ABSTRACT

Fear of crime is one of the most significant factors affecting citizen’s quality of life. It isparticularly necessary to control the environmental factors that cause fear of crime in the neighborhood, as that is more worrisome. This study aimed to investigate women’s fear of crime in public streets in their neighborhoods and to identify the environmental factors that affect their fear of crime using a questionnaire and an eye-tracking experiment, respectively. Thirty participants watched four low-rise residential streets in Seoul and responded to a survey about their fear of crime. Through a multiple regression analysis, Factors such as “maintenance”, “pilotis”, “building entrance”, and “emergency bell” were found to largely influence fear of crime. This study contributes to the literature by identifying specific physical environment factors in parallel with eye tracking experiments, and our results have implications for future street design aimed at reducing the fear of crime.

1. Introduction

Fear of crime has a negative impact on citizen’s daily life as well as their quality of life. It constrains everyday behavior and leads individuals to limit the ambit of their life by avoiding certain routes or places (Blöbaum and Hunecke Citation2005; Keane Citation1998; Park Citation2008; Solymosi et al. Citation2021) and limiting taking walks (Ceccato and Bamzar Citation2016; Foster et al. Citation2016; Foster, Giles-Corti, and Knuiman Citation2014), ultimately lowering their physical well-being. Additionally, fear of crime lowers mental well-being by reducing social participation (Piscitelli and Perrella Citation2017; Skogan Citation1986; Stafford, Chandola, and Marmot Citation2007) and by generating chronic strain (Adams and Serpe Citation2000; Whitley and Prince Citation2005). Therefore, it is essential for urban administrations to create a safe environment by reducing daily fear of crime, ensure social safety, and improve citizens’ quality of life. This study aims to identify the physical environmental factors that affect fear of crime to suggest ways to make the neighborhood streets safer for daily walks. To this end, we use a questionnaire to investigate women’s fear of crime in the public streets in their neighborhoods and identify the environmental factors that affect their fear of crime through an eye-tracking experiment.

1.1. Types of fear of crime in daily life

To create safer environments, a clear understanding of fear of crime is important. Fear of crime is based on emotional responses such as fear, worry, and anxiety about crime and crime-related situations and symbols, regardless of actual crime rates or risks (Felson and And Citation2010; Ferraro Citation1995; Warr Citation1984). Fear of crime began to be recognized as an important social problem to be addressed when the United States’ National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders discussed it in the 1960s as an independent problem unrelated to the occurrence of crime (Warr Citation2000). Since then, Fear of crime has been a popular research topic by scholars of sociology, psychology, and environmental criminology, though from different perspectives of fear of crime and its interpretation, as illustrated in .

First, it is generally assumed in psychology and sociology that fear of crime is a continuous emotion, that is, a personal state of mind, and the cause of fear is frequently interpreted in association with demographic conditions and social background. The main representative models from this perspective comprise: the victimization model, which analyzes the relationship between direct and indirect victim experiences and fears (Balkin Citation1979; Garofalo Citation1979; May, Rader, and Goodrum Citation2010); the vulnerability model, which examines the effects of individual vulnerability and fear of crime on overcoming crime damage (Jackson Citation2009; Pantazis Citation2000; Skogan and Maxfield Citation1981); and the social integration model, which analyzes aspects of social integration, such as community bonds, as factors that suppress fear of crime (Adams and Serpe; Kanan and Pruitt Citation2002; Lee Citation1983). Although this approach may be appropriate from a macro perspective, it is not possible to identify all the causes of fear that people experience at every moment in their daily lives, because fear of crime is affected by the individual’s state of mind and the situational fear experienced temporarily in certain environmental contexts and situations (Fattah and Sacco Citation2012; Koskela and Pain Citation2000; Solymosi et al. Citation2021). Therefore, studying fear as an individual factor has limitations in capturing the place-based situational fear that users experience in a specific environmental context and situation.

In contrast to the fields of psychology and sociology, environmental criminology focuses more on empirical situational fears based on the relationship between crime and the physical environment. The basic theoretical concept was introduced by Jane Jacobs (Citation1961) when she described the interaction between residents and their physical environment and the various connections between the residential environment and crime in her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Subsequently, criminologist C. Ray Jeffery (Citation1971) established a theoretical relationship between crime and the urban environment that criminologists then began to test in earnest. Since then, fear of crime research has expanded to include defensive space theory, based on the concept of territoriality (Newman Citation1973), and broken window theory, focusing on situational and environmental disorder (Kelling and Wilson Citation1982). Environmental criminology encompasses a range of theories concerning the relationship between crime and the physical environment. The most widely adopted theory is crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED), based on earlier works of Jeffery (Citation1971). CPTED entails a comprehensive crime prevention strategy intended to eliminate or minimize those aspects of the physical environment that render individuals vulnerable to crime, ultimately reducing the probability of crime and residents’ fear of crime and improving their quality of life (Brantingham and Brantingham Citation1998; Crowe and Way Citation2008; Jeffery Citation1971).

These theories are grounded in the belief that designing a proper environment will serve to prevent crime. However, this approach has the limitation of not addressing fear of crime as a primary problem; instead, it deals with the situational fear of crime as a secondary goal when seeking to create a crime-prevention environment. In recent years, as researchers have demonstrated that places where real crime occurs are distinct from the areas where people feel fear, researchers have focused on fear of crime as an independent issue influenced by the environment (e.g., Ceccato Citation2016; Grohe, Devalve, and Quinn Citation2012; Lewis and Maxfield Citation1980; Solymosi, Bowers, and Fujiyama Citation2015).

When dealing with the social issue of fear of crime in research, it is appropriate to explore situational fear in studies based on environmental criminology. It is possible to observe and analyze the environment associated with fear and suggest appropriate measures for improving the environment. However, it is also important to note that fear of crime impacts our lives not just through personal or situational factors; for example, individuals with high fear levels may pay more attention to certain environmental factors when they perceive their surroundings, while some other environmental factors may elicit situational fear. Therefore, this study examines the environmental factors related to fear of crime as individual and situational factors.

1.2. Assessing users’ environmental perception

To create a secure environment where people feel safe, it is necessary to identify how people perceive the environment and then accurately identify which physical environmental factors are related to fear. Many previous studies have used surveys to investigate the relationship between environment and fear by asking people about the fear they felt in a particular space after presenting or experiencing a specific situation. However, it is difficult for humans to retain the same memory perfectly while facing an environment, visually perceiving it, completing the recognition and cognitive processes, and responding (Alvarez and Cavanagh Citation2004; Baddeley Citation2000, Cowan Citation2012; Luck and Vogel Citation1997). Moreover, the unconscious mind can distort perceptual information. Participants may be unable to answer because they do not notice the factors that unconsciously affect or generate their fears (Banaji and Hardin Citation1996; Bargh and Chartrand Citation1999; Nisbett and Wilson Citation1977; Wilson and Brekke Citation1994). Additionally, participants may unconsciously create factors that affect fear using prior knowledge (Hatfield Citation2002; Nickerson Citation1998; Pylyshyn Citation1999). Finally, there may be a limitation in that the opinions of passive respondents are less fully reflected, compared to those of enthusiastic respondents (Tourangeau, Rips, and Rasinski Citation2000).

