ABSTRACT

Can transgovernmental networks facilitate democratization in third countries? If so, to what extent and under what conditions can they impact states’ behaviour? Earlier works demonstrate that transgovernmental professional networks set by the European Union can shape attitudes of officials towards democracy in third countries. However, it remains unclear whether they change their behaviour, too; nor do we have an understanding of how long these changes last. Using the time-series cross-sectional analysis and focusing on two policy fields, human rights and public administration in the former Soviet republics, this article demonstrates that transgovernmental networks can stimulate improvements in domestic practices in third countries. At the same time, the results hint that their effects are policy-specific and rather short-lived.

Introduction

The European Union (EU) sees its development, prosperity, and stability as largely dependent on the situation in its neighbourhood (European Commission Citation2003). The EU seeks to create a stronger neighbourhood by a few means, i.a., knowledge transfer, sharing best practices, and cooperation for solving common problems (European Commission Citation2003). A prominent theme in the official EU rhetoric is that transgovernmental networks improve sectoral performance and facilitate the adoption of the EU acquis, as well as lead to a broader transformation of the society as a whole (European Commission Citation2016a). The Commission describes such cross-border cooperation as capable of shaping democratic attitudes and behaviour that, in turn, might change the administrative culture of the beneficiary states, contributing to broader democratization (European Commission Citation2016a). However, it is still largely unknown whether, to what extent, and under what conditions transgovernmental cooperation can contribute to the consolidation of democratic change.

The EU’s transgovernmental networks are established to project stability, prosperity and safety in the beneficiary states; they aim at joint problem-solving and transfer of best practices (European Commission Citation2004). Generally speaking, transgovernmental networks are created to pursue cross-border functional cooperation between officials and public servants and are commonly identified as a part of the larger phenomenon of growing cooperation transcending national frontiers (Slaughter Citation2003: 1044). Transgovernmental networks are defined herein as sustained professional interactions across state boundaries limited to public servants related to a specific policy field. They address common problems and share knowledge about successful solutions without any centralized bureaucracy or formal organs of government.

Sector-specific transgovernmental cooperation was demonstrated to facilitate the transfer of technical standards and promote legislative convergence. On the example of technical regulations in Ukraine, it is shown that, although with inconsistencies, such networks have positively affected not only legislation but also actual domestic practices in certain sectors (Langbein and Wolczuk Citation2012). There are also studies that detect the positive effects of networks on democratic attitudes of civil servants suggesting that these might plant a seed of broader democratization (Freyburg Citation2011, Citation2015).

Others, on the contrary, are sceptical regarding the potential of such networks in neighbouring states suggesting that ‘the context of a centralized administrative state is not conducive to forming effective horizontal networks that may promote convergence with the EU’ (Dimitrova and Dragneva Citation2013). Thus, it is uncertain to what extent the findings of earlier studies can be generalized to other policy fields and a broader range of countries. Therefore, the purpose of the present article is to establish whether, to what extent, and under what conditions transgovernmental networks can influence a state’s practices in the corresponding field. Are their effects long-lasting and sector-specific or can they be detected across different fields?

Existing studies on cross-border networks are mainly based on separate or comparative case-studies of individual firms, organizations or policies. Usually, such studies focus on the successful cases, which consequently might be suspected of selection bias and limited generality. Drawing on the earlier studies, the present article aims to expand the scope of the current knowledge by conducting large-N analysis of unique longitudinal data accounting for twelve post-Soviet states over the past quarter of a century. Focusing on the former Soviet republics, a region that has a spatially and temporally variable record of cooperation with the EU, the present article builds upon quasi-experimental research design where the effects of transgovernmental networks are traced across groups of states and time-periods when ‘the treatment’ is applied with different regularity and intensity.

Since the improvement of domestic practices is an intended outcome of cooperation in transgovernmental networks, if such cooperation is capable of inducing positive change, such a change is expected to be observed in directly related policy fields. Two policy fields essential for a functioning liberal democracy are chosen: human rights and public administration.Footnote1 Throughout this article, the focus is on how transgovernmental networks impact the quality of governance and the level of respect for the most basic human rights: the rights to security of a person that are often referred to as physical integrity rights.Footnote2 The variance across policies is introduced to assess cross-policy differences in effects of networks.

The present article contributes to the literature in a number of ways. First, it proposes a systematic assessment of the effect of transgovernmental networks using time-series cross-sectional (TSCS) analysis. Second, it addresses the question of the role that transgovernmental networks can play in democratization outside of the enlargement context. Third, it contributes to the literature by complementing earlier works focused on the effects of networks on democratic attitudes moving one step ahead and assessing networks’ impact on actual democratic practices. Lastly, by addressing the question of the effects of technocratic networks, this study also contributes to external regulatory governance literature, which constitutes another dimension of transgovernmentalism.

In the following pages, I provide an overview of human rights and public administration transgovernmental networks. Then, I introduce the theoretical foundations and hypothesize about the favourable conditions for these to have an effect. The fourth section provides the description of the research design and the data. The subsequent section presents and discusses the results. In the last section, I summarize the main findings.

