?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In the past decade, policymakers have increasingly used behaviourally informed policies, including ‘nudges,’ to produce desirable social outcomes. But do people actually endorse those policies? This study reports on nationally representative surveys in five countries (Belgium, Denmark, Germany, South Korea, and the US) carried out in 2017/2018. We investigate whether people in these countries approve of a list of 15 nudges regarding health, the environment, and safety issues. A particular focus is whether trust in public institutions is a potential mediator of approval. The study confirms this correlation. We also find strong majority support of all nudges in the five countries. Our findings in general, and about trust in particular, suggest the importance not only of ensuring that behaviourally informed policies are effective, but also of developing them transparently and openly, and with an opportunity for members of the public to engage and to express their concerns.

Introduction

Background

In regulation and public policy in general, behaviourally informed initiatives, influenced by behavioural economics, have become a pervasive approach to public policy (Halpern Citation2015; Ruggeri Citation2018; Sunstein Citation2013; Troussard and van Bavel Citation2018). In particular, the last several years have seen a great deal of work on ‘nudges,’ standardly defined as public or private interventions that steer people in particular directions but that also allow them to go their own way (Thaler and Sunstein Citation2008). A reminder is a nudge; so is a warning. A GPS nudges; a default rule nudges. Mandatory disclosure of relevant information (about the risks of smoking or the costs of borrowing) counts as a regulatory nudge. Save More Tomorrow plans, allowing employees to sign up to give some portion of their future earnings to pension programmes, are nudges (e.g., Benartzi Citation2012); so are Give More Tomorrow Plans, allowing employees to sign up to give some portion of their future earnings to charities (Breman Citation2011). A recommendation is a nudge. A criminal penalty, a civil fine, a tax, and a subsidy are not nudges, because they impose significant material incentives on people’s choices.Footnote1

In many nations, public officials have been drawn to nudges, seeing them as an additional tool in the regulatory repertoire, with potentially low costs and high benefits. In 2009, the United Kingdom created a Behavioural Insights Team, focused largely on uses of nudges, and choice architecture, to improve social outcomes; its results have been impressive (Halpern Citation2015). Nudges play a large role in regulatory initiatives in the United States in multiple areas, including environmental protection, financial regulation, highway safety regulation, anti-obesity policies, and education (Sunstein Citation2013). In 2014, the United States created its own Social and Behavioral Sciences Team, now called the Office of Evaluation Sciences. With an emphasis on poverty and development, the World Bank devoted its entire 2015 report to behaviourally informed tools, with a particular focus on nudging (World Bank Citation2015). Also in 2015, President Obama issued a historic Executive Order, still in effect, on uses of behavioural sciences in federal agencies, calling for attention to the assortment of tools standardly associated with nudging (White House Citation2015). Behavioural science teams can be found in dozens of countries, including Australia, the Netherlands, Canada, Ireland, Denmark, Mexico, Germany, and Qatar. There is a great deal of activity elsewhere, particularly in the regulatory domain (OECD Citation2017; Ruggeri Citation2018).

The reason for the mounting interest should not be obscure. Nations would like to make progress with tools that actually work and that do not cost a great deal. If governments can achieve regulatory goals with instruments that impose minimal burdens and that preserve freedom of choice, they will take those tools seriously. In domains that include savings policy, climate change, public health, poverty, and health care, among others, behaviourally informed approaches (including default rules and information disclosure) have attracted considerable attention, and often led to concrete reforms (Halpern Citation2015; Jones et al. Citation2014; Whitehead et al. Citation2017).

Worldwide, governments increasingly embrace nudges as a way of addressing a wide range of policy challenges. This holds true for policies covering a wide array of consumer decisions such as healthy food choices (Bauer and Reisch Citation2019), quitting smoking (Halpern et al. Citation2015), drinking alcohol (Brooks Citation2015), overeating (Arno and Thomas Citation2016), and organ donation (Rockloff and Hanley Citation2014), as well as environmentally relevant decisions such as switching to green energy (Sunstein and Reisch Citation2014). Nudging has also been applied to influence decisions of patients (e.g., uptake of vaccinations), commuters (e.g., using public or active transport), employees (e.g., pension plans) as well as citizens (e.g., voter turnout, uptake of higher education).Footnote2 The domain of health may be the most studied to date,Footnote3 followed by behavioural interventions to support more sustainable choices (Szaszi et al. Citation2017).

There is mounting evidence that these behavioural policies are often quite effective. One study of the relative effectiveness of such instruments (Bernartzi et al. Citation2017) found that the impact-to-cost ratio of various nudges is significantly higher than the ratio for traditional policies (such as monetary incentives). At the same time, the effectiveness of nudges is not the only issue relevant to whether they will be, or even should be, implemented in practice. As for other regulatory interventions, we need to know whether they have benefits in excess of costs (Sunstein Citation2018a). In democratic nations, it is also important to know whether members of the public will endorse such instruments. It is safe to assume that public concerns will be less pronounced when people trust their government in general and the diverse public institutions that are implementing those nudges in particular.

Some evidence suggests that the acceptability of regulatory interventions depends, in part, on their perceived effectiveness (suggesting that effectiveness is causally related to public approval) and also the inferred motivations of the choice architect (Bang et al. Citation2018). More concretely, an experimental study (Osman et al. Citation2018) has found that scientists proposing nudges are deemed more trustworthy than a government working group. In the same study, trust in hypothetical nudges proposed by the former was higher than in nonhypothetical interventions proposed by the latter (ibid.). Reflecting both democratic theory and the increasing evidence of such studies, it has been suggested that regulatory nudging should develop a more bottom up approach involving greater feedback and more engagement with citizens (John Citation2018) – an important point to which we will return.