It is necessary to compensate for these limitations by collecting quantitative information to measure participants’ environmental perceptions directly, which we felt could be achieved through an eye-tracking experiment and a questionnaire. Eye-tracking allows for the identification of the respondent’s environmental recognition process, helping to identify major physical environmental factors by tracking the respondent’s gaze to gather quantitative data (Blascheck et al. Citation2017; Duchowski Citation2017; Johansen and Hansen Citation2006; Kooiker et al. Citation2016; Noland et al. Citation2017; Rayner Citation2009). Research using the eye tracking method is based on an understanding of the human visual perception and recognition process. Humans use information perceived through the sensory system to recognize something, especially visual information, that significantly impacts cognition (Eriksen and Schultz Citation1979; Hendee and Wells Citation1997; Marr Citation1977). To effectively conduct research using the eye-tracking method, a thorough understanding of human eye movement is essential. Human eyes fixate on a specific area to perceive something and then take a quick, indeed instantaneous leap to the next area, a process called saccading (Henderson Citation2003; Irwin and Zelinsky Citation2002; Wolfe Citation1998). Recognizing and processing information during these two phases occurs at the moment of focus fixation (Duchowski Citation2017; Irwin Citation1991; Just and Carpenter Citation1976; Kowler et al. Citation1995).

Humans perceive their environment similarly (Imani and Tabaeian Citation2012; Pasqualotto and Proulx Citation2012). Spatial users recognize the surrounding environment by acquiring visual information in the area where visual attention occurs. The eye-tracking method can be used to measure the specific area where people place visual attention (including data on how often or for how long they look) and where they take a cursory glance, yielding quantifiable data on their gaze. Thus, meaningful areas that affect environmental perception can be identified without memory distortion. The field of environmental psychology has started to employ the eye-tracking method to understand humans’ environmental awareness using quantitative and objective data. While previous research has yielded valuable findings, further exploration and study is needed, especially of fear of crime.

Therefore, this study aimed to identify the physical factors influencing the environmental perception of spatial users by analyzing the results of eye-tracking experiments and the responses to two questionnaires (on fear of crime as an individual state and on situational fear) to determine the physical environmental factors contributing to the spatial users’ fear of crime. It fills a crucial gap in the literature on the creation of a safe environment by (1) exploring the relationship between the physical environment and fear of crime, which is the emotional factor, (2) examining both individual and situational fear of crime, and (3) using a quantitative eye-tracking method to identify the environmental cues that directly impact fear of crime.

1.3. Research questions

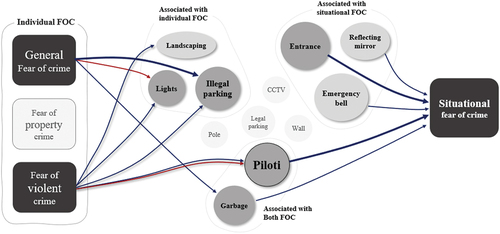

We collected data using three methods (). The first is a questionnaire exploring the daily fear of crime experienced by participants. The second was eye-tracking of the perceived environmental factors on which participants focused to determine environmental awareness. Finally, situational fear of crime was investigated based on the environmental context in the presented situation. Based on the data, we conducted multiple regression analyses to answer two research questions.

Question 1 Path A:

Which environmental factors receive the most attention depending on the intensity of the daily fear of crime experienced by an individual?

If we can identify the important physical environmental factors that people with a high level of fear of crime (as an individual state) consider, these factors could be employed when creating or improving a safe residential environment, in turn alleviating the fear of crime in people who are usually highly afraid of crime.

Question 2 Path B:

How does visual attention to specific physical environmental factors impact situational FOC?

Although FOC is usually considered a personal state factor, it can be a situational event depending on the surrounding environment. Regardless of the daily fear of crime (tension), some environmental factors can induce fear in certain situations. Therefore, if the detailed environmental factors affecting situational fear of crime are identified and addressed, the intensity of the fear felt in a particular space can be reduced.

Addressing the research questions allows us to identifies the environmental factors associated with fear of crime and gain insights for the creation of a safe residential environment.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

In this study, 30 single female-member households participated. Next, we explain the rationale behind the selection of such households as participants, reasons for choosing the sample size, recruitment process, and criteria governing the data employed for analyses.

2.1.1. Fear of crime among single female households in Korea

Women generally feel higher levels of FOC than men (Fox, Nobles, and Piquero Citation2009; Haynie Citation1998; Pain Citation1991; Reid and Konrad Citation2004; Schafer, Huebner, and Bynum Citation2006; Warr Citation1984), a fact that has been observed in the study’s location, South Korea, as well (Lee, Park, and Jung Citation2016; Brown Citation2016; Byun and Ha Citation2020; Kang, Ha, and Byun Citation2020; Lee and Cho Citation2018). We focused on the problem of high FOC among single female households in South Korea, where the number of one-person households has rapidly increased recently. In 2015, individuals living alone became the most common type of household (Korea National Statistical Office [KNSO] Citation2015); these accounted for 33.4% of total households in 2021 and are expected to increase to over 40% by 2050 (KNSO Citation2022). We specifically studied single women living alone, who tend to experience a significantly higher fear of crime than men.

According to a survey conducted by the Seoul Metropolitan Government, women who reported criminal safety as their top concern in living alone had a 14-times higher response rate, with 39.8% of respondents considering women’s safety the most urgent policy issue (Jang and Kim Citation2016). Similar results have been found by other studies. For instance, Hwang, Kang, and Park (Citation2013) cite that 77% of female participants reported fear of crimes such as sexual violence as the most serious difficulty in living alone. The fear of crime experienced by such women has a significant negative impact on their quality of life, going beyond mere inconvenience. In their efforts to prevent crimes, they often have to take inconvenient measures in their daily lives, such as ordering packages using men’s names, using voice modulation apps, keeping men’s shoes on the porch, or hiring private security services (Han Citation2019, Citation2018; Jin Citation2019; Kim Citation2018, Citation2021; Lee and Wu Citation2021). The fear of crime also results in less stable living situations for these women, who may bear high housing costs to secure a safe living environment, or live in cramped houses if they lack adequate finances (Jo and Kim Citation2019; Lim Citation2020). As the family paradigm and lifestyle of modern societies change, the number of single female households, who are particularly vulnerable to fear of crime, is expected to increase, as would individual and social problems caused by high fear of crime. We thus identified single-female households as the group most in need of urgent relief from fear of crime, and aimed to develop an effective strategy for reducing fear of crime among single-female households.

2.1.2. Sample size for the eye tracking experiment

We referred to Lee, Ha, and Byun’s (Citation2022) research to determine an appropriate number of research participants as this study had conducted a review of prior eye-tracking researches in the fields of architecture and spatial analysis, comparing the participant sizes across these studies. Of 59 research studies, 37 (66%) had conducted experiments with participant groups ranging from 21 to 40 individuals. While this number of participants may seem relatively small when compared to survey-based research, it is indicative of the nature of the extensive data obtained through eye-tracking experiments, which differ significantly from survey-based data. Therefore, in line with the most commonly adopted practice, we opted to use a sample size of 30 participants.

2.1.3. Recruitment process and criteria for data collection

In this study, participants were recruited through postings on local community boards and university campus bulletin boards. The research specifically targeted women aged 19–39 who were living alone and expressed an interest in participating in the study. However, certain survey items in this study contained questions related to crime and crime experiences, which were anticipated to evoke discomfort and potentially have a negative emotional impact on participants. Consequently, individuals who had experienced criminal victimization in their residential areas or surrounding spaces within the past three years were excluded from the participant recruitment process according to the Institutional Research Bureau guidelines.

