ABSTRACT

In the early days of European integration, identity politics played a marginal role in what was an isolated, elite-driven, and unpoliticised integration process. Things have changed dramatically, however. European integration has entered the area of mass politics, and against the backdrop of the recent crises and the Brexit referendum, people’s self-understanding as (also) European or exclusively national has the potential to determine the speed and direction of European integration. This development is also reflected in theory building. While neo-functionalism and liberal intergovernmentalism paid little attention to public opinion, the conflict between collective identities and functionality is at the heart of postfunctionalist theory. This article assesses the use value of these grand theories of European integration for understanding identity politics in the European Union, and embeds them in a wider discussion of scholarly research on the causes and consequences of European identity.

Introduction

It is as impracticable as it is unnecessary to have recourse to general public opinion and attitude surveys, or even to surveys of specific interested groups, such as business and labour. It suffices to single out and define the political elites in the participating countries, to study their reactions to integration and to assess changes in attitude on their part. Ernst Haas (Citation1958: 17)

This article argues that citizens’ collective identities have become increasingly relevant for European integration, and that three interrelated developments can help explain the increase of identity politics in the EU: (1) the move from technocratic, isolated decision making into the arena of mass politics which gives less weight to rational interest-seeking considerations; (2) the encroachment of European integration into policy areas of core state powers that are more closely linked to questions of solidarity and national sovereignty; (3) the increased participation of European citizens in transnational interactions and their exposure to European socialization in an unequal and socially stratified manner.

What purchase do theories of European integration – grand and middle range – have to help us understand identity politics in the EU today, and to what extent do they shed light on the three developments sketched above? This article re-engages three grand theories of European integration – neofunctionalism, intergovernmentalism, and postfunctionalism (Hooghe and Marks Citation2019) by discussing their perspectives on identity politics in the EU. In contrast to postfunctionalism, ‘intergovernmentalists and neofunctionalists fail to address the demos question head on’ (Cederman Citation2001: 140). There has been important research on European identity beyond the grand theories, and to understand identity politics in the EU, one needs to embed the perspectives of the grand theories into a wider scholarly discussion on collective identity and political conflict. Therefore, this paper also draws on other important research such as transactionalism (Deutsch et al. Citation1957).

The chief take-away is that neofunctionalism and postfunctionalism see the potential for European identity formation, while intergovernmentalism does not, and that postfunctionalism and neofunctionalism have differing views on whether collective identities are mobilized for or against European integration. The article concludes that postfunctionalism is most useful to understand identity politics in the EU, and that future research should consider when and how collective identities turn against further integration.

Defining collective identity

The concept of collective identity entered European integration studies relatively late. The few early authors who addressed collective identity among mass publics, such as Deutsch (Deutsch et al. Citation1957; Deutsch Citation1969), Inglehart (Citation1970), or Lindberg and Scheingold (Citation1970) used terms such as ‘we-feeling’, ‘community’, or ‘loyalty’ to describe phenomena that today would be labelled as collective identity.Footnote1 Also for this reason it is important to clarify what we mean by collective identity.

Collective identities refer to ‘social identities that are based on large and potentially important group differences, e.g., those defined by gender, social class, age or ethnicity’ (Kohli Citation2000: 117). Individuals hold multiple identities rather than a single identity, relating to different group memberships and social positions (Risse Citation2010; Steenvoorden and Wright Citation2018). They can be competing, complementary, or reinforcing. Diéz Medrano and Gutiérrez (Citation2001) speak of identities being ‘nested’, while Risse (Citation2005: 296) refers to ‘marble cake’ identities that partly overlap. Precisely how collective identities relate to each other varies across individuals and is context-dependent and situational (Cram Citation2012). Identities can be stimulated for example, by symbols and deliberation (Di Mauro and Fiket Citation2017). For some, being Greek and being European might be generally highly compatible, but might have been perceived as conflicting in the light of the sovereign debt crisis.

Identity is often juxtaposed to interest as two alternative motivations for social behaviour. While this is analytically useful, identities and (perception of) interest often go hand in hand. Common or opposing interest can influence one’s perceptions of group membership (Risse et al. Citation1999), whereas ‘who we are influences what we want’ (Abdelal et al. Citation2006: 698). What is more, a common identity is often invoked strategically to legitimise collective action and pursuit of interest.

European identity and support for European integration are closely related but not the same thing. Citizen orientations towards European integration have various dimensions (Boomgarden et al. Citation2011; Stoeckel Citation2013). It is perfectly possible that a citizen feels attached to Europe and considers herself as European, but is nonetheless critical of the direction that European integration is taking or its policy output. However, empirical research suggests that European identity and support for European integration have become increasingly correlated. While earlier research on EU support mainly explained it as a question of utilitarian cost-benefit calculations (Gabel Citation1998), more recent studies highlight the important role of collective identities in structuring support for European integration (Citrin and Sides Citation2004; Hooghe and Marks Citation2005; but see Hobolt and Wratil Citation2015).

