ABSTRACT

How well are women represented in the world of political advocacy? Despite the important role of interest groups in modern democracies, the demographic composition of the interest group community remains a blind spot in public policy research. Based on data on over 1000 lobbyists in five European countries, we suggest that the share of women in the world of advocacy is significantly lower than in parliaments. We therefore argue that gender biases in political advocacy need to move high up on the research agenda. As key avenues for future studies, we raise the effects these imbalances have on agenda setting and political decision-making, as well as their symbolic effects on female participation and perceived legitimacy. Moreover, we call for research addressing the complex supply and demand-side factors that cause gender inequalities in lobbying to address this problem in practice.

What does it do to legislative processes and the legitimacy of decisions, if the majority of parliamentarians with the power to suggest, amend and adopt legislation are male? Most scholars of democratic politics and many practitioners today agree that the representation of women in parliaments is something we should be concerned about. ‘Descriptive representation’ (Mansbridge, Citation1999; Pitkin, Citation1967) in legislatures has therefore been the focal point of many academic studies (e.g., Caul, Citation1999; Fortin-Rittberger & Rittberger, Citation2014; Hughes et al., Citation2017).

Yet, parliaments are not the only political institutions to which this concern for descriptive representation applies. Similar assessments have been made about the bureaucracy, which arguably should be broadly reflective of the interests, opinions, needs, and values of the general public in order to have a legitimate claim to participate in the policy process (Keiser et al., Citation2002; Selden, Citation1997). A relative blind spot in the current debate is, however, that such arguments – both based on legitimacy-related reasons and the substantive and symbolic representation of women – also apply to the realm of lobbying.

Interest groups and political advocates today play important roles in modern democracies. They are involved in placing issues on the political agenda (Jones & Baumgartner, Citation2005), supplying knowledge and expertise as policy input (De Bruycker, Citation2016; Flöthe, Citation2020), discussing and framing issues in media debates (Binderkrantz et al., Citation2017; Junk & Rasmussen, Citation2019) and facilitating service provision and implementation (Petersson, Citation2019). Moreover, we can see organized interests as a factor that affects policy change (Baumgartner et al., Citation2009) and the linkage between public opinion and policy (Rasmussen & Reher, Citation2019; Bevan & Rasmussen, Citation2020).

In fact, both in theory and political practice, interest advocates are often expected to function as a ‘transmission belt’ (Truman, Citation1951) and reduce the distance between citizens and institutions in governance (European Commission, Citation2001). To play this role equitably, one can argue that lobbyists should ideally come from a diverse set of backgrounds to be able to link policymaking to different types of constituents. Both input and output legitimacy in political decision-making could be affected by this: First, in order to secure input legitimacy of their consultation practices, parliaments and other decision-makers should receive societal input from a diverse and representative range of actors, i.e., interest groups (Bochel & Berthier, Citation2020). Secondly, there is evidence that the decisions made by descriptively representative bodies are considered as more legitimate by citizens (Arnesen & Peters, Citation2018) and this might also hold for the influence the lobby community exerts over policy outcomes.

In fact, the desirability of including female lobbyist in decision-making has begun to reach political practice: Parliament in the United Kingdom (UK), for instance, actively seeks to include female witnesses in its hearings to improve the legitimacy of its decision-making (Beswick & Elstub, Citation2019). In research, however, the individual characteristics of lobbyists, among others their gender, have received far too little attention. Several important studies have looked at representation through organizations advocating for the interests of women as well as other disadvantaged groups (e.g., Celis et al., Citation2014; Marchetti, Citation2014; Schlozman, Citation1990; Strolovitch, Citation2006). Yet, the general gender composition of the lobbying community has not been subject to enough scholarly scrutiny (for recent exceptions see: LaPira et al., Citation2019; Lucas & Hyde, Citation2012).

