ABSTRACT

European integration is increasingly contested in public. What are the policy consequences of this EU politicization? This article argues that politicization challenges the hitherto often technocratic mode of policy preparation in the European Commission. Increased public attention and contestation render the diffuse public a more relevant stakeholder for Europe’s central agenda-setter because future competence transfers to Brussels are more likely to be scrutinized in the public realm. This incentivizes Commission actors to generate widely dispersed regulatory benefits through its policy initiatives, particularly where an initiative covers publicly salient issues. Applying this expectation to 17 European consumer policy initiatives suggests that the Commission orients its policy proposals towards wide-spread consumer interest during periods of high EU politicization and issue salience. However, the mechanism is constrained by internal turf conflicts and anticipated Council preferences. These findings highlight that politicization entails both chances and risks for further, policy-driven integration in Europe.

Introduction

Analyses of European integration increasingly revolve around the idea that supranational ‘decision making has shifted from an insulated elite to mass politics’ (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009: 13). The surge of Eurosceptic parties in the latest European Parliament (EP) elections or the Brexit referendum provide particularly glaring examples for this claim. Contrasting the ‘permissive consensus’ (Lindberg and Scheingold Citation1970), we observe an ‘increase in the polarization of opinions, interests or values and the extent to which they are publicly advanced towards the process of policy formulation within the European Union’ (De Wilde Citation2011: 560).

This politicization is assumed to affect supranational decision-making profoundly (Zürn Citation2014). Some observers argue that public debates enhance the European Union’s (EU) democratic responsiveness (Follesdal and Hix Citation2006; Magnette Citation2001; Rauh and Zürn Citation2014). Others praise technocratic insulation and fear that politicization decreases efficiency and executive leeway in pushing European integration forward (Bartolini Citation2006; Hooghe and Marks Citation2009; Majone Citation2002; Moravcsik Citation1998).

There is, however, only scant empirical knowledge on the actual policy consequences of EU politicization. Recent research debates whether politicization constrained responses to the Euro and Schengen crises (Börzel and Risse Citation2017; Schimmelfennig Citation2014). Other recent evidence suggests that supranational elites communicate public interests more strongly in the face of politicization (De Bruycker Citation2017). But does politicization also affect the mid-range policy choices along the ‘community method’ that have shaped the course of European integration thus far?

The European Commission is particularly relevant for this question. It embodies the tensions of insulated, technocratic policy-making on the one hand, and publically accountable governance on the other (Christiansen Citation1997; Wille Citation2013). Its monopoly of initiative in the regulation of European markets grants significant agenda-setting power over the contents of EU law – a power the Commission has often used in an entrepreneurial manner, adapting treaty interpretations to changing context conditions (Cram Citation1997).

This article argues that EU politicization incentivizes Europe’s central agenda-setter to be more responsive to public interests. A Commission interested in the retention of its competences should aim at widely dispersed regulatory benefits when the EU is heavily debated in public. But this strategy risks alienating traditional stakeholders, most notably member state governments and cross-nationally operating businesses. Hence, the Commission will tilt its proposals towards diffuse public interests mainly in cases where the public is likely to note the respective policy choices. This is true if general EU politicization combines with a high public salience of the specific regulatory issues at stake.

The article provides a plausibility probe of this argument in European consumer policy. Harmonizing European markets in this area, the Commission faces a choice between serving narrowly concentrated producer interests or widely dispersed consumer interests. A summary of 17 case studies on consumer policies between 1999 and 2008 is consistent with the expectation that the Commission’s positioning on this continuum is sensitive to generalized EU politicization and specific issue salience. However, such enhanced responsiveness is constrained by the aggregated preferences of the EU member states and the heightened conflict potential within the Commission itself.

Supranational policy-making in the public spotlight

The politicization of European integration

Supranational integration has always involved political – that is, collectively binding – decisions, but the politicization concept stresses the degree to which these decisions are also collectively debated. Zürn et al. (Citation2012: 71) understand politicization as ‘growing public awareness of international institutions and increased public mobilisation of competing political preferences regarding institutions’ policies or procedures’. Politicization is thus more than just a synonym for declining support for supranational governance. It contains both the resistance against specific international institutions and the formulation of demands for more or other international policies. The concept furthermore reaches beyond institutional disagreement and captures in how far decisions are pulled into the public spotlight. In the context of European integration, Statham and Trenz (Citation2012: 3) understand politicization as debates and controversies on supranational issues in the public sphere. Hutter et al. (Citation2016) also emphasize that politicization finds it expression in decidedly public, mainly mass-mediated debates. In his encompassing conceptualization, De Wilde (Citation2011) defines EU politicization as an increased public involvement of societal actors such as political parties, mass media, social movements in the process of European integration, and the degree to which this resonates among the wider European citizenry.

Despite disagreement on the root causes of this EU politicization, there is a clear convergence on its empirical components (De Wilde et al. Citation2016; Rauh Citation2016: Chapter 2). The first one is salience, meaning the degree to which European integration is visible and important to the broader citizenry. The second component is polarization, meaning the degree to which public opinions on European integration diverge. The third component is mobilization, meaning the extent to which public debates expand to include actors beyond supra- and international executives.

