ABSTRACT

Is the European Union a technocracy? Observers and practitioners of EU politics have debated this deceptively simple question for decades, without arriving at a clear answer. To a large extent, this is due to the elusive nature of technocracy itself, a phenomenon that is hard to define with precision, and even harder to measure empirically. To tackle this problem, the article presents a novel approach to technocracy in the EU based on the study of bargaining settings, in which political and technical actors interact horizontally and simultaneously—as opposed to sequentially—thus allowing for a better appraisal of the power of experts. Using data gathered by the ‘EMU Choices’ project, we apply this alternative framework to the analysis of negotiations on the reform of the Economic and Monetary Union over the period 2010–15, focusing on the role of two institutional actors: the European Central Bank and the European Commission. While we find some evidence for technocracy in EMU negotiations, this has been mostly at the hands of the hybrid Commission rather than the quintessentially technical ECB. This suggests both caution in dismissing the EU as hopelessly technocratic, and the need for further research on the nature of the Commission.

Introduction

Is the European Union (EU) a technocracy? This longstanding question about the process of European integration (e.g., Radaelli, Citation1999; Shapiro, Citation2005; Wallace & Smith, Citation1995) has become particularly pressing in the past decade or so, as the euro crisis and the increasing politicization of European affairs have made the (possibly disproportionate) place of unelected experts and bureaucrats in the EU’s political system more salient than ever. Yet, we do not now seem to be any closer to a clear answer to the matter than at any point during the past. For some, the EU can be described essentially in technocratic terms. The European Union, Matthijs and Blyth (Citation2017) argue, ‘is a technocracy, run by bureaucrats who see rule-breaking as a challenge to their own authority. In particular, the “euro zone” – the countries of Europe that share a single currency – is subjected to technocratic rule.’ In a similar vein, Mounk (Citation2018) presents the EU as a prime example of ‘undemocratic liberalism’, a political regime that puts key aspects of decision-making in the hands of career officials and specialized agencies disconnected from national electorates. Other observers counter that the technocratic nature of the EU is just another myth surrounding European affairs (e.g., Balfour & David-Wilp, Citation2016). The role performed by experts within the Union, they continue, is not too different from what we would expect in any well-functioning modern liberal democracy, namely very important yet confined within clear boundaries set by representative politics. In sum, the EU may have many problems, but being a technocracy is not one of them (Schneider, Citation2018).

That diametrically opposite diagnoses coexist on such a crucial issue for the political legitimacy of the EU is due to a number of reasons, including the fact that observers on both sides often generalise—not least for rhetorical effect—based on the observation of different parts, aspects, policies, or developmental stages of the Union. To a significant extent, however, the disagreement runs much deeper than that, and relates to the elusiveness of technocracy as a term, both conceptually and empirically (Radaelli, Citation1999; Sánchez-Cuenca, Citation2017; Tortola, Citation2020a). For instance, where do we draw the exact line between expert advice for, and undue influence over, political decisions? At what point does the autonomy granted to technicians to implement certain policies becomes too much? And how do we detect technocratic overstepping with precision in the context of wide political mandates? Questions of this sort are often very difficult, if not impossible, to answer. As a result, the concept of technocracy remains largely contested, and its occurrence in the eye of the beholder.

This article aims to move the debate on EU technocracy beyond this conceptual impasse by proposing a novel approach to the phenomenon, which examines the power of experts by looking at their interactions with political actors in bargaining settings, as opposed to the sequential relationship that normally makes up the public policy process. To do so we leverage evidence from the recent reform of the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), a process that has developed over several years (and is, partly, still ongoing), involving a dense set of negotiations between political and technical actors. The article therefore contributes to the literature on EU technocracy from a conceptual, theoretical and empirical standpoint.

The rest of the article proceeds as follows: the next section elaborates on the theoretical setup by further discussing the notion of technocracy, its conceptual and empirical limits, and the solution presented by the analysis of bargaining settings. In the third section we then introduce the case of EMU reform negotiations, and formulate four hypotheses on the occurrence of and factors leading to technocracy in that specific context. The fourth section describes our data and research design, and presents the empirical analysis. The fifth and final section concludes by discussing our findings and their implications, and sketching avenues for further research.

Technocracy and bargaining

Technocracy is a concept as complex and multifaceted as it is longstanding in political and academic debates. Here we define technocracy as a state of undue dominance by unelected experts over representative politicians in the making of public policy. Our definition largely overlaps with the idea of ‘technocracy as regime’ in Tortola’s (Citation2020a) recent dissection of the term, which indicates a degeneration of the role of experts in the political system that turns them into the de facto primary decision-makers, albeit within the formal framework of representative democracy. This notion of technocracy by no means exhausts the concept (Gunnell, Citation1982; Radaelli, Citation1999), but it is certainly the prevailing one (at least implicitly) in debates over the technocratic nature of the European Union. Below we elaborate further on this definition.

All advanced political systems, including the EU, find it helpful to remove some parts of the policy-making process from the direct control of the representative political level, and place it in the hands of experts and technicians.Footnote1 This may happen for a number of reasons, such as the need to make well-informed and effective choices in complex policy areas, or the desire to insulate certain decisions from the short-termist temptations of elected politicians (Pettit, Citation2004; Tarlea, Citation2018; Tarlea & Freyberg-Inan, Citation2018; Vibert, Citation2007). Whatever the rationale for delegating, in a well-functioning democratic system the role of experts must always remain in a midway position between zero and total autonomy vis-à-vis the political sphere. On the one hand, experts must be granted a certain degree of freedom to be able to act on the basis of science and knowledge rather than partisan-political logics. On the other hand, their actions must be confined within broader societal objectives, which by their intrinsic normative nature can only be set politically (Tortola, Citation2020a). To phrase it like Sartori (Citation1987, p. 423), ‘[a] government of experts is admissible in regard to means, not ends’.

