ABSTRACT

Immigration has become a hot topic in West European politics. The factors responsible for the intensification of political conflict on this issue are a matter of considerable controversy. This holds in particular for the role of socio-economic factors and of radical right populist parties. This article explores the politicization of immigration issues and its driving forces in the electoral arena. It is based on a comparative study using both media and manifesto data covering six West European countries (Austria, France, Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland, and the UK) for a period from the early 1990s until 2017. We find no association between socio-economic factors and levels of politicization. Political conflict over immigration follows a political logic and must be attributed to parties and party competition rather than to ‘objective pressures.’ More specifically, we provide evidence that the issue entrepreneurship of radical right populist parties plays a crucial role in explaining variation in the politicization of immigration.

Introduction: who is politicizing immigration in Western Europe?

In the last decade, European countries have witnessed a new wave of immigration which has been nurtured from diverse sources, among them labour market-driven migration within the European Union (EU) after Eastern enlargement and refugees and asylum seekers from politically unstable and economically less developed regions in Africa and Asia. Likewise, public attention of immigration issues has increased in Western Europe and political conflict has intensified both at the domestic and the European level (Messina Citation2007; Van der Brug et al. Citation2015). At the European level, existing legal obligations and commitments, for example in the field of asylum policy, have caused controversies among member states and have met with domestic resistance. Within EU member states, immigration has become a ‘hot topic’ (Green-Pedersen and Otjes Citation2017). Conflicts over immigration have become salient in national elections; they played a major role in some national referenda (most consequentially in the ‘Brexit’ campaign); and they have had a significant impact on the political agendas of governments.

Conventional explanations of the politicization of immigration in Western Europe hold that it is the combined result of two factors: a significant increase of immigration in recent years, which is overstraining the capacities of national states to control their borders and to accommodate and integrate new migrants, on the one hand; and the successful exploitation of these challenges by radical right populist parties, on the other hand. The decisive role of these parties in the emergence of new political conflicts on issues such as immigration and European integration has been emphasized by several strands of research, among them (neo-)cleavage theory (Hooghe and Marks Citation2018; Kriesi et al. Citation2012; Kriesi et al. Citation2008), post-functionalist integration theory (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009) and the theory of issue entrepreneurship (Hobolt and de Vries Citation2015). These theories argue that the new issues are most successfully mobilized by ‘populist, non-governing parties’ (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009: 21), radical right populist parties using nationalist-identitarian frames in particular.

Such arguments find only limited support in the literature on the politicization of immigration, however. While there is conclusive evidence of an increasing salience of immigration issues since the 1990s (Green-Pedersen and Otjes Citation2017; Van der Brug et al. Citation2015), we find remarkable disagreement on the driving forces of politicization. The most comprehensive study on this topic by Van der Brug et al. (Citation2015) attributes increasing salience of immigration issues neither to socio-economic factors nor to the mobilizing force of radical right challenger parties. They conclude that ‘politicisation is very much a top-down process, in which government parties play an especially important role’ (Van der Brug et al. Citation2015: 195). This is in line with work by Bale (Citation2008), Green-Pedersen and Krogstrup (Citation2008) and Meyer and Rosenberger (Citation2015) who argue that mainstream center-right parties are the main drivers of the politicization of immigration issues in Europe.

Evidently, despite a rapidly expanding literature on the politics of immigration, our understanding of the main factors responsible for politicizing immigration issues in Western Europe is still unsatisfactory. This is partly due to a narrow focus of previous research on specific aspects of politicization, either on the positioning of parties on immigration issues or on their salience. Moreover, most studies rely on a single data source (media data or manifesto data) to analyze partisan conflicts over immigration assuming that each of these data sources provides a full picture of the most relevant activities of political parties.

This article contributes to this research in two related ways. First, by using a multi-dimensional concept of politicization which combines salience and polarization as suggested in the recent literature on politicization (De Wilde Citation2011; Hoeglinger Citation2016; Hutter and Grande Citation2014; Hutter et al. Citation2016; Kriesi Citation2016), we provide a comprehensive analysis of the development of political conflict over immigration issues in national elections in the period from the early 1990s until 2017. Our comparative analysis includes six West European countries, namely Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom (UK). Second, by combining media data and manifesto data for the analysis of political conflict over immigration in the electoral arena, we provide a more nuanced picture of the driving forces of the politicization of immigration issues by political parties. Most importantly, our approach allows distinguishing between strategic drivers of politicization on the one hand, and the visibility of political parties in election debates, on the other hand.