This threefold conceptualization, allows us to assess the long-term, aggregate politicization potential of European integration. To hold context conditions largely constant, while allowing a sufficient time frame and keeping research efforts feasible, I concentrate on the EU-6 countries here. Public salience of the EU is proxied by the monthly share of articles referring to the EU in the headline in one opinion-leading newspaper per country. To study the polarization of public opinion, the seminal Eurobarometer item on support for a country’s EU membership taps into the cumulative assessments of European integration in the wider public (Lubbers and Scheepers Citation2005). I focus on the bi-annual EU-6 averages of the item’s variance and kurtosis as indicators of opinion polarization (Down and Wilson Citation2008). Mobilization on European integration, finally, is captured by the monthly counts of publically staged protest events addressing the EU or its policies (Uba and Uggla Citation2011).Footnote1

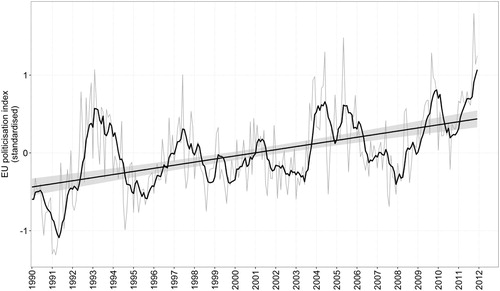

Standardizing and combining these indicators into an additive index provides reliable comparisons of EU politicization over time. As indicated by the OLS time trend in , the politicization potential of European integration in the wider public has consistently increased since the early 1990s – mainly driven by an almost continuously differentiating public opinion on EU membership. But EU politicization is also subject to significant short-term swings driven by local peaks in media salience and protests around major integration events such as EP elections, enlargement rounds, and especially treaty revisions.

Figure 1. Aggregate index of EU politicization (salience, polarization, and mobilization) in the EU-6 countries.

Notes: The grey line presents monthly index values, the black line their six-month moving average. The straight line provides a monthly OLS time trend and its 95% confidence interval. For details, see Rauh (Citation2016: Chapter 2).

From the perspective of Brussels’ hallways, these data suggest that public attention and contestation have become an increasingly important context condition of supranational policy-making while corresponding pressures also fluctuate in the short run. So how, if at all, can we expect the European Commission to respond to the thus shaped politicization of European integration?

Commission policy on and off the public’s radar

One of the most distinguished features of the European Commission is its monopoly in initiating supranational legislation, which provides it with significant agenda-setting powers (Tsebelis and Garrett Citation2000). Like broad strands of the literature, this article assumes that the Commission exploits these powers also to ensure the expansion of its own supranational competences (Franchino Citation2007).Footnote2 This requires that the Commission can build on a sufficient stock of output legitimacy, that is, the added value its activities produce for major stakeholders (Majone Citation2002; Moravcsik Citation2002). Member state governments are most important in this regard. They have delegated competences to the Commission in order to overcome short-term political pressures that hamper cross-national cooperation (Moravcsik Citation1998). Substantially, this delegation has focussed on the stimulation of economic growth through the creation of a common market that removes, overrules, or harmonizes national policies hampering cross-border trade (Scharpf Citation1999). This has rendered cross-nationally operating producers a second important stakeholder group for the Commission (Coen Citation1998).

In the context of EU politicization, however, these traditional sources of output legitimacy are insufficient at best. First, politicization means that the supranational level becomes a much more direct addressee of public evaluation (Zürn Citation2006). The more alert the public becomes to supranational political authority, the more rational it is for a competence-seeking bureaucracy to care about the public acceptability of its policies. Otherwise, the Commission jeopardizes the further transfer of competences to the European level. This may work indirectly where increasing public contestation lets individual national governments adopt more critical positions toward European integration (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009), but it may also work through a much more direct route – as the 2005 referenda in France and the Netherlands, the surge of Eurosceptic parties in the 2014 EP elections, or the Brexit referendum in 2016 have forcefully demonstrated. In either way, the politicization of European integration increases the weight of the wider public in the utility function of a competence-seeking Commission.

Second, the mere pursuit of economic liberalization is hardly suitable to demonstrate an immediate added value to the public. While gains from open markets take time to materialize and often can only be demonstrated by counterfactual arguments, the immediate political costs of liberalization for vested societal interests are instantaneously visible. Moreover, while European elites tend to care mainly about competitiveness, the wider public often prefers market-flanking policies instead (Dehousse and Monceau Citation2009; Hooghe Citation2003). In result, a competence-seeking Commission has incentives to visibly serve such public preferences.

Enhanced responsiveness comes, however, at the cost of undermining the immunity to short-term political pressures and extant policy solutions that the Commission’s traditional stakeholders value. For a competence-seeking bureaucracy trying to generate output legitimacy vis-à-vis all of its stakeholders, this creates trade-offs.

Policy responses to EU politicization should accordingly depend on the Commission’s anticipation whether a particular initiative has a chance to actually influence the public’s overall evaluation of the EU. The public, however, hardly follows each and every proceeding on the supranational agenda. Rather, public attention is selective, particularly on issues exceeding the domestic domain (Oppermann and Viehrig Citation2011). Some Commission initiatives fly safely below the public radar, while others may touch upon specific topics that the public currently cares about.

General EU politicization will thus especially matter if the Commission receives signals that the legislative initiative in question addresses specific issues that the diffuse public currently considers relevant. In this view, the public salience of the specific issues to be regulated – that is, the degree to which these issues are easily understandable and visible among the broader public at the time of drafting (Epstein and Segal Citation2000) – moderates the link between general EU politicization and the Commission’s policy output.

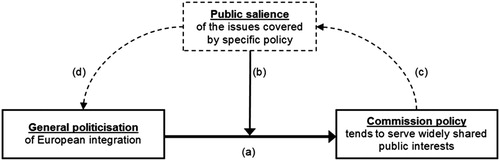

summarizes the model. Politicization renders the European public a more relevant stakeholder for further European integration, incentivizing the Commission to adapt its policy choices to widely shared public interests (a). On the level of individual policy initiatives, this link is moderated by the contemporaneous public attention to the specific issues the respective Commission proposal covers (b).Footnote3 In publically salient domains, the Commission weighs the risk of alienating traditional stakeholders or contradicting extant policy against the risk that its policy position is immediately perceived and understood by the wider public (c). If the latter risk is sufficiently high, the public’s evaluation of the particular initiative may feed back into the overall political evaluation of European integration and, by implication, the Commission’s competences (d).

