ABSTRACT

Park pathway characteristics can influence the movement of visitors and the functional usage of space. This article aims to assess the design of different types of public parks in Cairo, Egypt, through the lens of space syntax, which identifies spatial layout as a primary factor that determines pedestrian movement. We integrate space syntax metrics with field observations to examine the underlying spatial logic of small, medium and large public parks, and compare their three structures based on form and function. The results indicated that the degree of spatial accessibility and degree of control over accessing adjacent walkways were positively associated with movement flows on each walkway segment. However, many park facilities, such as wedding halls and theatres, tended to be randomly distributed due to the heavy commercialisation of the parks, which places facilities based on land availability. Our findings provide insights into the design and management of park environments. Overall, leisure facilities should be provided based on community needs. Noisy activities should be placed in isolated zones to attenuate noise. In addition, activities that serve various people groups should be located along highly accessible pathways to encourage their use.

1. Introduction

The spatial properties of the urban landscape, such as pathway network patterns, influence the accessibility of urban spaces and, in turn, physical activity and social interactions within these spaces (Zhai, Korça Baran, and Wu Citation2018). Urban parks, a basic category of green spaces in cities and an integral element of urban structure, can promote outdoor physical activity (Veitch et al. Citation2021). Therefore, parks are essential to every aspect of people’s health (Nantel, Mathieu, and Prince Citation2010). Accessible park locations at various urban scales can encourage park use by various social groups, particularly disadvantaged groups such as children, older-adults and low-income people (Can Traunmüller, İ̇nce Keller, and Şenol Citation2023; Nam and Kim Citation2014; Şenol and Atay Kaya Citation2021). To better manage the flow of a park’s users and understand how various social groups move in its spatial layout and where overcrowding is most likely to develop, it is crucial to understand the spatial properties of its infrastructure and leisure facilities. Being unaware of a park’s infrastructural network, including pathway structure, activity zone distribution, and entrance location, may result in designs that facilitate congestion or hinder access to the park’s main spaces and facilities and, in turn, discourage different social activities (Zhai and Baran Citation2016).

Urban parks are most often assessed based on their equipment facilities (Biernacka, Kronenberg, and Łaszkiewicz Citation2020; Niță et al. Citation2018), visual qualities (Mahmoud Citation2017; Polat and Akay Citation2015), and the number of users (Rankovič and Keča Citation2014). However, the way park amenities (e.g., restaurants, toilets, playgrounds and amphitheatres) are spatially distributed across its landscape is less studied from a “spatial logic” point of view. Although previous studies acknowledge that spatial configurational properties play a central role in determining people’s environmental experience (Hillier Citation1996), few studies have addressed these properties within park design assessments (Zhai and Baran Citation2016; Zhai, Korça Baran, and Wu Citation2018).

Some studies have used GPS tracking to understand visitor spatial behaviour, patterns of recreation flows within parks, and/or the intensity of users’ physical activity (Barros, Moya-Gómez, and Gutiérrez Citation2020; Liu et al. Citation2021; Zhai et al. Citation2021). Other studies combined GPS data or field observation data with simulation approaches, such as space syntax, to better understand user temporal-spatial behaviour (Zhang, Lian, and Xu Citation2020). Space syntax theories provide techniques to describe the configurational properties of the urban landscape and their potential impacts on various types of human behaviour, such as route choice (Shatu, Yigitcanlar, and Bunker Citation2019) and movement patterns (Hillier et al. Citation1993; Mohamed Citation2016). Typically, spatial configuration describes the overall relational pattern that rises from how spaces are connected (Hillier Citation1996). According to the theory of “natural movement” (Hillier et al. Citation1993), the configuration of the urban layout is the primary determinant of urban movement patterns and, thus, other urban functions and social practices. The theory postulates that more (less) accessible spaces will draw more (fewer) pedestrian flows.

Space syntax has been extensively used to analyse both urban spaces (Hillier Citation1996) and buildings (Dawes, Ostwald, and Lee Citation2021). However, few studies have applied this approach to the analysis of urban parks. Furthermore, most prior research tended to focus on park accessibility at city, district, or neighbourhood scale (e.g., Mohamed, Kronenberg, and Łaszkiewicz Citation2022; Nam and Kim Citation2014; Şenol and Atay Kaya Citation2021; Tannous, Major, and Furlan Citation2020), rather than park pathway configurational attributes (e.g., Zhai et al. Citation2021; Zhai, Korça Baran, and Wu Citation2018). In their studies, Zhai et al. (Citation2018) and Zhai and Baran (Citation2016) used space syntax to examine the association between park pathway configurational characteristics and walking behaviour. Their findings confirmed a positive association between pathway use level and pathway spatial attributes, such as the degree of syntactic accessibility and distance to the park gate. To the best of our knowledge, prior research has not compared the spatial layouts of different types of parks. Additionally, previous studies only considered some indexes of accessibility, such as degree of syntactic centrality, disregarding other space syntax metrics that are able to indicate the expected distribution of spaces from a potential origin. Furthermore, while the aforementioned studies have empirically shed light on the importance of spatial layout characteristics, much remains to be studied, particularly the configurational properties of park infrastructural networks and how different patterns result in varying degrees of park accessibility.

The main aim of this study is to investigate the transferability of space syntax in the context urban parks, mainly to better understand patterns in use. We combine space syntax analysis with field observation data to examine the association between walkway syntactic attributes and pedestrian movement rates. The following research questions are addressed: (1) To what extent can space syntax be used to understand park layout?; (2) How are park amenities and leisure facilities spatially distributed from a “spatial logic” point of view? (3) Do statistically significant syntactic differences exist among different types of parks?; (4) How are visitors’ leisure walk routes distributed relative to pathways’ configurational attributes? Or how is the level of walkway use related to walkway spatial attributes? The following hypotheses are therefore posed:

H1:

Park facilities and amenities are not chaotic; rather, they follow a set of spatial logics that are related to pathway configurational characteristics.

H2:

Leisure walking trips are related to pathways’ configurational characteristics.

To answer research questions, we describe and analyse spatial layouts of a sample of nine public parks in Greater Cairo, the capital and the largest city in Egypt. The selected parks offer diversity in size, shape, design style, and location to better understand patterns in use or spatial relations and determine the spatial characteristics of Egyptian parks. In our study, we paid attention to how the spatial layout addresses the requirements of various categories of users.

This study tests the transferability of space syntax in the context urban parks. Our findings are helpful in understanding the relationship between walkway syntactic characteristics and route use level within urban parks, and grasping the underlying logic associated with the spatial arrangement of amenities and leisure facilities in relation to parks’ entrances and pathway networks. They also would help designers and managers understand and predict the spatial distribution of children, teenagers, adults, and older adults when they walk in urban parks. Thus, these findings have implications for the design and management of future park layout.

2. Materials and Methods

The proposed framework for examining the spatial logic of park layout comprises three main steps. First, we perform space syntax analysis to quantify local and global accessibility for the selected nine parks. Second, we chose two parks to conduct field observations to map out users’ spatial distribution in urban parks. Third, we run various regression models to investigate the statistical association between pathway accessibility measures (i.e., predictor variables) and walking visitor count per pathway segment (i.e., dependent variable).

