ABSTRACT

Form-based codes (FBCs) pursue alternative built environments that integrate design-focused approaches for the purpose of fostering predictable development outcomes. The emphasis of FBCs on legitimate building types and physical parameters may provide local authorities with new opportunities to incent a variety of sustainable design features. Despite the code’s recent popularity in urban infill and suburban retrofit projects, little research exists to explain the expected benefits of form-based approaches. This study evaluates the evolution of FBCs across diverse cities by relating a range of geographical scales to differing contextual conditions. Focusing on five FBCs adopted in the United States between 2010 and 2015, building and street design elements are analyzed to investigate the linkages between development context and built outcomes. This study supplements prior research on design coding by demonstrating that the local and metropolitan contexts of FBCs can help explain how placemaking goals may be achieved. The typology framework presented in this paper also serves as a minimum set of standards for reconciling the public’s expectation for amenities with the private sector’s willingness to contribute their resources to the local built environment.

1. Introduction

Form-based codes (FBCs) pursue alternative built environments that integrate design-focused approaches intended to complement conventional zoning with the goal of fostering predictable development outcomes. FBCs prescribe how urban streetscapes should appear and often present those prescriptions graphically. These characteristics arise in reaction to Euclidean zoning, a reaction itself to the perceived nuisances and blight of industrialization (Moga Citation2017). One user’s nuisance is another’s opportunity, and Planned Unit Development and Performance-Based zoning attempt to accommodate exceptions within the Euclidean paradigm (David Citation2015). But exception runs counter to the purpose of zoning: to provide urban predictability. FBCs resolve this tension by reconceptualizing predictability with a built-up form as opposed to appropriate use or the absence of nuisance. Because FBCs are concerned with how the built environment appears, they lend themselves to illustration. When users consult FBCs, alongside or instead of legal text, they see for themselves what the built future may look like.

The emphasis of FBCs on legitimate building types and physical parameters, in lieu of permitted uses, may provide local authorities with new opportunities to incent a variety of sustainable design features (Cortesão et al. Citation2020). Proponents suggest that FBCs have the potential to improve neighborhood walkability and enhance local character (Jabareen Citation2006). Critics point out that FBCs unnecessarily increase project design costs and fail to create meaningfully distinctive products (Rangwala Citation2013). As a result, FBCs have been widely adopted, particularly in thriving regions where strong market demand tends to overcome any performance drags caused by additional form-based regulations and their costs. The high real estate demand makes preconditions, which increase demands on development projects for facade, frontage, and building-type requirements, a reasonable negotiation for policymakers. These mandatory built results can be attainable within the private developer’s return goals in strong market cities.

Extra design standards, however, are likely to cause regulator anxiety when weighing the benefits of FBCs against the costs they impose on development projects. This issue has unique significance in weaker development markets, where FBCs can discourage design intervention behaviors that anticipate sustainable built outcomes such as urban infill or suburban retrofit to blend in with the existing local context. On the other hand, FBCs may compensate for these added project costs by reducing regulatory uncertainty emerging from the design review process required for multi-use projects. When properly designed by FBCs, by-right approval reduces the risk of a costly prolonged delay for investors and project managers. For this reason, the extent to which codes can flexibly approve a variety of project types impacts a code’s overall ability to deliver the outcomes of diversity and amenity promised in an FBC’s design vision for the community.

This study intends to explore this issue, in which the claims of FBC proponents meet the challenges of inherent development conditions. Little research has explored the usefulness of FBCs, particularly in struggling regions such as legacy cities. Existing research on the expected rewards of form-based approaches is strong in theory (eg, Talen Citation2013) but weak in evaluation, especially for currently operating individual programs. This study will supplement recent work by assessing the justifications of FBCs in a diverse range of development contexts. Unlike previous research, which explored the mechanism of a selective FBC to achieve desired results and did not differentiate between design codes, the study will evaluate the evolution of FBCs in differing market conditions. This study first reviews the potential benefits of FBCs that are being examined in the literature, which will then inform criteria used for case selection. Characterizing five FBCs adopted in the United States. between 2010 and 2015, building and street design elements are analyzed to investigate the linkages between development context and built outcomes.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature on sustainable built environments and FBCs. Section 3 describes the data collection process with study area selection criteria and the case study research design. The subsequent section presents the results. Section 5 presents a case study to investigate the impact of FBCs on property values. Section 6 discusses the FBC typology choices of this study and their policy implications, and the last section offers some concluding comments.

2. Background and previous research

2.1. Sustainable built environments and design interventions

Design strategies are useful for translating a myriad of development ideas into practice. In response to the overcrowding of the Industrial Revolution, the Garden City suggested a new relationship between cities and surrounding towns (Howard Citation1965). The Radiant City characterized the desire for space, smarter transportation, and modernized construction techniques for a Europe on the brink of post-industrialization. From the 1920s onward, Traditional Neighborhood Units grew in demand for compact housing amidst the emergence of sprawled suburban neighborhoods in the United States (Perry Citation1929). These concepts were used at various points in history to communicate ideas about urban form, which allowed these ideas to then be realized into practice.

The movement for sustainable development has sparked discussions about the role of the built environment in encouraging a more sustainable lifestyle. Increasingly, the built environment is proposed as part of a comprehensive strategy for building and supporting sustainable communities. Jabareen (Citation2006) outlines a number of popular movements exploring the role of urban design in sustainable development, including Neotraditional Development, Urban Containment, and the Compact City, for their varying applications in density, mobility, and diversity as tools for better living. More recently, Larco (Citation2016) discussed the need for a more universal definition of sustainable urban design, which includes the notions of compactness and walkability as well as natural resource conservation in a general framework that can be applied across each of these movements. The multifaceted goals of economic, environmental, and social justice in sustainable development manifest in a diverse range of urban design approaches (Grover, Emmitt, and Copping Citation2020).

Current approaches to implementing sustainable design intervention ideas, which are primarily market-driven, yield mixed conclusions about the effectiveness of the design-focused strategy (Markley Citation2018). As an example, New Urbanism proposes a package of design features, which, together, can create more attractive and socially cohesive neighborhoods. Because they base implementation around the profit motive of developers, applications of sustainable design principles are subject to cost considerations and perceptions of individual developers (Darko and Chan Citation2017). The promise of financial capital on investment motivates interest in New Urbanism projects (Mayo and Ellis Citation2009), but in cases where demand for certain features is questionable or would significantly increase project costs, privately driven approaches focusing on acquiring financial capital in the market can result in inconsistent applications of intended techniques (Song et al. Citation2017).

Public-driven implementation tools can supplement the limitations of a market-based approach (Allouf, Martel, and March Citation2020). Public approaches like reformed land use regulations can support a fuller application of sustainable design by removing barriers to mixed use development, increased building density, and mandating standards for streetscape (Wang, Krstikj, and Koura Citation2021; Heris, Middel, and Muller Citation2020). Regulatory tools have been developed to complement New Urbanism practices. Whereas Euclidean land use regulations have maintained the regime of suburban sprawl at the expense of pedestrian scale and walkable environments, new techniques take steps to encourage the walkable environments described in the Charter of the New Urbanism (Leccese and McCormick Citation1999).