Which factors are actually responsible for the politicization of immigration issues in national election campaigns? Three findings of our analysis deserve mention. First, politicization of immigration is not correlated with socio-economic factors such as the annual change in the number of immigrants entering a country or the level of unemployment. Political parties enjoy substantial strategic leeway in responding to immigration challenges in election campaigns. Second, our analysis of manifesto data confirms that radical right populist parties are issue entrepreneurs which strategically drive the politicization of immigration issues. This is not to say that the strategic efforts of challenger parties to emphasize the immigration issue in their manifestos necessarily results in high visibility of these parties in public election campaigns. Our analysis of campaign debates suggests that both radical challenger parties and mainstream parties can dominate these debates.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

The politics of immigration include a broad range of topics including public attention to immigration issues, the positioning of political parties towards these issues and political protest and violence, to mention only some of the most important ones. The dependent variable of our analysis is the level of politicization of immigration issues in national election campaigns. Our conceptualization of politicization emphasizes political conflict, the ‘scope of conflict’ more specifically (Schattschneider Citation1975 [1960]: 16). Our analysis investigates situations of intense political conflict on immigration issues among political parties in the electoral arena. In line with the scholarly literature, we focus on ‘party political attention’ (Green-Pedersen and Otjes Citation2017: 2) to immigration as previous research shows that other political actors such as civil society groups and social movements are of secondary importance with regard to the politicization of immigration in Western Europe (Kriesi et al. Citation2012). Key questions then are: What drives the politicization of immigration issues? How relevant are political forces as compared to other factors, such as socio-economic variables?

In the literature on migration, socio-economic variables figure prominently. These variables include national migration patterns, the composition of the migrant population, models of integration and economic conditions such as the level of unemployment or the annual rate of economic growth. The relationship between these factors and various political aspects related to immigration (e.g., popular attitudes towards immigrants, the strength and electoral success of anti-immigration groups and parties, the politicization of immigration issues in public debates and elections) have been a recurring topic in the scholarly literature (Green-Pedersen and Otjes Citation2017; Hainmueller and Hopkins Citation2014; Van der Brug et al. Citation2015). Arguments focusing on immigration patterns assume that politicization is a response to an increase in the migrant population and of its composition. In this context, Green-Pedersen and Otjes (Citation2017) show that party political attention to immigration is positively correlated to increases in the number of foreign born in the population. Sociological theories of realistic group conflict and the theory of ethnic competition suggest that ethnic conflict intensifies if different ethnic groups find themselves competing for key resources such as jobs and housing (Olzak Citation1994; Rydgren and Ruth Citation2011). Political parties may respond to such conflicts by emphasizing these issues in electoral competition. Therefore, we expect that a significant increase in the migrant population and economic grievances resulting from rising unemployment and major economic crises will intensify political conflict on immigration issues in electoral politics. We formulate this expectation in our first hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1: Immigration issues in the electoral arena are highly politicized, if immigration or unemployment rates are high.

Against the background of these findings, a significant leeway for political parties to mobilize or downplay the issue in election campaigns can be assumed. In the following, we therefore discuss approaches, which – referring to saliency theory of party competition (Budge and Farlie Citation1983; Robertson Citation1976) – each emphasize the importance of issue competition in elections, but arrive at different conclusions with regard to the partisan actors who dominate this competition.

The theory of issue entrepreneurship has made a specific type of party, namely challenger parties, a focus of attention (Hobolt and de Vries Citation2015). Issue entrepreneurs are defined as parties actively promoting a previously ignored issue and adopting a position which is different from the mean position in the party system (Hobolt and de Vries Citation2015: 1161). With regard to immigration issues, it is mostly radical right populist parties which are assumed to act as issue entrepreneurs and which are expected to be responsible for the politicization of such topics in the existing literature (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009; Kitschelt Citation1995; Kriesi et al. Citation2008; Mudde Citation2007). This expectation has been confirmed by Green-Pedersen and Otjes (Citation2017) on the basis of manifesto data. To test this expectation, we formulate a ‘challenger party hypothesis’.

Hypothesis 2: Immigration issues in the electoral arena are highly politicized, if radical right populist parties employ issue entrepreneurial strategies in their party manifestos.

Hypothesis 3: Immigration issues in the electoral arena are highly politicized, if moderate right parties employ issue entrepreneurial strategies in their party manifestos.

Two competing expectations about actors dominating public election debates on immigration issues can be derived from the literature. On the one hand, available research suggests that parties, which strongly emphasize an issue in their manifestos, will also play an important role in campaign debates as covered by the mass media. Research shows that despite the gate keeping role of the media, the issue emphasis strategies as found in party manifestos are translated into the news coverage of political parties (Merz Citation2017). Against this background, we expect that radical right populist parties employing issue entrepreneurial strategies in their manifestos are particularly visible in the media, provided that the issue is politicized.

Hypothesis 4: Radical right populist parties are the most visible actors in highly politicized public election debates on immigration issues.

Hypothesis 5: Mainstream parties are the most visible actors in highly politicized election debates on immigration issues.

Research design and methods

To analyze the politicization of immigration in Western Europe in national elections, we present a comparative study of 44 national election campaigns in six countries (Austria, France, Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom). Our focus is on 38 elections between the early 1990s until 2017, including elections after the ‘refugee crisis’. Our data includes every parliamentary election since the early 1990s. In addition, we include one election from the mid-1970s, which serves as a point of reference from a period when politicization of immigration is commonly assumed as being low.Footnote2 An overview of the elections covered in our analysis is provided in Table 1 in the online appendix.

This data provides a broad empirical testing ground for the hypotheses laid out above. Our sample includes those four liberal states which have been the focus of empirical research on the policies and politics of immigration in Europe, namely Germany, France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. In addition, we include two West European countries in which radical right populist parties have been particularly successful in the last two decades, namely Austria and Switzerland. As emphasized by Kriesi (Citation2016), the six West European countries covered by our study are distinct from East and South European countries with regard to the structuring of political conflict and the importance of the new ‘demarcation-integration’ cleavage. For this reason, we are cautious with generalizations of our findings.

