ABSTRACT

There is a broad consensus that the EU has great sources of power but little agreement on how and when this power is actively leveraged to shape global market regulation. Scholars have noted a widespread fragmentation and called for studies that cover multiple cases and account for how contextual factors influence strategic aims. This article responds to these calls by conceptualizing ‘regime vetting’ as a technique used by the European Union to reach beyond its borders in various sectors. By coining this term, the article enables exploration of a form of active and de-centred power projection that leverages the EU’s main sources of power. The article also offers a typology of four different types of regime vetting and propositions on how internal and external contextual factors systematically shape the strategic uses of regime vetting, thereby contributing to the theoretical discussion on how ‘context matters’ in shaping EU external action.

Introduction

For decades, leading figures in the European Union (EU) have emphasized its ability to project external power by leveraging its large internal market, and its aspiration to help lead the shaping of global market regulation (Damro, Citation2012). Many scholars have scrutinized the underpinnings of these grand ambitions by examining the sources, expressions and impacts of EU external power in the regulatory field (Bach & Newman, Citation2007; Bradford, Citation2020; Damro, Citation2012, Citation2015; Drezner, Citation2008; Lavenex, Citation2014; Müller et al., Citation2014; Vogel, Citation2012; Young, Citation2015a; Zeitlin, Citation2015). There is a broad consensus that the EU has great sources of power – a large internal market, sophisticated regulatory capacity and stringent market rules – and a growing understanding of the different ways in which the EU interacts with its external regulatory environment. However, the understanding of how and when the EU leverages its internal sources of power to actively influence third country regimes remains incomplete. Scholars have noted widespread fragmentation and compartmentalization, and called for studies that go beyond single or closely related cases, and take account of how variations in context help to shape EU-global interactions (Müller et al., Citation2014; Young, Citation2015a).

This article responds to these calls by conceptualizing a specific technique used by the EU in a wide range of sectors to actively project external power in the regulatory field. Put simply, this technique – which I dub regime vetting – implies that the EU systematically assesses third countries’ regulatory performance in a particular sector and, based on this assessment, either facilitates or restricts their market access in that sector. The main aim of this article is to introduce regime vetting as a new concept and demonstrate its significance and utility for research on the EU as a global regulator. I thus define regime vetting to show that it is tightly linked to the EU’s main sources of power and distinct with regard to other techniques in the EU’s power repertoire. I also identify four distinct types of regime vetting and demonstrate, based on a host of empirical examples, how these are used by the EU.

Regime vetting is distinct from other means of actively reaching beyond borders, such as centrally managed ‘foreign policy’, soft ‘functionalist extension’ (Lavenex, Citation2014) or the automatic ‘Brussels effect’ (Bradford, Citation2020), as it relies on de-centred monitoring systems, generates significant economic incentives based on market access and serves to actively co-opt third country regulators. These features make the technique particularly relevant in markets where controls at the border are impossible or impractical, requiring the EU to reach beyond its borders to drive specific changes in third country regulatory regimes. The various examples in this article demonstrate how the EU projects significant external power through regime vetting when it comes to ensuring the sustainable use of natural resources, such as fish and forests, and to encourage responsible behaviours in digital and financial markets. When effectively applied, regime vetting eases the tension between free trade and stringent EU policies in these areas by ensuring that trading partners ‘generally satisfy or conform to’ its regulatory policies (Damro, Citation2012, p. 690).

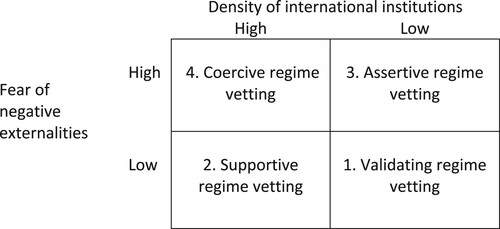

This conceptualization of regime vetting allows for a nuanced understanding of a power repertoire that has been only partially described and explained by previous research. A main contribution is the introduction and examination of the term ‘coercive regime vetting’ to capture how the EU leverages market access as a stick in relation to third countries, as it screens external jurisdictions in a particular sector and restricts the market access of those that are considered to be particularly poor performers. The conceptualization of this type in turn helps to bring out the specific meaning of other practices, some of which have been extensively studied by previous research. Most notably, the term ‘assertive regime vetting’ is introduced to capture how the EU facilitates market access for jurisdictions seen as equivalent to the EU’s in certain key regards (Newman & Posner, Citation2015). In still other cases, regime vetting is ‘supportive’, as the EU actively helps third countries to develop regulatory performance, or ‘validating’, as it aims simply to facilitate trade with major partners with little intention of driving regulatory change. By bringing together these various practices, which were not previously perceived to be part of a coherent technique, under the broad category of regime vetting and sorting them into distinct types, this article contributes to a better understanding of how the EU leverages its internal sources of power to project power externally in the regulatory field.