It is the collapse of the latter boundary between politics and expertise that gives rise to technocracy as defined here. As the technician escapes the confines set by politics, s/he immediately turns into a technocrat controlling, whether or not deliberately, not only the means of public policy, but also its goals. Technocracy so defined is, therefore, an inherently undemocratic state of affairs, which leaves the formal features of democracy—and above all the subordination of technicians to politics—unaltered, but de facto shifts ultimate control over the definition of the ‘good society’ away from the demos (via its elected representatives) and places it in the hands of a small group of experts participating in policy-making in various capacities and at various stages.

How does this stealthy usurpation of political power on the part of technicians take place? Technocracy scholar Jean Meynaud (Citation1969) identifies four modes of ‘dispossession’: first, and most simply, technicians may just disobey or resist political instructions. Second, they may gain control of policy areas in which they are given overly ample or vague mandates, which leave them ‘practically master[s] of the problem’ (Meynaud, Citation1969, p. 80). Third, when advising politicians and majoritarian institutions, experts can acquire sway by framing and setting the terms of policy problems consistently with their preferred outcomes. Finally, experts’ power can come from coordinating and mediating among other governmental departments, particularly when inter-agency compromises are hard-won and unlikely to be questioned by politicians.

What these four avenues to technocracy have in common is that they all refer to a sequential relationship between experts and politicians, in which the former intervene in the policy-making process either before a political decision is made, as consultants and advisors, or after it, as policy implementers. This is not too surprising, given that this sequential relationship is the most common situation in democratic political systems. The problem this sequential configuration poses, however, is that it often makes it very difficult to identify precisely the point at which politics ends and expertise begins (or vice versa), and consequently assess whether this line has actually been trespassed by technicians—so giving rise to technocracy.Footnote2 This is, we contend, a key (if not the main) reason behind the elusive and contested nature of technocracy as a political phenomenon in virtually all advanced democratic systems (Laird, Citation1990; Winner, Citation1978).

An important exception to the conceptual and empirical limits just described is constituted by situations in which political and technical actors do not work in sequence, but instead come together in order to make a public policy decision. To the extent that non-trivial differences exist among the preferences of politicians and experts, this generates a bargaining setting that should make it easier to gauge the latter’s power—and therefore technocracy—by measuring the bargaining outcome against the participants’ initial position: the closer the final decision to the technicians’ preferences (and the farther from politicians’ positions), the stronger the case for the presence of technocracy.

By allowing a clearer and more precise assessment of expert influence in policy-making, looking at the horizontal and simultaneous setup of bargaining situations presents two further analytical advantages: first, it replaces the common, and very simplistic dichotomous interpretation of technocracy—whereby the technocratic nature of a political (sub)system is either accepted or rejected in toto—with a more fine-grained view of technocracy as something that can occur to different degrees. As we noted in the introduction, the existing debate on technocracy is often forced into improbable generalizations by the vagueness of the term. By reducing the latter, we should also be able to arrive at a more realistic measurement of technocracy. Second, this approach puts us in a better position to move beyond a descriptive analysis of technocracy, by examining the factors and contexts that correlate with this phenomenon. In sum, the method proposed here should help us improve on the existing debate on technocracy from a conceptual, theoretical, and empirical standpoint. The rest of the article applies the bargaining approach to technocracy to the recent case of negotiations on the reform of the Economic and Monetary Union.

Studying technocracy in EMU negotiations

The euro crisis has spurred an intense period of policy and reform activity within the Eurozone, and the EU as a whole, over the past decade or so. Faced with a wide array of new political and economic challenges, the EU and Eurozone have had to make a number of important and unprecedented policy decisions (such as on bailing out Greece and other ailing economies), take initiatives for the update of existing institutions and procedures (e.g., those of the Stability and Growth Pact), and finally create new ones, such as the Fiscal Compact, the Banking Union, and the European Stability Mechanism.Footnote3 The many measures taken to reform the Economic and Monetary Union in recent years have followed different timelines and been embedded in a number of procedural frameworks (ranging from the community method to traditional intergovernmental diplomacy), but they all have involved negotiations among a variety of actors, both political and technical. Member state governments make up most of the former category, while in the latter we find primarily two supranational EU institutions:

European Central Bank (ECB). One of the foremost institutions of the Eurozone, the ECB is formally set up as an expert/technical actor par excellence: it is an unelected, non-majoritarian body granted a high degree of independence from its political principals (the member states), and tasked with conducting the Eurozone’s monetary policy guided by macroeconomic reasoning and within a mandate of price stability. In recent years, the ECB has played an important role in steering the Eurozone through its crisis and its economic aftermath, among other things by introducing a number of unconventional measures, which have led many observers to speak of a ‘politicization’ of the Bank (on this debate see e.g., Högenauer & Howarth, Citation2016; Jones & Matthijs, Citation2019; Scicluna, Citation2014; Tortola, Citation2020b). The excessive policy-making autonomy on the part of the ECB, to which these authors point by using the term politicization, essentially overlaps with the notion of technocracy as defined in this article.

