ABSTRACT

Establishing the value of retail space is the key to the success of shopping malls. The research in this field attracts attention, where the rented spaces have the same value to create the highest profit for tenants and shopping mall owners while providing convenience for visitors. The aim of this research is to verify the factors that form space value using scoring techniques on shopping malls in Indonesia. This research method uses triangulation with sequential and simultaneous approaches. Qualitative uses observational case studies followed by quantitative through assessment scales confirmed by expert practitioners shopping mall development. Jakarta and Surabaya were chosen as research areas with the highest population levels and the most shopping malls in Indonesia. The results show that three factors form space value: spatial layout, accessibility of space, and visitor visibility. Shopping malls in Indonesia are more dominated by one of the space value factors, while other factors are not so highlighted. These findings produce a scoring technique that can be used as an evaluation tool for implementing space value in shopping malls and pave the way for researchers interested in the retail property sector regarding strategic retail space planning, especially shopping mall development in developing countries.

1. Introduction

Shopping centers or shopping malls have been associated with the urban environment and become an essential part of urban society to meet various needs. In China and America, the popularity of shopping malls continues to increase from time to time (Arslan and Ergener Citation2022; Chen, Xue, and Sun Citation2023). The two countries are said to be the most active markets in shopping mall development. But at the same time, the concern is also increasing because many shopping malls have closed, leaving empty buildings abandoned due to competition from other shopping malls (Burayidi and Yoo Citation2021), plus the emergence of new shopping concepts through e-commerce (Guimarães Citation2019). Stores in a shopping mall that their tenants have abandoned will eventually lose visitors’ interest, reducing operational performance. As happened in America, in 2017, there were 6,985 store outlet closures (Thomas Citation2017), while in 2021, 11459 shops were closed in the UK (Sabanoglu Citation2023), and 3,924 stores were closed in China (Ma Citation2022). This phenomenon concerns re-evaluating construction practices towards building sustainability to avoid fruitless use of resources and as a source of pollution during the life cycle.

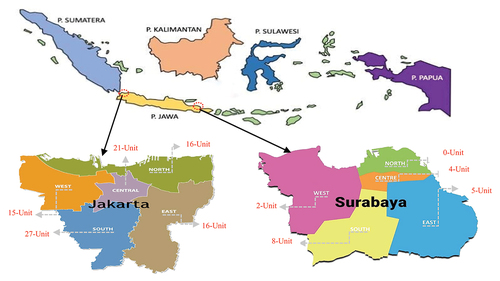

Indonesia has five major islands: Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Papua. Java is the island with the densest population in Indonesia and become the center of industry and economy. The island of Java’s economy significantly contributes to Indonesia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of 56.55% (Dihni Citation2022). As a developing country with a large population, Indonesia is an attractive market for large retail companies and property developers to open shopping malls. Retail is one of the industries that contribute to the economy and ranks third in terms of GDP, where from the expenditure side, the consumption of the Indonesian people is closely related to the retail industry. The shopping mall is a physical aspect of the urban environment and has become a place for people to fulfill various needs. In the following, shows the distribution of shopping malls in Indonesia. Based on the Indonesia Central Bureau of Statistics, in 2020, the total number is 649 units shopping malls, with details of 41-units on the island of Sumatra, 18 units on the Kalimantan, 389 units on Java, and 36 units on Sulawesi. Retail consists of 38,323 unit department stores, 1,411 unit supermarkets, and 285 unit hypermarkets. The large amount indicates that the role of retail is very important, especially in supporting economic activity in terms of trade and consumption.

Spatial design and arrangement are the main elements in the development of shopping malls because it is related to the arrangement of stores and creating movement in space. Vacancies in retail space in shopping malls occur because one of them is caused by location factors (Brown Citation1999). The right retail location is the key to success which depends on the pattern of visitor flow. Research by Bai and Yao (Citation2018) and Büyükşahin (Citation2022) stated that visitor flow patterns allow people to move between spaces and interact within spaces. In this context, to achieve the commercial goal of retail stores in shopping malls having the same space value and obtaining optimal profits, a design is needed where visitors can access the shopping mall space horizontally and vertically easily and comfortably (Sun and Yu Citation2021). Spaces with a high level of connectivity can affect visitor movement patterns, so every placement of shops in a shopping mall must be designed appropriately to capture consumer traffic. The spatial design of shopping malls that are not appropriate can have implications for significant economic losses.

Retail spaces that have easy access to traverse in shopping malls are places that have a high level of connectivity, and rental prices are also high. Various existing studies have discussed the arrangement of retail space so that it contributes to the success of shopping malls (optimizing tenant and developer profits), for example, by increasing mall traffic and sales through the distribution of pedestrian flows (Yiu, Xu, and Ng Citation2008; Yuo and Lizieri Citation2013; Zhou and Liu Citation2021); optimizing the layout of tenants to maximize profits (Carter and Allen Citation2009; Yuo and Lizieri Citation2013); developed a retail space placement strategy model that maximizes customer flow through the store (Lv and Wang Citation2020); examine the circulation layout of shopping malls and their effect on visitor density (Park and Zhang Citation2019), and recently by using space-syntax theory to analyze the level of connectivity and integration between retail spaces (Büyükşahin Citation2022; Deb and Mitra Citation2020; Zhou and Liu Citation2021).

However, existing research has not discussed how retail space has the highest and best value in its arrangement. Many existing studies discuss space strategies only to obtain the highest rental prices from tenants for the benefit of shopping malls. In contrast in terms of the convenience of visitors in enjoying travel in shopping mall spaces, there has not yet been much research. Shopping centers in Indonesia can be categorized into three groups. The first is supermarkets and hypermarkets that sell daily necessities. Second are department stores, and third are shopping centers that combine supermarkets and hypermarkets on a large scale. This study reviews all these categories, where shopping malls in this category are all located in the city center. If some are located on the outskirts of the city, they are located in the center of the new city which has commercial areas with large-scale residential areas. The characteristics of shopping malls in Indonesia are all mid and high-rise buildings, so the issue of determining space value is very important, especially in shopping malls in Indonesia. Therefore, this research aims to fill the research gap by conducting an observational study to verify the formation and application of optimal retail space in the development of shopping malls in Indonesia. The importance of this research can pave the way for researchers interested in retail property and contribute to the development of knowledge to align theory and practice regarding the strategic planning of retail space, especially in developing countries.

2. Literature review

2.1. The history of shopping malls development

Various researchers have described shopping malls, and this definition has evolved. Arakawa’s (Citation2006) researchstates that a shopping mall is a place where various shops dominate, starting from anchor tenants, for example, department stores, and non-anchor tenants or specialty stores that sell goods or services to consumers. Another definition was also expressed by Hagberg and Styhre (Citation2013), who stated that shopping malls are spaces designed to offer goods and services to visitors to maximize profits and, on the other hand, produce a comfortable and safe social space. And the most recent, Krey et al. (Citation2022) describes a more detailed definition of a shopping mall: a retail environment with a unique grouping of a mix of service and retail businesses to form attractive recreational opportunities under one roof. Based on the understanding expressed by previous researchers, the meaning of this shopping mall refers to a place where various social activities occur, namely between consumers and sellers (transactions), relationships between consumers (socializing), and consumer relations with their environment (a form of relaxation). This is a high-level commercial space (Ortegón-Cortázar and Royo-Vela Citation2017).

History finds that the first shopping mall was in Greece, approximately 2,700 years old. The shopping mall is located in Argilos, an elite area in the 5th century BC, on the seafront of Aegen. The characteristic of this shopping mall is open space, which is unique because it was built by each owner lined up with one another (Muller Citation1945). In 1908, planned shopping malls were constructed in the United States, namely Roland Baltimore Park (McKeever and Griffin). Throughout the 1920s to the 1930s, the development of shopping malls in the U.S. was relatively standard with the opening of the most influential shopping mall in 1922, namely the Country Club Plaza (The Plaza), Missouri. This shopping mall was designed by J.C. Nicholas and was built to build a city through trade. Various shops and facilities complement this shopping mall, including various shops for daily needs such as grocery stores, clothing, medicines, the availability of entertainment venues such as parks, benches, and fountains, as well as various other community activities (Geoffrey and Baker Citation1951; Nichols Citation1945). Since then, shopping malls have emerged such as the Upper Darby Center in Philadelphia in 1927, Highland Park in Dallas in 1931, and the River Oaks Center in Houston in 1937 (Hoyt Citation1960).

