ABSTRACT

With higher levels of polarization in the European Parliament (EP), mainstream groups increasingly face the trade-off between engaging and dismissing Eurosceptic challenger parties. Therefore, this article proposes a model to understand the strategies of mainstream and Eurosceptic groups in legislative work. It uses content analysis of legislative amendments to explain under what conditions these two sets of actors decide to engage with or disengage from each other. We compare two legislative packages, the more technical Circular Economy Package with the highly politicized Asylum Reform Package to assess how the choices of mainstream and Eurosceptic groups influence the survival of amendments and the success of the EP in trilogues. The comparison shows that politicization leads to more polarization and, subsequently, increases the chances that mainstream groups will collaborate with and copy soft-Eurosceptics along a left-right divide. At the same time, we also demonstrate that disengagement from Eurosceptic groups is closely related to their small size and limited resources. Finally, although the cordon sanitaire is systematically used to exclude hard Eurosceptics, it is not effective when it comes to isolating radical populist amendments proposed by soft-Eurosceptics and mainstream groups.

Introduction

Although Eurosceptic and populist forces fell short of the forecasts issued before the 2019 European Parliament (EP) elections, they still managed to gather around one-third of the seats (Ripoll Servent, Citation2019b). The rise in non-mainstream parties, as well as the Greens and liberals (Renew), marked the end of the long-standing ‘grand coalition’. However, this dynamic is not new – the previous legislative period (2014-2019) already experienced higher levels of polarization, which translated into unstable coalitions and a blurring of the left-right divide (Ripoll Servent, Citation2018). This shift in internal dynamics also had consequences for inter-institutional relations – since it made it more difficult for the EP to build a common position to represent in legislative negotiations, potentially affecting the EP’s chances of success under co-decision (Ripoll Servent & Panning, Citation2019a). Therefore, it is important to understand how the presence of more Eurosceptic and populist forces in the EP affects its role as co-legislator, especially in informal settings of decision-making, where individual members of the European Parliament (MEPs) may have higher chances to influence policy outputs.

The rise of Euroscepticism has affected dynamics in the EP in two different (albeit connected) ways. First, it has forced mainstream groups to choose between isolating and including Eurosceptics in the Parliament’s legislative work. This decision is made more difficult by higher levels of polarization, which have resulted in tighter majorities. Consequently, the ‘grand coalition +’ composed of the European People’s Party (EPP), Socialists and Democrats (S&D) and the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe (ALDE, now Renew) often faces a dilemma: if they wish to achieve the necessary majorities to form a strong position in Parliament, they need to count on the votes of (at least some) Eurosceptic groups. This defies the recurrent use of a ‘cordon sanitaire’, aimed to isolate Eurosceptics from the EP’s key decision-making structures (Ripoll Servent, Citation2019b). Second, the rise of Euroscepticism (and radical parties in general) has broken the pro-integration consensus that prevailed for decades and has polarized the positions of political groups on issues that are prone to populist capture, such as migration, economic governance, social policies and the rule of law (Blumenau & Lauderdale, Citation2018). We know little, however, about how these two challenges affect the process of position-building preceding trilogues. This stage is essential to understand the EP’s chances of success, especially since conflict management and coalition building occur before the vote on a trilogue mandate in committee or plenary. It is in this preparatory phase that we can examine how mainstream and non-mainstream groups collaborate (or not) in this compromise-seeking exercise.

EP mainstream parties are not the only ones to face these choices. On the domestic level, there is a burgeoning literature that examines how mainstream parties deal with radical parties and whether the strategies they adopt contribute to strengthening or diluting these challengers (Akkerman & Rooduijn, Citation2015; Downs, Citation2001). Meguid (Citation2005) has noted that most mainstream parties face a choice between dismissing these challenger parties and accommodating them through collaboration or by copying their core messages. We do not know, however, to what extent EP mainstream groups – which are made up of national parties potentially facing this trade-off back home – use similar strategies to deal with challenger parties and whether their strategies have an impact on the EP’s behaviour in trilogues. At the same time, we develop these theories further by proposing a more interactive model of strategic behaviour that sees the actions of mainstream and Eurosceptic groups as mutually reinforcing: as much as mainstream parties need to decide whether to engage or ignore Eurosceptic groups, the latter also face choices between participating or not in the EU’s legislative process.

To better understand the strategies adopted by these two sets of political actors, we propose an in-depth content analysis of legislative amendments, which allows us to identify the strategies deployed both by Eurosceptic and mainstream groups. To this effect, we have selected for comparison one prominent file out of two legislative packages – the Landfill Waste Directive (Circular Economy Package) and the Qualifications Regulation (Asylum Reform Package). These two packages have been selected to account for variation on the level of politicization and conflicts on the pro-anti integration cleavage: while the former was seen as a regulatory issue linked to the completion of the single market – and hence as of a more technical nature, the latter was highly politicized and raised key questions about the need to harmonize EU policies to deal with the ‘asylum crisis’. The comparison shows that there has been a process of convergence between mainstream and Eurosceptic groups – especially in those areas that are more prone to populist capture and emphasise the EU integration cleavage.

The article provides, first, an overview of how polarization has affected the role of Parliament in trilogues. We then develop a model to understand the strategies adopted by mainstream and Eurosceptic groups. We use the content analysis of committee amendments to examine the presence of these strategies and to compare the two legislative files.

