ABSTRACT

In 1967, after the defeat of Poland's Arab allies in the Six-Day War, Poland broke off diplomatic relations with Israel. The government of the Netherlands agreed to represent Israel's interests in Poland from 1967 to 1990. One of the most important duties in the initial period involved the protection of the Israeli ambassador under diplomatic immunity. The activities to be performed for Israel were largely of a consular and administrative nature. The Dutch embassy's most important activity was to issue emigration visas. Upon the departure of Jewish emigrants, the Polish authorities confiscated personal documents. The embassy would take these documents from the departing Polish Jews with the goal of transferring them to Israel. Another issue was that the Dutch embassy was forced to promote Jewish emigration exclusively to Israel. For the Netherlands, the country of emigration did not constitute a criterion in the delineation of representation.

Introduction

When the Soviet Union broke off diplomatic relations with Israel on June 10, 1967, after the defeat of their Arab allies Egypt and Syria in the Six-Day War, Poland was expected to follow soon. The Israeli ambassador in Warsaw, Dov Sattath, approached his Dutch counterpart, Fredrik Calkoen, about this matter. He expressed the hope that, in such a case, the Netherlands would act as a protective power, as it had done in Moscow in 1953.Footnote1 The same day, Marian Naszkowski, the Polish Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, sent a telegram to Józef Puta, the Polish ambassador in Israel, stating that Poland would be breaking off its relations with Israel: “In all probability, we will be suspending ties with Israel effective today, and we are notifying the ambassador in Warsaw. Be prepared to depart from Tel Aviv with the staff within 48 h.”Footnote2 That evening, Jerzy Michałowski, the Polish Secretary-General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, notified Puta that the decision to severe relations had become uncertain in connection with the ceasefire that had been announced between Israel and the Arab states.Footnote3

One day after the ceasefire of June 11, 1967, Poland nevertheless broke off its diplomatic relations with Israel. All of the countries in the Soviet bloc followed suit, minus Romania. The countries decided to take this step in response to the Soviet suspension of diplomatic relations with Israel. Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev labelled this as a spontaneous act by the communist leaders that had not been planned. According to Brezhnev, the Soviet Union and the other East-European countries felt a need to react to the situation that had emerged following the defeat of their Arab allies. They were therefore prepared to take diplomatic action against the occupation of Palestinian territories by the Israeli army.Footnote4 Romania had a different view. The Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs, Joseph Luns, received a visit from George Elian, the Romanian ambassador in The Hague. Elian said that Romania had experienced pressure from the Soviet Union and the other East-European countries during a conference in Moscow on 9 June. In this conference, a joint declaration had been signed, Israel had been identified as an aggressor and the gathered Warsaw Pact nations decided to break off relations. Romania refused. The Romanian government’s standpoint, which was based on their politics of independence, was that its refusal was founded on Bucharest’s objective findings concerning what had occurred in the Middle East. Romania disagreed with the assessment that Israel was the sole aggressor.Footnote5

On June 12, 1967, Adam Rapacki, the Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs, sent a telegram to Puta stating that relations with Israel would be broken off that day. The decision was also announced in a letter from the Polish government to the Israeli ambassador, Sattath. Included in the letter was a clear statement that Poland would restore relations if Israel were to withdraw from the occupied territories.Footnote6 Poland’s Dutch ambassador Calkoen informed Minister Luns that Communist Party discipline had prevailed: in the afternoon of June 12, the Polish government’s decision to break off diplomatic relations with Israel was communicated to the Israeli ambassador in The Hague.Footnote7 On June 15, 1967, in The Hague, the Israeli ambassador requested the Dutch government to grant official consent to representation by the Netherlands. The Dutch government supported Israel. Luns had expressed his agreement with this request and had informed the ambassador accordingly.Footnote8 The Polish government agreed.Footnote9 From June 12, 1967, the Dutch embassy in Warsaw represented the interests of Israel. The Dutch embassy in Moscow was also acting as a protective power for Israel, which likely wanted to be represented in the largest countries of Eastern Europe by one of its most loyal allies. In Hungary, Switzerland represented Israel, Belgium in Yugoslavia, and Sweden in Czechoslovakia. In Bulgaria no Israeli representation existed and Albania and the GDR had no diplomatic relations with Israel. How that selection was made by Israel is unknown.

Departure of the Israeli Ambassador

On June 18, 1967, the Israeli ambassador Sattath travelled back to Tel Aviv as persona non grata. Calkoen escorted his colleague to the airport in Warsaw, Okęcie (the current Chopin airport). The Israeli ambassador departed with his family and nearly all members of the Embassy staff and their families. Two staff members stayed behind and worked in the Dutch embassy.

Calkoen was accompanied by his secretary, Floor Kist, who was aware that hundreds of demonstrators had gathered at the airport with the goal of deriding the departing Sattath. Calkoen accompanied the Israelis to the awaiting Air France aircraft, walking at the head of the group. The protesters blocked the path with banners, but the Dutch ambassador was a charismatic man who would not be intimidated. He kept walking. At the last moment, the demonstrators moved aside. It was clear that the protest had been staged. Under normal circumstances, it was obviously forbidden to enter the airport. Moreover, the banners had been prepared with identical anti-Israeli texts.Footnote10

With regard to the demonstration at the airport, where Calkoen had escorted the Israeli ambassador and his wife to the airplane, he recounted:

We proceeded through the jeering demonstrators, who were making menacing gestures with sticks or their fists and, according to Sattath, hurling the vilest and most threatening curses. Virtually all Israeli officials are of Polish birth. I had to go to great lengths to prevent the Sattaths from running. On the way, I persuaded him that he should not visibly jeopardize his dignity under the gaze of the television cameras. I assured him that the mob would not be permitted to abuse our small group before the eyes of ten ambassadors along the sidelines.

