ABSTRACT

Multiple ways of legitimating policy in a multi-level system of states are now creating cross-level challenges to European Union (EU) policies. At the national level referendums are challenging EU policies by claiming that demands arising from a direct democratic ballot have the highest legitimacy. By contrast, the EU legitimates its policies by means of the legal rationality of the policymaking process established by international treaties and confirmed by the representative credentials of the European Parliament and member state governments endorsing its actions in the European Council. Referendums are no longer held to confirm a national government’s decision to become an EU member state. There has been a paradigm shift since 2005; most votes in countries are holding EU referendums have rejected policies approved by their elected representatives. The EU has successfully responded using strategies that involve legal coercion; instrumental calculations; secondary concessions; and avoidance of the risk of a referendum veto through differential integration. However, the legal legitimation of an EU policy without frustration by national referendums does not ensure policy effectiveness.

National governments and the European Union (EU) have a shared interest in making collective policies to address major political and economic problems that cannot be resolved by the actions of a single state. However, member states and EU institutions do not legitimate their policies in the same way. National governments claim legitimacy for their policies because they are representative democracies. The EU claims legitimacy because its treaties approved by national governments are valid under international law. These different forms of legitimacy create the potential for normative conflict (Bellamy and Weale Citation2015; Schweiger Citation2016). As long as EU policies approved by the multinational European Parliament (EP) and European Council are not challenged domestically, no conflict of legitimacy arises.

Referendums claim the legitimacy of direct democracy, because citizens are able to decide a specific policy issue in place of their elected representatives. All but two EU member states make provisions for direct democratic votes in which citizens can decide what government does or does not do.Footnote1 In the past, ballots relevant to EU affairs were usually about whether a country should join the EU. In the great majority of countries, national electorates have given their once-for-all approval of membership. The rejection of EU association by Norwegian and Swiss referendums has avoided conflicts about legitimacy.Footnote2

With the Single European Act and Maastricht Treaty, a paradigm shift began in the use of national referendums to challenge specific EU policies and treaties for the advancement of European integration (Hayward Citation1996). Since 2005 a majority of national referendums on issues such as the European Constitution, the eurozone and immigration have rejected an EU proposal endorsed by their national parliament and the EU’s multinational institutions. Moreover, there are now demands for referendums on EU issues from opposition parties and social movements in upwards of a dozen states.

The EU’s advancement of integration is legitimated by powers granted by a succession pf treaties approved by national governments representing member states (Moravcsik Citation2002). In the early decades of European integration, élite policymakers used their powers with the ‘permissive consensus’ of their citizens (Lindberg and Scheingold Citation1970). The introduction of direct elections to the EP did not alter this, as most electors did not vote and those who did treated European issues as of second-order importance (Reif and Schmitt Citation1980). Advances in European integration since have made EU policies salient in national politics (Steenbergen and Marks Citation2004: 1ff.) and awakened what van der Eijk and Franklin (Citation2004: 47) have described as ‘the sleeping giant’ of public opinion. Since the 2008 economic crisis, anti-EU parties have become significant competitors for votes in the election of representatives to national parliaments (see, e.g., Hooghe and Marks [Citation2018]; Hutter Grande and Kriesi [Citation2016]; Nielsen and Franklin [Citation2017]; Richardson [Citation2017]).

This paper is innovative in explaining how direct democratic national referendums challenge EU institutions’ making of policies with the legal authority of treaties between states. Secondly, it documents a paradigm shift from national referendums approving EU membership to the rejection of policies advancing European integration. Thirdly, it identifies the repertoire of strategies that the EU employs to avoid national referendums obstructing further European integration.

Comparing sources of policy legitimation

Max Weber (Citation1947) theorized that absolute values (Wertrationalität) were a compelling source of legitimacy and, writing when constitutional monarchies were the European norm, he made legal rationality (Rechtszwang) the chief absolute value in states that were modern but not necessarily democratic. Today, democracy is the absolute value most often cited as the primary basis of legitimate authority (cf. Ferrin and Kriesi Citation2016).

Political systems maintain legitimacy by dynamically linking inputs of political demands to political institutions that process these demands and produce policy outputs (Easton Citation1965: chapters 2, 17–18). The feedback of these outputs then produces inputs of more or of less support. The focus on inputs of popular demands is particularly important for theories of democratic legitimacy. The focus on political institutions is particularly relevant in theories of legal rationality, which emphasize making policies in accord with impersonal rules.

National governments legitimate actions by democratic inputs

Institutions of representative democracy and direct democracy enable citizens to make inputs into the policy process. The former give electors the right to choose who represents them, while referendums give citizens the right to decide what policies are adopted. In every EU member state, citizens periodically elect members of parliament (MPs) to represent them, and some elect a president as well. Every EU member state except Germany and Belgium also makes provision for national referendums (see Morel and Qvortrup Citation2018). As long as direct democratic ballots endorse policies approved by elected representatives, there is no dispute about which institution has the greater claim to legitimacy.

