ABSTRACT

This article shows how a specific set of Italian economic ideas, which were first formulated in the first half of the twentieth century and later espoused by a network of economists from Bocconi University, Milan, came to play an important role in shaping European policy responses to the Great Recession and establishing the doctrine of ‘expansionary austerity.' It argues that two factors – the formalization of these ideas in the language of mainstream economics and the establishment of professional networks that operated across a host of linked ecologies – contributed to their influence. The result was a ‘boomerang effect’, or a transfer of economic ideas from the European periphery to centers of policy-making power and back again. This phenomenon is understudied in the existing political economy literature, which tends to assume that ideational traffic is one-way, with ideas originating in centers of power and travelling from there to the periphery.

INTRODUCTION

From the outset the idea of European unification has served as a blank canvas on which thinkers of divergent political and economic stripes have projected their visions, ranging from labor parties’ hopes for a ‘social Europe' to Friedrich Hayek's free-market ‘interstate federalism’. Accordingly, this article treats European co-operation as an active site of ideational contestation (Mudge and Vauchez Citation2012; Parsons Citation2006; van Apeldoorn Citation2002). It departs from the finding that a set of Italian liberal economic ideas which framed European co-operation as a means to constrain statist policies and fiscal expansion, formulated by Italian economist Luigi Einaudi (Einaudi et al. Citation2014) in the first half of the twentieth century, became influential in European Union (EU) policy-making in the aftermath of the Lehman crisis, though they were not very prominent when they were originally formulated (Blyth Citation2013).

While a general shift away from embedded liberalism in the last 40 years (Blyth Citation2002) almost certainly made politicians and policy-makers more open to market liberal ideas, it does not explain how this particular set of ideas could become significant. Indeed, most of the literature on economic ideas stresses the dominance of Anglo-Saxon and German ideas, with little allowance for comparatively peripheral countries like Italy as centers of epistemic innovation (McNamara Citation1998; Schmidt and Thatcher Citation2013). This case is therefore an unusual case of a ‘boomerang effect’, in which ideas originate in the periphery, gain legitimacy in the core and are diffused back to the periphery from there.

In trying to understand the ascendance of these particular ideas, this article makes three related claims. The first is that even abstract economic theories understood to have global purchase have roots in a particular time and place. The most prominent contemporary proponent of the economic ideas in question, Harvard political economist Alberto Alesina, has been referred to as Einaudi's ‘full heir' (Santagostino Citation2012: 380). His policy vision is most clearly articulated in the principle of ‘expansionary austerity’, the notion that cutting public spending can lead to growth. This principle is embedded in a very specific view of European co-operation as a means to constrain government spending and ensure monetary co-operation. Though deceptively simple on the surface of it, this political vision has been decades in the making and is composed of several interlocking parts, which hearken back to Einaudi's thoughts (Einaudi et al. Citation2014). His ideas, in turn, were heavily influenced by political and economic realities that were particular to Italy. In this sense the genesis of the economic theory of expansionary austerity cannot be disentangled from the traumas of Italian history.

Second, the article argues that the contemporary influence of these ideas was facilitated by the fact that their proponents, many of whom were centered in Bocconi University in Milan, Italy, were adept in the formalized language of neoclassical economics. They could thus formulate their ideas in a way that was compatible with the mainstream of the discipline. By contrast, this shared mathematical language was not yet fully formulated in Einaudi's time (Fourcade Citation2006).

Third, formalization gave advocates of these ideas access to international centers of epistemic power, including élite United States (US) universities, EU institutions and international organizations (IOs). This was at least in part the result of a conscious effort by Bocconi University, which developed a clear strategy of promoting its graduates in élite institutions, while also allowing them to maintain ties to Bocconi. Under the leadership of Francesco Giavazzi, Bocconi teamed up with the American National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) and the European Commission and made a successful effort to recruit internationally renowned economists and to disseminate their work in top-tier journals.

The article proceeds in three parts. First, it posits its theoretical underpinnings, with a focus on the formalization of economic knowledge and the role of transnational networks in diffusing it. Second, it discusses Einaudi's (Einaudi et al. Citation2014) economic ideas and puts them in the context of Italian economic history. Finally, it provides a systematic overview of the component parts of expansionary austerity through the prism of Alesina's research and traces the professional trajectory of several of his co-authors from Bocconi University across different sites of power, furthering the argument that strong networks and access to revolving doors enabled these policy-minded economists to influence European crisis politics.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The role of economists as agents of globalization is often understood as mostly unidirectional: intellectual models are generated in American or North-West European centers of power and then exported to the periphery. Thus, a number of studies have noted that graduate training in American economics departments shapes the professional identities and preferences of policy players and academic economists worldwide (Colander Citation2005; Fourcade Citation2006). Similarly, foreign economists trained in prestigious US academic institutions often become economic policy leaders in their own countries. This dynamic was at work in the story of the Chicago Boys (Babb Citation2001; Markoff and Montecinos Citation1993), with more recent scholarship arguing that the same happened in other parts of the world as well (Chwieroth Citation2010).

Others have noted that things are not always this simple. Dezalay and Garth (Citation2002), for example, argue that the transmission of economic ideas from core to periphery also represented the extension of Western intellectual ‘palace wars’ to the Global South. Similarly, Marion Fourcade's account of the internationalization of the economics profession takes the dynamic nature of diffusion into account. Fourcade argues that the ongoing reconstruction of economies worldwide is ‘symbiotically related to the ongoing transformation of the intellectual and professional jurisdictions of economists’ (Fourcade Citation2006: 183–4) – a claim that also serves as the departure point of this account, albeit with certain modifications as argued below.

