ABSTRACT

This study explores the rich spatial-cultural phenomena of street skateboarding and graffiti in Jakarta. The enduring appeal of both activities lies in their ability to inspire creativity, foster subcultural identities, and leave a lasting impact on culture. Through interviews and detailed observations by the first author, an active skateboarder, the research investigates the motivations, challenges, and cultural significance of skateboarding and graffiti. It examines their appropriation of urban spaces, exploring how they navigate local norms and regulations. The study also uncovers the social dynamics and subcultural communities that have emerged around these activities, shedding light on their role in shaping individual and collective identities within Jakarta’s urban fabric. The findings highlight the positive responses from the surrounding community, the strong attachment of the youths to their preferred locations, their constant adaptation and development of skills, and how they express their unique identities.

1. Introduction

Abundant books and journals are exposed to academic analyses across disciplines on skateboarding and graffiti. The enduring nature of skateboarding and graffiti as topics arise from their ability to inspire creativity, foster subcultural identities, undergo constant evolution, and leave a lasting impact on culture (Borden Citation2019; McDuie-Ra and Campbell, Citation2022; Ross Citation2016; Shwartz and Mualam Citation2022; Willing and Pappalardo Citation2023; Wooley and Johns Citation2001). These factors contribute to their timeless appeal and ongoing relevance. Some scholars focused on deep implications of skateboarding to the meaning and nature of public space which is constantly produced, reproduced, negotiated and reconfigured such as Németh (Citation2006) and Wooley and Johns (Citation2001) while others highlighted the “self-expression, artistic, and non-conformist” subcultures as the core attraction for graffiti (Ross Citation2016). Skateboarding allows individuals to showcase their unique style, tricks, and maneuvers (Borden Citation2019), while graffiti offers a canvas for artists to communicate messages and visually transform public spaces (Mcauliffe Citation2012; Mubi Brighenti Citation2010; Raposo Citation2023; Snyder Citation2017).

The ability of street-skateboarders and graffiti writers to establish a communication network throughout cities worldwide is remarkable. They are made aware of actions and circumstances within their circle through exploring the city, word of mouth, and social networking sites. According to Goodfellow (Newsware Citation2020), both skateboarders and writers view their practice through its impact on body consciousness and the perspective on the city, making them the most reliant actors on the existing elements of the city. Ong (Citation2016) suggests that these place performances demonstrate the potential for outcomes initially perceived as impossible.

Although graffiti and skateboarding occur in diverse physical locations, the use of urban space is still the same since appropriation has occurred. The theory of appropriation formulated by Gibson (Citation1986) offers insights into the connections between skateboarding, graffiti, and the active reimagining and adaptation of the urban environment. Both activities involve the appropriation of space, creative expression, subversion, and individual agency, aligning with the central ideas of Gibson’s theory. During play, writers and skateboarders interact with urban areas by transforming them into canvases and surfing areas. Skateboarding and graffiti depict how young people create permanent and temporary urban space appropriations. It is temporary since it does not have its own space, and it stands out from preceding techniques because it leaves a “mark” on the existing urban elements. Youth actions in street skateboarding and graffiti are often perceived as illegal due to the destruction of city property; therefore, the possibility of being arrested is their primary concern. Street skateboarding possesses a transformative power that significantly influences urban elements (Borden Citation2019). The presence of scratches, burrs, marks left by the wheels, and traces of paint and wax assert skateboarding as an act of vandalism. Graffiti often causes physical damage, including scratches, paint marks, or other forms of defacement that can be costly to repair or restore.

Writers prefer to draw strict boundaries between their daily life (Snyder Citation2017), while skateboarders may turn skateboarding into a highly unconventional motion (Karsten and Pel Citation2000); this results in their tendency to ignore rules to demonstrate their commitment to escape the monotony of everyday life. Furthermore, young people often appear addicted to activities that fuel their adrenaline and creativity, despite being increasingly drawn into the act, causing them to disregard any hazards (United Nations Dept of Economic and Social Affairs Citation2005). Street skateboarding and graffiti are broad topics that encompass various techniques, settings, and interpretations. They can be classified as play since they have a flexible purpose. Lefebvre (Citation1974) believed that youth culture, with its subversive and experimental nature, has the potential to transform the urban landscape. He saw play and leisure activities, including skateboarding and graffiti, as forms of resistance against the rigid structures of society. These activities allow young people to reclaim urban spaces and create alternative, autonomous realms. Lefebvre emphasized the significance of the lived experiences of youth in shaping urban space.

2. Problem statement

Nowadays, through the internet, globalized and commercialized images of skateboarding have intersected with bodies, spaces, and media histories (Borden Citation2019; McDuie-Ra Citation2022a, Citation2022b; Citation2023), resulting in the simultaneous transformation of the Americanized vision of teenagers worldwide. These dynamics have contributed to creating the so call “global youth imaginary” (Woodman and Bennett Citation2015) where the relationship between youth and urban space is represented and frozen through image and video production. With their solid subcultural history (Glenney and Mull Citation2018; Goodfellow Citation2016; Hollett and Vivoni Citation2021; Merrill Citation2015; Pugh Citation2015), skateboarding dan graffiti effectively symbolizes youth and urban space, making them a powerful and energizing element in shaping this collective imagination.

In Indonesia, the proliferation of Instagram, TikTok, YouTube and Twitter content created by Indonesian youth and teenagers is a testament to the vibrant visual culture surrounding skateboarding and graffiti in the country. Both are documented and highlighted through DIY photography and videography to emphasize a distinctive manifestation of creativity. Since skateboarding often thrives in public spaces as an impromptu playground, while graffiti serves as an act of reclaiming public space, discussing both activities in Indonesian cities is intriguing.

Skateboarding and graffiti provide a lens through which we can view public spaces’ vibrant, dynamic, and complex realities along the typical street fontanges and sidewalks in Indonesian cities. Ongoing rapid urban growth in the country often outpaces the ability of local governments to manage and plan for the expansion of cities effectively. As a result, infrastructure development and maintenance often fall behind, leading to crowded, chaotic, and poorly maintained sidewalks. They display uneven, filled with potholes, or obstructed by parked vehicles, making them difficult to navigate. Variety of activities along the sidewalks beyond just walking, such as social gatherings, cooking, selling goods, parking motorcycles, or even extensions of private businesses, become typical sights. Along the street corridors, the line between public and private space is blurred, and the use of public space is often communal. This cultural difference contributes to a vibrant but often messy street life.

However, Jakarta, along with many other contemporary cities in Indonesia, faces the challenge of cultivating a modern urban image characterized by cleanliness, aesthetic beauty, and orderliness. Jakarta is also facing the challenge of transitioning from a car-oriented city to one that prioritizes pedestrians that drastically transform the sidewalks. Since 2016, a significant effort has been made to address this transformation by embarking on a massive construction project to revitalize sidewalks in some prominent areas. Initially, 48 km of sidewalks were constructed, with a targeted expansion to reach 97 km by 2020 (Mulyadi et al. Citation2022). Despite Jakarta spanning an area of 661.5 square kilometers, the reach of pedestrian revitalization is confined to just a small fraction of the city, resulting in the physical condition of sidewalks and frontages in Jakarta varying significantly. Some areas may have well-maintained, wide sidewalks, while others remain narrow, uneven, or blocked by parked vehicles, construction, and informal street vendors (See ).

