ABSTRACT

Inspired by zero degree writing, this article questions inherited meanings carried through social practices in architecture. To do this, it overlaps Roland Barthes’s narrative codes with narratives of elements of floor and wall from Rem Koolhaas’s book entitled Elements of Architecture. The aim of the research carried out in the article is to reach an assessment regarding zero degree cycles of inherited meanings of architecture in the narratives of two mentioned elements in Koolhaas’s book. Methodologically, adapting Barthes’s 5 narrative codes to deconstruct the floor and wall narratives in the relevant book builds a bridge that enables to achieve “inherited meanings of architecture” revealed by social productivity. As a result of the methodology, 26 productive terms which can be interpreted as inherited meanings of architecture are revealed. Productive terms open up architectural meanings to interpretation by mediating their conveys through social production and by turning into a living inheritance. The use of Roland Barthes’ narrative codes in the deconstruction of an architectural text leads the article to an assessment of zero degree cycle of social productivity and reveals that architectural meaning is carried through social participation.

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical basis of research problem: zero degree of writing, and meaning-per architectural element

This article attempts to interpret hereditary meanings of architecture proceeding at zero degree by drawing inspiration from neutral writing. Rather than searching fictional and holistic meaning, it offers a study of how meaning remain inherited within social practices through architecture. For this purpose, it overlaps zero degree concept with two chosen micro-narratives in Rem Koolhaas’s book entitled Elements of Architecture using Roland Barthes’s narrative codes.

The philosopher Roland Barthes, in his book entitled Writing Degree Zero, writes about zero degree of interpretation as a neutral writing freed from pressure of fiction and style. At zero degree writing, by criticizing author’s fictional language he creates an utopia of writing that reconciles voice of reader with voice of author (Barthes, Lavers, and Smith Citation1967, Citation1977). Barthes questions author’s authority and argues that author must be aware of reader’s creativity and social participation (Barthes Citation1977; Hill Citation2003). While holistic meaning of text is in author’s fiction, analysis of text gives opportunity to examine social meanings and patterns hidden in text (Aktulum Citation2004; Barthes and Coverdale Citation2009).

Barthes’s narrative codes explaining the concept of “degree zero”, which are discussed in his book entitled S/Z, are paradigms that demonstrate how nested words in a narrative are linked along vertical axis. These codes are categorized as “action code”, “hermeneutic code”, “semantic code”, “cultural code”, and “symbolic code”. By means of codes, text ceases to be merely author’s voice in its semantic progression and captures social participation and productivity. In S/Z Barthes (Citation1974) has entirely analyzed Balzac’s book entitled Sarrasine published in 1830. He has developed two tools to carry deconstruction, which he referred to as “lexia” and “code”. A lexia is a part of text that can be from a few words to several sentences long and can be analyzed as “a unit of meaning”. Codes, whose names are mentioned above, are the categories into which lexias are divided. Barthes, at the end of the deconstruction, has segmented the entire text of Sarrasine into 561 lexias, in other words, 561 units of meaning, by means of these 5 codes (Tohar, Asaf, and Shahar Citation2007). While explaining each unit of meaning, Barthes (Citation1974) also captures productive essences associated with code and expresses them with words or phrases. These words or phrases are named “productive terms” in this article since they indicate productive essence. These codes, the units of meaning and the productive terms place meaning within a zero degree cycle of constant reproduction and reveals essence of production. In this way, they expose semantic flexibility at zero degree. In this article Barthes’s concept of “degree zero” and 5 narrative codes which their functionings will be detailed in the next section of the article, are methodologically functioned to examine inherited meanings of architecture.

Rem Koolhaas’s book Elements of Architecture,Footnote1 published in 2018, focuses on social functioning of 15 different architectural elements by delving into their micro-narratives. Since the elements are examined in depth throughout the book, Koolhaas describes the stories in the book related to the elements as “micro-narratives”. The book discusses the micro-narratives of architectural elements in different social sections and demonstrates how they are interpreted in different social dimensions in their historical evolutions (Koolhaas Citation2018). Each element transforms architectural system into a narrative pattern by entering into different semantic cycles created by society (Koolhaas, Harvard, and Trüby Citation2018). Based on the assumption that the micro-narratives in the book are, as Koolhaas claims, semantic cycles created by society, the book can be seen as a bridge for exploring inherited meanings of architecture embedded in the elements. The efficiency of the interpretation to be put forward by deconstruction in this article will bring us closer to the claim of the book and make it possible to comment on the progress of zero degree cycle in the micro-narratives in the book.

The 15 elements examined in separated sections in the book are “Floor”, “Wall”, “Ceiling”, “Roof”, “Door”, “Stair”, “Toilet”, “Window”, “Façade”, “Balcony”, “Corridor”, “Fireplace”, “Ramp”, “Escalator” and “Elevator”. This article studies two of the 15 elements discussed in the book, and these are chosen as “Floor” and “Wall”. The reason for choosing these two elements is that they are prioritized in Koolhaas’s book as two fundamental elements that are the most used as heritage in architecture and participate in social production the most. “Floor” section is located between pages 1–87, while “Wall” section is located between pages 88–205 of the book. In 205 pages of Koolhaas’s 2528-page whole book, it is explained how meanings of these two elements diversified in time.