FBC is one such approach codifying the built environment features of sustainable neighborhood design. FBCs, similarly to Euclidean land use controls, use the police power of the state to regulate land use and development patterns for the protection of the public’s general welfare. They apply restrictions on shape, bulk, and use of structures to ensure a more attractive environment that is more consistent with the goals of walkability and diversity inherent in New Urbanism (Sitkowski and Ohm Citation2006). Coding tools have historically drawn on a professional consensus about what is a desirable urban form (Alfasi Citation2018), and as such are of interest in new applications as planners consider the role of urban design in creating more sustainable neighborhoods (Stanislav and Chin Citation2019).

FBCs, more specifically, may be conducive to stimulating this form of walkable, mixed-use development by permitting a greater variety of land use options for adaptive built environments (Cozzolino Citation2020). FBCs can allow for a greater diversity of permitted uses, under the expectation that built form requirements will restrict certain incompatible uses as necessary. Hughen and Read (Citation2017) explore this claim in a real option model of FBCs, encouraging land use flexibility. In their research, the model is used to evaluate the cost of adaptive reuse of buildings in form-based, mixed-use districts with respect to comparable cases in more restricted zones, exploring whether the benefits of easy reuse of an adaptable structure, such as ground-floor commercial property, outweighed the potential for building massive, single-use complexes such as apartment blocks. Their model implies that the adaptive reuse opportunity provided by a mixed-use FBC is beneficial to developers even in weaker real estate markets. These findings suggest the need for further research exploring the benefits and challenges an FBC might face in different market contexts to evaluate its usefulness for implementing sustainable development ideas.

2.2. Form-based codes and contextual conditions

Early research on FBCs was initiated by legal scholars (Barry Citation2008; Geller Citation2010; Woodward Citation2013) who defended FBCs as a tool for promoting urban planning yet remained skeptical of their chances of dethroning Euclidian regulations (Inniss Citation2007; Garvin and Jourdan Citation2008). More recent scholarships have tended to explore the design coding effect, but much of this research is limited to narrative reviews and theoretical models. Talen (Citation2013) praises FBCs as a means of replicating historic development patterns degraded by Euclidean zoning, but remains silent regarding FBCs as a tool for mending urban fabrics. Moroni and Lorini (Citation2017) abstract FBCs from the planning process entirely to appreciate their “graphic rules,” while Hughen and Read (Citation2017) model the potential value of FBCs for facilitating mixed-use development.

Several studies have examined the impact FBCs can have on the built environment with selected case studies. These researchers employ different approaches to build on the planning consensus that FBCs can improve local development capacity by enhancing walkability (Hansen Citation2014) or increasing density (Talen Citation2013). Others compare FBCs to conventional zoning approaches for the codification of denser and more sustainable urban design (eg, Garde, Kim, and Tsai Citation2015). While these studies make useful contributions to the justification for FBCs as sensible, sustainable land use reform, they do little to connect these claims to built outcomes. Only Hansen (Citation2014) evaluates the walkability of streets in several forms but uses urban design features as a proxy for walkability. None of the published research explores the relationship between sample codes and changes in development behavior, thus limiting the ability for policymakers to argue in favor of these views.

The literature has also focused on cases in growing Western and Southern metropolitan areas in the United States. The analyzed samples codify design standards for new construction in regions that have experienced positive population growth within the last decade. For instance, the City of Miami, Florida, situates an ever-expanding population against the Atlantic coast and Everglades National Park, and its codes are written to accommodate a further increase within the same geographic area (Garde, Kim, and Tsai Citation2015). In a strong development context, where development can be expected with relative certainty, codification of design standards that increase project cost may not be as great a risk as it would be in a weaker metropolitan area. In cases where small differences in project cost can mean the life or death of a project, FBCs and other reforms of the development process are often criticized. As such, the rationale for adopting an FBC will vary depending on the development context, but this aspect of code writing has been underexplored in the literature.

3. Methods and data

Comparison of cases addressing the issue of sustainable built outcomes in different market contexts enables a richer understanding of the use of FBCs. The case study approach is appropriate to collate multiple cases and account for variance (Yin Citation2017) when characterizing cases to conduct a side-by-side analysis. FBCs cover a diversity of development contexts, ranging from rural towns focused on main street redevelopment to central city neighborhoods emphasizing the promotion of development capacity. Focusing on codes with a common set of features but under different development expectations allows for discussion of how codes in diverse environments use a comparable ensemble of regulatory features (building typology, height restrictions, and regulating plan area). This additionally enables consideration of marked differences in code structure, such as the use of street design standards for the public realm at the municipal level. To account for the variety of existing coding practices, FBC adoption cases in the United States between 2010 and 2015 were collected and compiled from the Codes Study (Borys, Talen, and Lambert Citation2019), which is the most comprehensive data set on active FBCs that meet criteria established by the Form-Based Codes Institute. An overview of criteria considered in case selection follows. Based on these criteria, five codes were considered appropriate and selected for further comparison ().

Form-based features: Codes selected contained a minimum threshold of regulatory features specific to land use and building design guidelines. The form-based approach contrasts use-based Euclidean zoning with a stronger emphasis on site planning, shape, and bulk standards, and architectural elements. As such, case comparison is focused specifically on these features, including building types, height, material, frontage, and block design. In addition, FBCs often apply urban design standards through the creation of a regulating plan, which can be used to interpret the spatial intentions behind code drafting decisions, such as use restrictions and building heights. In sum, case comparison was limited to codes which, at minimum, shared the use of three features common across form based codes: A building typology, building height permissions, and an available regulating plan.

Population: When considering comparable cases of form-based zoning ordinances, we first considered metropolitan and host city context. For example, the Central West End FBC covers a centrally located, mixed-use neighborhood in St. Louis, MO, a city of 317,850 situated in a metropolitan area of approximately 2.8 million in 2015. At this scale, leveraging the development capacity of one neighborhood against other districts in the same region has become central to the purpose of the code’s drafting. While FBCs may use similar tools to encourage better design outcomes, codes in smaller cities may not be as focused on enhancing capacity to attract large projects. Selected codes targeted neighborhoods in cities where total population exceeded 300,000 in 2010.

Development Context: We then considered the context of metropolitan development that might influence the priorities of local ordinances. Code elements, such as permitted building heights, may be employed differently, to maintain building densities in the case of 2–3 story maximums common in residential areas or to increase densities in the case of 2–3 story height minimums in centrally located urban neighborhoods. Expectations of population growth can motivate the creation of FBCs to different ends: To control population growth, on the one hand, or to stimulate creation of new space on the other. To capture the various uses of FBCs in different development contexts, cases were selected from diverse regions and growth trends as measured by 2000 and 2010 Decennial Census figures. Selections ranged from St. Louis, MO (−8%) to Forth Worth, TX (+27%). With this distinction between codes covering growing and declining urban areas, we were able to discuss potential relationships between metropolitan context, code structure, and built outcomes. Codes were selected to reflect a variety of development expectations, from positive population growth in both the host city and host metro, to negative population in the city and metro.

Table 1. Case Selection Criteria.

