ABSTRACT

Confucianism has shaped traditional Chinese urban patterns and sustainable housing development, resulting in a fusion of architectural styles across China and neighbouring regions. As previous research has focused on the physical and environmental aspects of sustainable urban environments and housing, the evolution of spatial narratives has been overlooked. This study explores the significance and influence of Confucian narratives in urban streets and juxtaposed courtyard houses, specifically in the Mingfucheng area of Jinan, Shandong Province. By employing a qualitative approach through semi-structured interviews with residents, the study explores architecture and hutong spaces. The findings highlight the positive impact of Confucian concepts on residents’ lives, spatial behaviour, and spirituality. It also addresses the challenges and opportunities in the process of urbanisation and rural revitalisation. This research provides a narratological perspective on the sustainability of culturally influenced traditional architecture, contributes to the knowledge on courtyards and hutongs, and suggests sustainable strategies for architectural culture and heritage conservation.

1. Introduction

China’s rapid urbanisation process has prioritised economically oriented urban planning strategies, leading to the decline of traditional architectural development. Even when some buildings are renovated and preserved, there is a homogenisation of styles. In northern China, the hutong and courtyard cultures have experienced destruction, challenges, and discussions about survival, but future direction is still unclear. Cultural heritage is not only a sociohistorical product but also an important site for capital accumulation (Wang et al. Citation2023). In recent years, a number of relevant Chinese practices have been shown to outperform those of developed Western countries and are forming a new paradigm (Zhang and Zhou Citation2014). Ma et al. (Citation2022) argued that in recent decades, China’s society has changed substantially through urbanisation and the development of the construction industry, providing a solid force for social progress and sustainable development.

Consequently, there have been many calls against this expedited real estate development, as well as conceptual disagreements in terms of land and building ownership (Pils Citation2014). Furthermore, Han (Citation2015) noted that an urban area can be understood as an integration of many journeys through historical innovation, growth in the midst of stumbles, and regeneration in the wake of destruction, as a result of the combined efforts of several generations. However, this new fragmented environment has led to a loss of shared memory and culture, creating an issue of urban alienation. Analyses of urban theories cover a number of aspects, such as the shift from traditional kinship societies to modern industrial societies with independent roles (Kemple Citation2007); social organisation in the city based on kinship (Bruhns Citation2020); materiality, sociality, and spirituality (Lefebvre Citation1992); and the demonstration of human values by urban services and life (Jacobs Citation1992), and so on. Cultural rights are a prerequisite and basis for the participation of individuals or groups in spatial activities and the enjoyment of cultural achievements. The lack of attention to spatial quality in turn affects traditional architectural heritage.

In recent years, many studies have been conducted on architectural heritage and sustainability regarding architectural reuse, gentrification, energy-efficient buildings, and the development of sustainable building materials. Researchers have primarily focused on the morphology and technological renewal of the development of houses, and few studies have examined the cultural logic and connotations that have shaped this phenomenon. As Sqour (Citation2018) noted, restoring humanity in architecture can produce humanitarian architecture; otherwise, architecture will bring alienation to the environment and human beings. Therefore, the exploration of humanity is urgently needed for our present heritage and sustainability goals. It has been shown that architecture is a unique cultural component of a country, like language, art, music, or cooking (Darmayanti and Bahauddin Citation2020). AL-Mohannadi et al. (Citation2023) suggested that through architectural identity, societal culture and people’s way of life can be equally reflected. In Chinese civil society, interactions are based on familiarity between people, such as daily chats, gift-giving on festivals, door-to-door visits, fairs, weddings, funerals, and other events reflecting cultural characteristics. People’s social behaviours in these spaces help map the Chinese culture. If only one Chinese person is chosen to represent the long history of Chinese culture, Confucius would be the best choice (Yu Citation2021). Confucianism’s “Ren and Li” promote long-lasting peace and the prosperity of families, cities, and nations, which involves coexistence through benevolence, generosity, and propriety. The doctrine of the mean, which advocates impartiality, symmetry, and regularity, likewise has a profound influence on the planning of courtyards and neighbourhoods. The integration of Confucianism into Daoism and the ideas of “unity of heaven and humankind” and “harmony” forms a unique architectural concept in China. Confucianism has been present throughout most of China’s history, and its influence on architecture and urban patterns has continued to be iterated and improved. However, the study of space and planning through the lens of Confucianism has been limited to the concept of Confucianism itself, and the fascinating architectural components and narratives have not been adequately discussed.

Through analysing and reading the existing literature, the origins and development of Confucianism in Shandong, as well as its influence locally and nationally, are understood. However, there is still a lack of discussion on the exploration of the value of Confucian culture in local cities and architectural forms. Jinan, as the capital of Shandong Province, is a feng shui treasure, where cultural, political, and economic elements converge. The Mingfucheng area is also the core location of the old Jinan city, supported by a deep heritage, which is why it was chosen for this study. Jinan is a northern city in China with a temperate monsoon climate. The local environment is therefore characterised by four distinct seasons: a changeable climate in spring with high winds from the southwest, rapid surface warming, high evaporation, low precipitation, and frequent droughts; a hot and humid summer with concentrated precipitation and occasional rainstorms and hailstorms; a less cloudy and rainy autumn with high altitude and sporadic autumn rainstorms; and a winter with scarce snow and rain with more northerly winds and cold and dry conditions. Overall, the dual role of climate and culture directly influences people’s settlement patterns.

This study aims to explore the assemblage forms of floating hutongs and diminishing Confucian courtyard narratives. This research methodology is utilised in a number of architectural typologies, as suggested by Gokce and Chen (Citation2018), where many cities suffer from a typological crisis and loss of sense of place. However, this present study builds on the concept of narrative and constructs a research framework to serve as a platform ().

From the standpoint of narrative research on sense of place, this study combines the cultural connotations of architectural and spatial components with Confucian narrative and behavioural research through the analysis of three aspects: place attachment, place identity, and place dependence. In addition, the hutongs, and a courtyard in the Mingfucheng area were observed using narrative analysis to capture spatial images and spatial rhetoric. Thus, inheritance strategies to achieve the goal of sustainable development are collated for a better recording of these narratives of architecture and life. At the end of the paper, corresponding guiding recommendations are made, both in terms of spatial design and land planning and regarding Confucian cultural heritage and architectural sustainability.

2. Methodology of narrative analysis

This study adopts a qualitative approach based on narrative to better interpret the spatial texture of hutongs under the influence of Confucian culture and the courtyard values linked to it. Narrative stems from a natural means of transmitting experience, a concrete way of solving life’s problems, and creating a rational order from experience. This not only reflects the present but also shapes people’s view of the world (Béné et al. Citation2018; Moen Citation2006). In research in the field of cities and architecture, narratives can generalise the value systems of traditional culture, rituals, and architectural forms. With the rise of industrialisation and modern movements, narratives can facilitate a more effective discussion about the past and future of architecture (Martek et al. Citation2018). This, as one of the qualitative research methods, requires observation and interviews, among other means, to better understand the specific relationship between these elements of urban streets, architectural ensembles, and people. Shandong Province is the cradle of Confucianism and Jinan City is the capital of Shandong Province. Therefore, if Confucianism is viewed from a developmental perspective, it is socially and culturally significant to explain the impact of Confucianism on architecture, space, and urban patterns as well as interpret the Chinese attitudes of etiquette, the Doctrine of the Mean, and harmony and co-prosperity in life (Rong and Bahauddin Citation2023b). Overall, the enrichment of the spirit of place and sense of place in the context of storytelling (Eggan Citation2018), coupled with the unique metaphysical cultural context of Confucianism, are rare assets and act as modes of thinking for planners and designers to create more impactful designs. The methodology and narrative analyses of this study are elaborated in the following subsections.