1.2. Objective and importance of research

Methodizing Barthes’s concept of “degree zero” and 5 narrative codes, the article aims at reaching an assessment of hereditary meanings of architecture in the micro-floor and micro-wall narratives. In pursuit of this aim, productive terms revealed by deconstructing from the selected micro-narratives through methodology adapted from Barthes are crucial in terms of revealing social participation in conveying meanings of architecture and making them inheritance. The importance of Barthes’s methodology in terms of architecture lies in his attempt to reformulate author and reader by involving them in the process of creating meaning. Barthes’s methodology proposes an understanding in architecture being aware of social creativity (Hill Citation2003), and besides, it links architectural meanings to social and cultural environments (Crysler Citation2003). In this respect, Barthes’s methodology also mediates an assessment of inheritance accumulated by social participation and collective experiences, which the article aims at reaching. Considering that heritage is not just physical artefacts but a living social energy intertwined with traditional legacies and communities (Selim and Farhan Citation2024), it is possible to say that what keeps architectural heritage alive is social participation itself. What constitutes the importance and urgency of the issue discussed in the article is our responsibility towards the above-mentioned inheritance, its continuity and its convey to future generations. One should be aware that what conveys meaning to future generations by inheriting it should be social participation rather than individual and dominant authorities (Selim and Farhan Citation2024). Barthes’s methodology enables awareness of dynamic nature of inheritance accumulated through social participation in architecture. Understanding this dynamic nature can be considered as an act of resistance against cultural extinction and can reveal an intellectual approach that adopts mechanism of cultural resistance. It can also make it possible to build continuous collective productivity by proposing imagining of a pluralistic and inclusive society (Younus, Al-Hinkawi, and Lafta Citation2023). Considering dynamism in the accumulation and transfer of architectural heritage depending on speed and intensity of change of time and events, semiotic studies are flexible and convenient enough to analyze this dynamism. Semiotic methods enable seeing architecture as a fabric of signs governed by codes produced by community (Broadbent Citation1994; Geoffrey Citation1980 cited by Suprapti and Iskandar Citation2020). A number of semiotic studies have been conducted on different fields of architecture. This article analyzes the most fundamental meanings inherited by architecture through Barthes’s 5 narrative codes, and reveals how they are conveyed through architecture.

1.3. Scope of research

The article proceeds in 4 sections entitled “Introduction”, “Research Method”, “Research Result and Discussion” and “Conclusion and Recommendations”. The section entitled “Research Method” includes functioning of Barthes’s 5 narrative codes beside deconstruction steps of micro-floor and micro-wall narratives. In the section entitled “Research Result and Discussion” micro-narratives of floor and wall are segmented into their units of meanings with 5 codes and the productive terms revealed from the deconstruction by Barthes’s codes are discussed. It must be mentioned that since to deconstruct the entire pages of the book is not practical, some pages from the book have been selected to achieve the above-mentioned aim. The pages selected from the “Floor” section to be deconstructed are between the pages 4–7 of the book, where the introduction of the chapter entitled “Negotiating Between Gravity and the Upright Body”Footnote2 is located. The page selected from the “Wall” section to be deconstructed is the 91st page where the introduction of the chapter entitled “Wall”.

Koolhaas (Citation2018), who believes that each of architectural element carries long chains of DNA from the beginning of time on and that these interact with our contemporary evaluation, sheds light on inherited meanings of architecture in his book. By adapting Barthes’s methodology, which offers opportunity to examine 5 different social dimensions (by codes), to deconstruct the floor and wall narratives in Koolhaas’s book sections will built a bridge that will enable the article to achieve its aim, that is, “inherited meanings of architecture” that have been revealed by social productivity in time and are available for re-evaluation and production. In order to reveal a discourse demonstrating social productivity of the elements of floor and wall, this article methodically works with units of meaning developed from the concept of “lexia” in Barthes’s book. As a result of the deconstruction of the above-mentioned pages in the book, 32 units of meaning and 26 different productive terms will emerge through Barthes’s 5 codes. The revealing of these productive terms by benefiting from 5 codes, as the result of the article, will contribute to reveal the inherited meanings of these architectural elements. Based on the acknowledge that architectural meanings become permanent and inherited over time provided that they are produced through social participation, revealing social reproducibility in Koolhaas’s narratives will enable us to discover inherited meanings of architecture.

2. Research method

2.1. Functioning of 5 narrative codes

According to Barthes, semantic power of a narrative does not come solely from voice of author; narrative consists of pattern of different voices constantly changing direction, interweaving, or being interrupted by meaning. The 5 narrative codes that Barthes defines as the voice of empiric (action code), the voice of truth (hermeneutic code), the voice of person (semantic code), the voice of science (cultural code), and the voice of symbol (symbolic code) are paradigms that allow narratives to be approached from diverse perspectives. The first of these codes, the action code, is the voice of experiment that allows narrative to be seen as a story and a sequence of actions (ACT is the abbreviation of this code during the deconstruction in the article.). The hermeneutic code is the voice of truth that continues mystery and enigma in narrative (HER is the abbreviation of this code.). The semantic code is the voice of the characters that reflects their psychology (SEM is the abbreviation of this code.). The cultural code is the voice of science and refers to sorts of knowledge (CUL is the abbreviation of this code.). The symbolic code is the voice of symbol that includes contradictions in it and that are subject to multiple interpretations on a metaphorical level (Barthes and Miller Citation1974) (SYM is the abbreviation of this code.). If any narrative is approached through the operation of these 5 codes, productive realm where different meanings overlap appears. In this article traces of signifiers in the micro-floor and micro-wall narratives have been followed through Barthes’s codes, and signifiers have been segmented into units of meaning.

2.2. Deconstruction steps of micro-floor and micro-wall narratives

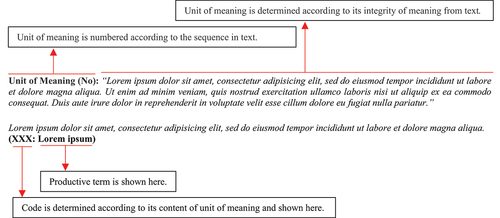

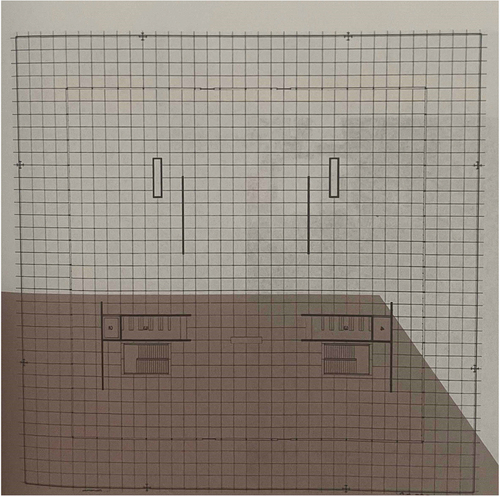

The narratives of the floor and wall in the selected pages of the book are deconstructed to reveal their productive terms at different semantic levels. In the process of deconstruction, units of meaning are determined according to their integrity of meaning and numbered according to their sequence in the text. In addition, both visual and textual signifiers in the text are accepted as unit of meaning and examined since they demonstrate the functioning of the text together. After unit of meaning is found, code corresponding content of unit of meaning is designated. One of the 5 codes must explain every single units of meaning. Finally, through this code, productive term within unit of meaning is specified. The sample shown in will help to follow the deconstruction in the article.