European Commission (EC). The EC was originally established as a largely technical body put in charge of the guardianship and implementation of the European treaties. From its inception, however, the Commission was also conferred a number of more political competences and traits, among which its monopoly over supranational legislative initiatives and its generalist, rather than specialist, policy portfolio. As Coombes (Citation1970, p. 83) put it in his classic study, this variety of roles and competences made the Commission operate under ‘different kinds of attitude’—some technical, some political—right from the start. The hybrid nature of the EC has persisted, and arguably even become more marked, over time. The introduction of the Spitzenkandidaten procedure for the appointment of the EC president, and of public rituals such as the State of the European Union address, for instance, have enhanced the political profile of the Commission (Kassim & Laffan, Citation2019; Peterson, Citation2017; Wille, Citation2013). On the other hand, the EC and its members still retain a wide range of more distinctly technical roles and competences, and have seen some of these significantly strengthened in recent years—leading some observers to dub the Commission ‘the most powerful “independent agency” in the world’ (Mounk, Citation2018, p. 102). This is the case, most notably, of macroeconomic surveillance, where the EC holds a number of key functions (for example through its role in the European Semester). The persistence of a strong technical component in the mission of the EC motivates its inclusion in this analysis.

Here we want to focus on the role and influence of these two institutions in the negotiations for the reform of the EMU in order to assess the presence, degree, and possibly correlates of technocracy in this sphere. While it does not exhaust the recent activities of the EU (or even the Eurozone), the EMU reform case is nonetheless a very good testing ground for technocracy for at least three reasons: first, as already mentioned, because of the high incidence of technical-political negotiations in this area, and the plenitude of information and data that can be obtained on them. Second, because of the importance of the recent EMU reforms as a juncture in the political and institutional development of the Eurozone and the EU more generally, which makes any question about the ways in which these decisions came about, and about their legitimacy, especially salient. The third reason is that the Eurozone is time and again depicted as the single most technocratic arena in the EU, as noted at the beginning of this article. This, in a sense, makes the EMU a ‘crucial’ case for studying technocracy in the EU: one in which we would expect to see experts be particularly influential over policy if the Union is indeed a technocratic system, and conversely one which should make us more sceptical vis-à-vis the notion of a technocratic EU, should we not observe too much expert power in this specific set of negotiations (Eckstein, Citation1975; Gerring, Citation2007). In sum, looking at the power of experts in the process of EMU reform can provide us with a particularly important piece in the broader puzzle of technocracy in the European Union.

We want to test, in particular, four distinct hypotheses on the presence of and factors related to the power of the ECB and EC (hereafter ‘technical actors’) in EMU reform negotiations:

H1: The technical actors systematically exert influence over the negotiations under examination.

This first hypothesis is aimed at testing for the presence and extent of technocracy tout court in EMU negotiations. In a technocratic situation we would expect the two technical actors to systematically prevail in negotiations, or in any case significantly pull the final outcome towards their initial bargaining position. Conversely, in a non-technocratic situation we would either see the technical actors systematically on the losing side of negotiations, or detect no particular influence pattern if technicians may win or lose with an equal probability.

H2: The technical actors will exert greater influence in negotiating settings that place them in a more advantageous position.

As mentioned above, the EMU negotiations under scrutiny here have taken place in a variety of formal settings. Regardless of the technical actors’ overall bargaining power, we would expect them to be more influential whenever the formal context and rules of the negotiation are more advantageous to them. Two aspects seem particularly important in this respect: first, how close the interaction between technical and political actors is—we would expect technicians to be more influential the more direct contact they have with the political actors during the negotiating process (as opposed to negotiating from a distance, so to speak). The second aspect is the bargaining and decision-making rules: the more favourable they are to the technical actors, the greater should be their influence.

H3: The technical actors will exert greater influence the more complex the issue being negotiated.

The various issues negotiated as part of the EMU reform present different degrees of complexity, defined here as the amount of background knowledge and reasoning needed to formulate a well-informed opinion on a certain matter. We expect the technical actors to be better equipped, on average, to know and understand the ins and outs and the implications of the issues under negotiation. This should give them an informational and argumentative advantage that grows together with the complexity of the issue under examination, and which should accordingly translate into greater bargaining power.

H4: The technical actors will exert less influence the more politically salient the issue under negotiation.

Political salience—the awareness of a certain issue on the part of voters, and the importance they attach to it—can be expected to diminish the power of experts over the negotiation. As issues become more important in the eyes of the public, political actors, whose fortunes depend more directly on voters’ support, will have an incentive to harden their bargaining stance. Other things being equal, this should in turn increase their bargaining power vis-à-vis unelected technicians.

Data and research design

To test the four hypotheses just described, we rely primarily on data on EMU reform generated by the ‘EMU Choices’ research project (www.emuchoices.eu), which collected and coded information on the preferences of member states and supranational actors in negotiations on a total of 47 distinct policy issues, spanning the period 2010–15 (Tarlea et al., Citation2019; Wasserfallen et al., Citation2019). Here we will limit the analysis to the 39 issues for which a negotiated outcome was reached by the end of 2015. A description of the issues under examination is presented in online appendix A.

The contestation space for each negotiated issue was coded on a 0–100 scale, with the two extreme values indicating the highest level of disagreement measured among negotiating actors. This coding scale was designed in accordance with established practices, as introduced in Bueno de Mesquita and Stokman (Citation1994), and further developed by the DEU I and II datasets (Thomson et al., Citation2012). For each of our issues, the value 0 indicates positions in favor of measures that would eventually lead to less European integration, whereas 100 indicates positions in favor of policy changes leading to more European integration (see also Lundgren et al., Citation2019a; Tarlea et al., Citation2019; Tarlea & Bailer, Citation2020). For more detailed information on the coding procedure, its sources, and the reliability of the data we direct the reader to online appendix B, as well as Wasserfallen et al. (Citation2019).

Two examples will briefly illustrate the coding scheme: in 2012 EU members debated whether to expand the so-called fiscal compact to include some form of tax coordination (issue FC8 in online appendix A). Some governments were open to a number of options in this direction, such as a common consolidated corporate tax base (CCCTB), general tax harmonization, or the introduction of a financial transaction tax (FTT). The negotiating position of these member states was coded 100 in the dataset. A majority of member states, however, held the opposite position (coded 0) of rejecting any supranational form of tax coordination. As a result, the fiscal compact remained focused on fiscal stability and budgetary discipline, and the negotiation outcome was accordingly coded 0.

