ABSTRACT

This paper analyses the role and influence of the EU institutions in major reform negotiations. We argue that one of the paradoxes of European Council dominated decision-making has been the enhanced dependence on EU institutions to translate broad priorities into actual reforms. We substantiate this claim by means of an in-depth process-tracing analysis of the Fiscal Compact. The conventional wisdom is that the Fiscal Compact was a German dictate. Instead, we show that it resulted from a division of labour: political leadership by member states in the control room, and instrumental leadership by the institutions in the machine room. Such instrumental leadership is unjustly depicted as mere facilitation, with little impact on process and outcome. We juxtapose the Fiscal Compact to two similar cases of Germany-led EU reforms (the Euro-Plus-Pact and Contractual Arrangements) to reveal the leadership activities by the institutions and the fingerprints these left in the final outcome.

Introduction

The successive crises of the European Union (EU) have led to a vibrant debate about leadership, whether by particular individuals, member states or by the EU institutions (e.g., Becker et al. [Citation2016]; Nugent and Rhinard [Citation2016]). Media sources and scholarly evaluations have put a lot of emphasis on individual leaders and their (typically limited) ability to steer developments at the highest political level (what we will call ‘the control room’). The primary focus has been on Germany (and its Chancellor), the European Commission (and its President) or the new European Council (EC) President (Bocquillon and Dobbels Citation2014; Bulmer and Paterson Citation2013; Dinan Citation2017; Peterson Citation2015). Some scholars even linked the ‘mixed’ performance of the EU in dealing with successive crises to an absence of (effective) leadership at this level. The EU was portrayed as ‘failing forward’ or ‘kicking the can down the road’ (Hodson Citation2013; Jones et al. Citation2016; Menz and Smith Citation2013). Even the arguably most influential leader, German Chancellor Merkel, was generally portrayed as the person blocking, rather than creating effective solutions (‘Frau Nein’). On the side of the institutions, European Council President Van Rompuy seemingly played a marginal role, while Commission President Barroso was even less effective in his self-proclaimed role as ‘champion of the Community method’.

The enhanced presence of the European Council, and the implications of having a permanent President, have been extensively discussed, among others, by proponents of ‘new intergovernmentalism’ and ‘core state powers’ (Bickerton et al. Citation2015; Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Citation2014). Intergovernmental coordination between the Heads of State and Government (HOSG) played a more prominent role in the crisis and post crisis years, in determining the course of EU decision-making. Some of the early literature spoke about ‘competition’ between the intergovernmental and the Community method and a ‘decline’ of the latter (Chang Citation2013; Fabbrini Citation2013). More recent studies rather framed it as a reorientation by the EU institutions, moving from classic entrepreneurship to surveillance and policy management (Becker et al. Citation2016; Nugent and Rhinard Citation2016).

Yet, as we will argue, a somewhat overlooked implication of this European Council dominated decision-making is that it has also weakened the control of the member states. The informal and ‘isolated’ character of decision-making at the European Council level, paradoxically, created more instead of less dependence on EU institutions to translate the broad HOSG priorities into actual reforms. To be sure, we believe that high level political leadership is necessary for getting an issue, in our case a balanced budget rule, on the agenda. However, to translate such vague ideas into an actual legally binding reform requires instrumental leadership in the ‘machine room’. This instrumental leadership is typically supplied by institutional actors (EC President’s Cabinet, Commission, Council Secretariat) operating at this level.

To substantiate our claim, we revisit three prime examples of member state, specifically German, political leadership in the Eurozone crisis: The Fiscal Compact, the Euro Plus Pact and Contractual Arrangements. The latter two cases, in which reform measures turned out to be largely inconsequential or even failed to materialize, serve to show what happens when instrumental leadership is absent. Our main case is the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance (TSCG), often referred to as the Fiscal Compact. The conventional wisdom is that the Fiscal Compact was a German dictate. In the words of close observer Peter Ludlow (Citation2011: 34): ‘This is what the German Chancellor wanted and this is by and large what she got’. Scholarly assessments, so far, have mainly focused on the proceedings at and around the December 2011 European Council Summit, thereby treating the proceedings from the Summit until the signing of the Treaty in March 2012 as the endgame or transposition phase (Degner and Leuffen Citation2017; Schimmelfennig Citation2015; Schoeller Citation2017; Tsebelis and Hahm Citation2014). Furthermore, these studies ignored the pre-negotiation stage, in which the Council Secretariat Legal Service translated the initial idea for a balanced budget rule into actual Treaty text, thereby laying out the tracks for the actual negotiations. Only Tsebelis and Hahm (Citation2014) looked at the successive drafts of the Treaty that were leaked to the press, but they analyzed these solely from the perspective of member states bargaining, and ignore drafting and process management by the institutions.

We contend that a detailed analysis of both the pre-negotiation stage and the presumed ‘endgame’ is crucial for understanding the new role of EU institutions. This is what explains the smooth and straightforward process leading up to the final deal, which stands in strong contrast to what happened with the Euro Plus Pact and Contractual Arrangements.

We will proceed as follows. In the next section, we look at some of the dominant conceptualizations of leadership, which we believe are too ‘heroic’ in their ideas about what (institutional) leadership is and what it can accomplish. We start from the concept of entrepreneurial leadership (Young Citation1991: 285), but we disaggregate the leadership tasks, thereby making a distinction between the type of leadership and the level at which this type is displayed. The process tracing analysis of the Fiscal Compact reconstructs the leadership activities that were performed by different institutional actors and the fingerprints that these activities left in the documents. In the Conclusion, we compare these to the Euro Plus Pact and Contractual Arrangements.

