ABSTRACT

Safety is a top priority in the construction industry; therefore, safety training is essential to prevent construction casualties as the employment of foreign and young workers on construction sites worldwide increases. More studies are necessary to identify the effective training methods among novices and foreign workers. To address the gap, a rigorous comparative study of verbal and non-verbalized materials from two different countries was conducted. Statistically significant differences were found between nationalities in non-verbal materials due to different safety culture and background, and insignificant differences were found between both safety training materials with the same nationality. By comparing the outcomes of both training materials, the non-verbalized materials work effectively among the construction novices to provide visual aid to relate similar attitudes like technical trainees to the scenarios even without field experiences. The non-verbalized materials provide an alternative to passive learning methods to enhance the other safety training activities in the construction industry. The findings provide an initial stage for creating effective teaching materials that can be generally applied in other countries to capture the issues by a heterogeneous workforce personalized to suit the scenario of each country for better outcomes.

1. Introduction

Safety is one of the basic human rights based on the Work Human Rights Declaration (United Nations Citation2022), especially in the workplace. Construction industry is regarded as one of the unsafe occupational fields with complex work environment (Fang and Wu Citation2013) and depends on foreign labor workforce (Ismail et al. Citation2018) in many countries. It contributed a high rate of 30% of fatal accidents (International Labor Organization ILO Citation2021) where the construction workers are 3 times more likely than other workers to die from the occupational related accidents (ILO Citation2015).

Most of the construction accidents occur among foreign workers and young workers (Ajslev et al. Citation2017) due to language barriers (Oswald et al. Citation2019) and lack of safety training (Priyadarshani, Karunasena, and Jayasuriya Citation2013). In other words, construction workers decide how works jeopardize with their ability to identify potential accidents on construction sites that leads to accidents. Studies showed the fatal accident rate for foreign workers is two times higher than domestic workers in many countries such as Japan, Taiwan (Cheng and Wu Citation2013) and Malaysia (Department of Occupational Safety and Health DOSH Citation2016). In developing country such as Malaysia is encountered about 70% of construction foreign labours mainly from Indonesia and Bangladesh legal and illegal (Abdul-Rahman et al. Citation2012) and the unskilled foreign workers is the weakness in exchange of cheaper workforce (Ismail et al. Citation2018).

Each country has its own culture and customs; it is important to implement safety education in the receiving country to improve workers’ ability in risk recognition (Cheng and Wu Citation2013). Many countries in Southeast Asia have systems for safety supervision at construction sites, but have not developed regulations for safety training at these sites. Japan is one of the few countries that impose an obligation on general contractors to provide ongoing safety education and training for construction technicians working in the country, and the safety educational content is well-developed. In Japan, the safety and health education must be conducted by the construction companies when engaging workers and it is mandatory to provide said education without delay when there are changes of workers in the construction sites. The safety training for all the contractor’s personnel provided by the contractors must be designed in a language which the persons to be trained fully understand as appropriate (clause 1.19 in Japan International Cooperation Agency Standard Safety Specification) (JICA Citation2021). Japan enforced the Occupational Safety and health (OSH) multilingual teaching material and non-verbal OSH teaching materials for workers and foreign workers to promote safety training on site. The employers are obligated to provide safety and health education related to construction to all workers including new workers and foreign workers stated in the Article 59 of Industrial Safety and Health Act (Citation1972).

For instance, the construction accident rate* was recorded 6.27 in 2000 and reduced to 4.48 in 2020; the construction fatalities recorded 34% or 8,964 out of 26,104 total fatality cases caused construction workers died at construction sites between 2000 and 2020 in Japan (OSH Statistics in Japan Citation2020). The construction industry in Japan owns about 3.48% of foreign workers in 2019 among the total number of employees in the industry and most of the foreign workers are from Southeast Asia. The construction accident rate is declined in Japan prove that the effectiveness of the safety education among foreign workers in Japan which turns into a textbook for developed and developing countries.

However, there is a dearth of insight of the different nationalities workers’ safety performance after the verbalized materials of safety training. There are limitations of study focus on the safety training materials used in construction for workers with different characteristics and approaches, and how effectives of the safety training materials can be applied to different nationalities. Therefore, this study aims to identify, which materials can be worked effectively regardless the nationalities by comparing the differences attitudes of construction novices and workers who experiences the verbal and non-verbal safety materials. Three objectives were formed to achieve the aim:

to determine the differences attitudes in inexperienced personnel between Japanese and foreign workers,

to investigate the attitudes among different nationalities in non-verbal materials and

to find out the differences between verbal and non-verbal materials in construction safety training contents.

1.1. Construction safety training

Safety training is widely used intervention for preventing occupational injuries at work. Studies have showed that safety training is the effective method to educate and change the worker’s behaviours towards construction safety issues to reduce the construction accidents (Jaafar et al. Citation2017; Winge, Albrechtsen, and Mostue Citation2019; Casey et al. Citation2021; Vignoli et al. Citation2021; Wang, Jiang, and Blackman Citation2021) especially before and during the construction phases (Esmaeili and Hallowell Citation2012).

The key element of safety training was to improve the communication skills via verbal, non-verbal and cross-cultural to establish the effective safety training among the workers (Jeschke et al. Citation2017). Safety training is often mandated by regulators and contractors, which might limit the sense of choice for the construction workers (Casey et al. Citation2021). With the involvement of heterogeneous workforce in construction industry, in particular, the language barriers experienced by foreign workers, low education level (Arif et al. Citation2021) and differences in customs (Baseline Survey Construction Report Citation2015) regarding construction site safety are significant challenges with learning in safety training.