To study the politicization of immigration, we opt for data on political contestation during election campaigns based on two different data sources that provide different windows of observation of party behavior in an election campaign. We use party manifesto data to study the strategic efforts of parties to emphasize immigration issues in an election; and we rely on quantitative data collected from mass media to analyze party behavior in public election debates.

Data on public election debates is taken from projects led by Hanspeter Kriesi and Edgar Grande (Kriesi Citation2016; Kriesi et al. Citation2012; Kriesi et al. Citation2008) and available from these authors upon request. It is based on a quantitative content analysis of newspaper articles. For each country, a quality newspaper and a tabloid newspaper were chosen.Footnote3 Articles referring to politics were selected and subsequently coded using the core sentence approach, a method developed by Kleinnijenhuis and Pennings (Citation2001). It treats ‘core sentences’, which consist of a relation between a subject (party actors) and an object (issues) as the unit of analysis. The approach allows building an issue category on immigration which comprises all statements of party actors on immigration and integration policies.

In line with the scholarly literature (De Wilde Citation2011; Hutter and Grande Citation2014), we conceptualize politicization as a multi-faceted process which includes both the public visibility of conflict (i.e., its salience) and the polarization of actors on a contentious issue. Following Hutter and Grande (Citation2014), Hutter et al. (Citation2016) and Hoeglinger (Citation2016), we measure politicization of the immigration issue in election campaigns by multiplying the salience of the issue with its degree of polarization.Footnote4 Regarding the issue of European integration, this literature shows that these two dimensions of politicization are independent and that multiplying them provides meaningful results. This is confirmed by our own data, in which both dimensions of politicization are uncorrelated (r = −0.03, t = −0.16), i.e., they measure different aspects of politicization.Footnote5 Both variables are measured at the systemic level (i.e., at the level of the overall party system) and are then multiplied to arrive at an overall indicator of politicization. Salience in this context refers to the visibility of the immigration issue in relation to other issues in an election campaign. Accordingly, the indicator is operationalized as the percentage share of core sentences on immigration compared to the number of all observations during an election. Polarization is measured as the positional variance between parties on the immigration issue. We also calculate the mean of these variables over all issues covered by our data set to arrive at benchmarks that allow distinguishing between elections with comparatively high or low levels of politicization. To measure the visibility of party families in election campaigns, we calculate the percentage share of core sentences for a party family on immigration in relation to all coded observations on the issue at a given election. Details on the operationalization of the dimensions of politicization are provided in the online appendix.

Data on the strategic behavior of parties is taken from party manifestos collected by the Manifesto Project (MARPOR). We adopt the concept of issue entrepreneurial strategies as developed by Hobolt and de Vries (Citation2015) to analyze which parties try to politicize immigration issues strategically. An issue entrepreneur is a party that promotes an issue and adopts a position that deviates from the mean position in the party system (Hobolt and de Vries Citation2015: 1168).

As the issue categories of the Manifesto Project do not include an issue category for immigration (see Lehmann and Zobel [Citation2018]: 2), we provide novel indicators for the issue attention of parties and their positions on this topic in party manifestos to measure the concept. For this purpose, we use the manifestoR corpus which enables applying text mining approaches to the manifestos covered by the MARPOR project (Lehmann et al. Citation2017; Volkens et al. Citation2017). In a first step, we use country-specific keyword lists to identify sentences addressing immigration issues. Based on this information, we calculate parties’ issue attention as the percentage share of sentences on immigration in relation to all sentences in a manifesto. In a subsequent step, we draw a sample of 20 sentences on immigration from each manifesto to manually code a party’s position. Here, we differentiate between supportive, neutral, and sceptical positions and use the mean value from these codings to arrive at a position score for each party. Positional deviance is then calculated as the distance of a party’s position from the mean position of the party system at the time of the election. Following Hobolt and de Vries (Citation2015: 1169), both variables are then multiplied to get an overall measure of a party’s entrepreneurial strategy.

To validate this method, we use data on parties’ issue attention and positions on immigration also measured in party manifestos using a crowd-sourced coding approach (Lehmann and Zobel Citation2018). As many manifestos are covered in both studies, it is possible to use this study to validate our indicators. Due to very high correlations between the indicators derived in the two studies, we conclude that our coding approach produces valid results. A detailed description of this approach and the validation procedure is provided in the online appendix.

Given the theoretical arguments presented above, we distinguish between two types of parties: mainstream and challenger parties. Challenger parties are characterized by the fact that they have not previously held political office and occupy positions which are distinct from the mean position in the party system (Hobolt and de Vries Citation2015: 251). This definition encompasses all kinds of parties from radical left and radical right party families, as well as green, regionalist, and single-issue parties, but it excludes minor moderate parties. Since we are particularly interested in the role of radical right challenger parties, we only include parties belonging to this party family in our analysis of challenger parties. These are: the Swiss Peoples Party (SVP) (Switzerland), the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), the Alliance for the Future of Austria (BZÖ) (Austria), Alternative for Germany (AfD) (Germany), UK Independence Party (UKIP) (UK), Front National (FN) (France), and Pim Fortuyn List (LPF) and Party for Freedom (PVV) (Netherlands). The SVP and FPÖ are included in the category of challenger parties although these parties have been in government, thus violating the first criterion of a challenger party. However, both parties are consistently considered as main representatives of the family of new radical right populist parties (Kitschelt Citation1995; Kriesi et al. Citation2008; Mudde Citation2007) and certainly meet the second criterion.

