?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

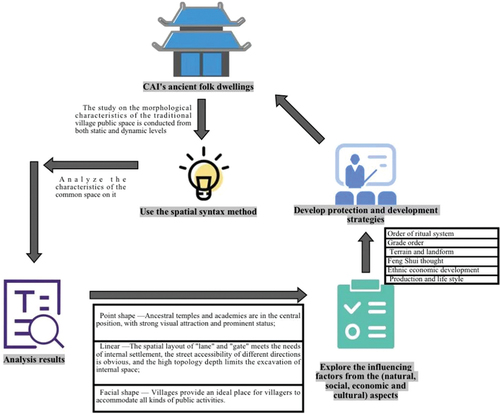

Traditional villages serve as witnesses to history and culture and as the centers of production and life. Studying their spatial characteristics and influencing factors can provide profound insights into their formation, development, and inheritance. Taking CAI’s ancient residential buildings in Zhangli Village, Quanzhou as a case study, this paper utilizes space syntax and abstract topological relations to quantitatively analyze three morphological characteristics of public space: (1) “Ancestral halls” and “Academies” are situated at the core of visual space, representing significant spatial elements within the village, with high visual appeal and status; (2) The spatial layout of “roadways” and “gates” caters to the needs of internal settlements, with their accessibility significantly varying in different directions. However, the high topological depth restricts exploration within the internal space; (3) The village provides residents with spaces for various types of public activities. Furthermore, this paper qualitatively explores the factors influencing the spatial form of Cai’s ancient dwellings from the perspectives of nature, economy, and culture, including topography, hierarchical order, geomancy principles, ethnic economic development, production, and lifestyle. Accordingly, the paper proposes corresponding protection and development strategies, offering a reference for the sustainable development of traditional villages in the future.

1. Introduction

In the realm of social science research, numerous disciplines have been advancing diverse measurement models or mathematical languages to bolster qualitative research. The aim is to more accurately depict the diverse and complex aspects of humanities and social phenomena. This trend is similarly observed in the field of space research, wherein the exploration of mathematical and metrological tools’ applications has emerged as a pivotal research direction in ongoing studies (R. Yang, Xu, and Long Citation2016). Commencing in the 1970s, Western scholars initiated the utilization of mathematical language to scrutinize the correlation between space and various domains such as architecture, society, and cognition. The British architect Bill Hillier played a pioneering role in spatial studies by introducing “Space Syntax” in 1970. In their 1989 publication, “The Social Logic of Space,” Bill Hillier and Julienne Hanson asserted that spatial syntax serves as a method for investigating social behavior and interaction (Hillier and Hanson Citation1989). The structuring and organization of space exert a profound impact on human behavior and interactions, establishing an interactive relationship marked by mutual influence between human activities and spatial organization. Spatial syntax conceptualizes space as a network structure, wherein a point signifies a spatial element within a building or village, and a line denotes the connection between these elements, forming the topology with “Node” and “Link” components (D. Yang et al. Citation2017).This topology undergoes quantitative analysis to investigate the interplay between spatial geometry and cultural and social activities, unveiling the spatial patterns and laws governing human activities and social interactions.

Quanzhou stands as a renowned historical and cultural city in China, serving as the epicenter of southern Fujian culture and a significant birthplace. In the realm of material culture, notable features include the residential culture exemplified by the Imperial Palace Rise, Fanzai House, and Arcade (Guan and Chen Citation2003). In the domain of spiritual and social culture, distinctive characteristics encompass the bloodline family systems, generations of settlement, ethnic identity differentiation, and village clan governance. These cultural attributes result from a combination of historical factors, the natural environment, and the local mode of production and lifestyle. They underscore the unique, diverse, and profound history and culture of southern Fujian. Representative of the official-style grand houses in southern Fujian, the Cai’s ancient residential complex in Zhangli Village stands as a national key cultural relics protection unit. Constructed during the late Qing Dynasty by Cai Qichang, an overseas Chinese in the Philippines, and his son, Cai Zishen (Wang and Luo Citation2003) (See ). Not only does it showcase the exceptional allure of traditional architecture in southern Fujian, but it also holds significant historical and cultural importance. In contemporary times, the conservation and utilization of heritage have garnered the focused attention of numerous experts and scholars. To unveil the interrelationships among material, spiritual, and social cultures within traditional villages in southern Fujian, this paper centers on Cai’s ancient residential complex in Zhangli Village. Employing the quantitative analysis method of spatial syntax, the study scrutinizes the spatial type, spatial structural relationships, and morphological characteristics of the village across the three levels of “points, lines, and surfaces.” The analysis begins with the formation of architectural clusters, exploring the content of activities, form, generation, and other facets to decipher internal rules. The objective is to investigate the reasons behind spatial formation, thereby offering a theoretical foundation for the preservation and revitalization of traditional villages.Specific research steps are as follows:

Firstly, the spatial image research method is used to assess the spatial form of the village by combining field investigation and interview data.

Secondly, Depthmap software is employed to analyze the axis of space syntax, systematically studying the three levels of point, line, and surface, as well as the spatial hierarchy of activity trajectories.

Additionally, the visual field method is utilized to study changes in residents’ visual fields during village activities.

Finally, the results of quantitative analysis are examined, causes are discussed, and protection and renewal strategies are proposed.

2. Literature review

2.1. Research on the spatial form of traditional villages

Traditional villages serve as the foundation for the consolidation and perpetuation of bloodline, connection, and geographical lines. They are vital carriers for the transmission of tangible heritage and intangible genetic information, fostering the cohesion of specific historical memories and distinctive regional cultures. The spatial configuration of a village emerges through the dynamic interplay between its residents and the surrounding regional environment, embodying the historical memory and regional culture inherent to traditional village life. The investigation of traditional village spatial forms has remained a focal point in scholarly research.

