ABSTRACT

In policy research, the search for the correct balance between proximity and independence has never been easy. Policymakers need proximity to the research in order to ensure that it is relevant. Yet, there are also concerns about the rigour of research. To analyze this relationship in more detail, this paper focuses on the ‘extreme case’ of the WODC in the Netherlands, an internal but formally independent research unit of the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security. Research methods include semi-structured interviews and a survey (N = 673). We conclude that government leans on WODC researchers in all phases of the policy research process. In most cases, WODC researchers successfully resist pressure from policymakers, yet continuing pressure may easily lead to research methods, conclusions and press releases being altered for policy reasons. Finally, there are general lessons drawn from the WODC case that will assist in achieving a good balance between proximity and independence in policy research.

Introduction

In December 2017, the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security hit the headlines. According to a popular current affairs programme, senior justice ministry officials directly interfered with independent research into the ministry’s own soft drugs policy (Dutch_News, Citation2017). This research was carried out by the Research and Documentation Centre (WODC), an internal but formally independent research unit of the ministry. According to the news report, researchers altered unwelcome conclusions and reformulated research questions at the request of officials. The aim was to manipulate the findings to ensure they supported existing policy rather than criticized it. In response to the news report, the Minister of Justice ordered an independent public inquiry. This study draws on the empirical case study of this inquiry (Hertogh et al., Citation2019). The WODC case is interesting because it provides unique data on the important proximity – independence balance in policy research.

In recent decades, there has been growing attention given to evidence-based policymaking (EBP) (Pleger & Sager, Citation2018), in which the policy researchers play an important role. Particularly in the differentiated polity (Bevir, Citation2010), there is a need for the best available evidence as well as proof of demonstrable results. Yet the EBP movement has also shown that in democracies, evaluations are carried out within, and are influenced by, a political context (Pleger & Sager, Citation2018). The search for the correct balance between proximity and independence in policy research (or policy evaluation) has never been easy. Proximity of policymakers to the research is needed to ensure that the policy research is relevant, and their influence is important in determining the relevant questions. Some speak of the ‘perennial problem’ that research outcomes are not translated appropriately into practice, or that the research is not seen as relevant in the context it was designed for (Buick et al., Citation2015). Yet, in addition to concerns about relevance in the research-practice gap, there are also concerns about the rigour of research (Morris, Citation2015). To provide evidence, researchers must follow scientific guidelines, but proximity brings the risk of undue influence. After all, policymakers and their political superiors have an interest in good publicity. Even away from the glare of mass publicity, apparent endorsement or challenge by a scientific evaluation can make a policy or programme substantially stronger or more vulnerable to its opponents or competitors. As Bovens et al. (Citation2006, p. 321) write, ‘[i]t is only a slight exaggeration to say, paraphrasing Clausewitz, that policy evaluation is nothing but the continuation of politics by other means’.

Arguably, in differentiated governance and mediatized politics (Hajer, Citation2009; Meyer & Hinchman, Citation2002) the need for good publicity is greater than ever. However, this is not yet fully reflected in the literature. The LSE GV314 Group (Citation2014, p. 225) argues, for example, that

[d]espite the interest in “evidence-based policy”, and the use of political values in the use of evidence (Boswell, Citation2008; Fischer, Citation2003; Hope, Citation2004; MacGregor, Citation2013; Sabatier, Citation1978), there has been rather scant attention devoted to understanding the impact of political constraints on the production of research under contract for government.

Thus far, most literature has been focused on evaluation theories (Leeuw & Donaldson, Citation2015), methodologies and guidance for making value judgments. By contrast, there is less attention on the governance – the various ways of organizing – of policy research (Schoenefeld & Jordan, Citation2017, p. 275). For that reason, it will be problematized here with the aim of answering the following research question, consisting of two parts: what is the nature of the relationship between the policymaker and the policy researcher in the WODC case in the Netherlands, and what can we learn from this to achieve a balance between proximity and independence in policy research?

