ABSTRACT

The seaweed cottage is a traditional residence in the Jiaodong (胶东) region that has existed for hundreds of years. During its development, its architectural form was evidently reconstructed and redeveloped. Based on historical documents, interviews, field investigations, and mapping, the author summarizes the village environment, overall layout, and architectural attributes of Dongchu Island Village (东褚岛村, DIV) to address the common needs of historical heritage protection. In order to examine in depth, the spatial evolution of the five stages in the past one hundred years, the Wangs’ grocery seaweed courtyard located on the southwest corner of Middle Street was selected as a typical research object. Analyzed as two clues, the village and dwelling, three key factors are identified as influencing spatial change: Characteristics of the time, economic industry, and personnel structure.

1. Introduction

The village presents a stage in a long evolution process, and the dwelling, as the main constituent, is constantly changing (Yuan Citation2003). With the advancement of China’s rural strategy, it is also of profound significance to explore the deeper structure and development patterns of residential houses (Jin and Zhang Citation2019). Meanwhile, the research on the mechanism of influences on spatial evolution expanded towards a multidimensional approach,such as typology (Li Citation2019), geography (Zhu Citation2009), and cultural studies (Huang Citation2018). These studies have profound implications for rural construction in the new era.

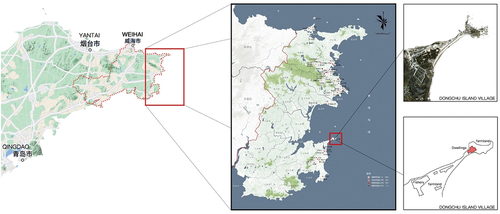

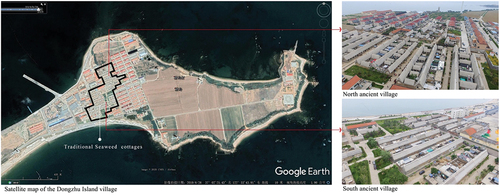

Seaweed cottages (海草房) are the typical dwellings in the Jiaodong(胶东) Peninsula region. Influenced by the LaiyiFootnote1 (莱夷) culture, it adapted to the marine climate and local humanistic traditions (Lu Citation2008). DIVFootnote2 is a typical fishing village in the Ningjin Sub-district of Rongcheng, Shandong (山东荣成宁津街道) (). There are 10 kilometers of coastline and 125 hectares of land (Ding, Feng, and Zhang Citation2022). Surrounded by the sea, the overall terrain is low in the southwest and high in the northeast (). Traditional seagrass dwellings are concentrated in relatively flat terrain in the west (Liu Citation1990) ().

The research on seaweed cottages started relatively late, generally focusing on four levelsFootnote3 residential units, courtyard groups, single villages, and rural settlements. The research is divided into the following three categories: a). Research on the ontology of vernacular architecture (dwellings): Sun (Citation2004), Lu (Citation2008), and Chu, Xiong, and Du (Citation2012) give a general introduction on China’s vernacular buildings by districts, with a brief description of seaweed cottages from the perspective of the spatial layout, material structure, construction, and technique. b). Research on ecology and its modern application: Galan et al. (Citation2020) analyzes the ecological attributes of Seaweed cottages as an example of ecological bionics; Yang (Citation2011) conducts an in-depth interpretation of the material structure of seaweed houses based on the cultural and geographical environment. c). Research on protection and renewal: Liu (Citation2009) puts forward suggestions for the overall classification and classification of seaweed houses; Chu, Xiong, and Du (Citation2012) discusses the protection and planning mode and proposes a dynamic cycle protection strategy based on the perspective of ecology and tourism.

The reviewed literature reveals that despite the many descriptions of traditional dwellings in Jiaodong and the spatial evolution of vernacular settlements, there is a need of integrative research combining these two aspects and factors explaining its occurrence. Two questions are put forward in this research: 1) Are there any changes in seaweed cottages and village regarding spatial configuration? 2). How do connected factors work on the village and dwellings at same time during this spatial evolution?

2. Material, methodology, and research design

To answer the two questions above, this paper proposes a model that combined both inductive and deductive research strategies towards the overall village and the typical dwelling to explore the influence factors associated with spatial through supported materials, such as investigation, interview, mapping, and comparative analysis.