Victor Gruen was an early pioneer of regional shopping malls in the 1940s in favor of pedestrians, eliminating the use of vehicles for shopping malls. The principle is almost identical to Nichols, who designed shopping malls as retail places and community and cultural activities. In his design, Gruen emphasizes the shopping mall as a place that is not only a business center but also a place of relaxation (Gillette Citation1985). The climax, after World War II, the explosion of shopping malls began to occur along with the population that was increasingly spread out in the metropolitan area. Northland Center has become the most desirable retail area since its opening in 1954 in Michigan. This shopping mall with open space has five competitive anchor tenants and accommodates nearly 100 small shops. The following year, precisely in 1956, the closed mall concept, namely the Southdale Center Minnesota, was opened, resulting from Gruen’s next design. This shopping mall is equipped with room temperature control to create a comfortable shopping environment; however, the shopping environment is also more organized to attract more visitors. Gruen, who combined the psychological influence of visitors in his mall design, became the first step in the development of shopping malls worldwide that adopted the closed shopping mall design in America (Gillette Citation1985).

With the development of the retail property market, China has become the country with the most significant number of shopping malls worldwide. A big jump-started from 2003 to 2013, initially numbered 236 to 3,500 shopping malls, beating the United States in 2014, which had 1,200 shopping malls (Chen, Xue, and Sun Citation2023). The popularity of this shopping mall also indicates the classifier of shopping malls based on various criteria. Coleman (Citation2006) divides it into catchment categories, namely affordability and target consumers, for example, regional, district, local, etc.; others such as location, for example in a city or out of town; tenant variation; retail type; physical form of shopping malls; and a combination of the above. The important role of shopping malls in influencing consumer lifestyles has forced the design of shopping malls to meet customer preferences. Customer preferences, for example, in terms of utilitarian and hedonic shopping values, influence consumer satisfaction with shopping malls (Kesari and Atulkar Citation2016). The existence of satisfaction with shopping malls can create visitor loyalty; this is determined based on the variety of tenants in the shopping mall, the comfortable internal environment of the mall, as well as the mix of leisure time where there are various entertainment facilities and places to gather or relax (Ortegón-Cortázar and Royo-Vela Citation2017). Therefore shopping malls are not only a place of business but also place of recreation to find entertainment (Calvo-Porral and Lévy-Mangín Citation2018).

In line with that, the development of shopping mall research has begun to focus on how to increase the success of shopping malls through the design and spatial arrangement based on the preferences of visitors and tenants. Visitors have preferences, that is, optimizing trips and shopping as much as possible in one trip (Büyükşahin Citation2022). Visitors do not like shopping malls that force them to walk far to buy the things they need (Borgers et al. Citation2010). Meanwhile, tenants expect strategic store locations with high traffic flow (Eckert, He, and West Citation2013) and profitable tenant interactions (Burnaz and Topcu Citation2011). In the following, presents research developments in the design and arrangement of retail space in shopping malls.

Research on space design in shopping malls has existed since the 1980s, analyzing the attractiveness of shopping mall and their relation to customer patronage and satisfaction. It is helpful to know the relationship between shopping mall image with shopping trips and expenses (Wee Citation1986). The research generally describes shopping malls as creating a pleasant environment where visitors are energized because the shops are not too spread out and provide public facilities such as children’s playgrounds. This will help in increasing patronage . It was only in 2000 that specifically began to discuss spatial planning in shopping malls. As presented in , this is a reputable research compiled historically for the last 13 years. This research continues to increase in discussing spatial design in shopping malls.

In its development, several studies have attempted to analyze the design of shopping mall spaces that provide satisfaction to visitors and increase profits for tenants. For example, from 2010 to 2012, existing research discussed consumer preferences for store location placement (Borgers et al. Citation2010; Kim and Runyan Citation2011) and optimal tenant mix strategies in shopping malls (Teller and Schnedlitz Citation2012; Yiu and Xu Citation2012). From 2013 to 2015, research related to store grouping in shopping malls (Eckert, He, and West Citation2013; Yuo and Lizieri Citation2013) and visitor movements in space (Baek Citation2015; Eckert, He, and West Citation2015; Lu and Seo Citation2015). From 2016 to 2018, researchers began to combine tenant placement and visitor behavior (Yılmaz and Cakmak Citation2018; Hirsch et al. Citation2016; Ortegón-Cortázar and Royo-Vela Citation2017), as well as the relationship between people movements and the configuration of spaces the shopping mall (Bai and Yao Citation2018; Haofeng, Yupeng, and Xiaojun Citation2017; Omer and Goldblatt Citation2017). As for 2019 to 2022, more research has focused on increasing store sales through spatial organization and the interaction of people with space (Arslan and Ergener Citation2022; Büyükşahin Citation2022; Colaço and de Abreu e Silva Citation2022; Ha et al. Citation2020; Khairunnisa and Gamal Citation2022; Khare Citation2020; Lv and Wang Citation2020; Orr and Stewart Citation2022; Yuan et al. Citation2021; Zhou and Liu Citation2021).

2.2. Shopping mall in Indonesia

In Indonesia, the era of shopping malls began in 1966, marked by the opening of a modern retail building known as PT. Indonesian Department Stores. In 1979, the mall changed its name to Sarinah and had the status of a State-Owned Enterprise in the retail sector. Sarinah is located in Central Jakarta. It carries the concept of “The Window of Indonesia” with the hope that it will become a space for creativity for the community to promote domestic products. Then, in 1982 the operation of the second mall in Jakarta, namely Gajah Mada Plaza, has a well-known supermarket and department store as its anchor tenant. In 1986, a third mall was established in another city in Indonesia, Tunjungan Plaza Surabaya. This mall has a building area of around 44,000 m2 and has undergone an expansion which has now reached 148,500 m2. In 2016 the number of malls in Indonesia continued to grow; overall, the total area reached 4.5 million m2. The capital city of Jakarta is the city in Indonesia with the most malls, three of which are even included in the ranks of the 100 largest malls in the world (Putra, Said, and Hasan Citation2017). Until now, the most significant number of shopping malls are on the island of Java, with 389 units of shopping malls.

Various malls in Indonesia have started to be built including in small suburban towns; along with the changes in the lifestyle of the Indonesian people, they make shopping malls a favorite place to spend their free time. This is also supported by the consumer behavior of society (Putra, Said, and Hasan Citation2017). This creates competition between shopping malls to attract more consumers. As a result, there is an uneven distribution pattern of visitors and tenants, so several shopping malls are empty and crowded with visitors. Several shopping malls in the heart of Jakarta are empty of visitors, even some of their tenants have abandoned their stalls. The existence of this emptiness is also related to the design in terms of the placement of tenant locations that are not strategic. From the start of the design, facility management involvement is necessary for connection with forming a unique and attractive design strategy for consumer comfort, safety, and satisfaction (Astarini, Utomo, and Rohman Citation2022). The hallmark of shopping malls in Indonesia is that apart from selling various products to meet the needs of visitors, there are also various facilities such as places of worship (mosques and churches); entertainment includes discotheques, cinemas, playgrounds; and services, including medical clinics, pharmacies, banks, travel agents, spas, beauty salons, driver’s license services, tax services, to currency exchange (Mediastika, Sudarsono, and Kristanto Citation2022).