This argument contains endogeneity in two respects. First, general EU politicization can be understood as a cumulative response to the sum of individual supranational decisions (De Wilde Citation2011: 565–66; Weßels Citation2007). In fact, the proposed argument rests on this assumption. From the Brussels perspective, public attention to an issue area increases the likelihood that the Commission’s final policy choice will actually be perceived by the wider public and taken into account in the general evaluation of the supranational polity – no matter whether the public has perceived the issue as an originally European one in the first place. For an individual legislative initiative, however, the level of the general politicization of European integration is a given context condition that is analytically distinct from the specific contemporaneous salience of the issues the initiative is going to cover.

Secondly, endogeneity may occur on the level of individual initiatives because the Commission can manipulate public salience during policy formulation. Individual Directorates-General (DGs) may try to push an issue up on the public agenda by publishing studies, by circulating consultation documents, or by approaching public media directly. This creates a short circuit in the model, but it does not contradict the expectation that issue-specific public salience is a decisive variable moderating the effects of general EU politicization if the Commission adapts its position after the salience of the initiative in question has been successfully increased. The possibility of such short circuits highlights that an evaluation of the model has to take policy formulation process into account.

Consumer policy

To evaluate the model, we also have to specify which policy choices actually serve widely shared public interests. To render this possible, this article focusses on European consumer policy, defined as regulatory measures that aim at protecting the end user of products or services against risks and disadvantages in economic life (Weatherill Citation2005). The diffuse nature of consumer interests lets us initially expect little political clout vis-à-vis producer interests. Consumer policy often serves as a prime example for collective action problems, which can only be overcome by entrepreneurial regulators (Pollack Citation1997).

Two ideal types of consumer policy are conceivable (Cseres Citation2005: 320). From a purely economic perspective, consumer policies remedy market failures that preclude rational consumers from reaping the full choice offered in a perfect market. Information-seeking and risk bearing rest primarily with the consumers (caveat emptor principle). Regulatory interventions under such a laissez-faire model would solely focus on allocative efficiency and boil down to competition policy or information rules. In contrast, an interventionist model of consumer policy emphasizes the re-allocation of consumer rights (Janning Citation2004; Micklitz and Weatherill Citation1993). This model rests on the assumption that the consumer is structurally disadvantaged in markets obscured by product differentiation and the multiplicity of packaging, advertising, and distribution. Respective regulatory interventions establish producer responsibility for economic and physical consumer risks (caveat venditor).

National consumer policy regimes vary in between these ideal types, which creates trade barriers justifying supranational action in this area. However, harmonizing specific consumer policy issues confronts the Commission with a choice on the level of protection in the proposed European law. The political spoils the Commission can distribute with this choice vary strongly over the ideal-type consumer policy models.

Supranational policies tending towards the laissez-faire model increase market access, pleasing especially producers interested in cross-border trade. This is fully consistent with the traditional market-making mandate of the Commission (Micklitz et al. Citation2004). Respective policies alienate the traditional stakeholders the least. They do not necessarily hurt consumers, but they also do not allow the communication of immediately visible benefits to the diffuse public. Yet, the Commission also has some room to tilt its proposals towards the interventionist model. Since Amsterdam, the treaties entail a clear, albeit legally weak basis for a ‘high level of consumer protection’ (Micklitz et al. Citation2004). In contrast to focussing on market access only when harmonizing European consumer law, proposing more interventionist policies concentrates costs of market risks on a narrow set of producers while the Commission can claim to have protected each and every European consumer.

The more the diffuse public is considered as an important stakeholder, the more attractive is this distribution of narrowly concentrated costs and widely spread political benefits for a competence-seeking Commission. The key choice variable in consumer policy, thus, is the distribution of rights and obligations among producers and consumers. The theoretical model above thus leads to the following hypothesis:

The higher the levels of general EU politicisation and public salience of the regulated issues are, the more Commission initiatives will tend towards an interventionist model of consumer policy.

Research design

Against these challenges, the empirical analysis aims at a ‘plausibility probe’ (Eckstein Citation1975). It intends to show that proposed argument warrants further attention by providing a guided comparison of a medium-N set of detailed qualitative analyses that allow for alternative explanations, within-case variation and explorative insights. Empirically, I draw from a project on position formation inside the European Commission (Hartlapp et al. Citation2014).

The unit of analysis is an individual drafting process that leads to a formal Commission proposal in consumer policy. The policy area is a circumscribable EU competence since Maastricht (Weatherill Citation2005), but only the Prodi Commission established a fully fledged DG with a respective legislative mandate (DG SANCO, Guigner Citation2004). Accordingly, the investigation period starts in 1999 and ends with the onset of the broader project in 2008, covering two Commission terms in full.

I first identified all 247 proposals for binding secondary EU law that the Commission itself flagged as consumer policy.Footnote4 Given the ambition to trace individual drafting processes in detail, this had to be broken down further. Constructing a perfectly guided sample, however, was not achievable since key variables of the model – most notably consumer interventionism and issue salience – were not readily available ex ante. Thus I rather aimed at capturing relevant variation in the sample by three steps. First, I scattered the selected initiatives across the investigation period to maximize the chance to find variation in EU politicization and issue salience. Second, I tried to avoid biases towards or against consumer interventionism by including cases drafted in different Commission DGs and subject to varying internal coordination logics (oral and written procedures). Finally, to capture the Commission’s most relevant consumer policy choices, I selected the cases with the broadest legal scope from the resulting strata, that is, preferring general purpose instruments over product- or service-specific regulations. This results in the 17 policy initiatives summarized in . While this is a purposive sample aimed at learning rather than generalization, note that it contains all essential legislative initiatives on contractual consumer rights, product safety, and food safety submitted by the Prodi and Barroso I Commissions.

Table 1. Sample of legislative drafting processes in consumer policy (1999–2008) and summary of case study results.

To capture the dependent variable – consumer interventionism proposed by the Commission – each legislative proposal was divided into a set of key provisions, meaning an array of articles that distribute logically linked rights among consumers and producers.Footnote5 For each provision, I then compare extant policy options, stakeholder demands, and the choices in the final legislative text to the respective regulatory status-quo. The dependent variable captures whether the Commission proposal undermines, exceeds, or simply reinforces the regulatory distribution of rights and risks among producers and consumers. This requires a detailed and rather technical perspective at times but provides replicable qualitative judgements (Rauh Citation2016: Appendix E).

