining macro and micro.

Huizhou traditional villages are culturally diverse and relatively well-preserved; they exhibit remarkable regional characteristics, a diverse range of intangible cultures, and a high degree of inheritance continuity. The Huizhou traditional village is the area with the largest preserved area, the most complete protection, and deep socio-historical and cultural connotations in China, which has important protection and utilization value and academic research value (Zhao et al. Citation2022; Xiaoliang et al. Citation2019). Numerous current studies of Huizhou traditional villages have focused on their spatial distribution (Jiulin, Chu, and Yao Citation2019), evolution and driving mechanisms (Jiulin et al. Citation2018), distinctive values (Chen and Wang Citation2021), and the holistic relationship between villages and ancient roads (Chu, Yao, and Jiulin Citation2019) . At the mesoscopic level, village planform analysis effectively ensures that village revitalization is spatially and functionally implemented (Chu, Yao, and Jiulin Citation2019). At the micro-level within villages, the identification of landscape genes and their characteristics (Wang Citation2018); the analysis of their physical, cultural, and social spaces; and a summary of the influence mechanisms of social, capital, political forces, and other elements on the spatial structural changes of traditional villages in Huizhou (Zui et al. Citation2021) all contribute to deconstructing villages from a multi-dimensional and holistic perspective, allowing them to propose their development strategies in a targeted manner.

Although existing conservation strategies have yielded positive results, they also have some drawbacks. The primary reason for this is that traditional village revitalization is not driven by a single or a few elements, and the current study lacks a systematic perspective on the impact of multiple elements acting in concert on traditional villages. This study begins with regional cognition and conducts in-depth research on specific villages, intending to broaden perspectives on traditional village transformation and development and to guide sustainable and coordinated village development.

2. Study area and data sources

2.1. Study area

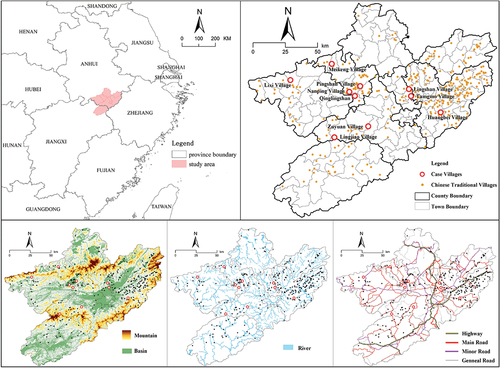

Huizhou is a Chinese administrative jurisdiction that was established during the Ming and Qing dynasties. It includes Huangshan City in Anhui, Jixi County in Xuancheng City in Anhui, and Wuyuan County in Jiangxi. It shares the same scope as the “National Huizhou Cultural and Ecological Protection Zone, ” announced by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism. The entire area is approximately 13,881 km2, and there are 325 traditional villages at the national level, making it a representative area with a greater scale and higher quality than other traditional villages in China.

After a long period of development, Huizhou’s traditional villages developed the spiritual qualities of openness and tolerance, an organizational pattern suited to clan gathering and living, an ideology of Confucian respect, and the socioeconomic state of prosperous commercial activities. The villages are built along the basin and water system, and are mostly located in fertile soil areas that are rich in diverse ecological resources and have a pleasant regional climate, all of which contribute to the prosperity of Huizhou culture. Village protection work in the Huizhou region began earlier and with greater effort, and certain results have thus far been achieved. However, the number of traditional villages is large and they are widely dispersed, and there remain limitations in the protection and development led by the government alone, which makes it difficult to ensure that all villages are effectively protected and also results in some variation in the quality of protection. Specific manifestations of the decline in the quality of material heritage include the absence of cultural heritage, a single village development model, a lack of supporting industrial facilities, and a lack of collaboration between multiple subjects.

In this study, 10 traditional villages, including Lingshan Village and Tangmo Village, were selected as case studies for empirical research ( and ), taking into account the popularity of the villages, honors received, pattern characteristics, historical heritage, and preservation status combined with the actual research and upholding the principles of village representativeness and integrity. These case villages are well preserved and relatively intact. However, they also have many problems associated with revitalization. It is necessary to analyze multiple elements of the villages from a holistic perspective and strive for holistic protection, taking into account the historical lineage, environment, humanities and society, and economic and industrial aspects of the villages. This will broaden the path of transformation and revitalization of traditional villages and guide their sustainable and coordinated development of traditional villages.

Table 1. Basic situation of the village cases.

2.2. Data sources

The research data mostly fall into three categories: (1) vector geographic information data from China’s National Catalogue Service for Geographic Information (https://www.webmap.cn/), including administrative divisions, road data, and water systems. (2) raster data for the research region obtained from the Geospatial Data Cloud Platform (http://www.gscloud.cn/), including DEM and remote sensing image data. (3) Statistical data, such as information on villagers’ income, village population, and ancient village structures, culled from the archival records of each village designated as a national traditional village and maintained by county-level housing and construction departments, some of which have been digitized and archived and are available through the Traditional Chinese Village Digital Museum (http://www.dmctv.cn/).

