ABSTRACT

This article aims to explain the Commission's decisions after formal investigations in the EU state aid regime. It proceeds from the idea that the Commission is confronted with an enforcement dilemma: it must weigh the benefits of promoting undistorted competition on the internal market against the potential costs of losing member state support. This study explores to what extent characteristics of state aid cases and characteristics of member states influence this dilemma and thereby the Commission's decisions. Based on multilevel logistic regression analysis of a newly created dataset consisting of all formal investigations initiated and decided on by the Commission between 2004 and 2018, we find that aid that has been granted unlawfully and aid consisting of tax measures is more likely to result in a negative decision. Member states characterized by a larger administrative capacity are less likely to face negative decisions.

Introduction

The European competition regime stands out for being one of the Union's most supranational policy frameworks (Karagiannis, Citation2010, p. 600). As part of this regime, the European Union (EU) state aid rules curtail member states’ autonomy in designing state aid policies. While it can be tempting for member states to grant state aid to promote certain economic activities, this may distort the internal market. Therefore, EU state aid rules, including the Commission's competence to decide on their correct application, have been in the European Treaties from 1957 onwards.

As regulating national state aid policies remained politically sensitive, it took until the 1980s before these rules started to be strictly enforced (Cini & McGowan, Citation2009, p. 176). By developing a body of soft law, aided by supportive rulings by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) and the increasing engagement of private complainants, the Commission succeeded in strengthening its enforcement position (e.g., Blauberger, Citation2009; Cini, Citation2001; Doleys, Citation2013). These developments eventually resulted in the introduction of hard law (Regulation 994/98/EU and Regulation 659/1999/EU) at the end of the 1990s.Footnote1

Within this body of law the Commission, however, still has some room for maneuver (Cini & McGowan, Citation2009, p. 166; Jones & Sufrin, Citation2016, p. 2) and uses this leeway to be more cautious in some cases, while being stricter in others. For example, during the financial crisis, it temporarily adopted a more lenient enforcement of state aid rules due to the pressure exercised by member states to allow the bail out of financial sector organizations (Botta, Citation2016). The Commission adopted a similar approach in response to the COVID-19 outbreak. By creating a temporary crisis framework, it provided member states with the possibility to make use of the ‘full flexibility under the state aid rules’ (European Commission, Citation2020b). On the other hand, in 2014, the Commission started in-depth investigations on a series of beneficial tax treatments for multinational corporations, which led to negative decisions and recovery of the ‘illegal’ financial advantages granted to these corporations (European Commission, Citation2020a). This happened despite significant opposition of the member states involved. For example, in the case of Apple, the Irish government had insisted that it would fight any negative decision since the Commission's opening of the case (Halpin & Humphries, Citation2016).

A possible explanation for these differences lies in the enforcement dilemma the Commission is confronted with: on the one hand, it must consider the benefits of enforcing the rules, i.e., undistorted competition on the internal market; on the other hand, however, it must consider the costs of doing so, most importantly the costs of potentially losing member states’ support (Blauberger, Citation2011; Doleys, Citation2013; Kassim & Lyons, Citation2013).

A recent study by Finke (Citation2020) shows support for this ‘costs’ argument when it comes to the Commission's decisions after a so-called Formal Investigation (FI), one of the Commission's most important instruments in enforcing state aid rules. Under article 108(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), the Commission has the ability to initiate a FI against a member state if it has serious doubts about the compatibility of state aid measures with the internal market (European Commission, Citation2013). FIs eventually result in a decision that measures are compatible with the internal market or a negative decision (European Commission, Citation2013). Finke (Citation2020, p. 19) concludes that several political attributes of member states affect the costs associated with Commission decisions, including the likelihood of a member state's appeal.

While these findings are in line with the EU enforcement literature on the outcomes of the infringement procedure (e.g., Börzel et al., Citation2010; Hofmann, Citation2018), they also relate to a time period (2000–2018) that may not be fully representative of the current situation due to the implementation of some major reforms that have taken place (most notably the Commission's refined economic approach as part of the State Aid Action Plan in 2005). The study of Finke (Citation2020) also does not include other factors, such as non-political member state characteristics or the Commission's own preferences, which have been identified as important factors in the broader EU enforcement literature (e.g., Börzel et al., Citation2010; König & Mäder, Citation2014). An explorative study by Buts et al. (Citation2011), however, shows that several state aid case characteristics, which can be linked to the Commission's preferences, are important determinants of Commission decisions.