Textual interpretation, borrowed from Barthes’s methodology above, is a model that opens reading to experimentation. The steps in the article, respectively determining units of meaning, matching with codes and specifying productive terms, may carry risks of being limited to subjective interpretations. It should be taken into account that the interpretation in the article is made to point out plurality and efficiency of social productivity, with the acceptance that it may remain subjective and experimental. The three steps of deconstruction, which may also be done in other ways, are, as Barthes (Citation2009) stated, “an effort to move from monophonic to polyphonic composition”.

3. Research result and discussion

3.1. Deconstruction of micro-floor narrative in the chapter entitled “Negotiating Between Gravity and the Upright Body” (page 4, 5, 6 and 7 in the book)

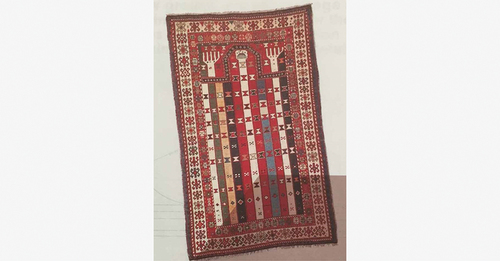

Unit of Meaning (1): Early 19th century, Guide to prostration: Akstafa prayer rug from Azerbaijan, featuring niche pattern, a reference to the mihrab in every mosque, which points towards Mecca, with stylized hand prints. (Easterling Citation2018, 4)

The first unit of meaning in the text is a visual signifier (see ). The cultural code works here. Prayer rug refers to common memory as religious iconography. The symbols on the prayer rug point to Mecca. It orients to Mecca in common memories. It has a semantic level conveyed ideas to Islamic culture and religion. In this unit of meaning the productive term is determined as “Iconography”. (CUL: Iconography)

Figure 2. Visual signifier of unit of meaning (1) (Source: Easterling Citation2018, 4).

Unit of Meaning (2): The floor is the customary technology for negotiating between gravity and the upright body. Every step is magnetized to its surface. It is the architectural element that is almost always touching the body. Floors can fall away or out from under, but they are usually there, idling beneath us. (Easterling Citation2018, 4)

This unit of meaning place itself under the action code. Gravity is the force which causes things to drop to floor, on the other hand floor has power to make them upright. It make bodies stand by its magnetic properties. Body becomes an instrument of movement on floor. Floor saves track of the upright body’s movement. Body transforms floor into an event scene. Under this unit of meaning “Body” is determined as productive term. (ACT: Body)

Unit of Meaning (3): Throughout most of its history, the floor has been a basic assumption, often a starting point. (Easterling Citation2018, 4)

This unit of meaning refers to common connotations of floor. Floor is assumed as the earliest limiting point, a point of commencement. A starting point commences something or act as a basis for this thing. This point reveals common knowledge. Starting point of common knowledge is floor. This unit of meaning can be enrolled under the cultural code which contains elements of common knowledge. “Starting point” placed in the unit of meaning is determined as productive term. (CUL: Starting point)

Unit of Meaning (4): Occasionally, it has been a place to display elaborate patterns and graphic story telling, or a surface reflecting mathematical fascinations like tessellation. (Easterling Citation2018, 4)

In this unit of meaning floor is characterized by exactness or precision of mathematics. Our thoughts tend to concentrate on its fascination. It can relate reasoning, numbers, patterns, and sequences, also represents abstract symbols and their relationships. There is a full agreement on its precision and its efficient function. This unit of meaning can be categorized under the cultural code with “Mathematical fascination” as productive term. (CUL: Mathematical fascination)

Unit of Meaning (5): But for eons, the floor was simply the surface of the earth or a technical, architectural response to make that surface more habitable or useful. (Easterling Citation2018, 4)

The emphasis on the fact that floor is defined, in this unit of meaning, through the ages by common technical knowledge is a harbinger of the cultural code. Floor can act as response to a question. It answers the question by its architectural technique. Architectural technique enables user participation by making floor habitable and useful. In this unit of meaning the productive term is determined as “Architectural technic”. (CUL: Architectural technic)

Unit of Meaning (6): It has also sometimes been a muted registration of cultural practices and construction technologies. (Easterling Citation2018, 4)

This unit of meaning continues to convey the common knowledge of the cultural code. Technology is interpreted as a tool for spreading cultural practices. It applies scientific advances to benefit culture’s practices to make them usual and familiar. In this unit of meaning the productive term is determined as “Technology”. (CUL: Technology)

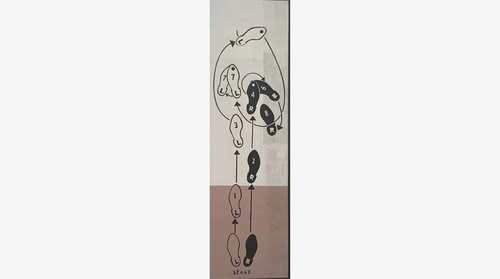

Unit of Meaning (7): 1962, Guide to pleasure: Andy Warhol’s Dance Diagram, 5 (Fox Trot: “The Right Turn – Man”). (Easterling Citation2018, 5)

Andy Warhol’s dance diagram in this unit of meaning indicates the action code (see ). It conveys that movements of dancing body penetrates into floor. Floor guides a motion or an action. It is the place to seek traces of pleasure. “Body” is determined as productive term of this unit of meaning. (ACT: Body)

Figure 3. Visual signifier of unit of meaning (7) (Source: Easterling Citation2018, 5).