A total of 30 datasets were collected through recruiting, and the collected data assessed with validity. The validity of eye-tracking data refers to the proportion of usable data obtained after excluding data rendered unusable due to factors such as participants blinking or deviating their gaze from the screen during the study. Following this assessment, one participant’s data, which exhibited a data validity rate of 77%, were excluded from the subsequent analysis. Finally, data from 29 participants were utilized for the analysis, with an average data validity rate of 92%. The average age of the participants was 30.2 years (SD = 3.08), with students representing the largest occupational category at 51.7%.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Questionnaire 1: fear of crime as state—individual factor

Questionnaire 1, which examines people’s daily fear of crime, comprised questions pertaining to “General fear of crime” and “Fear of specific crime.” presents the 12 questions included in this questionnaire. The general fear of crime section had questions concerning fear according to space (in a house or street at night) and according to the victim (“myself or people around me”). The questionnaire to measure fear of specific crimes sought responses on eight specific crime types, which were partially revised based on the types most commonly found in South Korean official statistics (property damage, burglary, robbery, fraud, sexual crime, assault, stalking, and home invasion). First, “fraud” was omitted, as it occurs regardless of location. Additionally, in light of the shadow of sexual assault hypothesis, which suggests that even mild forms of sexual harassment commonly experienced by women can have a shadow effect on their fear of other crimes (Choi, Yim, and Lee Citation2020; Ferraro Citation1996; Hilinski Citation2009; Hirtenlehner and Farrall Citation2014; Lane, Gover, and Dahod Citation2009; May Citation2001; Mellgren and Ivert Citation2019; Warr Citation1984), “sexual crimes” were divided into two categories: “sexual harassment” and “sexual violence.”

Table 1. Measurement of fear of crime (FOC) as an individual factor (Questionnaire 1).

2.2.2. Questionnaire 2: fear of crime as an episode—situational factor

Questionnaire 2 was designed to assess the situational fear of crime that participants experienced in a particular environment. They completed the questionnaire after viewing videos corresponding to specific situations. Fear of crime and crime risk perception were investigated together, as demonstrated in , to avoid participant confusion between fear of crime as an emotional factor and crime risk perception as the cognitive process (Ferraro and LaGrange Citation2017; Rountree and Land Citation1996). Only the situational fear of crime data obtained in this process were used in the analysis.

Table 2. Measurement of situational fear of crime (Questionnaire 2).

2.3. Study area

To establish the study area, we examined national statistics concerning young single women’s primary residential types, their levels of fear of crime based on residential types, and the perceived locations of potential criminal incidents among young women living alone. According to the 2016 Seoul Single-Person Household Survey, approximately 75% of young women living alone reside in multi-family housing, non-residential dwellings, or other housing types, rather than apartments. Among these residential options, those living in multi-family housing reported the highest levels of fear of crime. The locations identified by young women in one-person households as having the highest potential for criminal incidents were public spaces in their residential vicinity, such as streets (Jang and Kim Citation2016; Park Citation2018). There was a noticeable inclination among them to exhibit greater fear of crime in areas where the residences were densely clustered compared to areas with a commercial presence. Therefore, this study delimited its research scope to focus on low-rise residential areas characterized by a high prevalence of multi-family housing, a residential type prevalent among single-female households and associated with high fear of crime. We selected narrow streets with no commercial facilities but densely populated with residential buildings as the specific research environment.

The specific study area was determined through the following procedure. First, districts with a high prevalence of young single women in single-person households were identified. According to the 2015 Population Census conducted by Statistics Korea, among the 25 districts in Seoul, the districts of Gwanak-gu, Gangnam-gu, and Mapo-gu were found to have the highest concentration of young single-women households. The proportion of young single women in one-person households accounted for approximately 30% of the total households in each district. From among the three, this study selected Mapo-gu as the research target area as it exhibited the highest night-time walking risk level in urban risk statistics for Seoul. Second, within the selected Mapo-gu district, the study employed a combination of online geographic information and field visit to identify streets that met the criteria for target area selection. This study established criteria for selecting experimental target streets to control for fixed environmental factors and to avoid the results being based on a single street. The selection criteria include CPTED factors, the shape and width of the street, and the use and height of surrounding buildings, as presented in . In total, four streets were selected as research targets under these criteria; detailed information about each of the selected target areas follows.

Table 3. Criteria for selecting streets.

2.3.1. Physical conditions criteria of the selected streets

First, we controlled the height and use of buildings located around the street. As the study focused on the residential environment, we considered residential areas without commercial activities on the lower floors. According to the South Korean legal standards for Type 1 general residential areas, where low-rise multi-family housing is concentrated, the height of the surrounding buildings is limited to a maximum of five floors. Previous research has shown that the shape and width of a street can influence the fear levels that individuals experience. To control the impact of the street shape on fear of crime, we opted to adopt a street structure consisting of a 6-meter-wide straight path. The street was 80 meters in length to ensure a playback time of 40 seconds, which was determined to be appropriate through a pilot experiment based on a walking speed of 2 m/s. To ensure that participants recognized the filmed section as a single street, no intersections were included in the filming. Maps and related information concerning the selected four target areas are presented in .

Table 4. Information on four selected streets.

2.3.2. Controlled environmental factors that may affect fear of crime

To avoid wildly different results for the four streets due to their respective environmental factors, we controlled for major environmental factors that could significantly impact fear of crime. First, we ensured that the lighting on the streets were as similar as possible by ensuring a unified operation rate of 100 of the streetlights. Second, the number of public safety poles with CCTV and emergency bells was limited to one. We selected streets where the public safety pole was placed at the center of the street to prevent its appearance at the beginning or end of the video film. Third, general low-rise residential streets used by cars and pedestrians were chosen, without distinguishing between sidewalks and roads. Finally, we selected a location on the target street with no rest areas such as parks, playgrounds, or benches.

2.4. Stimulus materials

The stimulus materials used in the experiment were carefully selected to accurately reflect the continuous act of “walking” on a street. Accordingly, video was chosen as the experimental stimulus over still photographs. When filming the video, great care was taken to avoid including human factors, as the presence of passersby could elicit unwanted attention and influence the participants’ fear of crime, hindering accurate measurements and analysis. The recording included no audio to prevent extraneous effects on participants’ Fear of crime and environmental perception.

The experimental stimuli were filmed using a SONY HDR-AS300 device equipped with a ZEISS® Tessar lens, which minimizes peripheral distortion during wide-angle recording. It has an optical hand-shaking correction function. The video was recorded at a focal length of 23 mm, resulting in 8.18 million pixels (F2.8) and 60 frames per second. To reflect the average height and eye level for women, the camera was set 1.5 meters from the ground. The resulting video is 40 seconds in length, and presents the captured image of the video (midpoint: 20 seconds) is presented in .

Table 5. Images illustrating the experimental stimuli video (midpoint of the video).

2.4.1. Setting the area of interest

In this study, a dynamic area of interest (AOI) was established in the video to assess the visual attention toward specific physical environmental factors. A dynamic AOI is suitable for video as it changes in position and size based on the motion of the specified factor. This study determined the target factors to set AOI by collecting physical environmental factors mainly considered for street crime safety. To this end, South Korea’s Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) guidelines (e.g., Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport Citation2013; National Police Agency Citation2005; Seoul Metropolitan Government Citation2013) were consulted. Abandoned garbage and illegally parked vehicles, which are considered major physical factors in the disorder model and Broken Window Theory, were also included in the AOI setting.

Consequently, a dynamic AOI was established for the items (see that correspond to surveillance (building entrance, lighting, reflective mirror, CCTV, and emergency bell), concealment space (wall, landscaping, pilotis, and utility pole), and maintenance (parked vehicle and garbage). An example image of a video with set AOIs is presented in . To analyze the visual attention toward each environmental factor, the count and total duration of focal fixation within the AOI were used. An example image is presented in for the visualization of the fixation data being recorded on the set AOIs.

Table 6. Criteria for setting AOI.

2.5. Procedure and instrument

The data for this study were collected by administering two questionnaires and an eye-tracking experiment following the procedure depicted in .

(1) Questionnaire 1 was administered before the video viewing to assess the respondents’ general fear and fear of crimes, which are individual factors. (2) After completing Questionnaire 1, participants watched a video as their eye movements were tracked. Before the video presentation, participants were instructed to imagine that the depicted street was close to their residence and to identify any factors that would evoke FOC. This top-down approach was used to gather data aligned with the research objectives (Castelhano, Mack, and Henderson Citation2009, Glaholt, Wu, and Reingold Citation2010; Malcolm and Henderson Citation2010; Mills et al. Citation2011). (3) After watching the video, the participants completed Questionnaire 2 to assess their situational fear.