Theory: entrepreneurial leadership ‘unpacked’

The concept of entrepreneurial leadership plays a pivotal role in many theoretical and historical analyses of major EU reforms. It was one of the types of leadership identified by Young (Citation1991). Leadership is generally defined as the provision of tasks that help overcome collective action problems that can prevent parties from reaching a mutually acceptable, binding agreement (Tallberg Citation2006: 17–39; Young Citation1991: 285). Young makes a distinction between a structural leader – who can use his/her structural position as bargaining leverage to reshape zones-of-possible agreement – an entrepreneurial leader – who provides leadership through negotiation skill and process management – and lastly an intellectual leader – who uses his/her ideas and expertise to shape the way in which parties frame and think about options, thereby reshaping zones-of-possible agreement.

Within the context of the Eurozone crisis, Germany is the obvious, if not only, candidate for the role of structural leader. German dominance in the Eurozone stemmed from its economic strength and position as the principal creditor, which allowed it to have a disproportionate impact on setting the rules according to which the system behaves. Germany is sometimes portrayed as a ‘reluctant’, ‘embedded’, or ‘benign’ hegemon (Blyth and Matthijs Citation2012; Bulmer and Paterson Citation2013: 1397), which implies that we cannot simply equate German overall dominance with active leadership during the negotiations.

There is also evidence suggesting that Germany acted as an intellectual leader. Scholars have argued that Germany’s doctrine of ordoliberalism became the dominant discourse for the larger part of the crisis (Matthijs Citation2016; Schäfer Citation2016). However, there is also ample reason to place this intellectual leadership with the ECB, which used its enhanced status and credibly as leverage in the debates about EMU deepening (De Rynck Citation2016). In many, but certainly not all, EMU reform debates Germany and the ECB acted as an intellectual tandem.

Lastly, entrepreneurial leadership refers to leadership provided during the actual negotiations, by putting issues on the agenda, building political momentum, and shepherding an issue through the decision-making machinery (Young Citation1991: 293). It is less obvious to place this form of active leadership with a particular member state, in our case Germany. First, there is less direct evidence that Germany actually played such a steering role in the proceedings at the civil servant level. Second, in complex multi-level negotiations, it is unlikely that one single actor – be it a member state or an institution – would be able to ‘lead the way’ from initial idea to final Treaty text. In managing EU reforms, effective leadership has often been joint leadership.

Yet, many conceptual and historical analyses of leadership still take ‘heroic’ notions of individual leadership as their point of departure. In studies of European integration, leadership is often equated with supranational entrepreneurship, meaning the ability to act as the ‘engine’ or ‘motor’ that can drive the machinery forwards with a clear purpose towards a clearly defined goal, of the kind supposedly provided by the Delors Committee in the run-up to the Single European Act and the Treaty of Maastricht (Haas Citation1958; Moravcsik Citation1999). In the literature on institutional leadership this ‘Delors type’ resonates with the concept of ‘transforming’ leadership (Burns Citation1978: 20).

Over the years, the Delors type of leadership has become a somewhat unfortunate model of a power-hungry Commission ‘hard wired to pursue ever closer union’. Even in the days of Delors the institutions primarily acted as ‘engineers of solutions’, rather than ‘political champions’ (Beach Citation2005: 103–104; Peterson Citation2015: 187–188). In a similar way, the concept of transforming leadership is an unfortunate benchmark. The concept originally stems from Burns distinction between ‘transforming’ and ‘transactional’ leadership. In Burns’ original interpretation, ‘transforming leadership raises the level of human conduct and ethical aspirations of both leader and led, and thus it has a transforming effect on both’ (Burns Citation1978: 20). Transactional leadership, on the other hand, comes down to facilitating ‘an exchange of valued things’, in which there is no higher purpose and the preferences and motives of the parties remain unaffected (Burns Citation1978: 19). In EU studies, transforming leadership has been redefined as ‘moulding the course and shape of European integration’, while transactional leadership basically refers to proper management of ‘the daily stuff of politics’ (Tömmel Citation2013: 791; see also Ross and Jenson Citation2017).

It is safe to say that in the history of the EU, episodes of ‘transforming’ leadership are highly exceptional (Hodson Citation2013: 301–302). It is also clear that in the post-Maastricht era, the possibilities for providing such leadership have become even more limited. As the EU moved into more sensitive and salient issue-areas, such as fiscal policy or economic governance, its member states have become even more wary of transferring competences (Bickerton et al. Citation2015: 703; Fabbrini Citation2013: 1005; Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Citation2014: 8). The institutions now have to cope with a European Council providing instructions and having a veto over certain policy options (Bocquillon and Dobbels Citation2014: 22).

This again shows that the concept of transforming leadership is too ‘heroic’ in terms of what it expects that leaders can do and accomplish even under exceptionally favourable circumstances, like in the run-up to the SEA (Ross and Jenson Citation2017: 119–120). The concept of transactional leadership, on the other hand, is all too common. If institutional leadership essentially comes down to the facilitation of member states negotiations, we can safely categorize all leadership by the institutions as transactional. However, this then does not provide us with a meaningful metric for assessing institutional influence.

To arrive at a realistic metric, we suggest that scholars unpack the concept of entrepreneurial leadership, taking into account the type of leadership and the level at which this type is displayed. In negotiating major EU reforms, there is a clear functional differentiation between the leadership functions that are required at specific levels of the negotiations. We make a distinction between the ‘control room’, which refers to the European Council (and Sherpa) level, and ‘the machine room’, which refers to the Council (here Eurogroup) and the preparatory groups at the ambassadors and civil servants level.