As an additional contribution, the article builds on the proposed typology to develop theoretical propositions regarding the contexts in which the EU can be expected to apply different types of regime vetting. While previous research has highlighted the importance of external contexts in shaping policy strategies in the regulatory field (Newman & Posner, Citation2015; Simmons, Citation2001), I argue that when it comes to active power projection through regime vetting, which is generally based on formalized processes enshrined in EU law, the internal context also contributes to shaping policy strategies. In line with this, it is proposed that the most powerful types of regime vetting become available to EU executive powers only in an internal context where there are significant fears about negative externalities from abroad. This theoretical proposition contributes to the debate on the role played by context in shaping external regulatory action (Müller et al., Citation2014; Young, Citation2015a), and more specifically to the question of when the EU leverages its internal sources of power to actively influence third country jurisdictions.

While based on extensive empirical material, the article stops short of offering a complete mapping of the EU’s use of regime vetting, and does not engage in testing causal mechanisms or effects. Future research can use and test the conceptual and theoretical contributions offered in this article to establish a more definitive picture of how and when the EU leverages its internal sources of power externally. Besides its obvious importance for understanding the EU’s global role, this research agenda will prepare the ground for studies on the EU’s external impact in the regulatory sphere, an impact which is considered ‘a crucial component of why [the EU] matters in international relations’ (Young, Citation2015a, p. 1235). The practical relevance of such studies is likely to increase still further in the coming years as digitalization and shortages of natural resources make global markets even more interconnected and interdependent, while the gaps in the regulatory ambitions of the regulatory great powers, such as the EU, the US and China, are likely to persist. As is discussed in the concluding section, EU leaders are considering applying regime vetting in broad and politically contentious areas, such as mitigating climate change and regulation of the use of artificial intelligence (AI), which makes an examination of the external effects of the technique an urgent task for future research.

The article is structured as follows. Having briefly described previous research on the EU’s repertoire of external powers in the regulatory field, regime vetting is defined and conceptualized. A typology is then developed and propositions regarding the causal relationships between context and type are proposed. The article concludes with a discussion on the broader relevance of the technique. An online appendix provides a more detailed description of how the definition of regime vetting applies in empirical examples.

THE EU’s repertoire of external powers in the regulatory field

There is a broad scholarly consensus that the EU can be considered a regulatory ‘great power’, based on the fact that it has significant sources of power that can be projected externally. While different scholars describe the sources of power in slightly different ways, three sources stand out (Young, Citation2015a). The most fundamental is the EU’s large domestic market, or the ‘relative size and diversity of [the] internal market’ (Drezner, Citation2008, p. 32). A second source of power is regulatory capacity, which has been defined as ‘a jurisdiction’s ability to formulate, monitor and enforce a set of market rules’ (Bach & Newman, Citation2007, p. 831). Finally, the projection of external regulatory power is relevant and effective only if the EU also has stringent internal market rules (Young, Citation2015a); that is, if there is a sufficient level of positive integration in the field.

However, scholars disagree on how and when the EU actively leverages these sources of power externally. Some examine the centrally coordinated and often coercive means used by classic foreign policy and pay particular attention to trade agreements, based on the starting point that the EU’s greatest coercive power lies in requiring parties to trade agreements to sign up to certain regulatory regimes as a condition of trade liberalization. A main finding is that while the EU often engages in such issue linkages to support multilateral regimes, it does not generally use trade agreements to export its domestic regimes and in any case does not systematically enforce the conditions (see e.g., Young, Citation2015a, Citation2015b).Footnote1 Other scholars highlight the de-centred power projection that takes place through ‘functionalist extension’ (Lavenex, Citation2014, p. 888), underpinned by ‘automatic’ market mechanisms that are often supported by informal networks of regulators (Young, Citation2015a, p. 1240). Product standards, in particular, have been seen to have a major automatic external impact through ‘the Brussels effect’ or ‘trading-up’, where firms apply EU standards externally even when they are not formally obliged to do so (Bradford, Citation2020; Vogel, Citation2012).

My contribution to this debate suggests that there is a significant and poorly understood area between powerful and centrally coordinated foreign policy and a de-centred functionalist extension of EU policy. Regime vetting is ‘de-centred‘ in the sense that power projection does not rely on broad, cross-sectoral issue linkages, and that sectoral regulators (generally a non-horizontal General Directorate of the European Commission, supported by a network of national regulatory agencies) play a major role in engagements with third countries. At the same time, it is formal and sometimes quite assertive or even coercive, as the EU actively leverages market access to convince third countries to change their domestic regimes, which makes it a poor fit with soft and informal ‘functionalist extension’.Footnote2

Previous attempts to describe the empirical practices denoted by regime vetting have highlighted the EU’s use of specific legal tools such as ‘equivalency’ clauses that condition market access on demonstration of equivalent rules in home markets (Farrell & Newman, Citation2019, p. 34; Moloney, Citation2016, p. 467; Newman & Bach, Citation2014, p. 439; Newman & Posner, Citation2015, p. 1326; Quaglia, Citation2015). Others have employed the term ‘territorial extension’ to highlight that these practices often build on internal EU legislation but do not fulfil the criteria for ‘extra-territorial’ application of EU law, as defined in the legal literature (Scott, Citation2014). This article moves beyond these previously used categories, introducing regime vetting as a distinct, broad technique that can be implemented through a variety of specific legal tools (blacklists, equivalency clauses, adequacy clauses or bilateral sectoral agreements), and that comes in different types, each associated with a specific degree of power projection and strategic aim.

