?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

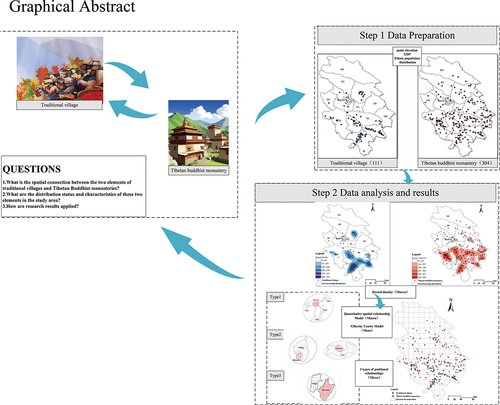

As a typical religious cultural heritage, Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region of northwest China have strong connections with surrounding villages that practice Tibetan Buddhism. This article investigates the spatial distribution correlation between the two entities using methods such as kernel density, spatial quantity relationship model, gravity center model, and qualitative description. It analyzes the relationship between Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and traditional Tibetan villages at three levels: macro, meso, and micro, exploring the spatial correlation and influence factors. The study results are as follows: Firstly, the spatial distribution of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region exhibits a positive correlation with a moderate spatial correlation. Secondly, the distribution of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region demonstrates a high spatial balance. Yet, there are instances where certain counties have an abundance of monasteries but lack traditional villages, particularly in Minhe County, Guide County, Hualong County, and Ledu County. Various factors such as economic, policy, and cultural integration contribute to this phenomenon. Thirdly, the location relationship between traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region can be categorized into three types: Villages separated from Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in villages, and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries near villages. Finally, it is proposed to protect traditional villages in the area based on the principle of protecting cultural diversity. To safeguard Chinese traditional villages in the future, it is essential to comprehensively analyze the spatial relationship between villages and religious architectural heritage, and prioritize the preservation of significant villages located within the influence zone of these religious architectural heritage by incorporating them into the list of protected traditional villages. This study aims to enhance theoretical research on traditional villages in ethnic minority regions and provide a scientific basis for the comprehensive protection and coordinated utilization of traditional villages and religious architectural heritage in the Hehuang region and other ethnic regions.

1. Introduction

Traditional villages in China are a significant part of the country’s cultural heritage, highlighting the unique society, culture, and customs of different regions. These villages also stand as a testament to China’s enduring agricultural civilization that has spanned thousands of years (Xiang et al. Citation2022). In recent times, the Chinese government has placed great emphasis on the preservation and promotion of rural history and culture as part of the comprehensive rural revitalization strategy (Xu and Zhou Citation2023). The Hehuang region is situated in a significant geographical transition zone between the Loess Plateau and the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, known as the Hehuang Ethnic Corridor. It serves as a meeting point for three key geographical regions: the Tibetan alpine region, the eastern monsoon region, and the northwest arid inland region. This region plays a crucial role in linking the Central Plains of China with sub-regions like the Tibetan Plateau and the Mongolian Plateau (He and Zhou Citation2023). Historically, the cultures of Tibetan Buddhism, Islam, and Confucianism were interwoven and integrated in the Hehuang region, creating a unique local culture and rural landscape. This region, where multiple ethnic groups coexist, is influenced by both its geographical setting and multiculturalism. Tibetan Buddhist monasteries are intricately linked with the traditional villages in the area, showcasing cultural migration. In 2022, we participated in the application process for the sixth batch of traditional villages in Xunhua County, located in the Hehuang region of China. Through field research, it was discovered that Tibetan Buddhist temples, as cultural heritage representative of China’s ethnic minorities, exhibited close spatial ties with neighboring villages amidst cultural migrations. The symbiotic relationship between villages and temples, rooted in religious culture and materialized in physical spaces, forms a unique charm among ethnic minorities on both the socio-cultural and architectural levels, preserving a distinct cultural heritage (Shi and Jin Citation2021). Traditional villages act as cultural sanctuaries, carrying forward centuries-old traditions. A comprehensive comprehension of the connection between traditional villages and the spatial arrangement of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries holds immense importance in safeguarding the characteristic culture of ethnic minorities and ensuring the continued legacy and sustainable growth of traditional villages.