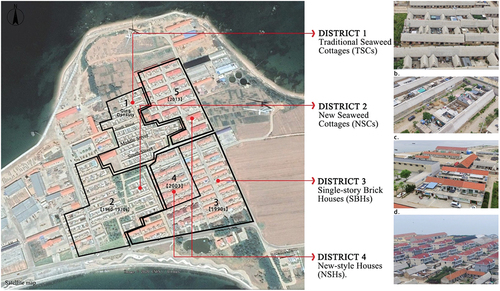

In detail, the research model is composed of two objects connected and combined with common influence factors (). The first object is the village elaborated from temporal phases, multiple dimensions, and expanded domains based on relevant literature, investigation, and interviews. The dwellings in DIV are classified into four zones based on historical materials (e.g., county annals, ancient books) and investigation (e.g., natural environment, historical development, current situation, functional zones, street organization). The second object is the dwellings analyzed on spatial stages, architectural attributes, and development characteristics through investigation, mappings, interviews, and historical literature. A representative traditional dwelling with continuous evolution and inhabited by five generations is selected for in-depth research.

By combining these two clues on village scale and unit residential scale, the research results are obtained and the common influencing factors on two levels of group settlement and family individual are discussed to explore the evolution mechanism on village planning and architectural space. This research hope to provide suggestions for rural reconstruction and spatial development.

3. Results

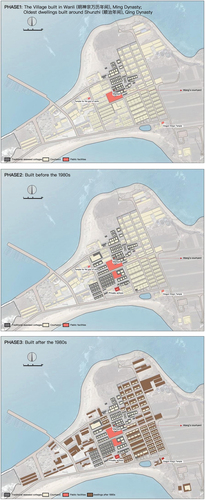

3.1. The village: general spatial evolution of the DIV

Three Phases (): Phase 1: During the Shunzhi period of the Qing Dynasty, in order to resist the sea wind and tide and facilitate daily life, the living space was concentrated in the northeast and southeast thanks to the terrain. An open-air market was the core space in the early days, and the Dragon King Temple and the Earth Temple were built later, which symbolized the spiritual cohesion of the clan. Phase 2: Before 1949, the residential area occupied the center of the island, with fishing areas surrounded. In addition, the first education school (the predecessor of DIV Primary School) was built. During the 1970s, a major relocation occurred. Traditional houses in the east were demolished and residents moved into new seaweed houses in the west, forming a horizontal development trend. Phase 3: After the 1980s, since the immigrant influx due to the continued boom in the fishing industry, DIV committee dedicated to the construction of water conservancy and expanded the west into a new residential area. Since 2000, the road around the sea and the factory buildings of seafood companies in the northwest have been newly built, as well as public buildings such as auditoriums, schools, museums, etc. have been added. The previous spatial layout has been maintained. Most public spaces and infrastructure, such as temples, drainage ditches, and ancient wells, have been restored and protected.

In summary, regarding the changes in village space, the basic pattern composed of residential space, public space, and traffic space has been formed before the founding of the People’s Republic of China. The expansion of space and the complexity of functions mainly occurred after the 1980s, leading to a clear and orderly spatial structure. The scale of the dwellings gradually expands (), expanding westward from the central traditional dwellings; the public space evolves from a single core to a multi-core model. Ancient streets are preserved, and new traffic is planned.

Table 1. Three phases of the evolution of DIV.

Four domains: Based on the field investigation and interviews, the author classified the existing dwellings into four types according to the construction style: 1). Traditional Seaweed Cottages (TSCs), 2). New Seaweed Cottages (NSCs), 3). Single-story Brick Dwellings (SBDs), and 4). New-style Dwellings (NSDs). Different forms present collective memory and historical changes (). DIV was built in the Wanli(万历) period of the Ming Dynasty (1573–1620) (Jiao Citation2009). The existing TSCs located in the north of the village with limited scale were built in the Shunzhi(顺治) period (1644–1661) of the Qing Dynasty (Liu Citation1990). With social stability and population growth, the village gradually developed westward in the 1960s and 1970s, with stone structures and seaweed thatch as roofs. NSCs were generally constructed during this period. The courtyard of NSCs still maintained the traditional layout, but only the main room retained seaweed thatch as a double-slope roof, while the wing and inverted rooms were generally built in flat-roofed cement, which facilitated drying grain; In the 1980s and 1990s, SBDs with red brick were built on the south side of the village; Later, in 2003 and 2013, there were two large-scale constructions of two-story NSDs, during which most residents moved into NSDs with complete facilities. However, the construction of NSHs had a certain impact on the traditional style of Seaweed cottages; in 2018, with the proposal of China’s “Rural Revitalization” national strategy, the protection and tourism development were emphasized (Ding, Feng, and Zhang Citation2022).