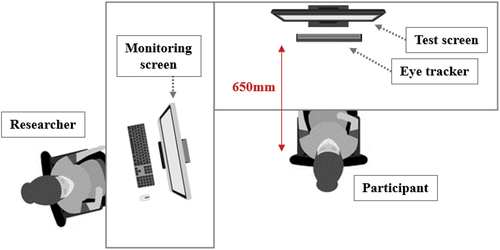

Steps (2) and (3) were performed eight times, with each of the four streets being evaluated during day and night. The videos were played in a random order to minimize potential biases. The experiment used was Gazepoint’s GP3 model (60 Hz, gaze angle accuracy of 0.5–1 degree single accuracy), which was positioned at the base of the monitor at a distance of approximately 650 mm from the participants, as recommended by Gazepoint. The layout of the experiment is illustrated in . Prior to each viewing, we conducted calibration by adjusting the focus at five points and making corrections at nine points. “Gaze point analysis” software was used for the data collection, video presentation, and calibration.

2.6. Data analysis

To better understand the relationship between physical environmental factors and fear of crime, we conducted the analysis following the sequences illustrated in . Before performing the regression analysis (Paths A and B), we calculated the descriptive statistics of the dependent and independent variables, presented below as Questionnaire 1 (response to the basic survey on individual’s fear of crime) and Questionnaire 2 (evaluation of fear felt after watching the video), and the eye-tracking experiment results (visual attention for each factor). We statistically analyzed the data with IBM SPSS.

2.6.1. Questionnaire 1: fear of crime as state – individual factor

The Cronbach’s alpha for the 12 survey items used to measure an individual’s fear of crime, was 0.751, indicating high internal consistency. Before the specific analysis, this study simplified the factors by categorizing the eight specific fear items into two groups: violent crime (assault, sexual harassment, sexual assault, house invasion, and stalking) and property crime (burglary, robbery, and property damage), based on the purpose of the crime. This aligns with previous studies (e.g., Han et al. Citation2018; Harries Citation2006; Kelly Citation2000; Moore and Recker Citation2016) that suggested the need to analyze FOC separately for property crimes and violent crimes. The Cronbach’s alpha values for each group were 0.754 (property crime) and 0.896 (violent crime), indicating high reliability. The average value for each group was ranked as follows: General fear of crime (5.96), fear of violent crime (5), and fear of property crime (3.77). These average values were used as independent variables in the subsequent regression analysis.

The descriptive statistical analysis found that the participants reported higher levels of general fear of crime than fear of specific crimes, and among fear of specific crimes, they tended to be more afraid of violent crimes than property crimes. As presented in , the level of general fear of crime reported in streets (7.24) was significantly higher than in residences (4.79), indicating that respondents were most afraid of being in the streets. This confirms the appropriateness of selecting the street as the study area.

Table 7. Results of the questionnaire 1 (n = 29).

The analysis also revealed that fears of property crimes were ranked in the order of property damage, burglary, and robbery, while the fears of violent crimes were ranked in the order of home invasion, sexual harassment, sexual assault, stalking, and assault. Among the violent crimes, home invasion (5.03), sexual harassment (5.17), and sexual assault (5.07) showed higher levels of fear than property damage (5.03; the highest fear among property crimes). In contrast, assault (3.69) among the violent crimes showed a lower level of fear than robbery (3.72; the lowest fear among property crimes). Thus, the participants of the survey, all female, expressed higher levels of fear toward sexual crimes or crimes that may include implicit sexual threats than toward simple violent crimes.

2.6.2. Questionnaire 2: FOC as episode – situational factor

Questionnaire 2 elicited both situational fear of crime and perceptions of criminal risk. However, only situational fear was analyzed in this study, which investigated criminal risk perception to clearly distinguish situational fear. presents the results of the evaluation of the situational fear of crime felt on the street after watching each video. Participants generally reported a higher level of fear at night than during the daytime.

Table 8. Evaluation of the situational fear of crime felt on each street (Questionnaire 2; n = 29).

2.6.3. Visual attention (fixation) data from eye-tracking

In this study, we used eye-tracking technology to collect visual attention data, specifically fixation duration (the length of time the focal point remained on a factor) and fixation counts (the number of times the gaze was fixed), in predetermined areas of interest (AOI). These AOIs were selected to understand environmental factors that may be related to fear of crime. Before discussing the regression analysis, we present the overall fixation counts and duration for each factor in to indicate the basic visual attention given to each factor.

Table 9. Mean duration and frequency for each environmental factor (n = 29).

First, regarding the durational data, the environmental factors for which the longest observation time was recorded were pilotis (1.33), illegal parking (0.88), and landscaping (0.73), while lighting (0.05) was observed for the shortest time. At night, the factors that were observed the longest included garbage (1.73), pilotis (1.03), and illegal parking (0.60), while CCTV (0.19) showed the shortest duration. Participants generally observed most factors longer during the day, but lighting, garbage, and reflective mirrors were observed longer at night, presumably due to the difficulty of identifying objects such as garbage and reflections in the mirror in the dark at night.

Second, the environmental factors that were observed most frequently during the day were garbage (4.1), illegal parking (2.89), and landscaping (2.58), whereas lighting (0.16) had the lowest fixation counts. At night, pilotis (3.75), illegal parking (2.8), and utility poles (2.17) were viewed more frequently and CCTV (1.02) the least frequently. Although the participants tended to observe most factors more often in nighttime situations, the fixation frequencies for CCTV, legal parking, and garbage were lower at night. Notably, at night, the participants observed garbage for longer durations in fewer counts, indicating that participants focused on garbage for longer periods but looked at it fairly rarely. This suggests that fixation counts and duration are meaningful indicators for analyzing visual attention data.

3. Results

3.1. Step 1 (path A): effects of fear of crime as an individual state on attention to physical environmental factors

In Step 1, the physical environmental factors, or those that people with higher levels of fear of crime pay more attention to when walking on the street, were identified through multiple regression analyses using stepwise selection. Individual factors such as general fear of crime, fear of violence, and property crime were drawn from the results of Questionnaire 1 and set as the independent variable. The dependent variable was visual attention as measured by duration and fixation counts for major physical environmental factors during both day and night. This paper describes only the influencing factors that showed meaningful results.

3.1.1. Daytime

During the day, fear of crime as an individual factor was found to have no significant impact on the duration of observation time of specific environmental factors. However, it affected the frequency of visual attention toward some environmental factors. The findings, presented in , are summarized as follows. First, participants with higher levels of general FOC spent less time observing lighting (β = −.466 [p < 0.1]). The model summary for this analysis accounted for 18.8% of the variance. Second, fear of violent crime positively affected the frequency of fixations on the pilotis, with β = 0.376 (p < 0.01). This suggests that individuals who fear violent crime daily tend to watch the pilotis more frequently. The model results accounted for 11.8% of the variance, as illustrated in .

Table 10. Environmental factors affected by individual fear of crime during the day (n = 29).

3.1.2. Night time

Significant differences were found in the duration and frequency of attention directed toward certain environmental factors at night. Emergency bells and illegally parked vehicles were observed for longer periods, while the frequency of attention toward landscaping, pilotis, illegally parked vehicles, and garbage differed significantly. A summary of the models for each environmental factor that showed meaningful results is presented in .

Table 11. Environmental factors affected by individual fear of crime at night (n = 29).

