ABSTRACT

The crises of the European Union and the geopolitical shifts in its international environment have generated a backlash against the post-Cold War ‘debordering’ of European integration. Whereas integration theories focus almost exclusively on the EU’s internal boundaries and developments, this framework paper conceptualizes and theorizes integration as a process of internal debordering and external rebordering. It sketches the history of European integration in a bordering perspective and proposes general assumptions about the EU’s bordering process. Accordingly, rebordering pressures result from widening boundary gaps at the EU’s external borders, exogenous shocks to cross-border transactions, growing community deficits of debordering, and their politicization. Whether external rebordering succeeds and how it interacts with internal boundary formation, depends on EU-level boundary negotiations and the relative costs and benefits of external vs. internal rebordering.

Introduction

In the past decade, European integration has faced a series of challenges. The enduring global recession and the mounting Greek balance-of-payment problem signalled the start of the Euro crisis. As soon as the Eurozone narrowly averted ‘Grexit’ in dramatic negotiations in July 2015, migration flows across the Aegean Sea spiralled out of control and brought the Schengen/Dublin free-movement and asylum regimes to the brink of collapse. Fuelled by concerns about immigration, the 2016 UK referendum led to the first exit of a member state. A few months later, the election of Donald Trump spelt uncertainty about the future of the Western international order and transatlantic relationship, in which European integration is embedded. In the same period, autocratization in the EU’s east and south, together with Russian and Turkish military assertiveness, has curbed the EU post-Cold War project of gradually integrating neighbouring countries. It has turned the European neighbourhood from the envisaged ‘ring of friends’ (former Commission President Romano Prodi) into a ‘ring of fire’. The Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated and reinforced these geopolitical faults and the EU’s internal disparities and tensions.

Strikingly, all these challenges originated at, or put at stake, the external borders of the EU. They demonstrate how much European integration is affected not only by political developments in its member states, but also by its international environment. Moreover, how outside developments affect the EU depends on the configuration of its external borders. In the post-Cold War period, the EU has experienced pervasive ‘debordering’: a rapid expansion and opening of its boundaries. The EU not only expanded its membership, but also cast a net of graded association arrangements over European non-members. It not only removed internal boundaries by establishing the single market, a common currency and the Schengen free-travel zone, but also lowered external barriers to global trade and capital mobility. This debordering moved European integration into contested spheres of influence (especially with Russia). It also increased the EU’s exposure to external developments such as the US mortgage crisis and cross-border capital flows, which sparked the Eurozone crisis, and the repression and civil wars in Northern Africa and the Middle East, which triggered the migration crisis. And EU debordering weakened traditional competencies of the nation-state (such as physical border controls, capital controls or currency devaluation) without establishing supranational organizations with the capacity to compensate the loss of national control (Copelovitch et al., Citation2016; Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2014; Scipioni, Citation2018; Trauner, Citation2016). Finally, the exposure to globalization produced economic and cultural winners and losers; it thereby deepened a transnational, integration-demarcation cleavage in European politics and boosted the electoral fortunes of Eurosceptic parties (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009, Citation2018; Kriesi et al., Citation2006).

In light of the political attention and contestation that the external borders of the EU attract, it is remarkable how marginally they feature in the major theories of integration. These theories generally focus on the opening and removal of internal boundaries between the member states, the formation and growth of a new supranational centre promoting and enforcing this openness, and the internal institutional and political dynamics of integration. External boundary formation (e.g., through external tariffs or asylum rules) mainly appears as a side effect of internal EU policies (e.g., the creation of a customs union or a free-travel area) – not as a driver of or constraint on integration in its own right.

Whereas exogenous, international factors were prominent in traditional intergovernmentalist accounts of European integration (Hoffmann, Citation1966), liberal intergovernmentalism focuses on internal economic integration. It assumes that integration preferences are rooted in the domestic interests of the member states (Moravcsik, Citation1998). Neofunctionalism also focuses on favourable domestic conditions of integration (such as modernization and pluralism) and attributes integration progress to functional, political and institutional ‘spill-overs’ of earlier integration steps (Haas, Citation1968). With the minor exception of ‘geographical spillover’ (Haas, Citation1968, pp. 314–317), these spillovers are internal (but see Bergmann & Niemann, Citation2018 for a recent discussion of ‘external spillover’). Only when Haas speculated about the ‘obsolescence’ of integration theory did he bring up concerns about ‘externalization’, i.e., the increasing attractiveness of actors and regimes beyond European integration (Haas, Citation1976, p. 176; cf. Schmitter, Citation1969). Finally, postfunctionalism focuses on the domestic politicization of ‘Europe’ and its effects on the deepening of integration (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009).

In spite of occasional appeals to pay more attention to exogenous pressures and geopolitics (Hooghe & Marks, Citation2009, p. 23; Niemann, Citation2006, p. 291), theories of European integration continue to be inward looking predominantly and remain detached from existing research on the EU’s border policies. In turn, this research focuses on policy-specific developments in domains such as foreign and security policy or migration policy, but not on their implications for the general dynamics of European integration.

At least implicitly, the theory and analysis of European integration in the post-Cold War period has subscribed to the assumption that the international environment provides a benign and stable external context for the EU. The main challenges that motivated most of the recent EU literature and academic debate – such as democratic deficits, economic disparities, mass politicization, Euroscepticism and populism – are internal. The EU’s international environment featured mainly as a field of outward policy diffusion and Europeanization (e.g., Bradford, Citation2020; Schimmelfennig & Sedelmeier, Citation2005), not as a source of change for European integration itself.