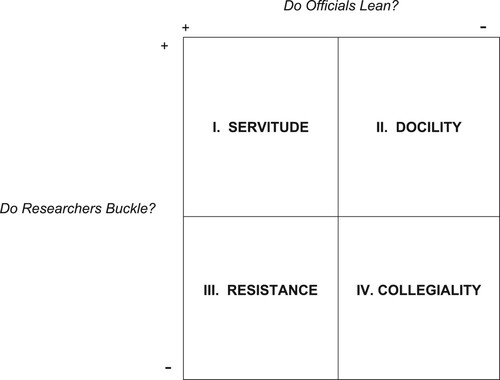

In the next section, there will first be a brief review of current research into policy evaluation. This will be followed by a discussion of the analytical framework for studying the nature of the relationship between policymaker and policy researcher. Determined by whether government is ‘leaning’ on researchers and whether researchers ‘buckle’ under the pressure, the framework characterizes this relationship as ‘servitude’, ‘docility’, ‘resistance’, or ‘collegiality’. Next, the background to the WODC case will be explained, and the methods and data used for the case study. Based on the findings from the case study, an analysis of the nature of the policymaker – policy researcher relationship in the WODC case will be offered. The conclusion of the case study will indicate that, despite the formal ambition to facilitate ‘collegiality’, in practice, this relationship is characterized by a situation of ‘resistance’. To shed light on this contradiction, the system of checks and balances in the WODC case will come under scrutiny. The final part of this paper will reflect on what emerges from the WODC case. What are the general lessons that may be drawn from this extreme case? Are there some important theoretical takeaways from this case study? In addition, ‘what works’ in the governance of policy research will be outlined, along with several suggestions which may help the movement towards a situation of ‘collegiality’. The study will conclude with a brief summary and a look at balancing proximity and independence in policy research in the future. Moreover, it will be argued that especially during the Covid-19 pandemic and in times of ‘fake news’ and ‘fact free politics’ – the lessons from the WODC case are also relevant for policymakers and policy researchers outside the Netherlands.

Policy research under pressure: towards an analytical framework

State of research

In the past, most research on policy evaluation primarily focused on ethical principles, guidelines and conventions and usually had a normative character (See Pleger et al., Citation2017, p. 317). More recently, however, there has been an increase in empirical studies that examine the personal experiences of evaluators in relation to ethical problems and dilemmas. Morris and Clark (Citation2013), for example, undertook an anonymous survey among members of the American Evaluation Association. In their study, 42% of the 950 respondents had encountered pressure to misrepresent findings. Within this subgroup, 70% reported that they had been pressured in more than one evaluation (Morris & Clark, Citation2013, p. 60/61). In another study, the LSE GV314 Group (Citation2014) conducted a survey among 205 academics in the United Kingdom who had recently completed research commissioned by the government. In this study, only 17% of the respondents said they had experienced no pressure from government officials throughout the evaluation process. Based on these studies from the US and the UK – plus two other similar studies from Germany (Stockmann et al., Citation2011) and Switzerland (Pleger & Sager, Citation2016) – Pleger et al. (Citation2017, p. 321) conclude that ‘independence of evaluations does not exist for many respondents’ and that ‘pressure to misrepresent findings is common in evaluation’ (Pleger et al., Citation2017, p. 321).

What is ‘undue’ influence?

In previous studies, it has often been argued that the collaboration between policymakers and policy researchers ‘must not involve influence by the hiring party to guarantee objective and independent evaluation processes and therefore evaluation results’ (Pleger & Sager, Citation2018, p. 166). In other words, influence is consistently perceived as a phenomenon to be judged in normative terms as negative. However, ‘influence always plays a role in the event of a client-contractor relationship’ (Pleger & Sager, Citation2018, p. 169) and some influence may also be positive, for example, the earlier mentioned importance of relevance and the proximity of policymakers. To do justice to this ambivalence of influence, Pleger and Sager (Citation2018) have introduced a sliding scale of support, betterment, undermining and distortion. In this paper, the focus is on the last two categories, and pressure is understood as ‘a negative influence by a stakeholder, which reaches far beyond the collaborative stakeholders’ involvement in the evaluation process’ (Pleger et al., Citation2017, p. 316/317). To evaluate influence on evaluators, a distinction needs to be made between formal ‘independence-in-the-books’ (reflected in rules and organizational structures) and substantial ‘independence-in-action’ (reflected in everyday practice). Formal independence means ‘structural freedom from control over the conduct of evaluation’ (Pleger & Sager, Citation2018, p. 167). Substantial independence can be described as ‘the objective scientific assessment of a subject, free from undue influence that is meant to distort or bias the conduct or findings of an evaluation’ (Pleger & Sager, Citation2018, p. 167). Both types of independence are strongly interconnected. The level of formal independence influences the level of substantial independence, and vice versa. To classify the influence on evaluators as positive or negative, one needs to look at the intention behind the influence. In the remainder of this paper those types of contact between policymakers and researchers that are aimed at influencing or distorting an evaluation for policy reasons will be qualified as ‘undue influence’. Any type of contact that is aimed only at the correction of small factual errors or missing references, for example, is excluded from this category. Needless to say, there is still a grey area between these two extremes and it will not always be easy to distinguish between the categories. This is also reflected in the operationalization in this study of ‘undue influence’ (see below).

The nature of the policymaker – policy researcher relationship

To classify the nature of the policymaker – policy researcher relationship, the LSE GV314 Group (Citation2014, pp. 225–226) has developed a helpful analytical framework. This framework is based on two dimensions: whether government is ‘leaning’ on researchers and whether researchers ‘buckle’ under the pressure and produce politically supportive research reports. This results in four different types of relationship between policymakers and policy researchers (see ). When policymakers lean and researchers buckle, there is a situation of ‘servitude’ (Field 1). When government doesn’t lean, but researchers do buckle, their relationship is characterized as ‘docility’ (Field 2). Researchers might be motivated to do so, because they might suspect that a favourable evaluation will increase their chances of future research contracts. They might think they have an idea of what government would like to hear, and produce a report accordingly, even without undue government influence. ‘Resistance’ is the relationship where government leans, and researchers do not buckle (Field 3). ‘Collegiality’ is when government does not lean and researchers do not buckle (Field 4).

This analytical framework will be applied here in the analysis of the WODC case.