3.1.2.1. Influence of individual fear of crime on the “focal duration” of environmental factors

Individual fear of crime affected the time spent watching emergency bells and illegally parked vehicles on the streets at night, with higher levels of the personal fear of violent crime associated with shorter observation times (β = −0.4). The multiple regression model explained 12.9% of the variance, with an F-value of 5.138 (p = 0.032) and a Durbin-Watson statistic of 2.098. Additionally, the analysis revealed that general FOC significantly affected the time spent observing illegally parked vehicles (β = 0.629). The analysis yielded an F-value of 7.787 (p = 0.01) with a Durbin-Watson statistic of 1.659, and the model explained 19.5% of the variance.

3.1.2.2. Influence of individual fear of crime on the “fixation counts” of environmental factors

Individual fears affected the frequency of observing certain street features, including landscaping, pilotis, illegally parked vehicles, and garbage. Specifically, the fear of violent crime positively affected the frequency of fixation counts of landscaping (β = 0.405) and pilotis (β = 0.423), indicating that individuals with higher levels of fear of violent crime tend to observe landscapes and pilotis more frequently. In the analysis with landscaping as the dependent variable, the F-value was 5.292 (p = 0.029), the Durbin-Watson statistic was 1.707, and the model accounted for 13.3% of the variance. In the model with pilotis as the dependent variable, the F-value was 5.886 (p = 0.022), the Durbin-Watson statistic was 1.473, and the model explained 14.9% of the variance.

Additionally, individuals’ general fear of crime positively affects the frequency of observing illegally parked vehicles, with a beta value of 0.895 (p = 0.001), while the fear of violent crime had a negative effect with a beta value of − 0.593 (p = 0.025). This suggests that individuals with higher levels of general fear of crime tend to observe illegally parked vehicles more frequently, but those with a higher fear of violent crime do so less frequently. The F-value of the model was 7.369, the Durbin-Watson statistic was 1.497, and the model explained 31.3% of the variance.

Finally, the general fear of crime of an individual had a positive effect on the frequency of watching the garbage, with a beta value of 0.516, that is, those with higher fear of crime levels are more likely to observe garbage more frequently. The F-value of the analysis was 5.292 (p = 0.004), the Durbin-Watson statistic was 1.707, and the model explained 13.3% of the variance.

3.2. Step 2 (path B): analysis of the effect of environmental factors on situational fear of crime

In Step 2, we examine the physical environmental factors in streets that impact the situational FOC experienced by pedestrians in a specific environment. We conducted multiple stepwise regression analyses using the attention level for each AOI (fixation duration and fixation counts) as independent variables and situational fear as the dependent variable. The regression was carried out separately for daytime and night time situations in the streets. During the day, no physical environmental factors significantly affected situational fear of crime. However, as shown in , various physical environmental factors were found to influence situational fear of crime at night.

Table 12. Environmental factors affecting situational fear of crime at night (n = 29).

The first analysis demonstrated that longer fixation durations on pilotis (β = 0.718), garbage (β = 0.376), reflective mirrors (β = 0.317), and emergency bells (β = 0.310) were associated with higher levels of situational fear of crime, while longer observations of entrances (β = −0.328) were related to lower levels of situational fear of crime. The model accounted for 70.4% of the variance in situational fear. In the second analysis, a higher frequency of fixations on pilotis (β = 0.629) was linked to elevated levels of situational fear of crime in a given situation, while a higher fixation frequency on the entrance (β = 0.469) was associated with lower levels of fear. This model explained 36% of the variance in situational fear of crime.

4. Discussion

This study identifies the physical environmental factors associated with an individual’s fear of crime or situational fear of crime. We analyzed participants’ eye movements as they watched videos, and experiments and questionnaires were administered separately for day and night videos. In , we present the results for the major environmental factors that have a significant relationship with fear of crime. The red lines indicate the results for daytime, the blue lines those for night time, and the thickness of the relationship line indicates the frequency of influence. As both positive and negative effects were significant for the relationship between environmental factors and fear of crime, we did not emphasize them separately.

Our findings demonstrate that on the streets, during the day, individuals’ general fear of crime affected their visual attention to lighting, while fear of violent crime affected their visual attention to pilotis. However, this did not lead to an increase in situational fear of crime. At night, the general fear of crime that individuals experience affects their visual attention to illegal parking and garbage, with garbage again affecting situational fear. Environmental factors that affected individuals’ fear of violent crime included emergency bells, landscaping, pilotis, and illegal parking, with emergency bells and pilotis significantly affecting situational fear of crime. Entrances and reflective mirrors also had a significant effect on situational fear of crime.

In summary, our results indicate that the most important factors associated with fear of crime are pilotis, entrances, emergency bells, and the overall maintenance of the street environment play a critical role in enhancing the sense of safety in low-rise residential areas. The following are the improvement measures recommended for each of these factors.

Pilotis: These were found to be a significant environmental factor associated with fear of crime among participants at both daytime and nighttime. The piloti space, originally proposed by Le Corbusier (Vogt and Corbusier Citation2000), has been localized in South Korea to alleviate parking difficulties in low-rise residential areas. However, on the first floors of multi-family houses, this space is mostly used for parking rather than as an activity space for residents and sometimes even serves as the entrance to the building between parked vehicles. This spatial design facilitates concealment in a piloti, which increases fear of crime and negatively impacts residents’ mental health in the long term. Furthermore, pilotis are a fixed building environment that would be difficult to improve without systematic CPTED planning during the initial stages. Therefore, it is essential to establish clear territorial boundaries for residents and strangers and for vehicles and pedestrians in pilotis when designing the building. Furthermore, sufficient lighting should be installed to brighten shadowy spaces, and recursive reflective bands should be added to help residents detect hidden strangers.

Building entrance: This was found to have a notable impact on fear of crime at night. To create a safe entrance environment for both pedestrians and residents, it is important to prioritize a strong natural surveillance system. One way to achieve this is by positioning the entrance to face the street. Additionally, when installing landscaping around the entrance to create territoriality, it is important to consider the height of the plants from the ground to the first branch to minimize obstructed visibility and the possibility of hiding (Min, Byun, and Ha Citation2022).

The emergency bell: It should be easily noticeable to pedestrians for effective use in an emergency. To this end, it is crucial to install a sign indicating the location of the emergency bell. Additionally, painting the street pole where the emergency bell is installed can make it more prominent and visible to passersby.

Maintenance: The overall maintenance of the streets must be improved. To manage waste properly, a specific area should be designated for waste disposal and organized to give the impression of ongoing maintenance. Reflective mirrors were found to reinforce fear of crime by making the overall condition of the street visible in the mirror, rather than providing a sense of safety.

5. Conclusions and limitations

In this study, we identify the major environmental factors contributing to the fear of crime among single-female households and recommend measures to create a safer environment around the residential area. We focused on a street in a low-rise residential area and employed an eye-tracking experiment and questionnaires to gather data. However, the study has some limitations that can be addressed in future research. First, we limited our study area to the streets and the specified target group to single-female households. Second, we analyzed only a specific set of factors using the eye-tracking method. While this method allowed us to identify important environmental factors related to fear of crime, we only analyzed factors already known to be associated with fear of crime based on established CPTED guidelines and previous research in South Korea. This approach is useful for understanding the impact of known factors, but other variables that we did not consider may influence fear of crime in real-world settings. Therefore, future studies should broaden their focus to examine a wider range of environmental factors. Additionally, while this study identified environmental factors associated with fear of crime, it did not evaluate the effectiveness of specific improvement plans.

Despite these limitations, this findings hold several notable implications for future research. First, unlike previous studies that focused on the perception of criminal risks or preventing crime occurrence, this study focused on fear of crime as an emotion in and of itself. We also divided fear of crime into two types and analyzed the relationship of each with environmental factors. Second, our study is significant because it used eye-tracking to analyze the intuitive perception of the actual residential environment of the users, leading to important findings on the relationship between the environment and fear of crime. Use of the eye-tracking method along with qualitative questionnaires was advantageous by enabling the quantitative measurement of spatial perceptions and derivation of meaningful results from this relationship.