The second illustrative case refers to the debates on the first Greek bailout in early 2010 (issue G1 in online appendix A). As the EU and Eurozone searched for solutions to the Greek debt crisis, some member states were prepared to support Greece financially (coded 100), while others initially resisted such proposals (coded 0). On March 15, 2010 the Eurogroup agreed to make financial support available upon request (Greece officially requested it on May 2, 2010). The decision to grant a bailout funded by all Eurozone countries was coded 100. As the opinion started to gravitate towards some form of the EU/Eurozone support, the debate turned towards the question of the bailout’s precise structure (issue G2 in online appendix A). Some governments, together with the EC, initially argued in favor of basing the programme on some systemic crisis-management framework (such as a European Monetary Fund) (coded 100), while others leaned towards an ad hoc combination of existing instruments (e.g., bilateral loans), which would require only limited legal changes and institution-building (coded 0). The Greek Loan Facility that was eventually established consisted of bilateral loans from euro area countries and the IMF, coordinated by the Troika but not based on any systematic support framework (outcome coded 0).

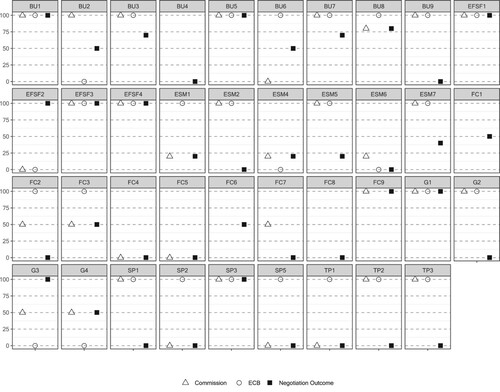

provides a visual overview of our data by showing the negotiating positions of the European Central Bank and the European Commission on the 39 issues under examination, along with negotiated outcomes.

Empirical model and results

To test for the presence, extent and correlates of the influence exerted by the ECB and the EC over EMU negotiations, we begin by establishing our dependent variable as the bargaining success of each member state participating in the negotiations. Following the approach of Lundgren et al. (Citation2019b), and consistently with common practice in political economy and EU studies literature (e.g., Arregui & Thomson, Citation2009; Bailer, Citation2004; Lundgren et al., Citation2019b), we operationalize bargaining success by subtracting from 100 the distance between the initial position of a country on a given issue and the negotiated outcome. Thus, at the two extremes, a member state whose initial position on an issue corresponds to the negotiated outcome—and which therefore has achieved full bargaining success—is assigned a value of 100, while a member state for which the difference between initial position and outcome is 100, indicating a total defeat, is given a score of 0. Our total number of observations is 575.

For the purposes of testing our first hypothesis, we model our main independent variables as two dummies indicating whether, on each given issue, the initial position of the ECB (or the EC) coincides with that of the member state under examination (in which case there is a ‘coalition’ between the state and the technical body: value 1) or not (value 0). The intuition behind this approach is that if we observe that being aligned with the preferences of a technical body systematically increases a member state’s chances to prevail in a negotiation, we would have a strong indication that the technical body in question exerts autonomous influence over the negotiation’s outcome. Conversely, should we find that the coalition between a state and a technical body either decreases or has no effect on the state’s chances of success, we would conclude against the technocratic hypothesis.

To test H2 through H4, we introduce interaction terms between the coalition dummies and three additional variables corresponding to the three hypotheses, and operationalized as follows:

Bargaining setting: For simplicity, in our dataset we identify only two types of bargaining setting for each of the technical actors under examination, separating the one expected to place experts in the most advantageous position from the rest. For the European Central Bank, we expect the most favourable setting to be that of the Eurogroup meetings, based not only on the greater consistency of this setting to the ECB’s competence reach—both subject- and membership-wise—but also, and more concretely, on the fact that the ECB president has the right to participate in Eurogroup meetings. Of the 39 issues analysed, 9 took place fully or primarily within the Eurogroup and required unanimity for the decision. As for the Commission, we expect it to have relatively more influence on issues where the main decisions are made following the ordinary legislative procedure (OLP), which combines a monopoly over the initiation of legislation on the part of the EC with qualified majority for decisions in the Council of Ministers (in addition to majority in the European Parliament), thus granting the Commission significant agenda setting power over the issue in question (Pollack, Citation1997). 12 of our 39 issues were decided on through the community method.

Complexity: While issue complexity is a challenging variable to measure directly, we believe that a good proxy for it is represented by the number of different initial negotiating positions existing on any given issue. This is based on a twofold argument: for one thing, we expect issues with more facets and implications to naturally give rise to a greater range of opinions among participants than simpler issues. For another, the multiplicity of positions may itself become a source of complexity, insofar as it requires negotiating parties to gain more information about the bargaining landscape and consider the ramifications of a greater number of possible solutions. As the number of initial positions in our dataset ranges from one to four, we operationalize this variable dichotomously, with simple issue having up to two different bargaining positions (26 issues) and complex ones having three or four positions (13 issues).

Salience: Similarly to the case of complexity, we operationalize salience by proxy, looking at the number of expressed, or in any case recognizable, negotiating positions (as opposed to non-positions) for each issue. This operationalization is based on the idea that more politically salient issues will generate more interest and clearer bargaining positions among member state governments. On the other hand, the less salient the topic, the greater the chances that a member state may be less adamant about it, at the extreme even overlooking the issue altogether by not expressing any position. The variable is modelled in four a priori categories based on the number of member states expressing a negotiating position on any give issue: one to seven; eight to 14; 15–21; and 22–28. The first category is empty, therefore the analysis will only include the remaining three categories, containing seven, 16, and 16 issues respectively.