Prior studies

In the past years, several studies have been published on public acceptance of regulatory nudges (Arad and Rubinstein Citation2018; Bang et al. Citation2018; Branson et al. Citation2012; Bruns et al. Citation2018; Diepeveen et al. Citation2013; Felsen et al. Citation2013; Hagman et al. Citation2015; Jung and Mellers Citation2016; Junghans et al. Citation2015, Citation2016; Osman et al. Citation2018; Reisch and Sunstein Citation2016; Sunstein et al. Citation2018; Tannenbaum et al. Citation2017). This literature has explored:

whether people in different countries endorse nudges in policy fields such as environment, health, and safety, or as policy instruments in general;

whether they prefer certain types of nudges (i.e., educative or noneducative nudges, pro-self or pro-social nudges, and genuine or hypothetical nudges) and whether it matters who proposes their use (sender effect of the choice architect);

whether identifiable political values are predictive of support for nudging and nudges;

whether individual, psychological, and social factors influence levels of support.

With respect to the first question, nationally representative surveys have found that strong majorities of citizens in diverse countries approve of most of the nudges presented to them (e.g., Hagman et al. Citation2015; Jung and Mellers Citation2016; Reisch and Sunstein Citation2016; Sunstein et al. Citation2018). Comparing the approval rates of 15 environmental, safety, and health nudges in 14 countries worldwide, we found that these countries could roughly be grouped into three distinct categories:

The ‘principled pro-nudge nations’: These are mostly industrialized Western democracies (including our current study countries Germany and the US), where strong majorities approve of nudges, at least when they are seen to fit with the interests and values of most citizens and do not have illicit ends.

The ‘nudge enthusiasts’: A small group of nations where overwhelming majorities approve of nearly all nudges (South Korea and China).

The ‘cautiously pro-nudge nations’: A group of nations (including Denmark, Hungary, and Japan) that generally show majority approval on average, but also markedly lower approval rates (Sunstein et al. Citation2018).

The national differences identified in these and other studies (Hagman et al. Citation2015) are both instructive and important. They tell us something about different political cultures, which is interesting in its own right. They also provide information about whether citizens will provide a green light or a red light to certain kinds of regulatory interventions. In democratic nations, of course, officials will be interested in whether citizens support or reject possible policies. The same is also true of nondemocratic nations. Without making strong claims about the wisdom of crowds, we might also think that the judgments of citizens, even in a survey setting, provide relevant information about whether policies actually deserve support. Of course answers to survey questions should not be decisive. But if citizens generally favour or disfavour certain policies, their views are entitled to respectful attention.

As to the second question, there is some preliminary evidence of a general preference for educative nudges (even though noneducative nudges often receive strong majority approval). At least in the United States, people have been found to prefer regulatory nudges, such as disclosure of information, that target deliberative and conscious ‘System 2’ decision processes, as compared to ‘System 1’ nudges (Jung and Mellers Citation2016; Sunstein Citation2016a, Citation2016b), such as default rules, that try to influence automatic, non-deliberative decisions (following the model elaborated by Kahneman Citation2011). In the same vein, people have been found to prefer regulatory nudges that target processes of which they are aware (e.g., educational campaigns) over those that target passive processes, such as automatic enrolment or defaults (Jung and Mellers, Citation2016; Reisch and Sunstein Citation2016; Sunstein Citation2016b; Sunstein et al. Citation2018). One study (Osman et al. Citation2018) finds that transparent nudges tend to be judged to be more ethical than opaque ones. Similar concerns might be at play when people prefer nudges that educate consumers about choices (e.g., calorie labels on foods) over those that steer choices through use of choice architecture in cafeterias (Arad and Rubinstein Citation2018; Felsen et al. Citation2013). (Recall, however, that even if educative nudges are preferred over noneducative ones, both tend to receive majority support.)

At the same time, recent studies suggest that people’s preferences as between educative and noneducative nudges are malleable, and that the results of prior studies are influenced by the method of evaluation and the type of information presented. Davidai and Shafir (Citation2018) found that while people exhibit a preference for educative over noneducative nudges in joint evaluation (i.e., traditional policies and nudges presented together), they endorse both kinds of nudges about equally in separate evaluation (i.e., nudges are evaluated on their own merits). In addition, people are moved toward greater acceptance of noneducative nudges if they are given information suggesting that those interventions are especially effective. Davidai and Shafir (Citation2018: 3) suggest that previous research – largely based on separate evaluation without effectiveness information – has therefore ‘inadvertently exaggerated the preference for deliberate policy interventions over ones that target non-deliberative processes.’

For policy makers, it would be helpful to know not only if people approve of regulatory nudges, but also who does, i.e., which individual values, dispositions, attitudes, and world-views lead to (dis)approval of these instruments. Socio-ecological models (e.g., Bronfenbrenner Citation1986) suggest that attitudes will depend both on individual factors (i.e., knowledge, attitudes, behaviours, and personality traits) and on factors in the respondents’ interpersonal, community, and wider socio-political environment (i.e., trust in governmental institutions, environmental threats, general wealth, and health of the population). The societal, cultural, and political systems in which people are embedded and the social influences to which they are exposed affect their goals, their beliefs and attitudes, their outlook to the future, their adherence to social norms, and whether they trust other people and their government.Footnote4

With respect to the third and fourth question above, little evidence – at least outside the US – has yet surfaced about which population groups support nudging and which factors shape those attitudes. In one of the few representative studies looking into these factors, Jung and Mellers (Citation2016) found that Americans who show greater empathetic concern tended to support (the presented list of) nudges. At the same time, individualists and conservatives were less likely to support the tested nudges. Reactant people and people with a high need for control opposed noneducative nudges only. Hagman et al. (Citation2015) have found that in Sweden and the US, individuals with an individualistic worldview were less likely to approve of nudges, while people prone to analytical thinking perceived nudges as less intrusive to personal freedom of choice.

In earlier studies (Reisch and Sunstein Citation2016; Sunstein et al. Citation2018), we offered preliminary explorations of the influence of individual factors such as socio-demographics and political attitudes on approval in Europe and in countries worldwide. While some correlations between individual factors and approval rates were found, they differed rather unsystematically between the nudges and between the different countries. Overall, the results were inconclusive, with exceptions for gender (women did systematically score higher in the approval rates than men in almost all nudges and almost all countries), age (operating differently for different nudges), and political attitudes (supporters of leftist parties were slightly more in favour of the tested nudges than conservatives).

