?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The relationship between motivation and productivity is a crucial concern for managers and must be analyzed based on sectoral differences. This study aims to explore the differences in motivation and productivity among staff architects in the public and private sectors in Turkey and to examine the effects of motivational tools on their productivity. The study compares three fundamental motivational tools: economic, psycho-social, and organizational-managerial. A quantitative research method was employed, and a survey was conducted among 132 staff architects working in the public and private construction sectors in Antalya, a significant city that contributes to Turkey’s economy. T-tests and correlation analysis were conducted to test the hypotheses. The results of the study revealed significant variations in the perception of motivational tools between the two sectors, indicating distinct experiences for staff architects. Economic fluctuations in Turkey were identified as a potential explanation for the differences in the perception of economic tools. Additionally, significant disparities were observed in the perception of psycho-social and organizational/managerial tools, highlighting the contrasting nature of these factors across sectors. The study’s findings determined that while organizational and managerial motivational tools were effective in increasing the productivity of staff architects in the public sector, the productivity of staff architects in the private sector could be enhanced by psycho-social motivational tools. This study contributes to the existing knowledge by uncovering disparities in perceptions and impacts of motivational tools between public and private sectors. It emphasizes the significance of considering contextual factors and industry-specific dynamics when examining the motivation-productivity relationship in the construction industry. The findings have practical implications for managers and policymakers in both sectors, highlighting the need to tailor incentive strategies to sector-specific needs.

1. Introduction

Ensuring employee motivation is considered a significant issue in today’s organizations (Alagele Citation2020; Kalogiannidis Citation2021; Ramirez Citation2020). Motivation is the individual’s actions and works towards the goals to achieve the planned goals due to an effect (Reeve Citation2016), and it has a direct impact on employees. Prioritizing employee motivation is crucial as it leads to increased productivity (Gurcanli et al. Citation2021; Manoharan et al. Citation2022a; Setiawan et al. Citation2021) and job satisfaction (Pancasila, Haryono, and Sulistyo Citation2020) within an organization. Therefore, managers who aim to enhance employee motivation and productivity (Bawa Citation2017; Kencana, Asmalah, and Munadjat Citation2021) must select the most suitable economic, psycho-social, or organizational and managerial tools (Özkeser Citation2019). Productivity, as a significant factor related to motivation, can be defined as efficient utilization of resources (labor, capital, land, materials, energy, knowledge, time) in the production of goods and services (Jarkas and Haupt Citation2015; Momade and Hainin Citation2018; Momade et al. Citation2021; Prokopenko Citation2011; Shiru et al. Citation2020). It also aims to save money by effectively utilizing resources, including human resources (Prokopenko Citation2011).

The construction sector is one of the industries where motivation tools are essential for ensuring productivity. Enhancing labor productivity can have a significant positive impact on the construction sector (Al Jassmi et al. Citation2019; Gurcanli et al. Citation2021; Van Tam et al. Citation2021). Furusaka et al. (Citation2002) have drawn attention to the relationship between client satisfaction and services provided by the architects. In this context, increasing the motivation of architects, who play a crucial role in both the design and construction processes, is an issue that employers should prioritize to enhance productivity.

The relationship between motivation and productivity has become increasingly significant today. Numerous studies in the literature support this relationship (Aghayeva and Ślusarczyk Citation2019; Bawa Citation2017; Hamid and Younus Citation2021; Hanaysha and Majid Citation2018; Putra and Mujiati Citation2022; Zhang et al. Citation2020). While some studies have explored this relationship in the construction sector (Al-Abbadi and Agyekum-Mensah Citation2022; Pancasila, Haryono, and Sulistyo Citation2020; Saddiya and Aziz Citation2022; Tam, Watanabe, and Hai Citation2022; Van Tam Citation2021), particularly regarding construction workers (Johari and Jha Citation2020; Kazaz, Manisali, and Ulubeyli Citation2008), the relationship between motivation and productivity has not yet been adequately investigated in terms of staff architects. Architects often work in various positions throughout their careers. Especially in developing countries such as Turkey, architects predominantly work as staff architects in design offices or construction sites to secure financial stability. The economic conditions in Turkey lead many architects to prefer working as staff architects. According to a report by the Ankara Chamber of Architects, % 94.22 of staff architects in Turkey work in the private sector (Url- 1 Citation2022). Staff architects play a critical role in both the design and construction phases of a project. Anderson (Citation1995) defined a staff architect as an individual or a group with professional qualifications and a salary in planning and design, responsible for reporting to a supervisor.

Ensuring the motivation and productivity of staff architects is crucial for achieving the goals of construction projects. While numerous studies have examined the impact of motivation on productivity in the construction sector, the majority of the research have focused on workforce issues at construction sites. Little attention has been given to architects as employees working in either the public or private sector. To address this gap, this study emphasizes the importance of understanding the relationship between work motivation and productivity specifically among staff architects. The aim of this study is to examine the differences in motivation and productivity among staff architects in the public and private sectors in Turkey, as well as to explore the impact of motivational tools on their productivity.

In the scope of the study, a survey was conducted among 132 staff architects in the public and private construction sector in Antalya, a major city contributing to Turkey’s economy. The results of the study are expected to attract international attention, particularly in developing countries. According to Kazaz and Ulubeyli (Citation2007), improved productivity is crucial in developing countries, as capital alone is insufficient for generating wealth or starting businesses. Understanding the motivation and productivity dynamics of staff architects is vital for effective management and sustainable development of the construction industry. By examining the differences between these sectors, it was aimed to provide a comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms that influence architect performance. This knowledge can serve as a foundation for developing customized strategies and interventions to optimize staff architect motivation and productivity. The findings of this study have the potential to provide valuable insights and practical implications for construction companies, public authorities, and policymakers in the construction industry, particularly in developing countries like Turkey.

2. Background

2.1. Importance of motivation and motivational tools

Motivation, a psychological and sociological concept, holds significant importance for managers at all levels. When examining the various definitions of motivation (McCoach and Flake Citation2018; Sitopu, Sitinjak, and Marpaung Citation2021), it becomes evident that personal expectations play a crucial role in achieving the objectives associated with motivation. It is a process that aims to satisfy by fulfilling their personal expectations, thereby prompting them to act, ultimately leading to increased organizational success. Conversely, an unmotivated employee unlikely to work productively. Therefore, labor motivation can be defined as a key factor in maximizing workers’ productivity (Kazaz, Manisali, and Ulubeyli Citation2008).

A number of studies have identified factors that impact motivation in the construction sector across various developing countries, such as Kuwait (Soliman and Altabtai Citation2023), Iran (Hajarolasvadi, Aghaz, and Shahhosseini Citation2022), Indonesia (Hansen, Rostiyanti, and Nafthalie Citation2020), and Nigeria (Oloruntoba and Olanipekun Citation2021). Sugathadasa et al. (Citation2021) stated that workers in developed countries exhibit higher levels of motivational needs compared to those in developing countries. Factors contributing to the lack of motivation in developing countries are often identified, including salary (Phan et al. Citation2020; Soliman and Altabtai Citation2023), safety needs (Soliman and Altabtai Citation2023; Sugathadasa et al. Citation2021), promotion opportunities (Hajarolasvadi, Aghaz, and Shahhosseini Citation2022), among others.