Revisiting grand theories of integration

The following sections revisit neofunctionalism, intergovernmentalism and postfunctionalism to assess if and how these grand theories of integration can help understand identity politics in the EU. Collective identities can be studied from a top-down perspective – how are identities constructed and formed by political elites, the mass media, and institutions. They can also be studied bottom-up – how do citizens perceive themselves, how attached do they feel to a community, etc. This article takes the latter approach and aims at answering the following questions: (1) To what extent do the grand theories of European integration find public opinion and collective identity of citizens at all relevant? (2) Do they predict a positive or negative trend in public orientations towards European integration? (3) Is a collective European identity (or lack thereof) understood as a cause of integration, or is it merely seen as the end product of European integration?

There is not always a single answer to these questions. As Hooghe and Marks (Citation2019: 1) observe, the grand theories should be more seen as schools that are ‘flexible bodies of thought that resist decisive falsification’. They engage a variety of scholars with partly diverging lines of enquiry and conclusions. This makes it difficult to pin down a single line of argument for each theory, and I therefore highlight diverging perspectives on these questions.

Neo-functionalism: How to make ‘Europe without Europeans’Footnote2

Early neofunctionalism (Haas Citation1958) identifies three main drivers of European integration: Regional elites in search of efficient government, transnational interest groups in search of better representation of their interest, and the unintended consequences, or ‘spillover’ that propel regional institutions into even further integration: What starts out as a rational response to functional pressures to integrate, soon creates unintended consequences towards even more integration (Haas Citation1970: 627).

Neofunctionalism gives little room for ordinary citizens to influence European integration. And in fact, as the quote introducing this paper underlines, in The Uniting of Europe, Haas paid little attention to public opinion, although he was well aware of public criticism of European integration that today would be termed Eurosceptic (Haas Citation1958: 18). However, Haas deemed it justifiable to ignore such scepticism for two reasons. First, he argued that the public was simply ignorant and lacked understanding of European integration. Second, given the bureaucratic nature of European integration, decision makers were shielded from public scrutiny and therefore public opinion simply did not matter for integration (Haas Citation1958: 17–18).

In later revisions of neofunctionalist theory, Haas (Citation1970), Schmitter (Citation1969), and Lindberg and Scheingold (Citation1970) paid closer attention to public opinion (for a review, see Sinnott Citation1995). Lindberg and Scheingold (Citation1970) were more interested in the attitudes of citizens than of elites because they took pro-European attitudes among European policy makers for granted, but saw potential for scepticism among citizens (Lindberg and Scheingold Citation1970: 26). Their descriptive analyses of several sources of public opinion data ranging from the 1950s to the late 1960s suggested that both system support and, to a lesser extent, collective identity were increasing. This observation made them confident that there was a ‘permissive consensus’ of the public for further integration (Lindberg and Scheingold Citation1970: 62).

Neofunctionalist authors offered diverging perspectives if and how European integration could become a controversial political issue. In Beyond the Nation State, Haas argues that the fourth (and final) stage of integration towards a federal state may be facing a nationalist backlash (Haas Citation2008).

Lindberg and Scheingold (Citation1970) presented two opposite scenarios for the future: In the first one, further integration and development of European support would go hand in hand. In the second scenario, there would be a ‘trend towards radical politics based on sharp social cleavage and entailing mobilization of mass publics’ (Lindberg and Scheingold Citation1970: 251), and increasing support could not be taken for granted. However, they concluded that under conditions of economic growth and the expansion of middle-class values to the working class, the first scenario was much more likely and policy makers could continue to count on this consensus in the future (Lindberg and Scheingold Citation1970: 274–278).

Schmitter (Citation1969) accounted for the possibility that European integration might become a controversial issue and that public opinion might play a decisive role in the integration process. However, in a more recent contribution, Schmitter (Citation2009) argued that neofunctionalists did not foresee negative politicization: ‘What was not predicted was that this mobilization would threaten rather than promote the integration process. In the neo-functionalist scenario, mass publics would be aroused to protect the acquis communautaire against the resistance of entrenched national political elites determined to perpetuate their status as guarantors of sovereignty’ (Schmitter Citation2009: 211; italics in original).

It is a different question to what extent these authors expected a European collective identity to develop, and whether this development was seen primarily as a trigger for further integration or as the consequence of integration. While identity played a minor role in Haas’ theory (Checkel and Katzenstein Citation2009: 5), the introductory chapter of The Uniting of Europe suggests that Haas saw political community as a result of successful integration. According to Haas (Citation1958: 5) ‘[a] political community … is a condition in which specific groups and individuals show more loyalty to their central political institutions than to any other political authority’, and the process of political integration should lead to such loyalty – and ultimately community – at the central level. Schmitter used almost the same words when he wrote, ‘There will be a shift in actor expectations and loyalty toward the new regional center’ (Schmitter Citation1969: 166, cited by Hooghe and Marks Citation2009).

In the neofunctionalist framework, national identities among the public are not per se an obstacle to European integration. Haas (Citation1958: 14) discussed the possibility of individuals holding both a European and a national identity, either because they do not conflict with one another or because people are able to ignore these contradictions. Moreover, Haas strongly believed in the power of interests prevailing over the irrationality of identity: ‘The alleged primordial force of nationalism will be trumped by the utilitarian-instrumental human desire to better oneself in life, materially and in terms of status, as well as normative satisfaction’ (Haas Citation2004 as cited in Ruggie et al. Citation2005: 276).