Studies on the spatial form of traditional villages predominantly adopt a qualitative discussion approach. For instance, Shawei et al. (Citation2018) endeavored to reconstruct the multi-level spatial system pattern of traditional villages through an examination of their spatial form characteristics. Additionally, Cahyani, Sudikno, and Fauzy (Citation2020) investigated the spatial pattern relationship between the traditional Indonesian villages Kampung Dharam (the main village) and Kampung Rur (the nearest neighboring village), along with the causality within the village. As the use of measurement tools gains prominence, the examination of village spatial patterns has transitioned from qualitative discussions to quantitative analysis. Liu et al. (Citation2022) conducted an analysis of the spatial patterns, types, and growth of 728 traditional villages using ArcGIS and BIM technologies. Their findings revealed distinctive aggregation patterns and identified four spatial spectrum types, offering novel perspectives for urban and rural regeneration efforts. In a similar vein, Jiang et al. (Citation2023) investigated the evolution of spatial morphology in traditional villages by employing the CityEngine parametric platform, digitization, and 3D visualization techniques. In quantitative research, several scholars have concentrated on the spatial distribution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages. Notably, Bian et al. (Citation2022), Li et al. (Citation2022), Jia et al. (Citation2023), and Li et al. (Citation2023) have delved into this aspect. In a related vein, other scholars have directed their attention to the impact of spatial patterns. For instance, Gao et al. (Citation2023) explored the association between spatial environments, tourists’ behavioral characteristics, and stay preferences in traditional villages through kernel density analysis and GPS behavioral tracking methods.

In the realm of spatial research on traditional villages, a prevailing trend involves supporting qualitative research through quantitative analysis using measurement tools. This trend primarily concentrates on two key aspects: the characterization of spatial patterns and their causal analysis, along with the impacts resulting from these spatial patterns.

2.2. Spatial morphology characterization based on spatial syntax

Space syntax is a theory and methodology designed to quantitatively describe the spatial structure of human settlements and examine the relationship between spatial organization and human society Bafna (Citation2003). Utilizing the construction of a spatial topological model, the theory analyzes spatial relations within complex systems, quantitatively assesses spatial forms and unveils the internal socio-cultural logic inherent in material space Hillier and Sheng (Citation2014).

Numerous scholars have employed spatial syntax in the examination of spatial morphological features. Some of these scholars concentrate on quantitative studies of spatial morphological features. For instance, Allah Tafti and Lee (Citation2022) analyzed topological changes in the spatial configurations of Yazd schools over time, utilizing examples from 20 Yazd schools categorized into three groups of historical schools (traditional, transitional, modern, and contemporary). Similarly, Xiao et al. (Citation2023) employed spatial syntax to compare the spatial patterns of seven ethnic villages, unveiling logical connections and formation mechanisms between the overall layout of the villages, residential buildings, and public spaces. Other scholars have concentrated on utilizing spatial syntax to analyze the impact of spatial morphological features. For instance, Miao et al. (Citation2019) quantified road network threat factors, providing insight into the influence of spatial characteristics of the road network on ecological processes. Huang et al. (Citation2020) examined the correlation between park accessibility and street spatial form characteristics, aiming to explore the equity of urban green spaces. Soltani et al. (Citation2022) investigated the impact of street network layout characteristics on student commuting patterns in Shiraz. Additionally, Li and Mao (Citation2022) analyzed the correlation between village spatial form characteristics and industrial structure, while Yang et al. (Citation2023) delved into the impact of urban spatial form on house prices in London.

Spatial syntax has been extensively applied in the examination of spatial morphological features. However, its primary application is found in modern contexts such as schools, modern villages, roads, parks, etc. It predominantly emphasizes the impacts induced by spatial morphology and is less frequently employed in the quantitative study of spatial morphological features in historical areas, such as traditional villages.

3. Study region and research methodology

3.1. Study region

This study selects Zhangzhouliao Natural Village, Zhangli Village, Quanzhou City, Fujian Province, as a case study, with a primary focus on Cai’s ancient residential buildings for quantitative research. This area boasts rich historical and cultural resources, not only reflecting the traditional characteristics of Quanzhou in architectural style and layout but also possessing a profound heritage in traditional lifestyle, social structure, and cultural customs. Through the quantitative study of this area, a deeper understanding of the spatial characteristics, historical changes, and cultural connotations of Cai’s ancient residential buildings can be attained. This knowledge, in turn, enables more targeted planning and decision-making for the protection and inheritance of local traditional culture.

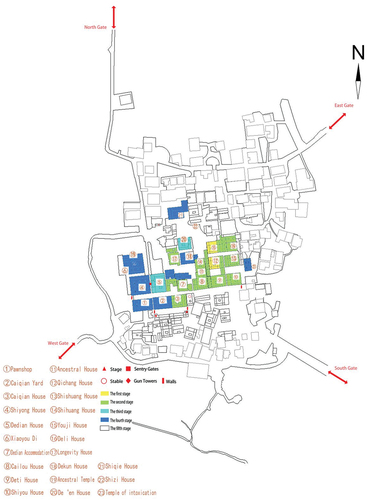

3.1.1. Settlement pattern

Cai’s ancient residential complex was constructed during the Qing Dynasty between Xianfeng and Xuantong, spanning over half a century. Covering a total floor area of approximately 16,300 square meters, the rectangular structure, measuring about two hundred meters in length from east to west and one hundred meters in width from north to south, is organized in five rows and comprises 23 mansions housing over 500 rooms. The construction of the complex followed a specific order: the eastern part was initially built, and subsequent completion progressed gradually from north to south. The eastern segment features 10 large houses systematically arranged and interconnected along a central axis. Additionally, 2-meter wide passageways were preserved for pedestrian movement, fire protection, and drainage, and extending in a north-south direction. The western segment comprises 13 large houses, aligned in an east-to-west orientation. This area can be subdivided into the South Block and the North Block. The southern block extends westward along ShiCheng Avenue, encompassing six large houses that establish a striking east-west axis. The northern block, in turn, can be further categorized into eastern and western parts. The eastern section accommodates five large houses, funded by various sources, sharing similar styles but differing slightly in size and decoration. The western section of the complex encompasses the Cai Ancestral Hall of the Cai Clan and the largest large house, “Xiao you di.” The entirety of the complex showcases a diverse array of historical and architectural features in both the east-west and north-south directions.

3.1.2. Settlement evolution and characterization

The Cai’s ancient residential complex is laid out according to the geomancy thought of “Pipa Cave”. The dwellings were built first and then the outer defenses were built, extending in all directions in a well-organized manner under the premise of the original structure. According to the documentation on the plaques of the main building, the history of the complex can be divided into five well-defined stages of development (see ).

Table 1. Map of the five different phases.