3. Theoretical basis of the traditional village revitalization system

3.1. The connotations of traditional village revitalization

Revitalization does not mean returning to history, culture, and identity, but has been described as a practice that renews and remakes cultural traditions that are part of social construction (Auclair and Fairclough Citation2015). Revitalization is not only about people, but also about places and entire regions (Jokela and Huhmarniemi Citation2021). Revitalization refers not only to language, arts, crafts, and other cultural practices, but also to places, villages, and whole regions based on their local and regional originality and potential vitality (Huhmarniemi and Jokela Citation2020). Revitalization is a long-term process aimed at rescuing an area in crisis (Konior and Pokojska Citation2020). This change concerns both the material tissue—buildings, public spaces, and green areas—and intangible elements in economic, social, or cultural spheres (Forum Rewitalizacji–Definicje Citation2022). Sustainable revitalization implies self-sustenance, underlined by active, bottom-up community participation, where co-creation collaborations between locals and external parties are commonplace (Klien Citation2010).

To solve the problem of rural decline, the Chinese government put forward and implemented a strategy of rural revitalization in 2017 and formulated the goals of rural revitalization as well as a timetable and road map for achieving these goals (Make a Decisive Decision to Build a Moderately Prosperous Society in All Respects and Win the Great Victory of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in the New Era Citation2017). Rural revitalization is a complex engineering system. Rural revitalization is a process of comprehensive revitalization of the rural population, economy, society, culture, and ecology, using economic, political, cultural, and engineering measures to cope with the loss of factors and functional decline within the rural regional system (Liu Citation2019; Long, Zhang, and Tu Citation2019). Rural revitalization needs to stimulate rural endogenous development power, complement the shortcomings of rural development, and promote the restructuring of rural system elements, structural optimization, functional upgrading, spatial reconstruction, morphological remodeling, and realization of rural transformation and sustainable development (Yansui Liu Citation2018). The rejuvenation of traditional villages refers to the transformation, revitalization, and long-term development of villages, that is, in the modern economic, social, and technological context, villages are transformed and renewed based on the premise of excellent traditional culture inheritance and traditional style continuity, promoting the vitality and vigor of villages, ensuring the inheritance, guardianship, and maintenance of villages, and promoting the traditional culture to keep pace with the times and to bring out new ideas (Yingkui and Binqing Citation2019).

Traditional village revitalization is different from simple inheritance, transforming them into a new cultural form suitable for contemporary development. Creative inheritance and innovative development are combined with contemporary excellent cultural connotations, and are based on integrating fine traditions and maintaining collective memory, continuously enriching cultural contents, refining cultural spirit, blossoming cultural excitement, and enhancing cultural confidence, to strengthen the contemporary competitiveness and cohesion of inherited contents.

3.2 The traditional village revitalization system

Traditional villages evolve as a result of the interaction of a unique natural geographical location with complex cultural and social backgrounds, and have a stable living atmosphere that is markedly different from that of cities on the cultural, economic, and social levels. Village residents and groups from outside the village, such as the government and businesses, contribute significantly to the village’s evolution by providing labor, guiding resource allocation, and forming economic organizations that generate village development drivers in terms of population, industry, and supporting facilities. The regional environment in which villages are located supplies raw materials for development and has an impact on their construction, development, and evolution. Human activities have created a large number of production and living spaces during village evolution, including dwellings, streets, farmland, fish ponds, and other artificially constructed areas. These spaces serve as production and competition bases for village development as well as spatial carriers for other factors that drive the role. While production generates material resources, diverse traditional village cultural systems, such as architectural and institutional cultures, are subsequently developed, bridging disparate development resources and facilitating the accumulation of driving forces.

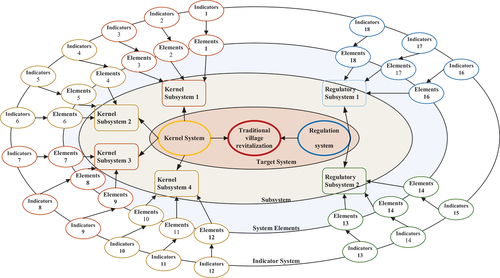

Based on our understanding of the formation and development of traditional villages, it can be concluded that the revitalization system of traditional villages is a collection of internal and external elements with regional characteristics that formed under specific natural, geographical, human, and social conditions and exhibit characteristics such as complexity, openness, and self-organization. Thus, the traditional village rejuvenation system may be deconstructed into a kernel system and a regulation system, each of which is composed of multiple subsystems and elements and defined by a unique indicator ().

4. Research design

4.1. The PAF model of traditional village revitalization dynamics

The idea of constructing a “Parallelogram law—AHP—Fuzzy membership function integrated model” (PAF model) was first proposed by Fang (2011) (Fenglin, Fang, and Zhao Citation2011), which is improved and used in this paper for the relevant traditional village revitalization dynamics, with the following specific ideas.

(1) Parallelogram law

For traditional villages, the elements of the kernel system promote natural revitalization. However, there were some discrepancies in the magnitudes of the forces generated by the interaction of the elements. Positive promotion or restrictive limitations may be the driving force of the regulatory system. As a result, the direction and magnitude of the forces created by various regulatory system elements vary.

The combined force of kernel dynamics (FI) and regulation dynamics (FE) is the system dynamics (F) of traditional village revitalization. The three are distinguished by their direction and magnitude, which corresponds to the physical idea of the vector, that is, the ability to perform parallelogram-law calculations. There are countless possibilities for the magnitude and direction of the kernel and regulation dynamics and the way they combine, but they can be summarized under four conventional phenomena (; ). When the traditional villages under study appear to be non-conventional, as mentioned above, special studies are required to provide special explanations. Additionally, because the elements developed in this study do not include negative indications, modes III and IV were employed merely as theoretical assumptions to ensure that the analysis was thorough.

Table 2. Dynamic analysis of the revitalization system.