Fourcade posits that three factors have been critical to the deep institutionalization of the economics profession on a global scale. The first was the establishment of a broadly universalistic rhetoric, under which ‘economics knowledge appeared inherently transferable and “transformative,” both politically and institutionally, thereby authorizing easy replication and diffusion independently from the national context' (Fourcade Citation2006: 156). More concretely, this universalization of economic knowledge rested on mathematical formalism, methodological universalism and theorizing that treated social units as comparable.

Second, and closely connected to the process of rhetorical universalization, was the transformation of economic knowledge into a technology of political and bureaucratic power. Originally the nation state was the locus of this transformation: in the first half of the twentieth century, economics was incorporated into the toolkit of governments so that economic outcomes might be engineered to suit statist political goals. Ironically, with the resurgence of market-centric neoclassical economics in the 1970s, the nation state was to an extent pushed out of this equation. As a result, the economics profession not only superseded its national loci, but also played a role in circumscribing the economic tools available to nation states. This coincided and dovetailed with the emergence of a transnational capitalist class with considerable lobbying power (see also van Appeldoorn Citation2002; Van der Pijl Citation1998).

Third, Fourcade argues that the existence of transnational linkages, or networks, centered in the United States, played an important role in the internationalization of the economics profession. Here, she stresses the importance of education in mediating the relationship between core and peripheral states. For example, the fact that in the year 2000 more than half of all students pursuing a PhD in economics in American universities were foreign, and that the impact of this was highly asymmetrical for periphery and core, is crucial to her argument. She argues that for peripheral states transnational linkages have been important sources of legitimation, ‘both virtually through the uniformizing culture of the neoclassical paradigm, and materially through the countless formal and informal linkages with international organization and foreign scholarly and professional communities’ (Fourcade Citation2006: 157). Conversely, the economics profession in élite institutions in core states derived symbolic and material rewards from influencing other parts of the world (Fourcade Citation2006).

Though compelling, Fourcade's analysis, like that of a number of other scholars (Babb Citation2001; Markoff and Montecinos Citation1993), runs the dual risk of overestimating the coherence of American graduate education and portraying foreign students as blank slates that simply absorb what they are taught upon arrival.Footnote1 By contrast, this article argues that American expert networks, and academia in particular, are somewhat porous and open to foreign participation and influence. What seems like influential ‘Anglo-Saxon' economic thought can therefore have originated in other parts of the world. Graduate students and professors that come to the United States can carry with them their own national traditions and translate them into the universalizing rhetoric of economics, In this way the prestige of élite American institutions can be used to legitimize and diffuse economic logic that stems from other national traditions through what can be termed a ‘boomerang effect' (Keck and Sikkink Citation1998). In this sense the relationship between ideas and centers of power is less linear and straightforward than it appears. The theoretical goal of the article, then, is to extend Fourcade's reasoning by arguing that peripheral states can generate mainstream economic knowledge, as well as absorb it.

Methodologically, the article makes use of process tracing. Tracing the lineage of expansionary austerity – both its deeper historical roots in Einaudi's (Einaudi et al. Citation2014) work and its contemporary refinement through Alesina's corpus – serves the purpose of showing that these ideas were at least in part exogenous to the policies they later informed and therefore not just post hoc justifications. However, as Jacobs notes ‘[d]emonstrations of antecedent origins do not, by themselves, establish exogeneity’, as decision-makers can simply cherry pick the sets of ideas that best suit their interests. It is therefore also important to demonstrate both that the ‘carriers’ of new ideas are prominent enough to shape the broader intellectual environment and to identify plausible pathways, or ‘transmission belts’, for disseminating their ideas (Jacobs Citation2011). This article finds that Alesina was a high-status innovator and carrier of the expansionary austerity thesis and that his network of co-authors, with connections to transnational centers of epistemic and political power, acted as a transmission belt for that thesis. The benefits of studying carriers and transmission belts are obvious in that they are observable in a way that ideas themselves are not.

While this case does not provide a ‘smoking gun' to show that universalizing language which distances national economics from their local roots, strong networks and access to transnational sites of power contribute to the ascendency of certain sets of economic ideas, it can act as a ‘hoop test’. While a hoop test isn't enough to affirm a hypothesis, but it can be used to establish necessary, if not sufficient conditions (Mahoney Citation2012; Van Evera Citation1997). The fact that Alesina had access to these while Einaudi did not also acts as a kind of counterfactual ‘hoop test' of this proposition.

EINAUDI'S VISION: EUROPE AS A BUTTRESS AGAINST FASCISM

Gualmini and Schmidt (Citation2013) argue that Italy's post-war economic liberalism (or liberismo) was different from other forms of liberalism in that it emphasized skepticism of mass politics and the state and preferred markets instead. This echoed German Ordoliberalism and foreshadowed the swing to neoliberalism in the 1970s (Ban Citation2012). Einaudi's liberismo was derived not only from the classics of liberal thought, but also from personal experiences that were particular to Italian history (Forte and Marchionatti Citation2012). After the end of the First World War, parts of Northern Italy experienced the so-called Two Red Years (1919–1920), a period when socialist, social-Catholic and communist movements occupied land and factories and pushed for progressive wage and labor legislation. Moreover, in many municipalities unions were powerful enough to dictate political outcomes. In reaction, the Italian industrial and agrarian élite threw its weight behind the fascist movement. Soon enough, however, it became apparent that fascism was a force in its own right that could not be controlled by the old élites. Instead, it channeled its energies into constructing a state-led economic model and gutting Italy's liberal institutions (Battente Citation2000).

Einaudi, who had critiqued the old liberal order in Italy for falling short of the liberal ideal, was a vocal opponent of statist experiments in general and Italian fascism in particular. By 1943, his anti-fascist stance had become a liability and, fearing for his life, he fled Italy, crossing the Alps into Switzerland on foot at the age of 69. It was in this historical context that Einaudi formulated his view of European integration as a liberal vehicle for constraining state intervention and buttress against fascism (Forte and Marchionatti Citation2012; Gualmini and Schmidt Citation2013).