We argue in this note that a potential underrepresentation of women in political advocacy is similarly problematic as their underrepresentation in legislatures, cabinets or the bureaucracy. At the same time, the study of gender biases in lobbying raises specific challenges, which – however – should not keep us from addressing them. In the following, we therefore outline important avenues for this research and provide exploratory empirical evidence that we hope will further motivate the study of gender biases in lobbying. Based on a sample of over 1000 political advocatesFootnote1 in five European countries (Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, the United Kingdom), we find that women are strongly underrepresented in the world of advocacy in all these countries. In our total sample, only 23 per cent of the active political advocates on the 50 quasi-randomly selected issues we identified were women. We argue that future research urgently needs to address the substantive and symbolic effects of these gender inequalities in lobbying, as well as their causes at the supply- and demand-side in different arenas of public policy. Moreover, we hope that our arguments about descriptive representation in lobbying are useful for addressing other inequalities, such as class or ethnicity.

Representation on shaky grounds?

One potential reason for why we know surprisingly little about the (under)representation of women in the world of advocacy is that ‘representation’ through interest groups is conceptually more messy than representation through democratically elected representatives. Even for legislators it is not clear-cut whose concerns they (should) most actively represent: be it party members, a local constituency, all citizens, or (wo-)men like themselves (cf. Reingold, Citation1992). Still, the underlying ‘one person, one vote’ principle at least gives a procedural base for a representation relationship and accountability mechanism in legislative representation.

Diversity of constituencies and causes

In contrast, interest groups often lack internal democratic practices and their responsibility to a constituency stands on more shaky grounds, potentially torn between members or (financial) supporters, the acclaimed beneficiaries, and goals of the organization. Put differently, interest groups are essentially ‘self-appointed representatives’ and can arguably only provide democratic representation when they are authorized by and accountable to their affected constituency (Montanaro, Citation2012). This is not the case, and perhaps not even possible, for all constituencies. Halpin (Citation2006) accordingly argues that political advocacy floats between the concepts of ‘representation’ and ‘solidarity’, depending on the type of the constituency.

A related complication for studying gender biases in lobbying stems from the fact that, at the level of individual organizations, gender biases are not necessarily worrisome. Male-dominated lobbying might be very acceptable, if it mirrors a specific member-base (say, ninety percent middle-aged men) and/or cause (say, in a union for construction workers). Similarly, women’s causes may best be represented by women (cf. Celis et al., Citation2014; Phillips, Citation1995) and this might translate into saying that advocacy on some issues, or even in some sectors should have a predominantly female (or male) lobby. At the same time, however, we argue that it is undesirable that the majority of causes, sectors and types of constituents find voice through male advocates. We believe this to be the case, because descriptive representation among lobbyists can affect the legitimacy of democratic decision-making in two important ways:

First, input legitimacy of civil society participation as common in consultation practices of many political institutions will depend on whether the participating actors plausibly represent the underlying society or introduce biases (Bochel & Berthier, Citation2020). As Beswick and Elstub (Citation2019, p. 948) write: ‘It would be difficult to justify the committee inquiry system as fair if the inquiries only included certain types of people and, by extension, only captured a narrow range of experiences and perspectives’.

Second, decisions involving a descriptively representative lobbying community might enjoy higher output and institutional legitimacy. As Arnesen and Peters (Citation2018, p. 868) show, descriptive representation matters for decision acceptability by citizens and can even serve ‘as a cushion for unfavorable decisions’. Relatedly, Scherer and Curry (Citation2010) provide evidence that descriptive representation increases institutional legitimacy in the eyes of disadvantaged groups. In the context of lobbying, we might worry that citizens’ distrust of the undue influence of some groups spills over to their acceptance of political decisions and/or institutions more generally. Descriptive representation in the lobbying community might here be one factor that affects citizen perceptions of the decisions and institutions that are subject to lobbying.

Despite these potentially far-reaching implications, studies of lobbying and political advocacy tend to overlook the issue of descriptive representation. In the following, we therefore address existing gender biases in lobbying and discuss their potential effects and causes. In the next section, we begin by gauging the extent of gender biases based on existing studies and our own empirical evidence across five European countries.