(2) Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)

The primary purpose of AHP is to assess the relative importance of each level’s elements, break down their weights, and compute the amount and direction of each element’s force. Because AHP evaluation participants differ in terms of educational background and logic of thought, the results of AHP are subject to some arbitrariness. To address this issue, it is necessary to calculate the weights assigned to each element by averaging the ratings assigned by specialists in various research fields. Additionally, all the element indicators used in this study have positive impacts and are located in quadrant I defined by the positive x- and y-axes. As a result, the size of the element weights can reflect the element’s effect on village growth, as indicated by the angle formed by the force’s direction and quadrant. That is, the deviation of the element’s force from the positive x-axis direction can be estimated using the weight value as α = (1-weight) 90°. By layering the subsystem force, the first-level system force, target force, and angle between the positive direction of the x-axis, the subsystem force, first-level system force, target force, and angle between the positive direction of the x-axis can be determined.

(3) Fuzzy membership function

Because the content of each indication in the system varies and the scale is not uniform, making direct calculation and comparison impossible, the original data must be normalized. Considering only the positive indicators in the index system of this study, the half-ascending trapezoidal fuzzy affiliation function model is used (Fang Citation2000). The half-decreasing trapezoidal fuzzy affiliation function should be used when there are negative indicators among the indicators. The affiliation value of the traditional village element index ranges from 0 to 1, and the higher the value, the greater the index’s contribution to the overall aim. The difference between the affiliation value and 1 represents the index’s gap from the largest index.

4.2. Indicator system construction

Based on the principles of wholeness, feasibility, comparability, and quantifiability referring to the relevant index system of traditional village evaluation in previous studies (Zou et al. Citation2018; Yang et al. Citation2018; Lin et al. Citation2015; Shao and Fu Citation2012), and considering the actuality of Huizhou, 22 indicators were selected to establish the index system of the traditional village revitalization system (). The traditional village revitalization system indicator system has four layers (target, first-level system, subsystem, and indicator layers). The target and the first-level system layers illustrate the strength of the power of the traditional village revitalization system, both internally and externally. The subsystem is the criterion layer, covering six dimensions: the physical environment, folk culture, socio-demography, industrial economics, topographic location, and infrastructural support, showing the level of revitalization drivers in each dimension. The fourth layer is an indicator layer that consists of a series of specific indicators, each of which is described below.

Table 3. Dynamic index system of the traditional village revitalization system.

4.2.1. Kernel system

The kernel system comprises the basic elements that support and contribute significantly to the development of traditional villages. Traditional villages are predominantly located in stable economic communities, and the kernel system is rather stable, with the driving force emanating from the inside and bottom. The kernel system can be disassembled into four subsystems based on the perception of village development elements: the physical environment, folk culture, socio-demography, and industrial economics.

In Huizhou’s traditional villages, the physical environment subsystem includes numerous ancient roads, streets, buildings, and other materials. These material remains can have a distinct value in the transformation of villages, attracting a large number of tourists and promoting vitality regeneration in traditional villages. This research chooses the number of ancient roads, historic environment elements, historical streets and alleys, percentage of historic buildings, and quality of heritage protection to evaluate the physical environment.

The folk culture subsystem encompasses Confucianism, Huizhou merchant culture, clan culture, geomancy culture, and many traditional folk traditions and beliefs, all of which have affected the evolution of villages. The study selected the village formation period, intangible cultural heritage richness, scarcity of intangible cultural heritage, genealogy, and village history as indicators to evaluate the folk culture of traditional villages.

The sociodemographic subsystem refers to the institutions and individuals involved in revitalizing traditional villages, primarily villagers, government agencies, businesses, research institutes, and other village actors. Players can collect external resources following market conditions, government policies, and their requirements, alter the allocation of village resources at the appropriate time, and function as the driving force for village growth. It includes four indicators: percentage of the resident population, population density, scale of construction land, and cultivated land area.

The industrial economy subsystem refers to the state of an industry’s type, structure, base, and other village features. The majority of villages in China are agricultural, yet the economic value provided by conventional agriculture is increasingly insufficient to meet development needs. Through appropriate development strategies, the traditional villages in Huizhou, with their rich cultural history, good natural circumstances, and distinctive resource characteristics, can support rural industry upgrading, village income, village transformation, and rejuvenation. Therefore, this study chose village collective income, per capita net income of villagers, and major industry categories to evaluate the drivers of the industrial economics subsystem.

4.2.2 Regulation system

The regulation system is composed of external components that do not directly contribute to the village’s transformational growth, but can either support or impede it. Adjustable properties of external factors are critical in guiding revitalization and cannot be overlooked. In this study, the modulation system is divided into two subsystems: topographic location and infrastructural support.

The topographic location subsystem is the external natural condition of village revitalization, mainly referring to natural conditions such as elevation, slope, water system, and other elements such as transportation location. For example, Huizhou has remained relatively isolated since ancient times, but to conduct exchange and trade activities with the outside world, a large number of ancient roads and waterways were opened under the leadership of the government and gentry, with the cooperation of numerous parties, and a more comprehensive transportation system was formed during the Ming and Qing dynasties that improved Huizhou’s link to the outside world, boosted the income of Huizhou merchants, and even provided the Huizhou people with a significant supply of rice, salt, and other necessities, which aided the growth of villages.

