ABSTRACT

Under the dual pressures of repeated impacts from the pandemic and global economic downturn, the deterioration trend of social security is evident. In 2021 and 2022, the United Nations consecutively emphasized the centrality of reducing and preventing recidivism, aiming to foster research and practices in crime prevention. Developing and applying crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) theory provides a viable approach to reducing crime. Utilizing the relevant literature on environmental design for crime prevention from the Web of Science Core Collection database and employing Cite Space software, this study systematically delineates the research trajectory of crime prevention through environmental design. The research uses bibliometrics and literature analysis methods to identify research hotspots and trends in the field. Building upon these findings, the study proposes that future research in CPTED should systematically explore the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of the impact of urban built and social environments on crime. It also advocates for in-depth investigations into the long-term causal relationship between environmental features and crime under the framework of CPTED. The study emphasizes the exploration of the local applicability of CPTED theory under conditions of multiculturalism and regional differences. This helps to propose crime prevention strategies for new social issues and crime patterns, thereby providing strong support for the sustainable development of cities.

1. Introduction

A secure built environment is not only a prerequisite for the stable development of society but also an essential requirement for urban sustainability (Mao, Cheng, and Zheng Citation2022). At the United Nations Sustainable Development Summit in September 2015, the international community adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, delineating 17 sustainable development goals. Goal 11 aims to establish inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable cities and human settlements (Yan et al. Citation2023). In 2021, humanity officially entered the crucial decade for achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Luo Citation2021) In March 2021, the 14th United Nations Crime Congress explicitly highlighted crime prevention and reduction as a critical agenda. In 2022, the United Nations Expert Group on “Preventing and Reducing Reoffending” discussed the draft of “Key Elements Checklist for Reducing Reoffending Demonstration Strategies,” aiming to provide practical guidance to criminal justice systems worldwide. Therefore, to promote sustainable urban development, measures such as legal and regulatory deterrence, public safety prevention, and environmental planning and design can be implemented to protect humanity from the threat of crime. The urban environment is closely related to criminal behavior and a sense of security, such as criminal activities and environmental security, which are influenced by physical and social environmental factors such as natural site monitoring, nighttime lighting levels, management and maintenance, and land use (Foster, Giles-Corti, and Knuiman Citation2011; F. E. Kuo, Bacaicoa, and Sullivan Citation1998; Stucky and Ottensmann Citation2009a; Wilcox, Madensen, and Tillyer Citation2007). This indicates that urban environmental planning and design can effectively suppress criminal behavior and enhance environmental security (Y. Zhang and Hua Citation2020).

Crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) theory originated from rational offender theory, behavioral geography, and routine activity theory. This theory asserts that the sensible design and effective utilization of physical spaces can reduce the occurrence of criminal behavior and the fear of crime. CPTED, integrating theories from urban design, psychology, and criminology, is a comprehensive and practical crime prevention method. It has gradually become a crucial strategy globally to address urban crime issues. It has received support from governments and relevant institutions in North America, Australia, Asia, and South Africa (P. Cozens and Love Citation2015). For instance, in the 1990s, several local governments in the United States, including Florida and Arizona, incorporated CPTED principles into land-use regulations and related design ordinances to address urban crime issues (R. I. Atlas and Fitzgerald Citation2008). In 2001, New South Wales in Australia introduced CPTED guidelines to ensure that proposed building environment developments and reconstructions reflect fundamental CPTED principles (Clancey Citation2011). In 2016, the Korean Institute of Architecture and Urban Studies established a CPTED research center to provide consultation, evaluation, and optimization services for national and local CPTED projects, promoting the dissemination and implementation of local CPTED projects (D. K. Huang and Lai Citation2023).In 2001, the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research in South Africa passed the “Design Safer Places: A Handbook for Planning and Designing Crime Prevention” to propose planning strategies such as land-use development and regional linkage development for large vacant lots in urban areas, aiming to improve the urban environment and reduce crime (Mao, Cheng, and Zheng Citation2022). In addition, the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) advocates and supports the adoption of crime prevention through environmental design to enhance urban safety (Clos Citation2011). The support of national policies and the elevation of public awareness has gradually propelled crime prevention through environmental design into a mainstream design concept, stimulating extensive research within the academic community in the field of crime prevention through environmental design. In the paper “Third Generation CPTED The 4 S Principles for Liveability”, published by Mateja Mat the ICA (International CPTED Association) International Conference on the theme of “Why CPTED? Creating a Livable Environment” in 2021, it was pointed out that the third generation CPTED theory can provide practical strategies for solving current urbanization problems (M. Mateja and Saville Citation2021). In the paper “SAFE CITIES: Homogeneous vs. Heterogeneous Communities Role of Culture & Socioeconomics in CPTED”, presented by Manjari KK at the ICA International Conference on “Safe Cities Created by People” in 2023, it was pointed out that the third-generation CPTED theory with sustainable development as its core needs to integrate socio-economic perspectives fully (Manjari and I. Director, and India Citation2023). Under the dual pressures of repeated impacts from the pandemic and global economic downturn, the deterioration trend of social security is evident. The crime rates in developed countries such as the United States, France, and Japan show an upward trend. In 2022, the number of homicides in the United States increased by 39% compared to 2019, with severe violent attacks and robberies rising by 4% and 19%, respectively (https://counciloncj.org/pandemic-social-unrest-and-crime-in-u-s-cities-year-end-2022-update/) he number of serious crimes such as murder, robbery, and burglary in New York City increased by 20.4% year-on-year (https://news.ifeng.com/c/8NP84wPk0LZ). In 2023, the number of hate crimes in the United States reached a new high, with multiple cities breaking decades of records (https://news.yunnan.cn/system/2024/01/06/032899922.shtml). The number of crimes in France increased significantly in 2022, with a large increase in burglary (https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1756676836872403755&wfr=spider&for=pc). In 2023, the number of murder cases in France reached 1010, an increase of 5% from the previous year (https://www.163.com/dy/article/IPR7IUCS0514BIJT.html). In 2022, criminal cases in Japan increased for the first time in 20 years, an increase of 5.9% compared to 2021 (http://www.livejapan.cn/static/content/SY/TT/3February2023/1071022887613370368.html). In 2023, the number of criminal cases in Japan exceeded 700,000, an increase of 17% from the previous year and a continuous increase for two consecutive years, reflecting a deterioration in the country’s public security situation (https://www.163.com/dy/article/IU7LEPNF0534P59R.html). These cases often occur in public activity spaces with insufficient surveillance and poor maintenance and management. As the world’s largest developing country, although the crime rate shows a downward trend, China’s investment in maintaining social security is increasing. China’s public safety expenditure reached 196.464 billion yuan in 2022 and 224.558 billion yuan in 2023, a year-on-year increase of 6.4% (https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2023–03/15/content_5746960.htm?eqid=923858d8000d016e000000026462e2d1). This indicates that China still faces challenges in maintaining social stability and public security, and the social security situation remains severe. On 8 July 2022, in Nara Prefecture, Japan, the incident of Shinzo Abe being fatally shot occurred at the Kintetsu “Yamato Saidaiji Station”. This public space is prone to gathering crowds, aligning with vital spatial characteristics outlined in CPTED, including natural surveillance and controlled access. The perpetrator had conducted a prior survey of the surroundings, strategically selecting a concealed vantage point for the shooting.

New types of criminal problems, such as cybercrime, social media crime, and misuse of the Internet of Things, are constantly emerging (Han Citation2018; Peng and Fu Citation2023; Wang et al. Citation2023). The Crime-Field theory suggests effective cybercrime prevention can be achieved through macro-level crime opportunity controls and micro-level rational choice deterrence, effectively preventing cybercriminal behaviour (Tu and Li Citation2023). The crime-field theory connects theories of crime causation and crime control, sharing a similar theoretical logic with environmental criminology’s advocacy for crime prevention through environmental design. The theory of crime prevention through environmental design also applies to addressing new types of crime. As such, the research perspective of crime prevention through environmental design needs to continuously adjust and expand to more comprehensively and flexibly adapt to environmental changes, thus effectively addressing novel crime problems. In this context, to broaden the academic scope and depth of crime prevention through environmental design, this study employs bibliometric analysis based on the Web of Science Core Collection (WOSCC) database. In conjunction with traditional literature reading and CiteSpace knowledge mapping software, the research on crime prevention through environmental design is systematically reviewed, clarifying its research progress, analyzing frontier hotspots, and exploring potential development trends. This effort aims to assist researchers in tracking the latest developments and trends in crime prevention through environmental design, providing a reference for academic research and practical decision-making, and promoting the refinement of knowledge development and decision-making practices in crime prevention through environmental design.