Mainstream parties are defined as the electorally dominant parties from the moderate part of the political spectrum (Meguid Citation2005: 348). Hence, mainstream parties typically comprise moderate-left and moderate-right parties that compete for government (De Vries and Hobolt Citation2012: 250). In line with the coding by Meguid (Citation2005) and others, we code in our sample the Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ), the British Labour Party, the French Parti Socialist (PS), the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), the Dutch Labour Party (PvdA), and the Social Democratic Party of Switzerland (SP) as belonging to the moderate left, whereas the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP), the British Conservatives, the Union for French Democracy (UDF) and the French Union for a Popular Movement (RPR/UMP), the German Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU), the Dutch Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA), the Dutch People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), and the Christian Democratic People’s Party of Switzerland (CVP) are coded as part of the moderate right. Smaller liberal parties (e.g., the German Free Democratic Party (FDP) and the British Liberal Democrats are not considered here. In line with Meguid (Citation2005), we do also not include the Swiss Liberal Party (FDP) in the category of moderate right parties. For an overview of our coding of parties see Table 2 in the online appendix.

Finally, to explore the effect of socio-economic factors on politicization, several indicators are available. Regarding immigration, we use the annual share of incoming migrants in relation to the overall population of a country from the International Migration Database provided by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) as an independent variable.Footnote6 To study the role of grievance effects, we show the results for the most conventional one, namely the annual unemployment rate in percent, as provided by the Comparative Political Data Set (CPDS) (Armingeon et al. Citation2016). We cross-checked the validity of these indicators by calculating the relationship between politicization and other socio-economic indicators, and we also explored the impact of time-lags within this relationship. These additional tests corroborate the findings presented in the empirical section below and are shown in the online appendix.

Empirical findings

In the following, we present our empirical findings in four steps. First, we show descriptive data on the dependent variable, namely politicization of immigration in national elections. Second, we investigate the relationship between politicization and socio-economic variables. Third, we analyze the impact of the strategies of challenger parties on politicization. Fourth, we explore the visibility of party families in campaign debates on immigration issues.

National patterns of politicization

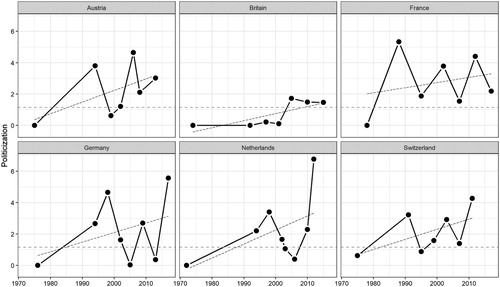

How strong is the politicization of immigration in the national electoral arena? How much variation is there over time and across countries? As shown in , immigration has become a highly politicized issue in national elections since the 1990s. We find several elections in which immigration has been a highly politicized issue in every country, except for the UK. This becomes apparent in comparison to the 1970s, when immigration issues were almost invisible in the electoral arena. As shown by Kriesi et al. (Citation2008), immigration has become the main driver for the transformation of political conflict in this period. Average values for the entire period are rather moderate, however, and values for individual dimensions indicate that politicization of immigration has been mainly driven by polarization.Footnote7

Figure 1. The politicization of immigration in national elections per country over time.

Note: Graph shows the level of politicization of the immigration issue in national elections for each country over time in national election campaigns as covered by the media. The black dashed lines indicate the linear trend. The horizontal, grey dashed lines show the mean politicization calculated over all issues in our data and serves as a benchmark to distinguish between high and low levels of politicization.

also reveals remarkable fluctuation between elections in each country. Except for the UK, we observe striking ups and downs in the development of politicization. This pattern is most pronounced in France where highly politicized elections in 1988, 2002 and 2012 were followed by moderate levels of politicization in subsequent elections in 1995, 2007 and 2017. Moreover, there is considerable variation across countries. Among the six countries included in our sample, the UK is a clear outlier. Immigration has been a low key issue in national elections for most of the time, but politicization has been increasing to a moderate level since the mid-2000s not the least due to the Conservative Party’s efforts to acquire issue ownership while in opposition (Dennison and Goodwin Citation2015). The other countries witnessed pronounced peaks of politicization in the 1990s, although with significant differences in timing. Elections after 2010 are often characterized by a sharp increase in the politicization of immigration. The Dutch election in 2012 and the German election in 2017, where we measure the highest values in our sample, clearly stand out.