Besides, on a multilingual and multicultural construction site, the workers are unable to rely on a shared verbal language especially during the safety training (Oswald et al. Citation2019). Differences in customs cause workers on the same construction sites speak different languages, which can lead to different understanding of the safety training that the workers must attend, and the foreign workers often work with people from the same cultural background which hinders the learning of the safety norms, regulations and language of the host country (Al-Bayati et al. Citation2017). Many foreign workers employed in the construction industry have problems in understanding safe work procedures and instructions due to language issue (Dai and Goodrum Citation2011; Cheng and Wu Citation2013; Demirkesen and Arditi Citation2015; Ismail et al. Citation2018). Therefore, how to effectively provide workers from multinational with consistent safety knowledge and training has become a challenge.

1.2. Safety training methods

The safety training methods such as lecture (Başağa et al. Citation2018), toolbox training (Jeschke et al. Citation2017), and audio-visual materials (Blanchard and Simmering Citation2014) able to provide better explained on the hazards to reduce the accident rate by improved the workers’ knowledge acquisition and behaviour alteration (Gao, Gonzalez, and Yiu Citation2019) by the use of listening, visual and reading, and the learning outcomes are based on individuals, varies.

Some researchers considered the traditional safety training is not an ideal solution for construction workers (Guo, Yu, and Skitmore Citation2017) when compared with more intensive forms of instruction (Burke et al. Citation2011), yet, these approaches were implemented in most of the countries as construction companies’ restraint safety budget for high-tech safety training (Mohammadi, Tavakolan, and Khosravi Citation2018), since it is sufficient to enhance the basic safety knowledge among the workers effectively with statistical evidence (Gao, Gonzalez, and Yiu Citation2019).

Proper safety training with lecture able to improve the fall safety knowledge, risk perceptions, comprehensive safety and safety culture on worksite by the workers (Forst et al. Citation2013; Evanoff et al. Citation2016). The BLR (Citation2014) report suggest using more visual aids in safety training sessions could provide benefits of being self-paced. Learners are involved in a passive method with the given instruction and information, therefore, proper safety training suits to construction sites cultures is necessary to conduct for the construction workers regularly to enhance the safety knowledge.

The visual aids able to sustain the workers’ interests and attention to solve the language problems during the training sessions to improve safety training (Demirkesen and Arditi Citation2015; Guo, Yu, and Skitmore Citation2017). The non-verbalized content with related safety contents as part of the safety training methods used in construction industry resulted in better knowledge transfer, especially when the video-based learning with a conclusion and slight humor able to provide better understanding and clarity to teach the non-native speaking workers (Arif et al. Citation2021). Many types of safety training involved visual-aid approaches have been introduced to promote the construction safety issues (Li et al. Citation2018; Ahn et al. Citation2020; Nykänen et al. Citation2020; Zujovic et al. Citation2021). Previous study revealed that the less information-dense and visualized training materials such as videos with graphics performed the best at stimulating learning across age groups (Wallen and Mulloy Citation2006).

1.3. Research methodology

From the previous research above, what we can understand is that language, culture, and tools go hand in hand to effectively implement safety education. In particular, we are interested in whether useful safety education content developed in one country would be useful in another country. Therefore, this study aims to identify the characteristics of non-verbal safety teaching materials experienced by the construction novices and foreign workers in Japan and Malaysia with the use of Japanese construction safety education materials. The performance of safety using non-verbalized materials was investigated through a comparative experiment among different nationalities of construction workers and novices who works in Japan and Malaysia construction sites. The Japanese safety training material with same contents was applied in the experiment. The respondents’ performances were obtained through a set of questions to determine if there are significant differences among the groups based on the verbal and non-verbal materials. The experimental design including the overview of the experiment, rationale of selected safety training materials, questions design and data analysis are explained in the following sections.

The human behaviour is significantly influenced by safety culture, and the safety culture can be divided into three levels ascending as PPE, operation procedures and safety concepts (Cheng and Wu Citation2013). Therefore, the selected training contents were based on the most occurring accident types reported in DOSH and JISHA as these contents are related to the unsafe working behaviour, unsafe working procedure, and unsafe site condition that mentioned earlier in the studies. The non-verbalized videos made by Planex, Japan was used in this experiment. The video is designed to help to understand what you are allowed to do, what you are not allowed to do, and why you are not allowed to do it. The video content included: proper attire, wearing a helmet properly, wearing a body belt-type safety belt properly, cutter work, up-and-down work, keeping things tidy, slinging a sling, wearing a full harness-type safety belt properly, and using portable work platform.

The video content demonstrated a series of safe behaviours; consequences of unsafe behaviours and how to prevent the consequences caused by unsafe behaviours. For instance, the video shows the right way to use PPE and tools on site, what injuries can result from incorrect PPE application and tool use, and how to prevent such injuries on sites through safe behaviours. The impressions between the construction novices and foreign workers in Japan and Malaysia after watching the video were observed, to determine whether there are any differences in impressions between the construction novices and foreign workers regardless of nationality.

In addition, a total of 60 questions were designed and developed by using the content produced by Planex, Japan as reference. The questions equally set for three sections, first section covers issues related to PPE; the second section covers issues related to working at height and use of tools, the third section covers issues related to lifting operations and site cleanliness. Each sections solicits two sub-sections namely general knowledge (5 questions) in multiple choices questions to check the baseline of the measurement; and the rationale to select the 7-points Likert-scale measurement (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree) for the scenario questions (15 questions) to check the impact of content on impression ratings from the participants.

