ABSTRACT

The cultural landscape is valuable for global ecological conservation, as it embodies human history and cultural heritage. Cultural landscapes, as treasures of human history and culture, have a place in the globalization process of ecological conservation. This paper uses Citespace based on the W.O.S. database for a bibliometric analysis to explore cultural landscape research. The history of the development of cultural landscapes is summarized and supported by theory and data. The study analyzes 2506 publicly available publications from various disciplines, including ecology, environmental sciences, multidisciplinary studies, social sciences, anthropology, and more. The research reveals that the discipline has a multi-layered nature, an uneven distribution of research institutions, and a single depth of analysis. The number of keywords in the literature has been increasing year-by-year, covering many hotspots and spanning a wide range of topics. To bridge the gap in the comprehensive study of cultural landscapes caused by psychological factors, we recommend starting with the historical context, cultural history, and human behavioral adaptations. Additionally, we suggest that the cultural ecosystem services provided by cultural landscapes should be explored in the context of human-driven ecotourism. The current phase of cultural ecosystem services aims to translate theory into practice by creating spiritual services and cultural psychology for humans in the post-popular era. Inter-institutional cooperation among scholars should be strengthened in research to respond to the trend of the globalization of ecological civilization-building. These efforts will provide suitable and feasible solutions for the globalization of ecological civilization and contribute to the development of the cultural landscape around cultural ecosystems.

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature review of the cultural landscape

The cultural landscape is a distinctive one that is created in tandem with the environment and is impacted by it (Antrop Citation2005). Understanding how people utilize and alter nature and the spatial disparities between human achievements and culture, etc. can be performed with research on the cultural landscape (Girard, Nocca, and Gravagnuolo Citation2019; Silva Citation2022). Even the natural historical context that helped to shape local culture can be observed.

In addition to the creation of more specific protection regulations by governments, countries have developed several innovations over time based on the continued exploration of the cultural landscape’s conceptual and physical levels (Gao and Wu Citation2017; Zhang et al. Citation2021). International theoretical research on the cultural landscape is at an advanced stage. Cultural landscape and landscape ecology research centers have been established internationally with European countries at the center, in addition to planning groups for the cultural landscape and ecological landscape formed at the center of Harvard University, the University of Pennsylvania, and Virginia State University in the United States (Naveh and Lieberman Citation2013; Poon Citation2019; Sylvester). Regarding conference policy, the United States held a White House Conference on World Heritage Preservation in 1968, being one of the first official voices on the fusion of cultural and natural heritage (Cameron and Rössler Citation2016).

Cultural landscapes are the product of human interactions and the environment (Jones Citation2003; Xie et al. Citation2022). They can be employed as tourist attractions, visual systems for human delight, witnesses to a location’s history and culture, or even to represent an entire region for academic research (Sather-Wagstaff Citation2016). On another level, cultural landscapes, like the Longmen Grottoes in China, are among the best examples of local history and frequently serve as witnesses to a particular historical era (Liu, Duan, and Deng Citation2012). Building a broader ecosystem of cultural services within such cultural landscapes is crucial. This cultural landscape can assist the city’s economy through tourism, service, and other sectors (Plieninger and Bieling Citation2012). It also serves as an essential landscape element within the city, impacting the overall traffic, city layout, and construction during the planning and design stages of the landscape (Bandarin and Van Oers Citation2012).

The study of cultural landscapes has gained recognition in recent years due to its contributions to our understanding of the regional variations in human culture and its ability to uncover the natural historical roots of local cultures. The world heritage landscape has been a common long-term focus of all countries regarding the current research content of the cultural landscape (Porter Citation2020). At the research level, cultural landscapes are frequently presented as an integrated problem involving globally prevalent problems like sustainable development, cultural identity, global climate change, cultural ecosystems, conservation methods and measures, social values and landscape management, and economic values. In addition to this, there is also a significant body of literature on the use of artificial intelligence and virtual reality technologies for evaluating cultural landscapes. These tools have proven effective in areas such as planning, design, stakeholder engagement, risk assessment, and cost-efficiency, ultimately leading to better outcomes for the preservation and enhancement of cultural landscapes (Demetrescu et al. Citation2020; Griffon et al. Citation2011; Lin et al. Citation2021). Even though business focuses on the study of cultural landscapes, other important topics of interest include geography, environmental factors, human history, politics, and economics (Fouberg, Murphy, and De Blij Citation2015; Graham, Ashworth, and Tunbridge Citation2016).

1.2. Justification for this research

Culture is born out of thought. Therefore, while examining the evolution of cultural landscapes, it is crucial to consider how human psychology has changed over time (Wilson, Groth, and Groth Citation2003). The consequences of the recent COVID-19 pandemic caused by the coronavirus should be discussed in light of the evolving characteristics of cultural landscapes (Carr Citation2020). It is clear that, in cities and villages that have suffered epidemics, human mobility in relation to buildings and sites is significantly reduced, as is the amount of active use, destruction, access to interiors, etc. that humans can carry out in relation to landscapes. COVID-19 not only affected this psychological factor but also hindered the conduct of field research, negatively affecting the study of cultural landscapes. The policies relating to cultural and landscape industries in various countries have been shaken and adjusted from an economic level since the epidemic spread throughout the world, which has largely resulted in the cultural ecosystem services of cultural landscapes in various places becoming “stagnant” and unattended (Anqi, Cenci, and Zhang Citation2022; Kaftan et al. Citation2023; Santos and Moreira Citation2021).

The important topic of the global vernacular constructed for heritage in the post-COVID-19 era was also addressed in the conference themes of the 2021 ICOMOS International Symposium on “Earthen and Woody Vernacular Heritage and Climate Change” (Labadi et al. Citation2021). Ecological globalization has become necessary due to the inescapable tendency for “globalization in general” (Fang, Liu, and Putra Citation2022). The tendency for globalization has exacerbated the ecological catastrophe, which has also impacted cultural landscapes (Ravis and Notkin Citation2020). Ecosystems that are part of the history of many historical and architectural cultures from antiquity are being slowly destroyed. Undeniably, a more appropriate ecological conservation approach is still required in cultural landscapes to reflect the cultural ecosystem areas of historical heritage, even though globalization can foster further cooperation and progress in environmental conservation and management among countries (LI and Y Citation2020).

It is essential to use novel methods of analysis and up-to-date approaches to comprehend how the cultural landscape has developed. Expanding theoretical research techniques and developing applied practice requires an understanding of research dynamics and the potential for developing cultural landscapes. This study uses W.O.S. as the main database and conducts a visual analysis of bibliometrics to identify current hotspot areas and trends in cultural landscape research in light of the growing global diversity and the rise of interdisciplinary communication and symbiosis in the field of cultural landscapes (Zhang et al. Citation2020). By exploring the viability of current concepts, the future directionality of the field of cultural landscapes is examined on a theoretical basis. Incorporating the development variables that contribute to the creation of cultural landscapes and completing the knowledge gaps regarding the ecosystem services provided by cultural landscapes.

Following the formal definition of cultural landscapes, this article systematically employs a bibliometric approach to analyze the global research literature from 2000 to 2023, identify the development trends and characteristics of cultural landscapes regarding the factors that led to their formation, and propose pertinent research perspectives. The primary content is divided into five sections: literature review, data sources and methods, research results, discussion, and conclusion. The article is separated into six parts overall, in addition to the introduction section at the beginning. The answers to a few notable issues are offered at the end.

2. Data sources and methods

2.1. Data sources

Scientific literature is now widely accessible, thanks to big data development (Bibri Citation2019). For example, it is found in newspapers, books, internet search engines, and media coverage of research platforms (Li et al. Citation2022). Therefore, this research searched the three primary databases in the Web of Science database, a global scientific platform which includes the Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIEXPANDED), the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), and the Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (CPCI-S) (Sarkar et al. Citation2022). We eliminated the terms “natural landscape” and “traditional culture village” after conducting numerous searches and using search engines for terms linked to “cultural landscape”. Considering that landscape is a countable noun, the terms “cultural landscape” and “cultural landscapes” were selected as the keywords for this experiment, and the search formula was set as T.S. = (*cultural landscape OR *cultural landscapes). The starting date was set as 2000, which is when The European Landscape Convention was enacted and the importance of cultural landscapes was first brought to the public’s attention, and the ending date was set as 2023 (Marine Citation2022). The search returned 2506 results for the “English” language option, all of which were exported as plain text files and met the export requirements of 500 complete records and cited references in a single file. A total of 2506 useful papers were acquired in plain text format as the study’s data after duplicates had been eliminated. Sorting and filtering were performed using Citespace software.

2.2. Research methodology

Citespace is a practical knowledge-mapping tool based on multivariate dynamic citation analysis and pathfinding network algorithms that are frequently employed for the measurement and analysis of data from the scientific research literature (Wu et al. Citation2022). Citespace software may synthesize the hot areas, trends, and major research findings in the cultural landscape field based on the map after visualizing the knowledge map (Zhang et al. Citation2022). It is hoped that it will offer the research needed to strengthen the foundation of knowledge, present case studies, and allow advancement in the appropriate direction. Citespace can be used for visual analysis, but there are certain limitations: it does not yet reflect an all-encompassing and comprehensive research system (Xu et al. Citation2022). Therefore, the method of literature analysis was added to the quantitative study. We offset the one-sidedness of the scientific and technical papers by adding elements to our study such as laws and regulations and other important literature related to the field of cultural landscapes. The advantage of this software is that it is based on bibliometric and content analysis, so it can systematically synthesize pertinent research results to provide readers with the research outcomes and future directions of an academic area (Palmatier, Houston, and Hulland Citation2018). This makes it a more scientific, potent, and effective tool for qualitative research (Moral-Muñoz et al. Citation2019). The experiment included seven dimensions, author, journal, country, institution, keyword, reference, and category, and had a time slice of 1 year and a g-index of k = 25. The definitions of centrality, clustering module value, and average profile value need to be noted separately when using different graphs for evaluation work. Centrality can be obtained from the purple borders around the nodes and the width of the borders is proportional to their scholarly value. The hotness levels of the study topic, organization, journal, and other research levels are greater if the mediated centrally hits 0.1. The clustering module value is often referred to as the Q value, and both it and the mean profile value (S value) are important metrics for evaluating clusters. When Q > 0.3, the study can consider the cluster to be fairly well-structured. When the S value is greater than 0.5, the grouping can be judged as convincing. The term emergent graph is used to show words that unexpectedly appear or vary in frequency over time in study-related disciplines, allowing researchers to explore and gauge future issues and potential research directions related to the cultural landscape.

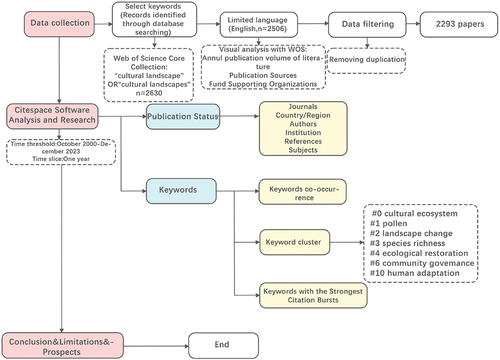

2.3. Study design

The initial step in the research design process was to limit the keywords to search for and obtain n = 2506 available documents. The full record and cited references were exported in plain text format, which is available in Citespace software, and then, we classified and de-duplicated the data. The time slice and time frame of the software were changed to October 2000–December 2023 and k = 25 was set for the g-index option before using Citespace. A visual analysis of the status of publications by journal, country/region, author, institution, reference, and category was conducted using the software after it had been set up as described above. Additionally, keyword co-occurrence mapping, keyword clustering, and keyword emergence mapping were obtained. From there, the map was defined by the values of its centrality, clustered modular values, and average profile values, and the trends in the development of the cultural landscape were determined by capturing the different keywords in each period and the relationship between the clusters of each keyword. This research was integrated into a comprehensive study and dynamic analysis based on the mapping content, outlining the shifting trends in the development of the cultural landscape and research hotspots. In , more information about the research design is displayed.

3. Results

3.1. Documents related to the cultural landscape

A national policy system and historical documents that are current with the times have been formed in the practice area of cultural landscapes over several years of collisions and idea modifications (Stenseke Citation2009). Their meanings reflect the shifts in human thought over time, the development of life’s tools, and sometimes, the regional characteristics of human civilization. These documents have contributed to the growth of the cultural landscape protection system at the policy level, and the gradual timing of their introduction confirms the gradual improvement of all aspects of the cultural landscape field. Exploring the future direction and changing trends of the cultural landscape is essential to analyze the relevant historical documents (shown in ) produced over the past ten years (Blake Citation2000; Forsyth Citation2014; Seardo Citation2015; Silberman Citation2006).

Table 1. Recent historical documents related to cultural landscapes.

3.2. General overview of research progress

3.2.1. Volume of publications (output time distribution)

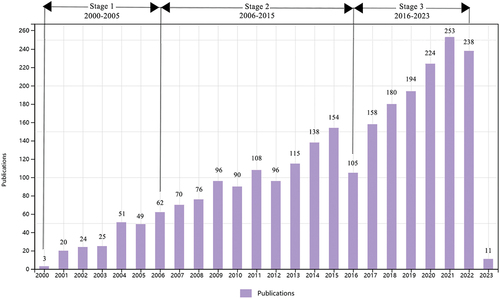

It is possible to use the yearly number of publications to examine the broad trends in the growth of the field of cultural landscape studies (Cohen Citation2004). The size of the annual number of publications is a significant indicator of the development of the field (de Almeida, Guimarães, and de Almeida Citation2013). It is straightforward to tell when the number of publications began to increase and peak based on the varied values for the yearly number of publications in the graph. According to statistics, the research field peaked in 2021. It also showed a low point in 2016.

The year-to-year trend in the number of publications shown in clearly shows that the number of publications relevant to cultural landscapes is increasing. The number of publications connected to cultural landscapes was determined using the W.O.S. core database’s visual analysis tool, with the original data acquired as the starting point. The development history may be separated into three distinct stages.

Figure 2. Distribution of annual publication outputs in the cultural landscape field from 2000 to 2023. ©authors.

Early stage (2000–2005): This is the period of cultural emergence. The European Landscape Treaty was published in 2000, new research results in the field of cultural landscapes gradually emerged, and legislative documents and laws for the protection of ecosystems related to cultural landscapes were formed.

Stable progress period (2006–2015): This was a prosperous time for cultural landscapes. The theoretical foundation was completed in 2005. In 2005, the theoretical framework was finished. The number of publications on cultural landscapes began to skyrocket. The number of publications on cultural landscapes underwent a significant change in 2016 before recovering and sharply increasing in 2017. This indicates that cultural landscape research has historically been performed from a single point of view, which led to a decline in the number of cultural landscape research findings in 2016. As a result, it is important to make a timely and appropriate change in perspective. This is also a means of urging scholars to change their perspective over time.

Rapid development period (2016–2023): This phase is the culmination of a period of cultural landscapes with a long-term trend of stabilization to positive values. The publishing of the Rural Landscape Heritage Guidelines paper raised global awareness of the importance of cultural landscape ecology and environmental conservation. The general growth in publications on cultural landscapes has improved the study field, implying that it may thrive with diverse potential future orientations.

The overall situation whereby the number of articles published on cultural landscape is increasing year-by-year, especially from 2016–2023, is advantageous for its research field itself, which means that this academic field has many possibilities for future development, and many scholars are contributing to its development.

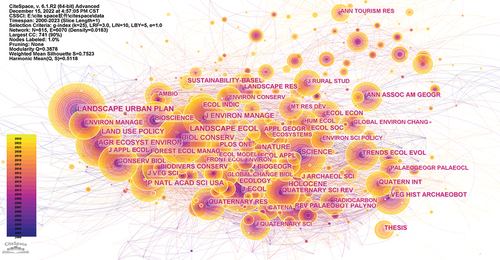

3.2.2. Distribution of published journals

The distribution of publications in journals that deal with cultural landscapes may be determined by the topic area, impact factor, research orientation, and other research data using the computational analytic tool Citespace (Zhuang et al. Citation2022). The distribution of significant publications is a vital sign of how the field of cultural landscapes is progressing (Zhu, Koutra, and Zhang Citation2022). The visual analysis graph may be viewed in three directions to determine the ranking of journals: the number of nodes, the connection value, and the density (Hong et al. Citation2019). This is executed in order to produce a map of related journals. shows a journal distribution with 815 nodes, a connection value of 6070, and a density of 0.0183. displays the main journals that publish articles. The top five journals with thousands of applications are Landscape Urban Planning, Landscape Ecology, Science, Biological Conservation, and Land Use Policy. The top five most academically influential journals according to nodal centroid ranking are Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment (0.07), Forest Ecology and Management (0.06), Landscape Urban Planning (0.04), Holocene (0.04), and Conservation Biology (0.04). The top ten journals focus on environmental science, ecology, geography, geophysics, and green sustainable science and technology. These topics are the field’s main research directions, and more details are shown in the table.

Figure 3. Knowledge map of co-journals of papers published on the cultural landscape from 2000 to 2023. ©authors.

Table 2. Major research journals in the field of cultural landscapes from 2000 to 2023.

The results shown in the visualization analysis graph indicate that cultural landscapes can significantly influence environmental landscape planning and indirectly influence ecology, geography, and sustainability.

Through our research, we learned from the journals that have published papers in the field of cultural landscapes over different periods of time about the disciplines that have been significantly impacted, which is broadly instructive in terms of the future applications of cultural landscapes.

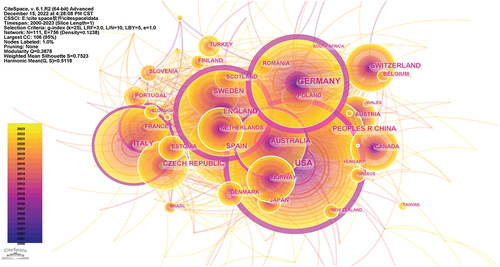

3.2.3. Distribution of cooperation in issuing regions, author cooperation, and research institution cooperation

A cross-section of cooperation among the key research countries in this field can be obtained by analyzing the regional distribution of cooperation in the cultural landscape published while looking at the geographical distribution of published findings (Yao et al. Citation2023). According to , starting in 2000 and continuing until 2023, American institutions placed first in cultural landscapes with 360 published articles, a centrality of 0.35, and the most collaborations and cross-references. With 250 articles, the German institution came in second, followed by the UK institution (213), the Italian institution (203), and the Chinese institution (197). provides more information on the regions of publishing. Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, and China have carried out many studies for this purpose, as indicated in . However, according to the centrality results, there is still a considerable gap to the United States, which has carried out the most investigations.

Figure 4. Knowledge map of cooperative countries in the research on the cultural landscape during 2000–2023. ©authors.

Table 3. Major countries publishing articles in the field of cultural landscapes.

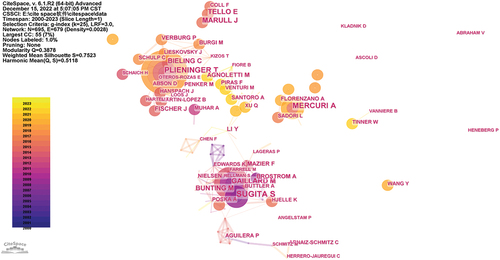

The collaborative distribution map of published authors provides a better understanding of the relationships between key players in a research field and the collaborative cross-referencing among scholars (Kang et al. Citation2022).

This map is shown in and contains 695 nodes (N = 695), 679 connections (E = 679), and a density of 0.0028 (Density = 0.0028). shows the number of publications by the top authors in cultural landscape research. Sugita S. (20), Plieninger T. (15), Mercuri A. (15), Gaillard M. (12), Marull J. (11), and Tello E. (11) are six influential scholars in the field of resilient city research. Based on their research directions, it can be seen that the authors’ collaborative network is mainly focused on the environmental sciences and ecology, geography and sustainable development, and biodiversity and conservation research directions. In terms of publications, there is little difference between scholars.

Figure 5. Knowledge map of co-authors of papers published on cultural landscapes from 2000 to 2023. ©authors.

Table 4. Top 10 productive authors in the field of cultural landscapes from 2000 to 2023.

According to the knowledge mapping shown in , author collaborations in cultural landscapes are more dispersed, showing two clusters with a broad punctuated distribution. This indicates a persistent lack of scientific collaboration, and a practical response to the building of collaborative bridges is still needed to address this issue. The state of researcher collaboration forms three matrices at the global level in a dotted pattern, with two of the biggest matrices containing people with different nationalities and from different institutional affiliations. The level of interpersonal cooperation is deeper. It is possible to develop different research perspectives on cultural landscapes from the cooperation between personnel and to construct cultural ecosystem services from an ecological perspective. The construction of cultural ecosystem services from an ecological perspective has become one of the response trends for the future sustainable development of cultural landscapes.

In the context of globalization, cooperation between authors and institutions has become an indispensable step in the process of research in particular academic fields. The advantage is not only the expansion of academic horizons but also the ability to take advantage of the different cultural landscapes of each region to maximize the ecological benefits.

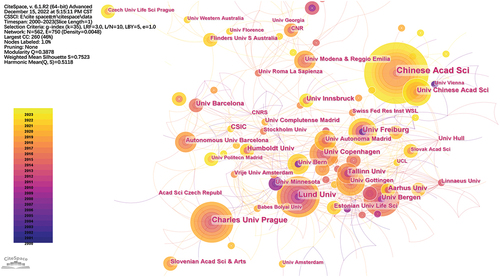

Moreover, the distribution of collaboration among research institutions reflects the level of scholarly support and recognition offered by institutions in the field, from which this research can analyze the influence and scholarly insights of the field and, as a result, encourage the strengthening of collaboration among institutions and the advancement of the research field (Heilig and Voß Citation2014). For detailed information please read . A rather dispersed distribution characterizes the distribution of nodes throughout the map. As can be observed, The Chinese Academy of Sciences is ranked first among the top 10 publishing institutions for the 2000–2023 period (45), followed by Lund University (33) and Charles University (31).

Figure 6. Knowledge map of cooperative institutions in research on cultural landscapes during 2000–2023. ©Authors.

‘s centrality display shows that each research institution has uneven numbers of publications and centrality values and that the research institutions with the greatest numbers of published papers do not necessarily have the most influence. We can see that China, which currently has the largest number of World Heritage sites worldwide, has been equally successful in publishing articles and is the larger representative country in the network distribution map. The nodes of the institutional contribution distribution map form a more complex matrix that can show how countries have increased their investment in cultural landscapes over time. Greater consideration has been given to how cultural landscapes influence the planning of environmental landscapes and the gradual development of new cultural ecosystem services from an ecological perspective. Stronger collaboration between research organizations, universities, and businesses is needed in the globalized cultural landscape study field, as well as a greater focus on the effect and quality of the articles produced.

Table 5. The top 10 institutions in the field of cultural landscapes from 2000 to 2023.

The regional distribution of publications, the institutional distribution, and collaborative author research in the field of cultural landscapes shows us the excellent academic insight and research potential of the field. The richness of the findings opens up new possibilities for the future development of cultural landscapes and, on the other hand, guides the direction for investment in cultural landscapes.

3.3. Research areas

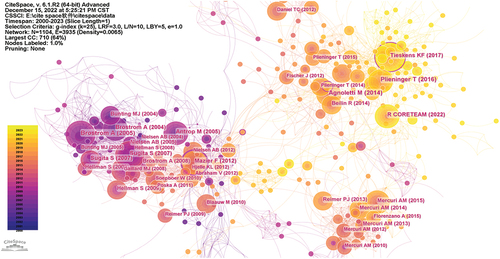

3.3.1. Highly cited chapters

The discipline and primary study topics of the most cited publications in the field of cultural landscapes from 2000 to 2023 May be determined by evaluating the data from highly referenced articles. and were created using Citespace software to assess the most cited papers on the cultural landscape. The analysis shows that the most cited article between 2000 and 2023 was an article published in 2005 by the scholar Brostrom A “Estimating the spatial scale of pollen dispersal in the cultural landscape of southern Sweden” (116 citations, 3.092 impact factor); the second most cited article was published in 2014 by the scholar Agnoletti M “Rural landscape, nature conservation, and culture: some notes on research trends and management approaches from a (southern) European perspective” (cited 201 times, 8.119 impact factor); and the third-ranked article was published by Plieninger T in 2016, “The driving forces of landscape change in Europe: A systematic review of the evidence” (cited 283 times, 6.189 impact factor). Environmental sciences and ecology, geography, physical geography, public administration, urban studies, and geology are the primary research fields contained in these periodicals. This research discovered some correlations between the highly cited literature presented in after further understanding the content of the cited literature in the field, which can be used to explore the disciplinary range of the cultural landscape research field. The nodes of the highly cited literature are distributed in a tree-like pattern, forming three clusters spaced apart.

Figure 7. Knowledge map of cited references in papers published on cultural landscapes from 2000 to 2023, ©authors.

Table 6. Highly cited references in the field of cultural landscapes.

The study’s findings show that research on cultural landscapes is primarily focused on the level of ecology natural theory, the planning and design of buildings, and park ecological management evaluation, as shown by the knowledge structure framework of the referenced articles. Innovative techniques for the building of cultural landscape indices and cultural ecological governance models still need to be highlighted.

This demonstrates the referenced publications’ better value and influence on subsequent research. As a result of the size of the cultural landscape research field, scholars are advised to consider interdisciplinary collaboration from the standpoint of sustainable development in future research. Identifying the field’s hottest disciplines and research trends through frequently cited references is critical.

Through the study, it was shown that the most cited articles in the field of cultural landscapes were produced between 2005 and 2016 and still serve as excellent guides today. The highly cited literature illuminates the subject direction and popular application categories for cultural landscapes.

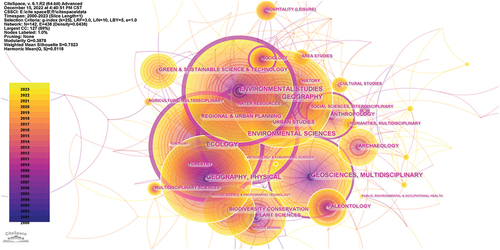

3.3.2. Research areas

A field’s disciplinary range and development trajectory can be explored by studying its disciplinary categories (Neumann, Parry, and Becher Citation2002). Additionally, it is feasible to determine the significance and applicability of the disciplines within it, highlighting the linkages between disciplines and pointing to potential study areas (Zuo et al. Citation2021). Regarding the degree of influence, the most influential category is environmental studies (552), with a centrality of 0.28, followed by ecology (403), with a centrality of 0.22. These disciplines are the disciplinary categories to which the most popular research hotspots in cultural landscapes currently belong. Environmental science (474) has a centrality of 0.22, while education (403) has a centrality of 0.22. These disciplines are intertwined with the field of cultural landscapes. At the same time, ecology (403) and education and educational research (centrality 0.2) are in the third group alongside earth sciences, multidisciplinary (290) (centrality 0.19), and sociology (61) (centrality 0.16).

Each node in the analysis choices appears with a varied frequency due to the varying sizes of the nodes. The line connecting the nodes denotes connectedness: the darker the line, the stronger the academic relationship between the two disciplines. The purple border outside the node reflects centrality: the broader the border, the higher the node’s centrality and academic significance. The disciplinary categories in the cultural landscape study are more closely related, as shown in . The disciplines influencing the field the most are environmental studies, environmental sciences, ecology, multidisciplinary geosciences, anthropology, and social sciences. lists the top 10 disciplinary groups in terms of academic influence based on their centrality.

Table 7. List of the most influential categories.

The time zone map enables us to analyze the different years of disciplinary changes in the field between 2000 and 2023 by categorizing the disciplinary clusters with distinct colors and graphically summarizing the changes in the pertinent disciplinary hotspots.

As shown by the red 0 clusters of environmental sciences, ecology, and plant sciences in , the development phase of one category of disciplinary clusters, dominated by environmental sciences and ecology and urban studies and biodiversity conservation, occurred between 2000 and 2010. This demonstrates the fundamental relationship between the disciplines above the field and the dominant cultural landscape direction. For this reason, it is even more crucial that we consider the design of the landscape environment, promote the development of human cultural heritage, and invest more effort in its sustainable development and in the creation of cultural ecological service systems. This construction strategy can enhance regeneration and inclusivity within the cultural landscape and act as a roadmap for further environmental planning. Due to the diversity of specialities, there are numerous opportunities for future cultural landscape development.

During the 2000–2023 period, eight disciplinary clusters emerged in the field of cultural landscapes, with intertwined and complex commonalities and connections between them. The latest disciplinary trend is to include the natural sciences, artificial intelligence technology, human history, and more. Analyzing the range of disciplines in cultural landscapes points to the latest potential directions for our research.

3.4. Research hotspots and research strategies

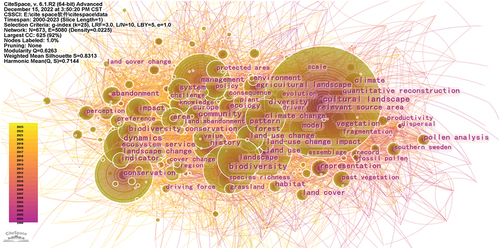

3.4.1. Keyword co-occurrence grid

An article’s primary subject matter, style, and essential concepts can all be reflected in its keywords (Cheng et al. Citation2020): the more links, the more frequently two keywords occur together; the larger the nodes in the mapping, the deeper the degree of linkage and association between them; the thicker the connections, the stronger the relationship between them (Li et al. Citation2020).

This research can effectively display the hottest trends and knowledge structure in cultural landscape research using Citespace software. It can determine terms’ co-occurrence frequency and centrality and create a keyword co-occurrence map (Rawat and Sood Citation2021). displays the word frequency ranking statistics. Cultural landscape (799) was the most frequently used term, followed by management (249), conservation (218), biodiversity (188), and landscape (164) making up the top five rankings. These terms, central to the subject of cultural landscape study, are regularly used in the introductions of articles. They may even be used several times in one article.

Table 8. Top 10 high-frequency keywords from papers on cultural landscape research relative to the period in the text.

Table 9. The top six high-frequency keywords in papers published in the field of cultural landscapes every five years during 2000–2023.

Based on the size of the nodes in , we can determine the direction of focus in the area of cultural landscapes. From this, it is easy to generalize that the current situation is heavily focused on cultural landscapes in terms of management and conservation and other related studies. This study argues that the construction of sustainable cultural ecosystem services can be adopted in cultural heritage. This will not only make it easier to plan environmental landscapes while keeping the value of ecological preservation and the psychological effects of environmental factors on people in mind but will also enable us to examine how cultural landscapes have changed over time from new perspectives of geography and ecology as a guide for future re-planning. On the level of cultural landscape conservation, numerous keywords imply that the public’s attention on cultural landscape is gradually increasing, and the human perception of landscape conservation is advancing over time, providing a strong backing for the ecological globalization process.

Figure 10. Keyword co-occurrence map of keywords from the papers on cultural landscapes produced during 2000–2023. ©Authors.

In addition, the construction of cultural ecosystem services will also bring considerable tertiary industry income to the cultural landscape, which is mutually beneficial as it also protects the ecological environment of the landscape park, obtaining a win – win situation.

During the 2000–2010 period, the most frequent keywords, cultural landscape, management, conservation, biodiversity, and ecosystem service, appeared. There were different applied relationships between them related to the field of cultural landscape, and they show a trend from disciplinary theory to applied practice.

3.4.2. Keyword co-occurrence time partitioning

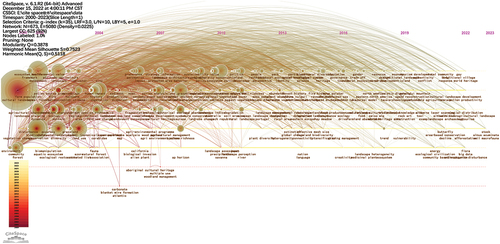

The evolution of research hotspots over time can be seen through keyword time zone mapping (Cheng et al. Citation2018). The number of keyword connections in the graph indicates the frequency of the keyword, and the arc implies the period. The size of the graph also reflects the level of research intensity (Geng, Zhu, and Maimaituerxun Citation2022). Using Citespace, a keyword co-occurrence time map and time zone map can be produced. This study can indeed be used to understand cutting-edge topics in the field of cultural landscape, the evolution and emergence of keywords in different eras, and identify deep disciplines and track the constantly changing popular entry points to precisely determine the overall trends and specific directions of cultural landscape development through the changes and trends in the images (Ming Citation2021). It provides a powerful theoretical vane for research in the field of cultural landscapes. Identifying these keywords can aid in the proposal of research hotspots and can indicate the frontier and trends of studies on cultural landscapes. Keywords with high emergence are words with a high-frequency change rate over a certain period. The study first analyzed the keywords associated with research hotspots in cultural landscapes using keyword co-occurrence. Based on this analysis, the temporal mapping function in Citespace software was then used to transform the data, obtaining a timeline map of cultural landscape research from 2000 to 2023 with a temporal partition map (as shown in ) to expose its specific development trend. There were notable variances in the study content, focus, and hot themes between various eras. In conclusion, three phases may be stated

The first phase of exploration (2000–2003): The European Landscape Convention was released on October 20, 2000, and experts in the area started to acknowledge the significance of cultural landscapes.

The period of steady development (2004–2015): The study and practice processes adopted a more holistic perspective of the landscape at this time while also growing increasingly aware of its distinctiveness and regional traits, and there was also continued development of the understanding of the landscape’s primary meaning and significance. The primary scientific topics at this time were the preservation of biodiversity, ecosystem services, previous vegetation, and human-induced environmental change.

The years of advancement (2016 to the present): Cultural landscapes have been separated into several sections, as natural and cultural landscapes coexist. A cultural landscape has diverse meanings and functions depending on the era it is observed in. The study focused on agroforestry systems, community-based ecotourism, and agricultural abandonment at the building level. In landscape conservation, the focus could be on archaeological sites and world heritage.

Figure 11. A timeline view of co-occurring keywords in papers on cultural landscapes produced during 2000–2023. ©authors.

Figure 12. Annual variations of co-occurring keywords in papers on cultural landscapes produced during 2000–2023. ©authors.

Keywords such as cultural landscapes, conservation, and diversity appeared in the research field between 2000 and 2003, indicating a trend of exploration and enlightenment, and between 2004 and 2015, the hot topic of ecosystem services appeared among the main topics, with a derivative relationship with cultural landscapes and a new trend of transformation in the system of cultural landscape management. Furthermore, the popularity of agroforestry ecosystems and community-based ecotourism demonstrates that ecological construction became an essential category for humans in the context of globalization between 2016 and 2023, during which time cultural landscapes underwent further accelerated upgrading.

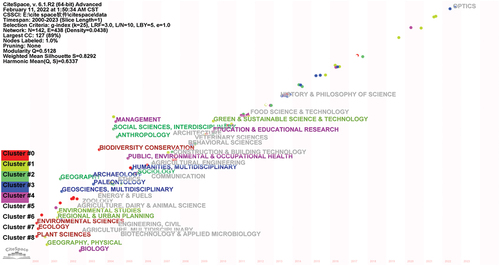

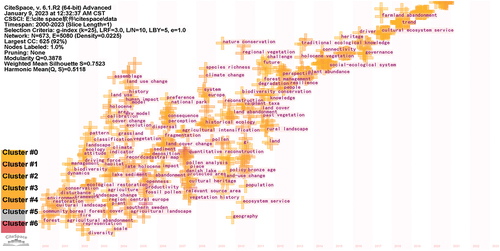

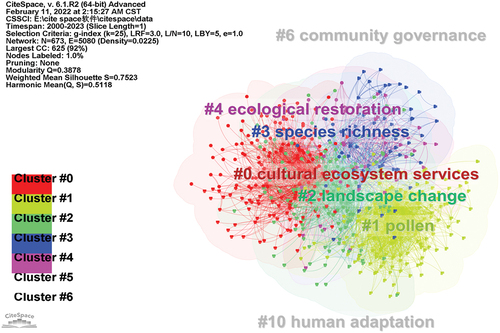

3.4.3. Keyword clustering analysis

Through an algorithm that assigns each term a value, Citespace software groups closely linked keywords together (Zeng and Chini Citation2017). The term inside a cluster with the highest value is selected as the representative term and given a label. Three methods – LSI, L.L.R., and MI – are used to compute the clusters, and this research selected L.L.R. as the method that produces the best outcomes for each cluster. The cluster module value (Q value) and the average profile value serve as the primary metrics for assessing clusters (S value). A Q value that is near 1 indicates closer linkages and relationships within the clusters. Q > 0.3 is often taken to indicate a considerable cluster structure. The mean profile (S value) value should fall between −1 and 1. The grouping is rational when S is greater than 0.5, and the clustering is plausible when S is greater than 0.7. A number closer to 1 suggests that the articles inside a cluster are more strongly consistent or comparable in terms of content. As a result, 41 knowledge clusters were discovered. The cluster sizes were ranked starting with #0, and the largest cluster was given a value of 0. The large variety of references covered by the referenced subjects is represented by the seven viable clusters found after filtering, as shown in and . shows that the module value was 0.3878 and the average profile value was 0.7523, which leads us to believe that the knowledge graph’s cluster analysis was performed well and that the results of the keyword clustering in the domain of the cultural landscape are structurally significant and convincing.

Figure 13. Co-citation network and clusters of papers on cultural landscapes produced during 2000–2023. ©authors.

Table 10. List of cited clusters and several contributing records.

Regarding the specifics of the keyword clusters, from , the first ranked cluster is cultural ecological services (#0). This knowledge cluster contains 187 articles that were mostly published in 2014 with a silhouette value of 0.688. It contains studies on ecosystem services, pollen analysis, and land use. The second largest cluster is pollen (#1), which contains studies on human impact, palynology, pollen, and Holocene analysis. Most articles were published in 2009, containing 165 with a silhouette value of 0.795. The third largest cluster is landscape change (#2), which contains 146 articles with a silhouette value of 0.7, most of which were published in 2011. It contains studies on landscape metrics, land use change, and pollen analysis. The fourth largest cluster, species richness (#3), contains pollen, biodiversity, disturbance, and land use studies. The fifth major cluster (#4) contains 52 articles that were mostly published in 2008, with a silhouette of 0.814. This knowledge cluster contains studies on ecological restoration, earthworms, the Himalayas, landscape perception, and environmental gradients. The sixth largest cluster (#6) contains four articles with a silhouette of 0.991 and contains studies on community governance, multiple use, aboriginal cultural heritage, environmental management, and Tasmania. In addition, the seventh largest cluster (#10) contains studies on human adaptation, Norse, landman, archaeology, and paleoecology. This knowledge cluster has three articles with a silhouette value of 0.996.

This study can provide high-impact word labels with a prominent position thanks to its strong, trustworthy cluster mapping analysis (Chain et al. Citation2019). It is clear from the examination of pertinent papers included in this study that the contributions of the scientific disciplines of environmental ecology, plant impact, and paleoecology in the early development of the subject of cultural landscape theory cannot be disregarded. In today’s globalized society, where environmental conservation is prioritized, cultural landscapes must meet equally high standards for their total ecological construction. The development and building of the biological environment inside the cultural landscape as a whole park have been proven to be influenced by active human activity, which can also affect the mechanism and process of change in the formation of cultural landscapes.

Therefore, the perspective can be changed to explore whether the role of environmental psychology can be applied to the building of interactive ecosystem services through sustainable development, although this is a problem that needs empirical evidence.

Overall, six keyword clusters may be easily detected between the years 2000 and 2023. Among these, there are five clusters, #1, #3, #4, #6, and #10, from 2005 to 2010, that have some association and are linked to one another. Two clusters, #0 and #2 May 2001be found in the 2010–2015 period, and they are similar in terms of keywords with divergent correlations. The clustered keywords’ evolution reveals a consistent pattern of increased expansion and improvement.

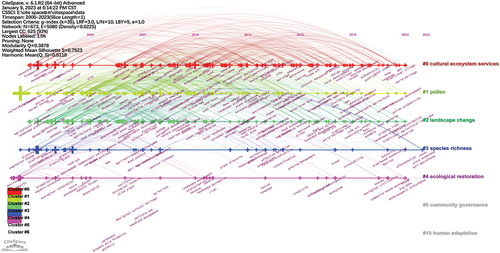

3.4.4. Research clustering timeline

The analysis of the clustering timeline may pinpoint important texts that have shaped our understanding of the cultural environment (Mommaas Citation2004). It also accurately depicts the beginning and growth of each cluster and the existing tendencies for the future. demonstrates how keyword clusters are created throughout the timeline mapping process using the L.L.R. algorithm and visual analysis.

According to the research, ecological preservation and production processes have received the majority of the attention in recent research on cultural landscapes. When restoring ancient cultural landscapes, it is important to consider the regional ecosystems, specific forms, historical plant roles, perceived landscape changes over time, and patterns of ecosystem change. It is also important to address issues with ecological restoration and the existing architectural and spatial forms of variability. The enhancement of land pattern usage and the design and study of the cultural landscape’s natural ecosystem are priorities for future cultural landscape planning, construction, and restoration.

Additionally, when mastering the design of a cultural landscape, consideration should be given to the development of an ecological construction process. The entrance points for investigation and focused research in the field of cultural landscapes include the general ecosystem environment composition of the cultural landscape, the land use pattern, integrated pattern usage evolution, and ecological infrastructure development.

It is clear that most clusters in the field of cultural landscapes formed in about 2000, and the most representative terms correspond to the domains of the historical function of the paleobotanical and ecological elements of the cultural landscape. Based on the link, we may conclude that, in the last two decades, the focus of cultural landscape research has gradually switched from ancient plants to the service dynamics and ecological benefits of building itself.

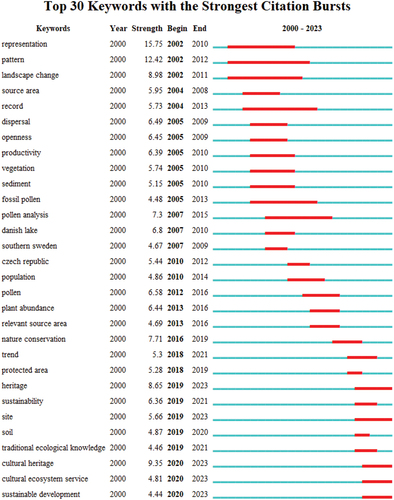

3.4.5. Research trends

By analyzing the high-frequency changes in each keyword over a certain period, one can delve further into the main contents of key literature in the field of cultural landscapes (Arora et al. Citation2013) and collect the terms that received the greatest attention from scholars at the time, demonstrating shifts and research patterns in popular study topics. The research emphasis and hot regions of cultural landscapes fluctuate significantly at various phases, as illustrated in , according to the various stages. The study of representation, the source region, landscape change, dispersion, pattern, record, vegetation, deposits, and fossil pollen were the key areas of concentration in cultural landscape studies before 2005.

In contrast, pollen analysis studies gained more attention between 2007 and 2015. Since 2007, the study of interior landscapes in the Czech Republic, southern Sweden, and the Danish Lake District has been the focus of cultural landscape research. This also provides a unique perspective for this study: a new cultural ecosystem can be constructed starting from local areas and unique cultural landscape parks.

The reality is that the research focus on cultural landscape areas has gradually shifted to the overall ecological and social effects. The diversity of the research areas and the frequency of trending themes are growing. In 2019, there was a rise in interest on several themes, including cultural heritage, sustainable development, soils, sites, traditional ecological knowledge, and chemical ecosystem services. This indicates that more attention is beginning to be paid to how globalization affects the conservation of environmental ecology and the ecological conservation role of cultural heritage, as well as offering more possibilities for the future development of cultural landscapes.

Subsequently, high-frequency changes in cultural landscape keywords can be classified into three stages. For starters, the most popular terms from 2000 to 2005 were pollen fossil research, landscape change, and pattern distribution, among others, and people were particularly interested in the ecological production and transformation of ancient cultural landscapes. From 2007 to 2015, the study of a specific region’s internal landscape rose to the top of the term frequency list, with the field of cultural landscapes showing a small to significant trend. Furthermore, from 2015 to 2023, the high-frequency keywords appearing in the field included keywords related to ecologically sustainable development and overall social benefits, and overall cultural landscape research showed a trend of being more theoretically enriched and encompassing a wide range of topics.

4. Discussion

The main contribution of our study is the provision of trends in ecosystem modification research in the field of cultural landscape studies. This research examined the disciplinary categories and highly cited publications while investigating the topic of cultural landscape study. This makes it possible for us to understand the tendencies of important study areas and changes in the industry as cultural landscapes grow. Our research discovered that the study of cultural landscapes has given rise to numerous new terminologies, such as pattern, landscape change, and pollen analysis. Cultural ecosystem services, sustainable development, and cultural heritage have all become popular recently. These concepts led us to conclude that the historical setting, cultural evolution, and adaptation of human behavior as the starting points can more effectively fill the void left by psychological variables in cultural landscape building (according to ). These results also motivate us to investigate the cultural ecosystem services provided by cultural landscapes in human-driven ecotourism operations.

In terms of study content, this research observed three broad tendencies in the growth of cultural landscape research. First, there has been an increasing focus on the esthetic experience and intangible advantages of cultural ecosystems through spiritual fulfilment. The protection of cultural heritage, sustainability, and cultural ecosystem services are the three main areas of integration that are essential from a global perspective. Second, the concept incorporates the analysis of the issue, and the management and protection of cultural landscapes has become more complex. Following years of study and application, nations now emphasize the creation of cultural ecosystem services while also emphasizing the value of preserving and utilizing the natural elements of cultural landscapes. Such methods can safeguard societal interests while considering the financial advantages of tourism. Third, in addition to analyzing changes in natural patterns and the impact of paleontology, studying the mechanisms behind cultural landscape formation and development has also drawn more attention to environmental changes produced by human activity.

Our research indicates that studies on cultural landscapes share the trait of favoring the formation mechanism and ecological protection. This was discovered through the mechanism study. However, how can coordinated ecological conservation play a proper role in pushing the use value of cultural landscapes under the aegis of sustainable development? How can we encourage people to derive esthetic and spiritual benefits from the ecosystem fairly? Few examples of creating a system of cultural ecosystem services in cultural landscapes exist, and most of them are still in the realm of theoretical research. The construction, implementation, operation, and maintenance of cultural ecosystem services in cultural landscapes require lengthy periods of development and refinement before they can be considered a system. The sources of the research literature used in this paper are all from the W.O.S. core database, and we did not consider literature from other databases, such as CNKI, K.C.I., etc. We chose the three main databases of the Web of Science platform because this approach is the dominant choice in the research field today and is the default choice for screening data in literature reviews. Therefore, the data may be lacking richness and completeness. During the literature search and screening process, our research defined selected literature written in native English, but there may be literature in other languages produced in the field of cultural landscapes, so the study is still limited.

Moreover, the research results are time-sensitive, and the academic results contained in the database are constantly changing, so there is a risk that the data are not accurate enough. The research terms cultural landscape and cultural landscapes were chosen as keywords to find the main content in the literature. This operation was performed to minimize ambiguity and perform accurate screening while avoiding the inclusion of erroneous data. By limiting the search to keywords, we obtained enough data to support the experiment. However, many of the indexed articles have themes of world heritage, historical heritage, and rural cultural landscapes. Therefore, there may be some uncertainty in the scope of the study.

In our research, we placed greater emphasis on how cultural landscapes are interpreted and developed. The cultural ecosystem services that cultural landscapes can offer have grown in importance as globalization has intensified. In addition to the more developed geographic, ecological, and natural studies, the historical and human aspects of the cultural landscape environments, human adaptation, and behavioral impacts can also be emphasized when studying the mechanisms by which cultural landscapes form. In order to build a complete practical system sooner, this research can assess the core spiritual needs of people in cultural ecosystem services, coordinate ecological conservation under the demands of sustainable development, and coordinate ecological conservation.

5. Conclusions

The Citespace bibliometric tool was used to assess this work, and the W.O.S. core database was used as the primary research data source. The time frame was from 2000 to 2023, and the keywords included cultural landscape and cultural landscapes. The research examined the human influences on the creation of cultural landscapes and the current state of cultural ecosystem services in cultural landscapes from the viewpoint of cultural properties.

The study’s findings demonstrate that the overall study of cultural landscapes is progressing systematically, and the number of publications in this field is rising steadily. The number of publications is growing annually, the included journals cover a wide range of disciplines, and the cooperation between the publishing areas is good. However, there is still a need for further in-depth communication. Scholars and research institutions are inextricably linked, and as globalization has progressed, tight collaboration across research institutions has emerged as a significant trend. There is undeniably a lack of connections among research organizations published in cultural landscapes, and there is always an opportunity for improvement. By examining the study domains, the research discovered that the cited papers in the cultural landscape are complicated and span various disciplines. With 673 keywords, the cultural landscape study is even more comprehensive regarding the keyword analysis. The development period can be roughly divided into three phases, and the cultural landscape is becoming increasingly important. As part of human history and cultural assets, cultural landscapes are in the process of globalizing ecological conservation at the level of development hotspots and cannot be disregarded. For instance, sustainable development includes the preservation of cultural assets and the creation of cultural ecosystem services and cultural landscape ecosystems. The article discusses the development of cultural ecosystem services provided by cultural landscapes and the influence of human adaptation on the formation of cultural landscapes as the primary issue. It discusses the relationships among ecological conservation, sustainable development, the creation of non-material benefits, human influence, and the formation of cultural landscapes, respectively.

Based on the above findings, it is possible to investigate how human psychological factors affect how cultural landscapes are formed. This could lead to new ideas for developing cultural ecosystem services and improving the understanding and expression of their values. The findings hint at the right way to address the shared challenge of furthering the sustainable development of the world’s cultural landscape and serve as a guide for creating new rules and guidelines in cultural landscapes. Several factors are still at play as globalization accelerates, like the difficulties of conducting fieldwork because of the epidemic and the theoretical confinement of research. The study of cultural landscapes ought to concentrate on recommending workable environmental ecological protection measures in developing cultural ecosystems, improving the reflection of cultural characteristics, and jointly promoting global ecological governance under the dual creation of material benefits and the spiritual wealth of the cultural landscape.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Wenhui Zhou, Jeremy Cenci, and Jiazhen Zhang. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Wenhui Zhou, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The authors do not have the right to share the data. However, they will be made available to the reader upon reasonable request.

Consent to publish

All authors agree with the content and have given their explicit consent to submit and publish the paper.

Ethical approval

All authors affirm that objectivity and transparency in research has been ensured and ensure that the accepted principles of ethical and professional conduct have been followed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Wenhui Zhou

Wenhui Zhou is a student at the University of Northwest Agriculture and Forestry University, Yangling District, Xianyang, China.

Jeremy Cenci

Jeremy Cenci holding a Ph.D degree in Architecture and Urban Planning is a lecturer at the University of Mons, Belgium.

Jiazhen Zhang

Jiazhen Zhang holding a Ph.D degree in Architecture and Urban Planning at the University of Mons, Belgium.

References

- Anqi, D., J. Cenci, and J. Zhang. 2022. “Links Between the Pandemic and Urban Green Spaces, a Perspective on Spatial Indices of Landscape Garden Cities in China.” Sustainable Cities and Society 85:104046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2022.104046.

- Antrop, M. 2005. “Why Landscapes of the Past are Important for the Future.” Landscape and Urban Planning 70 (1–2): 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2003.10.002.

- Arora, S. K., A. L. Porter, J. Youtie, and P. Shapira. 2013. “Capturing New Developments in an Emerging Technology: An Updated Search Strategy for Identifying Nanotechnology Research Outputs.” Scientometrics 95 (1): 351–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-012-0903-6.

- Bandarin, F., and R. Van Oers. 2012. The Historic Urban Landscape: Managing Heritage in an Urban Century. John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119968115.

- Bibri, S. E. 2019. “On the Sustainability of Smart and Smarter Cities in the Era of Big Data: An Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Literature Review.” Journal of Big Data 6 (1): 1–64. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40537-019-0182-7.

- Blake, J. 2000. “On Defining the Cultural Heritage.” International & Comparative Law Quarterly 49 (1): 61–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002058930006396X.

- Cameron, C., and M. Rössler. 2016. Many Voices, One Vision: The Early Years of the World Heritage Convention. Routledge.

- Carr, A. 2020. “COVID-19, Indigenous Peoples and Tourism: A View from New Zealand.” Tourism Geographies 22 (3): 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1768433.

- Chain, C. P., A. Santos, C. LGd, and P. JWd. 2019. “Bibliometric Analysis of the Quantitative Methods Applied to the Measurement of Industrial Clusters.” Journal of Economic Surveys 33 (1): 60–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12267.

- Cheng, F.-F., Y.-W. Huang, H.-C. Yu, and C.-S. Wu. 2018. “Mapping Knowledge Structure by Keyword Co-Occurrence and Social Network Analysis: Evidence from Library Hi Tech Between 2006 and 2017.” Library Hi Tech 36 (4): 636–650. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-01-2018-0004.

- Cheng, Q., J. Wang, W. Lu, Y. Huang, and Y. Bu. 2020. “Keyword-Citation-Keyword Network: A New Perspective of Discipline Knowledge Structure Analysis.” Scientometrics 124 (3): 1923–1943. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03576-5.

- Cohen, B. 2004. “Urban Growth in Developing Countries: A Review of Current Trends and a Caution Regarding Existing Forecasts.” World Development 32 (1): 23–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2003.04.008.

- de Almeida, E. C. E., J. A. Guimarães, and E. C. E. de Almeida. 2013. “Brazil’s Growing Production of Scientific Articles—How are We Doing with Review Articles and Other Qualitative Indicators?” Scientometrics 97 (2): 287–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-013-0967-y.

- Demetrescu, E., E. d’Annibale, D. Ferdani, and B. Fanini. 2020. “Digital Replica of Cultural Landscapes: An Experimental Reality-Based Workflow to Create Realistic, Interactive Open World Experiences.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 41:125–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2019.07.018.

- Fang, W., Z. Liu, and A. R. S. Putra. 2022. “Role of Research and Development in Green Economic Growth Through Renewable Energy Development: Empirical Evidence from South Asia.” Renewable Energy 194:1142–1152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2022.04.125.

- Forsyth, M. 2014. “Conservation of Garden Buildings.” Gardens & Landscapes in Historic Building Conservation 10 (1002): 67–78.

- Fouberg, E. H., A. B. Murphy, and H. J. De Blij. 2015. Human Geography: People, Place, and Culture. Germany: John Wiley & Sons.

- Gao, J., and B. Wu. 2017. “Revitalizing Traditional Villages Through Rural Tourism: A Case Study of Yuanjia Village, Shaanxi Province, China.” Tourism Management 63:223–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.04.003.

- Geng, Y., R. Zhu, and M. Maimaituerxun. 2022. “Bibliometric Review of Carbon Neutrality with CiteSpace: Evolution, Trends, and Framework.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 29 (51): 76668–76686. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-23283-3.

- Girard, L. F., F. Nocca, and A. Gravagnuolo. 2019. “Matera: City of Nature, City of Culture, City of Regeneration. Towards a Landscape-Based and Culture-Based Urban Circular Economy.” Aestimum 25 (1): 5–42.

- Graham, B., G. Ashworth, and J. Tunbridge. 2016. A Geography of Heritage. Routledge.

- Griffon, S., A. Nespoulous, J.-P. Cheylan, P. Marty, and D. Auclair. 2011. “Virtual Reality for Cultural Landscape Visualization.” Virtual Reality 15 (4): 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-010-0160-z.

- Heilig, L., and S. Voß. 2014. “A Scientometric Analysis of Cloud Computing Literature.” IEEE Transactions on Cloud Computing 2 (3): 266–278. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCC.2014.2321168.

- Hong, R., C. Xiang, H. Liu, A. Glowacz, and W. Pan. 2019. “Visualizing the Knowledge Structure and Research Evolution of Infrared Detection Technology Studies.” Information 10 (7): 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/info10070227.

- Jones, M. 2003. “The Concept of Cultural Landscape: Discourse and Narratives.” Landscape Interfaces: Cultural Heritage in Changing Landscapes 86 (50): 21–51.

- Kaftan, V., W. Kandalov, I. Molodtsov, A. Sherstobitova, and W. Strielkowski. 2023. “Socio-Economic Stability and Sustainable Development in the Post-COVID Era: Lessons for the Business and Economic Leaders.” Sustainability 15 (4): 2876. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042876.

- Kang, X., M. Wang, J. Lin, and X. Li. 2022. “Trends and Status in Resources Security, Ecological Stability, and Sustainable Development Research: A Systematic Analysis.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 29 (33): 50192–50207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-19412-7.

- Labadi, S., F. Giliberto, I. Rosetti, L. Shetabi, and E. Yildirim. 2021. “Heritage and the Sustainable Development Goals: Policy Guidance for Heritage and Development Actors.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 5 (13).

- Lin, Z., L. Zhang, S. Tang, Y. Song, and X. Ye. 2021. “Evaluating Cultural Landscape Remediation Design Based on VR Technology.” ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 10 (6): 423. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi10060423.

- Li, Y., L. Peng, C. Wu, and J. Zhang. 2022. “Street View Imagery (SVI) in the Built Environment: A Theoretical and Systematic Review.” Buildings 12 (8): 1167. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12081167.

- Liu, Q. X., Y. H. Duan, and J. Y. Deng. 2012. “Geological Protection Project of the Longmen Grottoes in Luoyang, Advanced Materials Research.” Advanced Materials Research 594-597:155–160. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.594-597.155.

- Li, Y., Z. Xu, X. Wang, and X. Wang. 2020. “A Bibliometric Analysis on Deep Learning During 2007–2019.” International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics 11:2807–2826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13042-020-01152-0.

- LI, R., and Y. A. N. Y. 2020. “Conservation and Innovation of Cultural Landscape Heritage for Residents of Historical Minority Areas.” In The Case of Fenghuang in Xiangxi, China, Italy.

- Marine, N. 2022. “Landscape Assessment Methods Derived from the European Landscape Convention: Comparison of Three Spanish Cases.” Earth 3 (2): 522–536. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth3020031.

- Ming, N. 2021. “Characteristics and Trends of English Testing Research in China: Visual Analysis Based on CiteSpace.” Region-Educational Research and Reviews 3 (3): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.32629/rerr.v3i3.386.

- Mommaas, H. 2004. “Cultural Clusters and the Post-Industrial City: Towards the Remapping of Urban Cultural Policy.” Urban Studies 41 (3): 507–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098042000178663.

- Moral-Muñoz, J. A., A. G. López-Herrera, E. Herrera-Viedma, and M. J. Cobo. 2019. “Science Mapping Analysis Software Tools: A Review.” Springer Handbook of Science and Technology Indicators 1 (20): 159–185.

- Naveh, Z., and A. S. Lieberman. 2013. Landscape Ecology: Theory and Application. London: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Neumann, R., S. Parry, and T. Becher. 2002. “Teaching and Learning in Their Disciplinary Contexts: A Conceptual Analysis.” Studies in Higher Education 27 (4): 405–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/0307507022000011525.

- Palmatier, R. W., M. B. Houston, and J. Hulland. 2018. Review Articles: Purpose, Process, and Structure, 1–5. London: Springer.

- Plieninger, T., and C. Bieling. 2012. “Connecting Cultural Landscapes to Resilience.” Resilience and the Cultural Landscape: Understanding and Managing Change in Human-Shaped Environments 3–26.

- Poon, S. T. 2019. “Aesthetics versus Functionality of Ecodesign: Exploring Sustainable Architectural Models Based on Ecological and Bioclimatic Design Principles.“ In Global Perspectives on Eco-Aesthetics and Eco-Ethics, edited byMaiti, Krishanu and Chakraborty Soumyadeep, 111. New york: A Green Critique.

- Porter, N. 2020. “Strategic Planning and Place Branding in a World Heritage Cultural Landscape: A Case Study of the English Lake District, UK.” European Planning Studies 28 (7): 1291–1314. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1701297.

- Ravis, T., and B. Notkin. 2020. “Urban Bites and Agrarian Bytes: Digital Agriculture and Extended Urbanization.” Berkeley Planning Journal 31 (1). https://doi.org/10.5070/BP331044067.

- Rawat, K. S., and S. K. Sood. 2021. “Knowledge Mapping of Computer Applications in Education Using CiteSpace.” Computer Applications in Engineering Education 29 (5): 1324–1339. https://doi.org/10.1002/cae.22388.

- Santos, N., and C. O. Moreira. 2021. “Uncertainty and Expectations in Portugal’s Tourism Activities. Impacts of COVID-19.” Research in Globalization 3:100071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resglo.2021.100071.

- Sarkar, A., H. Wang, A. Rahman, W. H. Memon, and L. Qian. 2022. “A Bibliometric Analysis of Sustainable Agriculture: Based on the Web of Science (WOS) Platform.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 29 (26): 38928–38949. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-022-19632-x.

- Sather-Wagstaff, J. 2016. Heritage That Hurts: Tourists in the Memoryscapes of September 11. Routledge.

- Seardo, B. M. 2015. “Biodiversity and Landscape Policies: Towards an Integration? A European Overview.” Nature Policies and Landscape Policies: Towards an Alliance 18 (1): 261–268.

- Silberman, N. 2006. “The ICOMOS-Ename Charter Initiative: Rethinking the Role of Heritage Interpretation in the 21 St Century, the George Wright Forum.” JSTOR 23 (1): 28–33.

- Silva, K. D. 2022. “Mapping Intangible Cultural Heritage in Asian Historic Urban Landscapes.” In The Routledge Handbook of Cultural Landscape Heritage in the Asia-Pacific, 356–370. Routledge.

- Stenseke, M. 2009. “Local Participation in Cultural Landscape Maintenance: Lessons from Sweden.” Land Use Policy 26 (2): 214–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.01.005.

- Wilson, C., P. E. Groth, and P. Groth. 2003. Everyday America: Cultural Landscape Studies After JB Jackson. USA: Univ of California Press.

- Wu, C., J. Cenci, W. Wang, and J. Zhang. 2022. “Resilient City: Characterization, Challenges and Outlooks.” Buildings 12 (5): 516. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12050516.

- Xie, Y., X. Meng, J. Cenci, and J. Zhang. 2022. “Spatial Pattern and Formation Mechanism of Rural Tourism Resources in China: Evidence from 1470 National Leisure Villages.” ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 11 (8): 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi11080455.

- Xu, Y., J. Lyu, H. Liu, and Y. Xue. 2022. “A Bibliometric and Visualized Analysis of the Global Literature on Black Soil Conservation from 1983–2022 Based on CiteSpace and VOSviewer.” Agronomy 12 (10): 2432. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12102432.

- Yao, M., B. Yao, J. Cenci, C. Liao, and J. Zhang. 2023. “Visualisation of High-Density City Research Evolution, Trends, and Outlook in the 21st Century.” Land 12 (2): 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12020485.

- Zeng, R., and A. Chini. 2017. “A Review of Research on Embodied Energy of Buildings Using Bibliometric Analysis.” Energy and Buildings 155:172–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2017.09.025.

- Zhang, J., J. Cenci, V. Becue, and S. Koutra. 2021. “The Overview of the Conservation and Renewal of the Industrial Belgian Heritage as a Vector for Cultural Regeneration.” Information 12 (1): 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12010027.

- Zhang, J., J. Cenci, V. Becue, S. Koutra, and C. S. Ioakimidis. 2020. “Recent Evolution of Research on Industrial Heritage in Western Europe and China Based on Bibliometric Analysis.” Sustainability 12 (13): 5348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12135348.

- Zhang, J., Q. Wang, Y. Xia, and K. Furuya. 2022. “Knowledge Map of Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development: A Visual Analysis Using CiteSpace.” Land 11 (3): 331. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030331.

- Zhuang, Q., M. Hussein, N. Ariffin, and M. Yunos. 2022. “Landscape Character: A Knowledge Mapping Analysis Using CiteSpace.” International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology 19 (10): 10477–10492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-022-04279-5.

- Zhu, Y., S. Koutra, and J. Zhang. 2022. “Zero-Carbon Communities: Research Hotspots, Evolution, and Prospects.” Buildings 12 (5): 674. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12050674.

- Zuo, Z., J. Cheng, H. Guo, and Y. Li. 2021. “Knowledge Mapping of Research on Strategic Mineral Resource Security: A Visual Analysis Using CiteSpace.” Resources Policy 74:102372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2021.102372.