The sidewalk improvement project in Jakarta signifies how the city portrays democracy, political power, and legitimacy. Aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the government is actively striving to establish public spaces that are safe, inclusive, and easily accessible. However, this poses a significant challenge as the government concurrently needs to uphold the orderly appearance and aesthetic value of the pedestrian areas, which were laboriously revitalized. To employ a certain image of order and prosperity, Jakarta set up an apparatus of the Civil Service Police Unit officers called Satpol PP (Satuan Polisi Pamong Praja). Their primary responsibility is to maintain public order and peace of society through enforcing regional regulations and administering public order and public security (Suhartanto et al. Citation2021).

This study aims to comprehensively explore the practice of skateboarding and graffiti in the context of Jakarta. By delving into the local scene and engaging with performers, this research sheds light on how skateboarding and graffiti are manifested and experienced in the city. It investigates how participants navigate local norms, regulations, and perceptions and how these practices shape individual and collective identities within the city’s urban fabric. The questions raised to be answered: What aspects of the city’s physical environment do skateboarders and graffiti artists appropriate and transform to accommodate their practices? What social dynamics and subcultural communities have emerged around skateboarding and graffiti in Jakarta?

3. Overview of skateboarding in Jakarta

Who would have thought that skateboarding started as a mere fad? In the 1921s, scooter-like riding emerged as a wooden-wheeled slide controlled by a handlebar. Over time, an axle that pivots around a rubber pivot cup (like the truck for skateboarding today) supports the wheels and the board, enabling skateboard users the same feeling as surfing (Marcus and Daniella Griggi Citation2011). In 1978, Alan Gelfand or Ollie recorded history when he performed an “ollie” or a hands-free areal trick where he and his board leap into the air. After Ollie, countless new and popular invention of tricks has shaped skateboarding as vibrant culture. Throughout the ups and downs of its popularity, skateboarding has grown into an exciting sport and thrilling to watch (Borden Citation2019; O’Connor Citation2018; Wooley and Johns Citation2001). Skateboarding has gained immense popularity worldwide, with numerous well-known athletes and organized national and international competitions, including the Olympics (Borden Citation2019; Branch Citation2021; Goodfellow Citation2016; O’Connor Citation2018).

Skateboarding was introduced to Indonesia in 1976, primarily by expatriates in Jakarta and elite youths who attended schools in the United States. Initially, a few teenagers who lived at “Menteng” (the elite housing area in Jakarta) became enthralled with this extreme activity, but they mostly followed the trend without pursuing it seriously. Due to the scarcity of skateboards, only individuals with serious intentions could fully engage in this sport. Information about skateboarding was extremely limited during this period. An ex-skateboarder mentioned that in 1982, he learned about the sport through Transworld Skateboarding magazine, which he obtained by asking his friend to bring it from Singapore. Since skateboarding was still uncommon in those days, skateboarders could perform in front of security officer without being immediately expelled.

In the 1990s, the skateboarding world experienced a decline as a new, more popular sport emerged (Kilberth et al. Citation2019). However, in Indonesia, the televised X-Games played a crucial role in expanding the exposure of skateboarding. In major cities, this sports trend aligned with music, fashion, and lifestyle movements, inspired by Indonesian musicians who became idols among the youth through their music videos (Nurhayadi Citation2006). In 1999 the construction of the first skatepark in Senayan, Jakarta, marked the positive developments of skateboarding in many big cities throughout Indonesia. At that time, skateboarding in Indonesia is not for everyone’s consumption; it has evolved into a sought-after lifestyle among the middle class, spanning various age groups from 4 to 35 years old. The establishment of the Green Skateboard Lesson skateboard school in Jakarta aimed to cater to the desires of middle-class parents who recognize that skateboarding not only develops physical strength but also enhances concentration and focus for their children (Parenting Citation2019).

The popularity of skateboarding surged in 1999 with the formation of the Indonesian Skateboarding Association or ISA (Akbar Citation2010) encouraged skateboarding begun to consider one of the so-called extreme sports and boast a range of competitions. When entering the realm of competition, skateboarding becomes a highly technical event that requires balance, agility, and speed. In 2018 skateboarding was included in Asian Games held in Jakarta and Palembang, two years ahead of its debut as an Olympic sport in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. Nevertheless, as skateboarding from western entered Indonesia at the different stages, rather than as a sporting discourse, skateboarding is often associated with contemporary fashion. The hype of “extreme sports” represents the commodification of skateboarding to become a signifier of “lifestyle” in the display windows of many fashion stores. The surge of “action” sports shows on the internet has transformed skateboarding into more than just a catalyst and reference for extreme sports. It has also become a significant factor in street fashion, becoming a marketing vocabulary that resonates with the youth demographic group. Various local brands have emerged, offering skater-style products such as jackets, shirts, pants, and shoes, catering to the growing demand. These brands have capitalized on the popularity of skateboarding culture, providing fashion options that resonate with skaters and enthusiasts alike. Aligned with McDuie-Ra (Citation2021) skateboarding has gone through waves of co-option by actors considered “outside” the culture and higher value commodities such as shoes and clothing consumed beyond skateboarding communities. Interestingly, many of these consumer goods are produced by former skateboarding community members two decades ago who now become fashion entrepreneurs. To market their products, they often engage in a mutually beneficial relationship with professional skaters, providing support for products and salaries.

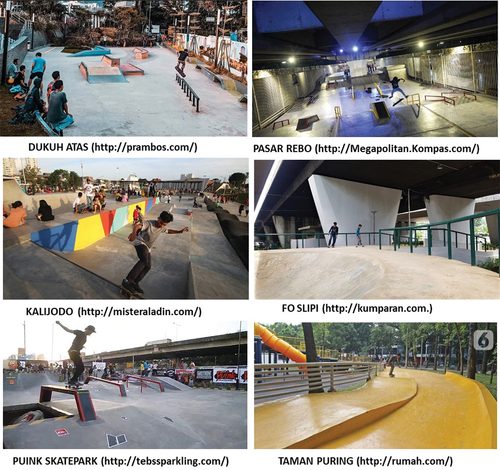

As an exhilarating extreme sport, skateboarding showcases elements of speed, height, danger, and brave actions that require courage (Donnelly Citation2006). Skateboarders rely on their skill and creativity to perform various styles, which evoke emotional sensations such as joy, fear, and excitement (Seifert and Hedderson Citation2010). In line with skateparks’ trend, some skateparks in Indonesia offer opportunities for Vert‘s (vertical) play, which emphasizes style and aesthetics. Various skateparks provide platforms for skateboarders to practice and enhance their skills designed into open flow bowls and seascapes of wave-like ridable terrain. Standard obstacles like mini ramps, half pipes, banked ramps, flat rails, pools, handrails, quarter pipes, curb bowls, down rails, and pyramids (Seifert and Hedderson Citation2010) are provided. The Ollie trick revolutionized skateboarding and is the foundation for new tricks and variations, whether in freestyle, slalom, downhill, long jump, or zig-zag styles (Karsten and Pel Citation2000). These styles eventually evolved into Street-Skateboarding, where skateboarders utilized public spaces as a canvas for performing tricks. In Jakarta, young skateboarders train in several skateparks built by the government for free. These include skateparks at Dukuh Atas, Pasar Rebo, FO Slipi, Taman Puring, and Taman Kalijodo (). They are equipped with street course elements, incorporating features commonly found in urban environments, such as ledges, ramps, kickers, handrails, flat surface banks, boxes, stairs, rails, and curbs.