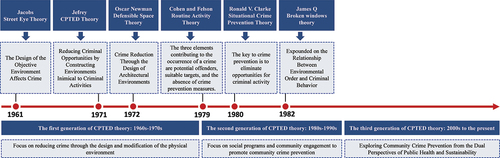

2. From street eye theory to the third generation of CPTED theory: the evolution of crime prevention through environmental design theory

As shown in the Environmental Design Prevention of Criminal Theory Development Process Map (), in 1961, Jane Jacobs coupled the crime phenomenon with the spatial environment and proposed the street eye theory (Jacobs Citation1961). Based on this theory, Jeffery first proposed the CPTED theory in 1971 and pointed out that effective environmental design can prevent criminal behaviour (Jeffery Citation1971). In 1972, Oscar Newman proposed the defensible space theory, aiming to reduce crime by designing and transforming the building environment (Newman Citation1972). In 1979, Cohen and Felson proposed the theory of everyday behaviour. They pointed out that the three necessary elements of criminal behaviour are potential criminals, probable targets, and a lack of strong crime supervisors (Cohen and Felson Citation1979). Based on the above theory, the basic framework of the first-generation CPTED theory has been initially formed. Its core six elements include territoriality, surveillance, access control, target hardening, Image/maintenance and activity support. In 1980, Ronald V. Clarke proposed the situational crime prevention theory, which focuses on reducing crime opportunities by changing specific situational conditions (Clarke Citation1997). The broken window theory proposed by James Q. Wilson in (Citation1982) added a new perspective on environmental management to CPTED(Wilson and Kelling Citation1982). Afterwards, Greg Saville and Gerry Cleveland further pointed out that improving community safety should focus on constructing the social and emotional environment of residents in the community. As a result, the second-generation CPTED theory added four key elements: social cohesion, community connectivity, community culture, and threshold capacity (Saville and Cleveland Citation2008). Some scholars have re-examined the theoretical research on environmental design crime prevention in recent years, advocating that CPTED should combine public health and sustainability. Mihinjac proposed the third-generation CPTED theory based on the core concept of community livability (Mihinjac and Saville Citation2019). Saville introduces environmental, social, economic, and public health sustainability, enriching the theoretical connotation of the third-generation CPTED (Mihinjac and Saville Citation2019). Developing the third-generation CPTED theory will lead to more in-depth and comprehensive research on constructing safe, healthy, livable community environments.

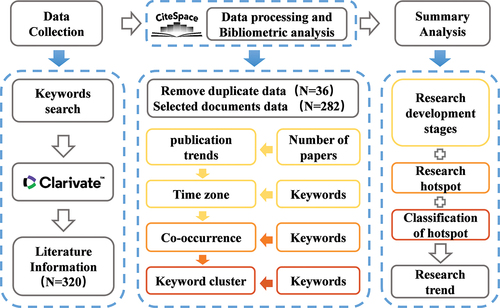

3. Environmental design crime prevention research methods and data acquisition process: based on bibliometric method

3.1. Research methods

The literature metering method is an objective and quantitative method that depends on mathematical and statistical methods to analyze and evaluate the characteristics of the literature. It is suitable for large-scale literature data analysis. Commonly used analysis software includes Cite Space and Vosviewer (T. Guo et al. Citation2017). Cite Space can present the results of joint word analysis, standard analysis, and social network analysis in the form of visualization and intuitively help scholars interpret the critical path and inflection point of knowledge in specific knowledge areas (Chen et al. Citation2015). However, certain disadvantages exist, such as failing to reflect the complete research system fully. The traditional literature analysis method emphasizes in-depth understanding and interpretation of the content of the literature. Qualitative analysis systematically evaluates and sorts out the theme, theory, viewpoints, techniques, etc (X. Q. Liu et al. Citation2021). Therefore, to objectively and comprehensively analyze the research context and development trend of environmental design to prevent crimes, the literature measurement and traditional literature analysis methods are used to conduct an inquiry.

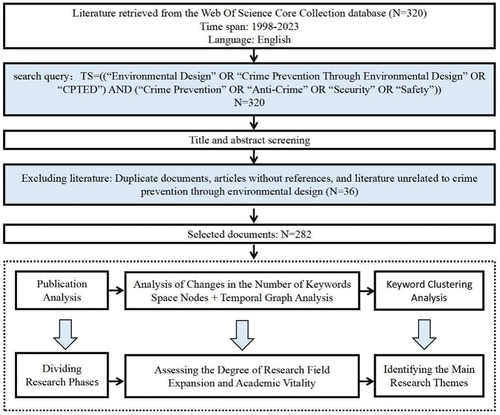

3.2. Data acquisition

The entire process, from literature retrieval to data analysis, is delineated into three sequential steps: firstly, obtaining literature from the WOSCC database; secondly, excluding duplicate and irrelevant literature about crime prevention through environmental design based on title and abstract content; and finally, utilizing the scientific knowledge mapping software, Cite Space, for visual analysis. The research design outline is illustrated in . The search query is formulated as TS=((“Environmental Design” OR “crime prevention through environmental design” OR “CPTED”) AND (“Crime Prevention” OR “Anti-Crime” OR“Security” OR “Safety”)), with the search encompassing “Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI-EXPANDED),” “Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI),” “Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (CPCI-S),” and “Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Social Science & Humanities (CPCI-SSH)” and restricted to English language. The initial appearance of literature focusing on crime prevention through environmental design dates back to 1998, leading to the restriction of the literature retrieval timeframe from 1 January 1998, to 30 December 2023. A total of 320 documents were retrieved, and after deduplication, organization, and screening, 282 valid documents were identified. The bibliographic information includes authorship, title, source publication, research direction, and references cited.

4. Development line analysis of environmental design crime prevention research: based on the number of published papers statistics and keywords time zone view

4.1. Analysis of publication trends

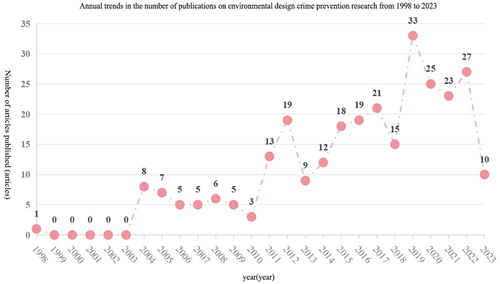

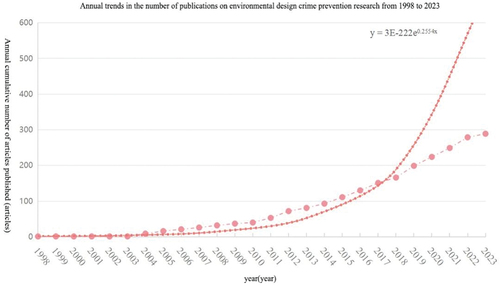

The volume of publications is a crucial bibliometric indicator that reflects the evolving trajectory of attention within a specific research field (Qiu, Shen, and Song Citation2019). Following Narymov and Freudz’s literature logic growth model (Li, Wang, and Ning Citation2016), bibliometric methods were applied. Through a yearly cumulative statistical analysis of publications in environmental design for crime prevention from 1998 to 2023, data was subjected to curve fitting using the least squares method. This process yielded a graphical representation of the cumulative publication trend over the years in the form of a curve chart. As shown in , the expression for the growth curve relationship was obtained through curve fitting analysis: y = 3E-222e0.2554x, where y represents the cumulative volume of published literature, and x represents the year. The cumulative publication volume in environmental design for crime prevention exhibits an exponential trend over the years, with no apparent inflection point indicating a downturn in the publication curve. This suggests that the literature output on environmental design for crime prevention is expected to continue growing, indicating widespread research potential and room for development in this area.

Figure 3. Trend fitting curve chart of the number of publications on environmental design crime prevention research from 1998 to 2023.

As shown in , depicting the annual distribution of literature volume on Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design, the number of related publications exhibits an overall fluctuating upward trend from 1998 to 2023. In 1998, the WOS core database first included literature related to CPTED research. Before 2004, there was a period of low publication volume, followed by a gradual increase since 2004. The pace of literature growth experienced a slight acceleration in 2011, and after reaching its peak in 2019, the number of publications gradually declined.

