ABSTRACT

Cultural heritage is a reflection of a community’s adopted ways of life. It comprises customs, behaviors, settings, physical objects, artistic expression, and ideals. As an impact of the Earthquake in 2015, the heritage building suffered catastrophic damage. This research examined the Thimi community’s approach to urban heritage construction through conservation, reconstruction, renovation, and restoration, and shares problems, success stories, and lessons learned in the cases of Phalcha (Rest House) and Dyo (Temple). The Thimi Municipality provided all required technical and financial support for these renovation and reconstruction activities. Conducting a depth literature review and understanding the process of both qualitative and quantitative methods of rebuilding, renovating, and restoring the urban cultural heritage structure, this research uses a case study approach. Locals, consultants, and technical employees involved in the rehabilitation and planning work provided most of the materials for all case studies. This study finds that the residents of Thimi feel pride in having their heritage structures restored by local community participation. Despite the local community efforts, there are a few shortcomings with the financial, technical, social, and administrative constructions and understanding of customary practices. The Madhyapur Thimi Municipality has developed measures to support communities willing to lead urban heritage conservation.

1. Introduction

Ever since Brian Houghton revealed Nepal to the west in the middle of the 1800s, Nepal has earned popularity in art, architecture, and culture. Historical structures in the Kathmandu Valley have undergone extensive architectural analysis (Singh Citation2013). As a popular tourist destination, the Kathmandu Valley is an excellent example of a “tribal community” with immigrant populations. The Newars are the majority in terms of population and rich cultural development. They typically outperformed other ethnic groups in the valley with their settlement styles in established towns and villages, architecture and artwork, and commercial knowledge (Korn Citation1979). People’s lives were enhanced by places of cultural significance because they felt profoundly and powerfully connected to the locals and the environment. Every location has a unique past and identity. The Kathmandu Valley has a unique history as well.

Research gap: Rupesh Shrestha (Shrestha Citation2021) researched urban heritage conservations in Patan City, a neighboring city to the Kathmandu district. In addition to the study on Patan City, Shrestha’s research also included various cases within the Kathmandu valley and proposed ideas for expanding the Upabhokta Samiti (a users’ group) model. Patan and the center of Kathmandu have undergone post-earthquake recovery, Renovation, Restoration, and preservation. Shrestha’s study is more focused on the core city of the Patan and Kathmandu districts, whereas this study brings more detailed information and light on the approach required for the conservation and Renovation of the cultural heritages in the peripheral City of Thimi. Comparing the information gathered through this study and Shrestha’s study on other cities can provide better perspectives on how the cultural heritage conservation and renovation issues resulting from a devastating earthquake can tackle more practically.

The helping communities in Thimi are actively renovating the community structures such as Wammune Ganesh Dyo (Temple), Kutu Falcha (Rest House), Lipha Ganesh Dyo (Temple), Lipcha Shattle (Rest House), Monobinayak Falcha (Rest House), and Balkumari Dyo(Temple). The Communities are expediting the rebuilding efforts by partnering with local Governments and agencies for heritage protection. Government and the general public acknowledge community-based rehabilitation as a vital strategy. The Madhyapur Thimi Municipality (the City) also supports restoring monuments within the Thimi heritage area.

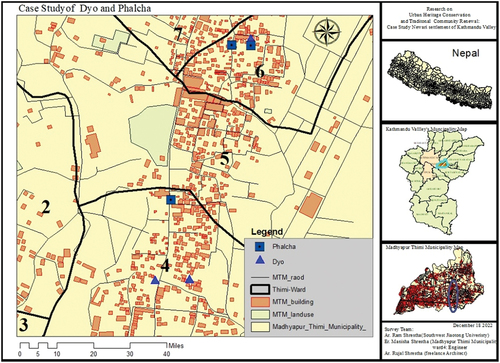

Numerous communities through organizations that deeply connect to legacy and call for more responsibility in historical repairs, such as in Madhyapur Thimi Municipality. The location map of the City provides in . This study approach is crucial, as are the difficulties encountered and the lessons acquired. By evaluating the difficulties of implementation and being aware of successful examples in local communities through projects for reconstruction, restoration, and refurbishment, the right policies can be put in place to upscale historical reconstructions and improve their quality and pace. Understanding urban cultural built heritage or rebuilding, rehabilitation, and preservation is the goal of the research. This research mostly:

Examine Post-Earthquake Community Recovery for Urban Heritage Conservation; Case Study of Thimi-Issues and Lessons Learned

To Study the Procedures for exchanging expertise used during safeguarding urban cultural heritage.

According to the Department of Archaeology’s early report, this Earthquake may have impacted up to 745 monuments in 20 regions. There were 517 slightly damaged, 95 partially destroyed, and 193 destroyed monuments. The assessment affected only 444 monuments in the Kathmandu Valley, 83 of which fell to the ground. (DOA) (Davis et al. Citation2020; Government of Nepal Citation2015). The case study area Thimi is located 85 km southeast of Barpak, the epicenter of the 2015 Earthquake in Nepal.

1.1. Literature review

Theory of urban heritage: In reaction to the defense systems of many fortified medieval European cities lost due to their growth, awareness of the importance of old urban centers first emerged in the late nineteenth century, when the conservation movement began. At this time, a city sees as a monument or a piece of art (Jokilehto Citation2006).

Cultural legacy includes habits, practices, tangible things, artistic expression, and values formed by communities and passed down from generation to generation (Ethos, The Charter, and Cultural Heritage Citation1999). Apaydin (Citation2020) African American culture is used as an example to illustrate how individuals express their previous histories in the present. The Absence of ancestry affects both individual and collective identity. Apaydin (Citation2020). Further asserts that heritage and identity are fundamentally linked. The development of communal memory, a sense of location, and a connection to history are all significantly influenced by heritage. The ancient artifacts of tangible (historic, monuments, buildings, landmarks, etc.) and intangible (atmosphere, the spirit of place, ambiances, and belief), represent cultural resources. These numerous components combine to form the “constructed” form of varied scales, offering priceless information from diverse historical eras. Every place differs from other areas because of its unique originality, characters, and identity (B. K. Shrestha Citation2001; UNESCO Citation2006). A location has cultural and experimental importance and is both the past and the present with a view toward the future (UNESCO Citation2006).