2.3. The development of space value in shopping malls

In the theory of shopping mall development, it is stated that one of the attributes that can attract consumers to visit and influence purchasing behavior is the convenience of visitors in accessing the location (strategic location), the ease of visitors in accessing between shops within it (Makgopa Citation2016; Maria et al. Citation1977), and the catchment area (Man and Qiu Citation2021). Ke and Wang (Citation2016) state that the location factor directly affects the determination of retail space rental prices. When stores with strategic locations are easy to reach, the greater their success in attracting consumers and increasing sales. Placing the wrong tenant location can have fatal consequences: losses caused by low visitor traffic. In the end, the shops that cannot generate profits will be abandoned by their tenants, resulting in vacancies that can damage the shopping mall’s reputation. Burnaz and Topcu (Citation2011) state that shopping malls expect a sustainable environment through consistently high profitability. This can be achieved by establishing an optimal space strategy. Space must be designed to comfort its users so that people in the room can arrive at their destination as efficiently as possible (Baek Citation2015). There are several types of space in shopping malls: linear, cartesian, branch systems, and combinations. A linear form is a spatial arrangement that is generally straight (Zhou and Liu Citation2021) and often characterized by a dumbbell, L, curve, etc. layout with pull points at both ends of the area to optimize visitor traffic (Arslan and Ergener Citation2022). The cartesian form refers to a layout based on the concept of a coordinate system where this spatial model adopts a grid system that forms a square pattern in space organization (Arslan and Ergener Citation2022). A branch system is a layout system in which the flow direction is formed by line intersections (Zhou and Liu Citation2021); it locates shops forming branches connected to the main line (Arslan and Ergener Citation2022). As well as a combination type characterized by combining more than two typologies to create a unique space combination (Deb and Mitra Citation2020).

Space value in shopping malls is defined as the optimal distribution of space so that the rented spaces have the same value regarding visitor affordability. Research on the space value of shopping malls (Aydogan and Salgamcioglu Citation2017; Deb and Mitra Citation2020; Ha et al. Citation2020; Khairunnisa and Gamal Citation2022; Lv and Wang Citation2020; Omer and Goldblatt Citation2017; Yuo and Lizieri Citation2013), shows a close relationship with the movement patterns of visitors in shopping malls. This is because determining visitor movement or circulation patterns can make it easier for visitors to find and recognize store locations easily and avoid unbalanced density in space (Park and Zhang Citation2019). Distributed visitor movement patterns can also be utilized in store layout arrangements, for example, through space segmentation to maximize tenant profits in shopping malls (Andi, Abednego, and Gultom Citation2021; Bai and Yao Citation2018; Lv and Wang Citation2020), thereby influencing the behavior of visitor buying and preferences (Lu and Seo Citation2015). In other words, the movement and search for the path of visitors are influenced by the shape of the space and the visitor’s assessment of the space (Aydogan and Salgamcioglu Citation2017); besides that, the movement of visitors also depends on the ease of accessibility (Frasquet, Gil, and Molla Citation2001; Ortegón-Cortázar and Royo-Vela Citation2017; Yuan et al. Citation2021), and visibility of the space (Büyükşahin Citation2022; Khairunnisa and Gamal Citation2022; Omer and Goldblatt Citation2017; Park and Zhang Citation2019). is a factor that can support the formation of space value for shopping mall space.

Table 1. Factors space value of shopping mall.

Tenant placement, as presented in , the first factor is tenant placement. Tenant placement is the allocated of tenants based on their characteristics in certain zones to create a flow of visitors and stimulate purchases (Andi, Abednego, and Gultom Citation2021). In the space design of shopping malls, integrated spatial planning allows visitors to reach and see other spaces easily. Various studies have investigated the optimal tenant layout from the visitor’s side as well as from the tenant’s side. From the visitor side, it is explained in research by Hirsch et al. (Citation2016) through customer surveys combined with Geographic Information System (GIS) techniques to analyze ideal tenant placement. The research results show that stores with the same retail category have a higher relationship. Therefore, for visitor comfort, a grouping of the same tenants must be done, especially in malls with many floors. Meanwhile, for malls with few floors, tenants of the same type must be spread. Borgers et al. (Citation2010) used experiments on visitors with the help of VR tools. The research analyzes consumer preferences regarding the selection and placement of stores in shopping centers. The results show that visitors do not like a lot of variety in stores selling the same type of product, and consumers generally prefer clustered stores. From the tenant side, Yuo and Lizieri (Citation2013) used an empirical study of three shopping centers in Hong Kong to determine the relationship between store size, type of tenant, and tenant location in the shopping center. Research states that to increase visitor footfall, shops with high impulses (fashion and accessories) are placed on the lower floors. In contrast, non-impulsive stores (toy stores, home furnishings, food and beverage, supermarkets and community services) and anchor stores are placed on the upper floors. The effect of grouping similar shops in one zone was also studied by Lv and Wang (Citation2020). This research uses optimization modeling in existing shopping malls to determine the clustering effect that occurs by considering the factors of retail type, brand level and store area. The research results show that the proposed model can help in determining maximum rental prices through shop agglomeration and externalities between shops. This is also inseparable from the influence of consumer or visitor behavior. Khare (Citation2020) used a case study to understand retailers’ perceptions of store location strategies in shopping malls in India. The research findings state that tenant decisions in determining store location are influenced by the presence of other retail tenants in connection with increasing externalities and the attractiveness of the shopping center. Eckert et al. (Citation2013) also used an empirical study to examine store location patterns and evaluate their level of consistency with respect to exploiting externalities of mall physical features, including stores adjacent to the main entrance (Eckert, He, and West Citation2015). The findings are that non-anchor stores located close to the main tenant also gain profitability due to externalities between stores (Eckert, He, and West Citation2013).

Accessibility of space. The second factor is accessibility in the formation of space value. Space accessibility consists of vertical paths which refer to connections between floors via escalators, lifts and stairs; as well as horizontal paths which are reflected in the reach and connectivity of space through the mall corridor (Andi, Abednego, and Gultom Citation2021). Weber (Citation2003) states that distance is the main factor that can influence accessibility which refers to proximity to the destination to minimize travel. In shopping mall spatial planning, accessibility factors play an important role in making visitor easier to reach many destinations from various space origins (Tannous, Major, and Furlan Citation2021), both through horizontal and vertical routes. Accessibility concerns the comfort of visitors, including those that can accommodate people with disabilities, such as lifts that fit wheelchairs or there is a travelator, and easily accessible toilet placement (Coleman Citation2006; Makgopa Citation2016). Shops in shopping malls are expected to have a high level of accessibility with the aim of maximizing profits for tenants and shopping center developers (Colaço and de Abreu e Silva Citation2022). This suggests that space accessibility depends on how the space is arranged or organized (Zhou and Liu Citation2021). Several researchers describe the importance of accessibility factors in spatial design, and it is often used for the success of shopping malls. For example, the study of Forgey and Goebel (Citation1995) shows that accessibility factors enable visitors to enter and exit shopping centers easily by arranging shopping center access close to the main road. In particular, this has a direct impact on the consumer experience. Ortegón-Cortázar and Royo-Vela (Citation2017) conducted surveys and interviews with visitors from 25 shopping centers in Colombia to find out shopping mall attributes that can attract consumers to come to shopping centers. One of the factors identified is accessibility which consists of freedom of movement, walking and convenience of shopping in stores. The research results show that accessibility has an indirect effect on the intention of consumers to visit shopping centers. Bai and Yao (Citation2018) predict pedestrian flow in three shopping malls in downtown Shenzhen using Visibility Graph Analysis (VGA) technology. The goal is to increase the commercial space advantage through an even distribution of pedestrians. The results of research found that there is a significant influence between accessibility and sight so that it is useful in planning the arrangement of anchor stores and other retail stores. There are also Yuan et al. (Citation2021) who used a questionnaire survey to find the influence of design elements on the consumer experience from the perspective of shopping mall designers in China. One of the findings shows that the spatial structure consisting of accessibility, visibility and spatial identification has a direct influence on the consumer experience of shopping malls. Likewise, Zhou and Liu (Citation2021) through case studies of three shopping malls in China which aim to explore optimization principles and strategies for optimizing shopping mall space. Based on the research, the result found four basic space optimizations that shopping malls must have, namely the principles of accessibility, identification, diversity, and humanization. Tenants expect their locations to be easily accessible physically and/or visually. Accessibility depends on how the space is arranged and laid out, where good accessibility (vertical and horizontal) will support the visibility of visitors who tend to move to find their destination (Andi, Abednego, and Gultom Citation2021).