A distinctive feature of representative democracy is that citizens cast their vote for a party or individual competing for votes by offering programmes that package dozens of policies (Comparative Manifesto Project Citation2017; Downs Citation1957; Fisher et al. Citation2018; Schumpeter Citation1952). When policies are made by a coalition government, there is a further aggregation of policy preferences. Individuals are not expected to read, let alone agree with, all the policy positions of the party getting their vote. Individuals may vote for the party that comes closest to their left–right orientation or that appears best able to deal with what they regard as the most important issue. A referendum is doubly distinctive. Instead of a policy being decided by elected representatives, it is decided by a majority of voters. Instead of the ballot offering voters a choice between parties with a mixture of policies, a referendum asks for a decision about a single policy. When a referendum vote is called as the result of a popular initiative, a third distinctive feature is added: the question is not determined by elected representatives but by the organizers of the initiative.

In a free and fair referendum,Footnote3 referendum voters may reject the policy position of their elected representatives. This explains why the demand to hold a referendum is more likely to come from opposition parties or social movements. Even if there is no legal commitment for a referendum vote to be binding, in a system in which democracy is an absolute value it is difficult for MPs to reject a referendum result that directly represents what their voters want. Thus, even though a substantial majority of British elected representatives have favoured remaining in the EU, they are implementing the 2016 referendum vote to leave the EU because they accept that a referendum has greater legitimacy than their own opinions.

An EU referendum offering an uncompromising dichotomous choice about a policy polarizes public opinion. By contrast, a policy prepared by elected representatives tends to reflect compromises needed to gain sufficient support in cabinet and parliament to secure adoption. A bipolar choice differs from public opinion surveys that offer voters a choice of three alternatives; the latter can so divide preferences that there is no majority for any alternative and a centrist position is the preference of the median respondent. Eurobarometer surveys of opinion preferences on EU policies cannot take into account the consequences of an intensive referendum campaign in which anti-EU arguments are prominent (cf. Atikcan Citation2015; Hobolt and de Vries Citation2016).

The referendum requirement of an absolute majority of 50.1 per cent of the vote raises a higher barrier for public approval than the plurality vote required to come first in the election of parliamentary representatives. In European democracies no winning party gets half the vote. The competitive nature of a direct democratic referendum campaign means that many ballots are decided by narrow margins. For example, the Maastricht Treaty won French approval with 51.1 percent of the vote and the British decision to leave the EU was endorsed by 51.9 percent of United Kingdom (UK) voters. Referendum turnout is a third higher on average than that for electing members of the European Parliament (MEPs).

The majority required for referendum approval is lower than the super-majority requirement for approval by the European Council: the very idea of deciding policies by voting goes against the practice of the Council and the EP, which arrive at most decisions without any vote (Hix and Hoyland Citation2011: chapter 6; cf. Lijphart Citation1984). Consensus decisions are negotiated by bargaining among member states and party groups in the EP (cf. Héritier and Lehmkuhl Citation2008). Instead of the outcome dividing participants into winners and losers, the EU process favours compromises in which the great majority of stakeholders achieve a significant number but not all of their goals (Thomson Citation2010).

The structural limitation of theories of national democracy is that they are about policymaking in a closed political system. They assume that parliament or a referendum ballot can make policies independently of external obligations. This is the case as long as the object is solely within the power of the national government, for example, a referendum about election laws. However, a significant number of major policies involve interdependencies between national governments. Outcomes depend not only on what a national government decides but also on what other countries and the EU do (Keohane and Nye Citation2001; Rose Citation2015: chapter 7). For EU member states this is very evident for policies on refugees and migration, trade, interest rates and the foreign exchange value of the euro. In dealing with problems of interdependence, all national democracies are bounded democracies.

The EU: policies legitimated by institutional procedures not outputs

An EU policy is legitimate if the subject matter and procedures followed by EU institutions are in accord with treaties. Politically salient issues are collectively decided by national politicians sitting with their counterparts from 27 other member states. EU treaties set out the rules for policies being made by the co-decision of the Council of Ministers and the EP. The multinational membership of the Council consists of elected representatives of member states. Their decisions are arrived at by a process of deliberation and bargaining (Lewis Citation2012; Smeets Citation2015). The great majority of policies are not politically salient because they are technical in nature and limited in impact. Approval is delegated to national civil servants in COREPER, the Committee of Permanent Representatives of member states.

In EU institutions, national politicians represent the whole of their country’s population, but within their national political system they represent a plurality of the electorate and in a coalition government a fraction of a plurality. The Prime Minister of Spain represents a party that won only 29 per cent of its national vote, and Denmark’s only 26 per cent. This creates a Goldoni (Citation1745) problem, the need to serve two masters, one European and the other domestic. In the former role, prime ministers are subject to the Council norm of making policies on behalf of European citizens who are not part of their national electorate. The median prime minister is from a country with less than 2 per cent of the EU’s population. However, once back in their national capital, prime ministers are accountable to their fellow citizens for decisions taken in Brussels and vulnerable to attack if a decision agreed at the EU level is unpopular with their national electorate.