Transgovernmental networks and European foreign policy

Cross-border cooperation between the EU and the former Soviet republics has been incepted with the establishment of the Technical Assistance to the Commonwealth of Independent States (TACIS), and further developed with the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement. By the mid-2000s the TACIS programme was replaced by the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) for cooperation, i.a., with Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia; meanwhile, the Strategy for a New Partnership was set up for cooperation with the Central Asian republics. Later, cooperation with Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova further evolved to the Association Agreement and the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area. Transgovernmental policy-specific networks became a common feature of these cooperation frameworks since the early 1990s, which, however, significantly developed in the early and mid-2000s with the EU’s enlargement eastwards.

The EU’s transgovernmental networks aim to fulfil a few roles. First, they are meant to address functional and specific cross-border problems, as well as policy challenges, to jointly tackle issues and share experience of effective problem solution (European Commission Citation2004, Citation2016b). Second, such cooperation seeks to reduce the impact of the new ‘dividing lines’ between member and non-member states (European Commission Citation2003). They are, furthermore, meant to bridge sub-regional groups seeking to overcome historical divisions and seek to help states integrate into the EU without necessarily granting them formal membership. Lastly, they are designed to facilitate domestic transition processes and reforms (European Commission Citation2003). Given that often the immediate purpose of such networks is the improvement of specific domestic practices, the challenge is to detect whether they succeed in doing that.

The first focus of this article lies in human rights networks which are covered by the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR), as well as the Joint Programmes (JPs), supported and implemented jointly by the Council of Europe and the EU (Council of Europe Citation2016). Cooperation in the human rights sector builds upon the support for legal and institutional reforms, providing trainings for experts, assistance in reporting, advice and recommendations to governments, and dissemination of best practices. The target audience of such networks consists of human rights-related civil servants. At the same time, the number of cooperation events varies for different regions and time periods.Footnote3

The focus of public administration networks lies in the transfer of best practices from the member states to the beneficiary states. Projects like the European Commission’s Technical Assistance and Information Exchange (TAIEX) and Twinning represent policy-specific cooperation with the public administration sector and form the second focus of the present study. Their main goals are to improve the quality of public services, support the development of their capacity, provide targeted technical assistance in drafting legislation related to the Action Plans, and help them with implementation and enforcement. They host about 30,000 participants from the neighbouring states every year, thus, between 2010 and 2015 alone a quarter of a million public officials provided or received expert advice within TAIEX and Twinning (European Commission Citation2016b). Drawing on a peer-to-peer approach, these programmes function with the support of experts from member states’ public administrations by providing beneficiary states in the neighbourhood with relevant tools to strengthen their administrative capacity and bringing their national legislation in line with the Union acquis (European Commission Citation2006).Footnote4

Twinning and TAIEX introduced a new format of cross-border cooperation, making it more sustainable, coherent, and on a considerably larger scale. They are often seen as the most powerful and effective tools for providing advice and guidance ‘when it comes to EU values, standards and legislation’ (European Commission Citation2016b: 1), and these tools are perceived to ‘rank amongst the most essential instruments, which are available to foster stability, security and prosperity throughout the Neighbourhood and enlargement regions’ (European Commission Citation2016b: 1). Activities within such networks – seminars, workshops, study and expert visits, as well as peer reviews – arguably, facilitate the exchange of best practices and experiences (European Commission Citation2016b). In Ukraine alone, between 2006 and 2014, about 11,000 public authorities had taken part only in TAIEX events (in Moldova about 7,000 officials, in Georgia about 3,000).Footnote5

Annually, the Commission reports numerous success stories of cooperation within such networks. For instance, Twinning cooperation that was set to assist the Georgian national customs and sanitary control system led to better compliance with the EU food-safety standards and increased the efficiency of sanitary services, improving the general quality of products and stimulating trade in goods between Georgia and the EU (European Commission Citation2013). Having learned about individual success stories, we are still unaware of the extent of the impact; neither do we know enough about the duration of positive changes documented in EU reports.

Cooperation within human rights and public administration sectors is not limited to the projects discussed above. Nevertheless, those represent the largest frameworks of transgovernmental cooperation in the related policy fields and comprise, therefore, the focus of the empirical analysis.

Transgovernmental networks: theory and hypotheses

Civil servants constitute the target group of transgovernmental networks. Existing literature and EU reports suggest that such networks can have a profound impact on public servants’ performance. However, why should one expect a successful transfer of practices as a result of such networks? And what is the link between the micro- (individual public servant) and the macro- (state) level? This section discusses why transgovernmental networks’ effects are expected to be observed at the level of state performance. It also proposes three hypotheses that relate to the conditions under which such networks are expected to have more impact. These conditions correspond to the properties of cooperation format, policy-specific characteristics, and properties of the beneficiary states that may define the extent of their susceptibility to the EU rules and norms.

Civil servants play a key role in maintaining the stability of any regime. They are of particular importance at the policy-implementation stage as they are the body entrusted with carrying out regime’s decisions serving as ‘the major point of contact between citizens and the state’ (Peters and Pierre Citation2003: 2). In contrast to the political élite and diplomats, civil servants represent the part of the public sector ‘with which citizens have contact and thus help shape citizens’ perceptions as to how a political system functions’ (Freyburg Citation2011: 1002). It is often up to civil servants to decide ‘how policy should be constructed and how public goods and services should be delivered’ (Ellison Citation2006: 1261). Therefore, they play a crucial role in implementing policies, sustaining the regime, and interpreting the law. They directly influence the operation of a system and are crucial actors for both the stabilization of a regime and the consolidation of institutions (Freyburg Citation2015: 60); and based on the quality of their performance a state’s functioning is evaluated. In such a way, regular and sustained sharing of best practices within networks might directly impact civil servants’ practices, and, therefore, be reflected in states’ performance in the corresponding field. After all, it is not states or regimes as unitary entities that interpret and implement legislation on an everyday basis, but individual public servants.

