ABSTRACT

This study aims to clarify the characteristics of settlement composition and house layout in Mamasa Toraja and Tana Toraja, Indonesia, focusing on spatial differences. The study reviewed relevant literature, selected settlements for the survey, and prepared settlement layout maps based on satellite imagery. Field surveys were conducted in 2022 to revise the settlement layout maps, record house plans, and interview local residents. The study found that despite having the same cultural roots, Tana Toraja and Mamasa Toraja have different settlement configurations and house layouts. The Tana Toraja settlements have a straight composition with warehouses on the north side and houses on the south side, flanked by a street-like plaza. In contrast, the composition of Mamasa Toraja settlements in the mountainous area is curvilinear, following the natural topography. Although social restrictions based on the caste system have long since been abolished, the layout of houses in the Toraja settlement, especially in Mamasa, still shows a social structure from when the caste system existed. This study provides insights into the unique spatial forms and cultural practices of the traditional villages in Mamasa Toraja and Tana Toraja, highlighting the importance of preserving their cultural heritage.

1. Introduction

Traditional houses and settlements are important cultural heritage because of their unique characteristics that reflect the local climate, natural environment, and cultural practices. Indonesia is the largest archipelagic nation in the world, with diverse topography and traditional culture unique to the region. For this reason, Indonesia has a wide variety of traditional houses and settlements, with each ethnic group having different settlement layouts and building forms (Waterson Citation2009a). Among them are the Toraja, a Malay minority living in Sulawesi with a total population of about 650,000; according to C. Kuryt, the ancestors of the Toraja were maritime people who crossed the sea by boat from the Gulf of Tonkin and settled in the Enrekang area of South Sulawesi (Hartanti and Nediari Citation2014). From here, many followed the Sadang River upstream to the Tana Toraja region, while some followed the Mamasa River (Soeroto Citation2003). The Toraja are said to have left traces of their ancestral experience in the boat-shaped roofs of their traditional architecture.

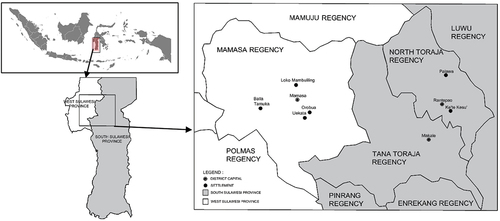

In Sulawesi, Dutch missionaries began proselytizing Christianity in the early 1900s, and around 1920, the Dutch government began to convert the Toraja people to Christianity, abolish slavery, and introduce a tax collection system. However, there was strong resistance from the aristocratic class, which had profited enormously from the slave trade. The Dutch government moved the Toraja settlements from the highlands to the lowlands to make it easier to put down the rebellion (Waterson Citation2009b). The Dutch named the new location Tana Toraja. As a result, the Toraja people living in Sulawesi were broadly divided into the Tana Toraja of South Sulawesi and the Mamasa Toraja who still live in the highlands of West Sulawesi (). Thus, the Tana Toraja and Mamasa Toraja share an ancient culture and religion (Buijs Citation2018). Presently, the Tana Toraja settlements are located on flat land less than 1,000 meters above sea level, and the Mamasa Toraja settlements are located in a mountainous area at an altitude of over 1,000 meters.

Originally, the Toraja people followed a traditional religion called aluk to dolo. Rambu solo rituals and cave tombs are reminiscent of the ancient aluk to dolo. On the other hand, Toraja communities had a rigid caste system consisting of nobles, commoners, and slaves, and the size and design of houses were strictly determined. The nobility lived in large houses called tongkonan and were allowed to decorate the walls with ornaments. The commoners lived in houses called banua, and the lowest class of slaves were said to have lived in crude bamboo huts. Tongkonan refers to the social and religious center of the entire community, and all dwellings are called banua among the Toraja (Toriogoe and Wakabayashi Citation1995, 136–137; Yamashita Citation1999). Aluk to dolo also includes a sense of direction. North is associated with “life” as their ancestors aspired to in mythology, and houses face north.