Motivation is crucial for the employees and provides several benefits to them. It creates a suitable environment for employees to achieve their basic economic and social needs. Furthermore, it enables employees to engage in a positive competitive environment by exploring opportunities for skill improvement. As a result, it is anticipated that the employee satisfaction, a desired outcome, will be achieved (Şimşek, Çelik, and Akgemci Citation2014). If a manager aims to achieve organizational success, they must prioritize, employee satisfaction and increase motivation. In this context, two important aspects of motivation should be considered by managers. Firstly, motivation is a personal circumstance, implying that what motivates one employee may not necessarily motivate others. Secondly, motivation can only be observed through human behavior (Koçel Citation1995).

Ensuring organizational motivation has mutual effects on both managers and employees (Çolak Alsat Citation2016). Managers have a significant opportunity to enhance organizational integration and productivity by acquiring sufficient knowledge and experience with motivational tools. In this way, the manager will discover the factors that may create more desire to work for the employees and satisfy their needs as much as possible (Sabuncuoğlu and Vergiliel Tüz Citation2008). The most important point about motivational tools is that they vary from person to person. In other words, motivational tools do not have the same effect on every employee. These disparities can be attributed to various factors, such as individuals’ characteristics, cultural backgrounds, educational levels, needs, and life expectations.

Motivational tools employed within organizations can be classified into three main groups: economic, psycho-social, and organizational and managerial. Economic tools are defined as salary, implementation of bonuses, profit sharing, monetary rewards, and social security and retirement benefits. Psycho-social tools include factors such as independent work opportunities, recognition and status, respect for private work- life balance, appreciation and accountability for business success, social activities, environmental compliance, suggestion system, and disciplinary measures. Organizational and managerial tools include objective setting, equal distribution of authority and responsibility, participation in decision-making processes, promotion opportunities, provision of professional development, organizational flexibility, flexible working conditions, improvement of physical work environment, positive management approach, and transparent negotiation methods (Selen Citation2016).

2.2. Importance of productivity, and factors affecting productivity

Organizations, being economic entities, have the primary objective of generating profits. Therefore, managers employ various methods to increase profitability. Among these methods, enhancing productivity has emerged as a fundamental principle that managers consistently prioritize to achieve higher profitability (Jarkas, Radosavljevic, and Wuyi Citation2014). In both the private and public sectors, which are profit- oriented organizations, the pursuit of increased productivity is crucial for attaining success. Moreover, it plays a pivotal role in fostering growth within the construction sector.

Developing an understanding of the key factors that impact labor productivity can assist in the development of strategies to reduce inefficiencies and effectively manage construction labor forces (Hamza et al. Citation2022), particularly in developing countries. Several existing studies have examined the factors affecting productivity in developing countries, including Gana (Apraku et al. Citation2020), Qatar (Jarkas, Radosavljevic, and Wuyi Citation2014; Momade and Hainin Citation2019), Jordan (Al-Abbadi and Agyekum-Mensah Citation2022), Azerbaijan (Aghayeva and Ślusarczyk Citation2019), and Sri Lanka (Manoharan et al. Citation2022b, Citation2023). Major factors such as manpower factors (Hamza et al. Citation2022), management factors (Hamza et al. Citation2022), motivational factors (Aghayeva and Ślusarczyk Citation2019; Al-Abbadi and Agyekum-Mensah Citation2022; Momade and Hainin Citation2019; Van Tam Citation2021), work condition factors, project factors, and external factors (Van Tam et al. Citation2021) have been identified as significant determinants of worker productivity.

According to Eren (Citation1984), productivity involves choosing the most cost-effective solution when two options yield the same result. Efficiently utilizing resources, which is the fundamental principle of organizations, leads to increased profitability through enhanced productivity. Arditi (Citation1985) defines high productivity as the intensive and/or efficient use of scarce resources, transforming input into output and generating greater profit. Sabuncuoğlu and Tokol (Citation2005) explain productivity as the ratio of the physical output obtained from the production activities to the physical inputs invested in those activities. Aytürk (Citation2010) describes productivity in management as the rational, balanced, effective, and economical use of resource; the productive and efficient execution of administrative functions; and the effective and efficient management of employees. These various definitions associate productivity with aspects such as products, costs, resources, and management. However, at its core, productivity in an organization is directly related to labor.

Productivity, closely tied to a country`s level of development, is an issue of significant emphasis for the public and the private sectors. The importance of productivity in achieving societal and individual welfare cannot be denied. Increasing productivity directly contributes to improving living standards and serves as the sole source of real economic development, social progress, and an elevated standard of living (Prokopenko Citation2011). Therefore, it is crucial to conduct research to enhance productivity in underdeveloped and developing countries.

The primary responsibilities of the managers include design, coordinate, monitoring, and efficiently managing the production process by acquiring all the necessary production factors. Thus, productivity holds significance in measuring and evaluating the performance and success of managers. Additionally, considering that the technical and financial aspects of management are interconnected with managers often focusing primarily on technical matters, productivity becomes a valuable tool for managers to address both physical and financial issues within the organization (Aslan Citation2014).

It should be acknowledged that productivity growth and effective use of utilization of available resources are the only means for a society to progress. Identifying the factors impeding productivity growth and taking appropriate measures to address them are crucial for managerial success. Prokopenko et al. (Citation2011) classifies factors influencing productivity into two categories: internal and external factors. Internal factors are categorized as hard factors and soft factors, while external factors encompass structural adjustment, natural resources, government, and infrastructure. Since organizations have more control over internal factors compared to external factors, they can be managed more effectively.

3. Materials and methods

Business success in a capitalist system relies not only on delivering high-quality products but also on continually increasing productivity to maintain competitiveness. This principle is particularly relevant in the construction sector, where companies constantly assess their methods and technologies to achieve greater value-added outputs with fewer resources (Bernold and AbouRizk Citation2010).

The primary objective of enhancing employee motivation is to ensure that the employees work willingly, productively, and effectively. Despite overall job satisfaction, one of the main reasons for the lack of productivity among employees in organizations is often a misalignment of motives (Karatepe Citation2005). In this context, managers should identify and utilize motivational tools to harness the positive impact of motivation on productivity (Örücü and Kanbur Citation2008). Hence, employee motivation relies on the convergence of organizational goals and employee objectives (Erkut and MacLean Citation1992). When this convergence occurs, a relationship between motivation and productivity becomes apparent (Selen Citation2016). A work environment that meets the needs, demands, and expectations of employees enhances both employee job satisfaction and organizational productivity (Karatepe Citation2005). Unmotivated employees are unlikely to be productive, and the consequences of employee absenteeism or dismissal have negative effects on organizational productivity.