The construction sequence of Cai’s ancient residential complex reflects its distinctive characteristics in two primary aspects. Firstly, the order of construction closely correlates with the annual revenues generated from Cai Zishen’s business activities in the Philippines. The western house within the complex stands out not only for its larger size but also for its more elaborate decorations, serving as an indication of the gradual prosperity of Cai Zishen’s business ventures and the accumulation of considerable wealth. Secondly, an analysis of the architectural composition of Cai’s ancient residential complex, which includes the residential mansion, ancestral temple, ancestral shrine, and academy, reveals a family-centered orientation. Among these structures, both the ancestral hall and the academy building exemplify the core values of the clan, emphasizing principles such as “establishing family temples to promote reverence, creating family schools to educate children, founding a righteous field to support the poor, maintaining the genealogy to bridge familial estrangement,” and upholding ideals of “respect for the collective heritage” and “assisting the young by aiding the elderly.” Thirdly, the distinctive “pawnshop” building within Cai’s ancient residential complex, along with the residential mansion intended for its steward and manager, serves as a reflection of the complex’s construction driven by a well-developed and financially substantial business operation.

3.2. Research method

Spatial syntax finds more extensive application in village space research, and its rationality has received widespread recognition through various case studies and conclusion validations (Dettlaff Citation2014). When analyzing the spatial layouts of traditional dwellings, spatial syntax reveals that these layouts not only accommodate the living needs of the inhabitants but also encompass profound cultural connotations and symbolic values. In the study of spatial syntax, three commonly used methods of analysis include field-of-view analysis, axial analysis, and line segment analysis. These methods apply to various fields such as the countryside, cities, architecture, and gardens. Particularly in traditional villages, lanes serve as not only the support and skeleton of spatial growth but also as crucial carriers of villagers’ activities, observation, experience, and perception of space. In this study, the axial method (including integration degree, comprehensibility, and depth value) and the horizon method (integration degree and depth value of vision) are employed for the cognitive analysis of the spatial form of Cai’s ancient residential buildings in Zhangli Village. By segmenting the roadway into spaces with physical boundaries and illustrating them with axes, the spatial structure is translated into an axial diagram. This method not only analyzes the relationship between natural elements and built environmental elements but also enhances their readability. This paper primarily focuses on the following four morphological variables (Qin et al. Citation2023) (see ).

Table 2. Description of spatial syntactic feature parameters.

3.3. Research steps

The study unfolded through the following steps ():

Spatial image research methods were employed to ascertain the spatial morphology of the village, integrating fieldwork and interview data.

Axial analysis of spatial syntax was conducted using Depthmap software, systematically investigating the three layers of points, lines, and surfaces, as well as the spatial hierarchy concerning activity trajectories.

The field of view method was utilized to examine changes in residents’ perspectives during village activities.

The results of the quantitative analysis were scrutinized, causes were discussed, and conservation and renewal strategies were proposed.

3.3.1. Field research and interview data

The data in this paper is derived from two primary sources: field research and high-definition remote sensing image maps obtained from Google Earth. The field research involved an on-site visit to Zhangli Village, engaging in discussions with villagers and experts, and collecting maps depicting the distribution of existing buildings () along with historical information from the book “Cai’s Ancient Residence: Cai Zishen’s People and Houses.” Simultaneously, high-definition remote sensing image maps from Google Earth were processed using ArcGIS and AutoCAD software to construct the spatial axis model. These datasets were then imported into Depthmap software for spatial syntactic analysis, such as Integration degree, intelligibility, and depth values. etc.

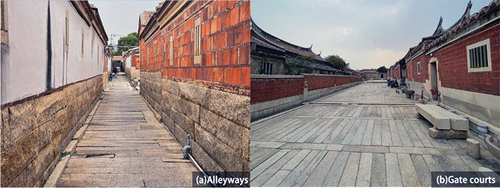

Based on the field research visit, the public space within the Cai’s ancient residential architecture village can be categorized into three components: 1, Point-like space – “the ancestral hall” and “the academy”; 2, Linear space – “the alleyway” and “the gated court”; 3, Faceted spaces – represented by “the theater square” and “village square.” The spatial structure of Cai’s ancient residential building settlement is characterized by points, lines, and surfaces, where each independent architectural unit is interconnected into an organically linked network-type spatial form. In these buildings, the term “point” refers to a large, free-standing house or other structure; the “lines” represent the fire escapes and stone embankment yards that crisscross the single buildings; the “surface” is the square space formed by the combination of points and lines. Topological analysis can provide insights into the implications of humanistic activities in space. The core of village renewal lies in the comprehensive application of big data, making full use of its characteristics such as diversity, reliability, data volume, and value density. By systematically demonstrating the character and orientation of the village, it is possible to ensure the effective protection and full utilization of public space.

3.3.2. Axis analysis

The high-definition remote sensing image map from Google Earth underwent processing using ArcGIS and AutoCAD software. Subsequently, the multi-platform spatial network analysis software, DepthmapX0.50 (developed by Tasos Varoudis), was employed. Based on the Google Earth high-definition remote sensing image map () and the spatial planning map () of Zhangli Village, an AutoCAD spatial axis map was created (). The axial map of Zhangli Village was then saved in DXF format and imported into the Depthmap software to generate corresponding syntactic variable maps, encompassing elemental data such as integration, comprehensibility, and depth values.