Background to the WODC case

In-house policy research

The Scientific Research and Documentation Centre (WODC) of the Ministry of Justice and Safety is an internal but formally independent part of the Ministry. With an annual budget of 12 million euro and a staff of 100 fte, it publishes around 90 research reports each year on subjects related to security, police, criminal, civil and administrative justice and migration issues. On average, 30% of its research is carried out by WODC researchers themselves and 70% is carried out by external researchers (commissioned by the WODC). The WODC policy researchers can be classified as ‘in-house’ evaluators. In this role, they may have intimate knowledge of policy processes and the circumstances under which a particular policy emerged, which may in turn make the evaluation more attuned to these and other contextual variables (Toulemonde, Citation2000; Weiss, Citation1993). Careful attention to such factors may eventually facilitate the uptake of evaluation knowledge later on in the policy process (Weiss, Citation1993). Furthermore if governmental actors fund evaluation activities, they may be under considerable pressure to act upon related findings (Schoenefeld & Jordan, Citation2017, p. 277). Yet there are also several well-known weaknesses to in-house evaluations. Evaluation findings by governmental evaluation actors may be less critical of a given policy and its outcomes than evaluative knowledge generated by non-state actors (Weiss, Citation1993). Political pressures to ‘look good’ and avoid negative evaluations may be acute and thus inhibit formal actors from being too critical. If unfavorable evaluation results do emerge, governmental actors may have an incentive to suppress them or not draw attention to them if they are published (Schoenefeld & Jordan, Citation2017, p. 277).

Proximity and independence?

What are the consequences of the rather unique institutional setting of the WODC for our understanding of the balance between proximity and independence? Most of the literature cited thus far focuses on researchers based at a university. Their position is very different from WODC researchers who, as government employees, work for a research unit within a ministry. According to its mission statement, the WODC wants to conduct ‘scientific, policy oriented research’. Some emphasize the latter element of this description. In their view, the institutional setting of the WODC – and its proximity to politics – implies that ultimately policy relevance is more important than independent research. Others, however, take a different position. They emphasize the first element in the WODC’s mission statement. They argue instead that, although it is a research unit of a ministry, all WODC studies still need to be based on objective scientific research. This is also reflected in the (literal translation of) the WODC’s Dutch name: the Scientific Research and Documentation Centre. All relevant legal rules and regulations clearly state that – although their research is policy oriented – WODC researchers should be able to conduct their research free from undue influence from policymakers that is intended to distort the findings of an evaluation (see below). This position is shared by other similar research institutions in the Netherlands. The WODC is part of a wider network of 13 public knowledge organizations and planning agencies (so called ‘RKI institutions’). Together they cover a wide range of domains – from climate, social and economic science, statistics, public health and public safety to cultural heritage and more. All these research institutions are formally independent but still remain in one way or another connected to a specific ministry. According to the chair of this network, the research conducted by these RKI institutions is not different from the research at universities:

- A researcher at an RKI institution is engaged in scientific research in the same way as a researcher at a university. […] The mission of universities is to conduct top research and to provide excellent education. The mission of an RKI institution is to generate knowledge for society. (cited in: Schoonen, Citation2017)

- An important shared value [of all RKI institutions, including the WODC] is the scientific independence of the research, which has to be periodically externally reviewed and evaluated.Footnote1

Research methodology

In this study, an explorative and inductive research strategy is used (De Graaf & Huberts, Citation2008; De Graaf & Meijer, Citation2019; Eisenhardt, Citation1989; Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). A single case study design focuses on understanding the dynamics present within single settings (Eisenhardt, Citation1989; Herriott & Firestone, Citation1983; Yin, Citation1989). This method is fitting when not much is known about a phenomenon that is being researched, or when the phenomenon is so complex that neither the variables nor the exact relationship between the variables is fully definable (Hoesel, Citation1985), as is the case with the research question at hand. As explained before, the WODC case will be treated as an ‘extreme case’ that reveals more about the policymaker – policy researcher relationship (Blijenbergh, Citation2010; Jahnukainen, Citation2010).

Operationalizing undue influence

In order to determine the nature of the policymaker–policy researcher relationship, the inquiry focused on the scope of (potential) cases of ‘undue influence’ on WODC research by government officials of the Ministry of Justice and Security. The notion of ‘undue influence’ was operationalized based on the norms and principles from several relevant codes of conduct.Footnote2 For example, the Netherlands Code of Conduct for Research Integrity (2018) defines five principles of research integrity, including independence:

Independence means, among other things, not allowing the choice of method, the assessment of data, the weight attributed to alternative statements or the assessment of others’ research or research proposals to be guided by non-scientific or non-scholarly considerations (e.g., those of a commercial or political nature). In this sense, independence also includes impartiality. Independence is required at all times in the design, conduct and reporting of research, although not necessarily in the choice of research topic and research question.Footnote3

The evaluation process can be divided into three (chronological) stages: commissioning and designing the research; managing the research; and writing up and publishing the results (The-LSE-GV314-Group, Citation2014, p. 326). Based on these three stages, the case study focused on the following aspects to assess the nature and scope of (potential) ‘undue influence’:

– Whether the research design of WODC studies has been modified for policy reasons in the direction of the preferred outcome by the policymaker.