For this study, the research paradigm put forward by Kepe (Citation1999) McMilan and Chavis (McMillan and Chavis Citation1986), and others have identified four qualities that make up a community. The first is a feeling of group membership or belonging. The second is influence, or the feeling that one matters and affects the group. The third Shared emotional connection, or the unwavering and fourth unwavering conviction that members share a common past, present, and future circumstances, is a defining trait.

The Community can actively contribute to the resilience of the socio-urban system and the preservation of its cultural legacy, According to the Sendai Framework 2015; it serves as the repository for local cultures. This is further clarified in the Burra Charter of 1979, which mandates that opportunities for participation in the preservation, interpretation, and management of a place should be made available to individuals who have unique associations with the area and individuals who hold responsibility for the area’s social, spiritual, or other cultural aspects. Fabbricatti et al. (Citation2018). Cite the unique case of Irpinia. In this Italian town, several community-through activities have grown over a short period, enhancing the collaboration of regional players and their “knowledge of the place,” which links social and cultural capital as enablers for durable and long-lasting human settlements.

Orbaşli (Citation2017) argued for the value-based methodology & scientific techniques and pointed out the importance of extensive collaborations between academics, local Government, and higher-level government organizations. The Rekompak strategy, used in Indonesia, is an intriguing case study on communities harmed by disasters since the strategy proved helpful in restoring their customary structures receiving funds directly from the government budget as block grants. These structures were built by the community settlement plan (CSP). In order to help the Community and the Government build their organizational, administrative, financial, and technical capacity for managing and protecting their cultural heritage, the Rekompak supplied facilitators.

Murakami et al. (Citation2014) and Posio (Citation2019) describe the intriguing Japanese concept of Machizukuri, which is concerned with how residents participate in the management and development of their living spaces helps better at the Local Level. It also contributed to the rebuilding of a feeling of place and Community. Posio (Citation2019) describes the efforts Yamamoto Town made to create Machizukuri councils to include locals as active participants in community building and to foster communication between the town administration and the inhabitants in the wake of the 2011 catastrophe. Local governments or municipalities should play a significant part in reconstruction as they are more familiar and knowledgeable about local conditions than other actors.

Letelier and Irazábal (Citation2018) As shown by their case study in Talca, Chile, community-based efforts enable more equitable and sustainable regeneration of a location. They also emphasized that in Talca’s instance, this revelation occurred considerably later than usual after many urban poor inhabitants had fled gentrification and moved to outlying locations with few work opportunities, public transit options, and basic amenities. Few publications discuss a comparison of Nepal’s community-based heritage rebuilding, Restoration, and renovation strategy to worldwide best practices.

There are many issues with the Community’s heritage recovery initiative. Orbaşli (Citation2017) has said, with reason, that the increasing influence of well-meaning community members who are frequently amateurs and emotionally driven diminishes the value of conservation’s scientific and technical parts. In addition, Lewer et al (Jahan Citation2019), through their research in Dohani of Greater Lumbini, raise questions about how difficult it is to convince local communities to participate in cultural preservation when there are no immediate social, spiritual, or financial benefits. Community-through processes require patience and sustained effort to mature fully. An impasse was discovered in bottom-up community development strategies by Machizukuri scholars where Satosh (Jahan Citation2019) claims that Machizukuri should replace by a more comprehensive regional management system that includes administrative rules and tools for urban planning.

According to Chadani KC et al., the function of cultural assets in a post-disaster environment and its significance in upholding social and cultural values throughout earthquake-damaged communities’ rehabilitation. The Kathmandu Valley in Nepal serves as the location. Daily customs, festivals, and processions that were part of the valley’s intangible legacy helped people overcome the calamity’s trauma and reconnected communities. According to the study, cultural legacy is crucial in assisting individuals in readjusting to their new circumstances following big catastrophes like the 2015 Nepal earthquake. It makes a case for including cultural heritage in the recovery and development phases (KC Citation2019). If the Government does not step in to support allowing the Community to take the lead, the indigenous people who put effort into maintaining their social customs and traditions will not be able to live for as long. The interconnection of heritage is the most critical factor to consider while managing a place’s heritage, such as Kathmandu. Due to their interdependence, the tangible and intangible could not exist independently. Even if they succeed, the heritage’s core will be lost (Maharjan and Filipe Citation2018).

International organizations and many donor nations made commitments to Nepal’s heritage repair. However, the start of the reconstruction was delayed due to fund management and administrative issues (Joshi, Tamrakar, and Magaiya Citation2021).

1.2. Introduction of Thimi

The arrangement of individual homes, neighborhoods, and urban squares, as well as public spaces and structures, all reveal the distinctive architectural and settlement patterns of the valley’s towns. This trend is considered exceptional in South Asia’s various cultural regions (Mohan and Funo Citation2006) Thimi, one of the 31 communities in the Kathmandu Valley, has a history that dates back to the medieval era and earlier centuries. At a distance of eight kilometers (km) to the east of Kathmandu, the current capital city of Nepal, and four kilometers (km) to the west of Bhaktapur, the country’s medieval capital city, Thimi is situated southeast of the Manohara River; a tributary of the Bagmati Thimi was also referred to as Madhyapur throughout the medieval eras Since 1997.

1.3. Cultural heritage conservation principle

According to the 1956 Act for the Preservation of Ancient Monuments in Nepal, the Nara Document on Authenticity, and numerous other international sources, practices and norms must be considered when dealing with the reconstruction of heritage conservation-Principles. These norms offer a framework for project initiation, planning, execution, monitoring, and regulation. It further clarifies that reconstruction should not affect a building’s value, authenticity, integrity, or surrounding area. In addition, the Nara documentation on material authenticity but conservation techniques that could potentially replace the physical carriers of monuments while preserving their essence through the continuation of their communities and their traditional building/conservation methods (ICMOS Citation1994). When this is not practicable, the damage should be modest, and the work should follow heritage conservation best practices (Jha et al. Citation2010).