Just like any other sectors, there is a close correlation between motivation and productivity in the construction industry. Architectural offices, public institutions, and construction sites are all businesses driven by economic concerns, where products are created and delivered. In these workplaces, the main objective is to complete projects with accuracy and high quality in a timely manner, involving all employees. While many factors influence productivity, human labor undoubtedly stands out as the most significant factor. For many, effective resource utilization is often perceived as technological and institutional development. However, holistic human development frequently contributes more to overall productivity growth (Prokopenko Citation2011). When assessing the factors affecting productivity, paying due attention to, and evaluating the human factor is a crucial step in saving time. Consequently, increasing human labor is vital and establishes a link between motivation and productivity through the application of motivational tools.

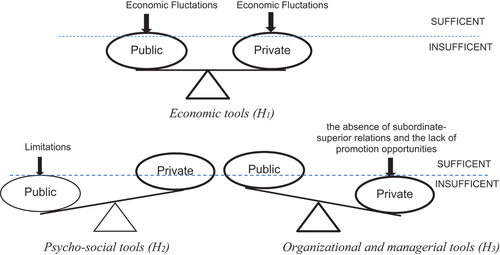

Etymologically, motivation pertains to what “moves” people to take action. Motivation theories specifically focus on what both energizes and drives behaviour (Ryan and Deci Citation2017). However, some studies suggest that the effects of the motivational tools differ between the public and private sectors (Brewer and Brewer Citation2011; Buelens and Van den Broeck Citation2007; Bunchoowong Citation2015). This study was conducted to highlight the difference between staff architects’ motivation and productivity in the public and private sectors. The relationship between motivation and productivity can be defined as productivity being directly related to motivation, and motivation, in turn, being connected to productivity (Kazaz, Manisali, and Ulubeyli Citation2008). However different motivational tools have varying impacts on productivity. Therefore, the differences between motivational tools` impact on the productivity of staff architects in public and private sectors aimed to be highlighted. In line with the outlined aim, two research questions have been formulated. The first research question seeks to determine whether there is a difference in staff architects` perceptions of the sufficiency of motivational tools in their job. The hypotheses related to the first research question are outlined below.

H1:

There is a significant difference in the perceptions of staff architects in the public and private sectors regarding the availability of economic motivational tools in their work.

H2:

There is a significant difference in the perceptions of staff architects in the public and private sectors regarding the availability of psycho-social motivational tools in their work.

H3:

There is a significant difference in the perceptions of staff architects in the public and private sectors regarding the availability of organizational and managerial motivational tools in their work.

The second research question is whether there are any differences regarding the impact of motivational tools on staff architects` productivity. The motivational tools in organizations were analysed across three groups (1) economical, (2) psycho-social, and (3) organizational and managerial. To address these questions in relation to the three motivational tool categories, additional hypotheses for the research were defined as follows:

H4:

There is a significant difference in the perceptions of staff architects working in the public and private sectors regarding the impact of economical motivational tools on their productivity.

H5:

There is a significant difference in the perceptions of staff architects working in the public and private sectors regarding the impact of psycho-social motivational tools on their productivity.

H6:

There is a significant difference in the perceptions of staff architects working in the public and private sectors regarding the impact of organizational and managerial motivational tools on their productivity.

3.1. Research design

The current study used a quantitative research method. According to Jean Lee (Citation1992), the quantitative research method was usually seen as the conventional method in organization studies. A questionnaire survey was adopted by Selen (Citation2016) to test the hypotheses. The questionnaire consists of three main parts. In the first part, personal information was obtained with five questions such as gender, age, education level, marital status, and experience in architectural design and construction sectors. In the second part, the opinions of the employees regarding the presence of motivational tools in their work were determined. It sought to reveal the status of architects working in the public and private sectors. In this part, motivational tools were divided into three main sections (1) economical tools, (2) psycho-social tools, and (3) organizational and managerial tools. Participants were asked 20 questions with “yes” or “no” options, enabling the demonstration of opinion differences arising from varying working conditions in the public and private sectors (H1, H2, H3).

In the last part, it was aimed to determine the effects of motivation on productivity (H4, H5, H6). Participants were presented with a set of questions regarding the impact of motivational tools` on their productivity. Economical tools included salary, implementation of premiums, profit- sharing, monetary rewards, social security and retirement options. Psycho-social tools encompassed independent work opportunities, recognition of workers` importance and status, respect for private life, appreciation, accountability for business success, social activities, environmental compliance, and punishment. Organizational and managerial tools were listed as targeting, authority and responsibility equality, participation in decision- making, promotion opportunities, professional development provisions, organizational flexibility, flexible working conditions, improvement of physical conditions, positive management approach, and others (Selen Citation2016). This part consisted of total 40 questions. The conceptual framework of the research and the hypotheses were summarized in .

3.2. Participants

The snowball sampling method was used to test the hypotheses. Snowball sampling is used to gather information for accessing specific groups of people (Naderifar, Goli, and Ghaljaie Citation2017), and offers various advantages when compared to alternative methods that aim to achieve similar objectives (Audemard Citation2020; Burt Citation1984; Huckfeldt, Sprague, and Levine Citation2000). This is also known as network sampling and usually occurs after data collection has started. In snowball sampling, participants already selected for the study are asked to recruit more participants (Omona Citation2013). In contrast to other methods, the data collected through snowball sampling relies not only on subjective declarations but also on the verification of those declarations through the questioning of linked individuals. This allows for greater accuracy in the declarations made by a member of a dyadic network regarding their partners (Audemard Citation2020). Within the framework of the study, the research population consisted of staff architects working in the public and private sectors in Antalya, which is one of Turkey’s major cities contributing to the national economy (Url-2 Citation2022; Url-3, Citation2022). The city has experienced a significant boost in the construction sector, particularly due to the increasing tourism activities. In Turkey, it is a requirement for architects to obtain an official registration number from the local architects’ association in the cities where they intend to establish their own architectural offices. The Antalya Chamber of Architects comprises 2,034 registered architects actively working in the city. Among these, 508 architects hold the necessary official registration number to open their own architectural offices. Given this data, it was inferred that the remaining 1,526 architects are qualified staff architects eligible to take part in the survey as part of the study’s scope. The sample size for the survey, was determined using a formula based on the population size (Bal Citation2001). The formula is as follows:

N = Population (1526 staff architects)

n = Number of samples

p = Proportion of units of interest in the population (taken as 0,50)

q = The frequency of non-occurrence of the feature interested in the population (1-p)

Z = Standard value by confidence level (found from normal distribution tables 1.96 for 95%)

t2 = Tolerated error (values of 0.10 and below are taken).

n= 174 staff architects

The questionnaire was distributed to the participants via email, and they were requested to forward it to their colleagues. Despite the participant count being determined as 174 through the formula calculation, the sample for this study consisted of 132 staff architects, with 56 participants from the private sector and 76 participants from the public sector (n = 56, n = 76). The relatively small sample size can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, the timing of data collection coincided with economic fluctuations, which may have influenced individuals’ willingness to participate in research activities. During periods of economic uncertainty, individuals may be more hesitant to allocate time and resources to non-work-related tasks such as research. Secondly, the nature of the construction industry often involves demanding schedules and heavy workloads, leaving professionals with limited time for engaging in research. This may have contributed to the reduced availability and willingness of potential participants to take part in the study. Lastly, some employers may have been reluctant to support employee participation in research projects. The priorities and interests of employers, as well as their perception of the value of research, can influence their decisions to encourage or discourage employee involvement. If employers prioritize immediate project needs over research activities, it becomes challenging to obtain a larger sample size.