– Whether the choice of method, the assessment of data, or the weight of WODC studies has been attributed to alternative statements, or whether the assessment of others’ research or research proposals has been guided by non-scientific or non-scholarly considerations (e.g., those of a commercial or political nature).

– Whether WODC research has been postponed or published prematurely for policy reasons; or whether the press release has been altered for policy reasons.

As stated, in order to classify the influence on researchers as positive or negative, one needs to look at the intention behind the influence that policymakers seek to have. Cases of ‘undue influence’ focus on those interventions to influence or distort an evaluation for policy reasons. However, in empirical research it may not always be possible to reveal the ‘real’ motives behind the interventions of a policymaker (or policymakers may disguise their policy motives as, for example, technical or methodological comments). To overcome this, the respondents were asked what they themselves saw as cases of ‘unwanted influence’ by policymakers (which was defined as: ‘a situation in which a researcher feels so much pressure that they decide to change the design or the outcome of a study, against his/her conviction’).Footnote4

Research techniques

This study used a mixed-methods design, which included semi-structured interviews, a survey and a study of relevant documents. The fieldwork was conducted from January – December 2018.

First, a hotline was established and all those who had information that could be relevant for the WODC-case were invited to respond. In total, 17 people shared their experiences and concerns.

Also, 19 additional interviews were conducted with (former) researchers, (former) managers, external researchers, research coordinators and (former) policymakers and directors. This approach was chosen to prevent negative (selection) bias, which could play a role if the study was exclusively based on the (negative) experiences of those who contacted the hotline.

To assess the generalizability of both the hotline reports and the additional interviews, an online survey was conducted among WODC researchers, policymakers at the Ministry of Justice, external researchers and (former) members of a supervisory committee (N = 673). The questionnaire was based on the outcome of the interviews. Of 96 WODC researchers who were invited to participate, 51 filled out the questionnaire (response rate 53%). In total 192 policymakers from the Ministry of Justice were invited, of whom 84 participated in the survey (44%). Of the 445 external researchers who were invited, 178 completed the questionnaire (40%) and of the 1,555 members of supervisory committees who were invited, 360 (31%) responded. Overall, this means that the survey results are sufficiently representative for all four groups of respondents. The response rates in this study are similar to those in several previous surveys on this subject (e.g., Morris & Clark, Citation2013).

To gain a better understanding of the process of ‘undue influence’, several WODC evaluation studies were selected. The aim was to analyze the nature rather than the scope of undue influence. For this, four cases in the policy field of justice and security were selected that were frequently referred to during the interviews as possible examples of undue influence. These case studies were based on several hundred emails and other relevant documents.

In addition to the hotline notifications, the interviews, the survey results and the detailed studies, several other sources and documents were also studied (including minutes of parliamentary debates, WODC annual reports and employee satisfaction surveys).

Heuristic of research

As stated, the case study was designed to focus on understanding the dynamics present within single settings in order to draw general lessons (Gersick, Citation1988; Harris & Sutton, Citation1986). To find patterns and arrive at these lessons, Eisenhardt suggests using techniques that force investigators to go beyond initial impressions. First impressions of overall patterns were observed and then juxtaposed with the empirical data. This inductive process is clearly not a matter of counting. The idea is to consider the nuances and context of ‘undue influence’. Constant comparison was conducted (Boeije, Citation2010), in which the researchers repeatedly go through the themes to compare results. This inductive analysis process was repeated many times before the final analysis was written up.

Results: the nature of the policymaker – policy researcher relationship

Leaning

In many of the interviews, WODC researchers (but also external researchers and former members of a supervisory committee) say they recognize the pattern of undue influence as it was reported in the media. For example, one WODC researcher states:

- The news about the WODC is true; this is no isolated incident […]. People are put under pressure in many different ways.

- I recognize policy pressure as a dilemma, but I don’t think this pressure is unbearable. Researchers should be able to resist this pressure.

Our case study shows that government leans on researchers in all phases of the research process. Some researchers report (attempts) of undue influence during the design phase:

- Because of the possibility that the results would not be positive and would be potentially politically sensitive, they did not want to include certain research questions in a study.

- It was asked if the figures from the previous year could be used, because the year in question was unfavourable.

- During a discussion of the final report, […] a policymaker from the Ministry of Justice (who was also a member of the committee) wanted certain parts of the text to be amended or removed. This was based on policy arguments. I did not give in to this.

- [I recall several] attempts to influence one of the conclusions of a study by a Justice official in the supervisory committee who used “track changes” to indicate the desired modifications in the text. After several unpleasant discussions about this, we did not give in.

In response to these and other reports, one Justice official explains:

- I’m aware that suggestions to change the text are being made. That is a normal type of interaction.

Buckling

What are the consequences if government officials lean on researchers? More than one third of the WODC researchers (34.8%) say that this has a negative effect on the independence of their research. Almost a quarter of them (21.7%) also feel that it affects the integrity of their work. Researchers were also asked if they gave in to the pressure from policymakers. Some WODC researchers simply did what they were asked to do. One of them recalls:

- We didn’t leave anything out of the report, but we did move certain findings into a footnote which I would have preferred to have seen in the main text. I’ve accepted my loss.