Though his vision for a liberal Europe was sharpened by the threat of fascism, Einaudi had begun arguing for a federal system of European institutions based around a strong independent central bank, a federal system of finance and a unified customs system that could curtail ‘feelings of nationality' as early as 1916 (Masini Citation2012: 43). He had a deep aversion to inflation, which he believed undermined the propensity to save and innovate and could act as a gateway to fascism. It was this fear that led him to advocate for an independent central bank at a time when this idea was barely known outside of Germany. Accordingly, he supported constitutional rules banning fiscal deficits (Forte and Marchionatti Citation2012).

Einaudi did not subscribe to the post-war Keynesian consensus that the Gold Standard was a recipe for disaster. To the contrary, he believed that European integration should be based on monetary arrangements that closely approximated the gold standard (Einaudi et al. Citation2014). Writing on the economic institutions of the future ‘European Federation’, as he called it, he argued that they should have a constraining effect, similar to the Gold Standard, and that the right to issue currency should be moved from the national to the federal level. This would make fiscal activism impossible and forge an austere political order in which the central bank would be spared the role of lender of last resort for the state. The larger goal was the abolition of monetary sovereignty (Santagostino Citation2012).

The fascist years aside, Einaudi's career was successful in settings as diverse as academia, media and politics. As a professor of economics both at the University of Turin and at Bocconi University, he taught many of Italy's best-known twentieth-century economists. It bears mentioning that though Einaudi had a clear vision for Europe, he was by no means a dogmatic mentor and his students’ views sometimes diverged greatly from his.Footnote2 After the Second World War he was one of the founders of the Italian Republic, boosted by anti-fascist credentials. He held a number of public offices, serving as minister of finance, governor of the central bank and finally as president of the new Republic. Einaudi also had an international presence as The Economist’s Italian correspondent. Moreover, he was an active member of the transnational liberal networks that established Colloque Lippman (1938) and the Mont Pelerin Society (1947), both of which played a crucial role in the formation of modern neoliberalism. As such, he was Italy's only internationally recognized liberal economist at the time (Mirowski and Plehwe 2009; Peck Citation2010).

However, professionally successful though he was, Einaudi's vision did not carry the day when it came to creating the post-war international monetary and financial institutions or in Italian politics. The former were constructed along Keynesian lines, while the latter were characterized by a mixture of ‘public neo-capitalism’, party patronage and clientalism (Schmidt and Thatcher Citation2013). In this context it is important to note that the international networks that Einaudi was part of, like the Colloque Lippman and the Mont Pelerin Society, were originally relatively diverse and marginal umbrella organizations that were not embedded in transnational sites of power. Indeed, they were founded because their early members saw liberalism as threatened by both Keynesian planning and Marxism (Mirowski and Plehwe 2009; Schmidt and Thatcher Citation2013). Moreover, Keynesians replaced liberals in key sites of institutional power such as universities and IOs (Chwieroth Citation2010; Pauly Citation1997).

Nor did Einaudi and his peer liberals present a united front in terms of methodology. Though Einaudi was interested in methodology and argued for ‘working at the same time both with a deductive and inductive manner of proceeding, abstract reasoning and its empirical verification” (cited in Forte and Marchionatti Citation2012: 365), a great deal of his work took the less formalized shape of moral and political essays and economic history (Einaudi et al. Citation2014). At a time when the Chicago School and its followers were preparing anti-Keynesian attacks using the language of econometrics, Einaudi's methodology seemed outdated and unscientific. In short, lacking both an embedded transnational network and a transferable language to diffuse his ideas, Einaudi's work did not have an international resonance during the early post-war decades.

Liberal economic thinking remained mostly dormant in Italy from the 1950s to the 1970s, and resurfaced only in the 1980s and 1990s in the work of a new cohort of economists at Bocconi, many of which did their graduate work in the United States and Britain. Steeped both in the Italian tradition and in the methodologies of Anglo-American academia, they borrowed many of Einaudi's ideas. Yet, unlike him, they formalized their work, published it in internationally recognized journals and acceded to positions of influence in the ‘linked ecologies’ (Seabrooke and Tsingou Citation2015) of transnational sites of power (Blyth Citation2013; Gualmini and Schmidt Citation2013; Radaelli Citation2002). The most influential of these ideas was the thesis of expansionary austerity, to which I turn next.

ALESINA'S VISION: EUROPEAN INTEGRATION AS A CONSTRAINT FOR PROFLIGATE WELFARE STATES

Alesina as an influential ‘carrier' of expansionary austerity

Alberto Alesina is the most prominent and successful proponent of expansionary austerity. Over the course of the last 30 years he has published over 90 articles, most of them pertaining to macroeconomic questions. Of these, many have been published in top journals such as American Economic Review, European Economic Review, Journal of Public Economics and Quarterly Journal of Economics, to name but a few. He earned his PhD from Harvard University in 1986 and is currently the university's Nathaniel Ropes Professor of Political Economy.

A graduate of Bocconi, Alesina has also remained closely affiliated with that university, doing research stints there and working with faculty. He has been referred to as Einaudi's ‘full heir' and has made his admiration for Einaudi's work clear, notably in an introduction to a recent collection of Einaudi's essays (Einaudi et al. Citation2014). Indeed, many of Einaudi's ideas percolate in Alesina's research, and the two share a core vision of a liberal Europe as a means to constrain state economic activism and support free markets. Unlike Einaudi, however, Alesina and his larger network have had a profound influence on economic policy-making, as demonstrated most clearly by Blyth (Citation2013). To date, the policy of austerity has been maintained in Europe, even as economic and social outcomes have continued to disappoint and frustrate (Matthijs and McNamara Citation2015).