2.1. Study area and data sources

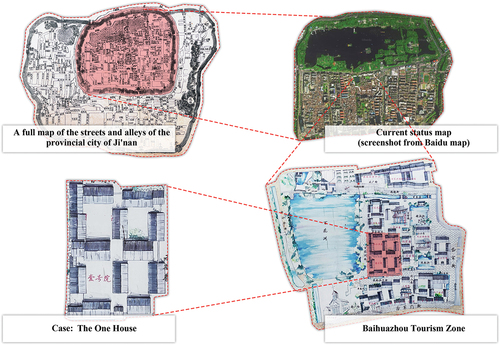

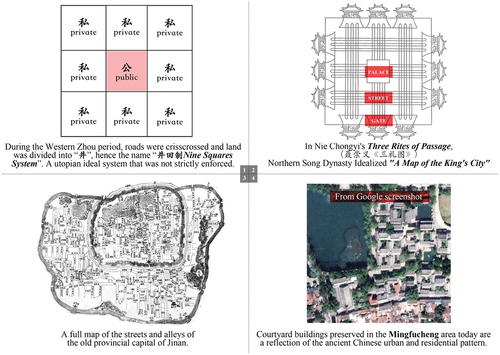

Jinan, as a blended city of tradition and modernity, has a unique urban structure that has created a residential heritage and local culture characterised by spring water. It is bordered by Mount Tai and lays south of the city of Qufu, the birthplace of Confucianism; the Yellow River and a historical transport hub sit in the north; and there is a a long, narrow east-west stretch in the centre of Shandong province. Thus, the whole area incorporates mountains, water, lakes, springs, rivers, and cities. Confucianism thus created a city that reflected the correct cosmology and order (Tceluiko Citation2019). Jinan is a city of springs, and the saying “spring water runs throughout the house, willow in each home” is well known in Feng Shui; houses and courtyards are built along waterways and neighbourhoods and streets forming an intricate system of hutongs, just like the flowing springs. The city’s urban pattern also has historical roots (). During the Western Zhou Dynasty, the “Nine-Square land ownership system (井田制)”, an idealised state, divided the city into public and private areas. The map of the king’s city with its gates, streets, and palaces can be seen in Nie Chongyi’s (聂崇义) Three Rites Map (三礼图) of the Northern Song Dynasty, which can be viewed as a blueprint for the construction of Chinese cities throughout the ages. The combination of Confucian ideas on rituals and Feng Shui doctrines thus contributed to the establishment of the city model.

Figure 2. The evolution of Confucian ritual thought in urban planning and the maps of the study area.

The Mingfucheng area is the only place in Jinan where a juxtaposition of buildings linked by flowing hutongs still exists. The Mingfucheng area is a combination of the history of the north and the beauty of the water towns of the south. The buildings all have courtyards of varying sizes depending on the topography of the different underground springs. Further, outside the main gate are hutongs, which are connected to the springs. Over the course of six hundred years of history, this basic pattern has been preserved. In this study, the Mingfucheng area is taken as the object of investigation (see the bottom of ). The planning of the Mingfucheng area in history has essentially remained the same, and thus still reflects the ideas of Confucianism. Therefore, within this district, the cultural characteristics of the urban street layout, the linked courtyard-style buildings, and the sense of spatial order under the influence of Confucian narratives are explored. The data for this study comes from two main paths. On the one hand, the data is mainly collected through field research and observation records of the site, and the visual content favours the analysis of spatial images and the order of arrangement. The other method is through face-to-face interviews to identify content related to Confucianism and architectural narratives, thus facilitating the analysis of spatial rhetoric.

2.2. Semi-structured interviews

The focus of this study is to identify the characteristics of building layouts and the environment in the Mingfucheng area of Jinan, understand the living conditions of today’s residents, and explore traces of history. Among the narrative methods, semi-structured interviews are one of the most effective ways to contextualise questions, clarify them, and understand phenomena (Bevan Citation2014). Among them, this study focuses on the questioning of one local expert working and living in Jinan, one building caretaker and one passer-by (both residing here) to provide different perspectives.

Therefore, to address the research objectives, the interview outline was set to encourage interviewees to share their personal stories, experiences, and perspectives. Doing so allowed for a question-centred approach that aided an egalitarian dialogue between the interviewer and the interviewee (Döringer Citation2021). The specific interview questions are listed below:

How can we identify Confucian-influenced urban patterns and courtyard architecture?

What are the characteristics of the Confucian courtyards and hutongs in Jinan?

How do courtyards affect the patterns of buildings, both urban and rural?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of a local building with a courtyard compared to those without a courtyard?

What do you think of the internal and external spaces and circulation system of the traditional courtyard? Do they have any influence on contemporary architecture?

Do you think the residents are aware of the local identity of the building they live in? Do they consciously display a spatial narrative?

People are not as close to their neighbours nowadays; can the courtyards linked by hutongs improve this?

With the current liberalisation of China’s population policy, will the pattern of the courtyard be suitable for future family patterns?

How can the philosophical appeal of Confucian culture be brought into play and used in contemporary courtyard design and urban street art?

2.3. Observation

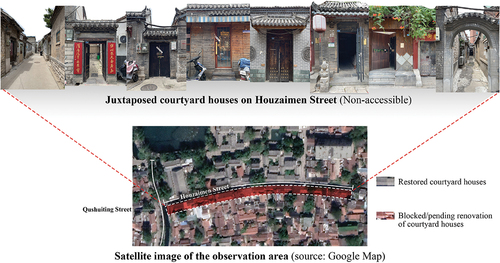

Understanding a site or design context is usually achieved by collecting information through on-site observation (Lukman and Sahid Citation2021). In this study, the researcher walked through the hutongs of the Mingfucheng area, observing and photographing the neighbourhood environment, landscape, and architecture. Observations need to be recorded over a long period of time, and according to the qualitative research method, the period of presence should be long. Therefore, the observations for this study were carried out three times between 2021 and 2023, covering all four seasons. The observations revealed a public notice indicating that the Mingfucheng area will be conserved and renovated, with structures of high heritage value and integrity intended for conservation, and others for demolition. As of the first half of 2023, many households have voluntarily moved into resettlement houses, and the old houses have been sealed so that researchers are not granted permission to enter. Buildings without people are like human beings without souls: lacking vitality and hope. Eventually, a courtyard-style building called One House was identified, and the Houzaimen Hutong in which it is located together formed the focus of observation for this study. The collected data contains building archives, building images, floor plans, elevations, etc. The overview of the hutongs in the Mingfucheng area and the basic appearance of the courtyard building are presented in .