Radio Free Europe, the Israeli press and the Zionist-inspired Western press have published a fake report claiming that Israeli diplomats – before leaving Warsaw – had been harassed by a large crowd of Warsaw residents, who had supposedly assembled at the airport that day in order to demonstrate their hostile feelings with regard to Israel.Footnote11

Calkoen complained to the acting chef protocole, Edward Pietkiewicz, who expressed hope that the relations with the Netherlands had not deteriorated. “That is the last thing I would want,” responded Calkoen. “Representing the interests of Israel is a matter of honour, but it is important not to damage the Dutch interests in Poland.”Footnote12 Andrzej Kępiński, of the Diplomatic Protocol department, went to the Warsaw airport with the goal of assisting in the departure of the Israeli Embassy staff. He provided the following report, to Deputy Minister Naszkowski:

At 17:50, the officer from WOP [Wojska Ochrony Pogranicza, the military unit responsible for border control, AR] escorted us to the customs arrival hall, which had been reserved for this purpose, where the ambassador from the Netherlands, Mr. Calkoen, and his wife were already present, as were those who would be leaving Warsaw: the Israeli ambassador, Mr. Sattath, along with his spouse and daughter, as well as the staff members from the aforementioned Embassy and their families. The baggage formalities had been arranged by the third secretary of the Dutch Embassy, Mr. Kist, and the attaché from the Dutch Embassy, Van Son. After their passports had been inspected and their baggage had been checked in, they were all directed towards the terrace in front of the international departure hall, which was separated from the platform by a fence.

After leaving the waiting room, we observed lines of people on both sides of the platform, from the international departure hall to the aircraft, with banners bearing texts condemning the aggression of Israel. Due to a flight delay, the passengers did not board until 18:45. Ambassador Calkoen escorted Mr. Sattath and other members of the Israeli Embassy to the aircraft, along with their families. As the group walked through these lines, the crowd was shouting expressions including, “Down with the Israeli fascists!” This was followed by whistling. In response, the heads and members of the diplomatic delegations who had come to bid farewell made an ostentatious display of their solidarity with the members of the Israeli Embassy, who were walking towards the aircraft. The aircraft departed around 19:00.Footnote13

Calkoen notified the Diplomatic Protocol of the unpleasant aspects of the circumstances surrounding the departure of Sattath.Footnote14 Pietkiewicz responded to Naszkowski:

Mr. Calkoen has stated that he was strongly affected and strained by yesterday’s demonstration at the airport, which was contrary to the prevailing customs concerning the treatment of diplomats throughout the world. Nevertheless, he does not want this matter to damage either the relations between the Netherlands and Poland or his own relations with the Polish government.Footnote15

The Diplomatic Protocol received an aide-mémoire (memorandum), which had been submitted by Calkoen on June 19, 1967, concerning the installation of an information sign on the building of the former Israeli Embassy in Warsaw, located on Krzywicki Street. The plan called for replacing the emblem of Israel with a Dutch sign. The Finnish flag was already flying above the former Embassy of the Polish People’s Republic in Tel Aviv after the severance of diplomatic relations. Finland represented Poland. As he explained, Switzerland, which had already represented a large number of countries in the past, was also accustomed to placing the Swiss flag atop the chancellery in question.Footnote18

The Position of the Jews in Poland

Calkoen quoted from an interview with Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs Rapacki in Trybuna Ludu (People’s Tribune), the Communist Party newspaper, regarding to the conflict in the Middle East. Rapacki had said that Poland was of the opinion that Israel’s unconditional withdrawal from the occupied Palestinian territories would be the first step towards peace in the region.Footnote19 One day later, Calkoen wrote that Poland had tried to justify the breaking off of diplomatic relations with Israel through a wide range of demonstrations, as well as through the media: “the Party’s agitprops thus [pulled out] all the stops in the press, radio and television in order to justify this largely unpopular step in the public opinion.”Footnote20

Calkoen notified Luns that a number of generals and officers of the Polish army had been fired or demoted due to their praise of the Israeli soldiers following their rapid victory over the Arab armies.Footnote21 After the Six-Day War, high Polish military officials had expressed doubts concerning the effectiveness of Soviet weaponry, particularly their aircraft: the Russian MiGs were no match for the French Mirages. Moreover, they were critical of Russian military thinking: the tactic of the more static and defensive concentration of fighting power had failed against Israel’s quick and dynamic attacks.Footnote22

The Polish postal service refused to deliver letters from Israel bearing postage stamps depicting the Israeli victory in the Six-Day War.Footnote23

On July 12, 1967, Poland increased the fee for the document that allowed Jews to emigrate to Israel from 300 to 5000 zloty. “It goes without saying that the prevailing fee is virtually prohibitive for many, and particularly for the heads of large families,” said Calkoen.Footnote24 Luns made an official visit to Poland from August 21 through August 24, 1967. This was the very first time that a Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs had visited the Polish People’s Republic. Luns engaged in extensive consultation with his counterpart, Rapacki, who explained the Polish position concerning the situation in the Middle East after the Six-Day War: political responsibility did not rest solely with Israel, but also with the United States, particularly as a result of American power politics. Rapacki claimed, “We were much closer to a world war than it appeared.” Luns defended Israel, as the Arab countries had continually threatened to wipe Israel off the map. According to Luns, it was certain that war would have broken out if Israel had remained passive. During his visit, Poland and the Netherlands concluded several agreements, including with regard to cultural cooperation. They did not discuss the representation for Israel.Footnote25 After his visit to Poland, Luns received a visit from the Israeli ambassador in The Hague, Daniël Lewin. Luns informed him about the discussions that he had conducted in Poland with regard to the crisis in the Middle East. Lewin was interested to hear Luns tell him that, despite Poland’s anti-Israeli politics and the flourishing of official antisemitism, the Polish government emphasized Jews’ brutally murder by the Germans in Poland during the Second World War. They had also taken the Dutch delegation to see the monument to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.Footnote26

The expelling of Jews had begun. Following the infamous speech of the Polish Party leader Władysław Gomułka on March 19, 1968, in which he divided the Polish Jews into loyal and disloyal citizens, the Dutch Embassy received many questions from foreign journalists concerning the emigration of Jews from Poland to Israel. Calkoen prohibited the members of the Embassy staff to provide any details in this regard, while he personally told the journalists that the number of permits for travel to Israel was no lower after June 1967 than it had been before that date. When foreign journalists asked whether the Polish government was impeding people wishing to leave for Israel, Calkoen responded that he was not aware of such cases, as the Polish government – as it had prior to June 1967 – had continued to grant Jews permission to leave for Israel with the intention of establishing residence there. Calkoen ascertained that he had indeed correctly understood the part of the speech in which Gomułka had expressed the Polish government’s willingness to issue a document to Jews who regarded Israel as their homeland and who wished to leave.Footnote27

Calkoen kept Minister Luns abreast of the position of Jews in Poland. In response to Gomułka’s address, Calkoen explained that Poland remained willing to issue documents to Jews who regarded Israel as their homeland. Adam Willmann, head of Department IV (Western Europe) of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, confirmed that this was the view of the Polish government.Footnote28 Calkoen sent yet another message to Luns. “Through Gomułka and others, the Party has declared that it is against antisemitism, while hypocritically presenting itself as anti-Zionist, with Gomułka continuing to allow emigration to proceed, but not enforcing emigration.”Footnote29

In May 1968, Willmann summoned Calkoen. He explained the Polish government’s standpoint that, although Zionism was regarded as a danger to the state, the United Polish Workers’ Party and the Polish government were strongly against antisemitism, and they continually rejected it in official statements.

