Understanding museums as tools for sustainable community development is one of the priorities of the international research project EU-LAC-MUSEUMS (2016-2020). This ambitious project has been explicitly designed in response to the European Union Horizon 2020 Work Programme call INT 12 (2015), ‘the cultural, scientific and social dimension of EU-LAC relations’. The project seeks to carry out a comparative analysis of small and medium-sized rural museums and their communities in Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean (EU and LAC), and to develop associated history and theory. By researching state-of-the-art initiatives in museums and community empowerment, and then moving beyond these initiatives to implement actions in partner countries, our aim has been both to transform individual lives within museum communities, and to create a method of implementation and evaluation that will be applicable to wider regions.

The basis of the project is that community-based museums allow under-represented communities to stake a place in history, as well as to contribute to environmental sustainability and community empowerment. Our project partners are The University of St Andrews in Scotland (Coordinator), ICOM, The Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, The National Museum of Costa Rica, The University of Austral in Chile, The University of the West Indies, The University of Valencia in Spain, and The National Archaeology Museum in Lisbon, Portugal. Our research themes are derived from the EU-CELAC Action Plan, namely:

| – | technology and innovation for biregional integration; | ||||

| – | museums for social inclusion and cohesion; | ||||

| – | fostering sustainable community museums; | ||||

| – | exhibiting migration and gender. | ||||

We are supported by an eminent Advisory Board and Steering Committee, including the Chairs of the ICOM Regional Alliances ICOM Europe and ICOM LAC (www.eulacmuseums.net).

A number of collective outputs could prove useful to local governments alongside the OECD-ICOM Guide, namely, On Community and Sustainable Museums, a Report on Policy Recommendations from a Round Table held at the European Commission, and a new ICOM Resolution on Museums, Community and Sustainability (https://zenodo.org/communities/eu-lac-museums).

Though many miles lie between us, working together as a bi-regional team has brought about cultural understanding, including: a transformative bi-regional Youth Exchange between Scotland, Costa Rica and Portugal; the launch of an art exhibition, Arrivants: Art and Migration in the Anglophone Caribbean World; a bespoke Virtual Museum; a YouTube channel; a Manual on Integral Museums: Experiences and Recommendations; researching traditional water heritage practices in southern Spain and northern Peru. The Peru case study represents our project in this issue of Museum International.

Sustainability has become fundamental to the work of museums. Since the early 1970s, ideas advanced by the ‘ecomuseum’ movement initiated by George Henri Rivière and Hugues de Varine have questioned the concept of the museum as a repository of collections, challenging institutions to look beyond the confines of their physical buildings.Footnote1 In the Latin American context, authors such as De Carli stress the need for museums to contribute to community development; to achieve this goal, institutions must get to know their communities. They should familiarise themselves with the local people and their beliefs, customs and values, as well as with other aspects of local cultural heritage (De Carli Citation2004b). One central idea that informs the EU-LAC-MUSEUMS project in several countries is that of a museum whose core initiatives and actions are anchored in local communities. The purpose of this article is to summarise the initiatives and findings of the EU-LAC-MUSEUMS Peru Case Study– developed within four museums in two regions on the Peruvian north coast– to nurture ties between these museums, their communities and local territorial development.

The discussion is divided into five parts: the first explores four museums where the project was developed, highlighting their shared history and the important relationships they have fostered with surrounding communities. The second part describes the project’s approach and the development of two intervention models that it applied, emphasising the challenges and reorientations the project faced due to the impact of the El Niño weather phenomenon. The third part describes the pilots (or ‘demos’) that were carried out in the countryside of the Chan Chan and Huacas de Moche Site Museums, both in the region of La Libertad. These served to verify the effectiveness of the actions that were implemented. The fourth section describes the activities carried out to strengthen relationships between museums and communities, particularly with regard to sustainability, regional integration, education, use of new technologies and climate change vulnerability. The fifth and final part highlights the preliminary conclusions of the project.

Case studies in the northern coast of Peru

The social vocation of museums was highlighted for the first time in the International Council of Museums (ICOM) Declaration of 1972 in Santiago, Chile.Footnote2 With the advent of New Museology during the 1980s, some questioned the authority of museums as institutions, instead calling for them to become instruments of representation and political power for the communities they serve (Rivière Citation1985; Fernández Citation1999; Palomero Citation2002). The incorporation of this criticism transformed the notion of the traditional and hegemonic museum into one ‘at the service of society and its development’, as stated in the resolutions of the 22nd General Assembly of ICOM in Vienna (Austria) in 2007. This concept has been especially relevant in Latin America, owing to its colonial history and diverse identities that, as a result, share a common social and political backdrop. In this context, the impact of international tourism has moreover prompted a reassessment of archaeological, cultural, natural, tangible and intangible heritage, which is now widely viewed as a resource for local development.