2.1. Study sites

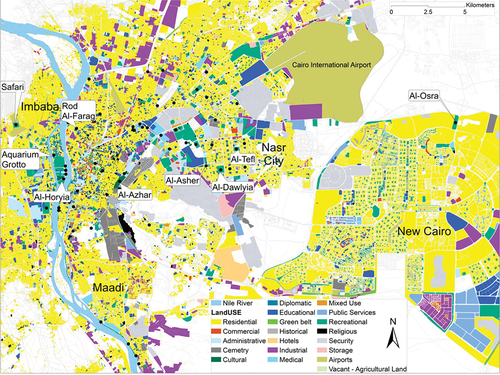

We conducted our analysis for nine public parks located in Greater Cairo, Egypt. The metropolitan area accommodated more than 22 per cent of the country’s 95.8 million citizens in 2016, with an area of approximately 1709 km2 (CAPMAS Citation2017). The nine selected parks cover an area of nearly 112 hectares, representing 27 per cent of the total area of public parks in Greater Cairo. They are self-financing, easily identified, regularly open, and are managed and maintained. While Al-Azhar Park, Al-Osra Park, and Aquarium Grotto Park are managed by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, the military, and the Ministry of Agriculture, respectively, other parks are managed by a Specialised Gardens Agency (SGA). The selected parks represent the broader diversity of parks in Cairo in terms of equipment and leisure activities, shape, design style, size, and location within the metropolis (see, Appendix A ). Additionally, these parks serve various social groups (see, Appendix A ). We have classified them into three categories based on size: (1) Neighbourhood parks (Al-Asher, Al-Horyia, Aquarium Grotto and Rod Al-Farag) range in size from 2 to 4 hectares; (2) Community parks (Al-Tefl and Safari) have an area between 4 and 20 hectares; and (3) Metropolitan parks (Al-Dawlyia, Al-Azhar and Al-Osra) are over 20 hectares in size and are assumed to serve the entire Greater Cairo region.

A neighbourhood park usually has a single entrance for visitors. The entrance space is most often linear and comparatively small. Apart from the Aquarium Grotto garden, neighbourhood parks have a geometric, symmetrical design (). In contrast, community and metropolitan parks have more than one entrance, all of which are almost square-shaped and comparatively large. In terms of design style, community parks can be either geometric/formal (Al-Tefl) or a mixture of geometric and organic forms (Safari). This is not the case in metropolitan parks, where naturalness is expressed through irregular shapes.

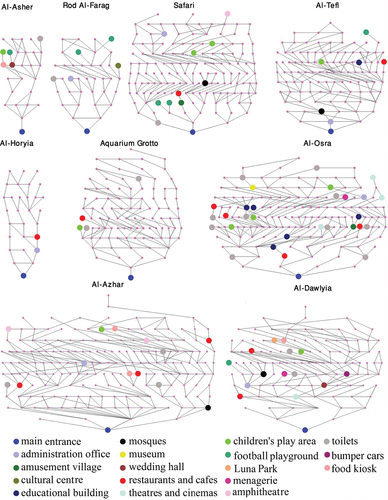

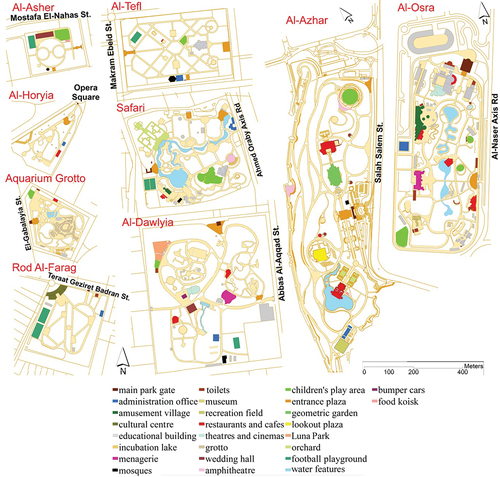

Figure 1. Spatial layouts of the nine case study public parks in Greater Cairo. For colour illustrations, please refer to the electronic version of the article.

As noted, there is a diverse spectrum of infrastructure and leisure facilities in the study sites, including entertainment (an amusement village, a theatre, a cinema, an amphitheatre, Luna Park and a menagerie), restaurants and cafes, services (prayer area, public toilets, administration office and main gate building), educational buildings (library, artistic workshops building), cultural buildings (cultural centre and museum), social buildings (wedding hall), games (football playground and children’s play area), water features (lakes and fountains) and green areas. As shown in , these facilities are not necessarily present in all parks, particularly small- and medium-sized ones. However, each park has at least one commercial amenity or ticketed leisure facility to get commercial revenue.

We have categorized activity areas in parks based on noise challenges we have encountered: (1) noisy activities, including human-generated noises (playground areas and wedding hall) and high-frequency noises from generators and musical equipment and vehicles (amusement village, a theatre, a cinema, an amphitheatre, Luna Park, artistic workshop areas, parking lots); (2) quiet activities, which have acceptable levels of background noise (prayer area, cultural centre, museum, library, food outlets, public toilets, administrative office, lake, fountain) (National Academy of Engineering Citation2013). We have also classified functions based on the required privacy level: (1) privacy-seeking activities (i.e., those serving certain people groups, such as children play areas, football fields, administration office and wedding hall); (2) public-seeking activities (i.e., functions targeting various social groups, such as public toilets, prayer area, parking area, food outlets, amphitheater and library).

2.2. Data sources

Data about the facilities and activities in each park was collected through site visits and surveys in the summer of 2021. We used publicly available maps from Google Earth and Cairo and Giza Beautification Agencies to construct maps of the study sites. The obtained data were in the form of satellite images, AutoCAD drawings of parks’ layouts and land uses, manual drafting of parks’ different zones and photographs. We validated publicly available information on park facilities and leisure activities through onsite visits. Additionally, collected data from pedestrian movement surveys were used to map walking behaviour. While acquiring data on the spatial layouts of parks was relatively easy, additional time and effort were necessary to digitize the satellite images, create convex maps, and process justified graphs.