1.4. Community through reconstruction in literature

Various factors influence community involvement in the preservation of cultural heritage, the scope of heritage, and the identification and adoption of a values-based approach giving voice to a wide range of interest groups and a void left by the waning influence of instructional payers. The growing importance of well-intentioned amateurs in conservation simultaneously weakens the scientific and technical aspects of conservation, and the expertise of experts, including in building crafts and community-based approaches, eventually causes conflict with professional judgments that are either founded on scientific knowledge or are primarily focused on financial rather than emotive values (Orbaşli Citation2017) Another claim is that conservation is now more concerned with processes than products. The expert-centered methods of the past are reversed by consensus decision-making. Thus, supervising the participation process is a task that conservation professionals are increasingly taking on (Orbaşli Citation2017). A demand is created by a diminishing state’s loss of institutional and policy strength and the associated specialist knowledge. On the one hand, community-through bottom-up approaches, volunteers, and creative businesses fill this need. On the other hand, private sector developers and investors fill it (Orbaşli Citation2017)

One Community in the Kathmandu Valley is the Newari. They have lived there since 2000 years ago. They have their native population living in Thimi city.

1.5. Community through initiatives that recreate cultural heritage: then and now

The Kathmandu Valley example offers intriguing details on a non-Western approach to cultural stewardship. A notable example of a community working on historical reconstruction and everyday functions is the Guthi system. The Guthi system is a part of the Newar culture. The pagoda style, distinctive to Newar architecture, is thought to have originated in the Kathmandu Valley and was introduced to China by the Nepali craftsman Araniko during the Yuan era (The Xi Xia Legacy in Sino-Tibetan Art of the Yuan Dyanasty.pdf Citationn.d.) The Newar Guthi system, which is significant, is believed to have existed since the Lichhavi era (kailash_16_Citation0102_04.pdf n.d.; Lekakis, Shakya, and Kostakis Citation2018; Shrestha and Singh Citation1972). A key aspect of Newar culture, the Guthi, a structure for community governance defined by communal organization, existed within the typical urban socio-cultural setting.

After 2015, it has become more common practice to establish Upabhokta Samitis, or “User’s Committee or Groups,” which are formal organizations of people who directly benefit from the operation and implementation of a project. The project must then be developed, run, managed, and maintained by the committee or organization with the law. The Users’ community approach aims to improve the project’s quality, sustainability, and cost-effectiveness. A demographic and consensus-based procedure is used to construct the users’ Community, and a maximum of 11 members can be included with a required 33% female involvement. The primary goals of the users’ Community are to provide jobs and involve the beneficiary community. The users’ Community must provide a particular amount of money or labor to seek government funding for a project. The Community needs a leader in the form of a president, secretary, and treasurer.

The Department of Archaeology (DoA) is the government agency in charge of maintaining, repairing, and conserving public historical sites (Monument, Ancient Citation2013). The restoration and reconstruction of all damaged and demolished historic structures were expected to take six years, costing an average of US$34 million annually. To address the related concerns, the Government announced the creation of public bodies: A community that includes the National Reconstruction Authority (NRA), the Department of the Army (DoA), and local municipalities. These organizations plan and oversee the reconstruction effort.

1.6. Role of Madhyapur Thimi Municipality in this research

To provide technical assistance for the reconstruction of their historic buildings, six communities in Thimi proposed. The details of the renovation plans with the location map of the communities that correlate to these historic buildings serve as case studies. The objective of this support was to protect Newar architecture and cultural history while restoring the damaged legacy using a community-based approach. Communities themselves had to oversee the management of construction-related finances. The City did not influence project decisions, which were all made by the Community. In addition to consulting, the author worked as a conservationist and member of a technical team helping the local communities. The Google locations map for the case studies is provided in .

2. Material and methods

2.1. Case studies-Dyo (Temple) and Phalcha (Rest House)

2.1.1. Wammune Ganesh Dyo (Temple)

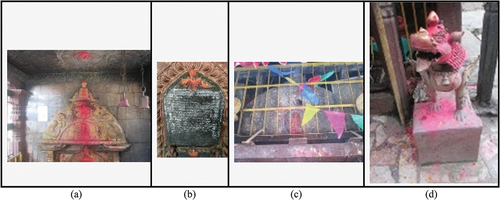

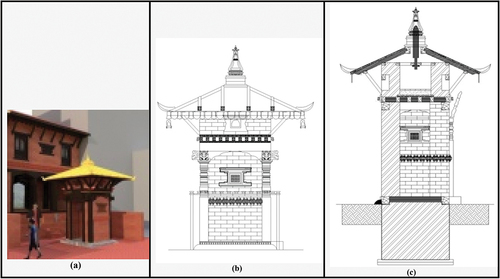

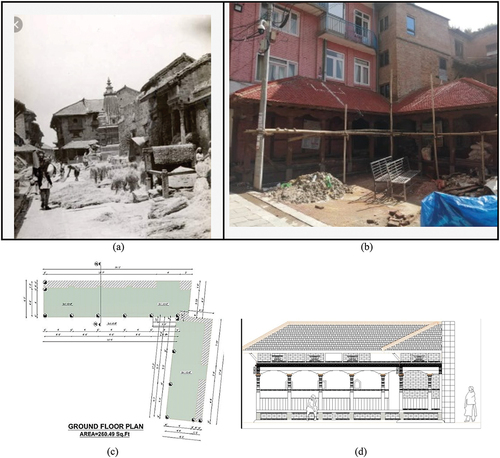

Wammune Ganesh Temple, also known as “BhadeInaya Dyo” is a Hindu Dyo which is located at Madhyapur Thimi, Wammune tole. It lies approximately 80 m east of Balkumari Dyo, dedicated to the lord Ganesh. The Dyo was built during the Shah Dynasty, around the 18th century. Furthermore, it is said that the “Stone” is taken from Gupteshwor and put in the Dyo as the incarnation of Lord Ganesh. The Dyo was constructed in pagoda style with a brick-paved rectangular courtyard and jhingati roof before 1934. Moreover, after the Earthquake, due to damages to the brass toran installed in the roof, it was modified by installing brass plates with gold coating. As shown in .

Figure 3. Picture showing different reconstruction phases of conservation (a) Before the earthquake, (b) after the earthquake construction phase, and (c) Propose Temple after damage by earthquake.