Aggregate gender-biases in lobbying

Existing empirical evidence on gender biases in the lobbying population suggests that the face of political advocacy is predominantly male. A recent study by LaPira et al. (Citation2019) looks at individuals registered to lobby the United States’ (US) federal government and shows that women account for only 37 per cent of these lobbyists. Bochel and Berthier (Citation2020) assess the representation of women in legislative hearings in Scotland and show that around 38 per cent of committee witnesses were women between 2016 and 2017.

Evidence that resulted from our own research projectFootnote2 on government responsiveness in five European countries tentatively suggests that inequalities are even more pronounced in other contexts. Although analyzing gender biases was not the original intention, the project identified the gender of over 1000 individual lobbyists active on 50 quasi-randomly sampled issues.Footnote3 Coders identified whether the names of these active advocates were most likely to belong to a man or a woman.Footnote4

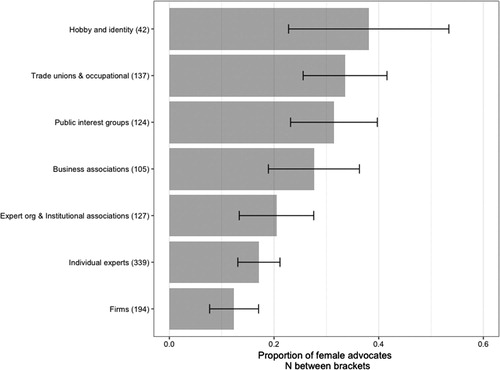

Based on this data, our verdict is that, at an aggregate level cutting across fifty diverse issues, the world of advocacy is still very much a men’s world: only 23 per cent of the representatives of interest groups, businesses and the experts we identified were women. A comparison across the five countries shows that the percentage of female advocates significantly varies across countries, but is low across the board, notably way below the share of female parliamentarians in all respective countriesFootnote5 except the UK (see ).

Figure 1. Proportion of women in advocacy (bars with 95% confidence intervals) and in the main chamber of parliament (triangles).

The highest observed share of female advocates in the countries under study was 30 per cent (Sweden), followed by 28 per cent (Denmark). In the Netherlands and the UK, we observed, respectively, 17 and 23 per cent female lobbyist. In Germany, the share of women even lies as low as one women in every ten lobbyists (10 per cent). While any single one of these shares may reflect some noise, for instance due to the sampled issues, we believe that the consistently low share of women in all five countries is striking.Footnote6

It is also against the background of these empirical patterns, that we want to raise the issue of gender equality in lobbying as a serious problem, which deserves scholarly. In the remainder of this research note, we build on existing literature on gender, representation, and policy-making to point to important avenues for further research on the effects and causes of these gender imbalances.

Substantive and symbolic effects of gender-biased advocacy

Ensuring ‘descriptive representation’ (cf. Mansbridge, Citation1999; Pitkin, Citation1967) among legislators or bureaucrats is often seen as important for both substantive and symbolic reasons. We argue that it is important to ask how these concerns apply to the realm of lobbying.

Substantive representation: from demographics to policy outcomes?

Lower ‘descriptive’ shares of women in the lobbying community have the potential to affect the substantive representation of women’s interests in policy processes and public debates. As Pitkin (Citation1967, p. 89) argues, we ‘tend to assume that people’s characteristics are a guide to the actions they will take’. A number of studies in legislative and bureaucratic contexts have shown that women are more likely to see themselves as representing women’s interests and to advocate these actively (Keiser et al., Citation2002; Reingold, Citation1992).

It is an open empirical question to what extent this also holds for the work of lobbyists: Does their gender affect the behaviour, agendas and positions of female and male advocates? In this respect, future research should also address how much discretion advocates have in their work vis-à-vis their organization, as well as how much (male and/or female) leadership affects lobbying practices.

Ultimately, such research should probe whether gender-biased lobbying actually hinders women’s policy representation – both within lobby groups and in actual policy outcomes. Existing studies give some evidence that female representation in decision-making influences public policy outputs, such as political agenda setting and responsibility for specific issues (Bratton & Ray, Citation2002), or the adoption and scope of specific policies related to maternity and childcare leave (Kittilson, Citation2008). Yet, especially when we look beyond issues with a strong gender dimension, evidence for an effect on women’s policy representation become more mixed (see, for instance, Reher, Citation2018).