2.4. Analysis of spatial images and rhetoric using the narrative analysis of points, lines, and planes

Since this study is qualitative research on the urban landscape pattern and courtyard architecture from the perspective of Confucian culture, it is appropriate that narrative analysis has been chosen as the method of data analysis. This is because Franzosi (Citation1998) has noted that narratives are full of sociological information and that most evidence about experience is in narrative form. Moreover, their interrelationship with architecture is at the centre of the stories people tell about their connection with the land, and the puns are growing more and more important from a practical and academic point of view (Pavlenko Citation2008; Psarra and Grajewski Citation2000).

Narrative analysis is concerned with two main aspects: the storyteller and the story itself. For this study, the narrator can be identified as the interviewees and the discourse of Confucius, while the story itself draws on spatial forms, structures, and components to better analyse the physical real world and conceptualise the ideal spiritual world. presents two important elements of analysis: spatial images and spatial rhetoric. Within the scope of narrative, the environment, facilities, and decorations, as well as the modelling of components, are used to explore the sense of harmony between humans and nature emphasised by Confucian thought in space. The geometric significance of “points, lines, and planes” in the hutongs and courtyards of the Mingfucheng area is philosophically considered in the context of analysing the concepts of spatial sequential hierarchies, environmental and emotional tendencies, and good neighbourliness.

Table 1. On the two dimensions of narrative analysis, namely spatial images, and spatial rhetoric.

3. Results and discussion

This section is a summary and discussion of the findings from the observations and interviews. The first is an analysis of the hutong as a dynamic and flowing space. Next is an analysis of the architectural complexes linked to the hutongs, which includes the constitutive principle of the transitional grey zone, and the environmentally friendly courtyard space shaped by Confucian culture. This is followed by an analysis of the relationship between hutongs and courtyards, with the aim of exploring and discussing the cultural value of this urban and architectural pattern and its possibilities for the future of the human environment. Finally, there is a discussion of the narrative environment, which verifies the significance of Confucianism for the sustainable development of residential life, and strategies for the transmission of this spatial narrative.

3.1. Analysis of the dynamics of hutongs

Taking the Mingfucheng area as an example for specific analysis, due to policy regulations, a large part of the courtyard buildings in this area have been blocked off and the residents have moved to relocated houses, which are in a state of idleness and therefore inaccessible. Nevertheless, it is possible to discern the general development through the observation of satellite images. In turn, preliminary type analysis as well as spatial diffusion analysis was carried out in the flowing and vivid hutongs. The specific images and actual observations are shown in .

The most obvious contrast is the location where Qushuiting Street and Houzaimen Street connect. Amongst them, Houzaimen Street is 406 metres long and 4.6 metres wide, with a combination of asphalt and flagstone pavement. Here, courtyard buildings and hutongs are restored and accessible, and these two streets are known as a vibrant hutong. Utilising data on urban patterns can effectively help to generate different narratives and discourses for the concept of hutongs in this study (Béné et al. Citation2018). The term hutong, as found in the investigation, is defined as narrow alleys connecting courtyard-style buildings of different sizes on both sides. Hutongs are traditional neighbourhoods that are being dismantled as cities rapidly grow (Xu et al. Citation2022). The design of the hutongs protects the privacy of the residents as well as wards off the cold winds. Based on observations, in the Mingfucheng area, abandoned courtyards and renovated courtyards are connected by common hutongs, which is a style of architecture that is not too distant from modern high-rise buildings ().

However, there are still dynamic effects embedded in the hutongs; pedestrians and cyclists cautiously pass through these areas. Yang (Citation2016) argued that due to the way in which the courtyards were designed to separate the private lives of the residents of the hutongs from those of the passers-by outside, they are also a place where the residents can live in harmony with themselves and nature. The interviewees gave their opinions on the matter:

Regular hutongs are more common in northern China. As far as I know, Beijing has preserved more hutongs. In Shandong Province, there are still some old hutongs in the Mingfucheng area of Jinan and Linqing in Liaocheng, but they are now starting to decrease.

In fact, there are many functional hutongs. In addition to daily consumption, hutongs also host weddings or funerals. For example, in the old days, matchmakers introduced children from two families to each other and matched them. Sometimes they would go through the hutong to see if the gates matched, such as the decorations, the height and size of the thresholds, and so on. No one seemed to care whether the couple was willing or not, but nowadays, of course, they don’t refer to these architectural parts to find out the status of the family. In addition, at the time of the funeral, the hutong is always full of people, to see whether the children of this family show filial piety … However, now that the city does not see this scenario, the rural areas still retain some. There is also the fact that on New Year’s Day, the closer neighbours would walk the streets and pay their respects to each other, whereas nowadays most of us don’t go out because we don’t know each other very well …

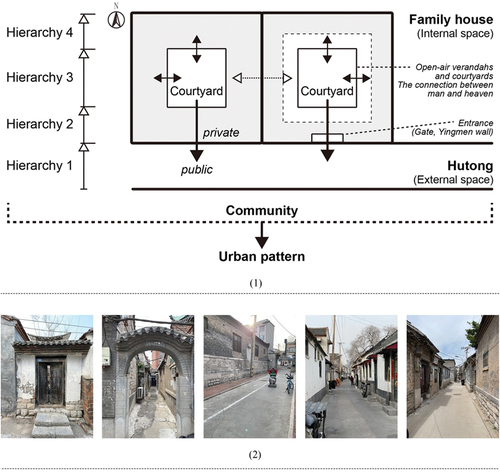

The use of hutong space is a key condition for activating the vitality of life. In other words, the existence of hutongs also represents, to a large extent, the concept of good neighbourliness and harmony advocated by Confucianism. Therefore, the basic principles of the composition of vibrant hutongs and courtyards can be summarised from the observation and interview data of the hutongs (part (1) of ). When analysed geometrically, the courtyard is seen as a point. The juxtaposed courtyard buildings are also combined to form a line and the space between the lines is called the hutong. The Mingfucheng area is formed from the combination of a point and a line at the intersection of the plane.

Table 2. Dynamic rationale of hutong and courtyard spaces.

However, this is only an idealised urban pattern, as described in the previous section (). In fact, the actual buildings and hutongs are much more complex, and this web of interconnections creates the culture of Jinan’s ancient city. The red areas as shown on part (3) of , they are the rehabilitated courtyards and hutongs, which gradually find a sense of order in comparison to the blue colours located at the southern part of the site. In traditional residential areas, hutongs not only connect housing and community environments but also serve as an extension of the residential environment; therefore, in the next section, the courtyard is studied further.

