ABSTRACT

Person-Environment Fit (P-E Fit) theory is an important concept for studying the complex relationships between people and the environment and for explaining individual behaviors. Recent research regarding the built environment typically focuses on P-E Fit to achieve a harmonious relationship between people and their surroundings. However, comprehensive knowledge of this research topic is insufficient for practical applications and future developments. This paper adopts a scoping review method to summarize the bibliometric features and the core components (i.e. person, environment, fit, and outcomes) regarding P-E Fit theory in the context of built environments, and discusses several existing knowledge gaps: the narrow scope of the topics, the unclear mechanism, and the lack of proactive and dynamic views. Finally, a new P-E Fit model is developed, and its strengths for sustainable improvement of the built environment are discussed. This review deepens the understanding of the literature, refines the theoretical framework, and provides researchers, designers, and policymakers with tools for developing research programs and practices for providing people-centered built environments from a P-E Fit perspective.

1. Introduction

1.1. The crucial relationship between people and the built environment

The built environment comprises the places and spaces that have been created to meet people’s needs for daily life, work, and entertainment, and it includes buildings, open spaces, and transportation (Kaklauskas and Gudauskas Citation2016; Roof and Oleru Citation2008). The built environment holistically affects people on physical, psychological, and social levels (Jones and Brischke Citation2017). Particularly in environmental psychology and sociology, scholars have emphasized the effects of the different types of built environments on physical health (Gao, Ahern, and Koshland Citation2016; Gunn et al. Citation2017), mental health (Guite, Clark, and Ackrill Citation2006; Lam, Loo, and Mahendran Citation2020), physical activity (Boone-Heinonen et al. Citation2010; Farahani, Izadpanahi, and Tucker Citation2022; Saelens, Sallis, and Frank Citation2003), social interaction (Bottini Citation2018; Francis et al. Citation2012; Gehl Citation1987; Jacobs Citation1961), sense of community (Bonaiuto, Fornara, and Bonnes Citation2003; De Vries et al. Citation2013; F. Zhang, Loo, and Wang Citation2021), life satisfaction and well-being (Bonaiuto et al. Citation2015; Z. Zhang and Zhang Citation2017). Therefore, improving the built environment represents a key method for achieving a high quality of life, and as a result, this is a primary goal of urban development and architectural advancements (H. Li et al. Citation2018; Moser Citation2009). Although the importance of the relationship between the person and the built environment is widely recognized, there are limited theoretical models or practical tools for describing person-environment interactions in the built environment.

1.2. The P-E Fit concept

The P-E Fit is key when considering the built environment’s impact on people (Friesen et al. Citation2016). Scholars are also aware of the need to investigate the p-E Fit rather than individual personal or environmental factors (Iwarsson Citation2005). The concept of P-E Fit is believed to have vocational and organizational origins, and it is often defined as the congruence, matching, or similarity between the person and the environment. The core principle of P-E Fit theory is that in addition to the individual characteristics of the person and the environment, the fit between them will have an even more significant impact on a person’s motivations, behaviors, and health (Caplan Citation1983; J. R. Edwards Citation2008; J. Edwards, Caplan, and Harrison Citation1998; Parsons Citation1909). Since Parsons (Citation1909) first proposed a model for making career choices based on the match between personal attributes and environmental characteristics, numerous studies focusing on P-E Fit have been conducted in the field of organizational psychology. Several well-established theoretical models have been developed, for instance, person-vocation fit, person-job fit, and person-organization fit (Cable and Judge Citation1997; Guan et al. Citation2021; Hoffman and Woehr Citation2006; Muchinsky and Monahan Citation1987).

1.3. The P-F fit theory in the built environment

Since the development of the P-E Fit theory, scholars have recognized its value for studying the relationships between people and their built environments. Particularly in the context of a human-centered society, scholars have begun to rethink their approach to avoid an excessive focus on the physical environment itself while neglecting its fit with people. The P-E Fit theory places the fit at the center of the built environment design.

In the second half of the 20th century, the theory was extended to the study of community and housing environments, with studies focusing primarily on gerontology (Kahana et al. Citation2003; Lawton and Nahemow Citation1973). One of the most influential concepts is Lawton’s ecological model of aging (Lawton and Nahemow Citation1973), which is based on famous psychologist Lewin’s field theory defined by the equation, [B = f (P, E)], where behavior (B) is defined as a function (f) of personal characteristics (P) and environmental characteristics (E) (Lewin Citation1943). Lawton applied the P-E Fit concept to the aging process and proposed the modified ecological model, [B = f (P, E, P*E)], which is based on the environmental docility hypothesis. Here, the P*E term represented the personal ability (P) in response to the environmental stress (E). For example, negative effects will be observed if the elderly were unable to cope with the environmental stress after their physical functions decline.

However, Carp and Carp (Citation1984) and Kahana (Citation1982) criticized Lawton’s model for focusing too much on negative environmental stressors and the passivity of people; in response, they further developed the congruence model to emphasize the positive outcome of environmental support in terms of meeting personal needs. Carp modified Lewin’s equation to [B = f (P, E, PcE)], where PcE denotes the congruence of personal needs with environmental support (Cvitkovich and Wister Citation2001). Subsequently, Lawton (Citation1987) also accepted this adaptation and revised the previous model to include personal resources (instead of personal ability) and environmental resources (instead of environmental stress), which rendered Lawton’s P*E term equivalent to Carp’s PcE term (Cvitkovich and Wister Citation2001). This process indicates a shift in perspective from people passively coping with environmental stress to actively gaining environmental support, laying the foundation for extending the P-E Fit theory in the context of built environments.

Additional related concepts have been developed according to these models (Fornara et al. Citation2019), including the P-E compatibility model (Kaplan Citation1983), the priority model (Cvitkovich and Wister Citation2001), and the environmental accessibility model (Iwarsson and Ståhl Citation2003). Recent efforts have also aimed to expand the application scope from elderly communities to a wider range of built environments (Bankins, Tomprou, and Kim Citation2020; Jusan Citation2010; Lashani and Zacher Citation2021; Mao, Wang, and Wang Citation2022; Tsaur, Liang, and Lin Citation2012). It is generally accepted that the most important feature leading to a high quality of life may be the harmony between people and the environment (Moser Citation2009); as a result, there has been growing interest in applying the P-E Fit theory in the context of built environments.

However, to our knowledge, a comprehensive review of the rapidly growing body of literature has not been conducted. Without such a systematic critical review, it is difficult to understand the latest research priorities and knowledge gaps, which limits further developments of the theory, thereby hindering the theory’s contribution to the improvement of the built environment.

1.4. Research objective

Therefore, the present study aims to explore the new developments of the P-E Fit theory in the context of built environments, and through a comprehensive review of the relevant literature to address the following research questions:

What are the recent developments in the P-E Fit theory in the context of built environments?

What are the main topics of discussion in the literature?

What are the specific attributes and relationships of the core components (person, environment, fit, and outcomes)?

Where are the knowledge gaps?

What is the future research agenda, and how can it support the sustainable improvement of the built environment?

Ultimately, this study aims to improve the understanding of the existing literature, refine the theoretical framework of P-E Fit in the context of the built environment, and provide researchers, designers, and policymakers with ideas for developing human-centered built environments according to the P-E Fit theory.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 explains the methods of literature collection and analysis; Section 3 evaluates the status and gaps of P-E Fit research in the built environment field, proposes a new model, and discusses the future research agenda; Section 4 summarizes the conclusions.

2. Methods

This study adopted a scoping review method, which is often used to examine the progress and scope of a research topic and identify gaps in the existing literature. It represents a rigorous and transparent approach that enables repeatability (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005; Hanc, McAndrew, and Ucci Citation2018; Pham et al. Citation2014). This review followed the process described by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005): (1) identify the research question; (2) search for relevant studies; (3) select studies; (4) chart the data; and (5) collate, summarize, and report the results. Herein, a literature review is presented to analyze P-E Fit research in the context of the built environment. After identifying the research question (see Section 1.4), the review was conducted in three phases: (a) screening criteria were applied to collect and screen the literature from the database; (b) the results therein were analyzed to identify the theoretical development status and knowledge gaps; and (c) a new P-E Fit model that can be used to promote sustainable improvements to the built environment was proposed, and a potential future research agenda was outlined ().