The principal means by which EU citizens can input their preferences into the EU policymaking process is through voting for national party candidates to sit as members of the multinational EP. The very unequal distribution of population among member states has resulted in EP seats being assigned to national constituencies in violation of the democratic principle of one person, one vote, one value. Seats are allocated by the principle of degressive proportionality, a euphemism for disproportional representation. Citizens in 22 seats are overrepresented, often by margins of 50 per cent or more (Rose Citation2015: 102ff.). Eurosceptic parties in the EP have little effect, because collectively they hold fewer than a third of its seats. Moreover, their anti-EU commitment means that their views are not wanted by the dominant pro-integration majority of MEPs.

The Treaty on the European Union states that ‘decisions shall be taken as openly and as closely as possible to the citizen’ (Article 10.3). However, the multinational character of the EP compels MEPs to spend most of their time working with foreigners in a foreign language in a country distant from the voters they nominally represent (Ringe Citation2010). The median MEP is elected on a party ticket that returns two MEPs to the EP, which has representatives of more than 200 national parties. MEPs are organized in multinational party groups with members from two dozen or more member states and up to 40 parties. There is no requirement for group members to have the same policy preferences; empirical analysis emphasizes that the internal policy cohesion of groups is limited (Rose and Borz Citation2013a; Stevenson and Rose Citation2016). For MEPs to be part of the absolute majority needed for the EP to approve a policy, they must be part of a coalition of People’s Party and Socialist Groups that includes representatives of more than 60 national parties (Corbett et al. Citation2016).

The European Citizens’ Initiative falls short of direct democracy in national member states (cf. Morel and Qvortrup Citation2018; Setala and Schiller Citation2012). While it offers the opportunity for a multinational petition to be presented to the European Commission, the subject matter is limited and the Commission has no power to act on a petition, nor does the Council or the EP have to do so. Insulation from the EU’s policymaking process reflects the view of EU policymakers voiced by Commission President José Manuel Barroso: allowing citizens to vote directly on major policies would ‘undermine the Europe we are trying to build by simplifying important and complex subjects’ (quoted in Hobolt Citation2009: 23). Europe’s citizens take a different view: 63 per cent think an EU treaty should require approval by a referendum vote (Rose and Borz Citation2013b: 623).

Intergovernmental theorists such as Moravcsik (Citation2002) argue that the EU can claim democratic legitimation because its policy outputs are formulated in response to demands made and dealt with by bargaining among democratic member states. Lord (Citation2017) argues that, by comparison with the democratic deficits of the United Nations and the International Monetary Fund, the EU appears to be democratic.

However, when political scientists assess the EU by the standards of national democracies, it is judged to have a deficit in democratic inputs (cf. Eriksen and Fossum Citation2012; Kröger and Friedrich Citation2012; Weale Citation2006). Applying democratic rather than legal criteria to evaluate how EU institutions process policy demands, Schmidt (Citation2012) concludes that it also lacks legitimacy in managing the throughput of demands. The German Federal Court has similarly declared that, since the legal authority of EU policymaking does not fully meet the democratic standards of the German Grundgesetz, if an EU policy be inconsistent with these standards the German government should not comply with the EU measure (cited by Piris [Citation2010: 142f.]).

Accepting the EU’s lack of input legitimacy, Scharpf (Citation1999) applies rational choice logic to postulate that EU institutions may achieve legitimacy through effective policy outputs such as a booming economy; it can also lose legitimacy if its outputs have a negative effect. The assessment of effectiveness is relative; it depends on expectations. European institutions have claimed output legitimacy because of their association with peace and prosperity in Europe in the decade and a half following the Treaty of Rome in 1957.Footnote4 Before the economic crisis of 2008, expectations of prosperity in eurozone countries were high. However, the ineffectiveness of EU policies to promote growth and full employment since then has led to eurozone policies being challenged for their lack of democratic legitimacy as well as their ineffectiveness (cf. Bellamy and Weale Citation2015; Scharpf Citation2009). The ineffectiveness of EU policies intended to deal with an unexpected surge in immigration has stimulated an anti-EU backlash at the national level (Cramme and Hobolt Citation2015; Hobolt and Tilley Citation2016; Hutter Grande and Kriesi Citation2016; Mudde Citation2016; Otjes and Katsanidou Citation2017).

From voting for membership to voting against policies

The power to call a referendum is a subsidiary power in the hands of member states. Since 1972 two dozen national governments have held referendums on EU issues. In Ireland and Denmark, laws require referendums to be held on a variety of EU actions that affect the national constitution or governance. Thus, Ireland has held nine referendums on EU issues and Denmark eight. Although not a member state, Switzerland has held nine ballots on its relations with the EU, including three initiated by citizens.

Most referendums on EU issues have been called as a matter of political choice (cf. Mendez et al. Citation2014: chapter 3). There can be multiparty agreement that calling a referendum is appropriate because joining the EU is of such major national significance that it is desirable to add the legitimacy of direct democracy to that conferred by parliamentary representatives (Closa Citation2007). Partisan calculations can encourage the government of the day to use a referendum to boost its popular support or to minimize the negative consequences of government members being badly divided on an EU issue. Partisan calculations can also motivate opposition parties to demand a referendum on a nationally unpopular policy to which the government is committed by its EU membership and use its strategic vote share to get a governing party to call a referendum, as happened in the UK.