As the post-Cold War international order dissolves and transforms, however, it is becoming increasingly difficult to explain European integration and politics without putting its international environment and external borders centre stage. In addition, it is becoming increasingly important to understand how the EU responds to the external and internal backlash against its post-Cold War debordering.

The crises of the EU have made the study of European disintegration fashionable (Vollaard, Citation2018; Webber, Citation2018). In the disintegration scenario, externally induced pressures overburden common institutions and lead to ‘internal rebordering’: the resurrection of barriers between member states and their exit from common policies or the EU altogether. The Grexit threat during the Eurozone crisis, the closing of internal Schengen borders during the migration and Corona crises, and the withdrawal of the UK exemplify this scenario. Moreover, it would leave the member states divided and vulnerable in their relations with a conflict-ridden and inimical international environment. Persistent divisions over policy towards major external powers, weak border control capacities, and a cumbersome foreign-policy decision-making process point in this direction.

Alternatively, however, the EU may cope with the backlash by switching to external rather than internal rebordering. In this scenario, the progressive closure and control of the EU’s external boundaries would allow the EU to maintain the openness of its internal borders, consolidate politically and develop the capacity to assert itself in a changing geopolitical environment. There are, indeed, signs of such closure, control and consolidation tendencies. EU enlargement has all but stopped. In the Brexit negotiations, the EU has preserved a rigid and united stance on protecting the integrity of its internal market and regulatory level playing field. Outside the UK, Eurosceptic parties’ calls for exit have become subdued. The migration crisis has triggered a restrictive asylum policy and an unprecedented investment in the control of the EU’s external borders. Whether external rebordering will succeed and help consolidate the EU, or disintegration tendencies will prevail, is an eminent political question for the future of European integration.

Any success in consolidating integration through external rebordering, however, raises further questions about its economic, political and normative price. These concerns often come under the label ‘Fortress Europe’. Economic protectionism, the disappointment of accession hopefuls and the violation of legal and moral obligations vis-à-vis migrants are just some of the implications of rebordering.

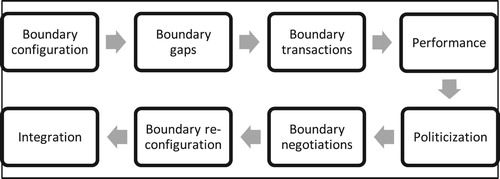

This special issue explores the rebordering of the EU theoretically and empirically covering a variety of actors, issues and processes. In this introductory article, I present a conceptual, historical and analytical framework for the study of bordering in European integration. This framework seeks to bring the external boundaries – and their interaction with internal boundaries – systematically into the explanation of European integration. To this end, it defines boundaries as functional and territorial institutions regulating the movement of persons and products between organizations. It further distinguishes four broad constellations of internal and external bordering processes and outcomes: effective, dilutive and defensive integration as well as disintegration. Subsequently, I sketch a ‘bordering history’ of European integration. In this perspective, the initially limited but effective early integration process was followed in the post-Cold War period by a dilutive integration trajectory. Finally, I outline an analytical approach to rebordering. It starts with a boundary configuration that comes under pressure because of widening ‘boundary gaps’ between the EU and its international environment, shocks to boundary transactions and the accumulation of community deficits of debordering. These deficits lead to boundary politicization and re-negotiation. The outcome of boundary negotiations depends on the (issue-specific) costs and institutional hurdles of internal and external rebordering and on the relative bargaining power of EU and external actors.

Boundaries, bordering and integration

This section defines boundaries and bordering and conceptualizes their relationship to integration.Footnote1 It starts from an institutional, territorial, functional and relational definition of boundaries. Boundaries consist of rules regulating the movement (entries and exits) of products and persons between territorial organizations. Boundaries are geographically localizable but not necessarily physical. As functional institutions, they differ by the type of transactions they regulate. Accordingly, the boundary rules as well as their geographical location vary across functions. Conventionally, the literature distinguishes economic, cultural, political and military boundaries in line with the respective functional subsystems of territorial social systems. The economic boundary regulates the movement of goods, services, capital and labour, and the cultural boundary the exchange of messages and ideas. The political boundary sets restrictions on legal competences and political rights to control the scope of authoritative decisions and political influence. The military boundary regulates the entry and exit of coercive instruments (weapons) and agents (armies or criminals) (Bartolini, Citation2005, pp. 13–20; Rokkan, Citation1974, p. 42). Finally, boundaries are relational: they not only separate but also relate territories to each other. Irrespective of the regulatory barriers boundaries create, adjacent territories may be more or less similar, e.g., in culture or political regime. In other words, boundaries create ‘boundary gaps’.

The institutional configuration of each boundary consists in a combination of closure and control. Closure determines how much the rules for boundary transactions limit exits and entries. Open borders allow for unrestricted movement; closed borders create insurmountable barriers. Control refers to the legal competence and the resource-dependent capacity to enforce these rules. In the EU multi-level system, control is also about the relative competencies and capacities of member states and supranational actors. Closure and control are independent of each other in principle. Rigid border rules may be weakly enforced and vice versa.