To me, as the guardian of the interests of Israel, the fact that Jews in Poland are not persecuted would have been evident in the fact that the Polish authorities do not impose any obstacles that would impede Polish Jews wishing to emigrate to Israel.

Diplomatic Representation for Israel in Warsaw

Ambassador Calkoen reported to Minister Luns in detail concerning the general duties and activities carried out by the staff of the Dutch Embassy in Poland for the purposes of representation. One specific duty of the Netherlands as a protective power involved the safe departure of the Israeli diplomats. In this regard, Calkoen looked back and wrote about protection under diplomatic immunity until the departure of the Israeli ambassador, along with his staff and family members. He received the requested confirmation from the side of Poland. Poland referred to this as “diplomatic immunity as a person.” Other specific duties had to do with the protection of Israeli nationals and buildings, in accordance with Articles 45 and 46 of the Vienna Convention of 1961 concerning Diplomatic Relations. When the Polish government sought to take over the buildings of the Israeli Embassy as quickly as possible in 1968, Calkoen referred to Article 45.Footnote31 The Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Jerusalem also referred to this article.

After terminating diplomatic relations with Israel, the Polish authorities agreed that the Dutch Embassy would monitor the Israeli nationals, the property, and the archives of the Israeli embassy. For this reason, immunity based on the article remained in effect. Poland was required to respect this immunity.Footnote32 The principal activities included issuing emigration visas, which was done under conditions of strict confidentiality. Luns considered it redundant to report the actual departure of the emigrants to the Jewish Agency in Vienna. In the margins, he wrote, “Why? Indeed, this information is already forwarded to the Israeli Embassy here in The Hague for the authorities in Jerusalem through the intervention of this Ministry.” Although the additional activities increased the workload at the Embassy, the ambassador fulfilled his mission with pleasure: “It provides a sense of satisfaction to be able to help Polish Jews in often very difficult circumstances. This representation is an honour, to which we are all glad to contribute our efforts.”Footnote33

Upon the departure of Jewish emigrants, the Polish authorities regularly confiscated personal documents, including membership cards, awards, manuscripts, letters and degree certificates. This made it difficult to build a future elsewhere. The Dutch Embassy in Warsaw protested against this practice, démarches were performed. If desired, the Embassy would receive these documents for the purpose of transferring them to the Dutch Embassy in Jerusalem, through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in The Hague. In November 1968, the Embassy received documents from Marek Brafman, a physicist at the Institute for Nuclear Research in Warsaw. Ambassador Calkoen asked Luns if it would be a good idea to copy and translate these notes, with the goal of obtaining insight into the scientific state of affairs concerning atomic research in Poland. The Ministry in The Hague had written the word “No” in the margin of this confidential letter. At the bottom of the text it was written that the documents had been transferred to an Israeli diplomat and that this individual had not been informed of the manner in which the documents had arrived in The Hague.Footnote34

One month later, the Ministry decreed that the ambassador would no longer be allowed to accept personal documents from Jews, “given the undeniable risk that your post will be compromised.” In this regard, the use of the diplomatic courier would also no longer be allowed, except in extenuating circumstances that served a Dutch interest and for which permission had been granted after advance consultation with Luns.Footnote35 Calkoen opposed Luns, arguing that there was no risk of compromise. According to Calkoen, it was the Polish authorities who had an interest in not creating a stir with regard to the issue of confiscating personal documents, as they were not capable of preventing the lower authorities from “irritating and illegal antisemitic bullying,” while the transfer of these documents was of great importance to Jews. “Duty of honour and compassion for these lamentable people” made it necessary for the ambassador to request the Minister to reconsider allowing transfer by diplomatic courier. The alternative was to use other embassies that had previously offered assistance. However, Calkoen was opposed to this, as the Jews regarded the Netherlands as their protector.Footnote36

Notwithstanding Poland’s official point of view that Jews who were loyal could remain, the majority decided to emigrate. The Polish government thought Jews would leave for Israel, not for other countries. This placed Poland in a difficult position. The Arab countries were opposed to further Jewish immigration to Israel, as this would increase the population of Israel. The acting Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs, Józef Winiewicz, sighed to Calkoen: “If we forbid emigration, the Western countries will start to scream; if we allow emigration, the Arabs will protest.”Footnote37 Many Polish Jews were not Zionist and did not wish to emigrate to Israel. The Dutch Embassy should refrain from promoting Jewish emigration to alternative countries, Calkoen said. This created a problem that Calkoen acknowledged: “I regard it as my duty to promote emigration to Israel. In some cases, however, the preference is for other countries.”Footnote38 The Netherlands had no opinion on the question about the destination of the emigrants.Footnote39 The Netherlands de facto represented Polish Jewish interests and not Israeli interests. In other words, Dutch diplomats understood the anti-Zionist campaign as a camouflage for antisemitism.