One reason for this can be that ‘substantive representation’ is difficult to conceptualize and measure (cf. Golder & Stramski, Citation2010). Moreover, in addition the descriptive shares of women, it is important to ask which acts and actors really are ‘critical’ for the representation of women’s interests (Childs & Krook, Citation2009). Holli (Citation2012), for example, indicates that female recruitment in parliaments does not give female experts and interest groups more access to parliamentary hearings, and should therefore not be seen as a ‘critical act’ for women’s representation.

With respect to lobbying, it is important to enquire whether female recruitment actually enhances the link between female citizens and policy, for instance by transmitting policy-relevant information in two directions: from women to policymakers and vice versa – both of which can affect congruence between opinions and policy. From this perspective, it is also important to ask how organizations’ membership is implicated by gender-biased in lobbying.

A few existing studies have addressed the relationship of (gender) diversity in membership and substantive representation. These studies point to the complex configurations of (dis)advantage related to gender, as well as other socio-economic characteristics (Marchetti, Citation2014; Strolovitch, Citation2006). Ultimately, such research links to the literature on intersectionality in feminist thinking (Nash, Citation2008; Shields Citation2008), addressing how multiple aspects of our identities, i.e., gender, but also ethnic- and economic-background, combine to create advantages or disadvantages in political representation.

Future studies of gender biases in lobbying could apply this concept of intersectionality to the complex cross-cutting allegiances lobbyists may have – as part of the organization, vis-a-vis (different parts of their) membership, based on their own gender and other socio-demographic and identity traits. While this returns us to the shaky grounds of ‘representation’ in political advocacy, it is empirically highly relevant to ask how lobbyists navigate these multiple ties in practice, and how they affect agenda setting and/or position taking in public policy processes.

Symbolic representation: legitimacy of decisions and role-model functions of advocates

Even if future studies were to show that male and female lobbyists working for a given organization differ little in their lobbying practices, there are other reasons to care about a more gender-equal advocacy landscape. First, descriptive representation is likely to be relevant for the legitimacy-related reasons discussed above, that is the (perceived) legitimacy of civil society participation, political decisions and institutions (cf. Arnesen & Peters, Citation2018; Beswick & Elstub, Citation2019; Bochel & Berthier, Citation2020; Scherer & Curry, Citation2010). Future studies should assess these effects in the realm of lobbying.

Secondly, there can be other symbolic effects of a gender-balanced lobbying community. As Mansbridge (Citation1999, p. 652) qualifies, it is important not to see the term ‘symbolic’, as bearing the unspoken modifier ‘mere’. Political benefits that the presence and visibility of women in political work might confer to citizens are potentially consequential for patterns in unequal participation in political activity (cf. Burns et al., Citation2001). Wolbrecht and Campbell (Citation2007), for instance, use data from over 20 nations to show that where there are more female members of parliament, women are more likely to discuss and participate in politics, and girls are more likely to intend to participate in politics as adults.

Similar effects might hold for the world of advocacy. Like governing and partisan actors, interest groups are prominent voices in public debates and may therefore contribute to (de-)motivate female citizens to get involved in policy discussions. Future research should address what it does to both the perceived legitimacy of political outcomes and the participatory aspirations of women to witness a male-dominated sphere of lobbying and political advocacy.

Variation between actor types and political arenas

For such legitimacy-related, symbolic, and substantive consequences of gender biases, it is also relevant to ask whether and how the share of female advocates varies in different arenas of policy-making and/or different types of advocates. Our dataset from the [name] project also allows us to explore such variation.

