The struggles of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex individuals and groups to express their differences, demand social justice and reclaim a place in historyFootnote1 are not new ones. In the 1960s, the earliest demonstrations from LGBTQI+ activists against police repression in the public space were centred around demands for visibility, equal rights and social representation. Today, more than 50 years after the landmark Stonewall riots in June 1969, we can say that several groups and organised movements around the world use cultural tactics and memory-based projects as important tools in their demands for equal rights and inclusiveness in the public sphere (see Sandell Citation2017). These affirmative strategies of LGBTQI+ minorities have substantially increased since the mid-1980s, in a movement that was spurred in part by the global spread of the HIV/ AIDS epidemic. Among the tragic consequences of this historical event was the death of thousands of gay men, as well as other marginalised groups, such as drug users, sex workers, trans people, migrants, etc.—due to governmental neglect as denounced by the ACT UP movements around the globeFootnote2. From these terrible events emerged a sense of cultural loss among LGBTQI+ people, but also the rise of a collective awareness that restoring this culture as well as breaking the chain of viral transmission was imperative. It was in this context, in 1985, that the GLBT Historical Society (San Francisco) and the Schwules Museum (Berlin) both presented in this issue, were created.

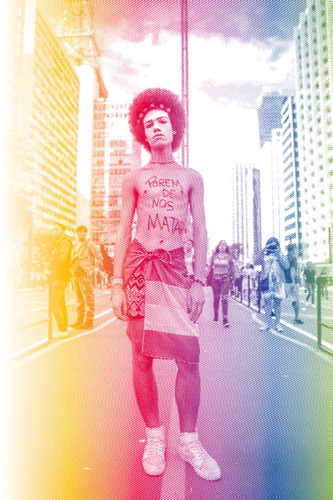

During this crisis a connection was drawn between the collective experience of death and the need for remembering. Meanwhile, stories of gays and lesbians in the public sphere were documented more frequently through memorials than through museums, as underlined by Amy K. Levin (Citation2010, p. 4), and through the musealised traces of their absence or extermination, such as pink triangles (symbols of the persecution of homosexuals by the Nazis during World War II) at Holocaust museums in Berlin, Washington, and elsewhere. In some places, this ‘mourning museology’ is still the most common way to transmit the memory of LGBTQI+ public figures, as attests the contemporary example of Marielle Franco, a Brazilian councilwoman, black lesbian, and human rights activist in Rio de Janeiro who was murdered on 14 March 2018. Her memory inspired the opening of the Marielle Franco Institute, an NGO and memory centre in Rio, whose mission is to fight for justice and spread Franco’s legacy to future generationsFootnote3. But can’t— and shouldn’t—we celebrate living LGBTQI+ individuals as well? Shouldn’t memory institutions and museums be concerned with collecting and curating the traces of our present existence in order to celebrate our lives?

To come back to the turning point of the 1980s, we can identity two main processes within the museum sector related to the struggle to expand LGBTQI+ visibility and representation: one centres around the integration and inclusion of LGBTQI+ cultures and narratives in traditional heritage institutions, while the second is experimentation within community-based and autonomous initiatives—in spaces that operate outside of mainstream discourses and power structures. This is not to suggest that those two trends cannot cross at multiple points. This issue presents numerous examples of possible collaborations (and their potential challenges), as well as internal evolutions in both mainstream institutions and community-based counterparts.

Using a range of tools and frameworks (French theory, queer theories, decolonial perspectives, critical historiography, feminist epistemologies, etc.), academics and activists have, over the years, keenly observed and researched the colonial, patriarchal and heteronormativeFootnote4 foundations of museums—and the attached ‘science’ of museology. At the same time, certain museums have begun questioning their public role and responsibilities with regard to marginalised populations and minority groups. Commonly perceived as traditional institutions whose aim is to transmit the past, thereby preserving and reproducing certain inherited categories and artefacts, museums can serve to normalise the present. They are historically attached to hegemonic power structures, and from the rise of modernity they have participated in the governing of bodies and imaginaries. As many museologists have underlined in recent analysis, museum theory and practice continue to be influenced and determined by heteronormativity, reproducing in the present the ‘invisible knapsack of heterosexual privilege’ (McIntosh Citation1989; Nguyen Citation2018, p. 3).

Organised movements and activists have increasingly questioned museums’ exclusionary representations and narratives, critiqued their past and present relations with dominant groups, and cast light on their general omission of LGBTQI+ histories, publicly denouncing and openly scrutinising the practices of traditional museums.

This potential intrusion in museums’ institutional practices—from minority groups that have generally been excluded from official policies around the preservation of cultural heritage—has led to the critical and progressive transformation of the museum forum, yielding the multiplication of anti-normative initiatives within mainstream institutions. These have ranged from museums proposing ‘queer’ readings of known collections, either granting visibility to themes around gender and sexualities, or ‘including’ LGBTQI+ audiences and activists in museums’ curatorial processes and exhibition-making. But are these recent compensatory developments adequate responses to critiques made by activists and scholars from the 1970s onward? Do they help to identify the voids, blind spots and omissions still present within museums? Are they based on a true and enduring awareness surrounding these minority groups? Are such relatively profound transformations imaginable or possible everywhere, even in hostile political contexts? The present issue invites us to closely consider several experimental initiatives: ones that prompt the museum to be reconceived outside of the frameworks of inherited heteronormativity, and to move beyond its current limitations to more fully represent and transmit diversity.