3.2. Towards the enclosed Confucian courtyard

To enter the courtyard from the hutongs, a welcoming wall is set up to create a better psychological feeling of comfort. Observations show that not only are the hutongs private, but the enclosures around the courtyard buildings are also secluded. Ren and Zhang (Citation2022) noted that the air of formality in the courtyards gives the occupants a sense of peace and tranquilly as well as a strong sense of life. In addition, the enclosure helps to maximise family privacy and grants protection from noise, dust, wind, and rain. It also meets the need for thermal comfort in terms of daylight and ventilation (Liang, Yu, and Liu Citation2021; Zhang and Zhang Citation2021). Within the Mingfucheng area, a well-restored courtyard building was further observed.

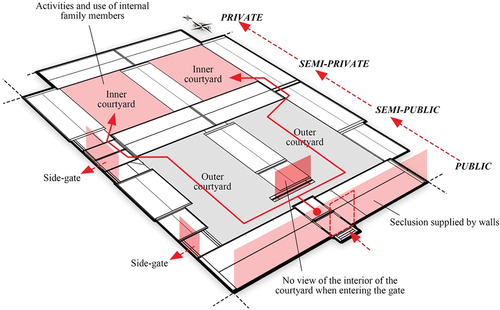

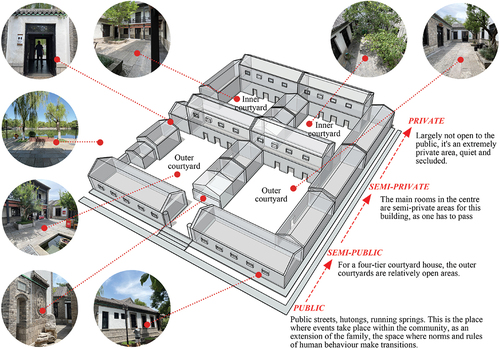

The One House is of great research value for this study given its division of private and public activity spaces (). Along the hutong is the public area and through the main gate the two courtyards are semi-public areas. This is followed by the transition corridor as a semi-private area, and finally the inner courtyard as a completely private area.

3.2.1. Cultural vibrancy of transitional spaces

The internal space of One House is layered and interconnected as one enters from the hutongs (). This is how the interviewee described it in the interview:

The Confucian-inspired courtyard is a relatively static atmosphere, where the place is composed of the bits and pieces of life. The contrast between the busy streets and the quiet inner courtyard is stark.

This section on courtyard architecture under the influence of Confucian culture will be divided into two subsections for narrative analysis and discussion: “The walls and enclosing spaces” and “Dialogue between the roof and the heaven”.

3.2.1.1. The walls and enclosing spaces

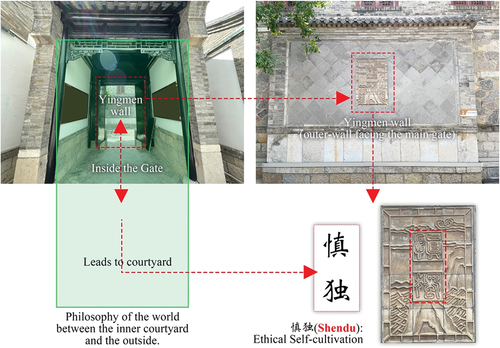

In observing the building and analysing the literature, the architecture of Confucianism has references to the concept of Feng Shui, which reflects the fusion of Confucianism and Daoism that permeates Chinese life. Before entering the main gate, the first element to be seen is the Yingmen wall. It is divided into the wall opposite the main gate, which is the wall outside the building, and the door that is visible after entering the gate (). In Feng Shui, the main gate is the entrance to “Qi (气)”, the entrance through which the family’s luck and wealth pass, so a wall in front of the entrance can make people pay attention to this “Qi”. This is how the interviewees interpreted this spatial construction and metaphor:

The doctrines of Confucianism and Daoism have always complemented each other; Confucianism has been officially adopted as the orthodox guiding principle, but it has not restricted the emancipation of the human personality, as in the case of metaphysics. The search for this state of balance is in turn a reflection of Confucianism’s Doctrine of the Mean.

Therefore, the “wall” is an iconic component of both traditional and modern Chinese architecture. The wall is inscribed with the Chinese character “Shendu (慎独)” (), which is a method of moral cultivation proposed by Confucianism. It is derived from the Book of Rites (礼记):

A gentleman is also prudent when he is alone, when there are no voices or people observing, and when seclusion is the easiest way to expose bad ideas. So, keep Shendu.

It is evident that those living in this compound wish to be reminded by these two characters before entering the courtyard and when leaving the courtyard. This reflects the Confucian philosophy of living both inside and outside of the inner courtyard.

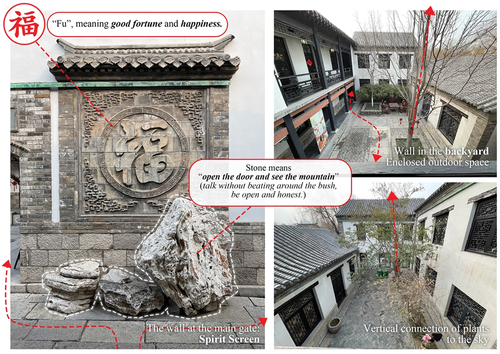

Upon entering the main gate, there is another wall in the courtyard (). This is a type of Yingmen wall, sometimes translated as a spirit screen, and is covered with the Chinese character for “Fu (福)”, which means fortune and happiness. Generally, the contents of the Yingmen wall are positive and respectful towards not only oneself but also visitors, reflecting the Confucian idea of harmony in life and friendship. The top of this wall is also modelled with tiles or eaves, signifying a connection with the heavens. One house’s Yingmen wall has stones placed underneath it, symbolising the idea of “opening the door and seeing the mountain (开门见山)”. To put it bluntly, this represents a mountain to block bad Qi or energy. In a Chinese idiom, this phrase also means “talk without beating around the bush; be open and honest”, which reflects the style of the residents. Even in modern homes, many room patterns also use this euphemistic and subtle way of blocking)” to create good feng shui inside the home, such as by placing stones or plants by the entrance door or placing the words “open the door and see the joy (开门见喜)” on the wall opposite the door.

3.2.1.2 Dialogue between the roof and the heaven. Observations revealed that the entire Mingfucheng area had a clear quality in the ridge portion of the roof, with small green tiles stacked in an overlapped manner, symmetrically from side to side, and reaching diagonally towards the sky. The ridge beast on the roof is not only an important structural link, but also a crucial decoration to promote the spiritual beliefs of the head of household. However, there are no ridge beasts in One House, and only a few houses in the Mingfucheng area can be found with small ridge beasts (). In traditional Confucian culture, there is a strict hierarchical requirement reflected in the architecture of official buildings, such as the Forbidden City in Beijing, where the roofs of official buildings are decorated in a strict hierarchical and formal manner. The decoration of folk buildings is livelier and more subjective. The table shows that many households used plants for decoration, and that roofs were beautifully carved with symbols of goodwill. This is how the respondents described it:

Table 3. Roof decoration in Mingfucheng area.

In China, some say that if in the house, the building sets auspicious beasts, the psychological burden on the occupants will become a burden on ordinary people. Beasts are difficult to subdue; the dialect calls it “pressure on the top of the head”, Psychological pressure is too much but has a negative impact. Therefore, flowers, plants, fish, and birds have long been known as the first choice of folk roof decoration.