Other Dimensions: The layout shows North Street, Middle Street, and South Street as the core structure. Dwellings and lanes are completely organized with public space and landscape greening (). The Huoshan(伙山)Footnote4-style residences make the village form a compact spatial texture (Li Citation2004) (). The arrangement of the streets and courtyards is conducive to resisting the cold wind in winter from the ocean, as well as ensuring sufficient shade in summer. This traditional type minimizes the impact of external influencers and creates a comfortable physical environment inside the village (Liu Citation2009; Yang Citation2011) (). In order to adapt to the coastal climate, rows of seagrass houses are connected to each other, and the distance between streets and buildings is small (). According to the author’s field investigation, traditional seaweed cottages are mainly composed of a courtyard with three sides or four sides, and these courtyards are relatively small and closed, consisting of main rooms(正房), wing rooms(厢房), and inverted rooms(倒座房) (). The heated kang in the second room is the center of the indoor layout in the Jiaodong area, and it is the center of family communication activities and a place for entertaining guests. The east and west wing rooms are generally two or three bays, and the inverted rooms in the south room are mostly connected to the gate of the house. There are many forms of entrance gates, which can be divided into doorway type(门洞式) and wall type(墙垣式) (Ma, Cui, and Wu Citation2021)(). The construction of the seaweed cottages uses local materials and makes full use of natural resources sustainably. The wall and roof materials are local dark-red granite and purple-gray seaweed from the seaside, warm in winter and cool in summer, with excellent physical properties (Yang Citation2011) (). The construction process of traditional seaweed cottages requires the cooperation of craftsmen in five different fields (Chu, Xiong, and Du Citation2012). It is a unique set of multi-work cooperation construction skills systems (Ma, Cui, and Wu Citation2021; Li Citation2004).

3.2. The dwelling: specific spatial evolution of one courtyard

It can be seen from the above that in DIV, only Area 1 and Area 2 maintain the traditional seaweed house style, while the single-storey brick courtyards and new-style houses in Areas 3 and 4 no longer have the characteristics of typical seaweed houses (). Therefore, this study focuses on the traditional seagrass houses in Area 1 with the longest history and explores the spatial evolution of dwellings vertically; at the same time, it is supplemented by comparing typical cases in Areas 2, 3, and 4 horizontally. shows the four main districts in which district 1, traditional seaweed cottages (TSCs) span cross over one hundred years. This area is the most traditional one showing the typical evolution of seaweed houses. Therefore, we select one courtyard to explore how spatial configuration changes and what are the main drivers.

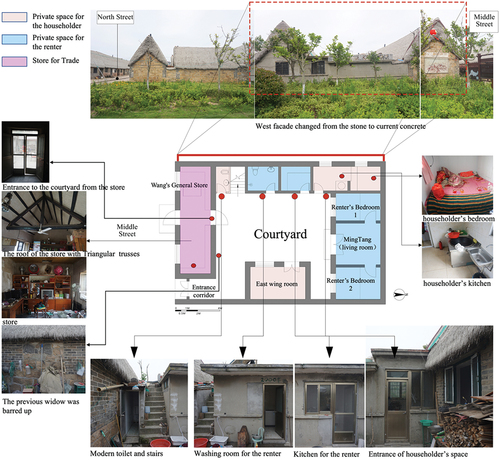

Wang’s Grocery Store () has undergone significant adjustments in its overall layout, material structure, and functions over the past century with time changes, industrial transformation, and personnel structure. In detail, the walls are built of irregular stones with a natural assemblyFootnote5 principle. Bricks are only used at the corners. The windows decorated with paper cuts are old-fashioned wooden lattice windows(木棂窗) (). The courtyard is composed of the main room, the east and west wing rooms, and the inverted room which is now a grocery store (), holdings four generations (): The main room is 3.5 meters deep and 11.2 meters long, and the side rooms are 2.5 meters deep ().

