Abstract

Although the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic and the temporary closure of cultural institutions is not propitious, there are some opportunities for museums. In fact, the crisis may represent an incentive for change. One of the crucial issues in this crisis is the matter of copyright management in museum collections. Copyright is a valuable asset for organisations, on which the possibility of using artworks depends: without the regulated legal status of the work’s authorship, it is not possible to use the work’s copy and share it via electronic media, for example. Today’s crisis is an opportunity to shift perspectives and propose or even enforce new, more strategic solutions instead of mere short-term stopgaps.

The aim of this paper is to answer the following questions: Is implementing copyright-management strategies a temporary need or a necessity? I do not wish to advocate for copyright reform but instead to examine what actions we need to take to formulate and implement copyright-management strategies. This topic will be discussed by drawing on the case study of the Polish History Museum to better explain the phenomenon in question (Stake 1995). The Polish History Museum is creating its first permanent exhibition, and it is the first institution in Poland to develop a copyright-management strategy for its collections. Having analysed interviews as well as secondary sources, I will answer additional questions. What were the stages in the open-policy formulation process? What procedures and organisational changes have been introduced in the museum? What are the current benefits and dangers of implementing copyright-management strategies? I will also discuss legal issues to provide a better understanding of copyright’s potential as a valuable and immaterial resource of museums. Although the analysed case is Polish, it presents examples of implementing copyright-management strategies that may inspire other museums, including those based abroad.

Museum collections copyright is a valuable immaterial resource that, if possessed by a museum, should be subject to management processes (Pluszyńska Citation2011, p. 45). In this paper, I understand copyright management as an informational decision-making process in which the museum, the owner of the rights, tries to use them skilfully to achieve assumed goals. This topic is particularly relevant in the context of the social mission of public museums: museums should store collections and protect them as well as disseminate these collections following the openness principle and the conviction that cultural heritage is a common good. Finding balance in this mission is not easy, and obstacles are often found in copyright issues.

When a museum acquires a work for its collection, it usually holds the ownership rights to it. Meanwhile, the copyright status of a given work translates into the ability to use a copy. Pursuant to the Polish legal system, when a museum acquires ownership of a work’s copy (e.g. a collection), the use of the work (e.g. a photographic reproduction of a sculpture) and the copy (e.g. an exhibition of a sculpture) each requires an appropriate, separate legal basis. Polish legislation does not allow the owner of a work (or copy) to derive additional rights from the ownership right to use the copyrighted work (Łada Citation2019, pp. 39-40). The only exception is fair use, under which the owner of a copy may display it in public if it does not involve any financial benefits. However, the scope of fair use includes only one action—exhibition—which we should understand in terms of traditional exploitation of an artistic work’s copy. Therefore, the scope does not include other fields of exploitation, including online dissemination (Łada Citation2019, p. 82). Consequently, the work’s copyright status determines the extent to which the museum will conduct its activity, not only in the field of exhibiting it but also in terms of its multiplication and dissemination for educational purposes, digitisation, sharing on the Internet, promotion or publishing.

Of course, the issue of copyright management applies only to those collections that meet the characteristics of an artwork. According to the criteria of the protection of works of art adopted in Polish law, the following are excluded from copyright protection: (1) museum collections that have not been created by a human (e.g. naturalia); (2) museum collections that are not subject to protection due to the time of their creation or regulations in force at a given period (e.g. archaeological objects, selected historical photographs); (3) museum collections that do not perform an artistic function (e.g. everyday objects, technological creations); and (4) museum collections whose copyright protection has been excluded by specific regulations (e.g. official documents, materials, signs and symbols) (Łada Citation2019, p. 21). Therefore, all other items included in the inventory of museum collections are also copyrighted works. In this context, the copyright of collections is an essential immaterial resource of the organisation that is subject to management processes on which the current activities of the museum depend. ‘The main issue in the management process is the change of intellectual goods into financial results or other profits such as social relations, openness and cooperation’ (Pluszyńska Citation2020, p. 9). This topic is particularly relevant not only in the view of current technological changes related, among other things, to the digitisation of resources and the sharing of museum collections on the Internet, but also in the face of social changes related to, for example, new forms of participation in culture, or crises such as the Covid-19 pandemic.

Copyright and museums during Covid-19

The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic and the temporary closure of cultural institutions forced a change in the operation of museums and the cultural offer to their audiences. Many institutions had to ‘reinvent themselves’ largely in the context of a forced and, in some cases, accelerated digital transformation. Some studies (including Buchner, Urbańska and Wierzbicka Citation2021) suggest that many cultural organisations moved their operations to the virtual world, mostly without a plan, led by intuition and the ideas and creativity of the employees responsible for individual projects. The dominant perspective was one in which employees’ efforts focused on adapting the existing forms (and formats) to the new situation, not necessarily thinking in terms of new possible formulas for action. Cultural institutions were indeed aware they must quickly respond to the change that lockdown forced on their relationship with their audiences, while simultaneously providing them with an interesting cultural offer. One of the main challenges for employees of cultural institutions in Poland proved to be the need to quickly and efficiently master new technological tools used to present content and form communities of online recipients. Putting content online in accordance with current legal regulations proved to be no less challenging (Ibid).