Despite these limitations, concerted efforts were made to mitigate them by reaching out to a wide range of professionals in both the private and public sectors. Although the sample size is small, it is believed that the data collected will still yield valuable insights into the research topic and contribute to the existing body of knowledge.

3.3. Data analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences). A p-value <0.05 was considered significant. Prior the main study, a pilot study was conducted by a group of architects. Validity tests are employed to assess whether a questionnaire accurately measures the intended variables (Ghozali Citation2005). An instrument is considered valid when there is a positive correlation between a factor score and a total score, with a significance value greater than 0.30 (r > 0.3). This indicates that all indicators used in this study have demonstrated their validity. Additionally, the Cronbach’s Alpha value of the scale was assessed during the pilot study to determine the reliability of the questionnaire, and it was found to have high reliability (α = 0,96).

Descriptive analysis was initially conducted to examine the characteristics of the study participants. Then, for the first research question, a t-test was performed to assess the differences in perceptions regarding the existence of motivational tools between staff architects working in the public and private sectors. Finally, for the second research question, correlation analysis was conducted to explore the relationship between motivational tools and staff architects` productivity. Only factors with strong correlations were considered during the evaluation process. Each correlation matrix illustrates the relationship between two variables at each measurement period. When interpreting the correlation coefficient, the strength of the relationship was classified as follows:

0.0–0.2 very weak correlation,

0.2–0.4 weak, low correlation,

0.4– 0.7 moderate or significant correlation,

0.7– 0.9 strong, high correlation,

0.9– 1.0 very strong correlation (Kayahan Citation2008).

In addition to the correlation analysis method, which tests the relationships between the mentioned variables, linear regression analysis was also performed.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the participants

When analysing the demographic characteristics of staff architects working in the public and private sectors, it was observed that the majority of employees were female in both the private sector (n = 43, 76.78%) and public sector (n = 60, 78.95%). Descriptive analysis revealed that in the private sector, 50% (n = 28) of staff architects fell within the age range of 28–33 years old, while in the public sector, 34,21% (n = 26) of the staff architects were between 34–39 years old. A closer examination of indicates that the number of architects working above the age of 40 in the private sector was nearly negligible (5.36%), whereas in the public sector, 27.63% of architects were above the age of 40.

Table 1. Findings on the demographic characteristics of the participants.

4.2. Comparison of staff architects` perceptions about the existence of motivational tools

presents the summary of staff architects` perceptions regarding the existence of motivational tools in their working life. The analysis revealed that there were no significant group differences among staff architects in relation to economic motivational tools. However, differences were observed in terms of psycho-social tools, and organizational and managerial motivational tools.

Table 2. Comparison of staff architects` perceptions about the existence of psychosocial motivational tools, and organizational and managerial motivational tools.

When examining the perceptions of the architects regarding the existence of psycho-social motivational tools, it was observed that employees in the private sector had a more positive view of the workplace`s image, vision, and general view of the workplace (Q5) compared to staff architects in the public sector. Additionally, employees in the private sector indicated that the general attitude of the managers towards employees (Q6) was more positive, with a greater emphasis on value and respect for their private lives, compared to the public sector.

From an organizational and managerial perspective, private sector employees reported a more positive perception of being granted greater authority, responsibility, and independence in their work (Q11) compared to public sector employees. Furthermore, public sector employees had less favorable perceptions of merit and fairness in promotions within their department (Q15) compared to their counterparts in the private sector. In contrast, public-sector employees reported that managers provided more educational opportunities (Q16). Additionally, while employees in both sectors expressed positive perceptions regarding appropriate working hours of the workplaces (Q17), it was observed that the public sector employees held more favourable perceptions in this regard compared to those in the private sector. Lastly, public sector employees expressed higher satisfaction with holidays, and off days provided by the management (Q18) compared to private sector employees.

4.3. Comparison of staff architects` perceptions about the effect of motivation tools on their productivity

The results of the correlation analysis are presented in . Although very strong correlations could not be detected in both sectors in terms of economic tools and psycho-social tools, a very strong correlation was found in the private sector between appreciation, praise, and acknowledgment (Q7) and enjoyment and being satisfied with the work (Q8).

Table 3. Correlation analysis of participants` perceptions regarding the relationship between motivation and productivity.

In terms of organizational and managerial tools, there was no very strong correlation in the private sector. However, in the public sector a very strong correlation was observed regarding opportunity for promotion in the workplace (Q14), the merit and justice in promotions (Q15), and holidays, off days provided by the management (Q18).

In the final part of the study, a regression analysis was conducted on the motivational tools that exhibited a very strong correlation. The results showed that the motivational tool of appreciation, praise, and acknowledgment (Q7) had a statistically significant (p < 0.05) and positive (β = 0.963) effect on the productivity variable for private sector employees. Additionally, the motivational tool of enjoyment and satisfaction with the work (Q8) was found to be an important factor in the relationship between motivation and productivity, with a statistically significant (p < 0.05) and positive (β = 0.981) effect ().

Table 4. The effect of motivational tools Q7 and Q8 on the productivity variable of private sector employees.

For public sector employees, motivational tool of opportunity for promotion in the workplace (Q14) was found to have a statistically significant (p < 0.05) and positive (β = 0.963) effect on the productivity variable. Similarly, the motivational tool of merit and justice in promotions (Q15) was also found to have a statistically significant (p < 0.05) and positive (β = 0.948) effect on the productivity variable for public sector employees. Additionally, holidays, and off days provided by the management (Q18) were identified as an important factor in the relationship between motivation and productivity, with a statistically significant (p < 0.05) and positive (β = 0.961) effect ().

Table 5. The effect of motivational tools Q14, Q15, and Q18 on the productivity variable of public sector employees.

5. Discussion

5.1. Perceptions regarding the existence of motivational tools

Regarding the results, this research found that there is no significant difference regarding the economic motivational tools. Therefore, hypothesis 1 has been rejected. However, this result does not confirm the previous research of Buelens and Van den Broeck (Citation2007), who found that private-sector employees placed more value on economic motivational tools compared to public-sector employees. Their findings were also consistent with those of Karl and Sutton (Citation1998), Houston (Citation2000), and Bullock et al. (Citation2015). A possible explanation for the difference in findings could be the economic fluctuations experienced in Turkey as a developing country. Both public and private sector employees have been negatively affected by these fluctuations in recent years. Although the economic conditions of private sector employees are generally better than those of public sector employees, the purchasing power has decreased in Turkey, resulting in financial problems becoming a common issue for both groups.