To summarize, neofunctionalism paid little attention to public opinion and collective identity. Politicization, if taking place at all, was predominantly expected to mobilize in favour or European integration. Neofunctionalist scholars did not see identity politics to become a serious concern to European integration.

Intergovernmentalism: national leaders constrained by national consciousness

The pessimistic reply to the ‘new Jerusalem’Footnote3 of neofunctionalism came from Stanley Hoffmann (Citation1966). In the wake of the French veto and the ‘Empty chair crisis’, Hoffmann argued that the European nation states would remain the most important, if not only, actors in the international arena. Intergovernmentalism rejects the notion of a self-perpetuating integration process and sees European integration as a result of rational and calculated bargaining among national governments that weigh the costs and benefits of cooperation in the light of their national interest. States are willing to delegate power in areas of ‘low politics’ such as economic cooperation, but are reluctant to give up sovereignty in ‘high politics’ that is more closely linked to national sovereignty. While Hoffmann is the main representative of Classical intergovernmentalism (CI), Moravcsik (Citation1998) coined Liberal Intergovernmentalism (LI). Moravcsik focused on the grand treaty negotiations and economic interests, and presented European integration reflecting the lowest common denominator among independent states based on their national preference formation, intergovernmental bargaining and credible commitments.

While emphasizing national interest and national governments rather than regional organizations, intergovernmentalism has an equally strong focus on political elites as neofunctionalism and does not integrate mass politics into its framework. Nonetheless, there is some room for incorporating public opinion into the intergovernmentalist thinking (Sinnott Citation1995). Intergovernmentalism has an implicit understanding of public opinion in the preferences of nation states. As Hobolt and Wratil (Citation2015: 239) note, from a LI perspective, domestic interests shaping national preferences in the two-level game of European politics ‘could potentially provide a role for public opinion, assuming that EU matters are sufficiently salient to influence the electoral incentives of national politicians’. Domestic public opinion constrains the decisional space available for national politicians when engaged in EU-level bargains (Schneider and Slantchev Citation2018). Nonetheless, it remains unclear how exactly the link between national leaders and voters is established beyond the influence of domestic economic groups (Moravcsik Citation1998).

While intergovernmentalists do not address politicization as such, two elements of CI can contribute to explaining and predicting increasing controversy and political salience of European integration. The first one relates to the distinction between high and low politics (Hoffmann Citation1966). This, together with the resilience of national identities (see next section), provides ample ground for conflict when European integration is turning towards policy fields of high politics.

For a theory that assumes rational actors, CI has surprisingly much to say about national identities. In contrast, LI does not address collective identities explicitly but sees them as closely linked to the nation state (Cederman Citation2001). According to CI, national identities are very persistent to change and represent a major obstacle to European integration. Hoffmann distinguishes between (1) national consciousness, (2) national situation, and (3) nationalism. ‘Whereas national consciousness is a feeling, and the national situation a condition, nationalism is a doctrine … that gives to the nation in world affairs absolute value and top priority’ (Hoffmann Citation1966: 868). The interplay between these three factors provides the framework for foreign policy within which political leaders can act. In other words, national leaders are constrained by national identity and the legacy of the nation state.

In intergovernmentalism, a perspective for a European identity seems to be out of sight. CI and LI scholars see national identities as wedded to the nation state (Börzel and Risse Citation2018; Cederman Citation2001). Hoffmann laments the absence of a European identity in his essay Europe’s identity crisis (Citation1964) and confirms this absence thirty years later (Hoffmann Citation1994) when he writes that European member states are still too diverse and too divided to be united, and that a push in that direction could only come from daring political leaders, who are absent (Hoffmann Citation1994: 21).

But are national identities fully preventing European integration? According to Sinnott (Citation1995) Hoffmann, was misunderstood. Hoffmann did not postulate that integration could not happen, but rather argued that it was ‘contingent to a remarkable extent on developments in political culture and public opinion’ (Sinnott Citation1995: 19). And indeed, Hoffmann does not rule out the combination of national identities and support for integration: ‘One cannot even posit that a strong national consciousness will be an obstacle for movements of unification, for it is perfectly conceivable that a nation convinces itself that its “cohesion and distinctiveness” will be best preserved in a larger entity’ (Hoffmann Citation1966: 867–868).

To summarize, both strands of intergovermentalism incorporate public opinion only indirectly and do not see the potential for politicization of collective identities to bring European integration to a halt or even disintegration. While CI addresses questions of collective identity, it does so mainly at the level of elites, and sees national identities as a constraint to geopolitics. CI does not see real potential for European identity formation. While Hoffmann’s distinction into high and low politics has rightly been criticized for its arbitrary classification, it might be a useful lens through which one could see current conflicts about the integration of core state powers (Genschel and Jachtenfuchs Citation2016).

Postfunctionalism: efficiency vs identity

Hooghe and Marks (Citation2009) present a postfunctionalist theory of European integration to make sense of new developments in European politics that can neither be explained by neo-functionalism nor by intergovernmentalism. They argue that while regional integration might be triggered by a ‘mismatch between efficiency and the existing structure of authority’ (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009: 2), the outcome is a result of political conflict around collective identities rather than reflecting efficiency.