Socio-economic factors and grievances

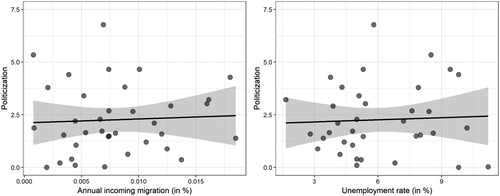

Is the politicization of immigration issues in national elections due to ‘objective’ factors such as the number of incoming migrants and economic grievances? In the left panel of , we take the annual change in the number of immigrants entering a country as an indicator for the size of the ‘objective pressure’ exercised by immigration and relate it to the level of politicization of immigration issues in national elections. Evidently, the two variables are hardly correlated (r = 0.10; t = 0.58). These results are in line with the conclusions of Van der Brug et al. (Citation2015: 192) that no systematic relationship exists between politicization of immigration and immigration-related variables such as the number of immigrants living in a country, the number of immigrants entering the country, or the composition of the immigrant population. Neither is politicization driven by economic grievances. As we can see in the right panel of , no positive correlation exists between the politicization of immigration and unemployment (r = 0.05; t = −0.29). This also holds for other economic variables on which data is available in Armingeon et al. (Citation2016). The results of these analyses as well as a regression model with socio-economic and issue entrepreneurship variables are shown in the online appendix.

Figure 2. Relationship between politicization and socio-economic factors.

Note: The left panel shows the level of politicization of immigration in relation to the annual share of incoming migrants as a percentage of the total population of a country. The right panel shows the relationship between the politicization of immigration and the unemployment rate in the country. Black lines show the linear fit, grey areas show the confidence interval.

Taken together, these analyses contradict the hypothesis on the importance of socio-economic factors (H1). Politicization is neither correlated with ‘objective’ properties of immigration nor with economic grievances of the native population. These findings add to the insights of studies which emphasize the importance of political factors, and particularly political parties, for politicizing immigration issues (see, e.g., Kitschelt [Citation1995]; Messina [Citation2007]; Van der Brug et al. [Citation2015]).

The role of issue entrepreneurship of radical right challenger parties

The increase in immigration in Western Europe has been accompanied with the surge of anti-immigration groups, in particular radical right populist parties (Messina Citation2007: 54–96). The organization of this ‘nativist backlash’ and its political relevance varies considerablly among the six countries in our sample. France and the Netherlands are characterized by the emergence of electorally successful new radical right populist parties; in Austria and Switzerland, two established moderate right parties radically changed their programmatic profiles and adopted restrictive positions on immigration issues in the 1990s; whereas in Germany and the UK, efforts to establish a radical right populist party at the national level have not been successful in most of the period covered by our study. Hence, radical right populist parties have not been relevant in all the countries included in our sample. Are there differences in the strategic emphasis of immigration issues between party families in their election manifestos? And how are these strategies related to the politicization of immigration issues in public election debates?

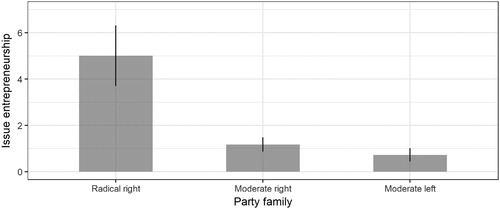

shows the efforts of party families (moderate right, moderate left, and radical right populist parties) to emphasize immigration issues in their manifestos. Comparing issue entrepreneurship between these three groups reveals significant differences. On average, radical right populist parties put considerably more effort in politicizing immigration issues than other parties (mean = 5.01; sd = 3.17). In contrast, parties of the moderate right (mean = 1.17; sd = 1.13) and parties of the moderate left (mean = 0.72; sd = 0.99) show much lower average levels of issue entrepreneurship. The high average value of radical right populist parties is due to higher scores on both components of issue entrepreneurship: Radical right populist parties put more emphasis on the issue on average (mean = 6.03) than parties of the moderate right (mean = 3.10) and moderate left (mean = 2.08). Moreover, they also deviate more strongly from the mean position in the party system (mean = 0.79) than parties of the moderate right (mean = 0.36) and moderate left (mean = 0.32). These findings provide no evidence that moderate right parties play a prominent role as strategic drivers of immigration issues in the electoral arena as suggested by parts of the scholarly literature (e.g., Bale [Citation2008]; Green-Pedersen and Krogstrup [Citation2008]).

Figure 3. Issue entrepreneurship on immigration issues by party family.

Note: Issue entrepreneurship is measured as the product of the salience a party puts on immigration issues and its positional deviance from the mean position in the party system based on party manifesto content. Bars indicate the mean values for each party family. Spikes represent the 95% confidence interval.

These results indicate that immigration issues are of greater strategic importance for radical right populist parties in election campaigns compared to other party families. However, this does not imply that these efforts necessarily lead to the politicization of immigration issues in public election debates. To explore the role of radical challenger parties and mainstream parties of the moderate left and moderate right in this regard, shows the results of regression analyses which treat the level of politicization as the dependent variable and issue entrepreneurship of party families as the main independent variables. Model 1 shows that issue entrepreneurship of radical right populist parties is positively and statistically significantly related to the level of politicization in election campaigns, while this is not the case for mainstream parties. In the former case the increase in politicization levels is, in fact, quite sizeable. Politicization ranges from a below-average value of 1.8 when issue entrepreneurship of radical right populist parties is at the lower quartile to an above-average value of 3.0 when it is at the upper quartile. This difference corresponds to 12% of the range of politicization values. Thus, we do find evidence for our ‘challenger party hypothesis’ (H2), but not for the ‘moderate right party hypothesis’ (H3). Politicization of immigration issues is driven by issue entrepreneurial strategies of radical right populist parties rather than by efforts of other party families.Footnote8

Table 1. Linear regression models of politicization of immigration issues in national elections.