On the other hand, a significant difference has been found in terms of psycho- social motivational tools, and organizational and managerial motivational tools. Therefore, hypothesis-2 and hypothesis-3 have been accepted. The public sector has inherent limitations, while the private sector offers more flexibility in terms of administrative and personal benefits. The study revealed that in the public sector, the existence of psycho-social motivational tools was insufficient, but the existence of organizational and managerial motivational tools was sufficient. In contrast, in the private sector, the existence of psycho-social motivational tools was sufficient, while the existence of organizational, and managerial motivational tools was insufficient ()

In this context, it can be argued that the limitations of the public sector contribute to a decrease in employee motivation in terms of psycho-social aspects. One possible explanation for this is the hierarchical and bureaucratic nature of the work, which imposes more constraints on architects’ freedom to act. Previous studies (Markovits et al. Citation2010) have noted that public sector employees are typically expected to work efficiently within bureaucratic structures and prioritize standardized procedures and formalities rather than promoting creativity and change. On the other hand, research by Marisa and Yusof (Citation2020) has highlighted the positive impact of architects` working conditions, organizational support, and freedom in the private sector on their performance. The presence of freedom and tolerance in executing work tasks is considered important for enhancing psycho-social motivation of staff architects, but such motivational tools are often lacking in the public sector.

Regarding the private sector, the insufficient presence of organizational and managerial motivational tools can be attributed to the absence of hierarchical relationships and limited promotion opportunities for staff architects. Olatunji et al. (Citation2014) defined promotion opportunities as an organizational factor that affects motivation. In the private sector, particularly in small to medium-sized design firms, economic fluctuations have led to limited promotion prospects, making it challenging for staff architects to advance in their careers.

In summary, the primary objective of the first research question in this study was to investigate whether there are disparities in the perceptions of the adequacy of motivational tools among staff architects in their professional roles. Hypotheses H1, H2, and H3 were formulated to address this question. The analysis revealed significant differences in perceptions about the existence of motivational tools between the public and private sectors. The differences in perceptions of economic tools between the two sectors contradict previous research and suggest that economic fluctuations in Turkey may serve as a possible explanation (H1). Additionally, notable differences were observed in the perceptions of physical-social (H2) and organizational/managerial motivational tools (H3), highlighting the contrasting nature of these factors between the public and private sectors. These findings shed light on the limitations within the public sector and the lack of sub-supervisor relationships in the private sector, offering valuable insights into the distinct motivational dynamics experienced by staff architects.

5.2. Perceptions regarding the effect of motivation tools on productivity

The present study found no significant difference in the impact of economic motivational tools on productivity among the examined groups. Therefore, hypothesis 4 has been rejected. However, significant differences were observed in the effects of psycho-social motivational tools and organizational and managerial tools, supporting hypothesis 5 and 6.

Regarding psycho-social motivational tools, a strong relationship was found between motivation and productivity among staff architects in the private sector. Specifically, appreciation, praise, and acknowledgment were identified as effective tools for enhancing motivation and productivity in the private sector. This findings aligns with previous research by Doloi (Citation2007), who emphasized the importance of employee appreciation and appropriate rewards in achieving productivity in the private construction sector. Additionally, enjoyment and satisfaction were identified as important factors in the relationship between motivation and productivity for private sector employees. Hence, it can be concluded that psycho-social tools have a greater impact on architects working in the private sector compared to those in the public sector.

In contrast, for employees in the public sector, a strong relationship was found between motivation and productivity in terms of organizational and managerial motivational tools. Notably, promotion opportunities within the department were identified as a significant factor, along with holidays, off days provided by the workplace, and merit and justice in promotions. This suggest that organizational and managerial tools have a stronger influence on the relationship between motivation and productivity for architects working in the public sector. Wright (Citation2001) also highlighted that easily accessible awards may not be a significant motivating factor in the public sector, given its systematic and well-established structure with promotion opportunities as a key goal for employees. Therefore, as stated by Wright (Citation2001) other awards might not ensure motivation in the public sector. The research conducted by Jain and Bhatt (Citation2015) further supported these findings, indicating that public sector employees prioritize organizational stability, while private sector employees focus on employer branding factors. Therefore, it is not surprising that psycho-social motivational tools are more effective in motivating the private sector to enhance productivity. By utilizing the appropriate motivational tools effectively, managers can establish a system that enhances employee productivity and fosters a competitive working environment among employees.

The main objective of the second research question in this study is to investigate whether there are differences in the impact of motivational tools on staff architect productivity. With regard to economic motivational tools (H4), the study found no significant difference in their impact on productivity, challenging previous results showing a strong association between the two. Significant differences observed across psychosocial motivation tools (H5) and organizational/management tools (H6) highlight the need for a differentiated understanding of factors that influence motivation and productivity across sectors. The differing results can be attributed to contextual factors, such as economic fluctuations in Turkey, which may have influenced the perceived value and impact of various incentive instruments in the public and private sectors. Methodological differences between studies, such as sample size, measurement instrument, and geographic location may have contributed to differences in observed results. Future research should delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms and contextual factors to gain a comprehensive understanding of the complexity of the relationship between motivation and productivity in the construction industry.

5.3. Limitations

A few limitations should be acknowledged regarding the present study. Firstly, the study relied solely on the personal opinions of the respondents to determine the relationship between motivation and productivity among staff architects. This constitutes a major limitation as subjective perceptions may not fully capture the objective reality of the relations.

Secondly, the research focused specifically on staff architects in the private and public sectors within the boundaries of Antalya. The construction sector encompasses various professional groups, and the study’s scope was limited to architects only. Therefore, the generalizability of the findings may be restricted to this specific group and geographic location. While the construction industry in Antalya holds significant importance for the Turkish economy, it is important to recognize that the findings may not fully represent the broader context of Turkey as a developing country.

It is essential for future research to address these limitations by considering a wider range of professional groups within the construction sector and expanding the study’s geographical scope. By doing so, a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between motivation and productivity among professionals in the construction industry can be achieved.

6. Conclusion

The relationship between motivation and productivity is a major concern for managers and it should be analysed according to sectoral differences. The main goal of the current study was to determine the differences between the public and private sectors. Within the scope of the study, the comparison considered three fundamental motivational tools (1) economic, (2) psycho-social, and (3) organizational-managerial tools.

The results of the study revealed significant differences in perceptions about the existence of motivation tools between the two sectors, suggesting distinct motivating tools experienced staff architects. Economic fluctuations in Turkey were identified as a possible explanation for the differences in perceptions of economic tools. Furthermore, significant differences were observed in perceptions of psycho- social and organizational/managerial tools, highlighting the contrasting nature of these factors across sectors. The study challenges previous research by revealing contradictory results regarding the impact of economic motivational tools on productivity, indicating that the relationship between the two may be influenced by contextual factors. In addition, significant differences were observed in the impact of psycho-social, and organizational/management tools on productivity, highlighting the need for a differentiated understanding of drivers across sectors.