Unit of Meaning (8): From prayer rugs to tatami grids to basketball courts, the floor has established a few presumed, if unspoken, rules of the game. (Easterling Citation2018, 5)

This unit of meaning contains an enigma within it because rules of the game played in floor may not formally articulated or understood. Floor creates rules of the game -even if not understood- that designates the participation of individuals. Here works the duality of the hermeneutic code. “Rule of game” is determined as productive term of this unit of meaning. (HER: Rule of game)

Unit of Meaning (9): A contemplation of architectural elements does not assemble an encyclopedia or reinforce a canon. It does the opposite. A prolonged look at each elements presents puzzles about cultural habituation – something like architectural why-stories that defamiliarize, even upset, conventions. (Easterling Citation2018, 5)

This unit of meaning implies that detailed analysis of architectural elements triggers puzzles and increases mystery. Mystery increases tension, unfamiliarity, confusion and uncertainty on floor, and triggers necessities to explore why behind itself. In this unit of meaning the hermeneutic code presents puzzles in order to make the reader involve into the text. “Puzzle” in this unit of meaning is determined as productive term. (HER: Puzzle)

Unit of Meaning (10): It may also expose a fatal error when a set of limited cultural habits have stiffened around the element, eliminating a whole range of techniques for making space. (Easterling Citation2018, 5)

The symbolic code in this unit of meaning invites the reader into the text with opposition and polyvalence within it. “Fatal error” - which is determined as productive term - demonstrates versatility of floor on a metaphorical level. Architectural element has a power capable of constituting a set of cultural habits and, on the other hand, can cause fatal consequences like rooting them out. (SYM: Fatal error)

Unit of Meaning (11): A contemplation of the floor returns to one of those forks in the road – territories sidelined in history that can become fresh projects for the discipline. (Easterling Citation2018, 5)

Forks in the road or sidelined territories expressed in this unit of meaning operates the mystery of the hermeneutic code. As much delving deeper about floor, unexplored or neglected narratives about it throughout history are revealed. The question of what these neglected sidelines are is left ambiguous and the reader is thus brought back into the text. The essence of the unit of meaning here, that is productive term, is “forks in road”. (HER: Forks in road)

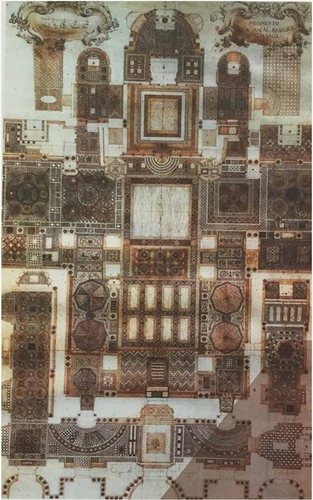

Unit of Meaning (12): 1725-1730, Floor plan of the mosaic at Saint Mark’s Basilica, Venice, painstakingly depicted by architect and painter Antonio Visentini (who systematically records Venice in his later collection Osservazioni of 1771). Visentini is the first to map Saint Mark’s 2,100 square meter mosaic, constructed by craftsmen from Constantinople (or Byzantine Greece), who covered the entire floor with geometric patterns made from marble and highly polished stone. (Easterling Citation2018, 6)

In this unit of meaning the cultural code progresses by emphasizing common value transmitted from the mosaic floor of Saint Mark’s Basilica (see ). Common value is revealed through a religious iconography. As the productive term is chosen “Iconography”. (CUL: Iconography)

Figure 4. Visual signifier of unit of meaning (12) (Source: Easterling Citation2018, 6).

Unit of Meaning (13): Luckily, the floor is then an element that has not been the subject of endless scrutiny and bombast in the discipline of architecture. Vertical surfaces are arguably favored as the canvas of an optical culture – a lens as well as a projection of mental constructs. (Easterling Citation2018, 6)

The implicative connotative level of the semantic code is at work in this unit of meaning. The fact that floor is not subjected to scrutiny and bombast implies that it is still a primitive architectural element. Moreover, primitiveness of horizontal floor is emphasized by stating that vertical surfaces are a more powerful tool used in visualizing culture. The productive term in this unit of meaning is agreed on as “Primitiveness”. (SEM: Primitiveness)

Unit of Meaning (14): The modern mind, elevating the human from cruder instincts, can keep afloat a number of immaterial constructs, but the heavy inevitabilities that it can no longer suspend must fall to the floor. (Easterling Citation2018, 6)

The connotative level of the semantic code is at work in this unit of meaning. Gravity is connotated by the expression “must fall” in the sentence. Gravity is such a universal force always directing downward (to floor) that modern mind cannot challenge with it. The productive term is determined as “Gravity” in this unit of meaning. (SEM: Gravity)

Unit of Meaning (15): Because the floor has often been regarded as an inert supporting player to the vertical, it has been, in a sense, free or wild. It is a reservoir of more primal or potent desires. It is also the untutored surface that escapes the dominant logics of a modern man. (Easterling Citation2018, 6)

The connotation of the semantic code operates in this unit of meaning. Floor might not be trained (since it is an untutored surface) even by dominance of modern mind. With its wildness floor evokes repository of primal desires. “Primal desire” is the productive term of this unit of meaning. (SEM: Primal desire)

Unit of Meaning (16): More recently, the floor has even been able to slip away, to gather intelligence and technology on the flip side of those logics, and it may now be returning to architecture for an important chapter in its history as something like an expressive software for space with enormous powers to shape building morphology. (Easterling Citation2018, 6, 7)

There is a transition, in this unit of meaning, to the cultural code indicating common knowledge. Floor may work as a software telling what to do, in the meantime it conveys thoughts or feelings (since it is expressive). The productive term in this unit of meaning is designated “Technology”. (CUL: Technology)

Unit of Meaning (17): But that is just one of many unexploited capacities of the floor – an element for the “non-modern” man. (Easterling Citation2018, 7)

The opposition of the symbolic code operates in this unit of meaning. Opposition created by non-modern man tends to search out the unexamined side of floor against normative principles. This negative statement allows the reader to question not-yet discovered aspects that are not in the totality of meaning. “Non-modern man” is determined as productive term in this unit of meaning. (SYM: Non-modern man)

Unit of Meaning (18): 1963-8, Emptiness: plan of the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, by Mies van der Rohe. As well as typical architectural details of the plan, like walls (just four of them, made of glass) and columns, (also just four major ones), Mies decides to draw the pattern of the floor itself, without which the emptiness of the drawing might be unreadable as a plan of occupiable space. The floor grid consists of 3,136 tiles, forming a surface that extends beyond the glass walls, claiming the area under the extended roof as floor too. (Easterling Citation2018, 7)

The polyvalence of the symbolic code starts in this unit of meaning (see ). “Emptiness” is caught as productive term. Mies Van Der Rohe makes free space on floor defined by drawing a tile grid on it. Grid exceeds even interior space in plan as seen. This brings a definition to trace of roof as well. If he would not draw this tile grid, emptiness in floor would not be able to read as an occupiable space, according to him. Coexistence of emptiness and void gives plan multivalence. (SYM: Emptiness)

Figure 5. Visual signifier of unit of meaning (18) (Source: Easterling Citation2018, 7).