According to Hooghe and Marks, since the Maastricht Treaty it has been appropriate to speak of a ‘constraining dissensus’ of the European public. European integration has become a highly politicized issue, and policy makers today cannot ignore public opinion. This development is due to the growing salience of EU issues as European integration has increasingly tangible consequences on people’s everyday lives. Moreover, ‘[w]ith the Maastricht Accord of 1991, decision making on European integration entered the contentious world of party competition, elections and referendums’ (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009: 7). In a quest for democratic legitimacy, EU policy makers opened a once isolated decision-making process to public scrutiny. European citizens were given the opportunity to voice their criticism in national and European elections and referendums, and their representatives in the European parliament were increasingly on equal foot with the council of the EU. Consequently, politicization has changed the content and process of political decision making in the EU (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009: 8).

This new political conflict around European integration does not follow the logic of a left-right divide, but rather along a non-economic dimension, ranging from green/alternative/libertarian to traditionalism/authority/nationalism (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009: 16; Hooghe and Marks Citation2018). Hooghe and Marks argue that whether individuals see themselves as belonging exclusively to a national community or (also) as Europeans is at the heart of this divide. This conflict about European integration, and relatedly, immigration, increasingly structures European and domestic politics in general. Therefore, European integration can be seen as a critical juncture (Bartolini Citation2005) that has given rise to a new cleavage that has been called transnational (Hooghe and Marks Citation2018), integration – demarcation (Kriesi et al. Citation2008), or nomadic vs standing (Bartolini Citation2005).

From the postfunctionalist perspective, the emergence of a European identity among the masses is possible and not necessarily detrimental to national identities (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009). However, Hooghe and Marks (Citation2009) contend that collective identities are very stable and a shift from exclusively national to European identities happens at a much slower pace than European institution building. Referring to survey data up to 2009, they conclude that ‘there is no evidence of an aggregate shift towards less exclusive national identities since the early 1990s … . Until generational change kicks in, Europe is faced with a tension between rapid jurisdictional change and relatively stable identities’ (Hooghe and Marks Citation2009: 12–13).

To summarize, postfunctionalism emphasizes the politicization of exclusive national identities that constrains the process and content of European integration. The improvement of channels of democratic representation and the increasing involvement of EU decision makers in areas of core state powers have raised the political salience of European integration and have linked it more closely to collective identity. While a mass European identity is possible, its construction is much slower than the European institution building.

The stratification of European experiences

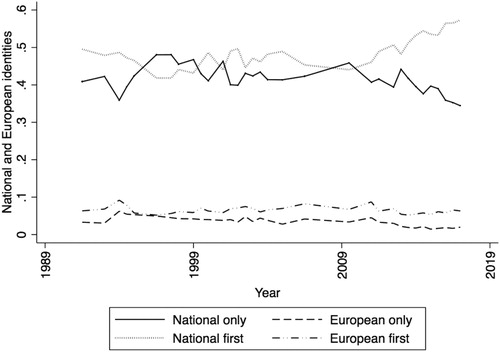

While Hooghe and Marks contend that only generational replacement will give rise to more inclusive identities, more recent Eurobarometer survey data on individual identification as European, does suggest that the share of ‘exclusive nationalists’ has been slowly decreasing over the past few years. presents the share of citizens of the EU-12 who see themselves as only national, (also) European, or only European from 1992 until 2017. shows that while the Europeans who see themselves as ‘only’ or ‘primarily’ European remain outliers, over 50 percent of the European population sees themselves as national, but also European. While this survey item has been criticized for being too context dependent (Bruter Citation2008) and for pushing respondents to think of themselves as either European or national, it is the only item that has been asked over a long time series.Footnote4

Figure 1. Proportions of national and European identification. Notes: Mannheim Trend File (1992–2002) and Eurobarometer waves 58.1, 59.1, 60.1, 61.0, 62.0, 62.2, 63.4, 64.2, 65.1, 65.2, 66.1, 67.2, 68.1, 69.2, 70.1, 71.1, 71.3, 72.4, 73.4, 75.3, 77.4, 79.5, 82.4, 84.1, 86.1, 87.1, 88.1. Countries include EU-12.

The decrease of ‘exclusive nationals’ in begs the question why we see an identitarian backlash against European integration now: Why is this decreasing share of exclusive nationals becoming increasingly vocal and influential? To make sense of this apparent paradox, it is useful to re-engage transactionalism (Deutsch et al. Citation1957; Deutsch Citation1969) and to consider the unequal and stratified involvement of European citizens in transnational interactions (Fligstein Citation2008; Kuhn Citation2015) – in other words, their unequal socialization as Europeans.

Deutsch and his colleagues (Deutsch et al. Citation1957) suggested to establish ‘security communities’ where states would be interdependent to such an extent that waging war against each other would not be perceived as a viable option. States should provide an infrastructure for regular, predictable, and institutionalized cross-border interactions among ordinary citizens that includes a wide scope of activities, such as trade, marriages, scientific cooperation, and mass media consumption. These interactions would in turn nurture a common ‘we feeling’ among the elites and the general population (for a review of transactionalist theory, see Kuhn Citation2015).