It is important to note that museums on Peru’s northern coast emerged in the aftermath of late 20th century discoveries, and were influenced by ideas around the social and educational vocation of museums. During this period, the decentralisation of neoliberal policies by Alberto Fujimori’s government led to the strong formation of regional identity, bolstered by the spectacular archaeological discoveries of the Muchik culture (Asensio Citation2013).Footnote3

This was coupled with strong investment from regional authorities seeking to develop the tourism potential of this archaeological heritage, resulting in the financing of spectacular excavations and museums. Since their creation, museums on the north coast of Peru have been influenced by the notion that museum institutions should more actively guide the public’s understanding of the meaning, use and protection of archaeological remains (Elera and Shimada Citation2006, p.217). Moreover, they have become important engines for attracting tourism, which in turn enhances local economies.

Selection criteria and institutional initiatives

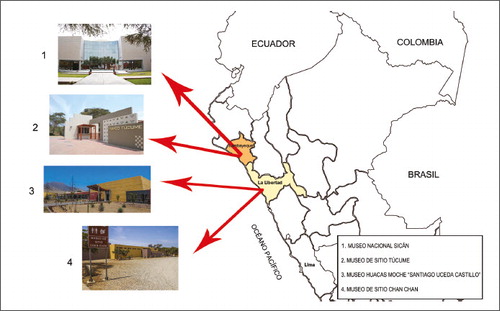

The choice of the four museums (Túcume, Sicán, Chan Chan and Huacas de Moche) discussed in this article was influenced by our interest in strengthening the ties that had previously been forged between these museums and their communities, and that have had a significant social and economic impact on a local level. The criteria informing the selection of these four museums also aligns with ICOM Peru’s objective of decentralising its discourses and actions within the Peruvian context.

The Sicán National Museum

In the case of the Sicán National Museum, for example, its community-oriented approach began with an initial archaeological excavation in 1978. The Sicán Archaeological Project (SAP) envisioned the Sicán National Museum as a centre for research, conservation and promotion of archaeological heritage, as well as an agent of sustainable development for the communities of the Ferreñafe province. This vision finally came to fruition in 2001 when the museum was inaugurated. Its community-oriented programme has materialised in a wide variety of initiatives.

This included the establishment of a long-term collaboration with the Local Educational Management Unit (Unidad Local de Gestión Educativa, ULGE), which helps develop school curricula in the province, promotes school visits and participation in the museum’s cultural activities, with the aim of developing the knowledge and value of the museum’s archaeological heritage. One of the activities organised by the museum is the annual festival, ‘Ferreñafe sings and dances for Peru’, which was created in conjunction with the local community to celebrate the cultural diversity of the province.

The museum has also consolidated its position as a reference for political and community agents in Ferrenafe, who work in the fields of conservation and environmental heritage defence. The Sicán National Museum is currently a member of several provincial committees, and has taken on a mentoring role with regard to territorial planning, education, the study of heritage and conservation and the development of tourism (Elera Citation2017). The north coast is an exceptionally fertile landscape, and pressures on local arable land have been constant, consequently affecting the relationship between museums and surrounding communities. This is precisely the case of the Sicán National Museum and its archaeological zone in the Pómac Forest, which have both been confronted by occupation and land trafficking.Footnote4 Having fostered a relationship with the communities that live in the buffer zones of the Pómac Forest, the museum has played a fundamental role in addressing this conflict, facilitating the recovery of lands for this now protected natural and cultural reserve.

The Túcume Site Museum

The Túcume Site Museum opened in 1992 and was renovated in 2014 as part of a community-oriented programme initiated by the Túcume Site archaeological project. The primary objective of the project was to involve the surrounding community in the ongoing preservation of the archaeological site and in revitalising local cultural traditions. This community-oriented approach led the museum to create a dedicated Office of Conservation Education (Oficina de Educación para la Conservación); the new office was designed to foster community involvement in museum activities, and in the ongoing preservation of local cultural heritage ().

Fig. 1. Location of the four museums that participated in the project, in the regions of Lambayeque and La Libertad (Peru). © Luis Repetto Málaga

This new office has allowed the museum to:

| – | promote community participation in the planning and activities of the museum, | ||||

| – | organise a series of meetings with local authorities to discuss urban and rural planning and heritage conservation, | ||||

| – | participate in the development of local school programmes to foster an appreciation for archaeological heritage and strengthen a sense of local identity among younger generations. | ||||

In addition, the museum’s onsite shop functions as a space for showcasing and selling works created by various groups of local artisans, and has become an important marketing platform for craftspeople in the community. Initiatives like these, among others, have facilitated the creation of enduring ties between the museum, local archaeological heritage and surrounding communities (Narváez Citation2017, p.32).

The Chan Chan Site Museum

The Chan Chan Site Museum, which was created in the 1990s, and the Santiago Uceda Castillo Huacas de Moche Museum, which was associated with a research project at the National University of Trujillo in 2010, have both proven pioneers in integrating technologies for conservation and in disseminating the importance of the heritage they protect. As such, these museums have become genuine emblems of regional identity. The Chan Chan Site Museum is currently undergoing renovations: it is once again incorporating new technologies into both its exhibitions and the on-site restoration and conservation of works.

Within this framework, these museums are notably developing projects and actions aimed at young people in surrounding communities – including school-age children in the capital city of Trujillo and other nearby urban areas –to reassess their link to heritage as a key factor in local development. Carrying out such projects during renovations was, moreover, presented as a unique opportunity for museums to strengthen relations with their communities, and this is reflected in how these institutions approached refurbishment projects.

