ABSTRACT

With the rapid development of digital tourism, more and more tourists are embracing this innovative mode of tourism. Digital tourism has attracted a large influx of tourists, which not only promotes the dissemination of local culture, but also promotes tourists’ intention to preserve culture. This study proposes a comprehensive framework authenticity, cultural experience, place attachment, satisfaction, and cultural protection intention, aiming to explore tourists’ cultural protection intention in digital tourism. To validate our framework, we use the Digital Intelligence Niushou as a case study and distributed a questionnaire to tourists, obtaining 408 valid responses. We analyzed the collected data using structural equation modeling (SEM). The results showed that place attachment and the four cultural experiences positively influenced both visitors’ satisfaction and cultural protection intention. Notably, “scientific knowledge” and “personal values” emerged as the biggest influences on cultural protection intention. Among the three types of authenticity, only objective authenticity and constructed authenticity positively influenced tourists’ satisfaction and cultural protection intention. This suggests that faithfully restored historical contexts play a key role in shaping tourists’ experiences and attitudes toward cultural protection in the field of digital tourism. This study provides a solid theoretical foundation for advancing digital tourism and enhancing tourists’ commitment to preserving cultural heritage. Our findings are important for digital tourism platforms to develop more effective optimization strategies, and can help managers to create more attractive, authentic and immersive tourism models to enhance tourist satisfaction and cultivate cultural protection intention.

1. Introduction

Cultural heritage represents a valuable legacy bestowed upon humanity by history, possessing significant historical, artistic, and economic value (Masoud, Mortazavi, and Torabi Farsani Citation2019). The development of cultural heritage tourism serves as an effective means of promoting the high-quality development of cultural tourism integration and the dissemination of culture (Deacon Citation2004). However, traditional tourism methods are gradually becoming inadequate in meeting the diverse needs of tourists, revealing numerous issues such as tourist sites with high similarity and lacking outstanding features, incomplete preservation of sites leading to the inability to comprehend all information, remote locations of some cultural heritage sites with inconvenient transportation, and the unattractiveness of traditional touring methods (Caton and Santos Citation2007; Kerstetter, Confer, and Graefe Citation2001). Henceforth, many exceptional heritage tourism sites are unable to be widely disseminated, resulting in limited tourism development. With the rapid advancement of the digital economy, the cultural tourism industry has also accelerated the process of digital transformation, with digital tourism being regarded as an effective solution to the aforementioned problems (Joo et al. Citation2021). Digital tourism is reliant on technologies such as AR, AI, big data, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence to offer tourists a multi-dimensional space, presenting cultural heritage in a digital format, and enabling them to gain an immersive experience and learn about cultural heritage (Alizadehsalehi, Hadavi, and Huang Citation2020; Mura, Tavakoli, and Pahlevan Sharif Citation2017). The digital transformation of cultural tourism integration represents a crucial aspect of modern industrial development and a significant approach to promoting the sustainable development of heritage tourism (Chung, Han, and Joun Citation2015). Currently, numerous countries are actively promoting the development of digital tourism, and the digital cultural tourism industry has encountered significant opportunities for development (Chung et al. Citation2018b; M. Lee et al. Citation2020; Mura, Tavakoli, and Pahlevan Sharif Citation2017; Zhou, Chen, and Wu Citation2022).

With the popularization of digital tourism platforms, the tourist experience has garnered significant academic attention. For instance, Jiang studied the impact of interactive methods, such as dynamic video images and sound effects, on tourists’ satisfaction and intention to continue using digital museum tours (Chung, Han, and Joun Citation2015). Li explored the relationship between tourists’ learning experience and satisfaction in AR lantern tours and evaluated the role of digital technology in enhancing tourists’ learning experience (X. Z. Li et al. Citation2022). Sun et al. appraised the factors associated with tourists’ intention to use digital tourism platforms and analysed the moderating effect of pandemic anxiety on the relationship between tourists’ intention to use and actual usage behaviour (Sun and Guo Citation2022). However, previous scholars have mainly focused on tourists’ intention to use the platform consistently and their behaviors, while research on the impact of digital tourism on tourists’ cultural preservation intention and related dimensions is still limited and lacks systematic exploration. Cultural preservation intention refers to tourists’ willingness and behavior to participate in and support cultural heritage preservation, which is a key factor in heritage tourism and sustainable development (Buckley Citation2012). Exploring the causes and influencing factors of tourists’ cultural preservation intention in digital tourism is of great significance to the construction of tourism industry. Therefore, this study aims to explore how digital tourism affects tourists’ cultural preservation intentions.

In the literature on heritage tourism, scholars have identified authenticity, cultural experience, and place attachment as crucial factors that influence tourists’ engagement with heritage tourism (Jia-Ming Citation2010; D. Lee and Lee Citation2017; Richards Citation2002; Scannell and Gifford Citation2010; M. Thompson, Ellis, and Wildavsky Citation1990; Xu, Wan, and Fan Citation2014). Authenticity, in particular, is a fundamental concept in heritage tourism, with Xu emphasising it as the core of cultural heritage conservation in his study on the sustainable development of heritage tourism in Hongcun (Xu, Wan, and Fan Citation2014). Authenticity can provide visitors with genuine environments and immersive experiences that enable them to comprehend the real history and positively impact their cultural identity (M. Thompson, Ellis, and Wildavsky Citation1990). The cultural experience, on the other hand, refers to tourists’ perception and understanding of the historical, cultural, and human significance of the place during their journey (Richards Citation2002). Luo’s study demonstrates that the cultural atmosphere of heritage sites can help tourists perceive the cultural connotations and deepen their heritage tourism experience (Jia-Ming Citation2010). Zhang’s study indicates that tourists can acquire cultural experience from the heritage environment, which contributes to the development of their cultural identity and sense of responsibility. This, in turn, can stimulate their willingness to preserve culture. Place attachment, on the other hand, refers to the emotional connection that tourists establish with heritage tourism places (Scannell and Gifford Citation2010). Research has demonstrated that tourists’ place attachment to a tourist destination generates an emotional response and influences tourist behaviour (D. Lee and Lee Citation2017). Therefore, authenticity, cultural experience, and place attachment can be considered as prerequisites for exploring tourists’ future intentions and behavioural intentions.

Drawing from the preceding discourse, a framework of “Authenticity – Cultural Experience – Place Attachment – Satisfaction – Cultural Preservation Intention” is formulated in this study, and the interrelationships between the variables are quantified through structural equation modelling. The main research questions of this study are as follows:

What factors in digital tourism can improve tourists’ satisfaction?

What factors in digital tourism can improve tourists’ cultural preservation intentions?

What is the relationship between authenticity, cultural experience, place attachment, satisfaction, and cultural preservation intention in digital tourism?

The the findings of the study inform the development of more efficacious optimization strategies for digital tourism platforms, enabling managers to construct more captivating, authentic, and immersive tourism models that enhance the visitor experience, augment visitor satisfaction, and foster cultural preservation intentions. From a long-term perspective, assessing tourists’ cultural preservation intentions has a salutary impact on the sustainability of digital tourism platforms.

2. Theoretical background and hypotheses

2.1. Digital tourism

In recent years, digital tourism has emerged as a prominent focus, leveraging digital technology to effectively safeguard and advance the management of cultural heritage sites. This reliance on digital technology has spurred rapid development in the cultural tourism industry, facilitating enhanced visitor experiences through improved service efficiency and quality at heritage sites. Additionally, digital transformation offers tourists tailored, personalized, and diverse services. Digital tourism uniquely enables visitors to immerse themselves in authentic re-creations of historical scenes, enriching their enjoyment of heritage sites (Alizadehsalehi, Hadavi, and Huang Citation2020). Studies in the field have highlighted significant advancements; for instance, Mura’s research underscores the role of virtual reality (VR) as a pivotal tool in augmenting the cultural experience of tourists, offering them immersive environments to appreciate historical charm (Mura, Tavakoli, and Pahlevan Sharif Citation2017). Similarly, Chung et al. have demonstrated that augmented reality (AR) technology not only enhances experiential value for tourists but also underscores its importance in heritage tourism (Chung, Han, and Joun Citation2015). Further, Chung’s findings indicate that the application of technologies like AR and VR in digital tourism markedly improves tourists’ perceptions of destinations and predicts future behavioral intentions (Chung et al. Citation2018b).

