ABSTRACT

The designation of historic conservation areas (DHCAs) from the cities classified as “National Famous Historical and Cultural City” (NFHC-city) is the key tool for maintaining large-scale historic environments, wherein the boundaries are blurred because of redevelopment. Therefore, exploring potential historic conservation area is fundamentally important. In this study, we examined historic urban areas in 11 old colonial cities (concessions and leased territories) to determine the potential historic conservation areas (P-HCAs). Our results suggest that P-HCAs are characterized by relatively small size, minimal residential use, and irregular morphological boundaries, except in some non-NFHC-cities, where P-HCAs are located adjacent to officially protected public and commercial buildings. The DHCA boundaries and extent of urban development influence the storage of P-HCA. The approach and method proposed in this study not only provide reference for the conservation and replenishment of the historic districts in China, but are also applicable for other countries.

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

Since the mid-20th century, there has been a significant increase in the global interest toward heritage conservation and management; this interest is generally linked to the understanding of heritage areas and novel approaches for managing the changes in the historic environment (Chen, Ludwig, and Sykes Citation2021). The Chinese historical heritage conservation system, which consists of designation of historic conservation area (DHCAFootnote1) from the city designated as “National Famous Historical and Cultural City” (NFHC-cityFootnote2), is one of the most effective methods to maintain large-scale historical environments. With rapid urbanization, some cities in China have deliberately selected a small number of historic districts to meet the requirements of the NFHC-city policy to obtain more land for construction, whereas some districts have not been selected for protection because of vague indicators such as style. Even if cities meet the quantitative indicators such as area, many of them face the problem of large-scale demolition and reconstruction of historic districts (Chan and Ma Citation2004). For example, although Shanghai was recognized as an NFHC-city in 1986 and a representative DHCA was selected; many Shikumen Lilong neighborhoods representing the old cultural DNA of Shanghai were not granted the DHCA status because Shanghai has many Shikumen residential neighborhoods. Because the selection of DHCA is strict and cumbersome, Shanghai cannot designate all Shikumen Lilong neighborhoods as DHCA, and they have been demolished under the pressure of urban renewal (Liu Citation2016). Therefore, in the context of the massive disappearance of historic urban areas in China, it is difficult to effectively protect the historic urban areas by relying only on the existing DHCAFootnote3 classification criteria; it is necessary to assess and integrate potential historic conservation areas (P-HCAsFootnote4) into the historic conservation system (Cai, Liu, and Xin Citation2021). However, because the boundaries of P-HCAs are unclear, it is critical to determine the stock of P-HCAs and develop novel conservation strategies based on the characteristics of areas using quantitative analysis methods.

Notably, P-HCA is not an internationally used term, and in the mainstream Western context of historic district conservation, it was the Declaration of Amsterdam of 1975 that attracted attention to the conservation of historic districts. In the Western heritage conservation system, historic districts are often considered as a whole, and in urban development, new cities are often built in the suburbs to preserve and cautiously renew the buildings of the old cities. Therefore, no officially recognized small conservation areas or neighborhoods are omitted by heritage laws (Rodwell Citation2003). Studies on historic districts in Western countries frequently focus on urban morphological features (Colaninno, Roca, and Pfeffer Citation2011), building renovation restrictions and guidance (Yukinobu Citation2000), urban landscape formation (Zeayter and Mansour Citation2018), and multidisciplinary connections in the conservation of historic district landscapes (Fiorino and Pirinu Citation2017). According to Cai, Liu, and Xin (Citation2021), P-HCA is a concept based on a unique historic district neighborhood preservation policy system in China, which can be defined as “old neighborhoods that are not designated as DHCA by the government but have certain characteristics of street style and cultural heritage”. They have the following three characteristics: not officially recognized, unclear boundaries, and a long-standing social community network.