Building upon the idea of knowledge-sharing in a professional environment and bringing together relevant actors to engage in sustained cooperation, networks are often described as capable of fostering capacity-building and constituting successful instances of external governance (Lavenex Citation2008; Freyburg Citation2011; Lavenex and Schimmelfennig Citation2009). In general, cross-border networks have been recognized as capable of spreading know-how, shaping democratic attitudes, and transferring organizational practices even in non-democratic environments (Freyburg Citation2015; Turkina and Kourtikakis Citation2015). Some also suggest that the inclusion of local actors in transgovernmental networks results in growing support for convergence with the acquis among state officials (Langbein and Wolczuk Citation2012).

Given that existing studies demonstrate that transnational networks can improve the performance of organizations in third countries (Turkina and Kourtikakis Citation2015), it is fair to wonder whether similar processes might also take place in transgovernmental networks.Footnote6 Studies also suggest that attitudes of state officials might change as a result of participation in transgovernmental networks even in authoritarian states, which may plant the seed of democratization (Freyburg Citation2015). Given the findings of earlier studies suggesting that cross-border networks can facilitate institution-building and approximation to the EU legislation, foster capacity-building, and create Europe-wide epistemic communities, a logical next step is to ask whether and under what conditions the impact of transgovernmental networks can be reflected at the state level? When speculating on the conditions that might stimulate a state’s adjustments, I relate them to (a) the properties of the cooperation format, (b) policy-specific characteristics and (c) the beneficiary state’s properties that might define its susceptibility to the EU’s rules and norms.

Previous studies associate the effective transfer of policies and institutions with the intensity of interaction in addition to purely technocratic and non-politicized settings (Checkel Citation2001). The sustainability of cooperation may increase the chances of occurrence of change. In other words, the more regular such cooperation is, the more civil servants can take part in it and potentially be affected by such exchange. Therefore, the first hypothesis relates to cooperation-specific properties of networks. And it is expected that

H1: The more intense transgovernmental cooperation is, the more likely it is to positively influence a state’s subsequent practices in the corresponding field of cooperation.

Studies show that in many neighbouring states with poor governance standards, weak administrative capacity, and prevalent corruption and clientelism, policy change is more likely if it does not negatively influence the interests of the ruling élite (Dimitrova and Dragneva Citation2013). Likewise, policy-specific conditionality does not stimulate policy adjustments unless they fit the preferences of the ruling élite (Ademmer and Börzel Citation2013). Meanwhile, compliance with regime-sensitive human rights standards might involve risks for the élite of losing political power (Schimmelfennig Citation2012: 18). Therefore, it is essential to assess to what extent these policy-related characteristics might determine the odds of the effect of transgovernmental networks.

In contrast to human rights, public administration cooperation is more likely to represent an area of preferential fit since both TAIEX and Twinning are demand-driven cooperation formats, i.e., their topics and location are decided by the beneficiary administration (most often by corresponding ministries and state agencies) (Commission Citation2017), whereas the extent of technical support and the duration of cooperation are decided by the Commission (European Commission Citation2013). Human rights networks, on the contrary, are provided without any prior coordination with the beneficiary administration (e.g., EIDHR Citation2017: 87). Therefore, in contrast to public administration, human rights are more likely to represent a field of a preferential misfit. In other words, it is fair to assume that adjustment costs might generally be lower in the field of public administration than in the field of human rights.

Changes in regime-sensitive issues such as human rights might threaten the status quo for the ruling élite. Human rights-related networks might target sensitive issues since they dwell on the principles of independent judiciary, accountability and checks for domestic institutions. Functioning independently of the political élite, judges and enforcement bodies put constraints on the use of force for political purposes (Dimitrova and Dragneva Citation2013). In this way, adoption of liberal political norms such as human rights, democratic elections and the rule of law constitutes a political risk for non-democratic governments.

Given the ruling élite’s interest in preserving the status quo, strong domestic veto players are more likely to obstruct the implementation of potentially costly ‘innovations’ learned in the networks (Dimitrova and Dragneva Citation2013; Shyrokykh Citation2017). Given the dependence of domestic institutions on the political élite in the region, it is expected that such powerful actors would prioritize the preservation of the status quo, making adjustments difficult where it affects their interests. And it is the preferential misfit associated with the potential costs that makes public administration domain more likely to exhibit the effects of cross-border networks; meanwhile, the human rights sector is less likely to exhibit such adjustments. The cost here is referred to political risks or power loss associated with alteration of the status quo. Hence, it is expected that less improvement will follow an increase in the intensity of networks in the human rights sector; meanwhile, as public administration adjustments do not inflict the same high costs, adjustments are more likely to be detected there. Therefore,

H2: When transgovernmental cooperation requires costly domestic adjustments, it is less likely to positively influence a state’s subsequent practices in the corresponding field of cooperation.