Closet museums?

Museums generally operate in a symbolic closet: one that has defined the lives of LGBTQI+ people throughout history. From their 17th-century origins as early cabinets of curiosity, museums initially assumed the role of holding selected treasures, inaccessible to broad society and only displayed in very specific and private contexts. Redefined, in the centuries that followed, as public spaces (Mairesse Citation2005) museums selected and curated collections to decide which parts of them would be open to audiences, and which parts would remain protected in reserves. Since early modernity, museums were not only tasked with selecting which artefacts had value to societies, but also who would be allowed access to their collections. In the first museums, both private and public, only the ‘wise men, the savants, the amateurs and the artists’ (Ibid, p. 8)—an audience essentially composed of white cis males—were allowed to access the proverbial closet.

Operating according to the logic of the visible— in contrast with the logic of the hidden, the cloistered or relegated to the shadows—museums are similar to the closet of sexual and gender identities. By using closed categories and hermetic methodologies, they help to maintain certain social boundaries and to normalise discourses on gender, sexuality and race. Echoing authors such as Jennifer Tyburczy (Citation2016), who pursues Foucault’s project of locating ‘intertwining systems of representations for display of biopolitical techniques’ (p. 9), we argue that the genealogy of museums, as biopolitical devices, continues to produce exclusions and violence when they reproduce the contemporary capitalist production of sexual and gender-based social norms.

As a defining metaphor for queer oppression, the closet has moulded the social life of LGBTQI+ communities and forged a culture centred around the dichotomy of in and out, or public and private. Such a dichotomy has also been central to understanding the various impulses that have spurred the creation of autonomous, community-based LGBTQI+ museums. In this way, the closet is not only a reclusive space for hidden figures or objects. With the yet-to-be-fully realised, and inherently precarious, visibility of LGBTQI+ cultures, these communities and individuals have explored the potency of their secrets and the power of their hidden narratives—not all of them exposed in museums. As Eve K. Sedgwick proposes, the closet, or the ‘coming out’ of it, can bring about ‘the revelation of a powerful unknowing as unknowing, not as a vacuum or as the blank it can pretend to be but as a weighty and occupied and consequential epistemological space’ (Citation1990, p. 77). This revelation around the unknowing of LGBTQI+ culture and social existence—a recognition of the private spaces where transitory identities can flourish—is a common feature of LGBTQI+ museums, which often produce, in the public space, a creative extension of ‘open closets’. They unearth private identities that were supressed or that remain underrepresented in the blind spots of heteronormative institutions. These museums and queer museologies show how it is sometimes necessary not to know in order to find new ways to include excluded subjects in the framework of cultural representations and memory regimes (Brulon Soares Citation2020a). The act of coming out of the closet is a revelation as much as it represents the denunciation of a structural omission. It shakes the foundations of the museum as a temple that celebrates continuity by merely reproducing gender roles and sexual norms.

Shaking museology

The performative work of ‘coming out’ has historically involved an individual publicly stating their sexual or gender identity to themselves and to others. Public visibility has been an important part of the LGBTQI+ movement, and is a principle that is directly connected to the global boom in LGBTQI+ museums and exhibitions in the 21st century. Perceived as a recent phenomenon, the coming-out stories told by LGBTQI+ museums around the globe are embedded in a wider chain of transformations in the field of museums: ones that date to the 1960s and 1970s. The well-known international movement of New Museology, recognised as a contestation of traditional practices in traditional museums (Desvallées Citation1992), has also been perceived by many as an antinormative, decolonial and anti-elitist movement animating the heart of the international museum field (Adotevi Citation1992 [1971]; De Varine Citation2005). Rooted in social claims for decolonisation and inclusion, this movement sought to transform museology, moving it away from its inherited traditionalism. As a result, museums aimed to develop a more active role towards societies (UNESCO Citation1973), finding new ways to engage a broader audience and to include minority groups in the democratisation of the museum forum (Cameron Citation1971). These new developments that marked the end of last century and represented the emergence of social museologies (Chagas and Gouveia Citation2014) and museums based on social experimentation would strongly resonate in Europe, but they would most markedly proliferate in the context of colonised countries in the Global South (see, for instance, the works discussed in Brulon Soares Citation2020b).

New Museology and the subsequent developments of social museologies, however, were not particularly preoccupied with addressing LGBTQI+ issues. Gender museology and queer approaches to the museum would only become eminent in the second decade of this century, notably through the work of feminist and queer museologists with diverse backgrounds (see Levin Citation2010, Levin and Adair Citation2020; Steorn Citation2012; Rechena Citation2012; Chantraine Citation2017; Boita Citation2018; Nunes Citation2019; Sandell, Lenon and Smith Citation2018, among others). These approaches would gain visibility and relevance in the broader museum field with the organisation of specialised networks. Bringing together activists, scholars and museum professionals, as well as different kinds of expertise, such networks include Queering the Collections in the Netherlands, LGBT History Months (US, UK, Canada, Australia, Hungary, Ireland), and the Network of LGBTQI+ Archives, Museums, Collections and Investigators (AMAI LGBTQI+), the latter connecting the experiences of community-based institutions devoted to the memory and histories of sexual and gender dissidences in Latin America and the CaribbeanFootnote5.