In the control room, the leadership tasks required relate to agenda-setting, the provision of political momentum, and brokerage to ensure that consensus on the final deal is reached. This type of leadership echoes the definition of political leadership given by authors such as Ross and Jenson (Citation2017: 114–115) and Tömmel (Citation2013: 797). At this level, national leaders are the ‘deciders in chief’ that set overall priorities and settle key points of contention in end game negotiations, where institutional actors like the European Council President are more neutral arbiters of agreement.

In the machine room, there is a strong demand for drafting to translate broad governmental priorities into actual texts, and for process management to avoid agenda cycling and lowest-common-denominator dynamics that can hinder parties from securing a mutually acceptable, binding reform (Tallberg Citation2006: 37–39). We use the term instrumental leadership for the provision of these leadership tasks in the machine room. While major EU reforms, such as the Fiscal Compact, were intergovernmental negotiations that were held outside of the formal institutional machinery of daily EU policy-making, the existing machinery was still utilized. This means that EU institutions had strong comparative advantages in providing the necessary legal, process and substantive expertise. National governments either lack the expertise or would not be trusted by other actors to take over drafting and process management. Therefore, by default there is a large amount of more informal delegation of instrumental leadership tasks to EU institutional actors, in particular the Council Secretariat and Commission.

While scholars generally acknowledge the impact of political leadership, they tend to equate instrumental leadership with mere facilitation, that has little impact on the process and outcome (Moravcsik Citation1999: 370–374; Tömmel Citation2013: 791). However, as we know from principal-agent theorizing, even the provision of seemingly technical leadership can have significant effects. For example, those holding the pen can subtly steer how a vaguely defined political preference is translated into actual text. Process managers can mark out and thereby shape the course of negotiations. We argue that political leadership in the control room and instrumental leadership in the machine room are both necessary for securing major EU reforms. Political leadership without instrumental leadership lacks traction, instrumental leadership without political leadership lacks purpose.

Methodological approach

The analyses assess the role and influence of the EU institutions in current major reform negotiations. We utilize three cases in our design; all of which had political leadership by the German government present.Footnote1 These cases correspond with Germany’s overall priorities as regards EMU reform: to strengthen fiscal discipline and to induce structural reforms that would increase the competitiveness of periphery countries (Bulmer and Paterson Citation2013; Matthijs Citation2016). Fiscal discipline held centre stage in the 2010 reform of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), by means of the so-called six pack. By early 2011, the talks continued, with the submission of a joint Franco-German letter to other EU leaders on 4 February 2011.Footnote2 This letter set the stage for subsequent discussions on a Competitiveness – or Euro Plus – Pact (February–March 2011), a Fiscal Compact (October 2011 – March 2012) and Contractual Arrangements (October 2012 – December 2013). The Euro Plus Pact was subsequently adopted as a symbolic, non-binding agreement that was quickly forgotten, whereas Contractual Arrangements did not even reach the machine room.

Our analysis focuses on the ‘positive’ case: the Fiscal Compact. We treat the Fiscal Compact as a ‘pathway case’ (Gerring Citation2017: 105–106). We engage in a minimalist process-tracing analysis to evaluate the impact of instrumental leadership provided by EU institutions. In minimalist process-tracing, the causal process is not unpacked into its component parts – instead what is important is that empirical manifestations of a process are made explicit in the form of ‘diagnostic evidence’ (Bennett and Checkel Citation2014: 7). In this article, we utilize two types of diagnostic evidence that can confirm the existence and impact of instrumental leadership. First, we assess what leadership activities were performed by EU institutional actors (Cabinet officials of the European Council President, Council Secretariat, ECB and Commission officials) in the machine room. Second, we identify the fingerprints, in the form of clear observable manifestations of these activities in the final outcome. As we know from legal studies, the same broad priority can be translated into legal text in ways that completely change its actual meaning, for example ensuring the provision never works, making it redundant, or subtly changing the focus of the provision from what was intended (Craig Citation2012: 233; Peers Citation2012: 414).

Regarding our sources, the analyses are based on first-hand observations of all primary documents (draft texts by institutions, proposals from governments). Moreover, the contributors were personally involved in the decision-making and/or have held multiple rounds of conversations with other key participants from the member states and institutions. To avoid source capture, we have corroborated these insider recollections with evidence that is publicly available, along with detailed comparisons of the different drafts of the treaties and other documentary sources (Franco-German letters, existing and proposed EU legislation). As a final step in our analyses, we provide a comparison of the Fiscal Compact with two ‘negative’ cases. To demonstrate causal necessity, the absence of the condition should result in the absence of the outcome. We will therefore discuss what elements of instrumental leadership were missing in the Euro Plus Pact and Contractual Arrangements and how this contributed to their demise.

Process tracing analysis: instrumental leadership and the Fiscal Compact

The Fiscal Compact was agreed at the EU Summit of 30 January and signed on 2 March 2012 by all EU member states except the Czech Republic and the United Kingdom. The main elements, reflected in Article 3.1. and 3.2, are that ‘the budgetary position of the general government of a Contracting Party shall be balanced or in surplus’ and that this shall be incorporated into national law ‘through provisions of binding force and permanent character, preferably constitutional’. The Fiscal Compact is seen as perhaps the most prominent example of Germany’s ability ‘to shape the terms of integration’ (Schimmelfennig Citation2015: 187). However, when we look closer, there is evidence that while German political leadership ensured that we got a Fiscal Compact, the form it took was shaped by instrumental leadership in the machine room. In the following, we first uncover the activities of the institutional network, followed by an assessment of the effects that they had on the final outcome.