The result of the ordinary least squared (OLS) regression are presented in . As a robustness check on our results, we have also run logit regressions, modeling our dependent variable as dichotomous rather than continuous (0 for bargaining failure, 1 for success, with the cut-off at 50). The results of the logit models, which are consistent with the OLS, are presented in online appendix E.

Table 1. Ordinary least squares regression results.

The first result that stands out in is the consistently positive, and statistically significant, effect of the Commission coalition variable on member states’ bargaining success in all the seven models estimated. Being aligned with the EC is associated with a reduction of the distance between a country’s initial position and the negotiated outcome by roughly 27–51 points out of 100, depending on the model. This, in turn, suggests a potentially strong pull effect on the part of the Commission in the negotiations under scrutiny. Almost the exact opposite happens in the case of coalitions with the European Central Banks, which have a statistically significant and negative effect on member states’ bargaining success in six out of seven models. In other words, whereas the Commission appears, overall, like a ‘winner’ in EMU negotiations, the ECB seems to be systematically on the losing side.

Interestingly, the ECB’s bargaining weakness is confirmed, and even amplified, in the negotiating setting that one could expect to be most favorable to it, i.e., the Eurogroup, where being in a coalition with the Bank correlates negatively with a state’s average negotiating success by 21 points, as opposed to the 12 points of the overall effect (model 3). The EC’s effect, on the other hand, moves in the expected direction, increasing—albeit not by much: from 27 to 29 points (model 2)—when interacted with the most favorable setting of the ordinary legislative procedure.

The complexity interaction term yields unexpected results for both the ECB and the Commission. In the former case, and similarly to what happens for the Eurogroup interaction term, complexity increases the negative effect of the ECB coalition term on negotiation success (model 5). The EC case is even more notable, for here complexity reverses the effect of the overall coalition variable (model 4). Put differently, within an overall context in which the Commission is faring quite well bargaining-wise, the subset of complex policy issues appears instead to be a very adverse environment for this actor.

A similar dynamic, but this time more in line with expectations, is registered for the salience interaction term, which has a negative effect for both the Commission and the ECB (models 6 and 7 respectively), indicating that both actors tend to be on the losing side of negotiations on politically salient issues. Regression coefficients are large and significant for both salience categories. As for controls, finally, they all behave as expected.

Discussion and conclusion

What do these results tell us with regard to this article’s main research questions, namely whether and to what degree recent EMU reform negotiations have been characterized by technocracy? To the extent that our findings can be summarized in a single answer, they lend only partial support to the ‘technocratic EU’ thesis: technicians have certainly played a role in the important juncture examined here, but not nearly as much as one would infer based on the most categorical assessments of the EU as a technocratic regime of the sort presented in the introduction to this article. This is, on the whole, consistent with our initial expectation that technocracy is more realistically interpreted as a continuum rather than an absolute phenomenon. Looking at our results more closely reveals, however, a number of interesting findings in the context of the current debate on EU technocracy (some of which are likely to be relevant also regarding the EU’s responses to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic).

The strongest evidence against the idea of the EU as a technocracy comes from our findings on the European Central Bank. Perhaps the Union’s most quintessentially technical institution (at least as far as its formal setup is concerned), the ECB has been shown here not only to be losing systematically when bargaining against its political principals—a result which can be seen as the exact opposite of technocracy as it has been defined here—but also to be unable to improve its performance in those contexts that should be more favorable (or at least less unfavourable) to it, namely when negotiating over more complex policy issues and/or within the restricted setting of the Eurogroup.

These results contrast sharply with much of the recent work on the ECB, which has described the Bank as playing a leading role in tackling the euro crisis and its aftermath, often (arguably) going beyond the perimeter of its price stability mandate (Schoeller, Citation2018; Tortola & Pansardi, Citation2019; Verdun, Citation2017). It should be clear that our findings do not deny these accounts, but rather add an interesting piece to the story of the ECB during the crisis, showing that no matter how prominent its place has been in the EU’s recent economic policy-making, when interacting horizontally and more directly with member states, the Bank has retreated to a more submissive relationship vis-à-vis the political sphere. This, in turn, opens a number of important questions about the relationships that may exist between political-technical bargaining situations of the sort examined here, and the more traditional sequential setting that sees the ECB as the technical implementer of a previously set political mandate, and which is the basis of most existing analyses of the Bank during the euro crisis. In particular, future research could explore whether dominance by political actors in the framework of horizontal negotiations might not be a factor that encourages instances of technocracy at the implementation stage, by providing technical bodies with an incentive to rebel ‘through the backdoor’ (Falkner et al., Citation2004).

It is on the side of the European Commission that this study has found most evidence of technical influence over EMU negotiations. The Commission has proved rather influential vis-à-vis member states both in general terms, and predictably more so in the advantageous procedural context of the ordinary legislative procedure. These too are findings that run counter a significant portion of recent EU scholarship, which has portrayed the EC’s role in EU policy-making on the decline, and the Union veer towards an intergovernmental model over time, especially as a result of the euro crisis (e.g., Bickerton et al., Citation2015; Fabbrini, Citation2013; Puetter, Citation2012. But see Bauer & Becker, Citation2014 and Schimmelfennig, Citation2015 for dissenting takes). By showing that the Commission has been, on average, able to affect the outcomes of negotiations located at the core of EU crisis management, the analysis presented here casts more than a few doubts on this intergovernmental narrative. In this respect, our results are consistent with recent work by Lundgren et al. (Citation2019b), who have analysed the influence of the EC—along with the European Parliament and the ECB—in EMU negotiations, in order to appraise the EU’s supranationalism.