4. Results

4.1. Building design

FBCs typically use a combination of permitted typology of buildings and frontages, which are more design specific, as well as traditional tools, such as permitted use and building height restrictions (Usui Citation2021). At minimum, permitted use types in FBCs enable flexibility through a wider variety of land uses within districts. Residential districts can be expanded to include retail uses to meet the needs of the district’s residents at higher concentrations. Conversely, office and residential uses can be added primarily to commercial districts in central city downtowns, adding flexibility for developers to respond to changing market trends (Ariga Citation2005).

Building and frontage typologies moderate the externalities of this expanded use diversity by ensuring more consistent, pedestrian-friendly urban design. Their controls for building type, material, and street front reduce the risk of disharmonious neighboring projects, or of disruption of a walking corridor, limiting people’s willingness to patronize neighborhood retailers. Finally, more aggressive building height restrictions are sometimes used to maintain or increase the block-level density of these projects, reducing the risk of new retail services not having a sufficient, built-in concentration of customers. In different combinations, codes use these tools to create a regulatory environment that can facilitate neighborhood-supportive and participatory developments (Boehme and Warsewa Citation2017).

4.1.1. Building types

Building type regulations can illustrate divergent approaches to promoting land use diversity and neighborhood amenity. The use of building typologies to regulate land use is a unique feature of FBCs, specifying bulk and site planning requirements for new construction. While permitted land uses can be one measure of land use diversity, enabling the integration of residential, commercial, and office uses at the parcel level, permitted building types represent a more distinct approach to block level diversity. Podium building is one such example, which may house a variety of uses enabled by greater parcel-level use flexibility. Building typologies used in various codes in the study favor a variety of dominantly detached housing types in most residential areas, which may be architecturally diverse but functionally consistent. These alternative approaches to “flexibility” in building style illustrate a potential contrast with conventional land use regulations. On the one hand, parcel-level flexibility may allow for innovation of development product types and enhance responsiveness to the real estate market. On the other hand, diverse permitted land uses at the parcel level may encourage the same kinds of mixed-use, midrise development types, allowing few opportunities to respond to the ever-evolving demands for new building types. Examination of permitted building types can illustrate different strategies used to reduce burdens on the creation of mixed-use projects and neighborhoods.

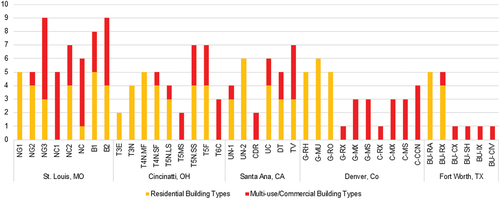

The building types are handled more flexibly in the St. Louis’ Central West End Form-Based District (FBD) compared to other codes reviewed (see ). The Central West End FBD enables a greater amount of building-type diversity, defined as the integration of residential and mixed-commercial building types in one or more districts, aiming for more flexible development types at the block level. Other codes, like the City of Fort Worth FBC, enable parcel-level land use flexibility in its mixed commercial areas, creating some opportunities for the integration of residential space, but few opportunities for integrating multiunit housing and mixed-commercial properties on the same block. Similarly, the Denver Revised Municipal Code (RMC) enables parcel-level mixed use development, but more tightly controls building types allowed at the block level.

Cincinnati takes a comparable approach, disallowing mixed-commercial building types in the majority of its residential districts but permitting residential building types in its commercial and center city neighborhood types. The Central West End FBD alone features integration of residential and mixed-commercial building types across the majority of its districts. Greater flexibility in choice of building type may reflect a greater perceived opportunity cost between tighter land use control, on the one hand, and more diverse building options on the other in weak market cities, making flexible, loose development control a more attractive option to code framers.

The extent to which diverse building options are enabled by code is an important complement to the general presence of mixed-use permissions. Diverse housing and commercial building options while establishing consistent design standards are also products of the desire to enable new development activity through the creation of a code, rather than guiding projects that are already expected. Only the Central West End FBD integrates four different residential building types into 60% or more of their districts (). In St. Louis, this includes mostly multi-unit residential buildings like duplex-fourplexes, townhomes, courtyard buildings, and stacked flats, compared to multifamily buildings and duplexes in the Fort Worth code. Similarly, only courtyard buildings and tuck-under buildings are integrated into 60% or more of Santa Ana’s districts. In terms of both building types described and the frequency of these types throughout its districts, the St. Louis FBD enables more diverse building options than other codes. This further suggests its intention to stimulate the creation of new mixed-use projects.

4.1.2. Building height

Building height restrictions can reflect different expectations of development pressure in a neighborhood (see ). Building heights more traditionally limit development density in lower intensity, predominantly residential areas. In these areas, building height restrictions preserve environmental quality and neighborhood character by preventing construction of disharmonious, high-intensity projects, typically predicated on the expectation that development pressure will otherwise drive up project height. In these cases, height restrictions of existing ordinances can be amended to accommodate and even encourage such building density; however, merely loosening height restrictions may be less effective in other markets.

In weaker real estate markets, demand for new construction may be less robust and therefore produce development patterns at lower densities than previously anticipated. Codes that cover centrally located neighborhoods may use height restrictions to instead mandate stricter minimum building heights, requiring new construction to be built to historic levels, and preserving existing densities and concentrations for residential users. Such minimum height restrictions are useful in weak market areas to drive up project density, where code framers find appropriate. The use of height restrictions, to either passively encourage or actively drive densification, demonstrates the contrast between code features intended to improve neighborhood aesthetics and ones that augment existing development capacities.

In this way, the Central West End FBD explicitly encourages density. The codes’ introduction includes explicit commitments to “maintain the smaller scale residential areas within the core of the area while simultaneously ensuring higher density development at the edges of the area” (City of St. Louis Citation2013, 6). Structurally, the code is unique in its use of minimum heights; in all districts, a minimum of at least two stories is established for all new construction projects, requiring new development that is consistent with the character of existing residential areas (see NG1, NC2 in ) while encouraging greater density along major corridors (see NC1 in ).

Figure 3. Built outcomes of Neighborhood Center Type 1 (NC1) on Euclid Avenue in St. Louis (adopted in 2013).

Additionally, maximum heights applied in the code are generally more permissive than comparable codes in Santa Ana and certain Denver neighborhood contexts (). Only the Berry/University FBC in Fort Worth articulates a similar goal, but in requiring denser housing options and uniform building heights in a low-density residential neighborhood. While the Central West End code uses permitted building heights to increase density in mixed-commercial structures, the Berry/University FBD mandates increased residential density through the use of height restrictions as well as the unique use of attached single-family dwelling standards in residential areas. Although this may be owed to the lack of specific target planning areas on which to base new density requirements in other codes reviewed, the consistent application of minimum height standards is one of the clearest reflections of the redevelopment intent of the Central West End FBD.

4.2. Street design

Streetscape features are a critical component to mixed-use development standards common in FBCs. While FBCs use building typologies to control the externalities of expanded neighborhood use flexibility, character is ultimately maintained by codes’ regulations for facade and street design. Public realm enhancements, such as sidewalk improvements and better block design, support the walkability of these development patterns (Mezoued, Letesson, and Kaufmann Citation2021), while facade design standards applied through building types enrich the character and attractiveness of these areas. Leveraging the public sector’s control over transportation right of ways to complement the pedestrian-friendly project types incented by FBCs can be an impactful approach to achieving walkability goals. Neighborhood businesses supported by the integration of residential and neighborhood-serving commercial project types depend on quick, comfortable access to residents of neighborhoods (Mohamed and van Ham Citation2022).