In addition, it is suggested that the EU is more likely to impact third countries if the latter aspire to belong to the ‘European family’ (Schimmelfennig Citation2012: 8; Subotic Citation2011). States that have developed a European political identity, as a broad understanding of a collective self, are more likely to define standards of appropriate behaviour in line with in-group members (Subotic Citation2011). In such circumstances the reference group, its norms and its practices are perceived as legitimate and appropriate.

Over the years, the EU has developed a number of criteria defining the eligibility for becoming a member state, and, even more broadly, it has defined what it means to be a ‘European state’ (Subotic Citation2011). An important part of the latter is the respect for human rights. States which see themselves as European and want to (re-)join Europe are supposed to possess these norms; and to aspire to join the EU, they should perceive the former as a legitimate actor with legitimate rules and practices. Hence, states are more likely to be susceptible to the EU rules if they are convinced of the EU’s legitimacy and the appropriateness of its norms and practices.

Over time, Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine have developed strong European political identities. For these particular states, the EU is not just an economic partner and an aid donor, but also a point of reference for their self-understanding. When a reference group becomes a point of self-definition and esteem, and when an actor wants to be perceived as and become an in-group member, it has to act accordingly and emulate the social behaviour of the in-group members (Finnemore and Sikkink Citation1998).

A greater impact of transgovernmental cooperation in states aspiring to become member states can also be expected from the rational perspective. In fact, although it is difficult to separate the effects of socialization from rational calculation during European integration processes, the literature suggests that cost-benefit calculations usually prevail (Verdun and Chira, Citation2008: 11; Sasse Citation2008: 846). European aspirations themselves might be a result of the expected benefits that integration processes bring. This particular strategy is, in fact, often adopted by the ruling élite in the region under investigation to pursue own strategic interests (Cianciara Citation2016).

Some of the Eastern Partners see their participation in the ENP as a step towards membership (Verdun and Chira, Citation2008). In this context, membership aspirations might be, in particular, strategically used to indicate their intentions to deepen economic integration with the EU thereby bringing benefits to the ruling élite (in terms of voter support and economic benefits).

When European membership aspirations are rationally employed for the sake of economic integration, transgovernmental networks might provide an opportunity to improve the actual standards of different sectors, which might be a condition for further economic integration. This argument primarily concerns public administration networks rather than human rights-related networks since, as the literature demonstrates, in the latter domain reforms are often decoupled from the actual application (Freyburg et al. Citation2009). In the field of public administration, however, the ability to improve, for instance, food safety regulations and the actual sanitary standards might positively impact exports of the related goods to the EU and, hence, benefit the third state and eventually its ruling élite.

Therefore, European membership aspirations, be they an expression of a changed political identity or a result of cost–benefit calculations, may stimulate greater impact of transgovernmental cooperation. And thus it is expected that states that have developed membership aspirations are more likely to be positively affected by transgovernmental cooperation. Hence,

H3: When transgovernmental cooperation targets a state with membership aspirations, it is more likely to positively influence the state’s subsequent practices in the corresponding field of cooperation.

Research design

In order to test the hypotheses specified above, TSCS analysis is applied to a longitudinal dataset. The data consist of country-year observations of 12 states over a more than 20-year period.Footnote7 The states analysed are: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan.

The results presented in this article are obtained with the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis performed on TSCS data. To address characteristics of the data, a fixed-effects model with lagged value of the dependent variable and robust standard errors is used.Footnote8 Given that changes on the independent variable can take time to result in changes on the dependent variable, the model is estimated with a lag of the explanatory variable. In addition, the model also includes a lag of the dependent variable at one additional year to account for the fact that the regularity of networks might be a result of past practices.Footnote9

The analysis includes two dependent variables that are separately used in models. The first one is human rights practices and is captured by the CIRI index (Cingranelli et al. Citation2014), accounting for the level of respect for civil and political rights. The CIRI index is a nine-level index ranging from ‘0’ (no respect) to ‘8’ (full respect). The second dependent variable, i.e., government effectiveness, reflects the perception of the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to such policies. The data are obtained from the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) and range between ‘−2.5’ (weak) to ‘+2.5’ (strong) governance performance (World Bank Citation2016c). Both dependent variables are standardized so that the effects of networks can be compared across models.Footnote10

The analysis includes two independent variables. The intensity of human rights and public administration transgovernmental cooperation variables account for the intensity of interaction in the human rights and public administration fields. They refer to the total annual number of events in each field separately.Footnote11 An ‘event’ refers to any type of professional interaction set and conducted within the studied cooperation frameworks. These include joint projects, expert and assessment missions, workshops, seminars, trainings, study visits, etc. The data on these variables are collected from the reports of the EIDHR and the JPs (for human rights);Footnote12 the data on TAIEX/Twinning events (for public administration) were obtained from the Commission via an email request.Footnote13 These variables are coded as additive indices and account for the total number of events within a given country-year.

Investigating a region that has a heterogeneous record of cooperation with the EU, the present article builds upon quasi-experimental research design where the effects of transgovernmental cooperation are traced across groups of states and time-periods when ‘the treatment’ is applied with different regularity. By quasi-experimental, in this case, it is meant that the research design does not rely on manipulated ‘treatment’ (Shadish et al. Citation2002: 12–17).