Visibility of visitor. The third formation factor of space value is the visibility of visitor in the shopping mall. Visibility refers to the condition where a subject from a certain position can see several objects known as visual access; and the area of the object being observed, which is called visual exposure (Khairunnisa and Gamal Citation2022). In retail theory, visibility through store visual design is able to influence consumer behavior concerning creating store attractiveness (Baek, Choo, and Lee Citation2018). The same thing is emphasized in research Kim (Citation2013) which found that visually attractive product arrangements can increase sales volume. The process of visualizing products in a store is a form of non-verbal communication in attracts many customers to buy goods or visit a store. Researchers Yılmaz () also revealed that visual comfort is the most dominating factor in the retail environment. In designing shopping mall space, the visibility factor can influence visitor movement patterns (Büyükşahin Citation2022; Khairunnisa and Gamal Citation2022; Lu and Seo Citation2015), which tend to move in a linear direction. According to Alagamy et al., (Citation2019), the relationship between visibility and accessibility is closely related, because visitors will pay more attention to spaces that have a high level of connectivity. Furthermore, visual trends rely on circulation areas where visitors are free from visual obstructions that can create a feeling of crowding (Büyükşahin Citation2022; Omer and Goldblatt Citation2017; Park and Zhang Citation2019), and legibility of the room through a proportionally sized atrium (Kusumowidagdo, Sachari, and Widodo Citation2016). Likewise, Omer and Goldblatt (Citation2017) show that the volume of movement generally increases in spaces with a clear circulation system. The clarity of space is formed by the breadth of the vertical area, such as the ceiling height, and the horizontal area, namely the width of the corridor (Kusumowidagdo, Sachari, and Widodo Citation2016). Meanwhile, according to Khairunnisa and Gamal (Citation2022), the availability of an atrium can support shops with high visibility, thus increasing shop rental prices in shopping mall because it allows visitors to see the store easily.

3. Methods

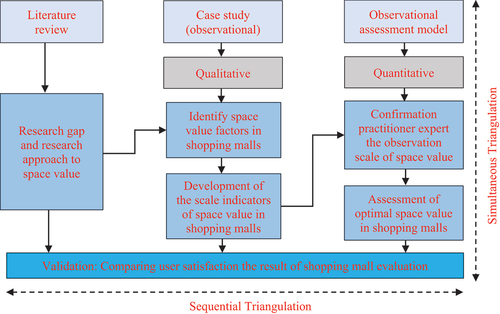

This research applies the triangulation method with two approaches used, which are sequential and simultaneous. Sequential triangulation refers to research carried out sequentially, where the results of each research stage are used for the next stage. In simultaneous triangulation, the combination of research stages together provides results that are used in model development (Utomo and Idrus Citation2011). The triangulation method is useful in minimizing potential research bias through cross-verification of the empirical data collected (Gustavsson and Gohary Citation2012). Qualitative research uses observational case studies, which are then confirmed using a quantitative approach through expert practitioners and validated using surveys of user satisfaction in shopping malls. In the field of social sciences, one method of collecting qualitative data is using observational studies, this is an important research method as well as the most diverse (Busetto, Wick, and Gumbinger Citation2020; Ciesielska, Boström, and Öhlander Citation2017). Observational studies allow researchers to spend a lot of time in the field to obtain information, study, process, and understand the object of study, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the object from the researcher’s point of view (Baker Citation2006). According to Busetto et al. (Citation2020), observations in qualitative studies can be participant or non-participant. In this study, the role of the researcher is non-participant, where the researcher is the object of the study, but his presence is not part of the situation. This is a passive role because the researcher does not interact with people around him. In other words, the role of the researcher, in this case, is to observe and/or listen (Baker Citation2006).

First of all, this research conducted a literature review to find gaps and research approaches regarding the space value of retail properties. The results of the literature review were used to conduct an observation case study by collecting photos, videos and observation notes on the shopping mall being reviewed. The observation aims to identify indicators for each space value factor, and develop an indicator scale. The observation data collected includes indicators of tenant layout arrangements, how vertical transportation is implemented and the level of visitor visibility. All observation data was transcribed and analyzed, including the indicator scales for each factor determined, confirmed by expert practitioners as a second data source. Each indicator of each space value factor is identified for the negative impacts it causes to determine the priority scale. The observation scale is set starting from 1 = low and 7 = high. A score of 1 is given for indicators of low space value factors, and a score of 7 for factors forming high space value. A high score indicates that the indicator has the least resistance or negative influence. The assessment results were then confirmed by expert shopping mall development practitioners. Confirmation results of the expert practitioner assessment scale to obtain an assessment of shopping malls that have the best space value. Further, validate the research results through user satisfaction. The following is presented . The flow of the triangulation method used.

Observations were made for three hours, from 12.00 to 15.00 on weekdays and from 19.00 to 21.00 on holidays (Saturday or Sunday). Other significant events or celebrations were not considered in this study. This time was chosen because on weekdays, visitors generally increase at lunchtime, while on holidays, visitors enjoy entertainment or quality time with family or friends. The observed objects include the layout of retail spaces (anchor and non-anchor shops; tenants are leasable areas) which play an important role in encouraging pedestrian circulation; store affordability through a vertical transportation layout that facilitates visitor accessibility, as well as store visitor visibility in shopping malls. Data collection is done through notes, photo documentation, and video recordings. The collected data is then analyzed to find out how the spatial arrangement of the shopping mall that was reviewed. Furthermore, by using a scoring scale that experts have confirmed, find a shopping mall that has the best spatial value. This study seeks to reflect on the findings based on descriptive theory to analyze and describe the object of the case under study in depth.

This research uses the cities of Jakarta and Surabaya as case objects. The determination of Jakarta as the research location is based on the national capital, and Surabaya is the second largest city after Jakarta. Both cities have the most shopping malls among other big cities in Indonesia. DKI Jakarta and Surabaya provinces are divided into five municipalities. The area of Jakarta includes Central Jakarta Municipality with an area of 47.90 km2, North Jakarta with an area of 142.20 km2, West Jakarta with an area of 126.15 km2, South Jakarta with an area of 145.73 km2, and East Jakarta Municipality with an area of 187.73 km2. Meanwhile, Surabaya has a total area of 326.8 km2. The number of shopping malls in Jakarta is 95 units, and Surabaya is 19 units spread across various regions ().

Figure 4. Territorial division and distribution of shopping malls in Jakarta and Surabaya, Indonesia.

Since experiencing the new normal period in early 2022, various shopping malls have started to resume operations. The number of visitors recorded based on data from PeduliLindungi shows that there are six shopping malls, especially in Jakarta and Surabaya, which have the highest number of visits during the January-February period. The shopping malls are Grand Indonesia Shopping Town (GIST) in Central Jakarta with an average number of visits of 433,319 visitors; Pondok Indah Mall (PIM) and Kota Kasablanka Mall (Kokas) in South Jakarta, which each had an average number of visits of 512,609 and 436,532 visitors; Central Park Mall (CPM) in West Jakarta which has a total number of visits of 381,813 visitors; Summarecon Mall Kelapa Gading (MKG) in North Jakarta with 433,422 visitors. Even though we did not find data on visits to one of the shopping malls in East Jakarta, this research includes AEON Mall Jakarta Garden City as the object of the case, considering that this shopping mall is still new and also quite attractive. For Surabaya, the object used is Pakuwon Mall Surabaya (PM), with 375,920 visitors. This is one of the largest malls in Indonesia, and Ciputra World is the new face of the Surabaya shopping mall, which recently underwent an extension.

Shopping malls are always expected to be able to adapt to any changes in people’s lifestyles to attract visitors/consumers. Consumers can enjoy pleasure just by being in a shopping mall space or experiencing social interaction. presents data on seven shopping malls with the highest level of crowds after implementing the new normal period in Indonesia.