Institutional activities

The negotiations were triggered by a Franco-German letter to European Council President Van Rompuy on 17 August 2011 that expanded on many of the themes from the letter of 4 February.Footnote3 Compared to the February letter, the August letter was quite specific about a balanced budget rule as such. What was still unclear was how this balanced budget rule could be incorporated into EU law in a workable fashion, the legal form of its incorporation and whether other aspects of the Franco-German letter related to structural reforms would be included in the process.

The Commission was not immediately on board with the idea. In the days after the October Euro Zone Summit, President Barroso instructed Director General, Marco Buti and his staff in DG Ecfin to come up with an alternative reform-package, the so-called ‘two-pack’.Footnote4 In contrast, European Council President Van Rompuy gave an informal mandate to several of his Cabinet officials to work with the Council Secretariat Legal Service to explore the options for incorporating a balanced budget rule into EU law.Footnote5 This was the start of the machine room process that resulted in the adoption of the Fiscal Compact in March 2012.

By November 2011, the Council Secretariat Legal Service had drafted an embryonic version of a Fiscal Compact that focused on incorporating a balanced budget rule.Footnote6 Initially, the legal base was Article 126(14.2), which is a passerelle clause that allows the Treaty protocol to be amended through a unanimous Council decision. Van Rompuy Cabinet officials informally floated the Secretariat draft with the member states, but the German government indicated that it preferred a stronger legal instrument that could not be reversed by a future Council decision. Instead, they preferred to use the ordinary revision procedure (Article 48 TEU).Footnote7 Note that Germany was vetoing the legal form, but not the content of the draft. In fact, the Council Secretariat draft would set the stage for subsequent debates at the political level.

The proceedings at and around the European Council Summit of December 2011 have been extensively covered (Ludlow Citation2011: 10–13, 24–25). Suffice to say that this was not a particularly difficult summit. German political leadership resulted in a quick and relatively easy agreement to the Statement by the Euro Area HOSG. There were few member states – not even Italy – who dared to openly argue against the idea, out of fear for market punishment (Moschella Citation2017). Seeing that the UK blocked the option of an ordinary reform of the Treaties, due to Cameron’s request to add a protocol on financial services, the decision was taken, already before midnight, to go for an intergovernmental agreement (IA).

The Summit Statement of 9 December endorsed the core of the balanced budget rule in the November draft proposed by the Council Secretariat.Footnote8 However, given the change in legal form to an international agreement, it was clear that more articles would have to be drafted. One aspect concerned the enforcement of the balanced budget rule. While a protocol would have automatically fallen under existing enforcement procedures, it was up to the Council Secretariat Legal Service to figure out how enforcement would work for the IA. The Summit statement merely noted that: ‘We recognise the jurisdiction of the Court of Justice to verify the transposition of this rule at national level’, but did not indicate how it could work.

The next step was to come up with a format and decide on the modalities for turning this political declaration into a full-fledged Treaty. This process started with a letter on 14 December 2011 from Uwe Corsepius, Secretary General of the Council, to the Coreper, in which he outlined the process, participants and deadlines. Due to the British reservations, discussed above, there was no established forum or format available. The Council Secretariat came up with an intricate division of labour. The negotiations would take place in an ad hoc working group, building on, but outside of, the structures of the Eurogroup Working Group (EWG). But the preparations would still be done by the preparatory bodies of the Council. To ensure compatibility with the Treaties and secondary law of the Union, the Council Secretariat Legal Service was charged with drafting the first version of the agreement. The Legal Service copy-pasted verbatim the November draft into their first draft text of the Fiscal Compact, and fleshed out the modalities of enforcement and other issues in a first draft tabled on 19 December.

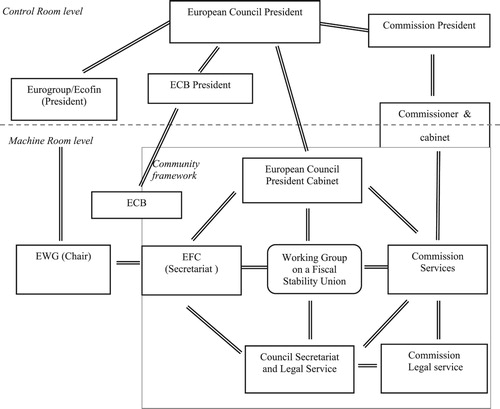

In the machine room, leadership would be provided by a core group of officials that bridged institutional boundaries. provides an overview of the inter-institutional network, with the lines representing inter-institutional connections, which pivoted around officials from the European Council President’s Cabinet (Odile Renaud-Basso, Jose Leandro), the Council Secretariat’s Economic and Financial Affairs Unit (Olaf Prüssmann) and Legal Service (Therese Blanchet, Alberto de Gregorio) and the EFC/EWG Secretariat (Pim Lescrauweat). In practice, the Secretariat of the Economic and Financial Committee (EFC) would act as the crucial node in the inter-institutional network. The EFC bridges institutional divides, located within but acting independently from the Commission, preparing the work of the Council-based Eurogroup Working Group (EWG) and staffed by Commission officials as well as member states representatives. While the Council Secretariat Legal Service de-facto acted as the penholder, it worked in close collaboration with Commission officials within the EFC framework.