Voters rather than their representatives decide EU membership

In the 1970s a shift began from EU decisions being approved solely by national representatives to concurrent approval by a direct democratic vote. In 1972 three states held referendums to decide whether to join the EU, and six countries had held national referendums on EU matters before the first popular election of MEPs in 1979.

The prior endorsement of EU membership by a country’s elected representatives implies that a direct democratic vote should be favourable too. This was the case in 16 of the 19 countries in which membership ballots have been held. In the 1975 UK ballot there was two-thirds approval of membership in what was then the European Economic Community. Norway twice rejected the recommendation of its elected representatives to join the EU and a majority of Swiss voters have rejected membership in the European Economic Area. In referendums in post-Communist countries large majorities endorsed a return to Europe.

Referendums on membership tend to enhance the legitimacy of the EU rather than challenge it, for the outcome binds those who oppose membership to give their consent to a verdict that is regarded as politically final (cf. Anderson et al. Citation2005). Moreover, the rejection of membership by Norwegian, Swiss and now British voters tends to strengthen EU legitimacy, since it frees EU decision-makers from being constrained by national governments not in favour of furthering European integration.

By the 1980s there was a consensus among member states that European institutions needed to expand their economic powers. Doing so involved the adoption of new treaties requiring the unanimous approval of all member states. The initial treaty expanding EU powers, the Single European Act, was approved by member states without a referendum, except in Denmark and Ireland, where ballots were legally required. The first popular challenge to an EU policy came with the Treaty of Maastricht. It was rejected in a ‘think again’ Danish referendum in 1992 and then approved in a second referendum the following year. The Maastricht Treaty won only narrow approval in France. The Treaty of Amsterdam was approved in mandatory referendums in legally required ballots in Denmark and Ireland. However, the Irish government had to hold a second referendum on the Nice Treaty in 2002 to reverse the popular rejection in the first ballot.

A big paradigm shift occurred with the first referendum veto of an EU treaty in 2005. A high-level multinational convention representing élites nominated by national governments, parliaments and EU institutions prepared a draft Constitution for Europe (see Castiglione et al. Citation2007). It dismissed out of hand a proposal to strengthen the proposed Constitution’s legitimacy by putting it to Europe’s citizens for referendum approval. However, eight member states thought it appropriate to do so and a referendum was legally required in Denmark and Ireland. The first referendum, held in Spain, produced the expected big majority for the Constitution. However, 55 per cent of French voters and 62 per cent of Dutch rejected the Constitution, making it a dead letter.

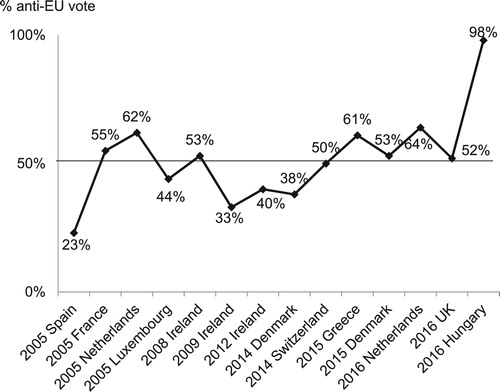

Since 2005 a total of 14 national referendums have been held on EU policies (for case studies, see Mendez and Mendez [Citation2017: 89–205]). By the minimalist standard of democratic elections – competing sides each have the possibility of winning (Przeworski Citation1999) – the referendums have been democratic. The anti-EU side has won nine referendums and the EU has been on the winning side five times (). Even when it has been on the losing side, the anti-EU vote has usually been larger than the vote for the country’s governing party. Referendum results cannot be dismissed as unrepresentative because of low turnout. The mean turnout since 2005 has been 58.9 per cent, a higher figure than that for EP elections but lower than the average turnout at national parliamentary elections. Consistent with the assumption that anti-EU electors hold their views more strongly than EU supporters, turnout averaged 60.2 per cent in referendums in which a majority rejected an EU policy, compared with 56.3 per cent in ballots in which the EU policy was endorsed.Footnote5

A single-issue referendum gives supporters of a party that represents most but not all their views the opportunity to register their disagreement with one of its specific policies. Because anti-EU parliamentary parties do not have the support of an absolute majority of the electorate, to win a referendum anti-EU campaigners must combine a large majority of supporters of anti-EU parties with a significant minority of those who vote for pro-EU parties at parliamentary elections. In every referendum the anti-EU vote has been larger than the vote for anti-EU parties in the election of representatives to their national parliament. For example, the determining factor in the 2016 Brexit referendum was not support from United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) voters, only 12.5 per cent of those who voted at the previous year’s British parliamentary election. It was the division within the governing Conservative Party. While a majority of Conservative MPs and cabinet ministers voted to remain in the EU, a majority of Conservative voters endorsed leaving (http://lordashcroftpolls.com/2016/06).

Each national referendum creates the possibility of conflict between a direct democratic vote and a policy having the legal authority of the EU. If this happens it confronts the national prime minister with a choice of which master to serve: European institutions in which he or she has endorsed the policy that the national ballot rejects, or a majority of the nation’s electorate. In 11 of the 14 referendums since 2005 the national prime minister has supported the EU policy – but often unsuccessfully.