Though Alesina's core argument – Europe has been profligate and must now curtail spending to grow again – appears both simple and intuitive, the economic theory underpinning it was decades in the making. Seemingly disparate threads of research, animated by themes that Einaudi also grappled with, had to be joined together for the formula for expansionary austerity on a European level to add up. Specifically, five logical steps were required to get there, each of which is discussed in more detail below:

Democratic political systems have an inherent tendency to build up excessive debt.

Much of the debt is used for welfare transfers and austerity should therefore be geared towards reining in welfare spending rather than raising levels of taxation.

Such spending cuts are both economically and politically viable.

Governments benefit from a degree of discipline and insulation from political pressures, allowing them to enforce austerity.

European institutions are ideally placed to provide such discipline and insulation.

A great deal of Alesina's early research focused on the potentially detrimental impact of democratic politics for macroeconomic outcomes, particularly for levels of public debt (Alesina Citation1987; Alesina Citation1988b; Alesina and Carliner 1991; Alesina, Cohen and Roubini Citation1991; Alesina and Roubini Citation1992; Alesina and Sachs Citation1988). He argued that disagreement between current and future governments can lead to debt accumulation, even when the majority of voters oppose it (Alesina and Tabellini Citation1989, Citation1990; Tabellini and Alesina Citation1990). Moreover, this research shows that high debt and an unstable political situation with frequent shifts between parties with divergent agendas results in fiscal deadlock and increases the potential for capital flight, exchange rate instability and inflationary pressures. The dominance of one political group, by contrast, results in a more stable situation (Alesina Citation1988a; Alesina, Mirrlees and Neumann Citation1989; Alesina and Rosenthal Citation1989; Alesina and Tabellini Citation1989, Citation1992). This, however, is unlikely to happen in an electoral system that allows different groups to engage in a ‘war of attrition' over who will shoulder the burden of adjustment, thereby postponing the moment of reckoning, making it worse in the process (Alesina Citation1994; Alesina, Ardagna and Trebbi 2006; Alesina and Drazen Citation1991). High debt can then become self-perpetuating, since citizens in indebted countries lose confidence in the financial system and choose to invest in foreign rather than domestic debt (Alesina, Prati and Tabellini Citation1990).

But why do states take on so much debt to begin with? A number of Alesina's research papers depart from the observation that over the course of the last 30 years growth in government spending has resulted not from the purchase of goods and services, as was formerly the case, but rather from welfare transfer programs. Moreover, he argues that welfare systems are rapidly becoming unsustainable (Alesina and Perotti Citation1995a, Citation1996a, Citation1996c, Citation1999), that they undermine European competitiveness (Alesina and Perotti Citation1997b) and that high government spending is strongly correlated with corruption (Alesina and Angeletos Citation2005). These observations led Alesina and Bocconi professor Roberto Perotti to conclude that fiscal adjustment should consist not of higher levels of taxation, but of significant cuts in the welfare state that could reverse this dangerous historical trend (Alesina and Perotti Citation1995a).

Moreover, Alesina and Perotti and Ardagna suggest that such fiscal adjustment could actually have expansionary outcomes (Alesina and Perotti Citation1995a; Alesina and Ardagna Citation1998). This ran counter to an earlier consensus that austerity was inherently contractionary. Looking at OECD countries over three decades, Alesina and Perotti found that even ‘harsh' fiscal adjustments were not systematically followed by recessions. On the contrary, sometimes adjustment were followed by growth. However, outcomes depended on the ‘type' of fiscal adjustment pursued. Adjustments that relied on spending cuts as opposed to tax increases were not just a historical corrective but also more likely to improve the fiscal situation, more likely to last (Alesina and Ardagna Citation1998, Citation2010, Citation2013; Alesina and Perotti Citation1996c, Citation1997a; Alesina and de Rugy Citation2013), and less costly in terms of output (Alesina, Favero, and Giavazzi Citation2015). These findings were bolstered by arguments that public spending on wages in particular has a very negative impact on profits and business investment, even more so than taxes (Alesina, Ardagna, Perotti and Schiantarelli Citation2002). Importantly, Alesina and his co-authors also argued that governments that pursue austerity are no more likely to be voted out of office than those that pursue activist fiscal policies (Alesina, Carloni and Lecce Citation2013; Alesina, Perotti and Tavares Citation1998).Footnote3

Since Alesina saw the problem of debt as stemming from politico–institutional variables, his solution lay in altering these, preferably by insulating government institutions from political interference. While he argued that balanced budget legislation was probably too inflexible (at least at the national level, though he did find it very successful in managing state finances in the United States [Alesina and Bayoumi Citation1996; Alesina, Perotti and Spolaore Citation1995]), he advocated a reduction of veto points that could delay fiscal adjustment and the centralization of power over budgetary matters in the executive (Alesina and Perotti Citation1996a, Citation1999). He was also an avid advocate of independent central banks (ICBs) that would restrain government access to seigniorage (Alesina and Perotti Citation1995b). In 1985, Kenneth Rogoff had argued that ICBs reduce inflation, but at a cost in output variability. Alesina, along with fellow Harvard economist Lawrence Summers, took the argument further. They found that ICBs bring about low inflation at no apparent real costs. Rather, the variability was caused by exogenous shocks and political shifts that heighten uncertainty (Alesina and Gatti Citation1995; Alesina and Summers Citation1993).

In turn, this institutional vision was part and parcel of a very specific view of European co-operation as the ideal venue to provide market discipline and a degree of insulation from factional national politics (Alesina and Grilli Citation1992). Europe's role should be to guarantee free trade and monetary unification, centered on independent and clearly delineated institutions, while leaving national governments room for maneuver in other matters (Alesina et al. Citation1992; Alesina and Grilli Citation1993). Monetary unification, in particular, should provide external fiscal discipline, when it could not be mustered domestically.