3.2. Deconstruction of micro-wall narrative in the chapter entitled “Wall” (page 91 in the book)

Unit of meaning (19): The meaning of the wall is just as diverse as the uses of vertical surface can be, but there are at least two essential functions: providing structure and dividing space. The two can be separated, and thus the category of “wall” divides into two: the bearing wall, separating roof from ground; and the partition wall, organizing movement within the resulting container. The former, it would seem, is as stable as the human need for shelter; the latter as changeable as our forms of sociability. (Koolhaas, Harvard, and Trüby Citation2018, 91)

This unit of meaning categorizes elementary meanings of wall regarding its divisive ability. By initiating a sequence of events, from “separation of roof from floor” to “organizations of movement on floor”, it emphasizes wall’s relation to movements of user. Therefore, the action code operates in this unit of meaning with productive term of “Division”. (ACT: Division)

Unit of meaning (20): If we follow Gottfried Semper’s hypothesis, which type of wall came first is somewhat counterintuitive. Semper declared the archetype of the wall as the hanging fabric of the tent or temporary pavilion. The solid walls – of mud, stone, wood, brick – that came to supplement these temporary barriers arrived only later, Semper argued, to make permanent the achievement of the temporary wall, which was to define community via a symbolic membrane. The social and symbolic is seen as primary, suggesting a wall that is as dynamic as the humans that it is meant to contain. (Koolhaas, Harvard, and Trüby Citation2018, 91)

In this unit of meaning, based on Gottfried Semper’s archetype of the wall, an antithesis is put forward and the symbolic code is operated. Fame of temporary wall produced with tentative materials such as hanging fabric or tent is grounded to social and symbolic meanings that it brings out to society. This unit of meaning causes wall to earn polyvalence. “Temporary barrier” is chosen as productive term. (SYM: Temporary barrier)

Unit of meaning (21): The key place given to decoration in Islamic architecture, where it suggests an infinitely expansive pattern that both defines the structure and exceeds it, may suggest something like this sensibility. (Koolhaas, Harvard, and Trüby Citation2018, 91)

In this unit of meaning, it is emphasized that a decorative pattern on the wall both defines the wall’s structure and may exceed the wall due to its expanding appearance. There is a reference to unlimited faith by means of pattern in Islamic architecture. Iconography in Islamic architecture operates the cultural code by referring to a common memory. The productive term in this unit of meaning is determined as “Iconography”. (CUL: Iconography)

Unit of meaning (22): while the shoji of the Japanese interior epitomize the dynamic function of the wall-as-partitions. (Koolhaas, Harvard, and Trüby Citation2018, 91)

This unit of meaning is operated with the polyvalence of the symbolic code. Shoji in Japanese Architecture is a translucent and sliding wall-as-partition consisting of a wooden frame covered in rice paper. When slid and opened it opens interior space outside. It dynamically functions in both usage. The productive term is agreed on as “Dynamic function”. (SYM: Dynamic function)

Unit of meaning (23): But in Europe the pressures of warfare and growing wealth enshrine monumentality and permanence as the wall’s defining traits. (Koolhaas, Harvard, and Trüby Citation2018, 91)

In this unit of meaning, the implying connotation level of the semantic code is operated. -As distinct from the Japanese Architecture- power and wealth played a role in the being monumental and permanence of the wall in Europe. “Wealth” is decided as productive term in this unit of meaning. (SEM: Wealth)

Unit of meaning (24): Seen in time-lapse, the history of the world’s architectural plans would be the history of changing forms of civilization, as new segmentation of space is demanded by new forms of society. The single-room house or collective hall, with occupants huddled in common space (probably around a central fireplace), gives way to ever more complex configurations of boxes within boxes. Increasing standards of modesty and individualism demand new walls around new bedrooms; new family norms even divide off the nursery. (Koolhaas, Harvard, and Trüby Citation2018, 91)

In this unit of meaning the event pattern of the action code is in operation. When the history of world architectural plans is examined, it can be seen that social requests alters wall’s ability to be a divider, and eventually bring it on a complex configurations. Divisiveness of wall is a result of social movement. The productive term in this unit of meaning is determined as “Division”. (ACT: Division)

Unit of meaning (25): At the same time, more egalitarian sensibilities, as well as the scarcity of space in growing cities, press back, breaking down walls: while the parlor emerges in Victorian society as a new formal space for entertaining, by the 1920s, it is absorbed into the less formal, multi-use living room, a mutation of the Victorian “stairhall”. (Koolhaas, Harvard, and Trüby Citation2018, 91)

This unit of meanings signals the action code. It is exemplified here that wall is not only exposed to political and economic influences, but also influenced by social sensibilities. “Parlor” as a formal space for entertainment transforms in time into a less formal “living room” by means of social changing of usage of walls in space. Egalitarian movements of Victorian society lead to openness of entertainment space. “Openness” is chosen as productive term in this unit of meaning. (ACT: Openness)

Unit of meaning (26): “All that is solid melts into air”, Marx and Engels wrote in 1848, observing the mutations brought on by capitalism. Almost 70 years later, Franz Kafka writes in “The Great Wall of China”: “Human nature, essentially changeable, as unstable as the dust, can endure no restraint; if it binds itself it soon begins to tear madly at its bonds, until it rends everything asunder, the wall, the bonds, and its very self.” Kafka’s parable about the Great Wall looked back to the most spectacular effort of a fantasized “Oriental despotism” to suggest an allegory for the anxieties of the modernizing present, with its inscrutable forces reordering space and time. In Kafka’s time, the solid architectural wall was melting away under the pressure of modern bureaucracy, which required multiple walls, whose flimsiness and complexity was just as dubious as the solid walls of old-fashioned despotism. (Koolhaas, Harvard, and Trüby Citation2018, 91)