The idea that museums can contribute to queer antiformalism and antinormativity can be perceived as a paradox in principle (Mills Citation2008; Chantraine Citation2019). ‘Queer’ is a subverted term used to refer to anything that disagrees with the norm, the dominant, and the normal; it is not defined in positive terms, nor as a fixed identity. In the realm of cultural expression, the notion of ‘queer theory’ was used for the first time by the feminist writer Teresa de Lauretis, in 1989, reflecting a dissatisfaction with the established frameworks for social representation in visual artsFootnote6. It follows that the term ‘queer’ would subsequently be assimilated by social movements launched by sexual and gender dissidences. In some contexts, within the LGBTQI+ community it is used to refer to any expression of antinormative identity, while in others, groups such as transgender collectives in Latin America argue that queerness cannot in any sense be confounded with an identity, understood instead as a general antinormative concept—hence the preference for the acronym LGBTI+ by many in the region.

In confronting well-established structures of power and domination, sexual minorities can find relative safety and ease when ‘included’ in the normative institutions that historically excluded them, and without first changing embedded power relations. As the Brazilian activist Jota Mombaça (Citation2017, p. 303) stresses, the apparent ease in the acronym LGBTQI+ ‘is a sign of the lack of political and intersectional imagination of these activisms’. For Mombaça, to name the norm and to identify its disciplinary effects is only the first step toward a ‘disobedient redistribution of gender and anticolonial violence’ (Ibid, p. 306). It is also worth mentioning that while some white gays and lesbians may feel represented and included in mainstream museums and ‘progressive’ exhibitions, the same museums that include them continue using disciplinary methods adopted by normative institutions to exclude trans and black people, or other sexually dissident or gender non-conforming people and groups who are less visible and accepted in the supposedly all-encompassing LGBTQI+ acronym. If, in the history of museums, display ‘became a mode for staging modern state techniques for subjugating certain bodies and practices and celebrating others’ (Tyburczy Citation2016, p. 9), queer museology should be understood as a constant element of unease that obliges institutions to defy their own frames of representation and constructs of ‘inclusiveness’.

Beyond the re-politicising of sexuality through questioning the formative centres of normative identities of sex and gender (Bourcier Citation2018, p. 149), queerness can be understood as ‘not yet here’ and ‘as an ideality that can be distilled from the past and used to imagine a future’ (Muñoz Citation2009, p. 1). Thus, queering the museum, in the conception of contemporary critical museologists, implies calling into question the regimes of knowledge and truth in which the modern public museum is founded (see, for instance, Sullivan and Middleton Citation2020). At the same time, queer museology represents a creative provocation and a rupture with the traditional core functions, theories, practices and methodologies of the museum as we know it.

If a queer museology based on queering the museum’s known functions and principles is put into practice, museums can reinvent themselves in drag—and consequently reinvent temporality by displaying alternative histories. Understanding someone’s self-representation in drag as the act of plastering the body with outdated materials, rather than simply cross-gendered accessories, Elizabeth Freeman proposes that the queer can indeed talk back to history (Citation2010, p. xxi) binding time in the definition of new relations to the past and, as a result, projecting other presents and futures. By proposing new interpretations for old objects and behaviours, museums might be able to queer our own relationship to time, as social beings with shared chronologies. In this utopian reality, there would be no limits for museums’ imaginative power in their creative agency in the present.

The rise of LGBTQI+ museums: inventing new forms of transmission

One of the reasons for the forging of activist museums from the forgotten traces of LGBTQI+ lives is the symbolic eviction of the patriarchal structure: one that forms the very foundation of institutions dedicated to the preservation of cultural heritage. In French, the term is patrimoine, while in Portuguese it is patrimônio; the Latin etymology for both of these refers to a patriarchal logic of transmission of goods and legal rights from fathers to sons (for a critical feminist analysis of the French patrimoine, see for example Hertz Citation2002). By coming out of their closets and participating in the narrative of new, redefined queer museums, LGBTQI+ communities, fighting for memory and survival, have invented a new logic of transmission: one that Michael Petry (Citation2010) calls ‘horizontal history’, a term that describes how stories, memories, or information have passed from one same-sex lover to another. The author argues that unlike the dominant culture’s vertical transmission of history (one reproduced by most public institutions), ‘queer people have had to devise alternative means of keeping their excluded history viable’ (Ibid, pp. 153-154). As several others have argued, LGBTQI+ people are the only minorities whose culture is not transmitted through familial relations, which partially explains the precarious ‘nature’ of queer culture. Owing to this structural characteristic, LGBTQI+ communities and individuals have to rely on other forms of non-vertical associations within their communities, in networks built by lovers, sexual partners, friends, ex-lovers, activists, neighbours, etc., creating new forms of communal transmission based on ties of desire, solidarity, affect and empathy.

It seems clear that the appropriation of the term ‘museum’ by LGBTQI+ communities can be seen as a desire to challenge traditional methods and norms for heritage preservation and cultural transmission. In the past few decades, the creation of new and often fluid ‘institutional’ models has produced an unprecedented visibility around the lives, issues and specific claims of the heterogeneous groups of communities identified in this affirmative acronym.