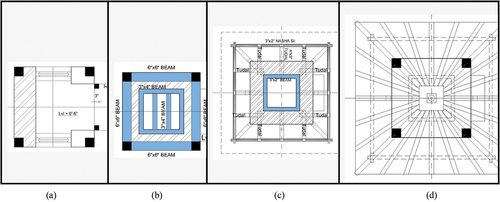

Wammune Ganesh With cubic constructions supported by carved wooden rafters (tundal), the Temple is constructed in the pagoda style of architecture as in . The two-level roofs are made of brass. The Temple resides on a square base platform with a height of 13 feet from base to pinnacle (Gajur). The entrance of the Dyo is in the south direction. Above the doorway is a gold-plated toran with a of the Dyo deities placed right in the middle and the cheppu above it. A pair of brass statue lions guard the gate with .

2.1.2. Lipcha Ganesh

Lipcha Ganesh is a Traditional Pagoda style, Temple. It is also called dyo in the Newar Language. It is located at Bulankhel Madhyapur Thimi Bhaktapur, Nepal. It is a route for Krishna Puja (a celebration by the Community on the occasion of the birth of Lord Krishna) on Krishna Ashtami day.

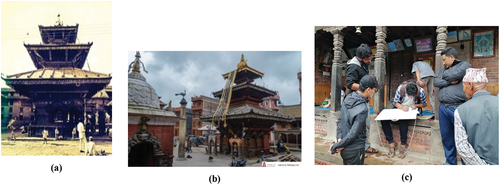

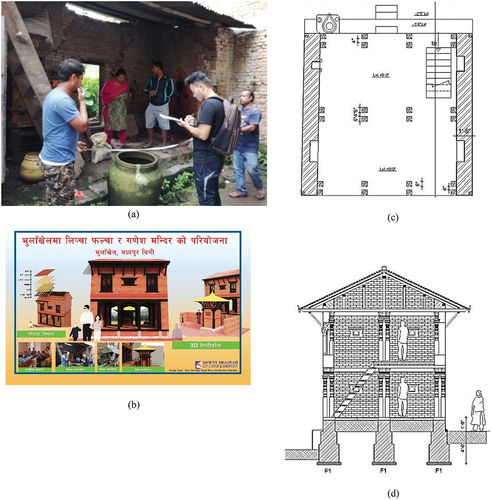

Local young people’s Community was active in reconstructing this Lipcha Ganesh. Firstly, they organized a meeting with local people having older and more experienced people. Through the detailed discussion, they gathered all sorts of information needed for reconstruction works as shown in . Then, they prepared the necessary document for the Lipcha temple reconstruction with engineering consultants’ help as shown in . Meantime, they requested funds from the City, Samsad Bikash Kosh, and other INGO/NGOs. Finally, they received funds from Samsad Bikash Kosh, and the reconstruction work is in progress.

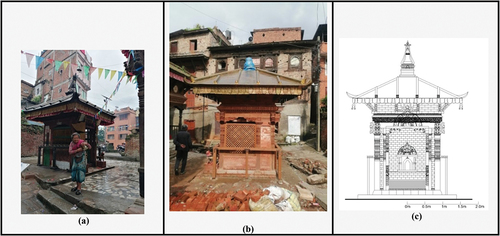

2.1.3. BalKumari Dyo (Temple)

Balkumari temple is located in the heart of Thimi, around 280 m north of the Shankhadhar Chowk. It was constructed in the seventeenth century by King Jagajyoti. Goddess Balkumari is worshiped as one of the Bhairab Shakti. It is believed that only four Balkumari Dyo should reside in the Kathmandu valley. One of four Kumari temples in the Kathmandu Valley is the Balkumari Temple in the Bhaktapur District. In the 17th century, the Temple was constructed. This Temple’s area is the place where the Sindoor Jatra begins. During the festival, locals gather and process 32 floats containing idols of different gods and goddesses. People chant and dance while smudging themselves with vermilion powder and playing Dhimey Baja traditional instruments. The Earthquake badly shakes the Pogoda and significantly damaged its structure. Therefore, the local Community had to put the restoration efforts to bring the Temple back to its original condition. presents the photographs of the Temple regarding the before and after restoration work

2.1.4. Kutu Phalcha (Rest House)

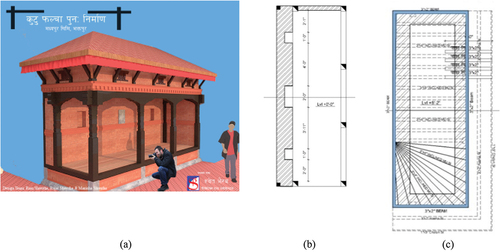

Kutu Phalcha is one of the most traditional and historical movements located at Bhulankhel Tole-5 in the City. The Construction of this monument is traditional pagoda style and made of Mud, Brick, Stone, and Timber. The Temple is a house in a one-story building, and the roof is of Jhingati. The Kutu Community of Bhulankhel makes it as shown in .

Figure 10. Kutu Phalcha (a) Before Construction, (b) After reconstruction and (c) Meeting with user’s community.

History; According to Krishna Bhadur Kutu, Samaya Baji (a particular type of Newari food set) is distributed by the Kutu community in Biska Jatra(Festival) on the last day of Jatra. While celebrating another festival Sakima Puni day (the Newari name of the festival), maize, soya bean, pidalo(taro) etc., as Prasad(snacks) at the end of the bhajan(a kind of musical program)

2.1.5. Lipcha Shattle

Lipcha Shattle is located at Lipcha Chwok, Bhulakel-ward 5 in the City. It has traditional values. Different cultural programs use in this Shattle. The design of this structure is a traditional pagoda style and is waiting for Restoration. Due to lack of budget, it is waiting for restoration shows the details of the structure before the reconstructions and proposed plans.

2.1.6. Manobinayak Falcha (Rest House)

Revitalization of “Monobinayak Phalcha”: an unknown history to the heritage of Madhyapur Thimi. Monobinayak Phalcha is mainly for the Bhajan of the Manobiyak Dyo on Tuesday.

Monobinayak Phalcha is an L-shaped Phalcha located at the Inaya Tole, 200 m north of the Balkumari Temple of Madhyapur Thimi, Ward 4.

Before Construction as Per the photo from social media and different sources, the Monobinayak Phalcha can easily be verified next to the Tah Dyo. We can see it clearly due to the resolution quality of the photo of the time, but we do clarifies it was the lost Phalcha from our cultural history of Madhyapur Thimi as shown in .