Regarding the major independent variable, I resort to the EU politicization index developed above. Cross-case comparisons focus on the index’ mean levels while within-case comparisons take its fluctuation during the drafting period into account. The second independent variable, public salience of specific issues, is proxied by media prominence during the drafting periods (Epstein and Segal Citation2000). An automated content analysis retrieved the terms most frequently used by and across the different actors that issued position papers on the Commission proposals in food safety, product safety, and contractual consumer rights, respectively. These term lists were used as inputs for a LexisNexis newspaper search, resulting in a monthly indicator for their media prominence. These three broad salience indicators were complemented by a case specific, qualitative analysis of newspaper articles retrieved by searches along specific key words used in the recitals of the respective Commission proposal (Rauh Citation2016: Appendix C3).

Beyond comparisons of the model’s input and output variables, the analysis asses validity of the proposed argument also by systematically analysing within-case variation while taking explorative insights and major alternative explanations into account. Since access to internal Commission data is restricted, the corresponding case histories draw strongly on interviews with involved Commission officials (Rauh Citation2016: 57). Interviewees were identified along the officials’ formal positions during the respective drafting processes and reputational information gained during initial research. Information was cross-validated by trying to talk to all involved Commission DGs and hierarchy levels. A total of 41 officials could be interviewed for the cases at hand. The greatest cluster (20 officials) lies in DG SANCO, which signed responsible for the majority of proposals and was associated to all others. Lower Commission echelons could be more easily accessed (24 desk officers), but the underrepresentation of higher hierarchies is also due to the fact that they tend to sign responsible for several cases in the sample (10 heads of unit, 3 Directors, and 4 Cabinet members).

Finally, this was complemented with a broad range of secondary information from internal process documentation, discussion papers, consultation documents, press releases, and impact assessments, as well as interest group’s position papers and coverage by Agence Europe and major European newspapers. Pulling these sources together, systematically structured case histories were drawn up for each of the 17 drafting processes (Rauh Citation2016: Chapters 4–6), focussing on the temporal dynamics in the model’s main variables as well as the role of internal conflicts and anticipation of member state preferences. The remainder of the article summarizes the key insights of these analyses.

Findings: serving widely shared interests under constraints

Comparing policy initiatives

condenses the case studies. Seven initiatives favoured more consumer rights as compared to the regulatory status-quo. In five cases, the respective initiative rather emphasized producer freedom while four proposals merely reinstated the status-quo. Departmental divisions in the Commission do not explain this pattern. For example, the proposed consumer interventionism varies heavily across the proposals drafted by the then DG for Health and Consumer Protection (SANCO).

How plausible is it, however, that the combination of EU politicization and issue salience pushes the Commission towards consumer-friendly regulation? Clearly, a purposively constructed medium-N sample hardly allows immediate generalization. But already the aggregate view on the 17 major policy initiatives highlight that the argument cannot be readily refuted. Focussing on the mean levels of politicization and salience during the respective drafting period unveils seven cases that appear immediately consistent with the theoretical model. Comparatively high values on both independent variables are associated with a re-distribution of rights favourable to consumers in the initiatives on universal service, air passenger rights, consumer credit, and food information. Where high politicization combined with only low public salience of the specific issues, the Commission initiatives on sales promotions, pyrotechnic articles, and food supplements exhibited further liberalization of the affected laws instead.

Other initiatives defy clear-cut judgments, especially where we observe only intermediate levels on the dependent variable. In the consumer rights case, for example, high levels of EU politicization and issue salience occurred during drafting, but the final proposal took an interventionist position on only some, particularly salient key provisions covering online trade. Other provisions reinforced or undermined the status-quo, for example, with regard to guarantee periods. Similarly mixed interventionism abounds for the toy safety, the ‘new approach’, and the food additives proposals.

More importantly, there are four drafting processes for which we only have intermediate politicization values. The table’s classification assesses whether the mean of the politicization index in the drafting period differs significantly from the average politicization levels observed before. This sets the bar very high and points to a conceptual threshold problem. EU politicization has increased, but we do not know which level is sufficient to create the theorized Commission incentives and whether this level has been reached before the investigation period already. Future research could tackle this by testing the argument in earlier periods of integration, by normalizing the politicization of European integration against other political issues (Hoeglinger Citation2016), or by comparing policy responses to politicization across different international organizations (Rauh and Bödeker Citation2016). For the present project, we have to focus on the within-case variation discussed below.

The comparative perspective yields more consistency on issue salience. Of the eight cases that indicate interventionist deviations from the status-quo, six were drafted under comparatively high media attention to the issues covered by the respective proposal. The four cases with intermediate interventionism are also roughly in line. Two of these – the ‘new approach’ revision and the food additives proposal – merely re-codified the regulatory status-quo. The two others – consumer rights and toy safety – contained some liberalizing but also some rather interventionist provisions on specific issues that were on the public agenda at the time of drafting. Regarding online terms and conditions as well as chemicals in toys, the Commission was responsive, although these specific issues did not tip the aggregate judgement on these proposals.

In sum, the comparative summary yields seven cases fully consistent with the theoretical model, six cases where it can neither be confirmed nor falsified, and two cases in which the observed consumer interventionism was not driven by EU politicization and issue salience. While these findings cannot be readily generalized, the patterns encourage further analysis of the argument.

Adapting positions during drafting

The Commission’s choices on consumer interventionism during the drafting process provide additional information to evaluate the theoretical argument’s plausibility. Panel three in provides a rough indication during which stage politicization and issue salience reached their mode, and notes whether this coincided with swings towards more interventionist or liberalizing positions.