This difficulty stems from the fact that, in the past, many museums acquired only the ownership of a copy (e.g. donations, sales agreements), without the author’s economic rights. Although museums now tend to acquire the author’s economic rights together with the ownership of new collections or to obtain licences in the necessary scope (Łada, p. 81), many works that have been in the museums’ possession for years remain unregulated in terms of copyright. Thus, the pandemic forced changes in contracts with creators; it also made clear that many institutions lack precise internal rules on acquiring copyright, sharing works and encouraging the public to enjoy them. Moreover, the pandemic showed that undertaking such activities requires additional competencies of staff in the area of copyright and free licences (Buchner, Urbańska and Wierzbicka Citation2021), by which we should understand the need to acquire additional skills in assessing the legal status of collections and the possibility of their further use. We are used to thinking about the pandemic as a crisis, but this unfavourable time also fostered opportunities. In times of stability, implementation of innovative systemic solutions happens rarely, primarily due to the lack of impulse for change (Murray, Caulier-Grice and Mulgan Citation2010, p. 109). The pandemic might represent an opportunity to shift perspective, and to propose or even enforce new solutions. The slowdown of development in the cultural sector may become an opportunity to reflect on the current situation (e.g. European Cultural & Creative Cities in Post-Covid19 Times: Bouncing Forward 2020) and to develop solutions that contribute to making cultural institutions more resilient in the face of inevitable future turbulence and crises.

Despite the challenges cultural institutions have encountered in the past year and a half, the question remains unanswered: will the trend to design the organisational future of institutions pass with the end of the pandemic? For new approaches and practices developed during the pandemic to remain and grow, cultural institutions should prepare strategies to make online resources available that will be consistent across organisations. In turn, this action requires an understanding of what openness is and what benefits it brings so that a museum can implement its mission in a sustainable manner.

This article discusses organisational and managerial solutions, rather than legal ones. The main point of reference will be the activities of Polish cultural institutions, especially museums. Poland is specific in this field, because the country has no track record of reflecting on the roles and functions of public museums today (Folga-Januszewska Citation2008); the Covid-19 pandemic has intensified previously occasional discussions on this topic (Czyżewski et al. Citation2020a). My deliberations will primarily stem from, among other things, numerous reports published over the course of the pandemic, which focus on cultural institutions’ activities during this crisis. I will present the process of implementing copyright-management policy in a museum through a case study. I will use the case study method following N. Siggelkow (Citation2007), who argues that case studies may show the meaning of a particular phenomenon more convincingly than theory. Moreover, case studies may inspire ideas. I chose Muzeum Historii Polskiej (MHP, Polish History Museum) for my case study, because it is the first and only museum in Poland to develop a copyright-management strategy. Although the analysed case is based in Poland, it presents examples that could encourage action at other exhibition-holding institutions worldwide. The topic concerns not so much legal aspects but managerial ones; accordingly, despite the differences in copyright law in various countries, some solutions may be replicated in museums abroad.

Theoretical background

Copyright was created chiefly to secure the livelihoods of creators and incentivise them to continue artistic work (Pantalony Citation2013; Benhamou Citation2016). In the interest of the general public, however, economic copyrights were restricted, for example, temporarily (public domain) or due to other fundamental rights (fair use). The public domain includes works that can be used without restriction of author’s economic right (Sewerynik et al. Citation2019). T. Ganicz (Citation2012) stresses that ‘while the interest of modern creators (…) is obvious and quantifiable into concrete sums of money, the social interest cannot be as easily converted into concrete economic values’. In this article, respecting the adopted legal solutions, I do not address the issue of copyright reform. The starting point is the conviction that copyright is an essential non-material resource of organisations: it constitutes a field of special management challenges, and public cultural institutions—including museums—play a key role in this process. Copyright determines the possibility of sharing collections and, consequently, allows for the pursuit of the public cultural institution’s mission. The mission—much like the definition of a museum—keeps evolving (‘ICOM announces the alternative museum definition that will be subject to a vote’ 2019), with the pandemic intensifying the debate about its meaning (Edson & Visser Citation2020). Currently, museums face a difficult challenge, because the proper understanding of their mission requires them to find a balanced approach between protecting and sharing their collections. These institutions should be strongholds of cultural heritage, protected at all costs against destruction, corruption and misunderstanding (Folga-Januszewska Citation2011, p. 12). Museums cannot separate life from cultural heritage, so they must undertake activities that educate, incentivise or even inspire audiences to creative innovative action (Museums around the world in the face of Covid-19 2021). As Smith (Citation2006) adds, the access to collections is just the beginning.

The significance of cultural heritage lies not in the object itself but in the manner of its use (Smith Citation2006, p. 11). That is why museums should strive to provide as open an access to their collections as possible. Open access means a reduction in the number of legal, economic and technical barriers to using collections while respecting applicable law (Prawne aspekty digitalizacji i udostępniania zbiorów muzealnych przez internet 2014). The strategy of sharing collections in the most open way possible, one that enables their reuse, is not a new idea. It has been postulated for several years by, among others, Europeana (https://www.europe-ana.eu/) and Digital Agenda for Europe (2010). Moreover, according to the NMC Horizon Report: Museum Edition (2016), creating and sharing free cultural resources is now a social responsibility and a determinant of world-class institutions. In this context, the process of heritage resource digitisation has been gaining prominence for many years. Thanks to digitisation, these institutions have seen their audiences radically expand. They are no longer only the people who walk through an art gallery or museum doors but everyone with access to the Internet (Buchner et al. Citation2015). This was particularly evident during the Covid-19 pandemic. Given the above, sharing digitised resources follows the open-access policy as part of the public museums’ social mission. However, the implementation of such solutions should coincide with strategic decision-making for the entire organisation. World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) has long emphasised the importance of copyright in museums by accentuating its role in the management process (Pantalony Citation2013).