Granted, the EC’s bargaining success observed here might, in principle, have been due to a strategic ability to place itself close to outcomes identified as more likely to materialize (Kreppel & Oztas, Citation2017). This is an important potential counterargument to our findings, which deserves careful consideration. One possible way to estimate the likely outcome of a negotiation is by looking at the average position of all member states, or a plausible combination thereof. From our initial data we have calculated three such average positions for each of issues under scrutiny: EU28, Eurozone (EZ), and the average position of the Eurozone’s three biggest members, namely Germany, France and Italy (EZ3). Comparing these with the EC’s position on the 39 issues reveals not only substantial differences between them but also, and more importantly, the absence of any significant correlation. The latter, in particular, is an important initial indication of the independence of the EC’s negotiating positions vis-à-vis the member states.Footnote4

The foregoing leaves a more ‘situational’ version of the counterargument examined here, whereby the Commission assesses likely bargaining outcomes on a case-by-case basis, based on the specifics of the issues under negotiation. Testing this hypothesis would require a qualitative tracing of the Commission’s preference formation in the various EMU reform issues, which is outside the scope and space of this article. We have, however, strong indications that such a reading of EMU negotiations could at best explain only some of the considerable bargaining pull on the part of the Commission which we have documented here. From a theoretical standpoint, this counterargument implies a somewhat inconsistent view of the EC as an institution as weak as to have hardly any volition of its own, and yet sophisticated enough to foresee individual bargaining outcomes. Second, and more importantly, this counterargument runs counter to a growing body of in-depth analyses of Eurozone crisis policy-making, which has shown the Commission to be able to form genuinely independent preferences and achieve important objectives in its interactions with member states. This includes work on a number of prominent policy issues included in our dataset, such as the reform of the Stability and Growth Pact (Schön-Quinlivan & Scipioni, Citation2017), the Fiscal Compact (Smeets & Beach, Citation2020), the European Stability Mechanism (Smeets et al., Citation2019), and the banking union (Epstein & Rhodes, Citation2016). This research in turn links to a broader empirical literature documenting the Commission as a largely autonomous institutional actor, whose ability to influence EU policy-making certainly varies according to circumstances, but should not be outright dismissed even in less favorable contexts such as treaty reform (e.g., Christiansen, Citation2002; Christiansen & Jørgensen, Citation1998; Dimitrakopoulos & Kassim, Citation2005; Falkner, Citation2002).

We regard our findings about the Commission as only a partial confirmation of the technocracy thesis, for two reasons. First, and most obviously, because of the direction and magnitude of the effect observed for the salience interaction term, which shows the influence of the Commission vanishing when salient issues are under negotiation. Read together with the remaining results, this denotes a rather compartmentalised type of power on the part of the Commission, whose effect on bargaining outcomes is remarkable on the whole, as discussed above, yet tends to be concentrated disproportionally on issues that are deemed less important by the member states. In sum, to the extent that technocracy can be said to be exercised by the Commission, this is clearly conditional.

The second reason takes us back to the hybrid nature of the Commission, as described earlier in the article, and to the simple observation that whatever influence the EC has exerted over the EMU negotiations examined here, it has done so as an institutional actor that is, at the same time, technical in certain respects and political in others. Needless to say, it is only to the former facet of the Commission that our findings on the presence of technocracy in the EU can be applied. Looking at our empirical results, one might also argue that it is because of this hybrid nature that the Commission has not been able to prevail in the context of complex policy issues, where we would expect a purely technical actor to have a bargaining edge. But clearly this cannot be more than speculation at this point.

What is more important to note here about the dual nature of the Commission is that, while its two sides are inseparable in practice, when considered from a more theoretical point of view they have profoundly different implications, above all on the legitimacy of the Union. Political domination on the part of a supranational technical actor is an unequivocal distortion of the democratic principle, the redressing of which can only take place by pushing experts back into their appropriate decision-making confines. The influence of a supranational political player, on the other hand, does not necessarily pose a problem of legitimacy for the Union, so long as the gap separating it from voters—what is commonly known as the democratic deficit—can be filled satisfactorily. In light of this article’s results, it is therefore particularly important to dig deeper, both analytically and empirically, into the hybrid nature of the Commission in order to, first, unpack the various components of each of the two facets with greater precision, and second, assess systematically if and how the balance between them has changed over time. It is only by gauging, with more accuracy than has been done so far, whether the Commission is on a trajectory of ‘politicization’, or conversely it is becoming a more technical actor, that we will be able to establish to what extent the type of supranational influence documented here constitutes an instance of technocracy. This will, in turn, have important consequences on our normative appraisal of the European Union’s political order.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (122.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Gabriel Farkas for excellent research assistance, and the members of the ‘EMU choices’ project for access to data (www.emuchoices.eu). For helpful comments to previous versions of this article, we also thank Pamela Pansardi, Piero Salvagni, two anonymous reviewers, and participants in the 2019 conference of the European Communities Studies Association-Switzerland, the 2019 conference of the University Association for Contemporary European Studies, the 2020 conference of the Swiss Political Science Association, the colloquium of the Centre for the Study of Democratic Cultures and Politics at the University of Groningen, and the working lunch of the Institute of European Global Studies at the University of Basel.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Pier Domenico Tortola

Pier Domenico Tortola is assistant professor of European Politics and Society at the University of Groningen, the Netherlands.

Silvana Tarlea

Silvana Tarlea is senior researcher in the Social Sciences Department and the Institute for European Global Studies of the University of Basel, Switzerland.