4.2. Analysis of research development stages

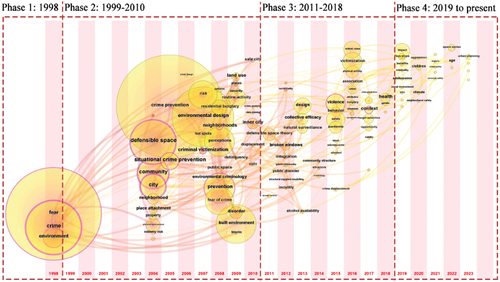

The keyword’s time zone view can vividly illustrate the distribution of research hotspots during different time intervals. Observing these hotspots can summarize the evolving trends in research content over time, thereby aiding in identifying the distribution and evolution of disciplinary research frontiers (Tang and Wei Citation2022). Highly cited literature often manifests as documents that capture the research themes and hot topics of a particular stage in the field, leading to the relevant academic frontiers in that domain (Yang and Li Citation2022). Typically, newly published papers receive minimal citations initially, and the cumulative citation frequency tends to increase (C. Q. Guo and Si Citation2023). Based on this citation pattern, the duration method is combined with the 1% threshold of highly cited papers to establish annual standards (X. L. Liu Citation2012). From 1998 to 2023, there were 21 core highly cited papers in environmental design crime prevention and four non-core highly cited papers. This is shown in -statistics of highly cited literature on environmental design crime prevention research. According to the above analysis of the number of publications, the research on environmental design crime prevention can be divided into four development stages, with 1998, 2011, and 2019 as time breakpoints. Combined with the research background of the four development stages, keyword time zone map, and high frequency Cite literature for in-depth analysis to determine the expansion trend, richness, and disciplinary vitality of the research field (Chen et al. Citation2015).

Table 1. Statistics of highly cited literature on environmental design crime prevention research.

The first stage is the outset exploration stage (1998): In 1996, the United Nations Centre for Human Settlements proposed the Safer City Programme to address urban safety issues and improve cities’ safety and crime prevention mechanisms (http://www.cpted.net/). In (Citation1998), Kuo et al. published a paper titled “Transforming inner-city Landscapes Trees, sense of Safety, and Preference,” the first literature on environmental design crime prevention and the most frequently cited (314 times) literature. This study found through a survey of 100 residents in the Robert Taylor residential area of Chicago that environmental factors (maintenance of trees and grass) can reduce the fear of crime among community residents, revealing the critical role of environmental maintenance in shaping community security and providing strong support for targeted environmental improvement measures to reduce fear of crime (F. E. Kuo, Bacaicoa, and Sullivan Citation1998).According to the Environmental Design for Crime Prevention 1998–2023 Research Keywords Time Zone View(), it can be seen that the keywords “fear,” “crime,” and “environment” introduced in this literature have high centrality, indicating that this literature has an essential guiding role in environmental design crime prevention research.

The second stage is the initial exploration stage (1999–2010): The relevant literature on environmental design crime prevention is relatively tiny at this stage. The total number of literature publications in the WOS core database is 32, with an average of less than three publications per year, and the growth is relatively slow. In 1999, Atlas R presented a paper titled “The Alchemy of CPTED: Less Magic, More Science” at the Fourth International CPTED Association Conference, which pointed out that as terrorism and street, crime continue to pose a threat to society, there is an urgent need to use scientific methods, such as risk assessment models, to apply CPTED to built environments to create safe living environments (R. Atlas Citation1999). Kuo, F and Sullivan, W compared the crime rates of 98 apartment buildings with different vegetation levels and found that the richer the vegetation around the buildings, the lower the crime rate(F. Kuo and Sullivan Citation2001). In the book Preventing Crime at Places, Eck, J points out that the physical conditions of the built environment have a potential impact on crime and fear of crime(Eck Citation2002). Subsequently, researchers such as Stucky, TD, Brown, BB, and Wilcox, P. began to focus on environmental factors influencing crime and the fear of crime (Brown, Perkins, and Brown Citation2004; Stucky and Ottensmann Citation2009a; Wilcox, Madensen, and Tillyer Citation2007). Casteel, C, Carter, SP, and Reynald, DM have been mainly focused on exploring the effectiveness of crime prevention through environmental design in reducing crime (Carter, Carter, and Dannenberg Citation2003; Casteel and Peek-Asa Citation2000; Reynald and Elffers Citation2009). Analysis of the keyword temporal zone view () and highly cited literature statistics () in the field of environmental design for crime prevention reveals the appearance of keywords such as “neighborhood,” “community,” “city,” “built environment,” “land use,” “physical environment,” “situational crime prevention,” “defensible space,” etc. These keywords indicate that research in this stage is primarily based on situational crime prevention, defensible space, crime prevention through environmental design, and other crime prevention theories. The focus is on urban communities, emphasizing the impact of physical environmental elements such as environmental maintenance, land use, and architectural design on crime and the fear of crime. This provides a preliminary discourse on implementing crime prevention measures in spatial environments (Brown, Perkins, and Brown Citation2004; Stucky and Ottensmann Citation2009a). In 2000, the United States issued the “Preventing Crime through Environmental Design: A General Guide for Designing Safer Communities”. In 2001, the Australian government introduced CPTED principles into the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979. In 2004, the UK released the design guidance “Safer Places: The Planning System and Crime Prevention.” In 2005, New Zealand enacted the ‘New Zealand crime prevention through environmental design National Guidelines. In summary, this stage emphasizes a more practical orientation, focusing on actual policies, guidelines, and implementation plans.

The third stage is the diversified expansion stage (2011–2018): In 2011, the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute (UNICRI) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology jointly published the report “Improving Urban Safety Through crime prevention through environmental design,” proposing for the first time the theoretical concept of the third generation of CPTED. This concept involves using green design principles to build sustainable cities, incorporating environmentally friendly and sustainable high-tech approaches into CPTED practices (P. Cozens and Love Citation2015). The theoretical concept of the third generation of CPTED was first proposed, advocating the construction of sustainable cities through green design principles. The core idea involves the application of environmentally friendly and sustainable high-tech approaches to CPTED practices. The introduction of the third-generation CPTED, centered on sustainability, has spurred extensive research in academia on how environmental design can prevent crime. During this stage, the literature has expanded significantly, with a total of 164 publications, representing a 4.3-fold increase compared to the previous stage, with an average annual publication exceeding 20 articles. New keywords introduced during this stage include “target selection,” “natural surveillance,” “territoriality,” “collective efficacy,” “broken windows,” “physical activity,” “urban planning,” “health,” and “Google Street View.” The abundance of literature and the addition of diverse keywords indicate a broadening of research during this stage. An analysis of highly cited literature during this stage () reveals a particular focus on residents’ health as a new area of interest in environmental design for crime prevention research. Lorenc, T., and colleagues conducted a review of the theoretical and empirical literature on the connections between criminal behavior, fear of crime, social and built environments, and health (Lorenc et al. Citation2012). He, L., and Patino, JE began utilizing remote sensing technology and Google Street View to extract large-scale environmental features, delving into an in-depth exploration of the correlation between urban spatial environmental features and crime (He, Páez, and Liu Citation2017; Patino et al. Citation2014). Relevant studies started considering the impact of the social environmental element “collective efficacy” on crime from the second generation of CPTED. For instance, Heinze, JE, emphasized enhancing collective efficacy through community greening participation to reduce the occurrence of criminal behavior (Heinze et al. Citation2018). The Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) expert Cozens P reviewed the current status of CPTED, including its history, common understanding, and global applications, and discussed major challenges facing the field (P. Cozens and Love Citation2015). Furthermore, it was proposed that CPTED must continually adapt to various changes, such as ongoing urbanization, population density, demographic diversity, new technologies and products, new lifestyles, and emerging crime issues.