Table 2. Data shopping malls.

Based on , the shopping mall under review has more than five anchor tenant units and more than 200 non-anchor units. These malls are a closed mall centers and are included in combination purposive trips where recreation, entertainment, and commerce come together under one roof (Warnaby and Medway Citation2018).

3.1. Case study Grand Indonesia Shopping Town (GI)

The object of the first case is Grand Indonesia (GI). GI is one of the largest malls in Central Jakarta, with an area of 141,472 m2. shows that this shopping mall comprises 214 tenants and services and ten anchor tenants spread across three parts of the building. The west side of the building has nine floors, the east side has eight floors, and the five-story sky bridge building is the link between the west mall and the east mall.

The GI shopping mall is characterized by a linear layout: the placement of anchor tenants in the GI is located at the end of the mall space. Small tenants are placed along the corridor connected to the anchor tenants. Several shops selling similar products are placed in groups in the shopping mall area, for example, on the lower ground floor (LG), which is generally filled with health and beauty product stores; most of which are occupied by food and beverage (restaurants and fast food) category stores; financial services; and the anchor tenant is the supermarket. For shops with exclusive brands, the store’s location is on the following three floors: the ground floor (G floor)−the area where the entrance is located, upper ground floor (UG floor), and the 1st floor. Stores with exclusive brands are providers that sell products in men’s and women’s clothing, bags, shoes, and fashion accessories (jewelry and watches). This area also has cafe and department stores as anchor tenants. Floors 5 and 6 (2nd and 3rd floor), tenants of goods and services are more diverse, such as several fashion shops with casual styles (men, women, and children); fashion accessories; personal services (barbers and beauty salons); health and product shops beauty (cosmetics, and optic); children’s toy stores; and bookstores as anchor tenants. The seventh and eighth floors (4th and 5th floors) are occupied by food courts; electronics stores; financial services; entertainment (game centers and karaoke); as well as furniture and household appliances stores as anchor tenants. Finally, the cinema is located on the ninth floor (6th floor).

This study highlighted vertical transportation, that is, escalators located at three points on the side of the building; west, east, and sky bridge. The placement of escalators on the west and east sides of the building is designed to rotate, leading visitors around the shop area on the escalator side. The goal is to increase the value of store around the escalator area through visibility. Meanwhile, the escalator on the sky bridge is made continuous, making it easier for visitors to access. However, the level of visitor visibility in this area is low. The elevator is not so highlighted in this shopping mall. Lastly, this shopping mall has an atrium that supports visitor visibility between floors. The atrium is located on the east side of the building. The atrium is rectangular and large, thus supporting visitor visibility of shops on the side of the atrium on the same floor and different floor levels.

3.2. Case study Kota Kasablanka (Kokas)

Based on , Kota Kasablanka is located in the South Jakarta area with an area of approximately 119,279 m2. It is a five-floor building with a cartesian system. The number of tenants is 227, with 13 anchor tenants, making Kokas a one-stop shopping mall. This shopping mall is dubbed as one of the busiest shopping malls in South Jakarta, which offers a unique shopping and lifestyle experience with the concept of Family and Entertainment Mall. In the layout setting, the lower floor or lower ground floor (LG floor) is occupied by various health and beauty product shops; stationery shops; financial services; travel services; gadget shops; and supermarkets and electronics shops as anchor tenants. Various restaurants and cafés occupy three floors (LG, G, and UG floors) with external doors on the G floor. Department stores also occupy three floors (G, UG, and 1st floors). Several well-known fashion brands, including clothes, bags, shoes, and men’s and women’s accessories occupy the second and third floors (G and UG floors). On the fourth floor (1st floor), there are furniture and household appliances stores, fashion stores with modern brands; casual and sporty styles; shoes and bags; accessories (jewelry and watches); health shops (optic); and fitness services. Kids’ fashion; toys shops; educational services; and entertainment (cinema and game center) occupy the last floor (2nd floor).

Another thing is that there are more vertical transportation points in the shopping mall space. This indicates that Kokas prioritizes easy accessibility for visitors, bearing in mind that in the shopping mall space, many intersections can make it difficult and make visitors get lost; besides that, the rented space is quite dense. However, the thing that is emphasized is that visitors are directed to use escalators more than elevators because the elevator’s location is made a little hidden. This study observes that Kokas has an escalator model that is made continuous to make it easier for visitors regarding accessibility. In terms of visibility, tenants are placed linearly to support visitor visibility in the horizontal direction, while to support visitor visibility in the vertical direction, Kokas shopping mall has three atriums. The main atrium is circular and the second and third are rectangular. The atriums that are owned all support visitor visibility to the shops on the atrium side. The availability of an atrium can support the convenience of visitors in identifying shops around the atrium and creating a legibility where visitors can freely see from all directions.

3.3. Case study Pondok Indah Mall (PIM)

Based on , Pondok Indah Mall (PIM) has 18 anchor tenants and several mini anchors, and there are 542 tenants, including goods and service shops spread from PIM 1 to PIM 3. PIM 1 has a plan in the form of a branch system totaling three floors, while PIM 2 and PIM 3 have a linear plan totaling five floors, each with the anchor store at the end of the space.

In general, the product segmentation in the PIM shopping mall below the ground floor (LG floor) is supermarkets and fitness centers (gyms), food street areas and convenience stores. The second and third floors (G and 1st floor) are occupied by shops with well-known fashion brands; accessories (jewelry and watches), bags and shoes, beauty and health stores, home furniture products; financial services; electronic store; and the anchor tenant, namely the department store which occupies three floors. Because the space in this shopping center is linear, the end of the space on the second floor is occupied by various restaurants, while the end of the space on the third floor is filled with various mini anchors and department stores. On the fourth floor (2nd floor) there is an entertainment area; a toy store; several modern fashion and accessories shops; a health shop (optics); baby and children’s shops; and a children’s playground as main tenants. Finally, the 5th floor (3rd floor) is occupied by sporty-style fashion shops; stationery; a sports area; an electronic store; a cinema; and food courts.

In terms of visitor circulation, this study found that the vertical transportation layout of the PIM shopping mall can also be reached easily, indicating that this mall prioritizes visitor accessibility. In PIM 1, vertical transportation, such as escalators, is on the side of the space, while the elevator is in the middle. The escalator model is made continuous so visitors do not need to surround the shops in the escalator area to go to the desired location on the top floor; in this case, the store value through visitor visibility is low. For PIM 2 and PIM 3, the placement of vertical transportation is made the same (elevator and escalator) on each side of the space. Visitors are directed to surround the shops in the escalator area because the placement of the escalator is made to spin so that the shops around the escalator area have a high visibility value. In short, PIM 1 relies more on visitor accessibility in reaching the intended area, while in PIM 2 and PIM 3, accessibility and visibility are equally divided.

The availability of a large and elongated atrium also supports visitors’ visual access to the shops along the corridor. At PIM 1, the atrium is small, so the view of visitors was limited to the same floor level. Unlike the case with the atrium owned by PIM 2 and PIM 3, which are in the form of a oval with large size. The visibility of visitors is wider, where the shops on the atrium side can be seen easily. In addition, in the horizontal direction the tenants are placed parallel to form an ellipse which makes it easier for visitors to see the shops on the same floor. Another thing that is in the spotlight is that there is a connecting bridge between corridors on the left and right sides of the atrium; its function is as a horizontal circulation of visitors. This increases the value of shophouse space through easier access.

3.4. Case study Central Park Mall

Central Park Mall (CP) is a shopping mall located in the West Jakarta area. This shopping mall has an area of approximately 125,626 m2 with 250-unit shops consisting of sellers of goods and services (). The building has nine floors with a spatial design in the form of a linear system. CP is also integrated with international standard offices, apartments, theme parks, resorts, and luxury hotels which makes CP the second-largest mall in Indonesia.