Managing polarization in EP legislative work

Of all the EU institutions, the EP is the most affected by the increased levels of polarization and politicization. The shift towards a bicameral system has turned the EP into a full co-legislator but it has also transformed its internal dynamics. Indeed, the need to build coalitions that are strong enough to receive the support of the plenary and the Council urge EP rapporteurs to seek broad majorities – often across ideological cleavages (Costello, Citation2011; Costello & Thomson, Citation2011; Costello & Thomson, Citation2013; Finke, Citation2012). This is even more the case given the structural advantage that the Council enjoys under co-decision, since it is easier to vote down the EP’s amendments than reject the Council’s position in second reading (Hagemann & Høyland, Citation2010). In addition, the Council is usually in a better negotiating position, since it has the upper hand when it comes to expertise and implementation and is generally more comfortable than Parliament to return to the status quo if negotiations fail (Costello & Thomson, Citation2013; Kreppel, Citation2018; Thomson et al., Citation2006). Therefore, the more united Parliament is in co-decision, the more difficult it is for Council to reject its amendments (Finke, Citation2012). In contrast, if the negotiating team goes into trilogues with a weak majority and has limited room for manoeuvre (in the sense that any divergence from the mandate might preclude winning the vote in plenary), the easier it becomes for the Council to play divide-and-conquer (Delreux & Laloux, Citation2018; Trauner & Ripoll Servent, Citation2016).

This largely explains the predominance of grand coalitions and the central role of the liberal group in the last decade (Costello, Citation2011; Hix & Høyland, Citation2013). This search for broad majorities has been greatly affected by the rise in polarization: given the tight majorities in the eighth legislative period, the aversion of mainstream groups to form alliances with fringe parties – generally known as the ‘cordon sanitaire’ – has made it even more complicated to form ideologically-based coalitions and helped to reinforce the move to the centre and the blending of positions (Ripoll Servent, Citation2018; Rose & Borz, Citation2013). Added to that, the involvement of the EU in policy fields that affect core state powers, such as borders and taxation (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2016), intensifies the politicized nature of European integration. This, in turn, opens the field to new voting dimensions, based on pro- and anti- EU integration attitudes or the GAL-TAN cleavage, and an erosion of the traditional left-right divide (Hix et al., Citation2007; cf. Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009).

As a result, the preparatory stage preceding trilogues has become essential to manage coalition-building inside the EP. It is often here that rapporteurs have to decide whether they want to welcome non-mainstream groups in the committee-level negotiations and, eventually, into the majority supporting their report. Our research in the framework of the ‘Trilogues’ project has shown that, during the eighth legislative term, whether Eurosceptics were included or excluded from legislative work depended on a number of ‘soft factors’. First, not all Eurosceptics were perceived equally by mainstream MEPs; while some were seen (and saw themselves) as outcasts, others were treated as insiders and participated regularly in negotiations (interview 4; Ripoll Servent & Panning, Citation2019a). Second, inter-personal relationships between rapporteur and shadow rapporteurs mattered (cf. Judge & Earnshaw, Citation2011), as did the level of expertise shown by Eurosceptic MEPs (interviews 2, 3). Finally, the size of the groups or national delegations (for example in the case of the Italian Five Star Movement) was also crucial to understand both the willingness of certain groups/delegations to participate in legislative work but also of mainstream rapporteurs to include them (or not) in coalitions. Given that Eurosceptic groups were among the smallest in the EP, they often had to set priorities and preferred to spend resources such as staff and time for negotiations where they thought they might exert some influence (interviews 1, 5, 7, 8). In turn, their small size and Eurosceptic views made them less attractive as potential coalition partners for mainstream groups. Thus, they were often considered the last resort for a rapporteur who needed to ensure that a tight vote ultimately passed (interviews 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8).

Therefore, while formal aspects (such as voting majorities, distance between the positions of the co-legislators and ideological cleavages inside the Parliament) cast a long shadow over the process leading to an EP mandate, other informal considerations (expertise, personal relationships and trustworthiness) might also affect the dynamics of the negotiating team. These different factors show the importance of considering how bicameralism affects the process of preparation preceding trilogues and sets the scope conditions for influence in inter-institutional negotiations.

Strategies of engagement and disengagement

These scope conditions underline likewise the complex dynamics of inclusion and exclusion of Eurosceptic MEPs in preparatory stages. While their influence is not impossible, it is largely determined by how mainstream groups perceive them, e.g., whether they are seen as respectable, having valuable expertise or as necessary to build majorities. This means that both mainstream and Eurosceptic groups often face a trade-off: on the one hand, both types of political groups would prefer to work in isolation, since this prevents potential accusations of contamination and disloyalty towards their voters (cf. Bjerkem, Citation2016); on the other hand, the pressure to build strong majorities in a more divided Parliament makes it more difficult to ignore each other and might be seen by Eurosceptics as an opportunity to shape policy outputs (cf. Akkerman & Rooduijn, Citation2015).