2.1. Database search and screening process

In October 2022, the Scopus database was used to search relevant publications, because articles included in the Scopus database are considered to have passed a rigorous peer review process, and are widely used by researchers (Benita Citation2021; Hanc, McAndrew, and Ucci Citation2018). Detailed search strategy and inclusion criteria are shown below (:

Comprehensive searching. Search terms were separated by Boolean operators (AND/OR) () and used to search for titles, abstracts, and keywords to identify potential literature related to the P-E Fit theory in the context of built environments, which yielded 1610 articles.

Initial screening. Screening was conducted by reading the titles, abstracts, and keywords. The inclusion criteria for this stage are: include English-language journal articles related to the built environment and exclude literature from completely different fields (e.g., organization, medicine, computer science). The scope was narrowed, and 92 articles were obtained.

Comprehensive screening. The full texts of the remaining articles were read for final eligibility. The inclusion criteria for this stage are: (1) Closely related to the built environment, excluding literature that involved the topic of the built environment, but the core discussion was social environment; (2) Closely related to P-E Fit, excluding literature that only unilaterally investigates personal attributes or environmental attributes, or only focuses on the unilateral impact of the environment on people, rather than the fit between person and environment and its impact. Ultimately, 48 articles were obtained after this rigorous screening, representing the P-E Fit research in the context of built environments for subsequent analysis.

Table 1. Search terms used for the database.

2.2. Data analysis

The bibliometric method was used to evaluate the literature features to provide an overview of the distribution regarding countries/regions, time, journals, and keywords (.

The VOSviewer application was used to analyze the keywords. VOSviewer is a scientific mapping tool that enables comprehensive analysis and visualization of literature features such as keyword frequency and publication date. It is often used to illustrate the structure, evolution, and cooperation of the literature network (Büyüközkan, Ilıcak, and Feyzioğlu Citation2022; Hacıoğlu and Polatoğlu Citation2023; Yang et al. Citation2023). In this study, 48 identified articles were imported into VOSviewer, and the keyword frequency analysis function was used to generate a visual map of hot keywords, with the minimum number of keyword occurrences set to five.

Then, the attributes and relationships among the core components were critically analyzed with reference to the advanced P-E Fit theoretical criteria. Based on this evaluation, knowledge gaps were identified.

2.3. New model proposal

To further refine the theoretical framework and to contribute to the built environment improvements, a new P-E Fit model was developed. Herein, we discuss its contributions to the sustainable improvement of the built environment and identify a future research agenda (.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Bibliometric features

3.1.1. Country/region analysis

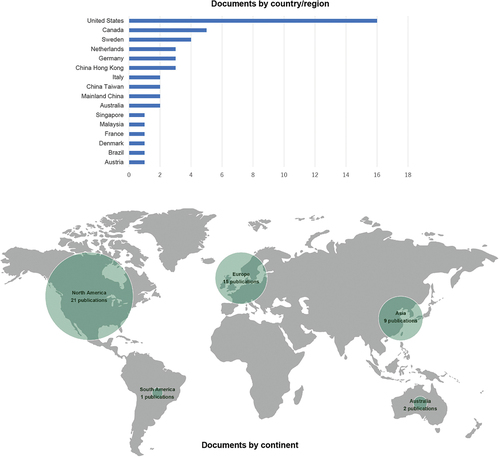

The corresponding authors of the screened articles were from 16 countries/regions. Sixteen (33.3%) of the articles were from the United States, with the second and third most articles coming from Canada (10.4%, 5 articles) and Sweden (8.3%, 4 articles), respectively. Articles from North America (n = 21), Europe (n = 15), and Asia (n = 9) accounted for 43.8%, 31.3%, and 18.8% of all articles, respectively. Thus, in general, developed countries/regions have contributed the majority of the literature on this topic, and studies from developing countries are relatively limited ().

3.1.2. Time development analysis

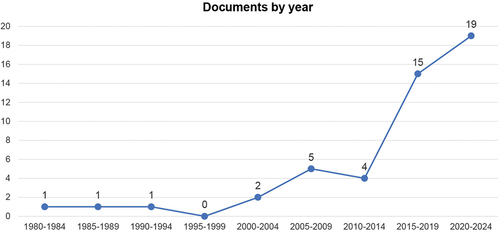

shows that P-E Fit as it relates to the built environment is an emerging topic that has grown rapidly in recent years. Although the P-E Fit theory appeared in journal articles in the built environment field as early as the late twentieth century, it has been slow to develop. The frequency of publications on this topic has trended upward into the 21st century, with a dramatic increase in scholarly discussions, especially in the last decade; notably, 19 relevant articles have been published since 2020. This observation implies that the potential applicability of the P-E Fit theory for built environment research has been recognized.

3.1.3. Published journal analysis

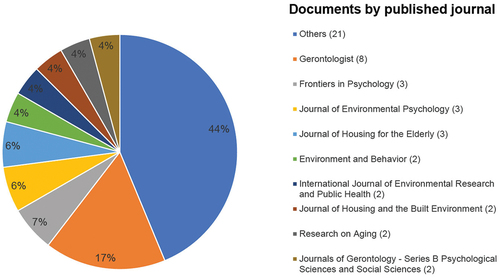

The 48 selected articles were published across 30 academic journals, nine of which published at least two articles (). These results reveal that gerontology journals (e.g., Gerontologist [17%]) dominate, followed by psychology-related journals. Thus, it is clear that research continues to focus primarily on the built environments related to older adults.

3.1.4. Keyword analysis

The VOSviewer application was used to analyze the hot topics discussed in P-E Fit research in the built environment. The results are shown in , where larger boxes indicate more frequent occurrences, and different colors indicate the average time to publication. In addition to the search terms “person”, “environment”, and “fit”, there is also a discussion of the “outcomes” of the fit. Specific clusters of keywords can be found in the literature regarding these four core compositions:

Person: including “human (s)”, “aged (80 and over, aging, elderly population, very elderly)”, “adult”, “middle aged”, “male”, “female”, “demography”, and “human experiment”. The frequent keywords in this category are consistent with the fact that the elderly population is the main target group of such studies.

Environment: including “environment”, “social environment”, “housing”, “residence characteristics”, and “neighborhood”. The living environment is a popular topic discussed in the environmental dimension. Moreover, the time dimension indicates that discussions of the built environment tend to expand from individual housing to neighborhood.

Fit: including “person-environment fit” and “satisfaction”. Not surprisingly, “person-environment fit” is the core topic, and “satisfaction” is often used to measure fit.

Outcomes: including “wellbeing”, “aging in place”, “independent living”, and “daily life activity (activities of daily life)”. A person’s fit with the built environment will have positive or negative effect on their well-being, ageing in place, and daily life. Thus, these outcomes are important aspects impacting the quality of life. Recently, publications have increasingly focused on “wellbeing” and “aging in place”.

3.2. Core components analysis

The results of the keyword analysis represent the core components of the P-E Fit theory in the built environment, which fits well with Edwards’ review criteria for the P-E Fit theory in organizational research (J. R. Edwards Citation2008). That is, a strong P-E Fit theory should clearly define the dimensional attributes of person, environment, fit, and outcomes. Therefore, using it as a criterion, these core components are discussed next.

3.2.1. The person dimension

Edwards (Citation2008) stated that a robust P-E Fit theory must clarify whether person and environment were conceptualized as objective or subjective, because these distinctions were relevant to the meaning and effects of the P-E Fit (John, Caplan, and Harrison Citation1982; Kristof Citation1996).