Design standards for the public realm face different challenges than regulations for private development. Because they require buy-in from both the public and private sectors, streetscape standards can be contentious additions (McLeod and Curtis Citation2019) to FBCs. At the parcel level, private sector features like encroachments for street frontages, material choices, and frontage allowances are common components of FBCs that define the street environment; provisions for block level, publicly financed design features like sidewalk landscaping or transit-accessible streets are less prolific. Although the benefits of better street design are appreciated across market contexts, street design improvements that require no public sector investment can be more attractive in weak market areas. Standards for the public realm, for which public works departments are responsible, may be less attractive under constrained municipal budgets. In this way, the tradeoffs between public investments and return for infrastructure upgrades illustrate a contrast between form-based approaches in different markets. The willingness to leverage public resources in an FBC characterizes differences in development expectations, thereby having the potential to heavily influence the composition and implementation of an FBC.

4.2.1. Frontage

FBCs use frontage and encroachment requirements to coordinate how buildings meet the street by adding street-serving design features. Frontage requirements, which control the percentage of a building that must be built to a designated distance from the street, create a more consistent street front in which structures engage the sidewalk in a uniform way. Lower frontage requirements allow for a larger percentage of the building facade to deviate from the build-to line, creating more site planning flexibility and less street connection in more residential areas. Conversely, frontage with higher requirements, which brings more of a building’s facade to the build-to line, encourages the kind of shopfront atmosphere associated with walkable and mixed-use neighborhoods. At the build-to line, a typology of features that are permitted to encroach on the setback line are typically provided, allowing street-serving design elements like planters and cafes to define the pedestrian right of way (Soni and Soni Citation2016). When build-to frontage is less strict, the ability for encroachment permissions to affect street design is diminished, so the strength of a code’s frontage requirements is an important means by which FBCs provide more street serving, private design features.

Although the frontage requirements of FBCs are often similar, they diverge in code structure. Codes organize frontage requirements by either building or district type, or both. The manner in which a building meets the build-to line is an important aspect of architectural design, and applies a great deal of instruction to the use of building typologies to control land use, as discussed previously. Codes drafted for specific neighborhood geographies, like the Central West End FBD and the Santa Ana Renaissance Transit Zoning District (RTZD), organize frontage requirements by building type. Similarly, codes designed to cover a variety of neighborhood types like the Cincinnati FBC as well as comprehensive zoning ordinances like the Denver RMC, which must organize land use and density at a larger scale, define frontage requirement by district, augmenting streetscape controls applied to building types in different districts (Denver) or for all building types within one district (Cincinnati). “General” type buildings in Denver’s S-MS-5 district must build 75% of its primarily facade to the lot line, while only 60% in S-MS-2. Comparable “Midrise” buildings in the Central West End FBD must build 80% of its facade to the lot line in all applicable districts. Although measurable differences in build-to line requirements were not easily observed between development codes, differences in code structure corresponding to the importance of the code’s building typology may point to differences in codes’ metropolitan development context.

Encroachments and facade standards enhance street environments created by different build-to line standards, adding street-serving features and architectural detailing that makes the public realm a more comfortable place for conducting daily business. These features are more consistently specific to building typologies, which include standards for encroachments, materiality, and fenestration, organized by building type in most codes observed. Features permitted to encroach on the public right of way allow forecourts, balconies, stools, and galleries to connect pedestrians and users to the public realm. St. Louis’s Central West End FBD includes a list of permitted frontage types which may encroach the build-to line, including porches, stoops, bay windows, and awnings, which are further enhanced by material choice and glazing standards for ground floor retailers. Other codes that cover, or must apply to, a larger geographic area, such as the Denver RMC and the Cincinnati FBC, do not specify material choices. Similarly, not all codes reviewed provided standards for ground floor glazing for new construction of midrise projects.

4.2.2. Street pattern

Codes take more divergent approaches to addressing the public right of way as a part of the street realm. The cost of facade design and building massing, which characterize streets at the parcel level (Harvey et al. Citation2017), is absorbed by private developers, while various improvements to street pattern and design must be publicly financed. Justification of these measures can be difficult in public agencies where budgets are strained. Plans to improve walkability may involve the alteration of existing roads or the construction of new ones, which would be coordinated by public works agencies. Lower impact strategies may use infrastructure funding to improve the quality of existing streets through sidewalk upgrades, landscaping, and signage improvements. Additionally, the street environment that enhances multimodal neighborhood access supports the amenities created by updated form-based development regulations. Municipalities’ ability to provide the necessary services, however, is constrained by public perceptions of the metropolitan development climate.

Street typologies are the primary organizing structure for right-of-way improvements. Codes that provided public realm improvements, such as the Santa Ana RTZD and the Cincinnati FBC, organize them around a street typology and integrate them into regulating plans just as building typologies discussed previously. Street typologies are employed differently between neighborhood-specific and scalable codes. Codes written for specific geographies, such as the Santa Ana RTZD and the Denver RMC, organize streets with respect to a regulating plan. For example, the Santa Ana RTZD organizes streets by type (eg, Boulevard) and direction (eg, Existing – Remove) to prioritize the location and nature of plan-based street improvements. Conversely, codes written for regulating neighborhood plans outline a method of defining transect districts for new regulating plans organizing street types and public space improvements by transect zone (Duany and Talen Citation2002). The Cincinnati FBC outlines a network of thoroughfares to guide regulating plans based on project volume and landscaping of existing streets ranging from “Major Thoroughfares” to “Alley.” The structuring of these different typologies can then enable different improvements to public space design.

Geographic specificity influences the degree of infrastructure improvement enabled by different codes. While codes designed to enable the creation of regulating plans use street typologies to organize sidewalk and signage improvements, codes that were framed for specific areas expanded to include changes to the uses and layout of specific streets. Less geographically specific codes such as the Cincinnati FBC were less descriptive of the infrastructure improvements that a regulating plan might make, providing sidewalk design and landscape standards to be employed by public works in different transect districts and thoroughfare type, but not making recommendations for road use and layout alterations. Neighborhood-specific codes such as the Denver RMC and the Santa Ana RTZD prioritized improvements for specific streets. As an example, the plan suggests the addition of a transit and bike land along Santa Ana Blvd., while suggesting landscaping of select parking spaces in another section along Lacey St. This most starkly contrasts the Central West End FBD, which was written specific to the as-built conditions of streets in the Central West End neighborhood, but makes no provisions for either streetscape design or the addition of new roads. Without local readiness to publicly finance urban design, street design standards in FBCs are scarce.

5. Case study

This case study explores the usefulness of FBCs in weak market cities for stimulating new investments in real estate. The hypothesis that the CWE FBD improved the neighborhood’s development capacity assumes some amount of change in investment behavior over time with respect to the code’s adoption in 2013 and so should be observable both in the CWE compared to peer neighborhoods and in investment behavior within the CWE. Patterns in investment, in terms of “assessed land value,” “assessed improvements,” and “appraised land value” are observed from 2010 to 2016, covering the FBD’s planning from 2011 to 2013 and adoption in 2013.