On the basis of the same nationally representative surveys, we looked deeper into which population groups within four selected and easily comparable countries (Denmark, Hungary, Italy, and the United Kingdom) support nudges and why (Loibl et al. Citation2018). We used individual, household, and geographic characteristics as predictors of nudge approval, and the count of significant predictors as measures of controversy. In brief, lower approval rates of nudges in Denmark and Hungary were reflected in higher controversy about noneducative nudges, whereas the United Kingdom and Italy were marked by greater controversy about educative nudges, despite relatively high approval rates. High-controversy nudges tended to be associated with current public policy concerns, for example, meat consumption – a point supportive of the general view that substantive concerns, rather than nudging itself, drive people’s evaluations (Tannenbaum et al. Citation2017).

The present study

For the present study, we collected additional data in four of our study countries (Germany, Denmark, South Korea, and the US) in 2018. We chose one nation from each of the three categories of nudge endorsement, one from three different cultural clusters (Sunstein et al. Citation2018), and added comparable survey data from the Flemish part of Belgium.Footnote5 In addition to the 15 nudges and the social-demographic variables, we asked participants to answer a large questionnaire including anthropometrics (to calculate Body Mass Index), lifestyle factors, consumption of specific products (alcohol, smoking, and meat), employment status and type, subjective health status and health satisfaction, social trust and trust in institutions, concerns about the environment, world-views and thinking styles (i.e., future outlook, belief in free markets, political attitudes, risk aversion), and several more variables. We speculated that these variables could help explain differences between social groups as well as across nations.

In particular, we were interested in the psychological concepts of social and institutional trust. These concepts have since long been regarded as important indicators of the strength and quality of societies, communities, and governments across the world. Validated measurement items as well as prevalence estimates are available for most countries worldwide -- for instance, from the World Values SurveyFootnote6 data set (Inglehart et al. Citation2014). In our study, we hypothesized that people who have a high trust in public institutions would be more willing to accept government nudging in our tested areas. We also speculated that strong believers in the free market might be less inclined to do so.

Beyond this focus on trust in government, we tested other variables. The influence of environmental concern on attitudes and behaviour has been studied in depth and in international contexts (e.g., Franzen and Vogl Citation2013; Poortinga et al. Citation2004). It seems intuitive that people who have a marked concern regarding the environmentFootnote7 will endorse environmental regulation in general and ‘green nudges’ in particular.Footnote8 For similar reasons, we speculated that a fragile individual health status and high health concerns for oneself and others might be positively correlated with approval of health nudges. A recent study (Bhawra et al. Citation2018) reported that a higher Body Mass Index (BMI) was positively correlated with support for menu labelling policies – which is Nudge 1 in our list of 15 nudges. We also explored the influence of consumption habits (i.e., meat, tobacco, alcohol, and mobility) on the approval of the respective nudges.

We also wanted to see whether approval rates of nudging depend on political attitudes. Earlier US studies have suggested that in a bipartisan system, Republicans are somewhat less approving of certain nudges than Democrats (Jung and Mellers Citation2016; Sunstein Citation2016a). However, this is likely to be an artifact of the relevant policy domains in which the nudges are imposed, rather than a general judgment about nudges as such (Tannenbaum et al. Citation2017). In our earlier surveys, we had found no systematic correlation along approval and party affiliations (Reisch and Sunstein Citation2016; Sunstein et al. Citation2018). Finally, we speculated that risk aversion, job satisfaction, and subjective well-being might have an impact on approval.

In a nutshell: With this study, we aimed to understand why people in selected countries approve or disapprove of a set of 15 nudges, mainly in the field of environmental protection and health. Regarding explanatory variables, our principal focus is on trust in governmental institutions. By replicating the surveys that have been conducted in 2015, 2016, and 2017 (Reisch and Sunstein Citation2016; Sunstein Citation2016a; Sunstein et al. Citation2018), we also test the robustness of our earlier results regarding approval rates and socio-demographics, in particular the influence of gender. Finally, by compiling all available data on nudge approval rates from the three waves in overall 16 countries, we hope to shed light on the acceptance of nudges.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. We first present the methodology by describing the samples, the survey, the variables, and the multi-step statistical analysis. We then show the results in the five countries, emphasizing above all the relationship between the trust variables and approval rates. We also compare the present results with earlier survey waves in selected countries and provide an overall view of all surveys of all our respective empirical studies. We discuss the results and limitations of our study and conclude with comments on implications for nudging research and behavioural public policy. Our main emphasis, based on our findings about trust, involve the importance of public participation and consultation with respect to behaviourally informed policies.

Methods

Sampling

We employed an online representative survey in five countries, covering the three country categories sketched above: the U.S. and GermanyFootnote9, South Korea, and Denmark. As a new country in our database, we included (the Flemish part of) Belgium.Footnote10 To ensure the same approach and level of quality of those surveys that we did not conduct ourselves, we developed a systematic Standard Operation ProcedureFootnote11 for the external partners to follow. The US market research firm QualtricsFootnote12 conducted the survey during six weeks between January and February 2018. We collaborated closely with Qualtrics, before, during, and after field time. Most importantly, we had permanent access to the survey data and could monitor the survey and the fulfilment of quota on a daily basis all through the survey. provides an overview of the different samples and sampling of this survey.

Table 1. Samples and sampling in the different countries: Types of representativeness and methodology.

Survey instrument

We employed a questionnaire with 54 questions including: socio-demographic variables; the list of 15 nudges in a randomized order as employed in our earlier studies (Reisch and Sunstein Citation2016: 312–313); a measure of political attitudes; questions measuring psychological constructs (such as social trust and trust in government, perceived freedom of choice) as well as variables describing individual factors (such as perceived individual health, environmental concern, social trust as well as consumption practices such as smoking and drinking habits). The complete survey instrument is documented in Online Appendix A1. Online Appendix A2 shows the descriptive statistics of the underlying data set and the full list of variables employed.

The questionnaire was fully structured, and respondents were required to follow them as provided. Each item was shown on a single screen. Answering categories were adapted to the respective questions and ranged from Likert scales to binary schemes. Except for the basic sociodemographic questions, all items were randomized. Respondents were prompted with the question ‘Do you approve or disprove of the following hypothetical policy?’ The answer categories were ‘approve’ or ‘disapprove.’