In contrast, research on historic districts in China has majorly focused on DHCA. Most of the current studies on DHCA in China have focused on theoretical improvements in conservation. When demonstrating the setting process and operation mechanism of the NFHC-city conservation system, Zhang (Citation2012) referred to the problems posed by insufficient restrictions on urban renewal in historic districts and the preservation of historic districts via redevelopment. Ruan and Sun (Citation2001) proposed an approach for setting the conservation scope in terms of landscape management and functional use guidance of the neighborhood. In addition, among the studies that examined the morphological feature characteristics of historic urban areas in China, some highlighted the characteristics of Suzhou and Guangzhou, based on the theory of spatial syntax (Huang and Ji Citation2019; Wu, Fang, and Shi Citation2019). Moreover, Liu et al. (Citation2017) argued that the conservation and development of P-HCA should involve a highly diverse evaluation mechanism and an operational mechanism of government–enterprise cooperation to achieve the purpose of historical continuity and economic value creation. Simultaneously, some studies explored the effects of preservation and development of P-HCAs in specific cities from the perspectives of continuation of the neighborhood commercial function (Xia Citation2021) and neighborhood texture preservation (Wang et al. Citation2017). In addition, Yang (Citation2022) pointed out that the P-HCA of the non-NFHC-city of Jiangyin should not only focus on the physical conservation, but also the formulation of policies, such as restoration of characteristic cultural activities, preservation of original living paradigms of residents, and development of guidelines for renovation of residential houses. However, no research has analyzed the spatial inventory and morphological characteristics of the neighborhoods of P-HCAs.

It is highly appropriate to explore this topic in the context of concessions and leased territories in China, which began in the 1860s with the conclusion of numerous territorial leases and treaties of commerce; the Qing dynasty leased land along the eastern coast of China to the British, French, and Japanese governments. We further call this period the “colonial era.Footnote5” These foreign colonial cities were divided into “concession” and “leased territories.” Concessions refer to the leasing of a portion of a governed area in a city to a certain country, and a city may have multiple concessions, such as Shanghai and Tianjin, which are representative of such cities. Leased territories refer to the leasing of a large area of a territory to a certain country, accompanied by the urban planning of the suzerain state to form a larger modern city, such as Qingdao and Dalian. Although these urban legacies are not rooted in the local Chinese culture, they are a relevant part of the urban and architectural heritage because they were formed during the “colonial era” and therefore have distinctive historical value. In the 1980s, with the economic development in China, the pressure of the concessions and leased territories, which were the pioneers of the economic development, gradually increased, and large areas of the concessions and leased territories were demolished. However, these colonial cities still retain some historic districts that are not designated as DHCA owing to the large area of historic urban area, and are therefore suitable as a sample for this study to examine the stock and spatial characteristics of P-HCA.

For modern concessions, significant research has been conducted on the history of related urban development and formation. Jiang and Fujikawa (Citation2013) illustrated the formation process of the road network of street trees in the city of Qingdao. For the Tianjin Concession, Liu and Fujikawa (Citation2015) addressed the formation process of the British Concession. Moreover, Wang, Matsumoto, and Sawaki (Citation2019) reviewed the impact of commercial renovation of historic buildings on streetscape preservation and highlighted the problems of the existing renovation approval criteria, focusing on the British Concession in Tianjin, which was selected as a DHCA. However, the above-mentioned studies did not discuss the P-HCA of modern concessions. Moreover, in the analysis of the morphological and scaling characteristics of a region, these studies did not consider the old neighborhoods of the tenement cities not listed in the conservation list. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to fill this gap by examining the potential historic conservation area in China.

This study focused on historic districts formed during the “colonial era” and used the quantifiable criteria of neighborhood “area” and “area ratio of historic buildings to the entire site” in the DHCA designation to determine the boundaries and stock of P-HCAs. The cities were also classified by stocks of P-HCAs and DHCAs. In addition, this study aimed to analyze the characteristics of the P-HCA in each area, including original functions of the architecture, and morphological characteristics of each block in the district. This study can serve as a basis for the future conservation of unclassified historic districts and serve as a novel approach toward redefining their scope of preservation.

2. Methodology

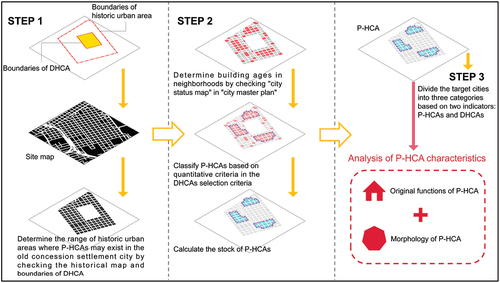

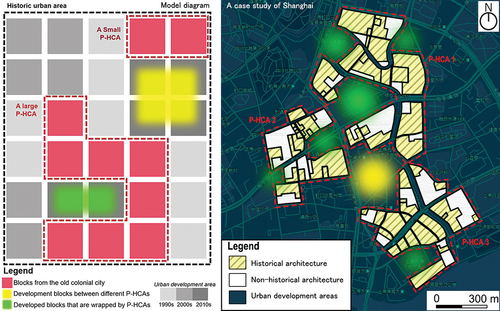

To capture the stock of P-HCAs and to elucidate the characteristics of these neighborhoods, this study had three main steps: (1) determine the range of historic urban areas where P-HCAs may exist; (2) calculate the stock of P-HCAs; and (3) classify the object cities based on P-HCAs and DHCAs (). Based on these steps, the characteristics of the P-HCAs were finally analyzed.