2.2. Method

The frequency of natural disasters increased during the past few decades, which resulted in significant losses of human life, physical property damage, and socioeconomic situations in various regions. The country and its development were severely hampered by the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, the 2005 New Orleans hurricane, the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the 2010 Pakistan flood, the 2013 Chinese fire, and the 2015 Nepal earthquake. It disrupted the location’s meaning, leading to a breakdown in how people lived their daily lives (Fields, Wagner, and Frisch Citation2015). The cultural heritage element of the environment has played a crucial role in helping communities cope with these severe disasters (Fields, Wagner, and Frisch Citation2015).

This section outlines the methodology we tracked to accumulate state – of–art research to address the research gap. The research questions are:-

What Examine Post-Earthquake Community Recovery for Urban Heritage Conservation; Case Study of Thimi-Issues and Lessons Learned?

What is the Study of the Procedures for exchanging expertise that was used during the safeguarding of urban cultural heritage?

The research was carried out by following the “Case study method”-:

A careful desk study is performed at the beginning of the study

Interviews with experts and academicians as many as possible

Based on literature reviews and expert interviews,: the three Temple and three Phalchas (Rest House) case was selected for this study

The author also worked as a consultant for these reconstructions – As the author belongs to the Newar Community. It made it more convenient to communicate and understand local people’s sentiments.

The author surveyed with upabhokta community (user community), local stakeholders, and exports.

The collected data were scrutinized thoroughly and used to examine Post-Earthquake Community Recovery for Urban Heritage Conservation and Study the Procedures for exchanging expertise used to safeguard urban cultural heritage.

According to Yin, a case study is an empirical investigation that looks at a current phenomenon in the context of real-world events, particularly when the lines separating a phenomenon from its context are blurred and knowing the local circumstances and how they relate to one another. A Previous study on urban disasters in Nepal has used a qualitative approach to comprehend the context and analyze events (Murakami et al. Citation2014; Punya and Marahatta Citation2013). Suba claims that a qualitative approach is necessary to comprehend the context, reality, and dynamic interplay between human behaviors and willingness. The researcher is both an architect and an urban planner, and during the community assistance program from 2018 to 2022, he had direct encounters with residents of the affected Community.

Documents about the Government’s reconstruction plan, the NRA framework, DoA guidelines, historical records about heritage structures, and agreements between Community Organizations and governmental entities funding the reconstruction were examined.

, provided below, - presents the challenges with the Temple’s and Phalcha’s Communities through the urban heritage conservation process. These tables list the following aspects: 1. Conservation perspective 2. Financial issue 3. Knowledge of conventional building and management techniques 4. Limitation on technical and qualified human resources 5. Social Acton and 6. Bureaucracy and administration requirements were studied and analyzed for Wammune temple, Lipcha Ganesh temple and Balkumari temple, Kutu Phalcha, Monobinayak Phalacha, and Lipcha Phalcha. The local Community led the entire project by forming a user Community. Different projects had different problems; few had funding problems, and few had community conflict issues. Few others had problems with the availability of Construction. Although there were different challenges, local communities could conserve the Temples, Phlachas (Rest House). These projects brought better unity among communities by understanding the situations and working in a team. They revived the traditional built construction technology. All the projects utilized the local construction materials used for the structure construction. These materials comply with the Bureaucracy and administrative requirements.

Table 1. Challenges in Temple’s community-through urban heritage reconstruction: A comparison of three case studies.

Table 2. Comparative comparison of three Phalcha case studies: Phlacha and Seattle’s challenges in community-through urban heritage reconstruction.

compare the cost with traditional and modern construction technology. Similarly, shows labor cost to market and government rate.

Table 3. Compares the costs of reconstructing Dyos (Temple).

Table 4. Comparison of the Costs Involved in Reconstructing Various Phalcha.

Table 5. Comparison of daily labor costs (U.S. $).

Before and during the construction process, Upabhokta Samiti members, including Wammune Ganesh Temple, President of Jeevan Shrestha, Julum Shrestha, President of Monobinayak, Bharat Shrestha, President of Balkumari Renovation, and Shyam Shrestha, President of Kutu Phalcha were interviewed. Before Construction began, they participated in one formal and one informal interview to understand better the difficulties in starting and planning the project.

Understanding an issue involves four main steps: recognizing the problem, determining the key components, identifying potential causes, and assessing cause-and-effect relationships.

3. Results

A Comparative study of three case studies is shown in . Temple (Dyo) and Phalcha case studies – Challenges in the Community through heritage reconstruction, restoration, and renovation reveal the analysis’s findings identifying the principal issues Thimi’s Community experienced during community-through heritage reconstruction. Under one core issue, -numerous other sub-issues are provided. Each sub-issue is addressed to the case study that is used as an example.

provide the details on the conservation of built heritage after the Earthquake and consider the reconstruction by the restoration process.

Different funding sources, such as the municipality budget, provincial government budget, and local self-collection funds, were identified for reconstruction works.

During Construction, different knowledge of conventional building and management techniques was applied. Few projects encountered delays since good quality brick and wood was not readily available. Mostly, top priority was given to using conventional building techniques and materials.

Community members were unclear about traditional architecture’s dimensions, design, and prohibited building materials. This knowledge gap played a role in needing more construction time and budget. The projects have limitations on technical and qualified human resources. Most human resources only know modern technology.

In the past, the building heritage was their own Guthi (a local group). They maintain Temple and Phalcha. But now, after Earthquake. Most of the Post-disaster framework has Upabokta model. This Upabhokta model was implemented in reconstruction, renovation, and restoration.

The user’s Community deals with Bureaucracy and administrative requirements. Since local indigenous people were unaware of Bureaucracy and administration, they struggle in funding mechanisms and had difficulty making the payment on time for construction crew and materials.

compare the costs of various building reconstructions under the case studies. For the Kathmandu Valley, the research presents the issues on the reconstruction of the building Temple(Dyo) and Phalcha(Rest House), demonstrating how a traditional historical structure can cost roughly 2–8 times as much as a reinforced concrete, modern minimalist structure (summing that there is no salvage material available and all building elements are new). This is a limitation or a project element that needs to be considered while preparing any plans for Phalcha, Shattle, and Temple.