If the right to memory is a human right that should be enjoyed by every individual, the right to conceive a museum and open displays should be one secured in the public sphere. Minorities should be empowered, and have the means, to preserve their own historical references and memory, in order to contest the established present. This issue of Museum International is a call for the museum field and its professionals to engage in the debate on LGBTQI+ representation in museums, not by proposing normative forms of democratisation and inclusion, but rather by putting into friction different museum-related expressions, agencies, subjectivities and imaginaries developed by the communities represented in this acronym. This level of engagement may have the effect of disrupting the very norms that define and encapsulate those communities in the present.

Editorial

This issue was conceived and edited as an attempt to queer the museum literature by showing some of the most transformative and challenging initiatives of LGBTQI+ museums throughout the world. As white-cis gay museologists living in different continents and having been exposed to different museum experiences, we accepted the role of guest editors for this issue, taking on the responsibility of ensuring diversity and intersectionality in the articles selected, and of offering a plurality of viewpoints. While taking into consideration the latest attempts at formal inclusion in mainstream museums, the focus of the present issue is the current and evolving bloom of community-based LGBTQI+ museums and initiatives, as well as their struggle for autonomy throughout the world.

How is their autonomy conceived, and who authorises it? What is the price for this autonomy in politically and socially hostile contexts? What sorts of strategies are implemented in communities that are themselves plural and diverse, and how do they allow minorities to construct counter-narratives within them? What sorts of relationships, collaborations and creative frictions can be developed through partnerships with traditional museums? As the articles presented in this volume show, LGBTQI+ museums conflict directly with the hegemonic dominance of general institutions dependent on nation states, and with the dynamics of a global market that tends to erase differences, or eliminate the bodies that generate friction. Some of the experiences presented here raise social and political challenges and obstructions faced by these autonomous initiatives, while others defy the historical foundations of museums in the contemporary era, suggesting new ways to subvert them.

Part I: Affirmations and Frictions

The issue opens by exploring some of the emblematic initiatives and museums driven by activists, as well as discussing their impact on local communities and social life. As expressed in the narrative of Brazil-based museum director and activist Franco Reinaudo, these communitybased museums present themselves as nodal points for cultural and political resistance, surviving and thriving as ‘strange bodies’ that generate significant friction while negotiating their queer existence. Considering the queer as the anti-representation of known expressions of sexual and gender identities, these museums have shown that, by shaking museology’s normative core, they can in fact produce new methods for cultural transmission, requalifying certain subjects and political views that until now have remained ‘in the closet’ within museum collections. As a result, in most cases, creating a museum becomes a political tool for affirmation and a method of resistance in itself, while allowing communities to find their own sense of belonging by strengthening ties among their members.

But far from romanticising battles for social representation and political affirmation, the selected articles narrate a fundamental struggle. Whether we consider the Museum of Sexual Diversity, situated in an underground station in São Paulo, or the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society in San Francisco, activist museums struggle, owing to the fact that they are constantly challenging the rules reproduced by other heteronormative institutions. In their conversation for this issue, the historians and curators Gerard Koskovich, Don Romesburg, and Amy Sueyoshi consider the history of the GLBT Historical Society as a communitybased queer public institution that has evolved, since its foundation in 1985, to recognise diversity within the community it represents. As one of the oldest historical initiatives of its kind, it has been defined, throughout its 35 years of existence, as a largely volunteer-driven organisation: one whose transformative work is based on grassroot strategies and the personal involvement of community members.

The first exhibitions that considered sexuality and gender as relevant topics to be approached in museums had to confront the fact that these topics were not necessarily narrated in existing museum collections. When recalling a major exhibition in 2009 at the Vietnam Museum of Ethnography— one commemorating 20 years since the first HIV diagnosis in Vietnam—artist and curator Dinh Thi Nhung shows how the topic of LGBTQI+ representation immediately raised questions on collecting that changed the museum’s perspective on its own methods, and called attention to an urgent need to assemble LGBTQI+ archives in the Vietnamese context. However, in most of the cases presented in this issue, it is members from local communities who propose new ways of collecting and archiving LGBTQI+ references. Often operating with scarce financial support, these activists’ experiments tend to be based on unpaid professionals working for the preservation of a community heritage that is also their own affirmation as part of a group. As Nhung demonstrates, while the unpaid work of these activists is a sign of strong commitment to the cause, it also shows the lack of (private or public) investment in these kinds of projects.

In some of the deeply personal narratives presented here, curating LGBTQI+ exhibitions and museums is not about the expression of an institutional point of view, but a creative means of affecting the lives of those involved in the very process of curating or making a museum. By exploring her personal experience of coming out of the closet to embrace her own ‘research-creation’ expression, Virginie Jourdain exposes discriminatory hierarchies in the domains of culture and arts, both in the contexts of Canada and France. Her article aims to illuminate a few of the strategies adopted by queer activists in their artistic labour of creating political art. In it, she follows the work of marginalised groups, including Canadian First Nations people, in their fight for representation, while calling attention to institutional violence and the risk of co-optation.