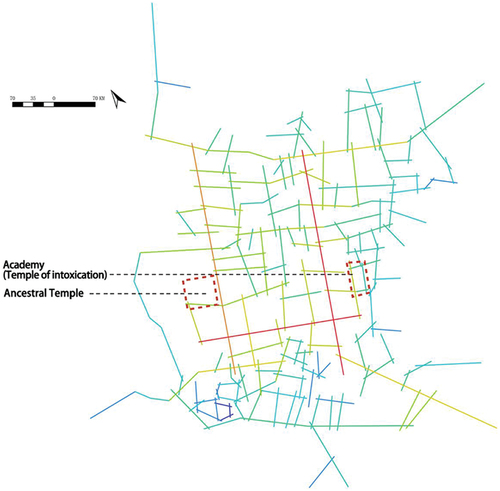

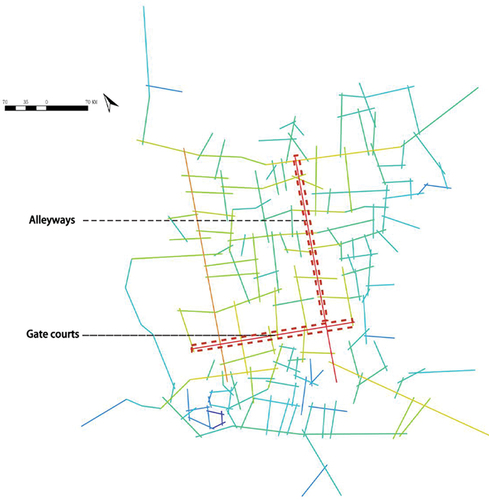

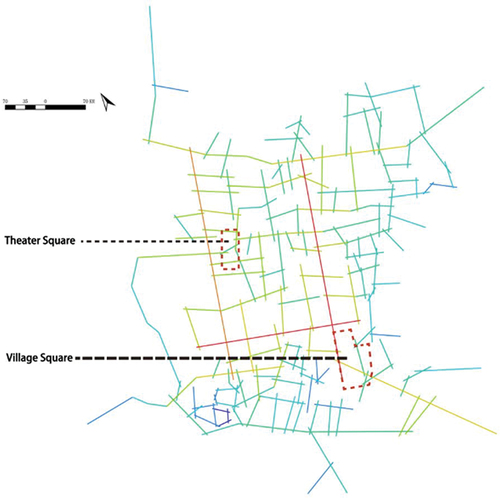

The axial global integration analysis () unveils the overall topological relationship of the village, emphasizing key factors of spatial integration. It further analyzes alley accessibility to delve into the spatial characteristics of the village. The degree of comprehensibility of the village space, from local to overall space, is reflected through the degree of axial comprehensibility (). Enhanced understanding of the topological relationships of specific spatial nodes is achieved through axial depth values (). Additionally, a mathematical model covering point, line, and surface levels was developed ().

Figure 12. Analysis of the depth value of the point-like spatial axis of the ancestral hall and the academy.

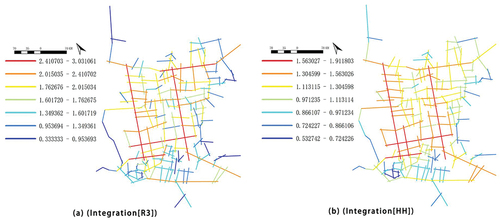

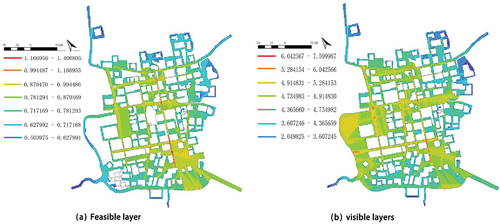

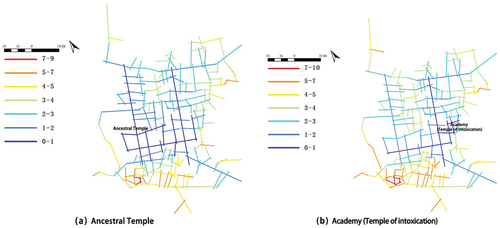

3.3.3. Perspective analysis

Through the analysis of the visual integration degree (), the integration core can be reflected, describing the behavior of residents during village activities and the visual changes in the process. By conducting a comparative analysis of the visual integration degree of the feasible and visible layers, the visual information acquired by residents while traversing the village can be revealed, reflecting the visual-spatial characteristics of the village space. Additionally, the analysis of the depth value of the visual field () can reflect the relationship between the specific spatial arrangement of the line of sight, enhancing the understanding of specific spatial nodes.

Finally, the results presented by the diagram () reveal the changes and visual information of the residents and tourists in the central area and the ancient houses of Cai’s family during activities and analyze the visual relations between specific Spaces and other Spaces.

4. Result and discussion

4.1. Analysis of results

Finally, the results presented by the diagram () reveal the changes and visual information of the residents and tourists in the Topological analysis facilitates an exploration of the significance of humanistic activities in space. To enhance the vitality of the village, enrich spatial functions, realize resource integration and renewal, and meet the various needs of the Cai family within the village, the characteristics of big data, such as diversity, reliability, data volume, and value density, can be comprehensively applied. Quantitative parameters for each elemental object in the spatial system of ancient villages are described to unveil the internal logic of village space. This allows for an intuitive and accurate expression of the configuration characteristics of village space. It aids in the analysis and evaluation of the rationality of the local spatial morphology structure, providing a rationality assessment for the planning scheme of traditional villages. Furthermore, it serves as a scientific basis for the research of spatial morphology in traditional villages. The central area and the ancient houses of Cai’s family during activities and analyze the visual relations between specific Spaces and other Spaces.

4.1.1. Point space – quantitative analysis of the ancestral temple and the academy

Within the western residential area (), the clan temples and the academy are indispensable cultural sites in Cai’s ancient residential complex, serving as typical representatives of point-like spaces. Dotted spaces often function as gathering places for residents to socialize and partake in public activities daily. In rural settlements, these point spaces are crucial locations for villagers to relax, socialize, engage in agricultural activities, and celebrate festivals. They serve as hosts for all aspects of community life, presenting diverse cultural and social experiences.

Syntactic analysis reveals that the clan house is situated at the core of the village enclosure, serving purposes such as clan worship, ancestor honoring, and clan association. The depth value calculation divides the area into no more than 6 steps. Simultaneously, the academy, named “Drunken Scripture Hall”, initially served as a venue for the master’s party and leisure. Over time, it evolved into a study hall for future generations to pursue their studies. The depth value calculation can divide the area into no more than 7 steps. There is good spatial permeability between the ancestral temple the academy and the surrounding spaces, which are connected to the southwestern road of the village enclosure with a topological depth of 1. After quantitative analysis, it can be concluded that the degree of integration of the external spatial perspective where the clan house and the academy are located is 5.85437. This result indicates that the ancestral temple and the academy are some of the most prominent spatial elements in the whole space of the village enclosure, positioned at the core of the visual space with high visual attraction and status. The overall spatial layout is well-designed and coordinated with the entryway, providing interior residents with comfort and convenience that meet their usage needs.