Finally, the article uses the proposed typology of regime vetting to engage with the debate on how contextual factors shape when the EU leverages external power in the regulatory field (Young, Citation2015a). Previous research has noted that the EU may pursue a variety of aims (see Müller et al., Citation2014) and attempted to account for variations in policy strategies by highlighting external contextual factors (Newman & Posner, Citation2015; Simmons, Citation2001). This article argues that the use of regime vetting is shaped not only by external contextual factors, but crucially by the internal political context, which conditions the availability of the more powerful types of regime vetting.

Introducing regime vetting

Regime vetting may be less powerful than trade agreements and less common than product standards, but it is based on an unusually systematic and direct external projection of the EU’s sophisticated regulatory capacity. This makes it particularly suitable for reaching beyond the border to deal with technical but increasingly important policy challenges. It therefore has a significant place in the EU’s repertoire as a regulatory great power – and a potential global regulator.

Defining regime vetting

It is useful as a starting point to consider the customary meaning of the words ‘regime’ and ‘vetting’. Regime is here used as an abbreviation of ‘regulatory regime’, which has been defined as ‘an institutional structure and assignment of responsibilities for carrying out regulatory actions’ (May, Citation2007, p. 9). According to the Cambridge dictionary, to vet is to ‘examine something or someone carefully to make certain that they are acceptable or suitable’. Combining these definitions, the term ‘regime vetting’ is about carefully examining particular structures for carrying out regulatory actions to make certain that they are acceptable or suitable.

To add precision and meaning in the context of understanding the EU’s external regulatory power, I define regime vetting as a technique by which the EU subjects specific regulatory regimes in third countries to systematic and recurring performance assessments, while allowing assessment outcomes to influence decisions on market access in the sector covered by the regime. Each of the three elements of this definition helps to associate regime vetting with the EU’s sources of power: stringent rules, regulatory capacity and market size (Young, Citation2015a). This demonstrates the relevance of regime vetting to the study of the EU as a global regulator or, to put it more technically, establishes the concept’s ‘internal coherence’ and ‘utility’ to the field (Gerring, Citation1999).

The first element of the definition clarifies that power projection targets specific regulatory regimes rather than the overall governance regimes of third counties (e.g., democracy). Regime vetting is applied in sectors where the EU has relatively stringent internal market rules, in areas such as sustainable fishing, risk management in financial securities trading and integrity protection in data processing. This indicates that regime vetting is conditional on and draws potency from the stringency of EU internal market rules.

The second element in the definition links regime vetting to a high level of regulatory capacity, as it requires the EU’s assessments to be systematic and recurring, and to relate to the substantive performance of the regimes rather than any more easily identifiable formal feature. In most cases, the task of assessing a third country’s regulatory regime is entrusted to the European Commission, with support from EU regulatory agencies or other EU structures involving national regulatory authorities. Regime vetting is possible only if the level of regulatory capacity generated through this kind of integration or pooling of resources in the particular sector is sufficiently high to allow the EU to engage bilaterally with third countries and assess the performance of their market regimes in a systematic and recurring fashion. This is consistent with previous research, which perceives ‘regulatory capacity’ as an institutional factor that varies across sectors and time (Bach & Newman, Citation2007), and serves to activate the latent power vested in market size. As far as the EU is concerned, the development of regulatory capacity is often tightly linked to the establishment of incorporated transgovernmental networks in particular sectors (Eberlein & Newman, Citation2008).

The third element associates regime vetting with the factor that most fundamentally constitutes a regulatory ‘great power’: control over the conditions under which third parties are able to access a large domestic market (Drezner, Citation2008). This gives intuitive sense to the word ‘vet’: third countries are vetted ahead of decisions on market access. Only actors that control access to a market can apply regime vetting – and only actors with a large market can use this control to provide significant incentives to third countries. In line with Damro (Citation2012, p. 691), conditioned market access is understood as covering all the formal conditions that the EU imposes on third countries in order to allow the import or export of products, services or information – or the factors used to produce these. The particular incentives tied to regime vetting can be ‘positive’ in the sense that vetted third countries gain better (easier, less costly) access to the EU internal market, but they can also be ‘negative’, leaving market players from third counties facing more difficult or costly market access. In both cases, the magnitude of economic incentives correlates with the importance of the EU market to the third country being vetted, which means that the size of incentive provided to third countries will vary depending on market structures or patterns of economic interdependence.

Regime vetting vs other means of power projection

To demonstrate the significance of regime vetting and enhance conceptual clarity, it is useful to compare it to other techniques for external power projection in the EU’s repertoire. First and foremost, regime vetting never means the kind of heavy external power projection associated with the negotiation of comprehensive trade agreements, where the EU brings its entire economic weight to bear on a particular demand. Regime vetting only exceptionally means issue linkages that go beyond the particular sector in which the technique is being applied.Footnote3 In fact, the use of such broader issue linkages would violate the logic of the technique, which is about linking the level of regulatory performance in a particular sector to market access in that same sector.