The experiences represented in this issue show how museums matter to life in the present, in their ability to change our sense of belonging or to revise our own ‘history’ in today’s world—a task that may prove to touch sensibilities and to expose deep wounds. As Amy K. Levin underlines in her article, museums also serve to provoke their audiences by raising difficult issues and sensitive topics. The author’s main focus is the exhibition whose contents, centred around violence and trauma, evoke strong reactions in visitors and provoke deep reflections that instigate systemic and far-reaching change. By exploring examples of exhibitions in museums that have taken up activist issues, performing acts of violence or violation with the aim to affect visitors emotionally, Levin argues that reckoning with difficult topics is crucial to uncover and acknowledge the hard facts of history—a notion that rallies many activists in their engagement with museums.

Museums are about preserving the past, but also about creating new life in the present, and this means challenging the established narratives and breaking away from comfortable views of history. As many of the activists in this issue will argue, denouncing heteronormativity and homophobia as well as making queer history and culture visible should be an ongoing project, especially if museums are to be transformed and transgressed for future generations—both for queer and non-queer audiences.

Part II: Inclusion

In several of the geographic contexts represented in this issue, the transformation of dominant heterosexual institutions has been perceived as an openness to new interpretations, ones that move beyond those traditionally narrated in mainstream museums. Such openness is directly tied to the reconfiguration of museums’ civic role, and of their relation to different audiences. These transformations have certainly been influenced by the civil rights liberation movements of the 1950s and 1960s, as well as the ideas of New Museology that emerged in the 1970s and the 1980s. But they also reflect a response to societal demands for cultural democratisation and inclusivity: ones that are a direct consequence of rights gained by LGBTQI+ communities, as well as by other excluded groups in different nations.

The trend towards a more ‘inclusive’ forum was not, in fact, inherent within museums, nor within the established museum field. Instead, it has much to do with the appropriation of the museum by communities and minority groups; ones that have created and managed their own initiatives since the end of the 20th century, rather than simply allowing traditional institutions to appropriate their representation and concerns. It is also important to account for the influence of a wider audience accessing these public institutions. As demonstrated by Kate Drinane in her case study of the National Gallery of Ireland’s collection, visitors are, in many cases, the ones bringing new information, and distinctively queer perspectives, to collections that have not been ‘queered’ by the institutions themselves. Since it is up to museums and their staff to open up the collections to new interpretations, it becomes crucial to foster more active collaboration with audiences in reviewing the museum’s internal processes and its multi-layered functions, from management to collecting, from documenting to exhibiting. Community-led approaches to well-known collections and to reading specific objects on display have proven to offer, in central institutions in Ireland, an alternative to ‘old’ narratives, and an opportunity to renew visitors’ interest in museums.

However, the simple participation of visitors in a pre-defined exhibition is no longer sufficient for democratising the museum experience. Some of the articles in this section present different methods for changing how museums narrate LGBTQI+ stories within their collections. Drawing on feminist theory, Uliana Zanetti addresses her own professional experiences at the Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna—MAMbo, a contemporary art museum in Italy. She observes the challenges inherent in self-representation from minorities, and describes the museum’s attempt to question gender relations and incorporate feminist approaches to its collections. Zanetti proposes that museums should frame specificity as a tool for more diverse forms of representation, which involves questioning their practices as well as the core values invested in their collections.

Another possible solution, as Sophie Gerber suggests, is to establish new methods of collecting, which involve, for instance, collecting oral testimonies from a variety of sources, encouraging the active engagement of communities in key museum projects and activities, or putting into practice the concept of co-curating collections. In her article, Gerber questions the dominance of cis-male perspectives in science and technology museums in both Vienna and London, and offers a few examples of how objects can be re-interpreted through queer readings and innovative approaches to gender and sexuality. In a similar perspective, Mar Gaitán and Ester Alba investigate how the use of technology as a basis for information dissemination, research and participative debates can assist museums in the creation of alternative ‘itineraries’ in virtual space. What all these alternative methods have in common is the possibility for unlimited collaboration with diverse sectors of society in the creation of museums’ narratives. This has proven not necessarily to abolish the hierarchical relations and the disputes for authority that are structural to these institutions.

In this sense, some of the works presented in this volume suggest that queering involves much more than simply telling different stories. It involves changing how a museum functions, and challenging its main methods for the preservation and transmission of heritage. Inclusion is, in fact, much more difficult to achieve when tackling deeply rooted forms of social exclusion, which arise from the reproduction of certain patterns that mould behaviour and perpetuate the (physical and symbolic) elimination of the Other. This perspective is considered in Florencia Croizet’s critical analysis of the city of Buenos Aires, Argentina, where despite the existence of a strong LGBTQI+ community, social exclusion and violence are still a persistent fact. As a result of historical activism in the country, several exhibitions and museum interventions have denounced the very idea of the museum as an opinion-forming, normative institution that reproduces such social exclusion and violence. What some of the examples offered by Croizet’s piece suggest is that the notion of an ‘inclusive museum’ remains a distant reality—one that, to be fully realised, will require a much more profound disruption of its exclusive and normative foundations.