The Restoration takes expensive than reconstruction. But the value of heritage is essential, as seen in the Balkumari Temple restoration.

Temple has more detailed carving wood than Phalcha (Rest House). Temple costs more expensive than Phalcha.

Wammune Ganesh Temple (dyo) is the most expensive reconstruction among case studies.

compares the cost of wages daily basis U.S. ($.). The Public Procurement Act of 2064, Clause 148, sets a district, sometimes referred to as a defined tariff for materials and labor services. The government rate per day for skilled labor and craftsman is 9.2 U.S.$; however, the market rate is 15.3US $, and there is a −6.1 U.S.$ difference. In the same way, 2.3 U.S.$ and 17.2US$ are differences in unskilled labor and Jhigati roof tile layer, respectively The User Committee, however, disagreed with the prices of several products, arguing that they do not reflect the current market rate due to the rising costs of heritage building materials and the higher wages for skilled craftsmen. The disparity in prices has a negative impact on the caliber of the work. The cost variation impacts the quality of work. For heritage conservation, the work is measured against the quality of work rather than the construction cost. The quality of work was achieved by expending a lot of effort and resources.

4. Discussion

A 7.8-magnitude earthquake struck Nepal, severely damaging its historical structures. Thimi has also damaged many historical damages and collapsed. According to the case studies that have been looked at, the conclusion can serve as the catalyst and project manager for the heritage protest in Thimi. A similar concept arises when heritage buildings in Thimi are being restored because they are integral to the City’s identity and are linked to its social, economic, and cultural aspects. Apyadin illustrated this point with an example from the African American context.

This reaffirms Fabricatti et al (Fabbricatti et al. Citation2018). Communities’ “consciousness of place” is strengthened by community-led practices, according to a case study of the Italian town of Irpinia. The Upabhokta Samiti model is also in compliance with the goals of the 2015 Sendai Framework and the Burra Charter. This historic reconstruction methodology has increased community involvement, social cohesion, long-term resilience, and productive communities ready for future development projects. Furthermore, actions like transferring the reconstruction of Rato Machhindranath Temple in Bungamati from a private contractor to Upabhokta Samiti show that the GoN is aware of the model’s potential.

The involvement of Madhyapur Thimi Municipality has helped Upabhokta Samiti overcome obstacles such as a lack of competent engineers and architects for heritage protection, a lack of quality control procedures in building, and technical support. These difficulties were cited as a significant barrier to starting and finishing their endeavor. The Community’s understanding and confidence in our heritage repair projects have increased due to this approach of integrating technical assistance with Upbhokta Samiti. In addition to rehabilitating them, Madhyapur Thimi Municipality wants to “convert” the community buildings to scientific activities. It also emphasizes the need for experts or organizations to educate themselves on historical standards and create additional training programs to prepare for the future.

The Upabhokta Samiti model from Nepal is similar in some characteristics to the Machizukuri strategy used in Japan and the Rekompak strategy used in Indonesia. However, the latter two strategies’ political heft and scope of application were not similar to Nepal’s Upabhokta Samiti might of challenges and limitations associated with the widespread usage of the Upabhokta Samiti paradigm. Few differences were identified between these models. The Community Settlement Plan (CSP) approach, similar to the Rekompak concept, firstly lacks integrated neighborhood size planning. Instead of operating on a local scale, the Upabhokta Samiti is focused on reconstructing a single structure or building complex. Second, the geographic scope and amount of funds Upabhokta Samiti can raise have been reduced. Third, Upabhokta Samiti lacks a dedicated “facilitator” who can help with organizational, management, financial, and technological matters. INGOs and NGOs may want to work in this area. Fourth, it was noted that Upabhokta Samiti does not have the support of academia or universities. Intriguingly, researchers from Japanese universities supported the Machizukuri councils in Yamamoto.

One of the takeaways from the Machizukuri approach is that municipalities should be significant stakeholders because they are the ones most familiar with their communities and local features. This phenomenon relates to the concept put forth by Orbasli (Orbaşli Citation2017), which promotes greater cooperation between experts, academics, local Government, and higher-level government authorities. One encouraging development was the Absence of widespread gentrification in Thimi’s historic district. The Community’s sense of ownership over the place may also play a role. The community-based efforts have also made it possible to reinforce communal ownership somewhat. This understanding, however, was made much later in Talca, Chile, after many poor urban residents were forced to flee gentrification and move to a rural location with few basic amenities.

Although the Upabhokta Samiti model from Nepal is encouraging, the difficulties discovered throughout the research prevent it from being scaled up and achieving quality outcomes. The present study highlighted capacity and community knowledge as key determinants of success. Several aspects of knowledge and ability, including skills, norm knowledge, leadership, communication, conflict management, and cross-cultural cooperation and learning, have been highlighted as desirable. Lewer et al (Plan, Master, and World Heritage Site Citation2020). The current study supports the findings by Dohani and Lumbini that community-led processes take time and require long-term commitments to achieve desired outcomes. Other difficulties include a lack of sufficient funds and meeting deadlines for a particular construction project milestone that do not coincide with the work schedule of the Community.

The construction cost of a traditional heritage structure shows an increasing trend. This is because young people are not interested in earning traditional skills. One of the reasons is the government rate. The prevailing government rate is lower than the market rate. Skilled and expert laborers are challenging to recruit, and even if recruited, it is tough to motivate them. The government rate should be reviewed and revised to attract skilled laborers for this heritage conservation mission.

The traditional technique is going to become extinct if awareness program among new generations is not conducted properly. In ancient times, there was a trend of passing skills and techniques from the former generation to younger generations. Mostly professional skills such as handy craft skills, traditional carpentry, and mason skills are transferred to new generations by their parents. This kind of trend is a degrading trend because of limited skilled people and less willingness shown by new generations. Due to the lack of skilled labor and less availability of quality materials, the cost of heritage structure restorations is expensive compared to other structure restorations is expensive compare to other ordinary building structures. The government agency and local communities should put more and more effort into conserving these types of endangered heritage structures regardless of natural disasters like earthquakes or structures’ age-related issues.

5. Conclusion and recommendation

In the aftermath of the 2015 earthquake, Nepal suffered its worst loss of heritage.