The Commission itself was represented by the Director General of DG Ecfin, Marco Buti and the head of the Commission Legal Service, Luis Romero. The Commission initially played a rather modest role, but once revisions to the Secretariat draft started, the Commission provided a lot of written and oral input that ensured that the Fiscal Compact would be compatible with the revised SGP and other elements of the six-pack and upcoming two-pack. It was the role of the ECB (represented by Jörg Asmussen and Gabriel Glöckler) to try to strengthen the text, or at least to prevent ‘a substantial watering down … of the initial general agreement on an ambitious fiscal compact.’Footnote9 The overall lead was with Van Rompuy’s Cabinet officials, particularly Odile Renaud-Basso. Their main priority was to stay close to the November draft. They therefore wanted to keep the discussions short and focused. Their strategy was to have a limited number of plenary meetings in the machine room, after which any open points would (have to) be taken up to the Eurogroup meeting of 23 January and otherwise the Sherpa meeting of 30 January that would prepare the European Council meeting.

Two things were noteworthy from the perspective of process management. First, all documents would be issued as room documents. Second, to avoid having to deal with all comments on a point-by-point basis, bracketed texts were not used:

We were dealing with people who were not so familiar with how Treaty negotiations normally work. Moreover, everything needed to be done very quickly. From the side of the institutions, there was a quite strong steer on it, particularly from the European Council President Cabinet. They did not want lengthy discussions on every little detail, certainly not during the meetings. Basically, member states were asked to shut up, or take it higher up.Footnote10

The first meeting of the ad hoc working group on 20 December was used for general comments. The only substantive issue on the table was the participation of the non-euro area member states, to be addressed in Title I. The main message to the member states was the very tight timetable, which forced them to stick closely to the agreement reached by the HOSG, which had been based on the original Council Secretariat Legal Service draft (see above). Therefore there was a strong need to rely on ‘the pragmatic working methods of the EWG’.Footnote11 The Chair was determined to avoid the typical ‘drafting exercises’ that we know from regular Council or IGC meetings, in which participants would go over a draft text on a line-by-line basis multiple times. Instead, the member states were asked to submit written comments to the Secretariat before 29 December, which would take these into account when writing a second draft. Germany’s input certainly did not surpass that of others.Footnote12 France, in fact, provided more input, particularly on what would become Title IV on economic policy coordination. However, these three Articles would remain rather weak overall, and mostly restated the importance of the existing macroeconomic imbalances procedures (MIP). In contrast, the Commission provided two rounds of input that were much more influential in shaping the text (see below).

The Chair planned time for one article-by-article discussion in the second meeting on 6 January.Footnote13 The main part of the debate, unsurprisingly, was about Title III. The other Titles primarily required some fine-tuning for national consumption, for instance the explicit link between the ESM and the Fiscal Compact in the preamble, which came in the third draft, or the participation of the Euro ‘outs’ at the Eurozone Summits in Article 5.12.Footnote14 On Title V about euro area governance, the major battles had already been fought in October 2011, leading to the so-called ‘ten commandments’ of euro area governance.Footnote15 There were minor turf battles about whether the ECB President should be ‘invited’ or be considered as an integral part of the meeting, and the EP representatives unsuccessfully tried to procure a somewhat bigger role for their President. Finally, with regard to Title VI, the entering into force and incorporation into EU law, surprisingly, there was hardly any debate, also not about Article 6.16 the semi-automatic incorporation of the intergovernmental Treaty into the EU legal framework.

In the third meeting of 12 January agreement was reached on most issues, paving the way for the final tweaks in the run-up to the European Council summit. On 19 January the Chair of the Working Group sent a letter to the member states, outlining the ‘open’ issues for the end-game.Footnote16 The ministers endorsed the provisional deals reached by the working party on the deficit (and not debt) criterion, the exclusion of the Euro Plus Pact and the link between ESM and Fiscal Compact.Footnote17 The Sherpas then rubber-stamped it in the run up to the to the Eurozone Summit of 30 January 2011, where it was showcased as one of the major steps of the overall strategy to fight the crisis.Footnote18

Institutional fingerprints

In the following, we discuss the effects of institutional leadership. The backbone is a systematic assessment of the fingerprints that were left by institutional involvement in the legal text. These assessments are based on interviews with participants and a comparison of the final document to the Franco-German letters of August and December 2011 and the Council Secretariat’s first and second draft of November and December 2011 and, secondly, a comparison of the final text to existing EU law. We categorized these effects as: ‘substantial’, ‘some’ or ‘few’ institutional fingerprints. A detailed documentation of the evidence and comparisons is provided in the online appendices.