Personal dimension in the literature can be divided into the objective dimension (PO) includes gender, age, race, education level, occupation, economic status, physical ability, health status, family situation, and other objective demographic information that is not influenced by subjective consciousness (Chen Citation2021; Choi Citation2020; Junot Citation2021; Rosso et al. Citation2021), and the subjective dimension (PS), which can be defined as a subjective perception of something. This includes (PS1), which comprises the user’s subjective perceptions of personal attributes (e.g., I feel I move freely, I feel I am healthy, I do not feel I tend get depressed) (Friesen et al. Citation2016; Kim et al. Citation2020; Lien, Steggell, and Iwarsson Citation2015; Yan, Gao, and Lyon Citation2014), and (PS2), which comprises the user’s subjective preferences and needs for various built environment attributes (e.g., I prefer office space with privacy, I prefer a public transportation environment, I think the location of the facility is important) (Hoendervanger et al. Citation2019; Lashani and Zacher Citation2021; Mao, Wang, and Wang Citation2022).

Personal dimensions influence a person’s fit with the built environment. For example, Thissen and Droogleever Fortuijn (Citation2021) found that low-income older adults in poor villages exhibited lower person-environment fit; Stafford and Gulwadi (Citation2019) suggested that personal resilience could help achieve better fit; Mao et al. (Citation2022) demonstrated that when individuals had more positive attitudes toward travel, this promoted the fit with the travel environment and increased the travel satisfaction; and Cotterell’s (Citation1991) demonstrated that adolescents judged whether the entertainment environment was a good fit based on their own entertainment needs.

The present review revealed that the literature did not clearly define the objective and subjective personal dimensions. As a result, scholars have tended to ignore the differences between the two when selecting personal indicators. This problem led studies to equate the different personal indicators when exploring the impact on fit, thereby ignoring the fact that different personal indicators may affect one another (J. Edwards, Caplan, and Harrison Citation1998). This made it difficult to clarify the overall mechanism of fit. Therefore, it is necessary to distinguish these aspects in future research.

3.2.2. The environment dimension

Like the person dimension, the dimension of the built environment can be divided into objective environmental dimension (EO), which includes type, scale, location, aesthetics, safety, accessibility, cleanliness, quietness, and other attributes of facilities that are not influenced by subjective consciousness and exist objectively (Chen Citation2021; Huang Citation2022; Lawton Citation1983; Rosso et al. Citation2021; Z. Zhang et al. Citation2023), and the subjective environmental dimension (ES), which refers to one’s perception of the built environment of a specific facility, e.g., perceived accessibility (I think this facility is easy to reach), safety (I think this facility is safe), aesthetics (I think this facility is beautiful), and scale (I think this facility is spacious) (Junot Citation2021; Mao, Wang, and Wang Citation2022; Stokes and Meeks Citation2019).

It is worth noting that the ES is a different concept from the PS2. Specifically, the former is a perception and evaluation of a specific built environment (e.g., I think this facility is beautiful, I think this facility is easy to access), and in contrast, the latter refers to one’s perception of his or her preferences regarding the environment that are not object-specific (e.g., I prefer a beautiful facility, I think the accessibility of the facility is important). Unfortunately, this distinction has not been widely recognized. In general, PS2 is a person dimension, although existing literature often mischaracterizes it as environmental perceptions. Ambiguous recognition of these differences will muddle the mechanistic understanding of the fit process. Therefore, the distinction must be clarified in future research.

Environmental dimensions influence people’s fit with the built environment. For example, Park et al. (Citation2015, Citation2017) demonstrated that the supportive environment of senior housing played a significant role in the adaptation of low-income people to an aging environment; Hoendervanger et al. (Citation2019) found that the open versus closed office spaces affect employees’ perceived fit; and Nygren et al. (Citation2007) noted the importance of combining objective and subjective dimensions of housing to consider P-E Fit.

The present review revealed that similar to the person dimension, the literature does not clearly define the difference between objective and subjective environmental dimensions. Furthermore, most studies consider subjective environmental dimensions and investigate users’ subjective perceptions of the built environment through questionnaires and interviews, rather than objective measurements. However, objective built environment measurements are crucial because understanding how objective built environment data can fit with people and bring positive outcomes can provide clear suggestions that are directly applicable to the specific project.

3.2.3. The fit dimension

As mentioned earlier, P-E Fit refers to the congruence, match, or similarity between a person and his or her environment. In the traditional P-E Fit theory, there are two main types of fit: supplementary fit and complementary fit. Supplementary fit refers to similar characteristics between the person and the environment (e.g., I am lively, and the environment is very lively). Complementary fit means that a “weakness or the need of the environment is offset by the strength of the individual, and vice versa” (J. R. Edwards Citation2008; Muchinsky and Monahan Citation1987). Therefore, complementary fit can be further distinguished as either needs (P) – supplies (E) fit (the environmental supplies meet human needs) and demands (E) – abilities (P) fit (human abilities meet environmental demands) (John, Caplan, and Harrison Citation1982; Kristof Citation1996).

In the context of built environments, Lawton’s ecological model of ageing (Lawton and Nahemow Citation1973) favors the demands (E) – abilities (P) fit because it focuses on how people’s abilities respond in the presence of environmental stresses. In contrast, Carp’s and Carp (Citation1984) and Kahana’s (Citation1982) congruence model supports the needs (P) – supplies (E) fit, by emphasizing environmental satisfaction of individual needs. Overall, most of the literature focuses on the demands (E) – abilities (P) fit, which builds upon Lawton’s line of gerontological research and greater focus on the negative abilities of older adults. Examples include the fit between older adults’ physical mobility and the availability of older public housing environments (Saint-Onge et al. Citation2021); the fit between older adults’ affordability and housing environment (Park et al. Citation2015); and the fit between older adults’ family support and community environments (Park and Lee Citation2016). However, in recent years, there have been several studies focusing on needs (P) – supplies (E) fit, which are more diverse and include the fit between an individual’s travel needs and accessibility to public transportation (Mao, Wang, and Wang Citation2022), the fit between the employees’ needs for the facilities and the availability of office environments in shared office spaces (Lashani and Zacher Citation2021), the fit between the employees’ privacy needs and the openness of office spaces (Hoendervanger et al. Citation2019), and the fit between the preferences of the older adults and the support of the nursing home environment (Van Haitsma et al. Citation2019). These distinctions are consistent with Carp’s and Carp (Citation1984) and Kahana’s (Citation1982) earlier disagreement with Lawton’s perspective; specifically, one focuses on human passivity and negative stressors from the environment, and the other focuses on humans’ preferred needs and positive satisfaction from the environment.

Traditional P-E Fit theory commonly uses direct or indirect methods to measure fit. Direct measurements evaluate the perceived match or mismatch between the person and the environment based on the individual. This can be evaluated by directly asking the respondent to rate the fit between him/herself and the environment, also known as the subjective perception of the fit. Indirect measurements collect personal and environmental data separately and calculate the fit scores using a formula (e.g., polynomial regression) (Cable and DeRue Citation2002; J. R. Edwards et al. Citation2006; Guan et al. Citation2021).

Most studies use direct measurement techniques, e.g., based on reported subjective fit scores (Lashani and Zacher Citation2021), environmental satisfaction (F. Zhang, Loo, and Wang Citation2021), degree of satisfaction with needs and values in the built environment (Jusan Citation2010; Weil and Meeks Citation2019), and willingness to visit (Phillips et al. Citation2009) to assess the fits. Only a few papers used indirect methods, such as polynomial regression (Lashani and Zacher Citation2021; Mao, Wang, and Wang Citation2022), or the Housing Enabler tool (Fänge and Iwarsson Citation2005; Iwarsson et al. Citation2009; Nygren et al. Citation2007) to calculate the fit based on separately collected person and environmental indicators.

These findings are inconsistent with traditional P-E Fit research trends, and recent studies have shown that indirect measures, such as polynomial regression, are becoming increasingly popular in organizational studies (Guan et al. Citation2021). Thus, research regarding P-E Fit theory in built environments is lagging. However, to our knowledge, no studies have evaluated which method is more effective or accurate for P-E Fit measurements involving the built environment. Therefore, future research should explore and test this aspect to establish a suitable fit measurement method.