Major monuments in Kathmandu’s seven World Heritage Monument Zones were severely damaged and many collapsed. In addition, in more than 20 districts, the disaster affected thousands of private residences built on traditional lines, historic public buildings, and ancient and recently built temples and monasteries, 25 percent of which were eradicated. The total estimated damages to tangible heritage are NPR 16.9 billion (US$ 169 million). The Earthquake affected about 2,900 structures with a cultural, historical, and religious heritage value.

In Nepal, the primary issue with the community-through initiative has been identified among several issues about heritage structure reconstruction, such as the lack of labor and experts, technology, and procurement management. At the most basic level, it is crucial to answer the following questions “Whose is the owner of the Heritage structure?” “Who is Responsibility for Reconstruction?” “Authenticity of Reconstruction” and “Future Owner of these Heritages” If these concerns are collective, all partnering groups agree with the common goals, and the reconstruction process goes smoother.

The Community-based reconstruction process of urban heritages has several implications and difficulties if the management team cannot solve it proactively. Primarily sources are on a technical or political level. This case study identifies many issues of the real reconstruction challenge with the Community-led approaches.

The documentation of heritage structures, which is not also very important for the reconstruction process. Effective reconstruction governance, status quo procurements, and resource scarcity result in complex community-through reconstruction, but the process has increased public ownership of heritage sites and sparked a need for genuine reconstruction.

Different stakeholders, each with their interests, evaluate, investigate, and explain the process. It is imperative to balance the conflicting interests of several parties and conservation and development activities.

Three Temple and Three Phalcha (Rest House) case studies fund insufficient documentation on the heritage reconstruction process. Few documents are available but only for reconstructions and restorations. No reference document is found on the built drawings for reconstructed structures.

All cases are worked out by a community-led model differently. However, all types of projects are conducted by the user’ Community led model.

This study proposes a number of preliminary recommendations that may be useful for the ongoing rehabilitation of Kathmandu’s historic structures conservation. The recommendations are as follows:

Most heritage structures are found in populated regions with active municipal and local administration. The technical, engineering, and architectural capacities of the Government must be proportionately increased.

Timelines in the detailed information circulation and the adequate communication of Bureaucracy and administrative requirements to the Community are required to reduce hurdles in the project’s later stages.

Municipalities should be instructed to reconcile district rates, particularly for historic rebuilding projects that call for higher-quality materials and craftsmanship in harmony with their local communities and context.

It’s crucial to strike a balance between “building back better” and standards for heritage preservation. Communities must understand that modern concrete Construction holds a different set of values from traditional buildings. Initiatives for reconstruction must also adhere to these tenets. It is best to use conventional materials and technologies wherever possible. If it is technically impossible to reduce seismic risk, only unconventional building materials should be used.

Municipalities should allocate sufficient money for cultural preservation to assist efficient construction management. One fiscal year may be insufficient for a trance-based funding paradigm for community-led heritage restoration projects. In such cases, reconstruction efforts should be split into multi-year endeavors or be supported as being of the gradual variety. Deadlines for milestones should be set based on the Community’s work schedule.

The efforts of residents and craftspeople involved in heritage reconstruction must be recognized. The Community’s volunteers, pro bono workers, and craftspeople who continue to preserve and promote our heritage must be honored and cherished by society. For them, the possibilities for appreciation are limited in terms of job security and financial viability;

5.1. Guidelines will ensure successful community-through heritage reconstruction

An initial solid project proposal with thoughtful justification.

The Clarity in plans for adaptive reuse and current, future, and monument use

Clarity about local labor or financial contributions

An expert in historic conservation who serves on a technical partner, user committee, or steering committee

The Community is aware of government regulations and Bureaucracy.

Compatibility among participants so that consensus can be reached more quickly

The user committee’s capacity for collaboration and communication.

The user committee’s ability to resolve disputes.

A system of institutional management for the built heritage. The Community that will benefit should be able to plan for resource management.

Community leaders who are influential.

For the community-led reconstruction strategy to be successful, deficiencies must be identified and fixed. A small user community from the City was selected in this study. The Upabhokta Samiti Model can be scaled up further in villages where residents are still waiting for their historic structures to be rebuilt in the Kathmandu Valley. Further study should conduct the comparison on the reconstruction of heritage structures by new user communities.

Acknowledgements

The researcher would like to thank the former Mayor Madan Sundar Shrestha, Dr. Rajendra Man Shrestha, Dr. Lata Shakya, Dr. Kabindra Kumar Shrestha, Gyani Shrestha, Dr. Rusi Zeng, Mosissa Samuel Tsegaye, and Kabir Khan for their supports. The authors also like to acknowledge the support provided by Manisha Shrestha and Rujal Shrestha on data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Apaydin, V. 2020. Critical Perspectives on Cultural Memory and Heritage.

- Davis, C., R. Coningham, K. P. Acharya, R. B. Kunwar, P. Forlin, K. Weise, P. N. Maskey, et al. 2020. “Identifying Archaeological Evidence of Past Earthquakes in a Contemporary Disaster Scenario: Case Studies of Damage, Resilience and Risk Reduction from the 2015 Gorkha Earthquake and Past Seismic Events within the Kathmandu Valley UNESCO World Heritage Pr.” Journal of Seismology 24 (4): 729–751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10950-019-09890-7.

- Ethos, The Charter, and Cultural Heritage. 1999. “International-Cultural-Tourism-Charter-Managing-Tourism-At-Places-Of-Heritage-Significance-Français-1999.” (October): 5.

- Fabbricatti, katia, Boissenin, Lucie, Citoni, Michele, and Vincenzo, Tenore . 2018. “Community-Led Practices for Triggering Long Term Processes and Sustainable Resilience Strategies. The Case of the Eastern Irpinia, Inner Periphery of Southern Italy to Cite This Version: HAL Id: Hal-01957998 Community-Led Practices for Triggering Long.“ Hal open science.

- Fields, B., J. Wagner, and M. Frisch. 2015. “Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability Placemaking and Disaster Recovery: Targeting Place for Recovery in Post-Katrina New Orleans.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking & Urban Sustainability 8 (1, March): 38–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2014.881410.

- Government of Nepal. 2015. “Nepal Earthquake 2015 - Post Disaster Needs Assessment. Vol. B: Sector Reports.”: 20. http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/SAR/nepal-pdna-executive-summary.pdf.