In the first step, to determine the extent of historic urban areas where P-HCAs may be present, we confirmed the boundaries of the historic urban areas in the selected cities by examining each historical map of each old colonial cities. To define the boundaries for the designation of DHCAs, we examined the protection plan of the historical sites of the selected cities and then removed the DHCA boundaries from the historic urban areas. Finally, a historic urban area with the possible presence of P-HCAs was obtained.

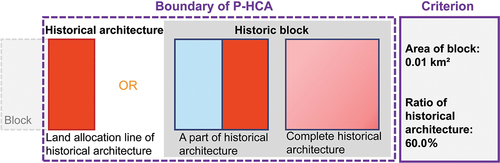

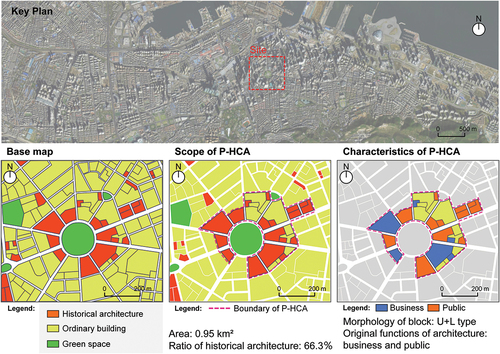

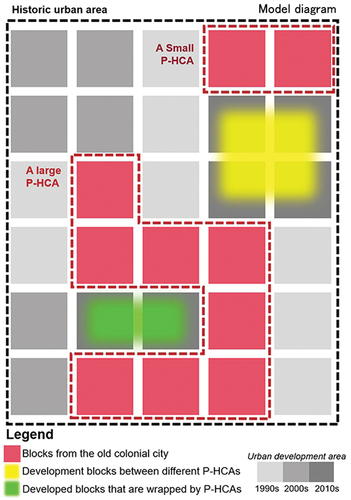

In Step 2, we focused on historical urban areas where P-HCAs may exist by consulting the “city status map” in the “city master plan” of each municipality, determined the boundaries of land allocation units and the construction dates of buildings in the neighborhoods, and then extracted the neighborhoods with historical buildings from the “colonial era.” Based on this information, we classified the P-HCAs, and based on the quantified criteria in the DHCAs selection criteria, we established the following principles for the classification: (1) Adjacent neighborhoods with historic buildings or land allocation units can form a neighborhood (). (2) The district with area not less than 0.01 km2 and the architecture in concessional period occupying over 60% of the total district area. (3) Derive the blocks with the largest possible area. As shown in , we demonstrated the specific steps of delineating P-HCAs using Dalian as an example. The reason for choosing this example is the relatively complex morphology of Dalian neighborhoods and the high abundance of building types in the neighborhoods.

In Step 3, after capturing the stock of P-HCAs via Step 2, we divided the target cities into three categories based on two indicators–P-HCAs and DHCAs–and analyzed the reasons for the formation of each category.

Finally, after deriving the P-HCAs, we analyzed the original functions and morphological characteristics of each block in the district. The architectural style and planning in the P-HCA was determined using the Street View of Baidu Maps for determining original functions of the historical architecture. To understand the P-HCA characteristics of Shanghai and Dalian within the remains of historical buildings, we referred to the books “History guide map of Shanghai” and “History guide map of Dalian and Lvshun,” to learn the original building functions of the P-HCAs. For the morphological characteristics of the neighborhoods, we typified them with the morphology of the borderline.