In contrast, the south, where puya, the land of the dead, is said to be, is associated with “death,” and the dead are placed on the south pillow (Yamashita Citation1999, 29–31). In the internationally renowned settlement of Tana Toraja, stilt houses with large boat-shaped roof gables are neatly arranged along a street-like plaza, with a pair of stilt granaries neatly arranged on the opposite side of the plaza (Funo Citation2005, pp.118–119). The roof ridges of the buildings are oriented vertically north toward the central plaza, which extends east-west. This house layout is said to be based on the religious value of the north as a sacred direction. This settlement composition is shared by the traditional settlements of the Batak Toba people living around Lake Toba in North Sumatra (Fujii Citation2000, 110–122; Funo Citation2005, 98–99). In contrast, in the Bawomataluo settlement on Nias Island, stilted houses stand on both sides of a central stone-paved street-like plaza, with the ridge of the houses oriented parallel to the plaza. A meeting house (bare) is built in the center of the settlement and the chief’s house is also placed in a prominent position (Funo Citation2005, 102–103; Inui Citation2003). The settlements of Tana Toraja and Nias Island are highly regarded as examples of traditional settlement structures unique to Indonesia that have been handed down to the present day and have been inscribed on UNESCO’s Tentative World Heritage List. For this reason, the buildings in these settlements are under protection by the Indonesian government.

Compared to those settlements, the situation in the settlements in Mamasa Toraja is somewhat different. There are two banua in the Orobua settlement in Mamasa Toraja that are believed to be constructed more than 400 years ago. However, this settlement is missing from UNESCO’s Tentative World Heritage List, and there is an urgent need to organize a system for their conservation. The roofs of traditional houses in Mamasa Toraja are thatched with wooden shingles, while those of traditional houses in Tana Toraja are thatched with bamboo. This difference in roofing material is thought to be due to the fact that Mamasa Toraja settlements are located at a higher altitude than Tana Toraja settlements and are in a mountainous area with more rainfall. Differences can also be seen in the settlement composition and house layout. The central street-like plaza, which is unpaved, bends with the topography, unlike in the Tana Toraja settlement, for example. In addition, the houses are lined up on one side of the street with their roof ridge facing vertically, while the roof ridge of the paired warehouse on the opposite side is oriented parallel to the street.

Although the Mamasa Toraja settlements have unique characteristics of highland settlements and buildings that differ from those of the Tana Toraja, systematic research has yet to be conducted to date. Only the Orobua settlement has been surveyed among the Mamasa Toraja settlements previously; there have been four major studies on the settlement. Torigoe and Wakabayashi surveyed the settlement in 1992, the first comprehensive study of the settlement, including its layout, actual measurements of houses, and interviews with residents (Toriogoe and Wakabayashi Citation1995). The second survey was done by the Department of Culture and Tourism in 2006, focusing on its conservation. The study showed that one of the houses had been severely damaged and called for restoration and appropriate maintenance. It also reported that several houses had had their roofing materials changed from wood or thatched to tin, and traditional houses were being expanded with modern structures (Agustono and Asriyadi Citation2006). The third study undertaken by Buijs is a survey of the Orobua settlement from a cultural anthropological perspective. It finds that the shapes and ornaments of banua in Mamasa show ancient traditions and confirm the possibility that the settlers migrated from Sa’dan Toraja a long time ago (Buijs Citation2018). The fourth study by Bura and Ando traced the changes in the buildings in the Orobua settlement from 1992, the time of Torigoe and Wakabayashi’s survey, to the present, showing how the buildings have changed as a result of modernization (Bura and Ando Citation2022).

Although these research results are valuable, it is not possible to determine whether the settlement composition is a feature unique to the Orobua settlement or common to all the Mamasa Toraja settlements, without researching the Mamasa Toraja settlements other than the Orobua settlement. Based on the above, this study aims to clarify the differences in settlement composition and house layout between the two settlements in North Toraja and the four settlements in Mamasa. The analysis focuses mainly on spatial characteristics.