The analysis includes a number of control variables that have been detected in earlier studies to have an effect on states’ practices. Two of the strongest predictors of a state’s performance are its level of economic development and strength of democratic institutions. Thus, the models account for the gross domestic product measured in log GDP per capita (in constant 2000 UDS dollars). The data are obtained from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators Online database (World Bank Citation2016a). To account for the strength of democratic institutions, the Polity Score is used (Marshall and Jaggers Citation2014). The scale ranges from ‘−10’ (the most autocratic states) to ‘+10’ (the most democratic states).

Although not being proposed for membership at this stage, Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia at different points in time developed membership aspirations. The variable membership aspiration is coded as a binary variable where ‘0’ indicates no membership aspirations and ‘1’ indicates the presence of such intentions. It accounts for whether or not European integration is the major foreign policy priority of national governments and largely supported by the government and population. This variable is coded in line with earlier studies in such a way that membership aspirations are present in Ukraine after the Orange revolution (from 2004 onwards), in Georgia after the Rose revolution (from 2003 onwards) and in Moldova after the 2005 elections as a result of which a pro-European government has been elected (from 2005 onwards) (coding follows Freyburg et al. Citation2011: 1033).Footnote14

Furthermore, the models also account for the effects of ruling élite change. Such changes can be accompanied by a turbulent domestic situation, which can impact human rights and governance effectiveness. The variable reflects whether, as a result of elections, the ruling élite has been changed; it is binary and for the sake of brevity, the former is called regime change (where ‘0’ indicates no ruling élite change and ‘1’ otherwise). The data are taken from Stykow (Citation2014). Moreover, a variable accounting for the log population size is introduced to avoid the association of states having large populations with lower levels of respect for human rights (due to the fact that the human rights variable is an index rather than a ratio to the country’s population). The measure of population is taken from the World Bank (Citation2016b). Additionally, the models control for the instances of wars since these directly impact human rights practices and government effectiveness of states. The data are taken from the Correlates of War database (Sarkees and Wayman Citation2011) and complemented with data from the Major Episodes of Political Violence database (Marshall Citation2014).

To exclude alternative explanations, the models control for the effects of other potentially effective foreign policy instruments, such as sanctions and threat thereof, as well as financial assistance. The data on sanctions and threat thereof are taken from the Threat and Implementation of Economic Sanctions dataset (Morgan et al. Citation2006) and the Hufbauer, Schott and Elliott sanctions datasets (Hufbauer et al. Citation2007) and complemented from data provided by the Commission (Citation2016c). Financial assistance is operationalized via the net official development assistance. The data are taken from the OECD (Citation2017) Development Assistance Committee’s Creditor Reporting System (CRS).Footnote15 Additionally, a variable accounting for the distance to the closest EU member state is introduced in order to control for the factor that might trigger the assignment of the treatment.Footnote16 The data are calculated using the Google Maps Distance Calculator (Citation2015) and account for the distance between the capitals. Moreover, a count variable that reflects the number of ratified major treaties (related to physical integrity rights) is included to the human rights model.Footnote17 Variables included in the analysis are briefly summarized in the online supplementary material.

Results and discussion

Using the TSCS analysis, a number of results are reported here. The first hypothesis suggesting that the impact of networks increases with their regularity is confirmed (, Models 1 and 2). The size of the effect reflects the average change on the dependent variable with a one-unit increase (a single event) in the independent variable. The results in Models 1 and 2 should be interpreted in terms of standard deviations since the dependent variable has been standardized, whereas Models 1b and 2b report the results using the original format of the data (i.e., non-standardized).

Table 1. Impact of Transgovernmental Networks on States’ Practices.

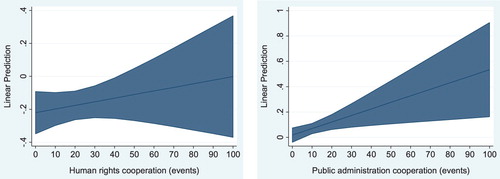

That is, a one-unit increase in the independent variable (one event in human rights networks), on average, is followed by an increase in the dependent variable by 0.003 standard deviations, which corresponds to a 0.004 increase in the original format of CIRI index. For the public administration networks, with a one-unit increase in the independent variable (single public administration network event), on average, one can expect an increase in the dependent variable by 0.005 standard deviations, which corresponds to a 0.002 increase in the original format of government effectiveness index. The results suggest that networks do have a positive impact on domestic practices in both policy fields. However, given the fact that the effect of an individual event is very small, a rather large number of such events is required to have a tangible impact on the level of respect for human rights and the quality of governance.

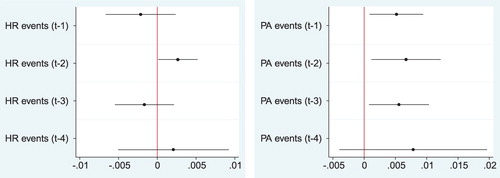

Moreover, when running models with alternative lag structures, it is detected that the duration of the effects of transgovernmental networks differs depending on the policy field. As demonstrated in , the effects of public administration cooperation are detected in models with a lag of one, two, and three years, whereas the effects of human rights networks are detected only in models with a two-year lag, suggesting that it takes a longer period of time for human rights networks to affect the domestic practices and such effects last for a shorter time. Additionally, the size of the effect in the public administration sector is larger (cf. Model 1 and 2), which suggests that policy-related characteristics are crucial for the impact of transgovernmental networks.