As creating a safe residential environment is a critical global social issue, future studies can generate practical and meaningful results by applying our method to each unique situation under various conditions. Further, our quantitative and objective findings could prove useful when designing new streets and improving existing ones, particularly in low-rise residential areas, to reduce fear of crime and ensure public safety. Fear of crime is not just a simple negative emotion but significantly impacts an individual’s quality of life. It is a serious social issue not only in South Korea but in many other countries across the globe. Therefore, cities and nations must devise practical measures to manage and alleviate FOC. The approach and methodology employed in this study can be adapted to residential types and physical environments in different social situations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Soohyun Lee

Soohyun Lee is a PhD candidate in the Department of Interior Architecture and Built Environment at Yonsei University. Her research emphasizes the impact of the built environment on human psychology and behavior, including topics such as fear of crime, walkability, and space-based well-being.

Gidong Byun

Gidong Byun is an adjunct professor in the Department of Interior Architecture and Built Environment at Yonsei University. His research focuses on exploring the relationship between human, social, and physical environmental factors that make up cities, with the goal of creating safe urban environments and improving the quality of life for residents.

Mikyoung Ha

Mikyoung Ha is a professor in the Department of Interior Architecture and Built Environment at Yonsei University. Her research focuses on improving the quality of life by emphasizing the importance of spatial environmental cognition and human behavior, as well as crime prevention through environmental design.

References

- Adams, R. E., and R. T. Serpe. 2000. “Social Integration, Fear of Crime, and Life Satisfaction.” Sociological Perspectives 43 (4): 605–629. https://doi.org/10.2307/1389550.

- Alvarez, G. A., and P. Cavanagh. 2004. “The Capacity of Visual Short-Term Memory is Set Both by Visual Information Load and by Number of Objects.” Psychological Science 15 (2): 106–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.01502006.x.

- Baddeley, A. D. 2000. “The Episodic Buffer: A New Component of Working Memory?” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 4 (11): 417–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01538-2.

- Balkin, S. 1979. “Victimization Rates, Safety and Fear of Crime.” Social Problems 26 (3): 343–358. https://doi.org/10.2307/800458.

- Banaji, M. R., and C. D. Hardin. 1996. “Automatic Stereotyping.” Psychological Science 7 (3): 136–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1996.tb00346.x.

- Bargh, J. A., and T. L. Chartrand. 1999. “The Unbearable Automaticity of Being.” American Psychologist 54 (7): 462–479. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.462.

- Blascheck, T., K. Kurzhals, M. Raschke, M. Burch, D. Weiskopf, and T. Ertl. 2017. “Visualization of Eye Tracking Data: A Taxonomy and Survey.” Computer Graphics Forum 36 (8): 260–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/cgf.13079.

- Blöbaum, A., and M. Hunecke. 2005. “Perceived Danger in Urban Public Space: The Impacts of Physical Features and Personal Factors.” Environment and Behavior 37 (4): 465–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916504269643.

- Brantingham, P. J., and P. L. Brantingham. 1998. “Environmental Criminology: From Theory to Urban Planning Practice.” Studies on Crime and Crime Prevention 7 (1): 31–60.

- Brown, B. 2016. “Fear of Crime in South Korea.” International Journal for Crime, Justice & Social Democracy 5 (4): 116–131. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v5i4.300.

- Byun, G. D., and M. K. Ha. 2020. “An Analysis of Factors Affecting Fear of Crime Considering Geographical Characteristics: Focused on Women in 20’s Who are Vulnerable to Crime.” Journal of the Architectural Institute of Korea 36 (5): 23–32.

- Castelhano, M. S., M. L. Mack, and J. M. Henderson. 2009. “Viewing Task Influences Eye Movement Control During Active Scene Perception.” Journal of Vision 9 (3): 6. https://doi.org/10.1167/9.3.6.

- Ceccato, V. 2016. “Public Space and the Situational Conditions of Crime and Fear.” International Criminal Justice Review 26 (2): 69–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057567716639099.

- Ceccato, V., and R. Bamzar. 2016. “Elderly Victimization and Fear of Crime in Public Spaces.” International Criminal Justice Review 26 (2): 115–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057567716639096.

- Choi, J., H. Yim, and D. R. Lee. 2020. “An Examination of the Shadow of Sexual Assault Hypothesis Among Men and Women in South Korea.” International Criminal Justice Review 30 (4): 386–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/1057567719873964.

- Cowan, N. 2012. “The Magical Number 4 in Short-Term Memory: A Reconsideration of Mental Storage Capacity.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 35 (2): 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X11000021.

- Crowe, T. D., and J. Way, edited by 2008. Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design: Theory and Practice. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

- Duchowski, A. T. 2017. Eye Tracking Methodology: Theory and Practice. Cham: Springer.

- Eriksen, C. W., and D. W. Schultz. 1979. “Information Processing in Visual Search: A Continuous Flow Conception and Experimental Results.” Perception & Psychophysics 25 (4): 249–263. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03198804.

- Fattah, E. A., and V. F. Sacco. 2012. Crime and Victimization of the Elderly. Cham: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Felson, M., and R. L. B. and, edited by 2010. Crime and Everyday Life. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Ferraro, K. F. 1995. Fear of Crime: Interpreting Victimization Risk. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

- Ferraro, K. F. 1996. “Women’s Fear of Victimization: Shadow of Sexual Assault?” Social Forces 75 (2): 667–690. https://doi.org/10.2307/2580418.

- Ferraro, K. F., and R. LaGrange. 2017. “The Measurement of Fear of Crime .” In Ditton, J., Stephen, F. (Eds.), The Fear of Crime (pp. 277–308). London: Routledge.

- Foster, S., B. Giles-Corti, and M. Knuiman. 2014. “Does Fear of Crime Discourage Walkers? A Social-Ecological Exploration of Fear as a Deterrent to Walking.” Environment and Behavior 46 (6): 698–717. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916512465176.

- Foster, S., P. Hooper, M. Knuiman, H. Christian, F. Bull, and B. Giles-Corti. 2016. “Safe Residential Environments? A Longitudinal Analysis of the Influence of Crime-Related Safety on Walking.” The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 13 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0343-4.

- Fox, K. A., M. R. Nobles, and A. R. Piquero. 2009. “Gender, Crime Victimization and Fear of Crime.” Security Journal 22 (1): 24–39. https://doi.org/10.1057/sj.2008.13.

- Garofalo, J. 1979. “Victimization and the Fear of Crime.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 16 (1): 80–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/002242787901600107.

- Glaholt, M. G., M. C. Wu, and E. M. Reingold. 2010. “Evidence for Top-Down Control of Eye Movements During Visual Decision Making.” Journal of Vision 10 (5): 15. https://doi.org/10.1167/10.5.15.

- Grohe, B., M. Devalve, and E. Quinn. 2012. ““Is Perception Reality? The Comparison of citizens’ Levels of Fear of Crime versus Perception of Crime Problems in Communities.” Crime Prevention and Community Safety 14 (3): 196–211. https://doi.org/10.1057/cpcs.2012.3.

- Han, M. 2019. “When Ordering Delivery Use the Name of “Lee Mak-chun” and Men’s Shoes at the Entrance… Worried Women.” Money Today, July 7, 2019. https://news.mt.co.kr/mtview.php?no=2019070312435858620.

- Han, S. 2018. “‘Delivery Has Arrived, Please Open the Door.’. Do You Know the Fear of ‘Women Living alone’”? Asia Economy, December 10, 2018. http://view.asiae.co.kr/news/view.htm?idxno=2018121009580959571.

- Han, B., D. A. Cohen, K. P. Derose, J. Li, and S. Williamson. 2018. “Violent Crime and Park Use in Low-Income Urban Neighborhoods.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 54 (3): 352–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.10.025.