2. Research methodology

After examination of previous literature on traditional settlements and houses in Tana Toraja and Mamasa Toraja, two settlements, Palawa and Ke’te-Kesu’ in Tana Toraja, and four settlements, Orobua, Loko Mambuliling, Uekata and Balla Tumuka in Mamasa Toraja were selected for the study ().

A field survey of each settlement was conducted from 24 to 28 June 2022 in the Tana Toraja settlement and from 2 to 6 July 2022 in the Mamasa settlements as the following: (1) Settlement maps for the field survey were prepared based on Google Earth satellite imagery of 2022. For Orobua settlement, settlement maps from previous studies were also used (Bura and Ando Citation2022). The Google Earth satellite imagery data was then processed to add contour lines using QGrid. (2) Ambiguities in the settlement maps created from satellite imagery were corrected using aerial photographs taken by a drone camera in the field. (3) Interviews were conducted with all house owners regarding house plans and family social status. In addition, the village heads of each settlement were interviewed about the history of the settlements. Based on the information obtained, the similarities and differences between the Tana Toraja and Mamasa Toraja settlements were then analyzed.

3. Characteristics of Tana Toraja settlements

3.1. Palawa settlement

Palawa settlement () is situated in the Sesean district, about 12 kilometers north of Rantepao town in North Toraja Regency. It is located at an altitude of about 800 meters. The central part of the settlement is flat, but the periphery becomes hilly. The settlement has a straight layout with a street-like plaza extending east-west, with traditional warehouses (alang) on the north side and traditional houses (tongkonan) on the south side (). The parapak used to have multiple functions: a place to work, a place to dry rice, a “bundling room” to unite the community, and a place to hold ceremonies related to aluk. The warehouses and house wings are perpendicular to the plaza. There are 12 houses and 18 warehouses in the settlement. The traditional house layout includes 7 one-room houses () three-room houses (). There is no significant difference in the size of these houses.

Currently, Palawa settlement is a tourist destination and is included in the tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites proposed by the South Sulawesi provincial government. Once listed, residents are not allowed to change their settlements or houses without permission. In 2016, the government provided funds to revitalize the settlement, repair the first main house, and build additional public facilities, a souvenir shop, and restrooms. With this development, the community is generating additional income by selling souvenirs and charging entrance fees to visitors, which helps the community maintain this traditional settlement. Currently, however, no permanent residents live in traditional houses; they are used only as a museum and tourist attraction. The locals now live in modern houses built south of the traditional houses. This is because the traditional houses are not suitable for modern living or the space inside the houses is limited.

According to an interview with Paembonan, 53 years old, the representative of Palawa settlement, “The first house built in the settlement is the second house from the east at a higher elevation. From there, the settlement developed westward to a lower elevation. The difference in the number of rooms used to distinguish between ordinary and prestigious houses, but this system is no longer used.”

3.2. Ke’te kesu’ settlement

Ke’te Kesu’ settlement () is the most famous tourist destination in North Toraja Regency and has been on UNESCO’s tentative list since 2009. The village is located four kilometers from the city of Rantepao at an altitude of about 700–800 meters. Entering the settlement from a causeway that crosses rice fields, visitors will find several shops at the entrance. The settlement is laid out in a straight line, with traditional warehouses to the north and traditional houses to the south, flanked by a long, narrow plaza extending eastward (). Modern buildings (common houses and public facilities) surround the settlement but are arranged in such a way that they are not easily visible from the central plaza. The traditional houses and warehouses are oriented at right angles to the plaza. There are 6 traditional houses and 13 traditional warehouses. The layout of the traditional houses includes 5 three-room houses and 1 one-room house; the 5 three-room houses have an ariri posi’ (central pillar), which signifies the role and social status of the house owner in the society (). The one-room house is without it ().

