?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper analyses how corporations appear in media coverage on six policy domains through a complexity lens in two major British newspapers between 2012 and 2017. Corporations are often thought to avoid press coverage, though another strand of literature indicates that they dominate the news compared to other organized interests. We argue that corporations use multiple lobby strategies including media strategies in order to maximize influence. They do so to signal technical expertise to specific constituencies that is not necessarily accessible to the general public. The results show that corporations are more likely to be involved in news coverage that is technical in nature which is an important finding as it tells us more about the media involvement of key players in the political process. Yet, this coverage is not necessarily less accessible which is a positive finding for the functioning of our democracies.

Introduction

Why do corporations employ media strategies? Addressing this question is important as corporations are key players in contemporary Western democracies. They are found to dominate political systems in different institutional settings, such as pluralist (Baumgartner & Leech, Citation2001; Berkhout et al., Citation2018; Chalmers, Citation2013; Salisbury, Citation1984; Schlozman, Citation1984) and corporatist contexts (Aizenberg & Hanegraaff, Citation2020a). What is more, they have managed to expand their access to politics over time (Gray et al., Citation2004; Gray & Lowery, Citation2001; Madeira, Citation2016), and tend to not only dominate insider channels but are quite prominent participants when it comes to outsider platforms as well (Aizenberg & Hanegraaff, Citation2020b; Danielian & Page, Citation1994).

Corporations’ individual involvement in politics can harm the functioning of our democracies, even more so when it comes to their engagement in the public debate. That is, when lobbying alone, corporations tend to focus on narrow and self-oriented issues compared to encompassing matters when lobbying via business associations and this can in turn lead to fragmented interest systems (Gray et al., Citation2004; Hart, Citation2004; Martin & Swank, Citation2004, p. 598; Salisbury, Citation1984; and see Wilson, Citation1973, p. 310 for a similar argument). When they are involved in the public debate via the news media, it is likely that they voice such concerns as well. What is more, scholarly work on interest group visibility in the media illustrates that there is already an overrepresentation of economic groups in the media (Binderkrantz et al., Citation2015; De Bruycker & Beyers, Citation2015), and when corporations are added as a category, such skewness becomes stronger. This is problematic as most citizens learn about politics via the news media (Carpini & Keeter, Citation1996 and see Kleinberg & Lau, Citation2019 for a more recent discussion), and for a democracy to function at its best, citizens need access to a wide range of different ideas so that they can form well-informed and reasoned opinions about politics and policy-making (Danielian & Page, Citation1994).

There are two important strands of literature that speak to corporations’ visibility in the media and their employment of public strategies, such as using the media, and these give a puzzling picture. Before introducing these, it is important to note that students of organized interests are thought to focus relatively more on groups with members as compared to corporations (see Hart, Citation2004, p. 47). In this context that means that when business interests are studied, there is a focus on business associations – organizations with corporations as members – in comparison to corporations as individual political actors. In a European context, corporations have been studied by interest group scholars to an even more limited extent (but see Bernhagen & Mitchell, Citation2009; Bouwen, Citation2004, Citation2002; Coen, Citation1997; Grant, Citation1982 and Aizenberg & Hanegraaff, Citation2020a for a recent overview and discussion of studies in this context on corporate lobbying).

This is not different in the literature that the current endeavor seeks to engage with. That is, in both of the literature strands on outside strategies and media appearance, especially those studies conducted in the European context, there is a focus on mechanisms of business associations when referring to the representation of business interests (Beyers, Citation2004; Binderkrantz, Citation2012; Binderkrantz et al., Citation2015; Binderkrantz et al., Citation2017; Kriesi et al., Citation2007). This study therefore partially departs from insights from the studies of business association strategies and media appearance as well and derives and tailors arguments that more specifically refer to interest representation strategies of corporations. A first line of research focuses on strategies that organized interests pursue through publicly visible arenas. This strand of literature suggests that citizen groups tend to prevail in public arenas, whereas business interests tend to focus on platforms that are less visible to the public in order to get their way (Dür et al., Citation2015, p. 958; Salisbury, Citation1984). Business interests and corporations more specifically are thought to oftentimes avoid the public spotlight in order to reduce the likelihood of facing public scrutiny concerning their legitimacy (see Hart, Citation2004; Hula, Citation1999; Mitchell et al., Citation1997). A second branch of literature studies aggregate patterns of visibility of organized interests in the media, and shows that media attention to groups is skewed toward economic groups such as business associations and that corporations are especially overrepresented (Aizenberg & Hanegraaff, Citation2020b; Binderkrantz et al., Citation2017; Danielian & Page, Citation1994; De Bruycker & Beyers, Citation2015). While corporations are thus thought to prefer insider strategies, they are found to often be the most dominant players in the news media. How should we interpret these two contrasting views?