Regime vetting can be seen as a substitute for power projection via product standards. Crucially, product standards are generally ineffective or irrelevant when it comes to regulatory problems related to services or Process and Production Methods (PPMs), which cannot easily be controlled ‘at the border’. To deal with these problems, regime vetting is more appropriate because it reaches ‘beyond the border’, co-opting third country regulators to allow direct supervision of the relevant activities. In some sectors where regime vetting is applied, such as fisheries and forestry, it is difficult to deduce by examining the product whether it has been produced in a legal and sustainable manner. In other sectors – such as data processing or derivatives trading – digital services are delivered in ways that cannot be controlled at the physical border. Regime vetting can thus be seen to fill gaps or weaknesses in international institutions, such as the WTO, which have traditionally focused on harmonizing product standards (Young & Peterson, Citation2014); but it does so on the EU’s terms, aiming to combine an open and globally integrated market with a level of regulatory stringency that ‘generally satisfies or conforms to’ the EU’s regulatory policies (Damro, Citation2012, p. 690).

Regime vetting is generally unilaterally imposed by the EU on third countries, but can at the same time be tightly associated with international agreements. As is discussed below, the EU can use regime vetting coercively, assertively or supportively to incentivise third countries to sign up or adhere to international agreements. It can also develop regime vetting practices based on sectoral bilateral agreements with third countries, and use these as a tool to support or validate specific regulatory regimes. The next section considers variations in the use of regime vetting and orders it in meaningful categories.

Four types of regime vetting

Although regime vetting has a distinct conceptual core, it comes in several different types, each of which is associated with a specific degree of active power projection and a specific strategic aim. The following typology adds to the general conceptualization provided above by specifying four types of regime vetting. The definition of each type is derived analytically from the way in which the EU leverages its sources of power; the more active and direct the leverage, the more powerful the type.Footnote4 However, to deepen the typology and enable easier empirical identification, I also identify ‘accompanying properties’ that are not part of the definition per se but still associated with most instances of the type (Gerring, Citation1999).

Coercive regime vetting

Sometimes the sole purpose of regime vetting is to make third countries do things that they do not want to do. The EU uses its sophisticated regulatory capacity to detect poor regulatory performers, request specific improvements and assess whether the requests have been satisfied. Market size is used directly and actively as a stick to incentivise compliance, as the EU threatens to restrict market access in the specific sector for all firms from the targeted countries. I label this type of highly active power projection ‘coercive regime vetting’.

Turning to its accompanying properties, coercive regime vetting generally follows a relatively institutionalized process based on three steps. First, the EU devises a methodology for systematically assessing the regulatory regimes of third countries and penalizing them by restricting market access in the sector concerned if the regimes are not compliant. Second, the EU screens a large number of countries and places those seen as particularly poor performers on so-called blacklists. The main targets are – often small and geographically peripheral – regulatory havens that seek advantages by applying lax regulatory regimes. Third, the EU systematically delists third countries as they formally commit to carry out regulatory change. Although the technique is enshrined in internal EU law, substantive assessments are generally pegged to international regulatory standards.

describes EU action in three sectors: fisheries, corporate taxation and anti-money laundering. In all three sectors, the EU has carried out broad screening exercises involving intense bilateral dialogues with long lists of third countries, and blacklisted those countries that were deemed uncooperative. As of 2020, following a number of revisions to each list, the EU had blacklisted 54 countries. As 10 of these (Barbados, Belize, Cambodia, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Sri Lanka, the Bahamas, Vanuatu, Mongolia and Tunisia) appear on two separate lists, the total number of ‘cases’ is 64. Following successive rounds of monitoring and assessment, 28 countries were delisted by the EU. Five of these were later found not to have lived up to their commitments and therefore relisted.

Table 1. Examples of coercive regime vetting.

Assertive regime vetting

A second type of regime vetting is best described as ‘assertive’, reflecting a confident ambition to defend the EU’s regulatory choices and to drive international convergence without necessarily seeking to coerce any particular third country. The EU uses market access primarily as a carrot, as it gives better market access to countries deemed to meet the specific regulatory standards enshrined in EU law. Regulatory capacity is used to determine whether the criteria have been fulfilled and remain fulfilled.

Table 2. Summary of the main criteria for identifying types of regime vetting.

Assertive regime vetting generally follows an institutionalized process characterized by three steps. First, the EU adds ‘equivalency’ or ‘adequacy’ clauses to its legislation, delegating power to the European Commission (generally supported by an EU agency) to facilitate the market access of countries that meet defined performance criteria in a particular sector. Second, the Commission carries out performance assessments, targeting primarily large third countries that are seen as important standard-setters and major trading partners. Third, the EU monitors countries that have been granted positive decisions, while explicitly reserving the right to unilaterally adjust or withdraw its decision at any time. Any major revision of regulatory regimes in the EU or these third countries triggers a renewed assessment.