If copyright management is ‘a process in which ownership rights generate a value based on the results of intellectual work’ (Pluszyńska, Citation2020, p. 9), then from the perspective of public museums, the essence of management lies in coordinating the acquisition and use of works to fulfil their mission. A strategic approach to copyright management involves developing an internal policy for making collections accessible and adopting appropriate solutions for the implementation of this policy, while considering the mission of the institution, the needs of the staff and the effects the institution wants to achieve with its audience. Deliberate copyright management should also include an evaluation process in the form of an internal implementation assessment, a study on the policy’s impact on the direct environment and the possible supplementation of procedures, and further support in the implementation process. Thus, copyright strategy is not a ready-made product. Instead, both its form and implementation depend on the institution itself, its capabilities and its needs.

There are several reasons to develop internal policies for managing copyright in museum collections. First, consistent principles adopted throughout the organisation reduces the risk of rights violations. Moreover, strategic management of immaterial resources at the museum’s disposal allows it to assess the potential opportunities to fulfil its institutional mission. Consistent decision-making in this area ensures quality across the entire organisation, while the adopted principles guarantee that people agree to follow the same standards. Finally, clearly formulated terms of collection use encourage educational activities and the public’s exploitation of resources (Pantalony Citation2013).

One of the crucial stages in the copyright-management process is the formulation of policy on immaterial resources, followed by the creation of procedures. We should not confuse the word policy with the term procedure. As Diane M. Zorich (Citation2019) notes, policy ‘is a set of statements of principles, values, and intent that outline expectations and provides a basis for consistent decision-making and resource allocation in respect to a specific issue’. Procedures are a specific method of performing tasks. As Zorich notes, many museums create procedures in the absence of policy. A small number of museums have developed an intellectual property policy, but most of them have procedures, such as rights and reproduction checklists, fee and usage schedules, and gallery filming and photography procedures (Ibid). Ideally, procedures would emerge from policy. In most cases, however, it is the other way around: although it is possible to identify examples of policy formulation and implementation of copyright-management processes in museums around the world (Porter Citation2002; Commonwealth of Virginia Citation2000), it is not a widespread phenomenon. Considering the above, we should focus on the implementation of open policy, which means that museums should be places that are open and welcoming to everyone. This ‘opening’ represents a way to disseminate and facilitate access to heritage.

During the ongoing pandemic, representatives of science—but also of culture—emphasise the importance of culture and creativity for society, lobbying for culture to be treated as one of the essential elements of post-pandemic development programmes (Europe Day Manifesto. 2020). Moreover, they foreground the availability of cultural content during the pandemic and the fact that the online sharing of content by cultural institutions free of charge has positively contributed to citizens’ mental health and well-being (Drabczyk et al. Citation2020; Sacco Citation2020). Therefore, it seems logical for public cultural institutions to revisit their content-sharing policies when people so heavily rely on access to culture, also online. With an access policy for resources created with public funds, people can access a much richer variety of Poland’s creative output (Mileszyk Citation2020).

The initial lockdown, which began in Poland in March 2019, instigated cultural institutions to perceive the virtual world as part of the real one and to notice the ‘real people’ navigating online spaces for whom it is worth creating content (Bielaszka et al. Citation2021, p. 18). Assessing the activities of museums before and during the Covid-19 pandemic, online activity during lockdown doubled compared to previous years. However, these generated interactions with the public are much shorter than in the case of a museum visit (Burke et al. Citation2020). Some researchers depreciated the activity of virtual museums, claiming that they mostly replicate the ‘in-situ’ experience, without considering all the possibilities offered by information and communication technologies (Agostino, Arnaboldi and Lampis Citation2020; Rivero et al. Citation2020; Zbuchea, Romanelli and Bira Citation2020). The pandemic makes clear just how big an opportunity digitisation is, which, importantly, does not deny the reality of events that happen in the real world. The authors of the report Pandemia w kulturze (The Pandemic in Culture) note that

it’s difficult to escape the thought that thanks to the Covid-19 pandemic, the cultural sector secured more time and space to reflect on its relationship with the public. And the relationship, if wisely projected, is crucial for the conscious and effective building of an attractive programme offer and long-term dialogue and relations with consumers of culture. (Drabczyk et al. Citation2020, p. 14)

For the fruitful functioning of culture, however, art should create opportunities for legal, mass access to intellectual property without discouraging creators from creative work. Art should enable audiences to access content without individual contact with its author and without negotiation, while not depriving the creator of remuneration (Pluszyńska Citation2020). In fact, the choice between creators’ earnings and audiences’ access is not a zero-sum game. This is proven, for instance, by the crowdfunding models that allow avoiding such conflicts of interest, such as the collaboration of the Goteo platform (https://en.goteo.org/) with local Spanish authorities. It is crucial to introduce a sustainable approach to copyright management in public museums’ collections; this requires managerial action, the introduction of internal strategic solutions in these institutions or perhaps even systemic solutions on a national or European level.

Materials and methods

The starting point of my reflection is the conviction that collection copyright is a valuable immaterial resource for museums, which allows them to fulfil their institutional mission and which must be managed. Below are my main guiding questions:

– Is the implementation of copyright-management strategies necessary?

– What actions must be taken to formulate and implement such a strategy?