In the spatial arrangement, the lower ground floor (LG floor) is occupied by restaurants and various food streets, beauty and health shops, financial services, health services, and supermarkets as anchor tenants in the middle of the space. A convenience shop occupies the mezzanine floor (LGM floor). The ground and upper ground floors (G and UG floors) are occupied by fashion shops and various accessories with luxury brands; health shops (optic); and leather accessory and luggage shops. G floor as the main lobby provides a seating area, also on this floor, there are anchor tenants that is department stores that occupy four floors at one end of the space. Next is the first floor, which is filled with various electronic shops (mobile phones); travel agency agents; hairstyling services; health services; and restaurants and cafes, which are at the end of the space. The second floor is a fashion shop for casual styles; health services; hairstyling services; entertainment (children’s playground), equipment and toys shop; and education. The third floor is filled with well-known restaurants; clothing and accessories shops; photo studios; and children’s play areas; bookstores; and sports arenas as anchor tenants. The eighth floor (4th floor) is a mezzanine that cellular network service providers occupy, while the last floor (5th floor) is intended for entertainment a cinema.

Furthermore, the CP shopping mall has several vertical transportation points. This study underlines the placement of vertical transportation, that elevators are placed in the middle of the atrium, and that escalators are located on each side of the room. What stands out is that several floors are not directly connected to the floors above them due to the placement of escalators between floors which are placed separately. As a result, visitors who wish to visit the floor at the top level pile up to use the elevator. Next on the spatial visibility factor, because the CP shopping mall floor plan is in the shape of a dumbbell and is supported by an elongated atrium, this provides easy visibility for visitors to the various shops around the atrium, both on the same floor level and on different floor levels.

3.5. Case study Summarecon Mall Kelapa Gading (MKG)

shows that MKG is a shopping mall in North Jakarta with an area of 150,000 m2 with a total of 488 tenants and 12 anchor tenants. In its development, MKG has also experienced an expansion where the first development (MKG 1) was in 1990 and the second stage (MKG 2) in 1995 due to increased community needs. In 2003 the mall was expanded as the third development phase (MKG 3), and in 2006 it was the final development stage of the MKG shopping mall (MKG 5).

MKG 1 and MKG 2 have a linear spatial design, while MKG 3 and 5 are branch systems. MKG 1 is a three-story building, while MKG 2, 3 and 5 are four-story buildings. Regarding the store layout at MKG shopping mall, the ground floor (G floor) is mostly occupied by men’s and women’s accessories; shoes for sporty style; food courts area; restaurants and cafes; some travel services; financial services; beauty and health stores; and a supermarket as the main tenant. The second floor (1st floor) is occupied by exclusive fashion brands including men’s and women’s fashion stores; accessories group (watches and jewelry); beauty and health stores; bookstore; there is also an anchor tenant, namely a department store, which occupies three floors and is at the end of the room. The third floor (2nd floor) is an electronics shop and a shop specializing in religious equipment; beauty and health shops and services; there is a game center; several baby and children’s stores; toy and stationery shops; education; and telecommunications services. Finally, on the fourth floor (3rd floor) there is an entertainment area (cinema) and food court.

This study observes the accessibility factor of space in the MKG shopping mall. For the accessibility factor through the vertical direction, there are two vertical transportation models used. The first is the placement of elevators and escalators in MKG 3 on each side of the atrium, making it easier for visitors to reach their destination quickly. As well as the second model is a rotating escalator, which means that visitors are directed to go around the shops around the escalator to increase the value of the shop space through visuals. This applies to MKG 1, 2, and 5. In the horizontal direction, MKG shopping mall also takes advantage of connecting bridges between corridors so that the value of store increases through easy access to visitors. The seating area can be found in MKG 3 where the entrance and exit are located. Next is the visitor visibility factor of vertical direction. In general, the MKG shopping mall has four atriums, but all the atriums in MKG 1 and 2 have low visibility because the atriums are small. As visitors stand in the center of the atrium, the shops on the upper floors seem invisible. It’s different from the atrium that belongs to the MKG 3 shopping mall. Due to the circular and large size of the atrium, the view of the shops on the upper floors of the atrium area can be seen easily. As for the visibility of visitors on the same floor, or horizontal direction, the tenants in MKG 1 and 2 are lined up linearly, while in MKG 3 which has a circular atrium, the tenants are placed in an elliptical shape.

3.6. Case study AEON Mall Jakarta Garden City (AEON-JGC)

AEON-JGC is located in East Jakarta and is a unique shopping mall because it has the highest Ferris wheel in Indonesia. The area of this shopping mall is 85,000 m2 with 227 tenants and five anchor tenants, as shown in . There are three atriums in this shopping mall, which are called main atrium, east atrium, and west atrium. The floor plan is linear, with the anchor tenant at the end of space. In the spatial arrangement of the AEON-JGC shopping mall, the ground floor (G floor) is an area occupied by supermarkets; various restaurants and various food streets; electronics stores; beauty and health shops; health services; and financial services. The first and second floors (1st and 2nd floors) are occupied by various fashion stores (clothes, bags, and shoes); accessories (watches and jewelry); barber and beauty parlors; travel services; restaurants; and a children’s playground as anchor tenants. Finally, on the third floor (3rd floor) is a food court area and a cinema as an anchor tenant. The grouping of tenants who sell similar products in this shopping mall is very strong. On the ground floor, for example, restaurants and various food streets are gathered on the east side of the atrium and some on the west side of the atrium. Another example is the beauty and health shop and services on the second floor, which is only on the west side of the atrium.

For space accessibility in the AEON-JGC shopping mall, vertical transportation, especially escalators, is placed at several atrium points in a rotating position, allowing shops around the escalator and atrium area to have high value through visitor visibility. Another thing, this shopping mall relies more on the use of escalators than elevators because the position of the elevator is on the side of the space and less visible to visitors to the shopping mall. This shopping mall also utilizes connecting bridges between corridors in the middle of the atrium. This is intended for easy accessibility; it can also support visitor visibility to the shops around the atrium. Examining the visibility factor, even though this mall has three atriums with a circle shape, all of them do not support visitor visibility. The shops on different floors are difficult to see due to the wide corridors.

3.7. Pakuwon Mall (PM)

Pakuwon Mall (PM) is one of Indonesia’s biggest malls located in Surabaya. Built in 2003 and known as Supermall Pakuwon Indah. This mall has an area of 200,000 m2 with 22 anchor tenants and 200 non-anchor tenants (). As a mall with a concept one-stop place, Pakuwon Mall provides a ballroom, convention center, and atrium that can be used for various events or meetings.

The building has six floors with a branch system plan. The basement floor is coded B-floor, where this floor contains a supermarket as the anchor tenant; various restaurants; stationery shops; health shops; accessories, and souvenir shops; as well as various services such as banking; tour and travel services; shoe repair; and reflexology services. The top floor of the basement (LG floor) is the main area because the entrance to the shopping mall is on this floor. This area has two anchor tenants, namely supermarkets and department stores which are placed at the end of the space; there is also a mini anchor in the middle of the room, which presents various well-known brands, ranging from fashion, accessories (watches, and jewelry); bags and shoes; beauty and health shops; household appliances and equipment; convenience stores; health services; as well as several food stands. On the third floor (G floor), almost the same as the LG floor, there are still two anchor tenants, several exclusive brands, and various modern shops for fashion and accessories; there is a health shop (optics) and various cafes and bakeries. Next on the fourth and fifth floors (1st and 2nd floors) are various gadget and electronics shops; beauty salons; fashion, accessories; bags and footwear for casual styles shops; children’s play zones; and family restaurants. This area also has mini anchors in the middle of the space and anchor tenants at both ends. Finally, on the sixth floor (3rd floor) is an entertainment area (children’s playground and cinema) and a food court.

Regarding space accessibility in the PM shopping mall, the ease of reach is seen by the availability of vertical transportation such as escalators which are placed at several points of space that are easily visible; at the same time, the use of elevators is not so emphasized. From the direction of the shopping mall entrance, visitors can immediately reach the escalators placed on each side of the atrium space. The escalator model is also made continuously without requiring visitors to go around the shops around the escalator. The PM shopping mall has an oval atrium with a large size. From the direction of the entrance, the shops around the atrium area can be seen up to two floors above. This indicates that the shops in the PM shopping mall have a reasonably high value. As for the same floor, visitors’ visibility of the tenants is also supported by the positions of the tenants which are placed in a row to form an ellipse so that visitors have a fairly high level of visibility.