This study contributes to the existing body of knowledge by revealing differences in public and private sector perceptions and the impacts of motivational tools. It highlights the importance of considering contextual factors and industry-specific dynamics when studying the relationship between motivation and productivity in the construction industry. This understanding could guide future research and influence the development of comprehensive theories and frameworks for studying motivations in different sectors. The research also has practical implications for managers and policymakers in the public and private sectors. The results highlight the need for organizations to tailor incentive strategies to the specific needs and expectations of each sector. In the public sector, addressing the constraints that limit the availability of psycho-social tools can increase motivation and productivity. Understanding the impact of different perceptions and motivational tools can help managers develop strategies to develop an engaged and productive staff. The study has social implications as it highlights the importance of ensuring architects are motivated and productive in both sectors. By addressing the motivational needs of staff architects, organizations can contribute to the quality of architectural design, innovation, and the overall well-being of the community. Ultimately, this research aims to help increase motivation and productivity in the construction industry, benefitting architects, organizations, and society at large. Future research on how to develop incentive tools specifically for these two sectors is expected to be a major contribution to the scientific field. It is also recommended that similar studies be conducted in the future to compare the results with those in developed countries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s)

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Bengü Gizli Tabaklar

Bengü Gizli Tabaklar completed her master's thesis on motivation and productivity at Akdeniz University Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences. She continues her research in this field.

İ̇kbal Erbaş

Ikbal Erbaş is an Associated Professor in the Department of Architecture at Akdeniz University. Her current research topics include occupational safety and health, contract management, construction management.

References

- Aghayeva, K., and B. Ślusarczyk. 2019. “Analytic Hierarchy of Motivating and Demotivating Factors Affecting Labor Productivity in the Construction Industry: The Case of Azerbaijan.” Sustainability 11 (21): 5975. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11215975.

- Al-Abbadi, G. M. D., and G. Agyekum-Mensah. 2022. “The Effects of Motivational Factors on Construction Professionals Productivity in Jordan.” International Journal of Construction Management 22 (5): 820–831. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2019.1652951.

- Alagele, L. D. H. K. H. 2020. “The Importance of the Role of Motivating Employees in Achieving Organizational Effectiveness: A Field Study.” Managerial Studies Journal 13 (26): 268–283. Accessed August 5, 2023. https://www.iasj.net/iasj/search?query=The+Importance+of+the+Role+of+Motivating+Employees+in+Achieving+Organizational+Effectiveness%3A+A+Field+Study.

- Al Jassmi, H., S. Ahmed, B. Philip, F. Al Mughairbi, and M. Al Ahmad. 2019. “E-Happiness Physiological Indicators of Construction workers’ Productivity: A Machine Learning Approach.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 18 (6): 517–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2019.1687090.

- Anderson, L. B. 1995. “Design Review Processes.” Studies in the History of Art 50 (1): 45–48. Accessed June 5, 2023. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42621967.

- Apraku, K., F. K. Bondinuba, A. K. Eyiah, and A. M. Sadique. 2020. “Construction Workers Work-Life Balance: A Tool for Improving Productivity in the Construction Industry.” Social Work and Social Welfare 2 (1): 45–52. https://doi.org/10.25082/SWSW.2020.01.001.

- Arditi, D. 1985. “Construction Productivity Improvement.” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management. ASCE. 111 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(1985)111:1(1).

- Aslan, M. 2014. The effect of motivation on performance and productivity in working life. Master Thesis, Beykent University, İstanbul, Turkey.

- Audemard, J. 2020. “Objectifying Contextual Effects. The Use of Snowball Sampling in Political Sociology.” Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique 145 (1): 30–60.

- Aytürk, N. 2010. Örgütsel ve Yönetsel Davranış Örgütlerde İnsan İlişkileri ve Yönetsel Davranış Yöntemleri, 159–175. Ankara: Detay Publishing.

- Bal, H. 2001. Scientific Research Methods and Techniques. Isparta, Turkey: Süleyman Demirel University Press.

- Bawa, M. A. 2017. “Employee Motivation and Productivity: A Review of Literature and Implications for Management Practice.” International Journal of Economics, Commerce and Management 5 (12): 662–673. Accessed June 10, 2023. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Employee%20motivation%20and%20productivity%3A%20A%20review%20of%20literature%20and%20implications%20for%20management%20practice&author=M.A.%20Bawa&publication_year=2017&pages=662-673.

- Bernold, L. E., and S. M. AbouRizk. 2010. Managing Performance in Construction. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons Inc.

- Brewer, G. A., and G. A. Brewer Jr. 2011. “Parsing Public/Private Differences in Work Motivation and Performance: An Experimental Study.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21 (suppl_3): i347–i362. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mur030.

- Buelens, M., and H. Van den Broeck. 2007. “An Analysis of Differences in Work Motivation Between Public and Private Sector Organizations.” Public Administration Review 67 (1): 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00697.x.

- Bullock, J. B., J. M. Stritch, and H. G. Rainey. 2015. “International Comparison of Public and Private employees’ Work Motives, Attitudes, and Perceived Rewards.” Public Administration Review 75 (3): 479–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12356.

- Bunchoowong, D. 2015. “Work Motivation in Public Vs Private Sector Case Study of Department of Highway Thailand.” Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research 4 (3): 216.

- Burt, R. S. 1984. “Network Items and the General Social Survey.” Social Networks 6 (4): 293–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8733(84)90007-8.

- Çolak Alsat, O. 2016. An application for determining the effects of factors affecting employee motivation on job satisfaction. Doktoral Dissertation, Selçuk University, Konya, Turkey.

- Doloi, H. 2007. “Twinning Motivation, Productivity and Management Strategy in Construction Projects.” Engineering Management Journal 19 (3): 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/10429247.2007.11431738.

- Eren, E. 1984. Yönetim Psikolojisi, 160. İstanbul: 30th Year Publishing.

- Erkut, H., and D. MacLean. 1992. “Efficiency and Encouragement.” Journal of Productivity 6 (3): 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1287/inte.22.3.15.

- Furusaka, S., T. Kaneta, T. Miisho, and T. Akiyama. 2002. “Client Satisfaction and New Direction of Architects’ Services.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 1 (1): 213–220. https://doi.org/10.3130/jaabe.1.213.

- Ghozali, I. 2005. Aplikasi Analisi Mulivariate dengn SPSS, 40. Semarang, Indonesia: Badan Penerbit UNDIP.

- Gurcanli, G. E., S. Bilir Mahcicek, E. Serpel, and S. Attia. 2021. “Factors Affecting Productivity of Technical Personnel in Turkish Construction Industry: A Field Study.” Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 46 (11): 11339–11353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-021-05789-z.