The most frequent outcome is that a majority rejects the position of their elected national representatives and the EU (). Even though French and Dutch governments were represented in drafting the European Constitution, when their citizens could register their views majorities rejected the treaty. Irish voters did likewise in the first of two referendums on the Lisbon Treaty. In Switzerland an anti-EU initiative gave a majority of Swiss voters the chance to demand a change in the government’s policy on the free movement of workers. Majorities likewise rejected minor EU agreements on justice and home affairs policies accepted by the Danish government and an EU–Ukraine association agreement approved by the Dutch Parliament. Notwithstanding intra-party divisions, Prime Minister David Cameron campaigned for the UK to remain in the EU; when the vote went the other way, he resigned the next morning.

Table 1. Most national referendums challenge the EU.

There was a clear conflict between national and EU positions in Greece and Hungary, as referendum majorities backed their national government in challenging major EU policies. The Hungarian government failed to prevent the EU’s Justice and Home Affairs Council from adopting a policy of relocating some refugees to the country and the European Court of Justice rejected its plea to void the Council’s policy. However, when Prime Minister Viktor Orban called a national referendum opposing the EU refugee policy, it gained an overwhelming majority. Organized abstentions by political opponents were sufficient to reduce the turnout below the threshold required to make the referendum legally binding, but the Hungarian government regards it as politically legitimating. Admission to the eurozone was conditional on the Greek government observing its financial regulations, but politicians did not do so. When EU institutions sought to enforce financial conditions on Greek public finance, the Greek government called a national referendum to gain popular legitimation for its resistance to the eurozone’s exercise of its legal authority.

Two of the direct democratic votes legitimating decisions taken by the EU and elected national referendums were on major issues. In the ‘think again’ second referendum on the Lisbon Treaty, a majority of Irish voters endorsed it, thus reversing their earlier veto. The 2012 Irish referendum on the European Fiscal Pact did not require a ‘think again’ vote; it was approved in the first ballot. A minor augmentation in EU powers, the creation of a Unified Court, was approved in a Danish referendum. The approvals given to the European Constitution by Spanish and Luxembourg voters were hollow victories, since rejection in French and Dutch referendums meant the Constitution failed to gain the required unanimous support.

Referendum majorities rejecting policies endorsed by elected national representatives suggest that voters in direct democracy elections are questioning not only the legitimate authority of EU institutions but also the claim of their nationally elected representatives to represent them. Pan-European surveys find substantial distrust of institutions of representative democracy at both the national and European levels. A plurality of citizens, 46 per cent, tend to distrust the EP and a larger majority, 65 per cent, tend to distrust their national parliament (Eurobarometer Citation2016: 20ff., 31ff.).

The EU: a portfolio of strategies

Politics unites what treaties divide

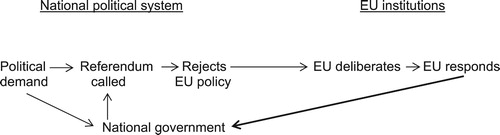

A referendum that rejects an EU policy becomes an input into multinational EU institutions. These institutions have powers and constraints dictated by laws not votes; they are also subject to political pressures from the 27 member states where a referendum has not been held. The EU’s strategic response then feeds back into the country rejecting its policy. The policy outcome is not decided by a national referendum but by the dynamic interaction between what the EU chooses to do and what is done by a government accountable to a national electorate ().

Although the EU is debarred by its rules from participating in a national referendum, the EU cannot ignore a national event that threatens a policy advancing European integration. Whereas a direct democracy majority may have a binding political effect on a national government, by definition it cannot claim to represent European citizens. In national referendums on EU issues, an average of 10 per cent of the EU’s population has been eligible to vote; an Irish ballot involves only 1 per cent of the EU’s population (Rose Citation2015: Figure 5.1). Nor does a single nation’s referendum change the multinational membership of the European Council and the EP which approved the challenged policy. Equally important, the problem that the policy addresses is still in place.

The EU has a portfolio of strategies that it can legitimately call upon, singly or in combination, to defend and advance challenged policies. These include invoking legal powers contained in treaties that all member states have accepted; reinforcing its legal powers by invoking the instrumental cost of refusing to accept an EU policy; making secondary concessions that do not undermine the major points of contested policies; and avoiding the risk of a referendum veto by formulating policies that do not require unanimous approval by all member states. The choice of a strategy is a political judgment in the hands of EU institutions and coordinated with many national governments in the European Council ().

Table 2. EU strategies for countering referendum threats.

EU treaties confer unilateral powers that can be used to exert legal coercion, confronting a national government with unwanted consequences of implementing a referendum result (Streeck and Elsässer Citation2016). In response to the Swiss initiative limiting the migration of EU workers, the EU ruled that implementing this policy would abrogate multiple agreements between Switzerland and the EU that the Swiss government wanted to keep. The Swiss government, which had not supported the initiative, agreed to dilute its effect so the EU would not use its legal authority to invalidate agreements that it wanted to keep. In January, 2018 the Swiss People's Party began initiating a referendum on immigration that would effectively annul many existing agreements with the EU about the free movement of people.