Promises and challenges

The four museums selected as case studies have been working to strengthen the historically marginalised identities of rural populations in the territory, notably through activities that raise awareness around daily and traditional practices that are key to the cultural heritage of local populations. In this regard, these institutions have the advantage of existing relationships with local communities, working with them to promote the development of the territories or regions in which they are located. However, museums also face challenges arising from these same relationships: these include constant changes in the social, political and economic fabric of local territories, as well as climatic instability on Peru’s northern coast.

While such problems and challenges are certainly worth noting, the four museums discussed in this article greatly benefit from strong links to surrounding communities. In their respective contexts, these institutions have played key roles in transforming the attitudes of local populations, especially in relation to conservation efforts, encouraging locals to identify with their archaeological heritage, and increasing their capacity to generate economic income through tourism and other associated activities. This experience is also reflected in the four museums’ thorough knowledge of the economic, political, socio-cultural and environmental concerns of their communities. This local expertise has allowed the institutions to further strengthen community ties and formulate clear guidelines for their institutional work.

Project methodology: Territorial management and the El Niño phenomenon

The first year of the EU-LAC-MUSEUMS project was dedicated to coordinating and harmonising the proposal within the museums selected, which identified the relationships they had established with surrounding communities and articulated strategic approaches to reinforce these ties in areas of sustainability, regional integration, education and the application of new technologies. This initial planning phase began in September 2016 with the aim of being completed within seven months.

However, it had to be suspended between February and April 2017 due to the impact of the El Niño phenomenon: torrential rain caused landslides and serious flooding, which led to a state of emergency being declared in 12 regions of Peru. The project resumed in May 2017 and concluded in August of the same year. As a result of El Niño, the project design incorporated new elements, taking into account both the vulnerability of north-coast populations to this weather phenomenon and the pressing need to involve museums in territorial management. At this stage two intervention models were also defined, one to be applied to museums in Lambayeque (Sicán and Túcume) and the other to those in La Libertad (Chan Chan and the ‘Santiago Uceda Castillo’ Huacas de Moche Museum).

During the El Niño phenomenon, small-scale subsistence activities such as agriculture and artisan fishing were severely affected in rural communities. Even service activities such as micro-commerce or transportation were severely impacted by the destruction of road infrastructure. The number of people affected by this event exceeded one million. A third of the affected population, some 315,000 people, was located on the north coast, mainly in the regions of Piura, Lambayeque and La Libertad. These regions were subject to the catastrophic climatic alterations caused by El Niño until the end of April.

Prior to the El Niño events, it was common knowledge that museums and local communities were inadequately prepared to mitigate the effects of a climatic phenomenon of this magnitude. Any project based on Peru’s north coast should always take into account a recurrent and catastrophic phenomenon as part of its sustainability strategy. Accordingly, we consider it essential for museums to participate in coordinating disaster risk management actions, since they are institutions familiar with the characteristics and needs of the local environment.

Two intervention models and new initiatives

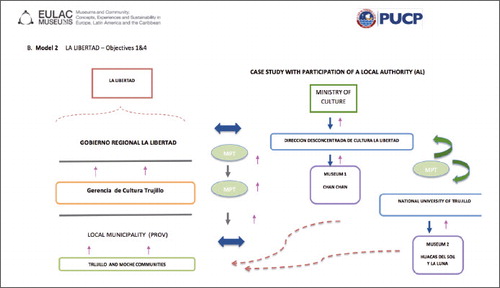

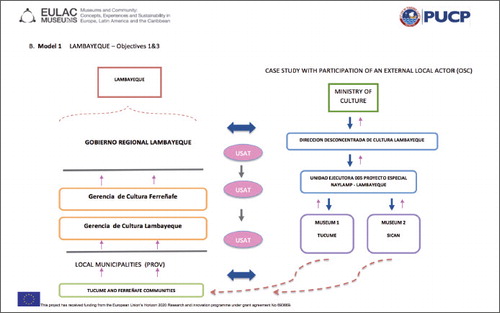

Two different coordination models were implemented for each respective region: in Lambayeque, interventions were to be carried out through an external and local actor, the University of Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo (USAT); this corresponds to the civil society actor approach. Meanwhile, in the region of La Libertad, the coordination model drew on the intervention of a more active local authority, the Decentralised Directorate of the Ministry of the Culture (Dirección Desconcentrada de Cultura del Ministerio de Cultura). The design of these two intervention models, conceived during the first year of the project, arose from a seven-month research period carried out by the EU-LAC-MUSEUMS project team from the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru. The result of these processes is discussed in the following two diagrams, which refer to how the Peru team will carry out its approach in each of the selected regions and their corresponding museums for the Peru Case Study ( and ).