The infrastructural support subsystem refers to the external socioeconomic factors that influence village revitalization. It primarily refers to infrastructure and public service facilities built by government departments and market institutions in villages. The government directs village revitalization primarily through policy guidance, direct financial investment, and other mechanisms. These amenities include but are not limited to education, sports, health, water, power, communication, and disaster avoidance. The influence of these amenities on villages is primarily in terms of laying the groundwork for industrial development and improving the villagers’ quality of life.

The driving force behind traditional village rejuvenation is the sum of the driving forces generated by the aggregation of diverse system elements, which continuously generate the driving force of village development and act on the village. The composition and functional combination of various elements results in various expressions of driving power and driving effects from various angles. The collaboration of elements, both inside and outside the system, fosters village growth and results in a more diverse driving pattern.

5. Analysis of results

5.1. Driving force solution and revitalization model delineation

Based on the PAF model, the magnitude and direction of each indicator force were obtained, and the parallelogram law was used to determine the force of subsystem Im. Similarly, the FI generated by kernel system I and the FE generated by regulation system E are calculated to determine the comprehensive power F (). The driving forces at each level reflect the current development status and main driving, the magnitude and direction of each indicator force are determined using the PAF model, and the parallelogram law is applied to determine the force of subsystem Im. Similarly, the FI created by kernel system I and the FE generated by regulation system E were computed sequentially to calculate the system dynamics F (). The driving factors at each level reflect traditional villages’ current development conditions and primary driving aspects, into which the revival model of traditional villages can be separated. The first-level mode is governed by the first-level system in the traditional village revitalization system. When the FI of the inner kernel dynamics is greater than the FE of the regulation dynamics, it is a kernel-system-dominated type; otherwise, it is a regulation-system-dominated type. Subsystem determines the second-level model. The largest fractional force element defines the type of secondary mode in the kernel-dominated type, and the same is true for secondary mode discrimination in the regulation-dominated type ().

Table 4. Calculation results of driving forces of villages.

Table 5. The division of traditional village revitalization modes based on system dynamics.

While the exterior environments in which traditional villages in Huizhou are located are relatively similar, there are some distinctions in the roles of the driving elements, which present different driving forces. The solution of the driving forces reveals that FI > FE for Zuyuan, Ping Shan, and Meikeng Villages, whose primary mode is kernel-driven, and FI3 is stronger than FI1,FI2, and FI4 in the composition of FI, implying that their secondary mode is folk-culture-driven. The subsystems that correspond to the primary and secondary modes are necessary for the village to maintain a competitive edge in the region and thus serve as the key and core of village rejuvenation. Lingshan and Huangbei Villages have the highest village dynamics in terms of population density and resident population, and their highly dynamic subjects can play a significant role in village regeneration. According to the solution for their driving force, Lingshan and Huangbei are also villages with socio-demography-driven development. By combining the village resource background of tea, Moso bamboo, and edible mushrooms, Lixi Village and Qingling Mountain have developed rural tourism. Their industrial development has obvious advantages over other village resources, and FI4 constitutes the primary component of the driving force of village development, demonstrating industrial-economics-driven development.

We find FI < FE for Lingkou Village, Tangmo Village, and Nanping Village, whose primary mode is regulation-system-driven, whereas FE1 > FE2 of Lingkou Village indicates a topographic-location-driven mode. Tangmo and Ping Shan are different in that they are not only listed in the national traditional village list but have also been evaluated as national historical and cultural villages earlier, causing them to receive wide attention from all walks of life; various resources have been gathered in the villages that play an important role in the protection and transformation of the villages. The development trend was dominated by the support systems.

5.2 Study of the revitalization path of traditional villages

5.2.1 The path of traditional village revitalization

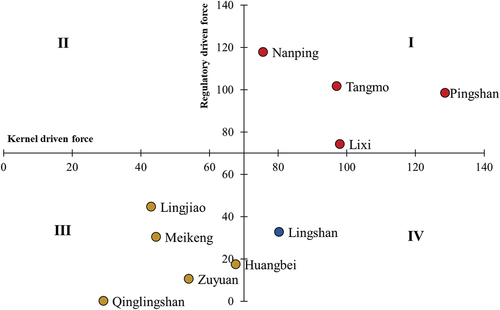

Based on the analysis of village revitalization dynamics and the division of models, the kernel dynamics and regulation dynamics were taken as the x- and y-axes, respectively, and a quadrant diagram of village revitalization dynamics was constructed (). The quadrant diagram helps analyze the advantages and disadvantages of the development of each village to propose revitalization paths in a targeted manner.

Villages in quadrant I have a strong resource base and convenient transportation, developed earlier in the region, and are well connected to the outside world. Villages in quadrant II possess a variety of resources necessary for the growth of the traditional small-farmer economy, but these resources are insufficient for contemporary economic development, and the villages rely heavily on external influences to promote development. Villages in quadrant III lack considerable resources, are inconveniently placed within the region, and receive less support from policies and market forces. They must break through their current state of development. Villages in quadrant IV enjoy favorable conditions and a high level of motivation for development, and inhabitants and other village owners can initiate new revitalization pathways.

As shown in , the villages of Nanping, Tangmo, Ping Shan, and Lixi are located in quadrant I, where they all exhibit strong internal and regulatory system dynamics and a positive development tendency. The future revitalization path is mostly determined by present development resources to further improve the quality and efficiency of development.