3. Methods

3.1. Space syntax

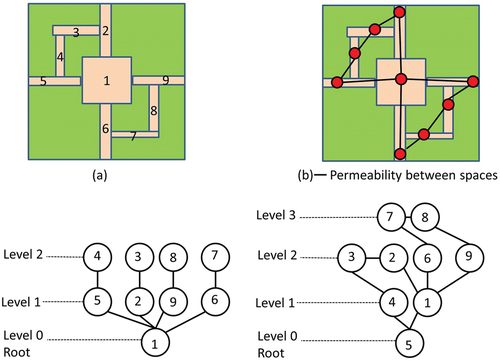

Space syntax is a set of theories and analytical methods that provide quantitative measures for various scales of accessibility within the urban system. Based on the theoretical metrics of graph theory, the ultimate aim of space syntax is to objectively describe and quantify the configurational properties of the spatial layout. In space syntax analysis, adjacent spaces can be represented as a “convex map” of the least set of fattest convex spaces that cover a layout (Hillier Citation1996). Then, a justified graph (JG) of vertices (nodes) and edges (links) is utilised to mathematically reveal the underlying topological relations between functional spaces comprising the spatial structure of a layout. In this graph, a given space (usually referred to as “the root space”) is set at the bottom, and all spaces that are directly connected to it are placed on a separate level (step) above until we traverse all spaces in the system. “Step depth” measures the number of steps from the selected root space to all other spaces within the system (van Nes and Yamu Citation2021). shows an example of a hypothetical park layout and justified graphs for spaces 1 and 5. By starting by space 1, we find that it is directly connected to four spaces. By putting each direct connection on a separate level, we notice that for space 1 we need to join up two levels or steps to reach all spaces. As to space 5, we can see that it is linked to space 1 and 4. Then space 1 is connected to space 2, 6, and 9, while space 4 is connected to space 3. Afterwards, space 6 is connected to 7, while space 9 is connected to space 8. So we can find that we need three steps to pass through the whole layout. Apparently, space 1 is more spatially accessible than space 5 because space 1 requires a lower number of levels (2). These justified graph visualizations are used to quantify various syntactic attributes for each space in the system.

Figure 2. An example of a hypothetical park layout (a), permeability between spaces (b), and justified graphs for space 1 and space 5.

In this study, the spatial layouts of the nine parks are represented by modified convex maps. Traditional axial and convex representations were originally proposed to reveal visibility and, in turn, spatial accessibility (permeability) in buildings and built environments. However, they might not be fully suitable for modelling parks, where boundaries of spaces and pathways are usually poorly defined by natural elements; therefore, visibility does not always lead to spatial accessibility (Zhai, Korça Baran, and Wu Citation2018). For instance, a lake can be visually accessible, but we cannot walk through it. The modified convex maps follow a “stroke-based network” representation to capture the continuity of pathways (Thomson Citation2004). A stroke refers to “a set of one or more arcs in a non-branching, connected chain” (Thomson Citation2004, 4). In a conventional axial map, axial lines are drawn to represent a single curving individual space, whereas in the new representation proposed by Thomson (Citation2004), a single stroke is constructed to model “a linear no-branching space, even when the pathway is curving” (Zhai and Baran Citation2016, 192). Following this idea, the boundaries of constructed convex spaces overlap with the actual boundaries of individual pathway spaces.

This study analyses all functional spaces that potential users can spatially access. Functional spaces are areas within a park that can accommodate physical activities (like seating, meeting, playing and walking) (Bedimo-Rung, Mowen, and Cohen Citation2005). Transitional spaces, like pathways and entrances, are also considered functional spaces. After identifying all available functional spaces, a convex map for each park can be created on the basis of the concept of a stroke-based network. Boundaries between individual spaces are identified based on the functions of these spaces, and branching paths are divided at points of intersection into a set of convex spaces.

Connections between convex spaces are created based on the physical permeability among spaces. The configurational attributes of each space are then calculated using DepthMap software (Turner Citation2004), while the justified graphs are automatically constructed using JASS software (Koch Citation2004). The results of space syntax analysis were exported from DepthMap as MIF files to MapInfo Professional and then to ArcGIS 10.6 in the form of shapefiles. The assessment concentrated on five predictor variables, including connectivity, global integration (Hillier Citation1996), control (Hillier and Hanson Citation1984), controllability and relativised entropy (Turner Citation2004). Counting how close each space is to all spaces reflects the centrality of space (i.e., global integration), whereas calculating how many spaces are directly connected to a root space can give the local measure of connectivity. Control value documents “the degree of choice that each space represents for its immediate neighbours as a space to move to” (Hillier and Hanson Citation1984, 109). Spaces with higher control values are expected to have higher influence over their adjacent spaces (van Nes and Yamu Citation2021). In other words, control highlights visually dominant spaces. In contrast, controllability value “picks out areas that may be easily visually dominated” (Turner Citation2004, 16). Additionally, relativised entropy reveals how distributed a system is from a space of origin (Turner Citation2004). Finally, the specific description and respective purpose of each predictor are given in Appendix A, .

3.2. User walking behaviour

We selected Al-Dawlyia Park and Al-Azhar Park to observe user walking behaviour. The purpose is to examine the association between pathway configurational attributes and visitor walking. Al-Dawlyia Park exemplifies municipal parks in Cairo, whereas Al-Azhar Park represents an example of a park managed by the private sector. In each park, we utilised the gate counting method (Vaughan and Grajewski Citation2001) to record the number of visitors crossing an imaginary perpendicular line over the pathways.

In July 2022, gate locations were selected from randomly-chosen pathways, using the following criteria: (1) gates located at a variety of distances from main entrance; (2) gates cover a range of heavily-used, moderately-used and lightly-used routes in the park. Four trained observers counted people at 42 and 39 gates in Al-Dawlyia Park and Al-Azhar Park, respectively. Observers used stopwatches and stood at each gate location drawing a perpendicular imaginary line over the walkway space and counting everybody passing over this line for five minutes per hour, where the pedestrian movement rate per hour was calculated. Pedestrians that were in the walkways space, but did not cross the line, were not counted. All observations were recorded on pre-prepared tables. Tally counts were done by putting down one stroke for each individual who has passed. A simple inter-rate reliability check for counting park users was conducted by observing randomly-chosen 10 gates by the same observers in one round of observations. The number of gates the four observers agreed on in counting pedestrian movement was eight. We planned to observe each park once (5:30 p.m. to 7:30 p.m.) on a weekend (two rounds in the period) and once on a randomly selected weekday (two rounds in the period). The selected observation period (5:30 p.m. to 7:30 p.m.) was usually the peak of traffic and, therefore, captured the maximum park use. Visitors were categorised into five groups: walking children (anybody who seems to be under 12 years of age), walking teenagers (from about 12–18 years old), walking adults (from about 18–60), and walking older adults (anybody who appeared to be over 60 years old). Finally, all the observed data in the two parks were added to the GIS shapefiles of parks, and the results from field observations were joined to those from space syntax analysis based on the spatial relationship. Eventually, the obtained attribute table, as well as original attribute tables of the nine parks, was exported to Microsoft Excel and, then, to NCSS version 9 software in the form.CSV files containing information such as integration, connectivity, control, gate number, and people count to conduct statistical analysis.

3.3. Statistical analysis

The analysis was conducted in three stages. First, we conducted descriptive statistics for pathway configurational attributes (independent variables) and user movement patterns (the dependent variable) of the study parks. Mean configurational attributes for various parks were compared to determine whether there are statistical differences among these various attributes for the case study parks. The one-way ANOVA (Howell Citation2002) is often used to compare the means of more than two groups when data are normality distributed, while the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis H test (Kruskal Citation1952) is used to compare mean ranks if the assumption of normality distribution is violated. Second, the data from Al-Dawlyia Park and Al-Azhar Park were analysed separately, and Pearson correlation analysis and simple linear regression models were performed to investigate the association between the syntactic variables and user walking behaviour. Third, multiple regression models were performed to explore how the independent variables collectively relate to user movement rates. All the analyses were conducted with the NCSS version 9 software.