There is no conflict of legitimacies in the case of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU. It is legally legitimate under Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty and democratically legitimated by the British referendum vote. However, the British government is learning that the claim of Brexit campaigners that leaving the EU would enable it to take back control of British policies is a misleading half-truth (cf. Hannan Citation2016). Article 50 gives the EU the authority to determine the agenda for negotiating withdrawal and subsequent EU–UK relations. The UK would like to negotiate major exceptions to existing EU policies vis-à-vis non-member states but the EU regards these policies as non-negotiable (Grant Citation2017). This leaves the British government a choice between making concessions to secure an agreement acceptable to the EU but challenged by pro-Brexit MPs as a violation of a direct democratoc mandate or leaving the EU abruptly without any deal in place by the Article 50 deadline of March 2019 (Shipman Citation2017).

The EU can invoke both legal and instrumental coercion to prevent a national government using a referendum to undermine EU authority. This was done in response to the Greek government’s calling and winning a referendum justifying resistance to EU austerity policies accompanying financial assistance to prevent an immediate collapse of the Greek economy. Notwithstanding the absolute legitimacy of its referendum mandate, after comparing the instrumental value of accepting EU conditions with the consequence of refusing EU terms, the Greek government accepted EU conditions. Instrumental arguments were also used within the EU to justify the indefinite funding of Greece in order to prevent the collapse of the eurozone or even of European integration.

The Irish referendum on joining the European Fiscal Pact likewise combined instrumental and legal coercion. The Irish government was compelled by its national constitution to call a referendum on accepting a Pact that would give legal authority to the EU’s indefinitely imposing austerity on the Irish political economy. Although the Irish electorate had twice before rejected EU treaties, because of Ireland’s need for external financial support there was a strong instrumental argument for accepting the Pact. The alternative was the likely loss of external financial confidence in a vulnerable Irish economy. In these circumstances there was no need for a ‘think again’ referendum. The instrumental cost of losing European financial support was viewed as so great that three-fifths of Irish voters endorsed the Pact the first time around.

Legitimacies are most in conflict when a government explicitly refuses to give its consent to a legitimately adopted EU policy and calls a direct democratic referendum to legitimate its opposition. This has been the strategy of the Hungarian government in response to an EU immigration policy prescribing that Hungary takes a quota of refugees. The EU has no administrative capacity to implement this policy or to look after refugees once they’re in a country; this is the responsibility of the Hungarian government. It does have the legal authority to invoke sanctions against Hungary – provided that there is no opposition from other member states that are quietly not implementing this EU policy. For the time being, the EU is following a ‘kick the can down the road’ strategy of conflict avoidance because of a fear that escalating the conflict about legitimacies could make the situation worse.

When an EU policy requires unanimous approval by all member states, it can make secondary concessions that remove clauses that do not cripple a policy’s primary features and remove the threat of rejection by a national referendum. Concessions can be made through standard EU processes of bargaining. If anticipatory concessions are successful, the EU wins a victory without a referendum. The textbook example of this strategy was the EU response to the rejection of the European Constitution. In cooperation with pro-EU national governments, policymakers sought to depoliticize the substance of the treaty by removing symbols and modifying clauses most likely to provoke national referendums (Castiglione et al. Citation2007; Oppermann Citation2013; Piris Citation2010: 49ff.). For example, the treaty framers modified 11 clauses so that the Danish Ministry of Justice could rule that Denmark was not constitutionally required to hold a referendum.

The secondary-concessions strategy succeeded. Nine of the ten governments that had planned to call referendums on the Constitution did not do so for its effective replacement, the Lisbon Treaty. The UK’s Conservative opposition called unsuccessfully for a referendum. However, on gaining office in 2010 David Cameron accepted the Lisbon Treaty, as the only alternative available under EU law was to withdraw from the EU, a policy for which he had no electoral mandate or support in a coalition government. The acceptance of this acquis stimulated Conservative Eurosceptics to campaign for a referendum on whether the UK should leave the EU (Shipman Citation2016). Cameron conceded a referendum that he wrongly assumed would confirm the UK remaining in the EU.

No form of secondary concession on the Lisbon Treaty could prevent a constitutionally required referendum being held in Ireland. The anticipatory concessions offered were insufficient; a majority of Irish voters rejected the Lisbon Treaty in the first ballot. Defeat enabled the Irish government to get concessions previously denied it but of secondary importance for the EU. These included guarantees that the treaty would not reduce the number of EU commissioners, challenge Ireland’s abortion laws or affect its military neutrality. In a ‘think again’ referendum, an Irish majority endorsed the Lisbon Treaty.

An unexpected Dutch initiative on an EU association agreement with the Ukraine led to its rejection, but turnout was only 32 per cent. In response to the Dutch vote, the EU made a secondary concession by formally incorporating into the text its previously issued interpretative notes on the significance of the agreement. Since the issue had little political salience in the Netherlands, the Dutch government readily accepted this concession.