Lingshan Village is mostly driven by the kernel system and is located in Quadrant IV. This study’s empirical cases do not include villages located in quadrant II, which are primarily driven by the regulatory system. Villages in quadrants II and IV are developing at an average rate and have their development emphasis, but they are not strong enough. The future revitalization paths of these two types of villages are relatively clear, centered on the concept of “consolidating strengths, filling shortcomings, and strengthening weaknesses” to make the transition from quadrants II and IV to quadrant I and achieve a relatively balanced and healthy state of development.

The kernel and regulation system dynamics of Lingjiao, Meikeng, Huangbei, Zuyuan, and Qinglingshan Villages are relatively low, and their development status is in quadrant III. Their revitalization paths can be roughly classified into two types based on the four-quadrant diagram: III → IV → I, which primarily holds for villages with limited natural resources that require external assistance to initiate the development and guide the excavation of village resources and reproduction of traditional style to achieve a higher development status. The second path is III → II → I, which is primarily geared toward villages with superior resources of their own, who occupy a certain advantageous position in regional competition, who can develop as a result of their circumstances, and who, with the assistance of the external environment, can achieve high-quality and rapid transformation development.

5.2.2 Revitalization strategy based on pattern division

(1) Kernel-system-driven

Kernel-system-driven villages demonstrate that their development is constrained by external factors; therefore, in addition to strengthening existing driving points, we must pay attention to the external environment, increase support, and promote the coordination of internal and external driving factors.

Physical-environment-driven villages must begin by assessing the spatial inheritance value of the physical cultural heritage environment and quantifying its multi-dimensional historical, artistic, scientific, and social values. By embracing the concept of holistic preservation, the village and its significant aesthetic and cultural linkages are classified as protected areas to preserve the traditional style and appearance of the village. By restoring the traditional spatial texture, we learn from village wisdom, organically integrate the artificial environment of traditional villages with the natural environment, enrich landscape levels, meet the material and cultural needs of modern life, and reconstruct contemporary places of interaction. Additionally, the village’s material environment should be guided by fundamental analysis, the introduction of diverse functional businesses, and the discovery of the path of modern functions implanted in the traditional area.

To develop folk culture-driven villages, the idea is to protect cultural heritage and stimulate internal vitality. First, we must retrace our collective memories and decipher the historical ancestors of our culture. Each traditional village has its own development process and a distinct memory. Village memory serves as a testament to history and contributes to the cultural allures of traditional communities. We must tap into the collective memory of traditional villages, analyze their cultural connotations, restore outstanding traditional folk customs throughout history, inherit village rituals, establish archives of intangible cultural heritage, strengthen the intangible cultural heritage discipline system, and conduct activities such as folk art exchanges to promote cultural prosperity and confidence. Under the objective facts of current society, a close dialogue between inheritors, villagers, specialists, and scholars is conducted to breathe fresh life into the intangible cultural property.

Numerous villages today follow a socio-demographic-driven development model, and these villages demand a new development concept based on intensive economic growth, as well as shared governance and cooperation. Villagers, as the primary consumers of villages, are also the inheritors and creators of village culture, and are the driving force behind traditional villages’ “revival” and “existence.” It is critical for village rejuvenation that residents develop a conservation mindset, and that their lives and traditional social networks remain stable. Within the context of new urbanization, efforts should be made to encourage the urbanization of traditional villages on a local level, achieve “urban-rural integration,” and mitigate village population loss, as well as increasing the quality of village infrastructure and public services to enhance the village’s appeal. The government should encourage village residents to form connections with businesses, research institutes, and social organizations, and to integrate resources, attract talent, secure technical and financial support, and establish efficient external relations.

For villages with a strong industrial basis, we should expedite industrial upgrading and foster regional synergy. Huizhou’s mountainous terrain, low agricultural yield, high labor costs, and limited arable land make large-scale agriculture difficult to develop. However, with the area’s stunning natural scenery and a favorable environmental backdrop, it is feasible to manufacture refined high-end agricultural goods primarily through organic agriculture and foster the sustainable growth of farming cultures through distinctive ecological agriculture. Using a network platform and big data, we can address the problem of selling agricultural products based on “Agriculture Plus.” Additionally, based on the characteristics of villages, we should promote industrial restructuring through small-scale and gradual housing reconstruction and moderate business introduction, as well as develop industries such as cultural and creative product manufacturing and rural ecological tourism for villages in need. That is, from a regional perspective, efforts should be made to establish a regional industrial network and rationally organize regional industrial collaboration and labor division following each village’s distinctive value characteristics, geographical position, and transportation conditions.

(2) Regulation-system-driven

Compared to kernel-driven villages, regulation-driven villages must increase their value and competitiveness by incorporating local conditions and circumstances while preserving their current advantages.

Topographic-location-driven villages are influenced by the geographic environment in the construction process, and it is especially necessary to uphold the principle of respecting the external environment in development and reshaping the internal order according to local conditions. Efforts should be made to utilize the natural foundation to the fullest extent possible, ensure the efficient management of natural resource assets, and coordinate the development of “mountains, water, forests, fields, lakes, and grasslands,” as well as charming cities and towns. To create a regional pattern of ecological security, we prioritize the protection of natural ecological elements, such as mountains and hills, mountain basins, river valley fields, and river systems upon which traditional communities are built. Simultaneously, this type of village requires the establishment of a system platform capable of collecting and organizing data and information, as well as dynamic monitoring, evaluation, and early warning to accurately reflect the current state of the regional ecology and potential problems, enhance the ability of various departments to anticipate and control various risks, and serve as a foundation for developing key strategies, improving measures, and allocating resources.