As Embassy secretary from March 1968 through February 1970, Ted de Ryck van der Gracht was directly charged with issuing exit visas. He took quasi the position of the Israeli consul. The Dutch did not receive specific instructions from Israel. The Israeli consular handbook was the only guideline the Dutch had. Two members of the administrative staff, Irena Malinowska and Julian Gerszt, had come directly from the Israeli Embassy in Warsaw to the Dutch Embassy, where they started to work in the Israel department.Footnote40 As Polish citizens, they were potentially vulnerable, and it was necessary for them to be able to state that the Dutch had taken all decisions. After receiving permission from Israel, the Dutch Embassy was authorized to issue a promise of visa letter (provisionally visa) first, followed by an emigration visa for Israel, only after the person in question received a “travel document” (in Polish, dokument podróży) from the Polish government. This manner of issuing an Israeli visa was based on the 1950 Law of Return, which gave Jews throughout the world the right to settle in Israel and to receive Israeli citizenship, as reflected in the consular handbook of Israel. In case of doubt about one’s Jewish identity, this was confirmed by the municipality (the Jewish kehilla) from which the person in question came.Footnote41 Israel saw no reason to check the applications afterwards. The time elapsing between the visa request and the departure depended upon when the document was issued by the Polish authorities. They did not issue emigration passports to Jews, but a “travel document,” literally stating that the holder was no longer a citizen of Poland and was therefore in fact stateless. The Jewish emigrants travelled by train from the Gdański station in Warsaw to Vienna. They were required to pay substantial amounts for the reimbursement of the costs of their studies, the renovation of their apartments, and other charges imposed upon emigration. In the words of Alexander Heldring, who was responsible for issuing Israeli visas to Polish Jews at the Dutch Embassy in Warsaw in the period 1970–1971:

[U]pon leaving Poland, Jewish emigrants often [experienced] harassment from the Polish border guards, as their university degree certificates and other important documents were confiscated (“these belong to the Polish state”). Our Embassy in Warsaw helped the emigrants by allowing them to turn in their documents here – hopefully unseen by the Polish secret service. Every few months, when we were able to enjoy a short stay in the Netherlands, we would take these documents in our luggage protected by diplomatic immunity. Through the Israeli Embassy in The Hague, the documents would find their way to their respective owners, whether in Israel or elsewhere.Footnote42

Jewish emigrants leaving Poland were subject to the same rules that applied to other Polish citizens: with the exception of a small amount of money, they were not allowed to take any valuables, nor any documents, manuscripts, letters or certificates. So it was not a form of bullying devised by individual border guards, but a generally applicable rule. Because this rule is obviously very problematic when one is forced to build a new future elsewhere. Ambassador Calkoen decided in early 1968 (without consulting the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in The Hague) that he and his staff members with diplomatic status would take such personal documents from emigrants with them in postal sacks – sealed as diplomatic courier documents for reasons of security – in their cars on their semi-annual leave to the Netherlands, in order to deliver them to the Israeli Embassy in The Hague. In the winter of 1969–1970, these transports came to an abrupt end, when the Ministry in The Hague heard about it and instructed the Embassy in Warsaw in writing to immediately cease this activity. The argument was that inappropriate use was being made of the diplomatic courier, that this was in conflict with international agreements and that there was a risk that, if it were to became known, it could compromise the position of Holland as the représentant of Israel. These instructions were of course observed, and ambassador Calkoen found a friendly Western Embassy that was willing to take over the transports, which had since become smaller, due to the sharp decline in the number of emigrants in the early 1970s.Footnote43

Dutch Response to the Antisemitic Campaign in Poland

In June 1968, Minister Luns received a visit from the Polish ambassador Stanisław Albrecht in The Hague. Albrecht provided a number of examples of Dutch-Polish (cultural) events that had been cancelled in the Netherlands. Luns took note of the démarche, stating that antisemitism in Poland had led to unrest amongst the Dutch population. The ambassador responded by pointing out that there was no antisemitism and that Poland’s position on the Middle East was a political issue, which had nothing to do with the fate of Jews in Poland.Footnote44

On March 14, 1969, Dutch television broadcast an item in its current-events programme Achter het nieuws (Behind the news) that was devoted entirely to antisemitism in Poland. The Dutch reporter Hans Jacobs interviewed Simon Wiesenthal, head of the Jewish Documentation Centre in Vienna. Wiesenthal recounted that a group of Jewish writers from New York had asked him for advice. They were planning to institute legal action against Polish communists who had expressed themselves in an antisemitic manner. He was preparing documentation on the situation of Jews in Poland. According to Wiesenthal, the antisemitic campaign could be repeated in other East-European countries. He was of the opinion that his historical research could have a clarifying effect.Footnote45 Several days later, Achter het nieuws broadcast another report on Wiesenthal in response to his publication on antisemitism in Poland. According to Wiesenthal, antisemitism was based in part on resentments of a number of pre-war antisemites who controlled the Polish press to some extent. At the same time, antisemitism was a tool to be used in the power struggle within the Communist Party.Footnote46 In a press conference, Wiesenthal explained that the ideological leaders of the antisemitism in Poland could be found in the Polish Communist Party. He provided the international press with a list of names of Polish communists, who had played an important role in the antisemitic campaign. The fifty names included that of the former Minister of Internal Affairs, Mieczysław Moczar, who was the secretary of the Central Committee and a candidate for the Politburo, as well as that of Bolesław Piasecki, the leader of the Catholic Pax movement.Footnote47

On March 19, 1969, Johan Schlingemann, a member of the House of Representatives from the Dutch political organization People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), asked questions concerning the position of the Jews in Poland. Two weeks later, on April 3, the Polish ambassador Albrecht paid a visit to the secretary-general of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Emile Schiff, to draw attention to the campaign that was supposedly being waged in the Dutch media against the Polish government, which was being accused of antisemitism. The ambassador also referred to the parliamentary questions posed by Schlingemann. He asked whether the Dutch government would be able to stop the “anti-Polish campaign.” According to Albrecht, responding to Schlingemann’s questions offered the government the opportunity to make known the truth about Poland.Footnote48 On April 10, Luns responded to Schlingemann that the situation of Jews could be described as “not enviable.” He continued, “On various occasions, the government has already expressed its concern – and that of Dutch public opinion as a whole – to the Polish authorities with regard to the position of the Jewish section of the population in Poland.”Footnote49 Luns had his response to the parliamentary questions sent to Calkoen by telex.Footnote50 On behalf of the Polish government, Albrecht filed objections to Luns’ answers to the State Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Hans de Koster. Albrecht repeated that the media in the Netherlands had been spreading false reports concerning the treatment of Jews in Poland. De Koster referred to the independent position of the Dutch media.