3.2.4. The outcomes dimension

The fit between a person and the built environment can result in positive or negative outcomes. Outcomes discussed in the literature can be divided into psychological and behavioral aspects. Psychological outcomes include life satisfaction (Chen Citation2021; F. Zhang, Loo, and Wang Citation2021), travel satisfaction (Mao, Wang, and Wang Citation2022), job satisfaction (Lashani and Zacher Citation2021), sense of security (Elias and Cook Citation2016), happiness (Van Haitsma et al. Citation2019), community awareness (F. Zhang, Loo, and Wang Citation2021), and apathy (Jao et al. Citation2020). Behavioral outcomes include facility visits (Cotterell Citation1991), physical activity (Rosso et al. Citation2021; Saint-Onge et al. Citation2021), social engagement (Sun, Phillips, and Wong Citation2018), relocation (Granbom et al. Citation2018), and home modifications (Wister Citation1989), all of these are closely related to quality of life.

Edwards (Citation2008) pointed out that it is important to clearly describe the relationship between the outcomes and the fit, and a strong theory should enable deeper descriptions than a simple positive or negative relationship. For example, is the function (relationship) of outcome and fit symmetrical in terms of fit points? Does the most fit point correspond to the best outcome? Are there differences in the impacts of outcomes from the different forms of fit? Unfortunately, such specific descriptions of relationships are rare in the built environment literature. However, Mao et al. (Citation2022) suggested that a misfit is not necessarily a bad situation, and outcomes showed a non-linear relationship with fit when there is a misfit. Oswald et al. (Citation2005) considered the effects of different types of fit with place attachment, and the results emphasized the importance of social needs relative to other needs.

In traditional P-E Fit theory, an element’s importance is often considered as a moderator of the relationship between fit and outcomes, and mismatches involving more important elements can have a greater impact (J. Edwards, Caplan, and Harrison Citation1998; Kahana Citation1982). Unfortunately, only a few of the reviewed publications considered the differential outcomes of the fit with different levels of importance. For example, Choi (Citation2020) considered differential impact outcomes when the different importance functions were satisfied. Interestingly, Cvitkovich and Wister’s (Citation2001) results were inconsistent with those of Phillips et al. (Citation2009), i.e., the former demonstrated that a prioritization model that considers the difference in importance better explains the observed outcomes, whereas the latter found that a prioritization model did not provide a better explanation of outcomes. These contradictions also require a more in-depth response in the future. Once it is established that the fit of important elements will have a greater impact, improvements can be made to the built environment by using limited budgets and resources to prioritize enhancements of environmental elements that are more important to the users. This approach can be employed to maximize the improvement effect with limited resources (Z. Zhang et al. Citation2023).

3.3. Knowledge gaps

Based on the summary of bibliometric features and the critical analysis of core components, the knowledge gaps in P-E Fit theory in the context of built environments were identified: the narrow scope of the topics, the unclear mechanism, and the lack of proactive and dynamic views. These summarized knowledge gaps will motivate subsequent proposals of the new P-E Fit model and future research agendas.

3.3.1. The narrow scope of the topic

The first knowledge gap is related to the scope of topics studied. It is evident from the published journal articles and keyword analysis that institutions, housing, and communities for older adults are the most commonly discussed topics. This is because gerontologists, such as Lawton and Nahemow (Citation1973), Carp and Carp (Citation1984), and Kahana (Citation1982) first introduced P-E Fit theory to study built environments for older adults, and later studies developed on this basis. Unfortunately, up to the present, the theory has not been fully applied to a broader range of research topics. Although this review identified several new and developing topics, such as tourism environments (Huang Citation2022), entertainment facilities (Tsaur, Liang, and Lin Citation2012), transportation facilities (Mao, Wang, and Wang Citation2022), and office spaces (Bankins, Tomprou, and Kim Citation2020), the breadth of knowledge in these areas is still limited and does not form a complete system. To provide theoretical and practical support for a broader range of built environments, future research should be extended, e.g., different people and different types of built environments.

3.3.2. The unclear mechanism

The second knowledge gap in the literature is related to the mechanism of the fit. People, environment, fit, and outcomes are the core components of the P-E Fit theory, and the current literature focuses more on case studies of localized components, while lacking a complete mechanistic description that clearly illustrates the relationships among all of these components. As stated above in Section 3.2, issues such as differences in subjective and objective dimensions of the person and the environment, methods of fit measurements, and the precise relationship between fit and outcomes are all relevant for understanding the entire fit mechanism (John, Caplan, and Harrison Citation1982; Kristof Citation1996). When these concepts are not clarified, it becomes difficult to further discuss the impact mechanism of the objective and subjective dimensions of the person and the environment on the fit, and the fit on the outcome. A clear understanding of the mechanisms is key to guide further research.

When the complete detailed mechanism is known, it can help to elucidate the overall composition and logic of the theory. Thus, future research about the entire system or partial elements can clarify its context within the overall theoretical framework, which can help scholars establish a global vision to guide future research and contribute to the theoretical development.

3.3.3. The lack of proactive view

Another knowledge gap is related to the lack of a proactive view. Based on LLawton and Nahemow’s (Citation1973) seminal ecological model of aging, studies that followed tend to focus on the negative aspects of people. Although Lawton later revised the model in response, the original model has remained the accepted paradigm of gerontological research, and current literature continues to perpetuate the original model (Cvitkovich and Wister Citation2001). Thus, this review found that numerous studies have focused on the environmental challenges faced by the elderly and disabled owing to the decline of their physical functions and cognitive abilities, and these studies also often addressed the lower-order quality of life of disadvantaged groups, i.e., basic life ability.

However, a higher quality of life has higher-order needs (in addition to the basic needs), such as cultural, recreational, social, and self-improvement needs. The theory can contribute to enhancing diverse qualities of life by continuously expanding its scope to the active needs of people. Therefore, future research should consider how the environment actively addresses the needs of different groups. Specifically, proactive methods can be proposed to improve the built environment and to provide ideas for designing a built environment that meets the diversified needs of its users. This can further be applied to the practices affecting the built environment improvements, ensuring that the environment adapts to the person rather than the person adapting to the environment (Kumar et al. Citation2023), thus enabling P-E Fit theory to serve as a tool to promote a higher quality of life.

3.3.4. The lack of dynamic view

The final knowledge gap identified in the literature is the lack of a dynamic view. Finding a way to maintain the fit between people and their built environment in a dynamic and changing society is crucial for achieving the goal of a sustainable built environment. Because both people and environments are constantly changing; for example, people grow and age, and their preferences change, while built environments can become old or damaged. Therefore, it is important to recognize that the relationship between people and their environments is dynamic, and P-E Fit is a process where a perfect fit is the goal, and a misfit is the norm (Lawton and Nahemow Citation1973; F. Zhang, Loo, and Wang Citation2021). Although Lawton (Citation1985) had already emphasized the important concept of person-environment change in gerontological research, only a small body of literature in later studies has focused on the dynamic perspective (Mejía et al. Citation2017; Van Dijk, Nieboer, and Cramm Citation2017; F. Zhang, Loo, and Wang Citation2021). Most publications primarily concern cross-sectional studies of a particular survey period, while studies evaluating longitudinal dynamic change remain insufficient. This leads to a one-sidedness in the study. Only by continuously focusing on the relationship between people and the environment from a dynamic perspective and implementing responsive measures, can we gain a more comprehensive understanding of their mechanisms and propose more reliable enhancement strategies.

To address the fact that many current facilities do not meet expectations after construction or fail to satisfy new demands during use, P-E Fit theory can be employed as a dynamic tool for promoting built environment improvements in the context of a dynamic society to sustainably promote a high quality of life. In the future, the longitudinal perspective of life cycle research should be introduced to observe the fit between people and the built environment at different stages of the project (e.g., before, during, and after design). Moreover, it can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of environmental improvements by comparing the fit changes and to identify the details that should be enhanced in future updates.