To explore this finding in more detail, we additionally check whether the association remains significant when controlling for the vote share of radical populist right parties. That is indeed the case as Model 2 shows. The fact that the coefficient for the vote share of these parties is close to zero and fails to reach statistical significance, provides further evidence that it is not simply the presence of radical right populist parties that fuels the politicization of immigration, but their strategic focus on immigration issues.Footnote9

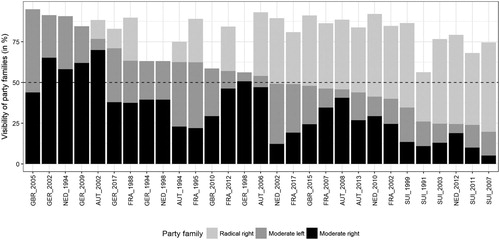

The visibility of different party families in debates on immigration

The strategic impact of radical challenger parties on politicization must not be equated with their visibility in public election debates. In the last step of our analysis, we explore the actor composition in mass mediated election debates with above average levels of politicization on immigration. This allows us to uncover the relative importance of party families in public election debates. shows the results for the 29 elections with high levels of politicization. Our analysis reveals that moderate mainstream parties are the most visible actors in more than half of these elections. Taken together mainstream parties from the moderate left and moderate right account for more than 50 percent of all coded core sentences on the issue in these elections. This even holds true for elections in which mainstream parties were confronted with a strong challenger party from the radical right as it was the case in the 2017 German election, where more than 70 percent of all coded statements can be attributed to the moderate left (SPD) or the moderate right (CDU/CSU). Moreover, the visibility of mainstream parties is not positively related to the mobilizing efforts of these parties as measured in their manifestos: We observe no significant correlation between issue entrepreneurship and visibility for parties from the moderate right (r = 0.22, t = 1.16) and the moderate left (r = −0.19, t = 1.01). Thus, in line with Hypothesis 5, and similar to the findings reported by Van der Brug et al. (Citation2015), we find that mainstream parties are very visible actors in politicized election debates on immigration, irrespective of the campaign strategy they pursue in their manifestos.

Figure 4. Visibility of party families in politicized election debates on immigration.

Note: Stacked bars represent the relative visibility of a party family in relation to other party families in campaign debates on immigration issues as covered by the media. The dashed horizontal line allows identifying elections where moderate mainstream parties account for more than half of all coded observations. Only debates where the politicization of immigration is above our benchmark are reported. Bars are sorted by the joint visibility of mainstream parties.

This is not to say that challenger parties are always marginalized by mainstream parties in these debates. In line with Hypothesis 4, also shows elections in which radical right populist parties are highly visible. Most evidently, this holds for Switzerland where the SVP is by far the most visible party on immigration issues in a number of elections. The Swiss SVP is a special case, however. As it has been in government in the entire period it is not a typical example of a challenger party. More instructive are the French election in 2002 and the Dutch election in 2012, which show that new non-governing challenger parties can also dominate election debates on immigration. Moreover, in contrast to the findings for moderate mainstream parties, we find a positive and significant relationship between issue entrepreneurship and visibility for radical right populist parties (r = 0.58, t = 3.71). In sum, these results provide mixed support for both hypotheses on the visibility of party families in politicized election debates on immigration issues.

Conclusion

Our empirical analysis provides mixed support for the arguments advanced in the scholarly literature on the politicization of immigration in Europe. Three conclusions stand out. First, our analysis confirms earlier findings which observe a significant increase in politicization of immigration issues since the 1990s in Western Europe for the electoral arena (Kriesi et al. Citation2012; Messina Citation2007; Van der Brug et al. Citation2015). Immigration has become a highly controversial issue in national election contests. We found evidence for strong politicization in every country we analyzed, but we also found remarkable variation over time and across countries. The extreme fluctuation in the intensity of political conflict over immigration within countries is one of the most puzzling features of politicization of this issue. The marked peaks in politicization and the consistently high polarization values suggest that the potential for politicization has been huge in the entire period, but this potential has not been fully exploited in every election thus far.

Second, politicization is not correlated with socio-economic factors such as the share of immigrants in a country or the level of unemployment. Therefore, our first hypothesis (H1) must be rejected. It is certainly true that the existence of some immigration has been a necessary precondition for political mobilization, but there is no direct relationship between the intensity of political conflict and socio-economic grievances. This is not to say that socio-economic factors are entirely irrelevant in our context; but they do not translate directly into manifest political conflict among political parties in the electoral arena.

Third, previous findings on the political actors responsible for the politicization of immigration in the electoral arena must be qualified. Our results support arguments which claim that the issue entrepreneurship of radical right populist challenger parties leads to higher levels of politicization. Contrary to some scholarly expectations, we found no similar effect for moderate mainstream parties. This is not to say that the strategic efforts of challenger parties to emphasize the immigration issue in their manifestos necessarily results in high visibility of these parties in public election campaigns. Our analysis of campaign debates suggests that both radical right challenger parties and mainstream parties can dominate these debates. In public debates, high levels of politicization of immigration issues can also result from the reactions by mainstream parties on challenger parties. Some recent studies corroborate this mechanism. On the one hand, mainstream parties are found to be particularly sensitive to the actions of other parties when it comes to the salience they put on an issue (Green-Pedersen and Mortensen Citation2015). On the other hand, they frequently adapt their positions in response to challenger parties and their electoral gains (Abou-Chadi Citation2016; Meijers Citation2017; Van Spanje Citation2010). Nevertheless, our findings invite more research scrutinizing the behavior of mainstream parties to strategic actions of radical right challengers and its effect on politicization.