In this unit of meaning, wall and destruction form an antithesis. The idea of a solid architectural wall disintegrates and evolves into multiple flimsy and complex walls. Human beings, on the other hand, may display destructive qualities within confines of wall. The opposition of the symbolic code brings border and destruction together. The productive term here is “Destruction”. (SYM: Destruction)

Unit of meaning (27): But even an absence of walls can be an operation of power. The structured interior has given way to the open plan, inspired by another imagined East – the Japanese pavilion glimpsed by Frank Lloyd Wright at the World’s Columbian Exhibition of 1893, in Chicago. A simplified simulation, that exhibit was, in fact, more ostentatiously open than any real Japanese house: the partitions were removed to allow easy inspection of the space by the Western viewer. (Koolhaas, Harvard, and Trüby Citation2018, 91)

The connotation in semantic code is operated in this unit of meaning. In Japanese Pavilion at the World’s Columbian Exhibition, Frank Lloyd Wright exhibits the idea of open plan by being removed partitions with a more ostentatious representation than any traditional Japanese house. The productive term is determined as “Open plan” in this unit of meaning. (SEM: Open plan)

Unit of meaning (28): The demands of Chicago’s frontier construction would also yield up the ultra-light gypsum fireproof panel, the precondition to build at the new scales and depths demanded by the 20th century’s big buildings. With the advance of technology, the wall, no matter how temporary or flimsy, becomes more and more permeated with wiring and plumbing, insulation and acoustic engineering, even as outwardly it becomes devoid of decoration, bare, even transparent. (Koolhaas, Harvard, and Trüby Citation2018, 91)

Cross-sectional change of wall is indirectly associated with social movements in this unit of meaning. Wall, which becomes lighter and more transparent, commences to incorporate technological developments related to acoustics and insulation. This unit of meaning is enrolled under the action code with productive term “Changing in section”. (ACT: Changing in section)

Unit of meaning (29): Folding screens and plastic partitions replace fixed partition walls in rec rooms, conference centers and synagogues to keep pace with the frantic reconfigurations of a society that can’t stop moving. (Koolhaas, Harvard, and Trüby Citation2018, 91)

The movement pattern of the action code progresses in this unit of meaning. Frantic desires of society to reconfiguration triggers wall’s transformation. “Reconfiguration” is agreed on as productive term. (ACT: Reconfiguration)

Unit of meaning (30): At last it is in the office where the dream of the solid wall as modular accessory emerges and then runs aground. During the libidinal 1960s the United States’ high-tech capitalism yields up the ultimate device of light-weight enclosure: the office cubicle. Like many epoch-making design innovations, this one is conjured up by a progressive vision. Openness was not a virtue but an economic necessity for the office workers of the early 20th century, who toiled in intellectual spaces configured like cavernous factories. For these clerks and secretaries, openness signalled a lack of individuality; managers were lucky to have their own offices, their own walls. The cubicle claimed dignified private space for employees within the open sea of productivity. (Koolhaas, Harvard, and Trüby Citation2018, 91)

This unit of meaning progresses narrative with the action code. Openness in space legitimized as an economic necessity contains a lack of individuality as well in it. Therefore light-weight enclosure cabins begin to be generated. “Openness” is revealed as productive term. (ACT: Openness)

Unit of meaning (31): Today, forgetting the cubicle’s origins as an ennobling device and hating what it has become, the open plan office is back as the fig leaf of progressive corporate culture, though studies show that employees once again miss their privacy and maybe even want a few solid walls back in the picture. (Koolhaas, Harvard, and Trüby Citation2018, 91)

The connotation level of the semantic code operates in this unit of meaning. It is implied that walls in open plan offices are a sign of privacy. As productive term is determined “Privacy”. (SEM: Privacy)

Unit of meaning (32): The time-lapse fluctuation of our societal floor plan has accelerated. Now you can almost watch the walls go up and down in real time. (Koolhaas, Harvard, and Trüby Citation2018, 91)

As seen in the analysis of the fluctuated history of the wall, on the one hand it rises for permanence, and on the other hand it descends for transience and flexibility. To go up and down integrates the opposition and multivalence of the symbolic code into the text. “Go up and down” is chosen as productive term of this unit of meaning. (SYM: Go up and down)

3.3. Productive terms at zero degree in micro-narratives, and inherited meanings of architecture

Barthes’s methodology has enabled the discovery of the productive terms embedded in the selected texts. These terms are assumed to make social participation visible. The selected texts have focused on the narratives of architectural elements that operate through social cycles, as Koolhaas claims. The productive terms discovered are crucial to the article in the sense that they have potential to represent inherited meanings of architecture, and are explained respectively in below.

Table 1. Productive terms produced from micro-floor and micro-wall narratives.

The action code, according to Barthes (Citation1974), is the voice of empiricism that allows any narrative to be seen as a sequence of experimental actions. For this reason, meanings that motivate actions have been decomposed in the selected texts while deconstructing. Body, Division, Openness, Changing in section and Reconfiguration are the productive terms having been demonstrated through this code. Body is a productive term that initiates movement and activates events in the space. Division is a productive term that describes division of wall according to forms of socialization. Openness is a productive term that refers to removal of wall in houses and offices as a result of reflection of egalitarian movements. Changing in section is a productive term that advances the narrative by demonstrating how social movements bring about cross-sectional changes. Reconfiguration is a productive term that indicates usage of wall partitions that stimulates society’s desire to reconstruct. These productive terms gathered under the action code express the relationship between architectural elements and social movements. They can be evaluated as inherited meanings of architecture produced by social movements embedded in the micro-narratives.

Under the hermeneutic code which is described by Barthes (Citation1974) as the voice of truth that continues mystery and enigma in narrative, Rule of game, Puzzle, Forks in road as productive terms pose riddles that involve the reader into production of architectural element’s meaning. While deconstructing, it has been questioned whether any mystery or riddle was expressed in the narratives; they were detected in the floor narratives, but not in the wall narratives. Rule of game is a productive term that questions freedom of daily life and normative rules of floor. Puzzle is a productive term that adds the reader to the narrative by activating a gaze that turns floor into a puzzle. Forks in road is a productive term that keeps alive the question that there will be always undiscovered meanings and crossroads throughout history. Mysteries and riddles in the hermeneutic code provide social participation with their interrogative aspects. The productive terms gathered under this code can be considered as hereditary meanings formed by inquisitive aspect of society.