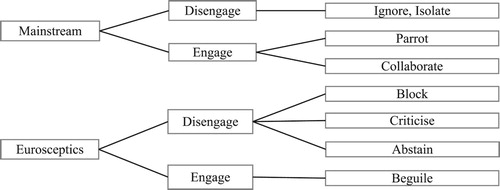

This trade-off is not unique to the EP; research on the interactions between mainstream and non-mainstream parties on the domestic level has shown similar patterns. There, mainstream parties often need to make a choice between using a ‘cordon sanitaire’ to isolate or ‘deep-freeze’ non-mainstream parties and engaging with them in legislative or executive work in an attempt to ‘tame’ them and bring them closer to the mainstream (Minkenberg, Citation2001; van Spanje & van der Brug, Citation2007). The effects of these strategies remain unclear. Some have noted that those facing a cordon sanitaire need to fight to maintain their relevance, while those not facing it tend to adopt office-seeking strategies that demonstrate their acceptability as potential political partners (Pauwels, Citation2011). Others, however, have shown that the use of a cordon sanitaire responds often to political culture or tradition, rather than ideology: while older non-mainstream parties are excluded by a cordon sanitaire, newer ones do engage with mainstream parties – even if they share a similarly radical ideology with the older parties (Akkerman & Rooduijn, Citation2015). Therefore, it shows that strategies can be complex, conditioned by time and political culture and that they need to be understood as an interactive process between mainstream and non-mainstream groups. We adapt this literature to formulate a model that helps us understand better the interactions between mainstream and Eurosceptic groups ().

Strategies of mainstream groups

We base the strategies of mainstream groups on the work of Downs (Citation2001) and Meguid (Citation2005) and adapt them to the behaviour expected in the process of building an EP position that precedes trilogues. As mentioned above, mainstream groups often face the dilemma whether to ostracize non-mainstream groups or engage with them. These choices may be conditioned by the ideological closeness of mainstream and non-mainstream parties, their respective size as well as the existence of practices, such as the use of a cordon sanitaire, that have been locked in over time (Downs, Citation2001). First, if mainstream groups decide to disengage and not work with Eurosceptics, we can expect mainstream MEPs to either ignore them (pretend they do not exist) or isolate them by building coalitions that exclude them. When looking at the process of amending legislation, our observations do not allow us to say whether there is an active effort to apply the cordon sanitaire or whether Eurosceptic groups are just being dismissed – therefore, we have decided to group these two categories together.

In contrast, if mainstream groups decide to engage with them, they may decide to either ‘parrot’ the message delivered by Eurosceptics (e.g., adopt a more critical tone against the EU or more radical policy positions) or collaborate with them, for instance co-sponsoring amendments (van Spanje & Graaf, Citation2018). The extent of the engagement might vary depending both on the ideological proximity between mainstream and Eurosceptic groups and on the level of polarization. Therefore, we expect mainstream groups to engage more with soft Eurosceptics like the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and the European United Left/Nordic Green Left (GUE/NGL) and to do so more when mainstream parties are polarized on a specific issue. That is, the more difficult it is to form a grand coalition, the more likely they (need to) engage with (soft) Eurosceptics (Downs, Citation2001; cf. Meijers, Citation2017).

Strategies of Eurosceptic groups

The strategies of non-mainstream groups have remained more implicit in the literature, which has tended to see these parties as reactive actors. However, we can equally envisage advantages and disadvantages for challenger parties in engaging or not with mainstream groups. If they disengage, it is easier to legitimise their position as outsiders, e.g., not being part of the political elite. These strategies may take different forms: first, they might decide to abstain, which would be in line with their tradition of absenting themselves as a way of rejecting the EP as a legitimate institution. Second, they might decide to voice their rejection by criticizing the work of the EU or the content of its policies, which is often used in domestic parliaments when non-mainstream parties sit in the opposition (Louwerse & Otjes, Citation2019). Finally, they might prefer to voice their opposition by blocking the work of other MEPs – for instance, introducing bogus amendments that will slow down negotiations. These strategies are more likely to be adopted by hard Eurosceptics of the Europe of Nations and Freedom (ENF) and Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD) (Brack, Citation2017; Whitaker & Lynch, Citation2014).

However, Eurosceptic MEPs might decide to engage and collaborate with mainstream groups. This might come as a response to the feeling that, if they systematically do nothing or have no success, people might see them as irrelevant and look for better alternatives (Pauwels, Citation2011). They might also want to be part of coalitions and engage in transforming EU policies; in this case, they will need to demonstrate that they can be constructive and able to draft acceptable amendments – that is, they need to beguile mainstream parties into believing that they can be respectable and serious partners (Akkerman & Rooduijn, Citation2015; Bjerkem, Citation2016; McDonnell & Werner, Citation2018). This strategy is more likely to be adopted by soft Eurosceptics like the ECR and the GUE/NGL, which have a tradition of being more pragmatic and accepting the rules of the game (Brack, Citation2017).

These strategies might not necessarily be exclusive: we could imagine that mainstream groups engage Eurosceptics both by parroting and collaborating with them at the same time; similarly, Eurosceptic MEPs could disengage from mainstream groups by both criticizing the positions of mainstream groups and blocking procedures. As for the order, we would expect that, if one or the other show a willingness to engage, this will make it easier or more likely for the other side to follow the same strategy, so that it produces a ratchet effect. However, when and how these strategies are deployed is ultimately an empirical question that needs to be assessed by examining the behaviour of specific actors and how they interact with each other.

Data and methods

In order to better understand these strategies, we examine the amendments submitted by all groups to the Commission’s legislative proposals. Amendments ‘may be tabled by the committee responsible, a political group or Members reaching at least [one-twentieth of component members or a political group]’ and can change any part of a text but not seek to delete or replace it entirely (EP Rules of Procedure, Rules 180-181). Although committees do not have exclusive rights to submit amendments nor any way of protecting their amendments in plenary, committee members enjoy an informational advantage and are more likely to influence the position of the EP (Yordanova, Citation2013). Therefore, examining amendments can provide information about committee dynamics – both in terms of ideological cleavages and collaborations in the form of co-sponsorships (Baller, Citation2017).