In addition, boundary congruence refers to the overlap of functional boundaries with regard to their location, closure and control. Congruence is high if different functional boundaries delimit the same territories, if they are equally open or closed, and if the centre possesses similar control competences and resources to police them. In sum, a boundary configuration consists in the constellation of closure, control and congruence across the economic, cultural, political and military boundaries of an organization.

‘Bordering’ encompasses all activities of boundary making and management. It can take the directions of ‘debordering’ and ‘rebordering’. Debordering covers all activities that expand and open up boundaries, reduce (central) boundary control and decrease boundary congruence; conversely, rebordering refers to all activities of boundary closure or retrenchment as well as increases in (central) boundary control and in boundary congruence (Popescu, Citation2012, pp. 69–77).Footnote2

In a sociological, systems-theoretical perspective, integration has two faces: the internal cohesiveness of the units and sub-systems of a system and the external demarcation of the system from its environment and other systems.Footnote3 Put in ‘bordering’ language, integration concerns both external and internal boundaries; and successful integration comprises the debordering of internal boundaries, on the one hand, and the rebordering of external boundaries, on the other. In this perspective, concepts and theories of European integration that focus exclusively on internal cohesiveness and boundaries between member states are incomplete by definition. A comprehensive analysis of European integration requires describing and explaining the development of both its internal and external boundaries – and their interaction. Moreover, if integration depends on the combination of internal debordering with external rebordering, the traditional one-dimensional conceptualizations of ‘more vs. less’ integration and ‘integration vs. disintegration’ are too simple.

Rather, the distinction of debordering and rebordering and of internal and external boundaries yields four types or trajectories of integration (). The combination of internal debordering with external rebordering characterizes effective integration. It jointly realizes the two dimensions of successful integration. Against this benchmark, the other integration trajectories are ‘defective’. The combination of internal and external debordering produces a process of dilutive integration. While it strengthens internal cohesion among the member states, it fails to differentiate them from the international environment. By contrast, the combination of internal and external rebordering generates a trajectory of defensive integration, in which the member states establish rigid joint external borders and powerful common control capacities, but maintain or rebuild their internal barriers. Both defensive and dilutive integration exhibit one but lack the other constitutive bordering process of effective integration. Finally, disintegration is reserved for the combination of internal rebordering and external debordering. It consists in the resurrection of internal borders between the member states, the strengthening of national boundary control capacities at the expense of supranational actors, and the dismantling of common external borders and control capacities. It is important to note that these types of integration can vary across functions – say, dilutive integration in trade and defensive integration in migration policy – and over time.

Table 1. Bordering processes and integration trajectories.

This conceptual framework allows for a more refined analysis of European integration. The literature has generally operated within a one-dimensional continuum of integration, discussing, for instance, whether and why the crises of European integration have produced internal integration (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2018; Jones et al., Citation2016; Schimmelfennig, Citation2018). Yet the options increase if external boundaries are taken into consideration. If the EU decides for more internal integration in its crisis response, it depends on the external bordering policy whether the overall integration trajectory is dilutive or effective. If internal integration does not change, external rebordering may still result in a more effective integration. Even in the case of internal disintegration (rebordering), external rebordering could still produce defensive integration.

The conceptualization of integration as bordering generates multiple questions for research. How has the EU’s external boundary configuration – the closure, control and congruence of external borders – developed and changed over time? Which patterns of bordering do we observe in response to the EU’s crises and the changes in its international environment? And which are the drivers and conditions of bordering?

Bordering in European integration: a historical sketch

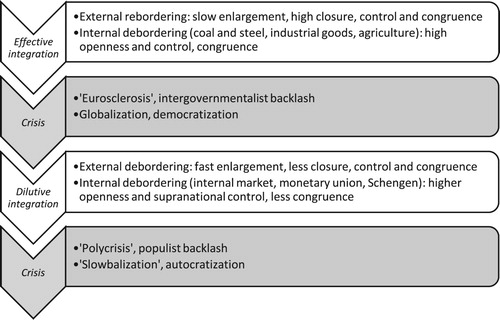

Here, I propose a stylized sketch of the development of European integration in the perspective of bordering. It consists of two phases, distinguished by the main patterns of bordering and their crises (). European integration started with a period of effective but limited integration in the 1960s, which – due to an intergovernmentalist backlash and economic crisis – ran into stagnation, however. Carried by globalization, the end of the Cold War and democratization, the second period, beginning roughly in the mid-1980s, featured a combination of internal and external debordering (cf. Bartolini, Citation2005). This dilutive integration has come under pressure in the ‘polycrisis’ of the EU, the populist backlash it created, and the concomitant de-globalization and autocratization processes in its international environment. Whether these rebordering pressures will mean a return to effective integration rather than a shift to defensive integration or even disintegration is the core challenge of the current period.

Effective but limited integration

In the early phase of integration, the three main projects were the Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), the Customs Union (CU) and the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). These projects removed internal economic boundaries and created a common market for coal and steel products and, later, industrial and agricultural goods. At the same time, a significant common external economic border protected these integrated policies. The ECSC could set rates for external duties, fix prices in relation to the export market and supervise the granting of import and export licenses. The CU established a common external tariff. The CAP was designed to protect farmers through market and price support and shielded them from global competition through access restrictions, high duties and export subsidies. All three policies were designed as supranational policies, with exclusive competences of the Union and powerful supranational agencies. In addition, they were well-funded. The ECSC had the power to collect levies, the CU created revenue from customs duties and the CAP received major funding from the EU budget.