However, like its origins, skateboarding is a free-form activity without standardized rules for specific movements. Skateboarders are often inventing new movements that have never been done before. The constant challenge and competition among skateboarders serve as a driving force for exploring and performing various styles and tricks. The pressure to execute a movement that aligns with the given situation and conditions adds to the thrill and excitement (Seifert and Hedderson Citation2010). Therefore, rather than solely relying on skateparks built by the government, street-skateboarders seek appropriate public spaces emerged in Jakarta. They require additional locations that allow them to explore and utilize the urban environment for their skateboarding experiences. As a result, the city often cracked down on street-skateboarding, confiscating boards and charging skateboarders with trespassing.

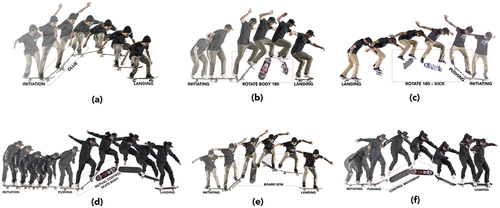

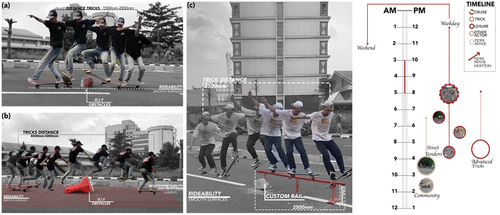

Almost all improved sidewalks are flat ground, which ideally serves street-skateboarders to perform various movements like jumping, sliding, or unpredictable manoeuvres. illustrates some tricks that showcase the visible and invisible boundaries recognized and followed by skateboarders, including (a) Ollie: the rider and board jump into the air without the use of hands, utilizing city fixtures as a jumping platform; (b) Frontside: the rider rotates to face the direction of movement for the first 90–180 degrees of the rotation; (c) Backside: at the peak of the backside 180 ollie, the skateboarder is not facing the direction of movement, making this trick slightly more challenging than the frontside variation; (d) Kickflip: the rider rotates the skateboard 360 degrees around the axis that runs from the head to the rear. When viewed from behind, the board rotates counter-clockwise when the rider is footed correctly; (e) Shuvit: the skateboarder spins the board 180 degrees or more without the tail making contact with the ground beneath their feet, and (f) Heelflip: similar to a kickflip, but the skateboard rotates in the opposite direction as users flip the board using their heel instead of their toes. Advanced skateboarders can explore countless other skateboard tricks by combining various board and body rotations and utilizing urban elements as obstacles.

Figure 3. Skateboarding tricks: (a) ollie; (b) frontside; (c) backside; (d) kickflip; (e) shuvit; (f) heelflip.Source: Author, 2022.

Street-skateboarders in Jakarta have adapted to the improved sidewalks by reimagining them as a place to “surf” and creating a super-architectural area where the individual, skateboard, and landscape unite in a parallel interaction. They execute their tricks on the sidewalk and carefully selecting areas with minimal street furniture to ensure that no significant damage is caused. Their “cool” attitude and ingenious acrobatics catch the eye of the passer-by, who actively cheers at their performances. The potential for arrest and imprisonment is not the foremost worry for street skateboarders, given that their actions are viewed as mischievous behaviour. They are greatly affected by the intimidation, assault, and frequent eviction from various locations by the Satpol PP officers, who perceive them as bothersome or disruptive to others.

There is always a degree of personal discretion involved in disciplining skateboarders. An intriguing occurrence unfolded when a situation involving skateboarders, Satpol PP, and the government transpired. During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021, a viral video surfaced on social media, showing an altercation between skateboarders and Satpol PP on the sidewalk of Sudirman Street in Jakarta. The Instagram video captured Satpol PP attempting to seize a skateboard from an individual. Subsequently, the Deputy Governor stated that skateboarding should not be done on sidewalks. In contrast, the best Indonesian skateboarder Satria Vijie claimed on Instagram that the Governor had allowed skateboarding on Jakarta’s sidewalks. This stark disparity in official opinions underscores the ambiguity surrounding the authorities’ stance. It also represents a captivating dynamic. As numerous cities globally resort to implementing skate stoppers as an essential part of low-tech security of urban surfaces to protect them from skateboarders (McDuie-Ra Citation2022a), the advent of street-skateboarding in Jakarta remains a relatively new disturbance. This emerging trend has resulted in an ambiguous status quo regarding the legality and acceptance of such activities in public spaces.

4. Overview of graffiti in Jakarta

Graffiti and street art are complicated and include numerous subtypes and participants. Multiple, sometimes complementary and at other times competing definitions and interpretations of what constitutes “graffiti” and “street art” exist (Soares Neves, Citation2016). Graffiti is considered an alternative expression for youths due to the limited accessibility of art to certain classes within a large city (Vanderveen and van Eijk Citation2016). Graffiti allows art to be publicly enjoyed and bridges the gap between exclusivity and public accessibility (Miles Citation1997).

The debate on whether graffiti is vandalism or art has been extensively discussed by various scholars (Mcauliffe Citation2012; Mubi Brighenti Citation2010; Vanderveen and van Eijk Citation2016). As interest in graffiti rises, perspectives on it have shifted. Writers prefer abandoned or neglected locations, looking for physically challenging places to leave their signature and developing trajectory maps of their city as they explore (Anselmo Citation2016; Colombini Citation2018). Observing the types and styles of graffiti makes it possible to determine whether an area is strictly controlled and whether the surface is compatible with the writers’ needs. Graffiti has often been associated with unsafe and deteriorating areas, leading to negative perceptions of the practice as vandalism. As a result, efforts have been made in many cities to prevent its spread, including using force and violence. However, as Kelling and Coles argue (1997), such approaches are unlikely to solve the problem and may only exacerbate it. The emerging academic research on graffiti tends to view it as a form of self-expression within youth subculture (Mcauliffe Citation2012; Merrill Citation2015). Consequently, graffiti and street art are closely linked to the desire of young people to experience excitement through engaging in “covert thrills” (Katz Citation1988).

Graffiti also encompasses the broader challenge of how cities in Indonesia address the problem of visual pollution caused by illegal banners and advertisements. This visual pollution ranges from the party and official propaganda to advertisements that cover public spaces, including the unsightly practice of a toilet suction advertisement taped to a tree. Jakarta, being an attractive and strategically located city, gives rise to several challenges related to the presence of illegally installed and structurally unstable billboards and non-compliance with tax payments. To address these concerns, the local government has implemented regulations outlining the control and enforcement measures for billboards that do not adhere to the stipulated guidelines. Like skateboarding, the responsibility for this control lies with the Satpol PP. However, the effectiveness of Satpol PP in providing a deterrent effect remains questionable. The sight of Satpol PP dismantling and apprehending illegal banners has become a daily occurrence in Jakarta, indicating that the current approach may not effectively deter violators ().