In order to examine the interaction between mainstream and non-mainstream groups, we offer first a descriptive quantitative overview detailing the number of amendments as well as their survival rate – both at the committee stage (i.e., integration into the EP’s report) and in trilogues (integration into the final agreement). To calculate the survival rate in trilogues, we use a scale from 0 to 1 to assess the level of incorporation of EP amendments into the final agreement. For instance, if only a small detail has been incorporated, we code it as 0,25; if almost everything has been incorporated but not everything, we code it as 0,75, etc. This is not an indication of the overall success rate of the EP, since it does not take into account new text incorporated into the final agreement, on which the EP did not submit any amendments (cf. Yordanova, Citation2013). We then analyse the content of the amendments made to the recitals to identify the groups’ strategies – looking for instance at the number of co-sponsored amendments, overlaps across the positions of the groups or bogus amendments. Recitals contain the legal and normative justifications underpinning a directive or regulation and allow us to better understand the different positions of the EP groups. The content analysis of recitals is, therefore, inductive and looks at amendments as a whole – not just keywords or phrases. The reform of the EU’s asylum system has been deadlocked due to the inability of member states to agree on a reform of the Dublin system. Therefore, our assessment of trilogue success is based on the latest version (18 June 2018) of the four-column document used to trace agreements in trilogues. To better understand the motivations for the strategic choices of the political groups, we have complemented the content analysis with elite interviews done with EP actors who participated in legislative negotiations (see online appendix, which also includes the bibliographical references to official documents used in the case studies).

We examine these patterns following a ‘most similar systems design’ (MSSD): the two files shared a series of characteristics related to the scope conditions delineated above. First, both files were led by S&D rapporteurs, which helps to control for the ideological bias of the rapporteur. Second, the rapporteurs managed to gather large support across the benches, which made them less dependent on the votes of Eurosceptic groups. Third, they were nested into two legislative packages – the Circular Economy package and the Asylum Reform package – that were key political priorities for the EP political groups. While the former (concluded in 2018) was part of Commission President Juncker’s ten legislative priorities, the latter became a main concern in the aftermath of the ‘refugee crisis’ of 2015–2016. At the same time, these files were substantially different in nature, with landfill of waste being seen as a technical and valence issue, while the Qualifications Regulations was prone to politicization and polarization on a left-right divide. Therefore, given that migration is more salient for populist and (far-)right groups than environmental/single market issues, the two case studies allow us to assess whether politicization has an impact on the strategies of both mainstream and non-mainstream groups and whether it leads to more polarization on the left-right axis (cf. Bale, Citation2008).

Strategies in the Circular Economy Package

The Commission first introduced the Circular Economy Package in July 2014 in order to amend the six existing directives. Besides the legally compulsory review of the EU’s waste management targets, the Commission also aimed to improve waste management, thereby contributing to the development of an EU-wide circular economy. The underlying rationale was that better waste management would have positive effects for the environment and climate. In March 2015, it withdrew its proposal on waste, as it wanted to introduce a more ambitious text and, in December 2015, it eventually introduced a new package including the Waste Framework, Landfilling, Packaging Waste and End-of-Life Vehicles Directives (European Parliamentary Research Service, Citation2018). The four directives were negotiated in trilogues as one package, so that rapporteur and shadow rapporteurs were the same for every directive. Overall, around 2.000 amendments were submitted by MEPs (interview 25). Due to the size of the package and its very technical nature, negotiations took long, with Parliament adopting the directives in April and Council in May 2018.

Landfill of waste

The revision of the Landfill Directive (2015/0274/COD) proposed to reduce the existing limits to the share of municipal waste landfilled in the member states from 35% by 2016 (as agreed in the old directive) to 10% by 2030. Instead of landfilling waste, member states should improve recycling and, thereby, reintroduce valuable materials back into the economic cycle (European Commission 2015; European Parliamentary Research Service, Citation2018). Conflicts between Parliament and Council centred on how to calculate the levels of targets as well as on definitions. Parliament wanted to introduce more ambitious targets than those proposed by the Commission, while Council, which was dominated by centre-right and conservative governments at the time of negotiations, took a more conservative stance (Council of the European Union 2017; European Parliamentary Research Service, Citation2018). Simona Bonafè (S&D, Italy), a member of the Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI) since July 2014, was nominated as rapporteur in December 2015. Her nomination is in line with the informal agreement that important legislative files should go to pro-European party groups (interviews 20, 23), which meant that EPP and S&D usually ended up leading the bigger ones as they had more points to spend during the bidding process.

Bonafè was able to secure a large majority with few MEPs abstaining or voting against the mandate and the final agreement. Only the majority of EFDD MEPs voted against the proposal in all three votes while the ENF first rejected the proposal and then abstained in the final vote (see Table A1 in the online appendix).

Therefore, the voting majorities were composed of all mainstream and soft-Eurosceptic groups, which supported the proposed directive through the different stages. This indicates that the proposal did not raise major conflicts among the main political groups, which saw the Circular Economy Package as a valence issue.