The debate surrounding the role of authenticity in digital tourism is a vibrant topic in contemporary research (X. Z. Li et al. Citation2022; Sun and Guo Citation2022). Authenticity lies at the heart of heritage tourism, with its exploration being a primary objective. Zhou’s research illustrates that authenticity significantly influences tourists’ willingness to revisit, engendering place attachment through immersive experiences and affecting their intentions to return, both directly and indirectly. In examining authenticity’s impact on tourists’ behavioral patterns, it is often conceptualized as an environmental stimulus. Cognitive evaluation theory suggests that exposure to authentic scenes in digital spaces triggers cognitive and emotional assessments by tourists, leading to specific emotional responses and ultimately shaping their behavioral patterns (Zhou, Chen, and Wu Citation2022). Li’s study on a digital app for exploring lantern exhibitions demonstrates that augmented reality technology can faithfully recreate these exhibitions, offering an authentic and objective spatial representation consistent with the concept of objective authenticity (X. Z. Li et al. Citation2022). This study also investigates the relationship between online lantern tour experiences and tourist satisfaction. Sun et al.’s research on digital museum usage focuses on continuous engagement, utilizing the Forbidden City Museum’s real scenes and narratives to develop an online tourism platform that adheres to historical accuracy and objective operational principles. This platform creates a structurally authentic environment, examining factors like performance expectations and habits in influencing tourists continued usage (Sun and Guo Citation2022). Lee et al. investigated how virtual reality quality affects user behavior, using a sample of tourists in the United States. They developed realistic virtual environments on VR-based websites, enhancing the users’ sense of presence in remote locations and constructing scenes of existential authenticity. Their findings corroborate the significant impact of vividness, system quality, and content quality in digital systems on visitors’ behavioral intentions (M. Lee et al. Citation2020).

In summary, the concept of authenticity has garnered significant attention in the existing literature on digital tourism. The perception of authenticity is a critical determinant influencing tourist behavior. Consequently, this study is dedicated to examining the correlation between authenticity and tourists’ behavior in digital tourism contexts.

2.2. Authenticity

The concept of Authenticity is multifaceted, and its application to tourism and tourists’ perceptual experience is a topic of considerable interest and research (Belhassen, Caton, and Stewart Citation2008; Kontogeorgopoulos Citation2017). MacCannell introduced the concept of Authenticity, contending that by examining Authenticity from various dimensions, researchers can gain a better understanding of visitors’ perceived experiences and behaviours (MacCannell Citation1973, Citation1999, Citation2008). The pursuit of Authenticity is regarded as a trend in tourism and a fundamental motivator for tourists to engage in tourism activities (Kolar and Zabkar Citation2010a). Other scholars have interpreted MacCannell’s Authenticity theory objectively and extended it by applying it to diverse tourism scenarios, analyzing the relationship between Authenticity and tourism objects, subjects, and agents, and exploring the impact of Authenticity on tourists’ tourism behaviour and experience (Reisinger and Steiner Citation2006; Xu, Wan, and Fan Citation2014). Authenticity is now widely employed in fields such as heritage tourism and the study of tourists’ behavioural intentions (Belhassen, Caton, and Stewart Citation2008; Kolar and Zabkar Citation2010a; MacCannell Citation1973, Citation2008).

2.2.1. Types of authenticity

In effect, authenticity is a complex concept, and scholars frequently broaden and study it from diverse perspectives, including postmodernism, constructivism, semiotics, and others (Lin and Liu Citation2018; Park, Choi, and Lee Citation2019; J. K. Thompson et al. Citation2012). This has led to the classification of Authenticity into various types, such as Objective Authenticity (Boorstin Citation1964; Waitt Citation2000), Constructive Authenticity (Cohen Citation1988), and Existential Authenticity (Steiner and Reisinger Citation2006).

The concept of Objective Authenticity posits that modern life fails to provide sufficient Authenticity, and that the past and the lives of others were more authentic (Chhabra, Healy, and Sills Citation2003; Steiner and Reisinger Citation2006). As such, tourism is seen as a means of pursuing Authenticity [39]. Objective Authenticity pertains to whether the information and content presented by a place accurately and completely reflects the actual tourism resources and environment, and whether it is free of misleading or exaggerated claims (Boorstin Citation1964), 40]. It is an objective attribute of a tourism object (Cohen and Cohen Citation2012; N. Wang Citation1999). Structural Authenticity, on the other hand, concerns the logical and regular storyline and mode of operation of the tourism venue, and whether it fosters a sense of identification and involvement for the visitor (Cohen Citation1988). This view posits that the Authenticity sought by tourists is actually a socially constructed symbolic Authenticity, where reality is a social construct based on socially accepted norms and ideologies (Chronis and Hampton Citation2008). Finally, Existential Authenticity refers to the potential for virtual scenarios and experiences to inspire a sense of being and an Authenticity associated with the activity. Tourism is a unique form of activity that allows for an authentic experience and the discovery of one’s true self (Olsen Citation2002; Steiner and Reisinger Citation2006). This can effectively account for the satisfaction and experience of tourism associated with the activity (Brown Citation2013; Olsen Citation2002).

2.2.2. Authenticity in relation to visitor satisfaction and cultural preservation intentions

In the domain of cultural heritage tourism, discussions surrounding the visitor experience are often centered on the concept of Authenticity, which refers to the novelty and authenticity of the experience [50]. Authenticity is a crucial concept in heritage conservation (Steiner and Reisinger Citation2006). Numerous studies have demonstrated that objective, constructive, and Existential Authenticity in heritage tourism have a positive impact on tourist satisfaction and cultural conservation behavior (Xu, Wan, and Fan Citation2014), 51 (S. Han, Yoon, and Kwon Citation2021; Shen, Guo, and Wu Citation2014; Yi et al. Citation2018). Yan Weijie’s research on embroidered artifacts, folk temple fairs, and opera performances, which embody objective, constructive, and Existential Authenticity, revealed that authenticity can positively influence visitors’ cultural identity (Yan and Chiou Citation2021), which in turn may impact their intentions to preserve their culture [56,57]. In his study on heritage conservation in Hongcun village, Xu H emphasized authenticity as the core of cultural heritage conservation, and international conservation documents have also incorporated the concept of Authenticity into local cultural heritage conservation planning and management policies (Xu, Wan, and Fan Citation2014). Lee argued that Authenticity provides an immersive experience for tourists, enabling them to better integrate into the scene, and highlighted the importance of perceived Authenticity on tourists’ tourism behavior and satisfaction (C. K. Lee et al. Citation2020). SEE et al. conducted a study on the relationship between perceived Authenticity and heritage tourism intentions and satisfaction, which revealed that Authenticity is a positive predictor of tourism behavior (See and Goh Citation2019). As such, Authenticity has become an increasingly important factor in enhancing tourist satisfaction and influencing cultural conservation intentions in cultural heritage tourism (S. Han, Yoon, and Kwon Citation2021). With the advancement of technology, digital technologies such as VR and AR may prove to be effective means for cultural heritage marketers to provide visitors with authentic experiences (S. Han, Yoon, and Kwon Citation2021; Steiner and Reisinger Citation2006). Pallud and Monod contend that the development of tourism in cultural heritage is increasingly being integrated with digital technologies, giving rise to a new form of tourism, digital tourism (Pallud and Monod Citation2010). Authenticity in digital tourism is a crucial topic that directly impacts the tourist’s authenticity experience of the destination, encompassing physical, social, cultural, and emotional aspects (Trunfifio and Campana Citation2020; Tussyadiah, Jung, and Tom Dieck Citation2018). As a novel form of tourism, there have been few studies examining the relationship between Authenticity in digital tourism and tourist satisfaction and cultural preservation intentions. Mura et al. contend that Authenticity constructed by digital tourism platforms should be accompanied by multiple physical, sensory, and psychological experiences, which would directly impact tourist behavior and emotional values and have an effect on tourism satisfaction (Mura, Tavakoli, and Sharif Citation2017). Sun J’s research found that in digital tourism, the authentic environment created by digital museums directly influences tourists’ sense of identification and belonging to the cultural heritage content [64], which can be considered to elicit their willingness to support the conservation of heritage sites (Nasser Citation2003; Nian et al. Citation2019). Seokho Han et al. demonstrated that digital technology influences tourists’ tourism decisions and experiences, and that tourists can derive Authenticity of experience value from the environment, which has a positive impact on their willingness to conserve cultural heritage tourism sites (S. Han, Yoon, and Kwon Citation2021).