3.4. Proposing a new P-E fit model for sustainable improvement of the built environment

Considering the review results and the four knowledge gaps summarized herein, a new P-E Fit model for sustainable improvement of the built environment was developed (). The proposed model has the following strengths:

This model identifies the basic framework of the theory, with the person, environment, fit, and outcomes as the core components, and establishes the ultimate goal of fit as the creation of a high quality of life. Integrating key insights from the past literature, the objective and subjective dimensions are identified in the person and environment components. The objective dimension of a person refers to the objective demographic information that can be measured objectively; the subjective dimension includes self-perception and preference. The objective dimension of the environment refers to the attributes of facilities not influenced by subjective consciousness and can be measured objectively; the objective dimension refers to one’s perception of a specific facility. In the fit component, consideration should be given not only to how the person responds to the negative pressures of the environment, but also to how the environment meets the person’s proactive needs, which integrates Carp’s (1984) and Kahana’s (Citation1982) differences with Lawton and puts the proactive needs in a more important position. In the outcomes component, both psychological and behavioral consequences, positive or negative, will be considered.

This model demonstrates the mechanism containing all core components, including the relationships between subjective and objective dimensions, and the antecedents and the outcomes of fit, which is in line with the fundamental criteria of the theory emphasized by Edwards (Citation2008). On this basis, it further emphasizes that the subjective fit is the key to influencing outcomes, while the objective dimension of the person and the environment influence the subjective dimension.

This model emphasizes that the built environment should be proactively improved to support people’s needs and preferences. As emphasized by Kumar et al. (Citation2023), it is important to ensure that the environment are adapted to the person, rather than the person adapting to the environment. Enhancing the objective environment is the key focus of designers, policymakers, and managers, who should evaluate the effectiveness of these improvements by assessing fit in actual projects. Then, they can further improve users’ quality of life by increasing the fit between people and the built environment.

This model reveals the dynamic properties of P-E Fit in the context of a dynamic society, effectively actualizing Lawton’s (Citation1985) concept of change in research and practice, and will enhance the breadth and depth of the theory. With continuous changes to the personal and environmental aspects, even a fit that has been optimized for a certain set of conditions will change (i.e., get better or worse) over time, and therefore, it is necessary to continuously monitor the fit. When a misfit arises, it should be addressed and improved proactively. This concept also cautions designers and policymakers that built environment improvements should not be finalized as soon as the project is constructed. Instead, they should adopt a life cycle concept. To respond to the constantly changing conditions in both new construction and maintenance projects, it is crucial to regularly check the fit between people and the environment throughout the pre-design, design, and post-design periods (even during long-term use). This allows the built environment improvements to be guided within the concept of dynamic development.

3.4.1. Practical implementation

Overall, the proposed model reveals the comprehensive framework, core components, and their mechanisms within the context of the P-E Fit theory in built environment research. This can promote the refinement and development of the theory, while providing a sustainable foundation for built environment improvements in current and future projects. First, the model highlights a human-centered proactive improvement focusing on whether the built environment is fit for people as the core criterion for environmental evaluation. Therefore, in actual projects, it is necessary to comprehensively investigate the objective and subjective dimensions of the person and the environment, and assess whether the current built environment is qualified and whether the implemented improvements are effective through the evaluation of fit. A good example is Li et al.’s (Citation2021) design program in Nantou Village, where they used on-site photography, questionnaires, and interviews to investigate users’ objective factors (e.g., gender, age, education, occupation, marriage, place of birth, affordability of rent), and subjective factors (e.g., residents’ needs for rent, room size, historical atmosphere, and public space); and environmental objective factors (e.g., spatial pattern, building density, room area, rent), and subjective factors (e.g., residents’ perceptions of the current environment in terms of historical atmosphere and public space). The residential satisfaction that reflects the fit between people and environment, and the outcomes such as spatial behavior and willingness to renovate were also analyzed. Based on the analysis of people and environment components, and the assessment of the fit of the current situation, the initiative of the disadvantaged groups was fully developed. An inclusive reconstruction strategy was proposed to address the diversified needs of the disadvantaged groups in terms of rent, public space, and historical atmosphere, to achieve a comprehensive enhancement of the spatial quality and social network.

Second, the concept of dynamism is introduced, which emphasizes that improvements to the built environment should adopt a long-term life cycle perspective. Therefore, improvement work should not be considered finalized immediately after project completion. It is more important to continue to monitor the changes in the fit during long-term use. In this way, it is possible to constantly update the objective environment through programming, design, management, and operations to promote an effective long-term fit that would bring real and sustainable benefits. These aspects are critical in modern society, where personal and environmental factors are constantly changing. Recently, there have been many cases of exploring the whole life cycle evaluation of buildings. For example, the “Architectural Programming & Post Occupancy Evaluation Operation Process” proposed by Zhuang (Citation2017) emphasizes placing the needs of stakeholders throughout the whole project process, from demand identification to program design and construction, and then to the application of Post-Occupancy Evaluation (Preiser, Rabinowitz, and White Citation1988) in the use stage, to establish a whole-process operation and management methodology, and to achieve a continuous fit with the users’ needs in the long-term use stage. This approach has been applied to projects such as the National Biathlon Centre for the Beijing Winter Olympics (Zhuang and Zhang Citation2023) and the Yushu Administrative Center (Miao, Zhuang, and Chen Citation2020).

Therefore, the model will benefit researchers, designers and policy makers in the process of evaluating and enhancing the built environment: (1) Clarify work objectives. Built environment as a combination of art and function, the standard for evaluation has been controversial, this model emphasizes that person-environment fit becomes the goal of work, providing a clear standard, especially in the current human-centered developing context; (2) Strengthen the global awareness. Both in research and practice, the focus will shift from local elements to considering the local under the premise of grasping the overall mechanism, and being able to envision how local problems may affect subsequent performance; (3) Encourage a life cycle perspective. Moving from focusing on the fit state at a specific moment to focusing on ongoing dynamic development, which will more comprehensively grasp the fit between people and the environment, and will also motivate researchers, designers, and policy makers to think about how to enhance fit more sustainably rather than momentarily.

3.4.2. Suggestions for future research

However, it must be acknowledged that this model is a preliminary framework for building a bridge between P-E Fit theory and built environment studies. Thus, the proposed model is a broad and generalized framework that is designed to cover a wide range of built environment studies, and it should be considered as a starting point, rather than a final product. The following research concepts are worthy of further developments:

The proposed model provides a comprehensive foundational framework for demonstrating the mechanisms inherent to P-E Fit; however, this does not mean that future research must include all of the components of the framework. Under this framework, research efforts could separately explore different components (i) to elucidate the detailed mechanisms governing the relationships between subjective and objective dimensions or between fit and outcomes, and (ii) to develop more scientific measurement methods for evaluating fit. Addressing these issues can further refine and develop the P-E Fit theory in built environment research.

Based on the dynamic concept proposed in this model, it is possible to further integrate smart technologies (e.g., big data, artificial intelligence, and immersive technologies) in practice to develop dynamic assessment methods to conduct a dynamic life-cycle evaluation of the built environment from the user’s perspective (Kumar et al. Citation2023). Furthermore, the model emphasizes the importance of proactivity to further develop built environment improvement strategies and design methodologies for improving the fit for people.

Finally, by expanding the specific dimensions of the people, environment, fit, and outcomes in the built environment, the model would be able to cover more topics, or more specific multidimensional models could be developed (e.g., student-school environment fit, child-community environment fit, elderly-housing environment fit, staff-work environment fit).

After addressing these issues, the theory could become more rigorous and refined, and its applicability will be enhanced, making it a powerful, practical tool for studying human-environment relationships. As such, it can play a practical role in introducing sustainable improvements to built environments.