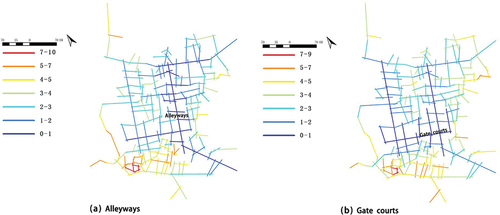

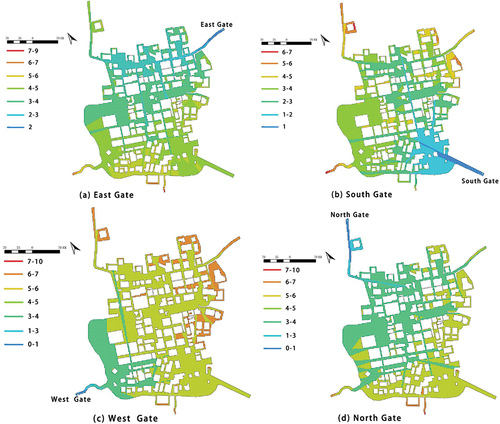

4.1.2. Linear Space - Quantitative Analysis of the “Alleyways and Gate courts” Space

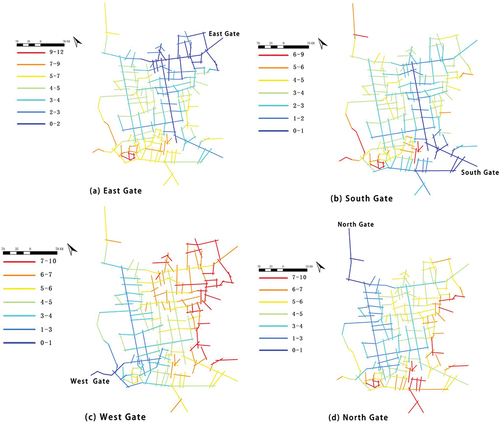

The “alleyways and gate courts” spaces form two public linear areas in the village that connect the entire settlement (). Alleys are defined as public transportation corridors that connect the community to the outside and inside, often serving as secondary transportation routes in the settlement, being narrower and usually extending only to the end. In villages, roads serve as the main transportation arteries, assuming the role of central corridors connecting different areas and facilitating internal and external transportation. Roads play a more prominent role in the internal and external transportation of the settlement compared to lanes. On the other hand, “Gate courts” play the role of an internal low wall in the architecture of Minnan villages, mainly used to address the shortcomings of the internal and external spaces of traditional southern Fujian architecture. They typically play a key role in rituals, festivals, weddings, and funerals, also serving as spaces for processing agricultural products and engaging in social interactions, acting as hubs for information exchange.

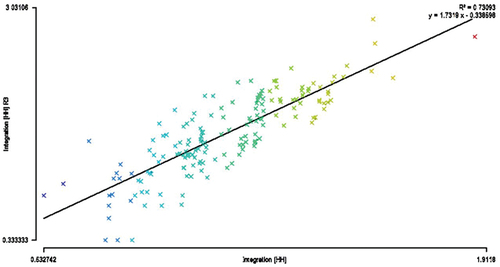

According to the results of syntactic analysis, “alleyways and gate courts” exhibit a high degree of axial and visual integration. Specifically, the alleyway space demonstrates excellent spatial accessibility and visual coherence, with global integration of 1.9118, surpassing the average integration of 1.8761 for the gate courts space. The “alleyway” acts as a divider in the residential group, while the “gate courts” serve as a connecting bridge within the group. Together, they form a closely-knit regional subordination, covering the entire road network of the settlement with a topological depth limited to six steps. This facilitates internal residents’ travel and perception of the surrounding space in all directions. In addition, the degree of comprehensibility reflects whether the overall space of the village is consistent with the local space. Higher comprehensibility indicates that the local spatial structure of the region is conducive to establishing cognition of the overall space, and vice versa. In the Depthmap software, two groups of data – global integration degree and local integration degree – were selected for regression linear analysis (), and the comprehensibility of the axial system was summarized by an XY scatter plot. The Cai’s Ancient Residence Complex shows an obvious correlation between global integration and local axial integration, with a comprehensibility R2 value of 0.73, exceeding the threshold of 0.7. The results indicate a significant correlation between them, suggesting that the overall comprehensibility is relatively high. Based on the results of the syntactic analysis, the following conclusions can be drawn: The spatial layout of “alleyways” and “gate courts” meets the needs of internal settlements, with street accessibility varying significantly in different directions, while the high topological depth restricts the exploration of internal spaces and confers a defensive function.

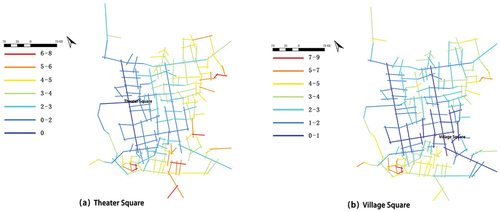

4.1.3. Quantitative spatial analysis of the surface space – “Theater Square” and “Village Square”

Faceted space is typically expressed as a large-scale area, similar to point space (). In villages, there are two main types of faceted spaces, namely the “theater square” and the “village square”. The “theater square” was designed for theatrical performances and is the core area for recreational activities; the “village square”, which serves as both the main entrance to the village and a transitional area between the internal and external environments, is used to fulfill various functions such as security, information transfer, and cultural ceremonies, but is now primarily utilized for visitor parking and selling admission tickets.

Syntactic analysis reveals that “Theater Square” and “Village Square” exhibit multi-level spatial characteristics and are suitable for various types of activities. From a visual perspective, the “Village Square” boasts an average visual integration of 5.7629, attracting visually-oriented participants, and it demonstrates excellent spatial accessibility throughout the village with an axial integration of 1.9118, aiding in attracting the public to gather. In contrast, “Theater Square” has a spatial axial integration of 1.11053, making it more suitable for professional activities. The analysis of the depth values of the four entrances through the spatial remapping core of the entrances reveals significant results: the lines of sight between the four entrances and the “theater plaza” and the “village plaza” need to undergo several topological depth changes to ensure visibility and avoid awkwardness. In particular, as the main entrance to the village, the East Gate provides maximum visual depth with only a small change in topological depth to reach the core village area, ensuring optimum visual accessibility. Through quantitative analysis of spatial syntax, it can be concluded that the village provides ideal spaces for villagers to engage in various types of public activities. Differences in alignment and accessibility of different roads and large values of topological depth of the lanes add to the complexity of spatial exploration. This highlights the characteristics of the Cai’s ancient residential complex, which include defensiveness, orderliness, and self-sufficiency in its indigenous character. At the same time, it also emphasizes the importance of the family concept and the sense of clan, aligning with the traditional Chinese lifestyle of “living in a colony”.