Instead of discussing all the individual fingerprints, we use them to make three points. First, by drafting and managing the revisions of draft texts, EU institutions laid out the tracks for the subsequent negotiations, in that they set the parameters for what was included and the overall structure of the final deal. Second, institutional leadership ensured that, in spite of the ad-hoc intergovernmental set-up of the process, the final deal was compatible with, if not almost redundant in relation to, existing and proposed EU legislation. Third, by controlling the negotiation process, the institutions ensured that this watered-down and Communitarized deal was shepherded through the machine room negotiations without any significant changes. As one of the participants put it:

The intergovernmental mode essentially served as the ‘surrogate mother’, while the DNA shows that this was very much a Community baby.Footnote19

Second, while it was formally an intergovernmental process, the institutions operated as forcefully and proactively as they would have in any regular Community process. Most of the changes in the draft texts brought the Fiscal Compact even more firmly into the fold of the Community, in particular with the revised SGP. There are plenty of fingerprints that could be mentioned here. For instance, the Secretariat ensured that EU law would always trump any obligations included in the Fiscal Compact (Article 2). The definitions of convergence towards ‘medium-term budgetary objectives’ (Article 3.1b) and ‘temporary deviations’ due to ‘exceptional circumstances’ (Article 3.1d & 3.3.) were aligned with the SGP. The automatic correction mechanism (Article 3.1e) and the budgetary and economic partnerships (Article 5) were equally aligned with existing legislation and the upcoming two-pack. On the issue of enforcement, the Commission and Council Secretariat withstood German pressure to confer the ability to bring non-compliance to the ECJ to the Commission, by showing that there was no basis for this in the Treaties (Article 273 TFEU).

Overall, the Commission’s technical input of 3 and 6 January served to ensure the legal compatibility of the draft with existing EU law, which in effect watered down the novelty of the instrument. Instead of using track-changes, as the member state contributions did (see below), the Commission notes contained fully revised articles, with legal and substantive justifications, which were subsequently taken over in the fourth draft. For instance, in the note of 6 January, the Commission explained how the automatic correction mechanism could be made ‘fully compatible with the Stability and Growth Pact provisions and in particular with the provisions on significant deviation in the preventive arm’.Footnote20 Additionally, the Commission proposed the draft Article that committed governments to incorporate the Fiscal Compact into EU law within five years, which was again adopted almost word-for-word in the final draft as Article 16.

Third, the institutional network was able to shepherd the draft through the machine room with little input from member states. We can assess the effectiveness of this ‘shielding’ process, by comparing the November and December 2011 drafts of the Legal Service to the six subsequent drafts and to the final text (see supplementary appendix 1). Most noteworthy is the fact that there are very few major revisions. Already in the days after the December European Council Summit, representatives from the different institutions had come together to decide that this would all be done in a few short meetings, with limited documentation (e.g., use of room documents, no bracketed text, no circulation of minutes). There were limited opportunities (and a narrow time frame) for member states to provide input and debate the issues. Most member states had provided only minor track-changes to the Secretariat’s draft, practically all of which were still ignored in the second draft text (see supplementary appendices 1 and 2). Most of the debate, in fact, took place within the institutional quadrangle in the run-up to the three meetings (see ).Footnote21 Overall, the process was therefore about ensuring compatibility with both the Conclusions of the HOSG, (role of the EC President Cabinet and Council Secretariat Legal Service) and with existing legal framework of the enhanced SGP (role of EFC Secretariat and Commission).

Concluding comparison

The process tracing analysis revealed the leadership activities provided by the EU institutions in the negotiation of the Fiscal Compact. In the Conclusion, we compare the Fiscal Compact to the Euro Plus Pact and Contractual Arrangements, to assess what happens when such activities are missing. All three initiatives fitted with Germany’s ideas about enhancing fiscal discipline and inducing structural reforms, as reflected in the aforementioned Franco-German letter of February 2011. The letter had, first of all, called for a ‘competiveness pact’ to be achieved by introducing ‘concrete commitments [to structural reforms] more than already decided’ to be adopted at the national level. Implementation of these commitments was to be evaluated by the Commission, and the introduction of a sanctions mechanism was to be examined. Regarding structural reforms, the letter for instance called for the abolition of wage/salary indexation, reforms of the retirement age, common assessment basis for corporate income tax, and mutual recognition of diplomas and vocational qualifications.

The Commission was not opposed to a competitiveness pact in principle, but they were concerned that new commitments might clash with existing EU rules. The debate about the Euro Plus Pact was therefore a rather strange one, with Commission President Barroso’s continuously emphasizing that, ‘no competences are being withdrawn from the institutions’, while Chancellor Merkel kept stressing that no competences were being transferred.Footnote22 While the EC President’s Cabinet and Council Secretariat were willing to provide some support, particularly in preparing for the Eurozone summit of 11 March 2011, the Commission still did not warm up to increased surveillance of national reforms.Footnote23 In their view, the Pact only replicated what they were already doing, as part of the monitoring cycle of the European Semester.Footnote24 This reticence led Merkel to push the reforms through the European Council, attempting to provide the instrumental leadership required together with France.Footnote25 The resulting Euro Plus Pact of 25 March 2011 was, not surprisingly, a non-binding declaration that would run for one year, after which it was dissolved into the European Semester.

The plan for Contractual Arrangements is another example of the limits of German (instead of Franco-German) political leadership. After the failed Euro Plus Pact, and related attempts to strengthen commitments to structural reform were not taken up in the Fiscal Compact, Germany launched the idea of an explicit quid quo pro linking EU funds to structural reforms. When launched, many observers were led to believe that all Eurozone members would soon have to sign Brussels approved economic adjustment programmes, like Greece and other programme countries.Footnote26 While contracts were undoubtedly a German idea, the European Council President facilitated decision-making in the control room. President Van Rompuy kept putting the contracts on the agenda of European Council (of October and December 2012, June, October and December 2013). At the Sherpa level, Van Rompuy’s deputy head of Cabinet, Didier Seeuws was tasked with fleshing out the details (Ludlow Citation2013: 12–13), with the European Council periodically endorsing their work.Footnote27 There were passionate debates about the contracts, particularly at the December 2013 European Council Summit, with the Sherpas standby to explain the details. The Conclusions manage to address ‘Contractual Arrangements’ eleven times. However, when the smoke had cleared, the mandate for reform had not become more specific: ‘further work will be pursued’, and the presidents of the institutions were invited ‘to report to the October 2014 European Council’ on the issue.Footnote28 By that time, the idea of contracts had been transformed into non-binding ‘partnerships for growth, jobs and competitiveness’.