Figure 13. External and internal space status of the new flat roof building after the demolition of the west wing.

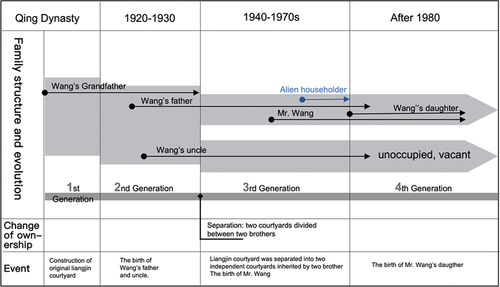

Based on interviews, this paper concludes five stages of spatial evolution (, ).

Table 2. In the past hundred years, Wang’s grocery store has changed its layout, economic industry, and personnel structure during five stages.

Stage 1 (), Before the founding of the P.R.China: The original courtyard was the typical second-entry dwelling owned by a feudal landlord family during Qing Dynasty, owning to Mr. Wang’s grandfather (). The front and rear courtyards are connected by the corridor. And then after a few years, Mr. Wang inherited the south courtyard facing south thanks to the division of property with Mr. Wang’s uncle inherited the north courtyard. The aisle enclosed by the brick wall changed to a storage space for stacking fodder and tools on account of livestock and farming. An open-air toilet is in the southwest corner of the courtyard due to the traditional lifestyle currently.

Stage 2 (), the 1970s: After the founding of the PRC, the inverted houses along the street were confiscated and redistributed under the taken of land policy. This courtyard changed to hold two families, and the inverted room belongs to alien single-family residence (). As a result of the need for privacy, the windows of the inverted room facing the inner courtyard were sealed with stones, leaving only the door opening, followed by a new door opening along the street.

Stage 3() the 1980s: In 1985, due to the industrial transformation and the demands of individual economic production, the original small courtyard could not meet the needs of drying the crops and seafood, so the householder rearranged the courtyard: West wing was demolished and a new cement room with flat roof maintained as a drying platform with nine steps from the ground are built.Footnote6 The previous forage space is connected to the newly built one-story cement room, and the whole is divided into two parts used as a closet and kitchen respectively. In 1988, the householder bought back the inverted house and used it again as a bedroom. In the interior, the ceiling is installed, covering the cushion made of wheat and straw on the original “eight-shaped wood(八字木)” beam structure.Footnote7 This solves the long-standing indoor ash fall problem. At this time, rural mechanization has been popularized, and traditional farming livelihood has turned to mechanical harvesting.

Stage 4 () 2000-the 2020s: In 2003, the householder knocked down the walls in the inverted house for a complete space to operate Wang’s grocery store along the street. Subsequently, in 2018 the national “rural revitalization” strategy(乡村振兴战略) comprehensively promoted the construction of new countryside, and also proposed a rural toilet revolution. Wang’s Grocery Store underwent toilet renovation with the support of government funds.

Stage 5 () Present: In 2019 there was a renovation for the family-style homestay. With the increasing popularity of DIV, most of the well-preserved traditional seaweed cottages in the village have been transformed into scenic spots or homestays with the support of the state and tourism agencies, such as the Village Memory Museum and the high-end homestays under the operation of Tangxiang(唐乡) which is a chain brand. Following this trend, Wang’s Grocery Store renovated its dwelling into a family-style homestay, which is managed by two elderly people. The three rooms in the main block are used as the living room and bedrooms for renters; the original three rooms in the west wing had been enlarged into four rooms with two rooms on the south side having added doors and windows according to the needs, and they are respectively used as toilets and kitchens for renters (); the other two rooms on the north side are the old people’s bedroom and kitchen, and a new door is opened, and two windows are added on the west wall to ensure the lighting and ventilation of the host bedroom (), which are storage room and grocery store respectively. The west facade of the current courtyard of Wang’s Grocery Store is significantly different from that of the northern courtyard before the separation in the 1970s (). The north courtyard has less reconstruction, keeping the original stone materials while the south courtyard has a completely new construction with cement, accompanying two new windows.