4. Results

4.1. Spatial characteristics of the parks

4.1.1. Permeability from main entrance

Justified permeability graphs for the nine parks drawn from the main entrance are provided in . We chose main entrance as a space of origin because all parks are walled and secondary/emergency entrance is typically closed. In neighbourhood parks, the number of interconnected spaces is comparatively few, and the number of topological steps ranges from 7 to 13. Additionally, primary services and play areas are placed far away from the main entrance. In contrast, community and metropolitan parks are distinguished by a greater number of rings of interconnected/communal spaces which integrate other spaces of the structure in ways that increase possibilities for social encounters. While football playgrounds and children’s play areas are usually deeply situated, communal activities that serve various categories of people (e.g., restaurants, food kiosks, cafes, public toilets) are relatively evenly distributed and easily accessible from the main entrance. Furthermore, the existence of more than one entrance in community and metropolitan parks improves access to the deeply placed activities.

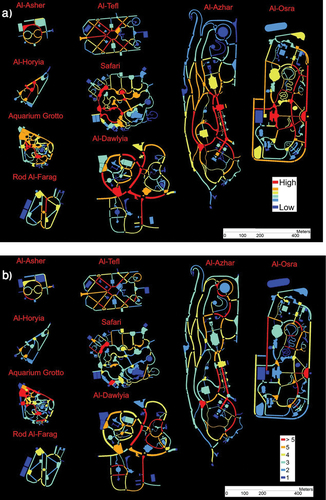

4.1.2. Centrality and connectivity

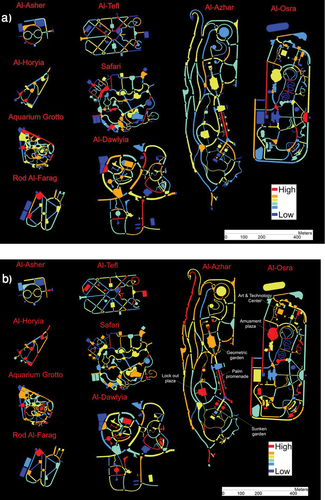

shows global integration and connectivity for the nine parks. The spaces directly connected to the main entrance, along with adjacent circulation spaces, have the highest integration values (shaded in red in ). Food and beverage outlets, such as restaurants and cafes, usually cluster along major pathways and their immediate neighbouring spaces; this clustering gives such pathways prominence for the users. Central plazas, into which various categories of people can enter junctions of paths, also score highly. In contrast, noisy activities and privacy-seeking functions, such as various game activities, including football pitches, children’s play areas and theme parks, are mostly poorly integrated with their surroundings (blue patches). Overall, these activities are placed far away from the main gates. In addition, public services (e.g., prayer areas, public toilets, administration offices) vary in their integration values. For example, administration buildings are usually quite spatially isolated in metropolitan parks while toilets are relatively evenly distributed with regard to entrances. However, in Al-Dawlyia Park, some noisy functional uses, such as the wedding hall, bumper cars and theatre, are placed along highly accessible locations. Likewise, the children’s play area in Al-Tefl Park is positioned in a central location within the park layout. By contrast, all types of activities and services in Al-Osra Park are well-distributed along the park layout to facilitate accessibility from the main and secondary entrances.

Figure 4. Global integration (a) and connectivity (b) for the nine parks. For colour illustrations, please refer to the electronic version of the article.

The connectivity map confirms the local accessibility role of circulation pathways and plazas. These movement spaces are generally locally well-connected and have a range of connectivity from high (above five connections to adjacent spaces) to middle level (three to five connections) (). In contrast, play areas, services and administration offices have low connectivity scores with direct connection to only one or two spaces (dark blue and light blue patches).

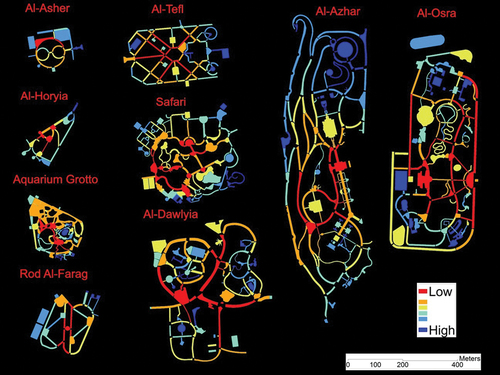

4.1.3. Visually dominant and dominated spaces

shows control and controllability for the nine parks. Central spaces and social gathering places, such as entrances and the intersection points of different paths, are highlighted as highly controlling spaces (red and orange, 4a), from which much of the park can be seen. In contrast, game zones are identified as the least controlling/dominant spaces (blue areas). In addition, the most controllable (visually dominated) spaces include spaces connected to entrances and those adjacent to amusement buildings and food outlets (red and orange, 4b). In Al-Azhar Park, for example, the highly controllable areas are the palm promenade (the main spine), the sunken garden/orchard, and the geometric/formal garden. The main spine is directly connected to the main entry plaza, while the latter three are located before restaurants and cafeterias.

4.1.4. The expected distribution of spaces from a potential origin

shows relativised entropy for the nine parks. As can be seen, major paths and central locations (e.g. entry plazas and nodal areas) through which mobility takes place tend to have lower relativised entropy scores (red and orange colours). This indicates that the spatial layout is less evenly distributed from these spaces as there is more global information. Put simply, starting from these spaces, which serve as the foci of the park, the layout is considerably easy to traverse (Lynch Citation1960). In contrast, the locations that require a higher number of topological steps to encounter other spaces in the system commonly have higher relativised entropy values (blue colours), revealing that there is limited information from these locations (Güney Citation2007).

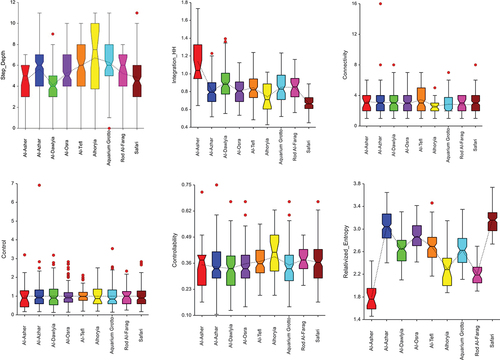

4.1.5. Exploratory syntactic data analysis

The question being asked is: Do statistically significant syntactic differences exist among the nine parks? Side-by-side boxplots of step depth values from gates show relatively overlapping but obviously skewed shapes (). In Al-Dawlyia Park, the average step depth to the gates is 4.11, whereas, in Al-Horyia Park, the pathway segments are 6.7 steps away from the gates, on average. The one-way ANOVA indicated that there is a significant difference in the step depth between the different types of parks, p = .001, with a mean score of 5.88 for neighbourhood parks, 5.31 for community parks, and 5.14 for metropolitan parks.

The Tukey HSD/Tukey-Kramer test indicated that the means of the following pairs are significantly different: neighbourhood park – community park, and neighbourhood park – metropolitan park.