The semantic code is evaluated by Barthes (Citation1974) as the voice of person that reflects the characters and their psychology in any text. While deconstructing in this code, it has been questioned dominant individual connotations in the narratives; and Primitiveness, Gravity, Primal desire, Wealth, Open plan and Privacy are found as the productive terms that indicate psychology of characters, and imply connotations of architectural elements. The productive term of Primitiveness inherits primitive use that is not subject to ostentation. Gravity is a productive term that implies natural power confronting modern mind. Primal desire is a productive term that describes use of floor that keeps primitive desires of individuals alive. The productive term of Wealth refers that permanence of wall turns into a display of wealth. Open plan is a productive term inherited from Japanese tradition, evoking freedom in plan. The productive term of Privacy shows transformation of walls into privacy indicators in open plan offices. These productive terms captured by tracing individual meanings under the semantic code can be counted as inherited meanings embedded in the micro-narratives.

The cultural code is the voice of science and refers to sorts of knowledge according to Barthes (Citation1974). Under this code Iconography, Starting point, Mathematical fascination, Architectural technic and Technology as the productive terms have gathered from the texts. Under the cultural code expressions used in establishment of the relationship between cultural authorities and social thinking have been questioned in the selected texts. Iconography points to common knowledge by demonstrating religious symbols in the micro-narratives. Starting point is the productive term that refers origin point of common knowledge which has been inherited from the beginning of time to today through floor. The productive term of Mathematical fascination implies a heritage embedded in floor from the past on through common reasoning, numbers, patterns and sequences. The productive term of Architectural technic has come from past to present by emphasizing common technical knowledge. Technology is a productive term that encompasses scientific developments within cultural practices in the selected architectural elements. It is possible to evaluate these productive terms revealed in the cultural code as hereditary meanings produced by common knowledge embedded in the micro-narratives.

The symbolic code is described by Barthes (Citation1974) as the voice of symbol that includes contradictions in it and that are subject to multiple interpretations on a metaphorical level. Under this code, Fatal error, Non-modern man, Emptiness, Temporary barrier, Dynamic function, Destruction and Go up and down are the productive terms that indicate contrasts and polyvalence in the micro-narratives. Under the symbolic code, expressions showing neutrality along with binary oppositions and polyvalence in the text are collected. Fatal error is a productive term that enables objective evaluation of floor narratives with the emphasis on fatal consequences occurred in cultural habits. The productive term of Non-modern man is a neutral productive term that brings into question unexamined aspect of floor against normative principles. The productive term of Emptiness refers to transformation of emptiness on floor into an occupiable space in Mies Van Der Rohe’s plan drawing. The productive term of Temporary barrier, which is inherited from Gottfried Semper’s wall archetype, emphasizes temporality of wall that gains polyvalence with social and symbolic meanings. The productive term of Dynamic function emphasizes that use of sliding, semi-translucent glass inherited from Japanese architecture brings dynamism to life. Destruction as a productive term adds a point of view showing that destructive qualities can be displayed within boundaries of wall. The productive term of Go up and down adds an polyvalent perspective to wall by emphasizing its fluctuating history. The productive terms gathered in this code enable the reader to evaluate the text impartially thanks to the polyvalence and contradictions in them.

4. Conclusion and recommendations

The research in the article includes, on the one hand, a motivation regarding to reach hereditary meanings of architecture, and on the other hand, another questioning about whether these meanings operate in a zero degree cycle. The methodology that brings both motivations to life is Barthes’s 5 narrative codes. With the assumption that the 5 codes used in Barthes’s methodology will lead us to inherited meanings of architecture embedded in the texts selected from Rem Koolhaas’s book “Elements of Architecture”, it has been questioned whether the architectural elements in which these meanings are embedded operate within zero degree cycle, that is, within social productivity. In the text where micro-floor narratives were examined, it has been realized that the 5 codes operated together, that there was zero degree social productivity cycle, and that other voices were woven in addition to author’s voice. In the text selected from the micro-wall narratives, it was observed that there was no hermeneutic code, but the other four codes operated together. This situation can be interpreted as the selected text not being able to entirely open up to social productivity and the questioning side of the wall being missing. On the other hand, the layers of meaning of the productive terms revealed through the other four codes could be interpreted through the social production of the wall.

Interpreting Koolhaas’s micro-narratives through the way that Barthes follows has also been an opportunity to evaluate together two above-mentioned motivations that led to the emergence of the article. The inherited meanings of architecture become permanent with social productivity and are carried as inheritance over time. The inherited meanings of architecture embedded in the floor and wall narratives in the texts were revealed by the productive terms in this article. The resulting 26 different productive terms are inherited for architecture and are still questionable today. Rather than being personal and holistic, these meanings are codes that extend from past to present, are continuous, and allow for reproducibility by being transformed by social practices. They form a huge range, from prehistoric times to metropolitan cities. For architecture tired of superficial forms, zero degree interpretation enables a return to heritage codes adapted to social language (Zevi Citation1978). The attempt to decipher the inherited meanings of architecture embedded in the selected texts based on zero degree interpretation and 5 narrative codes has also proven the efficiency of the interpretation that can be extracted from any text examining origins of architecture. Deconstructing other sections or other architectural elements in Rem Koolhaas’s book, or retrying the process carried out in this article by other researchers, may multiply the hereditary meanings of architecture, and these meanings may reach a level that can be reinterpreted in contemporary world.

Barthes’s methodology has been effective in interpreting inherited meanings of architecture that are aimed to be reached in the article. His concept of “degree zero”, by questioning singular and fictional meaning created by author’s authority, directs the article to meanings interpreted and conveyed through social participation. In his works, Barthes demonstrates signs as phenomena whose meanings are constantly carried within a social performance area, that is, he never places them in fixed shelters. In this research made in the field of architecture the use of this methodology, which is effective in the field of literature and semiotics, has revealed that creativity is not a concept handled by merely architect, and that social participation and productivity are effective in creating and conveying architectural meaning. Positioned at the intersection of architectural semiotics, architectural elements and architectural heritage, this research has revealed a unique perspective that combines these issues. In order to implement the article’s findings and sustain their impacts, it is important to engage with these three study groups. The findings of the article draw attention to architects’ role in implementation of inherited meanings of architecture. Considering that inherited meanings are in intense relations with today’s life and that social reproducibility is too intense to fall under architect’s authority, inherited meanings guide architects to reach architectural meanings that are spontaneously produced and carried by society. In the article, these meanings are discussed in a way that can be interpreted and maintained in future. Thus, meaning as inheritance reaches the potential of being carried to future rather than merely coming from past. This strengthens our responsibility to convey embodied inheritance to future generations.