To answer this question, I use a case study to illustrate the problem relevant to this article. In the literature there are different definitions of this research strategy. Robert K. Yin defines the case study research method ‘as an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context’ (Yin Citation1984, p. 23). However, according to Robert E. Stake, case study research is ‘the study of the particularity and complexity of a single case, coming to understand its activity within important circumstances’ (Stake Citation1995, p. xi). Moreover, the analysed case may inspire new ideas and pave the way for studying new phenomena that do not have sufficiently developed theoretical backgrounds; a particular case can be employed as an illustration to help understand the proposed theory (Siggelkow Citation2007). Keeping all this in mind, I selected MHP—a state-funded cultural institution founded in 2006—which, after a few years of operation, began to work on implementing the Declaration of MHP Open Policy. This was a deliberate choice. Crucially, MHP is the first public cultural institution in Poland to adopt a formulated open policy (Muzeum Historii Polska 2015). Furthermore, MHP remains an institution ‘in progress’, meaning it is still in the process of creating its first permanent exhibition.

To solve the postulated research problem based on the case study, I formulated the following supplementary questions:

– What were the stages of formulating the open policy?

– What procedures and organisational changes were introduced in the museum?

– What are the current benefits and dangers resulting from the implementation of the copyright-management strategy?

I employed a variety of research methods to gather data, including interviews and text analysis. I conducted two standardised unstructured interviews. The first interviewee was an employee of MHP’s education department, who I interviewed on 11 March 2021 via Microsoft Teams. The interviewee’s responses are marked with the letter ‘M’ in brackets. The second interview was conducted with an employee of Centrum Cyfrowe, an organisation that supported the creation of the Declaration of MHP Open Policy. I conducted the interview on 27 April 2021 via Google Meet. The interviewee’s responses are marked with the letter ‘C’ in brackets. Furthermore, numerous articles available on the websites of MHP, Centrum Cyfrowe and Creative Commons Poland were analysed, as were the materials obtained from the interviewees, including the content of copyright agreements, regulations of grants or competitions, and reports.

Results

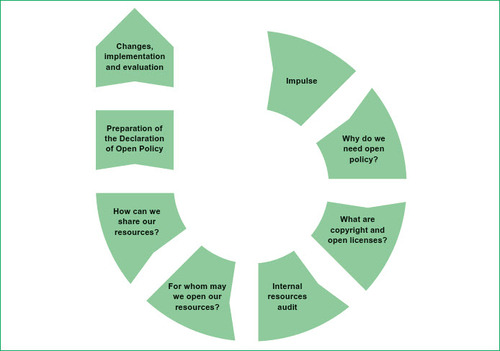

MHP in Warsaw is a museum still under construction and yet to open its first permanent exhibition. The institution’s mission is to present the most important threads in Polish history, of both the State and the nation, with particular emphasis on the subject of freedom, including elements such as parliamentary tradition, civic institutions and movements, such as the struggle for freedom and independence. Since its inception, the museum, acquiring copyrights to its resources, conducted dispersed activities without any cooperation between different departments, let alone unified standards. In 2015, the process of formulating and implementing copyrightmanagement strategies began within the Otwarte Muzeum (Open Museum) project (Polish History Museum. Annual Report 2015); the museum declared its wish to carry out its mission openly, promoting the most open accessibility possible for cultural heritage and scientific resources to utilise their digital potential (‘Mission and statute MHP’, n.d.). To achieve this goal, the process of open-policy formulation began, consisting of several stages ().

The entire process was the initiative of one person who worked for MHP at the time and simultaneously cooperated with organisations promoting open resources. The employees of Centrum Cyfrowe and Creative Commons Poland were also involved in the project.

The process of implementing the open policy began with workshops for employees, which aimed to identify what benefits would arise from implementing the open policy at MHP and what this openness could be used for. The workshop was attended by staff from various departments, especially those that may come into contact with open resources, such as the collections department, the education department and the publishing department. At this initial stage, diverse attitudes towards the idea emerged. There was much apprehension—mainly among senior staff and collections department staff. More enthusiasm was noticeable among young people and education department staff. These fears may have stemmed from lack of knowledge or fear of the unknown. However, in retrospect, the staff noticed tangible benefits from the introduction of the open policy, which I will discuss later on.

Employees also participated in training sessions, whose main objective was to provide detailed knowledge on the current copyright legislation and the rules governing the operation of Creative Commons (CC) open licences. Notably, although the Polish branch of CC was founded in 2005, at the time of creating the Declaration of MHP Open Policy, open licences were not frequently used by cultural institutions, and the staff ’s knowledge about them was rather limited.

An important stage in the implementation of open policy in cultural institutions – also mentioned by the interviewee from Centrum Cyfrowe—is the verification of the owned collection’s legal status. This is necessary to assess whether a collection remains in the public domain and the museum may share it with the public or whether copyright should be acquired from the creators or heirs. Another important element is controlling which works are already digitised and which require digitisation. MHP was in an advantageous and rare situation when working on its open policy. Because the collection was only just being assembled, the audit was not time-consuming or difficult. This collection audit first allowed MHP to estimate the possible future costs associated with acquiring rights to works or their digitisation. Moreover, discovering what museums can share is crucial before moving to the next stage of the open-policy implementation process and investigating for whom resources can be open and how resources can be shared.