Part III: Transitions

Museums, as colonial and heteronormative institutions, generally adopt binary categorisations in their documentation, and reproduce stereotypes when communicating their collections. In so doing, even when they display queer references, they work against queerness as an attitude resistant to fixed and normalised procedures or methods. Throughout this issue, the notion of ‘queer’ or ‘queering the museum’ are contested categories used to refer to a variety of transitions within museum practices; they also emerge as nuanced forms of expressing difference. To be queer is also a way to rebel against the museum-dominant forms of categorisation, as a political statement that put into question the very contradiction of a ‘queer museum’.

In her critical approach to the ‘queer’, Lucía Egaña Rojas exposes her own role in a collaborative project involving Latin American professionals in a Barcelona-based museum. The author’s involvement in the readjustment and unlocking of museum practices and policies exposes how power relations—including the upholding of hegemonic narratives—are at the heart of conflicts between sexually dissident activists and museums. Drawing on her personal experiences, Rojas critiques the use of the term ‘queer’ as an Anglophone cultural imposition that cannot be thought outside of colonial legacies: ones forming the basis of continued social violence and cultural imperialism. At the same time, the use of the neologism cuir by Latin American activists can be seen as a means of generating colonial consciousness, as well as an expression of resistance against the use of a foreign concept. Contesting the commodification of sexual difference and gender non-conformity, the author offers ‘cuir’ perspectives of South America, considering how ‘queer’ problems and frameworks originating in the Global North are not necessarily applicable to sexually dissident and transfeminist movements in the peripheries of the world.

Offering a probing interrogation of museum practices in Colombia, Michael Andrés Forero Parra proposes the practice of a ‘museology in motion’: one that is never fixed nor permanent; one that values emotion, but also failure, contingency and constant movement. Based on his experience with Museo Q, established in Colombia in 2012, the author raises a few reflexive questions that are fundamental to all museums (queer or not): How are the grassroots experiences of LGBTQI+ museums concretely changing the general museum field? Are LGBTQI+ artists managing to place their works in public collections? To what extent do these artists and exhibitions impact public policies, to minimise homophobic speech and violence?

Taking a critical stance on mainstream museums in Brazil, Tony W. Boita, Jean T. Baptista, and Camila A. de Moraes Wichers offer an insider’s portrait of the so-called ‘rainbow diaspora’, borne from the traumatic experiences and collective memory of the LGBTQI+ community in the country. The method of aligning social resistance with memorial transmission is one that continues to gain ground in South American Social museology, serving as a protective network for minorities, and a source of resistance against the recent wave of ultraconservative voices that have been threatening LGBTQI+ existences in the cultural and political arenas. In a country like Brazil, marked by severe and compounded inequalities, the exclusion of certain individuals and groups is even more drastic when considering intersectionalities between sexual identity, race, ethnicity and class. Accordingly, extending their analysis and perspectives beyond the ‘queer’, the authors propose a ‘Queer of Colour Critique’, seeking to better understand how museums and museology can impact national public policies in Latin America and the Caribbean.

In a different political context, Rita Grácio, Andreia Coutinho, Laura Falé, and Maribel Sobreira examine a series of talks, Bringing the Margin to the Centre, hosted by the Portugal-based modern art space Berardo Collection Museum. Noting the liberal political context operating in the country—Portugal has passed some of the most advanced legislation on LGBTQI+ rights in Europe—this case study shows how museums in countries with robust democracies are more willing to promote diversity, fostering a space for counter-narratives achieved through what the authors call ‘collective curatorial activism’. By offering queer, postcolonial and feminist readings of artworks and artists in museums, the feminist collective FACA, responsible for organising the event discussed in the essay, questions normativity in museum structures and practices, and exposes the colonial and heteronormative legacies in which museums are rooted.

Drawing on a theoretical framework of political anthropology and philosophy, Aylime Asli Demir offers an analysis of the recent, and increasingly oppressive mutations of Turkish government policy in a time of multiple crises, from financial crashes to terrorist attacks, the rise of right-wing authoritarian populism to the Covid-19 pandemic. In this chaotic, violent and increasingly repressive context, the space for LGBTQI+ activism (and more broadly, public liberties and human rights) is severely controlled and suppressed, primarily in the name of public order and security. In reaction, parts of civil society, including LGBTQI+ artists and activists, are forced to constantly regroup, imagining new creative tactics in order to express their voices, to occupy ‘breathing’ spaces, maintain solidarities and resistance. All these tactics, Demir argues, must be based on a heuristic concept of ‘unpredictability’, applied in practice in order to counter censorship and police repression.

From Greece, Maria Dolores presents a poetic and political reflection on her own experiences as a curator with AMOQA, the Athens Museum of Queer Arts. The article attempts to articulate the author’s involvement in a project whose nature often appears indeterminate, even though the name ‘museum’ is applied—is it a collective performance? An ever-changing roundtable? A hybrid, chimeric, and queer meeting point? A love letter to the deviant multitudes? A character in drag? A biopolitics laboratory? A consciousness-raising feminist workshop? A safe living space for LGBTQI+ people and communities to rest and play? A precarious anchoring in times of gentrification and austerity? An ambivalent attempt to fuse queer radical politics with institutional visibility? A queer approach to life and its materiality? A site of grief, rage and mourning? An archive of feelings? To be continued …