- Hajarolasvadi, H., A. Aghaz, and V. Shahhosseini. 2022. “Ranking and Analyzing Key Motivation Factors of Engineers in the Construction Industry.” Sharif Journal of Civil Engineering 37 (4.2): 59–70.

- Hamid, A., and M. Younus. 2021. “Effect of Work Motivation on Academic Library professionals’ Workplace Productivity.” Library Philosophy & Practice 2021:1–26. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/5737.

- Hamza, M., S. Shahid, M. R. Bin Hainin, and M. S. Nashwan. 2022. “Construction labour productivity: review of factors identified.” International Journal of Construction Management 22 (3): 413–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2019.1627503.

- Hanaysha, J. R., and M. Majid. 2018. “Employee Motivation and Its Role in Improving the Productivity and Organizational Commitment at Higher Education Institutions.” Journal of Entrepreneurship & Business 6 (1): 17–28. https://doi.org/10.17687/JEB.0601.02.

- Hansen, S., S. F. Rostiyanti, and A. Nafthalie. 2020. “A Motivational Framework for Women to Work in the Construction Industry: An Indonesian Case Study.” International Journal of Construction Supply Chain Management 10 (4): 251–266. https://doi.org/10.14424/ijcscm100420-251-266.

- Houston, D. J. 2000. “Public-Service Motivation: A Multivariate Test.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 10 (4): 713–728. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024288.

- Huckfeldt, R., J. Sprague, and J. Levine. 2000. “The Dynamics of Collective Deliberation in the 1996 Election: Campaign Effects on Accessibility, Certainty, and Accuracy.” American Political Science Review 94 (3): 641–651. https://doi.org/10.2307/2585836.

- Jain, N., and P. Bhatt. 2015. “Employment Preferences of Job Applicants: Unfolding Employer Branding Determinants.” Journal of Management Development 34 (6): 634–652. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMD-09-2013-0106.

- Jarkas, A. M., and T. C. Haupt. 2015. “Major Construction Risk Factors Considered by General Contractors in Qatar.” J Eng Des Technol 13 (1): 165–194. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEDT-03-2014-0012.

- Jarkas, A. M., M. Radosavljevic, and L. Wuyi. 2014. “Prominent Demotivational Factors Influencing the Productivity of Construction Project Managers in Qatar.” International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 63 (8): 1070–1090. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-11-2013-0187.

- Jean Lee, S. K. 1992. “Quantitative versus qualitative research methods—Two approaches to organisation studies.” Asia Pacific Journal of Management 9 (1): 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01732039.

- Johari, S., and K. N. Jha. 2020. “Impact of Work Motivation on Construction Labor Productivity.” Journal of Management in Engineering 36 (5): 04020052. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)ME.1943-5479.0000824.

- Kalogiannidis, S. 2021. “Impact of Employee Motivation on Organizational Performance. A Scoping Review Paper for Public Sector.” The Strategic Journal of Business & Change Management , 8 (3), 984 996 (3). https://doi.org/10.61426/sjbcm.v8i3.2064.

- Karatepe, S. 2005. “Ödüllendirme yönetimi: örgütlerde güdülemeye duyarlı bir yaklaşım (Reward management: a motivational-sensitive approach in organizations).” Journal of Ankara University Faculty of Political Sciences 60 (4): 117–132.

- Karl, K. A., and C. L. Sutton. 1998. “Job Values in Today’s Workforce: A Comparison of Public and Private Sector Employees.” Public Personnel Management 27 (4): 515–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/009102609802700406.

- Kayahan, C. 2008. “İşletmelerde bir avantaj unsuru olarak kur korelasyonlarının kullanımı.” Yönetim ve Ekonomi 15 (1): 75–84.

- Kazaz, A., E. Manisali, and S. Ulubeyli. 2008. “Effect of Basic Motivational Factors on Construction Workforce Productivity in Turkey.” Journal of Civil Engineering and Management 14 (2): 95–106. https://doi.org/10.3846/1392-3730.2008.14.4.

- Kazaz, A., and S. Ulubeyli. 2007. “Drivers of Productivity Among Construction Workers: A Study in a Developing Country.” Building and Environment 42 (5): 2132–2140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2006.04.020.

- Kencana, P. N., L. Asmalah, and B. Munadjat. 2021. “The Effect of Discipline and Work Motivation on Work Productivity on Shaza Depok Employees.” Journal of Research in Business, Economics, and Education 3 (4): 68–75.

- Koçel, T. 1995. Business Management, 382–402. İstanbul: Beta Publishing.

- Manoharan, K., P. Dissanayake, C. Pathirana, D. Deegahawature, and R. Silva. 2022a. “A Guiding Model for Developing Construction Training Programmes Focusing on Productivity and Performance Improvement for Different Qualification Levels.” Construction Innovation 23 (4): 733–756. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/CI-10-2021-0194.

- Manoharan, K., P. Dissanayake, C. Pathirana, D. Deegahawature, and R. Silva. 2022b. “Labour-Related Factors Affecting Construction Productivity in Sri Lankan Building Projects: Perspectives of Engineers and Managers.” Frontiers in Engineering and Built Environment 2 (4): 218–232. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/FEBE-03-2022-0009.

- Manoharan, K., P. Dissanayake, C. Pathirana, D. Deegahawature, and R. Silva. 2023. “Assessment of Critical Factors Influencing the Performance of Labour in Sri Lankan Construction Industry.” International Journal of Construction Management 23 (1): 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2020.1854042.

- Marisa, A., and N. A. Yusof. 2020. “Factors Influencing the Performance of Architects in Construction Projects.” Construction Economics and Building 20 (3): 20–36. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v20i3.7119.

- Markovits, Y., A. J. Davis, D. Fay, and R. V. Dick. 2010. “The Link Between Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: Differences Between Public and Private Sector Employees.” International Public Management Journal 13 (2): 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967491003756682.

- McCoach, D. B., and J. K. Flake. 2018. “The Role of Motivation.” In APA Handbook of Giftedness and Talent, edited by S. I. Pfeiffer, E. Shaunessy-Dedrick, and M. Foley-Nicpon, 201–213. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Momade, M. H., and M. R. Hainin. 2018. “Problems affecting squatter settlements in Nampula, Mozambique.” International Journal Engineering &technology (UAE) 7 (4): 5022–5025.

- Momade, M. H., and M. R. Hainin. 2019. “Identifying Motivational and Demotivational Productivity Factors in Qatar Construction Projects.” Engineering, Technology & Applied Science Research 9 (2): 3945–3948. https://doi.org/10.48084/etasr.2577.

- Momade, M. H., S. Shahid, G. Falah, D. Syamsunur, and D. Estrella. 2021. “Review of Construction Labor Productivity Factors from a Geographical Standpoint.” International Journal of Construction Management 23 (4): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2021.1917285.

- Naderifar, M., H. Goli, and F. Ghaljaie. 2017. “Snowball Sampling: A Purposeful Method of Sampling in Qualitative Research.” Strides in Development of Medical Education 14 (3): 14(3. https://doi.org/10.5812/sdme.67670.