Turning to the survival of ENVI amendments, shows that S&D, GUE/NGL and ECR submitted the majority of amendments in the committee, which were also the most successful in surviving the first plenary vote on the EP mandate; since S&D provided the rapporteur, this is not surprising. The fact that GUE/NGL and ECR, as soft-Eurosceptic groups, actively engaged in the procedure and had a high survival rate compared to the other groups might explain why they decided to support the proposal and be part of the oversized majority. While EPP, ALDE and the M5S submitted a similar number of amendments, only ALDE was able to incorporate some amendments into the EP’s mandate. Surprisingly, only one EPP amendment was successful, while the M5S amendments were all dropped after the committee vote.

Table 1. Survival of amendments for the Landfill Directive.

The qualitative analysis of the amendments to the recitals shows that, in this case, the main cleavage did not run along a left-right divide; there was a wide support for eco-friendly attitudes, with a minority raising issues linked to de-regulation.

The valence nature of eco-friendly positions can be seen in amendments such as the change of the words ‘reducing/reduction’ to the much stronger ‘phasing-out’ proposed for example by Mark Demesmaeker (ECR; Amendments 40, 85), Josu Juaristi Abaunz and his colleagues from GUE/NGL (Amendment 61), and the M5S (Amendment 64). Excerpts from amendments with examples of cross-party efforts to introduce more control and stricter waste rules can be found in Table A2 in the online appendix. In contrast, another group, formed mostly by ENF but also three ECR MEPs, amended the Commission proposal to loosen controls and targets or stressed member states’ disparities. Examples of such amendments can be found in Table A3 of the online appendix.

The content analysis together with the survival rate of amendments shows that, in the case of the Landfill Directive, mainstream groups were willing to collaborate with Eurosceptic MEPs who were also pushing for a progressive proposal with more ambitious targets. The willingness to collaborate, however, only extended to the soft-Eurosceptic groups, which could reflect the EP’s wish to build a strong, ideologically robust majority before entering into negotiations with the Council (interviews 8, 22). In this case, this means that all the groups included in the coalition pursued the same goal, namely more ambitious targets and eco-friendly rules. A strong majority would give Parliament more leverage in trilogues, especially as the Council had generally welcomed the package proposal but had also voiced some concerns about ambitious targets (European Parliamentary Research Service, Citation2018). The efforts of the M5S to beguile the mainstream groups was unsuccessful though. Although their amendments were progressive, they often introduced smaller changes that had already been included in the amendments of other groups. This indicates that mainstream groups preferred to cooperate with each other and only reached out to Eurosceptic groups when the latter proposed new and progressive amendments. This behaviour resonates with more generalized practices, which means that the mainstream groups did most likely not set out to shun the M5S, but that their amendments were not competent or interesting enough to prompt mainstream groups to cooperate with a small fringe delegation that was not decisive to form a majority (interviews 7, 8, 21, 24).

The ENF focused on blocking procedures by tabling amendments that went counter to the goal of the Commission’s text, thereby clearly disengaging from the other groups. The EFDD chose to disengage as well but, contrary to the ENF, they preferred to fully abstain from the legislative process.

The analysis of the Landfill Directive suggests that, as expected, soft Eurosceptics tried to engage in the legislative process, beguiling mainstream groups with reasonable amendments, which made it easier for the latter to include them as partners. Hard Eurosceptics, on the other hand, chose to disengage by criticizing and blocking or fully abstaining from the process. The disengagement of mainstream groups towards the M5S shows that their attempt to beguile was unsuccessful. This is in line with previous findings that the M5S are ‘outsiders’ in the legislative work. As such, they are allowed to participate but mainstream groups do not see them as trusted partners and therefore bypass them when not needed to build a majority (Ripoll Servent & Panning, Citation2019a).

Strategies in the Asylum Reform Package

The reform of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) came as a response to the 2015 ‘refugee crisis’ and the failure to agree to a system of relocation quotas. The package comprised eight directives and regulations aiming to modify the existing legislative framework and added new provisions on the resettlement of asylum-seekers from outside the EU territory. The EP managed to find compromises on all the files, which helped to put pressure on the Council and underline the need to find a rapid response to the crisis. Despite these efforts, the package was considered deadlocked after a failed push for a compromise during the European Council of June 2018 (Ripoll Servent, Citation2019a). Therefore, although some files had been extensively discussed in trilogues and had reached a partial political agreement between Parliament and Council, the insistence of Parliament to maintain a ‘package approach’ and the attempts of some presidencies, notably the Austrian presidency in Autumn 2018, to re-open issues that had already been agreed meant that no solution could be found by the end of the eighth legislative term (interviews 16, 17, 18).

Qualifications Regulation

The Commission had proposed to upgrade the Qualifications Regulation (2016/0223(COD)) from a directive with a view to further harmonize the rules on who should receive asylum or other forms of international protection. It is, therefore, a key text that has often been criticized for its sloppy implementation on the ground, which de facto leads to an ‘asylum lottery’ – that is, very different chances to obtain international protection depending on where an application is submitted (Asylum Information Database, Citation2015). The text has been traditionally opposed by right-wing groups, since the more broadly it defines international protection, the more migrants might potentially be allowed to stay in the EU. Similarly, member states have been keen to keep the definitions broad, to have more flexibility when deciding on individual cases (Ripoll Servent & Trauner, Citation2014).

The file was led by Tanja Fajon (Slovenia, S&D), an active member of the LIBE committee since 2009. Despite being a controversial proposal, the rapporteur managed to gather a strong majority supported by most mainstream groups – although the EPP was internally divided (see Table A4 in the online appendix).