3. Background of case studies

3.1. Division of concessions and leased territories and designation of historic and cultural cities

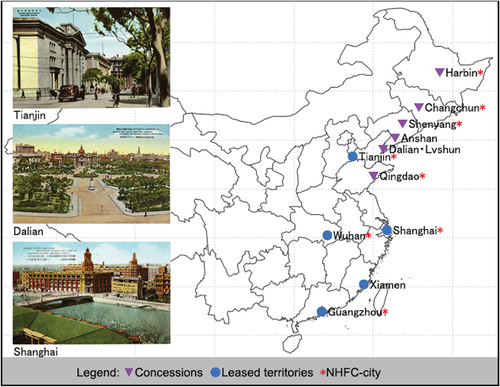

demonstrates the location of the target cities and the division of the concessions and leased territories, as well as the conditions required for being designated as an NFHC-city. Five cities (Guangzhou, Shanghai, Tianjin, Wuhan, and Xiamen), out of the total 11 cities considered in this study, used concessions occupied by the United Kingdom, Japan, or the United States of America. Notably, the six cities Qingdao, Harbin, Changchun, Shenyang, Dalian, and Anshan used to be concessions that once belonged to Germany, Russia, or Japan. In terms of the conditions for being designated as NFHCcities, eight cities (Guangzhou, Shanghai, Tianjin, Wuhan, Qingdao, Harbin, Changchun, and Shenyang) were considered as NFHC-cities. The cities not considered as NFHC-cities were Dalian, Anshan, and Xiamen.

Figure 4. Location of the target cities, division of the concessions and leased territories, and boundary of the city in the National Famous Historical and Cultural City (NFHC-city) Conservation System.

(Source: Figure of Tianjin: https://app.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp/infolib/cont/01/G0000022PPC/000/061/000061647.jpg; Figure of Dalian: https://app.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp/infolib/cont/01/G0000022PPC/000/063/000063897.jpg; Figure of Shanghai: https://rmda.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp/item/rb00031383#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&r=0&xywh=−15%2C124%2C4934%2C1925)

3.2. Stock of Designated Historic Conservation Area (DHCA) and categories of designation in the target city

After being designated as an NFHC-city, the local municipal government would be obliged to select one or more DHCAs that would represent the historical features of the region, and then carry out guaranteed conservation. Some cities selected their DHCAs based on the local regulations. For example, Xiamen has a city-level designated DHCA although it is not an NFHC-city.

presents the number and area of DHCAs and the ratio of DHCAs in the historic urban area. A total of 43 DHCAs were identified from eight NFHC-cities and the city-level historic urban areas of Xiamen, approximately half of which belonged to Qingdao and Tianjin. In terms of area, Shanghai and Qingdao cover an area of over 10 km2, whereas Tianjin and Changchun cover an area of 5 km2. In contrast, Harbin and Shenyang, as well as Guangzhou, Wuhan, and Xiamen, which have smaller historic urban areas, cover an area of only 3 km2. In terms of the proportion of the DHCA in the historic urban area, the boundary of the DHCA in Qingdao, Guangzhou, and Xiamen coincides with that of the historic urban area, thus indicating a proportion of 100%. Wuhan accounts for 58% of the total area, whereas other cities account for less than 50% of the total area.

Table 1. Number and area of designated historic conservation area (DHCA), and the ratio of DHCA in the historic urban area.

lists the categories for the designation of the DHCAs. In terms of the categories, there were 41 modern-type DHCAs having “modern neighborhood, with typical architectural styles,” and one for each of the “revolutionary heritage type DHCA” and the “waterfront landscape type DHCA.” Among the categories of the “modern-type DHCA,” except the public and commercial (business-oriented) buildings (16 each), most blocks are considered to be residential blocks (15 individual and 12 collective residences) because they are typical of architectural style.

Table 2. Categories for designation of historic conservation area (DHCA) (n = 43).

4. Results

4.1. Stock of Potential Historic Conservation Area (P-HCA), Classification of Target Cities based on P-HCA, and Designation of Historic Conservation Area (DHCA)

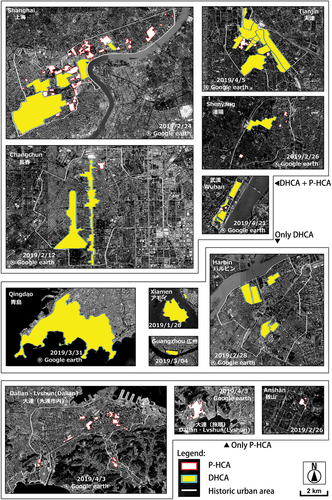

The locations of DHCAs and P-HCAs in the target cities are shown in . The areas of the P-HCAs in the target cities are shown in . All the target cities, except for Qingdao, Xiamen, Guangzhou, and Changchun, have P-HCA stocks.

Figure 5. Locations of the designated historic conservation area (DHCA) and potential historic conservation area (P-HCA) in the target cities selected in this study.