Regarding the activation of traditional culture in modern society, Abdulali and ALShamar (Citation2023) argued that architectural heritage is historical proof of an entity that carries the culture, morals, values, and so on of a particular era, and that it is also considered to be a source of inspiration and knowledge for future generations. Even in modern times, the uninterrupted enjoyment of humans and the sky remains unabated. As Knapp and Lo (Citation2005) mentioned, the activity of worshipping heaven and earth in the courtyard, in both ancient and contemporary times, is still considered an action that will bring happiness and good luck. However, there are also interviewees who believe:

Confucius never defined what heaven is, and everyone has a different understanding of it. But what cannot be denied is that the Chinese have never changed their desire for a better life. They balanced the connection between human and heaven with the help of courtyards.

The courtyard space embodies the traditional concept of family and simultaneously maps the adaptation of human beings to the living environment. For the creation of a cultural network, the relationship between human beings and the universe can be explored in terms of architectural components, the creation of an atmosphere, and stories and legends. In Confucianism, this is called the philosophical idea of “the unity of heaven and human, the law of nature” (Ren and Zhang Citation2022). In addition, the courtyard, as the centre of the building, is also valuable in terms of environmental friendliness.

Therefore, the results of the study show the transitional space and cultural vitality aspects of this courtyard house in One House. A spatial model (as shown in ) was drawn via computer. Based on this, it was further dissected. As shown in , this resulted in a more three-dimensional understanding of the relationships between elements such as the exterior, interior, human, and sky. This highlighted the relationship between spatial components and people and contributed to operational and practical recommendations.

Table 4. One House 3D model analysis.

3.2.2. Environmental friendliness of courtyard spaces

Through the previous subsections, the spatial and cultural analyses of the dynamic hutongs in the Mingfucheng area and the One House have provided a certain understanding of the spatial and architectural components. In the following subsections, the focus is more on the decoding of the interview data in the narrative analysis.

3.2.2.1 Tales of hutongs and courtyards

The Confucian idea of “the unity of heaven and human” is reflected in the spatial form of the building, which has a relatively clear visual axis interspersed with one or more courtyard spaces. From the perspective of traditional culture, this reflects the Chinese worship of a sense of order, and from the functional zoning, the status of the various members of a family can also be seen. The past is not currently visible, but some information can be gleaned from the interviewees’ thoughts:

I’d like to say that in the courtyard nowadays, there is still a sense of humanity. I think the neighbourhood of the building and our courtyard cannot be compared… Since I know, I have not heard of anyone’s family losing things. For example, when we make a good meal at home, our parents will say to our children, “Go and bring a bowl of dumplings to the grandmother next door; it’s freshly made and warm” … All in all, they are especially honest. Do you think this has anything to do with Confucius? Of course, it does. The reason I live here is because I have a deep-rooted affection for this area.

Our neighbours here are quite good; distant relatives are not as good as close neighbours. This is what I have in mind: to take care of each other. The relationship between the people in the yard is quite good. Do not calculate against each other; there are things to do to help each other. This is the feeling of living in the courtyard… Don’t care how it is, you have people coming to your house, the door is not open, come to my house to sit down first, please feel free, as your own home can be.

Undeniably, the courtyard is a key space that should be considered when reviving architectural features of the past (Mazinanian et al. Citation2022). In fact, in all types of situations, the courtyard and the hutong space are naturally linked from internalisation to externalisation, which is equally reflected in human social relations. The collective space of the courtyard is used as an “outdoor living room”. The use of courtyards as a collection of public and private spaces strengthens residents’ community identity with the courtyard (Porotto Citation2016). The following information was provided by the interviewees:

In old Jinan, it was a great thing to live in a house with a courtyard. Having a big yard and a big house meant having a bigger family. Nowadays, people here seem to live in slums, where cars can’t drive in and gas and heating are difficult to install. Families with money renovate; after all, several generations used to live here. You see, there are some business-minded people who have converted their houses into eateries or hostels, and a lot of people like to stay here; they say they are able to escape the hustle and bustle of the city for a while…

Also, one respondent commented on the old houses in the Mingfucheng area:

I still feel that the old town of Jinan is very elegant. Thanks to the government for preserving it. My old friends and I sometimes have a drink in the courtyard and talk about family matters, which I think is quite nice. As we are getting older, we can take care of each other and help each other with things. This is the feeling of living in the courtyard.

Courtyards carry the nostalgia and attachment of local people. Confucianism focuses on cultivating one’s moral character with “self-restraint, loyalty, righteousness, benevolence, and honesty” as its main connotations. For a family, a friendly living environment can only be achieved when character cultivation and family management are integrated.

3.2.2.2 Harmony between the external community and internal family

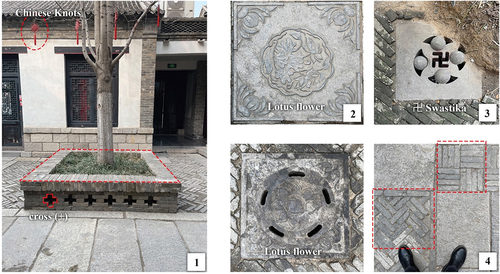

As scholar Tuan (Citation2001) has pointed out, space is dependent on the movement of place. Elements such as family, friendship, and networks of acquaintances are also believed to shape the experience of belonging, and the role of place, culture, and social environment are equally important (Vytniorgu et al. Citation2023). Therefore, in this study, it can be confirmed that hutongs and courtyards are interdependent. There are social relations in courtyards and communities that favour people’s practices and social etiquette (Hatipoğlu and Mohammad Citation2021). Evidently, culture permeates people’s lives and activities as an implicit symbol. These progressions from the outside to the inside can be explained by observation of specific details, such as floor coverings in courtyards, in terms of materials, laying methods, scales, and specifications. Hard paving is the most important material and covers the largest area. Other common materials include brick, stone, concrete, and pebbles. The stone and brick paving evoke a sense of sequence and design. These ideas reflect the family’s love of life and their pursuit of a healthy lifestyle. In short, the layout of the traditional Chinese courtyard is heavily influenced by traditional religious rituals (Mo, Yan, and Deng Citation2022). Behind the architectural form of the courtyard space is an implicit respect for rules and order, and the pursuit of detail is an expression of adherence to etiquette (Guo and Dou Citation2022). Narrative analysis of the floor pattern found inside the courtyards can further explain the meaning of Confucianism ().

Chinese Knots: a hand-woven craft. While considered a representation of ritual during the Han Dynasty, today it is a decorative craft. It is particularly popular with folk people. In Daoism, the cross (+) represents the emergence of the meridian, the yin, and the yang, as well as the complete meaning, which incorporates the doctrine of the circle of the heavens and the square of the earth.

Lotus flower is the city flower of Jinan, and the lotus root is abundant in Daming Lake, signifying the noble character of “coming out of the sludge without being polluted”. The lotus flower is a symbol of innocence, steadfastness, and purity.