Graffiti writers by the youths in Jakarta come from various backgrounds, including middle-class youths and art school graduates. Marginalized groups do not solely dominate the movement but are a diverse and inclusive community of individuals who share a passion for the art form. Graffiti in many Indonesian cities is also used for social commentary and political expression. It provides a platform for individuals to voice their opinions on social and political issues, such as corruption, inequality, and environmental degradation. How graffiti artists used their work to challenge the status quo and call for change released on a documentary video produced by Painting Explorer entitled “Coretan Seni Dibalik Vandalisme” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WMmUaEZnxno). The video also provides a balanced and objective analysis of graffiti, incorporating perspectives from both practitioners and academics.

Furthermore, the rise of graffiti in Jakarta has been led to the emergence of street art and muralism (). These art forms are often commissioned by local businesses and organizations to beautify public spaces and convey a positive image of the city. This shift towards more accepted public art forms has helped legitimize graffiti and elevate it to a more respected art form in Jakarta. Throughout history, there have been several notable graffiti artists whose pursuits have brought them fame in graffiti (Merrill Citation2015; Snyder Citation2017). In Jakarta, a few individuals have been credited with bringing and popularizing the graffiti scene in the city. One of these artists is Hamzah, the first to use ink in his drawings, leading to the rise of the tag #CNGR within the scene. He inspired both “toy” and “king” graffiti artists. Hamzah’s artworks have persevered to this day, and the graffiti community has helped preserve them, forbidding other crews from overwriting #CNGR’s works.

In Jakarta, a range of graffiti tags can be observed in prominent graffiti locations, ranging from simple tags to intricate pieces. The motivations behind the graffiti vary significantly from location to location. Graffiti has evolved in a short time as an artistic medium, but artists still express themselves in various styles (see ), including (a) Throw-up: a more advanced version of a tag. It typically features two or more colours and typography in bubble form. A throw-up can be done quickly and frequently, like a tag; (b) Tag: the most basic style of graffiti, consisting of a single colour and the writer’s name or identification. Writing a tag over another writer’s tag or any other style is considered disrespectful; (c) Blockbuster (Roll-Up): a large throw-up with blocky lettering. Blockbusters quickly cover a wide area of ground, and rollers may be used to paint them, making the process quick and easy; (d) Piece: A freehand painting is known as a piece – short for a masterpiece. They take longer to paint as they include at least three colours. Since painting on walls in a visible location where graffiti is forbidden is a significant risk, a piece in an open area will earn the writer recognition from other writers; (e) Heaven-Spot: a tag or artwork in an exceedingly difficult-to-reach location. It is commonly seen on giant billboards on the upper floors of buildings. A writer who succeeds in putting one up earns the approval of their peers.

Figure 6. Graffiti styles: (a) throw-ups; (b) tag; (c) blockbuster; (d) piece; (e) heaven-spot.Source: the author, 2022.

4.1. Methodology

The appropriation of public spaces allows youths to actively participate in producing urban space by giving actions to the existing elements. This study aims to identify the most prominent spatial factors in the appropriation process on the urban space elements. Four case studies focused on Jakarta’s skateboarding and graffiti scenes. The case studies involved detailed observations of two streets for skateboarding: Sudirman Street and Raya Damai Street, and two locations for graffiti: Suryopranoto Street and the underpass of BNI City Park on Sudirman Street. Case studies have been intentionally selected from streets that the government has meticulously revitalized rather than opting for common areas characterized by disordered street conditions. In this case, local dynamics, cultural influences, and contextual factors were considered, allowing for a deeper exploration of the issue of appropriation within the urban context of Jakarta.

For the interviews, two skateboarders were chosen as informants: Ma (male, 25 years old, barista) and Fe (male, 18 years old, student). For graffiti, two writers named Fabs (male, 14 years old, student) and Fat. Caps (male, 26 years old, freelance designer) were chosen as informants. The participants were purposefully selected to ensure that individuals with experiences are included, providing a comprehensive understanding of the research topic within the city context. As the study aims to explore the experiences, perspectives, and meanings, the selected respondents will emphasize the richness and depth through the detailed narratives, diverse perspectives, and nuanced insights captured during observation and interviews. The choice to select male informants was due to the observation that street skateboarders and graffiti writers in Jakarta are predominantly male. While there is a significant presence of women participating in the skateboarding community, it is notable that they often prefer to use skateparks rather than streets for their skateboarding activities.

The accuracy and credibility of this research are significantly bolstered given that the first author, an active female skateboarder, was able to gather data through naturalistic observation. The following steps were taken for data collection in situ for both skateboarding and graffiti: site visits involved participating in skateboarding and graffiti activities, documenting the experience, and conducting interviews. Site visits in September 2022 provided direct observation of the location to assess its condition accurately. During observation, details such as access, atmosphere, and rideability of the surface were noted to identify the potential of urban space in accommodating youth activities. Documentation included taking photographs and videos of the location, plus the surrounding environment, infrastructure and features relevant to the practice. Interviews were conducted with skateboarders and graffiti artists to gain insights into their perspectives on the location, its suitability for their activities, and their experiences with authorities and other public members. Through this process, a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between urban space and youth appropriation practices can be achieved.

Observational data were collected at each site through on-site documentation, including visual mapping of the chosen locations to identify the existing urban elements and their potential to accommodate the related activities. A detailed investigation was conducted on the appropriate spots, identifying the potential affordances created by the urban element materials. The interviews covered five aspects related to the act of skateboarding and how skateboarders inhabit urban spaces: (1) motivation; (2) chosen spots for skateboarding; (3) the relationship between skateboarding and urban space; (4) the relationship among skateboarders and other inhabitants of urban space; and (5) skateboard mechanisms. For graffiti, the interviews focused on six aspects related to the act of graffiti and how graffiti writers inhabit urban spaces: (1) interpretations; (2) backgrounds and motivations; (3) chosen spots for graffiti; (4) the relationship between graffiti and urban space; (5) the relationship among graffiti writers and other inhabitants of urban space; and (6) graffiti mechanisms.

The study aims to identify the essential factors for youths’ preferred space by analyzing the urban skate-able spots and the locations where graffiti tends to recur. The analysis is based on three primary spatial appropriation tactics of youth-driven public space appropriation in Hanoi, Vietnam, examined by Geertman (Citation2016) that involved: (1) adapting to the spatial conditions of the city, (2) utilizing the material surfaces; and (3) generate interstitial spaces and found spaces for their activities. The case studies will be classified and analyzed to determine how each site caters to the acts of skateboarding and graffiti and how youth deploy their tactics while occupying a suitable spot. Additionally, the study includes an interview with the Head of the Transportation Department (Kadishub) to represent the local authority of the Metropolitan Government of Jakarta and gain their perspective on the appropriation of both youths plays.