Table 3. Area of potential historic conservation area (P-HCA) in the target cities.

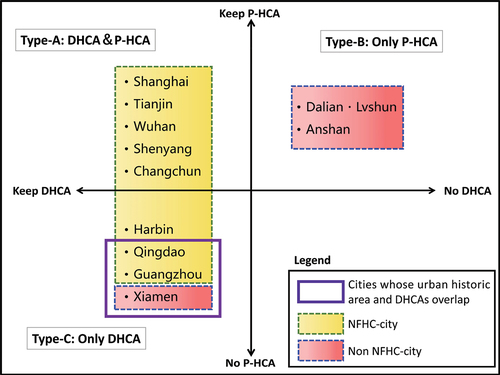

Based on the presence/absence of DHCA and P-HCA in a city, we categorized the cities into three groups: “Type A: DHCA and P-HCA” (Shanghai, Tianjin, Wuhan, Shenyang, and Changchun), “Type B: Only P-HCA” (Dalian and Anshan), and “Type C: Only DHCA” (Qingdao, Guangzhou, Harbin, and Xiamen) (). From the aspect of the P-HCA area and the proportion of the P-HCA in the historic urban area, the characteristics of the three types of cities were analyzed as follows:

Figure 6. Types of cities based on designated historic conservation area (DHCA) and potential historic conservation area (P-HCA).

4.1.1. Type A: Designated Historic Conservation Area (DHCA) and Potential Historic Conservation Area (P-HCA)

In this type, both the DHCA and P-HCA co-existed in the historic urban area. In our study, the DHCA in Shanghai covered the largest total area and the highest composition ratio in the historic urban area, along with a relatively large number of P-HCAs. In contrast, the P-HCAs in Tianjin, Wuhan, Changchun, and Shenyang were 0.4 km2, and the proportion in the historic urban areas was below 5%.

Regarding the reasons for the impact of P-HCA stocks, in Tianjin and Wuhan, in addition to urban development, there was already a high number of DHCAs, which resulted in a smaller number of P-HCAs. The smallest area of P-HCA in Wuhan corresponded to its small historic urban area. Changchun and Shenyang lost large historic urban areas due to rapid urban development. These heavy industrial cities in Northeast China have already begun urban renewal (with the help of large state-owned enterprises) at the beginning of the planned economy era since the 1950s.

4.1.2. Type B: only Potential Historic Conservation Area (P-HCA)

In the cities belonging to this type, the DHCA area in Anshan was only 0.158 km2, but Dalian had a larger P-HCA of 1.55 km2. This may be because only a part of the city buildings was officially protected. Note that the presence of several military-owned buildings may have inhibited the rapid development of the city.

4.1.3. Type C: only Designated Historic Conservation Area (DHCA)

The reasons for the non-existence of P-HCA in the cities belonging to this type are simple and clear. Qingdao set the boundary of the urban historic area as the conservation boundary of the urban historical environment aiming at initial conservation of city. Guangzhou and Xiamen contained comparatively smaller concession areas; for these cities, we could achieve the boundary of the entire historic urban area, according to the conservation boundary of the DHCA. For Harbin, similar to the Changchun and Shenyang cities (among the Type-A cities), the historic urban area outside the DHCA disappeared owing to the ongoing urban development since the 1950s.

4.2. Characterization of Potential Historic Conservation Area (P-HCA)

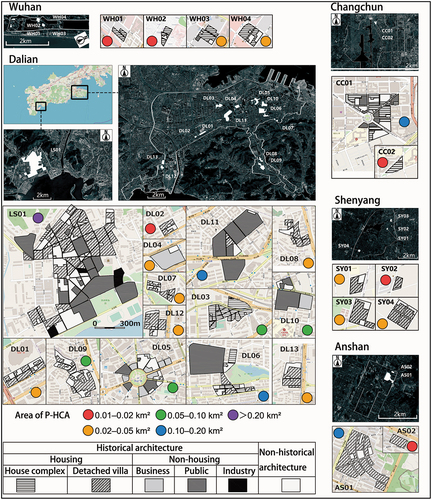

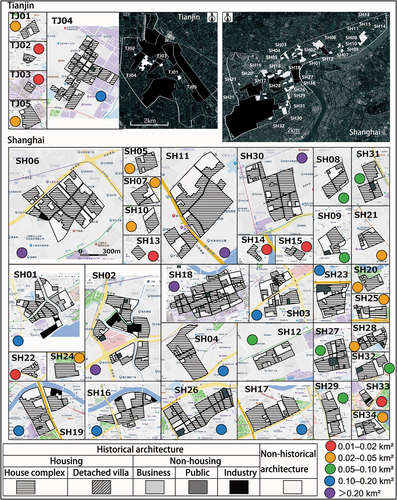

clearly illustrate the area, original functions of architecture, and morphology of blocks in the target cities. A total of 65 P-HCAs were confirmed in the target cities, including 34 in Shanghai and 14 in Dalian. The number of P-HCAs in other cities was less than 10.