He agreed that the Dutch ambassador had not reported in Warsaw in a way that indicated Jewish persecution, but that was intended not to jeopardize the emigration of Jews from Poland.Footnote51

Denmark

A large group of Polish Jews chose Denmark as a refuge, as it had saved nearly all of its Jews during World War II. The country welcomed them. Attempts to persuade them to go to Israel failed. Not surprisingly, many of them were communists who were not Zionist. The Dutch newspapers and television channels paid a lot of attention to Jewish emigration from Poland. In Copenhagen in 1969, the Dutch journalist Jaap van Meekren interviewed several Jewish refugees for the current-events feature Televizier, in connection with the antisemitic campaign in Poland:

Yes, here in the port of Copenhagen, as well as in Sweden, one can see the sad image of men, women and children driven from their country, uprooted and destitute, not because of war or natural disasters, but only because they are Jews – Polish Jews whose lives were made impossible in their own country. Since August of this year, approximately 1500 have come to Copenhagen alone, and the stream is continuing at a rate of 100 per week. Three hundred have been given temporary accommodations in an old hotel ship. They are now waiting here in the narrow cabins, in the salons and on the decks. Young and old, sick and healthy, former party officials and labourers, as the anti-Jewish offensive of the Polish regime has been directed towards them all.

The fate of those refugees who have experienced it before is a double tragedy. Before the war, Poland had 3.5 million Jews. Of the 50/60 thousand who survived Auschwitz and Treblinka, three-quarters would eventually emigrate, primarily to Israel. It would be safe to assume that the greatest majority of those who stayed behind were anything but Zionists. Many were communists who thought that they would be able to forget their Jewish origins in a desperate attempt at assimilation. That is why they do not wish to go to Israel now either. They would like to remain in Denmark – a country that is open to anyone requesting asylum for humanitarian reasons. Even the ones who learn to speak Danish in twenty lessons remain “froh”: a refugee who has more memories than future. The communist regime in Poland has since added several thousand more to the vast legion of displaced persons who, at best, could be described by the story of the German refugee to the United States of America who, when asked, would answer, “Yes, yes, I’m happy, I’m very happy. Aber glücklich, glücklich bin ich nicht.”Footnote52

Hagenaar’s 1971 Annual Report on Poland stated that nearly the same number of Jews had left that year as had left in 1970. In the past, however, the majority had initially departed for Vienna. By 1971, the primary destination had shifted to Copenhagen, which – like Vienna – served as a transfer station for further emigration.Footnote54

Leopold Trepper

The term “refusenik” (otkaznik) was a term used for Soviet Jews who were denied permission to emigrate and faced social isolation until they managed to emigrate. In Poland there was no “refusenik” issue. In fact, the rarity of people being denied exit visas is what stands out on the backdrop of the vast issue of the Soviet Union refusing visas to Jews desiring to emigrate. A letter to the Dutch Foreign Minister Norbert Schmelzer contained a reference to one “difficult case”: Leopold Trepper. No “travel document” had been issued to him. During World War II, Trepper had headed a communist espionage group known as the “The Red Orchestra.” As a result, he was aware of state secrets in the Soviet Union, which opposed his emigration for this reason. In February 1972, the government’s spokesperson, Włodzimierz Janiurek, stated that Trepper would not be allowed to leave the country because of state security.Footnote55 On March 13, 1972, the Executive Board of the Catholic People’s Party (KVP) issued a press statement concerning Trepper, expressing the opinion that the Polish government should take the humanitarian step of granting Trepper an exit visa for Israel. At the same time, an appeal was made to the Dutch government to exercise its influence on the Polish government.Footnote56 Trepper’s case differed from other Polish Jews desiring to emigrate, because the Soviet Union was involved.

A week later, Minister Schmelzer had assigned the Dutch ambassador Joost van Ebbenhorst Tengbergen to bring the matter before the Polish authorities.Footnote57 Schmelzer replied to the KVP that the Dutch Embassy in Warsaw had presented the issue of authorizing Trepper’s departure to Poland. In response, the Polish authorities noted that there would be no chance that the request would be granted.Footnote58 On March 24, 1972, at Schmelzer’s instruction, Van Ebbenhorst Tengbergen also brought the matter to the attention of Stefan Staniszewski, the head of the Department of Western Europe of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Once again, the official Polish standpoint stated that Trepper was not allowed to leave Poland for reasons of national interest. According to Staniszewski, this prohibition was a sovereign Polish decision. It thus seemed to him that the Dutch démarche was difficult to reconcile with its representation for Israel.Footnote59 In the Netherlands, the discussion was resumed by the KVP member of the House of Representatives, Cor Kleisterlee, who had welcomed Trepper’s spouse who was allowed to emigrate to Copenhagen.Footnote60 On February 22, 1973, the matter culminated in the presentation of a petition to the Polish Embassy. The petition had been signed by 115 of the members of the House of Representatives who had been present, including all party leaders, except for the leader of the Communist Party of the Netherlands (CPN), who refused to sign. The signatories requested the Dutch government to do everything in their power to promote exit options for Trepper.Footnote61 Minister Schmelzer wrote to Kleisterlee that the Polish reaction was once again dismissive.Footnote62

The Dutch press also devoted considerable attention to the Trepper case. It was reported that several members of the House of Representatives, including Hans van Mierlo of the Dutch political party Democrats of 1966 (D’66), had presented the petition to the first secretary of the Polish Embassy, Jerzy Krawczyk, including the request to grant an exit visa to Trepper. “According to the initiator, Van Mierlo, the petition had come as an unpleasant surprise to the Embassy staff, who would have to consider whether the request should be forwarded to Poland.”Footnote63 Trepper was interviewed by the Dutch journalist Simon van Collem. He expressed his gratitude that the Netherlands had been willing to call for the Polish government to issue his exit visa: “Who would have thought that a Catholic party in the Protestant Netherlands would stand up for a communist Jewish Pole.”Footnote64

The Emigration of Polish Jews

Ambassador Hagenaar reported that the number of emigrants had decreased drastically in the early 1970s. According to Hagenaar, this could be explained by the circumstance that the number of prospective emigrants had continued to decrease due to the shrinking reservoir of Polish Jews and the diminished necessity of emigration after the more liberal Gierek administration took control of the government. The reluctance of some Jews to emigrate was also assumed to play a role. Only a very small number of Jews would eventually not be allowed to emigrate, and this primarily included working-age physicians and engineers. Poland was happy to have Jews leave the country. Unlike the Soviet Union, which prided itself on celebrating national diversity, the Polish communist regime pursued the ideal of an ethnically homogeneous nation. In a confidential letter to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Hagenaar also illustrated Poland’s ambiguous stance with regard to Jews. While the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was extensively commemorated, this historic event was presented as an inextricable part of the Polish resistance. According to Hagenaar, antisemitism following World War II, including the pogrom in Kielce in 1946 and the anti-Zionist campaign in 1968, was ignored in Poland. In his view, antisemitism had simply taken another name: anti-Zionism and anti-Israelism.Footnote65

In all, 17,033 Polish Jews had received provisionally visas through the Israel division of the Dutch Embassy in Warsaw from October 18, 1967 through October 31, 1974. In this period, 13,854 Jews had travelled out of Poland through the Embassy. The other Jews who had applied but who had not left remained in Poland or had left in some other manner. A number had emigrated with visas from other embassies, particularly those of Denmark and Sweden. The Jewish emigrants include a high percentage of people with university degrees: 3423 individuals belonging to academic families had emigrated during the period 1967–1974, accounting for twenty-five percent of all emigrants. According to the Dutch ambassador Wil Pelt, an estimated 8000–9000 Jews were remaining in Poland in 1975, consisting primarily of senior citizens.Footnote66 After that date, the Dutch Embassy, due to the small numbers of emigrants, no longer kept the figures.