5. Discussion

5.1. Skateboarding

The two case studies of Sudirman Street and Raya Damai Street discussed how street-skateboarder has emerged as a celebratory response to the recently revamped sidewalks by the government, given that, until recently, Jakarta’s streets were not conducive to such activities. The introduction of new, smooth, and flat sidewalks captured the attention of skateboarders, offering an ideal platform for executing flip tricks. Not only does this form of street skateboarding provide an engaging recreational outlet for the skateboarders, but it also serves as an entertaining spectacle for onlookers and passersby.

5.1.1. Skateboarding at Sudirman Street

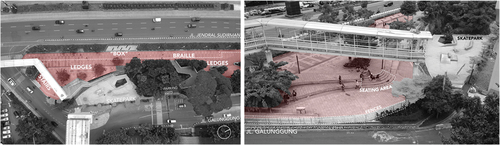

At Sudirman Street, the local authority provides a skatepark at Skatepark Dukuh Atas, which offers various obstacles for skateboarding, thereby minimizing the damage to public facilities. However, skateboarders are still seen occupying pedestrian paths of Sudirman Street, considering them a “skate-able” spot rather than using the existing skatepark (). The informants agreed that the pedestrian path of Sudirman Street is the preferred spot due to the accessibility and the availability of various obstacles for skateboarding. Fe focuses more on the surface materials and obstacles within a space, while Ma considers the comfort of space when choosing a skate spot. The path highlights skateboarders’ flexibility and free-flow nature, who prefer to explore various locations rather than confining themselves to a specific area.

The local authority acknowledges that the skate park provided at Sudirman Street has limitations in size and elevation, which may only partially satisfy skateboarders’ needs. However, they express concern over skateboarders occupying pedestrian paths, as it disrupts the intended function of these spaces. Therefore, they view this as a form of disturbance and disorder. Additionally, the local authority emphasizes that urban furniture, such as road barriers and railings, have designated functions and violating these purposes through skateboarding is considered vandalism.

Figure 7. The path at Sudirman Street (left) and Skatepark at Dukuh Atas (right).Source: Author, 2022.

Skateboarders enthusiastically embrace the recently developed, sleek pedestrian paths and urban installations such as road barriers and railings, utilizing them as a canvas to showcase their impressive flip tricks. Importantly, they do so without causing any harm or modifying the original surfaces, gracefully executing grinding, sliding, and bonking maneuvers ().

Figure 8. The interplay of skateboarders and urban elements in Jl. Jendral Sudirman: (a) ledges; (b) box; (c) stairs.Source: Author, 2022.

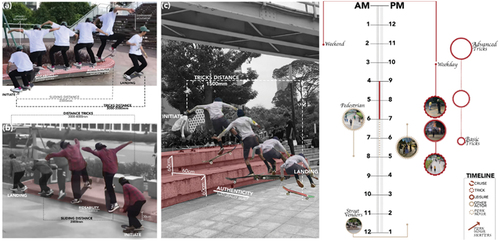

Ma, the informant for the skateboarders, revealed that he skates almost every day and enjoys skating on weekends from 3:00 PM until night-time. Skateboarders occupy the same areas as pedestrians and street vendors during peak hours. They tend to skate on the edges of the pedestrian paths and maintain a reasonable distance from others. They “surf” in a zig-zag flow to avoid collisions and stop occasionally. Moreover, they tend to perform their tricks when fewer people are around to ensure safety and avoid disrupting other users.

5.1.2. Skateboarding at Raya Damai Street

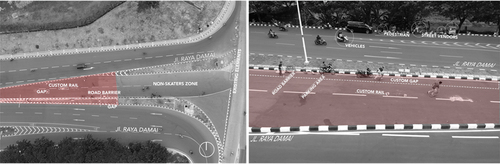

Raya Damai Street is situated in a cul-de-sac type of street, which provides a smooth surface and road barriers surrounding the area, making it feel secure and aligning with the characteristics of a skate-able spot. However, the spot is small, allowing skateboarders to refrain from surfing longer and performing advanced tricks (). In addition, Fe mentioned several hindrances that skateboarders are likely to encounter outside of skate parks, such as the need for more surveillance and obstacles that hinder skating movements. Nevertheless, skateboarders in this spot challenged themselves to use the existing features to create customized obstacles, reflecting a DIY approach. Contrary to the creation of DIY skateparks as explored by Hollett and Vivoni (Citation2021) and Kyrönviita and Wallin (Citation2022), they addressed the issue of space limitation. They introduced a custom rail, utilized existing elements like rocks and road barriers, and modified materials to enhance rideability, thereby facilitating their activities (). Skateboarders also cared for the road surface, repairing cracks to ease their movement and enhance their experience.

Fe and his crew, WJT_SK8, share the skateboarding Space at Damai Street with other users, such as street vendors, motorcycle communities, BMX riders, and pedestrians. These different user groups define their areas and boundaries through their unique marks, with skateboarding areas marked by the appearance of skateboarding obstacles. In contrast, motorcycle communities define their spot with wheel stamps. Skateboarders and motor gangs leave their marks as a symbol of reclaiming their space. While there are no formal time limits or agreements between communities and inhabitants, they share the space and adjust to their surroundings. Despite the different user groups sharing the space, Fe and his crew prioritize safety by avoiding peak hours and maintaining a reasonable distance from other users, respecting the physical and spatial needs of other actors in the space.

The urban skate-able spot reflected upon two dimensions:

spatial condition: Regarding accessibility, both skate spots are relatively easy to reach, but Sudirman Street offers more public transportation options than Damai Street. Despite their simplicity, the designs of both streets accommodate skateboarders’ movements effectively, with the path’s dimensions ensuring a steady flow of skateboarders. The attractiveness of a site depends on the variations of obstacles and unique urban elements that offer interpretability of space, hence providing an optimum experience for skateboarders. Both informants prefer street skateboarding as it provides a sense of unpredictability and urban life. They also prefer skating in a comfortable space with a pleasant atmosphere and setting. Skateboarders spend their recreational and leisure time adjacent to their skating path, so the appearance of street vendors and other amenities fulfil their needs.

materiality: Choosing suitable materials for skateboarding is crucial as they must withstand the friction and rough contact between the board and the obstacles. Ma and Fe prefer to “surf” on smooth surfaces and “jump” whenever they encounter a textured surface. In addition, they preferred skating in spaces that allowed them to explore the city with their board, as this is the original purpose of skateboarding. The calm atmosphere in both spots creates a relaxed ambience that helps skateboarders concentrate while doing their tricks. According to both informants, each location can accommodate skateboarding and other activities with the help of the existing elements. However, the sidewalk of Sudirman Street offers more of the city’s features and meets more of the criteria for an urban skate-able spot than Damai Street, which has fewer visible urban elements.

5.2. Graffiti

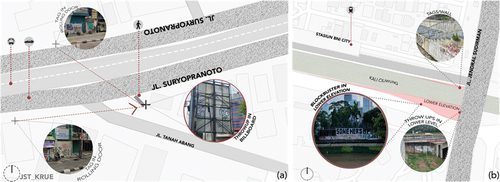

Graffiti has its progression movements, starting with simple tags or throw-ups and moving on to larger pieces in targeted spots, followed by more petite tags on the way home. By observing the walls, one can identify the trajectories map of local writers in a particular area (). Therefore, the spatial observation of graffiti focuses on the writers’ location and movement.