Intra-European border removal and the establishment of common European policies have indeed facilitated cross-border interactions among European citizens (Recchi and Favell Citation2009), and empirical research shows that transnational interactions have become increasingly frequent over the past decades (Kuhn Citation2015).

However, there are great disparities in the extent to which Europeans engage in cross-border interactions. Only a minority of Europeans experience European integration through frequent interactions and mobility. The majority of Europeans sporadically interacts across borders, while some remain almost exclusively in the realm of their nation-state (Fligstein Citation2008; Kuhn Citation2015). For example, Eurobarometer survey data shows that in 2006, only 7 per cent of all EU citizens had ever lived in another EU member state, more than half of the EU population had not socialized at all with EU foreigners in the preceding year and in 2007, 66 per cent of Europeans had only national friends (Kuhn Citation2015: 79–82).

Importantly, the extent to which Europeans engage in transnational interactions is socially stratified. Europeans with higher levels of education and high-status occupations tend to be significantly more transnational than the rest of the population. Research on European identity among exchange students suggests strong self-selection and ceiling effects: students who decide to embark on an international exchange are more pro-European than their peers even before they go abroad (Wilson Citation2011), and their international experience has only limited impact on European identity formation (Stoeckel Citation2016). This development is reinforced by intergenerational transmission and selection effects: Parental attitudes on European integration influence the attitudes of their children (Kuhn et al. Citation2017). Parental socio-economic background influences the extent to which school children are transnationally active (Kuhn Citation2016), and children of well-off, cosmopolitan parents self-select into higher education where they are exposed to liberal and cosmopolitan ideas (Kuhn et al. Citation2017).

Deutsch acknowledged such a possibility of stratification by referring to a layer cake of interactions, with the ‘top layers of society’ being highly integrated, the medium levels less so, and the majority of the population not at all (Deutsch Citation1953: 170).Footnote5 What Deutsch might have underestimated is the potential of political conflict (Checkel and Katzenstein Citation2009: 6, Kuhn Citation2015). Whereas Deutsch acknowledged that European integration had come to a halt in the wake of ‘eurosclerosis’, he was very optimistic about younger generations of political leaders being socialized in a Europeanized society and pushing for further integration in the future (Deutsch Citation1969: 34–35). While Deutsch predominantly emphasized the positive consequences of increased cross-border interaction (Deutsch Citation1953), they can trigger backlash against European integration, and more generally, globalization (Kuhn Citation2015), among those who do not participate themselves. These people may feel overwhelmed and disoriented by the transnationalization of their realm. This is especially the case in the wake of political controversies about labour migration and ‘benefit tourism’ (Damay and Mercenier Citation2016). In fact, opposition to free movement is prominent among economically vulnerable citizens of rich member states (Vasilopoulou and Talving Citation2018), and was an important motivation to vote ‘leave’ in the Brexit referendum (Hobolt Citation2016). Hence, transnational interactions and mobility seems to contribute in itself to a further divide between the ‘Europeans’ and the ‘nationals’.

Grand theories and identity politics in the twenty-first century

The recent crises have provided a test bed to compare the explanatory power of different theories. Börzel and Risse (Citation2018) argue that postfunctionalism helps us make sense of the Schengen crisis where policy makers could not engage in efficient problem solving due to their fear of a public backlash. In contrast, it cannot explain increasing integration in the crisis of the European Monetary Union (EMU), a pattern which fits better neofunctionalist and intergovernmentalist accounts. Similarly, Schimmelfennig (Citation2014) argues that the EMU crisis would have been a most likely case of effective constraining dissensus, but European policy makers were still able to push European technocratic integration further by involving an even more isolated institution, the International Monetary Fund. Nonetheless, policy makers have so far steered clear from true risk sharing and redistribution in the form of, for example, European unemployment benefits. Nicoli (Citation2018) tests whether crises lead to public support for further integration (in line with neofunctionalism) or rather result in weaker preferences for integration (confirming postfunctionalist expectations). The findings are mixed: while crises seem indeed to open ‘windows of opportunity for further integration, there is a clear country divide on the kind of integration’ (Nicoli Citation2018: 26).

The Brexit referendum, in turn, is an obvious example of an effective constraining dissensus of the public and identity politics which, in this case, is not only slowing down European integration, but leads to disintegration, and challenges LI expectations. According to Schimmelfennig (Citation2018: 1592) ‘[a]s Brexit is about commercial policy, affects intense and well-organized interests, and is predicted to produce negative effects with high certainty, British preferences contradict LI on its home turf’. Moreover, in pursuing a ‘hard Brexit’, i.e., to leave the customs union and the single market, the British government did not follow the preferences of business interests, which would have been expected by LI (Schimmelfennig Citation2018).