Another way in which policymakers may influence WODC research, is by postponing the publication of a report or by altering the press release. According to the WODC Protocol, reports should be made public within 6 weeks. When this period is extended for policy reasons (and, for example, the publication of an evaluation study is deliberately postponed until after a crucial policy debate to avoid critical political questions), this may affect the weight and (hence the independence) of the conclusions. Nearly ten percent of the WODC researchers (9.8%) have witnessed a report being published later, or not published at all, for policy reasons. Some former members of supervisory committees (10%) and external researchers (6.7%) have had similar experiences. In addition, the Ministry of Justice and Security sometimes presents the outcomes of a research report in a different light to gain good publicity for their policies. In one of the interviews, a Justice official explains that, in his view, this is all in the game:

- We want to present a certain picture to Parliament. We have to sell a message. As a policy official you have reached certain conclusions. In your presentation, therefore, you show certain findings that support your conclusion and other findings you don’t show.

Discussion: from ‘resistance’ to ‘collegiality’

The WODC case not only helps us to understand the nature of the Dutch policymaker – policy researcher relationship. It also gives us a better view of the governance of this relationship: ‘what works’ in the organization of a good collaboration between policymakers and researchers?

On paper, the formal positioning of the WODC reflects the ideal of ‘collegiality’ (The-LSE-GV314-Group, Citation2014). This is a situation where government does not lean and researchers do not buckle. In other words, ‘both parties have equivalent objectives and are committed to the goal of truth seeking’ (Manzi & Smith-Bowers, Citation2010, p. 141). However, the previous section has demonstrated that the real nature of the policymaker – policy researcher relationship in the WODC case is more similar to a situation of ‘resistance’. This raises the following questions: how did the WODC organize the collaboration between policymakers and policy researchers? And why did these provisions fail, resulting in a situation of ‘resistance’?

In the WODC case, there were two important checks and balances to guarantee a situation of ‘collegiality’: firstly, a formal agreement (or: ‘Protocol’) between the Secretary-General of the Ministry of Justice and Security and the WODC director; and secondly, an independent supervisory committee for each WODC study. In everyday practice, however, neither provision was able to stop the repeated attempts at ‘undue influence’ by government officials.

Protocol

When the Dutch minister of Justice and Security was first interviewed about the allegations that senior Justice Ministry officials had directly interfered with independent WODC research, he told journalists that he was confident that with the (recently updated) Protocol in place, this could no longer happen. On closer inspection, however, the Protocol only provided a very basic framework for regulating the relationship between the Ministry and the WODC. Most importantly, it explicitly prohibited any ‘direct orders’ from officials aimed at interfering with WODC research. Other than this, however, the Protocol contained scarcely any concrete norms or rules to regulate this relationship. Many WODC researchers state that the Protocol ‘did not contain much of interest’ and they consider the Protocol as a ‘weak story to regulate things’. As a result, the Protocol plays only a marginal role in everyday practice. In the survey, only 23.5% of all WODC researchers and 26.3% of the Ministry of Justice officials indicate that (prior to the media reports about the WODC case) they were (fully) aware of the content of the Protocol. Even after the WODC case was widely reported by the national media, only 21.6% of the WODC researchers and 29.8% of the Ministry of Justice officials indicate that the Protocol plays an important role in their organization.

Supervisory Committee

Each WODC study is accompanied by an independent supervisory committee that monitors the scientific quality, the independence, the policy relevance and the overall planning of the project. Each committee includes several experts and is usually chaired by a university professor. In principle, it is agreed that each committee may only include one government official (usually connected to the department that commissioned the study). In practice, however, there is sometimes pressure to include more government officials from different departments, which in some cases may shift the power balance in the committee. In the survey, some of the WODC researchers (7.8%), external researchers (10.7%) and Justice officials (10.7%) say that they have witnessed the composition of the supervisory committee being changed for policy reasons.

In the interviews, the respondents describe many examples in which government officials used their position in the supervisory committee to lean on WODC researchers. One former committee member describes his experience as follows:

- [O]n many occasions the government officials who were part of the supervisory committee attempted to influence the results. I was often surprised they made no effort to hide this. An official would simply say: “at this moment, these results are not opportune”.

- There was always a lot of discussion with the supervisory committee about citations, footnotes and texts. With regard to citations, also a lot of things happened outside the committee.

Reflections on the WODC case

Generalization

The general conclusion from the WODC case is that government leans on researchers in all phases of the policy research process. In most cases, WODC researchers successfully resist pressure. Yet, continuing pressure may easily lead to methods, conclusions and press releases being altered. The WODC was labelled as an ‘extreme case’. As indicated earlier, the WODC is an internal but formally independent research unit of the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security. Compared with the experience of most other policy researchers (who work at a university), this is a unique institutional setting. Moreover, all WODC reports are related to justice and security issues. Both of these elements mean that the findings from the WODC may not simply be generalized to other cases (and to other policy fields). However, drawing on the findings from the WODC case, we can theorize about the relationship between policymakers and policy researchers in other cases. Firstly, as stated before, the institutional setting of the WODC is similar to the situation of other (‘RKI’) public knowledge organizations and planning agencies in the Netherlands (which cover a wide range of policy domains). Consequently, some of the WODC findings may also apply to the 13 other RKI’s in the Netherlands. Secondly, in the survey external researchers (who work at universities) reported similar experience of undue influence as (internal) WODC researchers.Footnote5 This means that some lessons from the WODC case may also apply to university researchers (commissioned by the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security). Finally, the findings from the WODC case echo important findings from previous case studies in the US, the UK, Germany and Switzerland (see, e.g., Pleger et al., Citation2017). This suggests that some of the general lessons from the WODC case may also be relevant outside the Netherlands.