3.4.3. Critical analysis

In contrast to previous models, the proposed model has advantages regarding core components, mechanisms, proactivity, and dynamics. However, potential limitations have to be clarified:

The model emphasizes subjective fit as the primary cause of psychological and behavioral outcomes. Although this idea is consistent with important previous literature and is easier to obtain fit by direct measurement, many studies also explore objective fit. Since there is still no strong evidence to prove which fit has a more direct and accurate impact on outcomes in the built environment field, the exploration of objective fit should be encouraged. More importantly, it is necessary to compare the two fits, and the results may help to further improve the model proposed in this study.

The proposed model is a comprehensive foundational framework for future in-depth exploration. In contrast to existing case studies focusing on individual components, exploring all the components and their relationships in a single research case will result in a heavy task. Therefore, it is possible that all components of this global framework will not be fully implemented in practice. As described in the first point of the “Future research agenda”, the proposed global framework can be used as a foundation for more in-depth exploration of individual components. The results can be fed back to refine the mechanism further.

4. Conclusions

The fit between the person and the built environment is expected to be a major feature influencing a high quality of life. Considering the recent growth in the P-E Fit literature in the context of built environments, this study provides a critical review that identifies and discusses recent developments related to this topic. The dimensions and relationships among the core components (i.e., person, environment, fit, and outcomes) were summarized. The knowledge gaps were identified, including the narrow scope of the topics, the unclear mechanism, and the lack of proactive and dynamic views.

In order to address the knowledge gaps, this study proposed a new P-E Fit model for sustainable improvement of the built environment, which can serve as a foundation for future research. The model revealed the theoretical framework and emphasized the proactive and dynamic approaches for improving built environments to better meet people’s diverse needs and achieve sustainable long-term fit. Based on the proposed model, the theory can be refined by further clarifying the core components and the mechanisms through which they influence one another. The methodology for improving the built environment and the life-cycle dynamic assessment tool can also be developed further. Ultimately, an optimized theory could provide researchers, designers, and policymakers with tools for developing people-centered built environment research and practices based on P-E Fit theory.

To our knowledge, this study provides the first comprehensive review of P-E Fit studies in the context of built environments and to promote its application for improving such built environments. The discussions presented herein offer a starting point from which to stimulate innovations in the study of P-E Fit for improving built environments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Bankins, S., M. Tomprou, and B. Kim. 2020. “Workspace Transitions: Conceptualizing and Measuring Person–Space Fit and Examining its Role in Workplace Outcomes and Social Network Activity.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 36 (4): 344–365. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmp-09-2019-0538.

- Benita, F. 2021. “Human Mobility Behavior in COVID-19: A Systematic Literature Review and Bibliometric Analysis.” Sustainable Cities and Society 70:102916. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.102916.

- Bonaiuto, M., F. Fornara, S. Alves, I. Ferreira, Y. Mao, E. Moffat, G. Piccinin, and L. Rahimi. 2015. “Urban Environment and Well-Being: Cross-Cultural Studies on Perceived Residential Environment Quality Indicators (Preqis).” Cognitive Processing 16 (S1): 165–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10339-015-0691-z.

- Bonaiuto, M., F. Fornara, and M. Bonnes. 2003. “Indexes of Perceived Residential Environment Quality and Neighbourhood Attachment in Urban Environments: A Confirmation Study on the City of Rome.” Landscape and Urban Planning 65 (1–2): 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-2046(02)00236-0.

- Boone-Heinonen, J., B. M. Popkin, Y. Song, and P. Gordon-Larsen. 2010. “What Neighborhood Area Captures Built Environment Features Related to Adolescent Physical Activity?” Health & Place 16 (6): 1280–1286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.06.015.

- Bottini, L. 2018. “The Effects of Built Environment on Community Participation in Urban Neighbourhoods: An Empirical Exploration.” Cities 81:108–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.03.020.

- Büyüközkan, G., Ö. Ilıcak, and O. Feyzioğlu. 2022. “A Review of Urban Resilience Literature.” Sustainable Cities and Society 77:103579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2021.103579.

- Cable, D. M., and D. S. DeRue. 2002. “The Convergent and Discriminant Validity of Subjective Fit Perceptions.” Journal of Applied Psychology 87 (5): 875–884. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.5.875.

- Cable, D. M., and T. A. Judge. 1997. “Interviewers’ Perceptions of Person–Organization Fit and Organizational Selection Decisions.” Journal of Applied Psychology 82 (4): 546–561. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.4.546.

- Caplan, R. D. 1983. “Person-environment fit: Past, present and future.” In Stress Research, edited by C. Cooper. London: Wiley.

- Carp, F. M., and A. Carp. 1984. “A Complementary/Congruence Model of Well-Being or Mental Health for the Community Elderly.” In Elderly People and the Environment. Human Behavior and Environment, edited by I. Altman, M. P. Lawton, and J. F. Wohlwill, Vol. 7. Boston, MA: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2171-0_9.

- Chen, C. 2021. “What Makes Older Adults Happier? Urban and Rural Differences in the Living Arrangements and Life Satisfaction of Older Adults.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 37 (3): 1131–1157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-021-09882-5.

- Choi, Y. J. 2020. “Age-Friendly Features in Home and Community and the Self-Reported Health and Functional Limitation of Older Adults: The Role of Supportive Environments.” Journal of Urban Health 97 (4): 471–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-020-00462-6.

- Cotterell, J. L. 1991. “The Emergence of Adolescent Territories in a Large Urban Leisure Environment.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 11 (1): 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-4944(05)80003-9.

- Cvitkovich, Y., and A. Wister. 2001. “Chapter 1 a Comparison of Four Person-Environment Fit Models Applied to Older Adults.” Journal of Housing for the Elderly 14 (1–2): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1300/j081v14n01_01.

- De Vries, S., S. M. Van Dillen, P. P. Groenewegen, and P. Spreeuwenberg. 2013. “Streetscape Greenery and Health: Stress, Social Cohesion and Physical Activity as Mediators.” Social Science & Medicine 94:26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.030.

- Edwards, J., R. Caplan, and V. Harrison. 1998. “Person-Environment Fit Theory: Conceptual Foundations, Empirical Evidence, and Directions for Future Research.” In Theories of Organizational Stress, edited by C. L. Cooper, 28–67. England: Oxford University Press.

- Edwards, J. R. 2008. “Person–Environment Fit in Organizations: An Assessment of Theoretical Progress.” The Academy of Management Annals 2 (1): 167–230. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520802211503.

- Edwards, J. R., D. M. Cable, I. O. Williamson, L. S. Lambert, and A. J. Shipp. 2006. “The Phenomenology of Fit: Linking the Person and Environment to the Subjective Experience of Person-Environment Fit.” Journal of Applied Psychology 91 (4): 802–827. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.802.

- Elias, B. M., and S. L. Cook. 2016. “Exploring the Connection Between Personal Space and Social Participation.” Journal of Housing for the Elderly 30 (1): 107–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763893.2015.1129385.

- Fänge, A., and S. Iwarsson. 2005. “Changes in Accessibility and Usability in Housing: An Exploration of the Housing Adaptation Process.” Occupational Therapy International 12 (1): 44–59. https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.14.

- Farahani, L. M., P. Izadpanahi, and R. Tucker. 2022. “The Death and Life of Australian Suburbs: Relationships Between Social Activity and the Physical Qualities of Australian Suburban Neighbourhood Centres.” City, Culture & Society 28:100426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2021.100426.

- Fornara, F., A. E. Lai, M. Bonaiuto, and F. Pazzaglia. 2019. “Residential Place Attachment as an Adaptive Strategy for Coping with the Reduction of Spatial Abilities in Old Age.” Frontiers in Psychology 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00856.

- Francis, J., B. Giles-Corti, L. Wood, and M. Knuiman. 2012. “Creating Sense of Community: The Role of Public Space.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 32 (4): 401–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2012.07.002.

- Friesen, S., S. Brémault-Phillips, L. Rudrum, and L. G. Rogers. 2016. “Environmental Design That Supports Healthy Aging: Evaluating a New Supportive Living Facility.” Journal of Housing for the Elderly 30 (1): 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763893.2015.1129380.