The academic community has extensively researched the spatial distribution of traditional villages and religious buildings, with studies spanning the entire country (Chen et al. Citation2018; Fang et al. Citation2023), the Yellow River Basin (Xue et al. Citation2020), the southwest region (Wang et al. Citation2021), the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region (Tian Citation2020), the northwest region (X. Huang et al. Citation2018), and various provinces and cities (Huang et al. Citation2024; Li et al. Citation2015). These studies have examined spatial distribution characteristics at multiple scales. Research methods utilize quantitative techniques such as kernel density, center of gravity model, proximity index, and spatial autocorrelation at the macro and meso levels. At the micro level, researchers often focus on analyzing and discussing specific cases, including the spatial distribution and morphological characteristics of villages and religious buildings (Chen, Li, and Wang Citation2023). Foreign scholars focus on the interactive relationship between monasteries and communities, suggesting that the selection and organization of residential spaces are influenced not only by the natural geographical environment but also by cultural, social, religious, and other factors (Eliade Citation1959). Tibetan Buddhism significantly impacts rural areas in Tibetan regions, where the political and religious governance system has closely linked Tibetan Buddhist monasteries with rural settlements. Since the 19th century, scholars such as H. R. Davis, Joseph Charles Francis Rock, and Sven Hedin have extensively explored Tibetan areas in China, documenting their experiences through travel notes, diaries, and reports. They focused on observing both natural landscapes and social conditions. Some researchers have taken a more detailed approach by studying specific settlements to investigate the interconnectedness between Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and the surrounding communities. Paul Kocot Nietupski proposed a “Tibetan-style interactive sacred and secular” social system through an analysis of the regulations of the Labrang Monastery in China and the social characteristics of the hidden area (Su Citation2013). Ortner utilized anthropological theoretical methods to examine the support relationship between monasteries and surrounding communities in China’s Sherpa community (Ortner Citation1989). Chinese scholars have delved into research on various aspects of Tibetan Buddhism, such as its history(Lha Citation2022; Pu Citation2000), the distribution of Buddhist monasteries (Peng et al. Citation2023; Xiao and Huang Citation2020; Zhu et al. Citation2019), the architectural functions and spatial characteristics of Buddhist monasteries (Wang Citation2023; Wang et al. Citation2023; Zou and Bahauddin Citation2024), and the spatial distribution along with the influencing factors of traditional villages (Lai, Chen, and Sun Citation2020). Based on these studies, they have proposed various methods and strategies for the protection of cultural heritage in China from different perspectives (Li and Zhang Citation2023; Tang et al. Citation2021; Yue and Li Citation2023). Overall, most relevant scholars have conducted independent studies focusing on the spatial distribution of traditional villages or Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, lacking a thorough exploration of the associative relationships between their spatial distributions. Notably, the spatial distribution of traditional villages in ethnic minority regions is significantly influenced by belief culture. In the Hehuang region, Tibetan Buddhist monasteries serve as the focal point of belief for villages that adhere to Tibetan Buddhism, functionally interacting with villagers’ daily lives and providing them with religious and cultural identity. Therefore, the preservation of traditional villages in ethnic minority regions should not only emphasize the protection of material spaces but also the importance of safeguarding cultural and belief spaces.

Currently, the identification criteria for traditional Chinese villages are primarily based on the village as the fundamental unit. Field research is conducted to determine whether the village possesses historical significance, notable individuals, scenic spots, historical relics, non-material cultural heritage, and folklore. Notably, in the Hehuang region, there exists a mutual relationship between religious architectural heritage and villages adhering to Tibetan Buddhism, with religious buildings exerting significant influence on villagers’ daily production and life. From the perspective of administrative boundaries, religious buildings are not always located within villages, yet they play a crucial role in the expansion and development of these villages. Once a village is included in the list of traditional Chinese villages, the Chinese government provides funding and policies to protect these villages, thereby contributing to the sustainable development of traditional villages in the region.

Therefore, this study contributes in the following ways: it focuses on the distribution patterns of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region, two types of cultural heritage. By attempting to reveal the spatial distribution characteristics, relationships, and influencing factors between them, it enriches the relevant theories of traditional village protection in ethnic minority areas of China. This research aims to provide scientific evidence for the future identification of traditional Chinese villages and the preservation of traditional villages and religious architectural heritage in the Hehuang region as well as other ethnic minority areas.

The organization of the remainder of this paper is as follows: Section 2 introduces the study area, methodology, and data sources, with a focus on the basic situation of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the study area, as well as the relevant methods and data collection procedures involved in the research. Section 3 presents the research results. Section 4 discusses the findings in detail and provides recommendations for future research. Finally, Section 5 offers conclusions drawn from the study ().

2. Research data and methods

2.1. Study areas and data sources

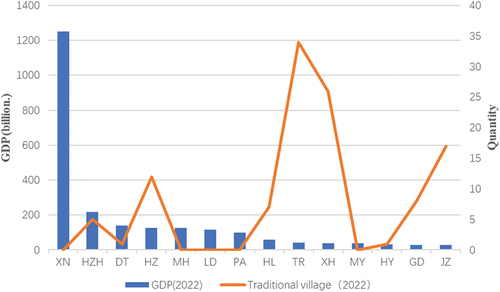

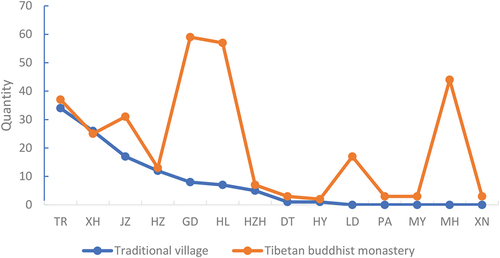

The Hehuang region, a typical minority residential area in China, is known for its well-preserved traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries. China places great importance on preserving these traditional villages while also safeguarding national culture’s authenticity and integrity. Therefore, choosing the Hehuang region as the focus of this research is both typical and representative. This study specifically examines the Hehuang region, which includes 14 counties and districts such as XN(CB, CZ, CX, and CD are combined into XN), XH, TR, JZ, HZ, HZH, GD, HL, DT, LD, PA, HY, MH, and MY (, ).

Table 1. The names of counties and abbreviations are in (illustration created by the author).