Theoretical reflections

The WODC case shows that the analytical framework, which was introduced by the LSE GV314 Group (Citation2014), is a useful tool for studying the nature of the relationship between policymaker and policy researcher. However, there are three theoretical takeaways from this case study which may be used to further improve this typology. Firstly, considering the difference between formal and material independence, it may be useful to make a distinction between ‘leaning’ and ‘buckling’ in-the-books and in action. Secondly, considering the grey area between ‘due’ and ‘undue influence’, the framework may also look at different degrees of ‘leaning’ and ‘buckling’. Thirdly, by adding a more dynamic element to the framework, it may better describe the movement from ‘collegiality’ to ‘resistance’, and vice versa.

The governance of a good policymaker – policy researcher relationship

Considering the limits of the checks and balances evident in the case of the WODC, what would be a more fruitful way of organizing good collaboration between policymakers and policy researchers? Based on the findings from the WODC case study, the following three recommendations can be made:

(1) From weak norms to solid rules

Firstly, it is easier to facilitate and maintain a situation of ‘collegiality’ when there are rules that clearly define and limit the separate roles of the policymaker and the policy researcher. In the case of the WODC, the Protocol was largely ignored because it was considered a weak document which lacked any clear guidelines for everyday use. However, a large majority of WODC researchers (80.4%) and external researchers (83.7%) – as well many Justice officials (63.1%) – are in favour of clear standards of conduct to regulate the relationship between policymakers and policy advisors. Also, many WODC researchers (54.9%) and external researchers (60.7%) support the idea of safeguarding the independent position of the WODC by legislation.

(2) From formal to informal influence

Secondly, the governance of the relationship between policymaker and policy researcher should also take into account informal practices of ‘undue influence’. The WODC Protocol explicitly prohibits ‘direct orders’ to change the research methods, results or conclusions of WODC studies. However, the findings from the case study indicate that ‘undue influence’ is usually not translated into formal decisions. Instead, it is often the outcome of a much more subtle and hidden process. For example, rather than a direct request in which policymakers would ask WODC researchers to change their conclusions, they would make suggestions that they review their report for ‘methodological reasons’, or junior researchers would be informally invited for a personal meeting with a high-ranking director of a policy unit. In other words, ‘undue influence’ is usually not a matter of (direct and explicit) ‘distortion’, but it is more often an enduring (indirect and more discrete) process of ‘undermining’ (Pleger & Sager, Citation2018, p. 170). These informal practices cannot be limited by formal rules and regulations alone. This also requires an important culture shift. For example, the Ministry of Justice and Security should formulate a number of key principles for determining a good policymaker – policy researcher relationship. Most importantly, it should be clear that policymakers can have a say on the research topic and the research question (what), but that interference with the choice of method and conclusions (how) is not allowed. Moreover, in a supervisory committee, the proper role of the policymaker is that of an expert. He/she should not act as the representative of the Ministry. Finally, policymakers should be aware of their role in the policymaker – policy researcher relationship and they have to be transparent about their input at all stages of the research process. These principles should be translated into clear guidelines for everyday practical use. Finally, the Ministry could use these guidelines to train their officials.

(3) From individual to institutional focus

Thirdly, commentators in the WODC case and in other similar cases often focus on the position of individual researchers. In their view, the best way to limit undue influence, is to ask researchers to show ‘moral courage’ (Kidder, Citation2005) and ‘do the right thing’ and ‘simply resist’ the pressure from policymakers (Morris & Clark, Citation2013, p. 68). However, a malfunctioning relationship between the policymaker and the policy researcher is not only an individual, but also an institutional problem. In the WODC case, for example, there was a lack of strong organizational safeguards, there was no clear internal complaints procedure and some WODC researchers (19.6%) and Justice officials (10.2%) felt that signals of misconduct were not taken seriously by their managers. In response to these findings, the governance of a good policymaker – policy researcher relationship should also support a strong internal system of quality control. Among other things, this may include regular ‘intervision’ sessions (in which researchers share their experiences and dilemmas in relation to cases of undue influence) and these experiences should also become part of the training of new employees. In addition, a ‘chief science officer’ (or a similar official) – appointed at both the Ministry and the research centre – seems a good idea. The officers should be responsible for monitoring the independence of research. Finally, to underscore the independent position of a research centre, it might be better to locate the centre (which is presently housed in the same building as the Ministry of Justice and Security) outside the Ministry.