Moreover, the EU was slow to open up to non-member states. Northern enlargement took several attempts – and overcoming two French vetoes. There was no treaty-based differentiation among member states (apart from transitional arrangements from the accession treaties). Externally, the association of Greece and Turkey developed haltingly and the most advanced form of non-member integration were free-trade agreements for industrial goods with EFTA countries. Boundary incongruence was thus low. In sum, whereas integration was limited to a few economic policies, it was effective in its combination of internal debordering and external rebordering.

Yet, further supranational integration envisaged in the Treaties of Rome provoked an ‘intergovernmentalist backlash’ in the ‘empty chair’ crisis of 1965/66. Moreover, the end of the post-World War II economic upswing, the oil shocks and ‘stagflation’ combined to produce the ‘Eurosclerosis’ of the 1970s. In this period, new integration projects – such as European Political Cooperation, the TREVI police cooperation and the European Monetary System – remained at the level of intergovernmental cooperation.

A combination of external transformation and internal convergence generated the prerequisites for a re-orientation of bordering. The new phase in European integration started in an international environment characterized by the incipient ‘second wave of globalization’ and ‘third wave of democratization’. Both waves created outside opportunities and pressures for external debordering. Globalization heightened international competition from the US and Japan, but also opened new markets and supply chains for European economies. Democratization in Southern and Eastern Europe and the end of the Cold War raised interest in and opportunities for enlargement. In addition, the convergence of economic preferences among the major member states since the early 1980s facilitated a common liberal, market-opening agenda to respond to these challenges (Ludlow, Citation2006; Moravcsik, Citation1991).

Dynamic but dilutive integration

The ‘dilutive integration’ phase of European integration has seen a major expansion of the EU’s policy scope, supranational competencies and membership. At the same time, the EU has become more open towards the globalizing world economy and its neighbourhood as well as more externally and internally differentiated. In the control dimension, dilutive integration consisted in an imbalance, constraining nation-states without empowering and resourcing European institutions in similar measure. Supranational actors were strong in creating and defending open boundaries, but member states were reluctant to equip them with independent or sizable fiscal and coercive capacities.

Internal debordering intensified with the Single Market programme, monetary union and the Schengen agreement to abolish controls at the internal borders. In contrast to phase 1, however, external rebordering did not balance internal debordering. Rather, the development of the internal market went hand in hand with the deepening of global trade liberalization and trade regulation that culminated in the far-reaching reforms of the GATT and the creation of the WTO in the mid-1990s. Specifically, WTO influence led the EU to lower the external boundaries of the CAP (Daugbjerg, Citation2017).

External closure remained significantly higher for the movement of persons. Yet whereas the EU removed internal passport controls and physical border infrastructures, it failed to build centralized regulatory competences and capacities for controlling the external boundaries. The control of the external Schengen borders and the handling of migrants and refugees arriving from outside of Schengen remained with the member states and continued to depend strongly on their national rules and capacities.

Enlargement and differentiation added to the external debordering thrust. Democratization in Southern Europe removed the most important hurdle for the southern enlargement of the EU; at a larger scale, this process repeated itself in the 1990s and 2000s in Central and Eastern Europe. In northern Europe, the combination of the internal market programme and the end of the Cold War incentivized and enabled most countries to join the EU. These processes resulted in the continent-wide expansion of the EU to 28 members in 2013.

For the remaining European countries, the EU has engaged in broad-based and increasingly varied forms of external differentiation, opening up its policy regimes and institutions to the selective market access and policy participation of non-member states. In addition, the integration of new policies in the domain of core state powers has created durable internal differentiation – above all in the Eurozone and the Schengen Area.

The recent crises of the EU are closely linked, and present a major challenge, to this dilutive boundary regime. They have also created a populist backlash against debordering. Moreover, the waves of globalization and democratization that supported dilutive integration have run their course. The ‘third wave of autocratization’ (Lührmann & Lindberg, Citation2019) has reached the external borders of the EU: from the failed ‘Arab Spring’ and Turkish competitive authoritarianism in the south via ‘stabilitocracy’ (Bieber, Citation2018) in the Western Balkans to hybrid regimes in the Eastern Partnership countries and, finally, Russian autocracy in the east. For one, autocratization is a major obstacle to EU enlargement, which requires new member states to be (fairly) consolidated democracies. Moreover, an autocratic Russia determined to prevent the EU from making inroads into its claimed geopolitical sphere impedes integration in the Eastern neighbourhood. Finally, in the aftermath of the Great Recession, and reinforced by the trade policy of the Trump administration as well as the Covid-19 pandemic, globalization has turned to ‘slowbalization’, decreasing the share of trade and foreign direct investment in world GDP and regionalizing economic exchange.Footnote4

In addition to these broad trends, specific exogenous shocks have exposed the deficits of weak supranational control in the EU’s dilutive integration. First, in the case of the subprime mortgage crisis in the US, which engulfed European banks first and governments next, the Eurozone did not have effective European rules and mechanisms for the rescue or resolution of systemically relevant banks. It lacked a ‘fiscal backstop’ substituting for private capital retreating through open financial boundaries. Second, the Russian intervention in Eastern Ukraine and its annexation of Crimea demonstrated that the EU lacks the military competences and capacities to support member states, let alone associated countries set to deepen their EU integration, against military threats and aggression. Third, in the migration crisis, the Schengen/Dublin regime was ill prepared to deal with a massive influx of refugees, as the policing of the external borders and the handling of asylum requests remained under the authority of individual member states overwhelmed by the task. Finally, dilutive integration and its crises have fuelled the ‘populist backlash’ against European integration. The issue of open and supranationally controlled borders, primarily for migration but also for trade and investment, has created a massive elite-mass gap in attitudes, shifted the main axes of political conflict, and boosted Eurosceptic populist parties (De Wilde et al., Citation2019; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2018).