Fig. 3. Model 1: Diagram describing the work scheme of the EU-LAC-MUSEUMS project for the Lambayeque region in Peru through links with local actors such as municipalities (directly linked to the structure of local, regional and national government) and museums (directly linked to the local and regional dependencies of the Ministry of Culture). © Luis Repetto Málaga

Fig. 4. Model 2: The actions carried out by the project on the communities of the La Libertad region will achieve both local and public policy impact. Throughout this scheme, the role of the University of Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo (USAT) is that of a mediator that ensures cooperation between all these entities and the success of the project activities. © Luis Repetto Málaga

Pilot studies: archaeological sites and nearby rural surroundings

From September 2017 to August 2018, the project initiated activities and workshops to strengthen ties between museums and communities, and two pilots were conducted at museums in the region of La Libertad, to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of these actions in compliance with the aforementioned objectives. The pilot studies also aided in identifying opportunities to improve institutional best practices around sustainability, particularly with regard to their relationships with local communities and environments. Pilot 1 was conducted in the nearby rural surroundings of the Chan Chan archaeological site, and Pilot 2 in the countryside of the Huacas de Moche site, both between March to August and December 2018.

Pilot 1: raising awareness around local ancestral knowledge

Pilot 1 consisted in a series of workshops focused on raising awareness around local ancestral knowledge. These workshops were developed and carried out by the Chan Chan and Huacas de Moche museums within their local communities. They notably discussed the traditional preparation of chicha de Jora and the cultural knowledge associated with this drink. After the workshop, participants learned about the process of preparing chicha de Jora and were encouraged to understand how this drink forms part of complex cultural knowledge associated with picanterías (restaurants serving spicy lunches), traditional gastronomic spaces and daily life.

Throughout the workshop, it became apparent that most local residents perceive local traditions as disappearing or in danger of extinction. For the participants of this workshop, communities and museums must act in partnership to preserve the local traditional culture, including the preservation of objects and raw materials, by promoting local practices associated with their use. In evaluating this pilot, we were able to conclude that the goal of achieving project sustainability would depend on our ability to strengthen the museum’s role in reviving popular traditions, as well as fostering the knowledge that is fundamental to the construction of local identities – ensuring these are not forgotten.

Pilot 2: Heritage preservation and environmental conservation in Moche

Pilot 2 was carried out in the countryside of Moche, and consisted of a series of interventions to raise awareness and encourage local communities to participate in the preservation of their environment and local cultural heritage. These interventions involved carrying out a series of meetings, during which both local authorities and members of their communities were invited to discuss and exchange ideas on how to promote the sustainability of museums and their communities. Discussions revolved around how to improve the relationship between archaeological projects and the local community, as well as how to promote water care to ensure the agricultural prosperity of Moche’s rural areas.

The pilot yielded a proposal aimed at establishing strategic alliances between the Huacas de Moche Museum, local educational authorities, and the cultural, religious and youth associations of the Moche countryside. The proposal’s primary aim was to plan and carry out actions designed to improve the environmental, economic and socio-cultural conditions of the local environment, favouring the preservation of local heritage with an emphasis on archaeological heritage.

During the pilot, a TV programme involving local schools was recorded at the Chan Chan archaeological site on 28 April 2018. As the highlight of our second ‘demo’, our team was in charge of recording a promotional spot at the archaeological site, with the support of site museum supervisors and the Chan Chan archaeological complex. The objective of this spot was to raise awareness among the local population around the conservation of cultural heritage – especially cultural assets built from mud architecture, of which the citadel of Chan Chan is an outstanding example. We toured the archaeological site of Chan Chan with children and young people from local schools, as well as their families and teachers, and stressed the value and validity of oral traditions surrounding this emblematic place; these are still alive in the collective memory of the community. The first TV programme was broadcast nationwide on 26 May 2018, at 11:30 a.m. by TV Peru as part of the ‘Museums Open Doors’ programme.Footnote5

Conducting these two pilots proved crucial: they allowed us to evaluate how selected museums and their communities responded to initiatives and actions we implemented to carry out our project. Moreover and above all, they allowed us to assess whether these actions succeeded in achieving the objectives that were initially set, and contributed to our goal of promoting more sustainable museum practices in relation to their local communities. Both pilots ultimately allowed us to reflect on how to improve the implementation of our project.

Project development: objectives and activities

The development of the EU-LAC-MUSEUMS project in Peru is based on the premise that museums have the capacity to significantly contribute to the cultural, educational and economic development of their communities through the recovery, assessment and conservation of their collective heritage and identity. Moreover, this contribution must be carried out through close collaboration between museums and the communities to which they belong. The four museums discussed here all enjoy strong relationships with their respective communities. The activities carried out as part of our project have sought to strengthen these relations in areas pertaining to sustainability, regional integration, education, technology and territory.

New models for sustainable museum practices

In Peru, the lack of a political framework defining the concept of sustainable museum practices from a top-down dynamic has forced local and regional museums to approach sustainability on their own terms. They have adapted the notion of sustainability to local contexts and forged their own set of good practices based on trial and error, but also based on intimate knowledge of their communities, territories and heritage. Accordingly, we designed activities to ensure that the four museums improved their contributions to the long-term development of their communities, strengthening and promoting the sustainable use of heritage as a resource to jointly address situations of local vulnerabilities and challenges. Existing relations between museums and communities have been strengthened, in part thanks to the participation of local authorities in the development of long-term policies and initiatives that benefit communities.