The preceding discussion underscores the pivotal role of authenticity in digital tourism. Prior research categorizes authenticity into three dimensions: objective, structural, and existential. These dimensions collectively ensure that digital representations accurately and realistically depict local tourism resources. Additionally, they align constructed narratives with historical developments, thereby facilitating authentic experiences for tourists. Further, previous studies have confirmed the influence of authenticity in heritage tourism on tourists’ inclination to preserve culture and their overall satisfaction with the tourism experience. Based on these insights, we propose the following hypotheses.

H1:

Authenticity has a positive effect on visitor satisfaction.

H1a:

Objective Authenticity has a positive effect on visitor satisfaction.

H1b:

Constructive Authenticity has a positive effect on visitor satisfaction.

H1c:

Existential Authenticity has a positive effect on visitor satisfaction.

H2:

Authenticity has a positive effect on visitors’ cultural conservation intentions.

H2a:

Objective Authenticity has a positive effect on visitors’ cultural conservation intentions.

H2b:

Constructive Authenticity has a positive effect on visitors’ cultural conservation intentions

H2c:

Existential Authenticity has a positive effect on visitors’ cultural conservation intentions

2.3. Cultural experience

The process by which tourists visit historical and cultural heritage sites to gain knowledge and understanding of the cultural connotations, values, and lifestyles represented by such heritage through first-hand experience of the site, interactive communication, and emotional empathy is referred to as cultural experience (Richards Citation2002, Citation2018). In the context of heritage tourism, cultural experience not only enhances the cultural literacy and aesthetic ability of tourists but also promotes exchange and respect between different cultures, thereby contributing to the preservation and transmission of cultural heritage and the achievement of sustainable development (Cui, Liao, and Xu Citation2017). According to Reisinger, cultural tourism can help tourists seek multidimensional cultural experiences that are aesthetic, intellectual, emotional, or psychological in nature [70]. Reisinger further defines cultural experience as a process of learning, exploring, and perceiving culture for tourists [70]. As an important component of heritage tourism, cultural experiences can stimulate tourists’ motivation and behavioral intentions and enrich their tourism experience (S. Han, Yoon, and Kwon Citation2021; Wei et al. Citation2020).

2.3.1. Types of cultural experiences

Previous studies have expanded the concept of cultural experience into four important dimensions (Personal Valuing, High Culture, Scientific Knowledge, and Conservation Education), and have explored the relevant components of cultural experience in greater detail (Wei et al. Citation2020). (1) Personal Valuing is considered to be a crucial feature of heritage tourism (Yu Citation2012). The extent to which a tourist place is associated with Personal Valuing usually depends on the relationship between the place and certain historical events, legends, and famous people [73 (J. Zhang et al. Citation2008). Through heritage tourism, tourists can experience the Personal Valuing of different localities, customs, history, and culture [73 (J. Zhang et al. Citation2008). (2) High Culture can enhance the depth of cultural tourism and enrich the cultural experience of heritage tourism for tourists (McKercher Citation2002). High Culture refers to cultural forms with high artistic level and aesthetic value, such as architecture, painting, sculpture, music, dance, drama, poetry, and so on. High Culture reflects the history of human social development and civilizational achievements, and is the crystallization of human wisdom and creativity. Research by CUI shows that High Culture, such as poetry, calligraphy, and cliff carvings possessed by heritage tourism sites, can provide tourists with a profound touring experience [73]. According to research conducted by YU, elements such as poetry are important factors in enriching tourists’ cultural experience (Yu Citation2012). (3) Scientific Knowledge refers to the knowledge of natural or social sciences related to heritage, which can help tourists gain a deeper understanding and evaluation of the characteristics, formation process, conservation measures, and significance of heritage (Cater Citation2006). Previous studies have shown that tourists are interested in learning Scientific Knowledge during heritage tourism, and that this behavior increases tourist satisfaction and cultural identity. (4) Conservation Education in heritage tourism can enhance tourists’ cultural identity and respect. Through Conservation Education, tourists can comprehend the value and significance of the tourist destination and actively participate in the conservation and preservation of heritage resources (S. Y. Han Citation2006). Martini et al. have demonstrated that Conservation Education and conservation awareness in tourist destinations can be acquired through the perception of the environment (Martini, Buffffa, and Notaro Citation2017). Understanding the importance of preserving cultural heritage is also an integral cultural experience for tourists travelling.

2.3.2. The relationship between cultural experiences and visitor satisfaction and cultural preservation intention

Previous studies have shifted the discussion of cultural experience from conceptual elaboration to empirical research. In a study by Luo Jia-ming, it was pointed out that the cultural ambience of heritage sites allows tourists to experience cultural connotations up close and personal, and that special cultural experiences help to increase tourists’ tourism satisfaction (Jia-Ming Citation2010). Wang Jing’s study suggested that cultural connotations and cultural experiences are important influences in heritage tourism, and can enhance tourists’ perceptions of heritage culture, deepen their heritage tourism experiences, and influence tourist satisfaction. Wei C et al. showed that in heritage tourism, Person Valuing, Conservation Education, High Culture, and Scientific Knowledge related to cultural experiences have a significant impact on tourist satisfaction (Wei et al. Citation2020). Current research has provided compelling evidence regarding the positive influence of cultural experiences on visitor satisfaction.

Notwithstanding that there is no direct research that demonstrates the relationship between cultural experiences and tourists’ intentions to conserve, Zhang, in his study of cultural heritage conservation in Mexico, suggests on a cognitive level that tourists can gain special cultural experiences from the heritage environment, which can help to develop their cultural identity and sense of responsibility. In contrast, previous studies have pointed out that the cultural identity and sense of responsibility that tourists acquire towards heritage tourism sites can be considered to inspire their willingness to preserve culture (Nasser Citation2003; Nian et al. Citation2019). Li & Ma have shown that Conservation Education, which is experienced by the public through cultural experiences, can awaken people’s cultural participation and identity, which can contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage. Cui’s study of the “continuity” of cultural heritage suggests that the continued vitality of cultural heritage (e.g. cultural artefacts, monuments, ancient buildings, and other historical physical evidence) can inspire cultural preservation intentions (Cui, Liao, and Xu Citation2017). Previous studies have suggested that the above-mentioned historical physical evidence is a form of High Culture and can also be considered as a cultural experience (Cui, Liao, and Xu Citation2017; Yu Citation2012). Therefore, the cultural experiences that tourists encounter during heritage tourism may have a positive impact on tourists’ cultural conservation intentions.

Previous research has thoroughly examined the significance of cultural experiences in heritage tourism, with subsequent studies indicating that a destination’s cultural offerings substantially influence tourist satisfaction (Jia-Ming Citation2010; Wei et al. Citation2020). Nevertheless, the nexus between cultural experiences and tourists’ commitment to cultural preservation remains underexplored and warrants further investigation. Drawing on existing literature, this study broadens the scope of cultural experience into four dimensions. It delves into the facets of tourists’ cultural experiences in heritage tourism from a more comprehensive perspective and empirically investigates the connection between cultural experiences, tourist satisfaction, and their dedication to cultural conservation. The specific hypotheses are presented as follows.

H3:

Cultural experience has a positive impact on visitor satisfaction.

H3a:

Conservation Education has a positive effect on visitor satisfaction.

H3b:

High Culture has a positive effect on visitor satisfaction.

H3c:

Scientific Knowledge has a positive effect on visitor satisfaction.

H3d:

Person Valuing has a positive effect on visitor satisfaction.

H4:

Cultural experience has a positive effect on cultural conservation intentions.

H4a:

Conservation Education has a positive effect on cultural conservation intentions.