- Harries, K. 2006. “Property Crimes and Violence in United States: An Analysis of the Influence of Population Density.” International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences 1 (2): 24–34.

- Hatfield, G. 2002. “Perception as Unconscious Inference.” In Perception and the Physical World: Psychological and Philosophical Issues in Perception, edited by D. Heyer and R. Mausfeld, 113–143. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Haynie, D. L. 1998. “The Gender Gap in Fear of Crime, 1973–1994: A Methodological Approach.” Criminal Justice Review 23 (1): 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/073401689802300103.

- Hendee, W. R., and P. N. Wells. 1997. The Perception of Visual Information. Cham: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Henderson, J. M. 2003. “Human Gaze Control During Real-World Scene Perception.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 7 (11): 498–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2003.09.006.

- Hilinski, C. M. 2009. “Fear of Crime Among College Students: A Test of the Shadow of Sexual Assault Hypothesis.” American Journal of Criminal Justice 34 (1–2): 84–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-008-9047-x.

- Hirtenlehner, H., and S. Farrall. 2014. “Is the “Shadow of Sexual Assault” Responsible for Women’s Higher Fear of Burglary?” British Journal of Criminology 54 (6): 1167–1185. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azu054.

- Hwang, S., B. Kang, and J. Park. 2013. “A Research Study on Crime Prevention for One-Person Households by Type of Houses.” Journal of the Korean Housing Association 24 (4): 9–17. https://doi.org/10.6107/JKHA.2013.24.4.009.

- Imani, F., and M. Tabaeian. 2012. “Recreating Mental Image with the Aid of Cognitive Maps and Its Role in Environmental Perception.” Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 32:53–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.010.

- Irwin, D. E. 1991. “Information Integration Across Saccadic Eye Movements.” Cognitive Psychology 23 (3): 420–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(91)90015-G.

- Irwin, D. E., and G. J. Zelinsky. 2002. “Eye Movements and Scene Perception: Memory for Things Observed.” Perception & Psychophysics 64 (6): 882–895. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03196793.

- Jackson, J. 2009. “A Psychological Perspective on Vulnerability in the Fear of Crime.” Psychology, Crime & Law 15 (4): 365–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160802275797.

- Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage Books.

- Jang, J., and Y. Kim. 2016. A Study on Young Single Female-Headed Households in Seoul and Policy Implications. Seoul: Seoul Foundation of Women and Family.

- Jeffery, C. R. 1971. Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- Jin, H. 2019. “Jo Deok-chul and Kwak Du-pal… Use men’s names on delivery.” The Korean Women’s Newspaper, August 1, 2019. http://www.womennews.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=192070.

- Johansen, S. A., and J. P. Hansen. 2006. “Do We Need Eye 1170 Trackers to Tell Where People Look?.” In CHI’06 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 923–928. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery.

- Jo, K., and T. Kim. 2019. “Gender Differences in Residential Decision by Single-Person Households: With Regard to Safety Needs and Costs of Gwanak-Gu Residents in Their 20s and 30s.” Journal of Korea Planning Association 54 (5): 5–16. https://doi.org/10.17208/jkpa.2019.10.54.5.5.

- Just, M. A., and P. A. Carpenter. 1976. “Eye Fixations and Cognitive Processes.” Cognitive Psychology 8 (4): 441–480. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(76)90015-3.

- Kanan, J. W., and M. V. Pruitt. 2002. “Modeling Fear of Crime and Perceived Victimization Risk: The (In)significance of Neighborhood Integration.” Sociological Inquiry 72 (4): 527–548. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-682X.00033.

- Kang, S. Y., M. K. Ha, and G. D. Byun. 2020. “A Study on the Cognition Tendency of Disorder –Social Integration According to the Vulnerability of Fear of Crime.” Journal of the Architectural Institute of Korea 36 (4): 31–39.

- Keane, C. 1998. “Evaluating the Influence of Fear of Crime as an Environmental Mobility Restrictor on Women’s Routine Activities.” Environment and Behavior 30 (1): 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916598301003.

- Kelling, G. L., and J. Q. Wilson. 1982. “Broken Windows.” The Atlantic Monthly 249 (3): 29–38.

- Kelly, M. 2000. “Inequality and Crime.” Review of Economics and Statistics 82 (4): 530–539. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465300559028.

- Kim, J. 2018. “‘Recipient: Mr. Chun’… Women living Alone Receiving Packages Under Men’s Names.” Dong-A Ilbo, September 17, 2018. https://www.donga.com/news/article/all/20180927/92172983/1.

- Kim, Y. 2021. “Man Said, ‘Please Leave the Delivery in Front of the Door.’” Korean Herald September 6, 2021. http://news.heraldcorp.com/view.php?ud=20210906000573.

- Kooiker, M. J., J. J. Pel, S. P. van der Steen-Kant, and J. van der Steenvan der Steen. 2016. “A Method to Quantify Visual Information Processing in Children Using Eye Tracking.” Journal of Visualized Experiments 113:e54031. https://doi.org/10.3791/54031-v.

- Korea National Statistical Office. 2015. “Household and Family Survey.” http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/index.action.

- Korea National Statistical Office. 2022. “One-Person Households in Statistics.” https://www.kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301010000&bid=10820&act=view&list_no=422143.

- Koskela, H., and R. Pain. 2000. “Revisiting Fear and Place: Women’s Fear of Attack and the Built Environment.” Geoforum 31 (2): 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7185(99)00033-0.

- Kowler, E., E. Anderson, B. Dosher, and E. Blaser. 1995. “The Role of Attention in the Programming of Saccades.” Vision Research 35 (13): 1897–1916. https://doi.org/10.1016/0042-6989(94)00279-U.

- Lane, J., A. R. Gover, and S. Dahod. 2009. “Fear of Violent Crime Among Men and Women on Campus: The Impact of Perceived Risk and Fear of Sexual Assault.” Violence and Victims 24 (2): 172–192. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.24.2.172.

- Lee, G. R. 1983. “Social Integration and Fear of Crime Among Older Persons.” Journal of Gerontology 38 (6): 745–750. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/38.6.745.

- Lee, J., and S. Cho. 2018. “The Impact of Crime Rate, Experience of Crime, and Fear of Crime on Residents’ Participation in Association: Studying 25 Districts in the City of Seoul, South Korea.” Crime Prevention and Community Safety 20 (3): 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-018-0047-6.

- Lee, S. H., M. K. Ha, and G. D. Byun. 2022. “Analysis of Domestic Eye-Tracking Research Trends in the Field of Architectural Space.” Spring Annual Conference of AIK 2022, Seoul, Korea.

- Lee, J. S., S. Park, and S. Jung. 2016. “Effect of Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) Measures on Active Living and Fear of Crime.” Sustainability 8 (9): 872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8090872.

- Lee, S., and S. Wu. 2021. “‘Terror of delivery’: Living with Home Security for Single Households.” Maeil Business Newspaper, April 25, 2021. https://www.mk.co.kr/news/economy/9845382.

- Lewis, D. A., and M. G. Maxfield. 1980. “Fear in the Neighborhoods: An Investigation of the Impact of Crime.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 17 (2): 160–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/002242788001700203.

- Lim, M. 2020. “A Study on Gender Difference of Housing Costs: Focusing on Single-Person Households.” Journal of the Korean Association for Housing Policy Studies 28 (2): 113–129. https://doi.org/10.24957/hsr.2020.28.2.113.

- Luck, S. J., and E. K. Vogel. 1997. “The Capacity of Visual Working Memory for Features and Conjunctions.” Nature 390 (6657): 279–281. https://doi.org/10.1038/36846.

- Malcolm, G. L., and J. M. Henderson. 2010. “Combining Top-Down Processes to Guide Eye Movements During Real-World Scene Search.” Journal of Vision 10 (2): 4. https://doi.org/10.1167/10.2.4.