With respect to ‘trust in institutions,’ we used two different questions to reduce the risk of methodological artefacts (Online Appendix A1). The first was taken from the World Value Survey: ‘How much do you trust in the following institutions?’ Then a set of public institutions was listed (namely: the armed forces; the police; the courts; the government; political parties; parliament; the civil service; universities; the European Union; the United Nations). The second item asked: ‘How much do you trust governmental institutions?’ We also asked whether people believe in the free market as best way to solve environmental and economic problems, a question used in environmental research.Footnote13 All items were to be answered on seven-point Likert scales.

Statistical equivalence

Statistical equivalence of the survey instrument was ensured by professional translation of the new questionnaire items from English in the respective languages, followed by a back translation into English.Footnote14 The Flemish questionnaire was translated, back translated, and adapted in full. Online surveys are widely used and familiar to most respondents in the target countries, which all show a very high internet penetration rate; we could assume that answers were not systematically skewed due to lack of internet access or proficiency.

Statistical analysis

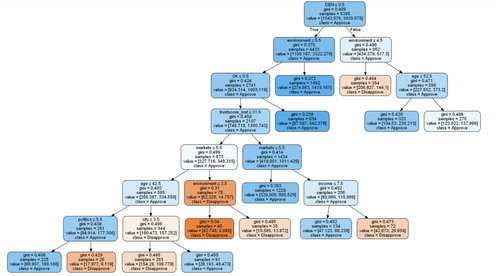

The statistical analysis took place in several steps and with several methodological approaches. In a first step, in order to get an overview of whether and how this large number of variables were interlinked, we drew a correlation heatmap indicating correlations among all variables. On the basis of the heatmap, we selected obviously correlating variables as identified by the map and looked into those more in depth. We then undertook a weighted linear regression of all variables and nudge approval, tested the robustness of the results with the help of a decision tree analysis, and estimated the size of the probabilities. For the regressions and the machine learning algorithms, the 15 nudges were categorized in five nudge clusters as categorized before (Reisch and Sunstein Citation2016): (1) (pure) governmental information campaigns, (2) information nudges, mandated by government; (3) default rules; (4) subliminal advertising (a pseudo-nudge, since not transparent by design and manipulative); (5) other mandates (e.g., choice architecture).

Results

Correlations of nudge approval, trust, and selected variables

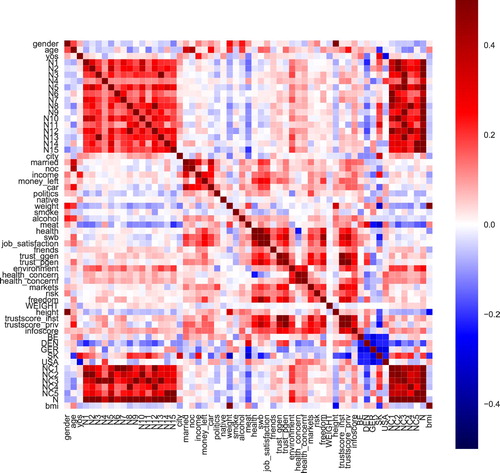

The correlation heatmap as shown in suggests some expected descriptive correlations between nudge approval and a few variables.

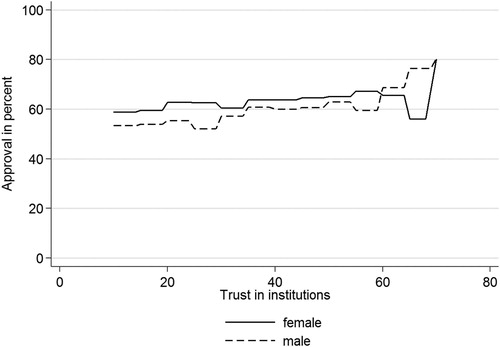

As in prior studies, gender and age showed significant correlations with approval. Moreover, the new variables ‘trust in institutions’ and ‘as well’ as ‘environmental concern’ were found to correlate strongly with higher nudge approval. Belief in markets was correlated with lower approval. Approval rates by gender, conditional on trust in institutions (trustscore_inst), are depicted in . As shown, higher trust in institutions seems to be linked to higher approval on average, and more so for women than for men.

Figure 2. Overall nudge approval, conditional on trust.

Note: The graph uses trustscore_inst as explanatory variable.

Interestingly, the concepts ‘social trust’ and ‘trust in other people’ were not correlated with approval rates. But that is not entirely surprising; our focus is on governmental policies, and higher “trust in institutions” is the more relevant question. Furthermore, and perhaps surprisingly, the heatmap did not suggest strong and significant correlations between overall nudge approval and a large set of variables, notably health status and health concern for oneself, subjective well-being, perceived freedom of choice, risk aversion, and BMI.

At the same time, the map does suggest some expected results. The frequency of meat consumption seems to be negatively correlated with approval of ‘a meat free day in public canteens’ (Nudge 15); smokers disapprove government campaigns (and subliminal advertising) against smoking (Nudge 12), and people who drink alcohol more frequently disapprove nudging in general. To that extent, behaviour seems to play a role; people do not want to be nudged to stop doing something that they like to do, and are now doing. In a way, that should not be surprising, but it might have been predicted that people engaging in harmful behaviour (such as smoking) might be especially supportive of efforts to reduce that behaviour.

Weighted regression and decision tree learning: trust in institutions

The relationship between trust in institutions and nudge approval was confirmed by a weighted regression analysis, where the effects were strong and significant. As expected, we also found a significant negative relationship between belief in markets and nudge approval. (Note parenthetically that we might have tested nudges that promote reliance on markets, in which case the relationship would be expected to be positive.) Column (1) in below shows the regression results for all nudges together as well as for the five nudge clusters.

Table 2. Weighted OLS regression for different nudge clusters.