3.8. Ciputra World (ciwo)

Ciputra World (Ciwo) is a superblock building that officially opened in 2011 and ran into an extension in 2021. Ciwo is a six-story building and has approximately 200 units of shops from various international brands. This shopping mall, with a new lifestyle concept in the city of Surabaya, presents a variety of upscale shopping, entertainment, food, and recreation.

In terms of building layout, this shopping mall is also similar to other shopping malls reviewed in this study. The lower ground floor (LG floor) is occupied by the three main tenants, which consist of a supermarket and two furniture stores. The ground floor (G floor), where the main lobby is located, comprises various luxury fashion products and accessories. There is also a department store that occupies an area of two floors (LG and 1st floor). Furthermore, on the first floor (1st floor) and the second floor (2nd floor), many fashion shops have modern and casual styles for men and women. Various banking services; beauty clinics; and toy shops also occupy some areas. The third floor (3rd floor) is an area with various restaurants and food courts located in the corner of the space. As well as on the fourth floor (4th floor) is occupied by a cinema; gym; household stores; places of worship; and a multipurpose meeting hall.

In the vertical space accessibility system, this shopping mall relies more on escalators than elevators. Many escalator points with a continuous model make it easier for visitors to access the shopping mall space without going around the entire mall area. Another uniqueness of this shopping mall is that the longest escalator in Southeast Asia connects directly between the ground floor (G floor) and the third floor (3rd floor), where the restaurant and food court areas are located. The aim is to facilitate visitors who want to enjoy the shopping mall space simply by eating with relatives or family without having to explore the mall space. In addition, this shopping mall also provides easy access horizontally through the availability of connecting bridges between corridors. Finally, Ciwo has four atriums that are oval in shape to support visitors’ vertical visibility. This atrium helps the visibility of visitors against the shops around the atrium. The visibility of the shops around the atrium is also wider because the placement of the shops is designed in a curved row so that the shops can be clearly recognized, both on the same floor level (horizontally) and on different floor levels.

4. Results

In the following of , the result of the observations is presented as a summary of each case study. The table shows the similarities and differences of each factor forming the value of space for the shopping mall under review. Based on , it can be seen the similarities and differences in the case study of the shopping mall. There are two identified similarities factors of tenant placement in the space of a shopping mall. First, stores with the same retail category are generally grouped or departmentalized. This tenant placement strategy is related to the number of floor heights. The second similarity is that the eight shopping malls place supermarkets on the lower ground floor (LG floor), where this area is adjacent to the parking lot.

Table 3. Similarities and differences in the factor of space value in the shopping malls.

The difference identified is the tenant placement factor, where the restaurant and food court areas in most case studies (six of the eight shopping malls) place these tenants on the upper floors. In terms of spatial accessibility, five out of three shopping malls concentrate more on the use of escalators for vertical access. In contrast, several shopping malls use connecting bridges between corridors for horizontal access. As for the visibility factor, four case studies use an atrium with an oval shape, three use a combination atrium, and the rest use a circle-shaped atrium. Regarding visitor visibility on each floor, four shopping malls place their tenants in a row to form an ellipse, three shopping malls use a combination (linear and elliptical) in the placement of tenants, and one shopping mall places its tenants in a linear row.

The next step is identifying space value factor indicators to place them on a priority scale, as presented in . The tenant placement factor has four indicators consisting of the main anchor is at the end of the space; non-anchor tenant locations close to anchor tenants or famous brands; non-anchor tenants are adjacent to circulation areas; and grouping similar tenants based on their zoning. The space accessibility factor has indicators of placement of elevators or escalators near the entrance; the degree of connectivity between spaces through horizontal routes; elevators and escalators are easy to reach from and to all tenants; and there is a seating area. The final factor, that is visitor visibility, consists of indicators the tenant area can only be seen from the same floor level; the tenant area can be seen from different floor levels; the tenant area can be seen at approximately 45° around the atrium.

Table 4. Indicators for each space value factor.

Next is to set a value scale for each factor reviewed in the case study. shows the priority scale of each space value factor which has been confirmed by experts. In prioritizing the indicators for each factor, the indicators that have the least negative or rejection effects are selected and placed on a score of 7. Such as the tenant placement factor where a score of 7 is given to “non-anchor tenants are adjacent to circulation areas”. The reason is that tenants who are close to circulation routes such as escalators or elevators are vulnerable to the risk of damage, which if it occurs can hinder visitor access. A score of 1 is given to the indicator “grouping of similar tenants”. The main reason is that the resulting economic agglomeration effect causes shopping mall visitors to be unevenly distributed due to overcrowding in only one part; competition between stores, especially those of the same type; and the existence of interdependence on certain trends that can be affected simultaneously by changing conditions.

Table 5. Scale value on the value of space shopping mall.

In the accessibility factor, the seating area gets the lowest score because shopping malls in Indonesia do not usually provide seating areas. Based on the case objects we reviewed, there are two shopping malls that provide seating areas. First, there is a shopping mall where the seating area is located near the entrance and exit, and the second shopping mall has a seating area in the main lobby. The two shopping malls became crowded due to the accumulation of people sitting in the area. A score of 7 is given to the accessibility factor where the placement of vertical transportation (elevators and escalators) is easily accessible from all areas of the shopping mall space. As for the visitor visibility factor, a low score is given to the indicator where visitors can only see tenants on the same floor level, and a score of 7 is given to the visibility indicator where the tenant can be seen by visitors from different floor levels.

In evaluation scores, if there is a shopping mall that has two indicators that conflict in one factor, then the indicator that has the smallest rejection level is selected. For example, if shopping malls have an indicator on the accessibility factor, namely the seating area, where this indicator has a small value in supporting the value of space (score 1), and on the one hand it also places vertical transportation that is easy to reach (score 7), then the assessment chosen is which has a value of 7. shows the level of application of the space value factor in each shopping mall.

Furthermore, this study conducted a pairwise comparison of each value of the space factor through the Saaty scale (Saaty Citation2006). The purpose of the pairwise comparison assessment is to find the relative importance of the criteria in the form of numbers. In this research, finding shopping malls with the best spatial arrangement value is useful. The following presents a pairwise comparison matrix of each criterion.

Table 6. Pairwise comparison matrix.

The next step is to calculate the normalized criteria weighting to find the preference level for each factor criterion. Normalized weight values are shown in .

Table 7. Normalized criterion degrees.

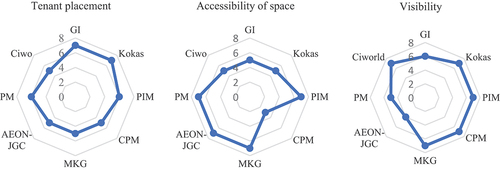

Based on the results, the weight value is converted into a percentage, which is then used to form shopping mall space values; that is, the tenant placement factor is 10%, space accessibility is 60%, and visibility is 30%.

Next is to evaluate the attributes where this result is a calculation of the weighting value multiplied by the scale value of each shopping mall; the maximum value found is 700, as shown in .

Table 8. Evaluation of attribute.

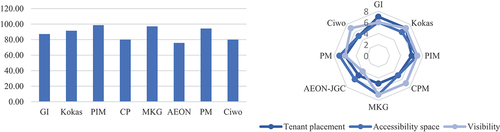

Based on , sequentially, the shopping malls that get the best value in terms of spatial planning are PIM with a score of 690; MKG score is 680; PM with a score of 660; Kokas score 640; GI with score 610; CP and Ciwo of 560; and AEON-JGC obtained a score of 530. Chart illustrations are presented in , Recapitulation of space value factors in shopping malls.