The Central West End FBD is one of the few ordinances to be written for a central city neighborhood in a large, shrinking rust belt city in the United States. As such, it provides a unique opportunity to study the implications of FBCs for facilitating reinvestment and infill development in declining metros, where all land use regulations are sensitive to the costs imposed on the development process. The hypothesis is backed by the body of literature suggesting that people are willing to pay for walkable, mixed-use urban living, and investment in these projects is held up more by neighborhood-level risk factors than a lack of developer interest. This analysis will add to the growing literature on form-based design coding by observing the impact of the FBD on investment behavior.

5.1. Neighborhood context surrounding the form-based district

St. Louis’s CWE neighborhood is a regional center for medical and technological services. Bound by Delmar, Vandeventer, and DeBaliviere Place/Forest Park to the west, the CWE covers regional anchors like Barnes Jewish Hospital, the Washington University Medical Center, St. Louis Children’s Hospital, and Shriner’s Hospital for Children. In addition to a spectrum of healthcare service providers, the Central West End neighborhood covers the Cortex Innovation District, a clustering of information and technology firms and entrepreneurship support services created in 2002. The combined influences of the healthcare services and technology innovation activities hosted by the Central West End has spilled over into a variety of neighborhood amenities, including the creation of new housing, restaurant space, and retail services. As the competitiveness of these institutions for workers depends in part on local quality of life, anchor institutions have taken an active interest in the development of neighborhood assets.

The CWE FBD is one part of this strategy. The code amends the general zoning ordinance of the City of St. Louis to permit a greater level of unit density and use flexibility by right in the development review process. It is designed specifically to increase residential density, especially along arterial corridors like Forest Park, Lindell, Kingshighway, and Vandeventer. This density supports the addition of ground floor retail amenities, which, in turn, add to the quality of neighborhood life and the competitiveness of local institutions. In particular, in the district along Euclid, the desire for mixed residential-commercial midrise projects is plain in the language of “establish, preserve, and enhance the vibrant, pedestrian oriented character of these walkable neighborhood main streets (p. 3–15, City of St. Louis Citation2013)” north of the Washington University Medical Center campus. Drafted by H3 Studios and Park Central Development, an arm of the Washington University Medical Center Redevelopment Corporation, the code reduces barriers to neighborhood-enriching mixed-use development projects. It provides for the stable infill of the neighborhood’s housing inventory, minimizing disruption in the center of the district while maximizing density along edge corridors.

The CWE competes with a number of neighborhoods for new residents and subsequent investment. Comparison of peer neighborhoods, which may have comparable assets in terms of housing stock, neighborhood retailers, and proximity to the health science and technology innovation clusters of the CWE will enable performance comparison, assessing the extent to which a form-based zoning ordinance may have unlocked new investment capacity in the neighborhood with respect to competing neighborhoods.

To understand the contribution of the FBD to development activity within the CWE, this study compares assets of the FBD with respect to features of surrounding CWE submarkets. Submarkets were defined along neighborhood corridors, which included Kingshighway, Olive, Lindell, and Forest Park, to produce five submarkets: Cortex, Cathedral, Olive, Kingshighway, and the FBD in question. The influence of land use mix and the investment behaviors of large, individual institutions compared to the functioning of the real estate market will be considered in order to better understand the potential impact of the FBD specifically on redevelopment activity.

Even within the CWE, the FBD is unique in its land use diversity and development capacity. While other submarkets feature stronger concentrations of residential and commercial properties, the FBD covers the most even share of land uses in the neighborhood. The FBD covers 225 acres (626 parcels) directly north of the Washington University Medical Center campus, Barnes Jewish Hospital, and Cortex Innovation Districts, adding residential and neighborhood retail amenities to the institutions’ predominantly commercial/industrial impact area. For example, the FBD contains 25% of all residential properties in the CWE. Although a smaller share than the Kingshighway (27%) and Cathedral (34%) submarkets, the residential component of the FBD is serviced by a larger share of commercial users (34%) than either the Kingshighway (13%) or Cathedral submarkets (15%). Lindell, Kingshighway, Forest Park, and Vandeventer bound this FBD with corridors of high intensity, mixed-residential, -commercial, and – office uses, framing a neighborhood of mixed detached and multi-unit residential properties with dense, midrise apartments and office buildings. Proximity to anchor institutions, in addition to neighborhood retail services, drives higher property values on average throughout the FBD’s residential ($477,635/acre), commercial ($607,682/acre), and industrial ($324,154/acre) stock, all of which command correspondingly a low rate of vacancy. As a result, redevelopment activities within the district are likely to accelerate at a greater rate than in other parts of the CWE neighborhood.

5.2. Property value impact assessment

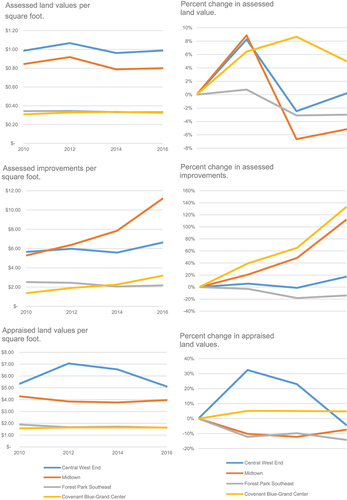

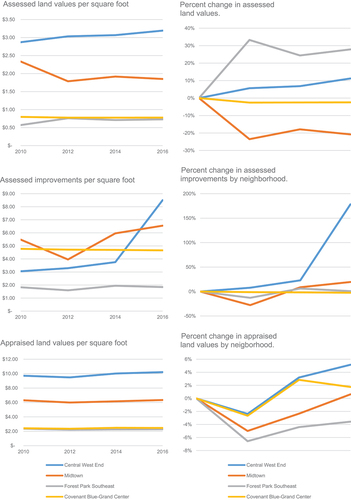

This property value impact assessment demonstrates that CWE outpaces Midtown in terms of assessed and appraised land value/sf (See ). Midtown continued to outpace the CWE for value of property improvements over the sample period, but this may still be attributable to improvements being made on Saint Louis University’s Frost Campus over the same range. When controlling for land use, Midtown outperformed the CWE in assessed improvements, which measure rehabilitation and building additions per year (4). However, the CWE surpassed Midtown in new investments in non-residential property over the same period, with a significant acceleration between 2014 and 2016 ().

The CWE outperformed all other submarkets in non-residential property values (). This is to be expected considering increased interest in the neighborhood by investors in recent years over comparable locations in other parts of the Central Corridor, especially over competing residential clusters in Forest Park Southeast and Covenant Blue Grand Center. Base assessments of land value were higher on average than comparable neighborhoods and rose at a greater rate, apart from Forest Park Southeast. In terms of improvement activity, the CWE outpaced peer neighborhoods between 2014 and 2016, although it began the sample period receiving fewer new investments on average. Land appraisals remained steady in the neighborhoods, with little change between 2010 and 2016.