This majority, however, masks a report that had a clear left-wing bias. As shows, the Greens and the GUE/NGL were very active in proposing amendments to the text and had a high rate of success when it came to their incorporation in the EP report. Indeed, the rapporteur relied heavily on the Greens and, especially, the soft-Eurosceptics of the GUE/NGL to draft the report. Although submitted separately, many of the amendments written by these three groups (and in some cases also those written by the M5S) had the exact same wording. In comparison, the EPP was not very active and it fared worse than ALDE, which shows over twice a rate of survival in the EP report. What is also interesting to observe is the systematic use of a cordon sanitaire against the ENF and the EFDD members other than M5S MEPs. For the ECR, there is also a considerable gap between the number of amendments proposed and those accepted in the report (12,41 per cent compared to 1,32 per cent).

Table 2. Survival of amendments for the Qualifications Regulation.

When it comes to the inter-institutional agreement in trilogues, only around a third of EP amendments were taken into account, although this figure should be treated with caution. In fact, most of the successful amendments authored by the rapporteur, the Greens and the GUE/NGL overlap, which considerably reduces their actual success rate to around a third of what is indicated in the table. In practice, the left-wing bias of the report posed serious problems for the rapporteur in trilogues. Although she tried to use the wide majority received in the vote to put pressure on the Council (Interview 9, 10, 11, 19), member states were unhappy by the tone of the EP report and reluctant to stray away from the status quo (Interview 17).

A content analysis of the recitals shows interesting dynamics. When it comes to substantive positions, there is a clear left/right divide: left-wing groups stressed the need to incorporate the rights derived from the jurisprudence of the Court of Justice and the European Court of Human Rights and attempted to broaden the definition of family as well as the grounds of persecution; in comparison, right-wing groups put more emphasis on the issue of ‘secondary movements’ (going from one member state to another) and grounds for exclusion linked to terrorism and national security – concerns that largely resonated with those of the Council’s General Approach.

Three excerpts that show a significant overlap between the amendments produced by the EPP, ECR and ENF can be found in Table A5 of the online appendix. In all three cases, there is a clear reference to restricting the right to seek international protection to ‘deserving’ applicants, which is a typical nativist position linked to far-right and conservative parties. This position is to be expected from a member of the Italian Lega (Fontana) and the True Finns (Halla-aho), but it might be more surprising from a member of the French Les Républicains (Morano).

The issue of harmonization was also at the core of the EP debates. While some groups suggested an outright rejection of the Commission proposal (Amendment 96, Kristina Winberg, ECR; Amendment 97, Auke Zijlstra, Janice Atkinson, ENF) others proposed to undo the upgrade and keep it as a directive (Amendment 101, Jean Lambert, Greens). Table A6 of the online appendix shows that the reasons underpinning these amendments were very different: in the case of the EFDD, it was rooted in a belief that harmonization could/should not be achieved in such a sensitive area for member states. However, as the second example shows, similar justifications were shared by soft-Eurosceptic and mainstream groups. The scepticism expressed by the Greens and the GUE/NGL was rooted in another type of concern: they considered that, if the only aim of more harmonization was to build a ‘Fortress Europe’, they preferred to stick to a directive and allow some member states to have higher standards of protection (Interview 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, see also Amendment 103, Barbara Spinelli, Malin Björk, GUE/NGL).

However, it is interesting to see that none of these proposals to limit the scope of harmonization made it into the final report, which shows the resilience of pro-European positions. In the end, only 87 of the initial 232 amendments proposed for the recitals survived in the report and, of those, only 28 were successful in the inter-institutional agreement. Among the latter, most were only partially incorporated and any attempts to broaden the scope of the Regulation to include a wider definition of family members or to expand the rights of applicants were generally unsuccessful.

This analysis of the Qualifications Regulation helps us to better understand the strategies of mainstream and Eurosceptic groups. When it comes to the former, we see a clear use of the cordon sanitaire that allowed mainstream groups to disengage from the ENF and from the non-M5S members of the EFDD. This confirms previous findings that these groups are seen as outcasts and actively isolated by mainstream groups (Ripoll Servent & Panning, Citation2019a). This strategy does not necessarily respond to the ideological content of their amendments, given that the EPP parroted the anti-immigration and security-led positions of the far-right and populist parties from the ENF and ECR. In contrast, we saw more collaboration between the mainstream left-wing and soft Eurosceptics. Apart from the seven amendments co-sponsored by the Greens and the GUE/NGL, there is a large amount of parroting between the S&D rapporteur, the Greens, the GUE/NGL and, in fewer cases, the M5S. It is, however, impossible to say who is parroting whom or whether it is an indication of collaboration.

As for the Eurosceptics, the ENF and EFDD did submit quite a few amendments, which were mostly used to criticize the role of the EU in the area of migration and the unsuitability of harmonizing asylum policies. In some cases, the aim of their amendments was clearly to block proceedings, since they made suggestions – such as rejecting the entire proposal or deleting the mentions to the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions (see Amendments 99 and 100, Beatrix von Storch, EFDD) – that were inadmissible. These strategies were mostly mirrored by the ECR, especially given that their shadow rapporteur was a far-right member of the True Finns. In comparison, both the M5S and the GUE/NGL tried to beguile the mainstream groups by collaborating with them; as a result, they were seen as acceptable and part of a left-wing majority supporting the views of mainstream groups.