This embrace of monetary union did not, however, extend to fiscal union. Discussing redistribution within the European Union, Alesina and Perotti stressed the attendant political risks, stemming from uncertainty regarding tax rates and the difficulty of aggregating diverse preferences. They concluded that fiscal redistribution within Europe would take integration too far (Alesina and Perotti Citation1998). Elsewhere Alesina made a similar case that:

Europe is going too far on many issues that would be better dealt with in a decentralized fashion, while it is not going far enough on policies that guarantee the free operation of markets both across and within the countries of the Union. (Alesina and Wacziarg Citation1999; see also Alesina, Angeloni and Etro Citation2005; Alesina, Angeloni and Shuknecht Citation2005)

Arguments along these lines are also the subject of Alesina's 2006 book with Bocconi economist Francesco Giavazzi, The Future of Europe, in which they compare European welfare states to a ‘frog in slowly warming waters', boiling alive without the wherewithal to save itself (Alesina and Giavazzi Citation2006: 10).

Alesina and Giavazzi's fears hearken back to Einaudi's worries that the Schuman Plan for the European Steel and Coal Community would become a French dirigiste project that marginalized liberal policies. In fact, Alesina's views mirror Einaudi's in several respects. Most of his major themes are present in Einaudi's earlier work: electoral politics as potentially detrimental for economic outcomes, the dangers of welfare spending, focus on fiscal retrenchment, the need for ICBs and constitutional rules to impose monetary and fiscal discipline, and the hope that European institutions can curtail national excesses. In sum, then, Alesina's vision is composed of several interlocking and interdependent parts that echo Einaudi's earlier preoccupations, and which have been articulated in articles and studies published in internationally recognized economics journals. Thus, when the European crisis came to a head, Alesina's oeuvre offered a comprehensive and intuitive interpretation of the crisis, as well as a concrete set of policy reactions that European policymakers could grab ‘off the shelf'.

The Bocconi network as a ‘transmission belt' of expansionary austerity

Importantly, however, Alesina has not been alone in promulgating the policy of expansionary austerity and the ideas of liberismo more generally. Most of the articles cited above are co-authored, often with fellow Bocconi graduates. Many of Alesina's Bocconi co-authors are established in transnational sites of epistemic and political power in academia, policy-making, think tanks and the global financial sector. Publicly available curriculum vitae information shows that their positions include tenured posts and affiliations at the economics departments of élite universities such as Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Stanford, University of Chicago, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, University of California, Carnegie Mellon University, European University Institute, Boston University, Boston College, Cambridge, Wellesley, London School of Economics and London University.

The Bocconis have also sat on the boards of prestigious academic journals, authored and edited books published at top academic presses and obtained a number of large American and European grants. Many have also held prominent positions in respected transatlantic institutions for the dissemination of policy-relevant economic research such as NBER, the American Finance Association (AFA) and the Center for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), Bruegel and the Aspen Institute.

Moreover, their success has not been isolated to academic positions. As their academic star has risen, many members of the Bocconi network have gained access to the revolving door between academia and the economic policy-making sphere. Some of them cut their teeth on emerging markets’ financial crises and their macroeconomic implications as consultants or fellows for the Bretton Woods institutions: Giavazzi served as an external evaluator for the IMF's research; Silvia Ardagna was a visiting fellow at the International Monetary Fund's (IMF's) Fiscal Affairs Department; Alesina was a visiting researcher and Perotti and Tabellini were consultants for the Fiscal Affairs Department. Alesina was a visiting scholar at the Macroeconomic and Growth Division and the Public Economics Division of the World Bank (WB); Perotti, Tabellini and Favero were economic consultants for the WB; and Angeloni worked with the Bank as a representative of the Italian government.

The group was even more prominent in EU institutions. Alesina was a regular at the ECB and a frequent guest and speaker at high level European Commission and European Council events. Ardagna and Perotti consulted for the ECB and the former also consulted for the Directorate General for Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN). Before becoming finance minister for the Mario Monti government, Grilli was first vice-president and then chair of the EU's Economic and Financial Committee (EFC), an influential body established by the Maastricht Treaty ‘to keep under review the economic and financial situation of the Member States and of the Community and to report regularly to the Council and the Commission on this subject’. In practice, this means that the EFC prepares the agenda of the European Council with regard to monetary and fiscal policy issues and serves as a framework for ECB–European Council dialogue. It is interesting to note that the idea of expansionary austerity has had much more resonance and impact in the EU, where this network was dense, than in the IMF where it was sparser.

However, even as they become members of these transnational sites of power, many also stayed focused on the realities of domestic economic policy. Almost all worked as consultants or had short stints as advisers for powerful government agencies such as the French Treasury, the New York Federal Reserve, the Italian Treasury and the Italian central bank. Even more prestigiously, Tabellini worked as economic advisor to the Italian prime minister Romano Prodi, and during the sovereign debt crisis Giavazzi served as the economic advisor of Mario Monti (another Bocconi graduate) while sitting on his Government Spending Review. Most famously, Grilli left the top job at the EFC to manage Italian austerity as minister of economics and finance in the Monti government from 2012 to 2013.