The Israel Interest Section in Warsaw

In March 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev became secretary-general of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. He distinguished himself through his efforts for social reform (perestroika) and political openness (glasnost) within the Soviet Union, as well as in the countries of the Warsaw Pact. At the same time, he wished to bring an end to the Cold War between East and West. This resulted in renewed cooperation between the Soviet Union and the West. Poland understood the importance of his policy with regard to Israel. During a meeting of the World Jewish Congress in New York in 1985, premier Wojciech Jaruzelski of Poland announced that the Soviet Union had given him room with regard to promoting relations between his country and Israel, although the Arabs were also pressuring him in the opposite direction. He asked the Congress to help Poland escape its antisemitic image in the United States and to provide assistance in the development of economic ties between Poland and the United States.Footnote67 After a return visit to Jaruzelski in Warsaw in December 1985, Elan Steinberg, the executive director of the World Jewish Congress stated: “We wanted to emphasize to the general that the road to the West can lead through Jerusalem.”Footnote68

In September 1986, a report from Jerusalem announced that Israel would be reopening its diplomatic mission in Warsaw. An official from the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Yoel Guilatt, was in Poland then, along with a team of specialists, in order to prepare to reopen the Israeli Embassy as a consulate. Guilatt arrived in Warsaw to supervise the renovation of the building and the installation of technical facilities.Footnote69 According to the Polish government’s spokesperson, Jerzy Urban, Poland did not wish to restore full diplomatic relations with Israel as long as Israel had not withdrawn from the occupied territories.Footnote70 One month later, official announcements from Israel and Poland stated that representatives from and to both countries had been officially appointed. The Israeli chargé d’affaires in Warsaw would be Mordechai Palzur. In response to the arrival of Palzur as head of the Israel Interests Section, the Dutch ambassador in Warsaw, Maxime van Hanswijck de Jonge, wrote a letter to Foreign Minister Hans van den Broek on November 9, 1986. Palzur accepted the fact that there was only one in charge, meaning the Dutch ambassador. He nevertheless wished to maintain a high political, economic and cultural profile in order to advocate for Israel’s interests in addition to helping create the conditions needed to generate acceptance for Israel’s own diplomatic delegation in Poland. The Dutch ambassador stated that he did not wish to adopt a hierarchical attitude towards Palzur, as long as he did not embarrass or challenge the position of the Dutch Embassy.Footnote71

Palzur was the first Israeli diplomat to serve in Eastern Europe, since the countries in the Soviet bloc had broken off diplomatic relations with Israel in 1967. It was a kind of experiment. For this reason, he was closely monitored, in essence working under a magnifying glass. The Polish government was afraid of negative reactions from the Arab countries, with which they had strong economic relations. The Soviet Communist Party was also pressuring Poland. Prior to the arrival of Palzur, there had been no tourism from Israel to Poland, as there was no Polish delegation in Israel to issue tourist visas. Palzur convinced the Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs to open Poland to Israeli tourists, particularly those of Polish heritage. According to estimates, about 500,000 Israelis had been born in Poland or had Polish roots.

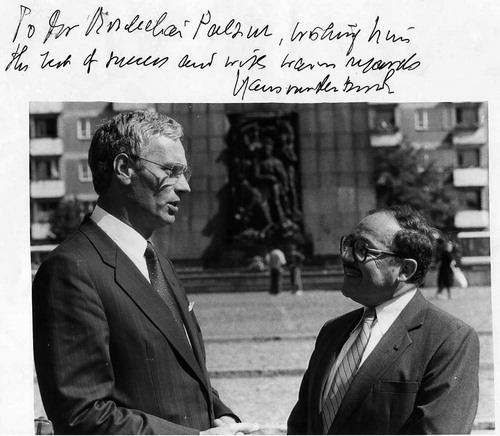

In 1987, the Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs, Hans van den Broek, paid an official visit to Warsaw. He also wished to visit Auschwitz, and he asked Palzur to accompany him there. The Polish authorities refused, arguing that the visit was bilateral and that there was no place for an Israeli diplomat. As a compromise, it was decided that Palzur would be allowed to accompany the Minister to a ceremony at the monument to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising ().Footnote72 That was the final disagreement before the full resumption of diplomatic relations between Poland and Israel.

Figure 1. The Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs, Hans van den Broek, and the Israeli chargé d'affaires, Mordechai Palzur, at a ceremony at the monument to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, 1987. In 1990, Palzur became Israel's first ambassador to Warsaw since the severance of relations in 1967. Text: “To Mr. Mordechai Palzur, wishing him the best of success and with warm regards, Hans van den Broek.” Reproduced by permission of Mr. Mordechai Palzur, Jerusalem.