The data on traditional villages is sourced from the Chinese Traditional Village Digital Museum website (https://www.dmctv.cn/), which has released 6 batches of national traditional village lists from 2012 to 2022. In the Hehuang region, there are 111 national-level traditional villages inhabited by Tibetan and Tu ethnic groups who practice Tibetan Buddhism. Traditional village data was collected using Google Earth to obtain information such as name, address, longitude, and latitude. TR had the highest number of traditional villages with 34, followed by XH with 26, JZ with 17, HZ with 12, GD with 8, HL with 7, HZH with 5, DT and HY with 1 each, and LD, PA, MY, MH, and XN with 0 traditional villages. The data on the architectural heritage of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries is sourced from the China Religious Affairs Administration’s 2022 publication on religious activity sites (https://www.sara.gov.cn/). Relevant data was filtered and organized, and information on religious buildings, including Tibetan Buddhist monastery names, longitude, latitude, addresses, and other field information, was crawled from Google Maps. Ultimately, a total of 304 Tibetan Buddhist monasteries were collected in the Hehuang region (, ). Economic development data comes from Qinghai Province’s 2022 National Economic and Social Development Statistical Bulletin.

Figure 3. The basic situation of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region (illustration created by the author).

Table 2. The basic situation of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region (illustration created by the author).

2.2. Research methods

2.2.1. Kernel density

Kernel density analysis is a non-parametric spatial analysis method that measures the density of an observation object in its surrounding neighborhood. It can intuitively reflect the spatial aggregation status of geographical elements(X. Guo, Zhang, and Ma Citation2012). The kernel density analysis method can provide insight into the distribution density of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region. This analysis allows for a macro-level understanding of how these elements are distributed across different districts and counties in the region. Kernel density analysis primarily examines the spatial distribution and density of elements, potentially overlooking the spatial relationships between elements. As a result, additional analysis using other tools is used to complement and enhance the findings.

2.2.2. Quantity spatial relationship model

The quantitative spatial relationship model can measure the correlation between two elements. To further explore the correlation in the spatial distribution of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the entire Hehuang region from a macro perspective, this study introduces this analysis method, which can effectively reflect the spatial relationship between the two elements. The formula is as follows:

The formula states that the value range of R is between −1 and 1, R > 0 indicates a positive correlation and R < 0 indicates a negative correlation. In this context, a represents the number of quadrats containing both traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, b represents the number of quadrats with only traditional villages, c represents the number of quadrats with only Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, and d represents the total number of quadrats excluding those with traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries.

2.2.3. Gravity center model

The gravity center model is a crucial analytical tool for studying the spatial development of regional geographic elements. It effectively illustrates the spatial variations and dynamic processes of regional geographic phenomena through distance calculations from the center of gravity of geographic elements (Liang, Xian, and Chen Citation2022). To further investigate the spatial distribution disparities between traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in cities and counties within the Hehuang region, this study introduced this analysis method to elucidate the differences in the spatial distribution of these two elements at a meso level. The calculation is as follows:

(,

) represent the center of gravity coordinates of the regional geographical feature; (

,

) denotes the geographical coordinates of the i-th sub-region;

stands for the attribute value of a specific geographical feature in the i-th sub-region. When the geographical elements are evenly distributed among the sub-regions, the center of gravity is located at the geometric center of the region. However, if the center of gravity of a geographical element significantly deviates from the geometric center of the region, it suggests an unbalanced spatial distribution, known as “center of gravity deviation”.

This study involves two geographical elements, and the spatial relationship between the two elements can be further examined through the overlap of centers of gravity. The calculation is as follows:

“S” represents the distance between the centers of gravity of the two geographical elements, “r” is the deviation index relative to the land area, and “D” is the regional land area. S = 0 indicates the spatial distribution of the two geographical elements is generally consistent; S > 0 indicates a deviation in their spatial distribution. A higher value of S corresponds to a greater degree of deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial characteristics and spatial relationships

3.1.1. Spatial characteristics of traditional village distribution

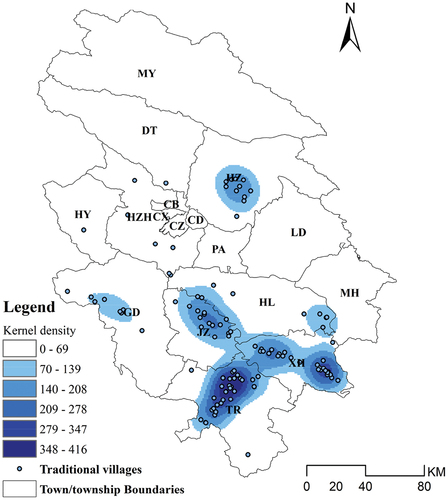

By extracting elevation data from traditional village locations and conducting kernel density analysis on their distribution, it is revealed that traditional villages with Tibetan Buddhism as their belief in the Hehuang region exhibit specific spatial characteristics.

The traditional villages are distributed across altitudes ranging from 1907 to 3394 meters, with a primary concentration observed at altitudes between 2200 and 3200 meters. However, it is noteworthy that a minor proportion of these villages also exist within other altitude ranges.

The distribution of traditional villages in the region shows two main high-density core areas and three sub-density core areas. The high-density core areas are situated south of TR and northeast of XH. While the sub-density core areas are found in the northeast of JZ, the northwest of XH, and the central part of HZ.