The ebbing of the democratization and globalization waves in the EU’s international environment, the multiple policy crises of the EU and the populist backlash they have generated or reinforced are having a profound impact on the political development of the EU. Even though these processes are ongoing and open-ended in principle, there are strong indications that they are reversing the main thrust of European integration from external debordering to external rebordering.

In general, the openness of the EU’s external boundaries is decreasing, while the EU has initiated moves to strengthen its boundary control capacity. Enlargement has slowed down considerably. No new member state joined after Croatia in 2013, and those in accession negotiations are nowhere near an accession treaty. In the same period, the EU has focused on protecting the integrity of the internal market and strengthening regulatory alignment in return for market access in its external differentiation arrangements – not only in the Brexit process, but also in its negotiations with Switzerland.

Programmatically, terms like ‘European Strategic Autonomy’ (in the 2016 Global Strategy), von der Leyen’s pledge to lead a ‘geopolitical Commission’, the Commission’s classification of China as a ‘systemic rival’ in March 2019 and talk about ‘industrial strategy’ and ‘champions’ signal the rise of a rebordering discourse in EU policy. Operationally, PESCO and investments in the European Border and Coast Guard indicate a renewed focus on the building of external border control capacities. How consequential and effective these developments will be is an open question. Moreover, external rebordering could move the EU in a variety of directions: from dilutive integration to effective integration, defensive integration, or even disintegration.

External rebordering: an analytical framework

To analyse and explain rebordering, I propose an analytical framework (), which starts from a given institutional boundary configuration that defines the location, closure, control and congruence of the external borders of the EU. Each boundary configuration generates or marks boundary gaps between the spaces on each side of the boundary, such as wealth, religious or political regime gaps. Together, the boundary configuration and gaps enable and constrain transactions across boundaries, which affect the performance of the EU and its member states. Depending on its performance, the boundary configuration is politicized. Boundary politicization triggers European boundary negotiations, which may lead to a reconfiguration of the internal and/or external boundaries. maps this bordering process. The framework does not intend to contradict or replace existing integration theories, but recombines some of their building blocks – e.g., neofunctionalism on boundary transactions, postfunctionalism on politicization and intergovernmentalism on negotiations – in a bordering perspective.

The framework is based on the assumption that a scale-community dilemma drives the bordering process. This dilemma is discussed in various conceptual guises in the literature on international organizations, multilevel governance and globalization (e.g., Dahl, Citation1994, pp. 27–32; Hooghe & Marks, Citation2016, pp. 7–19; Rodrik, Citation2011, pp. 200–205). Briefly, as the scale of governance expands, community thins out, while strong communities forgo benefits of scale. ‘Scale’ stands for the benefits of debordering. Opening borders for economic and cultural exchange improves factor allocation and knowledge. It enhances individual freedoms – e.g., to travel, find (better-paid) employment or escape culturally or politically oppressive social conditions. Larger governance regimes internalize cross-border policy externalities and help produce collective goods at lower per capita costs (economies of scale). In addition, they facilitate exchange by bringing together a larger group of potential cooperation partners with diverse beliefs, preferences and capabilities.

On the other hand, open boundaries tend to dilute the identity, solidarity, security and democratic self-rule of a community. While members of the community emigrate, foreigners with other mother tongues, values and cultural practices immigrate. The weakening bonds of identity may undermine the willingness of individuals to contribute to the public good and engage in social sharing (Bartolini, Citation2005, p. 53). Solidarity may suffer further from opportunities for exit such as tax evasion, capital flight or brain drain. Differentiated integration facilitates cherry-picking behaviour and inhibits solidarity. With regard to security, debordering weakens the capacity of the community to protect itself against not only transnational crime, espionage, and military attacks, but also external political influence and interference. This is one way, in which debordering harms democracy. In addition, larger units increase the distance and lengthen the chain of accountability between citizens and the authorities, and they raise the costs and reduce the opportunities for participation. Finally, weak collective identity and solidarity undermine the social foundations of democracy.

By contrast, higher and better-enforced barriers and congruent external boundaries reduce exit and entry opportunities and boundary arbitrage. Locking in actors and resources helps to preserve the cultural homogeneity and identity of the people living inside the territory, strengthen institutions of social sharing, protect the territory from outside threats to security – and thereby build the social foundations of democracy (Bartolini, Citation2005, pp. 36–53; Rokkan, Citation1974, p. 49). Community protection, however, often comes at the price of curbing individual freedoms and of scale deficits, such as inefficient factor allocation and governance failure.

To formulate a set of general assumptions about the conditions of the bordering process, let us posit that policy-makers design boundary configurations so that the balance of scale and community effects matches societal preferences. Major changes in the boundary gaps and transactions upset this scale-community equilibrium.