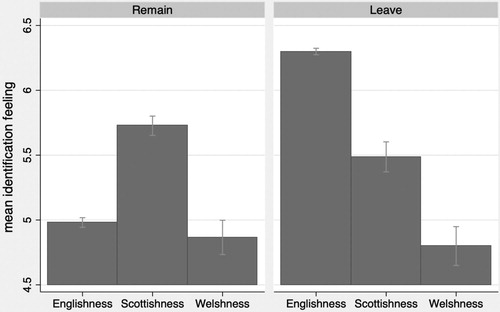

Supporting postfunctionalism, data from the British Elections Study (Fieldhouse et al. Citation2016) show that remain and leave voters had different constellations of collective identity: Feelings of Europeanness were significantly higher among remain voters (4.99 on a scale ranging from 0 to 10, standard error 0.01) than among leave voters (2.5 with standard error 0.01). shows that feelings of national identity among English, Scottish and Welsh voters played out differently in the referendum. While feelings of Englishness were highest among English leave voters, remain voters in Scotland had higher feelings of Scottishness than leave voters. There was no significant difference in Welsh identity among Welsh voters. These differences suggest that English voters see national identity and EU membership as conflicting, whereas Welsh and Scottish voters do not. However, while the leave campaign emphasized questions of national sovereignty and immigration, the remain campaign highlighted economic cost-benefit considerations of EU membership, which in hindsight might help explain why it failed to mobilize more voters.

Figure 2. Mean feelings of Englishness, Scottishness and Welshness among remain and leave voters. Notes: British Election Survey (Fieldhouse et al. Citation2016). Bars refer to mean feelings of Englishness among respondents in England, mean feelings of Scottishness among respondents in Scotland, and mean feelings of Welshness among respondents in Wales, on a scale ranging from 0 to 10.

Important pieces of the puzzle of current European mass politics can be found in all grand theories of integration: Neo-functionalists saw the potential for an increasing politicization, albeit predominantly in favour of further integration. CI scholars were right in highlighting the difference between low politics, where sovereignty is readily granted to supranational institutions, and high politics, which policy makers and the public seek to carefully guard against external influences (Hoffmann Citation1966: 908). Moreover, CI can better explain the current opposition against European integration than neo-functionalism because it is conscious of the power of persistent national identities that cannot easily be wiped out by integration projects. In contrast, LI does not help us in understanding identity politics in European integration. As Kleine and Pollak (Citation2018: 1497) observe, ‘growing empirical evidence on identity-based, anti-EU mobilization suggests, at the very least, the omission of an important variable in LI’s theory of preference formation’.

CI was too pessimistic as it did not foresee that an important portion of the European public does identify as (also) European (Risse Citation2010), and supports European integration even in areas of high politics, such as redistribution. In line with postfunctionalism, individuals who identify as Europeans and who feel attached to Europe are significantly more likely to share resources with other Europeans, and they are also more supportive of bailing out other member states in dire economic situations (Kuhn et al. Citation2018). Verhaegen (Citation2018) finds that public support for international bailouts in the wake of the sovereign debt crisis is a matter of collective identity.

A central contribution of postfunctionalism is that it has brought conflictual mass politics into scholarly discussions on European integration. Earlier research found public opinion irrelevant, as Haas’ quotation at the outset of this article underlines. Others, such as transactionalism, focused on ordinary citizens but did not fully explore the potential for political conflict. In turn, even while politicization is (still) dominated by Eurosceptic voters and right-wing populist parties, neofunctionalists were not entirely wrong in predicting politicization in favour of European integration. Grassroots movements such as ‘The Pulse of Europe’ show that some citizens are willing to become active in favour of European integration. In several pivotal elections that were often framed as a choice between nationalism and cosmopolitanism (De Vries Citation2018), we also saw mobilization of voters on the cosmopolitan end, such as in the French presidential election of Emmanuel Macron vs Marine Le Pen 2017. Amid Brexit and rising populism across Europe, it seems that ‘the Europeans’ are finally coming out of the closet and mobilize in favour of European integration.

To conclude, neo-functionalism and both classical and liberal intergovernmentalism have underestimated the disruptive potential of identity politics in European integration. While both approaches account for the possibility of deadlock in the integration process, they do not address the potential of disintegration. This is due to their focus on elites rather than mass politics, and due to their emphasis on rational, interest-seeking actors who are not easily swayed by feelings of national identity. In contrast, postfunctionalism addresses identity politics and the conflict between functional pressures to integrate and collective identities heads-on. It is therefore well equipped to provide explanations for disintegrative developments in European politics. This being said, even in times of constraining dissensus, policy makers still manage to push European integration further. Hence, future research should investigate under which conditions politicization turns in favour or against further European integration, and under which conditions public opinion succeeds in influencing policy making.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Juan Díez Medrano, Liesbet Hooghe, Gary Marks, Francesco Nicoli, participants at the workshop ‘Re-engaging grand theory’ at the EUI, Florence, May 2018, and the two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments. Sven Hegewald and Isabella Rebasso provided excellent research assistance. The usual disclaimers apply.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Theresa Kuhn is associate professor in political science at the University of Amsterdam.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 There are exceptions, such as Hoffmann’s ‘Europe’s identity crisis’ and Inglehart (Citation1970).

2 Schmitter (Citation2005: 258).

3 ‘The nation-state is still here, and the new Jerusalem has been postponed because the nations in Western Europe have not been able to stop time and to fragment space’ (Hoffmann Citation1966: 863).