Trends in residential land values were inconclusive (). Because residential decisions are driven by a different set of factors than non-residential investments, trends in this data may not be as responsive to the implementation of an FBC or any short-term changes in location advantage of certain neighborhoods. In terms of assessed and appraised land values, the CWE outperformed peer neighborhoods, although it depreciated significantly in appraised values between 2012 and 2016. Conversely, residential properties in Midtown saw the most improvements on average over the same period. In addition, Forest Park Southeast outpaced the Central West End for rate of improvements and appreciation in assessed land value over the same period.

6. Discussion

6.1. Code structure and typology

Code structure is primarily guided by the design objectives of individual cities (). Although FBCs are rooted in the New Urbanist tradition of valuing mixed-use neighborhood development and aiming for increased foot traffic, codes in different neighborhood contexts may apply different approaches to encourage more connected, diverse built environments. For instance, an FBC created to encourage more walkable street design in greenfield neighborhood sites may employ platting and subdivision standards, street and block design standards, and architectural standards for a variety of residential building types. These features may be less emphasized by codes designed for denser, more mixed-use city neighborhoods to reflect the existing layout of streets, lots, and project types. While FBCs deploy similar tools such as the combination of building and street typology, specific uses of each tool for infill or greenfield neighborhood development are informed by the needs of distinct cities and neighborhoods.

Table 2. Code Comparison.

FBCs used in this study relate a variety of geographical scales to differing local contexts. Some codes reviewed, like the Central West End FBD and the Santa Ana RTZD, covered one discrete neighborhood with specific boundaries and architectural precedents. Other codes, namely the City of Cincinnati FBC, provide a framework of street and land use typologies to support the creation of neighborhood level plans throughout the city. Regulating plans can be one way of inferring the priorities of these less specific codes. For example, although the Cincinnati FBC is written for widespread application to different neighborhoods, the regulating plans available predominantly cover greenfield sites near the city limits. It provides land use and street design standards that could cover a variety of urban and exurban sites, but this may indicate the code’s primary function has been to guide the development of new residential neighborhoods. Conversely, explicit neighborhood boundaries in the Central West End FBD and Santa Ana RTZD informed code features more applicable to higher density project types in central city neighborhoods. The Berry/University FBD in Fort Worth, TX, takes a similar approach, providing denser housing options by right and integrated residential-commercial uses along its main boulevard, but with the intention of up-zoning a low intensity residential area. The geography of codes’ regulating plans as well as their relationships to each regulating plan was considered when framing each case.

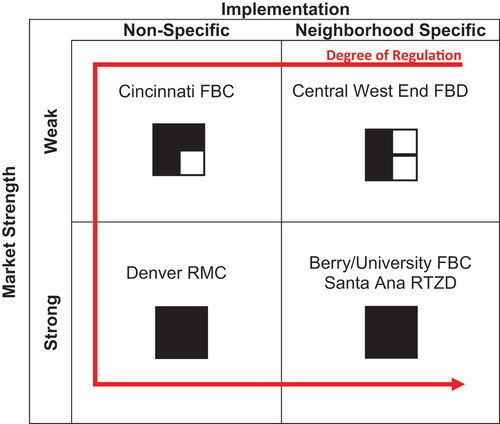

One means of comparing FBCs across these contexts is by contrasting the objects of regulation: public versus private elements regulated individually or contextually (see ). Further points of comparison are offered by the neighborhood specificity of each plan and the relative development market strength in each city. illustrates a categorization of regulatory tools FBCs offer across public and private sector development by degree of design scope. As each quadrant may be regulated independently of the others, adopted FBCs express local appetites for urban design, enriching individual elements for private development or contextual elements for public infrastructure.

Filling in the matrix based on the tools adopted in a given FBC yields a graphic representation of the city’s regulatory “style” as seen in inset, . Note that “style” here is a characterization of the tools adopted by an FBC rather than a measure of the strength or efficacy of those tools. Four solid quadrants, as depicted for the Denver RMC, Berry-University FBD, and Santa Ana RTZD, indicate code that regulates public and private elements at both an individual and contextual level. In contrast, the Central West End FBD eschews regulation of public elements at an individual and contextual level, thus leaving two quadrants blank.

further places these four quadrant diagrams on axes of market strength and neighborhood specificity in implementation. Both Denver and Cincinnati have adopted non-specific FBCs, but Denver did so in the context of a relatively strong development market, while Cincinnati did so in the face of a weaker market. Immediately apparent from this diagram is greater willingness of cities with strong development markets to regulate across all four combinations of design scope and formal elements, suggesting regulation of public elements entails costs which cities in weak markets are unwilling or unable to bear. suggests that weak market cities believe regulation of private elements offers a greater return (new development) on investment (regulatory cost) than regulation of public elements. Regardless of market strength, cities seek an optimal rather than maximum implementation of FBCs. However, a consensus definition of optimized code remains elusive. The elements/design scope matrix in offers one starting point for this definition as cities select tools from each quadrant based on their goals and market conditions.

6.2. Economic impact of form-based code

The case study findings in St. Louis may suggest that the FBD improved the capacity for investment in the CWE’s non-residential property. Assessed and appraised land values increased at a greater rate inside than outside of the FBD, particularly in the years following the code’s adoption. Continued property improvements persisted between 2010 and 2016 at a steady rate in the district and accelerated outside as interest in properties to the north increased. This contrasts relatively static improvement activities occurring in Forest Park Southeast and Covenant Blue Grand Center, as well as unstable property improvements in Midtown, over the same period. Given that commercial investment behavior is more flexible and responsive to place-based initiatives, such as the creation of an FBC, the acceleration of non-residential investment in the FBD may support the economic impact of FBC.

Conversely, residential investment patterns (rehabilitations, new unit construction) do not seem to have been significantly impacted by the creation of the FBC, and changes appear to reflect existing advantages of the area around the FBD over properties in the north and south CWE. Patterns in residential investment behavior were stable over the sample period.

Some evidence indicates that the CWE FBD may have improved perceptions of the district for investment in non-residential properties, potentially due to the presence of a community-supported plan or increased capacity to approve mixed use development projects, but the tax assessment data evidencing this are far from conclusive. Increased rates of investment and appraisal in the FBD may reflect a pattern of property value appreciation that was occurring in the neighborhood predating the FBD; it could also reflect the disproportionate use of other development incentives, such as Tax Increment Financing and tax abatement, to improve development conditions in the FBD compared to surrounding residential and commercial properties.

To understand the challenges and motivations behind form-based coding in practice, an executive developer and a community development planner were interviewed from the stakeholder group involved in CWE FBD development. The semi-structured interviews as additional sources provided insight into the elements of creating an FBC initiative in the context of the adopted city. The developer observed that, through completing a mixed-use development at a corner of the two major arterial roads in the FBD, his company has learned a positive value of the code hinged on the flexibility it provided in commercial, office, and residential uses, and the clearer review process it established in approving mixed use projects. The by-right review process is the most important benefit of an FBC for developers, so the extent to which it can reduce approval demands on a project will define its usefulness for weak market cities. Faster processing and minimization of subjectivity in the review process is a crucial component for the private sector.