Swastika (卍): embodies the inclusiveness of Confucianism, and the Sanskrit word swastika is integrated into Han Chinese culture and is considered auspicious in folklore.

The pattern of the floor tiling reflects the graphic design and aesthetic interest of the builder.

In the context of the emotional landscape within the family network, it represents the past of a family and the history of the community that form the emotional link between the current place of residence and the “family” and “neighbourhood” (Ernstberger and Adaawen Citation2023). This is consistent with the description in this section, which states that harmonious spatial relationships are essential for achieving environmentally friendly goals. Therefore, it can be argued that this neighbourly connection from the floating hutong to the enclosed courtyard was achieved under the influence of Confucianism.

3.3. Narrative environmental aspects

Through the description of the above, it is clear the concepts of narrative and environment are constantly mentioned and appear in the study of the Mingfucheng area. Therefore, the continued analysis of the narrative environment can help provide insights into the sustainable development of the living space in Confucianism, as well as the inheritance strategy of this spatial narrative.

3.3.1. Sustainability of living space in Confucianism

Considering the sustainability of the living environment, it is also crucial to improve indoor thermal comfort and other issues. The presence of courtyards and hutongs improves and solves climatic problems. Observations documented the courtyard space enclosed by the wall (). This space influences the microclimate within the courtyard as well as the interior, with greenery planted towards the sun and rain, and sunshine, wind, and snow from the sky scattered throughout the courtyard to represent the connection that people have established with the sky. The height of the walls affects the natural light in the courtyard, and the high walls function as a defence and separation. This is an area of activity unique to the head of the household where people look up to the sky, and therefore sometimes this space is called a “patio”. In addition, it is also possible to see the courtyard from a bird’s eye view and it accommodates dozens of people, which confirms the freedom of the living space of the courtyard and regulates the sustainable state of the environment.

Courtyards and hutongs, as basic architectural elements within each residential unit, play an important role in terms of their orientation, enclosure, and hybridisation of natural elements. This also proves their effectiveness in the climatic and social aspects of the built environment (Abass, Ismail, and Solla Citation2016; Rong and Bahauddin Citation2023a). The layering in this sustainable space can provide certain insights for designers and planners ().

Figure 12. Hierarchical relationships from inside the family to outside hutong spaces to community to urban patterns.

The courtyard, as the most basic component, is key to the connection between humans and the sky. It extends outwards to a complete courtyard house, surrounded by houses of different levels, which in Chinese culture are generally said to “sit on the north side and face south” to ensure sufficient sunlight hours. The gate on the south side is the grey area between the private and public spaces, as described earlier with the entrance and the Yingmen wall. As a public activity area, the hutong is at the lowest hierarchical level, namely hierarchy 1. The higher the hierarchy, the more private the space, and the more important the people living there. The rows of juxtaposed houses together form a network of neighbourhoods connected by hutongs (). There is a necessity to study the sustainability of living spaces under Confucianism. For the people who live here, the trend of urbanisation is powerless, as one of the interviewees described:

Occasionally when I’m tired, I look up at the sky in the courtyard and consider what I’m doing. I don’t know what kind of gods and goddesses there are in the sky, and I can’t tell you who God is, and I don’t want to know what this sky means. I just think that if I do more good things and live my life honestly, God will look after me and my family.

Based on the interviews, observations, and data analyses, it was learned that for the hutong and courtyard complexes, progressive conservation at different levels of space layer by layer is an effective approach. Further, the aspect of inheritance strategies for spatial narratives is discussed in the following section.

3.3.2. Inheritance strategies in spatial narratives

Kamelnia et al. (Citation2022) have argued that courtyards have a unique integrative and controlling value and play an important role in shaping the social logic of the traditional house, which can be expressed in terms of their number, location, accessibility, etc. This study also confirms this view through observation and analysis, and according to the results, a sustainable development strategy can be proposed (). In the initial research framework, it was noted that this study is a narrative-based exploration and that a detailed analysis of the three aspects of sense of place can effectively achieve the objectives. The trend of urbanisation is inevitable; however, economic development-oriented planning has intensified the dichotomy between real estate and traditional forms of living. It is also evident from the observations that urban patterns have changed. The sense of local attachment felt by the residents could be felt in the interviews as population movement, residential instability, and historical memories haunted the Mingfucheng area. Neighbourhood interaction and faith building are particularly valuable as the buildings linked to the hutongs have been altered or deserted, which poses a challenge to local attachment. People who have always lived here are able to perceive the pace of modern life, which can play a role in the tensions of the urban community (Wang et al. Citation2023). For the embedded cultural and narrative aspects of Confucianism, place identity can be defined. Confucianism originated in Shandong Province, and Jinan, as the capital city of the province, is exemplary for other cities in Shandong Province. Therefore, these explorations in the Mingfucheng area of Jinan are inspirational for neighbouring cities. Overall, studying the three aspects of place attachment, place dependence, and place identity can provide further knowledge to decision-makers with which to explore socio-cultural aspects and adjust development strategies, accordingly, thus actively furthering the sustainable development of the city.

4. Conclusion

This study explores the relationship between spatial structure and its functions under the concept of Confucian culture, using the hutongs in the Mingfucheng area of Jinan City, Shandong Province and a courtyard building as the objects of study. A narrative approach is adopted to observe and analyse the images and rhetoric of space, leading to a qualitative study in the courtyard and the hutong. Finally, the spatial order of point, line, and plane is analysed and sorted from the perspective of geometric visualisation. Combined with the interview data, sustainable strategies targeting environmentally friendly community building as well as coping with spatial narrative inheritance are finally distilled. This study provides recommendations along the dimensions of theoretical advances, methodological contributions, practical applications, and policy implications.

(1) In terms of the theoretical aspects of hutongs and courtyards:

Affirm the contribution and value of Confucianism to urban and architectural patterns, deeply explore the connotations of Confucianism, and reflect them in the use of space.

The sense of order, hierarchy, and the doctrine of the means proposed by Confucianism can be used as an important guiding ideology and practical guideline for the sustainable development of courtyard architecture.

Previous research on Confucianism has been independent and abstract, lacking a certain vehicle for people to understand this brilliant culture. The study of Confucianism in this research integrates interior design, landscape architecture, urban planning, and other disciplines, which is a win-win sustainable development of the discipline. It not only provides a narrative medium for Confucianism, but also brings more possibilities and theoretical support for the development of urban architecture.

(2) In terms of the methodological aspects of hutongs and courtyards:

The analysis of courtyard spaces, a particular sustainable building type, can be an effective antidote to the contemporary problem of urban alienation, effectively easing the relationship between residents. In addition, the dissection of indoor and outdoor components is an effective way to conduct research related to architectural typologies and has implications for the construction of architectural spaces.

This study takes the unique shape of the hutong and its connected courtyard houses as a research method. It is a feasible tool for urban planners and designers. It is an effective way to intervene in the study of space without destroying the urban form. From plane to linear and then to point, the method allows for linking different spatial scales and explores the sustainability of tradition and modernity in a relatively conservative way.