Additionally, side-by-side boxplots of integration values by park name show that seven boxes overlap to some extent with one another but exhibit largely different median lines and ranges with a few mild outliers. In contrast, one box is completely above all boxes, and one more is almost below. This suggests that Al-Asher is the most integrated (Mean = 1.14, Std. Dev. = 0.27), whilst Safari is the deepest and most segregated (Mean = 0.67, Std. Dev. = 0.09). The mean integration values for neighbourhood parks, community parks and metropolitan parks are 0.87, 0.74 and 0.83, respectively. The one-way ANOVA indicated statistically significant differences between the global integration values of the pathways of the three types of parks, p < 0.01. The Tukey HSD test indicated that the means of the following pairs are significantly different: neighbourhood park – community park, neighbourhood park – metropolitan park, and community park – metropolitan park.

The connectivity and control boxplots show overlapping distributions, short boxes, and similar medians with greater number of outliers. Accordingly, the one-way ANOVA test indicated that the averages of all groups were assumed to be equal. In other words, the difference between the averages of all groups is not big enough to be statistically significant.

The controllability distributions have overlapping but highly skewed boxes for all parks. The mean controllability values for the pathway segments in neighbourhood, community and metropolitan parks are 0.3650, 0.3669 and 0.3450, respectively. The Tukey HSD test indicated that the mean of controllability for community parks is significantly higher than that for metropolitan parks, p < 0.01.

Finally, the relativised entropy distributions produce fewer overlapping boxes with different locations, largely different median lines and ranges, and nearly no outliers. In Al-Asher Park, the average relativised entropy is 1.80, whereas, in Safari Park, the pathway segments have an average value of 3.16. Furthermore, the mean relativised entropy values for neighbourhood, community and metropolitan parks are 2.37, 2.96 and 2.90, respectively. The Kruskal–Wallis H test indicated that there is a significant difference in the dependent variable between the different groups, χ2(2) = 238.09, p < .001, with a mean rank score of 198.11 for neighbourhood parks, 554.5 for community parks, 506.69 for metropolitan parks. Dunn’s post hoc test using a Bonferroni corrected alpha of 0.017 indicated that the mean ranks of the following pairs are significantly different: neighbourhood park – community park, and neighbourhood park – metropolitan park.

4.2. User walking behaviour

According to our gate counting 22,812 and 30,528 visitors were observed walking into Al-Dawlyia Park and Al-Azhar Park, respectively, during the entire observation time. The great difference in usage between the two parks may be related to the differences in overall interconnectivity within the city; while Al-Dawlyia Park is located in the far eastern part of Cairo, Al-Azhar Park is positioned in a strategic location within the historic part of the city, and thus its overall connection with adjoining districts is considerably better. In Al-Dawlyia Park, on average, 138 and 405 visitors were observed in the evening period on a weekday and weekend, respectively (compared to 271 and 512 in Al-Azhar Park). The Mann – Whitney U test demonstrated that the numbers of observed visitors differed significantly between weekdays and weekends.

At the walkway segment level, the gross number of observed pedestrians in all observations was calculated to map the usage of each walkway segment. The maximum total number of visitors observed on each walkway segment in Al-Dawlyia Park and Al-Azhar Park were 1746 (Mean = 543) and 2640 (Mean = 783), respectively (). The Mann – Whitney U test demonstrated that more pedestrians were observed on the walkways in Al-Azhar Park than on the walkways in Al-Dawlyia Park, p = 0.035. The pathways were mostly dominated by adults and children, while older adults were underrepresented in the two parks (<2% of park visitors) (Evenson et al. Citation2016; Veitch et al. Citation2022), possibly due to overcrowding, slopped and/or levelled walking paths (Veitch et al. Citation2020). Overall, movement observation data indicate a clearly uneven distribution of visitors in different walkways, where major paths and entrances exhibited a high movement density. Additionally, the areas around water bodies and services were much more visited than elsewhere. However, the results of the Mann – Whitney U test demonstrated that there was no significant difference between pathway segments connected with facilities and other segments in terms of the number of observed visitors.

4.3. Correlation analysis of configurational characteristics with movement observations

In Al-Dawlyia Park, leisure-walking behaviour was positively associated with global integration (see, Appendix A ). This association suggests that more (less) integrated spaces are expected to have more (less) volumes of pedestrian movement (R2 = .32, p < .001, β = 503.02). By contrast, walkways with high relativised entropy received less visitor usage (R2 = .27, p < .001, β = −378.79). The pathway global integration value explained 32.3% of the variability of movement flows, while the pathway relativised entropy value explained 26.8% of the variance in visitor usage. No significant relationship was found between the number of observed walking visitors and pathway step depth, connectivity, control, or controllability. Interestingly, global integration correlated inversely with relativised entropy, r (42) = −0.9428, p < 0.01. This strong association demands a collinearity check in multiple regression analysis. Remarkably, variance inflation factor (VIF) values were greater than 5, which indicates that multicollinearity is a problem in the multiple regression model. Therefore, we removed variables with the greatest VIF values in multiple regression analysis.

In Al-Azhar Park, pathway connectivity and pathway control were positively and moderately associated with the number of observed visitors. The pathway connectivity value explained 17% of the variability of movement flows (R2 = .17, p = .010, β = 105.96), while the pathway relativised control value explained about 18% of the variance in visitor usage (R2 = .18, p = .008, β = 243.43). In contrast, pathway step depth from the main gate was inversely associated with movement rates. Namely, the topologically closer a walkway is to the main entrance, the higher the movement count it has. Moreover, the results of simple regression analysis showed that 28.1% of the variability of foot traffic was explained by step depth. Interestingly, none of the connectivity, control, or step depth was statistically significant in the multiple regression model. The VIF test results indicated a multicollinearity problem between connectivity and control. Therefore, we removed connectivity because it has the greatest VIF value (9.61). Considering only step depth and control as explanatory variables in multiple regression analysis showed that these two variables added significantly to the prediction, p < .05. Specifically, they statistically significantly predicted the number of walking visitors, F(2, 35) = 9.86, p < .0005, R2 = .3603 (see, Appendix A ).

5. Discussion

Given that understanding parks’ spatial composition and visitors’ walking behaviour is essential for park management, it is worthwhile to uncover the underlying spatial logic of a park’s layout and investigate the associations between the use level of a pathway and its configurational attributes. Using space syntax metrics and movement observations, this study indicates that the spatial organisation of Cairene parks is generally regulated by certain design principles, as will be discussed later. Moreover, regression analysis reveals that spatially accessible pathways are more heavily used by park users. The following subsections discuss these findings in detail.

5.1. How are park amenities and leisure facilities spatially distributed?

Space syntax approach is generally useful for studying the configurational properties of park infrastructure. For example, the syntactic measures indicate that community and metropolitan parks are significantly different from neighbourhood parks in terms of step depth to gates and relativised entropy. A potential explanation is that community and metropolitan parks usually have more than one entrance. In contrast, neighbourhood parks usually have only one entrance due to their relatively small size, making them easy to traverse starting from any potential root space. It also explains why neighbourhood parks are more integrated than the other two types of parks. On the other hand, this study found that the layouts of community parks have higher openness and, therefore, are more controllable than those of national parks.