Responding to this benefit, the public sector interviewee explained that form-based coding intends to reduce the uncertainty in the built outcomes that can be developed in an effort to concretize the community’s vision. For instance, the planner described how the community group leaders initiated the FBD:

The idea behind the code was let’s involve a public process to create a vision for the future, an overall vision, and then codify that vision. The form-base code was the way to say. This is what legally be allowed based on what the community wants. There was a huge public engagement process.

According to the two interviewees, the participatory engagement process in the course of the code adoption includes both the public and private sectors in addition to community members. This pre-established guiding principle has allowed developers and investors to leverage their assets, while mitigating risks and uncertainty in the design review process (Kim Citation2020).

Further research should expand our understanding of the code’s impact on the perceptions of FBD investment for different stakeholders, including brokers, developers, planners, and residents. This qualitative inquiry should be supplemented by an exploration of the use of tax incentives in the CWE over a sample period to understand the relationships between these benefits, investment activity, and the FBC. Additionally, the case study provided explanations for the influences on property values, but such influences warrant further research on how the adoption of FBCs affects socioeconomic aspects of the neighborhoods (Talen Citation2021).

6.3. Policy implications

FBCs offer struggling cities valuable flexibility in adapting their regulatory regime to their development goals. In St. Louis’ case as an example, a unique minimum-building height regulation enabled the city to institute a density floor for new development. While increased height maximums are often promoted as a means of unleashing suppressed demand for higher density, St. Louis lacked the necessary demand and therefore supplemented with regulations that curtail future low-density development. Height minimums under Euclidean zoning might result in a surplus of unused commercial space, but FBCs address this concern by allowing for adaptive use of buildings adhering to the city’s design guidelines. In this way, FBCs acknowledge their inability to predict a city’s future and provide affordances for meeting future challenges.

However, FBCs face unavoidable hurdles as tools for stimulating development in the public realm. Design standards for the public sector are less likely to find support when facing tight budgets. Without the support of public works departments, FBCs are likely to either narrow in scope or remain optional. Another challenge to FBCs is their limited applicability to other urban challenges, such as low population growth rates, demographic shifts, and housing affordability. In fact, densification is already attainable within Euclidean zoning. Thus, the utility of FBCs may ultimately be determined by the presence or absence of opportunities to reform existing non-form-based regulations.

Cities seeking the highest return of new development on regulatory cost from FBCs must ask which form-based elements are necessary and relevant to their goals. For example, FBC complexity increases with geographic area and the resultant increased diversity of land uses. Conversely, FBCs become more targeted and therefore more capable of regulating desired elements of the streetscape when restricted to smaller areas. Within a given neighborhood or transit district, the target population is also important. Aging populations may be best served by walkability design elements. Weak market cities should be especially cognizant of the resources required to implement code changes. While FBCs have the potential to be more comprehensible than Euclidean regulations, reducing the need for staff consultations with developers, this advantage may be offset if an FBC regulates more elements than its Euclidean predecessor. Finally, cities should be conscious that FBCs promoting redevelopment face more inertia against their desired outcomes than codes regulating greenfield. The large number of stakeholders in established cities underscores the expediency of small area FBCs.

7. Conclusions

This study supplements prior research on design coding by demonstrating that the local and metropolitan contexts of FBCs can help explain how placemaking goals will be achieved in each instance. The first contribution of this paper is to present an analytical framework sharing the view that FBCs offer cities a tool for meeting design and development goals. Such goals, however, are unique to each city and may include redevelopment under weak market conditions in addition to environmental sustainability. The present research makes explicit what the studied cities have intuitively understood: FBCs offer a value proposition not previously considered by scholarship. The second contribution is to investigate what the adopted FBCs actually entailed and inform policymakers and regulatory authorities considering form-based strategies. In short, FBCs do not only affect private investors and developers. A comprehensive FBC regulating public elements requires buy-in from a range of public works officials responsible for individual elements within a streetscape.

The built environments of neighborhoods and cities have evolved with the changing demands of residents and so do the codes to control them with each new iteration. FBCs have been an increasingly preferred approach of many cities to enable more sustainable and coordinated development driven by design. The use of typologies to organize the application of urban design standards in different contexts was common across the codes sampled. Typologies of buildings, frontages, roofs, streets, and public spaces categorized diverse code components which reflected the objectives of code writers. Codes regulated the built environment at different scales, from the block scale to the municipality level, using a variety of tools from material choices on individual buildings to the street grids that support neighborhood redesign. The scale at which codes addressed their development objectives is crucial for understanding how development context may have affected the negotiation of trade-offs between conflicting priorities (Dell’anna and Dell’ovo Citation2022) in the code implementation process. The typology framework presented in this paper serves as a benchmark or a minimum set of tools for reconciling the public’s expectation for amenities with the private sector’s willingness to contribute their resources to the local built environment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jae Teuk Chin

Jae Teuk Chin is an associate professor in the International School of Urban Sciences at the University of Seoul.

References

- Alfasi, N. 2018. “The Coding Turn in Urban Planning: Could It Remedy the Essential Drawbacks of Planning?” Planning Theory 17 (3): 375–395. doi:10.1177/1473095217716206.

- Allouf, D., A. Martel, and A. March. 2020. “Discretion versus Prescription: Assessing the Spatial Impact of Design Regulations in Apartments in Australia.” Environment & Planning B: Urban Analytics & City Science 47 (7): 1260–1278. doi:10.1177/2399808318825273.

- Ariga, T. 2005. “Morphology, Sustainable Evolution of Inner-Urban Neighborhoods in San Francisco.” Journal of Asian Architecture & Building Engineering 4 (1): 143–150. doi:10.3130/jaabe.4.143.

- Barry, J. M. 2008. “Form-Based Codes: Measured Success Through Both Mandatory and Optional Implementation.” Connecticut Law Review 41 (1): 305–337.

- Boehme, R., and G. Warsewa. 2017. “Urban Improvement Districts as New Form of Local Governance.” Urban Research & Practice 10 (3): 247–266. doi:10.1080/17535069.2016.1212087.

- Borys, H., E. Talen, and M. Lambert 2019. The Codes Study. Retrieved from http://www.placemakers.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Codes-Study_June-2019.htm.

- City of St. Louis. 2013. Central West End Form-Based District (Ordinance 69406). St. Louis, MO.

- Cortesão, J., S. Lenzholzer, J. Mülder, L. Klok, C. Jacobs, and J. Kluck. 2020. “Visual Guidelines for Climate-Responsive Urban Design.” Sustainable Cities and Society 60: 102245. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2020.102245.

- Cozzolino, S. 2020. “The (Anti) Adaptive Neighbourhoods. Embracing Complexity and Distribution of Design Control in the Ordinary Built Environment.” Environment & Planning B: Urban Analytics & City Science 47 (2): 203–219. doi:10.1177/2399808319857451.

- Darko, A., and A. P. C. Chan. 2017. “Review of Barriers to Green Building Adoption.” Sustainable Development 25 (3): 167–179. doi:10.1002/sd.1651.

- David, N. P. 2015. “Factors Affecting Planned Unit Development Implementation.” Planning Practice & Research 30 (4): 393–409. doi:10.1080/02697459.2015.1015832.