Research conducted as part of the Open Museum project was meant to identify the MHP network environment and the audience’s needs. The study was mixed (qualitative and quantitative) and consisted of two modules. The first module measured the approach of MHP employees to the museum’s online activities, and early hypotheses were formulated regarding possible recipients and subject areas for websites. The second module studied the perception of MHP’s online activity from the user perspective, characterised potential recipients, analysed motivations for using MHP services and identified possible barriers in the free use of MHP content (Grabowska et al. Citation2015). The studies clarified possibilities and resources—financial, human, organisational—available to MHP and specified areas whose potential was not utilised to the fullest. At this stage, a set of recommendations for the implementation of possible changes and concrete solutions was formulated. Recommendations development requires not only sufficient knowledge acquired, for example, in research but also an understanding of the studied institution. In the MHP case, open-policy preparation was possible primarily because the preparatory and implementation stages were coordinated by a person well acquainted with the institution and trusted by colleagues, as confirmed by the interviewees. Furthermore, it is crucial that a copyright-management policy in a fully participatory manner. Engaging employees of different ranks and from different departments, and stimulating their willingness to implement the open policy, proved key to the success of the process.

The next step in the process of open-policy implementation was for MHP to publish the written version of the Declaration of MHP Open Policy (Polish History Museum. Annual Report 2015), which served not only as an expression of the open attitude, readiness and willingness to share its resources with its audiences; it was also an important step towards building a relationship with their digital audience (Grabowska et al. Citation2015). A cultural institution informs its audience after it assesses the legal status of a work and its potential further use. Formulating clear rules for sharing and reusing collections leads to the elimination of technical, economic and legal barriers in free access to content, which aligns with the museum’s public mission.

The MHP director confirmed the adoption of open policy through an ordinance-mandated public declaration. The declaration’s content was officially relayed to the supervising institution and published on the museum’s website. In the declaration, MHP committed itself to consistent implementation of its open policy and to clearly formulated rules (‘Open Policy Statement MHP,’ n.d.):

Digital information about publications (metadata) made available in digital form for exhibition activities is transferred to the public domain by use of a Creative Commons 0 declaration (CC0 1.0 Universal. Public Domain Dedication, n.d.).

The digital publications made available by MHP for which copyrights have expired are made available with an accurate definition of their belonging to the public domain with the help of the Public Domain Mark (Public Domain Mark, n.d.). The intention of MHP is to counteract the practice of appropriating the public domain, and making easier the reuse of the material belonging to it.

MHP attempts to publish material created by exclusive use of open formats which enable automatic processing.

Educational, academic and popularising materials subject to copyright are published when possible under open licensing of Creative Commons with preference for free licences.

The declaration became the basis for the introduction of organisational changes

through the identification and declaration of standards pertaining to the materials produced within the framework of its activities and the design of processes so as to ensure that open standards are maintained in the designated areas of activity of MHP. (Polityka otwartości dla MHP 2015)

MHP decided that the open policy would be implemented through exhibition activities, publishing, multi-media production, services and websites development and research, along with educational and promotional projects. The main areas of the implemented open policy were also outlined:

– Produce resources and materials and make them available (ensuring long-term accessibility); in practice, this means that the museum strives to share—under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (also known as CC-BY) free licence— the works of its employees, to which, according to Polish law, the employer has the economic rights.

– Obtain resources and materials and make them available (ensuring long-term accessibility); the museum strives to acquire not only the rights to the copy but also the author’s economic rights to the work. Moreover, it strives to obtain permission to share the work under the CC-BY free licence. A template agreement developed by the museum, containing standardised copyright provisions, helps to implement these measures.

– Engage users and encourage them to use the resources and materials shared under CC-BY free licences.

The open policy was implemented through specific actions. Changes were made to internal legal regulations. A provision about the museum’s openness mission was added to the statutes, and the museum’s terms and conditions were supplemented with a reference to the processes and procedures related to openness described in other documents. Another important step was the museum’s affiliation with groups supporting open policy. MHP joined the Coalition for Open Education—an alliance of non-governmental organisations and institutions that promote the application of open-resource principles in education, science and culture—and the international Open Policy Network, which gathers institutions involved in promoting the openness of cultural and scientific resources (Polish History Museum Citation2015).

The standardisation of contractual provisions for the production, acquisition, transfer, and circulation of copyright of materials and resources was also important to the process. CC legal solutions were implemented as the preferred form of approaching related matters. MHP also propagates these rules in other activities it joins or co-finances, such as competitions or grant programmes. Another important step was the creation of a system for sharing materials, resources and metadata, the latter referring to digital information about exhibits. The introduction of a uniform organisation-wide system that ensures openness required the implementation of certain procedures and staff training.

Sharing resources requires infrastructure. MHP created repositories and used available services that continuously make resources available to the public. The key databases include the BazHum journal database (bibliographic and full-text), the Dzieje.pl history website, the Polishhistory.pl website for speakers of English and educational portals. Moreover, MHP showcases its resources as part of Google Arts & Culture, and during the Covid-19 pandemic, the museum created a dedicated digital resources page muzeum online. MHP also undertook marketing activities to promote open resources to the public and encourage the use of its materials as well as to reinforce the museum’s brand recognition as an open institution. For example, staff members participated in conferences and meetings to share their experiences from accessibility implementation and engaged in works related to OpenGLAM (an initiative to promote open access to digital resources of galleries, libraries, archives and museums, hence the acronym GLAM).