In particular, our main specification can be described by the following model(1)

(1) where X is a

matrix of explanatory variables (as shown in Online Appendix A2) and Y is a

vector which contains the mean outcome for all nudge questions

for an individual

and question

, i.e., it is defined as follows:

Since we used sample weights (given by the weighting matrix W) that adjust for the probability of being sampled, our coefficient vector is given by:

To test the robustness of the results regarding trust in institutions, we run a weighted decision tree analysis, a machine learning method used for classification. In order to get valid results for classification, we used rounded numbers, i.e., we transformed Y in the following way:

Moreover, we implemented cross-validation as well as a grid search for hyper parameter tuning in order to improve the accuracy of our decision tree (however, we did not split our data in a test and training set).

Again, results were confirmed. As depicted in below, trust in institutions is highly correlated with approval of nudges. The same is true of environmental concern.

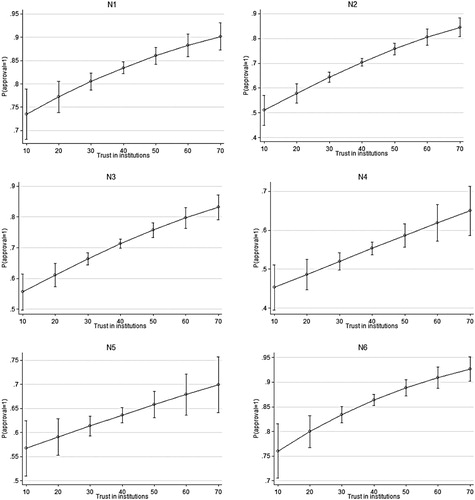

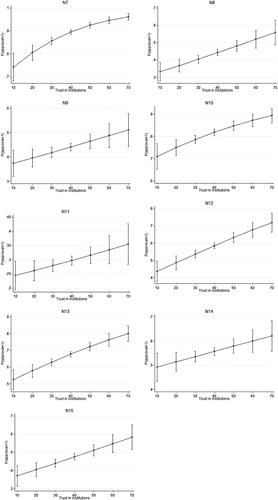

To predict (marginal) probabilities of nudge approval, i.e., the predicted size of the effects, we estimated a logistic model for each nudge question as independent variable separately. Predicted probabilities for approval conditioned on institutional trust – as shown in - differ substantially between the lowest possible trust score (10) and the highest possible trust score (70). For instance, while (ceteris paribus) the probability to accept the nudge ‘Encouraging green energy’ (Nudge 3) is estimated to be around 55% for individuals with the lowest possible value of institutional trust (for an average individual in the sample), this probability increases to almost 95% for the highest trust value. Similar effects were shown for environmental concern.

Figure 4. Predicted probabilities of nudge approval, conditional on institutional trust. Note: Probabilities are calculated using sample means of covariates.

Further results

Other results from the regression analysis are worth reporting, though they are less significant. A higher formal education (years of schooling) is correlated with lower approval rates toward nudges on average. City dwellers tend to approve the tested nudges more than people who live in villages or on the countryside. The number of children is positively correlated with approval rates. Those who are left-of-centre seem to approve of the tested nudges more than conservatives do.

Some cautionary notes are important here. First, we are speaking of the 15 nudges that were tested here. Because reactions to nudges are greatly affected by their substantive content – by the direction in which they steer people – it would be easy to produce nudges that would have different levels of approval among the relevant groups, with patterns that might reverse. For example, conservatives would certainly approve of some nudges more than those who are left-of-centre. Second, our results here should be viewed as initial indications in which direction further research might search for answers; they should certainly be taken with caution and an analysis that is much more detailed would be needed to draw conclusions for policy.

Revisiting our categorization of countries regarding nudge approval (Sunstein et al. Citation2018) and to see how stable approval rates in the three countriesFootnote15 (Denmark, Germany, and South Korea) have been over time, we compiled the results from the three study waves (2015, 2016, and 2017/18), including 16 countries. Online Appendix A3 gives an overview of samples and sampling in all 16 countries, with an overall N of 20,501 respondents. Online Appendix A4 presents the weighed OLS regression for the five nudge clusters. Confirming earlier results, the gender factor was again found to be highly relevant for nudge approval in each of the countries – except for China, where male respondents significantly approve of the tested nudges more than women (Online Appendix A5). However, this should be interpreted in light of extremely high approval in China from both genders, with rates between 80% and 90%.

We also compared approval rates of the 15 nudges over time in Denmark, Germany, and South Korea. Overall, approval rates in these countries were largely stable as compared to our earlier studies. We found only small changes in magnitude between those waves, with modest changes in both directions, i.e., less and more approval by both genders (Online Appendix A6). The country categorizations – Denmark as a ‘cautiously pro-nudge country’, Germany as a ‘principled pro-nudge nation’, and South Korea as a ‘nudge enthusiast’ – still applied three years later. This is particularly notable for the latter, since the country has undergone a dramatic democratization process in these past three years. Finally, Flanders that followed our methodology to measure their national nudge approval rate exactly, turned out to be a principled pro-nudge nation.Footnote16

Discussion

Policymakers are increasingly aware of the potential advantages of using nudges in many regulatory domains, including health, safety, and the environment (Ruggeri Citation2018). At the same time, members of the media and the public seem also increasingly aware of such policies – even though they might come under another name and in different shapes – and will often have an opinion about those approaches. In some countries, policymakers have learned to tread around behaviourally informed interventions with caution, in order to avoid being accused of being ‘national nannies’ or even worse, of manipulating their citizens. There are also questions about legitimacy, in the normative as well as the descriptive sense (John Citation2018).

The present study is based on a large original data set of nudge acceptance in 16 countries worldwide, including countries that have not been studied before with a comparable design. Our data provide empirical insights into how attitudes toward certain regulatory interventions vary with individual and cultural differences, and our analysis sheds light on the factors that influence these variations, with particular attention to trust in institutions. As in earlier studies, we have found general approval of regulatory nudges alongside marked national differences in levels of support, with Denmark on the least positive side, South Korea the most positive, and Germany, Belgium, and the US somewhere in between.16

As expected, support seems to decrease as the level of state intervention increases, as estimated along our five ‘nudge clusters’ of levels of intrusion. (We would take this finding with caution in view of the fact that people will approve of high levels of intrusion for certain kinds of misconduct, e.g., murder, assault, and theft.) In addition, acceptance is generally higher (or resistance is lower) for those nudges that are targeted to others – i.e., businesses – and lower for those that target people directly. (We would also take this finding with caution; some regulatory nudges, applied to business, would not receive approval.)