Because infrastructure-driven villages with diverse forms of development and resource advantages are not obvious and require the participation of external forces, it is necessary to accelerate infrastructure development, increase policy protection, and moderately guide the movement of social forces. Diverse development policies should be developed for villages located in different areas and at various stages of development, and effective policy implementation mechanisms should be implemented. Simultaneously, it is necessary to promote investment diversification and build a system of government leadership, market operations, and social engagement. We should build a composite transportation model based on high-speed rail and high-speed networks to promote the free flow and equal exchange of urban and rural factors, as well as to increase the efficiency of factor usage and economic and social operations. For facilities in certain sectors that cannot meet national standards objectively, new technology, materials, and procedures and non-standard diagram design methods should be actively implemented throughout construction to meet safety and industry management needs. Infrastructure settings should avoid locations of concentrated historical and cultural treasures, and consider the compatibility of appearance with the surrounding environment.

6. Conclusion and discussion

This paper examines the driving force behind village revitalization in terms of inheritance and development, and deconstructs the conventional village rejuvenation system as a kernel and regulation structure. The parallelogram law, hierarchical analysis, and fuzzy membership were integrated to create the PAF model of traditional village revival. The following findings were obtained from an empirical examination of the case villages.

(1) The PAF integrated model of traditional village revitalization applies to the analysis of multiple identical objects in the region. It is capable of comparing the magnitude of various elements’ roles within and outside the system via model index calculation, determining the driving force behind village development, identifying the benefits and drawbacks of the development process, and precisely determining the revitalization path and strategy.

(2) According to the results of the PAF integrated model, village development can be classified into two primary modes, kernel-driven and regulation-driven, and six secondary modes, physical-environment-driven, folk-culture-driven, socio-demographic-driven, industrial-economy-driven, topographic-location-driven, and support-system-driven. Additionally, a quadrant map is created based on each village’s revitalization drivers, which can help define the method of village revival. The initial phase is to begin in “poorly developed quadrant III,” and then progress to “strong-core weakly-regulated quadrant IV” or “weak-core strongly-controlled quadrant II.” Finally, the third phase is to enter “quadrant I of high-quality development.”

(3) Combining the revitalization path of villages and the characteristics of each model, this study concludes that the revitalization of traditional villages needs to first, continue the traditional style; second, focus on the protection of traditional architecture; third, improve the living environment as a practical means; and finally achieve the goal of inheriting excellent culture. In the actual work for specific villages, it is also necessary to conduct an analysis of the individual villages and the region as a whole to formulate a revitalization path that is consistent with the actual situation of the villages.

As the index of a single traditional village element is an absolute value, a separate case study is not appropriate for the PAF model. Additionally, this study was subject to previous investigations, as it did not undertake a systematic study and analysis of all the region’s traditional villages. Future research should bolster these efforts, broaden the scope of the investigation, and enhance the accuracy of PAF model computation and other parts of exploration.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The research data mostly fall into three categories: (1) vector geographic information data from China’s National Catalogue Service for Geographic Information (https://www.webmap.cn/), including administrative divisions, road data, and water systems. (2) raster data for the research region obtained from the Geospatial Data Cloud Platform (http://www.gscloud.cn/), including DEM and remote sensing image data. (3) Statistical data, such as information on villagers’ income, village population, and ancient village structures, culled from the archival records of each village designated as a national traditional village and maintained by county-level housing and construction departments, some of which have been digitized and archived and are available through the Traditional Chinese Village Digital Museum (http://www.dmctv.cn/).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Auclair, E., and G. Fairclough. 2015. “Living Between Past and Future. An Introduction to Heritage and Cultural Sustainability.” In Theory and Practice in Heritage and Sustainability. Between Past and Future, edited by E. Auclair and G. Fairclough, 1–22. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

- Chao, W., M. Chen, L. Zhou, X. Liang, and W. Wang. 2020. “Identifying the Spatiotemporal Patterns of Traditional Villages in China: A Multiscale Perspective.” Land 9 (11): 449. doi:10.3390/land9110449.

- Chen, X., and X. Wang. 2021. “Research on the Characteristic Value and Protection and Development of Huizhou Traditional Villages: A Review.” Journal of Chizhou University 35 (1): 69–75. in Chinese. doi:10.13420/j.cnki.jczu.2021.01.021.

- Chunla, L., and X. Mei. 2021. “Characteristics and Influencing Factors on the Hollowing of Traditional Villages—Taking 2645 Villages from the Chinese Traditional Village Catalogue (Batch 5) as an Example.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (23): 12759. doi:10.3390/ijerph182312759.

- Chu, J., L. Yao, and L. Jiulin. 2019. “Present Characteristics and Protection Path of Linear Cultural Heritage Based on “Patch-Corridor-Matrix”: A Case of Huizhou Ancient Road.” Development of Small Cities & Towns 37 (12): 46–52+60. in Chinese. doi:10.3969/j.1009-1483.2019.12.008.

- Fang, C. 2000. “Regional Development Planning.” Beijing:Science Press: P87–88. (in Chinese). http://ir.igsnrr.ac.cn/handle/311030/4804

- Fenglin, W., C. Fang, and Y. Zhao. 2011. “PAF Model of Study on Urban Industrial Agglomeration Dynamic Mechanism and Patterns.” Geographical Research 30 (1): 71–82. in Chinese.