The fourth stage is the deepening development stage (from 2019 to present): In this stage, the annual average publication of research literature on environmental design for crime prevention exceeds 23 articles, reaching a peak of 33 articles by 2019. The United States significantly contributes to this stage, with a total of 14 articles, accounting for over 40% of the total publications. The National Crime Victimization Survey Report by the Bureau of Justice Statistics in the United States reveals a continuous increase in the number of victims of violent crimes from 2015 to 2018, reaching a peak of 3.3 million in 2018 (https://xueqiu.com/7886851669/132698844). According to a database jointly established by the Associated Press, USA Today, and Northeastern University in Boston, there were 41 mass killings in the United States in 2019, resulting in a total of 211 fatalities, marking the highest number of mass killings in U.S. history (www.haiwainet.cn). This prompted a deeper academic investigation into environmental design for crime prevention. Subsequently, in 2021, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) officially released the “Guidelines for Safety and Resilience, Protective Security, and crime prevention through environmental design” (ISO 22,341–2021), outlining principles, elements, strategies, and processes to reduce crime. The introduction of these guidelines provides a more systematic and standardized foundation for research on environmental design for crime prevention, driving the field towards greater depth and specialization. Through an analysis of highly cited literature () combined with newly added keywords such as “children,” “space syntax,” and “public spaces” (), it is evident that research on environmental design for crime prevention has begun to consider the needs of different demographics, with a particular focus on children (Y. Huang et al. Citation2023). Some scholars have started to investigate the relationship between spatial structure and crime, primarily using space syntax to explore how spatial structures influence the occurrence and distribution of crime (Kezuwani and Said Citation2021; Othman, Yusoff, and Salleh Citation2019). Another group of scholars has shifted their attention to the impact of “public space regeneration” on crime and the fear of crime, aiming to enhance the quality and attractiveness of spaces, stimulate community vitality, promote economic activities, and enhance overall urban sustainability. Additionally, the rise of geospatial big data has provided new perspectives for quantitative research on the relationship between crime and the built environment (Patino et al. Citation2014). For instance, Nanxi Su et al. utilized computer vision and machine learning, along with publicly accessible street view image data, to quantitatively study the association between the urban design quality (UDQ) of ground environments around subway stations and crime density (Su, Li, and Qiu Citation2023). Wo, J.C. et al. employed a Geographic Information System (Arc GIS 10.5) to geocode crime events, studying the impact of mixed land use on crime rates (Wo Citation2019). Zhang, F et al. utilized computer vision technology and publicly available street view data to measure the differences between crime and perceived safety (F. Zhang et al. Citation2021).

5. Analysis of hotspots in crime prevention through environmental design research: based on keyword co-occurrence map and keyword cluster chart

5.1. Keyword co-occurrence analysis

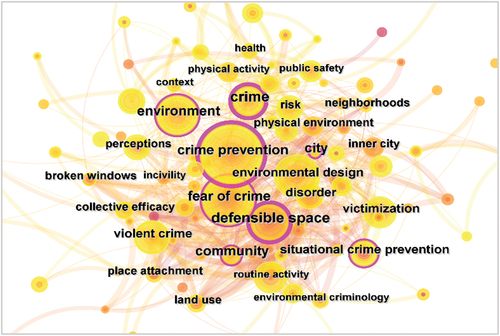

Keywords serve as a concise summary and abstraction of the core content of the article, clearly reflecting the thematic concepts and main research focus of the paper (Gao and Peng Citation2020). The centrality of keywords demonstrates the importance of network nodes and their impact on information transmission. Keywords with high centrality are often critical hubs in the network, and nodes with a centrality of not less than 0.1 are called critical nodes (Q. Zhang et al. Citation2022). According to Price’s law, high-frequency keywords are defined when the observed exponent (α) is 7.223; thus, keywords with a frequency of ≥8 are considered high-frequency. In , keywords that appear eight times or more and have centrality ≥0.10 mainly include crime prevention, fear of crime, Environment, defensible space, Crime, violent crime, City, Disorder, and situational crime prevention. Combining with relevant literature analysis reveals that research on environmental design for crime prevention is grounded in crime prevention theories such as situational crime prevention and defensible space. The primary focus is on the impact of urban spatial environmental features on crime and the fear of crime.

Table 2. Co-occurrence frequency and intermediary neutrality of hot keywords in environmental design crime prevention research.

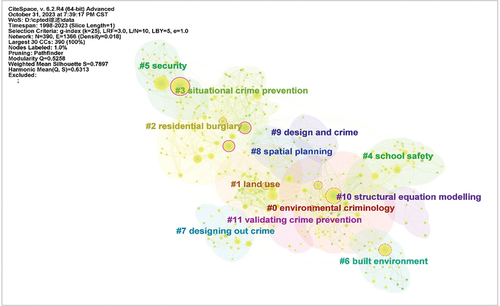

5.2. Keyword cluster analysis

Keyword clustering analysis can swiftly capture the hot topics in a research field (Zhou, Liu, and Liu Citation2020). Based on the co-occurrence analysis of keywords in environmental design for crime prevention research, clustering analysis was conducted on the keywords to elucidate the distribution of themes, as shown in . The modularity value (Q value) for this clustering module is 0.5258 (>0.5), and the average silhouette value (S value) is 0.7897 (>0.7), indicating that the keyword clustering network structure is significant, and the clustering effect is reasonable (Chen et al. Citation2015). Using the Log-Likelihood Ratio (LLR) algorithm to obtain the top-ranking keywords as clustering labels, a total of 12 sub-clusters were formed, including #0. environmental criminology, #1. land use, #2. residential burglary, #3. situational crime prevention, #4. school safety, #5. security, #6. built environment, etc. By assessing the similarity of keywords within sub-cluster labels and combining them with relevant literature interpretation, the research themes in environmental design for crime prevention can be categorized into three major groups, including studies on the relationship between crime and spatial environmental features, the effectiveness measurement of crime prevention through environmental design measures, and foundational theoretical research.

5.2.1. Research on the relationship between spatial environment characteristics and crime

Based on the labels of each cluster and the content of the involved literature, it is evident that the four sub-clusters, #1. land use, #6. built environment, #8. spatial planning, and #9. design and crime mainly focused on studying the relationship between spatial environmental features and crime. Research on the relationship between spatial environment and crime emphasizes identifying and measuring environmental elements and exploring the relationship between a specific type of environmental element and criminal behavior. The goal is to identify the causes of crime, explore crime prevention strategies, and provide a basis for environmental design for crime prevention. Such studies typically employ extensive data methods such as GIS, spatial syntax, Google Street View, etc., to measure the environment. Using various statistical analysis models, quantitative analyses of spatial environments are conducted, primarily focusing on the relationship between land use, spatial planning, micro built environment, and crime.

5.2.1.1. Land use and crime

Environmental criminology research focuses on the spatial distribution of crime, revealing relationships between certain land use types, such as the concentration of commercial and residential areas, and crime rates and their impact on the types and intensity of crimes (Salleh et al. Citation2012). Stucky, TD et al. used a negative binomial regression model to study the relationship between the number of violent crimes and land use, finding a higher rate of violent crime in non-residential areas (Stucky and Ottensmann Citation2009a). Anderson, JM et al. conducted a systematic social observation of 205 blocks in high-crime areas of Los Angeles, discovering that the crime rate in mixed-use areas combining commercial and residential properties was lower than in purely commercial areas(Anderson et al. Citation2013). Sohn DW et al. attempted to investigate the relationship between commercial land use combinations and residential crime(Dong-Wook Citation2016). The study’s results suggested that grocery stores, restaurants, and offices positively improve community safety. At the same time, neighborhoods with a higher concentration of shopping center areas tend to have higher residential burglary rates.

5.2.1.2. Space planning and crime

As early as the 2007 Global Report on Human Settlements, it was pointed out that public space planning significantly impacts urban crime occurrence and prevention (United Nations Human Settlements Programme Citation2007). Streets constitute a crucial part of urban space, the most frequently used public spaces in residents’ daily lives, work, travel, and social activities. Criminal activities unfold based on key nodes of the daily activities of offenders or victims and the pathways connecting these nodes (Felson and Boivin Citation2015). Therefore, relevant studies explore the relationship between neighborhood planning and design and crime. For instance, Liu, DQ et al. examined the spatial patterns of violent crime in Changchun, China, using crime data compiled at the jurisdictional level in 2008 (D. Liu, Song, and Xiu Citation2016). They explored the relationship between the spatial distribution of violent crime and neighborhood characteristics, finding that high-risk areas for violent crime were concentrated in the city’s central region. Zeng, ML and Yue, H et al. suggested that, in urban planning, improving streetscape features and increasing street usage frequency can reduce the occurrence of crime (Jonghoon, Seongwoo, and Hyngbaek Citation2014; Zeng, Mao, and Wang Citation2021).