Figure 10. The skateboarders in Jl. Raya Damai: (a) gap; (b) road barriers; (c) custom rail.Source: Author, 2022.

Figure 11. Trajectories-based map: (a) Suryopranoto Street; (b) Sudirman Street.Source: Author, 2022.

Various factors, including the level of surveillance and the presence of urban elements, can influence the occurrence of graffiti. Areas with lower levels of surveillance and fewer users may be more attractive to writers, as they can take more time to create their pieces. Sometimes, the writer’s appropriate spaces on buildings that have been neglected or abandoned, such as setbacks or facades facing the road. The setbacks are often used as a writing surface for the lower levels, while fences are utilized to facilitate upward movement and rideability. These neglected buildings can be appropriated by writers for long periods, as there is minimal supervision. Specific architectural elements of buildings, such as overhangs, frameworks, and facade walls, can inspire graffiti writers, prompting them to offer fresh interpretations of the space. These elements are particularly intriguing as they often facilitate the movement of graffiti artists, enabling them to access and explore the upper levels of the building.

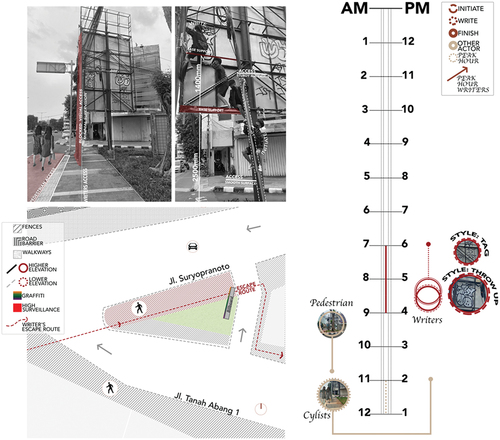

5.2.1. Graffiti at Suryopranoto Street

Suryopranoto Street is a major junction between two main roads, making it a prominent location. During observation, Fabs was doing throw-ups on an existing billboard for around 10–15 minutes. In addition, the spot where he worked was situated between two walkways facing opposite directions, making it an exposed area for other street inhabitants. Through a two-day observation, the frequency of pedestrians was identified. The findings revealed that pedestrians rarely appeared in the area, which may be due to the position of the electrical pole limiting their movement. However, a bar on the billboard side minimizes the chance of Fabs getting caught by blocking direct observations from pedestrians. This case study highlights the minimal supervision in deserted areas where affordances offer coverage. As shown in , Fabs writes during the daytime, specifically at 4:00 PM.

5.2.2. Graffiti at Sudirman Street

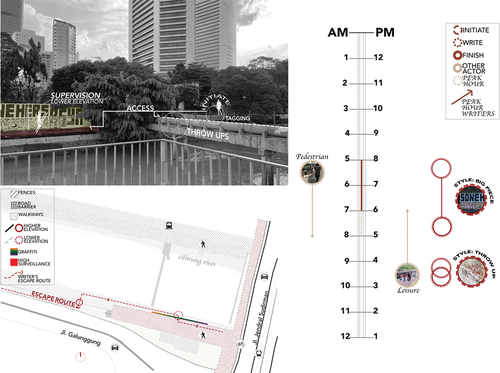

Writers use customized ladders from existing materials such as wood or metal to access the higher walls. These ladders offer a solution to the problem of the height of the walls and enable writers to access otherwise unreachable areas. Additionally, the smaller walls that lead to the main writing spot offer opportunities for writers to practice and experiment with their techniques before moving on to the more giant walls. The location of the writing spot also allows for anonymity and minimal surveillance, which enables writers to work without fear of being caught. However, the long route to access the spot and the physically challenging nature of the climb may limit the frequency of visits by writers. Despite this, the affordances provided by the urban elements at this location have enabled writers to appropriate the space and create their works ().

Fat. Caps and their crew were challenged to write in a strictly supervised area, although their position remained slightly invisible to the Satpol PP and inhabitants. Despite this advantage,

Fat. Caps and the crew were still limited by the materiality of the elements and had to bring their ladders for writing purposes. They needed help to write complex graffiti styles such as blockbusters and pieces in two hours at maximum. The strict surveillance also hindered their escape plan, so the rest of the crew members had to stay on top to watch out for potential Satpol PP who might catch them in the act. In their escape route, Fat. Caps and the crew chose a smaller path and climbed through walls, as it is common for Satpol PP to trap writers on open roads. Writers on each site carefully plan these “game plans” before conducting their actions ().

The government openly acknowledges that they lack comprehensive data on the extent of graffiti vandalism cases. While recognizing the significance of graffiti as an indicator of disorderly behaviour, they express concern over its prevalence. When queried about their views regarding the government’s plea to curb graffiti due to its disruptive impact on order, the writers adamantly expressed that the government should prioritize addressing the visual pollution caused by candidates participating in legislative elections. They emphasized that the appearance of these candidates is particularly alarming, citing their perceived narcissistic tendencies as a cause for concern.

Both case studies align with “Spot theory” (Ferrell and Weide Citation2010) that graffiti writers reinterpret the cityscape, constantly reimagining the urban space as they traverse through the city. Their mental maps remain perpetually in flux, a fluid interplay between urban networks and spaces. The following conditions were observed: (1) Accessibility: Fabs and Fat. Caps tend to do a tag before creating a more significant piece. As a result, accessible spots such as street signs, rolling doors, and walls tend to have more graffiti than other locations; (2) Surface Rideability: The compatibility between the writer’s body and the surface materials is crucial for their movements. The robust materials illustrated in the case studies help writers’ movements to reach a particular spot; (3) Minimal supervision: Fabs, Fat. Caps and their crews prefer to write in areas with minimal supervision when they write complex pieces or use intricate movements to reach a particular spot. In this way, they can take their time and avoid getting caught by Satpol PP.

The study of skateboarding and graffiti writer appropriate public space revealed some findings:

While there are no formal guidelines within the skateboarding and graffiti communities, they have consistently aimed to avoid confrontations. Several cases describe instances where the youth were apprehended by the police and their tools – cans for graffiti and skateboards for skateboarding – were seized. To retrieve them, they had to follow certain protocols that involved parental participation. Regarding their interactions with other city dwellers, both skaters and graffiti writers have fostered trustful relationships with their fellow occupants. A recent report in Instagram highlighted a few instances of skateboarders colliding with pedestrians, which drew significant public criticism. To avert such conflicts, skateboarders endeavour to carry out their activities in a cautious and considerate manner.

In most case studies, skateboarders and writers have received positive responses from the surrounding community. For example, Mrs A, a garage owner with graffiti-covered walls, expressed that youths should be creative rather than committing crimes. Other urban users who frequently pass Sudirman Street which appropriated by street skateboarders, perceive their activities as “normal” and do not find them bothersome. Skateboarding and graffiti are now recognized as integral elements of urban culture, with the community no longer regard them as disturbances.

Both skateboarders and writers have developed a strong attachment to their preferred locations. They interact with the elements and other occupants of the space, acquiring a deep understanding of its details, materiality, and everyday life. Skateboarders actively assist other urban users in need, whereas Fabs and Fat. Caps have gained more spatial recognition through organized street art and social media events.