- Gao, M., J. Ahern, and C. P. Koshland. 2016. “Perceived Built Environment and Health-Related Quality of Life in Four Types of Neighborhoods in Xi’an, China.” Health & Place 39:110–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.03.008.

- Gehl, J. 1987. Life Between Buildings. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Granbom, M., N. Perrin, S. Szanton, K. M. Cudjoe, L. N. Gitlin, and D. Carr. 2018. “Household Accessibility and Residential Relocation in Older Adults.” The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 74 (7): e72–e83. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby131.

- Guan, Y., H. Deng, L. Fan, and X. Zhou. 2021. “Theorizing Person-Environment Fit in a Changing Career World: Interdisciplinary Integration and Future Directions.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 126:103557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2021.103557.

- Guite, H., C. Clark, and G. Ackrill. 2006. “The Impact of the Physical and Urban Environment on Mental Well-Being.” Public Health 120 (12): 1117–1126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2006.10.005.

- Gunn, L. D., S. Mavoa, C. Boulangé, P. Hooper, A. Kavanagh, and B. Giles-Corti. 2017. “Designing Healthy Communities: Creating Evidence on Metrics for Built Environment Features Associated with Walkable Neighbourhood Activity Centres.” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 14 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-017-0621-9.

- Hacıoğlu, E., and Ç. Polatoğlu. 2023. “The Place-New Relation in the Context of Experience and Meaning: A Bibliometric Review (1992–2023).” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2023.2292075.

- Hanc, M., C. McAndrew, and M. Ucci. 2018. “Conceptual Approaches to Wellbeing in Buildings: A Scoping Review.” Building Research & Information 47 (6): 767–783. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2018.1513695.

- Hoendervanger, J. G., N. W. Van Yperen, M. P. Mobach, C. J. Albers, and M. O. Gribble. 2019. “Mechanisms of Resiliency Against Depression Following the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 65:101339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2019.101339.

- Hoffman, B. J., and D. J. Woehr. 2006. “A Quantitative Review of the Relationship Between Person–Organization Fit and Behavioral Outcomes.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 68 (3): 389–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.08.003.

- Huang, A. 2022. “A Network Model of Happiness at Destinations.” Tourism Analysis 27 (2): 133–147. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354221x16187814403100.

- Iwarsson, S. 2005. “A Long-Term Perspective on Person-Environment Fit and ADL Dependence Among Older Swedish Adults.” The Gerontologist 45 (3): 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/45.3.327.

- Iwarsson, S., V. Horstmann, G. Carlsson, F. Oswald, and H. Wahl. 2009. “Person—Environment Fit Predicts Falls in Older Adults Better Than the Consideration of Environmental Hazards Only.” Clinical Rehabilitation 23 (6): 558–567. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215508101740.

- Iwarsson, S., and A. Ståhl. 2003. “Accessibility, Usability and Universal Design—Positioning and Definition of Concepts Describing Person-Environment Relationships.” Disability and Rehabilitation 25 (2): 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/dre.25.2.57.66.

- Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

- Jao, Y.-L., W. Liu, H. Chaudhury, J. Parajuli, S. Holmes, E. Galik, and S. Meeks. 2020. “Function-Focused Person–Environment Fit for Long-Term Care Residents with Dementia: Impact on Apathy.” The Gerontologist 61 (3): 413–424. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa111.

- John, R. P. F., R. D. Caplan, and V. R. Harrison. 1982. The Mechanisms of Job Stress and Strain. London: Wiley.

- Jones, D., and C. Brischke. 2017. Performance of Bio-Based Building Materials. Duxford, United Kingdom: Woodhead Publishing.

- Junot, A. 2021. “Identification of Factors That Assure Quality of Residential Environments, and Their Influence on Place Attachment in Tropical and Insular Context, the Case of Reunion Island.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 37 (3): 1511–1535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-021-09906-0.

- Jusan, M. B. 2010. “Means End Chain, Person Environment Congruence and Mass Housing Design.” Open House International 35 (3): 76–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/ohi-03-2010-b0009.

- Kahana, E. 1982. “A Congruence Model of Person-Environment Interaction.” In Aging and the Environment: Theoretical Approaches, edited by M. P. Lawton, P. G. Windley, and T. O. Byerts, 97–121. New York: Springer.

- Kahana, E., L. Lovegreen, B. Kahana, and M. Kahana. 2003. “Person, Environment, and Person-Environment Fit as Influences on Residential Satisfaction of Elders.” Environment and Behavior 35 (3): 434–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916503035003007.

- Kaklauskas, A., and R. Gudauskas. 2016. “Intelligent Decision-Support Systems and the Internet of Things for the Smart Built Environment.” Start-Up Creation: 413–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-08-100546-0.00017-0.

- Kaplan, S. 1983. “A Model of Person-Environment Compatibility.” Environment and Behavior 15 (3): 311–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916583153003.

- Kim, K., T. Buckley, D. Burnette, and S. Cho. 2020. “Measurement Indicators of Age-Friendly Communities: Findings from the AARP Age-Friendly Community Survey.” Innovation in Aging 4 (Supplement_1): 51–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igaa057.166.

- Kristof, A. L. 1996. “Person-Organization Fit: An Integrative Review of Its Conceptualizations, Measurement, and Implications.” Personnel Psychology 49 (1): 1–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1996.tb01790.x.

- Kumar, S., S. H. Underwood, J. L. Masters, N. A. Manley, I. Konstantzos, J. Lau, R. Haller, and L. M. Wang. 2023. “Ten Questions Concerning Smart and Healthy Built Environments for Older Adults.” Building and Environment 244:110720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2023.110720.

- Lam, W. W., B. P. Loo, and R. Mahendran. 2020. “Neighbourhood Environment and Depressive Symptoms Among the Elderly in Hong Kong and Singapore.” International Journal of Health Geographics 19 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12942-020-00238-w.

- Lashani, E., and H. Zacher. 2021. “Do We Have a Match? Assessing the Role of Community in Coworking Spaces Based on a Person-Environment Fit Framework.” Frontiers in Psychology 12:12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.620794.

- Lawton, M. P. 1983. “Environment and Other Determinants of Well-Being in Older People.” The Gerontologist 23 (4): 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/23.4.349.

- Lawton, M. P. 1985. “The Elderly in Context: Perspectives from Environmental Psychology and Gerontology.” Environment and Behavior 17 (4): 501–519. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916585174005.

- Lawton, M. P. 1987. “Environment and the Need Satisfaction of the Aging.” In Handbook of Clinical Gerontology, edited by L. L. Carstensen and B. A. Edelstein, 33–40. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Lawton, M. P., and L. Nahemow. 1973. “Ecology and the Aging Process.” In The Psychology of Adult Development and Aging, edited by C. Eisdorfer and M. P. Lawton, 619–674. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10044-020.

- Lewin, K. 1943. “Defining the ‘Field at a Given Time.” Psychological Review 50 (3): 292–310. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0062738.

- Li, H., X. Zhang, S. T. Ng, M. Skitmore, and Y. H. Dong. 2018. “Social Sustainability Indicators of Public Construction Megaprojects in China.” Journal of Urban Planning and Development 144 (4): 4. https://doi.org/10.1061/(asce)up.1943-5444.0000472.

- Li, J., S. Sun, and J. Li. 2021. “The Dawn of Vulnerable Groups: The Inclusive Reconstruction Mode and Strategies for Urban Villages in China.” Habitat International 110:102347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2021.102347.

- Lien, L. L., C. D. Steggell, and S. Iwarsson. 2015. “Adaptive Strategies and Person-Environment Fit Among Functionally Limited Older Adults Aging in Place: A Mixed Methods Approach.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12 (9): 11954–11974. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120911954.