The general knowledge questions were compulsory to examine differences in initial understanding towards safety training among all the respondents to accurately measure the outcomes of the experiment; while the scenario questions were designed according to the real situations to determine the respondents’ attitudes towards different scenarios on site. Most of the scenario questions were not reflected directly during the training sessions, therefore the attitudes on how will the respondents react and respond to the situations in construction sites can be tackled through the Likert-scale measurement. All the questions were prepared in multi-languages setting namely English, Japanese, Bahasa Malaysia and Vietnamese to suit all the respondents to eliminate the languages issue.

1.4. Experimental design

1.4.1. Overview of the experiment

A total number of 291 participants including 65 Malaysian undergraduates (taking courses in Construction Management), 71 Japanese undergraduates (taking courses in Project Management for Building Construction), 68 Japanese postgraduates (Architecture and Architectural Engineering course), 27 foreign workers (Indonesians) in Malaysia and 60 foreign technical trainees (Vietnamese) in Japan. The selected undergraduates possessed similar degree in the same field that generate a similar crowd, and received construction safety related lectures respectively in their universities. Therefore, we believe that the comparability is reasonable. The selected construction foreign technical trainees in Japan with less than three years of working experiences; and foreign workers in Malaysia with at least 5 years of working experiences in construction industry. All the construction companies will be anonymous due to private and confidential.

The participants were categorized into two main groups to received same training contents prepared in different materials (). Sub-group A receives verbalized material (photos and texts); Sub-group B receives the non-verbalized materials (no subtitle provided). The participants received the safety training contents categorized into three sections () via online platforms such as Zoom/Microsoft Teams etc. handled by the instructors in Japan and Malaysia respectively. The participants were requested to response a set of test questions via Google form after received the training materials through an online platform with the given access link. The foreign workers in Malaysia only available in non-verbalized materials due to low literacy level, therefore, the test for this group was conducted by reading the questions to receive response from all the foreign workers.

Table 1. Description of sample data.

Table 2. Safety training contents.

The group comparison of both training materials arranged in three ways namely: inexperienced personnel between Japanese and non-Japanese in Japan (JPA2-JPA3 and JPB2-JPB3); the non-verbalized material between nationalities (JPB1-MYB1 and JPB3-MYB3) and the verbal and non-verbal materials among the groups (JPA1-JPB1, JPA2-JPB2, JPA3-JPB3 and MYA1-MYB1) to reflect the research objectives. indicated the process of the experiment. The entire experiment process takes about an hour for each sub-groups.

1.5. Data analysis

Two major dimensions were defined to compare the training effectiveness between verbal and non-verbal training namely safety knowledge baseline measurement and evaluation of attitudes towards circumstances. The safety knowledge baseline measurement was measured through the score points obtained from the respondents; while the evaluation of attitudes was measured through the traditional scale measurement. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 16.0 was used to perform the Mann–Whitney U test in order to determine if the differences between the groups are statistically significant at p-value less than 0.05. The data were analysed by nonparametric tests, Mann–Whitney U Test as it is more suitable for skewed distributions or data with discrete or ordinal scale (Krzywinski and Altman Citation2014), to determine whether or not there is any significant differences in the mean scores between the groups by both training materials. As the nonparametric statistical analysis, Mann–Whitney U test ranks all the values ascending with a p-value to measure the discrepancy between mean ranks between two studies groups (GraphPad Citation2022). The smaller the p-value would suggest a more significant difference between the two experimental groups. It was assumed that if there were no significant differences, the content would be expected to have the same effect or not between the two countries, conversely, if there were significant differences, the content would be suggested the need to account for cultural differences.

1.6. Discussion on the findings

1.6.1. General knowledge

First, the average test score points under the safety knowledge sections (15 questions in total) were evaluated based on the correct answers obtained from each of the groups after the training. The Mann–Whitney U test was conducted for pairwise comparison among four groups. The results showed no significant differences in the overall safety knowledge among most of the groups in verbal and non-verbal materials, except for Japanese undergraduates of both materials for 2 sections, however, the score points obtained from this group in both materials were the second after Japanese postgraduates. In term of scored points, the non-verbal material tends to work better for undergraduates; while verbal material tends to work better in inexperienced personnel between Japanese and non-Japanese in Japan. The statistical analysis provides detailed information of each groups for three sections as shown in .

Table 3. Test scores for general knowledge among all groups.

1.6.2. Section 1: Personnel Protective Equipment (PPE)

Majority of the respondents answered all questions correctly in PPE section except question S1–2; precisely, about half of the undergraduates from the verbal group answered wrongly for the safer materials for work gloves as they do not experience hands-on activities such as cutting board on sites, therefore, this might be the reason why the answers were varied.

1.6.3. Section 2: work at height

Most of the students scored less satisfied for the section of “work at height”, especially to the question “What is the most appropriate height for the hook of the safety belt?”, 74% from verbal groups, 80% from non-verbal groups answered “height between waist and chest”, where the correct answer is “as high as possible”. However, the test score obtained from the construction workers were slightly higher as they own related experiences on site. Nevertheless, all the respondents who undergone non-verbalized materials were scored higher than verbalized materials in this section.