Overall, the spatial distribution of services and leisure facilities within parks reveals that they conform to some distributional principles. For example, the main entrance was the key element of the parks’ spatial organisation. Pathways that are close to the main entrance are spatially more accessible, and, therefore, movement-seeking functions (e.g., restaurants) are arranged around these pathways. In contrast, sports grounds and children’s play areas are usually far from the main entrance to reduce noise levels. However, the effectiveness of this solution in small parks is questioned. In this case, a possible solution is to create a barrier of sufficiently dense evergreen plants along noisy zones to attenuate the noise (Jaszczak et al. Citation2021). However, design principles for minimising user exposure to noise are not fully applied in many parks. For example, in Al-Dawlyia Park, some newly constructed noisy venues, such as the wedding hall, bumper cars and the theatre, are situated in a central location where noise is mostly generated (Xing and Brimblecombe Citation2020); thus, hypothesis 1 is partly supported by our results. This finding reveals that context-dependent issues such as park commercialisation cannot be only explained using the analytical space syntax approach.

It is important to note that the masterplan of Al-Dawlyia Park was originally divided into different sections dedicated to showcasing characteristic landscapes from many countries around the world. While the park still largely keeps that special character, new constructions have not been introduced with that character in mind (Aly and Dimitrijevic Citation2022a). The provision of these new structures and other ticketed leisure activities appears to be a result of park commercialisation, so it is easy to find two parks with the same facilities (Smith Citation2018, Citation2021). For example, cafeterias and ticketed football pitches are primary elements that can be found in most parks. However, this commercial orientation can inherently exclude marginalised segments of society (Biernacka and Kronenberg Citation2018). Following such orientation, Al-Osar Park is a more exclusive park that was designed with a target visitor in mind. Specifically, it is situated in the easternmost part of the city, where the wealthiest people reside (Mohamed and Stanek Citation2021). Consequently, compared with other parks, it is well served with leisure facilities and amenities which are relatively evenly distributed from the gates so that they can be easily reached with fewer topological steps (Hillier Citation1996).

In addition, movement observations indicate that Al-Azhar Park, which is located in a district with higher density and lower income levels, attracts more users than Al-Dawlyia Park, although the latter has more facilities and leisure activities. In other words, park facilities are less likely to be provided based on the order of social needs. Nevertheless, further research is needed to examine inequality in the quantity and quality of park equipment.

5.2. How are leisure walking trips distributed relative to pathways’ configurational attributes?

The results of the syntactic analysis suggest that configurational attributes influence visitor movement behaviour within a park. In Al-Dawlyia Park, spaces with the highest movement rates appeared near the main gates and water bodies, as these are the most globally integrated spaces in the park. This is in line with previous studies that examined walking behaviour in urban environments (Hillier et al. Citation1993; Mohamed Citation2016) and urban parks (Zhai and Baran Citation2016; Zhai, Korça Baran, and Wu Citation2018; Zhang, Lian, and Xu Citation2020), which suggests that routes with high integration values are associated with more foot traffic. In contrast, this study indicates that visitors use walkway segments with low relativised entropy values more. These segments serve as the foci of the park; therefore, visitors can easily traverse the park layout starting from those places (Lynch Citation1960).

On the other hand, in Al-Azhar Park, pathway segments with high control values exhibit more walking, as users must traverse these segments to reach neighbouring pathways. This finding is fully supported by previous studies in that walkway segments with high control values have significant control over the access to adjacent routes (Baran, Rodríguez, and Khattak Citation2008; Zhai and Baran Citation2016; Zhai, Korça Baran, and Wu Citation2018). Our results also indicate that locally connected spaces have neighbouring spaces and, in turn, more users than elsewhere. Additionally, spaces with lower step depth from the main entrances are more likely to have more visitors than other spaces. However, this study did not detect any relationship between pathway integration and movement flow in Al-Azhar Park. One possible explanation is that the landscape design of Al-Azhar Park fosters leisure walking. Nevertheless, the link between pathway integration and movement rate needs to be further explored in other parks.

Altogether, hypothesis 2, which indicates a direct relationship between pathways’ configurational characteristics and visitors’ spatial distribution, is partly supported by the results. Overall, global integration, step depth, relativised entropy, control and connectivity are more likely to be good predictors of walking behaviour. However, the relationship between these configurational attributes and visitor movement flows seem to be complex, particularly in the context of urban parks, where different visitors have various needs and preferences. The findings of this study have implications for pathway network and movement flow predictions in the management and design of urban parks. The following subsection summarises these implications.

5.3. Practical implications

Our findings suggest practical guidelines for landscape planners, designers and managers to support park management and foster visitor leisure walking and physical activity. First, the park layout can be improved by placing important points of interest and services (e.g., food outlets and public toilets) along spatially accessible pathways to facilitate visitor usage. In contrast, noisy activities, such as children playground and wedding hall, can be placed in isolated zones that are far away from the main entrance to reduce noise levels and maintain family privacy. Second, park amenities and leisure facilities should be provided on the basis of community needs and park size rather than policy interest agendas, which usually treat public parks as “assets” that can be hired out for commercial purposes (Churchill, Crawford, and Barker Citation2018). For example, a wedding hall might be provided within metropolitan parks rather than neighbourhood parks. Third, managers should better cope with pathways with high control and integration values where overcrowding is most likely to develop, particularly after COVID-19. They should also pay attention to safety issues on poorly accessible pathways with low foot traffic. Finally, as space syntax can measure the configurational characteristics of urban parks, designers can use it to improve their plans and ideas accordingly.

5.4. Limitations and future work

This study has several limitations. First, the scope of this work has been confined to the objective measures of syntactic accessibility based solely on the configurational attributes of the pathway network. However, it is important to acknowledge that conducting interviews with the people responsible for managing parks in Cairo could be very helpful in supporting (or contradicting) our findings (Smith Citation2018, Citation2021). Second, this study only considered the topological position of a pathway segment within a wider pathway network as it relates to the number of leisure walking trips. There are numerous other pathway characteristics at play that affect walking behaviour that could be considered in future research, including shading, pathway width, visual connection with water (Zhai, Korça Baran, and Wu Citation2018), as well as pathway pavements and park facilities and amenities (Kaczynski, Potwarka, and Saelens Citation2008). Third, user walking behaviour was only examined in metropolitan parks. Future research should also investigate visitors’ spatial distribution in other types of parks. Put differently, further work is needed to understand how park type influences how people use park walkways and leisure facilities. Also, studying cases from other contexts can positively contribute to the literature on park planning and management. Further, utilising GPS tracking can provide a better understanding of users’ behaviour by recording more information on visitors’ walking distance and length of stay (Zhang, Lian, and Xu Citation2020). Additionally, future research can further examine how pathway features relate to the different needs and preferences of different social groups. Finally, further research should address the issue of park facilities and amenities in relation to social needs.