As demonstrated in the appendix, the EU has made at least 288 positive equivalency or adequacy assessments in sectors relating to digitalized services, granting simplified market access to the EU to 37 countries. Half of these decisions target eight large powers and standards setters: Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Japan, Singapore, South Korea and the US. In its decisions, the Commission systematically and explicitly commits itself to ‘continuous’, ‘regular’ or ‘ongoing’ monitoring and reserves the right to unilaterally withdraw or adjust its decision if it judges that the criteria specified in EU legislation no longer apply. On numerous occasions, the EU has either withdrawn positive vetting decisions or allowed them to expire, for instance in areas such as audit, credit rating agencies, securities trading and data privacy.Footnote5 The European Commission judges equivalence clauses in the financial services sector to be ‘pivotal to promoting regulatory convergence around international standards and … major triggers for establishing or upgrading supervisory co-operation with the relevant third-country partners’ (European Commission, Citation2017, p. 5). In data privacy, it sees the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) as ‘a trust-enabler in the EU and beyond’ and expresses an aspiration that ‘like-minded countries could establish a multinational framework in this area’ based on EU values (European Commission, Citation2019, p. 12).

Supportive regime vetting

A third type of regime vetting is ‘supportive’, aiming to assist third countries in their efforts to reach international standards. Regulatory capacity is used not only to assess compliance with regulatory standards, but also to assist third countries to improve regulatory performance. EU market access is not leveraged directly as a carrot or stick, but rather constitutes a ‘penalty default mechanism’ incentivising cooperation by third country authorities and firms (Zeitlin, Citation2015, p. 349). Based on this, I consider the active power projection associated with this type to be relatively modest.

Supportive regime vetting is mainly implemented through bilateral agreements and support schemes that aim to enhance the performance of – primarily developing – third countries in a particular regulatory sector by offering, for instance, assistance through capacity building, information sharing, certification schemes and supervisory cooperation. This makes supportive regime vetting a relatively open category linked to a large literature on a ‘functionalist’, ‘territorial’ or ‘experimentalist’ extension of EU governance (Lavenex, Citation2014; Scott, Citation2014; Zeitlin, Citation2015). Recall, however, that the general criteria for regime vetting still delimits its scope to practices where third countries are subjected to systematic and recurring performance assessments, and where assessment outcomes are allowed to influence (sectoral) decisions on market access.

An illustrative example is provided by the EU Timber Regulation (EUTR), adopted in 2010, which prohibits operators from placing illegally logged timber on the EU market. To facilitate compliance, the EU offers third countries so-called Voluntary Partnership Agreements (VPAs), which are legally binding trade agreements for which the EU sets a number of requirements, such as systematic EU monitoring of counterparts’ regulatory regimes (Zeitlin & Overdevest, Citation2020, pp. 5–7). These agreements support regulatory performance in several ways, not least by offering opportunities to establish private certification schemes and allowing partner states to issue special export licences (so-called FLEGT licences). By 2020, 15 countries (primarily from sub-Saharan Africa) had agreed VPAs with the EU. Other agreements and partnerships, primarily targeting developing countries, can be found in sectors such as fisheries and aviation (see the Appendix).

Validating regime vetting

Finally, regime vetting may be ‘validating’, that is, applied without any ambition to influence external regulatory regimes, but to ensure that the third country has reached a performance level that justifies market access without additional EU control. This practice is well recognized in the literature on trade policy, where it is sometimes referred to as ‘pure equivalence’ (Young, Citation2015b, p. 1257) or, more frequently, as ‘mutual recognition’ (Newman & Posner, Citation2015). Validating regime vetting implies a low degree of active power projection, as it is based on a logic of generating mutual economic benefit rather than on the active leveraging of the EU’s sources of power to drive external change.

This type of regime vetting is generally implemented through bilateral agreements signed with major trading partners with the specific aim of reducing barriers to trade. An illustrative example is provided by agreements on mutual acceptance of the results of conformity assessment relating to specific product standards, for instance in the area of medical devices. The EU has signed mutual recognition agreements facilitating trade in medical devices with Australia, Canada, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, Switzerland and the US. For other examples of mutual recognition agreements, for instance in the veterinary sector, see Young and Peterson (Citation2014, p. 167ff).

summarizes the conceptualization carried out in this article.

Developing propositions on how the use of regime vetting is shaped by context

The typology of regime vetting raises the question of why the EU uses this technique so differently across sectors that share similar policy challenges. Why, for instance, is coercive regime vetting used to drive sustainable fisheries but not sustainable forestry? A useful starting point is the insight that ‘context matters’ (Young, Citation2015a), or that contextual factors causally influence the policy strategies used by EU actors, which in turn influences how regime vetting is used. It is a significant challenge, however, to identify which contextual factors are most relevant and how they shape policy strategies.