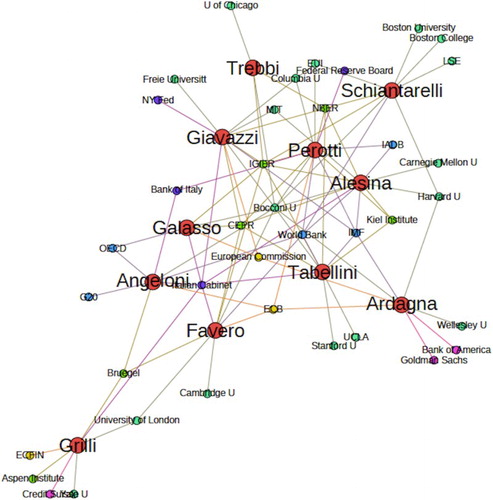

These densely interconnected career trajectories across an array of transnational sites of power are illustrated in the network map in . Red nodes, slightly larger than the rest, represent Alesina and his Bocconi co-authors on expansionary austerity. The smaller nodes represent their various affiliations, distinguished by color: Academic affiliations show as turquoise nodes, think tanks are green, IOs blue, European institutions yellow, national government agencies purple and financial entities pink. Each of these smaller nodes is also labeled by the name of the institution in question.

Figure 1. Network illustrating the interconnected career trajectories of Alesina and his austerity co-authors across an array of transnational sites of power

Thus, in addition to being prominent enough an academic to shape the broader intellectual environment and act as a ‘carrier' of a clearly articulated economic and political vision, Alesina was part of a network that had access to the revolving doors of several transnational sites of power. It seems reasonable to assume that this tightly knit network served as a ‘transmission mechanism' to further the policy vision of expansionary austerity.

CONCLUSION

This article has sought to further our understanding of how a set of Italian economic ideas, which were originally formulated in the first half of the twentieth century and then advanced and diffused through a network of academics affiliated with Bocconi University, could become prominent in shaping European policy responses to the Great Recession. The article has stressed the fact that the economic view of the Bocconis, most clearly articulated in the policy of expansionary austerity, is part and parcel of a vision of Europe as a means to constrain the economic sovereignty of European states and curtail government spending.

In its earlier iteration this stance was meant to check the power of fascism, but in its contemporary form it has been reinterpreted as a means to deal with democratic inefficiencies and corruption. In this way the article has underscored the fact that international economic policies sometimes have distinctively national roots and that not all influential economic policies are Anglo-Saxon or German in origin, as much of the literature suggests. In this case, a set of economic ideas that have been felt keenly in Europe's southern and eastern periphery actually originated in Southern Europe.

This insight complements earlier work on the importance of the vincolo esterno (foreign constraint) in Italian politics, which focused on the ways in which weak domestic political actors could leverage European pressures to push through otherwise difficult reforms and strengthen their own mandates (Dyson and Featherstone Citation1996; Featherstone Citation2001; Ferrera and Gualmini Citation2004). This literature, however, tends to treat European policies as ‘unstoppable and largely uncontrollable by Italy' (Featherstone Citation2001: 4). This article contributes to this debate by shedding light on the origins of the vincolo, while also demonstrating that it is not always as esterno as it might seem. It suggests that this journey of ideas from periphery to core and back again can be understood as an ideational ‘boomerang effect'.

The case of the Bocconis suggests that such an effect can only take place given certain conditions: in order for these ‘peripheral ideas’ to gain legitimacy and influence, they had to be translated into the abstract and universalizing logic of mainstream economics and espoused by an influential network of scholars with access to established sites of power.

This insight stands to further our understanding of the ideational room for maneuver in contemporary European crisis economics. It suggests that more heterodox approaches to economics are likely to have limited resonance, even when their proponents hold positions of power. Similarly, even intellectuals that are part of the mainstream tradition are unlikely to have a significant impact on policy-making if they lack a strong high-status international network. If this is correct and those already embedded in the dominant intellectual tradition and influential networks are most likely to impact policy, the upshot is that ideational room for maneuver is rather restricted. This, in turn, may go some way towards explaining the resilience of austerity politics, even in the face of popular dissent and disconfirming evidence.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My sincere thanks go to Mark Blyth, Cornel Ban, Daniel Béland, Martin Carstensen, Thomas Ferguson, Richard Locke, Daniel Mügge, Michal Ben Noah, Vivien Schmidt, Leonard Seabrooke, Jazmin Sierra, Prerna Singh and two anonymous reviewers; moreover to the participants in the Copenhagen Business School's Snekkersten workshop on ideas and power in international political economy, the European Commission's ‘Global Reordering: Evolution through European Networks’ (GR:EEN) and the Brown graduate workshop in comparative politics. The usual disclaimers apply.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Oddný Helgadóttir

Oddný Helgadóttir is a doctoral candidate at Brown University.

Notes

1 It should be noted, however, that Fourcade argues that French thinkers, steeped in the French tradition, had an impact on American economic thought, in a pattern similar to that discussed in this article. I thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

2 I thank Thomas Ferguson for this insight.

3 It should be noted, however, that Perotti went on to break with this view and became a critic of expansionary austerity (Perotti Citation2011).

REFERENCES

- Alesina, A. (1987) ‘Macroeconomic policy in a two-party system as a repeated game’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 102: 651–78. doi: 10.2307/1884222

- Alesina, A. (1988a) High Public Debt: The Italian Experience, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Alesina, A. (1988b) ‘Macroeconomics and politics’, in NBER Macroeconomics Annual 3, Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Alesina, A. (1994) ‘Political models of macroeconomic policy and fiscal reforms’, in S. Haggard and S. Webb, Voting for Reform, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 37–60.

- Alesina, A. and Angeletos, G. (2005) ‘Corruption, inequality and fairness’, Journal of Monetary Economics 52(7): 1227–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoneco.2005.05.003

- Alesina, A., Angeloni, I. and Etro, F. (2005a) ‘International unions’ American Economic Review 95(3): 602–15. doi: 10.1257/0002828054201279

- Alesina, A., Angeloni, I. and Shuknecht, L. (2005b) ‘What does the European Union do?’ Public Choice 123: 275–319. doi: 10.1007/s11127-005-7164-3

- Alesina, A. and Ardagna, S. (1998) ‘Tales of fiscal adjustments’, Economic Policy 27: 489–545.