5.2.1.3. Micro -building environment and crime

The “eyes on the street” theory asserts that the correlation between the built environment and crime is primarily influenced by environmental decay, pedestrian traffic, and resident interaction. The broken windows theory posits that environmental decay in the built environment, such as broken windows, vacant/abandoned houses, and abandoned cars on the streets, is not only evidence of potential criminal activity but also induces more deviant and criminal behavior (Wilson and Kelling Citation1982). CPTED theory argues that appropriately designing and modifying six environmental elements can create a “defensible space”, thereby reducing crime opportunities (Marzbali, Abdullah, Razak, and Tilak Citation2012). These elements include territorial reinforcement (e.g., fences, building signage, etc.), surveillance, access control, activity support (e.g., increasing legitimate activities in parks), image/maintenance, and target hardening (e.g., protective nets, alarms). Based on these theories, scholars in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Malaysia, and other countries have extensively explored the correlation between various micro-level built environment features and crime (Foster et al. Citation2016; Hong and Chen Citation2014; Marzbali, Abdullah, Razak, and Tilaki Citation2012). Previous research has found a strong correlation between micro-level built environment variables such as fences or walls, tree and shrub morphology, illegal graffiti, architectural greenery, and crime occurrence (P. Cozens and Love Citation2015; F. E. Kuo, Bacaicoa, and Sullivan Citation1998; Schinasi et al. Citation2023; Shobe and Banis Citation2014). Cozens et al. highlighted the significant impact of improving environmental disorder on constructing a “defensible space,” reducing crime opportunities, suppressing crime levels, and lowering the fear of crime (P. Cozens and Love Citation2015).

Some studies indicate that the influence of the built environment on crime depends on social and environmental factors, and neglecting these social and environmental factors may lead to a spurious or non-existent correlation between the built environment and crime (Markowitz et al. Citation2001; Wilcox et al. Citation2003). Accurately understanding the interactive mechanisms among social, environmental factors, built environment factors, and urban crime is of vital theoretical and practical significance for providing refined environmental design strategies. Analysis of relevant literature reveals that current research mainly focuses on the direct correlation between the built environment and crime, including aspects such as land use, spatial planning, and micro-environments, while also considering macro-level social factors such as the economy, family structure, and racial heterogeneity (P. Cozens and Love Citation2015; Zeng, Mao, and Wang Citation2021; Dong-Wook Citation2016). However, more in-depth research is still needed on the collaborative mechanisms between the built and social environments in the formation of crime processes.

5.2.2. Environmental design prevention of crime implementation results measurement research

Combining the labels extracted from and the literature content involved, it can be observed that the five sub-clusters #2. residential burglary, #4. school safety, #5. security, #10. structural equation modeling, and #11. validating crime prevention primarily focus on the implementation effectiveness measurement of crime prevention through environmental design. The implementation effectiveness measurement of crime prevention through environmental design aims to verify and optimize the effectiveness of crime prevention strategies, guide decision-making, and provide scientific support and guidance for creating safer and more livable urban environments. The main research objects of implementation effectiveness measurement are concentrated in school and residential spatial environments, emphasizing the application of mathematical and statistical methods such as structural equation modeling to explore the impact of environmental characteristics under various CPTED elements. The key components include the construction of environmental assessment indicators, the assessment of spatial environmental security, and the investigation of the effectiveness of CPTED measures.

5.2.2.1. Environmental evaluation index constructing

The construction of environmental assessment indicators is primarily based on the CPTED theory, selecting environmental elements for assessing crime risks or perceptions of safety. Researchers seek to identify inherent patterns by evaluating these environmental elements, deriving genuinely effective assessment indicators. For instance, Minnery and Lim (Minnery and Lim Citation2005). created a scale for measuring the level of CPTED implementation in spatial environments and assessed the relationship between CPTED measures and crime rates. Subsequently, Malaysian scholars Marzbali et al. used structural equation modeling to identify indicators that contribute to measuring CPTED measures (Marzbali, Abdullah, Razak, and Tilak Citation2012). Armitage and Peeters, after evaluating the risk of residential burglary at the levels of homes and streets, proposed that environmental elements such as housing structure, road network structure, and management and maintenance should be included in the indicator system for assessing residential burglary risk (Armitage Citation2006; Peeters, Daele, and Beken Citation2018).

5.2.2.2. Space Environmental Security Evaluation

Spatial environmental safety assessment refers to using existing CPTED assessment indicator systems or audit checklists to evaluate the crime risk of a specific space or area, guiding the formulation of environmental design or management strategies. For example, Matzopoulos et al. employed linear models to assess the relationship between urban upgrades and violent crime, finding that after upgrading urban infrastructure by applying CPTED principles, the risk of violent crime decreased by 34% (Matzopoulos et al. Citation2020). Said et al., using CPTED elements as assessment variables, utilized a scoring system to evaluate the safety of three heritage buildings in Malaysia. The analysis revealed a need to consider more crime prevention mechanisms in designing these heritage buildings (Said and Mering Citation2019). Based on CPTED theory, communities around 14 elementary schools serving low-income populations in Seattle were studied (Lee et al. Citation2023). Using environmental audit tools for assessment, they found correlations between landscape maintenance, geographical juxtaposition features, and violent and property crimes.

5.2.2.3. Effective Inquiry of CPTED measures

The exploration of the effectiveness of CPTED measures mainly involves evaluating the on-the-ground effects of CPTED practical projects and assessing the impact of CPTED measures on crime and the fear of crime. For example, Jeong et al. used actual crime data from the Yumul-ri neighborhood in Mapo-gu, Seoul, South Korea, before and after the implementation of CPTED to identify changes in crime rates. Through quantitative methods and Weighted Displacement Quotient (WDQ) analysis, they found that CPTED measures effectively reduce property crimes but are ineffective against violent crimes (Jeong, Kang, and Lee Citation2017). Taehoon Ha and colleagues compared and analyzed CPTED housing environments with non-CPTED housing environments in South Korea, discovering significant effectiveness in reducing criminal activities through CPTED (Ha, Oh, and Park Citation2015). Marzbali et al., using structural equation modeling, analyzed the impact of CPTED measures on victims and the fear of crime. The results showed that CPTED measures positively reduce the risk of individuals becoming crime victims. Additionally, crime victims perceived a significant reduction in their fear of crime due to CPTED (Marzbali, Abdullah, Razak, and Tilak Citation2012). Piroozfar et al. employed a mixed-methods approach, conducting visual audits of CPTED, critical analysis of police crime data, surveys, and semi-structured interviews to evaluate the effectiveness of CPTED intervention principles in the Brixton Town Centre (BTC) in London (Piroozfar et al. Citation2019). The study found decreased crime rates in BTC since the introduction of intervention measures in 2011.

Currently, research on the implementation effectiveness measurement of environmental design for crime prevention predominantly focuses on cross-sectional analyses, lacking longitudinal studies tracking the long-term effects of crime prevention measures. Cross-sectional analysis provides information on the impact of environmental design measures within a specific time frame. However, it struggles to comprehensively understand the long-term effects and evolutionary trends of these measures. Therefore, future research should employ a combined cross-sectional and longitudinal analytical approach to more comprehensively and accurately assess the sustained effects of crime prevention measures across different temporal and spatial contexts.

5.2.3. Basic theoretical research on environmental design prevention crime

Theoretical research on environmental design for crime prevention aims to promote the practical application and theoretical refinement of crime prevention theories in environmental design to better meet practical needs and adapt to the continuously changing social environment. The three sub-clusters, #0.environmental criminology, #3.situational crime prevention, and #7.designing out crime, along with relevant literature, primarily focus on the foundational theoretical research of environmental design for crime prevention. Through further synthesis and summarization, it can be observed that the research objectives of theoretical studies can be categorized into two main types: first, based on the analysis and adaptation of the CPTED theory, providing applied guidance for crime prevention efforts; second, addressing the deficiencies in existing research results by redefining concepts, improving theories, or reconstructing frameworks within the CPTED theory. The pioneering scholar in crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) theory is the Australian criminology expert Cozens, P. His foundational theoretical research is characterized by a comprehensive review of CPTED theory and related literature (Cozens and Cozens Citation2008) an in-depth definition of various elements within the basic CPTED framework, and a review of existing research findings. Adopting a dialectical approach, he critically examines evidence related to the empirical effects of CPTED theory (P. Cozens and Love Citation2015). He provides a detailed overview of the primary criticisms faced by this field. While acknowledging the positive impact of CPTED, Cozens also identified its limitations. These include challenges in achieving crime prevention for irrational offenders with the first-generation CPTED measures. Negative economic and demographic dynamics might weaken the effectiveness of CPTED measures, while positive changes could enhance their impact. The primary criticisms faced by CPTED include concerns that its implementation in one location might shift crime to other places or times, leading to changes in criminal methods, targets, and types without an overall crime reduction. Neighborhood social-ecological thresholds can impose certain limitations on crime prevention measures. Without sufficient community involvement, overreliance on target hardening in CPTED measures may lead to a “fortress mentality,” where residents seek refuge behind walls, fences, and reinforced homes. In addition, Ekblom outlined the evidence regarding the effectiveness of crime prevention through environmental design in reducing crime (Ekblom Citation2011). He rigorously examined the impact of environmental features under each CPTED element on crime, discussing areas where CPTED requires theoretical and practical improvement. Armitage and colleagues described the current state of research on updating and upgrading CPTED theory (Armitage and Monchuk Citation2019). They introduced the latest practical attempts to integrate CPTED with developments in architectural design, environmental design, and criminology, providing insights into the interdisciplinary research and development of CPTED. The core elements of CPTED, such as natural surveillance, territoriality, and target hardening, are influenced by diverse factors, including culture, social structure, and regional characteristics. The applicability of these elements demonstrates complex cultural, geographical, and sociological dynamics across different environments. Current research on CPTED theory has primarily focused on tracing related theories, interpreting foundational concepts in depth, and critically reviewing existing literature. There is limited research delving into the practical applicability of the theory in specific geographical and cultural contexts. Analyzing the impact of local culture, social structures, regulations, and regional characteristics, among other diverse factors, is essential to effectively discuss the applicability of crime prevention through environmental design theory in different countries, considering their unique national conditions and specific social spatial environments.