In 1988, Poland openly admitted that the government had been politically incorrect in breaking off diplomatic relations with Israel and in its subsequent policy against Jews. This was announced in Israeli newspapers, reporting that the Polish leader Jaruzelski had sent a telegram in this vein to the participants of an international conference of Polish Jews in Jerusalem.Footnote73 During a November 1989 visit to his home country of Poland, the Israeli Vice-Premier Shimon Peres spoke with the Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs, Krzysztof Skubiszewski, concerning the resumption of the Polish-Israeli relations that had been broken off by Poland twenty-two years earlier. Skubiszewski admitted to Peres, “It was a major error on our part to break off relations in 1967.” It would take several months before the Polish Embassy in Tel Aviv would be reopened. The Polish government needed time to prepare the Arab countries for this step.Footnote74 Skubiszewski assured Peres that Poland would normalize relations with Israel within a few months. The Interest Section in Warsaw would be upgraded to an Embassy.Footnote75 In a letter to President Jaruzelski, Skubiszewski wrote that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs proposed that the process of resuming diplomatic relations should be concluded on February 27, 1990. The Ministry had conducted a series of clarifying conversations with the most important Arab countries, the Palestinian Liberation Organization and the Arab League. They took note of the intention to resume diplomatic relations with Israel, and they appreciated Poland’s applied method of pursuing the goal in phases, as well as the information that had been provided to them in advance in this regard. They worried that Poland’s political position with regard to the Arabs could change. The ambassadors pointed out that the Arab political position should remain clear in Poland, particularly on television, on the radio and in the written press.Footnote76

On February 27, 1990, Poland and Israel officially restored their mutual diplomatic relations with Palzur as the Israeli ambassador to Poland. In Warsaw, a protocol to this end was signed by the Israeli Minister of Foreign Affairs, Moshe Arens, and his counterpart, Skubiszewski. The Polish Minister once again expressed regret for the breach and once more referred to it as a serious political error that had been made under the leadership of the Communist Party and that was not consistent with Polish public opinion.Footnote77

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

André Roosen holds an MA in Dutch language and a BA in business economics. He works as a financial controller of sponsored research projects at the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Amsterdam. He co-edited the first Dutch translation of the letters of the Polish writer and fine artist Bruno Schulz in 2017. His research interests are the history of Polish and Russian Jews, the representation of the Holocaust in graphic novels, and the work, life and afterlife of Bruno Schulz.

Notes

1 Calkoen to Luns, June 6, 1968, 14206, Nationaal Archief, The Hague (henceforth NA). The Dutch Embassy represented Israel in the Soviet Union from February 12, 1953 to July 20, 1953, after the so-called Doctors’ Plot, a group of Jewish doctors from Moscow was accused of conspiring to assassinate Soviet leaders.

2 Rudnicki and Silber, Stosunki polsko-izraelskie (1945–1967), 705.

3 Szaynok, Poland-Israel 1944–1968, 403–4.

4 Bar-Noi, “The Soviet Union and the Six-day War,” 3.

5 Memorandum of Luns, June 20, 1967, 2.21.351, inventory number 1118, NA.

6 Szaynok, Poland-Israel 1944–1968, 406.

7 Calkoen to Luns, June 14, 1967, Z159, inv.no. 347, NA.

8 Luns to Calkoen, June 15, 1967, 14206, NA.

9 Luns to the Dutch ambassador in Jerusalem, June 16, 1967, 14206, NA.

10 Interview with the former secretary of the Dutch Embassy in Warsaw, Floor Kist, The Hague, August 1, 2013.

11 Banas, The Scapegoats, 86.

12 Calkoen to Luns, June 20, 1967, 14206, NA.

13 Memorandum of Kępiński to Naszkowski, June 19, 1967, department V, 1967. Israel, series 57/70, volume 3, Archiwum Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych, Warsaw (henceforth AMSZ).

14 Appendix to memorandum Kępiński to Naszkowski, June 19, 1967, department V, 1967, AMSZ.

15 Memorandum of Pietkiewicz to Naszkowski, June 19, 1967, department V, 1967, AMSZ.

16 European Directorate to Calkoen, June 27, 1967, 14206, NA.

17 Rudnicki and Silber, Stosunki polsko-izraelskie (1945–1967), 715–6.

18 Protocol Pietkiewicz to the Department of Legal Affairs-Treaties, June 20, 1967, Department V, 1967, AMSZ.

19 Calkoen to Luns, July 3, 1967, inv.no. 347, NA.

20 Calkoen to Luns, July 4, 1967, inv.no. 347, NA.

21 Calkoen to Luns, August 14, 1967, inv.no. 347, NA.

22 Chargé d’affaires, Pieter van Buuren in Jerusalem to Luns, March 26, 1968, 2.05.313, inv.no. 10966, NA.

23 “Polen wil geen Israëlische overwinningszegels” (Poland does not want Israeli victory stamps), Nieuw Israelietisch Weekblad (NIW), October 20, 1967, 10.

24 Calkoen to Luns, July 31, 1967, 14206, NA.

25 Luns to Calkoen, August 22, 1967, 2.21.351, inv.no. 1137, NA.

26 Memorandum of Luns, August 28, 1967, 2.21.351, inv.no. 1118, NA.

27 Willmann to Gomułka, March 22, 1968, file 94, collection 17, department IV, 1961–1969, Holland 20, volume 11, AMSZ.

28 Calkoen to Luns, March 20, 1968, 14206, NA.

29 Calkoen to Luns, March 25, 1968, 14206, NA.

30 Calkoen to Luns, May 24, 1968, 2.05.240, inv.no. 432, NA.

31 Calkoen to Luns, November 5, 1968, 130.23/6.2103, Israel State Archives, Jerusalem (henceforth ISA), The English translation of which by the Israeli secretary Yaakov Yanai in The Hague was forwarded to the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Jerusalem. It concerned the chancellery building on Krzywicki Street in Warsaw and the residential building on Queen Aldona Street, which was then the ambassador’s residence.

32 The Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Jerusalem to the Israeli ambassador in The Hague, Shimshon Arad, August 12, 1971, 130.23/8.2101, ISA.

33 Calkoen to Luns, June 6, 1968, 14206, NA.

34 Calkoen to Luns, November 27, 1968, 25803, NA.

35 Luns to Calkoen, December 5, 1968, 25803, NA.

36 Calkoen to Luns, December 11, 1968, 25803, NA.

37 Calkoen to Luns, May 20, 1969, 14208, NA.

38 Calkoen to Luns, August 16, 1968, 14207, NA.

39 Hagenaar to Luns, October 14, 1970, 14209, NA.

40 Calkoen to Luns, July 5, 1967, 14206, NA.

41 Ted de Ryck van der Gracht, former secretary of the Dutch Embassy in Warsaw, letter to the author, November 27, 2008.

42 Former secretary of the Dutch Embassy in Warsaw, Heldring, Het Saramacca Project, 9–10.

43 De Ryck van der Gracht, email to the author, November 5, 2014.

After fifty years it can be revealed that it was Austria. It can only honour them. I checked it, the ambassador was Johannes Proksch. A good friend of Calkoen. It was also a practical solution, because most of the emigrants went to Vienna by train.