In Ke’te Kesu’ settlement, there are no permanent residents in the traditional houses, and these houses are used as a kind of tourist facility. A few original inhabitants live in modern houses in the south village, and most of them now live in modern houses outside the village. There are many shops developed in the surrounding area, as well as prayer rooms and restrooms, resulting in limited space within the village. According to the regional income data from the Dinas Kebudayaan dan Pariwisata Kabupaten Toraja Utara [Department of Tourism and Culture] (Citation2018), the highest income is found in Ke’te Kesu’ settlement (Rp. 597 million in 2017 and Rp. 665 million in 2018). This is inseparable from the role of the community to actively cooperate with the government in the management of the settlement. Repairs to traditional houses and warehouses are carried out in cooperation with the community, financed by entrance fees and souvenirs.

According to Layuk Sarong Allo, 75 years old, an elder of the settlement, “The original village was located in the mountains and later moved to the flat area. The first house built in the village was the third house from the east, and the last house was built at the western end.” Ferdianta, 33 years old, said, “The second house on the west side of the Ke’te Kesu’ settlement has been used as a museum (Museum Indo’ Ta’dung) since 1998. The space under the house has been expanded to serve as an exhibition space, which is managed by the family that owns the house until now. In other settlements, the houses have been converted into concrete structures with tin roofs, and the interiors have been modernized.”

4. Characteristics of Mamasa Toraja settlements

4.1. Orobua settlement

Orobua settlement () is located about 10 km from Mamasa town at an altitude of 1,200 meters. Orobua was once the residence of the chief who ruled the Mamasa region. There is no clear structure in the layout of the settlement, and the orientation of the buildings varies, but basically, the warehouse buildings are built perpendicular to the house buildings. However, there are also two warehouses oriented parallel to the houses ().

The most important chief’s house (banua sura’ layuk) is located in the center of the settlement (). According to the settlement history described by the 17th chief, Ir. Timotius, 67 years old, this house was moved from Buntubuda (near Mamasa town) during the leadership of the 12th chief, built about 430 years ago. It is considered to have retained its original appearance, with a wooden roof. This is different from the houses in Tana Toraja, which are roofed with bamboo. This difference is thought to be due to the fact that the settlements of Mamasa Toraja are located at an altitude of more than 1,000 meters above sea level, where rainfall is frequent, and more solid materials are used as a countermeasure. The houses of high-status residents are located on the east side of the village where there is no plateau, the houses of commoners are spread out on the west side of the plateau, and the settlement is arranged in three rows. Currently, there are 10 traditional houses and 8 traditional warehouses in the settlement. The layout of the traditional houses includes 4 four-room houses, 3 three-room houses, and 3 two-room houses. There is no one-room house.

However, the wave of modernization is also sweeping through Orobua settlement, located deep in the mountains. After correcting the layout map of Torigoe and Wakabayashi in 1992 (Toriogoe and Wakabayashi Citation1995) based on satellite photographs and interviews, authors confirmed that there were 11 traditional houses and 12 traditional warehouses in Orobua settlement in 1992 (Bura and Ando Citation2022). In the last 30 years, the number of traditional houses and warehouses has decreased by 1 and 4, respectively. Unlike the Tana Toraja settlements, the Mamasa Toraja settlements are not included in the tentative list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. As a result, residents are free to expand and renovate their buildings. Many of the remaining traditional buildings have been modified and extended with modern houses. Changed materials of roofs and walls and modern houses added to the settlement have extensively changed the traditional landscape. In particular, modernization changed elements with religious-symbolic meaning, such as the size of the front door, wall decorations, and kitchen with stone stove, indicating that modernization affects the consciousness of the residents towards tradition. If the religious practice of maintaining traditional houses fades away, there is a possibility that traditional houses will be damaged or demolished in the future (Bura and Ando Citation2022).

4.2. Loko mambuliling settlement

Loko Mambuliling settlement () is located in the northern part of Mamasa town at an altitude of 1,280 meters. The settlement is located on a hill surrounded by valleys and is relatively flat. However, due to the lack of sufficient length in the east-west direction, the settlement is arranged in four rows (). There are 12 traditional houses and 6 traditional warehouses in the village. The layout of the traditional houses includes 3 four-room houses, 8 three-room houses, and 1 two-room house. There is no one-room house. All the warehouses are perpendicular to the houses.