In order to understand these two views better, this paper asks in which contexts corporations use media strategies. It does so by building on the important knowledge that we have on lobbying success. That is, we know that attempts to influence policy-making are more successful when multiple strategies are involved (Baumgartner & Leech, Citation1998; Beyers, Citation2004; Kriesi et al., Citation2007, p. 53). This article argues that corporations use both insider and media strategies in order to maximize the odds of getting their way. However, when pursuing media strategies, they do so with a specific aim: to signal technical expertise to specific constituencies such as policy-makers or business élites. This phenomenon is described by Beyers (Citation2004) as information politics: the presentation of information that is not necessarily addressed to the public at large but to smaller target groups. We also expect that with the shift from descriptive to interpretive journalism, the demand for expert knowledge among journalists has increased (see Albæk, Citation2011; Patterson, Citation2000). When journalists contact organized interests during research for political news coverage, we believe that business interests are more likely to be contacted than other types of organized interests such as NGOs on matters that are more technical in nature, because of their core activities (Bouwen, Citation2002; De Bruycker, Citation2016). As a consequence, we expect that the coverage in which corporations appear is more technical in nature, and less accessible to the public at large, compared to coverage in which other organized interests appear. The paper tests this by analyzing the appearance of corporations and other types of organized interests in 35,674 newspaper articles on six different policy areas in terms of degrees of technicality and accessibility, which are two different measures of complexity.

Media strategies and the visibility of corporations

Scholarly work that speaks to the involvement of corporations in the political media debate can be roughly categorized into two lines of research. A first branch of work speaks to the strategies that corporations undertake to engage in the public debate. These are also known as outsider strategies (Kollman, Citation1998; Trevor Thrall, Citation2006), and can be defined as strategies in which organized interests engage in order to ‘mobilize public support, stimulate grassroots activity, and generate favorable media attention to issues in order to exert pressure on policymakers’ (Trevor Thrall, Citation2006, p. 407). Such strategies are rooted in the political resource of protest and are deemed as important tools for citizen groups and organized interests that represent the ‘powerless’ (Wilson, Citation1973) – that is, groups which do not have enough resources to bargain with, and hence lack the ability to influence the policy-making process (Wilson, Citation1973). More well-endowed groups which do have the resources to establish an important insider position are in turn thought to oftentimes rely less on outsider strategies. That is, business interests, and corporations more specifically, are thought to avoid conflict and are therefore less keen to be seen in visible arenas such as the media (Bernhagen & Trani, Citation2012; Dür et al., Citation2015; Heinz et al., Citation1993; Salisbury, Citation1984). According to some, corporations shy away from the media arena in order to avoid scrutiny from the public concerning their legitimacy (Hart, Citation2004; Hula, Citation1999; Mitchell et al., Citation1997). In summary, according to this strand of literature, corporations are not too inclined to involve themselves in the media arena.

A second strand of literature is concerned with aggregate patterns of visibility of organized interests and most notably the degree of diversity (or lack thereof) therein. This strand of work stems from one of the most crucial questions that has shaped the work of many political scientists and those studying the interest system more specifically. That is, ever since Schattschneider (Citation1960) coined the idea of bias in the interest group system, many scholars have been trying to describe what such bias in the interest group system looks like, and have aimed to arrive at a yardstick against which to assess the extent of bias (Lowery et al., Citation2015). This work resonates in the studies of scholars that have been trying to determine the extent of bias; that is, assessing the distribution of organized interests in different venues across different countries, time and venues (e.g., Berkhout et al., Citation2018; Binderkrantz et al., Citation2015). When it comes to political venues, scholars have been analyzing the distribution of different types of organized interests in parliament and the bureaucracy (Binderkrantz et al., Citation2015; Bouwen, Citation2004), which indicates that the degree of access is skewed toward economic groups and especially toward corporations (Aizenberg & Hanegraaff, Citation2020a; Baumgartner & Leech, Citation2001; Berkhout et al., Citation2018; Chalmers, Citation2013; Gray et al., Citation2004; Salisbury, Citation1984). A similar image is sketched by political scientists studying the news media (Aizenberg & Hanegraaff, Citation2020b; Binderkrantz et al., Citation2017; Danielian & Page, Citation1994; Trevor Thrall, Citation2006; Van der Graaf et al., Citation2016).

The latter line of research suggests that while corporations prefer to use insider strategies, they tend to dominate the media arena, even more so than business associations (Danielian & Page, Citation1994 and see Aizenberg & Hanegraaff, Citation2020b for a recent empirical test and discussion). An explanation is that corporations do pursue outsider strategies next to insider strategies in order to maximize influence (Kriesi et al., Citation2007). When they do so, they benefit from the advantaged position that business has in politics (Lindblom, Citation1977), and are able to mobilize quicker than encompassing interests as they experience less collective action problems (Olson, Citation1965). In addition, due to corporations’ established insider positions, it might be easier for them to gain access to journalists, as the latter are more inclined to report on powerful actors (Binderkrantz, Citation2012; Galtung & Ruge, Citation1965).

While explanations for why corporations are successful in gaining access to media outlets are abundant, less is known about why corporations employ media strategies. This paper argues that corporations use the media as part of their lobbying endeavors to maximize influence, and when they do so, they aim to signal their technical expertise to specific constituencies. This argument is based on a distinction that is made in the literature regarding the different types of information that organized interests supply, and the target groups of their lobbying endeavors. The next section will discuss these differences as well as the other side of the coin, that is: the journalists that decide which groups make the news and thus function as important gatekeepers. It then presents the arguments that this paper aims to test.