Conclusion

The comparison between the Circular Economy Package and the Asylum Reform Package shows that, indeed, politicization does make a difference when it comes to the strategies of mainstream and Eurosceptic groups. The second file was more extensively amended by all groups and showed higher levels of polarization on the left-right divide. Centre-right groups, in particular, tended to parrot or collaborate more closely with the soft-Eurosceptics from the ECR, while the centre-left was more welcoming to outsiders like the M5S. In comparison, the Circular Economy Package showed the tendency for eco-friendly positions to act as a valence issue – gathering a broad majority across benches.

At the same time, it also shows that the cordon sanitaire is still alive and kicking. The ENF and the EFDD (except for the M5S) were systematically excluded from coalitions and their amendments did not survive the preparatory stage. This confirms findings from our previous research, which showed how shadows meetings might give a voice to hard-Eurosceptics but did not offer them an actual chance to influence policy positions (Ripoll Servent & Panning, Citation2019a; Ripoll Servent & Panning, Citation2019b). In spite of this, the content analysis reveals the irrelevance of the cordon sanitaire when it comes to excluding far-right and populist voices. As observed by Akkerman and Rooduijn (Citation2015), the cordon sanitaire has become more an issue of tradition than an actual tool to exclude radical ideologies. In line with McDonnell and Werner (Citation2018), it shows that some parties choose to sit in the soft-Eurosceptic ECR to build a more respectable reputation and to have better chances to influence outputs, but their ideology is as radical as parties sitting in the ENF and the EFDD. Similarly, the cordon sanitaire is not effective when Eurosceptic and extreme voices come from inside mainstream groups. As seen in the case of the Qualifications Regulation, the EPP introduced many amendments that parroted the positions of the more radical groups – most of them authored by Central and Eastern European MEPs coming from Eurosceptic populist parties. This questions the use of the cordon sanitaire as a tool to deep-freeze non-mainstream ideologies and might actually help to legitimise the anti-elitist claims of hard Eurosceptics like the current Identity and Democracy (ID) group.

This brings us back to the issue of size – mainstream groups often did not engage with Eurosceptics when they could count on an oversized majority or when Eurosceptics were seen as not having a value-added for an even broader majority (for instance, if their positions were seen as lying outside the zone of respectability). When mainstream groups were internally divided, they tended to collaborate more closely with soft-Eurosceptic groups and include them in the process of coalition formation. In turn, the limited resources of Eurosceptic groups forced them to choose their battles and think carefully about which type of impact they wanted to have (e.g., voicing their rejection by criticizing or blocking vs influencing outputs by participating in the process) and where they might maximize this impact. Their disengagement, therefore, might hide a wide array of reasons: inability to influence despite trying, unwillingness to participate or channelling resources to other files. These motivations might be easier to ascertain in the ninth European Parliament, where the ID group is the fourth largest group and might have more resources to impose its wishes if so desired.

The shift in the EP’s balance of power might also have consequences for inter-institutional relations. The analysis of the amendments shows how the structural constraints of bicameralism successfully counteracted polarizing trends in the EP: when positions became too extreme, the chances of the EP to influence the outcomes of trilogues decreased dramatically. The bicameral system inherent in the co-decision procedure biased thus towards a centre-right majority situated in proximity to the Council position. Therefore, even if the EP managed to build a left-wing majority, the amendments proposed by the liberals and the EPP had a better chance of survival than those of the Greens and GUE/NGL. This shows the difficulty in introducing major changes and shifting policy paradigms away from the preferences of member states. It has important consequences for the current legislative period: with non-mainstream groups playing a more important role in the EP’s life and an increasing polarization inside Council, we can expect EU policy-making to become more politicized. This might translate into centre-right parties parroting and collaborating more closely with non-mainstream parties – and, hence, to policy outputs situated closer to the Traditional-Authoritarian-Nationalist end of the GAL/TAN cleavage and the anti-EU integration positions supported by most of them. Alternatively, it might accentuate inter-institutional conflicts and the perception that intergovernmentalist modes of policy-making are the only alternative to deadlock.

Supplemental Appendix

Download MS Word (23.5 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the editors and authors of this special issue as well as the participants at the research seminar of the Governance team at Science Po Grenoble and the workshop on Eurosceptic Contestations in EU Legislative Politics organized by the Free University in Berlin for their feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Ariadna Ripoll Servent is Assistant Professor of Political Science and European Integration at the University of Bamberg. She is also Visiting Professor at the College of Europe in Bruges and Jean Monnet Fellow/Research Associate at the European University Institute.

Lara Panning is a Research Fellow on the project “Democratic Legitimacy in the EU: Inside the ‘Black Box’ of Informal Trilogues” and a PhD candidate at the University of Bamberg.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akkerman, T., & Rooduijn, M. (2015). Pariahs or partners? Inclusion and exclusion of radical right parties and the effects on their policy positions. Political Studies, 63(5), 1140–1157. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12146

- Asylum Information Database. (2015). Not there yet. An NGO Perspective on Challenges to a Fair and Effective Common European Asylum System. Retrieved January 2020 from http://www.asylumineurope.org/annual-report-20122013.

