?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The study focus was the influx of youth as an effect of the new town development policy through relocation of public institutions. We also examined differences according to location type (large and medium/small cities). In addition, we classified the effects of the influx of youth into the Seoul Metropolitan Area (SMA), non-Seoul Metropolitan Area (non-SMA), the surrounding area (SA), and non-surrounding area (non-SA). We conducted the analysis using the propensity score matching and difference-in-differences (PSM-DID) model. Study findings indicated that the new town development policy through relocation of public institutions had a positive effect, fostering an influx of youth. However, the effects of the influx of youth differed by location type (i.e. large and medium/small cities). Specifically, the effects of the influx of youth from the SMA were positive for both location types, but the effects from the non-SMA were statistically significant only for medium/small cities. In addition, we found positive effects on the youth influx from both the SA and non-SA regions in medium/small cities. This study can help policymakers and planners consider location types when developing strategies to activate a youth influx through the relocation of public institutions.

1. Introduction

Some European countries have been implementing policies for relocating public institutions with an aim to alleviate regional disparities, such as income and quality of life differences between metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas, and promote economic growth in local cities (Faggio Citation2019; Marshall et al. Citation2005). Such relocations provide numerous benefits to local communities by redistributing resources (e.g., jobs and public services) in overcrowded areas (Kang, Lee, and Kim Citation2023). In South Korea, the government’s public institution relocation policy aims to promote economic growth in local cities by creating 10 Innovation Cities (hereafter, “public institution relocation cities”). These cities are especially closely linked to regional strategic industries and are equipped with high-quality living environments to facilitate the settlement of relocated workers (Kim Citation2006; MOLIT Citation2016).

These efforts are helping to revitalize the economic vitality of local cities and, in conjunction with the recent transition to a knowledge-based economy, play an important role in attracting young people and growing urban economies. With the recent shift to a knowledge-based economy, many cities have been increasingly focusing on the youth population, which is considered an important indicator of urban economic growth (Kang, Lee, and Kim Citation2023). Young people are a key demographic group that can contribute to creativity, skills, and innovation in local economies, and their mobility has important implications for social innovation, cultural activities, and local economies (Faggian, McCann, and Sheppard Citation2007, Florida Citation2002b; Sjaastad Citation1962). In particular, the influx of youth into local cities has had a positive impact on the vitality of the region in terms of the economy and culture. Planners and policymakers are endeavoring to solve problems such as population decline and deterioration of the local economy caused by the outflow of youth from local cities (Lim Citation2021).

One such effort is the relocation of public institutions, which is attracting considerable attention as a policy tool to draw the youth population to local cities. The public institutions relocation policy promotes the relocation of public institutions, related cooperative organizations, and private companies from metropolitan to non-metropolitan areas, thereby providing quality job opportunities and creating a pleasant residential environment, which greatly contributes to the influx of the youth population. International studies have analyzed the economic effects of relocating public institutions in terms of job creation, public expenditure, public services, housing, and employment demand (Faggio Citation2019; Jefferson and Trainor Citation1996; Marshall et al. Citation2005), while domestic studies have evaluated the effects of this policy on various aspects such as population, employment, economy, and industry. However, despite the importance of the youth influx for the survival and growth of local cities, research focusing on this demographic in relation to the effects of public institution relocation policies is lacking. Another limitation is the lack of empirical research analyzing the effects of the youth influx based on the location type (i.e., large and medium/small cities where public institution relocation cities have been constructed).

Therefore, the study aim was to empirically analyze the effects of the new town development policy through relocation of public institutions, focusing on the effects of a youth population influx. Specifically, First, we examined differences in the effects of the influx of youth by location type (i.e., large and medium-to-small cities). Second, we examined differences in the effects of youth influx between the Seoul Metropolitan Area (hereafter, “SMA”) and non-Seoul Metropolitan Area (hereafter, “non-SMA”) and between the surrounding area (hereafter, “SA”) and non-surrounding area (hereafter, “non-SA”) in order to understand the policy effects. We utilized data from 162 local governments in Korea’s non-SMA for the period 2007–2020 and analyzed policy effects using the propensity score matching and difference-in-differences (PSM-DID) model. The results of this study are expected to enrich the empirical research on the effects of public institution relocation policies. We believe that the study findings will provide valuable information for policymakers and planners in formulating appropriate policies based on the locations of public institution relocation cities.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the literature on public institutions relocation policies and youth migration. In Section 3, we provide an overview of the study area, set out the variables used in the analysis, and describe the methodology. Section 4 presents the results of our empirical analysis using the PSM-DID model. Finally, Section 5 discusses the interpretation and implications of the study results, policy implications, and limitations.

2. Literature review

2.1. Overview of Korea’s the relocation of public institutions

South Korea experienced rapid urbanization and high economic growth in the 1960s. Simultaneously, the gap in development between SMA and non-SMA areas widened (Son, Kim, and Hur Citation2018). Particularly, the SMA has faced issues such as overpopulation and rising housing prices, while non-SMA countries have struggled with population decline, aging, and economic stagnation (Kim and Kim Citation2022; Kim, Park, and Park Citation2022; Kim, Park, and Song Citation2017). In response, the Korean government implemented a policy to relocate public institutions to alleviate population concentration in the SMA and promote independent regional development (Kim, Jeong, and Kim Citation2018; MOCT Citation2005).

Examining cases in Europe, the UK transferred public sector functions concentrated in London to local cities, reducing operational costs and alleviating regional economic imbalances by attracting private enterprises and providing quality public services (Jefferson and Trainor Citation1996; Marshall et al. Citation2005, Citation2003). France has systematically dispersed key functions to local cities to curb concentration in Paris and to develop underdeveloped areas, thereby resolving the development gap between regions and strengthening the role of local governments (Jamet Citation2007; Kim Citation2005). Sweden has promoted regional development through the relocation of public institutions, creating approximately 4,000 new jobs, providing diverse opportunities for the local labor market, and increasing productivity (Grennborg Citation2017; Swedish national audit office Citation2023).

South Korea implemented a policy of forcibly relocating public institutions located in the SMA by creating 10 public institution relocation cities in local areas. This policy aimed to foster these cities as growth centers for the local economy by improving settlement conditions, creating innovation clusters, and building industry – academia – research networks (Kim Citation2022; MOLIT Citation2019). However, the government has focused primarily on dispersing public institutions into local areas, without sufficiently considering their development into regional hubs. Consequently, cities with relocated public institutions were mostly promoted as new town-type developments on the outskirts of small- and medium-sized cities. However, the government expects the public institution relocation policy to curb the quantitative expansion of the metropolitan area, provide high-quality employment opportunities in the provinces, revitalize the local economy by increasing local tax revenues and expanding local finances, and promote the relocation of private company headquarters to the provinces (Kim et al. Citation2021; Lee Citation2011; Lee et al. Citation2022).

2.2. The relationship between public institution relocation cities and the youth population

The youth population significantly influences the regional population and economy; in particular, the migration of youth can lead to imbalances in the population structure between regions (Lee Citation2023; Sorensen Citation1990). In Korea, the migration of the youth population from the non-SMA to the SMA has been a major factor in causing such regional imbalances (Lee Citation2020). In local cities, the youth population is the core human capital, and the influx of youth can strengthen the region’s economic and human capabilities (Um, Roh, and Park Citation2018). In this context, public institutional relocation policies are one of the main strategies for promoting the youth influx. Florida (Citation2002b) emphasizes that the creative class plays an important role in economic and cultural innovation. In particular, the creative class represents a significant proportion of the youth population, many of whom are employed in highly educated professions such as public institutions (Lee Citation2011). From this perspective, the relocation of public institutions can be an important tool to strengthen local creative and professional capacities beyond mere population movement and can positively impact the economic and social fabric of local cities through the influx of the creative class. This influx of young people is considered an important factor in preventing regional depopulation and economic stagnation, and contributing to regional vitality; however, there is a relative lack of research on this topic. Therefore, this study focuses on the influx of youth as an effect of the new town development policy through the relocation of public institutions.