Wider boundary gaps increase rebordering pressures. Boundary gaps – disparities between territories on each side of the border – affect the demand for and the kind of boundary transactions. For instance, large income gaps generate demand for economic migration; small cultural and political gaps facilitate friendly and frequent transactions. States adjust the closure and control of their borders to the perceived threats and opportunities of the boundary gap and the (anticipated) boundary transactions. Generally, the narrowing of boundary gaps facilitates debordering. It reduces perceived threats to community, increases opportunities of scale and provides for symmetrical transactions. As a peaceful and multilateralist club of wealthy liberal democracies, the EU is most likely to open its borders to states of the same type. Conversely, it is likely to close and control its borders with poor, autocratic, nationalist, aggressive and conflict-ridden states for lack of common values and interests, as well as opportunities to cooperate, and for fear of migration, interference and corruption. In this way, the liberalization and democratization of the EU’s international environment has paved the way for external debordering in the 1980s and 1990s, whereas autocratization has become a major condition of rebordering in the 2010s.

Shocks to boundary transactions increase pressures to change the boundary configuration. Boundary transactions can also be subject to changes that are unrelated to differences and similarities of territories on both sides of the border. In particular, exogenous systemic shocks lead to major disruptions in the ‘normal’ quality and quantity of transactions, which underpin the existing boundary configuration. The global financial crisis, the refugee crisis and the Corona pandemic were such shocks causing desired transactions (such as foreign credit) to stop and undesired transactions (such as asylum requests and virus infections) to surge. Existing rules, competences and capacities of boundary closure and control, which face such shock-induced transaction changes and fail to provide scale benefits and prevent community deficits, worsen political performance and produce demand for boundary reconfiguration.

Community deficits generate boundary politicization. Community deficits – such as rising inequality, threats to national identity, or an increase in crime and military vulnerability – lead to the politicization of boundaries. Boundary issues come to define the main axes of political conflict and shape political coalitions. Both the economic (left-right) and the cultural (GAL-TAN) dimensions of politics are interpreted in terms of boundary openness (e.g., free trade and multiculturalism) vs. boundary closure (e.g., trade protectionism and burqa bans) – strengthening the ‘integration-demarcation’ (Kriesi et al., Citation2006) or ‘cosmopolitan–communitarian’ (De Wilde et al., Citation2019) political cleavage. Communitarians supporting closure and control form parties, enter into political alliances and coalitions, and gain political support and influence by mobilizing the economic, cultural and political losers of debordering. The politicization of community deficits translates into electoral gains for (nationalist, Eurosceptic) pro-rebordering parties and governments, which will shift the distribution of power at the national and the EU level to their advantage and increase the pressure to renegotiate the EU’s boundaries. This is the background to the populist backlash against debordering.

The choice of internal vs. external rebordering depends on relative feasibility and costs. Whether rebordering pressures and negotiations result (predominantly) in internal or external solutions, however, depends on the feasibility and costs of these options. The more difficult the external boundary reconfiguration is to negotiate, the less effective it promises to be in overcoming the deficits of the boundary configuration, and the more scale and community costs it produces relative to the internal solution, the more likely EU negotiators will fail to agree on external rebordering and governments will revert to internal bordering.

For several structural reasons, rebordering pressures are likely to produce demand for external rather than internal rebordering. First, the scale losses of rebordering are typically more pronounced for internal than for external closure: between member states, interdependencies are usually higher than between member and non-member states. Second, the boundary gaps between member and non-member societies are generally higher than between member states. External rebordering therefore provides higher community gains than internal rebordering. For these reasons, communitarians facing the scale-community dilemma likely focus their rebordering demands on the external borders; and pro-integration parties and governments give in to calls for external rebordering in order to safeguard internal debordering. Moreover, the EU-level institutional constraints for internal rebordering are higher than for external rebordering: EU treaty rules and the power of supranational organizations for securing the openness of internal boundaries are more robust than in the case of external boundaries. These conditions support the expectation that, in responding to rebordering pressures, EU actors favour external rebordering and thereby aim to put or keep the EU on an effective integration trajectory.

Yet, general structural conditions may not be sufficient to prevent internal rebordering or disintegration in specific situations and issue-areas. Especially in their initial response to boundary shocks, governments are likely to resort to unilateral, national bordering policies before EU-level boundary negotiations start or conclude. Such crisis measures only lead to transitory disintegration. In the longer run, however, negotiations may still fail to produce collective external rebordering for any of the following reasons: too heterogeneous member state preferences and interdependencies; insurmountable collective action problems; and external actors capable of overpowering joint EU capacities and dividing the membership.

Contributions and findings: a preview

The contributions to this collection do not represent a selection of comparative cases designed to test the analytical framework, but explore a variety of EU bordering issues, actors and processes at different levels: the migration (Kriesi et al., Citation2021) and Corona pandemic crises (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2021), the preferences of EU citizens in response to the migration crisis (Lutz & Karstens, Citation2021) and of populist parties on EU defence policy (Henke & Maher Citation2021), parliamentary discourses on enlargement (Bélanger & Schimmelfennig, Citation2021), EU regulatory agencies (Lavenex et al., Citation2021), and EU collective action on defence, migration and the neighbourhood policy (Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, Citation2021).