This within-case perspective initially reinforces the role of issue salience. For example, in toy safety, DG ENTR foresaw rather liberal rules during more than five years of drafting but suddenly adopted more interventionist provisions on safety requirements, on chemical regulation, and on labelling once huge recalls of Chinese toys hit the European market in 2007. The soaring public salience of the issue – not the least driven by poisoned Barbie dolls in the European market – put DG ENTR under pressure in the final stages of drafting because ‘people wanted to have immediate results’ (COM25:234). The late inclusion of a social review clause into the universal service proposal, when media attention to widespread internet access rose in late 1999, serves as a similar example.

More importantly, the reconstruction of the drafting processes reveals cases during which issue-specific media prominence remained stable and the Commission adapted its position along swings in the EU politicization index. The 2001 air passenger rights proposal provides an example. Commission officials were aware that bad customer treatment by airline companies ‘was all the time in the media’ (COM33:136), but DG TREN only committed to a formal initiative when the general EU politicization started to rise again during the preparation of the Nice negotiations. In this context, the drafting officials argued that the EU-induced air transport liberalization had been about ‘advantages for the industry’ while it was now time to ‘refocus transport policy on the demands and needs of its citizens’ (COM33:140). Against outright industry opposition, the officials publically proposed to quadruple consumer compensations for delayed and cancelled flights only when EU politicization had almost reached its local 2001 peak.

The same peak was exploited by DG SANCO in drafting the proposal on consumer credit. In contrast to what was internally agreed with DG MARKT before, SANCO only then publically committed to very interventionist positions in this proposal. This concerned the inclusion of mortgages and especially a principle that made creditors responsible for correctly assessing the financial situation of debtors. Knowing that this was ‘a very political file […] with a big public appeal’ (COM119:171), the officials tried ‘to create a very comprehensive, very exhaustive consumer credit regulation which would be burdensome for industry’ (COM89:46).

Also during that summer, SANCO’s initial preparations for the unfair commercial practices proposal entailed a generalized producer duty for fair trading. However, this interventionist position was scaled down to a neatly circumscribed set of prohibited practices during the sub-standard levels of politicization in the years 2002 and 2003. This change of the Commission’s policy position occurred despite constant media prominence of unfair commercial practices in cross-border online trade.

Likewise, the high politicization phases in 2004 and 2005, and the later decline were mirrored in Commission positions. The proposed ‘new approach’ overhaul provides evidence. Major enhancements of market surveillance such as the centralization of the notification system were contemplated by DG ENTR during 2004. This was later cut back to a mere re-codification of the existing rules during the final stages in 2006 and 2007. The other ‘neutral’ case in the sample showed a parallel decline in Commission interventionism. When formulating the policy on food additives, DG SANCO considered the inclusion of processing aids and the time-limited authorization of additives during the high politicization phase of 2005, but dropped these ideas against producer opposition when EU politicization reverted during the final stages of drafting. Lastly, even in the finally rather interventionist 2008 Commission proposal on food information we see concessions to producers on alcoholic beverages and origin labelling in parallel to declining EU politicization in the last half-year of position formation. Again, this happened despite rising public salience as captured in frequent media reporting on food regulation.

All these examples concern only parts of the policy proposals, and they switched the judgement on the final outcome only for some. But these within-case adaptations of policy positions provide tangible evidence consistent with the theoretical claims. Not only was the Commission sensitive to varying salience of the specific issues in question, but where salience remained stable, its policy positions also mirrored major upsurges and declines in general EU politicization.

Procedural observations and alternative explanations

The case histories reveal additional detail on how EU politicization and issue salience affect the intricacies of policy drafting inside the Commission, but also indicate limits of the theorized effect.

More interventionist choices by the Commission usually met very explicit opposition of affected industry groups. Only in three product safety cases, certain industries supported a more interventionist stance as a means to protect them against external competition, most notably from China. Lobbying by consumer groups – especially through their European umbrella organization, BEUC – could be observed across all but one proposal in the sample. They consistently pushed for more interventionist rules. But only in cases subject to high EU politicization and issue salience, the Commission’s policy choices indicate neat congruence to the demands that consumer groups voiced in their position papers. This also holds within cases: shifts towards more interventionist policy positions occurred most often by explicitly taking those consumer group demands on board that had been declined earlier. Public interest groups provide the Commission with readily available templates for which public attractiveness can be assumed. This finding bodes well with research on public salience as a relevant lobbying resource (De Bruycker Citation2016; Dür and Mateo Citation2014; Klüver Citation2011).

The case studies furthermore suggest that salient initiatives in a politicized context involve the Commission’s political hierarchies to a greater extent. For example, either rising politicization levels as in the consumer credit case or increasing issue salience as in the toy safety case made desk officials explicitly seek the political backing of their cabinets and Commissioners. The administrative level, however, has significant agenda-setting powers in this regard. As one official put it: ‘the services, we have a larger view, which allows us to choose at every moment, depending on the political momentum, the kind of proposal we would like to boost at that time’ (COM33:164). In the bus and maritime passenger cases, an outgoing Commissioner opposed more interventionism, but the service level merely paused until the political leadership changed.

Commissioner nationality or partisanship hardly explain consumer policy choices – in the present sample interventionism varies more within than across Commissioners’ office terms. The comparatively liberal proposals on unfair commercial practices or the food fortification initiative but also the highly interventionist proposals on consumer credit or health claims, for example, were adopted under Commissioner Byrne. In 10 cases, the political leadership of the lead DG changed during drafting, but no changes in consumer interventionism could be detected in response. Future research studying policy effects of politicization should then not only focus on the Commission’s political leaders but also on its administrative echelons.

The findings indeed suggest that public attention creates opportunities for competence-seeking bureaucrats. In a number of instances, Commission DGs actively tried to increase public salience in order to garner support for their regulatory plans. Glaring evidence abounded in the air passenger rights case. In a context of repeated media reporting on overbooking practices of airline companies, DG TREN publically pushed airlines into a voluntary agreement only to override it with an even stronger regulation later on. Similarly, DG SANCO used widely circulated consultations, the publication of studies, and a range of soft-law measures on obesity in Europe to prepare the ground for its encompassing and comparatively interventionist food information proposal.