The skateboarders and writers constantly adapt and challenge themselves to utilize the city’s materials to enhance their activities. Their actions reflect urban life’s unpredictable and dynamic nature as they seek new experiences and continuously develop their skills in styles and tricks. While indifferent to negative comments from others, they comply when confronted by authority figures.

The act of repeatedly scribbling their “tag” name on walls or other surfaces allows graffiti writers to develop their identities. These tags often feature phrases that inspire a sense of empowerment or resilience, with the identity expressed itself rather than their race or gender. On the other hand, street skateboarders represent themselves as they are, with many recording and publishing their performances on social media to gain recognition. Self-branding is their key focus, with many endorsed by exclusive brands. Street skateboarders showcase and represent their unique selves and skills through their performances.

6. Concluding Remarks

This paper strives to present skateboarding and graffiti regarding the ongoing transformation of Jakarta. The city is now striving to shed its reputation as a capital associated with traffic congestion and disorder and re-emerge as a modern orderly metropolis. The government has taken steps towards this goal, one of which includes renovating the sidewalks. Interestingly, amid such changes, skateboarding and graffiti have made their entry, repurposing these newly revamped public spaces in their own unique ways. Drawing parallels between New York City and Los Angeles, where the skateboarding community’s creative mobilization and convivial spirit serve as a model for grassroots resistance against public space neoliberalization (Chiu and Giamarino Citation2019), the phenomena of skateboarding and graffiti in Jakarta underscore the youth’s creative potential to transform prevailing urban spaces and structures into platforms for personal expression and recreational pursuits.

Skateboarders and graffiti writers engage with and creatively manipulate various urban elements, representing a form of spatial autonomy and resilience, showcasing their ability to overcome structural constraints and limitations. Contrary to other places where skateboarding has spread and often leads to the “shredding” or deterioration of public spaces, skateboarders in Jakarta have embraced a more preservationist approach. They strive to maintain the integrity of existing urban elements, adopting a DIY ethos that allows for creative engagement with the urban landscape while minimizing detrimental impact. Street-skateboarding utilizes a road separator, road barrier and custom rail for possible movement of jumping and sliding tricks. Therefore, they appropriate sidewalks with minimum marks and focused on performing flip tricks to avoid major obstructions. On the other hand, graffiti writers select spaces with minimal surveillance to avoid being caught, while also taking advantage of urban architectural features for their creative work. The trajectories map of graffiti showcases the spatial fluidity of this art form. By moving and creating new pieces around the city, they underscore a profound relationship between urban space and the creation of identity. Furthermore, graffiti writers undermine the city’s efforts to foster cleanliness, aesthetic beauty, and orderliness. However, while focusing on youth graffiti vandalism is necessary, the proliferation of unauthorized banners and advertisements needs attention. They not only detract from the visual appeal of cities but also raise concerns about the misuse and degradation of public spaces.

The study reveals that strategies provided within the city influence how the proprietors appropriate the site. Those residing in spots with fewer urban elements take the initiative to apply the DIY approach, which includes using urban and non-urban elements to fulfil their spatial needs. Hence, the “found space” concept emerges as the most suitable option to accommodate youth activities. They need to consider their capacity to analyze the public space they engage with, encompassing factors such as the space’s condition and material composition. Both appropriations, however, do not escape local authority scrutiny of Satpol PP, resulting in continuous tension between these subcultures and the local authorities’ attempts to maintain order and regulate public spaces. Skateboarding capitalizes on ambiguity, as Satpol PP officers frequently exercise discretion in maintaining order, allowing skateboarders to navigate within certain limits. On the other hand, graffiti seeks out locations with minimal supervision from Satpol PP, enabling writers to express themselves more freely.

Graffiti and skateboarding are interstitial practices that use urban media and disrupt socio-spatial stability. Both are forms of play that promote freedom of self-expression and movement. While skateboarding and graffiti have distinct spatial requirements, this paper found their similarities and why they often occur in the same areas. Both activities are presented in various forms of urban space once deterred by external factors, such as non-participating individuals, regulations, and the dynamic nature of the city. The character of their activities requires them to utilize the surrounding elements; thus, youth reclaim their spot in loose urban spaces (Stevens Citation2007), either found or interstitial. The exploration of skateboarding and graffiti in Jakarta indicates the vibrant relationship and dynamic interaction between youth subcultures, play spaces, and urban governance. Young people negotiate, challenge, and redefine the boundaries of acceptable behavior within public spaces that reflect a form of playful resistance against the conventional order and control of urban spaces. They are bringing to the fore the importance of accommodating diverse user needs in urban planning and design.

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by a grant from Universitas Indonesia under the program of PUTI Pasca Sarjana 2022-2023 with the contract number: NKB-312/UN2.RST/HKP.05.00/2022.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nabila Wardhana

Nabila Wardhana graduated from the Department of Architecture Universitas Indonesia in 2022. She was an assistant researcher in the Urban Research Cluster, focusing on urban design.

Evawani Ellisa

Evawani Ellisa pursued her doctoral degree at the Department of Environmental Engineering Osaka University in 1999, focused on urban transformation and livability of the inner-city area in big Indonesian cities. She is Professor at the Department of Architecture Universitas Indonesia, teaching Architectural Design Studio and Urban Design. As the head of the Urban Research Cluster, her research had been published in some of the international journals and proceedings https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2388-3884

References

- Akbar, J. 2010. Jatuh Bangun Sejarah Skateboard. Historia Online. Retrieved from https://historia.id/olahraga/articles/jatuh-bangun-sejarah-skateboard-6aNJD.

- Anselmo, A. 2016. “Artists or Vandals? Why Graffiti Art Receives Less Protection Than Other Forms of Art and How Federal Law Should Be Changed to Protect Graffiti Artists.” Fordham Art Law Society {FALS} , April 7. https://fordhamartlawsociety.com/2016/04/07/artists-or-vandals-why-graffiti-art-receives-less-protection-than-other-forms-of-art-and-how-federal-law-should-be-changed-to-protect-graffiti-artists/.

- Borden, I. 2019. Skateboarding and the City a Complete History. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474208420.

- Branch, J. (July 26, 2021). For Yuto Horigome, a Gold Medal Could Change Everything. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/24/sports/olympics/yuto-horigome-japan-skateboard.html.

- Chiu, C., and C. Giamarino. 2019. “Creativity, Conviviality, and Civil Society in Neoliberalizing Public Space: Changing Politics and Discourses in Skateboarder Activism from New York City to Los Angeles.” Journal of Sport & Social Issues 43 (6): 462–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723519842219.

- Colombini, A. 2018. The Duality of Graffiti is It Vandalism or Art? Four Study Days in Contemporary Conservation CeRoart Conservation, Restoration D’Objects D’Art https://journals.openedition.org/ceroart/5745.

- Donnelly, M. 2006. “Studying Extreme Sports: Beyond the Core Participants.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 30 (2): 219–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723506287187.

- Ferrell, J., and R. D. Weide. 2010. “Spot Theory.” City 14 (1–2): 48–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810903525157.