Existing studies have shown that public institution relocation policies have positive effects on various aspects such as alleviating population density in metropolitan areas, increasing population influx into local cities, promoting economic development in underdeveloped regions, and improving living environments. These policy effects can be classified as either direct or indirect. The direct effect is to promote the economic base and population inflow of the region by creating a settlement environment for related workers, along with the relocation of public institutions. In particular, the youth population in creative classes or professionals play an important role in this process. Relocating public institutions has the effect of settling creative professionals and creating an economic base that promotes local economic revitalization and demographic balance. For example, when public institutions located in metropolitan areas relocate to local cities, the influx of the youth and creative classes positively affects the local economy by creating new jobs and revitalizing consumption (Florida Citation2002b; Chang Citation2022; Kim Citation2022; Lim and Cho Citation2022; Park and Kim Citation2018; Son and Hur Citation2018). Second, indirect effects are additional activities that arise from the direct effects of relocating public institutions, such as the settlement and concentration of the creative class, attraction of related private firms, creation of youth employment, linkages between public institutions and regional strategic industries, support services, and policies, such as the expansion of public services, improved settlement conditions, and increased income (Faggio Citation2019; Faggio and Overman Citation2014; Grennborg Citation2017).

Previous research has indicated that public institution relocation has increased the influx of youth along with population growth in a region (Lim Citation2021), having a direct effect on reducing the migration of the youth population from the non-SMA to the SMA (Park and Cho Citation2017). In addition, public institution relocation has had an indirect effect on establishing quality infrastructures in such areas as education, culture, welfare, and healthcare, contributing to an increased influx of youth from the non-SMA to public institution relocation cities with environments and public services that foster their settlement therein (Kim Citation2022, Citation2021; Lim Citation2023). These research findings demonstrate that the policy of relocating public institutions has had a significant impact on the youth influx in both metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas. However, empirical research on this topic is lacking. Therefore, this study aimed to analyze the influx of the youth population, distinguishing between influx in the SMA and non-SMA.

Previous research has shown that the development of a new town through public institution relocation results in a greater population influx from the SA than from the non-SA (Kim et al. Citation2021; Yoon, Jeong, and Song Citation2017). This situation is related to the characteristics of population migration and interactions between cities. Populations tend to move to areas with high concentrations of economic activity and people, as these areas typically offer better infrastructures and more jobs (Xia et al. Citation2022. Therefore, the SA of relocated public institutions experiences population migration to the relocated city, which has a favorable urban environment and infrastructure due to the relocation of public institutions. The effect of this interaction between cities can be amplified by closer the distance between them (Heffner Citation2010; Kudełko and Musiał-Malago Citation2022; Kudłacz and Markowski Citation2017). In other words, the youth influx through public institution relocation may also affect the SA that is close to the relocation area. In this study, we divide the influx of youth from non-SMA into the SA and non-SA to examine the policy effects.

The effects of the public institution relocation policy exhibit different characteristics depending on the size of the city, whether large or medium/small (Jeon and Han Citation2020; Jeon and Lee Citation2021; Kim, Yim, and Hong Citation2022; Ko, Lee, and Koo Citation2023; Zhao, Wang, and Dong Citation2023). The relocation of public institutions has positively affected regional fiscal strength and employment outcomes, with these effects varying according to city size (Jeon and Han Citation2020; Kim, Yim, and Hong Citation2022). Specifically, such direct effects as population growth, economic growth, and infrastructure construction resulting from the relocation of public institutions can occur regardless of city size. However, the indirect effects differed between large and medium/small cities. Policy effects can be more sensitive in terms of indirect effects, such as business attraction and job creation, because medium/small cities lack the conditions to support the various uses required for relocating public institutions compared to large cities (Jeon and Lee Citation2021; Ko, Lee, and Koo Citation2023). Therefore, noting that previous research has shown that relocation effects vary by city size, we compared the effects of the influx of youth by location type (large vs. medium/small cities).

2.3. Review of various factors influencing youth migration

In previous research, youth migration has been linked to government policies and the diverse environment of a region. Based on a thorough review of previous research, the factors influencing youth migration can be attributed to job environment, local finances, cultural facilities, social welfare, medical services, and educational, natural, and urban environments. The specifications are as follows.

First, the factors that positively influence youth migration include industrial structure, job opportunities, per capita local tax, and financial independence, which pertain to the regional job environment and financial conditions. Young people in their 20s and 30s are sensitive to employment and job seeking and are more likely to migrate to regions with a favorable job environment, as indicated by the number of businesses, workers, wages, and employment rates (Argent and Walmsley Citation2008; Kim Citation2021; Lee and Lee Citation2016; Tucker et al. Citation2013). Furthermore, young people tend to move to regions with greater opportunities for high-quality employment (Lee and Moon Citation2016). The size of the job market and high probability of employment are critical factors influencing their migration (Argent and Walmsley Citation2008; Kim and Kang Citation2020; Tucker et al. Citation2013). In particular, the number of workers serves as an indicator of a region’s employment opportunities and economic activity (Park and Kim Citation2010). In addition, the per capita local tax and financial independence of local cities positively influence the migration of young people, revealing that regional economic revitalization is a necessary factor for their settlement and influx. Financial independence, which represents the proportion of the budget that local autonomous entities can use independently without interference from the central government, has been emphasized in previous research as a factor that enables the implementation of diverse policies targeting the youth population (Lim Citation2019).

Second, the major factors influencing the migration of young people include public goods and amenities that are provided based on location, such as housing, culture, medicine, welfare, and education. Previous research has shown that regions with greater benefits from public goods and services, such as accessibility to cultural facilities, enhanced educational opportunities, and rising housing prices, tend to have a higher net influx of youth (Kim Citation2021). A favorable medical and welfare environment has been identified as a factor that mitigates the outflow of youth (Kim and Chung Citation2013; Lee Citation2018). On the other hand, one of the reasons young people move for higher education is that the local labor market is not sufficiently large to absorb them within the region (Hugo Citation2001). Therefore, highly educated and professional young people are more likely to move between regions, regardless of the period (Kang Citation2019; Kim Citation2023). Differences in regional educational conditions are important factors in their migration (Kim Citation2019). In this study, we empirically explored the effect of the new town development policy through relocation of public institutions on the influx of youth by considering factors consistently addressed in previous research, such as job environment, local finance, cultural facilities, social welfare, medical services, and educational environment.

Third, environmental factors, such as natural and urban environments, which are closely related to youth quality of life, also influence youth migration. Young people prefer to live in areas with excellent natural environments such as clean air, access to green spaces, and beautiful natural landscapes (Kondo et al. Citation2018). Natural spaces, such as parks and rivers, are attractive to young people, and these environmental attributes contribute to a higher quality of life and a stronger intention to stay (Glaeser and Kahn Citation2010; Wu Citation2014). Additionally, young people value the ease and efficiency of movement in urban areas, and well-established transportation accessibility and infrastructure can positively affect youth migration (Banister and Thurstain-Goodwin Citation2011; Cervero Citation2001). Factors such as safe urban environments, low crime rates, and social stability also play important roles in youth migration decisions (Sampson Citation2012). However, Korea has a small land area and few environmental differences between regions. Especially because the cities to which public institutions have been relocated have developed as new towns, there is little difference in comfort between the cities. Moreover, the youth population, which is the main target of this study, has limited choices in the decision to relocate to public institutions; therefore, environmental factors have less impact in Korea than in other countries. Thus, this study considers the situation in Korea and focuses on the key influencing factors of youth population migration that have been consistently addressed in previous research, such as the job environment, local finances, cultural facilities, social welfare, medical services, and educational environment.