They paint a nuanced picture of rebordering for these variegated issues and actors. Whereas external rebordering features in all accounts, its extent and impact on the overall integration trajectory varies. For the migration crisis, Kriesi et al. (Citation2021) describe a combination of internal and external rebordering, resulting in a defensive integration trajectory. Genschel and Jachtenfuchs observe a similar sequence of internal and external rebordering of the movement of persons in the Corona crisis, but also an internal debordering of solidarity that failed to materialize in the migration crisis. At the level of citizens, Lutz and Karstens (Citation2021) find that the migration shock of 2015 strengthened preferences for external rebordering without undermining support for internal debordering, thus generating public support for effective integration. Whereas populist parties generally share an anti-immigration agenda, Henke and Maher (Citation2021) do not find a consistent and distinctive pattern for their positions on European defence integration. Bélanger and Schimmelfennig (Citation2021) observe a marked slowdown of the enlargement and association process after 2007. In the same period, the parliamentary discourse on enlargement has remained generally open and based on inclusive frames – but with a marked recent trend towards more negative positions and communitarian frames. In a comparative analysis of EU regulatory agencies, Lavenex et al. (Citation2021) find that these functional bodies have retained their flexible and incongruent boundaries with non-member states. However, the Commission and the Parliament have claimed increasing supranational political control over these agencies producing a pattern that they name ‘controlled debordering’. Finally, Eilstrup-Sangiovanni (Citation2021) describes the limits of effective EU external rebordering capacity in the areas of defence, migration control and neighbourhood policy and expects a trajectory of disintegration as a result.

What drives and constrains the ‘rebordering of Europe’ in these contexts? In line with the analytical framework, the articles on the migration and Corona crises show how an external shock in boundary transactions overwhelmed a boundary regime characterized by weak supranational competences and capacities as well as insufficient national capacity, producing both boundary politicization and renegotiation. In the migration crisis, the analysis further shows how the asymmetric problem and political pressures on the member states prevented a comprehensive reform of the boundary configuration, resulting in a variety of unilateral policies. In the end, the failure to agree on internal debordering resulted in a focus on external rebordering: the strengthening of collective border protection capacity and agreements on closure with third countries (Kriesi et al., Citation2021). The effectiveness of national policies and external rebordering in bringing down the number of asylum-seekers and thus overcoming the exogenous shock marks the major difference to the Corona crisis, in which defensive integration was insufficient to cope with the economic hardships, disparities and interdependencies of the member states. This situation paved the way for an unprecedented step of supranational fiscal capacity building and sharing (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2021). When it comes to capacity building for external integration, however, such as joint defence or intervention forces and physical border protection, Eilstrup-Sangiovanni (Citation2021) regards the formidable collective action problems resulting from the public goods properties of these policies as a major obstacle. This is in contrast with effective integration in commercial policy, where autonomy costs are low and joint gains high.

In line with the expectation of communitarian politicization, Bélanger and Schimmelfennig (Citation2021) find that parliamentary discourse on enlargement is structured, indeed, by partisan conflict along the cultural cleavage. In addition, political, geographic and cultural boundary gaps affect the claims that parliamentarians make. Discursive rebordering is particularly strong when parties on the cultural right speak about Muslim-majority countries. Lavenex et al. (Citation2021) also find that the politicization of an agency’s portfolio (in addition to higher agency authority) favours debordering. Most regulatory agencies are so weakly politicized, however, that their boundary configuration follows functional needs rather than communitarian concerns.

Obviously, the collection cannot provide general conclusions on the trajectory of bordering and integration in Europe and its drivers and obstacles. Yet it provides ample evidence for rebordering pressures in current EU politics and points to the relevance of studying integration as a combination of internal and external bordering.

Acknowledgments

I thank the Robert Schuman Centre of the European University Institute for hosting the authors’ workshop for this special issue. I am further grateful to the contributors and to the JEPP reviewers for comments on earlier versions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Frank Schimmelfennig

Frank Schimmelfennig is Professor of European Politics at ETH Zurich, Switzerland. For more details, see https://eup.ethz.ch/people/prof-frank-schimmelfennig.html.

Notes

1 I use ‘border’, ‘boundary’ and their derivatives interchangeably throughout this article.

2 There is a rich literature on bordering that I cannot review and include here. In contrast to my conceptual and theoretical framework and the contributions to this special issue, it is based on critical or poststructuralist theory and ethnographic methods, however (e.g., Van Houtum et al., Citation2016; Yuval-Davis et al., Citation2019).

3 I use this perspective as a helpful conceptual heuristic, but do not subscribe to systems theory or any specific version of it, to theorize European integration or bordering. See Albert (Citation2002) for an application of Luhmann’s systems theory to European integration and Trenz (Citation2011) on sociological theorizing and European integration.

4 ‘Globalisation has faltered’, The Economist, 24 January 2019, https://www.economist.com/briefing/2019/01/24/globalisation-has-faltered (accessed 13 October 2020).

References

- Albert, M. (2002). Governance and democracy in European systems: On systems theory and European integration. Review of International Studies, 28(2), 293–309. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210502002930

- Bartolini, S. (2005). Restructuring Europe. Center formation, system building, and political structuring between the Nation State and the European Union. Oxford University Press.

- Bélanger, M., & Schimmelfennig, F. (2021). Politicization and Rebordering in EU Enlargement: Membership Discourses in European Parliaments. Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1881584

- Bergmann, J., & Niemann, A. (2018). From neo-functional peace to a logic of spillover in EU external policy: A response to Visoka and Doyle. Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(2), 420–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12608

- Bieber, F. (2018). Patterns of competitive authoritarianism in the Western Balkans. East European Politics, 34(3), 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2018.1490272

- Bradford, A. (2020). The Brussels Effect: How the European union rules the world. Oxford University Press.