Figure 1. Coefficient Plots of Effects of Public Administration (Left) and Human Rights (Right) Cooperation on Corresponding Practices Estimated on Models with Lags of 1–4 Years.

Thus, the positive effects of public administration networks are larger, more long-lasting, and are observed sooner in comparison to the effects of human rights networks. These findings hint that the higher the cost of adjustment is, the smaller will be the effect of transgovernmental networks. Nevertheless, some positive impact can be expected across various policies even when they entail high costs. Hence, technocratic cooperation might contribute to broader democratization, bringing adjustments via the ‘back door’ of professional networks.

Furthermore, comparing the two parts of , fewer public administration events are needed to trigger a positive effect (than their human rights counterparts). These results further support the argument that policy characteristics define the extent to which networks stimulate adjustments, which confirms the second hypothesis.

Figure 2. Predictive Margins Plot with 95% Confidence Interval for Human Rights (Left) and Public Administration Cooperation (Right).

Since public administration networks are designed to directly address requests from the beneficiary administrations, such cooperation is less likely to damage the power-related interests of domestic ruling élite. Human rights networks, on the contrary, are not demand-driven and changes stimulated by such networks are more likely to potentially damage the political élite’s preferences. To understand the precise mechanism behind the policy-related characteristics that facilitate and hinder the transfer of best practices in technocratic networks, future studies should look into this question. Although an interesting subject, identifying the precise mechanisms behind the detected effects is not a purpose of this study, nor was it possible utilizing the present research design.

To further understand the conditions under which networks can yield more impact, I investigate the effects of country-level characteristics that might stimulate susceptibility of beneficiary public servants. It is hypothesized that the presence of membership aspirations can facilitate the absorption of new practices (Hypothesis 3). The results of the analysis, however, suggest that the presence of membership aspirations does not affect networks’ impact (, Models 3 and 4).Footnote18

Earlier works suggest that membership aspirations can determine the success of European acquis transfer and rule adoption (Subotic Citation2011: 311; Ademmer and Börzel Citation2013). However, the present findings do not confirm this claim, instead suggesting that, in the post-Soviet states, the presence of such aspirations does not have a systematic effect on the extent to which new practices are absorbed. This can be explained by the fact that unlike the Balkans, where the effects of membership aspirations have been detected (Subotic Citation2011), the Eastern Partnership states do not have credible membership perspectives to stimulate systematic adjustments of states’ practices.

Conclusions

The present article has systematically explored the potential of the EU’s transgovernmental networks among its post-Soviet neighbours. It has assessed whether transgovernmental professional networks can stimulate the adoption of better practices on the example of public administration and human rights fields. This article has shown that transgovernmental networks do, indeed, positively impact states’ performance.

The present study contributes to the literature on the effects of EU technocratic cooperation with third countries through transgovernmental networks in a few ways. First, it demonstrates that transgovernmental networks can have an impact on the practices of states. The intensity of such cooperation and its policy-related characteristics determine the extent of the networks’ impact. Second, in the context of the currently halted enlargement policy of the EU, this finding has a policy-related value. Namely, not only coercion and conditionality, but also technocratic cooperation can potentially contribute to broader democratization of the neighbouring region. Hence, in countries where direct democratization pressure might meet open resistance, professional networks can serve as an alternative indirect way of stimulating adjustments. Third, in contrast to the earlier studies that focus on detecting the effects of technocratic cooperation in specific policy-areas, the present study provides new insights regarding the effects of the EU on the state level.

At the same time, the present findings should be interpreted rather cautiously in their optimistic assessment of the extent to which external actors can induce change via proliferation of cross-border networks on the present scale. Namely, these effects are shown to be rather small and, in regime-sensitive issues, not long-lasting. Therefore, to be effective, transgovernmental cooperation should build upon large-scale and regular involvement.

The findings also relate to external regulatory governance, which constitutes yet another dimension of transgovernmentalism. While the role of the EU’s regulatory governance is widely acknowledged, the question of to what extent (and under what conditions) these technocratic networks can be impactful has received only little attention. The findings presented herein contribute to the above debate as well.

RJPP_1393837_supplemental_material.zip

Download Zip (102.7 KB)Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Berthold Rittberger, Dovilė Rimkutė, Petra Stykow, Alexander Libman, Maksym Girnyk, Lisa Maria Dellmuth, Frank Schimmelfennig and the participants of Comparative and International Studies research seminar at ETH Zurich for their constructive comments. Moreover, I wish to thank the European Commission for providing me with the data. I am also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Karina Shyrokykh is a post-doctoral fellow at the Graduate School for East and Southeast European Studies, Ludwig-Maximilian University Munich, Germany.