Information politics as a media strategy and journalists’ demand for expert knowledge

In order to understand the strategies of interest groups behind the interactions between them and their publics, one needs to understand two important elements: the aim of the lobbying endeavor, and its target group. That is, what do the interest groups want to achieve, and who are they targeting? When groups aim to mobilize the public in order to put pressure on policy-makers, the odds are that they will use an outsider strategy such as interacting with the media in order to expand the scope of conflict (see e.g., Kollman, Citation1998). When instead groups seek to keep the scope of conflict small, interacting directly with policy-makers makes more sense.

The two questions outlined above also matter for the type of information that is used in interest groups’ lobbying endeavors. Political scientists working on modes of information supply of interest groups tend to make a distinction between two types of information that is used in the lobbying endeavors of organized interests: technical information, and political information (see Chalmers, Citation2011; De Bruycker, Citation2016). The first type is predominantly used in expertise-based exchanges between lobbyists and policy-makers (De Bruycker, Citation2016). The second type is thought to be used in instances where lobbyists want to signal to policy-makers that there is support, or indeed opposition, from the public on an issue (De Bruycker, Citation2016). As corporations are thought to prefer to avoid the public spotlight in order to decrease the risk of receiving criticism regarding their legitimacy, using outsider lobbying strategies therefore seems at odds with their usual behavior. How can we then explain their dominance in the media arena?

This paper departs from the idea that corporations seek to maximize influence by using multiple strategies (Baumgartner & Leech, Citation1998; Beyers, Citation2004; Kriesi et al., Citation2007), meaning that they combine insider and outsider strategies. We argue here that corporations mainly use media strategies to signal expertise through the transmission of technical information to specific constituencies such as policy-makers or financial élites. This argument is based on a concept developed by Beyers (Citation2004) that can be referred to as information politics. He states that differences exist between public strategies. Voice strategies occur in arenas that are visible to the public (Beyers, Citation2004, p. 214). The author then further distinguishes between information politics and protest politics. What these two concepts have in common is that they both involve public presentation of information. While protest politics ‘implies the explicit staging of events in order to attract attention and expand conflict’ (Beyers, Citation2004, p. 214), information politics is meant to signal expertise to specific target groups such as business élites or policy-makers and is not necessarily addressed to the public at large (Beyers, Citation2004).

Though it might be the aim of corporations to appear in the news, they depend on the gatekeepers for these news appearances; that is, the journalists. It is therefore of utmost importance to discuss the other side of the coin, namely how journalists decide who to include in their news coverage. Organized interests are an important source of information for journalists (see Berkhout, Citation2013; Gamson & Wolfsfeld, Citation1993). This is especially so given the change in news reporting from descriptive towards interpretative journalism, wherein journalists are required to act as analysts, rather than observers (Albæk, Citation2011; Patterson, Citation2000). As a result, journalists are more inclined than earlier to consult experts on issues in order to receive help in interpreting the news (Albæk, Citation2011). Such experts can be researchers, or economists, and organized interests could also function as experts. Here we expect that when journalists interact with organized interests, they are keener to consult business interests when covering economic or technical matters compared to other types of organized interests such as NGOs. We expect this as business interests have more knowledge on these matters compared to other types of groups, because of their economic and technical core activities (Bouwen, Citation2002; De Bruycker, Citation2016).

Our first argument relates to both the aims of corporations when using media strategies and the expert input that journalists demand. We expect that corporations seek to maximize influence but in a manner that does not necessarily expand the scope of conflict, instead having a rather specific goal: to signal their expertise to smaller target groups through the transmission of technical information. In turn, we pose that journalists are keener to consult business interests compared to other types of organized interests on technical matters and tend to be perceptive to corporations’ media strategies. As a result of both phenomena, we pose that:

H1: Corporations are more likely to appear in news coverage that is technical in nature compared to other types of organized interests.

The second argument relates to the accessibility of the coverage in which corporations appear. That is, we expect corporations to employ media strategies in a manner that does not seek to address the general public but is meant for specific constituencies. Text accessibility has been shown to decrease when the authors or subjects have been trying to shield themselves against public scrutiny (Owens et al., Citation2013). We therefore expect that they aim to be included in coverage that is not necessarily accessible to the public at large, to avoid the risk of expanding conflict while still speaking to their specific target group. At the same time, and as highlighted, we expect that journalists are keener to consult business interests on issues that are more technical, and such coverage might therefore not be as accessible to the general reader compared to coverage on issues that are less technical in nature. We therefore pose that:

H2: Corporations are less likely to appear in news coverage that is highly accessible compared to other types of organized interests.

Data and methods

The research draws on data displaying the media visibility of corporations compared to various types of organized interests on six different policy issues in two British daily newspapers, the Guardian and The Times, between 2012 and 2017. We selected these two newspapers based on their focus on policy issues, their wide circulation, and because they cover center-left (Guardian) and center-right (The Times) viewpoints and agendas.Footnote1 The policy issues were selected from the policy issue categories of the Comparative Agendas Project (Baumgartner et al., Citation2011). The policy issues that were included are: energy; environment; education; transportation; community development and housing issues; and law, crime and family issues.