6. Conclusion

This study provided insights into the organisational logic of park infrastructure and the relationship between pathway configurational characteristics and leisure walking behaviour. Space syntax analysis, field observations, and regression analysis were performed to describe and analyse spatial layouts of public parks in Greater Cairo and to investigate the attraction of various spatial attributes to users. The results showed that the main entrance was an integral element of the parks’ spatial composition. Walkways close to the main entrance are syntactically more accessible, and therefore, facilities and amenities that serve the needs of diverse visitors tend to cluster around these walkways. In contrast, activities that serve particular age groups (e.g., football pitches and children’s play areas) are most commonly positioned far away from the main entrance to provide privacy and reduce noise levels. However, constructions that were not originally part of the park layout were placed randomly based on space availability. Such constructions were introduced to generate commercial revenues. Regression analysis showed that global integration, connectivity and degree of control over accessing neighbouring walkways related positively to movement flows on each walkway segment. Park managers should therefore consider efficient strategies to cope with overcrowding that is most likely to develop along pathways with high control, connectivity and/or integration values. They can also place facilities that serve the diverse users along such pathways. Meanwhile, managers should also monitor pathways with low global integration, connectivity and/or control, as these pathways tend to be less used and may have safety issues. For visitors who prefer to enjoy the silence and experience nature and calm, designers can create settings that foster calmness by placing spaces for relaxing around pathways with low global integration, connectivity and/or control. Such considerations could serve diverse users’ needs and preferences and help park managers better maintain and manage park facilities and amenities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Abdelbaseer A. Mohamed

Abdelbaseer A. Mohamed is a researcher in residence at Social-Ecological Systems Analysis Lab, Faculty of Economics and Sociology, University of Lodz. His research explores society-space interactions, in particular from the perspective of urban morphology. He is a space syntax expert with over 10 years of experience.

Jakub Kronenberg

Jakub Kronenberg is an Associate professor at the University of Lodz, Faculty of Economics and Sociology, at the Social-Ecological Systems Analysis Lab. He is in the board of the Sendzimir Foundation that promotes sustainable development in Poland. He gained international research experience in France, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the Kyrgyz Republic. Jakub’s research focuses on economy–society–environment interactions, in particular from the perspective of ecological economics.

Edyta Łaszkiewicz

Edyta Łaszkiewicz is an Associate Professor at the University of Lodz (Poland), Social-Ecological Systems Analysis Lab. Her scientific interests focus on the interactions between social, economic and environmental processes, especially environmental valuation, urban green space provision, environmental justice and urban planning. Her research is multidisciplinary, linking human geography, economics and ecology. Edyta has published more than 30 articles in journals of high academic repute, such as Urban Forestry and Urban Greening, Ecosystem Services, Ecological Economics, Cities, Landscape and Urban Planning, Ecology & Society

References

- Aly, D., and B. Dimitrijevic. 2022a. “Assessing Park Qualities of Public Parks in Cairo, Egypt.” Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARCH-03-2022-0073.

- Aly, D., and B. Dimitrijevic. 2022b. “Public green space quantity and distribution in Cairo, Egypt.” Journal of Engineering and Applied Science 69 (1): 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s44147-021-00067-z.

- Baran, P. K., D. A. Rodríguez, and A. J. Khattak. 2008. “Space Syntax and Walking in a New Urbanist and Suburban Neighbourhoods.” Journal of Urban Design 13 (1): 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574800701803498.

- Barros, C., B. Moya-Gómez, and J. Gutiérrez. 2020. “Using Geotagged Photographs and GPS Tracks from Social Networks to Analyse Visitor Behaviour in National Parks.” Current Issues in Tourism 23 (10): 1291–1310. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1619674.

- Bedimo-Rung, A. L., A. J. Mowen, and D. A. Cohen. 2005. “The Significance of Parks to Physical Activity and Public Health: A Conceptual Model.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 28 (2 Suppl 2): 159–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.024.

- Biernacka, M., and J. Kronenberg. 2018. “Classification of Institutional Barriers Affecting the Availability, Accessibility and Attractiveness of Urban Green Spaces.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 36:22–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.09.007.

- Biernacka, M., J. Kronenberg, and E. Łaszkiewicz. 2020. “An Integrated System of Monitoring the Availability, Accessibility and Attractiveness of Urban Parks and Green Squares.” Applied Geography 116:102152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2020.102152.

- Can Traunmüller, I., İ. İ̇nce Keller, and F. Şenol. 2023. “Application of Space Syntax in Neighbourhood Park Research: An Investigation of Multiple Socio-Spatial Attributes of Park Use.” Local Environment 28 (4): 529–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2022.2160973.

- CAPMAS (Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics). (2017). Census of Egypt 2017. Nata’ij Al-Ta’dad Al-’am Li-L-Sukkan Wa-Al-Munsh’at [Headcounts for Census Enumerations Districts (Shiyakhat and Qura) of Egypt’s Governorates]. https://www.capmas.gov.eg/Pages/Publications.aspx?page_id=7195&Year=8260.

- Churchill, D., A. Crawford, and A. Barker. 2018. “Thinking Forward Through the Past: Prospecting for Urban Order in (Victorian) Public Parks.” Theoretical Criminology 22 (4): 523–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480617713986.

- Dawes, M. J., M. J. Ostwald, and J. H. Lee. 2021. “Examining Control, Centrality and Flexibility in Palladio’s Villa Plans Using Space Syntax Measurements.” Frontiers of Architectural Research 10 (3): 467–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2021.02.002.

- Evenson, K. R., S. A. Jones, K. M. Holliday, D. A. Cohen, and T. L. McKenzie. 2016. “Park Characteristics, Use, and Physical Activity: A Review of Studies Using SOPARC (System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities).” Preventive Medicine 86:153–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.02.029.

- Güney, Y. I. 2007. Analyzing Visibility Structures in Turkish Domestic Spaces. Sixth International Space Syntax Symposium, 038.01–038.12. Istanbul.

- Hillier, B. 1996. Space is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hillier, B., and J. Hanson. 1984. The Social Logic of Space. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hillier, B., A. Penn, J. Hanson, T. Grajewski, and J. Xu. 1993. “Natural Movement: Or, Configuration and Attraction in Urban Pedestrian Movement.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 20 (1): 29–66. https://doi.org/10.1068/2Fb200029.

- Howell, D. C. 2002. Statistical Methods for Psychology. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury/Thomson Learning. http://archive.org/details/statisticalmetho0000howe.

- Jaszczak, A., N. Małkowska, K. Kristianova, S. Bernat, and E. Pochodyła. 2021. “Evaluation of Soundscapes in Urban Parks in Olsztyn (Poland) for Improvement of Landscape Design and Management.” Land 10 (1): 66. Article 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10010066.

- Kaczynski, A. T., L. R. Potwarka, and B. E. Saelens. 2008. “Association of Park Size, Distance, and Features with Physical Activity in Neighborhood Parks.” American Journal of Public Health 98 (8): 1451–1456. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2007.129064.

- Koch, D. 2004. Spatial Systems as Producers of Meaning: The Idea of Knowledge in Three Public Libraries. Stockholm: KTH School of Architecture.

- Kruskal, W. H. 1952. “A Nonparametric Test for the Several Sample Problem.” Annals of Mathematical Statistics 23 (4): 525–540. https://doi.org/10.1214/aoms/1177729332.