Figure 7. Initial functions of potential historic conservation area (P-HCA) in non-national famous historical and cultural city (non-NFHC-city).

Figure 8. Initial functions of potential historic conservation area (P-HCA) in national famous historical and cultural city (NFHC-city).

4.2.1. Characteristics of the area of Potential Historic Conservation Area (P-HCA)

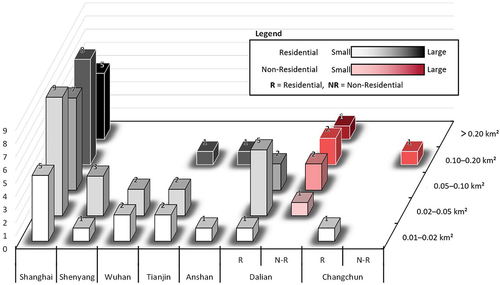

In terms of the area of a single P-HCA, more than 90% of the blocks had P-HCA less than 0.2 km2. In terms of the DHCA, 70% of the blocks had areas larger than 0.2 km2 (). Based on such characteristics, in the future, for conservation, it will be more effective to classify the adjacent small P-HCAs into a group, rather than planning the conservation of only a single P-HCA.

4.2.2. Initial functions of architecture in Potential Historic Conservation Area (P-HCA)

From the initial functions of architecture, P-HCAs can be categorized into six types, among which historical architecture can be classified into business, public and industrial buildings, and individual and collective residences. In this study, the other non-historical architectures were classified into one category.

Considering the proportion of residential buildings to the total area of the site (residential rate) as an indicator, the proportion of residential buildings in most blocks was larger than 60% (). Such blocks can be defined as residential P-HCAs. Among the target cities, Shanghai had the largest number of residential P-HCA (n = 34) and collective residences, with an intensive living density; Li-Nong accounted for the largest percentage. If the government considers preserving these buildings in the future, improving the living environment will be a major issue. In addition, in terms of the two indicators of “residential rate” and “area,” a vast majority of blocks were residential P-HCAs having an area of less than 0.1 km2 ().

Figure 11. Characteristics of the potential historic conservation area (P-HCA), based on the indicators of the residential rate and area.

We observed a few P-HCAs having lower residential rates; most of these P-HCAs were concentrated in Dalian (6 P-HCAs). These P-HCAs contained a large number of public and commercial architectural buildings that were officially protected, and such blocks were often designated as DHCAs in the NFHC.

Finally, several non-historical architectural buildings also existed in the P-HCA, most of which exhibited the partial renovation pattern that was generally seen before 2000.

4.2.3. Morphology of block in Potential Historic Conservation Area (P-HCA)

Based on the morphology of the block, the P-HCAs were divided into three types: I, L, and U + L. The complexity of their shapes and the closeness of their association with the surrounding blocks were also considered. In general, the boundary between the I-shaped P-HCA and the ordinary block was clear. The ordinary block formed a street corner inside the L-shaped P-HCA, whereas the U + L-shaped P-HCA had the characteristics of an L-shaped P-HCA and even wrapped a part of the ordinary street into its interior.

The correlations between the morphology of the block and the block area are listed in . Almost all the blocks having areas less than 0.05 km2 were I-type and L-type blocks, and the ratio of I blocks to the blocks having areas less than 0.02 km2 was close to 70%. Among the blocks having an area of 0.05–0.1 km2, L-shaped blocks accounted for the vast majority, with a ratio of 72.7%. For the blocks having an area of more than 0.1 km2, the ratio of the U + L blocks exceeded 60%, i.e., if the P-HCA was large, it was easy to portray a complex morphology.

Table 4. Correlation between the morphology of block and block area.

The building function and ownership of colonial cities are generally complex; for example, during urban development, large areas cannot be constructed in a short time. Therefore, as shown in , when the blocks that were not developed were divided into P-HCAs, the complex morphology of the study area could be easily portrayed.