Notes

1 For the sake of clarity, and coherence with the definition of technocracy adopted here, hereafter the term ‘technician’ will be used to indicate any expert who participates in policy-making within the formal and expected boundaries of his/her role (that is, without having undergone the above-mentioned distortion in his/her relationship with representative politicians, which would turn him/her into a ‘technocrat’).

2 To mention a well-known recent example, consider the recent political and legal disputes over some of the non-standard monetary policy measures introduced by the European Central Bank (ECB) to tackle the euro crisis and its consequences, above all the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) and quantitative easing (QE). Are these measures to be considered fully within the mandate and rights of the ECB, or should they be seen, conversely, as an unwarranted intrusion on the part of the Bank into the Eurozone’s economic policy-making—thus constituting a case of technocracy?

3 For comprehensive accounts of the unfolding of the euro crisis, and the political and institutional reactions to it, see Bastasin (Citation2015) and Tooze (Citation2018).

4 The mean distance between the Commission’s position and the three averages is 39.7, 36.5, and 35.5 points respectively. Pearson coefficients between the EC positions and those of the EU28, EZ and EZ3 member states are 0.14, 0.21, and 0.3 respectively. See online appendix F for further details.

References

- Arregui, J., & Thomson, R. (2009). States’ bargaining success in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(5), 655–676. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760902983168

- Bailer, S. (2004). Bargaining success in the European Union: The impact of exogenous and endogenous power resources. European Union Politics, 5(1), 99–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116504040447

- Balfour, R., & David-Wilp, S. (2016). Five Myths about the European Union. Washington Post, July 15. Retrieved September 15, 2019, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/five-myths-about-the-european-union/2016/07/15/2f254ffa-49da-11e6-bdb9-701687974517_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.e6191f935db0.

- Bastasin, C. (2015). Saving Europe: Anatomy of a dream. Brookings Institution Press.

- Bauer, M. W., & Becker, S. (2014). The unexpected winner of the crisis: The European commission’s strengthened role in economic Governance. Journal of European Integration, 36(3), 213–229. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2014.885750

- Bickerton, C., Hodson, D., & Puetter, U. (2015). The new inter-governmentalism: European integration in the post-maastricht Era. Journal of Common Market Studies, 53(4), 703–722. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12212

- Bueno de Mesquita, B., & Stokman, F. N. (1994). European community Decision Making: models, Applications, and Comparisons. Yale University Press.

- Christiansen, T. (2002). The role of supranational actors in EU treaty reform. Journal of European Public Policy, 9(1), 33–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760110104163

- Christiansen, T., & Jørgensen, K. E. (1998). Negotiating treaty reform in the European Union: The role of the European Commission. International Negotiations, 3(3), 435–452. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1163/15718069820848319

- Coombes, D. (1970). Politics and bureaucracy in the European Community. Allen & Unwin.

- Dimitrakopoulos, D. G., & Kassim, H. (2005). Inside the European Commission: preference formation and the convention on the future of Europe. Comparative European Politics, 3(2), 180–203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.cep.6110056

- Eckstein, H. (1975). Case studies and theory in political science. In F. I. Greenstein, & N. W. Polsby (Eds.), Handbook of Political Science. political Science: Scope and Theory (pp. 94–137). Addison-Wesley.

- Epstein, R. A., & Rhodes, M. (2016). The political dynamics behind Europe’s new banking union. West European Politics, 39(3), 415–437. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2016.1143238

- Fabbrini, S. (2013). Intergovernmentalism and its limits: Assessing the European Union’s answer to the euro crisis. Comparative Political Studies, 46(9), 1003–1029. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414013489502

- Falkner, G. (2002). How intergovernmental are intergovernmental Conferences? An example from the Maastricht treaty reform. Journal of European Public Policy, 9(1), 98–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760110104190

- Falkner, G., Hartlapp, M., Leiber, S., & Treib, O. (2004). Non-compliance with EU Directives in the member states: Opposition through the backdoor? West European Politics, 27(3), 452–473. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0140238042000228095

- Gelman, A., & Hill, J. (2007). Data Analysis Using Regression and Hierarchical/Multilevel Models. Cambridge University Press.

- Gerring, J. (2007). Is there a (viable) crucial-case method? Comparative Political Studies, 40(3), 231–253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414006290784

- Gunnell, J. G. (1982). The technocratic image and the theory of technocracy. Technology and Culture, 23(3), 392–416. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3104485

- Högenauer, A-L, & Howarth, D. (2016). Unconventional monetary policies and the European Central Bank's problematic democratic legitimacy. Journal of Public Law, 17(2), 1–24.

- Jones, E., & Matthijs, M. (2019). Rethinking Central Bank independence. Journal of Democracy, 30(2), 127–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2019.0030

- Kassim, H., & Laffan, B. (2019). The Juncker presidency: The ‘political commission’ in practice. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(S1), 49–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12941

- Kreppel, A., & Oztas, B. (2017). Leading the band or just playing the tune? Reassessing the agenda-setting powers of the European Commission. Comparative Political Studies, 50(8), 1118–1150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414016666839

- Laird, F. N. (1990). Technocracy revisited: Knowledge, power and the crisis in energy decision making. Industrial Crisis Quarterly, 4(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/108602669000400103

- Lundgren, M., Bailer, S., Dellmuth, L. M., Tallberg, J., & Târlea, S. (2019a). Bargaining success in the reform of the Eurozone. European Union Politics, 20(1), 65–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116518811073

- Lundgren, M., Tallberg, J., & Wasserfallen, F. (2019b). Supranational Influence in the Reform of the Eurozone. Paper presented at the PEIO Conference. Salzburg, 7-9 February.