The articles went through two search filters to make sure that they focus on institutions involved in policymaking, and on the specific policy areas that we wanted to sample. We therefore first sampled a general set of news articles focusing on U.K. policymaking institutions, using a general search string that included references to these institutions (N = 49,804).Footnote2 In a second step, we constructed search strings for each policy issue that we then applied to the sample of policy-related news, to create subsamples of articles that cover the policy issues of interest.Footnote3 This resulted in a dataset of 35,674 articles, which were subsequently stored in a NoSQL database called AmCAT (van Atteveldt, Citation2008). To ensure validity of the different search strings, 30 articles per string were coded according to whether they did indeed cover the particular policy issues. Two independent coders coded the same article sets in order to ensure the reliability of the coding. Both validity and reliability scores range from acceptable to good.Footnote4

To detect corporations in the selected news articles, we used a query approach.Footnote5 The U.K. parliament publishes a register of all meetings of public and private organizations with Members of Parliament and ranking officials within the ministries.Footnote6 The meetings are labeled with the policymaking institution that they are most closely linked to. We subsequently matched the sampled issue categories of our news database with the labels of the meeting registry. Using the names of the organizations that have met with the officials included in the register, we ran queries in the subsamples of news articles that cover the corresponding policy issues to detect mentions of these organizations in the coverage.Footnote7

Since the organizations in the registry have not been categorized into any subcategories, we hand-coded the resulting matches (i.e., appearances of organizations in newspaper articles) into one of these categories: non-governmental organizations (NGOs), business associations, corporations, unions, (professional) membership organizations, research bodies and think tanks, and groups of institutions and authorities (GIAs). The news article metadata was re-matched with the classified search results to ensure that no errors occurred in the matching and classification process, resulting in a final dataset of 13,463 news articles that contain mentions of organizations.

The dependent variable of this study is based on the database mentioned above and measures the number of mentions of corporations in each newspaper article compared to the other organized interests identified in the text corpus. We therefore excluded all articles that did not mention any organization contained in our queries. Whilst using a percentage as a dependent variable makes the statistical analyses potentially more difficult, this way of measuring corporation appearance accounts both for text length and organizational dominance: if one used a simple count of appearances, longer texts would probably result in higher counts. At the same time, by counting the appearance of other types of organizations than just corporations, and then weighing these against the appearance of corporations, we ensure that we know whether corporations dominate an article or not. Simply counting the appearance of corporations would mean that we lose such relativizing information (summary statistics in Appendix A).

We conceptualized text complexity as a two-component measure. We separated it into two sub-measures addressed by the two hypotheses (H1: text technicality, H2: text readability). Text technicality aims to capture the complexities of text as they relate to the actual informational content of the text. Ideally, a text technicality measure would detect if a text contains much specialist knowledge that is relatively inaccessible to non-specialists on a given subject. Following from this definition, text A is more technically complex than text B if it contains more information (also referred to as entropy) within the same unit of text (either sentences, words, or characters). Text readability relates to complexities in text as they relate to the structure of the text. If the text is readable, there are few obstacles within the text that make reading difficult. Such obstacles could be unfamiliar (or highly specialized) words, long words, or long sentences with lots of inner-sentence, word-relational information.

There is a large variety of measures that aim to capture how technical or readable a text is, depending on the specific measure. Whilst text technicality formulas usually measure the variety of the vocabulary, text readability formulas focus on how familiar and accessible the text structure is for the (expected) readership. Most measures were developed for specific applications (e.g., readability of manuals or school books). Since there is no measure that was developed to measure technical complexity in newspaper texts, we calculated the most common text technicality measures for all newspaper articles in our sample using the quanteda library for RStudio (Benoit et al., Citation2018) to select the measure that most closely measures the information-rich technicality that we have described above. We sampled the most widely used measures and checked whether the scores correlated with our own assessment of the technicality of the articles (i.e., if measure X predicts high complexity, is the text indeed complex according to our standards?). We eventually chose Carroll’s Corrected Type-Token ratio (CTTR) as the best formula to capture technical complexity in policy-focused newspaper articles (Carroll, Citation1964). This formula measures how many unique words (i.e., types) appear in a text in relation to the overall number of words (i.e., tokens):

It includes a term that corrects for increasing text length as the likelihood that any particular word will be repeated naturally increases as the text gets longer. A high CTTR therefore signals a high technical complexity of the text, whilst a low CTTR signals less technical complexity. This happens because if a text contains many unique words, it contains much information on a variety of matters.

We proceeded in the same way to select a text readability formula. In contrast to text technicality measures, readability formulas typically measure either how long words are or how familiar they are to the average reader (via dictionaries). The Coleman-Liau index provided the most precise results to assess how accessible a text was for readers of the newspaper articles in our sample (Coleman & Liau, Citation1975). This test was initially used to assess the readability of U.S. high school educational material and has become one of the most widely used readability measures. It combines measures on the average word length (based on characters) and the length of the average sentence, and includes correction terms to scale results:

To ensure the validity of both our key independent variables, we manually coded a sample and conducted intercoder reliability checks between two coders and the predictions of our measures (Appendix F). The subsequently calculated Cohen’s Kappa values are within the acceptable range, showing that our chosen measures indeed measure technicality and readability. We furthermore controlled for a number of alternative explanatory variables. To control for the varying degree of ‘competition for attention’ in the different policy fields, we included both the diversity (Shannon entropy, see Shannon, Citation1948) as well as the density (number of organizations) of the stakeholder population in each of the policy fields in our news dataset. We furthermore controlled for the newspaper outlet, as the two publications under observation might attract different kinds of stakeholders to their coverage. Lastly, as it can be expected that the presence of corporations and the general distribution of stakeholders will vary across policy areas, the subsequent statistical models also control for the different policy areas. However, to ensure that the impact of text technicality and complexity is robust across policy areas, additional full models that do not control for the policy area are included in Appendix G.