H4b:

High Culture has a positive effect on cultural conservation intentions.

H4c:

Scientific Knowledge has a positive effect on cultural conservation intentions.

H4d:

Person Valuing has a positive effect on cultural preservation intentions.

2.4. Place attachment, satisfaction, cultural preservation intentions

2.4.1. Place attachment

In tourism, place attachment refers to the emotional connection that tourists develop with a tourist destination, which is related to factors such as the tourist’s personal experience, motivation for travel, cultural experience, and interests (Scannell and Gifford Citation2010). Place attachment is a multidisciplinary concept that involves various aspects of psychology, sociology, and geography, and is often used to study tourists’ tourism behavior, including satisfaction, loyalty, and willingness to revisit the place (D. Lee and Lee Citation2017; Yuksel, Yuksel, and Bilim Citation2010; Y. Zhang, Park, and Song Citation2021). Many scholars have studied place attachment as an important variable, and research has shown that place attachment can increase tourists’ satisfaction and loyalty, enhance their identification with the destination, and promote its sustainable development (Scannell and Gifford Citation2010; Sop and Kervankıran Citation2023; Y. Zhang, Park, and Song Citation2021). Place attachment has emerged as a pivotal indicator for assessing the attractiveness and competitiveness of tourist destinations (Beery and Jönsson Citation2017).

2.4.2. Satisfaction

In tourism, satisfaction is defined as tourists’ evaluation of the venue’s environment, services, facilities, and other factors during the tourism process, and is a comprehensive feeling of tourists towards the tourism experience (Tang et al. Citation2022); whereas tourist satisfaction is related to the attractiveness of the tourist place, including the natural environment, human content, site facilities, and regional characteristics (Bosque and Martin Citation2008; Hou, Lin, and Morais Citation2005). Studies have shown that the more attractive a tourist place is to tourists, the higher their satisfaction (Hou, Lin, and Morais Citation2005). At the same time, tourism is also a consumption behavior and an experiential activity, and tourists will feel satisfied or dissatisfied with the service, quality, price, and other factors of the tourist place during the tourism process (Kolar and Zabkar Citation2010b). Satisfaction, as an important factor, has been extensively studied (Sop and Kervankıran Citation2023; Tang et al. Citation2022; Y. Zhang, Park, and Song Citation2021). Barsky & Labagh’s study pointed out that the assessment of user satisfaction constitutes one of the critical factors in achieving business success, as the user’s feelings towards a product or service can be evaluated intuitively through satisfaction testing (Barsky and Labagh Citation1992). Thereby, enhancing visitor satisfaction is incrementally becoming the kernel issue of tourism development and an effective way to promote sustainable tourism development (Y. Zhang, Park, and Song Citation2021).

2.4.3. Cultural preservation intention

The conservation and sustainable development of cultural heritage represents a significant global issue (Tian et al. Citation2020a). The intention of cultural conservation pertains to the degree to which heritage tourism sites are conserved by tourists (C. K. Lee et al. Citation2012). The cultural conservation intention of tourists encompasses not only the preservation of heritage tourism sites, but also the transmission and innovation of cultural heritage [93]. Currently, heritage tourism faces significant challenges, and the question of how to balance tourism development with heritage site conservation remains open (S. Han, Yoon, and Kwon Citation2021). Prior research has demonstrated that cultural heritage tourism enables tourists to gain a better understanding and experience of culture, which not only attracts tourists and disseminates local cultural characteristics, but also stimulates tourists’ awareness of cultural conservation and promotes the sustainable development of tourist sites [94].

2.4.4. Relationship between place attachment, satisfaction, and cultural preservation intention

The significance of place attachment and visitor satisfaction in heritage tourism has been extensively studied as a crucial indicator. Previous research has highlighted the importance of place attachment in determining visitor satisfaction. Kyu explored the correlation between place attachment and satisfaction in the context of older individuals residing in the city of Incheon, Korea. The study explored renewal strategies for age-friendly environments and revealed that place attachment had a substantial impact on the perceived satisfaction of older individuals (S. K. Lee Citation2017). Similarly, Sop and Serhat Adem examined the emerging tourist street and demonstrated that place attachment and place emotion directly influenced tourists’ satisfaction (Sop and Kervankıran Citation2023). The satisfaction experienced by tourists motivated them to develop supportive behaviours (Y. Zhang, Park, and Song Citation2021).

Previous research in the field of heritage tourism has revealed that tourists’ satisfaction with the destination has a significant impact on their cultural conservation intentions. Chuang et al. conducted a study on heritage tourism in Korea and found that tourists’ perceived satisfaction during AR tours can influence their tourism behaviour and conservation intentions at the destination (Chung et al. Citation2018a). Similarly, Buonincontri’s research demonstrated that the value experience gained through tourism can have a mapping effect on tourists’ emotions, such as the emergence of positive attitudes or satisfaction with the destination (Buonincontri, Marasco, and Ramkissoon Citation2017), 98]. This, in turn, can elicit tourists’ willingness to support heritage conservation [99]. Han S explored the impact of AR satisfaction on tourists’ supportive behaviours in his study of AR heritage tourism. The results indicated that tourists’ satisfaction significantly influenced their cultural conservation intentions, leading the researcher to conclude that these findings could create a competitive advantage for the destination and aid in achieving sustainability (S. Han, Yoon, and Kwon Citation2021).

The relationship between visitors’ place attachment and conservation intentions has been established by previous research. Beery’s study demonstrated that place attachment is a significant motivator for individuals’ willingness to conserve (Beery and Jönsson Citation2017). Lee D conducted a study using the Harz National Park in Germany as an example to assess visitors’ place attachment to the national park and their intentions to conserve it. The results indicated that higher levels of place attachment lead to stronger emotional responses to the environment, which in turn affects visitors’ conservation intentions (D. Lee and Lee Citation2017). Man Cheng’s study in Macau also supported this view, revealing that individuals with strong place attachment were more likely to support cultural heritage conservation and sustainability (Man Cheng, So, and Nang Fong Citation2022). Similarly, Scannell’s research in Australia found that individuals with strong place attachment were more likely to support the conservation of the tourism environment and culture due to their appreciation of sustainable development [101].

The foregoing discussion reveals that scholars have investigated the interplay among place attachment, satisfaction, and tourists’ intentions to preserve culture from various angles. However, this exploration has predominantly focused on traditional tourism models, with the correlation of these variables within digital heritage tourism remaining relatively unexplored. To address this gap and validate the relationship between place attachment, satisfaction, and cultural preservation intentions in digital tourism, this study posits the following hypotheses.

H5:

Place attachment has a positive effect on visitor satisfaction.

H6:

Satisfaction has a positive effect on visitors’ cultural preservation intention.

H7:

Place attachment has a positive effect on tourists’ intentions to conserve culture.

Drawing on the aforementioned literature and conceptual assumptions, the research model for this study is presented in .

3. Research methodology

3.1. Introduction to research methods

This study employed Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) as its methodological approach to construct and validate the theoretical framework. SEM, a widely used statistical technique, is adept at analyzing intricate causal relationships among variables by integrating factor loading analysis with multivariate regression analysis. This approach is particularly effective for assessing multiple variable interactions, making it ideal for theory construction and validation. To guarantee the scientific rigor of our research, we followed a meticulous process for data computation and analysis as suggested by Anderson et al (Hair et al. Citation1998). Initially, the research team undertook preliminary data processing, which encompassed data integration and statistical analysis. This was followed by an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to uncover the underlying structure and factor relationships within the data and ascertain the factor loading coefficients. Subsequent to the EFA, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using AMOS software. This step was crucial in evaluating the measurement model’s reliability and validity, as well as assessing the model’s overall fit, by examining item loadings, reliability, and average extracted variance. Path analyses were then performed to validate the hypothesized relationships within the research model, exploring the causal linkages between variables and their quantitative impacts. Throughout this analytical process, emphasis was placed on the statistical significance of the model and fit indices, including CFI, TLI, and RMSEA. This focus ensured the statistical robustness of the model, its practical applicability, and provided robust statistical support for the construction and validation of theories.