4. Discussion

This paper conducts inductive and deductive research on spatial evolution and reconstruction in DIV from two scales through investigation, interviews, and mapping. One is the village and the other is the specific dwelling. Three temporal phases and four districts are composed of the basic structure of the DIV. As a supplement, analysis of multiple dimensions, such as regional environment, history, industry distribution, streets, and architectural features in this settlement elaborate obvious evolution in the past century. In contrast, the five-stage spatial evolution and the shifts of architectural attributes in Wang’s grocery store is a small and progressive development model from the late Qing to the Modern. The following three associated influence factors evoke these changes reflected in spatial configuration and cultural landscapes:

4.1. Characteristic of time

a). The Village: Policy and Planning

The characteristics of The Times put forward new policies, and then affect the village spatial Planning. The DIV gradually spontaneously formed the basic pattern according to the natural conditions and living needs during the Qing dynasty, with most residences in Shandong being passed down as generations (Li Citation2004). National policies guide the adjustment of the economy and industry to improve productivity and infrastructure in the urban areas since 1949, the rural areas had fewer new houses affected by economic development and political movements (Liu Citation2009), While around 1980 and 2000 there were two upsurges in rural construction in Shandong under the guidance of the construction of the new socialist countryside (Li Citation2004; Liu Citation1990). However, the construction of homogeneous brick and tile houses has damaged the seagrass house style in the DIV to a certain extent (Chu, Xiong, and Du Citation2012; Harley et al. Citation2012). With the implementation of various policies to enrich the people after 2000, the appearance of rural residences has changed significantly for the sake of new materials and structure (Ma et al., Citation2021). Recently, the government paid close attention to the protection and development of traditional villages and organizes relevant planning to protect architectural features, cultural spaces, and social customs. In 2007, DIV was selected as the third batch of “Chinese Historical and Cultural Famous Villages” by the Ministry of Construction and the State Administration of Cultural Heritage since it completely retains the landscape of the traditional seaweed village. At the same time, capital is encouraged to promote sustainable rural development (Ding, Feng, and Zhang Citation2022).

b). The dwelling: Lifestyle and spatial configuration

The characteristics of the times change the way of life, and then affect the living space. The living space is constrained by clan etiquette and family ethics (Li Citation2019). With the enrichment of material conditions and the diversification of living requirements, the living space develops from single to complex, from single-storey to multi-storey. In detail, the space is first reorganized and expanded horizontally and then continues to be complicated vertically, finally meeting the needs of physiology (survival, production places) and psychology (culture, leisure places) (). The purpose is to pursue the relative independence of each functional space and improve efficiency and quality of life (Wang et.al., Citation2016). Furthermore, the introduction of modern furniture, household appliances, cooking utensils, heating equipment, sanitary facilities, and the independence of space. However, the juxtaposition of old and new construction methods results in mixed architectural styles; it caters to urbanized lifestyles and gradually weakens regional culture (Zhu Citation2009). In summary, economic development has brought improvements in people’s living standards and changes in spatial demands. The depth and height of the traditional seagrass houses are limited because the stone wall constrained the size of the door and window openings, making the window-to-wall ratio of the traditional seagrass house less than 20%, which cannot meet the needs of modern life for natural light and wind (Liu and Tian, Citation2023). In addition, air conditioning, the comprehensive promotion of heating materials, as well as the construction convenience, make people turn to new techniques. As a result, many seaweed cottages in Jiaodong have been demolished recently and replaced by reinforced concrete buildings, and the stone wall system with the chimney system has also disappeared.

4.2. The shift of industrial structure

a). The adjustment of industrial structure affects the village space:

Under the advantages of coastal geography and resources, DIV has extensive access to market, capital, transportation, and information factors, driving industrial transformation and forming a trend of coordinated development of agriculture, aquaculture, and tourism with fishery production as the core. Early residents of DIV made a living by fishing for generations; driven by the fishing industry, DIV extended to seafood processing, kelp farming, ship repair, and shipbuilding. In recent years, the east and west of the island have been developed, forming a pattern of cultivated land in the east and residential areas in the west (). At present, the primary industry is dominated by aquaculture, and the secondary and tertiary industries are dominated by seafood processing and tourism. The collective income and per capita income of village residents are at a relatively high level (Jin, 2019).

b). The change in industrial structure affects the residential space:

There are differences in the production behaviors of the residents, and the industrial orientation directly affects the choice of housing space by the living actors (Che Citation2017; Ma Citation2018; Sun Citation2004). The transformation of the living space needs to adapt to the production and labor of the households. The economic industry in DIV has transformed into a composed industrial structure where fishery, agriculture, and tourism coexist, which in turn led to the transformation of the living environment to meet complex demands. For instance, in the 1980s when the structure of the west wing was reconstructed from traditional masonry and seaweed to a brick-concrete flat roof room. In addition, the west wing was also connected to the main room in the shape “L”, maximizing space utilization. Since then, the building structure has not changed, and the space layout separation, door openings and windows, and interior decoration had been always adjusted appropriately with the changes in residents, production, and lifestyle.