- Forum Rewitalizacji–Definicje. 2022.Accessed 18 December 2022. www.forumrewitalizacji.pl/artykuly/15/38/Rewitalizacja-podstawowe-pojecia

- Haoran, S., Y. Wang, Z. Zhang, and W. Dong. 2022. “Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Traditional Village Distribution in China.” Land 11: 1631. doi:10.3390/land11101631.

- Hua, L., and Y. Guo. 2017. “Research on the Protection and Tourism Development Strategy of the Traditional Village.” Agro Food Industry Hi-Tech 28 (1): 1127–1131. https://www.teknoscienze.com/tks_issue/vol_281/

- Huhmarniemi, M., and T. Jokela. 2020. “Arctic Arts with Pride: Discourses on Arctic Arts, Culture and Sustainability.” Sustainability 12 (2): 604. doi:10.3390/su12020604.

- Jing, F., Z. Jialu, and D. Yunyuan. 2020. “Heritage Values of Ancient Vernacular Residences in Traditional Villages in Western Hunan, China: Spatial Patterns and Influencing Factors.” Building and Environment 188: 107473. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107473.

- Jiulin, L., J. Chu, Y. Jiajue, H. Liu, and J. Zhang. 2018. “Spatial Evolutionary Characteristics and Driving Mechanism of Traditional Villages in Ancient Huizhou.” Economic Geography 38 (12): 153–165. in Chinese. doi:10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2018.12.020.

- Jiulin, L., J. Chu, and L. Yao. 2019. “Research on the Spatial Distribution Pattern and Protection and Development of Ancient Huizhou Traditional Village.” Chinese Journal of Agricultural Resources and Regional Planning 40 (10): 101–109. in Chinese. doi:10.7621/cjarrp.1005-9121.20191013.

- Jokela, T., and M. Huhmarniemi. 2021. “Stories Transmitted Through Art for The Revitalization and Decolonization of The Arctic.” In Stories of Change and Sustainability in the Arctic Regions: The Interdependence of Local and Global, edited by R. Sørly, T. Ghaye, and B. Kårtveit, 57–71, London: Routledge.

- Klien, S. 2010. “Contemporary Art and Regional Revitalisation: Selected Artworks in the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial 2000–6.” Japan Forum 22 (3–4): 513–543. doi:10.1080/09555803.2010.533641.

- Konior, A., and W. Pokojska. 2020. “Management of Postindustrial Heritage in Urban Revitalization Processes.” Sustainability 12 (12): 5034. doi:10.3390/su12125034.

- Leili, L., and J. Zhang. 2022. “Image Simulation of Traditional Village Spatial Layout Based on Computer Numerical Analysis.” Mobile Information Systems 5873846: 1–7. doi:10.1155/2022/5873846.

- Lin, M., J. Jian, Y. Hu, Y. Zeng, and M. Lin. 2021. “Research on the Spatial Pattern and Influence Mechanism of Industrial Transformation and Development of Traditional Villages.” Sustainability 13 (16): 8898. doi:10.3390/su13168898.

- Lin, Z., T. Ma, J. Chang, and Y. Yu. 2015. “Research on Evaluation System of Infrastructure Coordinated Development in Traditional Villages.” Industrial Construction 45 (10): 53–60. (in Chinese). doi:10.13204/j.gyjz201510010.

- Liu, L. 2018. “Prototype Identification for Traditional Villages Landscape Texture and Application: Take West River Dawan Village of Xinxian County, Henan Province as An Example.” Areal Research and Development 37 (2): 163–166. in Chinese. doi:10.3969/j.1003-2363.2018.02.030.

- Liu, Y. 2018. “Introduction to Land Use and Rural Sustainability in China.” Land Use Policy 74: 1–4. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.01.032.

- Liu, Y. 2019. “Research on the Geography of Rural Revitalization in the New Era.” Geographical Research 38 (3): 461–466. doi:10.11821/dlyj020190133.

- Liu, X., Y. Huang, H. Xiang, C. Zhang, J. Chen, and D. Xiao. 2022b. “Optimization Strategies for the Management Mechanisms of Conservation and Utilization in Traditional Chinese Villages Based on Relevance Analyses of Performance Evaluation.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 1–15. doi:10.1080/13467581.2022.2097243.

- Liu, C., Y. Qin, Y. Wang, Y. Yue, and L. Guanghui. 2022a. “Spatio-Temporal Distribution of Tourism Flows and Network Analysis of Traditional Villages in Western Hunan.” Sustainability 14: 7943. doi:10.3390/su14137943.

- Liu, L., C. Zhang, and Q. Zhang. 2015. “The Repairation of Landscape Texture of Traditional Historical and Cultural Town: Take Old Street and White Tang Street as an Example in Shenhou.” Areal Research and Development 34 (6): 76–81. in Chinese. doi:10.3969/j.1003-2363.2015.06.014.

- Long, H., T. Shuangshuang, G. Dahuan, L. Tingting, and Y. Liu. 2016. “The Allocation and Management of Critical Resources in Rural China Under Restructuring: Problems and Prospects.” Journal of Rural Studies 47: 392–412. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.03.011.

- Long, H., Y. Zhang, and S. Tu. 2019. “Tu Rural vitalization in China: A Perspective of Land Consolidation.” Journal of Geographical Sciences 29 (4): 517–530. doi:10.1007/s11442-019-1599-9.

- Make a Decisive Decision to Build a Moderately Prosperous Society in All Respects and Win the Great Victory of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in the New Era. 2017. Accessed 18 December 2022. http://www.gov.cn/zhuanti/2017-10/27/content_5234876.htm

- Ren, Y., and S. Liu. 2020. “Construction of the Archiving Protection Model of Traditional Village Culture Based on GIS.” Archives Science Study 4: 69–74. in Chinese. doi:10.16065/j.cnki.1002-1620.2020.04.010.