The only museums that we consider sustainable are those that recognise the economic, political, socio-cultural and environmental concerns of their territory as fundamental considerations in institutional management, and that involve and support community members in actions of preservation, appropriation, capacity building and the responsible use of heritage resources. Accordingly, the actions carried out within the framework of this project are geared towards generating processes that encourage museums to transform the way they work, their relationships with local communities, and their social and institutional contexts.

In the case of Lambayeque, Local Heritage Defence Workshops were conducted at each of the region’s museums. These were aimed at local authorities, leaders and public figures and promoted citizen participation in the assessment and defence of local cultural heritage. As a result of these activities, participants committed to forming a System of Heritage Defence Brigades (Sistema de Brigadas de Defensa del Patrimonio) in collaboration with regional museums and with supervision from local authorities. The latter are dedicated to protecting archaeological sites through patrol actions, as well as identifying and promoting the most emblematic cultural expressions in their respective area.

In the case of La Libertad, local museums conducted Local Knowledge Assessment Workshops, including one that focused on the use of totora reeds (scirpus californicus) and mate calabash (lagenaria siceraria) in the production of handicrafts. Another highlighted the practice of fishing and the traditional preparation and consumption of chicha de jora, while a micro-enterprise training workshop aimed to formalise the economic initiatives of participating communities. The overall purpose of the workshops was to highlight the importance of maintaining and continuing these traditional community practices. This empowered the local population to transmit ancestral knowledge in collaboration with the museums, which engaged several generational groups in the process.

Regional Integration for Social Inclusion and Cohesion

Actions pertaining to Regional Integration for Social Inclusion and Cohesion (Integración Regional para la Inclusión y Cohesión Social) sought to promote regional participation by helping local populations gain confidence around their regional identities and their ability to assess ancestral knowledge. The influence of the work of museums on their territories typically generates diverse impacts that reach beyond local contexts, and may affect regional dynamics around identity and heritage in both positive and negative terms.

We emphasise here the process of transforming relations between the four selected museums and their communities to establish a sense of belonging within the population. The overall purpose of this project is to foster greater cohesion between regional populations through the work of museums. It also aims to promote local cultures by creating more integrated regional societies in the long term, with individuals finding common ground by assessing their past and present heritage.

In the Lambayeque region, for example, the Túcume Site Museum is notable for its particular management model: one that involves the community surrounding the archaeological site in the institution’s decision-making process. However, it still struggles to involve sectors of the population mostly associated with the district’s urban centre, who seem less interested in preserving the cultural values that the museum promotes and protects. Moreover, while the Sicán National Museum is recognised by the communities of the La Leche river basin as an unconditional ally in the defence of local culture – thanks to its long history of working on multiple research, educational, tourism and heritage promotion initiatives – the museum still finds it difficult to fully commit to the specific needs of the multiple territories and communities under its jurisdiction.

The situation is similar in the region of La Libertad. In the case of the Chan Chan Site Museum, its efforts to preserve and disseminate information about the World Heritage Site have succeeded in elevating the mud citadel as an undeniable symbol of local cultural identity for all inhabitants in the region. Nevertheless, the museum still struggles to change the mindset of communities living nearby the archaeological site, so that they have an interest in preventing plundering at the site ().

Meanwhile, by working closely with certain local artisans, the Huacas de Moche Museum has managed to position a certain type of handicraft–inspired by the results of archaeological investigations at the site – as a hallmark of the region’s own quality. However, this has not lessened tensions between site archaeologists and the inhabitants of rural Moche: the latter continue to perceive the museum as an entity that has restricted access to and use of resources in many areas of the territory.

The activities developed at this above-mentioned museum aimed to bolster positive ties between museums and the local population by encouraging them to highlight the importance of their own territorial references, natural resources, cultural landscapes and artistic expressions inherited from the pre-colonial past, thereby consolidating their own local identities. These identities can, in turn, be grouped under the same regional identity component that consolidates the common past of all these communities, and that contributes to their unification as a collective people inhabiting the same territory: one that possesses common values and traditions based on cultural heritage, and that also faces common problems.

Systematising local knowledge and heritage

To that end, several Local Heritage Diagnostic Assessment Workshops were conducted by UNESCO expert Ciro Caraballo Pericci, which sought to identify, systematise and evaluate local knowledge and heritage values recognised by the population within the territorial scope of our four selected regional museums. The workshops led to a recognition that the local population plays an important role as transmitters of knowledge, ensuring the continuity of certain traditional local practices such as cooking, sewing or handicrafts production. They also spurred local authorities to commit to developing a training programme on participatory citizenship for younger generations: one that seeks to transmit the idea of the permanence of their community identities and cultural traditions. We firmly believe that these workshops, coupled with the other activities considered in our project, will contribute to achieving our objective of regional integration for social inclusion and cohesion. They do so by promoting unity among the population and instilling confidence in their cultural institutions, particularly through the recognition of heritage values common to inhabitants of the same territory.