The distribution of traditional villages with Tibetan Buddhist beliefs in the entire Hehuang region is closely linked to topography, economic development levels, and the size of ethnic minority populations. These villages are typically located in shallow mountainous regions where Tibetans and Tu people exist, with moderate economic development, a rich historical background, and a strong adherence to Tibetan Buddhism ().

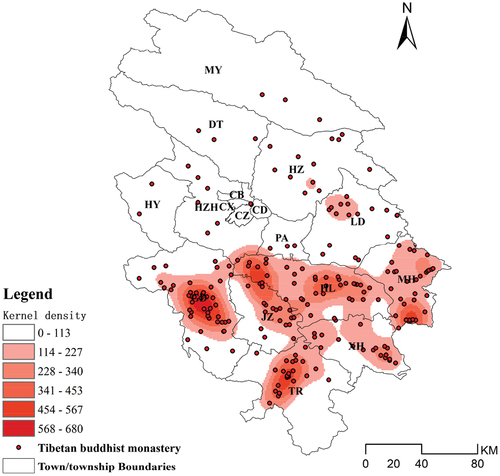

3.1.2. Spatial characteristics of the distribution of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries

The spatial distribution of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region, with a sparse presence in the north and a denser concentration in the south, shows clear regional disparities.

The Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region are situated at altitudes ranging from 1707 to 3778 meters, with a preponderance of monasteries clustered within the altitude range of 1707 to 2800 meters. While a limited number of monasteries are also found above the 2800-meter altitude mark.

There are two main high-density core areas for Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, one in the middle of GD and the other in the south of TR. Additionally, there are several smaller core areas in HL, JZ, MH, XH, and LD in the southern part of the Hehuang region. While there are Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the northern region, their numbers are fewer and more scattered compared to the southern region.

The distribution of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region is closely linked to the number of ethnic minorities practicing Tibetan Buddhism in the region, although there are some deviations. For example, HZ, predominantly inhabited by the Tu ethnic group, which accounts for 17% of the total population, has a small and dispersed number of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries despite the Tu ethnic group’s adherence to Tibetan Buddhism ().

3.2. Spatial relations

The spatial relationship between traditional Tibetan Buddhist villages and monastery buildings in the Hehuang region is demonstrated through similar distribution patterns at a macro level, correlated distribution scales at a meso level, and specific distribution positions at a micro level. This study employs the gravity center model, quantity spatial relationship model, and typical case analysis to examine the spatial relationship between traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region across three levels: macro, meso, and micro.

3.2.1. Quantitative spatial relationship analysis

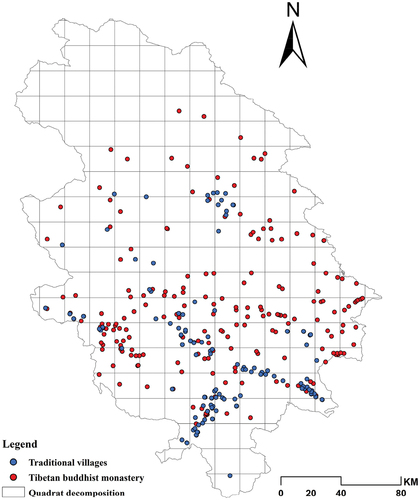

To further explore the relationship between traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region at a macro level, we utilized ArcGIS to pinpoint the locations of 111 traditional villages and 304 Tibetan Buddhist monasteries on the map. By dividing the Hehuang region into quadrat decomposition measuring 15 KM *15 KM, we overlaid the distribution layers of traditional villages and monasteries on the quadrat decomposition to create a comprehensive distribution map of these entities in the Hehuang region ().

Figure 6. Spatial distribution and quadrat decomposition of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries (illustration created by the ArcGis 10.8.1).

The study counted the number of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and traditional villages in each quadrat. The results revealed that 37 quadrats in the Hehuang region contained both traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, while only 4 quadrats had traditional villages alone. Additionally, there were 46 quadrats with only Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and 115 quadrats with both traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries (a = 37, b = 4, c = 46, d = 115, n = 202). The calculation of the quantitative spatial relationship index R yielded a value of 0.504. This indicates a positive correlation between the distribution of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region, with a moderate spatial correlation.

3.2.2. Analysis of center of gravity deviation

By introducing the gravity center model, this study further measures the spatial distribution differences between traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries at the mesoscale across various cities and counties in the Hehuang region. In ArgGis10.8, the centers of gravity of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist temples in the Hehuang area, cities, and counties were calculated. The distance between these centers of gravity was then determined and the data was substituted into formulas (2) and (3) respectively.