Based on the review of previous research, the distinctiveness of this study can be summarized as follows. First, its focus was the influx of youth as an effect of the public institution relocation policy. Previous research has examined the effects of this policy from various perspectives, including demographic, economic, and settlement conditions (Faggio and Overman Citation2014; Grennborg Citation2017; Jeon and Kim Citation2021; Kim Citation2022, Citation2022; Lim Citation2023; Kim, Park, and Song Citation2017; Son and Hur Citation2018; Yoon, Jeong, and Song Citation2017). However, most of these studies have been conducted in terms of regional population growth and in-migration; empirical analyses focused on young people – the primary targets of public institution relocation – are lacking. Second, in this study, we examined differences in the effects of the influx of youth based on location type (i.e., large and medium-small cities). Previous research has pointed to differing effects of the public institution relocation policy according to location type, but these effects have primarily been analyzed from an economic perspective (Jeon and Han Citation2020; Jeon and Lee Citation2021; Kim, Yim, and Hong Citation2022; Ko, Lee, and Koo Citation2023; Zhao, Wang, and Dong Citation2023). In addition, while many studies have examined the effects of public institution relocation in terms of population, few studies have compared and analyzed policy effects by location type. Third, the aim of this study was to empirically analyze policy effects across 10 public institution relocation cities using the DID method. Previous research has primarily focused on the analyses of one or two relocated regions, and the results cannot be generalized because they were mainly analyzed before and after relocation (Chang Citation2022; Lim and Cho Citation2022; Park and Kim Citation2018; Kim and Kim Citation2021).

3. Methods

3.1. Study area

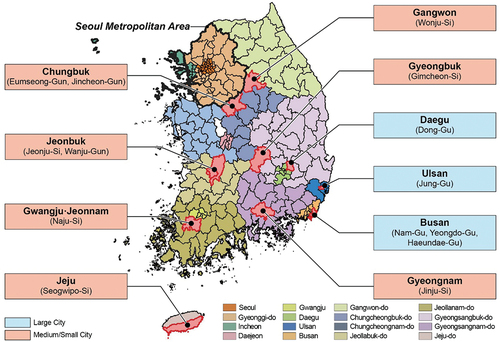

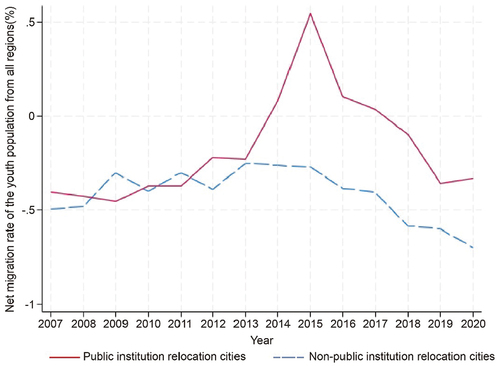

The study areas were 10 cities formed to promote the relocation of public institutions. These cities are forming new towns, with the relocation of public institutions and workers, population and service facilities, and related companies and research centers (Lee Citation2006). Cities where public institutions have relocated drive the development of underdeveloped areas, positively impacting regional development through increased local tax revenues and expanded employment opportunities for the local workforce (Lee Citation2011). As the relocation of public institutions has been in full swing, the net influx of the population from the SMA to these cities has increased, and the pace of population concentration in the SMA has slowed down (Kim et al. Citation2020; MOLIT Citation2020b). shows that the net migration rate of the youth population increased sharply from 2013, when the relocation of public institutions began in earnest, and has been decreasing since 2016. It is expected that cities that relocate public institutions will contribute significantly to preventing the youth brain drain by providing high-quality employment opportunities for youth populations in situations where the polarization of the youth population between SMA and non-SMA countries is becoming more severe (Park and Cho Citation2017; Lim Citation2021).

Figure 1. Trends in the net migration rate of the youth population in public institution relocation cities, 2007–2020.

These cities are currently evaluated as having completed the relocation and settlement of public institutions and are driven forward by promoting industry, academia, and research; supporting the formation of settlement systems; and supplementing existing policies (Jeon and Han Citation2020; Kim, Yim, and Hong Citation2022). Public institution relocation cities can be categorized into two types based on their location: large cities located in metropolitan areas and medium/small cities located in the Si and Gun regions (Yoon Citation2018). Therefore, large city location types include Busan, Daegu, and Ulsan, whereas medium/small-city location types include Gwangju-Jeonnam, Gangwon, Jeonbuk, Gyeongbuk, Gyeongnam, and Jeju (, ). The 112 public institutions located in the SMA, including public enterprises and research institutions, were classified by function and relocated to public institution relocation cities (). Consequently, the current settled population in public institution relocation cities represents 87.1% of the target. With an increase in local talent hiring rates and the number of companies settling in these cities, a significant contribution to regional employment growth has been observed (Kim Citation2022). Furthermore, the relocation of public institutions previously concentrated in the SMA to the provinces has achieved direct results in slowing the population concentration in the SMA and dispersing job opportunities (Kim Citation2022; Kim and Kang Citation2020).

Table 1. Description of public institution relocation cities.

3.2. Data resource and variable specification

The dependent variable in this study, the youth population, was defined by various national and international criteria (Appendix A). In this study, we considered youth as transitioning to adulthood, a time of new social experiences and relationships. Young people are transitioning from school to the labor market (employment) and marriage (Baltes and Carstensen Citation1999). We also regarded the youth population as those aged 20–39 years, given that we used population migration statistics for five-year age groups provided by Statistics Korea. The net migration rate of this population was calculated as the ratio of the youth population’s net influx to the total registered population of that year, considering potential bias where areas with a larger absolute number of youths might have more explanatory power (Lim Citation2021). Additionally, to analyze the effects of the youth population influx comprehensively, we set the dependent variable not only as the net migration rate of the youth population from all regions (NMR_YP_ALL) but also the net migration rates of the youth population from the SMA (NMR_YP_SMA), non-SMA (NMR_YP_non-SMA), SA (NMR_YP_SA), and non-SA (NMR_YP_non-SA). The formula for the dependent variable, the net migration rate of the youth population, is shown in Equation 1:

: Region (Si/Gun/Gu)

: SMA, non-SMA, SA, non-SA

: year

: Net migration rate of the youth population from region

to region

in year

: Resident population in region

in year

: The number of youth leaving region

and migrating to region

(inflow) in year

: The number of youth migrating from region

(outflow) to region

in year

The independent variable of this study, “treated,” was used as a dummy variable with a value of 1 for the 14 Si/Gun/Gu in which public institution relocation cities were developed (treated group); the value of 0 was used for other regions (control group) based on the status of public institution relocation cities presented by MOLIT (Citation2016). “Period” was based on the phased plan of public institution relocation cities presented by MOLIT (Citation2014), and the development period of the relocation and settlement phase (2007–2014) was used as the basis. The period after 2014 was set as the point at which the policy effects occurred.

The control variables in this study were set based on previous research that reviewed factors that could influence youth population migration (e.g., job environment, local finances, cultural facilities, welfare facilities, medical services, education services, and higher education environments). The data for these variables were compiled using statistics provided by Statistics Korea. Specifically, job environment was measured by the number of workers per 1,000 people, representing the scale of jobs and employment conditions in the region. Local finance was measured using financial independence, which is an indicator assessing the financial management ability of local governments. Cultural and welfare facilities were determined based on the number of cultural and social welfare facilities per 10,000 people, considering both region size and facility accessibility. Medical services were defined as the number of hospital beds per 1,000 people, indicating the level of medical, welfare, and service accessibility in the region. Educational services and higher education environments were determined by the number of students per teacher and number of college students per 1,000 people, which represent the quality of education and level of educational services. The descriptive statistics of the dependent, independent, and control variables are presented in .