The traditional chief’s house, banua sura’ layuk, is located on the lowland at the northeast corner of the settlement. From there, the settlement expanded to the south and west. According to an interview with resident Pampang, 50 years old, “In the beginning, there were only warehouses surrounded by fields. Since the settlement was quite far away, houses were built gradually. The first house built was originally a banua sura’, but during the colonial period, the chief was appointed head of the settlement by the Dutch government, and the house was upgraded to a banua sura’ layuk.”.

4.3. Uekata settlement

Uekata settlement () is located about 2 kilometers from Orobua settlement, at an altitude of about 1,400 meters. The settlement has a curvilinear layout with a road following the topography and buildings parallel to the road. There are 26 traditional houses and 17 traditional warehouses in the village. There is no clear structure in the layout of the settlement, and the orientation of the buildings varies, but basically, the houses are oriented to the northeast, and the warehouses are perpendicular to them (). However, there are two warehouses that are parallel to the houses. The layout of the traditional houses includes 5 four-room houses, 19 three-room houses, and 2 two-room houses. There is no one-room house.

According to an interview with resident Edward, 39 years old, the development process of the settlement started with the first four-room house in the center of the settlement, followed by a four-room house to the west of it, and finally a four-room house to the east.

4.4. Balla Tumuka Settlement

Balla Tumuka settlement () is located at an altitude of more than 1,370 m, in the southwest of Mamasa town. It has a curvilinear layout similar to that of Uekata, with a road following the topography and buildings parallel to it, but the road makes a right-angle turn in the middle of the settlement (). The warehouse buildings are perpendicular to the houses, except one warehouse that is oriented parallel to the house.

The settlement has 54 traditional houses and 27 traditional warehouses, making it one of the largest Toraja settlements. The layout of the traditional houses includes 7 four-room, 13 three-room, 21 two-room, and 13 one-room houses. According to an interview with Depapaluang, 67 years old, head of the settlement, the development process of the settlement started with the four-room house in the southern part of the settlement, followed by the development along the road to the north of the house. This settlement is estimated to be about 100 years old, and most houses face east. This feature is what makes it different from other Mamasa settlements. According to the beliefs of the people who live in this settlement, the east is the direction in which the sun rises and is believed to be the source of wealth. This is contrary to the beliefs of the aluk, who consider the north to be the dwelling place of the Creator. However, due to geographical and technical constraints, the layout of the settlement follows the shape of the land.

5. Comparison of Tana Toraja and Mamasa Toraja settlements

Firstly, the composition of the settlements is compared. The Tana Toraja settlements are located on

flat land below 1,000 meters above sea level and have a straight settlement composition with a street-like plaza. The warehouses and houses are oriented at right angles to the plaza, with the warehouses on the north and the houses on the south. In contrast, the layout of the Mamasa Toraja settlements, located in a mountainous area at an altitude of over 1,000 meters, is not straight but naturally curved to suit the terrain. If the site is long, the houses are arranged in a row; otherwise, they are divided into several rows. The orientation of the buildings is perpendicular to the street for houses and parallel to the street for warehouses. Also, unlike the Tana Toraja settlements, the houses and warehouses are not separated by the plaza; they are close together.