4.2. Discussion

Utilizing the theory of spatial syntax for an in-depth analysis of traditional village space and exploring strategies for the protection and development of ancient village spatial forms is not only an innovation in traditional planning technology but also a departure from the conventional mode of protecting and developing villages. It represents a “spatial syntax” protection and development approach rooted in the influencing factors of village spatial forms and development laws. This approach is beneficial for safeguarding traditional villages from a multi-scalar, multi-layered, and multi-directional perspective, shifting the focus away from the local, static, and surface aspects of architectural and spatial forms.

In addition, spatial structural patterns are significantly influenced by human spatial awareness, which, in turn, dictates human spatial behavior. Since the theory of spatial syntax is objective in its analysis of spatial entities and examines the relationship between the overall system space and local spatial nodes through a rational lens, it tends to overlook the subjective spatial awareness of individuals. Previous research on traditional villages primarily centers on historical remnants, with limited exploration of spatial patterns from the standpoint of public space cognition (Ayşegül Citation2020). This paper delves into the factors shaping the spatial characteristics of Zhangli Village, considering the natural environment, humanistic environment, and social development perspectives. Furthermore, it proposes corresponding conservation and renewal strategies to address the existing issues in the village’s public space.

4.2.1. Analysis of factors influencing spatial characteristics

4.2.1.1. Topography and geomorphology

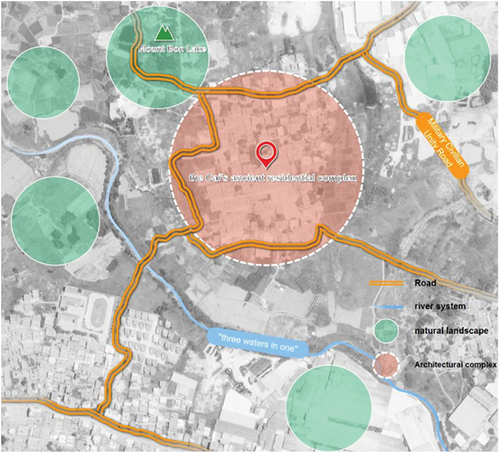

The Cai’s Ancient Residence Complex is situated in the south-central part of the city of Nan’an, featuring terrain that gradually descends from high in the northwest to low in the southeast (). The village is positioned on a flat expanse, benefiting from the geographical advantages of being “backed by the mountain, surrounded by water, facing the sun,” aligning with the southern subtropical oceanic monsoon climate. Bounded by northwestern mountain ranges, the prominent peak, Mount Bon Lake, towers over 500 meters, providing a majestic backdrop to the complex. The twin streams in the southwest originate from Banghu Mountain, while the other two streams in the southeast of the ancient residential complex converge in the southeast corner, forming a water system structure known as “three waters in one”. The entire settlement is situated on flat terrain, enveloped by water currents, with mountains serving as a natural protective barrier. These topographical features shield the settlements from natural disasters and enhance access to water resources for agricultural production. The natural environment, embraced by mountains and water, fosters cultural and social prosperity, aligning with the traditional Chinese concept of living. This creates an ideal living environment designed to “hide the wind and gather the air”, meeting residents’ desires for good fortune and avoidance of misfortune.

4.2.1.2. Geomancy Thought

According to geomancy principles, houses are traditionally designed to avoid “direct exposure” to protect wealth. In northern traditional architecture, a common approach involves incorporating a “wall” design, where the outer door faces a protective wall, creating a meandering corridor that provides a sense of “lit. hold a pipa and half cover one’s face” upon entry. However, the hot and humid climate of the southern region doesn’t lend itself well to such a design, as it would impede ventilation. To address this issue, Southern Fujian residents ingeniously developed a spacious “Cheng” area in front of the main entrance of the “Big House,” using stones or cement for paving. They enclosed three sides of the main entrance with a low wall, treating this open space as a “private territory.” This design ensures that outsiders don’t immediately enter the interior, preserving the privacy of the owner’s home. Furthermore, some families, emphasizing geomancy, construct a “geomancy pond” in front of Dao Cheng to accumulate wealth. This pond serves practical purposes as well, such as raising fish and ducks.

4.2.1.3. Hierarchical Order

The spatial design of Cai’s ancient residential complex is rooted in traditional Chinese family organization and hierarchical concepts, emphasizing the principles of “the center of the house is respected” and “the order of elders and children”. The layout design, including the front hall and the back house, embodies the features of the traditional Chinese family structure. The front hall and the back room are designated for specific purposes, with the hall serving ritual functions, the main house serving as the owner’s living quarters, and the guard house typically used for servants’ quarters or miscellaneous storage. The elevated and narrow patio in Cai’s ancient residential complex serves various purposes, encompassing light exposure, ventilation, shading, drainage, and space for garden planting. The rock gate courts, on the other hand, functioned as areas for family members to rest, move around, and host celebrations such as weddings. The allocation of rooms within the Cai’s ancient houses adheres to the age order of the brothers, ensuring a relatively balanced distribution of houses while respecting kinship relationships and population needs. When parents cohabit with their adult children, the order of division within the main house prioritizes the eldest, usually placing them in the third or remaining room, while younger individuals are more likely to be assigned auxiliary rooms. This distribution strategy maintains family ties, upholds traditional culture, and reflects ethical and ceremonial concepts deeply rooted in tradition Qiu et al (Citation2022).