Table 2. Variable definition and descriptive statistics.

3.3. Analytical method

We used the PSM-DID model to analyze the effects of the youth population influx attributed to new town development policy through relocation of public institutions. We used the DID method to estimate the effect of this influx through the variables of the region where public institution relocation cities were developed (treated group), those without such cities (control group), and the variables of policy implementation before and after. To use the DID method, it was necessary to set a control group similar to the treated group, which comprised regions with public institution relocation cities, to minimize the overestimation or underestimation of policy effects by addressing the issues of selection bias and endogeneity (Heckman, Ichimura, and Todd Citation1997; Hong and Park Citation2021). Therefore, we used the PSM, calculating the propensity score using the covariates of the treated group before receiving the policy benefit and then extracting the control group that was most similar to the treated group. We used the PSM-DID model, which combines the DID method with PSM, to quantitatively analyze the policy effect by resolving the issues of selection bias and endogeneity and controlling for external environmental factors (Heckman, Ichimura, and Todd Citation1997; Rosenbaum and Rubin Citation1983). The specific process for conducting the analysis using the PSM-DID model follows:

First, we conducted PSM based on 2007 data to export similar samples between regions where public institution relocation cities were developed (treated group) and regions where they were not developed (control group). To this end, we estimated the propensity score through a logistic model by setting whether the region had public institution relocation cities (variable of “treated”) as the dependent variable and introducing the influencing factors of youth population migration as covariates. Covariates included job environment, local finances, cultural facilities, welfare facilities, medical services, education environment, and higher education environment. After calculating the propensity score, we used the nearest neighbor matching method to match the control group with the treated group. Nearest neighbor matching allowed the possibility of duplicate matching to enhance the similarity between the treated and control groups (Yi Citation2021) using 1:8 matching. As a result of PSM, 14 regions in the treated group and 73 regions in the control group were extracted, with a total of 1,218 samples.

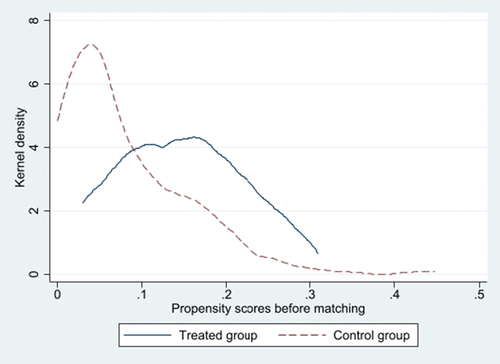

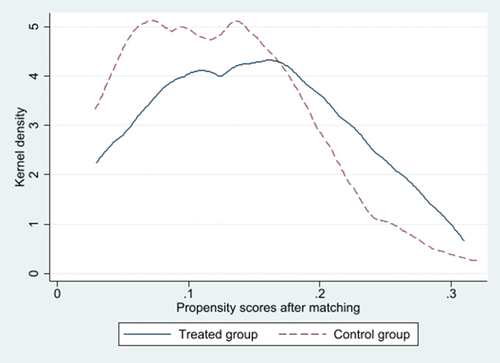

Finally, the treated and control groups derived from PSM were subjected to a balance test to confirm whether matching was properly conducted. The balance test examined the similarity in the propensity score distribution before and after matching, the t-test, and standardized bias. show the propensity score distributions for the treated and control groups before and after matching, respectively (i.e., kernel density graphs). By examining the similarity in the propensity score distribution before and after matching using these two graphs, we confirmed that the distribution of propensity scores between the two groups became similar after matching. presents the t-test results and standardized bias for the covariates before and after matching. Results of the t-test confirmed significant differences in education services and higher education environments between the treated and control groups in the samples before matching, indicating that the two groups did not satisfy homogeneity conditions. By contrast, after matching, the samples showed no statistically significant differences between groups. Standardized bias is generally considered to be adequately balanced between the treated and control groups if its absolute value is less than 20% (Rosenbaum and Rubin Citation1983). In this study, the absolute value of the standardized bias for the covariates after matching was less than 20%, confirming a balanced match between the treated and control groups. Therefore, the balance test confirmed that the treated and control groups derived from PSM were appropriately matched.

Table 3. Balance test: propensity score matching (PSM).

Second, in this study, we estimated the effect of the youth population influx using samples derived from PSM and the DID method. The estimation formula for DID is shown in Equation 2:

where represents the dependent variable, the net influx rate of the youth population in region

at time

.

is a dummy variable for regions where a public institution relocation city was developed. It takes a value of 1 for regions where such a city has been developed (treated group) and 0 for regions where one has not been developed (control group).

is a time dummy variable indicating the point at which the construction project of the public institution relocation city was completed. The most important variable in this study,

, is the interaction term resulting from multiplying

and

, representing the DID estimate. The coefficient of

can be used to determine the impact of public institution relocation on youth population influx based on its sign and statistical significance.

denotes the control variables influencing youth population migration, and

represents the error term. Due to limitations in data collection, we acknowledge the possibility of unobserved regional characteristics in the analysis process. To control for this possibility, we used a two-way fixed effects model to control for regional fixed effects (

) and added a year dummy variable (

) (Appendix C).

4. Empirical results

4.1. Baseline results

To analyze the youth population influx effect, we used the DID method and samples derived from PSM; the results are presented in . Model 1 presents the DID analysis results with NMR_YP_ALL as the dependent variable; Model 2, with NMR_YP_SMA; and Model 3, with NMR_YP_non-SMA. In Model 1, the results of the DID variable, the key variable, show that regions where a public institution relocation city was developed had a significant positive effect on NMR_YP_ALL after project completion (B = 0.517, p < 0.01). In Models 2 and 3—used to analyze the youth migration from the SMA and non-SMA, respectively—, the DID variable indicated that both NMR_YP_SMA (B = 0.136, p < 0.01) and NMR_YP_non-SMA (B = 0.381, p < 0.01) exhibited significant positive effects. Therefore, we confirmed that the new town development policy through relocation of public institutions led to an increase in the net migration rate of the youth population, having a positive effect on the youth population influx from both the SMA and non-SMA.

Table 4. Baseline results for the effects on the youth population influx from all regions, SMA and non-SMA.

4.2. Analysis of youth population influx effects by location type

The effects of the youth population influx by the location type of public institution relocation cities (i.e., large and medium/small cities) are presented in . First, regarding large cities, Model 4 shows the DID analysis results for NMR_YP_SMA. The value of the DID variable, the key variable, indicates a significant positive effect on NMR_YP_SMA (B = 0.040, p < 0.05). Model 5 shows the DID analysis results for NMR_YP_non-SMA, and the value of the DID variable shows that NMR_YP_non-SMA is not statistically significant. Thus, in large cities, the new town development policy through relocation of public institutions positively affected youth migration from the SMA but had no effect on the youth population influx from the non-SMA. These results suggest a positive direct effect of the youth population influx due to the relocation of public institutions that were situated in the SMA. However, the large city location type already possessed conditions to support the various activities necessary for the relocation of public institutions, implying that the indirect effects of supportive services and policies due to public institution relocation were not significant (Jeon and Lee Citation2021; Ko, Lee, and Koo Citation2023). Consequently, we inferred that the large city location type did not exhibit a prominent effect on the youth population influx from the non-SMA compared to the control group.

Table 5. Results regarding youth population influx effects in large and medium/small-city location types.