The process of open-policy implementation is a continuous one, requiring the institution to constantly monitor its activities and improve solutions whenever the need arises. The Covid-19 pandemic put MHP’s decisions to the test. When cultural institutions were forced to close, all activity moved online. By creating a dedicated muzeum online page (), MHP did not encounter any legal problems in sharing materials and collections. The main benefit of introducing the open policy was the increased awareness of the legal aspects of the museum’s resources. For several years, the staff has been vigilant about having complete documentation on works’ legal status. Consistent decision-making following the same set of standards ensures quality across the organisation. Furthermore, thanks to the open policy, the employees and especially the audience, are aware of rules concerning collections use, which supports their use and educational application. This is all the more important since the dissemination of knowledge about culture and enabling access to collections is part of the museum’s institutional mission, as confirmed by one of the interviewees:

I believe the implementation of the Declaration of MHP Open Policy was the right choice, because, thanks to that, our collections are widely available and reach many people. This aligns with the mission of the museum, which is a public institution that uses public money. […] The pandemic has shown us that our audiences like using our resources, in particular teachers […] And I believe that the more open the resources are, the more people will use them legally, and that is what all of this is about. (M)

Although open access to online cultural content is not a new topic in the cultural sector, the pandemic has further revealed challenges involving online activities and manners of sharing collections. My research suggests that there is a growing need for MHP to continuously develop its employee competences in terms of copyright and free licences. Because the law is susceptible to change and—more importantly—interpretation, cultural institutions’ employees do not always feel secure in their decisions, so when there appears to be a risk of litigation, they may not take certain actions. The authors of the Kultura w czasach pandemii (Culture During the Pandemic) report arrive at similar conclusions, indicating that

the lack of knowledge among cultural institutions’ employees in the area of copyright and free licences directly reflects on audiences and points to a need for training in the entire cultural sector in how to navigate intellectual property issues on the internet. (Buchner, Urbańska and Wierzbicka Citation2021)

My interviews revealed one more important issue: one related to the current system, rather than simply to a particular institution. One barrier to the implementation of openness is the lack of harmonisation of copyright law, even on a European scale, and the functioning of cultural institutions under different legal regimes. Moreover,

we still lack clear guidelines for lawyers who serve cultural institutions […] We lack a central institution at the local, national or European level to assume responsibility and recommend a course of action. It is crucial to relieve lawyers or directors of cultural institutions of the responsibility, because they will never sign documents that could potentially create litigation risk. […] Clear guidelines recommending greater openness would be helpful, but perhaps also an additional support fund would prove useful if someone were to assert their rights against such an institution. (C)

Activities connected with copyright management implemented by MHP should be assessed positively. Undoubtedly, ‘not many Polish institutions have similar declarations, although many have been opening up their collections for many years. The decision to turn legal principles into something strategic is an advanced-level decision that can serve as a model for other institutions’ (Muzeum Historii Polski i pierwsza taka polityka otwartości 2015).

Discussion

The situation created by Covid-19 poses a direct threat to the existing ways of operating adopted by many organisations, including those in the cultural industry. However, despite all the negative consequences for the cultural sector, the pandemic also stimulated opportunities to introduce innovative systemic solutions that increase the resilience of cultural institutions in the face of inevitable future crises and unrest.

We should reflect on the copyright-management strategy for museum resources. In particular, copyright is an invaluable asset in the possession of institutions, working not so much to facilitate but to enable the provision of cultural goods and thus to fulfil museums’ institutional missions. Therefore, strategic copyright management today is not a temporary need but a long-term necessity. Procedures are not enough; public museums also need considered policies as their principal tool for managing copyright. The elements included in the policy vary depending on the needs of a given institution, but, considering the example of MHP, we can identify crucial elements, including:

– a statement on the choice of the appropriate tool for acquiring rights and sharing collections (in the case of MHP, these are CC licences);

– statements on what is and is not allowed in terms of sharing and reusing resources created within the institution or obtained from elsewhere; and

– statements on how the cultural institution will engage its users and encourage them to use its resources.

The copyright-management process also includes procedures that provide information on who intends to implement the formulated policy, when and how. This article presents only sample procedures, which, by definition, are flexible and easily amendable in response to current needs.

The example of MHP may inspire other exhibition facilities that see the potential in the formulation of copyright-management strategies. Universal advice on how to manage copyright to fulfil an institution’s mission sustainably is impossible, because a strategy should consider an institution’s capabilities and the needs of its internal and external environments. However, strategy development undoubtedly requires a carefully considered, coordinated and planned action based on reliable research of, for example, its audiences. Such an approach is a time-consuming process that requires the involvement of employees from different departments. Moreover, it is ideal if top-down activities are complemented by bottom-up processes, namely initiatives that emerge from within the organisation (Buchner et al. Citation2015; Grabowska Citation2016), because the measure of success is often the human factor: the values and ideals that employees hold (Pluszyńska Citation2020, p. 19).

Finally, let us not forget the obvious: the copyright-management process must be based on the existing legal system. However, it was not my intention to debate whether there is a need to change the current copyright system in Poland or, more broadly, in Europe, although many have called to address this matter, including during the pandemic (Czyżewski et al. Citation2020b). I focused instead on managerial aspects of culture, in particular the practices of public museums. Future studies should including consider postulates for systemic solutions at the national or European level, which could improve and perhaps even accelerate the process of copyright management in museums.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by the Priority Research Area Society of the Future under the programme Excellence Initiative – Research University at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków.

The open access license of the publication was funded by the Priority Research Area Society of the Future under the program ‘Excellence Initiative–Research University’ at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anna Pluszyńska

Anna Pluszyńska has a PhD in management studies from Jagiellonian University, where she currently an Adjunct Professor at the Institute of Culture Management of the Faculty of Management and Social Communication. She is also a manager of culture, coordinator of accessibility and openness, and Vice President of the Research Institute of Cultural Organisations (www.ibok.org.pl). Her research focuses on intellectual property management processes (especially copyright) and the broadly understood openness and accessibility of cultural institutions. Her research interests include cultural-sector marketing and the phenomena of crowdfunding and crowdsourcing.