(3) In terms of the practical aspects of hutongs and courtyards:

The housing model featuring the home as the basic unit and neighbourhood interaction can serve as an idea for designers and planners. By building a positive sense of place, it is possible to enhance the community’s atmosphere.

Advocating the importance of the original festivals, customs, and beliefs in courtyards and hutongs is a way to pass on national confidence and enthusiasm for life.

The study of traditional settlements in terms of the progression of spatial geometries from “point” to “line” to “plane” is feasible and can facilitate the conservation and planning of areas in northern China or areas influenced by Confucian culture.

The rehabilitated courtyard residential neighbourhoods of the Mingfucheng area can be used as a model for the renovation of old districts in contemporary cities. The ideas and concepts of Confucianism explored in this study are a practical way of applying them to the practice of urban planning, landscape sustainability and architectural conservation.

(4) In terms of the policy aspects of hutongs and courtyards:

The act of demolishing and rebuilding buildings in hutongs is not recommended; existing features should be maintained, and historical traces should be preserved in restoration.

Creating a transition space between the old city and the modern area reduces the sense of spatial experience and protects the quality of life of the inhabitants.

Incorporating local cultural and landscape characteristics into urban planning decisions can help achieve sustainable architectural and urban development based on the preservation of cultural heritage.

5. Limitations

This study is a pioneering attempt at the development of local Confucian culture and the discussion of architectural space in Shandong. Confucianism has influenced China and East Asian countries, not only at the level of thought but also in the inspirational way architecture is used as a spatial vehicle. The insights presented in this study can point to a feasible direction for the study of Asian architecture, where designers or researchers draw on Confucian philosophy, compare and analyse it with their local cultures, and thus explore more topics of urban and architectural heritage to contribute to the development of architectural civilisation.

However, there are still limitations to this study. As mentioned in the text, this exploration focused on the Mingfucheng area in Jinan, Shandong Province, where many of the houses have been blocked off or their residents relocated. For example, in these courtyard houses from No. 1 to No. 109 Houzaimen Street, there are only seven converted drinking or handicraft shops waiting to be sublet, leaving the rest of the housing unoccupied and abandoned, which is regrettable. Therefore, in future research, it is necessary to look more thoroughly into the planning authorities to understand the planning process, architectural history, and cultural imprints of the residential areas, to analyse horizontally the differences between the various hutongs and courtyards, and to make further efforts to complete the research contribution.

Acknowledgements

The qualitative interview data involved in this study was in accordance with all relevant national regulations and institutional policies in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. It was also approved by Jawatankuasa Etika Penyelidikan Manusia Universiti Sains Malaysia (JEPeM-USM). The research protocol code is USM/JEPeM/PP/23010134, and approval is valid from 23rd May 2023 until 22nd May 2024.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Weihan Rong

Weihan Rong is a Ph.D. candidate in Interior Architecture at Universiti Sains Malaysia. He obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree from Shandong Jianzhu University, China, received a M.A. in Narrative Environments from Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London, UK. His research interests fall in the field of environmental art design and spatial narratives. In particular, he studies the sustainable development of architectural stories, materials, and techniques in the context of cultural influences.

Azizi Bahauddin

Azizi Bahauddin is a Professor in Interior Architecture at the School of Housing, Building and Planning, Universiti Sains Malaysia. He obtained a Bachelor of Architecture degree from Texas Tech University, Texas, USA, reveived a M.A in Interior Design from De Montfort University, Leicester, United Kingdom, and a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) degree from Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, the United Kingdom. His main research areas focus on Art and Design, especially on Cultural issues on Ethnography and Phenomenology and in Architectural and Cultural Heritage.

Mengyun Xiao

Mengyun Xiao is a Ph.D. candidate in Education at Universiti Sains Malaysia. She obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree from Xuchang University, China, reveived a M.Ed. from Liaocheng University, China. Her research area focuses on arts and culture education. Especially about cultural thought and educational practice, such as the influence of Confucianism in Shandong in localisation.

References

- Abass, F., L. H. Ismail, and M. Solla. 2016. “A Review of Courtyard House: History Evolution Forms, and Functions.” ARPN Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 11 (4): 2557–2563.

- Abdulali, H. A., and H. A. H. ALShamar. 2023. “Lost and Added Values in Conserving Architectural Heritage: Insights from Iraq.” ISVS E-Journal 10 (1): 135–152 .

- AL-Mohannadi, A., R. Furlan, and M. Grosvald. 2023. “Women’s Spaces in the Vernacular Qatari Courtyard House: How Privacy and Gendered Spatial Segregation Shape Architectural Identity.” Open House International 48 (1): 100–118. https://doi.org/10.1108/OHI-01-2022-0011.

- Béné, C., L. Mehta, G. McGranahan, T. Cannon, J. Gupte, and T. Tanner. 2018. “Resilience as a Policy Narrative: Potentials and Limits in the Context of Urban Planning.” Climate and Development 10 (2): 116–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2017.1301868.

- Bevan, M. T. 2014. “A Method of Phenomenological Interviewing.” Qualitative Health Research 24 (1): 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732313519710.

- Bruhns, H. 2020. “Die Stadt. Eine soziologische Untersuchung (1913/14; 1921).” In Max Weber-Handbuch: Leben – Werk – Wirkung, edited by H.-P. Müller and S. Sigmund, 363–370. J.B. Metzler. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-476-05142-4_78.

- Darmayanti, T. E., and A. Bahauddin. 2020. “Understanding Vernacularity Through Spatial Experience in the Peranakan House Kidang Mas, Chinatown, Lasem, Indonesia.” ISVS E-Journal 7 (3): 1–13.

- Döringer, S. 2021. “‘The Problem-Centred Expert interview’. Combining Qualitative Interviewing Approaches for Investigating Implicit Expert Knowledge.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 24 (3): 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2020.1766777.

- Eggan, T. A. 2018. “Landscape Metaphysics: Narrative Architecture and the Focalisation of the Environment.” English Studies 99 (4): 398–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013838X.2018.1475594.

- Ernstberger, M. D. C., and S. Adaawen. 2023. “A Transnational Family Story: A Narrative Inquiry on the Emotional and Intergenerational Notions of ‘Home’.” Emotion, Space and Society 48:100967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2023.100967.

- Franzosi, R. 1998. “Narrative Analysis—Or Why (And How) Sociologists Should Be Interested in Narrative.” Annual Review of Sociology 24 (1): 517–554. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.517.

- Gokce, D., and F. Chen. 2018. “Sense of Place in the Changing Process of House Form: Case Studies from Ankara, Turkey.” Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 45 (4): 772–796. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265813516686970.

- Guo, X., and W. Dou. 2022. “Analysis and Think About Residential Culture and Community Planning of ‘Courtyard Space’.” Architecture & Culture 8:189–191. https://doi.org/10.19875/j.cnki.jzywh.2022.08.064.

- Han, J.-H. 2015. “Transformation of the Urban Tissue and Courtyard of Residential Architecture: With a Focus on the Discourses and Plans of Paris in the 20th Century.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 14 (2): 435–442. https://doi.org/10.3130/jaabe.14.435.