Regarding the medium/small-city location type, Model 6 presents the DID analysis results for NMR_YP_SMA and the DID variable, which is the key variable, and demonstrates a statistically significant positive effect on NMR_YP_SMA (B = 0.190, p < 0.01). Model 7 presents the results of the DID analysis for NMR_YP_non-SMA. The DID variable had a statistically significant effect on NMR_YP_non-SMA (B = 0.548, p < 0.01), indicating that for medium/small-city location types, the new town development policy through relocation of public institutions had a positive effect on the youth population influx from both the SMA and non-SMA. These results are comparable to the positive direct effect of the youth population influx from the SMA in large city location types because of the relocation of institutions that were situated in the SMA. In contrast to the large city location type, the medium/small-city location type lacked the necessary supportive services for public institution relocation, suggesting a noticeable indirect effect due to the direct effects of relocation. Particularly, when comparing the values of the DID variable in Models 6 and 7, this indirect effect had a significant effect on the youth population influx from the non-SMA.

In terms of the control variables in the large city location type, both job environment and education services had statistically significant effects on NMR_YP_SMA (Model 4). Conversely, welfare facilities had a statistically significant effect on NMR_YP_non-SMA (Model 5). In the medium/small-city location type, medical services had a statistically significant effect on NMR_YP_non-SMA (Model 7). Moreover, both local finances and medical services had statistically significant effects on the net influx rate of the youth population in both the large and medium/small-city location types, suggesting that a region’s favorable financial conditions and medical services are important factors in youth migration.

The results of the detailed analysis of the effects of youth population influx from the non-SMA in the medium/small-city location type are presented in . Model 8 presents the results of the DID analysis pertaining to NMR_YP_SA, whereas Model 9 delineates these results for NMR_YP_non-SA. Upon examining Models 8 and 9, the DID variable results revealed that both NMR_YP_SA (B = 0.263, p < 0.01) and NMR_YP_non-SA (B = 0.285, p < 0.01) exhibited statistically significant positive effects. These results differed from predictions made based on previous research that anticipated a more substantial effect of the youth influx from the SA. This study confirmed that the new town development policy through the relocation of public institutions had a positive effect on the influx of youth from both SA and non-SA areas.

Table 6. Effects of the influx of youth from the SA and non-SA in medium/small-city location types.

5. Discussion and conclusion

This study focused on whether the policy of new town development through the relocation of public institutions has a positive effect on the influx of youth, and it empirically analyzed the differences in this effect between large and medium/small-city location types. The study findings are as follows: First, when looking at the public institution relocation cities as a whole, the new town development policy through the relocation of public institutions showed positive effects on the influx of youth from both the SMA and non-SMA. Second, the effect of the youth population influx varies by location type. The effect of the youth influx from the SMA was positive for both large and medium/small cities, but the effect of the youth influx from the non-SMA was statistically significant only for medium/small cities. Third, we found that the effects of youth population influx in medium/small cities, from both SA and non-SA, were positive. These findings have important implications for policymakers and planners when determining policies related to the relocation of public institutions and youth population management.

First, existing studies have shown that the relocation of public institutions contributes to the dispersion of major functions in the SMA and the economic development of local cities, particularly playing a crucial role in the influx and increase in population (Faggio Citation2019; Kim and Kim Citation2021; Faggio and Overman Citation2014; Grennborg Citation2017). In addition, studies on the youth population (Lim Citation2019, Citation2023; Park and Cho Citation2017) have shown that public institution relocation policies have a positive effect on the influx of youth, along with the population growth of local cities in some public institution relocation cities, such as Chungbuk and Gyeongnam. Our analysis focused on 10 public institutions relocation cities and found positive effects on the influx of youth from SMA and non-SMAs. These results imply that Korea’s public institution relocation policy is effective not only in increasing the population, but also in dispersing the youth population to local cities, primarily because most public institution workers belong to the youth demographic. Additionally, these findings indicate that the public institution relocation policy can promote a balanced distribution of youth across regions and can be used as a strategic approach for regional development.

The influx of the youth population from the non-SMA was statistically significant in the medium/small-city location type but not in the large city location type. Previous research has shown that the economic effects of public institution relocation can vary depending on the location type (Jeon and Han Citation2020; Kim and Kim Citation2022). This study focused on the population effect, finding that the effect of youth population influx differs by location type between large and medium/small-city locations. The effect on the influx of youth from the SMA is due to the migration of people who work in public institutions, such as public enterprises and research institutions, while the effect on the influx of youth from the non-SMA is the fulfillment of the service functions that support them. As these service functions already have sufficient infrastructure in large cities but are relatively lacking in medium/small cities, this study leads to the conclusion that the effect of public institutions relocation is significant in medium/small-city locations. This can be seen in both the positive and negative aspects: negative in the sense that the relocation of public institutions did not attract young people working in service functions together, but positive in the sense that it provided new jobs for scattered young people and opportunities for choice and concentration.

The positive effects of youth population influx from both SA and non-SA regions in the medium/small-city location types, as revealed in this study, differ from previous research findings. Previous studies (Kim et al. Citation2021; Yoon, Jeong, and Song Citation2017) have shown that the creation of public institutions relocation cities has increased population influx from the SA, emphasizing the importance of distance in the interaction between cities (Heffner Citation2010; Kudełko and Musiał-Malago Citation2022; Kudłacz and Markowski Citation2017). From this perspective, a significant effect of SA on the youth population influx from SA was expected. However, this study conducted an empirical analysis of the policy effect by comparing the areas where public institutions have been relocated with a control group and found that the influx of the youth population from both SA and non-SA areas was significant. This indicates that the indirect effects of public institution relocation are balanced, resulting in a positive effect.

The policy implications of our findings are as follows: First, to continuously expand the positive effects of the youth population influx due to the relocation of public institutions, location-specific customized support services and policies are necessary. In large city location types, policies should aim to reduce housing costs for youth through residential support, provide high-quality jobs, and enhance education and cultural standards to facilitate stable settlements (Lim Citation2021; Kim, Park, and Park Citation2022; Shane Citation2003). Medium/small-city location types should promote a positive image of affordable housing and a relaxed living environment and focus on regional development policies such as jobs, education, healthcare, and welfare in conjunction with policies to address the issue of population decline (Florida Citation2002a; Park and Kim Citation2020). Second, in SA, the outflow of youth due to the relocation of public institutions can negatively affect the economic and social structure of the area (Duranton and Puga Citation2004; Kline and Moretti Citation2014), so appropriate countermeasures are required. In future urban growth phases, the influx of youth from SA is likely to continue, especially in terms of the quality of living environments provided by cities with relocated public institutions (Lee, Lee, and Park Citation2018). This concern may especially lead to conflicts with SA in medium/small-city location types. Therefore, these areas should consider institutional support to form cooperative governance with the relocated areas and provide a rational supply of urban services for mutual development (Kim et al. Citation2021; Yoon, Jeong, and Song Citation2017).

The contributions of this study are as follows: First, by focusing on the youth population and empirically identifying the effects of public institutions relocation, this study provides a new perspective to the field of urban and regional development, which has been largely neglected in the literature. This analysis has important implications for understanding the impact of large-scale government policies on the migration patterns of young people. Second, this study’s analysis of the effects of the youth population influx based on the location types of large and medium/small cities differentiates it from previous research, which has mainly addressed the impact of public institution relocation from an economic standpoint. This underscores the need for policymakers and planners to consider diverse policy approaches that are tailored to different regional characteristics.

The limitations of this study and future research directions are as follows. First, it analyzed the effectiveness of public institution relocation policies based on data from 2007 to 2020. A limitation to this study is that it does not consider the recent past. It is important to analyze the long-term effects and changes over time of large-scale policies, such as public institution relocation, and future studies should include more recent data to identify these changes. Second, this study was unable to include important job environment variables, such as wages and employment rates, because of the limitations of regional data collection. Future studies should use Statistics Korea’s Regional Employment Survey to include variables on employment rates and expected wages to further analyze the effects of public institutions relocation policies on the youth population. Such an approach will help precisely assess the policy’s effects by comprehensively considering the economic factors related to youth migration. Third, this study focused primarily on quantitative data. Future research would benefit from adding qualitative insights, such as interviews or surveys with residents and workers in cities relocating public institutions. This approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of policy impacts beyond statistical results and significantly contributes to exploring the social and cultural impacts of the policy.