- Alesina, A. and Ardagna, S. (2010) ‘Large changes in fiscal policy: taxes vs. spending’, Tax Policy and the Economy 24: 35–68. doi: 10.1086/649828

- Alesina, A. and Ardagna, S. (2013) ‘The Design of Fiscal Adjustments’, in J.R. Brown (ed.), Tax Policy and the Economy, Vol. 27, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Alesina, A., Ardagna, S., Perotti, R. and Schiantarelli, F. (2002) ‘Fiscal policy profits and investment’, American Economic Review 92: 571–89. doi: 10.1257/00028280260136255

- Alesina, A., Ardagna, S. and Trebbi, F. (2006) ‘Who adjusts and when? On the political economy of stabilizations’, IMF Staff Papers 53: 1–49.

- Alesina, A. and Bayoumi, T. (1996) ‘The costs and benefits of fiscal rules: Evidence from US states’, NBER working paper no. 5614, Cambridge, MA.

- Alesina, A., Broeck, M., Prati, A., Tabellini, G., Obstfeld, M. and Rebelo, S. (1992) ‘Default risk on government debt in OECD countries’, Economic Policy 7(15): 427–63. doi: 10.2307/1344548

- Alesina, A., Carloni, D. and Lecce, G. (2013) ‘The electoral consequences of large fiscal adjustments’, in A. Alesina and F. Giavazzi (eds), Fiscal Policy after the Great Recession, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press and NBER, pp. 531–72.

- Alesina, A., Cohen, G.D. and Roubini, N. (1991) ‘Macroeconomic policy and elections in OECD democracies’, NBER Working Paper No. 3830, Cambridge, MA.

- Alesina, A. and Drazen, A. (1991) ‘Why are stabilizations delayed?’ The American Economic Review 81: 1170–88.

- Alesina, A., Favero, C. and Giavazzi, F. (2015) ‘The output effect of fiscal consolidation plans’, Journal of International Economics 96(s1): s19–s42.

- Alesina, A. and Gatti, R. (1995) ‘Independent central banks: low inflation at no costs?’, American Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 85: 196–200.

- Alesina, A. and Giavazzi, F. (2006) The Future of Europe: Reform or Decline, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Alesina, A. and Grilli, V. (1992) Establishing a Central Bank: Issues in Europe and Lessons from the US, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Alesina, A. and Grilli, V. (1993) ‘On the feasibility of a one-speed or a multi-speed European Monetary Union’, Economics and Politics 5: 145–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0343.1993.tb00072.x

- Alesina, A., Mirrlees, J. and Neumann, M. (1989) ‘Politics and business cycles in industrial democracies’, Economic Policy 4: 57–98. doi: 10.2307/1344464

- Alesina, A. and Perotti, R. (1995a) ‘Fiscal expansions and adjustments in OECD economies’, Economic Policy 21: 207–48.

- Alesina, A. and Perotti, R. (1995b) ‘The political economy of budget deficits’, IMF Staff Papers 42: 1–31. doi: 10.2307/3867338

- Alesina, A. and Perotti, R. (1996a) ‘Fiscal discipline and the budget process’, The American Economic Review 86: 401–7.

- Alesina, A. and Perotti, R. (1996c) ‘Reducing budget deficits’, Swedish Economic Policy Review 3: 113–34.

- Alesina, A. and Perotti, R. (1997a) ‘Fiscal adjustments in OECD countries: composition and macroeconomic effects’, IMF Staff Papers 44: 297–329.

- Alesina, A. and Perotti, R. (1997b) ‘The welfare state and competitiveness’, American Economic Review 87: 921–39.

- Alesina, A. and Perotti, R. (1998) ‘Economic risk and political risk in fiscal unions’, Economic Journal 108: 989–1009. doi: 10.1111/1468-0297.00326

- Alesina, A. and Perotti, R. (1999) ‘Budget deficits and budget institutions’, in J. Poterba and J. von Hagen J. (eds), Fiscal Institutions and Fiscal Performance, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Alesina, A., Perotti, R. and Spolaore, E. (1995) ‘Together or separately? Issues for political and fiscal unions’, European Economic Review, Papers and Proceedings 39: 951–8.

- Alesina, A., Perotti, R. and Tavares, J. (1998) ‘The political economy of fiscal adjustments’, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 29: 197–266. doi: 10.2307/2534672

- Alesina, A., Prati, A. and Tabellini, G. (1990) ‘Public confidence and debt management: a model and a case study of Italy’, in R. Dornbusch and M. Draghi (eds), Public Debt Management: Theory and History, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press and CEPR, pp. 94–124.

- Alesina, A. and Rosenthal, H. (1989) ‘Partisan cycles in Congressional elections and the macroeconomy’, The American Political Science Review 83: 373–98. doi: 10.2307/1962396

- Alesina, A. and Roubini, N. (1992) ‘Political cycles in OECD economies’, The Review of Economic Studies 59: 663–88. doi: 10.2307/2297992

- Alesina, A. and de Rugy, V. (2013) ‘Austerity: the relative effects of tax increases versus spending cuts’, Mercatus Center Working Paper, Washington DC.

- Alesina, A. and Sachs, J. (1988) ‘Political parties and the business cycle in the United States, 1948–1984’, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 20: 63–82. doi: 10.2307/1992667

- Alesina, A. and Summers, L. (1993) ‘Central bank independence and macroeconomic performance: some comparative evidence’, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 25: 151–62. doi: 10.2307/2077833

- Alesina, A. and Tabellini, G. (1989) ‘External debt, capital flight and political risk’, Journal of International Economics 27: 199–220. doi: 10.1016/0022-1996(89)90052-4

- Alesina, A. and Tabellini, G. (1990) ‘A positive theory of fiscal deficits and government debt’, The Review of Economic Studies 57: 403–14. doi: 10.2307/2298021

- Alesina, A. and Tabellini, G. (1992) ‘Positive and normative theories of public debt and inflation in historical perspective’, European Economic Review 36: 337–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-2921(92)90089-F

- Alesina, A. and Wacziarg, R. (1999) ‘Is Europe going too far?’ Journal of Monetary Economics Carnegie-Rochester Conference Volume: 1–42.