Previous research on regulatory great powers has predicted that policy strategies will be shaped largely by the relationship to third countries (Newman & Posner, Citation2015; Simmons, Citation2001). However, regime vetting practices are often ‘hard-wired into the design of specific legislative instruments adopted by the EU’ (Scott, Citation2014, p. 89). This makes regime vetting less ‘relational’ than many other techniques as it limits the discretion of the executive power to adapt the degree of power projection to specific third countries. It also links regime vetting relatively closely to the internal political stage. I therefore propose to consider regime vetting in two interlinked stages: one internal and one external.

The first stage is embedded in an often lengthy negotiation process in which the EU legislature (generally represented by the Council and the European Parliament) delegates power to the EU executive (generally represented by the European Commission). This process settles the type of regime vetting to be used, the main criteria to be applied and the procedures for ensuring control of executive power. Significant delegation takes place only if there is sufficient internal political pressure for external action from economic operators and national authorities (Moravcsik, Citation2018). Drawing on Simmons (Citation2001), I propose that a particularly important internal contextual factor is the extent to which EU economic operators and national authorities fear that the performance of third countries is having or will have a negative impact on the competitiveness and strength of the EU internal market through, for instance, regulatory arbitrage, rule avoidance and the creation of a non-level playing field (see also Müller et al., Citation2014, p. 1106). Fear of negative externalities will both drive and enable delegation of executive power, based on EU law. Hence, I propose that the greater the fear of negative externalities, the greater the likelihood that the European executive will be entrusted with the task of projecting significant external power.

The second stage is more externally oriented and involves the choice of countries to target and the application of performance criteria to those countries. At this stage the EU executive – and in particular the part of the executive that is in charge of regulating the particular sector – plays the main role. Following Newman and Posner (Citation2015), I propose that EU policy strategies will be shaped by the international institutional context and in particular the density of ‘international institutions’, a term that includes binding conventions and formal treaty-based bodies, as well as soft law and more or less informal bodies and networks between regulators (p. 1324).Footnote6 The executive will seek to project power in ways that align with dense international institutions, and to ‘go-it-alone’ primarily when there is no dense international institutions to which the EU can relate its action. There is a large literature on EU external power to support this external action rationale (see for instance Cremona & Scott, Citation2019).

The relationship between the two dimensions discussed here and regime vetting can be put more formally in the following propositions:

Proposition 1: The most powerful types of regime vetting – coercive and assertive types – will be applied only in contexts where there are significant fears of negative externalities from abroad.

Proposition 2: The least powerful types of regime vetting – supportive and validating types – may be applied even in contexts where there is little fear of negative externalities.

Proposition 3: When international institutions are dense, EU power projection will be closely associated with international efforts to either coerce or support third countries to follow international standards.

Proposition 4: When the density of international institutions is low, the EU will ‘go it alone’ by either assertively driving regulatory convergence among other standards setting countries or simply validating third country regimes to enable smoother trade.

illustrates these propositions, pinpointing the contexts in which different types of regime vetting are most likely to emerge. It also highlights the usefulness of the typology, as the dependent variable is expressed not only in nominal but also in ordinal terms, on a continuum of active power projection ranging from 1 (low) to 4 (high). This is arguably a significant step forward compared to frameworks that use only a nominal dependent variable and do not integrate the internal political context into the independent variables (Newman & Posner, Citation2015, p. 1325).

Empirical testing of the propositions is beyond the scope of this article and left as an important task for future research. Testing should focus, for instance, on determining whether the EU’s use of assertive regime vetting in fisheries, corporate taxation or anti-money laundering can indeed be explained by fears about negative externalities in these sectors and the presence of dense international institutions,Footnote7 or other contextual variables are more relevant. It should also examine whether the application of assertive regime vetting to financial services and data privacy is linked to fear of negative externalities, in a context where international institutions are struggling to keep pace with rapid technological change.Footnote8

Concluding discussion

This article has defined and conceptualized regime vetting as a distinct technique in the EU’s repertoire as a global regulator that is used to reconcile the desire for deep and open trade links with a wish to ensure the integrity of the EU’s internal market. Compared to concepts such as ‘functional extension’ (Lavenex, Citation2014) or the automatic ‘Brussels effect’ (Bradford, Citation2020), regime vetting implies a more active and direct leveraging of a combination of market access and regulatory capacity. Regime vetting is also different from conceptions of centralized ‘foreign policy’ (Lavenex, Citation2014), as it leverages market access sectorally and relies on de-centred regulatory capacity to engage with third countries. By bringing together a broad variety of practices – not previously perceived as forming a coherent technique – under the broad category of regime vetting, and sorting them into distinct types, this article has contributed to the understanding of how the EU leverages its internal sources of power to actively project power externally in the regulatory field.

As an additional contribution, the article has used the typology to shed light on when – or in what contexts – the EU can be expected to project power through regime vetting. In line with previous research, it has assumed that the EU’s various policy strategies are shaped by specific contextual factors. In contrast to the previous literature (Newman & Posner, Citation2015), however, this article has proposed that EU policy strategies involving regime vetting are shaped not only by external factors, but also by internal contextual factors, in particular the perception of negative externalities from abroad.