Acknowledgements

For this study, we did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or nonprofit sectors. And we would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jungwoo Ko

Jungwoo Ko is a Ph.D. candidate at Hanyang University, Graduate School of Urban Studies, majoring in Urban Regeneration Design. His research interests include urban regeneration, shrinking cities, and urban and regional planning.

Joolim Lee

Joolim Lee obtained his Ph.D. from the Graduate School of Urban Studies at Hanyang University. He is currently the director at URI Urban Institute Co., Ltd., with main interests in overseas urban development, urban regeneration, and childcare environments.

Ja-Hoon Koo

Ja-Hoon Koo is a professor at the Graduate School of Urban Studies at Hanyang University, where he primarily studies and teaches urban design, urban regeneration, and urban planning.

References

- African Union Commission. 2006. ‘African Youth Charter.’ https://scholar.google.co.kr/scholar?hl=ko&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=African+Union+Commission.+2006.+%E2%80%9CAfrican+Youth+Charter.%E2%80%9D&btnG=.

- Argent, N., and J. I. M. Walmsley. 2008. “Rural Youth Migration Trends in Australia: An Overview of Recent Trends and Two Inland Case Studies.” Geographical Research 46 (2): 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-5871.2008.00505.x.

- Baltes, M. M., and L. L. Carstensen. 1999. “Social-Psychological Theories and Their Applications to Aging: From Individual to Collective.” Handbook of Theories of Aging 1:209–226.

- Banister, D., and M. Thurstain-Goodwin. 2011. “Quantification of the Non-Transport Benefits Resulting from Rail Investment.” Journal of Transport Geography 19 (2): 212–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2010.05.001.

- Brown, H. C. P. 2021. “Youth, Migration and Community Forestry in the Global South.” Forests, Trees and Livelihoods 30 (3): 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/14728028.2021.1958065.

- Cervero, R. 2001. “Efficient Urbanisation: Economic Performance and the Shape of the Metropolis.” Urban Studies 38 (10): 1651–1671. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980120084804.

- Chang, I. S. 2022. “An Effect of Innovation City Policy on Population Regrowth in Depopulation Area: Focusing on Gwangju Jeonnam Innovation City in Korea.” Regional Policy Review 33 (2): 21–38.

- Choi, T. L., J. H. Kim, and M. S. Choi. 2022. “The Effects of Smart Factory System on Sales and Employment: Evidence from Manufacturing SMEs in Incheon.” Journal of Korea Planning Association 57 (6): 74–87. https://doi.org/10.17208/jkpa.2022.11.57.6.74.

- Clendenning, J. 2019. Approaching Rural Young People. Vol. 1. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR.

- Duranton, G., and D. Puga. 2004. “Micro-Foundations of Urban Agglomeration Economies.” In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, 2063–2117. Vol. 4. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0080(04)80005-1.

- Faggian, A., P. McCann, and S. Sheppard. 2007. “Some Evidence That Women are More Mobile Than Men: Gender Differences in UK Graduate Migration Behavior.” Journal of Regional Science 47 (3): 517–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.2007.00518.x.

- Faggio, G. 2019. “Relocation of Public Sector Workers: Evaluating a Place-Based Policy.” Journal of Urban Economics 111:53–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2019.03.001.

- Faggio, G., and H. Overman. 2014. “The Effect of Public Employment on Local Labor Markets.” Journal of Urban Economics 79:91–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2013.05.002.

- Florida, R. 2002a. “The Economic Geography of Talent.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 92 (4): 743–755. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8306.00314.

- Florida, R. 2002b. The Rise of the Creative Class. Vol. 9. New York: Basic Books.

- Glaeser, E. L., and M. E. Kahn. 2010. “The Greenness of Cities: Carbon Dioxide Emissions and Urban Development.” Journal of Urban Economics 67 (3): 404–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2009.11.006.

- Grennborg, A. 2017. “State Sector Relocations in Sweden.” Department of Geography and Economic History, Umea University.

- Heckman, J., H. Ichimura, and P. E. Todd. 1997. “Matching as an Econometric Evaluation Estimator: Evidence from Evaluating a Job Training Programme.” The Review of Economic Studies 64 (4): 605–654. https://doi.org/10.2307/2971733.

- Heffner, K. 2010. “Regiony Międzymetropolitalne a Efekty Polityki Spójności w Polsce.” Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu 95:163–184.

- Hong, Z., and I. K. Park. 2021. “The Effects of the Revised Housing Allowance System on Housing Cost Burden of Rented Households: An Analysis Using Propensity Score Matching Techniques Combined with a Dynamic Panel Data Model.” Journal of Korea Planning Association 56 (2): 22–36. https://doi.org/10.17208/jkpa.2021.04.56.2.22.

- Hugo, G. 2001. “What is Really Happening in Rural and Regional Populations.” The Future of Australia’s Country Towns 57–71. http://www.regional.org.au/au/countrytowns/keynote/hugo.html.

- Jamet, S. 2007. “Meeting the Challenges of Decentralisation in France.” OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 571.

- Jefferson, C. W., and M. Trainor. 1996. “Public Sector Relocation and Regional Development.” Urban Studies 33 (1): 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420989650012103.

- Jeon, J. S. 2019. A Survey on the Human Rights Situation of Poor Youth. Seoul: National Human Rights Commission of Korea.

- Jeon, M. S., and S. H. Han. 2020. “A Study on Regional Employment Performance of Innovation City Policy.” The Journal of Convergence Society and Public Policy 14 (3): 70–102. https://doi.org/10.37582/CSPP.2020.14.3.70.

- Jeon, M. S., and J. S. Kim. 2021. “Analysis of Population Migration Effects of Innovation City Policy: Using the Synthetic Control Method.” The Korea Association for Policy Studies 30 (4): 65–98. https://doi.org/10.33900/KAPS.2021.30.4.3.

- Jeon, M. S., and J. S. Lee. 2021. “Is Public Agency Relocation Effective to Achieve Decentralization? Evaluating Its Effects on Regional Employment.” Journal of Urban Affairs 45 (8): 1486–1501. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2021.1962722.

- Kang, D. W. 2019. “Characteristics of Youth Regional Migration and the Impact of Regional Characteristics.” Monthly Labor Review February 2019 :47–60.

- Kang, S. H., J. S. Lee, and S. Kim. 2023. “Has South Korea’s Policy of Relocating Public Institutions Been Successful? A Case Study of 12 Agglomeration Areas Under the Innovation City Policy.” Urban Studies. 00420980231193567. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980231193567.

- Kim, C. G. 2006. “Construction Background and Direction of Innovation City.” Planning, and Policy 297:6–16.

- Kim, D. S. 2021. “A Study on Economic and Socio-Cultural Factors Affecting the Migration of Youths in Local Areas: Focusing on the Case of Daegu Metropolitan City.” The Journal of Policy Development 21 (2): 177–205.

- Kim, H. W. 2023. “An Empirical Analysis of Changes in Occupational Values in Regional Migration of the Young Population.” The Korea Local Administration Review 37 (1): 319–342. https://doi.org/10.22783/krila.2023.34.1.319.

- Kim, J. H. 2022. “Performance and Future Challenges of Innovation City.” I-KIET Industrial Economic Issues 144:1–12.

- Kim, J. S. 2022. “A Study on the Economic Impact of Public Sector Relocation and Innovative City Development.” Korean Journal of Local Government Studies 26 (2): 119–145. https://doi.org/10.20484/klog.26.2.6.

- Kim, T. H. 2005. “Public Sector Relocation and Balanced Regional Development: A Case of French Experience.” Journal of the Korean Association of Regional Geographers 11 (1): 71–82.