- Bale, T. (2008). Turning round the telescope. Centre-right parties and immigration and integration policy in Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 15(3), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760701847341

- Baller, I. (2017). Specialists, party members, or national representatives: Patterns in co-sponsorship of amendments in the European Parliament. European Union Politics, 18(3), 469–490. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116517712049

- Bjerkem, J. (2016). The Norwegian progress party: An established populist party. European View, 15(2), 233–243. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12290-016-0404-8

- Blumenau, J., & Lauderdale, B. E. (2018). Never let a good crisis go to waste: Agenda setting and legislative voting in response to the EU crisis. The Journal of Politics, 80(2), 462–478. https://doi.org/10.1086/694543

- Brack, N. (2017). Opposing Europe in the European Parliament: Rebels and Radicals in the Chamber. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Costello, R. (2011). Does bicameralism promote stability? Inter-institutional relations and coalition formation in the European Parliament. West European Politics, 34(1), 122–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2011.523548

- Costello, R., & Thomson, R. (2011). The nexus of bicameralism: Rapporteurs’ impact on decision outcomes in the European Union. European Union Politics, 12(3), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116511410087

- Costello, R., & Thomson, R. (2013). The distribution of power among EU institutions: Who wins under codecision and why? Journal of European Public Policy, 20(7), 1025–1039. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.795393

- Delreux, T., & Laloux, T. (2018). Concluding early agreements in the EU: A double principal-agent analysis of trilogue negotiations. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(2), 300–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12633

- Downs, W. M. (2001). Pariahs in their midst: Belgian and Norwegian parties react to extremist threats. West European Politics, 24(3), 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380108425451

- European Parliamentary Research Service. (2018). Circular economy package: Four legislative proposals on waste. Retrieved January 2020 from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_BRI(2018)625108.

- Finke, D. (2012). Proposal stage coalition-building in the European Parliament. European Union Politics, 13(4), 487–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116512447013

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2016). More integration, less federation: The European integration of core state powers. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(1), 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1055782

- Hagemann, S., & Høyland, B. (2010). Bicameral politics in the European Union. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 48(4), 811–833. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02075.x

- Hix, S., & Høyland, B. (2013). Empowerment of the European Parliament. Annual Review of Political Science, 16(1), 171–189. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-032311-110735

- Hix, S., Noury, A., & Roland, G. (2007). Democratic Politics in the European Parliament. Cambridge University Press.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2009). A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000409

- Judge, D., & Earnshaw, D. (2011). “Relais actors” and co-decision first reading agreements in the European Parliament: The case of the advanced therapies regulation. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(1), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.520877

- Kreppel, A. (2018). Bicameralism and the balance of power in EU legislative politics. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 24(1), 11–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2018.1444623

- Louwerse, T., & Otjes, S. (2019). How populists wage opposition: Parliamentary opposition behaviour and populism in Netherlands. Political Studies, 67(2), 479–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321718774717

- McDonnell, D., & Werner, A. (2018). Respectable radicals: Why some radical right parties in the European Parliament forsake policy congruence. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(5), 747–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1298659

- Meguid, B. M. (2005). Competition between unequals: The role of mainstream party strategy in niche party success. American Political Science Review, 99(3), 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055405051701

- Meijers, M. J. (2017). Contagious Euroscepticism: The impact of Eurosceptic support on mainstream party positions on European integration. Party Politics, 23(4), 413–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815601787

- Minkenberg, M. (2001). The radical right in public office: Agenda-setting and policy effects. West European Politics, 24(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380108425462

- Pauwels, T. (2011). Explaining the strange decline of the populist radical right Vlaams Belang in Belgium: The impact of permanent opposition. Acta Politica, 46(1), 60–82. https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2010.17

- Ripoll Servent, A. (2018). The European Parliament. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ripoll Servent, A. (2019a). Failing under the ‘shadow of hierarchy’: Explaining the role of the European Parliament in the EU’s ‘asylum crisis’. Journal of European Integration, 41(3), 293–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1599368

- Ripoll Servent, A. (2019b). The European Parliament after the 2019 elections: Testing the Boundaries of the 'cordon sanitaire'. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 15(4), 331–342. https://doi.org/10.30950/jcer.v15i4.1121

- Ripoll Servent, A., & Panning, L. (2019a). Eurosceptics in trilogue settings: Interest formation and contestation in the European Parliament. West European Politics, 42(4), 755–775. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1575639

- Ripoll Servent, A., & Panning, L. (2019b). Preparatory bodies as mediators of political conflict in trilogues: The European Parliament’s shadows meetings. Politics and Governance, 7(3), 303–315. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v7i3.2197

- Ripoll Servent, A., & Trauner, F. (2014). Do supranational EU institutions make a difference? EU asylum law before and after ‘communitarization’. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(8), 1142–1162. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.906905

- Rose, R., & Borz, G. (2013). Aggregation and representation in European Parliament party groups. West European Politics, 36(3), 474–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.753706

- Thomson, R., Stokman, F. N., Achen, C. H., & König, T. (Eds.). (2006). The European Union decides. Cambridge University Press.

- Trauner, F., & Ripoll Servent, A. (2016). The communitarization of the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice: Why institutional change does not translate into policy change. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 54(6), 1417–1432. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12397

- van Spanje, J., & Graaf, N. D. (2018). How established parties reduce other parties’ electoral support: The strategy of parroting the pariah. West European Politics, 41(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1332328

- van Spanje, J., & van der Brug, W. (2007). The party as pariah: The exclusion of anti-immigration parties and its effect on their ideological positions. West European Politics, 30(5), 1022–1040. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380701617431

- Whitaker, R., & Lynch, P. (2014). Understanding the formation and actions of Eurosceptic groups in the European Parliament: Pragmatism, principles and publicity. Government and Opposition, 49(2), 232–263. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2013.40

- Yordanova, N. (2013). Organising the European Parliament: The Role of Committees and Their Legislative Influence. ECPR Press.