What was again missing was instrumental leadership in the machine room. The control room process was not connected to the grid (meaning the machine room). There would be a few EFC meetings in which the contracts were politely discussed, but there was no taskforce or working group charged with translating these ideas into a proposal for a binding reform. Again, the Commission was not a fan of the idea, but like on the Euro Plus Pact, it was willing to provide some input, here in the shape of a Communication. The contracts were reframed into a ‘convergence and competitiveness instrument (CCI)’ that would induce member states to engage with necessary structural reforms and monitor their compliance.Footnote29 These would become mandatory only for member states under an excessive imbalance procedure (EIP) and voluntary for all others. Furthermore, the Commission was keen to reduce its own role to engaging in a dialogue about reforms with national governments and parliaments.Footnote30 This institutional strategy of non-engagement effectively came down to killing it softly.

Overall, this paper has sought to provide a more realistic metric for assessing institutional leadership activities and their effects. Many have reflected on ‘the rise of European Council centered governance’ and what this implies for the role of the EU institutions.Footnote31 But current theorizing still clings to rather heroic conceptions of leadership, and what it can accomplish, in the context of the Eurozone crisis, the refugee crisis or beyond. The EU system has always been characterized by interdependencies, also in the days of Delors. But these interdependencies have been brought to the forefront by recent crises. This brings us back to the paradox of European Council centered governance. Increased involvement from the highest political level can enhance, rather than diminish, the influence of those who are asked to carry out their orders.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (68.7 KB)Acknowledgement

This work is part of a research project supported by the Danish Council for Independent Research under Grant DFF-4003-00199. We thank Olaf Prüssmann for his support and contribution to this project. We would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sandrino Smeets

Sandrino Smeets is Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Aarhus University and the Institute for Management Research, Radboud University.

Derek Beach

Derek Beach is Professor, Department of Political Science, Aarhus University

Notes

1 And where the underlying preferences of other governments in relation to these reforms were constant.

2 Letter to EU 27 leaders. Reprinted in https://www.politico.eu/article/merkel-sarkozy-outline-competitiveness-pact/.

3 Letter to President Van Rompuy, 17-8-2011. A second Franco-German letter was send on 7-12-2011.

4 Author’s interviews, Commission services, 24-3 &27-8-2015.

5 Author’s interviews, Council legal service, Brussels, 26-09-2017.

6 Author’s interview, Council legal service, Telephone, 13-11-2018.

7 Author’s interviews, Council legal service, Brussels, 26-09-2017.

8 Statement by the Euro Area Heads of State or Government: 4-5, Brussels 9 December 2011.

9 Letter by Jörg Asmussen to the Members of the EWG Ad-Hoc Working Group on the Fiscal Stability Union, 12 January 2012.

10 Author’s interviews, EFC and Commission services, 26-9-2017.

11 Summing up letter of the Meeting of the Eurogroup Working Group Working Group on a Fiscal Stability Union, Letter from the Chair to the European Council President, 20 December 2011.

12 The authors had access to documents that reflected the input from member states. Germany provided input on 28 December 2011 and 9 January 2012.

13 Summing up letter of the Meeting of the Eurogroup Working Group Working Group on a Fiscal Stability Union, Letter from the Chair to the European Council President, 6 January 2012.

14 Poland wanted to be invited to operational Summits, but had to settle for being invited ‘when appropriate and at least once a year’.

15 Euro Summit Statement, Brussels 26-10-2011: ‘Annex I ten measures to improve the governance of the euro area’.

16 Letter by the Chairman of the Ad Hoc Working Group on a Fiscal Stability Union, 19 January 2012.

17 3141st Council meeting, Economic and Financial Affairs, Brussels, 23/24 January 2012 p. 15.

18 ‘Agreed lines of communication by euro area Member States’ Brussels, 30-1-2012.

19 Author’s interviews, Council legal service, Brussels, 26-09-2017.

20 Commission intervention dated 6-1-2012 titled ‘International Agreement on a Reinforced Fiscal Union’.

21 This is based on interviews and personal recollections from participants from the institutions and from member states.

22 Agence Europe, 05-02-2011 ‘EU Summit: Focus on economic governance and Franco-German axis’.

23 Agence Europe, 03-03-2011 ‘Van Rompuy/Barroso version of the competitiveness pact’.

24 Author’s interview, Commission Director General level, 27-6-2013.

25 Spiegel Online, 31-01-2011. ‘An Economic Government for the Euro Zone?’.

26 Financial Times, 02-10-2012, ‘EU draft urges contracts for euro states’.

27 Agence Europe, 5-12-2013. Annotated agenda of the Sherpa meeting. European Council Conclusions, Brussels 27/28 June 2013, Completing the Economic and Monetary Union: 14.