- Hatipoğlu, H. K., and S. Mohammad. 2021. “Courtyard in Contemporary Multi-Unit Housing: Residential Quality with Sustainability and Sense of Community.” Günümüz Çok Katlı Konut Alanlarında Avlu: Sürdürülebilirlik ve Güçlü Topluluk Hissi Ile Oluşturulan Kaliteli Yaşam Alanları 12 (33): 802–826. Academic Search Index. https://doi.org/10.31198/idealkent.972718.

- Jacobs, J. 1992. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Vintage Books ed. New York, USA: Vintage Books .

- Kamelnia, H., P. Hanachi, and M. Moayedi. 2022. “Exploring the Spatial Structure of Toon Historical Town Courtyard Houses: Topological Characteristics of the Courtyard Based on a Configuration Approach.” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-03-2022-0051.

- Kemple, T. M. 2007. “Introduction — Allosociality: Bridges and Doors to Simmel’s Social Theory of the Limit.” Theory, Culture & Society 24 (7–8): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276407084463.

- Knapp, R. G., and K.-Y. Lo, Eds. 2005. House Home Family: Living and Being Chinese. First Edition; 2nd Printing ed. Honolulu, Hawaii, USA: University of Hawaii Press .

- Lefebvre, H. 1992. The Production of Space. translated by D. Nicholson-Smith. 1st ed. Malden, USA: Wiley-Blackwell .

- Liang, C., L. Yu, and X. Liu 2021. “Parametric Study on the Comfort of Outdoor Wind Environment of Traditional Dwelling—–taking Lius’ Courtyard in Kaifeng as an Example.” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 768. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/768/1/012152

- Lukman, A. L., and S. Sahid. 2021. “How Well Can Architecture Students Comprehend the Site as Design Context without Performing On-Site Observation?” International Journal of Built Environment and Scientific Research 5 (2): 63. Article 2. https://doi.org/10.24853/ijbesr.5.2.63-74.

- Ma, S., Z. Li, L. Li, and M. Yuan. 2022. “Coupling Coordination Degree Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Driving Factors Between New Urbanization and Construction Industry: Evidence from China.” Engineering, Construction & Architectural Management 30 (10): ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/ECAM-05-2022-0471.

- Martek, I., M. R. Hosseini, A. Shrestha, E. K. Zavadskas, and S. Seaton. 2018. “The Sustainability Narrative in Contemporary Architecture: Falling Short of Building a Sustainable Future.” Sustainability 10 (4): 981. Article 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10040981.

- Mazinanian, B., J. Sabernejad, M. Dolati, and N. Nikghadam. 2022. “The Influence of Culture in the Body of Traditional Courtyards of Hamedan Based on Data Theory.” Space Ontology International Journal 11 (1): 33–43. https://doi.org/10.52547/hafthesar.11.41.8. Directory of Open Access Journals.

- Moen, T. 2006. “Reflections on the Narrative Research Approach.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (4): 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500405.

- Mo, W., H. Yan, and H. Deng. 2022. “Discussion on the Design Strategy of Residential Courtyard from the Perspective of Rural Aesthetics.” Hunan Packaging 37 (1): 143–145. https://doi.org/10.19686/j.cnki.issn1671-4997.2022.01.036.

- Pavlenko, A. 2008. “Narrative Analysis.” In The Blackwell Guide to Research Methods in Bilingualism and Multilingualism, 311–325. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444301120.ch18.

- Pils, E. 2014. “Contending Conceptions of Ownership in Urbanizing China.” In Resolving Land Disputes in East Asia, edited by H. Fu and J. Gillespie, 1st ed., 115–172. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107589193.008

- Porotto, A. 2016. “Utopia and Vision. Learning from Vienna and Frankfurt.” Joelho Revista de Cultura Arquitectonica 7 (7): 84–103. https://doi.org/10.14195/1647-8681_7_7.

- Psarra, S., and T. Grajewski. 2000. “Architecture, Narrative and Promenade in Benson + Forsyth’s Museum of Scotland.” ARQ: Architectural Research Quarterly 4 (2): 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1359135500002578.

- Ren, Y., and K. Zhang. 2022. “Spatial Reconstruction of Hutong Courtyards in Beijing Based on Cultural Heritage.” World Scientific Research Journal 8 (8): 259–264. https://doi.org/10.6911/WSRJ.202208_8(8).0036.

- Rong, W., and A. Bahauddin. 2023a. “The Heritage and Narrative of Confucian Courtyard and Architecture in Sustainable Development in Shandong, China.” Planning Malaysia 21:21. https://doi.org/10.21837/pm.v21i26.1273.

- Rong, W., and A. Bahauddin. 2023b. “Hutongs and Vernacular Courtyard Houses Under the Influence of Confucianism: Identity and Values in Linqing, China.” ISVS E-Journal 10 (4): 38–55. Scopus.

- Sqour, S. M. 2018. “Attaining Human Aspects to Avoid Alienation in Architecture.” Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture 12 (2). https://doi.org/10.17265/1934-7359/2018.02.006.

- Tceluiko, D. S. 2019. “Influence of Shamanism, Taoism, Buddhism and Confucianism on Development of Traditional Chinese Gardens.” IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 687 (5): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/687/5/055041.

- Tuan, Y.-F. 2001. Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. Reprint ed. Minneapolis, USA: University of Minnesota Press.

- Vytniorgu, R., F. Cooper, C. Jones, and M. Barreto. 2023. “Loneliness and Belonging in Narrative Environments.” Emotion, Space and Society 46:100938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2023.100938.

- Wang, M., Z. Luo, R. Jiang, and M. Zhao. 2023. “Heritage Space, Multiple Temporalities, and the Reproduction of Guangzhou Overseas Chinese Village.” Emotion, Space and Society 48:100958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2023.100958.

- Xu, G., L. Zhong, F. Wu, Y. Zhang, and Z. Zhang. 2022. “Impacts of Micro-Scale Built Environment Features on Tourists’ Walking Behaviors in Historic Streets: Insights from Wudaoying Hutong, China.” Buildings 12 (12): 2248. Article 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12122248.

- Yang, Q. 2016. “Transformation of Living Space in Hutongs Through the Process of Urban Development.” Cambridge Journal of China Studies 11 (1): 68–87. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.4522.

- Yu, C. 2021. “The Cultural Significance of Construction and International Communication Reflection of San Kong in Qufu, Confucius’ Hometown.” Journal of Social Science and Humanities 4 (1): 6–11. https://doi.org/10.26666/rmp.jssh.2021.1.2.

- Zhang, D., and E. Zhang. 2021. “Nanchizi New Courtyard Housing in Beijing: Residents’ Perceptions and Experiences of the Redevelopment.” Journal of Chinese Architecture and Urbanism 2 (2): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.36922/jcau.v2i2.1021.

- Zhang, B., and J. Zhou. 2014. “Urbanisation, Urban Planning and Paradigms: New Theories, China’s Practices and Discussion.” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Urban Design and Planning 167 (6): 264–271. https://doi.org/10.1680/udap.14.00016.