1.6.4. Section 3: lifting operation and site cleanliness

The average scored points for “lifting operation and site cleanliness” were generally higher than the other sections especially Japanese undergraduates scored 4.89 under non-verbal group; yet, Japanese postgraduates and technical trainees scored slightly higher for verbalized than non-verbalized materials. Only 60% of the Malaysian undergraduates and foreign workers answered correctly for the question S3–5 (), where this might due to the Malaysian undergraduates do not have such experiences and the foreign construction workers do not perform such practices in Malaysian construction sites.

1.6.5. Summary of general knowledge after both training materials

The results indicated no significant differences in inexperienced personnel between Japanese and non-Japanese in both training materials, yet, the postgraduates scored higher points than foreign trainee in both training materials which might due to different education background and safety culture. The scored points from Japanese undergraduates, postgraduates and technical trainees were similar and it indicates that they own a standardized level of understanding towards the safety knowledge compared to Malaysian undergraduates who performed less satisfied in both training materials. Statistically significant differences between Japanese and Malaysian undergraduates for 2 sections in non-verbalized materials (work at height, p < 0.05; lifting operation and site cleanliness, p < 0.001), but the scored points of all sections in non-verbal materials are higher than verbal materials for both undergraduates’ groups. The foreign workers in Malaysia performed moderately in the non-verbal material among all the groups as they own field experiences, which is slightly different from Japanese. The next session will be furthered discuss on the attitudes towards scenario questions by groups.

1.7. Attitudes towards construction sites situational questions

The obtained data were undergone Mann–Whitney U test to determine the significant differences of mean scores between verbalized and non-verbalized materials among four groups to find out differences in attitudes towards the scenarios on construction site based on different nationalities. The overall significant differences between both training materials among four groups were shown in . The discussion will be based on the set objectives with the smallest p-value as statistically highly significant differences.

Table 4. Differences between verbalized and non-verbalized materials by groups.

1.7.1. Objective 1: differences of attitudes between Japanese and foreigner by inexperienced personnel in Japan for verbal and non-verbal safety training materials

There are significant differences in three questions from two sections (PPE and correct way to use tools) for verbal materials and only one question with significant differences in non-verbal materials among the two experimental groups due to different opinions by the inexperienced personnel in Japan ().

Table 5. Differences of inexperienced persons in Japan for both training groups.

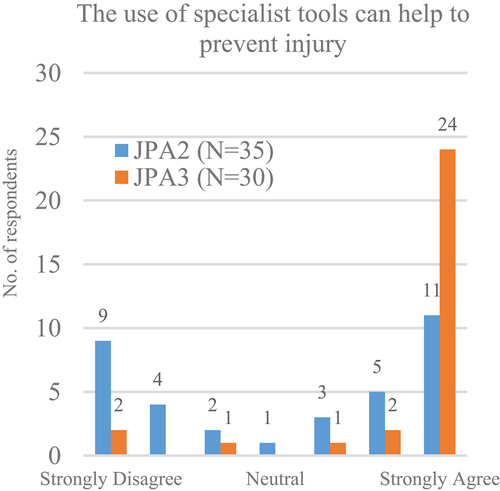

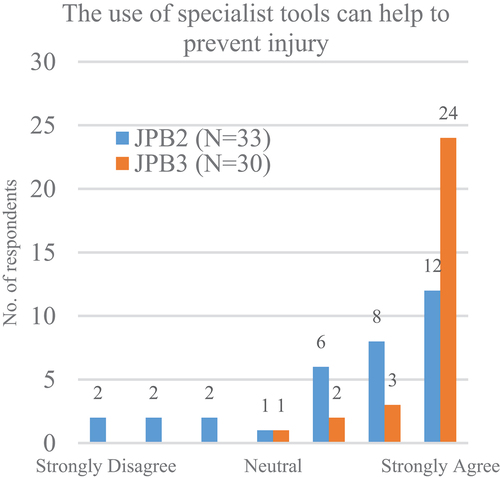

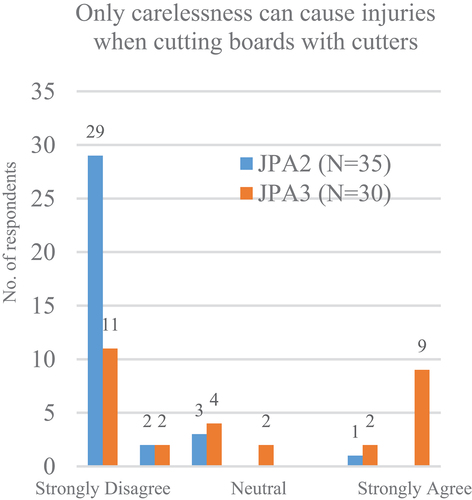

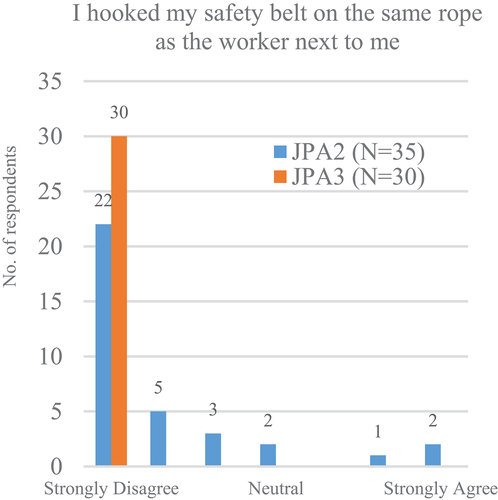

The differences in attitudes towards these questions were presented in . For instance, almost all the Japanese postgraduates and about half of the technical trainees “strongly disagree” to “Only carelessness can cause injuries when cutting boards with cutters”; while 37% of technical trainees considered carelessness is the major concern to cause injuries (S1–11). Besides, 77% of Japanese postgraduates and all the technical trainees “strongly disagree” to “I hooked my safety belt on the same rope as the worker next to me” (S2–16). Furthermore, about 46% of Japanese postgraduates and 80% of technical trainees “strongly agree” to “the use of special tools can help to prevent injury” (S2–18) in verbal materials; 57% of Japanese postgraduates and 80% of technical trainees “strongly agree” to this scenario in non-verbal materials.