- Matthijs, M., & Blyth, M. (2017). Theresa May’s Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day Explains Why Democracy Is Better than Technocracy. Washington Post - Monkey Cage. October 5. Retrieved September 15, 2019, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/10/05/theresa-mays-horrible-no-good-very-bad-day-explains-why-democracy-is-better-than-technocracy/?utm_term=.e2bcd16143ab.

- Meynaud, J. (1969). Technocracy. The Free Press.

- Mounk, Y. (2018). The undemocratic dilemma. The Journal of Democracy, 29(2), 98–112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2018.0030

- Naurin, D. (2007). Network Capital and Cooperation Patterns in the Working Groups of the Council of the EU. European University Institute RSCAS Working Paper 14.

- Peterson, J. (2017). Juncker’s political European Commission and an EU in crisis. Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(2), 349–367. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12435

- Pettit, P. (2004). Depoliticizing democracy. Ratio Juris, 17(1), 52–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0952-1917.2004.00254.x

- Pollack, M. (1997). Delegation, agency, and agenda setting in the European community. International Organization, 51(1), 99–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/002081897550311

- Puetter, U. (2012). Europe’s deliberative intergovernmentalism: The role of the Council and European Council in EU economic governance. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(2), 161–178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.609743

- Radaelli, C. M. (1999). Technocracy in the European Union. Longman.

- Sánchez-Cuenca, I. (2017). From a deficit of democracy to a technocratic order: The postcrisis debate on Europe. Annual Review of Political Science, 20(1), 351–369. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-061915-110623

- Sartori, G. (1987). The Theory of Democracy Revisited - Part Two: The Classical Issues. Chatham House Publishers.

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2015). What's the News in New Intergovernmentalism: A Critique of Bickerton, Hodson and Puetter. Journal of Common Market Studies, 53(4), 723–730. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12234

- Schneider, C. (2018). The Responsive Union: National elections and European Governance. Cambridge University Press.

- Schoeller, M. G. (2018). Leadership by default: The ECB and the announcement of outright monetary transactions. Credit and Capital Markets, 51(1), 73–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3790/ccm.51.1.73

- Schön-Quinlivan, E., & Scipioni, M. (2017). The Commission as policy entrepreneur in European economic governance: A comparative multiple stream analysis of the 2005 and 2011 reform of the Stability and Growth Pact. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(8), 1172–1190. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1206140

- Scicluna, N. (2014). Politicization without democratization: How the Eurozone crisis is transforming EU law and politics. International Journal of Constitutional Law, 12(3), 545–571. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/mou043

- Shapiro, M. (2005). ‘Deliberative,’ ‘independent’ technocracy v. democratic politics: Will the globe Echo the E.U.? Law and Contemporary Problems, 68(3/4), 341–356.

- Smeets, S., & Beach, D. (2020). Political and instrumental leadership in major EU reforms. The role and influence of the EU institutions in setting-up the fiscal compact. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(1), 63–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2019.1572211

- Smeets, S., Jaschke, A., & Beach, D. (2019). The role of the EU institutions in establishing the European stability mechanism: Institutional Leadership under a Veil of Intergovernmentalism. Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(4), 675–691. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12842

- Tarlea, S. (2018). Parties, Power and Policy-Making: From Higher Education to Multinationals in Post-Communist Societies. Routledge.

- Tarlea, S., & Bailer, S. (2020). Technocratic governments in European negotiations. In E. Bertsou, & D. Caramani (Eds.), The technocratic challenge to democracy (pp. 148–164). Routledge.

- Tarlea, S., Bailer, S., Degner, H., Dellmuth, L. M., Leuffen, D., Lundgren, M., Tallberg, J., & Wasserfallen, F. (2019). Explaining governmental preferences on economic and monetary union reform. European Union Politics, 20(1), 24–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116518814336

- Tarlea, S., & Freyberg-Inan, A. (2018). The education skills trap in a dependent market economy. Romania’s case in the 2000s. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 51(1), 49–61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postcomstud.2018.01.003

- Thomson, R., Arregui, J., Leuffen, D., Costello, R., Cross, J., Hertz, R., & Jensen, T. (2012). A new dataset on decision-making in the European Union before and after the 2004 and 2007 enlargements (DEUII). Journal of European Public Policy, 19(4), 604–622. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2012.662028

- Tooze, A. (2018). Crashed: How a decade of financial crises changed the world. Allen Lane.

- Tortola, P. D. (2020a). Technocracy and depoliticization. In E. Bertsou, & D. Caramani (Eds.), The technocratic challenge to democracy (pp. 61–74). Routledge.

- Tortola, P. D. (2020b). The politicization of the European Central Bank: What is it, and how to study it? Journal of Common Market Studies, 58(3), 501–513. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12973

- Tortola, P. D., & Pansardi, P. (2019). The Charismatic leadership of the ECB presidency: A language-based analysis. European Journal of Political Research, 58(1), 96–116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12272

- Verdun, A. (2017). Political Leadership of the European Central Bank. Journal of European Integration, 39(2), 207–221. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2016.1277715

- Vibert, F. (2007). The rise of the unelected: Democracy and the new separation of powers. Cambridge University Press.

- Wallace, W., & Smith, J. (1995). Democracy or technocracy? European integration and the problem of popular consent. West European Politics, 18(3), 137–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01402389508425095

- Wasserfallen, F., Leuffen, D., Kudrna, Z., & Degner, H. (2019). Analysing European Union decision-making during the Eurozone crisis with new data. European Union Politics, 20(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116518814954

- Wille, A. (2013). The normalization of the European Commission: Politics and bureaucracy in the EU executive. Oxford University Press.

- Winner, L. (1978). Autonomous technology: Technics-out-of-control as a theme in political thought. MIT Press.