National differences should not be surprising. For example, state intervention in people’s behaviour and choices might well be found to be more acceptable in authoritarian countries such as China than in the democratic European countries. The US seems to be a special case, with a deeply rooted skepticism towards governmental intervention in general and sharply divided opinions along party lines. Surprisingly, however, we found a continued high overall public support for most nudges in question in most countries, including the US (see also Sunstein et al. Citation2018).

Our particular interest lays in the hypothesis that higher trust in public institutions will be correlated with stronger support of regulatory nudges. This has been confirmed. At the same time, people who believe in markets as the best institution to solve environmental and economic problems are more critical of nudges. Female gender was again found to be correlated with approval of nudges. Further, people’s own health concern and health status had no influence on acceptance, and the frequency of meat consumption only on the (non)acceptance of the nudge ‘meat-free days in cafeterias.’ The fact that approval rates in earlier tested countries have barely changed in the past three years is noteworthy, particularly in the case of South Korea where severe political changes have taken place.

For policymakers, our results convey relevant insights. Most important, trust in public institutions is important to cultivate in arguing on behalf of nudging and nudges. As has been suggested (John Citation2018), endorsement of nudges in general might increase when citizens are invited to participate, to make active choices, and to give feedback to planned interventions. Beneficial results in specific domains (health, environment, and safety) or with respect to specific consumption habits (meat, alcohol, or smoking) might be helpful in communicating with the public. We have not offered empirical tests of these propositions here, but our findings about the importance of trust are consistent with them.

For purposes of both effectiveness and legitimacy, close engagement with the public, and attentiveness to its concerns, can be exceedingly important. In the context of regulation, such engagement can produce valuable information, leading regulators to incorporate new knowledge (Sunstein Citation2018a); on Hayekian grounds, engagement of the public can be an important way of overcoming the inevitable limits in regulators’ knowledge (ibid.). For that reason, effective and publicly accepted nudges might be developed with a process that includes early participation of the affected groups, public scrutiny, and deliberation -- as well as transparent processes in governmental institutions. Recent research findings (Bang et al. Citation2018; Bruns et al. Citation2018) support the claim that regulatory nudges, such as default rules can be disclosed and yet effective -- and that psychological reactance seems not to occur. In addition to public participation, the ‘test-learn-adapt-share’ approach called for by leading policy labs worldwide (e.g., Haynes et al. Citation2012; Sousa Lourenco et al. Citation2016), is a prerequisite for success.

Limitations

We note several limitations to our study. If the goal is to understand people’s true beliefs, let alone their actual reactions to real world polices, we might not obtain a full picture simply by asking people, in surveys, what they think would be acceptable. Among other things, political dynamics might end up moving people in particular directions. Moreover, the design of the study was deliberately simple: We did not try to compare acceptance to other policies (such as taxes or bans) and importantly, we did not provide information on their respective effectiveness. Others (e.g., Branson et al. Citation2012) have used such studies.

In principle, using an online tool necessarily excludes those parts of the population that have no internet access or do not use the internet often enough. Acknowledging this limitation, we took great care to fulfil agreed-on quotas for representativeness. Another weakness of online surveys is that study subjects use shortcuts and might be less attentive in online survey situations than in face-to-face interviews. For that reason, we applied several attention and time filters in the questionnaire and excluded inattentive responses. Further, the literature on intercultural comparisons and use of instruments in different countries in general points at the problem of measurement invariance, something that also we cannot avoid but can (and did) take into consideration when interpreting our results.

Conclusions

We offer four points by way of conclusion. First, the study presented here confirms the existence of high levels of approval for nudges as policy tools across different countries and cultures. Second, Belgium (Flanders) joins the large set of democratic nations whose citizens generally embrace nudging, but with important exceptions and qualifications. Third, levels of public acceptance are reduced as nudges become more intrusive and less transparent. Fourth, trust in government institutions is highly correlated with approval of nudges.

It is true, of course, that surveys cannot dispose of the central normative questions. Nudges may or may not interfere with autonomy, rightly conceived (Rebonato Citation2012; Sunstein Citation2015; Citation2018b); they may or may not promote social welfare. But we should be able to agree that citizens’ views are worth respectful attention, certainly if they reflect widely shared moral convictions. Taken together with other surveys (Sunstein and Reisch Citation2019), the findings here have started to identify what citizens in diverse nations believe to be appropriate constraints on behaviourally informed interventions – what might be seen as a kind of bill of rights for regulatory nudging. To make a long story short, there is reason to believe that most citizens will disapprove of nudges that have illicit motivations (such as entrenchment of incumbent politicians); that violate rights; that are inconsistent with the interests and values of most choosers; that suffer from an absence of transparency; that count as manipulative; and that take people’s property without their explicit consent.

We aim to signal the possibility of a general commitment to such a bill of rights, without attempting to specify or elaborate it in any detail (Sunstein and Reisch Citation2019). Our emphasis here, and our central finding, involves the overriding importance of trust in institutions. In that light, there is a simple lesson for regulators. The best way to obtain trust is to earn it. For that reason, it is important not only to make behaviourally informed policies effective and cost-effective, but also to develop processes to ensure that such polices are adopted transparently, with ample opportunity for public engagement, and with openness to citizens’ objections and concerns (John Citation2018).

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (3.8 MB)Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Governing Responsible Business Research Environment at Copenhagen Business School (Denmark). We thank three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Cass R. Sunstein is the Robert Walmsley University Professor at Harvard Law School and Harvard University (United States).

Lucia A. Reisch is a Full Professor for Consumer Behaviour and Consumer Policy at Copenhagen Business School (Denmark). *Corresponding author: [email protected]

Micha Kaiser is a postdoctoral researcher at the Research Center Consumers, Market & Politics, Zeppelin University, Friedrichshafen (Germany).

ORCID

Lucia A. Reisch http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5731-4209

Micha Kaiser http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4357-6072

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. There is some debate in the behavioural literature about the appropriate definition of nudges. For an illuminating example, see Rebonato (Citation2012). We use the ordinary definition here (Thaler and Sunstein Citation2008: 8).