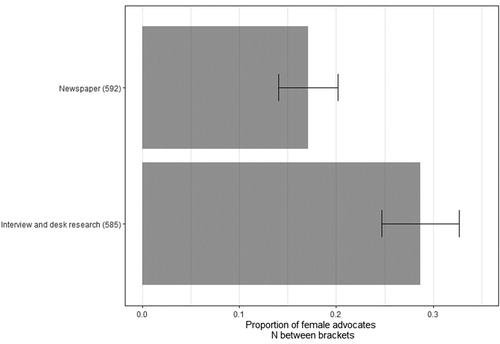

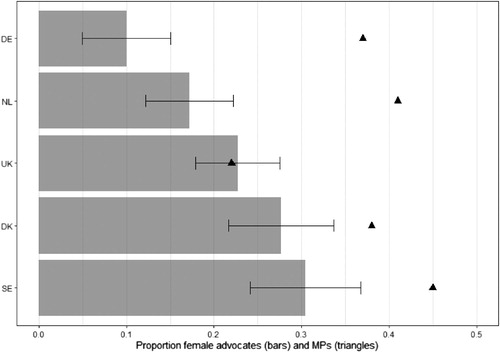

First, we looked at what kind of political advocates are predominantly male. As shows, we distinguish seven different types of advocacy actors, and for none of them there is gender parity. Yet, there is notable variation: In our sample, hobby and identity groups have the highest shares of female representatives, i.e., 38 per cent of women, whereas we identified the lowest share of female advocates among firms (12 per cent).

This very low share of women advocating on behalf of companies is in line with findings from survey research on the US (e.g., Lucas & Hyde, Citation2012), and variation across advocacy types is also suggested in other studies (LaPira et al., Citation2019; Nownes & Freeman, Citation1998). In our view, it is important to address the effects of these patterns on the perception of gender roles and career aspirations, as well as perceived organizational profiles, and ultimately, advocacy success. What does it do to the policy process, that hobby, identity and public interest groups are significantly more likely to be represented by female advocates than expert and firms?

In addition to actor type, we explored whether the underrepresentation of women varies between policy arenas. To do this, we compared the different sources in which we identified active actors: statements in the media (i.e., outside lobbying) and actors identified in desk research on consultations and hearings or interviews with policy-makers (inside lobbying). As shows, only 17 per cent of the political advocates we identified in the media are women, whereas 29 per cent of actors identified in consultations and through interviews with policy-makers were female.

This difference could be important from a perspective of symbolic representation, and future research should address the effects this has on participation of women in policy debates. Moreover, it would be fruitful to address the intersections of policy arenas, actor types, and gender stereotypes. Danielian and Page (Citation1994) famously found that TV news is dominated by corporations and business groups. Moreover, they suggested that ‘business sources were portrayed as presenting sober, factual, dispassionate positions in contrast to the emotional and often disorderly demonstrations by citizens’ action groups’ (Danielian & Page, Citation1994, p. 1072). What is the gender dimension in such different portrayals of interest group input? Do they persist in the twenty-first century and, if so, why?

Supply and demand-side drivers of gender imbalances in lobbying

In our view, another important avenue for future research lies in exploring the mechanisms explaining gender biases in lobbying, both in terms of access to decision-makers, and selection and admission into the profession.

Potential demand-side mechanisms

On the one hand, political and media gatekeepers may favour male advocates. Research in media studies has long pointed to the tendency of journalists to use more male than female sources (e.g., Zoch & Turk, Citation1998) and the gender stereotypes triggered in news reporting (e.g., Armstrong & Nelson, Citation2005). Yet, scholars of political advocacy rarely analyze the implications these patterns have for lobbying practices.

Regarding inside lobbying, it is not clear whether women get less access than men. Hanegraaff et al. (Citation2017) show that organizations with large proportions of female members are less likely to be consulted by Dutch policymakers, but they do not assess the gender of lobbying staff. Studies on US lobbying staff actually suggest the opposite: Bath et al. (Citation2005) show based on survey data that female lobbyists in Washington are more frequently approached by policymakers than men. Similarly, Nownes and Freeman (Citation1998) suggests that female lobbyists have just as much access to policymakers as male lobbyists, are taken just as seriously, and are approached by policymakers for advice more often than men. These findings tentatively indicate that policymakers in the US already actively counter gender biases in lobbying.

A new study by LaPira et al. (Citation2019) adds, however, that access of male and female lobbyists varies in the spheres of policy and politics. While women advance similarly well in positions related to policy discussions (e.g., identifying problems, developing solutions), the politics part of lobbying (i.e., campaign consulting, fundraising, and party-building activities) remains predominantly male. Since such politics can provide career opportunities, these imbalances advantage male lobbyists.