ORCID

Karina Shyrokykh http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1326-6129

Notes

1 Liberal democracy builds upon the institutional and rights dimensions of democracy, where ‘the institutional dimension captures the idea of popular sovereignty and includes notions of accountability, constraint of leaders, representation of citizens and universal participation’ (Landman Citation2013: 28). The rights dimension, on the other hand, ‘is upheld by the rule of law and includes civil, political, property and minority rights’ (Landman Citation2013: 28). Thus, the liberal understanding of democracy intrinsically builds upon a thick definition including ‘legal constraints on the exercise of power to complement the popular elements in the derivation of and accountability for power’ (Landman Citation2013: 28).

2 Physical integrity rights correspond to the most elementary respect of human life and dignity. These rights include freedom from extrajudicial killing, freedom from torture or other cruel and inhumane or degrading treatment, freedom from forced disappearance, and freedom from political imprisonment.

3 For more on spatial and temporal heterogeneity see the online supplementary material.

4 In the region under investigation, TAIEX and Twinning cooperation are available only to Eastern partners and Russia.

5 For comparison, the total number of public servants in Ukraine is 272,000 (UNIAN Citation2013).

6 Transgovernmental networks differ from transnational networks in the sense that the former consist of civil servants and government representatives (Freyburg Citation2015) whereas the latter mostly refer to cross-border networks between non-state actors (Turkina and Kourtikakis Citation2015).

7 The data on human rights practices (CIRI) are available for 1992–2011. The data on government effectiveness (WGI) is available for 1996–2014.

8 The results are checked against alternative models (see the online supplemental material).

9 For detailed discussion of endogeneity see the online supplementary material.

10 Y-standardization, rather than full standardization, is performed because the independent variables in the study are count variables (Greenacre and Primicerio Citation2013). For more see the online supplementary material.

11 The events considered for coding are chosen based on their designated purpose to match the elements of the dependent variables.

12 Coding is performed based on officially reported data (see the online supplementary material).

13 The data can also be obtained from the TAIEX library (Commission Citation2017). Human rights-related TAIEX/Twinning events are dropped from the total number of events.

14 Alternative operationalization of membership aspirations is addressed in the online supplementary material.

15 Financial assistance data includes funding of the human rights and public administration projects. The CRS does not list separately either TAIEX/Twinning or funding for EIDHR/JPs. For a correlation table see the online supplementary material. When removing the financial assistance variable from the regression, the results remain similar to the reported ones.

16 To avoid a potential selection bias, the results are checked against the difference-in-differences method (see the online supplementary material).

17 The following treaties are considered: the Convention against Torture (CAT), the Optional Protocol to CAT, the Convention on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR), the Second Optional Protocol to the CCPR, the Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, and the European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhumane or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. The data are retrieved from OHCHR (Citation2017).

18 Since the membership aspirations variable is time-invariant for some states, the results of Model 3 and 4 are checked against an OLS models with random effects (see the online supplementary material).

References

- Ademmer, E. and Börzel T. (2013) ‘Migration, energy and good governance in the EU’s Eastern neighbourhood’, Europe-Asia Studies 65(4): 581–608. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2013.766038

- Checkel, J.T. (2001) ‘Why comply? social learning and European identity change’, International Organization 55(3): 553–88. doi: 10.1162/00208180152507551

- Cianciara, A.C. (2016) ‘“Europeanization” as a legitimation strategy of political parties: the case of Ukraine and Georgia’, Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 16(3): 391–411. doi: 10.1080/14683857.2016.1201984

- Cingranelli, D.L., Richards, D.L. and Clay, K.C. (2014) The CIRI human rights dataset, available at http://www.humanrightsdata.com

- Council of Europe (2016) Joint Programmes between the Council of Europe and the European Union, available at http://www.jp.coe.int/CEAD/Countries.asp

- Dimitrova, A. and Dragneva, R. (2013) ‘Shaping convergence with the EU in foreign policy and state aid in post-Orange Ukraine: weak external incentives, powerful veto players’, Europe-Asia Studies 65(4): 658–81. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2013.766040

- EIDHR (2017) Evaluation of the European instrument for democracy and human rights, 2014-2020: draft evaluation report, volume 2 annex, available at https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sites/devco/files/draft-eval-eidhr-annexes_en.pdf

- Ellison, B.A. (2006) ‘Bureaucratic politics as agency competition: a comparative perspective’, International Journal of Public Administration 29(13): 1259–83. doi: 10.1080/01900690600928110

- European Commission (2003) ‘Wider Europe—neighbourhood: a new framework for relations with our Eastern and Southern neighbours’, COM(2003) 104 final, 11 March, Brussels.

- European Commission (2004) ‘TAIEX: annual report 2003’, Brussels.

- European Commission (2006) ‘TAIEX 2006 activity report’, Brussels.

- European Commission (2013) ‘Twinning, TAIEX and SIGMA within the ENPI: 2012 activity report’, Brussels.

- European Commission (2016a) ‘PHARE: ex post evaluation’, SWD(2016) 2 final, 19 January, Brussels.

- European Commission (2016b) ‘TAIEX and Twinning: activity report 2015’, Brussels.

- European Commission (2016c) ‘Restrictive measures (sanctions) in force’, 20 April, Brussels.