The last piece, taking the form of a conversation— that was edited specifically for this issue—between E-J Scott, Birgit Bosold and Renaud Chantraine, proposes to cross visions and perspectives on the conception of queer curatorial strategies and heritage work for marginalised groups. The discussion traces the evolution of the Schwules Museum, founded in Berlin in 1985, and the recent creation of a Museum of Transology in the UK. How can these community-based and -led initiatives be vehicles for activism and social change? How can they help develop and transmit cultural forms based on queer affirmation, or offer radical narratives in a heteronormative, cis-normative (and even ‘homonormative’) social and museum system? How can collecting and exhibiting methodologies be transformed in order to counter stereotyped, distorted, and—most commonly, erased—representations of lesbians, trans and queer people of colour in public culture? What kind of power(s) does the name ‘museum’ confer? Can a museum be an ‘imposture’? Why does a ‘room of one’s own’, to borrow from the famous words of Virginia Woolf, matter? How to make museum procedures and practices, which are too often opaque and impenetrable, more accessible—so that authority may be effectively shared or reappropriated? All of these questions, and others, animate the conversation.

Closing the issue, Olga Zabalueva presents a comparative review of two recent books in museum theory, both exploring a ‘queer turn’ in museum practices and politics. She notes that the two publications in question, Museums, Sexuality, and Gender Activism, edited by J. G. Adair and A. K. Levin, and Queering the Museum, authored by N. Sullivan and C. Middleton, go far beyond LGBTQI+ issues, contributing to a wider transformation in the contemporary museum field: one centred around the recognition of human rights and the promotion of social justice. Far from being perceived as neutral institutions, museums in the 21st century are obliged to reconsider their social role by opening up to different forms of activism and resistance against normativity.

For many of the authors in this volume, working in an LGBTQI+ museum, visiting a communitydriven exhibition, or even writing about them can represent ways to find their place in the world. For this reason, it was impossible for us, as Editors of this issue, to separate professional input and analytical arguments from personal experience. Museums are places to represent life, but they are also where life happens—and where personal and professional trajectories can be deeply transformed. This issue is a testimony to museums’ power—in changing some of the institution’s central values—to actively restore the lives of those at the margins.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the people who have made this issue possible: the authors and peer-reviewers who dedicated their time and careful (unpaid) work to the articles presented in the volume; and the activists and networks that have inspired us and guided the selection of experiences described and shared here. We also offer special thanks to Aedín Mac Devitt, Courtney Traub and Virginie Lassarre, for believing in our proposal and devoting an incredible amount of work to this issue.

Notes

1 In different attempts to provocatively reinvent the term, feminists have used the term ‘herstory’ pointing out its male-centric construction (see Nestle Citation1990). Variations such as ‘ourstory’ and ‘theirstory’ have been proposed in transgender interpretations of the term.

2 AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) was an international grassroot movement, initiated in New York, that aimed to improve the lives of people with AIDS through direct action, medical research, treatment and advocacy, and also working to change legislation and public policies locally.

3 For more information about the Institute, see: https://www.institutomariellefranco.org/en.

4 In the 1990s, Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner proposed the use of the term heteronormativity suggesting that homosexuality could never acquire the same normative force as the densely institutionalised workings of heterosexuality (see Berlant and Warner Citation2000).

5 Thanks to these networks, we were able to locate and invite several of the authors who have contributed with works to the present issue as well as some peer-reviewers.

6 See the article in which this notion first appeared in such a context, in Lauretis, T. de (Citation1991).

References

- Adotevi, S. 1992 [1971]. ‘Le musée inversion de la vie. (Le musée dans les systèmes éducatifs et culturels contemporains)’ in Vagues: Une anthologie de la Nouvelle Muséologie, Vol. 1. Coordinated by A. Desvallées, M.-O. de Bary and F. Wasserman, Collection Museologia. Savigny-le-Temple: Éditions W-M.N.E.S., pp. 119-123.

- Berlant, L. and Warner, M. 2000. ‘Sex in Public’ in Intimacy. Edited by L. Berlant. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 311–330.

- Boita, T.W. 2018. [unpublished dissertation]. Cartografia etnográfica de memórias desobedientes. MA in Social Anthropology, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, Brazil.

- Bourcier, S. 2018. ‘Politiques queer. Foucault et après ? Théorie et politiques queers entre contre-pratiques discursives et politiques de la performativité’ in Queer Zones. La trilogie. Paris: Éditions Amsterdam, pp. 148-168.

- Brulon Soares, B. 2020a. [Online]. ‘Museu queer e Museologia da bricolagem: o problema da diferença nos regimes museais’, Museologia and Interdisciplinaridade, Vol. 9, No. 17, pp. 81-94. Available at: https://periodicos.unb.br/index.php/museologia/article/view/31594 [Accessed 11 December 2020].

- Brulon Soares, B. 2020b. [Online]. Descolonizando a museologia. Vol. 1. Museus, ação comunitária e descolonização. Paris: ICOM/ICOFOM. Available at: http://icofom.mini.icom.museum/publications-2/the-monographs-of-icofom/ [Accessed 11 December 2020].

- Cameron, D. 1971. ‘The Museum, a Temple or the Forum’, Curator, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 11-24. doi: 10.1111/j.2151-6952.1971.tb00416.x

- Chagas, M. and Gouveia, I. 2014. ‘Museologia social: reflexões e práticas (à guisa de apresentação)’, Cadernos do Ceom, Ano 27, No. 41, pp. 9-22.