References

- A Digital Agenda for Europe. 2010. [Online]. EUR-Lex. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1588195013310&uri=CELEX:52010DC0245 [Accessed 7 December 2021].

- Agostino, D., Arnaboldi, M. and Lampis, A. 2020. [Online]. ‘Italian State Museums During the COVID-19 Crisis: From Onsite Closure to Online Openness,’ Museum Management and Curatorship, Vol. 35, No. 4, pp. 362-372. Available at: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2020.1790029 [Accessed 7 December 2021].

- Benhamou, Y. 2016. ‘Copyright and Museums in the Digital Age,’ WIPO Magazine, Vol. 3, Available at: https://www.wipo.int/wipo_magazine/en/2016/03/article_0005.html. [Accessed 7 December 2021].

- Bielaszka, K. et al. 2021. Zmiana kultury a kultura zmiany. Nowe sposoby funkcjonowania instytucji w czasie pandemii. Wrocław: Strefa Kultury.

- Buchner, A. et al. 2015. [Online]. Otwartość w instytucjach kultury. Raport z badań. Warsaw: Centrum Cyfrowe Projekt: Polska. Available at: https://ngoteka.pl/bitstream/handle/item/287/open%20glam%20raport%20net.pdf?sequence=3 [Accessed 16 July 2021].

- Buchner, A., Urbańska, A. and Wierzbicka, M. 2021. [Online]. Kultura w pandemii. Doświadczenie polskich instytucji kultury. Warsaw: Centrum Cyfrowe Projekt: Polska. Available at: https://centrumcyfrowe.pl/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2021/04/Raport_Kultura_w_pandemii.pdf [Accessed 16 July 2021].

- Burke, V., Jørgensen, D. and Jørgensen, F. A. 2020. ‘Museums at Home: Digital Initiatives in Response to COVID-19,’ Norsk museumstidsskrift, Vol. 2, No. 6, pp. 117-123. Available at: https://www.idunn.no/norsk_museumstidsskrift/2020/02/museums_at_home_digital_initiatives_in_response_to_covid-19 [Accessed 7 December 2021].

- CC0 1.0 Universal. Public Domain Dedication. n. d. [Online]. Available at: https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ [Accessed 16 July 2021].

- Commonwealth of Virginia. 2000. Virginia Museum of Natural History Copyright and Patent Policy. Reproduced in the AAM Intellectual Property Resources Pack. American Association of Museums.

- Czyżewski, K. et al. 2020a. [Online]. Raport kultura. Pierwsza do zamknięcia, ostatnia do otwarcia. Kultura w czasie pandemii COVID-19. Warsaw and Kraków: Fundacja GAP and Open Eyes Economy Summit. Available at: https://oees.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Alert-Kultura-4.pdf [Accessed 16 July 2021].

- Czyżewski, K. et al. 2020b. [Online]. Alert Kultura. Warsaw and Kraków: Fundacja GAP and Open Eyes Economy Summit. Available at: https://oees.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Alert-Kultura-4.pdf [Accessed 16 July 2021].

- Drabczyk, M. et al. 2020. [Online]. Pandemia w kulturze. Szansa na pozytywną zmianę? Warsaw: Open Eyes Economy Summit. Available at: https://oees.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/EKSPERTYZA-23.pdf [Accessed: 16 July 2021].

- Edson, M.P. and Visser, J. 2020. [Online]. ‘Digital Transformation in the Time of COVID-19: Sense-making, Scaling Up, and Capacity Building Workshops.’ Available at: https://pro.europeana.eu/post/digital-transformation-in-the-time-of-covid-19-sense-making-workshops-findings-and-outcomes [Accessed 18 May 2020].

- Europeana Foundation, Europa Nostra, European Heritage Alliance. 2020. [Online]. Europe Day Manifesto. Cultural Heritage: A Powerful Catalyst for the Future of Europe. Available at: https://www.europanostra.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20200509_EUROPE-DAY-MANIFESTO.pdf [Accessed 16 July 2021].

- European Commission. 2020. [Online]. European Cultural & Creative Cities in Post-Covid19 times: bouncing forward. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/event/webinar/european-cultural-creative-cities-post-covid19-times-bouncing-forward [Accessed 16 July 2021].

- Folga-Januszewska, D. 2008. Muzea w Polsce 1989–2008. Stan, zachodzące zmiany i kierunki rozwoju muzeów w Europie oraz rekomendacje dla muzeów polskich. Warsaw: Ministerstwo Kultury i Dziedzictwa Narodowego.

- Folga-Januszewska, D. 2011. ‘Ekonomia muzeum – pojęcie szerokie’ in Ekonomia muzeum. Edited by D. Folga-Januszewska and B. Gutowski. Kraków: Universitas, pp. 11-16.

- Ganicz, T. 2012. [Online]. Domena Publiczna. Warsaw: KOED. Available at: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/4c/Broszura_KOED_domena_publiczna.pdf [Accessed 16 July 2021].

- Grabowska, K. et al. 2015. [Online]. Muzeum Otwarte. Centrum Cyfrowe Projekt: Polska and Muzeum Historii Polski, pp. 1–9. Available at: https://ngoteka.pl/bitstream/handle/item/312/CC_MHP.pdf?sequence=3 [Accessed 2 July 2021].

- Grabowska, K. 2016. [Online]. Institute for Open Leadership – pocztówka z Kapsztadu. Warsaw: Centrum Cyfrowe. Available at: https://centrumcyfrowe.pl/czytelnia/pocztowka-z-kapsztadu-institute-for-open-leadership-runda-2/ [Accessed 1 July 2021].