As shown in , the center of gravity of traditional villages in the Hehuang region (102.068°E, 35.903°N) is situated to the east of JZ, while the center of gravity of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries (102.088°E, 36.061°N) is positioned to the west of HL. In terms of deviation distance, the distance between these two centers of gravity is 21.72 km, with a deviation index of 0.093. From a local perspective, there exists a noticeable spatial difference between the center of gravity of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in counties within the Hehuang region. The extent of this deviation varies significantly. DT, HL, HZH, GD, and HY exhibit larger deviation distances, while JZ, TR, and XH show smaller deviation distances. From the perspective of the deviation index, DT and HL exhibit the highest levels of deviation. DT, being a Hui Autonomous County, has a relatively small and scattered number of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, contributing to its significant deviation index. HL boasts a large number of evenly distributed Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, but traditional villages are scattered on the east and west sides. Furthermore, the strip shape of HL as a whole also results in a substantial deviation index. The deviation indices for JZ, TR, and XH are relatively small. Both JZ and TR belong to Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. On one hand, the primary ethnic group in these two counties is Tibetan, and the distribution of the Tibetan population and villages is concentrated and balanced. On the other hand, TR is the only national historical and cultural city in Qinghai Province and the birthplace of Tibetan culture. Here, a multi-ethnic settlement area dominated by the Tibetan people has been formed. Since the Ming and Qing dynasties, a politico-religious integration system centered on Longwu Monastery has gradually taken shape, where various ethnic cultures have converged and flourished, resulting in a rich and diverse Tibetan culture. TR is relatively isolated in terms of transportation and economically backward, which has enabled the preservation of ancient and primitive cultures. JZ is one of the birthplaces of Tibetan people in the Yellow River Basin, with a long Tibetan history and profound cultural heritage. In 2020, Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture was declared as a demonstration region for the concentrated and contiguous protection and utilization of traditional villages in China, receiving 150 million yuan in central government subsidies for the protection and development of traditional villages in the region. Although XH is a Salar Autonomous County, four of its townships (out of three towns and six townships) are Tibetan townships located in higher-altitude areas, which have been less affected by urbanization. Consequently, Tibetan culture and cultural heritage have been relatively well preserved. LD and MH have a significant number of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, the majority of these areas are mountainous with challenging natural environments. In recent years, the Chinese government’s immigration and relocation policy has led to the relocation of many villages to more accessible resettlement areas. This has resulted in the abandonment of villages and the disappearance of traditional Tibetan Buddhist villages in the region.

Table 3. The distribution centers of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and their degree of deviation (illustration created by the author).

Overall, the deviation between traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the entire Hehuang region is not significant, demonstrating a high degree of spatial equilibrium on a macro level. On a meso level, there is a certain degree of spatial deviation in the distribution of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries among various cities and counties, with significant variations in the extent of deviation among different locations. It is noteworthy that there are counties with a significant number of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries but lacking the presence of traditional villages.

3.2.3. Position relationship analysis

Historically, the formation of villages in the Hehuang region with Tibetan Buddhism as the main belief was closely tied to the location of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries. To better understand the spatial relationship between traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region at a micro level, typical cases were investigated. The positional relationship between traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries can be roughly categorized into the following 3 types: (1) Villages separated from Tibetan Buddhist monasteries (2) Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in villages: either at a key location within the village or positioned at the village center (3) Tibetan Buddhist monasteries near villages ().

Table 4. The positional relationship between traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries (illustration created by the author).

4. Discussion

As a valuable part of China’s cultural heritage, traditional villages hold significant cultural importance. The Chinese government is actively supporting the protection of traditional villages through policies, funding, and technological assistance. The location of traditional villages is intricately linked to the surrounding natural environment and cultural factors, particularly in ethnic minority regions where there is a strong spatial connection between villages and religious buildings. The research results also reflect this. The preservation of traditional villages should prioritize the preservation of residents’ way of life. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the spatial relationship between traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the area, offering valuable insights for the future selection and conservation of traditional villages in the region.

4.1. Spatial correlation

The spread of Tibetan Buddhism to the Hehuang region resulted in a close interdependence between the monastery and surrounding villages. This relationship, rooted in religious beliefs, has a deep historical and cultural significance. The relationship between monasteries and villages is established over time, primarily influenced by the natural and human environment. Monasteries impact the daily lives of village residents by offering spiritual solace, while residents support the monasteries’ operations through financial contributions. Additionally, residents conduct their daily sacrificial activities within the monasteries. Studies have shown that many Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region are situated in low mountain regions, with some Tibetan Buddhist monasteries transitioning to river valleys and plains to attract more followers and extend their reach. In the application process for Chinese traditional villages, it is emphasized that villages should possess elements such as a long history, notable figures, scenic spots, historical relics, intangible culture, and folk customs. Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, as valuable historical and cultural heritage, play a significant role in the development of villages and impact the cultural life of villagers. The Hehuang region hosts numerous grand traditional festivals, including the Laze Festival, June Festival, and Huaer Festival, which are held in the Tibetan Buddhist monasteries.

4.2. Factors affecting distribution

Due to the disparities in the natural environment and socio-economic conditions in the Hehuang region, the spatial distribution of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries influenced by the Tibetan Buddhism faith also exhibits heterogeneity. GD, MH, and HL are counties dominated by Tibetan and Tu ethnic groups, with Tibetans and Tus being the largest ethnic minorities in these regions, accounting for 37.01%, 20.29%, and 16.8% of the population, respectively (statistical data sourced from the Seventh National Population Census of China).