- Liu, W., Q. Chen, Y. Li, and Z. Wu. 2021. “Application of GPS Tracking for Understanding Recreational Flows within Urban Park.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 63:127211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127211.

- Lynch, K. 1960. The Image of the City. Vol. 11. Cambridge: MIT press.

- Mahmoud, D. 2017. Perception of Urban Landscape in Greater Cairo: Case Study Al-Azhar, Giza and Andalus Parks. [Faculty of Regional and Urban Planning, Cairo University]. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13004.92809.

- Mohamed, A. A. 2016. “People’s Movement Patterns in Space of Informal Settlements in Cairo Metropolitan Area.” Alexandria Engineering Journal 55 (1): 451–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2015.07.018.

- Mohamed, A. A., J. Kronenberg, and E. Łaszkiewicz. 2022. “Transport Infrastructure Modifications and Accessibility to Public Parks in Greater Cairo.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 73:127599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127599.

- Mohamed, A. A., and D. Stanek. 2021. “Income Inequality, Socio-Economic Status, and Residential Segregation in Greater Cairo: 1986–2006.” In Urban Socio-Economic Segregation and Income Inequality: A Global Perspective, edited by M. van Ham, T. Tammaru, R. Ubarevičienė, and H. Janssen, 49–69. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64569-4_3.

- Nam, J., and H. Kim. 2014. “The Correlation Between Spatial Characteristics and Utilization of City Parks: A Focus on Neighborhood Parks in Seoul, Korea.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 13 (2): 515–522. https://doi.org/10.3130/jaabe.13.515.

- Nantel, J., M.-E. Mathieu, and F. Prince. 2010. “Physical Activity and Obesity: Biomechanical and Physiological Key Concepts.” Journal of Obesity 2011:e650230. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/650230.

- National Academy of Engineering. 2013. Protecting National Park Soundscapes. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18336.

- Niță, M. R., D. L. Badiu, D. A. Onose, A. A. Gavrilidis, S. R. Grădinaru, I. I. Năstase, and R. Lafortezza. 2018. “Using Local Knowledge and Sustainable Transport to Promote a Greener City: The Case of Bucharest, Romania.” Environmental Research 160:331–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2017.10.007.

- Polat, A. T., and A. Akay. 2015. “Relationships Between the Visual Preferences of Urban Recreation Area Users and Various Landscape Design Elements.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 14 (3): 573–582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2015.05.009.

- Rankovič, N., and L. Keča. 2014. “Influence of Selected Factors on Number of Visitors in National Park Đerdap.” Agriculture and Forestry 60 (3): 123–136. https://www.academia.edu/48622504/Influence_of_Selected_Factors_on_Number_of_Visitors_in_National_Park_%C4%90erdap.

- Şenol, F., and İ. Atay Kaya. 2021. “GIS-Based Mappings of Park Accessibility at Multiple Spatial Scales: A Research Framework with the Case of Izmir (Turkey).” Local Environment 26 (11): 1379–1397. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2021.1983793.

- Shatu, F., T. Yigitcanlar, and J. Bunker. 2019. “Shortest Path Distance Vs. Least Directional Change: Empirical Testing of Space Syntax and Geographic Theories Concerning Pedestrian Route Choice Behaviour.” Journal of Transport Geography 74:37–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.11.005.

- Smith, A. 2018. “Paying for Parks. Ticketed Events and the Commercialisation of Public Space.” Leisure Studies 37 (5): 533–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2018.1497077.

- Smith, A. 2021. “Sustaining Municipal Parks in an Era of Neoliberal Austerity: The Contested Commercialisation of Gunnersbury Park.” Environment & Planning A: Economy & Space 53 (4): 704–722. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X20951814.

- Tannous, H. O., M. Major, and R. Furlan 2020, December 10. “Accessibility of Green Spaces within the Spatial Metropolitan Network of Doha, State of Qatar.” 56th ISOCARP Virtual World Planning Congress, Doha, Qatar.

- Thomson, R. C. 2004. “Bending the Axial Line: Smoothly Continuous Road Centre-Line Segments as a Basis for Road Network Analysis.” Proceedings of the 4th International Space Syntax Symposium, .50.1–.50.10. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Bending%20the%20axial%20line%3A%20Smoothly%20continuous%20road%20centre-line%20segments%20as&author=R.C.%20Thomson&publication_year=2004.

- Turner, A. 2004. Depthmap 4: A Researcher’s Handbook. Bartlett School of Graduate Studies, University College London. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/2651/.

- van Nes, A., and C. Yamu. 2021. Introduction to Space Syntax in Urban Studies. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-59140-3.

- Vaughan, L., and T. Grajewski. 2001. Space Syntax Observation Manual. London: University College London (UCL).

- Veitch, J., K. Ball, E. Rivera, V. Loh, B. Deforche, K. Best, and A. Timperio. 2022. “What Entices Older Adults to Parks? Identification of Park Features That Encourage Park Visitation, Physical Activity, and Social Interaction.” Landscape and Urban Planning 217:104254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104254.

- Veitch, J., E. Flowers, K. Ball, B. Deforche, and A. Timperio. 2020. “Designing Parks for Older Adults: A Qualitative Study Using Walk-Along Interviews.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 54:126768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126768.

- Veitch, J., L. Rodwell, G. Abbott, A. Carver, E. Flowers, and D. Crawford. 2021. “Are Park Availability and Satisfaction with Neighbourhood Parks Associated with Physical Activity and Time Spent Outdoors?” BMC Public Health 21 (1): 306. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10339-1.

- Xing, Y., and P. Brimblecombe. 2020. “Traffic-Derived Noise, Air Pollution and Urban Park Design.” Journal of Urban Design 25 (5): 590–606. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2020.1720503.

- Zhai, Y., and P. K. Baran. 2016. “Do Configurational Attributes Matter in Context of Urban Parks? Park Pathway Configurational Attributes and Senior Walking.” Landscape and Urban Planning 148:188–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.12.010.

- Zhai, Y., P. Korça Baran, and C. Wu. 2018. “Can Trail Spatial Attributes Predict Trail Use Level in Urban Forest Park? An Examination Integrating GPS Data and Space Syntax Theory.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 29:171–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2017.10.008.

- Zhai, Y., D. Li, C. Wu, and H. Wu. 2021. “Urban Park Facility Use and Intensity of seniors’ Physical Activity – an Examination Combining Accelerometer and GPS Tracking.” Landscape and Urban Planning 205:103950. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103950.

- Zhang, T., Z. Lian, and Y. Xu. 2020. “Combining GPS and Space Syntax Analysis to Improve Understanding of Visitor Temporal–Spatial Behaviour: A Case Study of the Lion Grove in China.” Landscape Research 45 (4): 534–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2020.1730775.

Appendix A

Table A1. The demographic characteristics of the neighbourhoods within which the selected parks are located based on CAPMAS (Citation2017), Mohamed and Stanek (Citation2021), and Aly and Dimitrijevic, Citation(2022b).

Table A2. Space assessment predictors used in this study.

Table A3. Pearson correlation analysis between configurational attributes and movement observations.

Table A4. Multiple regression analysis with the number of observed walking visitors and predictor variables in Al-Azhar park.