- Kim, Y. H. 2021. “The Effects of Regional Economic and Living Conditions on Youth Population Migration.” Korean Public Administration Review 55 (2): 337–367. https://doi.org/10.18333/KPAR.55.2.337.

- Kim, E. R., M. S. Cha, Y. M. Seo, J. E. Song, H. S. Sin, H. R. Lee, and S. R. Ko. 2021. “A Study on Win-Win Development Strategies Between Innovation Cities and Linked Area.” Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements, Korea.

- Kim, G. S., and M. S. Chung. 2013. “The Determinants of the Out-Migration of Human Capital in Busan Metropolitan Area in Korea.” Journal of Economics Studies 31 (2): 103–130.

- Kim, J. H., D. Y. Jeong, and M. C. Kim. 2018. Local Settlement Status of Public Institutions Relocated to Local Areas and Future Improvement Tasks. Seoul: National Assembly Research Service.

- Kim, H. W., and M. G. Kang. 2020. “Characteristics of Population Migration Among Millennials According to Their Preference for Self-Determination in Life.” Journal of the Korean Regional Development Association 32 (5): 49–78.

- Kim, W. Y., and M. K. Kim. 2021. “The Effects of Public Sector Relocation on Population and Employment: The Case of Jinju City.” Journal of the Korean Association of Regional Geographers 27 (2): 144–163. https://doi.org/10.26863/JKARG.2021.5.27.2.144.

- Kim, Y. H., and S. U. Kim. 2022. “The Effects of the Relocation of Public Institutions on the Employment of Local Talent.” Korean Public Administration Review 56 (2): 247–274. https://doi.org/10.18333/KPAR.56.2.247.

- Kim, T. H., S. H. Min, E. R. Kim, and Y. M. Seo. 2020. “Performance Evaluation and Future Development Strategies for 15 Years of Innovation City.” KRIHS Policy Brief 775:1–8.

- Kim, H. J., C. I. Park, and K. A. Park. 2022. “A Correlation Study on Migration Patterns and Urban Settlement Environment of Innovation Cities.” Journal of the Korean Regional Development Association 34 (1): 27–48.

- Kim, M. G., J. H. Park, and Y. C. Song. 2017. “Balanced Development Theory: Does the Relocation of Government-Owned Companies Matter to Regional Economic Growth?” Public Policy Review 31 (4): 335–366. https://doi.org/10.17327/ippa.2017.31.4.012.

- Kim, Y. J., J. B. Yim, and G. S. Hong. 2022. “The Effect of Innovative City on Local Taxes.” Korean Policy Sciences Review 26 (2): 119–138. https://doi.org/10.31553/kpsr.2022.6.26.2.119.

- Kline, P., and E. Moretti. 2014. “People, Places, and Public Policy: Some Simple Welfare Economics of Local Economic Development Programs.” Annual Review of Economics 6 (1): 629–662. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080213-041024.

- Ko, J. W., J. L. Lee, and J. H. Koo. 2023. “A Study on the Improvement: Local Investment Support Schemes for Local Industry Development and Activation.” Journal of the Korean Regional Development Association 35 (2): 45–68.

- Kondo, M. C., J. M. Fluehr, T. McKeon, and C. C. Branas. 2018. “Urban Green Space and Its Impact on Human Health.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (3): 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15030445.

- Kudełko, J., and M. Musiał-Malago. 2022. “The Diversity of Demographic Potential and Socioeconomic Development of Urban Functional Areas–Evidence from Poland.” Cities 123:103516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103516.

- Kudłacz, T., and T. Markowski. 2017. “Miejskie Obszary Funkcjonalne w Świetle Wybranych Koncepcji Teoretycznych–zarys Problemu.” Studia Komitetu Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania Kraju PAN 174:17–30.

- Lee, B. Y. 2011. “Innovation City and Competitiveness of Region and Nation.” Journal of the Economic Geographical Society of Korea 14 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.23841/egsk.2011.14.1.1.

- Lee, C. Y. 2018. “An Analysis on the Determinants of Population Migration by Age.” Review of Business & Economics 31 (2): 707–729. https://doi.org/10.22558/jieb.2018.04.31.2.707.

- Lee, D. W. 2023. “A Study on the Population Structure and Population Movement of the Young Generation in Local Areas: Focusing on Gangwon-Do.” Journal of Local Government Studis 35 (1): 29–56. https://doi.org/10.21026/jlgs.2023.35.1.29.

- Lee, J. R. 2006. “National and Regional Development Effects of Innovation City Construction.” Planning, and Policy 297:39–48. https://scholar.google.co.kr/scholar?hl=ko&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%ED%98%81%EC%8B%A0%EB%8F%84%EC%8B%9C+%EA%B1%B4%EC%84%A4%EC%9D%98+%EA%B5%AD%EA%B0%80+%EB%B0%8F+%EC%A7%80%EC%97%AD%EB%B0%9C%EC%A0%84+%ED%8C%8C%EA%B8%89%ED%9A%A8%EA%B3%BC&btnG=.

- Lee, S. L. 2020. “Concentration of the Seoul Metropolitan Area and the Local Population Crisis Due to Youth Population Migration.” Health and Welfare ISSUE & FOCUS 395:1–9. https://scholar.google.co.kr/scholar?hl=ko&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%EC%B2%AD%EB%85%84%EC%9D%B8%EA%B5%AC+%EC%9D%B4%EB%8F%99%EC%97%90+%EB%94%B0%EB%A5%B8+%EC%88%98%EB%8F%84%EA%B6%8C+%EC%A7%91%EC%A4%91%EA%B3%BC+%EC%A7%80%EB%B0%A9+%EC%9D%B8%EA%B5%AC+%EC%9C%84%EA%B8%B0&btnG=.

- Lee, J. H., S. M. Hyeon, M. L. Park, J. H. Lee, and D. S. Seo. 2022. “Identifying Regional Centrality of Seoul Metropolitan Area in the Context of Relocating Public Agencies to Regional Areas.” Journal of Korea Planning Association 57 (3): 52–67. https://doi.org/10.17208/jkpa.2022.06.57.3.52.

- Lee, C. Y., and H. H. Lee. 2016. “An Analysis on the Determinants of Youth Population Movement Across Regions and Prospects.” Journal of Economics Studies 34 (4): 143–169.

- Lee, H. J., S. G. Lee, and S. J. Park. 2018. “The Impact of Sejong City on the Population Migration in the Adjacent Municipalities and the Capital Region: Focused on the Shift-Share Analysis Using the 2006-2016 Population Migration Data.” Journal of Korea Planning Association 53 (2): 85–105. https://doi.org/10.17208/jkpa.2018.04.53.2.85.

- Lee, C. Y., and J. C. Moon. 2016. “An Analysis on the Determinants of Population Migration in Gwangju and Jeonnam by Age and Movement Area.” Journal of Industrial Economics & Business 29 (6): 2239–2266. https://doi.org/10.22558/jieb.2016.12.29.6.2239.

- Lim, T. K. 2019. “The Impact of Innovative City Governed by Federal Government on Regional Economic Growth in South Korea: Focused on Quasi-Experimental Design.” The Korea Local Administration Review 33 (3): 233–260.

- Lim, T. K. 2021. “Impact of Young Adult Population Influx on the Policy of Innovative City: Focused on the Case of Chungbuk Province.” The Korea Local Administration Review 35 (4): 247–274.

- Lim, T. K. 2023. “The Effects of Innovation City Policy on Youth Migration.” Korean Journal of Local Government Studies 26 (4): 235–259. https://doi.org/10.20484/klog.26.4.10.

- Lim, Y. J. 2020. “Youth Discourse of International Organizations and Youth Policies in Korea.” Culture & Politics 7 (4): 91–121.

- Lim, Y. J., and Y. T. Cho. 2022. “A Demographic Analysis of Innovation City Project: With a Focus on Naju Innovation City.” Korea Journal of Population Studies 45 (2): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.31693/KJPS.2022.03.45.2.1.