The region is home to a significant number of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, with a relatively concentrated presence. However, research indicates that there is clear heterogeneity in the spatial distribution of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries. The villages in the Hehuang region that adhere to Tibetan Buddhism have primarily originated from the establishment of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries. While some monasteries have been reconstructed within populated regions, the overall number remains limited. In recent times, the Chinese government has introduced a resettlement policy aimed at enhancing the quality of life for local inhabitants. As a result, numerous villages with substandard living conditions have been relocated to more-level resettlement zones, leading to the abandonment of these original settlements. Since 2000, the Chinese government has implemented the West Development policy, which has greatly promoted socioeconomic development in rural areas, especially in remote multi-ethnic gathering areas (Chen et al. Citation2024). Research indicates that economic factors play a significant role in influencing traditional villages (Sun et al. Citation2017). In the Hehuang region, where economic development is relatively advanced in certain cities and counties, residents, eager to improve their living environment but lacking awareness and technical methods for protecting traditional villages, have led to the demolition of numerous original traditional buildings and the destruction of village landscapes at the initial stage of the national implementation of traditional preservation policies. Consequently, many of these villages have failed to meet the criteria for recognition as Chinese traditional villages and have not been included in the inventory of traditional village preservation. Furthermore, the diverse ethnic composition of the Hehuang region has facilitated cultural integration and the phenomenon of faith transitions ().

4.3. Suggestions

Cultural diversity serves as a crucial factor in embodying the characteristics of traditional Chinese villages. Particularly in ethnic minority settlements, the formation and development of traditional villages are not only closely linked to natural factors such as terrain and climate, but also significantly influenced by ethnic beliefs. Driven by ethnic beliefs, unique spiritual spaces distinct from other villages emerge. This spiritual space, in turn, exerts a reciprocal influence on the morphology of the village and the cultural activities of its residents. In the Hehuang region, traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries are not merely cultural heritages; they serve as the spiritual centers for villagers who adhere to Tibetan Buddhism, encompassing their daily interactions and religious practices. The preservation of traditional villages should prioritize the protection of residents’ lifestyles, beyond mere consideration of the villages themselves. As previously mentioned, the criteria for declaring traditional Chinese villages emphasize factors such as a long historical background, notable figures, scenic spots, historical relics, non-material cultural practices, and folklore within the villages. However, these criteria overlook the significant impact that religious buildings outside the villages have on them, potentially excluding some villages from being included in the inventory of traditional village preservation. Therefore, in the future declaration process for traditional Chinese villages, it is imperative to fully understand the relationship between the distribution of villages and spiritual spaces and to prioritize the selection of valuable villages within the radiation range of these spiritual spaces for inclusion in the inventory of traditional village preservation. By collaboratively protecting spiritual spaces and villages, we can safeguard China’s rich and diverse ethnic cultures and realize the national perspective of “diversity in unity”.

4.4. Limitations

Expanding the research sample to include all villages, rather than just those that believe in Tibetan Buddhism and are included in the traditional village list, would lead to more objective study results. However, it is important to note that this study aims to provide theoretical supplements for the future declaration and protection of Chinese traditional villages. Obtaining ethnic attribute data for residents in ordinary villages is challenging compared to traditional villages on the list. Additionally, each county government is responsible for investigating, identifying, and organizing application materials for traditional Chinese villages. It is acknowledged that due to varying levels of attention and professional capabilities among local governments, a few traditional villages may not be selected.

Furthermore, land cover change poses one of the significant threats to heritage preservation (Guo et al. Citation2023). The application of remote sensing technology can provide crucial assistance in the distribution, dynamic observation, and monitoring of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in this study. In the future, we will consider enhancing the utilization of remote sensing technology to further investigate the evolution of the distribution of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the region as well as the influencing factors.

5. Conclusion

Both traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries fall within the category of cultural heritage. Within a specific region, a thorough understanding of the spatial distribution and characteristics of cultural heritage plays a crucial role in its preservation. Compared to previous studies, this paper employs GIS-related analytical tools in conjunction with field research to conduct a collaborative study on the spatial distribution characteristics and spatial relationships between traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries from macro, meso, and micro perspectives. Furthermore, it analyzes the influencing factors behind these phenomena.

The findings indicate that: (1) The spatial distribution of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region exhibits a positive correlation with a moderate level of spatial correlation. (2) The distribution of traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region demonstrates a high spatial balance. Yet, there are instances where certain counties have an abundance of monasteries but lack traditional villages, particularly in MH, GD, HL, and LD. Various factors such as economic, policy, and cultural integration contribute to this phenomenon. (3) The location relationship between traditional villages and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in the Hehuang region can be categorized into three types: Villages separated from Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, Tibetan Buddhist monasteries in villages, and Tibetan Buddhist monasteries near villages.

The preservation of traditional villages in ethnic minority regions necessitates a focus not only on the protection of material spaces but also on the significance of safeguarding cultural spaces. Studying the spatial distribution to reveal the characteristics, relationships, and influencing factors between these two aspects is conducive to enriching the theory of traditional village preservation. This, in turn, provides scientific justification for the preservation of traditional villages and religious architectural heritage in the Hehuang region as well as other ethnic minority areas.