4.2.1.4. Economic Development of the Community

Cai’s Ancient Residence was established by Cai Qichang and Cai Zishen in Phuyang, with its construction intricately tied to Cai Zishen’s business ventures in the Philippines. The substantial commercial wealth amassed by Cai Zishen over a lifetime of endeavors provided the economic foundation for the phased construction of the complex. The incremental expansion of the Cai Mansion from east to west, along with its construction process, serves as a reflection of the economic progression of the Cai Clan. Among the 10 large houses on the east side, the Qichang house and You house were the earliest to be built (around 1867, the year of Ding Mao during the Tongzhi reign). Subsequently, the Shiyou house, DeTi house, and Cailou house were successively added at the south end. This not only increased the spatial dimension but also enriched the cultural and social value of the complex, establishing it as a significant site for clan activities and ceremonies. With the gradual prosperity of Cai’s business activities in the Philippines, the Western Alley not only became larger but also more elaborately decorated. On the west side, CaiQian Bekan and CaiQian house, serving as a guest house and Cai Senior’s private residence, respectively, were constructed between 1902 and 1903. Additionally, buildings on the north side, such as DeDian house, DeDian study room, and Shiyong house, signify the family’s focus on expansion and education following their economic success. The construction process of the Cai Mansion not only showcases the economic strength of the Cai family but also reflects their profound cultural heritage and forward-thinking considerations for future development.

4.2.1.5. Production and Lifestyle

The Cai’s Ancient Residence Complex is a unique community that preserves the traditional residential architecture and production methods of the Ming and Qing Dynasties. It encompasses essential public facilities like a shared dining hall, a firewood processing area, and a peanut roasting workshop. Orchards are situated at the north and south ends, while fields are spread in the east, south, and west directions. The inhabitants primarily cultivate crops such as rice, groundnuts, and longan trees, showcasing proficiency in utilizing water resources to enhance crop yields through water conservancy facilities. Moreover, they engage in operating oil mills and cane sugar mills to supplement their family income. Architecturally, Cai’s ancient residence emphasizes mutual family support and the cultivation of close community relationships. In terms of ecological construction, the lifestyle of the Cai’s ancient dwellings not only aligns with modern values but also holds profound modern social significance, encompassing ecological, social, and economic aspects. The value of this lifestyle is incalculable, reflecting the cohesion and centripetal force of the Cai family.

4.2.2. Zhangli Village Conservation and Renewal Strategy

The novel perspective of spatial syntax contributes to a deeper understanding of the spatial evolution characteristics of traditional villages. This understanding enables designers to integrate users’ perceptions and interactions with the spatial environment more effectively. The study provides planners with a basis and operational recommendations for the preservation and renewal of Zhangli Village, aiming to continue the historical heritage, maintain the spatial pattern, and sustain the vitality of the rural spiritual space. Future work should address the following points:

Strengthen the influence of the core space and improve the integration of the global space;

Highlighting distinctive spatial nodes;

Enhance the accessibility of the public space, to increase the degree of integration accordingly;

deeply excavate the historical and cultural value of Zhangli Village, and lay a good foundation for the stability of the spatial pattern of the ancient village;

Appropriate commercial tourism development to revitalize the economic development of Zhangli Village.

4.2.3. Research limitations

Despite reading a considerable number of references and conducting a systematic investigation into the spatial morphology characteristics of Zhangli Village, this paper has some limitations. Firstly, the village axial map used in the axial analysis relies on topographic information combined with Google Earth and aerial photographs, manually drawn using AutoCAD software. Consequently, the experimental results may inherently carry certain artificial biases, influencing the ultimate conclusions. Secondly, as most of the space explored by syntax exists in the two-dimensional dimension, while cognition extends beyond the two-dimensional realm, the specific methods for implementing spatial syntax in the three-dimensional direction require further exploration.

5. Conclusions

Traditional villages in southern Fujian represent distinctive communities shaped by a historical period, intimately connected to traditional culture, socio-economy, and lifestyle. This study employs spatial syntax to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the morphological characteristics of the public space within Cai’s ancient residential complex in Zhangli Village. The findings reveal exceptional syntactic performance in this village. Material entities within the ancient village encompass point-like spaces (ancestral halls and academies), line-like spaces (alleyways and gate courts), and surface-like spaces (theater square and village square). Coupled with quantitative analysis, the following conclusions can be drawn:

The ancestral hall and the academy stand out as prominent spatial elements within the entire village enclosure space, situated at the core of the visual space. The overall spatial layout is meticulously designed, boasting a high degree of visual appeal and status.

The spatial arrangement of “alleyways” and “gate courts” caters to the needs of internal settlements, featuring varying accessibility in different directions. The elevated topological depth limits the exploration of the internal space, imparting a defensive function.

The village offers optimal locations for villagers to engage in diverse public activities. Disparities in the alignment and accessibility of different roads, coupled with substantial topological depth values of the lanes, contribute to the intricacies of spatial exploration.

Additionally, this paper comprehensively explores the factors contributing to the formation of the village from five perspectives: topography and landscape, hierarchical order, geomancy thought, economic development of the community, and production and lifestyle. Collectively, these elements influence the morphology and spatial performance of Zhangli Village.

Applying the novel perspective of spatial syntax to the study of the spatial evolution characteristics of traditional villages helps to perpetuate historical heritage, maintain spatial patterns, revitalize traditional culture, and sustain rural spaces. This study not only deepens the understanding of traditional villages but also offers practical guidelines for actual planning and renewal. In sum, this research provides a new perspective and methodology for the spatial study of traditional villages, serving as a positive revelation for the future development and conservation of villages.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yang Zhao

Yang Zhao, male, Associate professor, Master’s supervisor, Secretary of the Party Branch of the faculty “double leader”, Quanzhou high level talents, visiting scholar of the Department of Landscape Architecture, College of Creative Design and Art, Donghai University, Taiwan. He is currently the chairman of the Trade union of the Academy of Fine Arts, the secretary of the Party branch of the Department of Design, and the deputy director of t he Department of Art Design. He also serves as deputy director of Environmental Design Art Committee of Fujian Artists Association, evaluation expert of Degree and Graduate Education Center of Ministry of Education, expert consultant of CIID Interior Archi tects Center, Vice President of Quanzhou Interior Designers Association, expert of Architectural Decoration Branch of Quanzhou Construction Association, expert of Quanzhou Creative Industry Association, etc.

Zihui Luo

Luo Zihui, female, born in 1997, majored in art design at the School of Fine Arts and Design, China Quanzhou Normal University, Master degree, research direction is environmental design.

Kai Huang

Kai Huang, male, born in 1999, majoring in art design at the College of Fine Arts, Huaq iao University of China, Master degree, research direction is environmental design.

References

- Allah Tafti, F., and J. H. Lee. 2022. “Examining Variance, Flexibility, and Centrality in the Spatial Configurations of Yazd Schools: A Longitudinal Analysis.” Buildings 12 (12): 2080. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings12122080.