5. Conclusions

This study elucidated the stocks and characteristics of DHCAs and P-HCAs in China’s old colonial cities. In NFHC-cities, the government has set a DHCA to protect the historical environment, based on the public, commercial, and residential use. However, owing to the differences in the size of the historic urban area in each city and the government’s principles for setting DHCA boundaries, the DHCA in each city and its proportion in the historic urban area are different.

Among all the cities considered in this study, the stock of P-HCA has been confirmed in both the NFHC-cities (Shanghai, Tianjin, Wuhan, Shenyang, and Changchun) and non-NFHC-cities (Dalian and Anshan), with the only exception being Qingdao, Guangzhou, Harbin, and Xiamen. Therefore, based on whether a city has DHCA and P-HCA, we considered the following three types: “Type A: DHCA+P-HCA,” “Type B: Only DHCA,” and “Type C: Only P-HCA.” The storage of P-HCA in most cities was small, except in Shanghai and Dalian. The DHCA boundary setting of these cities and the intensity of urban development were the main factors that affected the P-HCA storage in these regions. Additionally, in these cities, the P-HCAs disappeared with further development.

In this study, we focused on individual P-HCAs, most of which were characterized by a relatively small size, residential use, and irregular morphological boundaries. However, in non-NFHC-cities, such as Dalian, we observed that P-HCAs were mainly composed of several public and commercial officially protected architecture buildings.

Based on the above conclusions, if the P-HCA in a city is also regarded as a historic area that should be conserved in the future, the following four suggestions are meaningful:

Because most of the blocks are not large while planning conservation, several adjacent blocks can be regarded as a unified planning group. Simultaneously, new or redeveloped blocks between different P-HCAs should be included in the scope of conservation, and their appearance, height, and usage should be regulated and guided for them to be in agreement with the P-HCAs.

Because most buildings in the blocks are used for housing, improving the quality of residence should be considered an important issue in future conservation plans.

In the case of non-NFHCcities, such as Dalian, some P-HCAs contained a large number of officially protected architectural sites. The historical area formed by this type of historical architecture has conservation value; therefore, such blocks can be identified as DHCA in local city-level protection policies.

Because many P-HCAs have an irregular morphology, they are more closely related to surrounding blocks; notably, some developed blocks may also be surrounded by P-HCA. Therefore, when formulating conservation plans, significant attention should be paid to the relationship between the two types of blocks. Novel ideas need to be implemented in such cases, e.g., setting up pocket parks in enclosed areas to serve as visual buffers or strengthening the townscape control of general streets at the border of P-HCA.

The methodology and findings of this study provided new insights into the protection of historic districts in the Chinese conservation system, i.e., “National Famous Historical and Cultural City.” The protection of historic districts can not only be limited to the level of historic and cultural districts, but also for other historic districts. To achieve this, a flexible criterion level for the identification of potential historic conservation area (P-HCA) can be created to complete the policy framework for the protection of historic districts. Meanwhile, the criteria for designating and recognizing P-HCAs are not entirely consistent with those for DHCAs, as more P-HCAs could be identified if the proportion of historic buildings in the area is reduced. Therefore, a more lenient and flexible designation criteria might be more beneficial to the conservation of the historic environment.

Although this study provided novel insights, it has some limitations. First, it primarily focused on the policy of historic city protection and did not compare the identification of historic districts under other policies; secondly, this study focused on the inventory and classification of districts, but did not assess the heritage value of potential historic districts. Hence, it calls for future investigations wherein a systematic heritage-value assessment study based on the findings of this study can be developed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The historic area reviewed and officially approved by the Provincial People’s Government.

2 The city that is rich in cultural relics and possess significant historical value or revolutionary significance simultaneously is approved by the State Council of China as an authoritative historic city.

3 The criteria for modern historic conservation area represents the district with area not less than 0.01 km2 and the architecture in concessional period occupying over 60% of the total district area.

4 The area that fits the criteria of historic conservation area, while not recognized as historic conservation area.

5 The opening and revocation of concessions changed from city to city, with the British government opening the first concession in Shanghai in 1842, while most cities had concessions opened in the 1860s and 1890s. Most of the concessions were revoked in the 1940s, although some cities revoked certain concessions as early as 1917.

References

- Cai, X., C. Liu, and S. Xin. 2021. “A Review of the Comparative Study of Historical Blocks and Nonprotected Histori-cal Blocks.” Architecture & Culture 03 (68): 182–184.