Summing up, political conflict over immigration follows a ‘political logic’ (Messina Citation2007) and must be attributed to parties and party competition rather than to ‘objective pressures’ in Western Europe. The fact that political parties have significant room for strategic manoeuvring regarding immigration issues makes it even more important to understand what they make of these opportunities.

RJPP_A_15319069_ Appendix

Download MS Word (765.5 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Edgar Grande is Founding Director of the Center of Civil Society Research at the Social Science Center in Berlin (WZB).

Tobias Schwarzbözl is a PhD candidate at the Ludwig-Maximilians-University (LMU) Munich.

Matthias Fatke is a postdoctoral researcher at the Ludwig-Maximilians-University (LMU) Munich.

Notes

1. It is also argued that mainstream parties in opposition are especially likely to emphasise new issues (Van de Wardt Citation2015). We only find modest evidence for this expectation in our data, which is presented in the online appendix.

2. In the French case, we considered the first round of the presidential elections, because these elections are considered as being the most important national elections. Data on the election for the 1970s is only available for the parliamentary election in 1978. The election in 1988 is the first presidential election included in our sample. In the Austrian case, the snap election of 1995 is not included.

3. Newspapers included are: Die Presse & Kronenzeitung (Austria); Le Monde & Le Parisien (France); Süddeutsche Zeitung & Bild (Germany); NRC Handelsblad & Algemeen Dagblad (Netherlands); The Times & The Sun (UK); Neue Zürcher Zeitung & Blick (Switzerland).

4. We do not include ‘actor expansion’, a third dimension of politicization (see Hutter and Grande Citation2014), in our analysis because it is inherently associated with our main explanatory variable, namely issue entrepreneurship of challenger parties.

5. The empirical analysis of Van der Brug et al. (Citation2015: 192) also shows for immigration issues that salience and polarization are not correlated.

6. http://stats.oecd.org/viewhtml.aspx?datasetcode=MIG&lang=en# (accessed 20.06.2018). No reliable information on the number of incoming migrants for France and for Germany in 2017 is available. Hence, these elections are excluded from analyses on the role of socio-economic factors.

7. Details on the level of politicization as well as additional information on the two sub-dimensions of the concept of politicization are provided in the online appendix.

8. The finding of a strong and significant coefficient for issue entrepreneurship of radical right populist parties remains the same, when we estimate, as a robustness test, robust standard errors or log-transform the skewed dependent variable. When including other party families in the analysis like green parties or liberals, we also find no significant associations for these actors, while the coefficient for radical right populist parties is still significant. Moreover, we find no evidence that the coefficient of issue entrepreneurship of one of our party families is conditional on the behavior of others as all interaction effects between issue entrepreneurship of different party families fail to reach statistical significance.

9. The online appendix, moreover, presents separate regression models with salience and polarization as dependent variables. It becomes evident that relationships with each constituent variable of politicization differ. Therefore, we conclude that politicization is indeed a distinct phenomenon and one cannot expect to extend explanations of politicization to its constituent elements.

References

- Abou-Chadi, T. (2016) ‘Niche party success and mainstream party policy shifts – How green and radical right parties differ in their impact’, British Journal of Political Science 46(2): 417–36. doi: 10.1017/S0007123414000155

- Armingeon, K., Isler, C., Knöpfel, L., Weisstanner, D. and Engler, S. (2016) Comparative Political Data Set 1960–2014, Bern: Institute of Political Science, University of Berne.

- Bale, T. (2008) ‘Turning round the telescope. Centre-right parties and immigration and integration policy in Europe’, Journal of European Public Policy 15(3): 315–30. doi: 10.1080/13501760701847341

- Budge, I. and Farlie, D. (1983) ‘Party competition – selective emphasis or direct confrontation? An alternative view with data’, in H. Daalder and P. Mair (eds.), Western European Party Systems. Continuity and Change, London: Sage, pp. 267–305.

- Dennison, J. and Goodwin, M. (2015) ‘Immigration, issue ownership and the rise of UKIP’, Parliamentary Affairs 68(1): 168–87. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsv034

- De Vries, C.E. and Hobolt, S.B. (2012) ‘When dimensions collide: the electoral success of issue entrepreneurs’, European Union Politics 13(2): 246–68. doi: 10.1177/1465116511434788

- De Wilde, P. (2011) ‘No polity for old politics? A framework for analyzing the politicization of European Integration’, Journal of European Integration 33(5): 559–75. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2010.546849

- Dolezal, M. and Hellström, J. (2016) ‘The radical right as driving force in the electoral arena?’, in S. Hutter, E. Grande and H. Kriesi (eds.), Politicising Europe: Integration and Mass Politics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 156–80.