4.3. The mobility of personnel composition

a). From the perspective of changes in village population structure:

The DIV, as the seaside traditional villages, have a relatively little outflow of population, whereas an inflow of population, resulting in complicated occupations and social relationships. According to the “Rongcheng County Chronicles” (Liu Citation1990), before the Qing Dynasty, DIV was a stronghold of coastal defense. Fishermen from nearby villages moved in and settled down in farming and fishing. From the end of the Qing Dynasty to the 1950s, more than a hundred households with the “four major clans” as the core began to conduct construction activities. Since the 1980s, the number of villagers engaged in farming is small, mainly engaged in fishery business and tourism services. In addition, the government, developers, tourism companies, and tourists have become part of the village staff. The government manages the construction of infrastructure, new rural communities, public service facilities, cultural facilities, etc., and foreigners gradually enter the tourism development and real estate of traditional villages. Generally speaking, changes in population size, population flow, and population structure have certain impacts on the scale and spatial layout of villages.

b). From the perspective of changes in the structure of family members

Traditional dwellings follow the traditional etiquette and ethics system, and the family is used as the unit to allocate space. The courtyard is the activity center of a family. In order to increase the function, the spatial structure of the courtyard has been reorganized, such as the re-separation of wing rooms, corridors, and inverted rooms; after the reform and opening up, there is a large outflow of population, the aging is serious, and the living concept of the elderly is relatively conservative. The demand is single, the space requirements are not high, and the residential space has not changed much, mainly the renovation of the bathroom space. In addition, driven by the development of the individual economy, housing has formed a form of “commercial and residential integration”. In terms of architecture, the original upside-down houses along the street were transformed into shops. Thanks to the reform in 1978, the demand for labor force in mechanized production has decreased, as a result, the structure of residents changed accordingly. Middle-aged and young people prefer to live in new-style residential buildings with convenient facilities, resulting in smaller family sizes. However, around 2010, with the development of the tourism industry, there was a small-scale return of the population. In addition, the head of the household remodels the house to meet the needs of tourists, and the space quality varies greatly: the rooms rented out are mostly located in the main room, with a large area and high space comfort, while the rooms where the head of the household (mostly elderly people) live are mostly located in the wing rooms (). The space is compact and narrow, only meeting the minimum living needs.

5. Conclusion

Through the analysis of the two scales of village and unit living space, this study finds that the characteristics of the times, industrial structure, and personnel composition are the main factors of spatial evolution.

From the perspective of the overall spatial evolution of the village, DIV has gradually transformed from a traditional residential village to a cultural tourism village, and its function has changed from serving production and life to serving tourists. The scale of the village has expanded to meet the needs of different industries, as well as the complexity of the population structure. Features of village spatial form evolution with social development as the main factors: In the period of natural economy, the natural environment and clan culture are gradually developed according to the situation and family groups; During the planned economic period, political policies, production, and living places were the center, and housing expanded to the surrounding areas; During the period of economic transformation, villagers have the right to use the land, a wave of large-scale modernization appears, traditional dwellings are updated rapidly, and the spatial form of villages changes greatly; In the period of market economy, the economic industry and planning, the industrial structure has been adjusted, and the villages have developed orderly under the guidance and control of relevant planning.

From the perspective of the evolution of living space, some houses have been transformed into public service facilities in order to meet the needs of the tourism industry. Wang’s Grocery Store has transformed from a traditional dwelling to a complex of catering, accommodation, and retail dwellings. At the architectural level, this transformation is manifested in functional space replacement, façade change, structural replacement, courtyard landscaping, spatial organization change, skin, detail treatment, etc. The construction methods for the transformation of residential buildings are demolition and reconstruction, addition, reconstruction, and decoration. Most tourist residential buildings can be based on traditional prototypes in design and practice. To sum up, in the process of village transformation, more spatial construction and morphological changes have occurred in residential courtyards. In the final analysis, these changes are influenced by people, or local governments, developers, villagers, foreign merchants, tourists, etc. The outcome of stakeholder games.