To conclude this process, each of the regions staged a fair in which the experiences and results of the EU-LAC-MUSEUMS project were showcased. The region of Lambayeque held the EU-LAC-MUSEUMS Intercultural Fair, which involved the Túcume and Sicán museums, together with members of their communities: these included artisans, artists, producers, local authorities, managers and inhabitants. The fair showcased products that were created during the various workshops and project activities: new artisan designs, organic horticultural goods. It also staged video art presentations based on the local heritage of communities surrounding the Túcume and Sicán museums.

Meanwhile, the La Libertad region organised the first Cultural Identity Renaissance Week in the Moche countryside, for which the Huacas de Moche Museum created a programme to showcase rural Moche’s various culinary, artisanal, artistic and cultural expressions, developed within the framework of the project activities through fairs, parades, guided visits to the archaeological sites and festivals.

Collaborations with the Chile Case Study

To complement these efforts, the EU-LAC MUSEUMS project has shared insights from the Peru Case Study with the Chile Case Study, allowing the project’s Chilean colleagues to apply their ‘sustainability initiatives and documentation’, which were developed for museums in the Chilean region of Los Rios to counterparts of the Peruvian regions of Lambayeque and La Libertad. This provided these institutions with in-depth knowledge of the quotidian impacts of the programme’s proposed interventions on museums. The Chilean team’s methodology was implemented by the Peruvian team at the end of July 2018, allowing them to use the methodology developed by their colleagues in the Local Heritage Diagnostic Assessment Workshops once these were completed in the four selected museums.

Based on the information collected on Peru’s northern coast, the Chilean team found that knowledge about water management is one of the most valuable cultural resources of the communities on Peru’s northern coast: it allowed them to adapt to hostile desert conditions and transform the territory into a fertile valley, ensuring the survival and prosperity of local culture up to the present. In addition, carrying on from the bi-regional integration goal discussed in the working meetings of the EU-LAC-MUSEUMS project in May 2018, water was acknowledged as an essential element of cultural and heritage contexts, both in the case of Valencia, Spain (also an EU-LAC-MUSEUMS partner) and in the cases of Peru and Chile.

Accordingly, the consolidation and organisation of a joint programme between teams in Spain, Peru and Scotland was proposed, with the aim of sharing the experiences, knowledge, best practices and weaknesses of the organisations and relevant players involved in water management. Moreover, a pro-posal was put forward to discuss how the contribution of interdisciplinary knowledge from universities associated with the project can promote actions to link territories in bi-regional contexts. The overall purpose of this is to improve the sustainability of museum practices at all institutions participating in the EU-LAC-MUSEUMS project.

On World Water Day in Moche and following the initiative, judges from local utility companies Water of Valencia (Spain) and Water of Corongo (Peru), which are both recognised as intangible heritage of humanity, met with the irrigation board of the Moche countryside. This resulted in an exchange of enlightening knowledge and prompted self-reflection on the part of members of both countries.

Education as a key social function of museums

Education is one of the key social functions of museums and is central to their commitment to local communities. One key objective of this project concerns disseminating the research and work carried out by museums in their communities. However, it also inspires promoting dialogue between locals and experts regarding the interpretation of heritage in the territory they share. Through their educational work, museums effectively represent and transmit the cultural values of their communities, which serves to both raise the confidence of local groups around their own identity, and inform the rest of society of the importance of preserving this heritage.

For the Peru Case Study, our four selected museums maintain a commitment to their local communities by continuously developing initiatives designed to strengthen learning and knowledge about local traditions: ones based on the practices of the territory’s pre-colonial culture. This commitment translates into a clear intention to promote the creation and strengthening of regional identities, as well as a desire to promote local development through education and the appreciation of local heritage. By implementing actions that focus on education and disseminating knowledge about local culture, regional museums can help make their communities and territories more resilient in the face of any economic, political, socio-political or environmental challenges.

In the region of Lambayeque, the Túcume and Sicán museums worked to establish themselves as true centres of local culture by keeping their doors open to the community, and particularly through continually offering training workshops on a variety of topics. The central theme of the first workshops focused on the performing arts and self-expression through movement, as well as the use of audiovisual media and visual anthropology. These workshops were conducted in response to the local population’s need to increase their abilities to represent, and therefore contribute to preserve various expressions of local culture. These include dances, stories and performances linked to the oral memory of their community and the region’s pre-colonial past.

The central objective of the second set of workshops was to support local ventures and traditional practices, such as producing handicrafts, gastronomy and organic horticulture geared towards the tourism market. These workshops provided locals with a space for learning and sharing knowledge, with a view to improving their craft production processes – basketry, weaving and embroidery techniques – as well as updating their knowledge of agricultural production, much of which is passed down ancestrally. The workshop also addressed ways to specifically adapt to the local tourism market targeted by regional museums ().

In the region of La Libertad, the Chan Chan and Huacas de Moche museums carried out activities aimed at strengthening the identity of communities living around nearby archaeological sites. These activities mainly centred around heritage identity workshops, in which students from local schools participated by visiting the archaeological sites associated with museums, learning more about the daily work of these institutions and the latest research on local heritage. As complementary activities, community cleaning days of the buffer zones near these archaeological sites were also carried out, in order to preserve the environment and the landscape setting of the Chan Chan and Moche countryside; recreational activities were also conducted such as competitions, guided tours and painting murals, in order to increase the population’s knowledge of the work of local museums and the dissemination of main cultural and iconographic references at the archaeological sites of Chan Chan and Moche ().