3.2. Background of the study

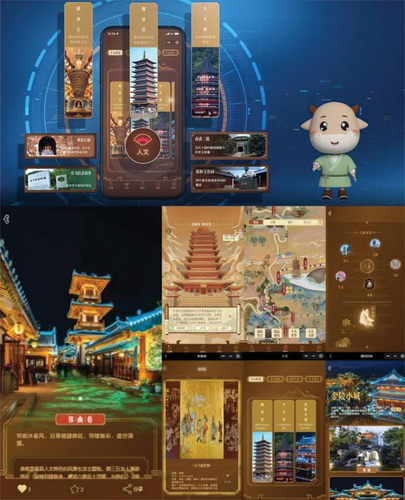

Niushou Mountain, located in Nanjing, is renowned as one of the four most famous scenic spots in the area and is a national cultural heritage site. The mountain boasts breathtaking natural scenery and a rich cultural heritage, including its significance as the site of Yue Fei’s resistance against the Jin Dynasty and the former residence of Zheng He. Additionally, Niushou Mountain is home to numerous historical monuments, such as cliff carvings, Hongjue Temple Pagoda, and Zheng He Cultural Park. In February 2023, Niushou Mountain launched the “Digital Intelligence Niushou” tourism platform on the WeChat platform, utilizing cutting-edge technologies such as cloud rendering, AR, AI, graph computing, cloud computing, and NLP. This platform aims to digitize and technologize Niushou Mountain’s heritage tourism, providing visitors with an immersive experience through panoramic roaming, animation effects, and 3D rendering. The “Digital Intelligence Niushou” platform offers various modules, including knowledge mapping, humanistic explanation, digital touring, trendy play experience, and metaspace, allowing visitors to experience the digital charm of cultural heritage (). Simultaneously, the “Digital Intelligence Niushou” platform also highlights the heritage culture of Niushou Mountain, including the Intangible Cultural Heritage Silk Carpet Painting. This feature documents and showcases the historical prosperity of Niushou Mountain, recreating it in three dimensions in the digital world. Visitors can experience the humanism and connotation of the site in an immersive way. As a result, the “Digital Intelligence Niushou” tourism platform has become a crucial tool for communicating Jinling culture and offering visitors a unique and diverse digital experience while traveling.

As a renowned digital tourism platform in China, Digital Intelligence Niushou leverages digital technology to restore historical authenticity and offer visitors a rich cultural experience. This study thus employs Digital Intelligence Niushou as a case study to understand the relationship between authenticity, cultural experience, place attachment, and tourists’ cultural preservation intentions.

3.3. Questionnaire design

All items measured in this study were derived from the literature on heritage tourism, authenticity, cultural experiences, and place attachment. The construct of authenticity comprised 12 items, which were further divided into four Objective Authenticity, four Existential Authenticity, and four Constructive Authenticity. These items were adapted from previous studies conducted by Tian D, Zhang T, and Lu L (Lu, Chi, and Liu Citation2015; Tian et al. Citation2020b; T. Zhang, Yin, and Peng Citation2021). The cultural experience construct consisted of 16 items, which were categorized into four Conservation Education, four High Culture, four Scientific Knowledge, and four Person Valuing. These items were generated based on the research of Wei C (Wei et al. Citation2020). Place attachment was assessed using four items, which were drawn from the studies of Lee D and Beery T (Beery and Jönsson Citation2017; D. Lee and Lee Citation2017). Satisfaction was measured using five items, which were based on the study by Tang H and Barsky (Barsky and Labagh Citation1992; Tang et al. Citation2022). The cultural preservation intention construct was composed of four items, which were derived from Han S’s study (S. Han, Yoon, and Kwon Citation2021). A 7-point Likert scale was employed to describe perceptions of the items measured, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with respondents selecting the appropriate value based on their feelings about digital tourism. The questionnaire also included five demographic questions (age, gender, education, occupation, income).

Following the development of the initial questionnaire, a pilot survey was administered to students who had utilized “The Digital Intelligence Niushou” to assess the validity of the questionnaire and the accuracy of the items. A total of 72 questionnaires were collected, and based on the feedback received, adjustments were made to the presentation of the items Objective Authenticity, Constructive Authenticity, Conservation Education, and High Culture. The final questionnaire content and measurement items for this study are presented in .

3.4. Sampling and data collection

The official survey for this study was conducted between April 2023 and May 2023 at tourist-heavy sites in Nanjing, including Fuzi Temple, Deji Art Museum, Xinjiekou, and Niushou Mountain. To ensure the validity of the data collected, the researchers first confirmed that visitors had previously used “The Digital Intelligence Niushou”. Subsequently, the objectives of the study were explained to the target group, and the measurement items were clarified to ensure that visitors understood the meaning of each item. Finally, visitors were invited to participate in the survey, and all questionnaires were completed in the presence of the researcher. A total of 445 questionnaires were collected for this study, and 37 invalid questionnaires were excluded, resulting in 408 valid questionnaires, representing a validity rate of 91.68%. This met the sample collection requirements proposed by WU (Wu Citation2010).

4. Data analysis and results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

presents the demographic characteristics of the sample, and the results of the analysis indicate that the majority of respondents were concentrated in the age groups of 18–25 (40.19%) and 16–34 (27.46%). The gender distribution was slightly skewed towards female respondents (52.94%) compared to male respondents (47.06%). In terms of educational attainment, 37.51% of respondents held a bachelor’s degree, while 14.46% held a postgraduate degree. The largest occupational group among respondents was students (35.53%), followed by white-collar workers (17.65%) and freelancers (16.67%). The distribution of visitors’ income revealed that the highest number of people fell within the 5,000–10,000 range (37.25%), followed by those earning below 2,500 (29.90%), most of whom were students.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of respondents’ characteristics.

4.2. The measurement model assessment

In this paper, the collected data were analyzed for reliability and validity using SPSS 26.0 software. As shown in , the KMO test yielded a coefficient of 0.923 (the suggested range: 0 to 1). The closer the coefficient is to 1, the better the validity of the questionnaire. Additionally, the significance of Bartlett’s spherical test was found to be infinitely close to 0, indicating that the questionnaire has good reliability.

Table 2. KMO and Bartlett’s inspection.

To test the measurement model, this study employed Anderson’s proposed confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) validation procedure (Hair et al. Citation1998). The CFA results, as presented in , indicate that the overall fit of the model is good, with all values reaching the desired level. Specifically, the chi-squared/df ratio was 1.846 (within the suggested range of 1.0 to 3.0), the RMSEA was 0.046 (below the recommended threshold of 0.10), and the NFI, IFI, and CFI values were 0.886, 0.944, and 0.944, respectively (all exceeding the recommended value of 0.85). These results suggest that all values are within acceptable limits, indicating that the model is a good fit.

Table 3. The values of fit indices.

To assess the dependability and validity of the data, this study measured Cronbach’s alpha, Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE). displays the results. The Cronbach’s alpha for all variables ranged from 0.838–0.943, satisfying the criterion of greater than 0.70 as proposed by Nunnally & Bernstein in 1994 (Eisinga, Te Grotenhuis, and Pelzer Citation2013). The CR was deemed acceptable at greater than or equal to 0.7, signifying good agreement between variables (Muilenburg and Berge Citation2005). The CR values for all variables in this study were between 0.838–0.944, meeting the aforementioned requirements (Ahmad, Zulkurnain, and Khairushalimi Citation2016). AVE values are expected to be greater than 0.5 (Fornell and Larcker Citation1981), while the AVE in this study was between 0.562–0.943, indicating that the robustness of the data collected in this study.