- Copelovitch, M., Frieden, J., & Walter, S. (2016). The political economy of the Euro crisis. Comparative Political Studies, 49(7), 811–840. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414016633227

- Dahl, R. (1994). A democratic dilemma. Political Science Quarterly, 109(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.2307/2151659

- Daugbjerg, C. (2017). Responding to non-linear internationalisation of public policy: The World Trade Organization and reform of the CAP 1992–2013. Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(3), 486–501. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12476

- De Wilde, P., et al. (ed.). (2019). The struggle Over borders. Cosmopolitanism and communitarianism. Cambridge University Press.

- Eilstrup-Sangiovanni, M. (2021). Re-bordering Europe? Collective Action Barriers to 'Fortress Europe'. Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1881585

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2014). Introduction. Beyond market regulation. Analysing the European integration of core state powers. In P. Genschel, & M. Jachtenfuchs (Eds.), Beyond the regulatory polity? The European integration of core state powers (pp. 1–23). Oxford University Press.

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2018). From market integration to core state powers: The Eurozone crisis, the refugee crisis and integration theory. Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(1), 178–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12654

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2021). Postfunctionalism reversed: Solidarity and rebordering during the Corona-crisis. Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1881588

- Haas, E. (1968). The uniting of Europe. Political, social, and economic forces 1950–1957 (2nd ed.). Stanford University Press.

- Haas, E. (1976). Turbulent fields and the theory of regional integration. International Organization, 30(2), 173–212. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300018245

- Henke, M., & Maher, R. (2021). The Populist Challenge to European Defense. Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1881587

- Hoffmann, S. (1966). Obstinate or obsolete? The fate of the nation-state and the case of Western Europe. Daedalus, 95(3), 862–915.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2009). A postfunctionalist theory of European integration: From permissive consensus to constraining dissensus. British Journal of Political Science, 39(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000409

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2016). Community, scale and regional governance. A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance II. Oxford University Press.

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2018). Cleavage theory meets Europe’s crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the transnational cleavage. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(1), 109–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279

- Jones, E., Kelemen, R. D., & Meunier, S. (2016). Failing forward? The Euro crisis and the incomplete nature of integration. Comparative Political Studies, 49(7), 1010–1034. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414015617966

- Kriesi, H., Altiparmakis, A, Bojar, A, Oana, N. (2021). Debordering and re-bordering in the refugee crisis: a case of ‘defensive integration’. Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1882540

- Kriesi, H., Grande, E., Lachat, R., Dolezal, M., Bornschier, S., & Frey, T. (2006). Globalization and the transformation of the national political space: Six European countries compared. European Journal of Political Research, 45(6), 921–956. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2006.00644.x

- Lavenex, S., Krizic, I., Veuthey, A. (2021). EU boundaries in the making: Functionalist versus federalist. Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1881586

- Ludlow, N. P. (2006). From deadlock to dynamism. The European community in the 1980s. In D. Dinan (Ed.), Origins and evolution of the European Union (pp. 218–232). Oxford University Press.

- Lührmann, A., & Lindberg, S. (2019). A third wave of autocratization is here: What is new about it? Democratization, 26(7), 1095–1113. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2019.1582029

- Lutz, P., & Karstens, F. (2021). External borders and internal freedoms: How the refugee crisis shaped the bordering preferences of European citizens. Journal of European Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2021.1882541

- Moravcsik, A. (1991). Negotiating the single European Act. National interests and conventional statecraft in the European community. International Organization, 45(1), 19–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300001387

- Moravcsik, A. (1998). The choice for Europe: Social purpose and state power from Messina to Maastricht. Cornell University Press.

- Niemann, A. (2006). Explaining decisions in the European Union. Cambridge University Press.

- Popescu, G. (2012). Bordering and ordering the twenty-first century. Understanding borders. Rowman and Littlefield.

- Rodrik, D. (2011). The globalization paradox: Democracy and the future of the world economy. Norton.

- Rokkan, S. (1974). Entries, voices, exits: Towards a possible generalization of the Hirschman model. Social Science Information, 13(1), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847401300103

- Schimmelfennig, F. (2018). European integration ‘theory’ in times of crisis. A comparison of the Euro and Schengen crises. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(7), 969–989. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1421252

- Schimmelfennig, F., & Sedelmeier, U. (eds.). (2005). The Europeanization of central and Eastern Europe. Cornell University Press.

- Schmitter, P. C. (1969). Three neo-functional hypotheses about international integration. International Organization, 23(1), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300025601

- Scipioni, M. (2018). Failing forward in EU migration policy? EU integration after the 2015 asylum and migration crisis. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(9), 1357–1375. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1325920

- Trauner, F. (2016). Asylum policy – the EU’s ‘crises’ and the looming policy regime failure. Journal of European Integration, 38(3), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2016.1140756

- Trenz, H. (2011). Social theory and European integration. In A. Favell, & V. Guiraudon (Eds.), Sociology of the European Union (pp. 193–214). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Van Houtum, H., Kramsch, O., & Zierhofer, W. (eds.). (2016). B/ordering space. Routledge.

- Vollaard, H. (2018). European disintegration. A search for explanations. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Webber, D. (2018). European disintegration? The politics of crisis in the European Union. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Yuval-Davis, N., Wemyss, G., & Cassidy, K. (2019). Bordering. Polity Press.