In the region of La Libertad, the Chan Chan Site Museum developed a digital application and a new website to promote this World Heritage site. It also allows users to take a virtual tour of the museum’s facilities, with updated information on the latest research with respect to this heritage and the ancestral knowledge still present in the practices of local communities.

The Huacas de Moche Museum, in collaboration with the National University of Trujillo, created a video to promote the activities of the project among the community of rural Moche, disseminating the results to the citizens of the region.

Additionally, two TV programmes were produced on the subject of community museums – one for the region of Lambayeque and the other for the region of La Libertad – which were broadcast on free-to-air TV nationwide. These programmes detailed the current progress of the project, with a focus on its participatory approach and the importance of collaboration between museums and communities in achieving regional sustainability.

Natural disaster risk prevention

In addition to the objectives initially set, our project had to take into account a feature that characterises the two regions in which our four selected museums are located, and which affects the entire northern Peruvian coast in general: the El Niño phenomenon. The impact of this phenomenon in 2017 led to the interruption of project activities during part of the design phase. It also served as a stark reminder of the vulnerability of the northern coastal territories, where the process of social change hasbeen shaped by natural disaster events of this magnitude since pre-colonial times. Accordingly, we committed to develop activities related to natural disaster risk prevention as part of the project. The aim was to make the relationship between museums and their communities more sustainable by reducing the vulnerability of local territories, human groups and heritage that are impacted by natural phenomena.

In view of these objectives, each of the four museums we selected conducted natural disaster risk prevention workshops with local authorities, in order to raise awareness around the importance of preventing risk in the face of recurring natural phenomena, such as El Niño. Another aim was to prepare citizens to respond in case of emergency through mobilisation efforts, allowing them to protect their heritage and safeguard the integrity of their communities and livelihoods. As a result of these workshops, participating authorities signed a memorandum on integration with the local communities, committing to arrange future meetings to jointly develop community risk maps.

The museums and communities discussed have demonstrated their potential to promote actions and consolidate working models that strengthen museum institutions and their relationships with local communities and environments. More sustainable spaces can be achieved by improving relations between museums and their local communities, schools, families and the visiting public. Museums can only become true platforms that bring about sustainable development in their local environments by fostering in-depth knowledge of local realities, as well as recognising the history and heritage of local populations. Our project involved creating a series of activities, including joint learning workshops with specific objectives, methodologies and proposals; however, the overall goal of these was from the outset to strengthen ties between museums and their communities. Cultural heritage and local development represent the starting point and fundamental strategy at work in this endeavour.

Acknowledgement

This research received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme under grant agreement No. 693 669.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Luis Repetto Málaga

Luis Orlando Repetto Málaga is a museologist and a curator. Since 1979, he is the director of the Museo de Artes y Tradiciones Populares of the Instituto Riva-Agüero (Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú) and was the director of the Instituto Nacional de Cultura del Peru. Within ICOM, he is currently the vice-president of ICOM-Peru. He was President of the Committee from 1990 to 1998 and from 2009 to 2018, and President of ICOM-LAC from 2001 to 2007.

He is also a researcher in the Peruvian team of the EULAC Museos y Comunidades project, the president of the Red Peruana de Gestión y Valoración de Cementerios Patrimoniales and anchorman of the national television programme ‘Museos Puertas Abiertas’. In 2014, he was named Persona Meritoria de la Cultura by the Peruvian Ministry of Culture.

Luis Orlando Repetto Málaga published several books, among which Inventario de Términos para Museos, Guía de Museos del Perú (‘Arequipa’), and Lima, Patrimonio Cultural de la Humanidad. He is the author of the Peru case study.

Karen Brown

Karen Brown is Senior Lecturer in the School of Art History, University of St Andrews in Scotland. She is also Director of the University’s Museums, Galleries, Collections and Heritage Institute (MGCHI), teaching Museum and Gallery Studies. A Board Member of ICOM’s International Committee for Museology (ICOFOM), she previously served as a Board Member of ICOM Europe and ICOM Ireland.

A graduate of Trinity College, Dublin, she has published a number of works in museology and is currently overseeing several research projects relating to community heritage and sustainability with particular focus on Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean. From 2016-2020 she is coordinating an EU-funded Horizon 2020 international consortium project entitled ‘EU-LAC-MUSEUMS: Museums and Community: Concepts, Experiences, and Sustainability in Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean.’ (http://www.eulacmuseums.net).

Notes

1 Founding museologists of the ecomuseum movement and directors of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) from 1948 to 1965 and from 1965 to 1974, respectively.