Results

In this section, we present the results from our statistical analyses. We first provide a summary of our data before moving to the estimated (logistic) models that test our hypotheses. 36.3 percent (N = 13,463) of the sampled 35,674 articles mentioned stakeholders that gained access to policymakers. Corporations dominate the list of appearances in the articles and represent on average 42.4 percent of the stakeholder mentions per article, followed by public institutions (20.2 percent) and NGOs (18.8 percent). It is important to note here that although this study relied on insider data to measure appearances in the news, scholarly work carried out in similar contexts that has employed different sampling strategies illustrates a comparable image. One where corporations form the category that gains most access to the news compared to other types of organized interests (Aizenberg & Hanegraaff, Citation2020b; Danielian & Page, Citation1994). The appearance of stakeholder varies between policy areas. See Appendix E for an overview and discussion of the differences.

Turning to an examination of our hypothesis, we estimated five different models. Since the dependent variable (i.e., share of corporations amongst total mentioned stakeholders per newspaper article) is a proportion that ranges between 0 and 1, the analysis was run with a beta regression, using the betareg package in RStudio.Footnote8 To observe the two hypotheses independently, we estimated two models each for text technicality and text readability. The first models (i.e., models 1 and 3) only test stakeholder-level control variables, whilst the second models additionally control for the newspaper (Guardian vs. The Times) and policy field (i.e., models 2 and 4). The fifth model includes all variables under investigation ().

Table 1. Regression results.

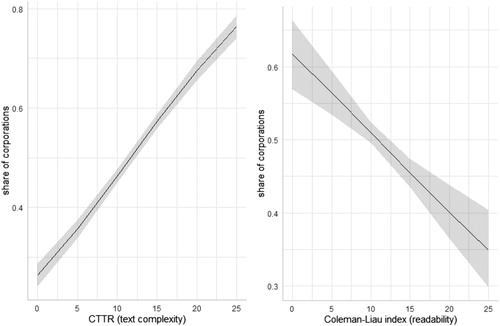

The significance values of our results should be interpreted with a strong sense of caution, as a large n sample such as ours will very likely produce significant results (Lin et al., Citation2013). We will instead focus on discussing the effect size and standard error terms of the various variables and visualize them via marginal effect plots. The results table shows much support for H1, as text technicality is always positively associated with corporation presence in the news. This indicates that corporations are indeed more likely to appear in coverage that is more technical in nature compared to other organized interests: departing from the distribution of our text technicality variable, the predicted share of corporations in the news articles rises from 44 percent in the first quartile of the CTTR distribution (=8.7) to 51.5 percent in the third quartile (=11.96). This finding is in line with our expectations that corporations are in all likelihood more inclined to be involved in coverage of a technical nature to signal expertise to specific constituencies (see Beyers, Citation2004), and that journalists are more perceptive to corporations’ media strategies than other types of organized interests when consulting them on such matters (Albæk, Citation2011). The standard errors are very small and the 95 percent confidence interval never crosses 0. The impact of text technicality on the projected share of corporations in a news article is strong, as the marginal effect plot in shows.

Figure 1. Marginal effects: Predictions of share of corporations in articles based on changes in complexity and accessibility of the text (based on model 5).

The second plot in . displays a different trend than expected: the more readable (i.e., accessible) the text is, the higher the predicted share of corporations in the article. As with text technicality, the findings are robust across all models that include text readability (2,4,5). The strength of this effect is much weaker than the effect of text technicality (see Appendix Figure E1). The share of corporations mentioned in each newspaper article drops from 51 percent at the first quartile of the Coleman-Liau index distribution (=10.6) to 46 percent at the thirst quartile (=12.4). This finding is not in line with our expectations. A possible explanation could be that corporations are not necessarily afraid to take a risk and when seeking to maximize influence, they want to ensure that their specific constituency understands the coverage. Another explanation for this finding is that journalists nowadays use readability scores for articles in order to make it accessible to the reader. To ensure that the observed effects are generally present across topics (independent of the policy area), we ran additional models that do not control for the policy area (Appendix G). The results are very similar to the findings presented above.

Discussion

Research on the involvement of corporations in political news coverage states that, on the one hand, business interests, and corporations more specifically, are not too keen to be seen in publicly visible arenas such as the media. They are thought to avoid such arenas in order to avoid the scope of conflict from expanding (see e.g., Bernhagen & Trani, Citation2012; Dür et al., Citation2015), and to reduce the risk of receiving scrutiny from the public regarding their legitimacy (Hart, Citation2004; Hula, Citation1999; Mitchell et al., Citation1997). On the other hand, another strand of literature illustrates that corporations are amongst the most dominant players when it comes to gaining access to the media arena (Aizenberg & Hanegraaff, Citation2020b; Danielian & Page, Citation1994; Van der Graaf et al., Citation2016). While corporations are thus thought to prefer insider strategies, they dominate political news compared to other types of organized interests.