Table 4. Results of confirmatory factor analysis.

and reports the path coefficients for this study. The significance is indicated by P in the table (p < 0.001 signifies ”***‘; P between 0.001 and 0.01 signifies ’**‘; P between 0.01 and 0.05 signifies ’*”; all other cases are not significant) (Davis Citation1989; Wu Citation2010). The findings reveal that Objective Authenticity significantly influences satisfaction (H1a: β = 0.168, p = 0.003) and cultural preservation intention (H2a: β = 0.147, p = 0.006), thus supporting hypotheses H1a and H2a. Similarly, Constructive Authenticity exerts a significant impact on satisfaction (H1b: β = 0.111, p = 0.016) and cultural preservation intention (H2b: β = 0.210, p < 0.001), confirming hypotheses H1b and H2b. However, Existential Authenticity does not significantly affect satisfaction (H1c: β = 0.109, p = 0.063) or cultural protection intention (H2c: β=-0.010, p = 0.853), rendering hypotheses H1c and H2c invalid. Conservation Education significantly influences satisfaction (H3a: β = 0.149, p = 0.005) and intention to protect culture (H4a: β = 0.110, p = 0.029), supporting hypotheses H3a and H4a. High Culture also has a significant effect on satisfaction (H3b: β = 0.138, p = 0.003) and intention to preserve culture (H4b: β = 0.100, p = 0.025), validating hypotheses H3b and H4b. In addition, Scientific Knowledge significantly impacts satisfaction (H3c: β = 0.115, p = 0.022) and cultural preservation intention (H4c: β = 0.168, p < 0.001), upholding hypotheses H3c and H4c. Person Valuing significantly affects satisfaction (H3d: β = 0.123, p = 0.010) and cultural preservation intentions (H4d: β = 0.163, p < 0.001), corroborating hypotheses H3d and H4d. Place attachment significantly influences satisfaction (H5: β = 0.222, p < 0.001) and cultural preservation intention (H7: β = 0.155, p = 0.002), supporting hypothesis H5 and H7. Finally, visitor satisfaction significantly affects cultural preservation intention (H6; β = 0.161, p = 0.006), confirming hypothesis H6.

Table 5. Path analysis results.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The research topic of great significance is the heritage, innovation, and sustainability of cultural heritage. Prior studies have primarily focused on tourists’ loyalty and willingness to revisit heritage tourism sites. However, there is a relative dearth of research on tourists’ cultural conservation intentions and related dimensions. In this context, this study seeks to appraise the effects of cultural experience, authenticity, and place attachment on tourist satisfaction and cultural preservation intentions in the context of digital heritage tourism. To test the relationship between these variables, a new theoretical model was constructed. The sample data was obtained through offline interviews and questionnaires, and a total of 408 valid questionnaires were collected. This study formulated seventeen hypotheses, and the results indicated that all hypotheses were successfully tested, except for H1c and H2c.Among them, among the variables with the greatest degree of influence on tourists’ cultural Protection intentions and satisfaction are objective authenticity, structural authenticity, personal values, and conservation education.

Firstly, the study found that among the three types of authenticity, Objective Authenticity and Constructive Authenticity have a positive impact on tourists’ cultural preservation intentions, with Constructive Authenticity playing a greater role. This suggests that digital tourism platforms can optimize the travel experience, increase satisfaction, and generate cultural identity and preservation intentions by constructing scenarios, storylines, and modes of operation that give visitors a sense of authentic history. In addition, Objective Authenticity can positively impact visitors’ behavioral intentions. Previous research has shown that higher user perceptions of Objective Authenticity at heritage sites are more likely to increase visitor satisfaction and cultural preservation intentions. The hypotheses of Objective Authenticity and Constructive Authenticity established in this study are generally consistent with the findings of previous academic research (S. Han, Yoon, and Kwon Citation2021; Yan and Chiou Citation2021; T. Zhang, Yin, and Peng Citation2021). However, the findings regarding Existential Authenticity are not consistent with previous scholars (S. Han, Yoon, and Kwon Citation2021; Yan and Chiou Citation2021; T. Zhang, Yin, and Peng Citation2021). This may be due to the current level of technology in digital tourism, which does not yet allow visitors to experience the same level of immersion as in real-life settings. Therefore, tourists’ perception of Existential Authenticity at heritage sites may not be high enough to significantly impact tourist satisfaction and cultural preservation intentions. This study reveals that both objective and structural authenticity significantly enhance digital tourism development. Objective authenticity equips digital tourism platforms with accurate, realistic historical depictions, aligning with tourists’ expectations for authentic experiences via digital mediums. It aids in educating tourists about genuine history and culture, preserving their original forms and traditions, thereby fostering a deeper understanding and appreciation of cultural heritage. On the other hand, structural authenticity enhances tourist engagement and immersion by creating virtual environments that mirror historical logic and cultural essence, thereby enriching the tourist experience. Moreover, by reconstructing authentic historical narratives and settings, structural authenticity not only educates tourists about history and culture but also fosters an emotional connection, augmenting their identification with and commitment to preserving cultural heritage. Together, objective and structural authenticity are pivotal in digital tourism’s evolution, offering fresh perspectives and methods for the sustainable development of cultural heritage. By cultivating spatial authenticity, digital tourism serves as a conduit between the past and future, and between tradition and innovation.

Secondly the study has identified four cultural experiences that have a positive impact on visitors’ cultural conservation intentions, filling a research gap and providing empirical support for subsequent studies. Scientific Knowledge and personal valuing play a greater role in this regard. Digital tourism platforms that provide virtual facilitators to visitors can help them learn more about cultural heritage and increase their satisfaction. The more visitors learn about the Scientific Knowledge of cultural heritage and the unique personal valuing that heritage sites bring, the more they discover the importance of conservation and sustainable development. Additionally, Conservation Education and High Culture can optimize visitor satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Digital tourism can showcase and restore damaged High Culture (e.g. ancient buildings and cliff carvings, etc.) providing visitors with a rich cultural experience and an opportunity to learn about Conservation Education while perceiving the fascination brought by cultural heritage.This study demonstrates that conservation education significantly enhances tourists’ understanding of cultural heritage and its preservation. Digital tourism platforms, by providing interactive educational content, enable tourists to learn about protecting and preserving heritage while engaging with it. Utilizing digital media for conservation education strengthens the tourists’ commitment to cultural preservation, motivating continued support even after their experience concludes. Digital tourism, merged with high culture elements like classical music, painting, calligraphy, and ancient architecture, unlocks new potential. These core components of cultural heritage are vividly brought to life through technologies such as virtual exhibition halls, augmented reality (AR), and virtual reality (VR). Digitalization of high culture not only broadens cultural heritage’s audience but also enhances the tourism experience. Moreover, the integration of scientific explanations on digital platforms deepens tourists’ understanding of cultural heritage, background, and history. Interactive teaching and simulated displays effectively communicate complex historical and scientific concepts. Additionally, digital tourism experiences enriched with scientific knowledge invigorate tourists’ exploratory spirit and engagement in cultural heritage. Personal values discovered through digital tourism foster deeper emotional connections by linking spatial scenes to personal experiences. When tourists perceive personal value in digital heritage tourism, they are more inclined to revisit and share their experiences on social platforms, positively impacting cultural heritage’s dissemination and preservation. In summary, four key dimensions of cultural experience are critical in digital tourism, enhancing both the quality of tourists’ experiences and their involvement in cultural heritage preservation.

Finally the study has confirmed that place attachment has a significant positive effect on visitor satisfaction and cultural preservation intentions, which is consistent with the findings of Zhang Y and Man Cheng (Man Cheng, So, and Nang Fong Citation2022; Y. Zhang, Park, and Song Citation2021). Place attachment is an important antecedent variable for tourist satisfaction and cultural conservation intentions. When tourists develop emotional links to the environment, history, culture, and storyline of a site during a tour, it optimizes the tourist experience and enhances satisfaction. Additionally, visitors who develop place attachment to a heritage site will have a high emotional response to the environment, inspiring their sense of responsibility and cultural conservation intentions.The study’s findings indicate that place attachment fosters a profound emotional bond between tourists and cultural heritage sites in digital tourism. This bond is further reinforced through virtual interactions and narrative storytelling, which maintain engagement and involvement throughout the digital tourism experience. A stronger emotional attachment correlates with an increased willingness to preserve the site, contributing significantly to the long-term conservation and sustainable development of cultural heritage. Additionally, place attachment amplifies visitor satisfaction by offering personalized and meaningful experiences. It achieves this by conveying the unique stories and history of heritage sites via digital platforms, thereby deepening visitors’ cultural comprehension and identification with the site.