- Mao, Z., F. Wang, and D. Wang. 2022. “Attitude and Accessibility on Transit users’ Travel Satisfaction: A Person-Environment Fit Perspective.” Transportation Research Part D: Transport & Environment 112:103467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2022.103467.

- Mejía, S. T., L. H. Ryan, R. Gonzalez, and J. Smith. 2017. “Successful Aging as the Intersection of Individual Resources, Age, Environment, and Experiences of Well-Being in Daily Activities.” The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences gbw148. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbw148.

- Miao, Z., W. Zhuang, and J. Chen. 2020. “Demand-Oriented “Architectural Programming & Post Occupancy Evaluation” Operation Process Management Logic and Application.” Architecture Journal S1:175–178. https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=vdPasdvfHvvOtxOIABZJAK0bMy2qfi3GuMTWSd4yb4KU7cWvn4zAbaX-5GPjibN-xXne1FJyU9j3MocAvlX8wfye5GtWi9TyKX-YNhI1chMvhhWL9BkILnN6TckYR1GPilzbbkfpm39dvvPhCJvzZA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS.

- Moser, G. 2009. “Quality of Life and Sustainability: Toward Person–Environment Congruity.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 29 (3): 351–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.02.002.

- Muchinsky, P. M., and C. J. Monahan. 1987. “What Is Person-Environment Congruence? Supplementary versus Complementary Models of Fit.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 31 (3): 268–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(87)90043-1.

- Nygren, C., F. Oswald, S. Iwarsson, A. Fange, J. Sixsmith, O. Schilling, H. Wahl, Z. Szeman, S. Tomsone, and H.-W. Wahl. 2007. “Relationships Between Objective and Perceived Housing in Very Old Age.” The Gerontologist 47 (1): 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/47.1.85.

- Oswald, F., A. Hieber, H. Wahl, and H. Mollenkopf. 2005. “Ageing and Person–Environment Fit in Different Urban Neighbourhoods.” European Journal of Ageing 2 (2): 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-005-0026-5.

- Park, S., Y. Han, B. Kim, and R. E. Dunkle. 2015. “Aging in Place of Vulnerable Older Adults: Person–Environment Fit Perspective.” Journal of Applied Gerontology 36 (11): 1327–1350. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464815617286.

- Park, S., B. Kim, and Y. Han. 2017. “Differential Aging in Place and Depressive Symptoms: Interplay Among Time, Income, and Senior Housing.” Research on Aging 40 (3): 207–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027517697106.

- Park, S., and S. Lee. 2016. “Age-Friendly Environments and Life Satisfaction Among South Korean Elders: Person–Environment Fit Perspective.” Aging & Mental Health 21 (7): 693–702. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1154011.

- Parsons, F. 1909. Choosing a Vocation. Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin company.

- Pham, M. T., A. Rajić, J. D. Greig, J. M. Sargeant, A. Papadopoulos, and S. A. McEwen. 2014. “A Scoping Review of Scoping Reviews: Advancing the Approach and Enhancing the Consistency.” Research Synthesis Methods 5 (4): 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123.

- Phillips, D. R., K. H. Cheng, A. G. Yeh, and O. Siu. 2009. “Person—Environment (P—E) Fit Models and Psychological Well-Being Among Older Persons in Hong Kong.” Environment and Behavior 42 (2): 221–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916509333426.

- Preiser, W. F., H. Z. Rabinowitz, and E. T. White. 1988. Post-Occupancy Evaluation. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Roof, K., and N. Oleru. 2008. “Public Health: Seattle and King County’s Push for the Built Environment.” Journal of Environmental Health 71 (1): 24–27. https://org/www.jstor.org/stable/26327656.

- Rosso, A. L., A. B. Harding, P. J. Clarke, S. A. Studenski, C. Rosano, and S. Meeks. 2021. “Associations of Neighborhood Walkability and Walking Behaviors by Cognitive Trajectory in Older Adults.” The Gerontologist 61 (7): 1053–1061. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab005.

- Saelens, B. E., J. F. Sallis, and L. D. Frank. 2003. “Environmental Correlates of Walking and Cycling: Findings from the Transportation, Urban Design, and Planning Literatures.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 25 (2): 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2502_03.

- Saint-Onge, K., P. Bernard, C. Kingsbury, and J. Houle. 2021. “Older Public Housing tenants’ Capabilities for Physical Activity Described Using Walk-Along Interviews in Montreal, Canada.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (21): 11647. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111647.

- Stafford, G. E., and G. B. Gulwadi. 2019. “Exploring Aging in Place Inquiry Through the Lens of Resilience Theory.” Housing and Society 47 (1): 42–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/08882746.2019.1689088.

- Stokes, J. E., and S. Meeks. 2019. “Implications of Perceived Neighborhood Quality, Daily Discrimination, and Depression for Social Integration Across Mid- and Later Life: A Case of Person-Environment Fit?” The Gerontologist 60 (4): 661–671. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz103.

- Sun, Y., D. R. Phillips, and M. Wong. 2018. “A Study of Housing Typology and Perceived Age-Friendliness in an Established Hong Kong New Town: A Person-Environment Perspective.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 88:17–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.11.001.

- Thissen, F., and J. Droogleever Fortuijn. 2021. “‘The Village as a coat’; Changes in the Person-Environment Fit for Older People in a Rural Area in the Netherlands.” Journal of Rural Studies 87:431–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2020.07.001.

- Tsaur, S., Y. Liang, and W. Lin. 2012. “Conceptualization and Measurement of the Recreationist-Environment Fit.” Journal of Leisure Research 44 (1): 110–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2012.11950257.

- Van Dijk, H., A. Nieboer, and J. Cramm. 2017. “The Creation of Age-Friendly Environments Is Especially Important to Frail Older People.” Innovation in Aging 1 (Suppl_1): 37–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igx004.146.

- Van Haitsma, K., K. M. Abbott, A. Arbogast, L. R. Bangerter, A. R. Heid, L. L. Behrens, C. Madrigal, and B. J. Bowers. 2019. “A Preference-Based Model of Care: An Integrative Theoretical Model of the Role of Preferences in Person-Centered Care.” The Gerontologist 60 (3): 376–384. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz075.

- Weil, J., and S. Meeks. 2019. “Developing the Person–Place Fit Measure for Older Adults: Broadening Place Domains.” The Gerontologist 60 (8): e548–e558. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz112.

- Wister, A. V. 1989. “Environmental Adaptation by Persons in Their Later Life.” Research on Aging 11 (3): 267–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027589113001.

- Yan, B., X. Gao, and M. Lyon. 2014. “Modeling Satisfaction Amongst the Elderly in Different Chinese Urban Neighborhoods.” Social Science & Medicine 118:127–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.004.

- Yang, M., T. Y. Cho, X. Liu, and Y. Dai. 2023. “Research Status and Development Direction of Child-Friendly Cities: A Bibliometric Analysis Based on VOSviewer.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2023.2292082.

- Zhang, F., B. P. Loo, and B. Wang. 2021. “Aging in Place: From the Neighborhood Environment, Sense of Community, to Life Satisfaction.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 112 (5): 1484–1499. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2021.1985954.

- Zhang, Z., K. Fang, S. Zhang, W. Zhang, X. Wang, and N. Furuya. 2023. “Physical Environmental Factors That Affect users’ Willingness to Visit Neighbourhood Centres in China.” Building Research & Information 51 (5): 568–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/09613218.2023.2185583.

- Zhang, Z., and J. Zhang. 2017. “Perceived Residential Environment of Neighborhood and Subjective Well-Being Among the Elderly in China: A Mediating Role of Sense of Community.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 51:82–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.03.004.

- Zhuang, W. 2017. “From Architectural Programming to Post Occupancy Evaluation: A Feedback Mechanism of Architectural Procedure Circle.” Community Design 5:125–129. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-ZUQU201705031.htm.

- Zhuang, W., and J. Zhang. 2023. “The Development of Chinese Sports Architecture Design Under the Background of Whole-Process Consulting.” Architecture Journal 11:9–15. https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/jzxb202311004.