This paper asked how these findings should be interpreted. It argues that corporations use multiple strategies, such as interacting directly with policy-makers and employing media strategies, in order to maximize their influence (Baumgartner & Leech, Citation1998; Beyers, Citation2004; Kriesi et al., Citation2007). When engaging in media strategies they are thought to do so with a specific goal and target group, in order to signal expertise to specific constituencies (see Beyers, Citation2004). We also expected journalists to be more inclined to consult business interests compared to other groups when covering issues with a technical nature as this is part of businesses’ core activities and therefore they tend to have more knowledge on such matters (Albæk, Citation2011; Bouwen, Citation2002; De Bruycker, Citation2016). As a consequence, we expected corporations to be involved in coverage that is both technical and not necessarily accessible to the public at large.

The paper found that corporations are indeed more likely to be involved in political news coverage with a technical nature compared to other types of organized interests. This is an important finding as it highlights for the first time that the nature of news coverage in which corporations appear can in some contexts be different from news coverage in which other types of organized interests appear. The results also illustrate that this coverage is not necessarily less accessible; on the contrary, corporations are more likely to appear in news that is more accessible to the general reader.

These findings are important as they tell us more about the nature of how key players of the political process are involved in political news. In doing so, this paper adds to the strands of literature on how organized interests employ public strategies (see e.g., Beyers, Citation2004; Kollman, Citation1998; Trevor Thrall, Citation2006), and it provides more context to the branch of research on appearances of organized interests in the news media (see e.g., Binderkrantz et al., Citation2017; Danielian & Page, Citation1994). What is more, it implies that the coverage in which they appear is more accessible than initially thought, which is a positive finding for the functioning of our democracies. That is, newspapers are an important source for citizens to learn about politics and thus form a well-informed opinion (Danielian & Page, Citation1994). For this very reason, coverage on key players in politics should be accessible.

Importantly, while this research aimed to study technicality and accessibility of policy news in which corporations appear while controlling for policy area, some interesting differences between policy areas were observed as well. While zooming in on these differences and the possible related mechanisms falls outside of the scope of this paper, this would be an interesting avenue for future research. It is also important to note that this study did not examine the nature of appearances of corporations on social media channels. Although a majority of citizens source their news from either print (decreasingly) and online (increasingly) news media, a considerable share also consumes news via social media (Geiger, Citation2019). Due to the different structure and communicational dynamics (e.g., short messages instead of full articles, direct interaction between originator and audience, different audiences), we could expect varying behavior of corporations on these platforms. Therefore, future research could provide a more nuanced image of how corporations (and other stakeholder groups) appear on online news platforms and social media channels.

Although this study provided some important findings, there are two key limitations that are important to highlight. First, this paper only sheds light on the context in which corporations are involved in news coverage, and does not necessarily grasp the motivations from corporations to become involved in news coverage. We tried to incorporate agency of the corporations by including organizations that are already active on a policy issue, and by tracing them in news coverage on these same issues. Still, conducting a survey experiment or in-depth interviews to grasp the motivations behind corporations incorporating the media in their strategies would be interesting avenues for future research. Such endeavors could also tap into internal mechanisms within corporations by looking into which departments and professionals take the lead when pursuing outside strategies. Are public affairs managers in charge or rather communication specialists or a combination of these?

Second, it needs to be acknowledged that this article makes an argument about a general mechanism that concerns the media strategies and appearance of corporations. The authors expect that there might be important differences between corporations concerning how media strategies are approached. It could be the case for example that some companies tend to pursue an overall low key strategy due to the core business that they operate in and the associated criticism that is targeted at the concerning sector. That is, companies operating in the chemical industry are probably more likely to face public scrutiny compared to businesses that produce electric bicycles. Another factor that might be important here is the issue that is at stake. The strategy of choice is expected to be influenced by the issue as companies might be more inclined to communicate openly about corporate social responsibility activities they are engaging in compared to when it is discovered that the corporation engaged in tax avoidance. When an issue thus might hurt their image, corporations are expected to be more inclined to employ a strategy that avoids the public spotlight. Further research is needed to explore these differences.

To conclude, with this paper we aimed to provide a better understanding of the way in which corporations are involved in political news. As they are dominant players in contemporary democracies, we hope that scholars are keen to further explore motivations behind the lobbying behavior of these key political actors through the media and beyond.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (7.3 MB)Acknowledgements

For useful feedback, we thank the anonymous reviewers, Dimiter Toshkov and all the participants of the PhD Club at the Institute of Public Administration at Leiden University. For research assistance and coding, we thank Max Scheijen and Mart Zuur. We are particularly grateful to Marcel Hanegraaff, Joost Berkhout, Caelesta Braun and Bert Fraussen for outstanding comments and guidance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ellis Aizenberg

Ellis Aizenberg is a PhD Candidate in Political Science at the University of Amsterdam, Netherlands. [[email protected]].

Moritz Müller

Moritz Müller is a PhD Candidate at the Institute of Public Administration at Leiden University, Netherlands. [[email protected]].

Notes

1 See Appendix H for more information on the newspaper selection.

2 See Aizenberg and Hanegraaff (Citation2020b) for another application of this approach and to read more about the approach’s validity.