- Marr, D. 1977. Representing Visual Information. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Artificial Intelligence Laboratory.

- May, D. C. 2001. “The Effect of Fear of Sexual Victimization on Adolescent Fear of Crime.” Sociological Spectrum 21 (2): 141–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732170119080.

- May, D. C., N. E. Rader, and S. Goodrum. 2010. “A Gendered Assessment of the ‘Threat of Victimization’: Examining Gender Differences in Fear of Crime, Perceived Risk, Avoidance, and Defensive Behaviors.” Criminal Justice Review 35 (2): 159–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734016809349166.

- Mellgren, C., and A. K. Ivert. 2019. “Is Women’s Fear of Crime Fear of Sexual Assault? A Test of the Shadow of Sexual Assault Hypothesis in a Sample of Swedish University Students.” Violence Against Women 25 (5): 511–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801218793226.

- Mills, M., A. Hollingworth, S. Van der Stigchel, L. Hoffman, and M. D. Dodd. 2011. “Examining the Influence of Task Set on Eye Movements and Fixations.” Journal of Vision 11 (8): 17. https://doi.org/10.1167/11.8.17.

- Min, Y. H., G. D. Byun, and M. K. Ha. 2022. “Young Women’s Site-Specific Fear of Crime within Urban Public Spaces in Seoul.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 21 (3): 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2021.1941993.

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport. 2013. Guidelines for Crime Prevention Design. Sejong, Republic of Korea: Republic of Korea https://www.molit.go.kr/USR/I0204/m_45/dtl.jsp?gubun=&search=&search_dept_id=&search_dept_nm=&old_search_dept_nm=&psize=10&search_regdate_s=&search_regdate_e=&srch_usr_nm=&srch_usr_num=&srch_usr_year=&srch_usr_titl=&srch_usr_ctnt=&lcmspage=687&idx=10356.

- Moore, M. D., and N. L. Recker. 2016. “Social Capital, Type of Crime, and Social Control.” Crime & Delinquency 62 (6): 728–747. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128713510082.

- National Police Agency. 2005. Design Guidelines for Crime Prevention. Seoul, Republic of Korea: National Police Agency. https://crimeprevention.joins.com/files/%EB%A7%81%ED%81%AC%EC%9E%90%EB%A3%8C2-%ED%99%98%EA%B2%BD%EC%84%A4%EA%B3%84%EB%A5%BC%20%ED%86%B5%ED%95%9C%20%EB%B2%94%EC%A3%84%EC%98%88%EB%B0%A9%20%EB%B0%A9%EC%95%88(%EA%B2%BD%EC%B0%B0%EC%B2%AD).pdf

- Newman, O. 1973. Defensible Space: Crime Prevention Through Urban Design. New York: Collier Books.

- Nickerson, R. S. 1998. “Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises.” Review of General Psychology 2 (2): 175–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175.

- Nisbett, R. E., and T. D. Wilson. 1977. “Telling More Than We Can Know: Verbal Reports on Mental Processes.” Psychological Review 84 (3): 231–259. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.3.231.

- Noland, R. B., M. D. Weiner, D. Gao, M. P. Cook, and A. Nelessen. 2017. “Eye-Tracking Technology, Visual Preference Surveys, and Urban Design: Preliminary Evidence of an Effective Methodology.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 10 (1): 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2016.1187197.

- Pain, R. 1991. “Space, Sexual Violence and Social Control: Integrating Geographical and Feminist Analyses of Women’s Fear of Crime.” Progress in Human Geography 15 (4): 415–431. https://doi.org/10.1177/030913259101500403.

- Pantazis, C. 2000. “Fear of Crime, Vulnerability and Poverty.” British Journal of Criminology 40 (3): 414–436. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/40.3.414.

- Park, A. J. 2008. “Modeling the Role of Fear of Crime in Pedestrian Navigation.” PhD Diss., Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, Canada.

- Park, H.-S. 2018. “Spatial Analysis of Factors Affecting Fear of Crime.” Korean Criminological Review 29 (2): 91–117. https://doi.org/10.21181/KJPC.2018.27.2.91.

- Pasqualotto, A., and M. J. Proulx. 2012. “The Role of Visual Experience for the Neural Basis of Spatial Cognition.” Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 36 (4): 1179–1187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.01.008.

- Piscitelli, A., and A. M. Perrella. 2017. “Fear of Crime and Participation in Associational Life.” The Social Science Journal 54 (2): 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soscij.2017.01.001.

- Pylyshyn, Z. 1999. “Is Vision Continuous with Cognition? The Case for Cognitive Impenetrability of Visual Perception.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 22 (3): 341–365. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X99002022.

- Rayner, K. 2009. “The 35th Sir Frederick Bartlett Lecture: Eye Movements and Attention in Reading, Scene Perception, and Visual Search.” Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 62 (8): 1457–1506. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470210902816461.

- Reid, L. W., and M. Konrad. 2004. “The Gender Gap in Fear: Assessing the Interactive Effects of Gender and Perceived Risk on Fear of Crime.” Sociological Spectrum 24 (4): 399–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732170490431331.

- Rountree, P. W., and K. C. Land. 1996. “Perceived Risk versus Fear of Crime: Empirical Evidence of Conceptually Distinct Reactions in Survey Data.” Social Forces 74 (4): 1353–1376. https://doi.org/10.2307/2580354.

- Schafer, J. A., B. M. Huebner, and T. S. Bynum. 2006. “Fear of Crime and Criminal Victimization: Gender-Based Contrasts.” Journal of Criminal Justice 34 (3): 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2006.03.003.

- Seoul Metropolitan Government. 2013. Guidelines for Crime Prevention Environmental Design. Seoul: Seoul Metropolitan Government. https://news.seoul.go.kr/citybuild/files/2013/05/5180e1e89fd823.67754200.pdf

- Skogan, W. 1986. “Fear of Crime and Neighborhood Change.” Crime and Justice 8:203–229. https://doi.org/10.1086/449123.

- Skogan, W. G., and M. G. Maxfield. 1981. Coping with Crime: Individual and Neighborhood Reactions. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

- Solymosi, R., K. Bowers, and T. Fujiyama. 2015. “Mapping Fear of Crime as a Context‐Dependent Everyday Experience That Varies in Space and Time.” Legal and Criminological Psychology 20 (2): 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12076.

- Solymosi, R., D. Buil-Gil, L. Vozmediano, and I. S. Guedes. 2021. “Towards a Place-Based Measure of Fear of Crime: A Systematic Review of App-Based and Crowdsourcing Approaches.” Environment and Behavior 53 (9): 1013–1044. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916520947114.

- Stafford, M., T. Chandola, and M. Marmot. 2007. “Association Between Fear of Crime and Mental Health and Physical Functioning.” American Journal of Public Health 97 (11): 2076–2081. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2006.097154.

- Tourangeau, R., L. J. Rips, and K. Rasinski. 2000. The Psychology of Survey Response. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Vogt, A. M., and L. Corbusier. 2000. Le Corbusier, the Noble Savage: Toward an Archaeology of Modernism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Warr, M. 1984. “Fear of Victimization: Why are Women and the Elderly More Afraid?” Social Science Quarterly 65 (3): 681.

- Warr, M. 2000. “Fear of Crime in the United States: Avenues for Research and Policy.” Criminal Justice 4 (4): 451–489.

- Whitley, R., and M. Prince. 2005. “Fear of Crime, Mobility and Mental Health in Inner-City London, UK.” Social Science & Medicine 61 (8): 1678–1688.

- Wilson, T. D., and N. Brekke. 1994. “Mental Contamination and Mental Correction: Unwanted Influences on Judgments and Evaluations.” Psychological Bulletin 116 (1): 117–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.117.

- Wolfe, J. M. 1998. “What Can 1 Million Trials Tell Us About Visual Search?” Psychological Science 9 (1): 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00006.