2. A recent overview is provided in John (Citation2018); a collection of the classic studies in those fields is compiled and put into perspective in Sunstein and Reisch (Citation2017).

3. The application of behavioural insights to financial behaviour is a distinct research field (Behavioural Finance) developed and institutionalized since decades; this is why it is not listed here.

4. Worldwide differences in attitudes are, for instance, yearly covered by the Global Attitudes Survey by the Pew Research Center (http://www.pewglobal.org/). On the important role of social norms and compliance of “Good People” see Feldman (Citation2018), Chapter 5.

5. This data has been provided by the Flemish government, based on a survey in 2017 following exactly the same survey procedure as in the other countries. A paper on this data is in preparation. While Denmark, Germany, South Korea, and the UK were chosen to represent the three categories of nudge endorsement and three different cultural clusters (see p. 7), Flanders was added for more practical reasons: expanding the data base of meanwhile 18 countries (or regions) worldwide polled with the same instrument. We expected to see similar results as in most other European countries (Sunstein et al. 2017).

6. Social trust was measured by the questions from the World Values Survey (WVS): “Would you say that most people can be trusted?” (Q48) and “How much do you trust people from the following various groups” (Q47). See full list of questions with sources in the Online Appendix A1.

7. Measured by the question: “How much are you concerned about the environment?” (Q49).

8. Note that the aim of this research was not to compare the approval of different policy tools such as legislation, taxes, or behavioural nudges, nor the different ways nudges are framed, e.g., as win or loss. Other studies have done that.

9. Since we were specifically interested in specific federal states of Germany, we oversampled in the State of Baden-Württemberg which explains the larger sample size in Germany.

10. This Standard Operation Procedure is available on request from the authors.

12. Q52: “Would you say that the free market is the best way to solve environmental and economic problems?"

13. A detailed description of this procedure was published elsewhere (Reisch and Sunstein Citation2016).

14. The first US survey was conducted already in 2014 (Sunstein Citation2016a). However, due to differences in sampling, a time series comparison seems not appropriate.

15. Possible reasons, including a methodological artifact due to the Chinese system of Social Scoring and governmental monitoring of internet use, have been discussed elsewhere (Sunstein et al. 2017).

16. We also had access to the recent data of online representative surveys covering our list of 15 nudges in Mexico (2018) and Ireland (2017). Since we did not oversee the sampling ourselves, and since only a few additional variables were covered, we could not include them fully in our database. Still, it is quite clear that Mexico belongs to the group of the “nudge enthusiasts”, and Ireland ranks somewhere in the middle of all countries regarding approval.

References

- Arad, A. and Rubinstein, A. (2018) ‘The people’s perspective on libertarian-paternalistic policies’, Journal of Law and Economics ( forthcoming).

- Arno, A. and Thomas, S. (2016) ‘The efficacy of nudge theory strategies in influencing adult dietary behaviour: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, BMC Public Health 16: 676. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3272-x

- Bang, H. M., Shu, S. B. and Weber, E. U. (2018) ‘The role of perceived effectiveness on the acceptability of choice architecture’, Behavioural Public Policy. doi:10.1017/bpp.2018.1.

- Bauer, J. and Reisch, L.A. (2019) ‘Behavioural mechanisms and (un)healthy dietary choices. A review’, Journal of Consumer Policy forthcoming in 42(1). doi: 10.1007/s10603-018-9387-y

- Benartzi, S. (2012) Save More Tomorrow: Practical Behavioral Finance Solutions to Improve 401(k) Plans. New York: Penguin.

- Benartzi, S. et al. (2017) ‘Should governments invest more in nudging?’ Psychological Science 28(8): 1041–55. doi: 10.1177/0956797617702501

- Bhawra, J. et al. (2018) ‘Are young Canadians supportive of proposed nutrition policies and regulations? An overview of policy support and the impact of socio-demographic factors on public opinion’, Canadian Journal of Public Health ( forthcoming). doi:10.17269/s41997-018-0066-1.

- Branson, C., Duffy, B., Perry, C. and Wellings, D. (2012) Acceptable Behavior? Public Opinion on Behavior Change Policy. Report on behalf of the Ipsos MORI Social Research Institute.

- Breman, A. (2011) ‘Give more tomorrow: two field experiments on altruism and intertemporal choice’ Journal of Public Economics 95(11): 1349–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2011.05.004

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986) ‘Ecology of the family as a context for human development: research perspectives’, Developmental Psychology 22(6): 723–42. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723

- Brooks, T. (2015) ‘Alcohol and controlling risks through nudges’, The New Bioethics 21(1): 46–55. doi: 10.1179/2050287715Z.00000000064

- Bruns, H., Kantorowicz-Reznichenko, E., Klement, K., Jonsson, M. L. and Rahali, B. (2018) ‘Can nudges be transparent and yet effective?’ Journal of Economic Psychology 65: 41–59. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2018.02.002

- Davidai, S. and Shafir, E. (2018) ‘Are “nudges” getting a fair shot? joint versus separate evaluation’, Behavioural Public Policy ( forthcoming). doi:org/10.1017/bpp.2018.9.

- Diepeveen, S., Ling, T., Suhrcke, M., Roland, M. and Marteau, T.M. (2013) ‘Public acceptability of government intervention to change health-related behaviours: A systematic review and narrative analysis’, BMC Public Health 13: 756. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-756

- Feldman, Y. (2018) The Law of Good People: Challenging States’ Ability to Regulate Human Behavior. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press.

- Felsen, G., Castelo, N. and Reiner, P. B. (2013) ‘Decisional enhancement and autonomy: public attitudes towards overt and covert nudges’, Judgement and Decision Making 8(3): 202–13.

- Franzen, A. and Vogl, D. (2013) ‘Two decades of measuring environmental attitudes: A comparative analysis of 33 countries’, Global Environmental Change 23(5): 1001–08. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.03.009

- Hagman, W., Andersson, D., Västfjäll, D. and Tinghög, G. (2015) ‘Public views on policies involving nudges’, Review of Philosophy and Psychology 6(3): 439–53. doi: 10.1007/s13164-015-0263-2

- Halpern, D. (2015) Inside the Nudge Unit: How Changes can Make a Big Difference. London: WH Allen.