- Marshall, J. N., D. Bradley, C. Hodgson, N. Alderman, and R. Richardson. 2005. “Relocation, Relocation, Relocation: Assessing the Case for Public Sector Dispersal.” Regional Studies 39 (6): 767–787. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400500213663.

- Marshall, N., D. P. Bradley, C. M. Hodgson, R. G. W. Richardson, N. F. Alderman, P. Benneworth, G. Tebbutt, et al. 2003. Public Sector Relocation from London and the South East. Final report to the English Regional Development Agencies as a contribution to the Lyons Review.

- MOCT with 25 institutions. 2005. “Plan for the Relocation of Public Institutions.” Ministry of Construction and Transportation, Korea.

- MOLIT. 2014. “A Study on the Development of Evaluation System for the Establishment Project of Industry-Academic Cluster in Innovation City.” Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, Korea.

- MOLIT. 2016. “General White Paper on Public Institutions Relocating to Local Cities and Innovation City Construction (2003–2015).” Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, Korea.

- MOLIT. 2019. “A Study on the Comprehensive Development Plan for Innovation Cities.” Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, Korea.

- MOLIT. 2020a. “Current Status of Project Implementation by Innovation Cities.” Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, Korea.

- MOLIT. 2020b. “Performance Evaluation and Policy Support for Innovative Cities.” Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, Korea.

- Park, M. K., and M. H. Cho. 2017. “The Impact of Public Institutions Relocating to Local City Policy on Youth Migration.” In Labor Panel Conference 2017, Seoul National University.

- Park, B. H., and J. Y. Kim. 2010. “A Study on the Dynamic Decline Types of Local Cities Using Multiple Decline Index.” Journal of the Korean Regional Science Association 26 (2): 3–17.

- Park, J. I., and J. H. Kim. 2018. “A Study on the Change of Population Distribution in Metropolitan Area by the Development of the New Town-Type Innovation City: A Case Study of the Daegu Innovation City in South Korea.” Journal of the Korean Regional Science Association 34 (3): 55–68. https://doi.org/10.22669/krsa.2018.34.3.055.

- Park, J. K., and D. H. Kim. 2020. Research on Promoting Young Influx and Settlement Support Policies in Response to Population Decline. Wonju: Korea Research Institute for Local Administration.

- Rosenbaum, P. R., and D. B. Rubin. 1983. “The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects.” Biomerika 70 (1): 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/70.1.41.

- Sampson, R. J. 2012. Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect. Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press.

- Shane, S. A. 2003. A General Theory of Entrepreneurship: The Individual-Opportunity Nexus. Norfolk, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Sjaastad, L. A. 1962. “The Costs and Returns of Human Migration.” Journal of Political Economy 70 (5, Part 2): 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1086/258726.

- Son, D. G., and J. W. Hur. 2018. “A Study on the Effectiveness of the Relocating Public Organization on the Reduction of Population Concentration in the Seoul Metropolitan Area.” Journal of Korea Planning Association 53 (3): 5–18. https://doi.org/10.17208/jkpa.2018.06.53.3.5.

- Son, D. G., B. S. Kim, and J. W. Hur. 2018. “A Study on the Effectiveness of the Relocating Public Organization Policy Using System Dynamics: Focused on the Seoul Metropolitan Area.” Korean System Dynamics Review 19 (2): 33–51. https://doi.org/10.32588/ksds.19.2.2.

- Sorensen, A. 1990. “Virtuous Cycles of Growth and Vicious Cycles of Decline: Regional Economic Change in Northern New South Wales.” Change and Adjustment in Northern New South Wales. Armidale: University of New England.

- Swedish National Audit Office. 2023. Establish of Government Agencies Outside of Stockholm—Small Regional Contributions without Jeopardized Efficiency in the Long Term.

- Tucker, C. M., P. Torres-Pereda, A. M. Minnis, and S. A. Bautista-Arredondo. 2013. “Migration Decision-Making Among Mexican Youth: Individual, Family, and Community Influences.” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 35 (1): 61–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986312458563.

- Um, C. O., K. U. Roh, and S. W. Park. 2018. “An Analysis on the Determinants of Settlement and Return to the Local Youth.” Journal of Regional Studies 26 (3): 259–283. https://doi.org/10.31324/JRS.2018.09.26.3.259.

- Wu, J. 2014. “Urban Ecology and Sustainability: The State-Of-The-Science and Future Directions.” Landscape and Urban Planning 125:209–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.01.018.

- Xia, H., L. Qingchun, E. A. Baptista, and X.-D. Yang. 2022. “Spatial Heterogeneity of Internal Migration in China: The Role of Economic, Social and Environmental Characteristics.” PLoS One 17 (11): e0276992. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0276992.

- Yi, Y. J. 2021. “The Impact of Industrial Parks on Firms’ Productivity and Employment Growth.” Journal of Industrial Economics & Business 34 (4): 897–923. https://doi.org/10.22558/jieb.2021.8.34.4.897.

- Yoon, Y. M. 2018. “Characteristics and Challenges of Population Migration in Innovation Cities and Surrounding Areas.” KRIHS Policy Brief 693:1–6.

- Yoon, Y. M., W. S. Jeong, and J. H. Song. 2017. “Policy Issues of Population Growth and Migration of Innovation City.” Korea Research Institute for Human Settlement, Korea.

- Zhao, C., K. Wang, and K. Dong. 2023. “How Does Innovative City Policy Break Carbon Lock-In? A Spatial Difference-In-Differences Analysis for China.” Cities 136:104249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104249.

Appendix Appendix A.

Diverse definitions of “youth”

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), United Nations (UN), International Labour Organization (ILO), and World Health Organization (WHO) define “youth” as individuals aged 15 to 24 years (Brown Citation2021; Jeon Citation2019; Lim Citation2020), and the African Union and some Pacific nations define youth as individuals aged 15 to 34 years (African Union Commission Citation2006; Clendenning Citation2019). In South Korea, according to the Framework Act on Youth, youth is defined as those aged 19 to 34 years, while local government-related ordinances define youth flexibly, such as those aged 15 to 34 or 19 to 39, varying by jurisdiction.

Appendix B.

Comparative descriptive statistics of treated group and control groups by location type

In this study, we further examined through basic statistics whether there were differences between the treated and control groups before and after project completion according to location type (i.e., large and medium/small cities). Initially, based on the basic statistics for large cities, we observed that in the treated group, both NMR_YP_SMA and NMR_YP_non-SMA decreased after project completion. In contrast, in the control group, NMR_YP_non-SMA increased after project completion. For medium/small cities, the basic statistics show that in the treated group, both NMR_YP_SMA and NMR_YP_non-SMA increased after project completion. However, in the control group, both NMR_YP_SMA and NMR_YP_non-SMA decreased after project completion. Similar results were observed for NMR_YP_SA and NMR_YP_non-SA in the medium/small-city location type. Therefore, from , we can confirm that the youth population influx effect in regions where public institution relocation cities have been built has been more pronounced in medium/small cities than in large cities after project completion.

Table B1. Comparative basic statistics of treated and control groups by location type.

Appendix C.

Verification of the two-way fixed effect model

In this study, we used a two-way fixed effects model to control for time-invariant characteristics, such as unobserved unique regional characteristics, and the effects of year-specific common shocks that occur uniformly across regions each year (Choi, Kim, and Choi Citation2022). To determine the suitability of the two-way fixed effects model, we conducted the Hausman test, a verification method used to decide between fixed- and random-effects models. If the value derived from the Hausman test was statistically significant, no random effects were considered to exist. Based on the results of this test, use of a fixed-effects model appeared appropriate for this study ( = 0.087, p < 0.1). Therefore, we determined that employing the two-way fixed effects model in the DID model was also appropriate.