Furthermore, in the future nomination process of Chinese traditional villages, it is essential to fully recognize the distribution relationship between villages and faith spaces. Priority should be given to screening valuable villages within the radiation range of faith spaces and incorporating them into the list of traditional village protection. Policies should be formulated to ensure the coordinated protection of faith spaces and villages.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Yaolong Zhang, Junhuan Li, Jingjing Wang, and Xin A. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Yaolong Zhang and Jingjing Wang, Junhuan Li reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript, as submitted. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that during the research, data collection, and preparation of this manuscript, no third-party funding or interests that could potentially influence the research outcomes were received. All authors confirm that there are no financial conflicts of interest directly related to this study in the preparation of this manuscript. Furthermore, the authors affirm that all data, images, tables, or other information used in this study were obtained from appropriate sources and have been correctly cited. All referenced literature and resources adhere to the relevant norms of academic integrity and citation practices. The authors express their gratitude to all individuals and institutions involved in this research, as well as to their peers and reviewing experts who have provided valuable input for this manuscript. The authors commit to maintaining the transparency of the research and are open to scrutiny and evaluation by the academic community.

Data availability statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yaolong Zhang

Yaolong Zhang is a Ph.D. candidate in the School of Architecture at Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology (Xi’an, China). He is also an associate professor at the School of Geography and Urban and Rural Planning of Longdong University (Qingyang, China). He has been engaged in interdisciplinary research in the fields of rural planning, traditional village protection, rural settlement environment, and geospatial analysis.

Junhuan Li

Junhuan Li is a professor in the School of Architecture at Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology (Xi’an, China). His research fields include regional architecture and rural settlement environments.

Jingjing Wang

Jingjing Wang is a lecturer in the School of Art at Longdong University (Qingyang, China). Her research fields include culture and art, and traditional villages.

Xin A

Xin A is an engineer at Qinghai Building Materials Science Research Institute Co., Ltd. His research fields include regional architecture and rural settlement environments.

References

- Chen, C., B. Li, and M. Wang. 2023. “Historical Evolution of the Space Form of Traditional Settlements Influenced by Temples in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Since the Qing Dynasty: A Case Study of Bailingmiao Town.” Economic Geography 43 (11): 220–228. https://doi.org/10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2023.11.023.

- Chen, J., Y. Zhou, D. Liu, A. Zhu, and Q. Liu. 2018. “Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Religious Architecture Heritages in China and the Influential Factors.” Journal of Arid Land Resources and Environment 32 (5): 7. https://doi.org/10.13448/j.cnki.jalre.2018.145.

- Chen, Y., B. Shu, M. Amani-Beni, and D. Wei. 2024. “Spatial Distribution Patterns of Rural Settlements in the Multi-Ethnic Gathering Areas, Southwest China: Ethnic Inter-Embeddedness Perspective.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 23 (1): 372–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2023.2218467.

- Eliade, M. 1959. The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.

- Fang, Y., H. Lu, and Z. Huang. 2023. “Spatiotemporal Distribution of Chinese Traditional Villages and Its Influencing Factors.” Economic Geography 43 (9): 187–196. https://doi.org/10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2023.09.020.

- Guo, H., F. Chen, Y. Tang, Y. Ding, M. Chen, W. Zhou, M. Zhu, et al. 2023. “Progress Toward the Sustainable Development of World Cultural Heritage Sites Facing Land-Cover Changes.” The Innovation 4 (5): 100496–100496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2023.100496.

- Guo, X., Q. Zhang, and L. Ma. 2012. “Analysis of the Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Rural Settlements in the Mountainous-Hilly Transition Zone and Its Influencing Factors.” Economic Geography 32 (10): 114–120. https://doi.org/10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2012.10.018.

- He, W., and C. Zhou. 2023. “Historical Press of the Integration of the Hehuang Ethnic Corridor and the Central Plains: Centered on the Ming and Qing Dynasties.” Journal of South-Central University for Nationalities (humanities and Social Sciences) 43 (5): 74–81. https://doi.org/10.19898/j.cnki.42-1704/C.20230513.07.

- Huang, L., K. Xiong, X. Jia, Bao G, and He Y 2024. “The Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in Yunnan Province Based on GIS.” Journal of Yunnan Agricultural University (Social Science) 18 (1): 141–149. https://doi.org/10.12371/j.ynau(s).202307039.

- Huang, X., Y. Feng, D. Li, and Z. Li. 2018. “Analysis of the Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Traditional Villages in Northwest China.” Journal of Northwest Normal University (Natural Science) 54 (6): 117–123. https://CNKI:SUN:XBSF.0.2018-06-020.

- Lai, C., Z. Chen, and W. Sun. 2020. “Research on the Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in Southern Jiangxi.” Journal of Jiangxi Normal University: Natural Science Edition 44 (3): 322–330. https://doi.org/10.16357/j.cnki.issn1000-5862.2020.03.

- Lha, B. 2022. “Promoting Sinicization of Tibetan Buddhism from Multiple Dimensions.” Journal of Minzu University of China (philosophy and Social Sciences Edition) 49 (5): 42–50. https://doi.org/10.15970/j.cnki.1005-8575.2022.05.015.

- Li, B., S. Yin, and P. Liu. 2015. “Spatial Distribution of Traditional Villages and the Influencing Factors in Hunan Province.” Economic Geography 35 (2): 189–194. https://doi.org/10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2015.02.027.

- Li, J., and Y. Zhang. 2023. “A Study of the Settlement Space of Gyalrong Tibetan Villages in Barkam Based on Pattern Language Theory: Exemplified by Chupo, Zonggag, and Dekyi Villages.” Heritage Architecture (4): 18–24. https://doi.org/10.19673/j.cnki.ha.2023.04.003.