Besides testing the above propositions, future research should use the typology to map the use of regime vetting in Europe and elsewhere. Such research might reveal that the technique is an EU speciality – appearing as an external application of its acknowledged ability to strategically drive market integration (Jabko, Citation2006). It might then make sense to think about regime vetting as part of a particular EU foreign policy pursued sector by sector in areas where fragmented or diverse global regulatory regimes appear particularly threatening from a European standpoint. While perhaps regime vetting does not allow the EU to manage globalization (Jacoby & Meunier, Citation2010), it does appear relevant to the ‘restructuring’ of Europe’s external boundaries (Bartolini, Citation2005), and to managing the so-called globalization trilemma (Rodrik, Citation2011).Footnote9 In a context where it cannot be taken for granted that global market regimes will be based on liberal and democratic values, the EU could see regime vetting as a key technique for enhancing democratic and rules-based authority over increasingly important markets sectors that defy traditional regulatory techniques. To illustrate the stakes, Facebook chief Mark Zuckerberg recently warned against the spread of China’s internet regulation model, claiming that it disregards human rights and asking for ‘deeper cooperation and partnership with democratic institutions’ (Kayali et al., Citation2020).

Further effort should also go into assessing the external impact of regime vetting, as well as the effectiveness and limits of the technique. Although methodologically challenging, such research would be of great societal relevance as the European Commission is currently considering using regime vetting in broad and politically important sectors such as AI and climate change. Would it be wise to introduce an EU carbon border tax that links third countries’ market access to their performance on combating climate change (Zachmann & McWilliams, Citation2020)? Or, for that matter, would it be a good idea to apply regime vetting to cover ‘high-risk’ applications of AI, as recently proposed by the European Commission (Citation2020)? The key question arises, in both these broad and politically contentious areas: would external parties follow the EU’s lead?

Supplemental Appendix

Download MS Word (64.2 KB)Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Josefina Erikson, Anna Michalski and Jonas Tallberg, as well as the three anonymous reviewers, for helpful comments on earlier drafts. I also thank the participants at the EU seminar organized at the Department of Government, Uppsala University, 3 June 2020, and the workshop organized by the Swedish Institute for European Policy Studies (Sieps), 15 June 2020.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Johannes Jarlebring

Johannes Jarlebring is a PhD candidate at Uppsala University. He has previously served many years as a civil servant and consultant specializing in EU matters.

Notes

1 A notable exception is the neighbourhood and enlargement policies, in which the EU projects significant power based on broad, comprehensive agreements (Lavenex, Citation2014).

2 I borrow the terms ‘foreign policy’, ’functionalist extension’ and ‘de-centered’ from Lavenex (Citation2014). For Lavenex, ‘foreign policy’ relies either on direct projection of EU legal authority in relation to market operators or on cross-sectoral issue linkages that bring the EU’s entire economic weight to bear on specific demands.

3 The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (Reg. 2016/79) offers a rare example of far-reaching interlinkages, as it requires the European Commission to consider ‘rule of law, respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms [and] relevant legislation’ (art. 5.1).

4 Power projection is thus defined as the active and direct application of pressure to drive external change. The typology of regime vetting captures variations in this factor by identifying how the EU uses its regulatory capacity and market size to pursue distinct aims associated with different levels of coercive pressure. Note, however, that these indications of active power projection do not necessarily correlate directly with the level of economic incentives provided by the EU to third countries. Economic incentives based on market access depend on patterns of economic interdependence, which are generally shaped by country-specific trading relations developed through long-term market dynamics, rather than through intentional power projection.

5 As demonstrated in the appendix, there are at least 21 such examples relating to many countries and sectors. Several of these have been examined in case studies highlighting the EU’s use of adequacy and equivalence clauses to project external power (Newman & Bach, Citation2014; Newman & Posner, Citation2018; Farrell & Newman, Citation2019).

6 To conceptualize the ‘density of international institutions’, Newman and Posner (Citation2015) imagine a continuum ranging ‘from less densely institutionalized where there are few institutions that exist capable of rule-development or rule-enforcement to more densely institutionalized where there are clear rules at the global level concerning decision-making and implementation’ (p. 1325).

7 A prima facie, this seems plausible. In fisheries, unsustainable fisheries that occur outside EU territory pose direct threats to EU fishing stocks, and EU law pegs the EU’s use of regime vetting to international standards (1026/2012/EU, art. 3). In corporate taxation, where the European tax base it threatened by ‘Base Erosion and Profit Shifting’ (BEPS), the OECD plays a central role in coordinating the international regulatory agenda. In money laundering, illicit international transfers risk financing organized crime in the EU, and international efforts are coordinated by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF).

8 Again, this seems plausible. For instance, Quaglia (Citation2015) has shown how equivalence clauses were added to EU legislation in the aftermath of the 2009 financial crises, which revealed the EU’s exposure to overleveraged financial services markets in the USA.

9 Practices of regime vetting potentially constitute the building blocks of ‘Open Plurilateral Agreements’ that offer ‘better prospects for groups of countries to explore and develop their potential common interests on regulatory matters, while safeguarding core aspects of their national regulatory sovereignty’ (Hoekman & Sabel, Citation2019, p. 297).