28 European Council Conclusions, Brussels 19/20 December 2013, Economic and Monetary Union: 32–35.

29 Commission Communication ‘The introduction of a Convergence and Competitiveness, Brussels 20-3-2013.

30 Author’s interviews, Commission services 25-3, 26-3, 27-6-2013.

31 Author’s interview, Peter Ludlow, 8-5-2018.

References

- Beach, D. (2005) The Dynamics of European Integration. Why and When EU Institutions Matter, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

- Becker, S., Bauer, M.W., Connolly, S. and Kassim, H. (2016) ‘The commission: boxed in and constrained, but still an engine of integration’, West European Politics 39(5): 1011–31. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2016.1181870

- Bennett, A. and Checkel, J. (2014) Process Tracing: From Metaphor to Analytic Tool, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bickerton, C.J., Hodson, D. and Puetter, U. (2015) ‘The new intergovernmentalism: European integration in the post-Maastricht era’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 53(4): 703–22.

- Blyth, M. and Matthijs, M. (2012) ‘The world waits for Germany’, Foreign Affairs, June 2012.

- Bocquillon, P. and Dobbels, M. (2014) ‘An elephant on the 13th floor of the Berlaymont? European council and commission relations in legislative agenda setting’, Journal of European Public Policy 21(1): 20–38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.834548

- Bulmer, S. and Paterson, W.E. (2013) ‘Germany as the EU’s reluctant hegemon? Of economic strength and political constraints’, Journal of European Public Policy 20(10): 1387–405. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.822824

- Burns, J.M. (1978) Leadership, New York: Halper Collins Publishers.

- Chang, M. (2013) ‘Fiscal policy coordination and the future of the community method’, Journal of European Integration 35(3): 255–69. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2013.774776

- Craig, P. (2012) ‘The stability, coordination and governance treaty: principle, politics and pragmatism’, European Law Review 37(3): 231–48.

- Degner, H. and Leuffen, D. (2017) Powerful Engine or Quantite Negligeable? The Role of the Franco-German Couple during the Euro Crisis. EMU Choices Working Paper Series.

- De Rynck, S. (2016) ‘Banking on a union: the politics of changing eurozone banking supervision’, Journal of European Public Policy 23(1): 119–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1019551

- Dinan, D. (2017) ‘Leadership in the European Council: an assessment of Herman Van Rompuy’s presidency’, Journal of European Integration 39(2): 157–73. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2016.1278442

- Fabbrini, S. (2013) ‘Intergovernmentalism and its limits: assessing the European Union’s answer to the euro crisis’, Comparative Political Studies 46(9): 1003–29. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013489502

- Genschel, P. and Jachtenfuchs, M. (2014) Beyond the Regulatory Polity? The European Integration of Core State Powers, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gerring, J. (2017) Case Study Research. Principles and Practice, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Haas, E. (1958) The Uniting of Europe: Political. Social and Economic Forces 1950–1957 (2nd ed.). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Hodson, D. (2013) ‘The little engine that wouldn’t: supranational entrepreneurship and the Barroso commission’, Journal of European Integration 35(3): 301–14. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2013.774779

- Jones, E., Kelemen, R.D. and Meunier, S. (2016) ‘Failing forward? The Euro crisis and the incomplete nature of European integration’, Comparative Political Studies 49(7): 1010–34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015617966

- Ludlow, P. (2011) ‘The European Council of 8/9 December 2011.’

- Ludlow, P. (2013) ‘The European Council of 27-28 June 2013.’

- Matthijs, M. (2016) ‘Powerful rules governing the euro: the perverse logic of German ideas’, Journal of European Public Policy 23(3): 375–91. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1115535

- Menz, G. and Smith, M.P. (2013) ‘Kicking the can down the road to more Europe? Salvaging the euro and the future of European economic governance’, Journal of European Integration 35(3): 195–206. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2013.774783

- Moravcsik, A. (1999) ‘A new statecraft? Supranational entrepreneurs and international cooperation’, International Organization 53(2): 267–306. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899550887

- Moschella, M. (2017) ‘Italy and the fiscal compact: why does a country commit to permanent austerity?’, Italian Political Science Review 47(2): 202–25.

- Nugent, N. and Rhinard, M. (2016) ‘Is the European commission really in decline?’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 54(5): 1199–215.

- Peers, S. (2012) ‘The stability treaty: permanent austerity or gesture politics?’, European Constitutional Law Review 8(3): 404–41. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1574019612000272

- Peterson, J. (2015) ‘The commission and the new intergovernmentalism. Calm within the storm?’, in C.J. Bickerton, D. Hodson and U. Puetter (eds.), The New Intergovernmentalism. States and Supranational Actors in the Post-Maastricht Era, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 185–207.

- Ross, G. and Jenson, J. (2017) ‘Reconsidering Jacques Delors’ leadership of the European Union’, Journal of European Integration 39(2): 113–27. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2016.1277718

- Schäfer, D. (2016) ‘A banking union of ideas? The impact of ordoliberalism and the vicious circle on the EU banking union’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 54(4): 961–80.

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2015) ‘Liberal intergovernmentalism and the euro area crisis’, Journal of European Public Policy 22(2): 177–95. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.994020

- Schoeller, M.G. (2017) ‘Providing political leadership? Three case studies on Germany’s ambiguous role in the Eurozone Crisis’, Journal of European Public Policy 24(1): 1–20. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1146325

- Tallberg, J. (2006) Leadership and Negotiation in the European Union, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tömmel, I. (2013) ‘The presidents of the European Commission: transactional or transforming leaders?’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 51(4): 789–805.

- Tsebelis, G. and Hahm, H. (2014) ‘Suspending vetoes: how the euro countries achieved unanimity in the fiscal compact’, Journal of European Public Policy 21(10): 1388–411. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.929167

- Young, A.R. (1991) ‘Political leadership and regime formation: on the development of institutions in international society’, International Organization 45(3): 281–308. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300033117