It is seen that studies dealing with Barthes’s semiotic approach in architecture mostly focus on cultural and symbolic connotations through structures. This research, unlike others, has discussed the narratives of micro-floor and micro-wall within Barthes’s approach, and it has pointed out that meaning is conveyed through social productivity on these two architectural elements. When it is realized that architectural meaning evolves and is carried in the examined floor and wall narratives, global, holistic and standard understandings in architecture can be transformed into more fragmented, local and individual ones. The fact that inherited meanings are open to transformation through social experience and participation may encourage formation of new understandings in architecture. Despite the difficulty of evaluating the concept of social participation because it is speculative, contingent and situational, Barthes’s 5 narrative codes have made possible a classification in which this evaluation can be made.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank YÖK 100/2000 Ph.D. Scholarship Programme.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Türkan Ceylan Ünal Baştürk

Türkan Ceylan Ünal Baştürk is currently enrolled as a PhD student at Yıldız Technical University, Faculty of Architecture in Istanbul, Turkey. Major research interests include architectural theory, urbanism, and semiology. She aims at reaching inherited meanings of architecture through deconstructing architectural narratives.

Ş.Tülin Görgülü

Ş. Tülin Görgülü currently works as a professor at Yıldız Technical University, Faculty of Architecture in Istanbul, Turkey. Major research interests include housing and typologies, architecture design theories, and urban design.

Senem Kaymaz

Senem Kaymaz is currently on a one-year sabbatical leave as an academic visitor at Technical University of Berlin, Institute for Architecture, Department of Architectural Theory in Berlin, Germany. She works as an associated professor at Yıldız Technical University, Faculty of Architecture in Istanbul, Turkey. Major research interests include architectural design approaches, architectural critical theories and architectural epistemology.

Notes

1 The book entitled Elements of Architecture has been developed from the works of the 14th Venice Biennale in 2014 with the theme “Fundamentals” curated by Rem Koolhaas. Based on the works in the Biennale it was authored by Rem Koolhaas, AMO and Harvard Graduate School of Design with the contribution of James Westcott, Stephan Petermann, Stephan Trüby, Irma Boom, Manfredo di Robilant, Tom Avermaete, C-Lab, Jeffrey Inaba, Benedict Clouette, Keller Easterling, Jiren Feng, Niklas Maak, Sebastian Marot, Kevin McLeod, Friedrich-Mielke-Institut für Scalalogie, Hans Werlemann, Alejandro Zaera Polo and Fang Zhenning. The book has been published in 2018 after 4 years from the Biennale.

2 This section is authored by Keller Easterling.

References

- Aktulum, K. 2004. Parçalılık/Metinlerarasılık (in Turkish). Ankara: Öteki Yayınevi.

- Barthes, R. 1967. Writing Zero Degree. Translated by A. Lavers and C. Smith. London: Jonathan Cape. ( Originally published 1953).

- Barthes, R. 1974. S/Z. Translated by R. Miller. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. ( Originally published 1970).

- Barthes, R. 1977. “The Death of the Author.” In Image-Music-Text, edited by R. Barthes translated by S. Heath, 142–148. London: Fontana Press. (Originally published 1968).

- Barthes, R. 1977. Elements of Semiology. Translated by A. Lavers and C. Smith. New York: Hill & Wang. ( Originally published 1964).

- Barthes, R. 2009. The Grain of the Voice: Interviews 1962–1980. Translated by L. Coverdale. Evanston Illinois: Northwestern University Press. ( Originally published 1981).

- Broadbent, G. 1994. “Recent Developments in Architectural Semiotics.” Semiotica 101 (1–2): 73–102. https://doi.org/10.1515/semi.1994.101.1-2.73.

- Crysler, C. G. 2003. “From Zero Positions to Assemblage.” In Writing Spaces: Discourses of Architecture, Urbanism and the Built Environment, 1960–2000, edited by C. G. Crysler, 50–52. New York: Routledge.

- Easterling, K. 2018. “Floor: Negotiating Between Gravity and the Upright Body.” In Element of Architecture, edited by R. Koolhaas, G. Harvard, and S. Trüby, 1–81. Köln: Taschen.

- Geoffrey, B. 1980. Sign, Symbol and Architecture. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Hill, J. 2003. Actions of Architecture: Architects and Creative Users. New York: Routledge.

- Koolhaas, R. 2018. “Elements: A Brief History.” In Element of Architecture, edited by R. Koolhaas, G. Harvard, and S. Trüby, XLII–LI. Köln: Taschen.

- Koolhaas, R., G. S. D. Harvard, and S. Trüby. 2018. Elements of Architecture. Köln: Taschen.

- Selim, G., and S. L. Farhan. 2024. “Reactivating Voices of the Youth in Safeguarding Cultural Heritage in Iraq: The Challenges and Tools.” Journal of Social Archaeology 24 (1): 58–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/14696053231224037.

- Suprapti, A., and I. Iskandar. 2020. “Reading Meaning of Architectural Work in a Living Heritage.” IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, The 3rd International Conference on Sustainability in Architectural Design and Urbanism, 012023, Volume 402, Indonesia. 29–30 August 2019. https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/402/1/012023.

- Tohar, V., M. Asaf, and A. K. R. Shahar. 2007. “An Alternative Approach for Personal Narrative Interpretation: The Semiotics of Roland Barthes.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 6 (3): 57–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690700600306.

- Younus, I., W. Al-Hinkawi, and S. Lafta. 2023. “The Role of Historic Building Information Modeling in the Cultural Resistance of Liberated City.” Ain Shams Engineering Journal 14 (10): 102191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asej.2023.102191.

- Zevi, B. 1978. “Prehistory and the Zero Degree of Architectural Culture.” In The Modern Language of Architecture, edited by B. Zevi, 219–233. Canberra: ANU Press.