- Shao, Y., and J. Fu. 2012. “Research on Value-Based Integrated Evaluation Framework of Historical and Cultural Towns and Villages in China.” City Planning Review 36 (2): 82–88. (in Chinese).

- Song, L., and X. Zhang. 2019. “Temporal-Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Impact Factors of Traditional Villages in Huizhou Area.” Economic Geography 39 (12): 204–211. in Chinese. doi:10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2019.12.023.

- Tingyun, L., Q. Luo, J. Zhang, and Y. Cheng. 2020. “Research on Development of New Business forms for Traditional Villages in Northern Hainan Volcano Area Based on the Grounded Theory: Taking Meixiao Village in Haikou as a Case.” Journal of Natural Resources 35 (9): 2079–2091. in Chinese. doi:10.31497/zrzyxb.20200904.

- Wang, Y. 2018. “Study on the Graphic Form of Huizhou Ancient Villages from the Perspective of Flood Control.” Jianghuai Tribune 1: 155–160. in Chinese. doi:10.3969/j.1001-862X.2018.01.026.

- Wang, C., B. Huang, C. Deng, W. Wan, L. Zhang, Z. Fei, and L. Hao. 2016. “Rural Settlement Restructuring Based on Analysis of the Peasant Household Symbiotic System at Village Level: A Case Study of Fengsi Village in Chongqing, China.” Journal of Rural Studies 47 (Part B): 485–495. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.07.002.

- Wang, D., L. Qingyue, W. Yongfa, and Z. Fan. 2019. “The Characteristic of Regional Differentiation and Impact Mechanism of Architecture Style of Traditional Residence.” Journal of Natural Resources 34 (9): 1864–1885. in Chinese. doi:10.31497/zrzyxb.20190906.

- Weilong, W., Y. Shi, and B. Zhou. 2019. “Evaluation of Human Settlement Environment of Traditional Villages Based on the System Theory of Human Settlement Environment——A Case Study of 18 Villages in Lichuan City of Hubei Province.” Journal Of HuBei Minzu University(Natural Science Edition) 37 (3): 353–360. in Chinese. doi:10.13501/j.cnki.42-1569/n.2019.09.025.

- Wei, C., K. Miao, D. Xiao, and L. Wang. 2017. “Characteristic Division and Protection Thinking in Infrastructure of Chinese Traditional Village.” Modern Urban Research 11: 2–9. in Chinese. doi:10.3969/j.1009-6000.2017.11.001.

- Wei, D., Z. Wang, and B. Zhang. 2021. “Traditional Village Landscape Integration Based on Social Network Analysis: A Case Study of the Yuan River Basin in South-Western China.” Sustainability 13: 13319. doi:10.3390/su132313319.

- Xiaoliang, H., L. Hongbo, X. Zhang, X. Chen, and Y. Yuan. 2019. “Multi-Dimensionality and the Totality of Rural Spatial Restructuring from the Perspective of the Rural Space System: A Case Study of Traditional Villages in the Ancient Huizhou Region, China.” Habitat International 94: 102062. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.102062.

- Yang, X., C. Fang, and Y. Wang. 2019. “Construction of Gene Information Chain and Automatic Identification Model of Traditional Village Landscape: Taking Shaanxi province as an example.” Geographical Research 38 (6): 1378–1388. in Chinese. doi:10.11821/dlyj020181136.

- Yang, L., H. Long, P. Liu, and X. Liu. 2018. “The Protection and its Evaluation System of Traditional Village: A Case Study of Traditional Village in Hunan Province.” Human Geography 33 (3): 121–128+151. in Chinese. doi:10.13959/j.1003-2398.2018.03.015.

- Yingkui, S., and Z. Binqing. 2019. “Evolution and Pathology of Traditional Villages in Southern Xinjiang Based on Human Settlement Theory.” Architectural Journal S1: 47–52. in Chinese.

- Yuan, C., H. Yaping, Y. Feng, and P. Wang. 2018. “Fire Hazards in Heritage Villages: A Case Study on Dangjia Village in China.” International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 28: 748–757. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.02.002.

- Zhao, M., J. Liang, L. Shanquan, and Z. Kaifa. 2022. “Cultural Connotation and Image Dissemination of Ancient Villages under the Environment of Ecological Civilization: A Case Study of Huizhou Ancient Villages.” Journal of environmental and public health 2022: 7401144. doi:10.1155/2022/7401144.

- Zhou, J., and Q. Hou. 2021. “Resilience Assessment and Planning of Suburban Rural Settlements Based on Complex Network.” Sustainable Production and Consumption 28: 1645–1662. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2021.09.005.

- Zou, J., Y. Liu, F. Tan, and P. Liu. 2018. “Landscape Vulnerability and Quantitative Evaluation of Traditional Villages:A Case Study of Xintian County, Hunan Province.” Scientia Geographica Sinica 38 (8): 1292–1300. (in Chinese). doi:10.13249/j.cnki.sgs.2018.08.011.

- Zui, H., S. Josef, Q. Min, M. Tan, and F. Cheng. 2021. “Visualizing the Cultural Landscape Gene of Traditional Settlements in China: A Semiotic Perspective.” Heritage Science 2021 (9): 115. doi:10.1186/s40494-021-00589-y.