User satisfaction is measured to validate the shopping mall space value. Descriptive analysis was carried out using mean and variance to determine user preferences for the application of space value. In this case, the shopping mall that is validated is the PIM which represents the shopping mall with the highest score. Users as respondents in this study were randomly selected and had visited the PIM shopping mall. Video and image screenings were shown to remind respondents of the mall space.

Based on the validation results of shopping mall by users satisfaction, it is known that the values obtained are not much different from the values set for each space value factor. In general, the average results assessments are tenant placement with a score of 6 equal to the space value of the mall; Space accessibility received a score of 6, slightly different from the score of 7 for mall space value; and visitor visibility gets a score of 7 which is the same as the space value. Meanwhile, the variance of the three factors, namely tenant placement, was 1.22; accessibility 2.00; and visibility 1.33.

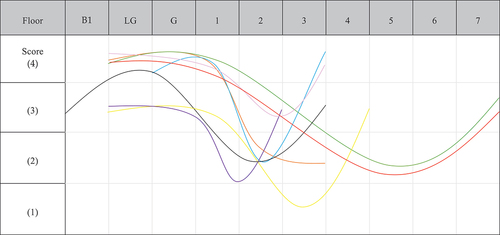

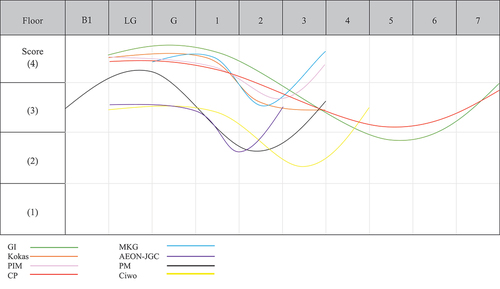

This study identifies the space in a shopping mall based on the density level on each floor. The horizontal line is the floor level, and the vertical line is the crowd-level score. Score 4 = high, and 1 = low. Illustrations are presented in of the level of crowds on weekdays and on weekends.

Based on , it can be seen that the shopping mall space for the middle-level floor is a space that has a low value, which means it is less attractive to visitors. The first three floors are the spaces with the best value, along with the top floor, the entertainment area, and the food court area. We need to know that all the shopping malls reviewed are adjacent to offices, so on weekdays and weekends, there is little change in the density of visitors, especially in the food court area. Visitors enjoy lunch on weekdays and get together with family on weekends.

5. Discussion

5.1. Tenant placement

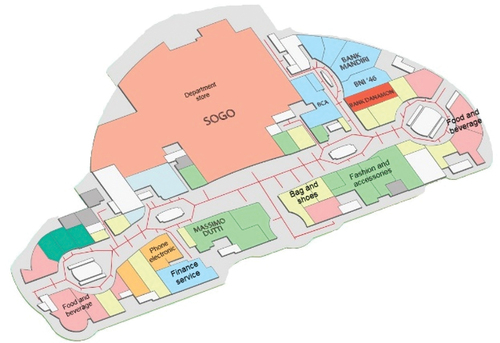

Several factors are highlighted in the formation the optimal of space values as a result of this research. The departmentalization strategy is a tenant mix strategy used in shopping malls in Indonesia. The results confirm the analysis of Yuo and Lizieri (Citation2013) that the departmentalization strategy supports shopping malls with more than four floors. This makes it easier for visitors to find their way without lessen the purpose of shopping. However, the dispersion strategy for the mix of tenants with a height below four floors does not apply to shopping malls in Indonesia, such as what happened to PIM 1 and MKG 1 shopping malls, which have three floors. This shopping mall has tenants of the same type still grouped in certain areas. This may be due to other influencing factors, such as the behavior of visitors who favor departmentalized store groupings or adopting a uniform tenant mix strategy because these malls are generally malls that have undergone development. In addition, anchor tenants such as department stores are usually grouped with fashion and accessories shops (). In contrast, supermarkets on the lower ground floor are grouped with non-anchor store types of food and beverage. This finding is consistent with research by Hirsch et al. (Citation2016) that the merger of supermarkets with other kinds of food stores, such as drug stores and bakeries, has a high relationship value; on the other hand, the relationship between department stores and food stores is relatively lower.

The layout of rental spaces, such as anchor tenants in all shopping malls reviewed, are mainly located at the end of the corridor with small tenants along the spaces connected to an anchor tenant. Kokas, PIM, CP, and PM shopping malls also place mini anchors between non-anchor stores, which are useful for attracting visitor traffic through small shops so that non-anchor tenants get a spillover effect through the presence of anchor tenants (main and mini anchors) which is more distributed. While GI, MKG, AEON, and Ciwo shopping malls take advantage of non-commercial space by placing vertical transportation around non-chor stores where accessibility occurs. This is done to support increasing the value of stores around vertical transportation areas through visitor flow. As mentioned in research by Omer and Goldblatt (Citation2017), visitor movements will rise to places with easy accessibility.

This study observes the placement of the food court area, which is divided into two types. They are placing a food area or food court on the lower floor (LG) as implemented by the Kokas shopping mall and placing a food court area on the top floor as found in GI, PIM, MKG, AEON, PM, and Ciwo shopping mall. Placement of the food court area as explained in the study by Yiu et al. (Citation2008) that the food court area generally rents a larger space, and often, the large space is on the top floor. In this context, the shops located on the lower floors are expected to receive a positive spillover effect through the presence of the food court. The supermarket area can always be found on the lower ground floor of the shopping mall, along with various services such as financial services, beauty and health shops/services, and food product shops. The placement of this location is also closely related to the ease of accessibility for visitors close to the parking lot. Another similarity is that branded shops (fashion and accessories) that sell impulse goods can always be found in the main lobby (Yiu, Xu, and Ng Citation2008). According to Zhou and Liu (Citation2021), the lobby space must be as attractive as possible to create a visual experience for visitors. This floor is the area that has the highest traffic levels because it is adjacent to the shopping mall entrance. This can be understood by placing exclusive brand shops to make it easier for visitors who come with their vehicles to shop as short as possible, especially when these shops release the latest items.

5.2. Accessibility of space

The second factor is accessibility in the space of the shopping mall. This study found that one of the optimal spatial divisions applied in shopping malls is the ease of reach vertically and horizontally. In a vertical direction, that is through vertical transportation layouts that are easily visible to visitors to reach shops easily (Zhou and Liu Citation2021). Three of the eight shopping malls reviewed have the same uses of escalators and elevators, as found in PIM, CP, and MKG shopping malls (). PIM and MKG shopping malls take advantage of escalator placement, and the elevators are on both sides of the atrium, while the CP, escalator placement is at the end of the atrium space, while the elevators are on the middle side. In short, the three shopping malls have vertical access that is easily visible to visitors. This makes it easier for visitors to reach shops easily (Forgey and Goebel Citation1995; Ortegón-Cortázar and Royo-Vela Citation2017; Yuan et al. Citation2021). It is stated that visitor preferences for shopping mall spaces can vary; for example, there is shopping behavior that is carried out to enjoy the shop environment, then the use escalators are more likely to be used, and some are shopping in the shortest possible time so that visitors prefer to use elevators to arrive on the intended floor quickly. While in the horizontal direction, PIM, MKG, and AEON JGC utilize connecting bridges between corridors so that the value of store increases through visitor flow (). Differences in visitor preferences for space demand that shopping mall developments must be able to meet design criteria based on various community preferences for shopping mall spaces (Büyükşahin Citation2022).

Figure 10. Ease of vertical accessibility through vertical transportation (escalators and elevators) in MKG (a); ease of horizontal accessibility through the use of bridges between corridors in PIM (b) (source: Author archives).

Tenants in areas where visitors rarely pass the store tend to have low sales levels. These areas are referred to as isolation zones because of their small affordability. To encourage commercial space efficiency, shopping mall design must ensure that stores are strategically placed and, in such a way, manage visitor flow patterns optimally. In this case, if the shops can only be accessed via escalators, it can indirectly affect visitors’ interest, especially those who require exceptional mobility. On the one hand, it is also important to understand that visitors need travel routes within the shopping center space that are easy to remember and do not cause disorientation (Lu and Ye Citation2017).

5.3. Visibility