4 Further research is necessary to interpret these results. Cram (Citation2012) argues that much of European identity is subconscious, and qualitative focus groups (White Citation2009) suggest that European citizens do not refer to a European collective if they are not prompted to do so by survey questions.

5 Deutsch devised this model in the context of historical nation building, but it seems fair to assume that he expected similar patterns for European integration.

References

- Abdelal, R., Herrera, Y., Johnston, A.I. and Mc Dermott, R. (2006) ‘Identity as a variable’, Perspectives on Politics 4 (4): 695–711.

- Bartolini, S. (2005) Restructuring Europe: Centre Formation, System Building, and Political Structuring Between Nation State and the European Union, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Boomgarden, H., Schuck, A.R.T., Elenbaas, M. and de Vreese, C.H. (2011) ‘Mapping EU attitudes: conceptual and empirical dimensions of Euroscepticism and EU support’, European Union Politcs 12 (2): 241–66.

- Börzel, T.A. and Risse, T. (2018) ‘From the euro to the Schengen crises: European integration theories, politicisation, and identity politics’, Journal of European Public Policy 25 (1): 83–108.

- Bruter, M. (2008) ‘Legitimacy, euroscepticism & identity in the European Union–problems of measurement, modelling & paradoxical patterns of influence’, Journal of Contemporary European Research 4 (4): 273–85.

- Cederman, L.E. (2001) ‘Nationalism and bounded integration: what it would take to construct a European demos’, European Journal of International Relations 7 (2): 139–74.

- Checkel, J.T. and Katzenstein, P.J. (2009) ‘The politicization of European identities’, in J.T. Checkel and P.J. Katzenstein (eds), European Identity, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–26.

- Citrin, J. and Sides, J. (2004) ‘More than nationals: how identity choice matters in the new Europe’, in R. Herrmann, M. Brewer and T. Risse (eds), Transnational Identities: Becoming European in the EU, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 161–85.

- Cram, L. (2012) ‘Does the EU need a navel? Implicit and explicit identification with the European Union’, Journal of Common Market Studies 50 (1): 71–86.

- Damay, L. and Mercenier, H. (2016) ‘Free movement and EU citizenship: a virtuous circle?’, Journal of European Public Policy 23 (8): 1139–57.

- Deutsch, K.W. (1953) ‘The growth of nations: some recurrent patterns of political and social integration’, World Politics 5 (2): 168–95.

- Deutsch, K.W. (1969) Nationalism and Its Alternatives, New York: Alfred Knopf Inc.

- Deutsch, K.W., Burell, S.A., Kann, R.A. and Lee, M. (1957) Political Community and the North Atlantic Area, New York: Greenwood Press Publishers.

- De Vries, C.E. (2018) ‘The cosmopolitan-parochial divide: changing patterns of party and electoral competition in the Netherlands and beyond’, Journal of European Public Policy 25 (11): 1541–65.

- De Wilde, P. and Zürn, M. (2012) ‘Can the politicisation of European integration be reversed?’, Journal of Common Market Studies 50 (S1): 137–53.

- Diéz Medrano, J. and and Gutiérrez, P. (2001) ‘Nested identities: national and European identities in Spain’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 24(5): 753–78.

- Di Mauro, D. and Fiket, I. (2017) ‘Debating Europe, transforming identities: assessing the impact of deliberative poll treatment on identity’, Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica 47 (3): 267–89.

- Fieldhouse, E., et al. (2016) British Election Study Internet Panel Wave 9. doi:10.15127/1.293723.

- Fligstein, N. (2008) Euroclash: The EU, European Identity, and the Future of Europe, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gabel, M.J. (1998) Interests and Integration: Market Liberalization, Public Opinion, and European Union, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Genschel, P. and Jachtenfuchs, M. (2016) ‘More integration, less federation: the European integration of core state powers’, Journal of European Public Policy 23 (1): 42–59.

- Haas, E. (1958) The Uniting of Europe: Political, Social amd Economic Forces 1950–1957, London: Stevens and Sons.

- Haas, E. (1970) ‘The study of regional integration: reflections on the joy and anguish of pretheorizing’, International Organization 24 (4): 607–46.

- Haas, E. (2004) ‘Introduction: institutionalism or constructivism?’, in E. Haas (ed.), The Uniting of Europe. Political Social and Economic Forces, 1950–1957, South Bend, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, pp. *XIII–*LVI.

- Haas, E. (2008) Beyond the Nation State: Functionalism and International Organization, Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Hobolt, S.B. (2016) ‘The Brexit vote: a divided nation, a divided continent’, Journal of European Public Policy 23 (9): 1259–77.

- Hobolt, S.B. and Wratil, C. (2015) ‘Public opinion and the crisis: the dynamics of support for the euro’, Journal of European Public Policy 22 (2): 238–56.

- Hoffmann, S. (1964) ‘Europe’s identity crisis: between the past and America’, Daedalus 93 (4): 1244–97.

- Hoffmann, S. (1966) ‘Obstinate or obsolete? The fate of the nation-state and the case of Western Europe’, Daedalus 95 (3): 862–15.

- Hoffmann, S. (1994) ‘Europe’s identity crisis revisited’, Daedalus 123 (2): 1–23.

- Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2005) ‘Calculation, community and cues’, European Union Politics 6 (4): 419–43.

- Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2009) ‘A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: from permissive consensus to constraining dissensus’, British Journal of Political Science 39 (1): 1–23.

- Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2018) ‘‘Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage’’, Journal of European Public Policy 25 (1): 83–108.

- Hooghe, L. and Marks, G. (2019) ‘Grand theories of European integration in the twenty-first century’, Journal of European Public Policy, doi:10.1080/13501763.2019.1569711.

- Inglehart, R. (1970) ‘Cognitive mobilisation and European identity’, Comparative Politics 3 (1): 45–70.

- Kleine, M. and Pollack, M. (2018) ‘Liberal intergovernmentalism and its critics’, Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (7): 1493–509.

- Kohli, M. (2000) ‘The battlegrounds of European identity’, European Societies 2 (2): 113–37.

- Kriesi, H., et al. (2008) West European Politics in the Age of Globalisation, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kuhn, T. (2015) Experiencing European Integration. Transnational Lives and European Identity, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kuhn, T. (2016) ‘The social stratification of European schoolchildren’s transnational experiences: a cross-country analysis of the international civics and citizenship study’, European Sociological Review 32 (2): 266–79.

- Kuhn, T., Lancee, B. and Sarrasin, O. (2017) ‘Born into tolerance? Parental socialisation and the educational divide in attitudes towards globalisation’, unpublished manuscript.

- Kuhn, T., Solaz, H. and Van Elsas, E. (2018) ‘Practising what you preach: How cosmopolitanism promotes willingness to redistribute across the European Union’, Journal of European Public Policy 25 (12): 1759–78.

- Lindberg, L. and Scheingold, S. (1970) Europe’s Would-be Polity. Patterns of Change in the European Community, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- Moravcsik, A. (1998) The Choice for Europe: Social Purpose and State Power from Messina to Maastricht, London: Routledge.

- Nicoli, F. (2018) ‘Integration through crises? A quantitative assessment of the effect of the Eurocrisis on preferences for fiscal integration’, Comparative European Politics, doi:10.1057/s41295-018-0115-41-29.

- Recchi, E. and Favell, A. (2009) Pioneers of European Integration. Citizenship and Mobility in the EU, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Risse, T. (2005) ‘Neofunctionalism, European identity, and the puzzle of European integration’, Journal of European Public Policy 12 (2): 291–309.

- Risse, T. (2010) A Community of Europeans? Transnational Identities and Public Spheres, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Risse, T., Engelmann-Martin, D., Knope, H.J. and Roscher, K. (1999) ‘To Euro or not to Euro? The EMU and identity politics in the European Union’, European Journal of International Relations 5 (2): 147–87.

- Ruggie, G., Katzenstein, P., Keohane, R.O. and Schmitter, P.C. (2005) ‘Transformations in world politics: the intellectual contributions of Ernst B. Haas’, Annual Review of Political Science 8: 271–96.

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2014) ‘European integration in the euro crisis: the limits of postfunctionalism’, Journal of European Integration 36 (3): 321–37.

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2018) ‘Liberal intergovernmentalism and the crises of the European Union’, Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (7): 1578–94.

- Schmitter, P.C. (1969) ‘Three neo-functional hypotheses about international integration’, International Organization 23 (1): 161–66.

- Schmitter, P.C. (2005) ‘Ernst B. Haas and the legacy of neofunctionalism’, Journal of European Public Policy 12 (2): 255–72.

- Schmitter, P.C. (2009) ‘On the way to a post-functionalist theory of European integration’, British Journal of Political Science 39 (1): 211–15.

- Schneider, C.J. and Slantchev, B.L. (2018) ‘The domestic politics of international cooperation: Germany and the European debt crisis’, International Organization 72 (1): 1–31.

- Sinnott, R. (1995) ‘Bringing public opinion back in’, in O. Niedermayer and R. Sinnott (eds), Public Opinion and Internationalized Governance, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 11–31.

- Steenvoorden, E. and Wright, M. (2018) ‘Political shades of ‘we’: Sociotropic uncertainty and multiple political identification in Europe’, European Societies, doi:10.1080/14616696.2018.1552980.

- Stoeckel, F. (2013) ‘Ambivalent or indifferent? Reconsidering the structure of EU public opinion’, European Union Politics 14 (1): 23–45.

- Stoeckel, F. (2016) ‘Contact and community: the role of social interactions for a political identity’, Political Psychology 37 (3): 431–42.

- Vasilopoulou, S. and Talving, L. (2018) ‘Opportunity or threat? Public attitudes towards EU freedom of movement’, Journal of European Public Policy, doi:10.1080/13501763.2018.14970751-19.

- Verhaegen, S. (2018) ‘What to expect from European identity? Explaining support for solidarity in times of crisis’, Comparative European Politics 16 (5): 871–904.

- White, J. (2009) ‘Thematisation and collective positioning in everyday political talk’, British Journal of Political Science 39 (4): 699–709.

- Wilson, I. (2011) ‘What should we expect of “Erasmus generations”?’, Journal of Common Market Studies 49 (5): 1113–40.