Differentiated integration gives the EU a legally legitimate means of referendum avoidance to advance a European integration policy without the need for unanimity or a qualified majority. As long as nine member states agree to form a coalition of the willing, Article 20 of the Treaty of the European Union endorses what it describes as ‘enhanced cooperation’ and this strategy is used not infrequently (Leuffen et al. Citation2012).Footnote6 Governments that do not like a policy can exclude themselves from it, but not veto others cooperating. For example, this procedure was used to avoid a British referendum veto of a treaty authorizing more economic integration to deal with effects of the 2008 economic crisis. With the support of European Commission and Central Bank staff, member states agreed enhanced cooperation through an intergovernmental Treaty on Economic Stability, Coordination and Governance (Piris Citation2012: 97ff., 113ff.; cf. Bellamy and Weale Citation2015). To come into effect, it required approval by only 11 states; it now has been accepted by 26 European states. The UK and the Czech governments have avoided the obligations of the Stability Pact and the EU has avoided its veto by a UK referendum.

Up to a point, this portfolio of strategies has enabled the EU to continue adopting integration policies. However, doing so does not ensure the effectiveness of a challenged policy. When a policy is instrumentally ineffective in achieving popular goals, as has been the case in the eurozone, this creates a conflict between democratically expressed demands of national electorates and the absolute value of the EU’s legal legitimacy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Richard Rose is a Visiting Fellow in the European Governance and Politics Programme at the European University Institute and founder/director of the Centre for the Study of Public Policy in Scotland.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Since 1972 a total of 22 EU member states have held referendums on EU affairs (Mendez et al. Citation2014: Table 1.1).

2. In this article the term ‘referendum’ includes both binding and advisory votes, and ballots called by government institutions or by a popular initiative. For varieties of referendums, see Morel and Qvortrup (Citation2018).

3. The term ‘plebiscite’ is not used in this article because it is often applied pejoratively to describe a referendum in which an undemocratic government sets a biased question and conducts an unfair campaign leading to a predetermined result (see Uleri Citation2000).

4. However, correlation is not the same as causation. The military security of Europe was established by the creation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) under American leadership in 1949. By the time the Treaty of Rome was signed, European economies had been reconstructed from the ravages of war with the assistance of funds provided by the Marshall Plan and distributed from 1948 onwards by the newly created intergovernmental Organization for European Economic Cooperation.

5. These calculations exclude Luxembourg, where voting is compulsory and the referendum vote was held the same day as the national election, and Hungary, where pro-EU voters registered their opposition by abstention.

6. This term is used to avoid the implications of differentiating member states into insiders and outsiders.

References

- Anderson, C. et al. (2005) Losers’ Consent: Elections and Democratic Legitimacy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Atikcan, E.O. (2015) Framing the European Union, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bellamy, R. and Weale, A. (2015) ‘Political legitimacy and European monetary union: contracts, constitutionalism and the normative logic of two-level games’, Journal of European Public Policy, 22(2): 257–74. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2014.995118

- Castiglione, D., Schoenlau, J., Longman, C., Lombardo, E., Borragan, N. and Aziz, M. (2007) Constitutional Politics in the European Union, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Closa, C. (2007) ‘Why convene referendums? explaining choices in EU constitutional politics’, Journal of European Public Policy, 14(8): 1311–32. doi: 10.1080/13501760701656478

- Comparative Manifesto Project (2017) available at https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu.

- Corbett, R., Jacobs, F. and Neville, D. (eds) (2016) The European Parliament, London: John Harper Books, 9th edition.

- Cramme, O. and Hobolt, S. (eds) (2015) Democratic Politics in a European Union Under Stress, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Downs, A. (1957) An Economic Theory of Democracy, New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Easton, D. (1965) A Systems Analysis of Political Life, New York: John Wiley.

- van der Eijk, C. and Franklin, M. (2004) ‘Potential for contestation on European matters at national elections in Europe’, in G. Marks and M. Steenbergen (eds), European Integration and Political Conflict, New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 32–50.

- Eriksen, E. and Fossum, J. (eds) (2012) Rethinking Democracy and the European Union, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Eurobarometer (2016) Major Changes in European Public Opinion, Brussels: European Parliament Research Service, PE 596847.

- Ferrin, M. and Kriesi, H. (eds) (2016) How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fisher, J. et al. (eds) (2018) The Routledge Handbook of Elections, Voting Behaviour and Public Opinion, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Goldoni, C. (1745) Il servitore di due padroni, Venzie: Antonio Zatta e figli.

- Grant, C. (2017) ‘In the Brexit talks, Europe holds all the cards’, Financial Times, 2 December.

- Hannan, D. (2016) What Next? London: Head of Zeus.

- Hayward, J. (ed.) (1996) Elitism, Populism and European Politics, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Héritier, A. and Lehmkuhl, D. (2008) ‘The shadow of hierarchy and new modes of governance’, Journal of Public Policy, 28(1): 1–17.

- Hix, S. and Hoyland, B. (2011) The Political System of the European Union, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hobolt, S. (2009) Europe in Question: Referendums on European Integration, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hobolt, S. and de Vries, C. (2016) ‘Public support for European integration’, Annual Review of Political Science, 19: 413–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-042214-044157

- Hobolt, S. and Tilley, J. (2016) ‘Fleeing the centre: the rise of challenger parties in the aftermath of the euro crisis’, West European Politics, 39(5): 971–91. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2016.1181871

- Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2018) ‘Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: lipset, rokkan and the transnational cleavage’, Journal of European Public Policy, 25(1): 109–135. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279

- Hutter, S., Grande, E. and Kriesi, H. (eds) (2016) Politicising Europe: Mass Politics and Integration, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Keohane, R. and Nye, J. (2001) Power and Interdependence, New York: Longman, 3rd edition.