Potential supply-side mechanisms

At the same time, it is important to ask to what extent supply-related reasons in recruitment and career choice drive the underrepresentation of women in the lobbying.

Women may be less likely to be socialized into working as lobbyists compared to men. According to Schlozman, lobbying can be seen as ‘a kind of old-boy political network’ (Citation1990, p. 339), which might make it less likely for women as a career choice. In turn, women may be less likely to get hired into existing networks since these may recruit candidates that are similar to themselves (LaPira et al., Citation2019).

On the other hand, especially for member-based organizations, imbalances in hiring may also be a reflection of mobilization bias at the membership level. Hanegraaff et al. (Citation2017) suggest that there is a considerably higher share of organizations with a largely male membership (23 per cent of the organizations), than organizations with a largely female membership (12 per cent) among Dutch interest groups. If organizations with a gendered membership hire descriptively representative staff, this might account for gender biases in active lobbying. Yet, the direction of causality is not clear here: Imbalances in member mobilization may also be caused by male-dominated advocacy activities, if gendered lobbying has the symbolic effects we discussed earlier. Instead of looking at the effects of supply and demand-side factors separately, future research should therefore ideally combine such aspects.

Conclusion

More than 20 years ago, Burrell (Citation1996) argued, that women ‘in public office stand as symbols for other women, both enhancing their identification with the system and their ability to have influence within it’. In this research note, we have argued that these concerns also apply to women in policy advocacy, but that the reality of lobbying, in practice, still very much resembles a men’s world – with only 23 per cent female lobbyists in the sample we studied.

We therefore suggest a number of important avenues for future research on the effects and causes of these gender imbalances in lobbying. First, we highlighted the importance to study the substantive consequences, i.e., effects on agenda setting and input for decision-making by male and female lobbyists, as well as other intersecting socio-economic characteristics. Second and equally importantly, we stressed implications for the symbolic representation of women in terms of female participation in policy discussions, career aspirations and the legitimacy of resulting decisions. We argued further that variation across policy arenas and actor types will be relevant for such symbolic and substantive consequences and the potentially gendered image lobbying receives. Third, we argued that future research needs to address the complex supply- and demand-side factors that explain low activity in and/or access of women to the sphere of lobbying. Ultimately, we hope that such research will help to address these biases at the supply and/or demand side in practice. Moreover, while our discussions primarily addressed gender inequalities, we hope they will also inform work on other dimensions like income and educational inequalities, as well as ethnicity and intersections between different inequalities.

Supplemental Appendix

Download MS Word (36.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The manuscript benefited from feedback from our anonymous referees and Michael Blauberger. We thank Linda Flöthe, Lars Mäder, Stefanie Reher, Mikkel Wolfsberg and our army of terrific student assistants for their involvement in the GovLis project. They all contributed to the data collection and to creating a stimulating research environment the last years.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Wiebke Marie Junk

Wiebke Marie Junk is an Assistant Professor at the University of Copenhagen. Her research interests lie in the fields of public policy, European Union and global governance, and revolve especially around the involvement of non-state actors.

Jeroen Romeijn

Jeroen Romeijn is a PhD candidate at Leiden University. His research focus is on the representative role of political parties and other possible aggregators of public preferences like interest groups.

Anne Rasmussen

Anne Rasmussen is a Professor at the University of Copenhagen and affiliated to Leiden University and the University of Bergen. Her research focuses on political representation with a particular interest in the role of interest groups, electronic communication and inequalities between citizens.

Notes

1 These include interest associations, firms, think tanks and researchers involved in policy debates.

2 We rely on data from the GovLis project. For more information see www.govlis.eu.

3 For information on issue sampling and data collection see Online Appendix A.1.

4 While we might incidentally wrongly assign a gender to individuals who do not self-identify as such, we assume these errors to be unlikely to substantially bias our estimates of the general gender balance.

5 We compare the proportion of female advocates in our sample to the proportion of female national parliamentarians in the five countries in the year 2010, i.e., the middle of our observation period (2006–2014).