Conclusion

In order to understand the relationship between policymakers and policy researchers, the extreme case of the WODC in the Netherlands was studied. As stated, the WODC is an example of an internal but formally independent research unit of a government ministry, in which much care has been taken to minimize the weakness inherent in having in-house researchers. In other words, on paper the formal positioning of the WODC reflects the ideal of ‘collegiality’, in which government officials and researchers have the same objectives and both are committed to the goal of truth seeking. However, the real nature of the policymaker – policy researcher relationship in the WODC case is very different and more similar to a situation of ‘resistance’. In all phases of the research process, Justice officials lean on WODC researchers. In most cases, WODC researchers successfully resist pressure from policymakers, yet continuing pressure may easily lead to research methods, conclusions and press releases being altered for policy reasons. To restore the correct balance between proximity and independence in policy research – and to move from ‘resistance’ to ‘collegiality’ – it was argued here that several steps need to be taken. These include providing solid rules, making a culture shift, and adopting an institutional focus.

Finally, even though this case study was conducted before the Covid-19 pandemic, the study has become more topical because of it. Every day we are reminded just how much governments around the world depend on scientific expertise. Policymakers are in dire need of their policies being based on reliable advice that is trusted by the public. Yet, given the impact on society of the pandemic and related government policies, the stakes for policymakers are high. Early evaluations of the government response during the Covid-19 pandemic also illustrate the search for the right balance between proximity and independence in policy research. While some scholars argue, for example, that crises like these demand that ‘politicians rely on experts and refrain from second guessing people who know a lot more than they do’ (Mazey & Richardson, Citation2020, p. 566), others claim that an arms-length relationship between policy and research ‘risks diminishing its value and impact’ and it is therefore argued that ‘[g]etting the right questions and useful answers requires much closer engagement’ (Freedman, Citation2020, p. 520). The WODC case in the Netherlands shows that when government officials lean too much on researchers, this may eventually undermine the quality and the rigour of their work. To prevent similar situations of ‘undue influence’ in Covid-19 decisions, it could be argued therefore that policymakers can have a say on the research topic and the research question (what), but that their interference with the choice of method and the conclusions (how) should not be allowed. Moreover, the WODC case clearly illustrates that a fruitful way of organizing good collaboration between policymakers and policy researchers requires a robust set of checks and balances. Considering the growing global importance of evidence-based policymaking – especially during a pandemic and in times of ‘fake news’ and ‘fact free politics’ – these lessons from the WODC case are also relevant for policymakers and policy researchers outside the Netherlands.

Acknowledgment

The authors acted as one the members (De Graaf) and chair (Hertogh) of the Investigative Committee WODC II, which conducted the public inquiry into the WODC case.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gjalt de Graaf

Gjalt de Graaf is Full Professor of Public Administration and Head of the Department of Political Science and Public Administration at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. His research focusses on the quality (and normativity) of public governance, especially conflicting public values.

Marc Hertogh

Marc Hertogh is Full Professor of Socio-Legal Studies at the University of Groningen. His research focuses on law and governance, with a special interest in street-level bureaucracy, administrative justice and legitimacy.

Notes

2 These included: The Code of Conduct for Integrity in the Central Public Administration (aimed at justice officials); the Netherlands Code of Conduct for Research Integrity (aimed at the quality and integrity of scientific research); and the WODC Protocol (aimed at WODC researchers).

3 Netherlands Code of Conduct for Research Integrity (Citation2018, p. 13). See: https://www.vsnu.nl/files/documents/Netherlands%20Code%20of%20Conduct%20for%20Research%20Integrity%202018.pdf.

4 Pleger et al. (Citation2017, p. 316) have used a similar question in their US survey: ‘In your evaluation work, have you ever felt pressured to misrepresent, in a written report or oral presentation, any of the findings from a study you conducted?’

5 While one quarter of (29.4%) of WODC researchers indicated that they had experienced unwanted influence from justice officials during the past two years; this was also true for a similar number of external researchers (23%) and former members of a supervisory committee (23.9%).

References

- Bevir, M. (2010). Democratic governance. Princeton University Press.

- Blijenbergh, I. (2010). Case selection. In A. J. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Wiebe (Eds.), Encyclopedia of case study research (pp. 61–63). SAGE Publications.

- Boeije, H. (2010). Analysis in qualitative research. SAGE Publications.

- Boswell, C. (2008). The political functions of expert knowledge: Knowledge and Legitimation in european Union Immigration policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 15(4), 471–488. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760801996634

- Bovens, M. A. P., ‘t Hart, P., & Kuipers, S. (2006). The politics of policy evaluation. In M. Moran, M. Rein, & R. E. Goodin (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of public policy (pp. 319–335). Oxford Univeristy Press.

- Buick, F., Blackman, D., O'Flynn, J., O'Donnell, M., & West, D. (2015). Effective practitioner-scholar relationships: Lessons from a coproduction partnership. Public Administration Review, 76(1), 35–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12481

- De Graaf, G., & Huberts, L. (2008). Portraying the nature of corruption. Using an explorative case-study design. Public Administration Review, 68(4), 640–653. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2008.00904.x

- De Graaf, G., & Meijer, A. (2019). Social media and value conflicts. An explorative study of the Dutch police. Public Administration Review, 79(1), 82–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12914

- Dutch_News (Producer). (2017). Justice ministry manipulated studies into cannabis policy, says Nieuwsuur. https://www.dutchnews.nl/news/2017/12/justice-ministry-manipulated-studies-into-cannabis-policy-says-nieuwsuur/.