Figure 2. (Left to right, top to bottom): Responses from the inexperienced personnel in verbal materials (Figure 2–4), and non-verbal materials (Figure 5).

Figure 3. (Left to right, top to bottom): Responses from the inexperienced personnel in verbal materials (Figure 2–4), and non-verbal materials (Figure 5).

1.7.2. Objective 2: differences between nationalities in non-verbal material

There were significant differences found between Japanese and Malaysian undergraduates for five questions; and significant differences between foreign technical trainees and foreign workers in Japan and Malaysia for ten questions. showed the scenario questions found significant differences between the groups under three sections. The attitudes towards the scenarios were slightly different among the experimental groups. The discussion begins with undergraduates then followed by foreign workers. These questions will be presented in to show the differences of attitudes by the respondents.

Figure 6. Responses from the undergraduates in Japan and Malaysia. (questions from Section 1 to Section 3, left to right).

Figure 7. Responses from the foreign workers in Japan and Malaysia. (questions from Section 1 to Section 3, left to right).

Table 6. Differences between nationalities in non-verbal materials.

The attitudes of the undergraduates from Japan and Malaysia are somehow different towards the concept of unsafe actions on site. For instant, about 80% of the Japanese students and 41% of Malaysian students “strongly disagree” to “No more crashes from scaffolding simply by wearing a safety belt”; 6% of Japanese students and 38% of Malaysian students agreed to the statement (S1–9). About 83% of the Japanese students and 47% of Malaysian students disagreed that carelessness is the only cause to injuries when cutting boards with cutters, yet, 28% of Malaysian students agreed to this situation (S1–11). Furthermore, 94% of the Japanese students and 59% of Malaysian students “strongly disagree” to “You should not wear a leather gloves when cutting boards with a cutter”; 25% of Malaysian students “strongly agree” to this situation (S2–14). About 43% of the Japanese students disagreed “the use of special tools can help to prevent injury”; while 40% of Japanese students and 97% of Malaysia students agreed to this situation (S2–18). Besides, all the Japanese students agreed that the materials stored in the safety corridor can lead to injury, while 63% of Malaysian students agreed to this situation (S3–15).

The findings discovered the different attitudes between the foreign workers who works in Malaysia and technical trainees who works in Japan. For instant, about 52% of foreign workers answered “strongly agree” to “It is alright to wear short trousers when working on the interiors” while only one technical trainee answered the same way; 89% of foreign workers and 27% of technical trainees answered “strongly agree” to “If you sweat a lot, it is good to work with a towel around your neck”. Under Section 2, foreign workers showed unsafe practices towards work at height where 67% and 89% of them answered “strongly agree” to “It is safe to work on the scaffold without hooking the safety belt” and “In scaffolding assembly work, it is not necessary to hook up safety belts if you are only moving the scaffold” respectively; while most of the technical trainees answered “strongly disagree” to both questions. Under Section 3, majority of the foreign workers’ responses “strongly agree” to “It is a waste of time to clean your work area afterwards” even have to work in the same place for tomorrow; while almost all the technical trainees answered oppositely.

1.7.3. Objective 3: differences between verbal and non-verbal materials by groups

The difference between Japanese undergraduates, postgraduates and foreign technical trainees in both training materials were found significant differences (p value<0.05) in different scenario questions. showed the differences between verbal and non-verbal materials among individual groups. Six questions were found significant differences under PPE, work at height and correct way to use tools among Japanese undergraduates; nine questions were found significant differences under three sections among Japanese postgraduates; and three questions were found significant differences under work at height among the foreign technical trainees. Malaysian undergraduates and foreign workers in Malaysia had no significant differences found in scenario questions for both training materials.

Table 7. Differences between verbal and non-verbal materials.

1.8. Summary of discussions

The above discussions focused on the objectives to discover: (1) Differences between Japanese and non-Japanese inexperienced personnel in Japan, (2) Differences between non-verbal materials among nationalities, and (3) Differences between verbal and non-verbal materials.

First, no significant differences can be identified between Japanese postgraduates and foreign technical trainees in Japan for either verbal or non-verbal materials, in particular, it can be assumed that there are no differences in non-verbal materials. The statistical analysis found no significant differences among most of the scenario questions between the Japanese postgraduates and the technical trainees in verbal and non-verbal materials, it can be specified that most of the inexperienced personnel own similar safety knowledge and attitudes towards the importance of PPE, work at height, the correct way to use tools, lifting operation and site cleanliness in construction sites regardless the training materials. The first objective was achieved as no differences in perceptions of safety and health using non-verbal materials between inexperienced persons in Japan could be identified.