The results of this study provide a valuable contribution to the extant literature on digital tourism, heritage preservation, and sustainable development by means of dependable and valid measurement variables. The study evaluates variables associated with cultural experience, authenticity, and place attachment, emphasizing their crucial role in digital tourism. In addition, the findings of the current study enhance practitioners’ comprehension of the significance of authenticity and cultural experience in digital tourism, as well as how to design genuine and immersive tourism activities for visitors.

6. Suggestions

Drawing upon our research and analysis, we suggest the following recommendations to enhance tourists’ satisfaction with tourism and their intentions to preserve culture in digital tourism, while simultaneously promoting sustainable development of heritage tourism.

To enhance tourists’ satisfaction with tourism and their intentions to preserve culture in digital tourism, tourism managers should prioritize the creation of authenticity, particularly constructive authenticity and objective authenticity. Digital tourism platforms must demonstrate respect for the essence and values of heritage sites, striving to restore historical situations and cultural scenes as accurately as possible to provide visitors with an authentic cultural experience. Additionally, the future of digital tourism should prioritize the improvement of platform systems’ quality and credibility, leveraging digital technology to enhance tourism interactivity and participation. This will enable visitors to transition from passive tourists to active participants, with examples including bringing cultural heritage to life, facilitating visitors’ perception of it from multiple perspectives, enabling interaction and learning, and eventually increasing visitor satisfaction and cultural preservation intentions.

Digital tourism should prioritize the impact of cultural experiences on the platform, providing a diverse environment for tourists. In subsequent development, the digital tourism platform can create an interesting, rich, and enjoyable scene based on the cultural characteristics of the heritage site, enabling visitors to participate in the recreation and re-creation of history and culture. This provides them with the opportunity to experience the daily lives of historical figures, customs, and traditions, as well as to learn about the knowledge and intrinsic value of cultural heritage. Compared to traditional, serious history education, this type of tourism stimulates visitors’ interest in heritage tourism and allows them to actively participate in digital tourism. It enhances their satisfaction and stimulates their sense of responsibility for cultural preservation.

In the future, digital tourism platforms may concentrate on fostering tourists’ place attachment to cultural heritage environments and enhancing their cultural identity and emotional connections to heritage sites. Personalized service content can be provided by the platform based on tourists’ interests, enabling them to select the appropriate experience according to their preferences and pace. Concurrently, digital heritage tourism can establish communication channels between tourists and heritage communities, craftspeople, historians, scholars, and other researchers, allowing tourists to engage with experts and scholars closely and gain a comprehensive understanding of cultural heritage, thereby creating an emotional attachment. In addition, digital tourism platforms should motivate tourists to actively participate in the heritage and conservation of heritage sites and contribute to the sustainable development of cultural heritage.

7. Limitation

The conservation and sustainability of cultural heritage emerge as a highly significant and pertinent subject of research. Accordingly, this study delves into the multitude of factors that influence tourist satisfaction within the domain of digital tourism, while simultaneously analyzing the profound effects of cultural experience, authenticity, and place attachment on tourists’ intentions toward cultural conservation. Nonetheless, several limitations necessitate due consideration for future research endeavors. Primarily, this study fails to encompass other influential factors that impact cultural conservation intentions. Subsequent research should seek to explore the potential influence of additional variables, such as cultural identity, cultural confidence, system quality, visual perception, and other relevant factors, on tourists’ cultural conservation intentions within the context of digital tourism. Secondly, this study predominantly focuses on the perceptions of domestic tourists concerning digital tourism. Future research should expand the sample size to incorporate international tourists and conduct quantitative comparative studies. This expansion would enable an appraisal of potential disparities in perceptions and behaviors towards digital tourism platforms across various countries. Finally, given that digital tourism represents an emerging form of tourism, this study only explores the impact of digital tourism platforms on tourists based on the current level of technological advancement. As technology progresses, subsequent studies should investigate the influence of tourism platforms on tourist satisfaction and intentions for cultural preservation within a more extensive temporal framework.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Junjie Li

Junjie Li was born in Wuhu, Anhui Province, China, and is currently pursuing a master’s degree in art and design at Nanjing Forestry University. His main research interests are in the fields of digital tourism, rural revitalisation and heritage conservation. He has received national scholarships and top prizes in many competitions at home and abroad. His articles have recently been published in journals such as Land and Buildings.

Xiangbin Peng

Xiangbin Peng received his Bachelor’s Degree from Xi’an Academy of Fine Arts, majoring in Architectural Environment Design. He is currently studying for a Master of Art and Design degree at Nanjing Forestry University. His main research interests are cultural heritage research, architectural design and sustainable landscape design. His research results have been published in high level international journals such as Land and Buildings. He has won national competitions in China and academic scholarships from Xi’an Academy of Fine Arts and Nanjing Forestry University.

Xiaodong Liu

Xiaodong Liu is a professor at Donghua University. His research mainly involves the fields of rural revitalisation and heritage conservation.

Huanchen Tang

Huanchen Tang, a PhD candidate in design at Donghua University, is interested in finding ways to promote rural tourism from the history and culture of the countryside itself. Her work has recently been published in Sustainability, Buildings.

Wei Li

Wei Li is a graduate student at the School of Art and Design, Nanjing Forestry University. His research interests are in the fields of rural revitalisation and industrial protection.

References

- Ahmad, S., N. N. A. Zulkurnain, and F. I. Khairushalimi. 2016. “Assessing the Validity and Reliability of a Measurement Model in Structural Equation Modeling (SEM).” Journal of Advances in Mathematics Computer Science 15 (3): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJMCS/2016/25183.

- Alizadehsalehi, S., A. Hadavi, and J. C. Huang. 2020. “From BIM to Extended Reality in AEC Industry.” Automation in Construction 116:103254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2020.103254.

- Barsky, J. D., and R. Labagh. 1992. “A Strategy for Customer Satisfaction.” Cornell Hotel & Restaurant Administration Quarterly 33 (5): 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/001088049203300524.

- Beery, T., and I. K. Jönsson. 2017. “Outdoor Recreation and Place Attachment: Exploring the Potential of Outdoor Recreation within a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.” Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 17:54–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2017.01.002.

- Belhassen, Y., K. Caton, and W. P. Stewart. 2008. “The Search for Authenticity in the Pilgrim Experience.” Annals of Tourism Research 35 (3): 668–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.03.007.

- Boorstin, D. J. 1964. The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Bosque, I. R., and H. S. Martin. 2008. “Tourist Satisfaction: A cognitive-affective Model.” Annals of Tourism Research 35 (2): 551–573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2008.02.006.

- Brown, L. 2013. “Tourism: A Catalyst for Existential Authenticity.” Annals of Tourism Research 40:176–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.08.004.

- Buckley, R. 2012. “Sustainable Tourism: Research and Reality.” Annals of Tourism Research 39 (2): 528–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.02.003.

- Buonincontri, P., A. Marasco, and H. Ramkissoon. 2017. “Visitors’ Experience, Place Attachment and Sustainable Behaviour at Cultural Heritage Sites: A Conceptual Framework.” Sustainability 9 (7): 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071112.

- Cater, E. 2006. “Ecotourism as a Western Construct.” Journal of Ecotourism 5 (1–2): 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040608668445.

- Caton, K., and C. A. Santos. 2007. “Heritage Tourism on Route 66: Deconstructing Nostalgia.” Journal of Travel Research 45 (4): 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507299572.

- Chhabra, D., R. Healy, and E. Sills. 2003. “Staged Authenticity and Heritage Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research 30 (3): 702–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(03)00044-6.

- Chronis, A., and R. D. Hampton. 2008. “Consuming the Authentic Gettysburg: How a Tourist Landscape Becomes an Authentic Experience.” Journal of Consumer Behaviour 7 (2): 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.241.

- Chung, N., H. Han, and Y. Joun. 2015. “Tourists’ Intention to Visit a Destination: The Role of Augmented Reality (AR) Application for a Heritage Site.” Computers in Human Behaviour 50:588–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.068.

- Chung, N., H. Lee, J. Y. Kim, and C. Koo. 2018a. “The Role of Augmented Reality for Experience-Influenced Environments: The Case of Cultural Heritage Tourism in Korea.” Journal of Travel Research 57 (5): 627–643. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517708255.