Limitations of this study: In the study on the scale of residential buildings, only the courtyards with the oldest history were selected for in-depth spatial evolution analysis, and the spatial evolution of residential buildings built in other eras could not be compared horizontally. In addition, although the “gradual” traditional houses transformed into homestays and retail occupy an overwhelming number of existing houses, there are still some traditional houses whose property rights belong to the government and have been transformed into folk museums and exhibition halls. The spatial evolution model is ““mutant type”; or some dwelling owners are still engaged in traditional agriculture and fishery, and the space evolves into a “constant type”. These two types are also worthy of study. Regarding the discussion of influencing factors, this article selects three main factors for discussion based on literature and interviews, but there are other correlation factors, such as living culture, geographical conditions, climate, clan, etc.

In addition, this study has the following implications for the spatial renewal of traditional dwellings: First, the continuation of daily life production. The development of the times and social changes have impacted the traditional way of life and production in the region. But no matter how it changes, all kinds of life and production events are closely related to the change of space, so as to maintain its continuity, maintain the constancy and inheritance of space; second, excavate the core of traditional spirit. In the new rural construction process, the traditional core is the key to maintaining the psychological support and emotional memory of the local people; third, the construction of a sense of identity and belonging. In the process of protection and development, various means are used to deepen the environment, create an atmosphere, combine regional characteristics, and build a sense of spatial identity and belonging. It is hoped that through this study, guidance and suggestions can be made on the preservation and development of spatial forms, and on the problems and impacts of changes in spatial forms caused by modern lifestyles.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kaiyue Ma

Kaiyue Ma is a Ph.d. candidate interested in China’s foreign-aided architecture and vernacular dwellings in China

Tong Cui

Tong Cui is a professor in the UCAS, interested in urabn design and architectural theory.

Yan Wu

Yan Wu is an associated professor in the UCAS, interested in vernacular dwellings and geographical landscape

Wei Chang

Wei Chang is an associated professor interested in planning and stadium

Hanxiao Zhu

Hanxiao Zhu is a designer

Notes

1 Laiyi Culture: In the Spring and Autumn Period (春秋时期), there were two countries, “Lai” (莱)and “Yi”(夷) in the Jiaodong region. Laiyi culture is the original culture of this region. The most prominent feature is the oceanic nature, such as being prosperous because of the sea, fishing, and living by the sea. Laiyi Cultural District is dominated by the fishery and salt industries. See reference [1] for details.

2 There are 189 registered households with 437 registered persons. Among these 167 households lived in the seaweed cottage, 42 households in the brick residence, and 119 households in new-style houses. This historical information and data come from the rural memory center and village committee of DIV, Rongcheng, Weihai. The data information is the basic situation on November 19, 2018.

3 This conclusion is based on the author’s summary of 78 journals, 18 master’s theses, and 2 doctoral theses with “seaweed house” as the research subject from 2010 to 2022.

4 Huoshan(伙山), also known as Jieshan(接山), refers to the form of a row of residential houses that are connected to each other to form gables and gables, with thatched roofs connected to thatched roofs.

5 In the era when stone mining and grinding tools were backward, traditional craftsmen used the principle of “bottom is big and the top is small, adapt square with round” for building, relying on accumulated experience to combine irregular stones, and then outline them with white ash. These ash seams are very eye-catching, and the appearance of the seaweed with rough stone walls is very vernacular and regional.

6 In recent decades, wing rooms have been reconstructed into flat-roofed rooms in many places. This kind of flat-roofed wing room is mostly built on the corner of the courtyard facing the street. It is made of stone strips and prefabricated cement boards. It is sturdy and practical; there are stairs on one side to go up to the roof. In winter, you can also store items, which is very convenient, so it has been quickly promoted in rural areas.

7 The roof structure of a seaweed cottage is mainly divided into the back of the thatch, the eaves, the thatch layer on the slope, and the ridge. The back of the thatch refers to the process of laying the fence directly on the purlins. Most of the materials used are economic crops with strong toughness and low price, such as weed grass and wheat straw (Yang Citation2011).