3 This denomination was first popularised by the anthropologist and activist Richard Schaedel (1920–2005) in response to ethnographic work carried out by Enrique Brüning (1848–1928) on the indigenous people of Lambayeque. The term Muchik was used to refer to the mestizo-peasant communities descended from the indigenous people that inhabited the north coast of Peru since pre-colonial times, and to underline the continuity of their cultural traditions to date: approximately two thousand years. Although the use of their native language (the Yunga language, or Muchik) was already extinct, Schaedel (Citation1996) argued that the ‘essence’ of this people’s ethnic identity would remain associated with their continuous use of technology (including the management of traditional crops such as native cotton) and with the cognitive processes underlying their customs and beliefs (as in traditional medicine and curanderismo). Currently, this hypothesis is being explored further by researchers of the Sicán National Museum, who have also pointed out the importance of the influence of the Quechua people in the history of the north coast civilizations, having introduced the concept of a ‘Muchik and Quechua ethno-cultural matrix’ (Elera Citation2014, Citation2017).

4 Land trafficking can be defined as ‘the usurpation, illegal appropriation, and commerce of lands. It is closely linked with rural–rural and urban–rural migration and can be seen as an activity that organizes and facilitates migration’ (Shanee and Shanee Citation2016). See: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1940082916682957 [Accessed 25 November 2019].

5 The programme’s official trailer is available on YouTube under the video entitled ‘Museos Puertas Abiertas (TV Perú)– Ciudadela Chan Chan y Huacas Moche’. While the official version of the programme has not yet been published on YouTube, an unofficial upload can be found at the following link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jTPxr1rbzjg&t=2s [Accessed 25 November 2019].

References

- Asensio, Raúl. 2010. Arqueología, museos y desarrollo territorial rural en la costa norte del Perú. Proyecto Desarrollo Territorial Rural con Identidad Cultural (DTR-IC). Santiago, Chile: Rimisp, IEP.

- Asensio, Raúl. 2013 [Online]. ‘¿De qué hablamos cuando hablamos de participación comunitaria en la gestión del patrimonio cultural?,’ Argumentos, Vol. 7, No. 03-04. Available at: http://www.revistargumentos.org.pe/participacion_patrimonio.html [Accessed 3 September 2019].

- Asensio, Raúl. 2014. ‘Entre lo regional y lo étnico: el redescubrimiento de la cultura mochica y los nuevos discursos de identidad colectiva en la costa norte (1987-2010),’ in Etnicidades en construcción. Identidad y acción social en contextos de desigualdad. Edited by R. Cuenca. Lima, Peru: IEP, pp. 85–123.

- Borea, Giuliana. 2003. ‘Hablando de nosotros en un país pluricultural: identidad, poder y exotismo en los museos peruanos’, Arqueológicas, No. 26, pp. 267–275.

- Burón DIaz, Manuel. 2012. ‘Los museos comunitarios mexicanos en el proceso de renovación museológica’, Revista de Indias, Vol. LXXII, No. 254, pp. 177–212. doi: 10.3989/revindias.2012.007

- De Carli, Georgina. 2004b. Un Museo sostenible: museo y comunidad en la preservación activa de su patrimonio (1ª ed.). San José C.R.: Oficina de la UNESCO para América Central.

- De Carli, Georgina. 2004a ‘Vigencia de la Nueva Museología en América Latina: conceptos y modelos’, ABRA Magazine, Faculty of Social Sciences of the National University of Costa Rica.

- Elera, Carlos and Shimada, Izumi. 2006. ‘The Sicán Museum: Guardian, Promoter, and Investigator of the Sicán Culture and the Muchik Identity’ in Archaeological Site Museums in Latin America. Edited by H. Silverman. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

- Elera, Carlos. 2017. ‘El quéhacer institucional del Museo Nacional de Sicán en la cuenca de La Leche, Lambayeque’, in Quingnam, Vol. 3, January – December. Trujillo: UPAO, pp. 35–60.

- EULAC MUSEUMS Project Peru Case Study. n.d. Interim Report Nr.3. Lima: Pontifical Catholic University of Peru.

- EULAC MUSEUMS Project Peru Case Study. n.d. Interim Report Nr.2. Lima: Pontifical Catholic University of Peru.

- EU-LAC-MUSEUMS Project Peru Case Study. n.d. Interim Report Nr.1. Lima: Pontifical Catholic University of Peru.

- Fernández, Luis A. 1999. Introducción a la Nueva Museología. Madrid: Alianza editorial.

- Narváez, Luis A. 2017 ‘Patrimonio, territorio y comunidad. El ecomuseo Túcume’, Quingnam, Vol. 3, January—December. Trujillo: UPAO, pp. 19–34.

- Palomero, Santiago. 2002. ‘¿ Hay museos para el público?’, Museo, No. 6, pp. 141–157.

- Riviére, G. H. 1985. ‘Definición evolutiva del ecomuseo [Evolutionary definition of the ecomuseum]’, Museum, XXXVII, Vol.37, No. 4, pp. 182–184.

- Schaedel, Richard. 1996. Recolección histórica-etnográfica sobre la problemática Muchik. [Historical-ethnographic collection on the Muchik problem]. Lima: Manuscript.

- Shanee, Noga and Shanee Sam. 2016. [Online]. ‘Land Trafficking, Migration, and Conservation in the ‘No-Man’s Land’ of Northeastern Peru’, Tropical Conservation Science, October-December, pp. 1–16. Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1940082916682957 [Accessed 18 November 2019].