- Halpern, S. D., French, B., Small, D.S., et al. (2015) ‘Randomized trial of four financial-incentive programs for smoking cessation’, New England Journal of Medicine, 372: 2108–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414293

- Haynes, L., Service, O., Goldacre, B. and Torgerson, D. (2012) Test, Learn, Adapt: Developing Public Policy with Randomised Controlled Trials. London: Cabinet Office Behavioural Insights Team (BIT).

- Inglehart, R. et al. (eds.) (2014) World Values Survey: Round Six - Country-Pooled Datafile Version: http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV6.jsp. Madrid: JD Systems Institute.

- John, P. (2018) How far to Nudge: Assessing Behavioural Public Policy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Jones, R., Pykett, J. and Whitehead, M. (2014) Changing Behaviours: On the Rise of the Psychological State. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Jung, J. Y. and Mellers, B. (2016) ‘American attitudes toward nudges’, Judgement and Decision Making 11(1): 62–74.

- Junghans, A.F., Cheung, T.T.L. and De Ridder, D.T.D. (2015) ‘Under consumers’ scrutiny: An investigation into consumers’ attitudes and concerns about nudging in the realm of health behavior’, BMC Public Health 15: 336. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1691-8

- Junghans, A.F., Marchiori, D. and De Ridder, D.T.D. (2016) The who and how of Nudging: Cross-National Perspectives on Consumer Approval in Eating Behaviour, Unpublished Manuscript, Utrecht: Utrecht University.

- Kahneman, D. (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Loibl, C., Sunstein, C.R., Rauber, J. and Reisch, L. (2018) ‘Which Europeans like nudges? approval and controversy in four European countries’, Journal of Consumer Affairs ( forthcoming).

- OECD (2017) Behavioural Insights and Public Policy: Lessons From Around the World. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Osman, M., Fenton, N., Pilditch, T., Lagnado, D. and Neil, M. (2018) ‘Who do we trust on social policy interventions?’ Applied Social Psychology. available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/[Article DOI tbc] (accessed 17 September 2018).

- Poortinga, W., Steg, L. and Vlek, C. (2004) ‘Values, environmental concern, and environmental behavior: A study into household energy use’, Environment and Behavior 36(1): 70–93. doi: 10.1177/0013916503251466

- Rebonato, R. (2012) Taking Liberties: A Critique of Libertarian Paternalism. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Reisch, L. A. and Sunstein, C. R. (2016) ‘Do europeans like nudges?’ Judgement and Decision Making 11(4): 310–25.

- Rockloff, M. and Hanley, C. (2014) ‘The default option: why a system of presumed consent may be effective at increasing rates of organ donation’, Psychology, Health & Medicine 19(5): 580–5. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2013.841967

- Ruggeri, K. (Ed.) (2018) Behavioral Insights for Public Policy: Concepts and Cases. London: Routledge.

- Sousa Lourenco, J., Ciriolo, E., Rafael Rodrigues Vieira de Almeida, S. and Troussard, X. (2016) Behavioural Insights Applied to Policy. Report No. EUR 27726 EN. Brussels: Joint Research Centre (JRC).

- Sunstein, C. R. (2013) Simpler: The Future of Government. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Sunstein, C. R. (2015) ‘The ethics of nudging’, Yale Journal on Regulation 32(2). available at http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yjreg/vol32/iss2/6

- Sunstein, C. R. (2016a) ‘Do people like nudges?’ Administrative Law Review 68: 177–210.

- Sunstein, C. R. (2016b) ‘People prefer system 2 nudges (kind of)’, Duke Law Journal 66(1): 121–68.

- Sunstein, C. R. (2018a) The Cost-Benefit Revolution. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Sunstein, C. R. (2018b) ‘Misconceptions about nudges’, Journal of Behavioral Economics for Policy 2(1): 61–7.

- Sunstein, C. R. and Reisch, L. A. (2014) ‘Automatically green: behavioral economics and environmental protection’, Harvard Environmental Law Review 38(1): 127–54.

- Sunstein, C. R. and Reisch, L. A. (eds.) (2017) The Economics of Nudge. Critical Concepts in Economics Series. London: Routledge.

- Sunstein, C. R. and Reisch, L.A. (2019). Trusting Nudges: A Bill of Rights for Nudging. London: Routledge.

- Sunstein, C. R., Reisch, L. A. and Rauber, J. (2018) ‘A worldwide consensus on nudging? Not quite, but almost’, Regulation & Governance 12(1): 3–22 (first published online 26 July 2017). doi: 10.1111/rego.12161

- Szazi, B., Palinkas, A., Palfi, B., Szollosi, A. and Aczel, B. (2017) ‘A systematic scoping review of the choice architecture movement: toward understanding when and why nudges work’, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, available at osf.io/dxbtz.

- Tannenbaum, D., Fox, C. R. and Rogers, T. (2017) ‘On the misplaced politics of behavioural policy interventions’, Nature Human Behaviour 1(7): 1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41562-017-0130

- Thaler, R. and Sunstein, C. R. (2008) Nudge: Improving Decision About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Troussard, X. and van Bavel, R. (2018) ‘How can behavioural insights be used to improve EU policy?’ Intereconomics 53(1): 8–12. doi: 10.1007/s10272-018-0711-1

- Whitehead, M., Jones, R., Lilley, R., Pykett, J. and Howell, R. (2017) Neuroliberalism: Behavioural Government in the Twenty-First Century. New York: Routledge.

- White House. (2015) Using behavioral science insights to better serve the American people. Federal Register Vol. 80, No. 181. Executive Order 13707 of September 15. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2015-09-18/pdf/2015-23630.pdf

- World Bank. (2015) Mind, Society, and Behavior. World Development Report 2015. Washington, DC: The World Bank Group.

- World Values Survey Wave 6. (2010–2014). Official Aggregate v.20150418. World Values Survey Association, available at www.worldvaluessurvey.org.