- Babb, S.L. (2001) Managing Mexico: Economists from Nationalism to Neoliberalism, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ban, C. (2012) ‘Heinrich von Stackelberg and the diffusion of Ordoliberal economics in Franco's Spain’, History of Economic Ideas 3: 85–105.

- Battente, S. (2000) ‘Nation and state building in Italy: recent historiographical interpretations (1989–1997), I: Unification to Fascism’, Journal of Modern Italian Studies 5: 310–21. doi: 10.1080/1354571X.2000.9728256

- Blyth, M. (2002) Great Transformations: Economic Ideas and Institutional Change in the Twentieth Century, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Blyth, M. (2013) Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Chwieroth, J.M. (2010) Capital Ideas: The IMF and the Rise of Financial Liberalization. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Colander, D. (2005) ‘The making of an economist redux’ The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(1): 175–98. doi: 10.1257/0895330053147976

- Dezalay, Y. and Garth, B.G. (2002) The Internationalization of Palace Wars: Lawyers, Economists, and the Contest to Transform Latin American States, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Dyson, K. and Featherstone, K. (1996) ‘Italy and EMU as a “Vincolo Esterno”:empowering the technocrats, transforming the state’, South European Society and Politics 1(2): 272–99. doi: 10.1080/13608749608539475

- Einaudi, L., Faucci, R. and Marchionatti, R. (2014) Luigi Einaudi: Selected Economic Essays, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Featherstone, K. (2001) ‘The political dynamics of the Vincolo Esterno: the emergence of EMU and the challenge to the European social model’, Queen's Papers on Europeanisation no. 6, Belfast.

- Ferrera, M. and Gualmini, E. (2004) Rescued by Europe? Social and labour market reforms in Italy from Maastricht to Berlusconi, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Forte, F. and Marchionatti, R. (2012) ‘Luigi Einaudi's economics of liberalism’, The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 19: 587–624. doi: 10.1080/09672567.2010.540346

- Fourcade, M. (2006) ‘The construction of a global profession: the transnationalization of economics’, American Journal of Sociology 112: 145–94. doi: 10.1086/502693

- Gualmini, E. and Schmidt, V. (2013) ‘State transformation in Italy and France: technocratic versus political leadership on the road from non-liberalism to neo-liberalism’, in V. Schmidt and M. Thatcher (eds), Resilient Liberalism in Europe's Political Economy, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 346–73.

- Jacobs, A.M. (2011) ‘Process tracing and ideational theories’, Political Methodology Committee on Concepts and Methods Working Paper. Vancouver: University of British Columbia.

- Keck, M. and Sikkink, K. (1998) Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Mahoney, J. (2012) ‘The logic of process tracing tests in the social sciences’, Sociological Methods & Research 41(4): 570–97. doi: 10.1177/0049124112437709

- Markoff, J. and Montecinos, V. (1993) ‘The ubiquitous rise of economists’, Journal of Public Policy 13(01): 37–68. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X00000933

- Masini, F. (2012) ‘Luigi Einaudi and the making of the neoliberal project’, History of Economic Thought and Policy 1(1): 39–59.

- Matthijs, M. and McNamara, K. (2015) ‘The euro crisis’ theory effect: Northern saints, Southern sinners, and the demise of the Eurobond’, Journal of European Integration 37(2): 229–45. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2014.990137

- McNamara, K.R. (1998) The Currency of Ideas: Monetary Politics in the European Union, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Mirowski, P. and Plehwe, D. (2009) ‘Introduction’, in P. Mirowski and D. Plehwe (eds), The Road From Mont Pelerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Mudge, S.L. and Vauchez A. (2012) ‘Building Europe on a weak field: law, economics, and scholarly avatars in transnational politics’, American Journal of Sociology 118(2): 449–92. doi: 10.1086/666382

- Parsons, C. (2006) A Certain Idea of Europe, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Pauly, L.W. (1997) Who Elected the Bankers? Surveillance and Control in the World Economy, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Peck, J. (2010) Constructions of Neoliberal Reason, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Perotti, R. (2011) ‘The “austerity myth”: gain without pain?’, available at http://www.bis.org/events/conf110623/perotti.pdf, accessed 10 August 2015.

- Radaelli, C. (2002) ‘The Italian state and the euro’, in K. Dyson (ed.), The European State and the Euro, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 212–37.

- Rogoff, K. (1985) ‘The Optimal degree of commitment to a monetary target’, Quarterly Journal of Economics 100(4): 1169–90.

- Santagostino, A. (2012) ‘The contribution of the Italian liberal thought to the European Union: Einaudi and his heritage from Leoni to Alesina’, Atlantic Economic Journal 40: 367–84. doi: 10.1007/s11293-012-9336-0

- Schmidt, V.A. and Thatcher, M. (2013) Resilient Liberalism in Europe's Political Economy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Seabrooke, L. and Tsingou, E. (2015) ‘Professional emergence on transnational issues: linked ecologies on demographic change’, Journal of Professions and Organization 2(1): 1–18. doi: 10.1093/jpo/jou006

- Tabellini, G. and Alesina, A. (1990) ‘Voting on the budget deficit’, American Economic Review 80: 37–49.

- Van Appeldoorn, B. (2002) Transnational Capitalism and the Struggle over European Integration, New York and London: Routledge.

- Van Evera, S. (1997) Guide to Methods for Students of Political Science, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Van der Pijl, K.V. (1998) Transnational Classes and International Relations, London and New York: Routledge.