- Olatunji, S. O., A. E. Oke, and L. C. Owoeye. 2014. “Factors Affecting Performance of Construction Professionals in Nigeria.” International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology 3 (6): 76–84.

- Oloruntoba, S., and A. Olanipekun. 2021. Socio-Psychological Motivational Needs of Unskilled Women Working in Nigeria’s Construction Industry. Procs West Africa Built Environment Research (WABER) Conference, Ghana, 9–11.

- Omona, J. 2013. “Sampling in Qualitative Research: Improving the Quality of Research Outcomes in Higher Education.” Makerere Journal of Higher Education 4 (2): 169–185. https://doi.org/10.4314/majohe.v4i2.4.

- Örücü, E., and A. Kanbur. 2008. “An Empirical Study to Examine the Effects of Organizational-Managerial Motivation Factors on the Performance and Productivity of Employees: Service and Industry Business Example.” Journal of Management & Economics 15 (1): 85–97.

- Özkeser, B. 2019. “Impact of Training on Employee Motivation in Human Resources Management.” Procedia Computer Science 158:802–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2019.09.117.

- Pancasila, I., S. Haryono, and B. A. Sulistyo. 2020. “Effects of Work Motivation and Leadership Toward Work Satisfaction and Employee Performance: Evidence from Indonesia.” The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics & Business 7 (6): 387–397. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no6.387.

- Phan, P. T., C. P. Pham, N. T. Q. Tran, H. T. T. Le, H. T. H. Nguyen, and Q. L. H. T. T. Nguyen. 2020. “Factors Affecting the Work Motivation of the Construction Project Manager.” The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business (JAFEB) 7 (12): 1035–1043. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2020.vol7.no12.1035.

- Prokopenko, J. 2011. Verimlilik Yönetimi Uygulamalı Elkitab. Translated by O. Baykal, N. Atalay, and E. Fidan. Vol. 476. Ankara: Milli Prodüktivite Merkezi Yayınları.

- Putra, I. N. S. K., and N. W. Mujiati. 2022. “The Effect of Compensation, Work Environment, and Work Motivation on Employee Productivity.” European Journal of Business and Management Research 7 (2): 212–215. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejbmr.2022.7.2.1310.

- Ramirez, C. 2020. A Motivating Factor: A Closer Look at the Importance of Intrinsic Motivation in Public Sector Employees’ Performance. Diss. California State University, Northridge

- Reeve, J. 2016. “A Grand Theory of Motivation: Why Not?” Motivation and Emotion 40 (1): 31–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9538-2.

- Ryan, M. R., and E. L. Deci. 2017. Self- Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Sabuncuoğlu, Z., and T. Tokol. 2005. Management, 26–35. Bursa, Turkey: Alfa Aktuel Press.

- Sabuncuoğlu, Z., and M. Vergiliel Tüz. 2008. Örgütsel Psikoloji, 35–92. Bursa, Turkey: Alfa Aktuel Press.

- Saddiya, K., and F. A. Aziz. 2022. “Effects of Motivation Parameters on Employee Performance in a Saudi Construction Company.” East African Journal of Engineering 5 (1): 72–86. https://doi.org/10.37284/eaje.5.1.586.

- Selen, U. 2016, Evaluation of employees’ perspectives on internal and external motivation techniques; local government example. Doctoral Disertation, Namık Kemal University Tekirdağ, Turkey.

- Setiawan, R., L. P. L. Cavaliere, A. R. Chowdhury, K. Koti, P. Mittal, T. S. Subramaniam, and S. Singh 2021. The impact of motivation on employees productivity in the retail sector: the mediating effect of compensation benefits ( Doctoral dissertation), Petra Christian University.

- Shiru, M. S., E. S. Chung, S. Shahid, and N. Alias. 2020. “GCM Selection and Temperature Projection of Nigeria Under Different RCPs of the CMIP5 GCMS.” Theoret Appl Climatol 141 (3): 1611–1627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00704-020-03274-5.

- Şimşek, M. Ş., A. Çelik, and T. Akgemci. 2014. Davranış Bilimlerine Giriş ve Örgütlerde Davranış. 145–162. Konya: Eğitim Publishing.

- Sitopu, Y. B., K. A. Sitinjak, and F. K. Marpaung. 2021. “The Influence of Motivation, Work Discipline, and Compensation on Employee Performance.” Golden Ratio of Human Resource Management 1 (2): 72–83. https://doi.org/10.52970/grhrm.v1i2.79.

- Soliman, E., and H. Altabtai. 2023. “Employee Motivation in Construction Companies in Kuwait.” International Journal of Construction Management 23 (10): 1665–1674. https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2021.1998303.

- Sugathadasa, R., M. L. De Silva, A. Thibbotuwawa, and K. A. C. P. Bandara. 2021. “Motivation Factors of Engineers in Private Sector Construction Industry.” Journal of Applied Engineering Science 19 (3): 794–805. https://doi.org/10.5937/jaes0-29201.

- Tam, N. V., T. Watanabe, and N. L. Hai. 2022. “Importance of Autonomous Motivation in Construction Labor Productivity Improvement in Vietnam: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective.” Buildings 12 (6): 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12060763.

- Url- 1. http://www.mimarlarodasiankara.org/index.php?Did=4374. Last Accessed July 1, 2022

- Url-2 https://www.haberturk.com/antalya-haberleri/84279481-antalya-turkiye-buyumesine-en-fazla-katki-veren-ilk-3-il-arasinda. Last Accessed July 1, 2022

- Url-3 cc https://www.antalya.bel.tr/BilgiEdin/ekonomi#:~:text=Antalya%20%C5%9Fehrinin%20ekonomisinde%20turizm%2C%20ticaret,kollarda%20i%C5%9F%20faaliyetleri%20de%20s%C3%BCrd%C3%BCr%C3%BClmektedir. Last Accessed July 1, 2022

- Van Tam, N. 2021. “Motivational Factors Affecting Construction Labor Productivity: A Review.” Management Science and Business Decisions 1 (2): 5–22. https://doi.org/10.52812/msbd.31.

- Van Tam, N., N. Quoc Toan, D. Tuan Hai, N. Le Dinh Quy, and W. K. Tan Albert. 2021. “Critical Factors Affecting Construction Labor Productivity: A Comparison Between Perceptions of Project Managers and Contractors.” Cogent Business & Management 8 (1): 1863303. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1863303.

- Wright, B. E. 2001. “Public-Sector Work Motivation: A Review of the Current Literature and a Revised Conceptual Model.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 11 (4): 559–586. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a003515.

- Zhang, X. A., H. Liao, N. Li, and A. E. Colbert. 2020. “Playing It Safe for My Family: Exploring the Dual Effects of Family Motivation on Employee Productivity and Creativity.” Academy of Management Journal 63 (6): 1923–1950. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.0680.