Secondly, the size of the settlements and the composition of the buildings are compared. Overall, Mamasa Toraja settlements have more houses than Tana Toraja settlements. However, looking at the ratio of houses to warehouses, there are more warehouses than houses in the Tana Toraja settlements, while there are more houses than warehouses in the Mamasa Toraja settlements. In addition, the size of houses and warehouses in the Tana Toraja settlements is comparable. In contrast, the size of warehouses in the Mamasa Toraja settlements is much smaller than that of houses. The number of warehouses was once an indicator of wealth, and the number and size of warehouses may have been a symbol of economic power. In the Orobua settlement, more warehouses than houses have been demolished since the 1990s, suggesting that warehouses are no longer needed in the community and that there may have been more warehouses in the Mamasa Toraja settlements in the past. The number of rooms and the design of houses were traditionally strictly determined by the caste system in Toraja. In the Tana Toraja settlements, there are only two types of houses: those with three rooms and those with one room (). Moreover, the difference in size between them is not very large. On the other hand, in the Mamasa Toraja settlements, there are three settlements with three types of houses ranging from four to two rooms and one settlement with four types, and the size of the houses is proportional to the number of rooms (). One-room houses indicate that the owners are from the lower caste and are found in both settlement in Tana Toraja and Balla Tumuka in Mamasa Toraja. There are no one room types in the other three settlements in Mamasa Toraja, which seems to give a sense of democratic housing composition. In fact, many of the houses have been renovated, and those that originally had one or two rooms have been converted into two or three rooms. Judging by the arrangement of the houses, social stratification in the Balla Tumuka settlement is more pronounced than in other Toraja settlements, suggesting that it was probably a more traditional feudal society. Social restrictions based on the caste system have long since been abolished, but the layout of the houses still shows a social order from the time when the caste system existed.

Table 1. Number and percentage of traditional buildings in Tana Toraja settlements.

Table 2. Number and percentage of traditional buildings in Mamasa Toraja settlements.

6. Discussions

Although the linear settlement layout of Tana Toraja is locally believed to have been determined on the basis of aluk to dolo, Torigoe and Wakabayshi argued that this straight layout is a Dutch colonial feature associated with the relocation of settlements from the high mountains (Toriogoe and Wakabayashi Citation1995, 126). The relocation of the settlement by the Dutch government approximately 100 years ago is confirmed by an interview with Layuk Sarong Allo, an elder of the Ke’te Kesu’ settlement. In other words, while it is certain that the houses and warehouses in Tana Toraja are several hundred years old, it is still being determined to what extent the previous layout of the settlements was maintained when the settlements were relocated.

On the other hand, interviews indicate that, except for Orobua, most of the settlements in Mamasa Toraja are also relatively new, having been formed after the Dutch colonial period. The layout of Mamasa Toraja settlements in the mountains is not straight, following the natural curves of the terrain. Although there are significant differences between the settlement landscapes of Tana Toraja and Mamasa Toraja, these settlements are linear settlements stretching along the main streets, sharing a common principle in their spatial organization.

The straight linear settlement structure of Tana Toraja settlements is similar to the Batak Toba settlement in North Sumatra. The Batak Toba settlement is very similar to the Tana Toraja settlements, not only in its settlement structure but also in the appearance of the houses. However, it is necessary to look at the relationship between topography and settlement configuration over a wider region. Did the Tana Toraja move to the lowlands and adopt a straight linear settlement pattern? Or did the Mamasa Toraja build settlements in the highlands, adapting their settlement layout to the topography? In addition, a comprehensive study of not only the morphological similarities of settlement configurations but also the cultural background and customs of the region is necessary.

7. Conclusion

The results of this study show that Tana Toraja and Mamasa Toraja have different settlement configurations and house layouts despite having the same cultural roots. The Tana Toraja settlements are located on flat land below 1,000 meters above sea level and have a straight settlement configuration with a street-like plaza. The warehouses and houses are at right angles to the plaza, with the warehouses on the north and the houses on the south. In contrast, the layout of the Mamasa Toraja settlements, located in a mountainous area at an altitude of over 1,000 meters, is not straight but naturally curved to fit the terrain. The orientation of the buildings is perpendicular to the road for houses and parallel to the road for warehouses. Also, unlike the Tana Toraja settlements, the houses and warehouses are not separated by the plaza but are built close together.

Traditionally, the caste system strictly determined the number of rooms and the design of houses in Toraja settlements. In the Balla Tumuka settlement of Mamasa Toraja, the social hierarchy of the inhabitants is most strongly expressed in the types of houses, with the number of rooms ranging from one to four. Although social restrictions based on the caste system have long since been abolished, this layout of houses still conveys the social order of the time when the caste system existed.