- Chung, N., H. Lee, J. Y. Kim, and C. Koo. 2018b. “The Role of Augmented Reality for Experience-Influenced Environments: The Case of Cultural Heritage Tourism in Korea.” Journal of Travel Research 57 (5): 627–643. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517708255.

- Cohen, E. 1988. “Authenticity and Commoditization in Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research 15 (3): 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(88)90028-X.

- Cohen, E., and S. A. Cohen. 2012. “Current Sociological Theories and Issues in Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research 39 (4): 2177–2202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.07.009.

- Cui, Q. M., X. H. Liao, and H. G. Xu. 2017. “Tourist experience of nature in contemporary China: A cultural divergence approach.” Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change 15 (3): 248–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2015.1113981.

- Davis, F. D. 1989. “Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology.” MIS Quarterly 13 (3): 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008.

- Deacon, H. 2004. “Intangible Heritage in Conservation Management Planning: The Case of Robben Island.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 10 (3): 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/1352725042000234479.

- Eisinga, R., M. Te Grotenhuis, and B. Pelzer. 2013. “The Reliability of a Two-Item Scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown?” International Journal of Public Health 58 (4): 637–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-012-0416-3.

- Fornell, C., and D. F. Larcker. 1981. “Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics.” Journal of Marketing Research 18 (3): 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313.

- Hair, J. F., R. E. Anderson, R. L. Tatham, and W. C. Black. 1998. Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings. 5th ed. New York: Macmillan.

- Han, S. Y. 2006. “Investigation of Experience Dimensions by Heritage Tourists: Focusing on Practical and Hedonic Values.” Journal of Tourism Sciences 30 (3): 11–28.

- Han, S., J. H. Yoon, and J. Kwon. 2021. “Impact of Experiential Value of Augmented Reality: The Context of Heritage Tourism.” Sustainability 13 (8): 4147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084147.

- Hou, J. S., C. H. Lin, and D. B. Morais. 2005. “Antecedents of Attachment to a Cultural Tourism Destination: The Case of Hakka and Non-Hakka Taiwanese Visitors to Pei-Pu, Taiwan.” Journal of Travel Research 44 (2): 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287505278988.

- Jia-Ming, L. 2010. “The Development of Heritage Tourism: The Integration of Heritage Site Spirit and Experiential Tourism.” Journal of Tourism 25 (5): 6–7.

- Joo, D., W. Xu, J. Lee, C. K. Lee, and K. M. Woosnam. 2021. “Residents’ Perceived Risk, Emotional Solidarity, and Support for Tourism Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 19:100553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100553.

- Kerstetter, D. L., J. J. Confer, and A. R. Graefe. 2001. “An Exploration of the Specialization Concept within the Context of Heritage Tourism.” Journal of Travel Research 39 (3): 267–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750103900304.

- Kolar, T., and V. Zabkar. 2010a. “A Consumer-Based Model of Authenticity: An Oxymoron or the Foundation of Cultural Heritage Marketing?” Tourism Management 31 (5): 652–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.07.010.

- Kolar, T., and V. Zabkar. 2010b. “A Consumer-Based Model of Authenticity: An Oxymoron or the Foundation of Cultural Heritage Marketing?” Tourism Management 31 (5): 652–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2009.07.010.

- Kontogeorgopoulos, N. 2017. “Finding Oneself While Discovering Others: An Existential Perspective on Volunteer Tourism in Thailand.” Annals of Tourism Research 65:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.04.006.

- Lee, S. K. 2017. “Influencing Relationships Between the Neighborhood Disorder and the Satisfaction of Elderly Residential Environment - the Place Attachment and the Social Capital as Parameters.” Journal of SH Urban Research & Insight 7 (1): 137–156. https://doi.org/10.26700/shuri.2017.04.7.1.137.

- Lee, C. K., M. S. Ahmad, J. F. Petrick, Y.-N. Park, E. Park, and C.-W. Kang. 2020. “The Roles of Cultural Worldview and Authenticity in tourists’ Decision-Making Process in a Heritage Tourism Destination Using a Model of Goal-Directed Behavior.” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 18:100500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100500.

- Lee, C. K., L. J. Bendle, Y. S. Yoon, and M. J. Kim. 2012. “Thanatourism or Peace Tourism: Perceived Value at a North Korean Resort from an Indigenous Perspective.” International Journal of Tourism Research 14 (1): 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.836.

- Lee, D., and J. H. Lee. 2017. “A Structural Relationship Between Place Attachment and Intention to Conserve Landscapes–A Case Study of Harz National Park in Germany.” Journal of Mountain Science 14 (5): 998–1007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-017-4366-3.

- Lee, M., S. A. Lee, M. Jeong, and H. Oh. 2020. “Quality of Virtual Reality and Its Impacts on Behavioral Intention.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 90:102595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102595.

- Li, X. Z., C. C. Chen, X. Kang, and J. Kang. 2022. “Research on Relevant Dimensions of Tourism Experience of Intangible Cultural Heritage Lantern Festival: Integrating Generic Learning Outcomes with the Technology Acceptance Model.” Frontiers in Psychology 13:13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.943277.

- Lin, Y. C., and Y. C. Liu. 2018. “Deconstructing the Internal Structure of Perceived Authenticity for Heritage Tourism.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 26 (12): 2134–2152. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2018.1545022.

- Lu, L., C. G. Chi, and Y. Liu. 2015. “Authenticity, Involvement, and Image: Evaluating Tourist Experiences at Historic Districts.” Tourism Management 50:85–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.01.026.

- MacCannell, D. 1973. “Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings.” American Journal of Sociology 79 (3): 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1086/225585.

- MacCannell, D. 1999. The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- MacCannell, D. 2008. “Why It Never Really Was About Authenticity.” Society 45 (4): 334–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-008-9110-8.

- Man Cheng, E. N., S. I. So, and L. H. Nang Fong. 2022. “Place Perception and Support for Sustainable Tourism Development: The Mediating Role of Place Attachment and Moderating Role of Length of Residency.” Tourism Planning & Development 19 (4): 279–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2021.1906740.

- Martini, U., F. Buffffa, and S. Notaro. 2017. “Community Participation, Natural Resource Management and the Creation of Innovative Tourism Products: Evidence from Italian Networks of Reserves in the Alps.” Sustainability 9 (12): 2314. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122314.

- Masoud, H., M. Mortazavi, and N. Torabi Farsani. 2019. “A Study on tourists’ Tendency Towards Intangible Cultural Heritage as an Attraction (Case Study: Isfahan, Iran).” City, Culture & Society 17:54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2018.11.001.

- McKercher, B. 2002. “Towards a Classification of Cultural Tourists.” International Journal of Tourism Research 4 (1): 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.346.

- Muilenburg, L. Y., and Z. L. Berge. 2005. “Student Barriers to Online Learning: A Factor Analytic Study.” Distance Education 26 (1): 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910500081269.

- Mura, P., R. Tavakoli, and S. Pahlevan Sharif. 2017. “‘Authentic but Not Too much’: Exploring Perceptions of Authenticity of Virtual Tourism.” Information Technology & Tourism 17 (2): 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-016-0059-y.

- Mura, P., R. Tavakoli, and S. P. Sharif. 2017. “‘Authentic but Not Too much’: Exploring Perceptions of Authenticity of Virtual Tourism.” Information Technology & Tourism 17 (2): 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-016-0059-y.

- Nasser, N. 2003. “Planning for Urban Heritage Places: Reconciling Conservation, Tourism, and Sustainable Development.” Journal of Planning Literature 17 (4): 467–479. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412203017004001.

- Nian, S., H. Zhang, L. Mao, W. Zhao, H. Zhang, Y. Lu, Y. Zhang, and Y. Xu. 2019. “How Outstanding Universal Value, Service Quality and Place Attachment Influences Tourist Intention Towards World Heritage Conservation: A Case Study of Mount Sanqingshan National Park, China.” Sustainability 11 (12): 3321. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123321.

- Olsen, K. 2002. “Authenticity as a Concept in Tourism Research: The Social Organization of the Experience of Authenticity.” Tourist Studies 2 (2): 159–182. https://doi.org/10.1177/146879702761936644.