- Eisenhardt, K. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308385

- Fischer, F. (2003). Reframing public policy: Discursive politics and deliberative practices. Oxford University Press.

- Freedman, L. (2020). Scientific advice at a Time of Emergency. SAGE and Covid-19. The Political Quarterly, 91(3), 514–522. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12885

- Gersick, C. (1988). Time and transition in work teams: Toward a new model of group development. Academy of Management Journal, 31, 9–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/256496

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine.

- Hajer, M. (2009). Authoritative governance: Policy making in the age of mediatization. Oxford University Press.

- Harris, S., & Sutton, R. (1986). Functions of parting ceremonies in dying organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 29, 5–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/255857

- Herriott, R. E., & Firestone, W. A. (1983). Multisite qualitative policy research: Optimizing description and generalizability. Educational Researcher, 12(2), 14–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X012002014

- Hertogh, M., Peters, M., Van der Zande, A., & De Graaf, G. (2019). Ongemakkelijk onderzoek: Naar een betere balans in de relatie tussen WODC en beleid. Onderzoekscommissie WODC II.

- Hoesel, P. H. M. V. (1985). Het programmeren van sociaal beleidsonderzoek: analyse en receptuur. Universiteit Utrecht: Dissertation.

- Hope, T. (2004). Pretend it works: Evidence and governance in the evaluation of the Reducing Burglary Initiative. Criminal Justice, 4(3), 287–308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1466802504048467

- Jahnukainen, M. (2010). Extreme cases. In A. J. Mills, G. Durepos, & E. Wiebe (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Case Study Research (pp. 379–381). SAGE Publications.

- Kidder, R. M. (2005). Moral Courage. William Morrow.

- Leeuw, F., & Donaldson, S. (2015). Theory in evaluation: Reducing confusion and encouraging Deabte. Evaluation, 21(4), 467–480. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389015607712

- MacGregor, S. (2013). Barriers to the influence of evidence on policy: Are politicians the problem? Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 20(3), 225–233. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/09687637.2012.754403

- Manzi, T., & Smith-Bowers, B. (2010). Partnership, servitude, or expert Scholarship? The Academic Labour process in contract Housing research. In C. Allen & R. Imrie (Eds.), The knowledge business: Critical perspectives on contract research (pp. 133–147). Ashgate.

- Mazey, S., & Richardson, J. (2020). Lesson-Drawing from New Zealand andCovid-19: The need for anticipatory policy making. The Political Quarterly, 91, 561–570. https://doi-org.vu-nl.idm.oclc.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12893

- Meyer, T., & Hinchman, L. (2002). Media democracy: How the media colonize politics. Polity Press.

- Morris, M. (2015). Research on evaluation ethics: Reflections and a agenda. New Directions for Evaluation, (148), 31–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.20155

- Morris, M., & Clark, B. (2013). You want Me To Do WHAT? Evaluators and The pressure to misrepresent findings. American Journal of Evaluation, 34(1), 57–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214012457237

- Netherlands Code of Conduct for Research Integrity. (2018). retrieved October 27, 2020 from, https://www.nwo.nl/en/documents/nwo/policy/netherlands-code-of-conduct-for-research-integrity

- Pleger, L., & Sager, F. (2016). Don't Tell Me Cause It Hurts. Zeitschrift für Evaluation, 15(1), 23–59.

- Pleger, L., & Sager, F. (2018). Betterment, undermining, support and Distortian: A Heuristic Model for the analysis of pressure on evaluators. Evaluation and Program Planning, 69, 166–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2016.09.002

- Pleger, L., Sager, F., Morris, M., Meyer, W., & Stockmann, R. (2017). Are some countries more prone to pressure evaluators than others? Comparing findings from the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and Switzerland. American Journal of Evaluation, 38(3), 315–328. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214016662907

- Sabatier, P. (1978). The Acquisition and Utilization of technical information by administrative agencies. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23(3), 396–417. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2392417

- Schoenefeld, J., & Jordan, A. (2017). Governing policy evaluation? Towards a New typology. Evaluation, 23(3), 274–293. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389017715366

- Schoonen, W. (2017, 8 December). Wetenschap bij een Ministerie is Niet Anders dan die aan een Universiteit. Trouw.

- Stockmann, R., Meyer, W., & Schenke, H. (2011). Unabhängigkeit von evoluationen. Zeitschrift für Evaluation, 10(1), 17–38.

- The-LSE-GV314-Group. (2014). Evaluation under contract: Government pressure and the production of policy research. Public Administration, 92(1), 224–239. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12055

- Toulemonde, J. (2000). Evaluation culture(s) in Europe: Differences and convergence between national practices. Vierteljahrshefte zur Wirtschaftsforschung, 69(3), 350 –357. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3790/vjh.69.3.350

- Weiss, C. (1993). Where politics and evaluation reserach meet. Evaluation Practice, 14(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0886-1633(93)90046-R

- Yin, R. K. (1989). Case Study Research. Sage Publications.