6. Analysis of future research trends in crime prevention through environmental design

The theoretical foundation of environmental design for crime prevention originated in the 1970s in the United Kingdom and the United States. It has undergone several self-revisions and adjustments since its inception, evolving into a mature theoretical framework that guides subsequent research. The study of environmental design for crime prevention has traversed the processes of theoretical development, empirical research, and practical application. In recent years, significant progress has been made in research related to environmental design for crime prevention, showcasing a developmental trend from “simple use of statistical analysis and data models to explore the relationship between different environmental designs and crime” to “utilizing big data methods such as spatial syntax, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), and street view image technology to investigate crime data and environmental characteristics.”In terms of research content, the study of environmental design for crime prevention has progressed from the initial “assessment of the on-site effects of CPTED projects” to in-depth explorations of various effects, such as “the impact of CPTED measures on the fear of crime” and “the influence of CPTED measures on residents” physical and psychological health.” The research perspective has also shifted from solely ‘focusing on reducing the occurrence of unlawful behaviors’ and ‘reducing residents’ fear of crime” to encompass broader aspects, including “concern for improving residents” physical and psychological health,” ‘enhancing residents’ quality of life,” and “promoting residents” social interactions,’ demonstrating a comprehensive understanding of the benefits.

While research on environmental design for crime prevention has entered a phase of deepening development, the current state of research still presents several pressing issues. These issues primarily include a limited amount of comprehensive research on the overall mechanisms of the correlation between urban environmental characteristics and crime, with a need for studies that integrate the built environment and social environment, insufficient exploration of the effectiveness of environmental design for crime prevention, with a lack of thorough capturing and analysis of the long-term dynamic effects of CPTED measures; and a deficiency in the in-depth study of the applicability of environmental design for crime prevention theory in different cultural and social contexts. Therefore, considering the background, current status, and recent research trends in environmental design for crime prevention, future research should focus on the following three aspects.

6.1. The spatiotemporal heterogeneity of the impact of urban built environments and social environments on crime

Existing studies have indicated that criminal behavior is often not determined by a single factor but results from complex interactions among multiple elements (Mao et al. Citation2018). Some literature suggests that the ability to accurately describe the built environment’s impact on crime largely depends on which variables control the social environment. Neglecting social factors may result in a spurious or non-existent correlation between the built environment and crime (He, Páez, and Liu Citation2017; L. Liu, Du, and Song Citation2018; Long et al. Citation2017). In their empirical study, He et al. attempted to employ a systematic and step-by-step analytical approach, logically integrating social and built environment characteristics (He, Páez, and Liu Citation2017). However, this coupled spatiotemporal heterogeneity analysis scheme integrating social and built environments in crime requires further in-depth exploration. Therefore, future research should delineate these two environments’ interdependence and coupling paths from multidimensional theoretical perspectives, including social, environmental, behavioral, and psychological aspects. From the integrated perspective of the built and social environments, the study should leverage big data to comprehensively characterize the environment, using heterogeneous data sources such as 110 emergency call data, mobile signaling data, city street view data, POI data, etc. The research should systematically investigate the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of the impact of urban built and social environments on crime. Additionally, considering the spatial non-stationarity of social factors’ impact on crime, future research should explore more targeted methods for selecting built environment sample points. This involves conducting empirical analyses based on targeted sampling and systematic integration, ensuring that the selection of built environment observation points better reflects spatial variations and social factors within the city. This approach aims to gain a more accurate understanding of the relationship between environmental design and crime. It also seeks to uncover the conditional interactive mechanisms of built and social environments on crime, providing a scientific basis for crime prevention through environmental design.

6.2. The multifactorial longitudinal correlation effects between environmental characteristics under each element of CPTED and criminal behavior

The interweaving of technological progress, socioeconomic evolution, and cultural shifts has led to the complexity of crime, posing challenges in addressing the intricate nature of criminal issues. Future research should delve deeply into the longitudinal associations between various elements of CPTED and crime, comprehensively analyzing the impact of environmental design changes on the long-term security of cities. Accordingly, there is a need for continuous collection of data on environmental features and crime rates to track their changes over time. This includes regular assessments of environmental factors such as street design, building maintenance, and community investment, as well as periodic updates of crime data. Additionally, seasonal factors such as weather, specific events, and other elements that may influence environmental design and crime rates should be considered for a more accurate analysis of the causal relationship between environmental features and crime rates under different elements of CPTED. Through this in-depth research and data collection, a more comprehensive assessment indicator system for crime prevention through environmental design can be developed, providing scientific support for the formulation of crime prevention policies and urban security management. In conclusion, this multi-factor longitudinal correlation study can offer a more comprehensive understanding of the trends in the impact of crime prevention through environmental design measures on crime rates. It can provide more reliable evidence for future urban planning and crime prevention policies, contributing to the establishment of safer and more sustainable urban environments.

6.3. The local applicability of crime prevention through environmental design theory under multIcultural and regional differences

In recent years, some studies have been making beneficial innovative attempts at accurately operationalizing key elements in CPTED theory. Some scholars have re-examined the research on CPTED theory, advocating for its integration with sustainability. Despite some progress in foundational research on environmental design for crime prevention, there is still a lack of in-depth exploration regarding cultural and regional differences. To advance the integration of CPTED with social sustainability, future research should emphasize societal equality and inclusivity in applying crime prevention theories. Therefore, it is necessary to comprehensively consider and explain the potential impacts of different cultures and regions on implementing this theory within the theoretical framework, ensuring the universal applicability of environmental design for crime prevention strategies to all groups and reducing social inequality.

Moreover, to promote the practical development of CPTED theory globally, there should be a strengthened depth analysis and dialectical thinking on the foundational theory. This involves further fostering interdisciplinary integration of CPTED theory into various fields, such as social sciences, public health, and information technology. This will establish scientific application assessment methods to guide practical implementation, achieve empirical reverse correction, and refine a CPTED theoretical system applicable to the situations of different countries. By integrating viewpoints from different disciplines, a more comprehensive and holistic CPTED theoretical framework can be formed to promote the application of CPTED theory in a broader range of fields. This contributes to creating healthier and more sustainable living environments in society. In-depth studies on local applicability assist in developing a more nuanced and universally applicable CPTED theory, offering more targeted crime prevention solutions for communities worldwide.

7. Conclusion

Based on the WOSCC database, a combination of bibliometric methods and traditional literature analysis was employed to explore the current status, research hotspots, and development trends in environmental design for crime prevention, utilizing the Cite Space software. The following conclusions were drawn: (1) In terms of research methods, recent studies in environmental design for crime prevention primarily utilize spatial syntax, GIS, and machine learning techniques such as Google Street View combined with big data methods to investigate the impact mechanisms of environmental factors on crime. (2) Regarding research hotspots, the field predominantly focuses on exploring the relationship between the built environment and crime and the relationship between the built environment and the fear of crime. Additionally, the effectiveness of CPTED measures and the practical application and refinement of CPTED theory are prominent areas of investigation. (3) Criminological theories posit that crime results from the interplay of multiple interconnected factors and exhibits high complexity. Within this theoretical framework, social and built environments are identified as two key factors influencing the mechanism of crime formation. Hence, future research should delve into the coupling relationship between social and built environments in terms of spatiotemporal heterogeneity of crime, comprehensively understanding the mechanism of spatiotemporal heterogeneity in crime. Evaluating the effectiveness of environmental design for crime prevention measures should emphasize a careful consideration of multi-factor longitudinal correlation effects to assist in formulating crime prevention strategies with lasting efficacy. In the construction and application of CPTED theory, attention should be given to multiculturalism and regional variations, thereby promoting the deepening of the theory and enhancing its applicability in different geographical and cultural contexts.