- Dell’anna, F., and M. Dell’ovo. 2022. “A Stakeholder-Based Approach Managing Conflictual Values in Urban Design Processes. The Case of an Open Prison in Barcelona.” Land Use Policy 114: 105934. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105934.

- Duany, A., and E. Talen. 2002. “Transect Planning.” Journal of the American Planning Association 68 (3): 245–266. doi:10.1080/01944360208976271.

- Garde, A., C. Kim, and O. Tsai. 2015. “Differences Between Miami’s Form Based Code and Traditional Zoning Code in Integrating Planning Principles.” Journal of the American Planning Association 81 (1): 46–66. doi:10.1080/01944363.2015.1043137.

- Garvin, E., and D. Jourdan. 2008. “Through the Looking Glass: Analyzing the Potential Legal Challenges to Form-Based Codes.” Journal of Land Use & Environmental Law 23 (2): 395–421.

- Geller, R. S. 2010. “The Legality of Form-Based Codes.” Journal of Land Use 26 (1): 35–91.

- Grover, R., S. Emmitt, and A. Copping. 2020. “Trends in Sustainable Architectural Design in the United Kingdom: A Delphi Study.” Sustainable Development 28 (4): 880–896. doi:10.1002/sd.2043.

- Hansen, G. 2014. “Design for Healthy Communities: The Potential of Form-Based Codes to Create Walkable Urban Streets.” Journal of Urban Design 19 (2): 151–170. doi:10.1080/13574809.2013.870466.

- Harvey, C., L. Aultman-Hall, A. Troy, and S. E. Hurley. 2017. “Streetscape Skeleton Measurement and Classification.” Environment & Planning B: Urban Analytics & City Science 44 (4): 668–692. doi:10.1177/0265813515624688.

- Heris, M. P., A. Middel, and B. Muller. 2020. “Impacts of Form and Design Policies on Urban Microclimate: Assessment of Zoning and Design Guideline Choices in Urban Redevelopment Projects.” Landscape and Urban Planning 202: 103870. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103870.

- Howard, E. 1965. Garden Cities of To-Morrow. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Hughen, W. K., and D. C. Read. 2017. “Analyzing Form-Based Zoning’s Potential to Stimulate Mixed-Use Development in Different Economic Environments.” Land Use Policy 61 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.11.010.

- Inniss, L. B. 2007. “Back to the Future: Is Form-Based Code an Efficacious Tool for Shaping Modern Civic Life.” University of Pennsylvania Journal of Law and Social Change 11: 75.

- Jabareen, Y. R. 2006. “Sustainable Urban Forms: Their Typologies, Models, and Concepts.” Journal of Planning Education & Research 26: 38–52. doi:10.1177/0739456X05285119.

- Kim, M. 2020. “Negotiation or Schedule-Based? Examining the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Public Benefit Exaction Strategies of Boston and Seattle.” Journal of the American Planning Association 86: 208–221. doi:10.1080/01944363.2019.1691040.

- Larco, N. 2016. “Sustainable Urban Design – a (Draft) Framework.” Journal of Urban Design 21 (1): 1–29.

- Leccese, M., and K. McCormick. 1999. Charter of the New Urbanism. First ed. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Markley, S. N. 2018. “New Urbanism and Race: An Analysis of Neighborhood Racial Change in Suburban Atlanta.” Journal of Urban Affairs 40 (8): 1115–1131. doi:10.1080/07352166.2018.1454818.

- Mayo, J. M., and C. Ellis. 2009. “Capitalist Dynamics and New Urbanist Principles: Junctures and Disjunctures in Project Development.” Journal of Urbanism 2 (3): 237–257. doi:10.1080/17549170903466061.

- McLeod, S., and C. Curtis. 2019. “Contested Urban Streets: Place, Traffic and Governance Conflicts of Potential Activity Corridors.” Cities 88: 222–234. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2018.11.002.

- Mezoued, A. M., Q. Letesson, and V. Kaufmann. 2021. “Making the Slow Metropolis by Designing Walkability: A Methodology for the Evaluation of Public Space Design and Prioritizing Pedestrian Mobility.” Urban Research & Practice 15 (4): 1–20. doi:10.1080/17535069.2021.1875038.

- Moga, S. T. 2017. “The Zoning Map and American City Form.” Journal of Planning Education & Research 37 (3): 271–285. doi:10.1177/0739456X16654277.

- Mohamed, A. A., and M. van Ham. 2022. “Street Network and Home-Based Business Patterns in Cairo’s Informal Areas.” Land Use Policy 115: 106010. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106010.

- Moroni, S., and G. Lorini. 2017. “Graphic Rules in Planning: A Critical Exploration of Normative Drawings Starting from Zoning Maps and Form-Based Codes.” Planning Theory 16 (3): 318–338. doi:10.1177/1473095216656389.

- Perry, C. A. 1929. The Neighborhood Unit, a Scheme of Arrangement for the Family-Life community: Published as Monograph 1 in Vol. 7 of Regional Plan of N.Y. Regional survey of N.Y. and its environs, 1929.

- Rangwala, K. 2013. Assessing criticisms of form-based codes. Retrieved from http://bettercities.net/article/assessing-criticisms-form-based-codes-19967

- Sitkowski, R. J., and B. W. Ohm. 2006. “Form-Based Land Development Regulations.” Urban Lawyer 38: 163–172.

- Song, Y., M. R. Stevens, J. Gao, P. R. Berke, and Y. Chen. 2017. “An Examination of Early New Urbanist Developments in the United States: Where are They Located and Why?” Cities 61: 128–135. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2016.08.013.

- Soni, N., and N. Soni. 2016. “Benefits of Pedestrianization and Warrants to Pedestrianize an Area.” Land Use Policy 57: 139–150. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.05.009.

- Stanislav, A., and J. T. Chin. 2019. “Evaluating Livability and Perceived Values of Sustainable Neighborhood Design: New Urbanism and Original Urban Suburbs.” Sustainable Cities and Society 47: 101517. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2019.101517.

- Talen, E. 2013. “Zoning for and Against Sprawl: The Case for Form-Based Codes.” Journal of Urban Design 18 (2): 175–200. doi:10.1080/13574809.2013.772883.

- Talen, E. 2021. “The Socio-Economic Context of Form-Based Codes.” Landscape and Urban Planning 214: 104182. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104182.

- Usui, H. 2021. “Building Height Distribution Under Zoning Regulations: Theoretical Derivation Based on Allometric Scaling Analysis and Application to Harmonise Building Heights.” Environment & Planning B: Urban Analytics & City Science 48 (9): 2520–2535. doi:10.1177/2399808320977867.

- Wang, M., A. Krstikj, and H. Koura. 2021. “The Potential of Special Zone Development as a Tool in Land-Use Control—A Case Study of Yinchuan City, Western China.” Journal of Asian Architecture & Building Engineering 20 (4): 477–491. doi:10.1080/13467581.2020.1799797.

- Woodward, K. A. 2013. “Form Over Use: Form-Based Codes and the Challenge of Existing Development.” The Notre Dame Law Review 88 (5): 2627–2655.

- Yin, R. K. 2017. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. 6th ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE.