ABSTRACT

Rural industrial heritage reflects the ongoing changes in natural environmental, socio-economic, and cultural historical processes in the countryside. In the context of urbanization, the study, conservation, and reuse of rural industrial heritage have become necessary to consolidate the local community identity and promote rural development. This study aims at establishing an intervention tool with general applicability to regenerate rural industrial heritage while integrating local sustainable development. Through a diagrammatic analysis of the natural and artificial environment, this paper combines three aspects via a layered approach: landscape analysis, urban morphology, and spatial cognition. A layered model of rural industrial heritage regeneration is established, with space and consciousness as its core. The empirical study, using the example of the Shecun lime kiln, demonstrates that the spatial-consciousness layered model (SCLM) clearly explains the core roles of transforming material elements as spatial power and the evolution of cognitive elements as consciousness power in the regeneration of rural industrial heritage. It is a systemic model with adaptable and sustainable analysis. SCLM not only provides indicative strategies but serves as a management tool for the regeneration practices of rural industrial heritage.

1. Introduction

With rapid urbanization in the past decades, a large amount of traditional industrial production in rural areas has been abandoned due to labor loss, low productivity, and negative environmental impacts (Antrop Citation2004; Liu Citation2018). As a result, the related buildings, sheds, sites, facilities, and equipment have become obsolete relics of rural areas (Zhang et al. Citation2017). With the current revival of rural areas, however, these negative elements are being fully assessed, adapted, and reused (Fuentes et al. Citation2010; I.; García and Ayuga Citation2007). These remnants carry the history of the development of rural industries; reflect the subsistence activities of local people in response to specific conditions; and bear historical, social, technological, and scientific value. As a type of industrial heritage (TICCIH Citation2003) and rural landscape (ICOMOS Citation2019), they are important nonrenewable resources for rural development. After the pandemic in 2019, these rural historico-cultural resources became important capitals for promoting rural leisure industries, increasing employment of surplus labor, and enhancing the well-being of local residents, especially in the coordinated development of rural and urban areas (Ge et al. Citation2022, Mubeen et al. Citation2021; Wang et al. Citation2023). Integrating the regeneration of these remnants with local spatial practices based on respect for their values and territorial characteristics can promote the sustainable development of social, economic, cultural, and ecological environments in rural areas (Balsalobre-Lorente et al. Citation2023; van der Vaart Citation2005).

Rural industrial heritage is the result of local, economic production activities undertaken using resources from the natural environment. It is also the consequence of long-term and continuous interaction between local people and the environment, and contains both artificial and natural properties (Sauer Citation1996). Rural industrial heritage plays an important role in the maintenance of the territorial identity of rural areas and the recognizability of landscape forms (Kong, Lin, and Dai Citation2021). Therefore, the regeneration of rural industrial heritage needs to be grounded in the native environment and within a holistic territorial interpretation that considers natural and socio-economic relationships and cultural networks (Xiong et al. Citation2022). Although some approaches to urban industrial heritage regeneration are being applied to rural areas, they favor the weaving of urban structural relationships and the renewal of large-scale plots with complex property rights (Jeong-Hwan et al. Citation2016; Wang et al. Citation2022; Zhang Citation2019) or only focus on the restoration of rural landscape appearance and ecological relations and the physical renewal approaches of heritage building reuse (Fuentes Citation2010). All these interventions demonstrate the difficulties of effectively addressing the community properties of space and ideology in rural areas. The increasingly complex stakeholder networks in villages necessitate dynamic and sustainable innovative approaches to stimulate the role of social media in local development (Abbas et al. Citation2019; Li et al. Citation2022). Hence, in countries and regions where the rural industrial heritage is diverse, the socio-economic development varies widely, and the traditional cultural genes are profound, there is a great need for a universal approach that can adapt to the different characteristics, clearly explains the relationship between artificial activity and the environment, and integrates heritage regeneration in a process of complete historicization.

A layers approach is essentially a methodological basis for deconstructing and interpreting complex systems, recognizing and analyzing internal relationships, and later superimposing them (Xu and Chen Citation2020). In terms of landscape ecology, stratification and classification are applied to describe and analyze a set of homogeneous elements within a spatial unit to identify characteristics and perform an ecological impact assessment of landscape elements, such as topography, soil, vegetation, water, and mineral resources (Eliot Citation1896; Howard and Mitchell Citation1980; Neckar Citation1989). The projection of information about landscape elements onto geographical maps through mapping methods means that ecological maps can serve as a tool for specific purposes (Corner Citation1999; Ozenda and Borel Citation2000). Urban form analysis is generally based on simplified urban map-bottom relationships (Cai Citation2008), which graphically represent the material elements of the city through fractal, typological, morphological, and semiotic theories (Oliveira and Medeiros Citation2016; Xiong Citation2018). The transparent relationships and historical evolutionary rules among the elements as well as the systemic structure of the city parts, such as blocks, plots, buildings, roads, and squares, are analyzed (Xu and Chen Citation2020). In cognitive studies on abstract space, the relationship between symbolic space and public consciousness has been analyzed by diagrammatically mapping public perceptions of urban space to urban elements, such as cognitive maps (Lynch Citation1960) and mental maps (Rapoport Citation1997). The aim is to find urban design solutions by linking human behavior to physical space. John Short (Citation1984) proposed a layered structural model of social space and superimposed it on the material space layer to explain the relationship between space production and society. These approaches reflect only one aspect of a case and do not focus on the linkages between different aspects of this case. The integration of rural industrial heritage regeneration and local development requires a combination of physical spatial and conscious elements based on the three-layered approaches described above.

This paper aimed to develop a practical approach for integrating rural industrial heritage regeneration and local sustainable development by performing a case study. This study combines the strengths of existing layer approaches to incorporate natural landscapes, artificial environments, and the behavioral logic of stakeholders into a systematic methodological framework. By explaining the internal relationships among the elements, a spatial-conscious layered model (SCLM) is developed as a universally sustainable tool to support integration of heritage intervention and local planning. This model can suggest planning and design choices for rural industrial heritage regeneration practices.

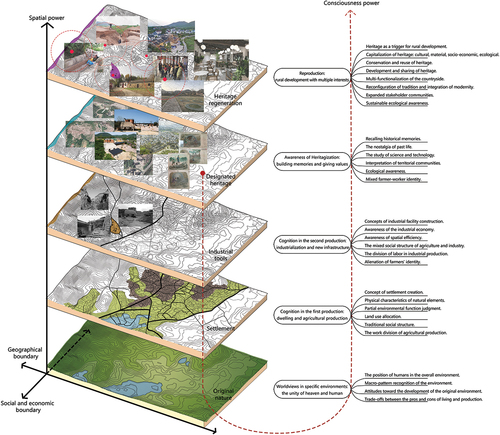

This article first establishes the conceptual framework of SCLM based on a literature review and analysis of existing methods. Thereafter, the layered process and the operability of the model are validated via a case study of Shecun Village. Finally, this study discusses the spatio-temporal logic, applicability, and overall sustainability of SCLM and summarizes the shortcomings and possible directions for future research ().

2. Methodology and materials

2.1. Diagrammatic analysis: construction of concept model

The regeneration of industrial heritage and local development involves many stakeholders (Zhang et al. Citation2022). With the rise of rural tourism, spatial information analysis methods, such as kernel densities and imbalance indices, have been used to analyze the distributional characteristics and structural changes of rural spaces at large regional scales (Xie et al. Citation2022; Zhan, Cenci, and Zhang Citation2022). Particularly in the post-pandemic era, questionnaire surveys of different groups in the countryside on their perceptions of the local environment (Abbas et al. Citation2019; Li et al. Citation2022) and analyses through economic data matrices and regression models can provide insights into consciousness changes and social network characteristics of local complex interest groups (Liu et al. Citation2021; Shah et al. Citation2023). These methods provide evidence to explain the complex contradictions that emerge in the process of rural development, but do not provide guidance on intervention behavior for specific engineering practices. Linking typical spatial practice approaches (Sabaté-Bel Citation2008) and rural industrial heritage regeneration patterns (Xiong et al. Citation2022) and embedding corresponding consciousness changes is the only way to leverage the strengths of heritage resources for local sustainable development.

From the perspective of a project, a longitudinal analysis of spatiotemporal evolution should be combined with a cross-sectional characterization of socio-economic slices. Therefore, this study utilized a diagrammatic approach, which is suitable for architects, planners, and managers, for heritage intervention and spatial practice. In rural areas, the long-term relationships between productive activities and the local environment in a specific space need to be analyzed through deconstruction and stratification to obtain favorable conditions for heritage regeneration. The territory where the heritage is located as a whole is considered the diagrammatic object. Software, such as ArcGIS, AutoCAD, and Sketchup, is used to compare, categorize, and superimpose geographic information, textual data, on-site drawings, images, and consciousness symbols to form a diagrammatic representation of spatial models and layers (Garritzmann and Deen Citation1998; Tortora, Statuto, and Picuno Citation2015). In adherence to the progressive logic of local social development, our study comprises the following stages, focusing on human subsistence production and starting from the most basic spatial elements and consciousness: a) cognition of local natural conditions, b) residential construction and agricultural production according to natural features, c) industrial production, d) industrial remains recognized as a heritage, e) effective regeneration interventions, f) other possible future measures (open ones).

The information corresponding to each stage is separated and mapped into a single layer. The spatial elements contain topographical features, water systems, built environment, infrastructure, open spaces, and territorial structures, among others (Sabaté-Bel Citation2008). The consciousness elements include the interrelation between the activities of local people at different historical stages, perception of land use patterns, socio-economic relations, division structure of labor among villagers, and cultural customs (Alessio et al. Citation2016). The layers of each stage contain two types of slices: material space and consciousness logic. The vertical superposition of these layers reflects the evolutionary relationship of the same type of elements in two adjacent layers. The slices at the same horizontal level reflect the interaction between the spatial layer and the consciousness layer. The layer superposition, driven by the space and consciousness transformation, becomes the core of the spatial-consciousness layered model. The relationships between the layers are simplified, separated, analyzed, and interpreted to reveal the evidence for the final heritage regeneration scheme ().

2.2. Study area

The rural industrialization of China is a long and complex process, which comprises four stages (Yu Citation2012). The first stage (before 1840), proto-industrialization, was dominated by traditional handicraft production and family workshops based on agricultural production during the feudal system; the second stage (1840–1949), semi-industrialization, was a mixture of family handicrafts and modern machine production in the context of a semi-colonial and semi-feudal society; the third stage (1949–1978), communal industrialization, concentrated farmers as ordered groups developing rural light industry and agriculture in the context of the planned economy system during the infancy of the People’s Republic of China; the fourth stage (1978–2011), township industrialization, was led by market competition encouraging free production of farmers after Reform and Opening-up. Notably, rural industrial development in China has never been separate from agriculture and farmers nor existed as secondary to agriculture. Unlike in Western countries, in an agricultural civilization like China, the rural industrial development from antiquity to modernity has had a continuous intimate relationship with the local environment and social structure (Peng, Liu, and Sun Citation2016; Xiong and Wang Citation2023). A large number of distinctive types of industrial remnants were formed in the different contexts of productivity and socio-economy of different stages, and these remnants are useful for understanding rural industrialization paths. In the current process of rural revitalization, the intervention in these remnants inevitably involves examining the tangible and intangible elements in their associated historical process. In other words, the rural industrial heritage has been the identity representation of local history, and its regeneration is the integration of related elements in the search for local sustainable development.

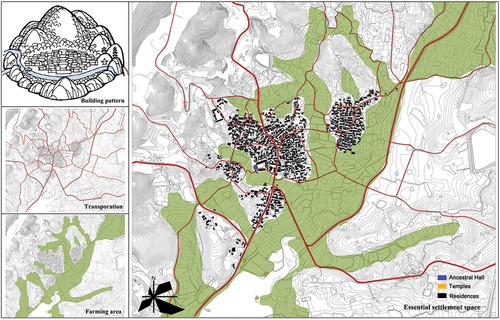

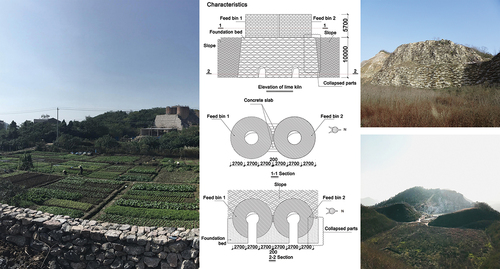

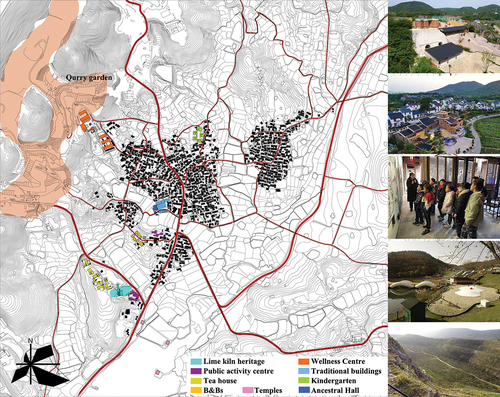

In this study, Shecun Village was considered the research object to validate the proposed model, which is located in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China. Generally, Shecun Village is a rural community containing six areas, and this study refers to its core areas (). Historical records and drawings of Shecun Village, such as data on socio-economic changes, geographic maps, and historical information on the lime kiln (Su Citation2022), engineering documents of Shecun Village’s planning and construction from the Shecun Village’s Planning and Management Department, and aerial photographs and site mapping drawings of the lime kiln from the research team, are the main materials for this study. As with many agro-industrial sites in China, Shecun Village was traditionally a place where the agricultural community (layer 2) developed by adapting to natural conditions (layer 1). However, following the influence of Western industrialization in the late 19th century, the exploitation of natural resources has brought great spatial and social changes (layer 3). Later, from the end of the 20th century, rapid urbanization again brought change to the village (layer 4). The concept of industrial cultural heritage is being utilized as an alternative to existing facilities, such as an old brick kiln transformed into a traditional handicraft experience shop, to incentivize the development of the village (layer 5).

Shecun Village is located on a narrow hilly terrain of Qinglong Mountain, where lush trees, a warm climate, and abundant rainfall have promoted local residential life and agricultural development (Xiong et al. Citation2022). Around 1370, a group of people escaping the Ming dynasty’s war of unification first arrived in the village and began to settle by building simple houses and reclaiming land (Su Citation2022). The west side of the mountain range is rich in limestone, which is advantageous for local industrial production. There are many industrial facilities, such as quarries, workshops, and lime kilns around the village. For more than 650 years, the hilly mountains have provided a safe living and production environment for indigenous people and have accumulated many natural and human landscapes. Shecun Village is a typical example of a traditional Chinese village, and its spatial system is shaped by the combined effects of culture, economy, environment, and society (Xiong et al. Citation2022). The existing historical buildings, industrial landscapes, natural elements, and local daily activities create a harmonious cluster pattern of “mountains, water, farmlands, forests and living” (Zheng et al. Citation2022).

However, due to the ecological damage caused by the mining industry, the local government announced the closure of all lime mines and factories in 2007. In 2017, in the context of the national rural revitalization strategy, with the goal of creating a characteristic rural village, Shecun Village began to be replanned and constructed, and the lime kiln and mining area became the key objects of interventions. In this context, the spatial contradictions, social complexity, and the efficient integration between the regeneration of cultural heritage and local planning that Shecun Village has faced represent problems common to most villages that need to be solved. In terms of representativeness, the Shecun ash kiln and the integrity of the settlement environment in which it is situated are consistent with the typical characteristics of rural industrial heritage (Xiong et al. Citation2022), and the revitalization of Shecun village reflects the current direction of traditional village development in China (Zheng et al. Citation2022). Identifying scientific approaches to solve a series of problems through the study of Shecun Village can effectively help relevant theoretical research and rural practice.

3. Results: case study

3.1. First layer: natural environment and cognitive consciousness

A suitable natural environment is a prerequisite for local people to settle (Han et al. Citation2019). Valleys are relatively hidden and promote a safe and comfortable productive life. High-quality soils and gentle slopes are conducive to farming. Houses can be built on tableland to avoid flooding. The lowlands at the foot of the mountain can be used for water storage and irrigation or as fish ponds. Minerals can be exploited to further develop the local economy. Trees are free building materials and fuel, as well as a pleasant landscape for promoting mental and physical health. These favorable functional elements ensure an organic living space in the countryside (Yu et al. Citation2017).

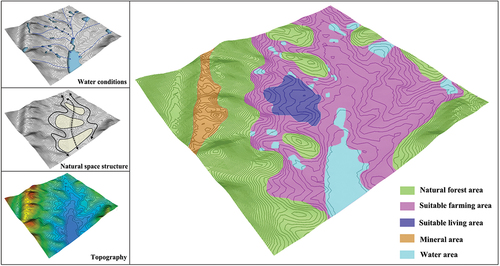

According to She Village Records and oral narratives of the Pan family’s descendants, the villagers, under the influence of the traditional Feng Shui concept, who first arrived there believed the place was a piece of “Feng Shui Treasure,” and chose the settlement based on their observations of the natural environment (Su Citation2022; Xiong et al. Citation2022). Different natural conditions determined the use and development of specific spaces (). The original condition of the natural environment gave the locals a reason to settle. Local people map their cognition and intergenerational experience onto the natural elements, which are constantly transformed and redeveloped. This layer is the most basic spatial element of the settlement and is the basis for all development.

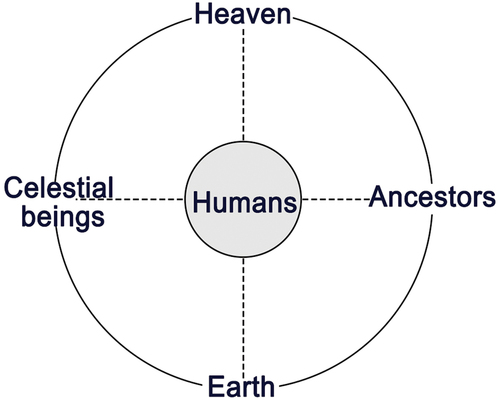

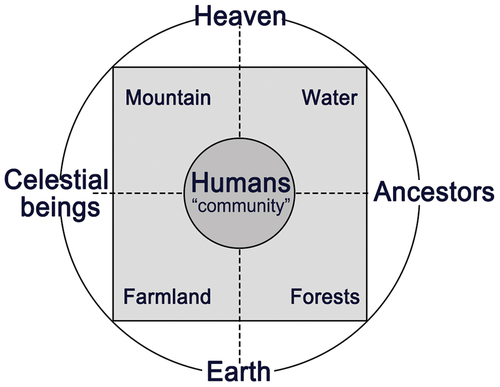

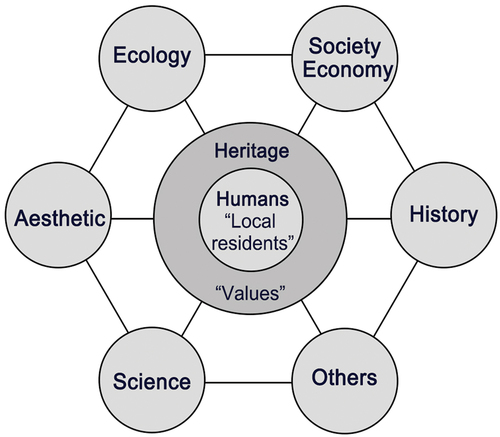

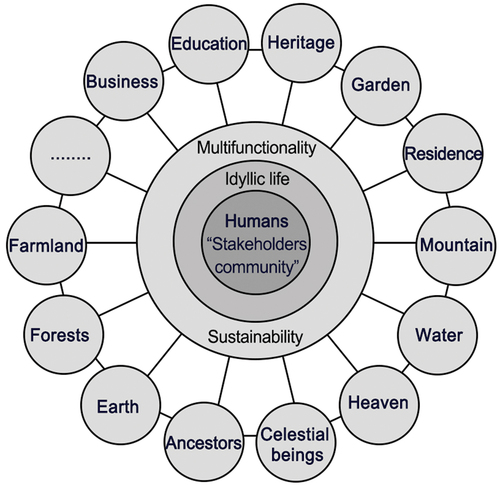

The traditional worldview of the farmers was an eternal cyclical system centered on the individual (Wang et al. Citation2022). Heaven and earth, as vertical poles, were considered irreplaceable sources of all hope for survival. Heaven and earth are considered to be alive and whole assemblages of human beings (Wang Citation2009). Ancestors and celestial beings, as the horizontal poles, are the spiritual ballast of the local people. The ancestors pass on the mission to keep life going, and celestial beings can help fulfill wishes. Humans, at the intersection of the horizontal and vertical, are the core of the entire traditional consciousness ().

Natural environments in the first layer reflect the essential relationships of physical space and the characteristics of the topography. The human-centered worldview determines the local people’s attitude and approach to their surroundings. Local people adapted themselves to the basic natural elements such as geographic patterns, climatic characteristics, soil, and plants through their basic sense of survival and their productive and daily activities (Yu et al. Citation2017). The primary consciousness reflected by the natural elements and the original environment represented by the consciousness together formed the fundamentals of the whole territorial cultural space.

3.2. Second layer: agriculture settlement and function consciousness

The second layer reflects the transformation of the original environment to meet the goals of daily living and agricultural production based on the spatial and consciousness elements in the first layer. The common pattern in building a settlement, namely “backed by mountains and facing the water, sitting north to south, surrounded by mountains and water,” is the result of interactions among the elements in the first layer. It makes full use of the orientation of the sun in the northern hemisphere and the climatic conditions of the mountains, which are windproof in winter and windward in summer (Xiong et al. Citation2022). This pattern determines the location and orientation of the settlement. The spatial elements in this layer are the result of artificial intervention based on natural elements and facilitate different functions ().

The advancement of daily activities led to the traditional human-centered worldview incorporating a clear functional perception of natural spatial elements within the essential consciousness framework. The four elements, mountain, water, field, and forest, were detached from nature and given a special meaning. They become inseparable parts of the eternal cycle system surrounding the settlement. Compared to the original traditional worldview, the core of this layer has changed from the individuals to the local group of farmers. Blood relatives, local ties, cultural habits, and moral order make the village society an organic community with a contractual spirit (Tonnies Citation1988). It is a social network of acquaintances (Fei Citation2019) ().

The spatial changes in the second layer reflect the first spatial practices of the locals. The expanded conscious perceptions define the functionality of spatial elements. The isolated spatial elements induce a complex process of consciousness layering (Zheng et al. Citation2022). The accumulations of this layer lay the foundation for further spatial and consciousness transformations.

3.3. Third layer: industrial production tools and expansive consciousness

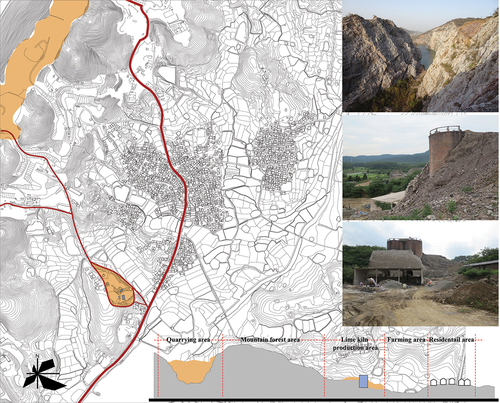

When traditional agriculture failed to meet the economic needs of a growing population, industrial production served as a new economic activity to supplement the income of farmers. Meanwhile, the tools for industrial production emerged as new spatial elements (Han et al. Citation2019). Parts of the mountains were mined to obtain ores as raw materials for industry. Lime kilns were built on the hillside close to the main road, including the around grounds as a working area. Special haul roads were built between the mining and processing areas. The main road was also widened to allow the transportation and sale of industrial products. As new artificial elements, the different industrial production tools were positioned differently in the settlement space (Su Citation2022). To reduce the impact on agricultural and residential areas, the mines were located in distant valleys. To allow workers to commute, the lime kiln was built on a hillside near the dwellings and not on farmland. The altitude difference in the terrain meets the kiln requirements for separate access to the raw material inputs and product outputs. The elevated production area in the southwest of the village favors the local perennial southeastern winds that blow the smoke from calcination away from the housing area. The spatial changes in this layer reveal that agriculture, housing, and industrial production were organically arranged. The regularity in alternating intervals between the artificial and natural environments is reflected in the section ().

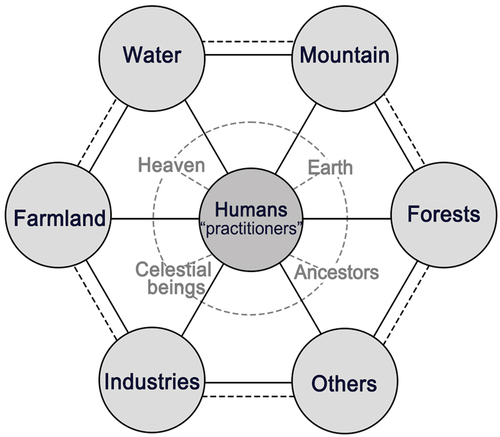

Further development of the local socio-economy emphasized the significance of functional elements, which constitute the main consciousness framework. Mountains, water, farmlands, forests, and lime production, as well as other industries, were regarded with equal importance. Their relationships with the core of consciousness intensified. These elements were not mixed or completely segregated but were linked in an orderly manner and distinguished by their distinct functionalities (Xiong et al. Citation2022). On the contrary, the spiritual attachments to heaven, earth, celestial beings, and ancestors weakened during the period of industrial production. These conscious elements became less binding to the agro-industrial social structure, but they did not disappear, maintaining rather the basic network. As a result of the new social division of labor, occupational differentiation occurred within the original villagers. Workers in charge of lime production, a part of the farmers, workers in other industries, and laborers in charge of household chores together formed a mixed and more complex core group of consciousness (Alessio et al. Citation2016) ().

The professionally distinct locals project different production requirements into the corresponding spatial elements, dictating new spatial practices, such as mining, building, forging, and road construction. Similarly, the spatial relations defined jointly by agricultural and industrial production dictate the conscious acts of utilization, alteration, avoidance, destruction, and recreation. Additionally, the interplay between space and consciousness is also complicated.

3.4. Fourth layer: heritage and value consciousness

After the inefficient industrial production was forced to stop, the tools associated with it lost their original functions and became the real abandoned spatial elements in the rural settlement. The spatial elements in which these relics are the core contain two parts. One part is the spatial elements related to industrial production in the macrospace and its relationship with the production process, including spatial elements and forms of the whole settlement, laborers, and production processes as well as their interrelationships (Gy Citation1998). The second is the material elements that express the microscopic characteristics of the authenticity of the remnants, including construction and site features such as materials, sizes, shapes and structures of buildings, and decorations of facade (Xiong et al. Citation2023) ().

The process by which relics are designated as heritage is the search for a discursive explanation for their continued existence (Torre Citation2020). This process of discursive construction generates a new consciousness layer. With the heritage values that highlight the identity of local residents as the core of the layer, the remnants are recognized from historical and cultural, socio-economic, technological, ecological, and esthetic perspectives. The Shecun lime kiln and quarry reflect the development history and socio-economic changes of the village since modern times and serve as memory anchors and landscape markers for local people (Kong, Lin, and Dai Citation2021). These remnants also reflect local production and construction techniques in a mixed agro-industrial context in the early industrialized villages. The motivation for the cognition of remnants is to use them to link the past, the present, and the future, searching for their potential to be preserved and reused ().

In the heritagization layer, the spatial elements provide authentic and valid evidence for a discursive interpretation, for which history and the site need to be examined in detail. Meanwhile, the interpretive actions that assign values to the remnants transform the spatial elements from remnants to potential heritage. Heritagization is the clue that connects the preceding and the following in the whole layered model.

3.5. Fifth layer: multifunctional space capitals, conservation, and reuse

With the development of rural tourism, rural industrial heritage and the spatial environment of the entire settlement become spatial capital with development potential (Xiong et al. Citation2022). Industrial heritage acts as a trigger of spatial reorganization, which further complicates the previously superimposed spatial elements. The process of spatial reorganization involves the potential assessment and functional allocation of all spatial aspects within the settlement. The lime kiln and production grounds were transformed into a public exhibition space for traditional lime-making techniques and village history. The unique building shapes have also become landscape landmarks. Mountains, water, farmlands, and forests were kept intact as important ecological elements, and their original functions were strictly protected. Roads, water conservancies, and other infrastructure were replanned. The overall spatial form of the dwellings was preserved, but new public places such as activity centers, kindergartens, and welfare homes, and new commercial places such as B&Bs, restaurants, and tea rooms, were built. Traditional rural public spaces such as ancestral halls and temples were restored to reflect the traditional agricultural social culture. Mining sites were also used as playgrounds and ecological gardens. Ecology, multifunctionality, publicness, wholeness, and coordination are the main characteristics of this layer of spatial elements (Long et al. Citation2022) ().

The conservation and reuse of heritage promotes dialogue and negotiation between local communities and external societies, individuals, and groups (Zhang and Yang Citation2022). The conflicts between the multiple value claims of all stakeholders lead to a consciousness layer aimed at balancing interests. The protection of existing local consciousness and the encroachment of foreign social consciousness transform the consciousness core into a community of stakeholders, including locals, government, tourists, investors, and others. Consciousness elements related to each stakeholder are given equal importance, shared, and interpreted through mutual considerations, including elements that were previously weakened or lost. The aboriginal rights of locals, the idyllic life experience of tourists, the interests of investors, and the management will of the government together form a dense and dynamic radial structure of consciousness elements ().

Interventions in the rural industrial heritage induce changes in spatial elements. The awareness purposes of different stakeholders are achieved by redefining the market potential of spatial elements (Capello, Cerisola, and Perucca Citation2020). The negotiations between multiple elements of consciousness determine the direction of change of spatial elements. Thus, the current heritage interventions do not end the layering process with the temporary equilibrium of a plural consciousness. This leaves room for a new movement in the interplay between space and consciousness.

3.6. Layered model

The layering results of Shecun Village show that the layering process centered on heritage is continuously superimposed by both spatial and conscious forces. Within the designated village boundaries, the natural environment and the built form of the settlement are the material basis of spatial layering. The changing stakeholder groups and their demands are the core of the consciousness layering. The designation of industrial remnants as heritage is the key layer, which triggers a re-examination of all elements in the model and a recognition of their inter-relationships. The conservation and reuse of heritage requires an analysis of the elements of each layer, starting from the original natural layer in order, which ultimately serves as the basis for specific intervention programs. The element superposition of SCLM ranges from simple to complex, but the layering principles and processes are clear and easy to identify. The layered results of SCLM indicate that the conservation and reuse of rural industrial heritage induce the multifunctionality and publicness of the rural whole space ().

4. Discussion

4.1. Space-temporal logic of SCLM

SCLM deconstructs and analyzes the space changes and consciousness elements during each period according to the time series. Time series and node designation are the clues. Determining rural industrial heritage is treated as the center of the timeline for the historical study of the past and the assessment of the present and future. The historical parts start with the study of the environment untouched by human intervention. The emergence of traditional agricultural or industrial production, the designation of industrial heritage, and the redevelopment of the countryside, are selected as nodes on the time series that provide evidence for the layering. The spatial pieces of information within the period between adjacent nodes and the willingness of production and life at that time are deconstructed and analyzed. The designation of nodes and the classification, censoring, and description of elements within the period are crucial for graphically representing the layers (Cullotta and Barbera Citation2011). The definition of nodes and periods vary according to different regions and cases. However, it is important to emphasize the relevance between linear time series and industrial heritage to define the elements in the layers.

Layers represent the changes in spatial elements and consciousness information within each period and explain the internal relationships by reflecting the characteristics of the elements (Cai, Qin, and Guo Citation2022). SCLM constructs the associations of material and consciousness elements between the layers. The stages in the temporal axis are information sets with both causal and progressive relationships (Cho et al. Citation2022). Spatially different information can be deconstructed and matched to make the superposition of layers more transparent in interpretation and representation. The analysis of the current situation and potential assessment following the designation as industrial heritage is the selection and reorganization of elements within the superimposed layers. It promotes elements that satisfy current interests as various capitals for rural redevelopment. The retrospective reconfiguration between the layers finally indicates the most favorable direction for the regeneration of rural industrial heritage ().

4.2. Applicability of SCLM

SCLM is not a universal comprehensive material mapping analysis (Cai, Qin, and Guo Citation2022; Corner Citation1999; Fuentes Citation2010); instead, it focuses on heritage and provides an interpretation and assessment of the past, present, and future of heritage in both the temporal and spatial dimensions. SCLM is both an expressive tool for spatial relationships and a spatial analysis and design. Unlike the diachronic analysis of spatial forms and the search for universal evolutionary rules (Henco et al. Citation2021), the relationship between layers is simplified as a one-way evolution, which presents a progressive state from the most basic relationships. It does not emphasize excessive attention to the material spatial elements and their historical change characteristics. The correspondence between space as a carrier to realize claims and consciousness as a medium to dominate spatial changes objectively reflects the interaction between the transformation of the physical environment and the ideals of local people’s lives (Chang Citation2020).

The diachronic characteristics of changes in spatial and consciousness elements on the time axis and the cotemporal characteristics of spatial and consciousness layers within the time period are separately discussed in a holistic framework. This discussion involves both comparing homogeneous elements at different moments and analyzing the relationship between different homogeneous elements within the same phase. SCLM is less about uncovering the laws of spatial change and more about the interaction between the effects of overall spatial change and heritage conservation and reuse. The top layer is the result of the superposition of the layers and contains the subjective will of any period, which facilitates the balance between bottom-up and top-down interventions. The semi-abstract and symbolic graphical representation clearly explains the correspondence between spatial form and consciousness, and the result is oriented toward indicative practice strategies. SCLM is a tool that can be used for data management and analysis, representation, and inspired design.

4.3. Sustainable model linking the whole

Industrial heritage comprises continuous spaces at multiple levels, and its study, conservation, and reuse are necessarily based on a holistic approach (Liu, Zhao, and Yang Citation2018). The holistic space of heritage does not refer to an existing homogeneous area or a collection of elements, but to a dynamic, inclusive, and resilient system that contains all tangible and intangible elements and their interrelationships within the area (Dobson Citation2012). Therefore, the instruments used to intervene in heritage spaces also require dynamic and sustainable features.

Gkartzios and Gallent et al. (Citation2022) proposed a rural capital planning model that includes economic, socio-cultural, land, and built environment aspects. According to Bourdieu’s theory on the form of capital (Bourdieu Citation1986), these capitals in the countryside are closely interrelated and can be transformed into each other to support spatial energy and sustainability for rural development. SCLM focuses on rural industrial heritage or treats rural industrial heritage as a kind of capital as well as provides a basis for the regeneration of heritage by analyzing the dynamic relationships between environmental space and stakeholder consciousness. In SCLM, the historical evolution of homogenous spatial elements and the consciousness logic of inducing changes are explained, including changes in roads, land use, building functions, and sites.

In addition, sustainable human-land relations are an important issue in current rural development (Xiong et al. Citation2022). COVID-19 has had a profound impact on the behavior of stakeholders in rural communities (Iorember et al. Citation2022). In the post-pandemic era, the regeneration of rural industrial heritage must address more complex problems, such as knowledge sharing in the neighborhood, tourism with blurred social boundaries, and the tourism value of local infrastructures (Li et al. Citation2022; Mamirkulova et al. Citation2020; Yu et al. Citation2022), in a resilient manner. The SCLM, a way to the local natural environment as a initial layer of the superposition model, not only effectively analyzes the complex process of rural industrial production in the past but also lays the foundation for industrial heritage as the capital of local future development. The model accommodates any new elements in an open layering process, which allows heritage regeneration and local development to be organically linked and promotes the overall sustainability of materials and nonmaterials. On the one hand, the superimposed results of known layers and the analysis of layering processes clarify the historical relationship of rural industrial heritage in specific environments. On the other hand, they indicate the direction of present and future interventions as an ensemble of information in a designated area.

5. Conclusion

With the revitalization of the countryside, interventions on rural industrial heritage are required to promote local development and improve the quality of the local habitat. The rural industrial heritage is the result of the selective superposition of new activities on the previous agricultural production, which originated from the interpretation of the local environment. Each change cannot be understood independently nor represented by a single building. Therefore, it is essential to analyze the intrinsic characteristics of each element and their relation as a cultural organization to understand the formation of heritage and establish its possible transformation.

This study develops a tool for regenerating rural industrial heritage that integrates local development. The superimposed process of changes in local space and consciousness is taken as the core of the tool (SCLM). The reliability of SCLM was verified through a graphical analysis of Shecun Village. SCLM is a holistic system in which individual elements are interlinked, and it explains internal relationships. The model analyzes, interprets, and recombines related elements in a given spatial and temporal direction with heritage at the center point. SCLM integrates spatial and consciousness elements and their interrelationships, both as a tool for rural industrial heritage analysis and through the visible layered results leading to a promising regeneration strategy. SCLM offers a superior new way for theory research and practice of rural heritage conservation integrating local development.

Furthermore, SCLM needs to synthesize the layered dynamic processes in a smarter and more visualized analytical way to cope with more complicated cases. More socio-economic data related to rural industrial heritage needs to be loaded into the model in a quantitative manner in coming studies to accurately obtain the layered processes and characteristics. SCLM can reveal the complex dynamic communities of rural heritage conservation management for local administrations. Therefore, in terms of policy, this paper suggests that local governments should use SCLM to find effective ways to balance the conflicts around the heritage regeneration attitudes between locals and rural tourists. It is also recommended that architects, planners, and governors take SCLM as an integrative tool for designing and managing rural environments to identify local sustainable development pathways that combine top-down and bottom-up approaches.

Acknowledgements

First, we would like to thank members of the cultural landscape research group of Polytechnic University of Catalonia for their helpful comments and suggestions on drawings. Second, Special thanks to anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. Lastly, we would like to thank KetengEdit (www.ketengedit.com) for English language editing service during the preparation of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Xiangrui Xiong

Xiangrui Xiong, is a Ph.D. candidate from Southeast University and a joint doctor of the Polytechnic University of Catalonia. His research focuses on territory design, regeneration of rural industrial heritage, and architecture design.

Yanhui Wang

Yanhui Wang, Ph.D., is a nationally certified architect of China. He is a professor at the Research Institute of Architecture at the Southeast University. His research areas are public building design and relative theories, modern architecture heritage conservation and adaptive reuse, and rural heritage.

Meehwa Cho

Meewha Cho, is a Ph.D. candidate, teaching assistant, and research staff in the Department of Urban and Territorial Planning, at the Polytechnic University of Catalonia. Her research focuses on urban history, urban morphology, and Territorial projects.

Melisa Pesoa-Marcilla

Melisa Pesoa Marcilla, Architect (Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Argentina) and Ph.D. in Urbanism (Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya). She is a researcher at the Hitepac/CONICET and a professor at the Department of Urban and Territorial Planning (DUOT-UPC). Her research focuses on urban history, urban morphology, and cultural landscapes.

Joaquín Sabaté-Bel

Joaquín Sabaté Bel, Ph.D., is Chair of Urbanism and researcher at the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. He also is an economist, founder of the International Laboratory of Cultural Landscapes, and editor of the journal Identities. His research activity is focused on the instruments, methods, and theories of urban and territorial projects, and on the relation between heritage resources and local development.

References

- Abbas, J., I. Hussain, S. Hussain, S. Akram, I. Shaheen, and B. Niu. 2019. “The Impact of Knowledge Sharing and Innovation on Sustainable Performance in Islamic Banks: A Mediation Analysis Through a SEM Approach.” Sustainability 11 (15): 4049. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11154049.

- Abbas, J., S. Raza, M. Nurunnabi, M. Minai, and S. Bano. 2019. “The Impact of Entrepreneurial Business Networks on Firms’ Performance Through a Mediating Role of Dynamic Capabilities.” Sustainability 11 (11): 3006. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11113006.

- Alessio, R. RogersA. P. , Verdini, G., Veldpaus, L., Juma, M., Fayad, S., and Zhou, J. 2016. The HUL guidebook managing heritage in dynamic and constantly changing urban environments. Accessed 18 April 2023. https://gohulsite.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/wirey5prpznidqx.pdf.

- Antrop, M. 2004. “Landscape Change and the Urbanization Process in Europe.” Landscape and Urban Planning 67 (1–4): 9–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-2046(03)00026-4.

- Balsalobre-Lorente, D., J. Abbas, C. He, L. Pilař, and S. A. R. Shah. 2023. “Tourism, Urbanization and Natural Resources Rents Matter for Environmental Sustainability: The Leading Role of AI and ICT on Sustainable Development Goals in the Digital Era.” Resources Policy 82:103445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2023.103445.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. Richardson, 241–258. Westport CT, USA: Greenwood .

- Cai, F. 2008. The City in City Maps: Seeking Conceptual Influence on Chinese City’s Morphological Transformation Through Comparison of City Maps. Master, Tongji University. Shanghai.

- Cai, J., X. Qin, and W. Guo. 2022. “A Retrospective Reconstruction: Mapping as an Interpretation and Design Tool for Urban Design.” Landscape Architecture 29 (11): 12–20. https://doi.org/10.14085/j.fjyl.2022.11.0012.09.

- Capello, R., S. Cerisola, and G. Perucca. 2020. “Cultural Heritage, Creativity, and Local Development: A Scientific Research Program.” In Regeneration of the Built Environment from a Circular Economy Perspective. Research for Development, edited by S. Della Torre, S. Cattaneo, C. Lenzi, and A. Zanelli, 11–19. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33256-3_2.

- Chang, Q. 2020. “Chang Qing on Yingzao[营造] and Landscape Architecture.” Chinese Landscape Architecture 36 (2): 41–44.

- Cho, M., M. Pesoa, J. Franquesa, J. Sabaté, X. Xiong, and Q. Wang. 2022. “Interpreting and Designing: Cadastre and Territory in Busan, Tenerife and Bages.” Landscape Architecture 29 (11): 34–48. https://doi.org/10.14085/j.fjyl.2022.11.0034.15.

- Corner, J. 1999. “The Agency of Mapping.” In Mappings, edited by D. Cosgrove, 217–225. London: Reaktion.

- Cullotta, S., and G. Barbera. 2011. “Mapping Traditional Cultural Landscapes in the Mediterranean Area Using a Combined Multidisciplinary Approach: Method and Application to Mount Etna (Sicily; Italy).” Landscape and Urban Planning 100 (1–2): 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.11.012.

- Dobson, S. 2012. “Historic Landscape Characterisation in the Urban Domain.” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Urban Design 165 (1): 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1680/udap.2012.165.1.11.

- Eliot, C. 1896. “The Boston Metropolitan Reservation.” The New England Magazine 21 (1): 117.

- Fei, X. 2019. Native Rural China. Beijing: Zhong Hua Book Company Press.

- Fuentes, J. M. 2010. “Methodological Bases for Documenting and Reusing Vernacular Farm Architecture.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 11 (2): 119–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2009.03.004.

- Fuentes, J. M., E. Gallego, A. I. García, and F. Ayuga. 2010. “New Uses for Old Traditional Farm Buildings: The Case of the Underground Wine Cellars in Spain.” Land Use Policy 27 (3): 738–748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.10.002.

- García, I. A., and F. Ayuga. 2007. “Reuse of Abandoned Buildings and the Rural Landscape: The Situation in Spain.” Transactions of the ASABE 50 (4): 1383–1394. https://doi.org/10.13031/2013.23627.

- Garritzmann, U., and W. Deen. 1998. “Diagramming the Contemporary. OMA's little helper in the quest for the new.” OASE 48:83–92.

- Ge, T., J. Abbas, R. Ullah, A. Abbas, I. Sadiq, and R. Zhang. 2022. “Women’s Entrepreneurial Contribution to Family Income: Innovative Technologies Promote Females’ Entrepreneurship Amid COVID-19 Crisis.” Frontiers in Psychology 13:828040. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.828040.

- Gkartzios, M., N. Gallent, and M. Scott. 2022. “A Capitals Framework for Rural Areas: ‘Place-planning’ the Global Countryside.” Habitat International 127:127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2022.102625.

- Gy, R. 1998. “Rural Buildings and Environment.” Landscape and Urban Planning 41 (2): 93–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(97)00062-5.

- Han, X., J. Zheng, W. Shi, X. Han, and X. Zhou. 2019. “An Analysis of the Elements and Features of the Cultural Landscape in the Landing Domain of Guyao Village.” Agriculture of Jilin 17:44–45. https://doi.org/10.14025/j.cnki.jlny.2019.17.019.

- Henco, B., J. Cai, J. Kuijper, K. Zhang, and W. Chen. 2021. Mapping Wuhan: Morphological Atlas of the Urbanization of a Chinese City. The Netherlands, Delft: TU Delft OPEN Publishing.

- Howard, J. A., and C. W. Mitchell. 1980. “Phyto-Geomorphic Classification of the Landscape.” Geoforum 11 (2): 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7185(80)90001-9.

- ICOMOS. 2019. Rural Heritage: Landscapes and Beyond. Accessed May 12, 2023. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/icomos_isccl/2019/.

- Iorember, P. T., B. Iormom, T. P. Jato, and J. Abbas. 2022. “Understanding the Bearable Link Between Ecology and Health Outcomes: The Criticality of Human Capital Development and Energy Use.” Heliyon 8 (12): e12611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12611.

- Jeong-Hwan, L., Y. Won-Keun, C. Sik-In, and K. Jin-Hyuk. 2016. “Conservation of Korean Rural Heritage Through the Use of Ecomuseums.” Journal of Resources and Ecology 7 (3): 163–169. https://doi.org/10.5814/j.issn.1674-764x.2016.03.003.

- Kong, W., X. Lin, and F. Dai. 2021. “Establishing the Landscape Conservation System of Traditional Settlements in China.” Heritage Architecture 47–55. https://doi.org/10.19673/j.cnki.ha.2021.03.006.

- Li, X., J. Abbas, D. Wang, N. U. A. Baig, and R. Zhang. 2022. “From Cultural Tourism to Social Entrepreneurship: Role of Social Value Creation for Environmental Sustainability.” Frontiers in Psychology 13:925768. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.925768.

- Li, Y., A. Khalid, D. Wang, J. Abbas, and I. Al-Sulaiti. 2022. “Tax Avoidance Culture and Employees’ Behavior Affect Sustainable Business Performance: The Moderating Role of Corporate Social Responsibility.” Frontiers in Environmental Science 10:942527. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2022.964410.

- Liu, Y. 2018. “Research on the Urban-Rural Integration and Rural Revitalization in the New Era in China.” Acta Geographica Sinica 73:637–650. https://doi.org/10.11821/dlxb201804004.

- Liu, Q., X. Qu, D. Wang, J. Abbas, and R. Mubeen. 2021. “Product Market Competition and Firm Performance: Business Survival Through Innovation and Entrepreneurial Orientation Amid COVID-19 Financial Crisis.” Frontiers in Psychology 12:790923. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.790923.

- Liu, F., Q. Zhao, and Y. Yang. 2018. “An Approach to Assess the Value of Industrial Heritage Based on Dempster–Shafer Theory.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 32:210–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2018.01.011.

- Li, Z., D. Wang, J. Abbas, S. Hassan, and R. Mubeen. 2022. “Tourists’ Health Risk Threats Amid COVID-19 Era: Role of Technology Innovation, Transformation, and Recovery Implications for Sustainable Tourism.” Frontiers in Psychology 12:769175. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.769175.

- Long, H., L. Ma, Y. Zhang, and L. Qu. 2022. “Multifunctional Rural Development in China: Pattern, Process and Mechanism.” Habitat International 121:102530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2022.102530.

- Lynch, K. 1960. The Image of the City. Cambridge, USA: MIT Press. 91–117.

- Mamirkulova, G., J. Mi, S. Mubeen, R. Mahmood, A. Ziapour, and A. Ziapour. 2020. “New Silk Road Infrastructure Opportunities in Developing Tourism Environment for Residents Better Quality of Life.” Global Ecology and Conservation 24:e01194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01194.

- Mubeen, R., Terhemba Iorember, P., Raza S., and Mamirkulova, G. 2021. Exploring the impact of COVID-19 on tourism: transformational potential and implications for a sustainable recovery of the travel and leisure industry. Current Research in Behavioral Sciences 2:100033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crbeha.2021.100033.

- Neckar, L. 1989. “Developing Landscape Architecture for the Twentieth Century: The Career of Warren H. Manning.” Landscape Journal 8 (2): 79–91. https://doi.org/10.3368/lj.8.2.78.

- Oliveira, V., and V. Medeiros. 2016. “Morpho: Combining Morphological Measures.” Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 43 (5): 805–825. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265813515596529.

- Ozenda, P., and J.-L. Borel. 2000. “An Ecological Map of Europe: Why and How?” Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences - Series III - Sciences de la Vie 323 (11): 983–994. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0764-4469(00)01227-0.

- Peng, L., S. Liu, and L. Sun. 2016. “Spatial - Temporal Changes of Rurality Driven by Urbanization and Industrialization: A Case Study of the Three Gorges Reservoir Area in Chongqing, China.” Habitat International 51 (2): 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.10.021.

- Rapoport, A. 1997. Human Aspects of Urban Form: Towards a Man—Environment Approach to Urban Form and Design. New York: Pergamon.

- Sabaté-Bel, J. 2008. Projecting the Territory in Times of Uncertainty. Barcelona: Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya.

- Sauer, C. 1996. The Morphology of Landscape. Oxford: Blackwell Publisher Ltd.

- Shah, S. A. R., Q. Zhang, J. Abbas, H. Tang, and K. I. Al-Sulaiti. 2023. “Waste Management, Quality of Life and Natural Resources Utilization Matter for Renewable Electricity Generation: The Main and Moderate Role of Environmental Policy.” Utilities Policy 82:101584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2023.101584.

- Short, J. R. 1984. An Introduction to Urban Geography. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-17508-6_1.

- Su, Z. 2022. SheCun Zhi. Nanjing, China: Nanjing Publishing House.

- TICCIH. 2003. The Nizhny Tagil Charter for the Industrial Heritage. Accessed May 12, 2023 www.icomos.org/18thapril/2006/nizhny-tagil-charter-e.pdf.

- Tonnies, F. 1988. Community and Society (Gemeinschaft and Gesellschaft). New Jersey: Transaction Publishers.

- Torre, S. D. 2020. “A Coevolutionary Approach to the Reuse of Built Cultural Heritage.” The Architect:16–20 5.

- Tortora, A., D. Statuto, and P. Picuno. 2015. “Rural Landscape Planning Through Spatial Modelling and Image Processing of Historical Maps.” Land Use Policy 42 (1): 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.06.027.

- van der Vaart, J. H. P. 2005. “Towards a New Rural Landscape: Consequences of Non-Agricultural Re-Use of Redundant Farm Buildings in Friesland.” Landscape and Urban Planning 70 (1–2): 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2003.10.010.

- Wang, S. 2009. “The“harmony Between Man and nature” Theory and the Ancient Chinese Humans Settlement Building.” Journal of Northwest University 39 (5): 915–920. https://doi.org/10.16152/j.cnki.xdxbzr.2009.05.024.

- Wang, S., J. Abbas, K. I. Al-Sulati, and S. A. R. Shah. 2023. “The Impact of Economic Corridor and Tourism on Local Community’s Quality of Life Under One Belt One Road Context.” Evaluation Review 193841X (231182749). https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X231182749.

- Wang, Y., Q. Chun, X. Xiong, and T. Zhu. 2022. “Conservation and Adaptive Reuse of Modern Military Industrial Heritage: A Case Study on the Former Site of Jinling Arsenal in Nanjing, China.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 21 (4): 1193–1210. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2021.1941977.

- Wang, Z., Y. Wang, H. Guo, and Q. Zhang. 2022. “Unity of Heaven and Humanity: Mediating Role of the Relational-Interdependent Self in the Relationship Between Confucian Values and Holistic Thinking.” Frontiers in Psychology 13:958088. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.958088.

- Xie, Y., X. Meng, J. Cenci, and J. Zhang. 2022. “Spatial Pattern and Formation Mechanism of Rural Tourism Resources in China: Evidence from 1470 National Leisure Villages.” ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 11 (8): 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi11080455.

- Xiong, X. 2018. Architectural Graphic Type Ideas and Design Methods of J.N.L.Durand. Master, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xian.

- Xiong, X., and Y. Wang. 2023. “The Concept, Type Characteristics and Values of Rural Industrial Heritage: Based on the Investigation in the Southern Area of Jiangsu.” Industrial Construction. https://doi.org/10.13204/j.gyjzG22060901.

- Xiong, X., Y. Wang, C. Ma, and Y. Chi. 2023. “Ensuring the Authenticity of the Conservation and Reuse of Modern Industrial Heritage Architecture: A Case Study of the Large Machine Factory, China.” Buildings 13 (2): 534. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13020534.

- Xiong, X., Y. Wang, M. Pesoa-Marcilla, and J. Sabaté-Bel. 2022. “Dependence on Mountains and Water: Local Characteristics and Regeneration Patterns of Rural Industrial Heritage in China.” Land 11 (8): 1341. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11081341.

- Xiong, Y., J. Zhang, Y. Yan, S. Sun, X. Xu, and E. Higueras. 2022. “Effect of the Spatial Form of Jiangnan Traditional Villages on Microclimate and Human Comfort.” Sustainable Cities and Society 87:104136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2022.104136.

- Xu, S., and L. Chen. 2020. “Knowing the End from the Beginning: The Traceability of Layer Thoughts in Urban Design.” City Planning Review 44 (4): 62–72. https://doi.org/10.11819/cpr20200409a.

- Yu, Q. 2012. Historical Changes of Industrialization in Rural China. Dalian, China: Dongbei University of Finance & Economics Press.

- Yu, S., A. Negulescu, O. H. Draghici, N. U. Ain, and N. U. Ain. 2022. “Social Media Application as a New Paradigm for Business Communication: The Role of COVID-19 Knowledge, Social Distancing, and Preventive Attitudes.” Frontiers in Psychology 13:903082. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.903082.

- Yu, B., Lu, Y., Zeng, J., and Zhu, Y. 2017. “Progress and Prospect on Rural Living Space.” SCIENTIA GEOGRAPHICA SINICA 37 (3): 375–385. https://doi.org/10.13249/j.cnki.sgs.2017.03.007

- Zhan, Z., J. Cenci, and J. Zhang. 2022. “Frontier of Rural Revitalization in China: A Spatial Analysis of National Rural Tourist Towns.” Land 11 (6): 812. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11060812.

- Zhang, J. 2019. “Urban Renewal and Urban Weaving in an Era of Stock Properties.” Architectural Journal 7:1–5 .

- Zhang, J., J. Cenci, V. Becue, S. Koutra, and C. Liao. 2022. “Stewardship of Industrial Heritage Protection in Typical Western European and Chinese Regions: Values and Dilemmas.” Land 11 (6): 772. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11060772.

- Zhang, Y., Q. Min, C. Zhang, L. He, S. Zhang, L. Yang, M. Tian, et al. 2017. “Traditional Culture as an Important Power for Maintaining Agricultural Landscapes in Cultural Heritage Sites: A Case Study of the Hani Terraces.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 25:170–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2016.12.002.

- Zhang, C., and J. Yang. 2022. “Construction and Negotiation: Reflections on Relationship Between Cultural Heritage and Tourism.” Tourism Tribune 37 (11): 75–84. https://doi.org/10.19765/j.cnki.1002-5006.2022.11.009.

- Zheng, J., Bai X., Wu Z., Zhang S., Zhang T., and Wang H. 2022. “Research on the Spatial Behavior Conflict in Suburban Village Communities Based on GPS Tracking and Cognitive Mapping.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 21 (6): 2605–2620. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2021.1971680.