6 We also compared the 10 issues with most advocacy activity (Online Appendix, Table A.2). For none of them, there is gender parity. For 9/10 of these issues, the share of female lobbyists lies below 35 per cent.

References

- Armstrong, C. L., & Nelson, M. R. (2005). How newspaper sources trigger gender stereotypes. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 82(4), 820–837. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900508200405

- Arnesen, S., & Peters, Y. (2018). The legitimacy of representation: How descriptive, formal, and responsiveness representation affect the acceptability of political decisions. Comparative Political Studies, 51(7), 868–899. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414017720702

- Bath, M. G., Gayvert-Owen, J., & Nownes, A. J. (2005). Women lobbyists: The gender gap and interest representation. Politics & Policy, 33(1), 136–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-1346.2005.tb00212.x

- Baumgartner, F. R., Berry, J. M., Hojnacki, M., Kimball, D. C., & Leech, B. L. (2009). Lobbying and policy change: Who wins, who loses, and why. University of Chicago Press.

- Beswick, D., & Elstub, S. (2019). Between diversity, representation and ‘best evidence’: Rethinking select committee evidence-gathering practices. Parliamentary Affairs, 72(4), 945–964. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsz035

- Bevan, Shaun, & Rasmussen, Anne. (2020). When does government listen to the public? Voluntary associations and dynamic agenda representation in the United States. Policy Studies Journal, 48(1), 111–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12231

- Binderkrantz, A. S., Bonafont, L. C., & Halpin, D. R. (2017). Diversity in the news? A study of interest groups in the media in the UK, Spain and Denmark. British Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 313–328. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123415000599

- Bochel, H., & Berthier, A. (2020). A place at the table? Parliamentary committees, witnesses and the scrutiny of government actions and legislation. Social Policy and Society, 19(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746418000490

- Bratton, K. A., & Ray, L. P. (2002). Descriptive representation, policy outcomes, and municipal day-care coverage in Norway. American Journal of Political Science, 46(2), 428–437. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088386

- Burns, N., Schlozman, K. L., & Sidney, V. (2001). The private roots of public action: Gender, equality, and political participation. Harvard University Press.

- Burrell, B. (1996). A woman’s place is in the house: Campaigning for congress in the feminist era. University of Michigan Press.

- Caul, M. (1999). Women’s representation in parliament. Party Politics, 5(1), 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068899005001005

- Celis, K., Childs, S., Kantola, J., & Krook, M. L. (2014). Constituting women’s interests through representative claims. Politics & Gender, 10(2), 149–174. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X14000026

- Childs, S., & Krook, M. L. (2009). Analysing women’s substantive representation: From critical mass to critical actors. Government and Opposition, 44(2), 125–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2009.01279.x

- Danielian, L. H., & Page, B. I. (1994). The heavenly chorus: Interest group voices on tv news. American Journal of Political Science, 38, 1056–1078. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111732

- De Bruycker, I. (2016). Pressure and expertise: Explaining the information supply of interest groups in eu legislative lobbying. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(3), 599–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12298

- European Commission. (2001). European Governance: A White Paper. COM(2001)428, Brussels.

- Flöthe, L. (2020). Representation through information? When and why interest groups inform policymakers about public preferences. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(4), 528–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1599042

- Fortin-Rittberger, J., & Rittberger, B. (2014). Do electoral rules matter? Explaining national differences in women’s representation in the european parliament. European Union Politics, 15(4), 496–520. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116514527179

- Golder, M., & Stramski, J. (2010). Ideological congruence and electoral institutions. American Journal of Political Science, 54(1), 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00420.x

- Halpin, D. R. (2006). The participatory and democratic potential and practice of interest groups: Between solidarity and representation. Public Administration, 84(4), 919–940. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2006.00618.x

- Hanegraaff, M., Berkhout, J., & Van Der Ploeg, J. (2017). Who is Represented? Explaining the Demographic Structure of Interest Group Membership. In: ECPR general conference, Oslo.