- Ferrera, M. and Pellegata, A. (2018) ‘Worker mobility under attack? Explaining labour market chauvinism in the EU’, Journal of European Public Policy 25(10): 1461–80. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2018.1488886

- Green-Pedersen, C. and Krogstrup, J. (2008) ‘Immigration as a political issue in Denmark and Sweden’, European Journal of Political Research 47(5): 610–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2008.00777.x

- Green-Pedersen, C. and Mortensen, P.B. (2015) ‘Avoidance and engagement: issue competition in multiparty systems’, Political Studies 63(4): 747–64. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12121

- Green-Pedersen, C. and Otjes, S. (2017) ‘A hot topic? Immigration on the agenda in Western Europe’, Party Politics (Online first): 1–11.

- Hainmueller, J. and Hopkins, D.J. (2014) ‘Public attitudes toward immigration’, Annual Review of Political Science 17(1): 225–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-102512-194818

- Hobolt, S.B. and de Vries, C.E. (2015) ‘Issue entrepreneurship and multiparty competition’, Comparative Political Studies 48(9): 1159–85. doi: 10.1177/0010414015575030

- Hoeglinger, D. (2016) Politicizing European Integration, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2009) ‘A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: from permissive consensus to constraining dissensus’, British Journal of Political Science 39(1): 1–23. doi: 10.1017/S0007123408000409

- Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2018) ‘Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage’, Journal of European Public Policy 25(1): 109–35. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279

- Hutter, S. and Grande, E. (2014) ‘Politicizing Europe in the national electoral arena: a comparative analysis of five West European countries, 1970–2010’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 52(5): 1002–18.

- Hutter, S., Grande, E. and Kriesi, H. (eds.) (2016) Politicising Europe. Integration and Mass Politics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kitschelt, H. (1995) The Radical Right in Western Europe. A Comparative Analysis, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Kleinnijenhuis, J. and Pennings, P. (2001) ‘Measurement of party positions on the basis of party programmes, media coverage and voter perceptions’, in M. Laver (ed.), Estimating the Policy Positions of Political Actors, London: Routledge, pp. 162–82.

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S. and Frey, T. (2008) West European Politics in the Age of Globalization, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Dolezal, M., Helbling, M., Höglinger, D., Hutter, S. and Wüest, B. (2012) Political Conflict in Western Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, H. (2016) ‘The politicization of European integration’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 54(S1): 32–47.

- Lehmann, P., Matthieß, T., Merz, N., Regel, S. and Werner, A. (2017) Manifesto Corpus. Version: 2017–2, Berlin: WZB Berlin Social Science Center.

- Lehmann, P. and Zobel, M. (2018) ‘Positions and saliency of immigration in party manifestos: a novel dataset using crowd coding’, European Journal of Political Research 57(4): 1056–83. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12266

- Meguid, B.M. (2005) ‘Competition between unequals: the role of mainstream party strategy in niche party success’, American Political Science Review 99(3): 347–59. doi: 10.1017/S0003055405051701

- Meijers, M.J. (2017) ‘Contagious Euroscepticism: the impact of Eurosceptic support on mainstream party positions on European integration’, Party Politics 23(4): 413–23. doi: 10.1177/1354068815601787

- Merz, N. (2017) ‘Gaining voice in the mass media: the effect of parties’ strategies on party–issue linkages in election news coverage’, Acta Politica 52(4): 436–60. doi: 10.1057/s41269-016-0026-9

- Messina, A.M. (2007) The Logics and Politics of Post-WWII Migration to Western Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Meyer, S. and Rosenberger, S. (2015) ‘Just a shadow? The role of radical right parties in the politicization of immigration, 1995–2009’, Politics and Governance 3(2): 1–17. doi: 10.17645/pag.v3i2.64

- Mudde, C. (2007) Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Olzak, S. (1994) The Dynamics of Ethnic Competition and Conflict, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Robertson, D. (1976) A Theory of Party Competition, London: Wiley.

- Rydgren, J. and Ruth, P. (2011) ‘Voting for the radical right in Swedish municipalities: social marginality and ethnic competition?’, Scandinavian Political Studies 34(3): 202–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9477.2011.00269.x

- Schattschneider, E.E. (1975 [1960]) The Semi-Sovereign People: A Realist´s View of Democracy in America, Hinsdale, Illinois: The Dryden Press.

- Steenbergen, M.R. and Scott, D.J. (2004) ‘Contesting Europe? The salience of European integration as a party issue’, in G. Marks and M.R. Steenbergen (eds.), European Integration and Political Conflict, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 165–92.

- Van de Wardt, M. (2015) ‘Desperate needs, desperate deeds: why mainstream parties respond to the issues of niche parties’, West European Politics 38(1): 93–122. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2014.945247

- Van der Brug, W., D’Amato, G., Ruedin, D. and Berkhout, J. (2015) The Politicisation of Migration, London: Routledge.

- Van Spanje, J. (2010) ‘Contagious parties: anti-immigration parties and their impact on other parties’ immigration stances in contemporary Western Europe’, Party Politics 16(5): 563–86. doi: 10.1177/1354068809346002

- Volkens, A., Lehmann, P., Matthieß, T., Merz, N., Regel, S. and Weßels, B. (2017). The Manifesto Data Collection, Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR): Version 2017b. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).