- Liang, L., L. Xian, and M. Chen. 2022. “The Evolution of Regional Population and Economic Centers in China Since the Reform and Opening Up and Its Influencing Factors.” Economic Geography 42 (2): 93–103. https://doi.org/10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2022.02.011.

- Ortner, S. B. 1989. High Religion: A Cultural and Political History of Sherpa Buddhism. Vol. 9. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Peng, W., Y. Yang, Y. Huang, Zou K, Duan K, and Shen Y 2023. “Spatial Differentiation Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Buddhist Monasteries in Yunnan Province.” Tropical Geography 44 (2): 315–325. https://doi.org/10.13284/j.cnki.rddl.003754.

- Pu, W. 2000. “Historical Changes of Tibetan Buddhism in Hehuang Area.” Qinghai Social Sciences 6:95–100. https://doi.org/10.14154/j.cnki.qss.2000.06.023.

- Shi, J., and Y. Jin. 2021. “Research on the Symbiotic Model Language of Tibetan Villages and Temples in Hehuang Area Based on Space and Events.” Architectural Journal S (01): 40–46.

- Su, F. 2013. “Paul K. Nietupski and His Labrang Monastery: A Tibetan Buddhist Community on the Inner Asian Borderlands, 1709-1958.” Journal of Tibet Nationalities Institute (Philosophy and Social Sciences) 34 (6): 77–78+140. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=FruxrO_GJXIBiNheed6VPuXkk2T9IDxTMom82Nz6jeyf_Vc-RZSzgBTwMKCweCYo0U340FI8kdzXQkwLxaW-JldGyNzx23qjOENT2liBx8_Dmpkya2QLEmKB16HQd2JnjwcA2WWoJ7w=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

- Sun, J., J. Niu, and K. Zhang. 2017. “Spatial Distribution Pattern and Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in Shanxi.” Human Geography 32 (3): 102–107. https://doi.org/10.13959/j.issn.1003-2398.2017.03.013.

- Tang, C., Z. Wan, M. Liu, Wan Z, and Liang W 2021. “Perception and Improvement of the Protection and Inheritance of Traditional Village Cultural Heritage Based on Multi-Agent.” Journal of Arid Land Resources and Environment (In Chinese) 35 (2): 196–202. https://doi.org/10.13448/j.cnki.jalre.2021.060.

- Tian, H. 2020. “Spatial Distributive Characteristics and Its Influencing Factors of Traditional Villages in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region.” Economic Geography 40 (7): 143–149. https://doi.org/10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2020.07.016.

- Wang, P., J. Zhang, F. Sun, Cao, S.S., Kan, Y., Wang, C. and Xu, D 2021. “Spatial Distribution and the Impact Mechanism of Traditional Villages in Southwest China.” Economic Geography 41 (9): 204–213. https://doi.org/10.15957/j.cnki.jjdl.2021.09.021.

- Wang, W. 2023. “Comparative Review of Ideal Layouts in Han Buddhist and Catholic Monasteries.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 22 (6): 3186–3223. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2023.2182638.

- Wang, Z., M. Chi, and X. Gao. 2023. “Research on the Visual Experience of the Archetypal Space for Circumambulation Paths at Tibetan Buddhist Temple Halls in Inner Mongolia Based on Isovist Vision Quantitative Analysis.” World Architecture (12): 106–113. https://doi.org/10.16414/j.wa.2023.12.008.

- Xiang, H., Y. Qin, M. Xie, and B. Zhou. 2022. “Study on the “Space Gene” Diversity of Traditional Dong Villages in the Southwest Hunan Province of China.” Sustainability 14 (21): 14306–14306. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114306.

- Xiao, J., and L. Huang. 2020. “Quantitative Analysis of the Form and Evolution of Tibetan Buddhism Temples: Taking Sera Monastery As an Example.” Huazhong Architecture 38 (2): 114–118. https://doi.org/10.13942/j.cnki.hzjz.2020.02.024.

- Xu, K., and F. Zhou. 2023. “Quantitative Indexing and Formation of Flat Morphology of Traditional Rural Settlements in Southeast Chongqing.” Chinese & Overseas Architecture (3): 75–80. https://doi.org/10.19940/j.cnki.1008-0422.2023.03.012.

- Xue, M., C. Wang, W. Dou, and Wang, Z. 2020. “Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Traditional Villages in the Yellow River Basin and Influencing Factors.” Journal of Arid Land Resources and Environment 34 (4): 94–99. https://doi.org/10.13448/j.cnki.jalre.2020.101.

- Yue, N., and J. Li. 2023. “Path for Protection of Ferry Cultural Heritages Along the Yellow River in Shanxi.” Journal of Arid Land Resources and Environment (In Chinese) 37 (7): 102–110. https://doi.org/10.13448/j.cnki.jalre.2023.166.

- Zhu, L., H. Su, P. Zhang, and Z. Li. 2019. “Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Tibetan Buddhist Temples in Qinghai Province.” World Regional Studies 28 (2): 209–216+159. https://CNKI:SUN:SJDJ.0.2019-02-023.

- Zou, M., and A. Bahauddin. 2024. “The Creation of “Sacred Place” Through the “Sense of Place” of the Daci’en Wooden Buddhist Temple, Xi’an, China.” Buildings 14 (2): 481–481. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14020481.