Second, statistical evidence was found in the non-verbal material showing a significant difference in attitudes towards the scenario questions between Japanese and Malaysian undergraduates; also the foreign workers who works in Japan and Malaysia. Japanese students showed similar attitudes among themselves towards most of the scenario questions, it can be claimed that they own standard safety knowledge towards unsafe actions within the safety training contents. In contrast, the Malaysian students tend to be ambiguity by frequent answered of “somewhat agree” “somewhat disagree” and “neutral” in PPE and site cleanliness scenario questions where they might not have sufficient knowledge to recognize the unsafe actions on sites. Besides, the findings show a different safety culture between Japanese and Malaysian construction sites and different opinions among foreign workers. The foreign technical trainees are able to recognize the risks and know how to react correctly to avoid unsafe behaviour during working at site; while the foreign workers who work in Malaysian construction sites showed poor safety impressions as reflected from the scenario questions. All these unusual responses are reflecting the unsafe behaviour and poor working procedures in Malaysian construction sites, as the foreign workers in Malaysia have different perspective towards risk recognition and the potential behaviour react to the risks due to lack of safety training and low literacy level of education which is similar with the studies by Cheng and Wu (Citation2013). Therefore, it can be confirmed that there are differences in the perception of safety and health in different countries, and this was more apparent to the experiences than the inexperienced.

Last, there were slightly differences between verbal and non-verbal materials in few questions among Japanese undergraduates, postgraduates and technical trainees, and no significant differences found among the Malaysian undergraduates and foreign workers in Malaysia as it can be interpreted as they have same level of understanding of both materials. Based on the findings, the Japanese undergraduates understood the non-verbal materials better, while the Japanese postgraduates understood the verbal material better; there were only three questions identified differences among foreign technical trainees, it can be interpreted as insignificant differences for both training materials. Since the training materials used are produced in Japan, it can be assumed that the more safety and health knowledge Japanese people know about, the easier it will be to understand if it is presented clearly in language. It can be interpreted that there is no significant different between verbal and non-verbal materials for Malaysian undergraduates, foreign workers in Malaysia and Japan who participated in this experiment.

Overall, respondents who received non-verbal materials had similar attitudes towards scenarios as the non-verbalized materials provided a level of visual danger, providing the same level of understanding regardless of whether the learner has field work experiences. Arguably, the verbalized materials do clearly convey what needs to be said, however the respondents can only understand within the scope of the explanation and may not understand the content well enough to apply that knowledge (Arif et al. Citation2021) especially those without field experiences. On the other hand, the non-verbal materials were effectively improved unsafe actions among the undergraduates, while verbal materials worked well among inexperienced persons in Japan.

The majority of the safety training content is likely to be shared internationally, yet, some of the safety training contents may need to be customized due to the differences in national attitudes towards safety and health in their working environments. In the event if such customization, verbal materials are useful for native workforces while non-verbal materials will be useful for foreign workforces if there are language problems as there is no difference in understanding between verbal and non-verbal materials for foreign workers.

2. Conclusion

This study provides an early phase of viewpoint on the effectiveness of verbal and non-verbal safety training materials through a cross country experiment to determine the assessment between different nationalities and field experiences of students and foreign workers in Japan and Malaysia.

The findings show that majority of the construction workers and novices were able to provide positive performance towards safety issues regardless the safety training materials. Overall, there were insignificant differences for both training materials between inexperienced personnel in Japan, most of the Japanese students were able to show similar attitudes like the technical trainees towards most of the scenario questions in PPE and lifting operation and site cleanliness.

The results indicated differences between foreign workers in Japan and Malaysia that might due to different safety culture and working environment in both nations; the foreign workers in Malaysia who are under low literacy level and having language issues able to perform in the assessment after the non-verbalized training, therefore these issues can be eliminated by using non-verbalized training materials. Since, there is insignificant difference between verbal and non-verbal training materials among each individual groups, yet, the results found evidence for the superiority of non-verbal over verbal training materials, although the difference was small. The respondents who undergone non-verbalized materials scored higher than verbalized materials especially in work at height section. The results proven the non-verbal training was more effective in terms of providing a visual aid to standardize the impression of the safety contents which can resolve the problems such as language barriers and low level of literacy for foreign workers. It can be claimed that the non-verbal training material was more effective over a period of time especially in the context of work at height.

The study had limited sample respondents where it can be increased and expand construction workers of different nationalities in future; and the non-verbalized safety training materials used in the study were only focused on the fundamental safety knowledge in construction site that produced by Japan publisher according to the Japan construction context. In future research, non-verbal safety training content needs to be customized for hazardous situations on construction sites according to the safety culture in the host country, and workers are trained in a visual way to enhance the ability in risk recognition to achieve better learning effects and promote industry safety education regardless of nationality. Furthermore, a generalized non-verbal safety training approach that is not customized for a specific scenario but suitable for the customization of different scenarios can be further explored and developed in the future.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our special thanks of gratitude to the publisher, Planex, Japan for the video contents used in the experiment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tan Zi Yi

Tan Zi Yi is an academic staff member at the School of Engineering and Green Technology, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, Malaysia

Kazuya Shide

Shide Kazuya and Kanisawa Hirotake are both professors at the School of Architecture, Shibaura Institute of Technology (SIT), Japan

Hirotake Kanisawa

Shide Kazuya and Kanisawa Hirotake are both professors at the School of Architecture, Shibaura Institute of Technology (SIT), Japan

Naoto Mine

Mine Naoto is a professor at SIT Research Laboratory, Japan

Kazuki Otsu

Otsu Kazuki and Koga Yohei were master degree student at SIT School of Architecture

Yohei Koga

Otsu Kazuki and Koga Yohei were master degree student at SIT School of Architecture

Shunsuke Someya

Someya Shunsuke is a PhD student at SIT School of Architecture, Japan

References

- Abdul-Rahman, H., C. Wang, L. C. Wood, and S. F. Low. 2012. “Negative Impact Induced by Foreign Workers: Evidence in Malaysian Construction Sector.” Habitat International 36 (4): 433–443. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2012.03.002.