- Holli, A. M. (2012). Does gender have an effect on the selection of experts by parliamentary standing committees? A critical test of “critical” concepts. Politics & Gender, 8(3), 341–366. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X12000347

- Hughes, M. M., Paxton, P., & Krook, M. L. (2017). Gender quotas for legislatures and corporate boards. Annual Review of Sociology, 43(1), 331–352. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-060116-053324

- Jones, B. D., & Baumgartner, F. R. (2005). The politics of attention. University of Chicago Press.

- Junk, W. M., & Rasmussen, A. (2019). Framing by the flock: Collective issue definition and advocacy success. Comparative Political Studies, 52(4), 483–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018784044

- Keiser, L. R., Wilkins, V. M., Meier, K. J., & Holland, C. A. (2002). Lipstick and logarithms: Gender, institutional context, and representative bureaucracy. American Political Science Review, 96(3), 553–564. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055402000321

- Kittilson, M. C. (2008). Representing women: The adoption of family leave in comparative perspective. The Journal of Politics, 70(2), 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1017/S002238160808033X

- LaPira, T. M., Marchetti, K., & Thomas, H. F. (2019). Gender politics in the lobbying profession. Politics & Gender, OnlineFirst, 1–29. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X19000229

- Lucas, J. C., & Hyde, M. S. (2012). Men and women lobbyists in the American states. Social Science Quarterly, 93(2), 394–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2012.00841.x

- Mansbridge, J. (1999). Should blacks represent blacks and women represent women? A contingent “yes”. The Journal of Politics, 61(3), 628–657. https://doi.org/10.2307/2647821

- Marchetti, K. (2014). Crossing the intersection: The representation of disadvantaged identities in advocacy. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 2(1), 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2013.876919

- Montanaro, L. (2012). The democratic legitimacy of self-appointed representatives. The Journal of Politics, 74(4), 1094–1107. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381612000515

- Nash, J. C. (2008). Re-thinking intersectionality. Feminist Review, 89(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1057/fr.2008.4

- Nownes, A. J., & Freeman, P. K. (1998). Female lobbyists: Women in the world of “good ol’ boys”. The Journal of Politics, 60(4), 1181–1201. https://doi.org/10.2307/2647737

- Petersson, M. T. (2019). Transnational partnerships’ strategies in global fisheries governance. Interest Groups & Advocacy, Online First.

- Phillips, A. (1995). The politics of presence. Clarendon Press.

- Pitkin, H. F. (1967). The concept of representation. University of California Press.

- Rasmussen, A., & Reher, S. (2019). Civil society engagement and policy representation in Europe. Comparative Political Studies, Online First.

- Reher, S. (2018). Gender and opinion–policy congruence in Europe. European Political Science Review, 10(4), 613–635. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773918000140

- Reingold, B. (1992). Concepts of representation among female and male state legislators. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 17(4), 509–537. https://doi.org/10.2307/439864

- Scherer, N., & Curry, B. (2010). Does descriptive race representation enhance institutional legitimacy? The case of the U.S. Courts. The Journal of Politics, 72(1), 90–104. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381609990491

- Schlozman, K. L. (1990). Representing women in Washington: Sisterhood and pressure politics. In L. A. Tilly & P. Gurin (Eds.), Women, politicsm and change (pp. 339–382). Russel Sage Foundation.

- Selden, S. C. (1997). The promise of representative bureaucracy: Diversity and responsiveness in a government agency. ME Sharpe.

- Shields, S. A. (2008). Gender: An intersectionality perspective. Sex Roles, 59(5), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9501-8

- Strolovitch, D. Z. (2006). Do interest groups represent the disadvantaged? Advocacy at the intersections of race, class, and gender. Journal of Politics, 68(4), 894–910. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00488.x doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00478.x

- Truman, D. B. (1951). The governmental process. Political interests and public opinion. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Wolbrecht, C., & Campbell, D. E. (2007). Leading by example: Female members of parliament as political role models. American Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 921–939. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00289.x

- Zoch, L. M., & Turk, J. V. (1998). Women making news: Gender as a variable in source selection and use. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 75(4), 762–775. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909807500410