In this vein, politicization and issue salience can be both a driver and an asset for turf conflicts inside the Commission. The case studies highlight that more interventionist policy plans are internally often opposed by DGs that defend their traditionally more liberal approach. For example, DG SANCO’s interventionist positions in the consumer credit case met the fierce opposition of DG MARKT. But once politicization peaked in 2001 against a constantly high salience of consumer over-indebtedness in the press, DG SANCO waged to publically commit to internally highly contested provisions, for example, on the responsible lending principle, and managed to assert most of them until the proposal was formally adopted. DG SANCO had also been unsuccessfully pressing DG ENTR on a clear reference to its own, more interventionist general product safety directive in ‘new approach’ instruments. Only when a range of toy recalls increased public salience during late 2007 when ENTR drafted a regulation on toy safety along this model, SANCO’s long-standing demands suddenly became assertive. Here, DG SANCO strategically used the publication of its own data on toy recalls as well as several public speeches of its own Commissioner to put political pressure on DG ENTR. Likewise, frequent newspaper appearances and speeches of Commissioner Kuneva promoting consumer protection by the Commission shielded the 2008 consumer rights proposal against internal concessions during the final internal negotiations with DG MARKT.

For future research on Commission responsiveness, these examples highlight two things. First, extending the competence-seeking assumption to individual Commission DGs helps to explain policy choices of the Commission as a whole. Second, EU politicization and issue salience can present an opportunity structure for some of these internal actors – supporting especially policy mandates that address diffuse public concerns more directly.

While these findings make it plausible that public politicization and issue salience affect the Commission’s policy choices, the case studies also underscore that the member state governments remain the Commission’s most important stakeholders. In 13 cases, drafting officials engaged strongly in uncovering the political feasibility of policy choices in the Council. Strategies included not only formal communications to the Council and consultation of individual governments, but also the involvement of national working groups in which consecutive draft proposals were negotiated. Comparing the final legal texts to national concerns voiced during drafting indicates that the latter sometimes provide upper bounds for consumer interventionism. For example, the Commission excluded products used in services from the scope of the general product safety directive or removed obligatory colour-coded nutrient information from the food information proposal in response to anticipated Council opposition. But sometimes national preferences also provided lower bounds and limited liberalization plans envisaged by the responsible DG. For instance, most of the remaining trade restrictions in the pyrotech proposal can be traced to national demands. National preferences thus trimmed the lead DG’s ideal positions without determining them fully. This suggests that the political feasibility in the Council defines the leeway in which the Commission’s policy reactions to the politicization of European integration can unfold.

A Commission official summarizes this succinctly:

We have looked at an issue and we are trying to move forward in line with the common European interest. But then there are two considerations. One is: can we get this through? You know, if you propose something that has no chance of getting through […] it makes us look politically impotent and it doesn’t help Europeans. And the other side is that we would hope that everything we do is something that can be explained to the citizens because it is in their interest. But obviously sometimes the easier it is to make that case, the more we like the dossier. (COM113:98)

Conclusion: chances and risks of politicization

The 17 case studies of policy formulation in European consumer policy between 1999 and 2008 provide multiple observations consistent with the argument that widespread EU politicization creates Commission incentives to serve immediate public interests in contemporaneously salient initiatives. The plausibility probe suggests that even Commission bureaucrats, who are usually portrayed as the most distant and technocratic actors in the EU’s polity, are aware about the immediate distributional consequences of their policy choices and are willing to adapt them to changes in the political context of European integration. To put it in the words of one of these officials:

Certainly, if we want to continue, probably best would be to improve the people’s acceptance of the EU integration process – we should legislate in a way that people can identify with the level at which the decision is taken and with the substance of what we are doing. (COM81:40)

These findings suggest that EU politicization can indeed increase supranational responsiveness. It creates an incentive structure in which non-governmental organizations representing diffuse societal interests can strengthen their influence on supranational policy by raising the public salience of their requests (cf. De Bruycker Citation2016; Dür and Mateo Citation2014; Klüver Citation2011). EU politicization is thus not only constraining – in policy fields that allow the immediate presentation of wide-spread public benefits it may also lead to more integration instead.

Enhanced output responsiveness may help in convincing European citizens that EU policies are not fundamentally biased against public preferences. This will not fully gratify the proponents of a politicized integration process whose benchmark is popular democracy (Hix Citation2006). Nevertheless, the Commission’s engagement in demonstrating immediate public benefits creates a valuable precondition for enhancing input legitimacy in the future. The more citizens become aware that Europe can do something for them in the short term as well, the more EP elections would be about the European policies that citizens actually demand – carrying them beyond being mere contests on whether voters support the EU in principle.

Yet, as feared by critics of more politicized decision-making (Majone Citation2002) the price for such responsiveness is less efficiency. Public salience can lead the Commission to challenge deeply entrenched regulatory solutions, resulting in partly contradictory law and pronounced internal turf conflicts. The case studies furthermore underline that the political feasibility of Commission initiatives in the Council remains a decisive constraint. An overall assessment of the policy consequences of politicization has to take its effects on Council decisions into account. A reduced bargaining space or biases towards member states with stronger domestic dissensus are plausible expectations in this regard (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009; Wratil Citation2018).

Caution is also warranted when generalizing these insights to other policy domains. On the one hand, the Commission’s activity in social policy is likely to remain regulatory in nature (Cram Citation1997). On the other hand, an initiative’s salience mediates only whether the Commission considers the public’s reception in a politicized climate, while the question of how it responds is subject to the distribution of societal interests on the issue in question. For the latter, consumer policy is an easy case. Narrowly concentrated and widely dispersed interests can be identified and cut across European societies. In other recently salient issue areas such as social spending, migration, or monetary policy, the public is split along class lines, along identity considerations, and even along national borders (Hutter et al. Citation2016; Scharpf Citation2010). In such contexts, the logics presented here may drive a Commission that is sensitive to EU politicization to blame avoidance strategies, letting it shy away from decisions on salient but much more controversial issues in which no unequivocal societal winners can be identified.