References

- Che, Z. 2017. “The Evolution of Spatial Form from a Traditional Village to a Small Town in Tourism Development.” Tourism journal 32 (1): 10–11.

- Chu, X., X. Xiong, and P. Du. 2012. Discussion on the Protection and Planning Model of Seagrass House Characteristic Residential Houses——Taking Chudao Village as an example 2012 (06): 36–39.

- Ding, Y., X. Feng, and Y. Zhang. 2022. “Regional Expression of Local Building Material System in Modern Architecture——Taking Seaweed Houses in Jiaodong Peninsula as an Example.” Architecture & Culture 8:200–202. https://doi.org/10.19875/j.cnki.jzywh.2022.08.068.

- Galan, J., F. Bourgeau, and B. Pedroli. 2020. “A Multidimensional Model for the Vernacular: Linking Disciplines and Connecting the Vernacular Landscape to Sustainability Challenges.” Sustainability 12 (16): 6347. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166347.

- Harley, C. D., K. M. Anderson, K. W. Demes, J. P. Jorve, R. L. Kordas, T. A. Coyle, and M. H. Graham. 2012. “Effects of Climate Change on Global Seaweed Communities.” Journal of Phycology 48 (5): 1064–1078. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-8817.2012.01224.x.

- Huang, Y. 2018. Study on the Morphological Evolution of Zhangzhou Traditional Villages under the Intersection of Multi-cultures. Thesis, Guangzhou: South China University of Technology.

- Jiao, H. 2009. Investigation and Research on the Preservation Status of Weisuo in Ming Dynasty in Weihai Area, Master’s thesis, Jinan: Shandong University.

- Jin, Y., and P. Zhang. 2019. “Study on Evolution of Tibetan Diaofang in Make River Basin of Sanjiangyuan Region from the Perspective of Topology.” New Architecture 2:119–12.

- Li, W. 2004. Qilu Residences. Shandong, China: Shandong Literature and Art Press. Shandong Literature and Art Publishing House.

- Li, X. Y. 2019. Study on the Skill of Jiaodong Hai Thatched House “Shanjiang”. Wuhan, Hubei, China: Huazhong University of Science and Technology. https://doi.org/10.27157/d.cnki.ghzku.2019.004360.

- Li, Z., J. Diao, S. Lu, C. Tao, and J. Krauth. 2022. “Exploring a Sustainable Approach to Vernacular Dwelling Spaces with a Multiple Evidence Base Method: A Case Study of the Bai People’s Courtyard Houses in China.” Sustainability 14 (7): 3856. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073856.

- Liu, S. 2009. Chinese Folk Houses: Analysis of Traditional Residential Buildings. Jina, shanghai, China: Tongji University Press.

- Liu, Y. H. 1990. Rongcheng City Chronicl. Jinan, China: Qilu Press.

- Liu, C., and H. Tian. 2023. “The Regionality of Vernacular Residences on the TianJing Scale in China’s Traditional JiangNan Region.” Journal of Asian Architecture & Building Engineering just-accepted. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2023.2171732.

- Lu, Y. D. 2008. Chinese Residential Architecture. Guangzhou, China: South China University of Technology Press.

- Ma, D. 2018. Spatial reconstruction of traditional villages in Rongcheng City from the perspective of social space. Master thesis, Jinan: Shandong Jianzhu University.

- Ma, K. Y., T. Cui, and Y. Wu. 2021. “Type Investigation and Analysis of Seaweed House Doors on Dongzhu Island Village of Jiaodong Region.” Community 1:150–159.

- Sun, D. Z. 2004. China’s Vernacular Architecture Research. Beijing: China Construction Industry Press.

- Wang, H., X. Pu, R. Wang, Y. Zeng, and X. Qi. 2016. “A Study on Closed Halls in Traditional Dwellings in the Jiangnan Area, China.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 15 (2): 139–146. https://doi.org/10.3130/jaabe.15.139.

- Yang, J. 2011. “Selection and Application of Regional Residential Materials: The Example of Seagrass House in the Ecological Residential House of Jiaodong Peninsula.” Architectural Journal S2:152–155.

- Yuan, G. S. 2003. The Teaching of the World Settlement. Beijing: China Architecture and Building Press.

- Zhu, W. 2009. Spatial study of rural settlements in northern Zhejiang from the perspective of geography. Thesis. Hangzhou: Zhejiang University.