This study comprehensively presents the research progress, context, current status, and future directions in the field of environmental design for crime prevention. It contributes to a deeper understanding of the knowledge landscape in this domain, providing more accurate and comprehensive reference points for academic research and practical applications. Consequently, it propels knowledge development in the field, fostering advancements at the forefront of the discipline. Furthermore, the research aids in promoting the practical application of environmental design for crime prevention theory and optimizing strategies to address emerging social issues and crime patterns, offering robust support for the sustainable development of urban areas.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yu Wen

Yu Wen Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, writing—review and editing, project administration

Hong Qi

Hong Qing software, data curation, writing—original draft preparation.

Tao Long

Tao Long investigation, resources, visualization.

Xinjia Zhang

Xinjia Zhang Review, Supervision

References

- Anderson, J. M., J. M. Macdonald, R. Bluthenthal, and J. S. Ashwood. 2013. “Reducing Crime by Shaping the Built Environment with Zoning: An Empirical Study of Los Angeles.” Social Science Electronic Publishing 161 (3): 699–756. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2109511.

- Armitage, R. 2006. “Predicting and Preventing: Developing a Risk Assessment Mechanism for Residential Housing.” Crime Prevention and Community Safety 8 (3): 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.cpcs.8150024.

- Armitage, R., and L. Monchuk. 2019. “What Is CPTED? Reconnecting Theory with Application in the Words of Users and Abusers.” Policing-A Journal of Policy and Practice 13 (3): 312–330. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pax004.

- Atlas, R. 1999. “The Alchemy of CPTED: Less Magic, More Science.” In Conference Paper presented at the 4th International CPTED Association Conference, September, Toronto, Canada. City of Mississauga’s Living Arts Centre.

- Atlas, R. I., and D. Fitzgerald. 2008. “21st Century Security and CPTED: Designing for Critical Infrastructure Protection and Crime Prevention.” Landscape Architecture 99 (8): 104–104. https://doi.org/10.1145/1552285.1552289.

- Brown, B. B., D. D. Perkins, and G. Brown. 2004. “‘Incivilities, Place Attachment and Crime: Block and Individual Effects.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 24 (3): 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2004.01.001.

- Carter, S. P., S. L. Carter, and A. L. Dannenberg. 2003. “Zoning Out Crime and Improving Community Health in Sarasota, Florida: Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design.” American Journal of Public Health 93 (9): 1442–1445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.10.011.

- Casteel, C., and C. Peek-Asa. 2000. “Effectiveness of Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED) in Reducing Robberies.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 18 (4): 99–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00146-x.

- Chen, Y., C. M. Chen, Z. Y. Liu, Z. G. Hu, and X. W. Wang. 2015. “The Methodology Function of Cite Space Mapping Knowledge Domains.” Studies in Science of Science 33 (2): 242–253. https://doi.org/10.16192/j.cnki.1003-2053.2015.02.009.

- Clancey, G. 2011. “Crime Risk Assessments in New South Wales.” European Journal on Criminal Policy & Research 17 (1): 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-010-9134-7.

- Clarke, R. V. 1997. Situational crime prevention. Successful case studies. Criminal Justice Press. Wilson, J. Q. and G. L. Kelling. 1982. “Broken Windows: The Police and Neighborhood Safety.” The Atlantic Monthly 127 (3): 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118517383.wbeccj077.

- Clos, J. 2011. “Un-Habitat: For a Better Urban Future.” China City Planning Review 1:34–35. https://CNKI:SUN:CSGY.0.2011-02-006.

- Cohen, L. E., and M. Felson. 1979. “Social Change and Crime Rate Trends: A Routine Activity Approach.” American Sociological Review 4 (4): 588–605. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094589.

- Cozens P. M. 2008. “New Urbanism, Crime and the Suburbs: A Review of the Evidence.” Urban Policy & Research 26 (4): 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111140802084759.

- Cozens, P., and T. Love. 2015. “A Review and Current Status of Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED).” Journal of Planning Literature Incorporating the CPL Bibliographies 30 (4): 439–442. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412215595440.

- Dong-Wook, S. 2016. “Do All Commercial Land Uses Deteriorate Neighborhood Safety?: Examining the Relationship Between Commercial Land-Use Mix and Residential Burglary.” Habitat International 55:148–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.03.007.

- Eck, J. E. 2002. Preventing Crime at Places. In Evidence-Based Crime Prevention. London: Routledge.

- Ekblom, P. 2011. “Deconstructing CPTED … and Reconstructing it for Practice, Knowledge Management and Research.” European Journal on Criminal Policy & Research 17 (1): 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-010-9132-9.

- Felson, M., and R. Boivin. 2015. “Daily Crime Flows within a City.” Crime Science 4:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-015-0039-0.

- Foster, S., B. Giles-Corti, and M. Knuiman. 2011. “Creating Safe Walkable Streetscapes: Does House Design and Upkeep Discourage Incivilities in Suburban Neighbourhoods?” Journal of Environmental Psychology 31 (1): 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.03.005.

- Foster, S., P. Hooper, M. Knuiman, F. Bull, and B. Giles-Corti. 2016. “Are Liveable Neighbourhoods Safer Neighbourhoods? Testing the Rhetoric on New Urbanism and Safety from Crime in Perth, Western Australia.” Social Science & Medicine 164:150–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.04.013.

- Gao, J. S., and B. Peng. 2020. “Research Hotspot Mining Method from the Perspective of Keyword Frequency Evolution.” Library & Information 40 (3): 61–70. https://CNKI:SUN:BOOK.0.2020-03-016.

- Guo, T., N. Ren, S. T. Gui, J. F. Ma, and J. Cao. 2017. “Spatiotemporal Analysis of Crop Models Based on Climate Change.” Jiangsu Agricultural Sciences 45 (24): 17–25. https://doi.org/10.15889/j.issn.1002-1302.2017.24.004.

- Guo, C. Q., and L. Si. 2023. “Research on the Impact of Library and Information Science Knowledge-Analysis of Citation Data Based on WoS 2000-2019 Highly Cited Papers.” Library Development 2:86–97. https://doi.org/10.19764/j.cnki.tsgjs.20211792.

- Han, X. H. 2018. “ENISA Report on Emerging Technologies and Security Challenges.” Information Security and Communications Privacy 4:72–88. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1009-8054.2018.04.013/.

- Ha, T., G. S. Oh, and H. H. Park. 2015. “Comparative Analysis of Defensible Space in CPTED Housing and Non-CPTED Housing.” International Journal of Law Crime & Justice 43 (4): 496–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2014.11.005.

- Heinze, J. E., A. Krusky‐Morey, K. J. Vagi, T. M. Reischl, S. Franzen, N. K. Pruett, R. M. Cunningham, and M. A. Zimmerman. 2018. “Busy Streets Theory: The Effects of Community-Engaged Greening on Violence.” American Journal of Community Psychology 62 (1–2): 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12270.

- He, L., A. Páez, and D. Liu. 2017. “Built Environment and Violent Crime: An Environmental Audit Approach Using Google Street View.” Computers, Environment and Urban Systems 66:83–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compenvurbsys.2017.08.001.

- Hong, J., and C. Chen. 2014. “The Role of the Built Environment on Perceived Safety from Crime and Walking: Examining Direct and Indirect Impacts.” Transportation 41 (6): 1171–1185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-014-9535-4.

- Huang, Y., K. Hino, Y. Asami, H. Usui, and M. Nakajima. 2023. “Fear of Street Crime Among Japanese Mothers with Elementary School Children: A Questionnaire Survey Using Street Montage Photographs.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 23 (1): 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2023.2228931.

- Huang, D. K., and W. B. Lai. 2023. “Crime Prevention Through Safety Planning Based on Government Strategies: Experience and Practice.” Journal of Human Settlements in West China 38 (3): 54–59. https://doi.org/10.13791/j.cnki.hsfwest.20230308.

- Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. London, UK: Jonathon Cope.

- Jeffery, C. R. 1971. Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Jeong, Y., Y. Kang, and M. Lee. 2017. “Effectiveness of a Project Applying Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design in an Urban Area in South Korea.” Journal of Asian Architecture & Building Engineering 16 (3): 543–549. https://doi.org/10.3130/jaabe.16.543.