44 Memorandum of Luns, June 20, 1968, 2.21.351, inv.no. 1119, NA.

45 Achter het nieuws, March 14, 1969, Archief Nederlands Instituut voor Beeld en Geluid, Hilversum (henceforth ANIBL). The show trial in New York did not materialize, but Wiesenthal did publish his documentation: Wiesenthal, Judenhetze in Polen.

46 Achter het nieuws, March 18, 1969, ANIBL.

47 “Wiesenthal ontmaskert Poolse antisemieten” (Wiesenthal exposes Polish antisemites), De Telegraaf, March 18, 1969.

48 Memorandum of Schiff to Luns. April 3, 1969, inv.no. 432, NA.

49 Appendix to the Report of the Proceedings of the Netherlands House of Representatives 1247 number 621, 1968–1969 Session.

50 Luns to Calkoen, April 9, 1969, inv.no. 10966, NA.

51 De Koster to Luns, April 15, 1969, inv.no. 10966, NA.

52 Televizier, December 2, 1969, ANIBL.

53 Hagenaar to Luns, April 21, 1971, inv.no. 10966, NA.

54 Annual Report on Poland of the Dutch Embassy in Warsaw, April 17, 1972, 26, inv.no. 296, Z159, NA.

55 Van Ebbenhorst Tengbergen to Schmelzer, March 8, 1972, 14210, NA.

56 Letter from the director of the party office of the KVP, H.A.H. Gribnau, to Schmelzer, March 15, 1972, 14210, NA.

57 Schmelzer to Van Ebbenhorst Tengbergen, March 20, 1972, 14210, NA.

58 Schmelzer to Gribnau, March 29, 1972, 14210, NA.

59 Van Ebbenhorst Tengbergen to Schmelzer, March 24, 1972, 14210, NA.

60 Kleisterlee to Schmelzer, February 9, 1973, 14211, NA.

61 Memorandum to Schmelzer, March 1, 1973, 14211, NA.

62 Schmelzer to Kleisterlee, March 12, 1973, 14211, NA.

63 “Petitie Kamerleden voor Trepper” (House of Representatives petition for Trepper), De Tijd, March 1, 1973.

64 “Trepper-petitie haalt Warschau wellicht niet” (Petition for Trepper might not reach Warsaw), Het Vrije Volk, March 1, 1973. (In November 1973, Trepper was allowed to leave after all).

65 Hagenaar to Schmelzer, May 8, 1973 inv.no. 347, NA.

66 Pelt to foreign minister Max van der Stoel, March 19, 1975, Code 9, 1975–1984, Embassy in Warsaw, Poland Archives, Archief Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken, The Hague (henceforth ABZ). The number of Jewish emigrants that left Poland through the Dutch Embassy in Warsaw is as follows: 1967: 215, 1968: 3064, 1969: 7651, 1970: 997, 1971: 977, 1972: 603, 1973: 236, 1974: 111, total: 13,854. The largest number of emigrants was in 1969 due to the proposition by the Polish Politburo in June to halt departures to Israel on 1 September of that year. That proposition was never implemented.

67 Govrin, Israel’s Relations, 202–12. Jaruzelski was in New York on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the United Nations.

68 “Jews are cautious after Soviet visit,” The New York Times, December 14, 1985.

69 “Heropening Israëlische consulaat Warschau” (Reopening of the Israeli delegation in Warsaw), NIW, September 26, 1986.

70 Govrin, Israel’s Relations, 213.

71 Van Hanswijck de Jonge to Van den Broek, November 13, 1986, Code 9, 912.3, ABZ.

72 Telephone interview with Mordechai Palzur, Jerusalem, September 8, 2013.

73 “Polen noemt anti-Israëlbeleid een vergissing” (Poland calls anti-Israel policy a mistake), De Telegraaf, February 6, 1988.

74 “Libanese oorlog laait op na moord op president” (Lebanese war flares up after President’s assassination), NIW, December 1, 1989.

75 “Polen wil met Israël herstel van relaties” (Poland wishes to restore relations with Israel), NIW, December 8, 1989.

76 Skubiszewski to Jaruzelski, December 21, 1989, AMSZ.

77 Govrin, Israel’s Relations, 225.

Bibliography

- Banas, Josef. The Scapegoats. The Exodus of the Remnants of Polish Jewry. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1979.

- Bar-Noi, Uri. “The Soviet Union and the Six-day War. Revelations from the Polish Archives.” Cold War International History Project e-Dossier Series 8, Washington, DC, 2003.

- Dahlmann, Hans-Christian. “Antisemitismus in Polen 1968. Interaktionen zwischen Partei und Gesellschaft.” PhD. diss., Universität Münster, Osnabrück, Fibre, 2013.

- Govrin, Yosef. Israel’s Relations with the East European States. From Disruption (1967) to Resumption (1989–1991). London: Vallentine Mitchell, 2011.

- Heldring, Alexander. “Het Saramacca Project. Een plan van joodse kolonisatie in Suriname 1946–1956.” PhD. diss., Verloren, Hilversum, 2011.

- Plocker, Anat. “Zionists to Dayan. The Anti-Zionist Campaign in Poland, 1967–1968.” PhD. diss., Stanford University, 2009.

- Stola, Dariusz. “Anti-Zionism as a Multipurpose Policy Instrument. The Anti-Zionist Campaign in Poland, 1967–1968.” In Anti-semitism and Anti-Zionism in Historical Perspective. Convergence and Divergence, edited by Jeffrey Herf, 159–185. Abingdon: Routledge, 2007.

- Stola, Dariusz. “The Hate Campaign of March 1968. How did it Become Anti-Jewish?” Polin 21 ( Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009): 16–36.

- Szaynok, Bożena. Poland-Israel 1944–1968. In the Shadow of the Past and of the Soviet Union. Warsaw: Institute of National Remembrance, 2012.

- Szymon, Rudnicki, and Marcos Silber, eds. Stosunki polsko-izraelskie (1945–1967). Wybór dokumentów. Warsaw: Naczelna Dyrekcja Archiwów Państwowych, 2009.

- Wiesenthal, Simon. Judenhetze in Polen. Vorkriegsfaschisten und Nazi-Kollaborateure in Aktionseinheit mit Antisemiten aus den Reihen der KP Polens. Bonn: Rolf Vogel, 1969.