- Ahn, S., T. Kim, Y. J. Park, and J. M. Kim. 2020. “Improving Effectiveness of Safety Training at Construction Worksite Using 3D BIM Simulation.” Advances in Civil Engineering 2020: 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/2473138.

- Ajslev, J., E. L. Dastjerdi, J. Dyreborg, P. Kines, K. C. Jeschke, E. Sundstrup, M. D. Jakobsen, N. Fallentin, and L. L. Andersen. 2017. “Safety Climate and Accidents at Work: Cross-Sectional Study Among 15,000 Workers of the General Working Population.” Safety Science 91: 320–325. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2016.08.029.

- Al-Bayati, A. J., O. Abudayyeh, T. Fredericks, and S. E. Butt. 2017. “Managing Cultural Diversity at US Construction Sites: Hispanic workers’ Perspectives.” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 43 (9): 4017064. doi:10.1061/(asce)co.1943-7862.0001359.

- Arif, M., A. R. Nasir, M. J. Thaheem, and K. I. A. Khan. 2021. “ConSafe4all: A Framework for Language Friendly Safety Training Modules.” Safety Science 141 (May): 105329. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2021.105329.

- Başağa, H. B., B. A. Temel, M. Atasoy, and İ. Yıldırım. 2018. “A Study on the Effectiveness of Occupational Health and Safety Trainings of Construction Workers in Turkey.” Safety Science 110 (October 2017): 344–354. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2018.09.002.

- Baseline Survey Construction Report. 2015. “Health and Safety Attitudes and Behaviours in the New Zealand Workforce: A Survey of Workers and Employers.” Cross-Sector Report. (A report to WorkSafe New Zealand and Maritime New Zealand). April.

- Blanchard, P., and M. Simmering. 2014. “Training Delivery Methods.” Encyclopedia of Business. Accessed 5January2022. https://www.referenceforbusiness.com/management/Tr-Z/Training-Delivery-Methods.html

- BLR. 2014. “50 More Tips for More Effective Safety Training.” Special Report, Business & Legal Reports 2. https://simplifytraining.com/app/uploads/2016/04/50-more-safety-training-tips-TT.pdf

- Burke, M. J., R. O. Salvodor, K. Smith-Crowe, S. Chan-Serafin, S. Sonesh, and S. Sonesh. 2011. “The Dread Factor: How Hazards and Safety Training Influence Learning and Performance.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 96 (1): 46–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021838.

- Casey, T., N. Turner, X. Hu, and K. Bancroft. 2021. “Making Safety Training Stickier: A Richer Model of Safety Training Engagement and Transfer.” Journal of Safety Research 78: 303–313. doi:10.1016/j.jsr.2021.06.004.

- Cheng, C. W., and T. C. Wu. 2013. “An Investigation and Analysis of Major Accidents Involving Foreign Workers in Taiwan’s Manufacture and Construction Industries.” Safety Science 57: 223–235. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2013.02.008.

- Dai, J., and P. M. Goodrum. 2011. “Differences in Perspectives Regarding Labour Productivity Between Spanish and English-Speaking Craft Workers.” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 9: 689–697. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000329.

- Demirkesen, S., and D. Arditi. 2015. “Construction Safety Personnel’s Perceptions of Safety Training Practices.” International Journal of Project Management 33: 1160–1169. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.01.007.

- Department of Occupational Safety and Health (DOSH). 2016. “Occupational Safety and Health Master Plan (OSHMP) 2016-2020.” OSH Transformation-Preventive Culture. Accessed 3 August2020 https://www.dosh.gov.my/index.php/competent-person-form/occupational-health/new-resources/2873-occupational-safety-and-health-master-plan-2016-2020/file

- Esmaeili, B., and M. R. Hallowell. 2012. “Diffusion of Safety Innovations in the Construction Industry.” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 138 (8): 955–963. doi:10.1061/(asce)co.1943-7862.0000499.

- Evanoff, B., A. M. Dale, A. Zeringue, M. Fuchs, J. Gaal, H. J. Lipscomb, and V. Kaskutas. 2016. “Results of a Fall Prevention Educational Intervention for Residential Construction.” Safety Science 89: 301–307. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2016.06.019.

- Fang, D., and H. Wu. 2013. “Development of a Safety Culture Interaction (SCI) Model for Construction Projects.” Safety Science 57: 138–149. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2013.02.003.

- Forst, L., E. Ahonen, J. Zanoni, A. Holloway-Beth, M. Oschner, L. Kimmel, C. Martino, et al. 2013. “More Than Training: Community-Based Participatory Research to Reduce Injuries Among Hispanic Construction Workers.” American Journal of Industrial Medicine 56: 827–837. doi:10.1002/ajim.22187.

- Gao, Y., V. A. Gonzalez, and T. W. Yiu. 2019. “The Effectiveness of Traditional Tools and Computer-Aided Technologies for Health and Safety Training in the Construction Sector: A Systematic Review.” Computers & Education 138 (May): 101–115. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2019.05.003.

- GraphPad. 2022. “Choosing Between the Mann-Whitney and Kolmogorov-Smirnov Tests.” Accessed 15 January 2022. http://www.graphpas.com//guides/prism/latest/statistics/stat_choosing_between_the_mann-whit.htm

- Guo, H., Y. Yu, and M. Skitmore. 2017. “Visualization Technology-Based Construction Safety Management: A Review.” Automation in Construction 73: 135–144. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2016.10.004.