The Mamasa Toraja settlement has not attracted much attention in the past because of its location deep in the mountains. However, in response to the high rainfall in the highlands, the roofs are made of wooden shingles, a feature that distinguishes them from the bamboo-thatched houses of Tana Toraja on the plains. In recent years, the wave of modernization has also reached the Mamasa Toraja settlements, and many of the remaining traditional buildings have been modified by changing the materials of the roofs and walls or by adding modern houses, changing the traditional landscape. The Orobua settlement has two Banua buildings, said to be more than 400 years old. However, they are not on UNESCO’s Tentative List of World Heritage Sites and may be damaged or demolished in the future if the religious practice of maintaining traditional houses fades away. There is an urgent need to develop a conservation plan and organization to carry it out with public support.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude for the invaluable assistance received from The Cultural Conservation Centre in Makassar, South Sulawesi Province, as well as the North Toraja and Mamasa local governments, custom chiefs, communities, and respondents. Their permission, contributions, and cooperation were essential to this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agustono, M., and Y. Asriyadi. 2006. Tudi Teknis Kompleks Rumah Adat Indonasesenapdang, Kabupaten Mamasa Provinsi Sulawesi Barat [Study on the Indonesian Traditional House Complex in Sesenapdang, Mamasa Regency, West Sulawesi Province]. Makassar: Departemen Kebudayaan dan pariwisata [Ministry of Culture and tourism]. Balai pelestarian peninggalan purbakala Makassar [Makassar ancient heritage preservation centre].

- Buijs, K. 2018. Ancient Traditions in Toraja Houses of Mamasa. West Sulawesi, Banua as Centre of Power of Blessing. Makassar: Ininnawa.

- Bura, P., and T. Ando. 2022. ““Evaluation of the Orobua Settlement as Historical Heritage in West Sulawesi.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 22 (3): 1582–1597. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2022.2090366.

- Dinas Kebudayaan dan Pariwisata Kabupaten Toraja Utara [Department of Tourism and Culture]. 2018. Penerimaan dari Objek/Agro Wisata Dinas Kebudayaan dan Pariwisata Kabupaten Toraja Utara Tahun 2017-2018.” [Receipt from objects/agritourism Agency of Culture and Tourism of North Toraja Regency 2017-2018]. North Toraja: Culture and Tourism Agency.

- Fujii, A. 2000. Shuraku Tanhou [Exploring Villages]. Tokyo: Kenchiku Shiryo Kenkyujo.

- Funo, S., edited by. 2005. Sekai Jukyo-Shi [World Dwelling Records]. Kyoto: Showado.

- Hartanti, G., and A. Nediari. 2014. ““Pendokumentasian Aplikasi Ragam Hias Toraja Sebagai Konservasi Budaya Bangsa Pada Perancangan Interior.” [Documentation of Toraja Ornamental Applications for Conservation of Nation’s Culture in Interior Design].” Humaniora 5 (2): 1279–1294. https://doi.org/10.21512/humaniora.v5i1.3079.

- Inui, N. 2003. “Indoneshia sumai to shuraku no Kiritsu Niasu-zoku [Indonesian Dwellings and Village Discipline, Nias].” In Higashi Ajia Tonan Ajia No Jubunka [Housing Culture in East and Southeast Asia], edited by A. Fujii and S. Hata, 203–218, Tokyo: Hoso daigaku shuppankai.

- Soeroto, M. 2003. “Pustaka Budaya dan Arsitektur Toraja”[Toraja Cultural and Architectural]. Jakarta: Balai Pustaka.

- Toriogoe, K., and H. Wakabayashi. 1995. Wazoku Tora- ja [Warrior Toraja]. Tokyo: Taishukan Shoten.

- Waterson, R. 2009a. The Living House. Boston: Tuttle.

- Waterson, R. 2009b. Paths and Rivers: Sa’dan Toraja Society in Transformation. Brill. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1163/j.ctt1w76vcg.11.

- Yamashita, S. 1999. “Toraja.” In Sumai Wa Kataru [Housing is a Way of Life], edited by K. Sato, 25–42, Kyoto: Gakugei Shuppansha.