3 All search strings can be found in Appendix B.

4 See Appendix C for a discussion of the results of this endeavor.

5 See Aizenberg (Citation2020) for a discussion of this method.

6 The dataset covers the same timespan as our news article dataset.

7 See Appendix D for the specifics of this approach.

8 See Appendix I for further information on the model.

9 See https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/irr/irr.pdf for more information on the package and the measure.

References

- Aizenberg, E. (2020). Text as Data in Interest Group Research. In: Harris P., Bitonti A., Fleisher C., Skorkjær Binderkrantz A. (eds) The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Interest Groups, Lobbying and Public Affairs. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

- Aizenberg, E., & Hanegraaff, M. (2020a). Is politics under increasing corporate sway? A longitudinal study on the drivers of corporate access. West European Politics, 43(1), 181–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1603849

- Aizenberg, E., & Hanegraaff, M. (2020b). Time is of the essence: A longitudinal study on business presence in political news in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(2), 281–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161219882814

- Albæk, E. (2011). The interaction between experts and journalists in news journalism. Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism, 12(3), 335–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884910392851

- Baumgartner, F. R., Jones, B. D., & Wilkerson, J. (2011). Comparative studies of policy dynamics. Comparative Political Studies, 44(8), 947–972. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414011405160

- Baumgartner, F. R., & Leech, B. L. (1998). Basic interests: The importance of groups in politics and in political science. Princeton University Press.

- Baumgartner, F. R., & Leech, B. L. (2001). Interest niches and policy bandwagons: Patterns of interest group involvement in national politics. The Journal of Politics, 63(4), 1191–1213. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-3816.00106

- Benoit, K., Watanabe, K., Wang, H., Nulty, P., Obeng, A., Müller, S., & Matsuo, A. (2018). Quanteda: An R package for the quantitative analysis of textual data. Journal of Open Source Software, 3(30), 774. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00774

- Berkhout, J. (2013). Why interest organizations do what they do: Assessing the explanatory potential of ‘exchange’ approaches. Interest Groups & Advocacy, 2(2), 227–250. https://doi.org/10.1057/iga.2013.6

- Berkhout, J., Beyers, J., Braun, C., Hanegraaff, M., & Lowery, D. (2018). Making inference across mobilisation and influence research: Comparing top-down and bottom-up mapping of interest systems. Political Studies, 66(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321717702400

- Bernhagen, P., & Mitchell, N. J. (2009). The determinants of direct corporate lobbying in the European Union. European Union Politics, 10(2), 155–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116509103366

- Bernhagen, P., & Trani, B. (2012). Interest group mobilization and lobbying patterns in Britain: A newspaper analysis. Interest Groups & Advocacy, 1(1), 48–66. https://doi.org/10.1057/iga.2012.2

- Beyers, J. (2004). Voice and access: Political practices of European interest associations. European Union Politics, 5(2), 211–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116504042442

- Binderkrantz, A. S. (2012). Interest groups in the media: Bias and diversity over time: Interest groups in the media. European Journal of Political Research, 51(1), 117–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.01997.x

- Binderkrantz, A. S., Bonafont, L. C., & Halpin, D. R. (2017). Diversity in the news? A study of interest groups in the media in the UK, Spain and Denmark. British Journal of Political Science, 47(2), 313–328. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123415000599

- Binderkrantz, A. S., Christiansen, P. M., & Pedersen, H. H. (2015). Interest group access to the bureaucracy, parliament, and the media: Interest group access. Governance, 28(1), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12089

- Bouwen, P. (2002). Corporate lobbying in the European Union: The logic of access. Journal of European Public Policy, 9(3), 365–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760210138796

- Bouwen, P. (2004). Exchanging access goods for access: A comparative study of business lobbying in the European Union institutions. European Journal of Political Research, 43(3), 337–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2004.00157.x

- Carpini, M. X. D., & Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans know about politics and why it matters. Yale University Press.

- Carroll, J. (1964). Language and thought. Prentice-Hall.

- Chalmers, A. W. (2011). Interests, influence and information: Comparing the influence of interest groups in the European Union. Journal of European Integration, 33(4), 471–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2011.579751

- Chalmers, A. W. (2013). With a lot of help from their friends: Explaining the social logic of informational lobbying in the European Union. European Union Politics, 14(4), 475–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116513482528

- Clark, D. M., Canvin, L., Green, J., Layard, R., Pilling, S., & Janecka, M. (2018). Transparency about the outcomes of mental health services (IAPT approach): An analysis of public data. The Lancet, 391(10121), 679–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32133-5

- Coen, D. (1997). The evolution of the large firm as a political actor in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 4(1), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/135017697344253

- Coleman, M., & Liau, T. L. (1975). A computer readability formula designed for machine scoring. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(2), 283–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076540.

- Cribari-Neto, F., & Zeileis, A. (2010). Beta regression in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 34(2), 1–24. doi:10.18637/jss.v034.i02.