- Geertman, S., D. Labbé, J.-A. Boudreau, and O. Jacques. 2016. “Youth-Driven Tactics of Public Space Appropriation in Hanoi: The Case of Skateboarding and Parkour.” Pacific Affairs 89 (3): 591–611. https://doi.org/10.5509/2016893591.

- George, L., and C. M. C. Kelling. 1997. Fixing Broken Windows: Restoring Order and Reducing Crime in Our Communities. Simon and Schuster.

- Gibson, J. 1986. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. London: Psychology Press.

- Glenney, B., and S. Mull. 2018. “Skateboarding and the Ecology of Urban Space.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 42 (6): 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723518800525.

- Goodfellow, E. 2016, August 26. How Skateboarding Culture Impacts How We See the World. Hero Magazine. Retrieved from https://hero-magazine.com/article/71690/how-skateboarding-culture-impacts-how-we-see-the-world.

- Hollett, T., and F. Vivoni. 2021. “DIY Skateparks as Temporary Disruptions to Neoliberal Cities: Informal Learning Through Micropolitical Making.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 42 (6): 881–897. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2020.1742095.

- Karsten, L., and E. Pel. 2000. “Skateboarders Exploring Urban Public Space: Ollies, Obstacles, and Conflicts.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 15 (4): 327–340. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010166007804.

- Katz, J. 1988. Seductions of Crime: Moral and Sensual Attractions in Doing Evil. New York: Basic Book.

- Kilberth, V., J. Schwier, V. Kilberth, and J. Schwier. 2019. Skateboarding Between Subculture and the Olympics: A Youth Culture Under Pressure from Commercialization and Sportification. Verlag Bielefeld. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839447659.

- Kyrönviita, M., and A. Wallin. 2022. “Building a DIY Skatepark and Doing Politics Hands-On.” City 26 (4): 646–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2022.2079879.

- Lefebvre, H. 1974. The Production of Space. New Jersey: Blackwell Publishing.

- Marcus, B., and L. Daniella Griggi. 2011. The Skateboard: The Good, the Rad, and the Gnarly: An Illustrated History. First ed. New York: MVP Books.

- Mcauliffe, C. 2012. “Graffiti or Street Art? Negotiating the Moral Geographies of the Creative City.” Journal of Urban Affairs 34 (2): 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2012.00610.x.

- McDuie-Ra, D. 2021. Skateboarding and Urban Landscapes in Asia: Endless Spots. Amsterdam University Press.

- McDuie-Ra, D. 2022a. “The Draw of Dysfunction: India’s Urban Infrastructure in Skateboard Video.” Geographical Research 60 (3): 383–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12531.

- Mcduie-Ra, D. 2022b. “Skateboarding and the Mis-Use Value of Infrastructure.” An International Journal for Critical Geographers 21 (1): 49–64.

- McDuie-Ra, D. 2023. “Chasing the Concrete Dragon: China’s Urban Landscapes in Skate Video.” Space and Culture 26 (1): 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331220916390.

- McDuie-Ra, D., and J. Campbell. 2022. “Surface Tensions: Skate-Stoppers and the Surveillance Politics of Small Spaces.” Surveillance & Society 20 (3): 231–247. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v20i3.15430.

- Merrill, S. 2015. “Keeping It Real? Subcultural Graffiti, Street Art, Heritage, and Authenticity.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 21 (4): 369–389. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2014.934902.

- Miles, M. 1997. Art, Space and the City: Public Art and Urban Futures. New York: Routledge.

- Mubi Brighenti, A. 2010. “At the Wall: Graffiti Writers, Urban Territoriality, and the Public Domain.” Space and Culture 13 (3): 315–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331210365283.

- Mulyadi, M. A., A. Verani Rouly Sihombing, H. Hendrawan, A. Vitriana, and A. Nugroho. 2022. “Walkability and Importance Assessment of Pedestrian Facilities on Central Business District in Capital City of Indonesia.” Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 16:100695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2022.100695.

- Németh, J. 2006. “Conflict, Exclusion, Relocation: Skateboarding and Public Space.” Journal of Urban Design 11 (3): 297–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574800600888343.

- Newsware, S. 2020, January. INTERVIEWS Ocean Howell Explains How Skateboarding is Used for Gentrification. Retrieved from https://skatenewswire.com/solo-ocean-howell-interview/.

- Nurhayadi, V. 2006. Speed and Light: Indonesian Skateboarding. Jakarta, Indonesia: Gagas Media.

- O’Connor, P. 2018. “Hong Kong Skateboarding and Network Capital.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 42 (6): 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723518797040.

- Ong, A. 2016. “The Path is Place: Skateboarding, Graffiti and Performances of Place.” Research in Drama Education 21 (2): 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569783.2016.1155407.

- Parenting, O. 2019. Tidak Disangka, Ternyata Ini 4 Manfaat Bermain Skateboard untuk Anak. Orami Parenting. Retrieved from https://www.orami.co.id/magazine/4-manfaat-bermain-skateboard-untuk-anak.

- Pugh, E. 2015. “Graffiti and the Critical Power of Urban Space.” In Space and Culture 18 (4): 421–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331215616094. SAGE Publications Inc.

- Raposo, O. R. 2023. “Street Art Commodification and (An)aesthetic Policies on the Outskirts of Lisbon.” In Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 52 (2): 163–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/08912416221079863. SAGE Publications Inc.

- Ross, J. I., edited by 2016. Routledge Handbook of Graffiti and Street Art. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315761664.

- Seifert, T., and C. Hedderson. 2010. “Intrinsic Motivation and Flow in Skateboarding: An Ethnographic Study.” Journal of Happiness Studies 11 (3): 277–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-009-9140-y.

- Shwartz, M. E., and N. Mualam. 2022. “Challenges in the Creation of Murals: A Theoretical Framework.” Journal of Urban Affairs 44 (4–5): 683–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2021.1874247.

- Snyder, G. J. 2017. Long Live the Tag: Representing the Foundations of Graffiti in Graffiti and Street Art: Reading, Writing and Representing the City, Editors Avramidis, K, and Tsilimpoinidi, M. New York: Routledge.

- Soares Neves, P. 2016. Street Art & Urban Creativity Scientific Journal, edited by, Neves Pedro Soares. Lisboa: Instituto Universitário de Lisboa.

- Stevens, Q. 2007. The Ludic City: Exploring the Potential of Public Spaces. London: Routledge.

- Suhartanto, T., D. Perwira, D. Rusmiati, and D. Sulistiani. 2021. “Differences in Authority Between Satpol PP and Polri in Creating General Order.” International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change 15 (4): 1098–1114. Www.Ijicc.Net.

- United Nations Dept. of Economic and Social Affairs. 2005. World Youth Report: Young People Today and in 2015.

- Vanderveen, G., and G. van Eijk. 2016. “Criminal but Beautiful: A Study on Graffiti and the Role of Value Judgments and Context in Perceiving Disorder.” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 22 (1): 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-015-9288-4.

- Willing, I., and A. Pappalardo. 2023. Skateboarding, Power, and Change. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1234-6.

- Woodman, D., and A. Bennett, edited by 2015. Youth Cultures, Transitions, and Generations. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137377234.

- Wooley, H., and R. Johns. 2001. “Skateboarding: The City as a Playground.” Journal of Urban Design 6 (2): 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574800120057845.