- Ayşegül, K. A. Y. A. 2020. “Interpreting Vernacular Settlements Using the Spatial Behavior Concept.” Gazi University Journal of Science 33 (2): 297–316. https://doi.org/10.35378/gujs.559548.

- Bafna, S. 2003. “Space Syntax: A Brief Introduction to Its Logic and Analytical Techniques.” Environment and Behavior 35 (1): 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916502238863.

- Bian, J., W. Chen, and J. Zeng. 2022. “Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in China.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19 (8): 4627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084627.

- Cahyani, D. I. A. H., A. Sudikno, and B. Fauzy. 2020. “Examining the Spatial Pattern in Indonesia’s Villages for the Globalization Mechanism of Survival.” Journal of Engineering Science and Technology 15:30–38.

- Dettlaff, W. 2014. “Space syntax analysis–methodology of understanding the space.” PhD Interdisciplinary Journal 1:283–291.

- Gao, X., Z. Li, and X. Sun. 2023. “Relevance Between Tourist Behavior and the Spatial Environment in Huizhou Traditional Villages—A Case Study of Pingshan Village, Yi County, China.” Sustainability 15 (6): 5016. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15065016.

- Guan, R. M., and L. Chen. 2003. “The History of Quanzhou and the Interpretation of its Geographical Names.” Central China Architecture 21 (1): 79–80.

- Hillier, B., and J. Hanson. 1989. The Social Logic of Space. Chicago, IL: Locke Science Publishing Company, lnc.

- Hillier, B., and Q. Sheng. 2014. “The Now and Future of Space Syntax.” Architectural Journal 8:60–65.

- Huang, B. X., S. C. Chiou, and W. Y. Li. 2020. “Accessibility and Street Network Characteristics of Urban Public Facility Spaces: Equity Research on Parks in Fuzhou City Based on GIS and Space Syntax Model.” Sustainability 12 (9): 3618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093618.

- Jia, A., X. Liang, X. Wen, X. Yun, L. Ren, and Y. Yun. 2023. “GIS-Based Analysis of the Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in Hebei Province, China.” Sustainability 15 (11): 9089. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15119089.

- Jiang, Y., N. Li, and Z. Wang. 2023. “Parametric Reconstruction of Traditional Village Morphology Based on the Space Gene Perspective—The Case Study of Xiaoxi Village in Western Hunan, China.” Sustainability 15 (3): 2088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032088.

- Li, T., C. Li, R. Zhang, Z. Cong, and Y. Mao. 2023. “Spatial Heterogeneity and Influence Factors of Traditional Villages in the Wuling Mountain Area, Hunan Province, China Based on Multiscale Geographically Weighted Regression.” Buildings 13 (2): 294. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13020294.

- Li, R., and L. Mao. 2022. “Spatial Characteristics of Suburban Villages Based on Spatial Syntax.” Sustainability 14 (21): 14195. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114195.

- Liu, X., Y. Li, Y. Wu, and C. Li. 2022. “The Spatial Pedigree in Traditional Villages Under the Perspective of Urban Regeneration—Taking 728 Villages in Jiangnan Region, China as Cases.” The Land 11 (9): 1561. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11091561.

- Li, B., J. Wang, and Y. Jin. 2022. “Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Traditional Villages and Influence Factors Thereof in Hilly and Gully Areas of Northern Shaanxi.” Sustainability 14 (22): 15327. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142215327.

- Miao, Z., L. Pan, Q. Wang, P. Chen, C. Yan, and L. Liu. 2019. “Research on Urban Ecological Network Under the Threat of Road Networks—A Case Study of Wuhan.” ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 8 (8): 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi8080342.

- Qin, X., X. Du, Y. Wang, and L. Liu. 2023. “Spatial Evolution Analysis and Spatial Optimization Strategy of Rural Tourism Based on Spatial Syntax Model—A Case Study of Matao Village in Shandong Province, China.” The Land 12 (2): 317. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12020317.

- Qiu, Z., Y. Wang, L. Bao, B. Yun, and J. Lu. 2022. “Sustainability of Chinese Village Development in a New Perspective: Planning Principle of Rural Public Service Facilities Based on “Function-Space.” Synergistic Mechanism Sustainability 14 (14): 8544. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148544.

- Shawei, Z., W. Dinghang, and Y. Zhong. 2018. “Research on Traditional Village Based on Spatial Pattern System in Guangdong Province.” 2018 2nd International Workshop on Renewable Energy and Development (lWRED 2018). IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Vol. 153, No. 5. IOP Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/153/5/052039.

- Soltani, A., M. Javadpoor, F. Shams, and M. Mehdizadeh. 2022. “Street Network Morphology and Active Mobility to School: Applying Space Syntax Methodology in Shiraz, Iran.” Journal of Transport & Health 27:101493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2022.101493.

- Turner, A. 2003. “Analysing the Visual Dynamics of Spatial Morphology.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 30 (5): 657–676. https://doi.org/10.1068/b12962.

- Wang, L., and Q. Luo. 2003. “Cai’s Ancient Folk Dwelling Compounds.” Journal of Northern Jiaotong University 1:87–93.

- Xiao, H., C. Xue, J. Yu, C. Yu, and G. Peng. 2023. “Spatial Morphological Characteristics of Ethnic Villages in the Dadu River Basin, a Sino-Tibetan Area of Sichuan, China.” The Land 12 (9): 1662. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12091662.

- Yang, S., K. Krenz, W. Qiu, and W. Li. 2023. “The Role of Subjective Perceptions and Objective Measurements of the Urban Environment in Explaining House Prices in Greater London: A Multi-Scale Urban Morphology Analysis.” ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 12 (6): 249. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi12060249.

- Yang, R., Q. Xu, and H. Long. 2016. “Spatial Distribution Characteristics and Optimized Reconstruction Analysis of China’s Rural Settlements During the Process of Rapid Urbanization.” Journal of Rural Studies 47:413–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.05.013.

- Yang, D., R. Zhang, D. Fan, and Z. Chen. 2017. “Quantitative Study of Haikou Meishe Village on the Changes of Traditional Settlement Pattern.” Journal of Xi’an University of Architecture & Technology (Natural Science Edition) 49 (6): 868–874.