- Danielian, L. H., & Page, B. I. (1994). The heavenly chorus: Interest group voices on TV news. American Journal of Political Science, 38(4), 1056. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111732

- De Bruycker, I. (2016). Pressure and expertise: Explaining the information supply of interest groups in EU legislative lobbying: Pressure and expertise. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(3), 599–616. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12298

- De Bruycker, I., & Beyers, J. (2015). Balanced or biased? Interest groups and legislative lobbying in the European news media. Political Communication, 32(3), 453–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2014.958259

- Dür, A., Bernhagen, P., & Marshall, D. (2015). Interest group success in the European Union: When (and why) does business lose? Comparative Political Studies, 48(8), 951–983. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414014565890

- Galtung, J., & Ruge, M. H. (1965). The structure of foreign news: The presentation of the Congo, Cuba and Cyprus crises in four Norwegian newspapers. Journal of Peace Research, 2(1), 64–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/002234336500200104

- Gamson, W. A., & Wolfsfeld, G. (1993). Movements and media as interacting systems. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 528(1), 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716293528001009

- Geiger, A. W. (2019). Online news in the U.S.: Key facts | Pew Research Center. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/09/11/key-findings-about-the-online-news-landscape-in-america/.

- Grant, W. (1982). The government relations function in large firms based in the United Kingdom: A preliminary study. British Journal of Political Science, 12(4), 513–516. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400003082

- Gray, V., & Lowery, D. (2001). The institutionalization of state communities of organized interests. Political Research Quarterly, 54(2), 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591290105400202

- Gray, V., Lowery, D., & Wolak, J. (2004). Demographic opportunities, collective action, competitive exclusion, and the crowded room: Lobbying forms among institutions. State Politics & Policy Quarterly, 4(1), 18–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/153244000400400102

- Hart, D. M. (2004). “Business” is not an interest group: On the study of companies in American national politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 7(1), 47–69. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.7.090803.161829

- Heinz, J. P., Laumann, E. O., Nelson, R. L., & Salisbury, R. H. (1993). The hollow core: Private interests in national policy making. Harvard University Press.

- Hula, K. W. (1999). Lobbying together: Interest group coalitions in legislative politics. Georgetown University Press.

- Kleinberg, M. S., & Lau, R. R. (2019). The importance of political knowledge for effective citizenship: Differences between the broadcast and internet generations. Public Opinion Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfz025.

- Kollman, K. (1998). Outside lobbying: Public opinion and interest group strategies. Princeton University Press.

- Kriesi, H., Tresch, A., & Jochum, M. (2007). Going public in the European Union: Action repertoires of Western European collective political actors. Comparative Political Studies, 40(1), 48–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414005285753

- Lin, M., Lucas, H. C., & Shmueli, G. (2013). Too big to fail: Large samples and the p-value problem. Information Systems Research, 24(4), 906–917. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2013.0480

- Lindblom, C. E. (1977). Politics and markets. Basic Books.

- Lowery, D., Baumgartner, F. R., Berkhout, J., Berry, J. M., Halpin, D., Hojnacki, M., … Schlozman, K. L. (2015). Images of an unbiased interest system. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(8), 1212–1231. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1049197

- Madeira, M. A. (2016). New trade, new politics: Intra-industry trade and domestic political coalitions. Review of International Political Economy, 23(4), 677–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2016.1218354

- Martin, C. J., & Swank, D. (2004). Does the organization of capital matter? Employers and active labor market policy at the national and firm levels. American Political Science Review, 98(4), 593–611. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055404041371

- Mitchell, N. J., Hansen, W. L., & Jepsen, E. M. (1997). The determinants of domestic and foreign corporate political activity. The Journal of Politics, 59(4), 1096–1113. https://doi.org/10.2307/2998594

- Olson, M. (1965). The theory of collective action: Public goods and the theory of groups. Harvard University Press.

- Owens, R. J., Wedeking, J., & Wohlfarth, P. C. (2013). How the supreme court alters opinion language to evade congressional review. Journal of Law and Courts, 1(1), 35–59. https://doi.org/10.1086/668482

- Patterson, T. E. (2000). The United States: News in a free-market society. In R. Gunther & A. Mughan (Eds.), Democracy and the media (pp. 241–265). Cambridge University Press.

- Plag, I., Homann, J., & Kunter, G. (2017). Homophony and morphology: The acoustics of word-final S in English. Journal of Linguistics, 53(1). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022226715000183.

- Salisbury, R. H. (1984). Interest representation: The dominance of institutions. American Political Science Review, 78(01), 64–76. https://doi.org/10.2307/1961249

- Schattschneider, E. E. (1960). The semisovereign people: A realist’s view of democracy in America. The Dryden Press.

- Schlozman, K. L. (1984). What accent the heavenly chorus? Political equality and the American pressure system. The Journal of Politics, 46(4), 1006–1032. https://doi.org/10.2307/2131240

- Shannon, C. E. (1948). A mathematical theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal, 27(3), 379–423. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x

- Trevor Thrall, A. (2006). The myth of the outside strategy: Mass media news coverage of interest groups. Political Communication, 23(4), 407–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600600976989

- Van Atteveldt, W. H. (2008). Semantic network analysis: Techniques for extracting, representing, and querying media content.

- Van der Graaf, A., Otjes, S., & Rasmussen, A. (2016). Weapon of the weak? The social media landscape of interest groups. European Journal of Communication, 31(2), 120–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323115612210

- Wilson, J. Q. (1973). Political organizations. Basic Books.