- Kröger, S. and Friedrich, D. (eds) (2012) The Challenge of Democratic Representation in the European Union, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Leuffen, D., Rittberger, B. and Schimmelfennig, F. (2012) Differentiated Integration, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lewis, J. (2012) ‘Council of ministers and European council’, in Erik Jones et al. (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the European Union, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 321–35.

- Lijphart, A. (1984) Democracies: Patterns of Majoritarian and Consensus Government in Twenty-One Countries, New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Lindberg, L. and Scheingold, S.A. (1970) Europe's Would-Be Polity, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Lord, C. (2017) ‘An indirect legitimacy argument for a directly elected European parliament’, European Journal of Political Research, 56(3): 512–28. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12204

- Mendez, F. and Mendez, M. (2017) Referendums on EU Matters, Brussels: European Parliament Study Directorate-General Internal Affairs Policy Department C.

- Mendez, F., Mendez, M. and Triga, V. (2014) Referendums and the European Union, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Moravcsik, A. (2002) ‘Reassessing legitimacy in the European Union’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 40(4): 603–24. doi: 10.1111/1468-5965.00390

- Morel, L. and Qvortrup, M. (eds) (2018) The Routledge Handbook to Referendums and Direct Democracy, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Mudde, C. (ed.) (2016) The Populist Radical Right: A Reader, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Nielsen, J. and Franklin, M. (eds) (2017) The Eurosceptic 2014 European Parliament Elections, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Oppermann, K. (2013) ‘The politics of avoiding referendums on the treaty of Lisbon’, Journal of European Integration, 35(1): 73–89. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2012.671309

- Otjes, S. and Katsanidou, A. (2017) ‘Beyond Kriesiland: EU integration as a super issue after the Eurocrisis’, European Journal of Political Research, 56(2): 301–19. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12177

- Piris, J.-C. (2010) The Lisbon Treaty: A Legal and Political Analysis, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Piris, J.-C. (2012) The Future of Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Przeworski, Adam (1999) ‘A minimalist conception of democracy: a defence’, in I. Shapiro and C. Hacker-Cordon (eds), Democracy’s Value, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 23–55.

- Reif, K. and Schmitt, H. (1980) ‘Nine second-order national elections - a conceptual framework for the analysis of european election results’, European Journal of Political Research, 8(1): 3–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00737.x

- Richardson, J. (2017) ‘Brexit: the EU policy-making state hits the populist buffers’, Political Quarterly, doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12453

- Ringe, N. (2010) Who Decides, and How? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rose, R. (2015) Representing Europeans: A Pragmatic Approach, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2nd edition.

- Rose, R. and Borz, G. (2013a) ‘Aggregation and representation in European parliament party groups’, West European Politics, 36(3): 474–97. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2012.753706

- Rose, R. and Borz, G. (2013b) ‘What determines demand for european union referendums?’, Journal of European Integration, 35(5): 619–33. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2013.799938

- Scharpf, F. (1999) Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Scharpf, F. (2009) ‘Legitimacy in the multilevel European polity’, European Political Science Review, 1(2): 173–204. doi: 10.1017/S1755773909000204

- Schmidt, V. (2012) ‘Democracy and legitimacy in the European Union’, in E. Jones et al. (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the European Union, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 661–75.

- Schumpeter, J. (1952) Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, London: Allen and Unwin, 4th edition.

- Schweiger, C. (2016) Exploring the EU’s Legitimacy Crisis, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Setala, M. and Schiller, T. (2012) Citizens’ Initiatives in Europe, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shipman, T. (2016) All Out War: The Full Story of Brexit, London: William Collins.

- Shipman, T. (2017) Fall Out: A Year of Political Mayhem, London: William Collins.

- Smeets, S. (2015) Negotiations in the Council of Ministers: ‘And All Must Have Prizes’, Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Steenbergen, M. and Marks, G. (2004) ‘Models of political conflict in the European Union’, in G. Marks and M.R. Steenbergen (eds), European Integration and Political Conflict, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1–12.

- Stevenson, K. and Rose, R. (2016) ‘National party programmes and European integration’, Studies in Public Policy No. 520, Glasgow: Centre for the Study of Public Policy.

- Streeck, W. and Elsässer, J. (2016) ‘Monetary disunion: the domestic politics of Euroland’, Journal of European Public Policy, 23(1): 1–24. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2015.1080287

- Thomson, R. (2010) ‘The relative power of member states in the council’, in D. Naurin and H. Wallace (eds), Unveiling the Council of the European Union, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 238–58.

- Uleri, P. (2000) ‘Plebiscites and plebiscitary politics’, in R. Rose (ed.), International Encyclopedia of Elections, Washington, DC: CQ Press, pp. 199–202.

- Weale, A. (2006) Democratic Citizenship and the European Union, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Weber, M. (1947) The Theory of Social and Economic Organization, translated by A.M. Henderson and Talcott Parsons, Glencoe, IL: Free Press.