In this view, EU politicization is both a chance and a risk for further European integration. To disentangle positive and negative effects, future large-N research could extend the initial empirical insights to longer time periods, different policy areas, and other institutions in the supranational decision-making process. Capturing interventionism by automated text scaling of policy choices against interest groups or public demands provides a promising tool in this regard (e.g., Klüver Citation2011). The plausibility probe summarized here highlights that we need more research on how European institutions can channel widespread public contestation into acceptable policy choices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributor

Dr Christian Rauh is a senior researcher in the Global Governance department of the WZB Berlin Social Science Center. More information at www.christian-rauh.eu

Notes

1 A more detailed discussion of these indicators is provided in Rauh (Citation2016: Chapter 2). Data are available at www.christian-rauh.eu/data-and-resources (accessed 5 March 2018).

2 Given varying attitudes in the Commission (Kassim et al. Citation2013), this is a simplifying assumption. However, Commission officials tend to assess their organizational environment along rational calculations (Bauer Citation2012) and realize that the politicization of European integration challenges supranational competences (Bes Citation2017). The model developed here also works with the more constrained assumption that Commission officials on average hold a preference to at least retain the regulatory powers of the Commission.

3 This implies an interaction effect of general EU politicization and the salience of specific issues. Both together account for policy choices geared towards serving wide-spread interests. In a hypothetical scenario in which supranational authority is not publically contested at all, salience of specific issues should not have a direct effect on a Commission without direct electoral accountability. Conversely, where the contemporaneous public would not care about a specific issue at all, the Commission should not deviate from the interests of its primary stakeholders.

4 Identification resorted to the EUR-Lex directory codes ‘general consumer policies’ (15.20.10), ‘consumer information, education and representation’ (15.20.20), ‘protection of consumer health and safety’ (15.20.30), and ‘protection of economic interests’ (15.20.40). The full universe of cases is part of the replication package.

5 For example, the 2008 proposal on consumer rights comprises six key provisions on scope and harmonization approach, pre-contractual information obligations for traders, trader obligations for off-premise and distance contracts, trader obligations after the sales contract, commercial guarantees and general rules on contract terms.

References

- Bartolini, S. (2006) ‘Mass politics in Brussels: how benign could it be?’ Zeitschrift für Staats- und Europawissenschaften 4(1): 28–56. doi: 10.1515/ZSE.2006.002

- Bauer, M. (2012) ‘Tolerant, if personal goals remain unharmed: explaining supranational bureaucrats’ attitudes to organizational change’, Governance 25(3): 485–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0491.2012.01572.x

- Bes, B.J. (2017) ‘Under pressure! The institutional role conceptions of commission officials in an era of politicization’, Ph.D. dissertation, Faculteit der Sociale Wetenschappen, VU Amsterdam.

- Börzel, T. and Risse, T. (2017) ‘From the euro to the Schengen crises: European integration theories, politicization, and identity politics’, Journal of European Public Policy 25(1):83–108.

- Christiansen, T. (1997) ‘Tensions of European governance: politicized bureaucracy and multiple accountability in the European Commission’, Journal of European Public Policy 4(1): 73–90. doi: 10.1080/135017697344244

- Coen, D. (1998) ‘The European business interest and the nation state: large-firm lobbying in the European Union and member states’, Journal of Public Policy 18: 75–100. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X9800004X

- Cram, L. (1997) Policy-making in the European Union: Conceptual Lenses and the Integration Process, London: Routledge.

- Cseres, K. (2005) Competition Law and Consumer Protection, The Hague: Kluwer Law International.

- De Bruycker, I.C.J.-R. (2016) ‘Pressure and expertise: explaining the information supply of interest groups in EU legislative lobbying’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 54(3): 599–616.

- De Bruycker, I. (2017) ‘Politicization and the public interest: when do the elites in Brussels address public interests in EU policy debates?’ European Union Politics 18(4): 603–19.

- De Wilde, P. (2011) ‘No polity for old politics? A framework for analyzing the politicization of European integration’, Journal of European Integration 33(5): 559–75. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2010.546849

- De Wilde, P., Leupold, A. and Schmidtke, H. (2016) ‘Introduction: the differentiated politicisation of European governance’, West European Politics 39(1): 3–22. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2015.1081505

- Dehousse, R. and Monceau, N. (2009) ‘Are EU policies meeting Europeans’ expectations?’, in R. Dehousse, F. Deloche-Gaudez and S. Jacquot (eds), What is Europe up to? Paris: Presses de Sciences Po, pp. 26–38.

- Down, I. and Wilson, C. (2008) ‘From “permissive consensus” to “constraining dissensus”: a polarizing union?’ Acta Politica 43(1): 26–49. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500206

- Dür, A. and Mateo, G. (2014) ‘Public opinion and interest group influence: how citizen groups derailed the anti-counterfeiting trade agreement’, Journal of European Public Policy 21(8): 1199–217. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2014.900893

- Eckstein, H. (1975) ‘Case study and theory in political science’, in F.I. Greenstein and N.W. Polsby (eds), Handbook of Political Science, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, pp. 79–138.

- Epstein, L. and Segal, J. (2000) ‘Measuring issue salience’, American Journal of Political Science 44(1): 66–83. doi: 10.2307/2669293

- Follesdal, A. and Hix, S. (2006) ‘Why there is a democratic deficit in the EU: a response to Majone and Moravcsik’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 44(3): 533–62.

- Franchino, F. (2007) The Powers of the Union: Delegation in the EU, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Guigner, S. (2004) ‘Institutionalizing public health in the European Commission: the thrills and spills of politicization’, in A. Smith (ed.), Politics and the European Commission. Actors, Interdependence Legitimacy. London: Routledge, pp. 96–115.