- Chan, W., and S. Ma. 2004. “Heritage Preservation and Sustainability of China’s Development.” Sustainable Development 31 (November 2003): 15–31.

- Chen, F., C. Ludwig, and O. Sykes. 2021. “Heritage Conservation through Planning: A Comparison of Policies and Principles in England and China.” Planning Practice and Research 36 (5): 578–601. doi:10.1080/02697459.2020.1752472.

- Colaninno, N., J. Roca, and K. Pfeffer. 2011. An Automatic Classification of Urban Texture: Form and Compactness of Morphological Homogeneous Structures in Barcelona. Barcelona: 51st Congress of the European Regional Science Association.

- Fiorino, D. R., and A. Pirinu. 2017. “Interdisciplinary Contribution to the Protection Plan of the Fortified Old Town of Cagliari (Italy).” International Journal of Heritage Architecture: Studies, Repairs and Maintence 1 (2): 163–174. doi:10.2495/ha-v1-n2-163-174.

- Huang, K., and M. Ji. 2019. “Research Onthe Sustanable Conservation of Urban Historic Enviroment Base on Spase Syntax : A Case Study on Xiguan Historic Area in Guangzhou.” New Architecture 06: 21–25.

- Jiang, B., and M. Fujikawa. 2013. “The Formation Process of Qingdao’s TREE-LINED Streets (1891-1945).” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 78 (693): 2321–2328. doi:10.3130/aija.78.2321.

- Liu, G. 2016. “Reflection on Shanghai Shikumen Lilong Rehabilitation.” HERITAGE ARCHITECTURE 4: 1–11.

- Liu, Y., and M. Fujikawa. 2015. “The Development Process of the Original British Concession in Tianjin, China.” Journal of Architecture and Planning (Transactions of AIJ) 80 (712): 1285–1294. doi:10.3130/aija.80.1285.

- Liu, J., W. Huang, L. Wang, N. Shi, J. Yang, and S. Wang. 2017. “Organic Renewal of Urban NON-PROTECTION Blocks.” CITY PLANNING REVIEW 03: 94–98.

- Rodwell, D. 2003. “Sustainability and the Holistic Approach to the Conservation of Historic Cities.” Journal of Architectural Conservation 9 (1): 58–73. doi:10.1080/13556207.2003.10785335.

- Ruan, Y., and M. Sun. 2001. “Some Problems in the Protection of Chinese Historic Conservation Area.” City Planning Review 25 (10): 25–32.

- Wang, Y., K. Matsumoto, and M. Sawaki. 2019. “STUDY ON CONVERSION STORE RENOVATION EXAMINATION AS WELL AS ITS EFFECTIVENESS AND ISSUE IN LANDSCAPE PRESERVATION OF HISTOR-ICAL DISTRICT—The Case OF Wudadao Historical District, Tianjin, China.” Journal of Architecture and Planning 84 (766): 2617–2627. doi:10.3130/aija.84.2617.

- Wang, H., X. Yuan, K. Wei, H. Chang, and X. Chen. 2017. “Historical Block Preservation and Renovation.” Planners 04: 143–147.

- Wu, Z., Y. Fang, and Z. Shi. 2019. “Research on Spatial Forms of Historical and Cultural Blocks Based on Space Syntax: Taking the Changmen Historical and Cultural Block in Suzhou as an Example.” Architecture & Culture 12: 36–38.

- Xia, Y. 2021. Research on the Renovation of Non ProtectedTraditional Commercial Blocks in Old Cities– A Case Study of Longfu Temple Area. Beijing, China: North China University of Technology.

- Yang, C. 2022. “Cultural Landscape Space System: A Case Study on the REGENERA-TION Planning of NON-HISTORIC and Cultural Old City of Tangyin.” CITY PLANNING REVIEW 05: 81–92.

- Yukinobu, W. 2000. “Study on the Control of Storeboards in a Historic Landscape in France Case Study in Safeguarded Sector in Dijon.” Journal of the City Planning Institute of Japan 35: 709–714.

- Zeayter, H., and A. M. H. Mansour. 2018. “Heritage Conservation Ideologies Analysis – Historic Urban Landscape Approach for a Mediterranean Historic City Case Study.” HBRC Journal 14 (3): 345–356. doi:10.1016/j.hbrcj.2017.06.001.

- Zhang, S. 2012. “On the Basic Characters and Challenge of the Conservation Mechanism in Historic and Cultural Cities.” Urban Development Studies 19 (9): 5–11.