References

- Bach, D., & Newman, A. L. (2007). The European regulatory state and global public policy: Micro-institutions, macro-influence. Journal of European Public Policy, 14(6), 827–846. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760701497659

- Bartolini, S. (2005). Restructuring Europe: Centre formation, system building, and political structuring between the nation state and the European Union. Oxford University Press.

- Bradford, A. (2020). The Brussels effect: How the European Union rules the world. Oxford University Press.

- Cremona, M., & Scott, J. (Eds.). (2019). Eu law beyond EU borders: The extraterritorial reach of EU law. Oxford University Press.

- Damro, C. (2012). Market power Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(5), 682–699. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.646779

- Damro, C. (2015). Market power Europe: Exploring a dynamic conceptual framework. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(9), 1336–1354. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1046903

- Drezner, D. W. (2008). All politics is global: Explaining international regulatory regimes. Princeton University Press.

- Eberlein, B., & Newman, A. L. (2008). Escaping the international governance dilemma? Incorporated transgovernmental networks in the European Union. Governance, 21(1), 25–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2007.00384

- European Commission. (2017). EU equivalence decisions in financial services policy: An assessment, SWD(2017) 102 final.

- European Commission. (2019). Data protection rules as a trust-enabler in the EU and beyond: Taking stock. COM(2019) 374 final.

- European Commission. (2020). On Artificial Intelligence: A European approach to excellence and trust. COM(2020) 65 final.

- Farrell, H., & Newman, A. L. (2019). Of privacy and power: The transatlantic struggle over freedom and security. Princeton University Press.

- Gerring, J. (1999). What makes a concept good? A criterial framework for understanding concept formation in the social sciences. Polity, 31(3), 357–393. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3235246

- Hoekman, B., & Sabel, C. (2019). Open plurilateral agreements, international regulatory cooperation and the WTO. Global Policy, 10(3), 297–312. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12694

- Jabko, N. (2006). Playing the market: A political strategy for uniting Europe, 1985–2005. Cornell University Press.

- Jacoby, W., & Meunier, S. (2010). Europe and the management of globalization. Journal of European Public Policy, 17(3), 299–317. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501761003662107

- Laura, K., Thibault, L., & Melissa, H. (2020, May 18). Facebook’s Zuckerberg calls out Chinese internet model, Politico, (on-line).

- Lavenex, S. (2014). The power of functionalist extension: How EU rules travel. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(6), 885–903. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.910818

- May, P. J. (2007). Regulatory regimes and accountability. Regulation & Governance, 1(1), 8–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2007.00002.x

- Moloney, N. (2016). International financial governance, the EU, and Brexit: The ‘agencification’ of EU financial governance and the implications. European Business Organization Law Review, 17(4), 451–480. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40804-016-0055-x

- Moravcsik, A. (2018). Preferences, power and institutions in 21st-century Europe. Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(7), 1648–1674. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12804

- Müller, P., Kudrna, Z., & Falkner, G. (2014). EU–global interactions: Policy export, import, promotion and protection. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(8), 1102–1119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.914237

- Newman, A., & Bach, D. (2014). The European Union as hardening agent: Soft law and the diffusion of global financial regulation. Journal of European Public Policy, 21(3), 430–452. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.882968

- Newman, A. L., & Posner, E. (2015). Putting the EU in its place: Policy strategies and the global regulatory context. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(9), 1316–1335. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1046901

- Newman, A. L., & Posner, E. (2018). Voluntary disruptions: International soft law, finance, and power. Oxford University Press.

- Quaglia, L. (2015). The politics of ‘third country equivalence’ in post-crisis financial services regulation in the European Union. West European Politics, 38(1), 167–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.920984

- Rodrik, D. (2011). The globalization paradox: Democracy and the future of the world economy. WW Norton & Company.

- Scott, J. (2014). Extraterritoriality and territorial extension in EU law. American Journal of Comparative Law, 62(1), 87–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5131/AJCL.2013.0009

- Simmons, B. A. (2001). The international politics of harmonization: The case of capital market regulation. International Organization, 55(3), 589–620. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/00208180152507560

- Vogel, D. (2012). The politics of precaution: Regulating health, safety, and environmental risks in Europe and the United States. Princeton University Press.

- Young, A. R. (2015a). The European Union as a global regulator? Context and comparison. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(9), 1233–1252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1046902

- Young, A. R. (2015b). Liberalizing trade, not exporting rules: The limits to regulatory co-ordination in the EU's ‘new generation’ preferential trade agreements. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(9), 1253–1275. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1046900

- Young, A. R., & Peterson, J. (2014). Parochial global Europe: Twenty-first century trade politics. Oxford University Press.

- Zachmann, G., & McWilliams, B. (2020). A European carbon border tax: Much pain, little gain. Policy Contribution, 5.

- Zeitlin, J. (Ed.). (2015). Extending experimentalist governance? The European Union and transnational regulation. Oxford University Press.

- Zeitlin, J., & Overdevest, C. (2020). Experimentalist interactions: Joining up the transnational timber legality regime. Regulation & Governance, 1–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12350