- Hartlapp, M., Metz, J. and Rauh, C. (2014) Which Policy for Europe? Power and Conflict Inside the European Commission, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hix, S. (2006) ‘Why the EU needs (left-right) politics? Policy reform and accountability are impossible without it’. Notre Europe, Policy Paper 19.

- Hoeglinger, D. (2016) ‘The politicisation of European integration in domestic election campaigns’, West European Politics 39(1): 44–63. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2015.1081509

- Hooghe, L. (2003) ‘Europe divided?: Elites vs. public opinion on European integration’, European Union Politics 4(3): 281–304. doi: 10.1177/14651165030043002

- Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2009) ‘A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: from permissive consensus to constraining dissensus’, British Journal of Political Science 39(1): 1–23. doi: 10.1017/S0007123408000409

- Hutter, S., Grande, E. and Kriesi, H. (2016) Politicising Europe: Integration and Mass Politics, Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Janning, F. (2004) ‘Der Staat der Konsumenten. Plädoyer für eine politische Theorie des Verbraucherschutzes’, in R. Czada and R. Zint (eds), Politik und Markt. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag, pp. 151–85.

- Kassim, H., et al. (2013) The European Commission of the Twenty-first Century, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Klüver, H. (2011) ‘The contextual nature of lobbying: explaining lobbying success in the European Union’, European Union Politics 12(4): 483–506. doi: 10.1177/1465116511413163

- Lindberg, L. and Scheingold, S. (1970) Europe's Would-be Polity: Patterns of Change on the European Community, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Lubbers, M. and Scheepers, P. (2005) ‘Political versus instrumental euro-scepticism: mapping scepticism in European countries and regions’, European Union Politics 6(2): 223–42. doi: 10.1177/1465116505051984

- Magnette, P. (2001) ‘European governance and civic participation: can the European Union be politicised?’, Symposium: Mountain or Molehill? A Critical Appraisal of the Commission White Paper on Governance (Jean Monnet Working Paper 06/01), The Jean Monnet Center for International and Regional Economic Law and Justice, New York.

- Majone, G. (2002) ‘The European Commission: the limits of centralization and the perils of parliamentarization’, Governance 15(3): 375–92. doi: 10.1111/0952-1895.00193

- Micklitz, H.W. and Weatherill, S. (1993) ‘Consumer policy in the European Community: before and after Maastricht’, Journal of Consumer Policy 16(3): 285–321. doi: 10.1007/BF01018759

- Micklitz, H., Reich, N. and Weatherill, S. (2004) ‘EU treaty revision and consumer protection’, Journal of Consumer Policy 27(4): 367–99. doi: 10.1007/s10603-004-3244-x

- Moravcsik, A. (1998) The Choice for Europe: Social Purpose and State Power from Messina to Maastricht, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Moravcsik, A. (2002) ‘In defence of the “democratic deficit”: reassessing legitimacy in the European Union’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 40(4): 603–24.

- Oppermann, K. and Viehrig, H. (2011) Issue Salience in International Politics, London: Routledge.

- Pollack, M.A. (1997) ‘Representing diffuse interests in EC policy-making’, Journal of European Public Policy 4(4): 572–90. doi: 10.1080/135017697344073

- Rauh, C. (2016) A Responsive Technocracy? EU Politicisation and the Consumer Policies of the European Commission, Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Rauh, C. and Bödeker, S. (2016) ‘Internationale Organisationen in der deutschen Öffentlichkeit – ein Text Mining Ansatz’, in M. Lemke and G. Wiedemann (eds), Text-Mining in den Sozialwissenschaften. Grundlagen und Anwendungen zwischen qualitativer und quantitativer Diskursanalyse, Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 289–314.

- Rauh, C. and Zürn, M. (2014) ‘Zur Politisierung der EU in der Krise’, in M. Heidenreich (ed.), Krise der europäischen Vergesellschaftung? Soziologische Perspektiven, Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 121–45.

- Scharpf, F. (1999) Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Scharpf, F.W. (2010) ‘The asymmetry of European integration, or why the EU cannot be a “social market economy”’. Socio-Economic Review 8(2): 211–50. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwp031

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2014) ‘European integration in the Euro crisis: the limits of postfunctionalism’, Journal of European Integration 36(3): 321–37. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2014.886399

- Statham, P. and Trenz, H.-J. (2012) The Politicization of Europe: Contesting the Constitution in the Mass Media, Abingdon: Routledge.

- Trumbull, G. (2006) Consumer Capitalism: Politics, Product Markets, and Firm Strategy in France and Germany, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Tsebelis, G. and Garrett, G. (2000) ‘Legislative politics in the European Union’. European Union Politics 1(1): 9–36. doi: 10.1177/1465116500001001002

- Uba, K. and Uggla, F. (2011) ‘Protest actions against the European Union, 1992–2007’, West European Politics 34(2): 384–93. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2011.546581

- Weatherill, S. (2005) EU Consumer Law and Policy, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Weßels, B. (2007) ‘Discontent and European identity: three types of euroscepticism’, Acta Politica 42(2–3): 287–306. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500188

- Wille, A. (2013) The Normalization of the European Commission: Politics and Bureaucracy in the EU Executive, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wratil, C. (2018) ‘Modes of government responsiveness in the European Union: evidence from council negotiation positions’, European Union Politics 19(1): 52–74.

- Zürn, M. (2006) ‘Zur Politisierung der Europäischen Union’, Politische Vierteljahresschrift 47(2): 242–51. doi: 10.1007/s11615-006-0038-6

- Zürn, M. (2014) ‘The politicization of world politics and its effects: eight propositions’, European Political Science Review 6(1): 47–71. doi: 10.1017/S1755773912000276

- Zürn, M., Binder, M. and Ecker-Ehrhardt, M. (2012) ‘International authority and its politicization’, International Theory 4(1): 69–106. doi: 10.1017/S1752971912000012