- European Commission (2017) TAIEX Library, available at https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/TMSWebRestrict/resources/js/app/tmsweb/library/list

- Finnemore, M. and Sikkink, K. (1998) ‘International norm dynamics and political change’, International Organization 52(4): 887–917. doi: 10.1162/002081898550789

- Freyburg, T. (2011) ‘Transgovernmental networks as catalysts for democratic change? EU functional cooperation with Arab authoritarian regimes and socialization of involved state officials into democratic governance’, Democratization 18(4): 1001–25. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2011.584737

- Freyburg, T. (2015) ‘Transgovernmental networks as an apprenticeship in democracy? socialization into democratic governance through cross-national activities’, International Studies Quarterly 59: 59–72. doi: 10.1111/isqu.12141

- Freyburg, T., Lavenex, S., Schimmelfennig, F., Skripka, T. and Wetzel, A. (2009) ‘EU promotion of democratic governance in the Neighbourhood’, Journal of European Public Policy 16(6): 916–34. doi: 10.1080/13501760903088405

- Freyburg, T., Lavenex, S., Schimmelfennig, F., Skripka, T. and Wetzel, A. (2011) ‘Democracy promotion through functional cooperation? The case of the European neighbourhood policy’, Democratization 18(4): 1026–54. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2011.584738

- Google Maps (2015) Distance calculator, available at http://distancecalculator.co.za/

- Greenacre, M. and Primicerio, R. (2013) Multivariate Analysis of Ecological Data, Spain: Fundación BBVA.

- Hufbauer, G., Schott, J. and Elliott, K.A. (2007) Sanctions datasets, available at http://www.iie.com/research/topics/sanctions/sanctions-timeline.cfm

- Landman, T. (2013) Human Rights and Democracy: The Precarious Triumph of Ideals, London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Langbein, J. and Wolczuk, K. (2012) ‘Convergence without membership? The impact of the European Union in the neighbourhood: evidence from Ukraine’, Journal of European Public Policy 19(6): 863–81. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2011.614133

- Lavenex, S. (2008) ‘A governance perspective on the European neighbourhood policy: integration beyond conditionality’, Journal of European Public Policy 15(6): 938–55. doi: 10.1080/13501760802196879

- Lavenex, S. and Schimmelfennig, F. (2009) ‘EU rules beyond EU borders: theorizing external governance in European politics’, Journal of European Public Policy 16(6): 791–812. doi: 10.1080/13501760903087696

- Marshall, M.G. (2014) Global report 2014: world’s major episodes of political violence, available at http://www.systemicpeace.org/warlist/warlist.htm

- Marshall, M.G. and Jaggers, K. (2014) Polity IV project: political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2013, available at http://www.systemicpeace.org/polityproject.html

- Morgan, T.C., Krustev, V. and Bapat, N. (2006) Threat and implementation of economic sanctions dataset, available at http://www.unc.edu/~bapat/TIES.htm

- OECD (2017) Creditor reporting system, available at https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=CRS1

- OHCHR (2017) Status of ratification, available at http://indicators.ohchr.org/

- Peters, B.G. and Pierre, J. (2003) Handbook of Public Administration, London: SAGE Publications.

- Sasse, G. (2008) ‘The politics of EU conditionality: the norm of minority protection during and beyond EU accession’, Journal of European Public Policy 15(6): 842–60. doi: 10.1080/13501760802196580

- Sarkees, M.R. and Wayman, F. (2011) Correlates of war, available at http://cow.dss.ucdavis.edu/data-sets/COW-war

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2012) ‘Europeanization beyond Europe’, Living Reviews in European Governance 7(1): 1–31.

- Shadish, W.R., Cook, T. and Campbell, D. (2002) Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Shyrokykh, K. (2017) ‘Effects and side effects of European Union assistance on the former Soviet republics’, Democratization 24(4): 651–69. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2016.1204539

- Slaughter, A.M. (2003) ‘Global government networks, global information agents, and disaggregated democracy’, Michigan Journal of International Affairs 24: 1041–75.

- Stykow, P. (2014) ‘Elections in authoritarian regimes: the post-Soviet cases’, in A. Croissant, S. Kailitz, P. Koellner and S. Wurster (eds), Comparing Autocracies in the Early Twenty-First Century, London: Routledge, pp. 154–84.

- Subotic, J. (2011) ‘Europe is a state of mind: identity and Europeanization in the Balkans’, International Studies Quarterly 55(2): 309–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2011.00649.x

- Turkina, E. and Kourtikakis, K. (2015) ‘Keeping up with the neighbours: diffusion of norms and practices through networks of employer and employee organizations in the eastern partnership and the Mediterranean’, Journal of Common Market Studies 53(5): 1163–85. doi: 10.1111/jcms.12243

- Verdun, A. and Chira G.E. (2008) ‘From neighbourhood to membership: Moldova’s persuasion strategy towards the EU’, Southeast European and Black Sea Studies 8(4): 431–44. doi: 10.1080/14683850802556418

- UNIAN (2013) ‘In Ukraine there are nearly 300 thousand civil servants’, 27 April, available at https://www.unian.net/society/826976-v-ukraine-pochti-300-tyisyach-gosslujaschih.html

- World Bank (2016a) Worldwide development indicators online: GDP, available at http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD

- World Bank (2016b) Worldwide development indicators online: population, available at http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL

- World Bank (2016c) The worldwide governance indicators (WGI) project, available at http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/index.aspx#home