- ICOM. 2019. [Online]. ‘ICOM Announces the Alternative Museum Definition That Will Be Subject to a Vote’, ICOM. Available at: <https://icom.museum/en/news/icom-announces-the-alternative-museum-definition-that-will-be-subject-to-a-vote/> [Accessed 13 July 2021].

- Łada, P. 2019. Prawo autorskie w muzeum. Przewodnik ze wzorami umów. Warsaw: Wolters Kluwer.

- Mileszyk, N. 2020. [Online]. Kultura to nie tylko biznes. ‘Alert kultura’ - czego zabrakło? Centrum Cyfrowe. Available at: https://centrumcyfrowe.pl/czytelnia/kultura-to-nie-tylko-biznes-alert-kultura-czego-zabraklo/ [Accessed 15 July 2021].

- Murray, R., Caulier-Grice, J. and Mulgan, G. 2010. The Open Book of Social Innovation. London: Young Foundation and National Endowment for Science, Technology and Art.

- Creative Commons Polska. 2015. 2015. [Online]. Muzeum Historii Polski i pierwsza taka polityka otwartości. Available at: https://creativecommons.pl/2015/07/muzeum-historii-polski-i-pierwsza-taka-polityka-otwartosci/ [Accessed 1 July 2021].

- NMC. 2016. NMC Horizon Report: 2016 Museum Edition. Available at: https://library.educause.edu/~/media/files/library/2016/1/2016hrmuseumEN.pdf [Accessed 20 November 2021].

- Polish History Museum. n.d. [Online]. ‘Open Policy Statement MHP’, Polish History Museum. Available at: http://muzhp.pl/pl/c/1526/deklaracja-polityki-otwartosci-mhp [Accessed 1 July 2021].

- Pantalony, R.E. 2013. [Online]. Managing Intellectual Property for Museums. Geneva: WIPO. Available at: https://www.wipo.int/publications/en/details.jsp?id=166 [Accessed 11 May 2020].

- Polish History Museum. (n.d.). [Online]. ‘Mission and statute MHP’, Polish History Museum. Available at: https://muzhp.pl/en/c/8/informacje-o-muzeum-historii-polski [Accessed 2 July 2021].

- Pluszyńska, A. 2020. [Online]. ‘Copyright Management by Contemporary Art Exhibition Institutions in Poland: Case Study of the Zachęta National Gallery of Art,’ Sustainability, Vol. 12, No. 4498, pp. 1-24. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/12/11/4498 [Accessed 1 July 2021].

- Pluszyńska, A. 2011. ‘Zarządzanie prawem autorskim - wstęp do zagadnienia,’ Zarządzanie w kulturze, Vol. 12, pp. 43-53.

- Polish History Museum. 2015. [Online]. Polish History Museum. Annual Report 2015. Warsaw: Polish History Museum. Available at: http://muzhp.pl/files/upload/media/mhp_raport_2015_preview.pdf [Accessed 1 July 2021].

- Polish History Museum. 2015. Polityka otwartości dla MHP - dokument wewnętrzny. Warsaw: Muzuem Historii Polski. [Unpublished document].

- Porter, B. 2002. ‘Putting Together a Museum’s IP Policy: Renaissance ROM as a Case Study.’ Paper presented at Creating Museum IP Policy in a Digital World. NINCH Copyright. Available at: http://www.ninch.org/copyright/2002/toronto.report.html#bp.

- NIMOZ. 2014. [Online]. Prawne aspekty digitalizacji i udostępniania zbiorów muzealnych przez internet. Warsaw: National Institute for Museums and Public Collections. Available at: https://nimoz.pl/files/publications/47/Prawne_aspekty_digitalizacji_i_udostepniania_NIMOZ_2014.pdf [Accessed 16 July 2021].

- Creative Commons. n.d. Public Domain Mark. Available at: <https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/deed.en> [Accessed 16 July 2021].

- Rivero, P., et al. 2020. ‘Spanish Archaeological Museums during COVID-19: An Edu-Communicative Analysis of Their Activity on Twitter through the Sustainable Development Goals,’ Sustainability, Vol. 12, No. 19, p. 8,224. Available at: https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/su12198224 [Accessed 7 December 2021].

- Sacco, P.L. 2020 [Online]. ‘Coronavirus (COVID-19) and Cultural and Creative Sectors: Impact, Innovations and Planning for Post-crisis,’ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/culture-webinars.htm [Accessed 17 April 2020].

- Sewerynik A. et al. 2019. Prawo autorskie w instytucjach kultury. Warsaw: C.H.Beck.

- Siggelkow, N. 2007. ‘Persuasion With Case Studies,’ Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 50, No. 1, pp. 20-24. Available at: https://www.scinapse.io/papers/2177997627 [Accessed 7 December 2021]. doi: https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160882

- Smith, L. 2006. The Uses of Heritage. London and New York: Routledge.

- Stake, R.E. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research. London: Sage.

- UNESCO. 2021. [Online]. Museums Around the World in the Face of Covid-19. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373530 [Accessed 15 July 2021].

- Yin, R.K. 1984. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Zbuchea, A., Romanelli, M. and Bira, M. 2020. ‘Museums During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Focus on Romania and Italy,’ in Strategica: Preparing for Tomorrow, Today. Bucharest: Tritonic, pp. 680-705.

- Zorich, D.M. 2019. ‘Developing Intellectual Property Policies: A How-To Guide for Museums.’ Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/heritage-information-network/services/intellectual-property-copyright/guide-developing-intellectual-property-policies.html [Accessed 7 December 2021].