- Jonghoon, P., L. Seongwoo, and L. Hyngbaek. 2014. “Implications of Urban Planning Variables on Crime: Empirical Evidences in Seoul, South Korea1.” In 5th Central European Conference in Regional Science – CERS, 317–335. Košice, Slovak Republic.

- Kezuwani, N. K., and S. Y. Said. 2021. “Space Syntax-Able Attributions for Safety Consideration of Heritage Area.” Environment-Behaviour Proceedings Journal 6 (SI4): 67–72. https://doi.org/10.21834/ebpj.v6iSI4.2903.

- Kuo, F. E., M. Bacaicoa, and W. C. Sullivan. 1998. “Transforming Inner-City Landscapes: Trees, Sense of Safety, and Preference.” Environment & Behavior 30 (1): 28–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916598301002.

- Kuo, F., and W. Sullivan. 2001. “Environment and Crime in the City Does Vegetation Reduce Crime?” Environment and Behaviour 33 (3): 343–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/00139160121973025.

- Lee, S., C. Lee, J. W. Nam, A. V. Moudon, and J. A. Mendoza. 2023. “Street Environments and Crime Around Low-Income and Minority Schools: Adopting an Environmental Audit Tool to Assess Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED).” Landscape and Urban Planning 232:104676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2022.104676.

- Liu, X. L. 2012. “The Method for Defining Highly Cited Papers Based on the Web of Science and ESI Databases.” Chinese Journal of Scientific and Technical Periodicals 23 (6): 975–978.

- Liu, L., F. Y. Du, and G. W. Song. 2018. “Detecting and Characterizing Symbiotic Clusters of Crime.” Scientia Geographica Sinica 28 (9): 1199–1209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11442-018-1520-y.

- Liu, D., W. Song, and C. Xiu. 2016. “Spatial Patterns of Violent Crimes and Neighborhood Characteristics in Changchun, China.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology 49 (1): 53–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004865814547133.

- Liu, X. Q., Y. Y. Zhang, Z. X. Zhao, and Y. Rui. 2021. “Research Progress and Enlightenment of Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development: Bibliometric Analysis Based on 1990-2020 Web of Science Core Collection Literatures.” Human Geography 36 (2): 11. https://doi.org/10.13959/j.issn.1003-2398.2021.02.012.

- Li, D. Q., Y. F. Wang, and J. Ning. 2016. “Research on the Evolution Law of Communication Factors and Their Interaction in the Stage of Scholarly Communication.” Information Studies: Theory & Application 39 (1): 8–15. https://doi.org/10.16353/j.cnki.1000-7490.2016.01.002.

- Long, D. P., L. Ling, J. X. Feng, G. W. Song, Z. He, and J. J. Cao. 2017. “Comparisons of the Community Environment Effects on Burglary and Outdoor-Theft: A Case Study of ZH Peninsula in ZG City.” Scientia Geographica Sinica 72 (2): 341–355.

- Lorenc, T., S. Clayton, D. Neary, M. Petticrew, M. Whitehead, H. Thomson, S. Cummins, A. J. Sowden, and A. M. Renton. 2012. “Crime, Fear of Crime, Environment, and Mental Health and Wellbeing: Mapping Review of Theories and Causal Pathways.” Health & Place 18 (4): 757–765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.04.001.

- Luo, S. H. 2021. “How to Unlock Sdg-Oriented Business Innovation.” China Sustainability Tribune Z1:83–85. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=wYgW8A8u9vqxLacB5Ud_WQ4TRqvHnlDBqwZ8EuqU4wGYrivswFvxGuz2hI3yvnpdr9pB6w6wnGvUBIpe6lPz9XtyVciju0S305_E3-xSKfIzCgztJMFYpMZZX-obr3EMuVhC9P7lo3MMSMQmyiaKi-PyEBDERjg4&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

- Manjari, K. K., and I. Director, and India. 2023. “SAFE CITIES: Homogeneous Vs Heterogeneous Communities Role of Culture & Socio Economics in CPTED.” THe Ica newsletter: The international cpted association 19 (3): 6–11.

- Mao, Y. Y., L. Cheng, and M. L. Zheng. 2022. “From Social Security to Environmental Security: Curriculum Design of Professional Education.” Planners 38 (4): 147–152.

- Mao, Y. Y., L. Yin, J. Liu, M. L. Zeng, and L. Liang. 2018. “Review and Reflection on Studies of Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design in Residential Area in China.” Landscape Architecture 25 (7): 47–52. https://doi.org/10.14085/j.fjyl.2018.07.0047.06.

- Markowitz, F., P. Bellair, A. E. Liska, and J. Liu. 2001. “Extending Social Disorganization Theory: Modeling the Relationships Between Cohesion, Disorder, and Fear.” Criminology 39 (2): 293–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2001.tb00924.x.

- Marzbali, M. H., A. Abdullah, N. A. Razak, and M. J. M. Tilak. 2012. “The Influence of Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design on Victimisation and Fear of Crime.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 32 (2): 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2011.12.005.

- Marzbali, M. H., A. Abdullah, N. A. Razak, and M. J. Tilaki. 2012. “Validating Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design Construct Through Checklist Using Structural Equation Modelling.” International Journal of Law Crime and Justice 40 (2): 82–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2011.08.005.

- Mateja, M., and G. Saville. 2021. “Third Generation CPTED the 4 S Principles for Liveability.” The ica newsletter: The international cpted association 17 (4): 15–17.

- Matzopoulos, R., K. Bloch, S. Lloyd, C. Berens, B. Bowman, J. Myers, M. L. Thompson. 2020. “Urban Upgrading and Levels of Interpersonal Violence in Cape Town, South Africa: The Violence Prevention Through Urban Upgrading Programme.” Social Science & Medicine 255:112978. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112978.

- Mihinjac, M., and G. Saville. 2019. “Third-Generation Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED).” Social Sciences 8 (6): 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8060182.

- Minnery, J. R., and B. Lim. 2005. “Measuring Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 22 (4): 330–341. https://doi.org/10.2307/43030751.

- Newman, O. 1972. Defensible Space. New York: Macmillan.

- Othman, F., Z. M. Yusoff, and S. A. Salleh. 2019. “Identifying Risky Space in Neighbourhood: An Analysis of the Criminogenic Spatio-Temporal and Visibility on Layout Design.” Environment-Behaviour Proceedings Journal 4 (12): 249–257. https://doi.org/10.21834/E-BPJ.V4I12.1908.

- Patino, J. E., J. C. Duque, J. E. Pardo-Pascual, and L. A. Ruiz. 2014. “Using Remote Sensing to Assess the Relationship Between Crime and the Urban Layout.” Applied Geography 55:48–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2014.08.016.

- Peeters, M. P., S. V. Daele, and T. V. D. Beken. 2018. “Adding to the Mix: A Multilevel Analysis of Residential Burglary.” Palgrave Macmillan UK(2) 31 (2): 389–409. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41284-017-0106-1.

- Peng, W. H., and L. Fu. 2023. “The Goals and Paths of Criminal Governance in the Context of Changes in Criminal Structure.” Journal of People’s Public Security University of China (Social Sciences Edition) 39 (2): 12–25. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=6zqdfgkTh_qwfbCmfKakXDaz_C-xskJejRaQ_sYHr88Nl1BR0pIwOvTvzrM3mg8Qrgcehw2g1HHZKCyZ2MYo0ohoTmjE5SJ7DP7aD6CPdIBdhZySqYefTJKEQQ7oXKc9TatXDyoImD7hQllU2PrjXA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

- Piroozfar, P., E. R. P. Farr, E. Aboagye-Nimo, and J. Osei-Berchie. 2019. “Crime Prevention in Urban Spaces Through Environmental Design: A Critical UK Perspective.” Cities 95:102411.1–.102411.11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102411.

- Qiu, J. P., J. C. Shen, and Y. H. Song. 2019. “Research Progress and Trend of Econometrics in Recent Ten Years at Home and Abroad-A Visual Contrast Research Based on Cite Space.” Journal of Modern Information 39 (2): 26–37. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=6zqdfgkTh_p9OpvngpJMatn48Gs_ZMNw3IkAT28ZPq44-L3fxTMQz4lVu868JCF2S53i8j_Tnv67o0AFFiaACPkJ819VKbslFqNQuVwn14aiNrUM_HMqFsUmCHMtmMG-V3fEb1O3lrCOKFfEnazPTw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.