- Chantraine, R. 2017. ‘Faire la trace ? La patrimonialisation des minorités sexuelles’, La lettre de l’OCIM, No. 173, pp. 26-33. Available at: http://journals.openedition.org/ocim/1856 [Accessed 11 December 2020]. doi: 10.4000/ocim.1856

- Chantraine, R. 2019. ‘Promesses et paradoxes du « musée queer »‘ in Sexualité, savoirs et pouvoirs. Edited by G. Girard, I. Perrault and N. Sallée. Montreal: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, pp. 131-142.

- Desvallées, A. 1992. ‘Présentation’ in Vagues : Une anthologie de la Nouvelle Muséologie, Vol. 1. Coordinated by A. Desvallées, M.-O. de Bary and F. Wasserman. Collection Museologia, Savigny-le-Temple: Éditions W-M.N.E.S.

- Freeman, E. 2010. Time Binds. Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Hertz, E. 2002. ‘Le matrimoine’ in Le musée cannibal. Edited by M.-O. Gonseth, J. Hainard and R. Kaehr. Neuchâtel: Musée d’ethnologie de Neuchâtel.

- Lauretis, T. de. 1991. ‘Queer Theory: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities’, Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 3-18.

- Levin, A.K. (ed.). 2010. Gender, Sexuality and Museums: A Routledge Reader. London: Routledge.

- Levin, A.K. and Adair, J.G. (eds.). 2020. Museums, Sexuality, and Gender Activism. London: Routledge.

- Mairesse, F. 2005. ‘La Notion de Public’, ICOFOM Study Series, No. 35, pp. 7-25.

- McIntosh, P. 1989. [Online]. ‘White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack’, Peace and Freedom Magazine. Philadelphia: Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, pp. 10-12. Available at: https://nationalseedproject.org/images/documents/Knapsack_plus_Notes-Peggy_McIntosh.pdf [Accessed 11 December 2020].

- Mills, R. 2008. ‘Theorizing the Queer Museum’, Museums and Social Issues, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 41-52. doi: 10.1179/msi.2008.3.1.41

- Mombaça, J. 2017. ‘Rumo a uma redistribuição desobediente de gênero e anticolonial da violência! (2016)’ in Histórias da sexualidade: Antologia. Edited by A. Pedrosa and A. Mesquita. São Paulo: MASP, pp. 301-310.

- Muñoz, J.E. 2009. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: New York University Press.

- Nestle, J. 1990. [Online]. ‘The Will to Remember: The Lesbian Herstory Archives of New York’, Feminist Review, No. 34, pp. 86-94. Available at: www.jstor.org/stable/1395308. [Accessed 14 Dec. 2020]. doi: 10.1057/fr.1990.12

- Nguyen, T. 2018. Queering Australian Museums: Management, Collections, Exhibitions, and Connections. Doctorate in Philosophy. Museum Studies, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, The University of Sydney [unpublished thesis].

- Nunes, S. 2019. Nós museológicos: os discursos queer nas exposições homo (Queer remixed) (2007) e QueerMuseu: cartografias da diferença na arte brasileira (2017). MA Dissertation in Social Anthropology. Goiânia, Universidade Federal de Goiás.

- Petry, M. 2010. ‘Hidden Histories: The Experience of Curating a Male Same-sex Exhibition and the Problems Encountered’ in Gender, Sexuality and Museums: A Routledge Reader. Edited by A.K. Levin. London: Routledge, pp. 151-162.

- Rechena, A. 2012. [Online]. ‘Museologia (d)e Género’ in SIAM. Séries Iberoamericanas de Museología, Vol. 4, pp. 259-269. Edited by M. Asensio, E. Pol, E. Asenjo and Y. Castro. Available at: http://www.uam.es/mikel.asensio [Accessed 9 October 2017].

- Steorn, P. 2012. ‘Curating Queer Heritage: Queer Knowledge and Museum Practice’, Curator: The Museum Journal, Vol. 55, No. 3, pp. 355-365. doi: 10.1111/j.2151-6952.2012.00159.x

- Sandell, R. 2017. Museums, Moralities and Human Rights. London: Routledge.

- Sandell, R. Lennon, R. and Smith, M. (eds.). 2018. [Online]. Prejudice and Pride, LGBTQ Heritage and its Contemporary Implications. Leicester: Research Centre for Museums and Galleries (RCMG), School of Museum Studies, University of Leicester. Available at: https://leicester.figshare.com/articles/Prejudice_and_Pride_LGBTQ_heritage_and_its_contemporary_implications/10207328/1 [Accessed 14 December 2020].

- Sedgwick, E.K. 1990. Epistemology of the Closet. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Sullivan, N. and Middleton, C. 2020. Queering the Museum. London: Routledge.

- Tyburczy, J. 2016. Sex Museums: The Politics and Performance of Display. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- UNESCO. 1973. ‘Resolutions Adopted by the Round Table of Santiago (Chile)’, Museum, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 198-200.

- Varine, H. de. 2005. ‘Decolonising Museology’, ICOM News, No. 3, p. 3.