- Industrial Safety and Health Act. (1972).“Laws of Japan.“ Retrieved from https://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/en/laws/view/3440

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 2015. “Construction: A Hazardous Work.” Accessed 7 January2022. https://www.ilo.org/safework/areasofwork/hazardous-work/WCMS_356576/lang–en/index.htm

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 2021. “Safety and Health at Work.” Accessed 7 January2022 https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/safety-and-health-at-work/lang–en/index.htm

- Ismail, R., R. Palliyaguru, G. Karunasena, and N. A. Othman. 2018. “Health and Safety (H&S) Challenges Confronted by Foreign Workers in the Malaysian Construction Industry: A Background Study.” The 7th World Construction Symposium, July, Sri Lanka, 277–287. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326635913_Health_and_Safety_HS_Challenges_Confronted_by_Foreign_Workers_in_the_Malaysian_Construction_Industry_A_Background_Study

- Jaafar, M. H., K. Arifin, K. Aiyub, M. R. Razman, M. I. S. Ishak, and M. S. Samsurijan. 2017. “Occupational Safety and Health Management in the Construction Industry: A Review.” International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics (JOSE) 24: 493–506. doi:10.1080/10803548.2017.1366129.

- Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). 2021. “JICA Standard Safety Specification (JSSS).” Accessed 10February2022. https://www.jica.go.jp/english/our_work/types_of_assistance/c8h0vm00008zx0m8-att/jsss_01.pdf

- Jeschke, K. C., P. Kines, L. Rasmussen, L. P. S. Andersen, J. Dyreborg, J. Ajslev, A. Kabel, E. Jensen, and L. L. Andersen. 2017. “Process Evaluation of a Toolbox-Training Program for Construction Foremen in Denmark.” Safety Science 94: 152–160. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2017.01.010.

- Krzywinski, M., and N. Altman. 2014. “Nonparametric Tests.” Nature Methods 11: 467–468. Accessed 10 January 2022. https://www.nature.com/articles/nmeth.2937

- Li, X., W. Yi, H. L. Chi, X. Wang, and A. P. C. Chan. 2018. “A Critical Review of Virtual and Augmented Reality (VR/AR) Applications in Construction Safety.” Automation in Construction 86 (July 2016): 150–162. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2017.11.003.

- Mohammadi, A., M. Tavakolan, and Y. Khosravi. 2018. “Factors Influencing Safety Performance on Construction Projects: A Review.” Safety Science 109 (2018): 382–397. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2018.06.017.

- Nykänen, M., V. Puro, M. Tiikkaja, H. Kannisto, E. Lantto, F. Simpura, J. Uusitalo, et al. 2020. “Implementing and Evaluating Novel Safety Training Methods for Construction Sector Workers: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial.” Journal of Safety Research 75: 205–221. doi:10.1016/j.jsr.2020.09.015.

- OSH Statistics in Japan. 2020. “Japan Industrial Safety and Health Association (JISHA).” Accessed 10 January2022. https://www.jisha.or.jp/english/statistics/index.html

- Oswald, D., F. Wade, F. Sherratt, and S. D. Smith. 2019. “Communicating Health and Safety on a Multinational Construction Project: Challenges and Strategies.” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 145 (4): 04019017. doi:10.1061/(asce)co.1943-7862.0001634.

- Priyadarshani, K., G. Karunasena, and S. Jayasuriya. 2013. “Construction Safety Assessment Framework for Developing Countries: A Case Study of Sri Lanka.” Journal of Construction in Developing Countries 18 (1): 33–51.

- United Nations. 2022. “Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” Accessed 15February2022. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights#:~:text=Drafted%20by%20representatives%20with%20different,all%20peoples%20and%20all%20nations

- Vignoli, M., K. Nielsen, D. Guglielmi, M. G. Mariani, L. Patras, and J. M. Peirò. 2021. “Design of a Safety Training Package for Migrant Workers in the Construction Industry.” Safety Science 136 (January). doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2020.105124.

- Wallen, E. S., and K. B. Mulloy. 2006. “Computer-Based Training for Safety: Comparison Methods with Older and Younger Workers.” Journal of Safety Research 37 (5): 461–467. doi:10.1016/j.jsr.2006.08.003.

- Wang, Z., Z. Jiang, and A. Blackman. 2021. “Linking Emotional Intelligence to Safety Performance: The Roles of Situational Awareness and Safety Training.” Journal of Safety Research 78: 210–220. doi:10.1016/j.jsr.2021.06.005.

- Winge, S., E. Albrechtsen, and B. A. Mostue. 2019. “Causal Factors and Connections in Construction Accidents.” Safety Science 112 (October 2018): 130–141. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2018.10.015.

- ZujovicL., V. Kecojevic, and D. Bogunovic. 2021. “Interactive Mobile Equipment Safety Task-Training in Surface Mining.” International Journal of Mining Science and Technology 31 (4): 743–751. doi:10.1016/j.ijmst.2021.05.011.

Appendix

*Construction accident rate is the number of accident represented a total number of casualties of 4 days or more on leave as determined from the Report of Worker Casualties that submitted by the business operator to the Labour Standard Inspection Office Under its jurisdiction. The accident rate is the estimated number of fatal and injured victims (4 days or more off) per 1,000 workers per year; while the fatal rate is the estimated number of fatal accident victims per 100,000 workers in a year.