- ICMOS. 1994. “The Nara Document on Authenticity/オーセンティシティに関する奈良ドキュメント.”

- Jahan, S. H. 2019. Archaeology, Cultural Heritage Protection and Community Engagement in South Asia Communities and Micro-Heritage in Bhitargarh. Bangladesh: A Case Study. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6237-8_2.

- Jha, A. Abhas K., Barenstein, Jennifer Duyne, Phelps, Priscilla M., Pittet, Daniel, and Sena, Stephen . 2010. Safer Homes, Stronger Communities a Handbook for Reconstructing After Natural Disasters Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery Gloobal Facility for Disaster. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-8045-1.

- Jokilehto, J. 2006. “World Heritage: Defining the Outstanding Universal Value.” City & Time 2 (2): 1–10.

- Joshi, R., A. Tamrakar, and B. Magaiya. 2021. “Community-Based Participatory Approach in Cultural Heritage Reconstruction: A Case Study of Kasthamandap.” Progress in Disaster Science 10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2021.100153.

- Kailash_16_0102_04.Pdf. Ancent and Medieval Nepal.

- KC, C., S. Karuppannan, and A. Sivam. 2019. “Importance of Cultural Heritage in a Post-Disaster Setting: Perspectives from the Kathmandu Valley.” Journal of Social and Political Sciences 2 (2). https://doi.org/10.31014/aior.1991.02.02.82.

- Kepe, T. 1999. “The Problem of Defining ‘Community’: Challenges for the Land Reform Programme in Rural South Africa.” Development Southern Africa 16 (3): 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/03768359908440089.

- Korn, W. 1979. The Traditional Architecture of the Kathmandu Valley. Kathmandu: Ratna Pustak Bhandar.

- Lekakis, S., S. Shakya, and V. Kostakis. 2018. “Bringing the Community Back: A Case Study of the Post-Earthquake Heritage Restoration in Kathmandu Valley.” Sustainability (Switzerland) 10 (8). https://doi.org/10.3390/su10082798.

- Letelier, F., and C. Irazábal. 2018. “Contesting TINA: Community Planning Alternatives for Disaster Reconstruction in Chile.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 38 (1): 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X16683514.

- Maharjan, M., and T. B. Filipe. 2018. “Living with Heritage: Including Tangible and Intangible Heritage in the Changing Time and Space.” Journal of the Institute of Engineering 13 (1): 178–189. https://doi.org/10.3126/jie.v13i1.20365.

- McMillan, D. W., and D. M. Chavis. 1986. “Sense of Community: A Definition and Theory. Special Issue: Psychological Sense of Community, I: Theory and Concepts.” Journal of Community Psychology 14 (1): 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629(198601)14:1<6:AID-JCOP2290140103>3.0.CO;2-I.

- Mohan, P., and S. Funo 2006 . “A Morphological Analysis of Neigh- Borhood Structure -toles and The Ritual Artifacts Of The Kathmandu Valley Towns- The Case of Thimi Mohan Pant 1 & Funo Shujf The Town Of Thimi- Geo.”

- Monument, Ancient. 2013. “Ancient Monument Preservation Act 2013, AmendBant Rules. Preamble: - Whereas.”: 1–6.

- Murakami, K., D. Murakami Wood, H. Tomita, S. Miyake, R. Shiraki, K. Murakami, and K. Itonaga. 2014. “Planning Innovation and Post-Disaster Reconstruction: The Case of Tohoku, Japan/Reconstruction of Tsunami-Devastated Fishing Villages in the Tohoku Region of Japan and the Challenges for Planning/post-Disaster Reconstruction in Iwate and New Planning Challenges for Japan/Towards a “Network community” for the Displaced Town of Namie, FukushimaResilience Design and Community Support in Iitate Village in the Aftermath of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Disaster/Evolving Place Governance Innovations and Pluralising Reconstruction Practices in Post-Disaster Japan.” Planning Theory & Practice 15 (2): 237–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2014.902909.

- Murakami, K., D. Murakami Wood, H. Tomita, S. Miyake, R. Shiraki, K. Murakami, K. Itonaga, and C. Dimmer. 2014. “Planning Innovation and Post-Disaster Reconstruction: The Case of Tohoku, Japan/Reconstruction of Tsunami-Devastated Fishing Villages in the Tohoku Region of Japan and the Challenges for Planning/post-Disaster Reconstruction in Iwate and New Planning Challenges for Japan/Towards a “Network community” for the Displaced Town of Namie, FukushimaResilience Design and Community Support in Iitate Village in the Aftermath of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Disaster/Evolving Place Governance Innovations and Pluralising Reconstruction Practices in Post-Disaster Japan.” Planning Theory & Practice 15 (2): 237–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2014.902909.

- Orbaşli, A. 2017. “Conservation Theory in the Twenty-First Century: Slow Evolution or a Paradigm Shift?” Journal of Architectural Conservation 23 (3): 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556207.2017.1368187.

- Plan, Master, and World Heritage Site. 2020. “Durham E-Theses.”

- Posio, P. 2019. “Reconstruction Machizukuri and Negotiating Safety in Post-3.11 Community Recovery in Yamamoto.” Contemporary Japan 31 (1): 40–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/18692729.2018.1556495.

- Punya, B., and S. Marahatta. 2013. “Community-Based Earthquake Vulnerability Reduction in Traditional Settlements of Kathmandu Valley Community Based Earthquake Vulnerability Reduction in Traditional Settlements of Kathmandu Valley.”

- Shrestha, B. K. 2001. “Transformation of Machendra Bahal at Bungamati.” 1–15.

- Shrestha, R. 2021. “Community Led Post-Earthquake Heritage Reconstruction in Patan–Issues and Lessons Learned.” Progress in Disaster Science 10:10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdisas.2021.100156.

- Shrestha, D. B., and C. B. Singh. 1972. The History of ancient and Medieval Nepal in a Nutshell with some Comparartive Teraces of Foreign History 1972.

- Singh, S. K. 2013. “Buddhism and Law.” ABC Research Alert 1 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.18034/abcra.v1i1.244.

- UNESCO. 2006. Cultural Heritage & Local Development. Africa.

- The Xi Xia Legacy in Sino-Tibetan Art of the Yuan Dyanasty.Pdf.