Against this background, this article studies the impact of the enforcement dilemma on the Commission's decisions taken between 2004 and 2018, by analyzing the extent to which both state aid case and member state characteristics affected these decisions. This results in the following question:

To what extent do state aid case and member state characteristics influence Commission decisions after formal investigations?

To answer this question, this study uses a newly created dataset consisting of all FIs initiated and decided on by the Commission between January 2004 and December 2018, based on the Commission's publicly accessible State Aid Register. Because potential explanations exist at the level of state aid cases and member states, the study employs multilevel logistic regression analysis to explain the observed variance in decisions. The dataset is used to test several hypotheses.

The relevance of this article is twofold. Firstly, it strengthens our understanding of the day-to-day functioning of the EU state aid regime, thus adding insights to the political science literature on state aid. Most political science studies on the EU state aid regime focus on its overall historical development (Cini, Citation2001; Cini & McGowan, Citation2009; Doleys, Citation2013) or on the effects of EU rules on trends in state aid spending (Franchino & Mainenti, Citation2013; Zahariadis, Citation2013).

Secondly, the study serves to enrich our understanding of EU enforcement more broadly. Most EU enforcement studies test for explanatory factors having an effect on the infringement procedure, specified by article 258 TFEU (e.g., Börzel et al., Citation2010; Börzel & Sedelmeier, Citation2017; Hofmann, Citation2018). As a result, policy-specific EU enforcement procedures have remained underresearched (but see Schmälter, Citation2018). By explaining enforcement behavior in FIs, this study opens up venues for making comparative assessments of the Commission's enforcement behavior in different institutional settings. We return to this in the conclusion.

This study starts with an introduction to the functioning of the formal investigation procedure. The subsequent section discusses the Commission's need to balance the promotion of undistorted competition with securing member state support in enforcing state aid rules and presents several theoretical explanations for the outcomes of FIs. This is followed by a discussion of the dataset, operationalization and methods of analysis in the methods and data section. The outcomes of our analyses are presented in the results section. The final section summarizes the main conclusion and discusses the limitations and implications of this research.

The formal investigation procedure

Article 107–109 TFEU regulate EU state aid control. Article 107(1) TFEU comprises the general incompatibility of state aid to undertakings with the internal market. However, this general prohibition is nuanced by article 107(2) and 107(3) TFEU, respectively stating that some types of state aid shall and may be exempted (European Commission, Citation2013). The competence to interpret, apply, and enforce these substantive provisions is attributed to the Commission under article 108 TFEU (Doleys, Citation2013, p. 26). More specific rules are elaborated in Regulation 2015/1589/EU. This Regulation assigns the Commission the competence to decide over the legality of individual state aid measures on the basis of the substantive state aid provisions of article 107 TFEU.Footnote2 Article 108(3) TFEU obliges member states to notify their intended state aid measures to the Commission. These new measures need to be approved by the Commission in so-called preliminary investigations before they can be put into effect.

However, if the Commission has serious doubts about the compatibility of an aid measure, it has the legal obligation to initiate a FI on the basis of article 108(2) TFEU. FIs must also be opened by the Commission if serious doubts arise about already granted (allegedly unlawful) aid – for which investigations were started on the basis of its own initiative or on the basis of a formal complaint by a possibly affected third party – that has not been notified (European Commission, Citation2013).Footnote3

After the Commission initiates a FI, it sends a letter to the member state with the request of submitting its opinion on the case within one month. Interested parties and other member states are also invited to issue comments within one month of the opening decision (European Commission, Citation2013). Member states then have an additional month to react to the comments issued by interested parties. Subsequently, the Commission examines the information provided by the member state and interested parties and, if necessary, can require the member state to submit additional information. This eventually results in adopting a final decision to close the FI.

FIs can have the outcome that the measure is compatible (positive, ‘no aid’ or conditional decision)Footnote4 or incompatible with EU law (negative decision). A negative decision has the consequence that the state aid measure is deemed illegal. This means that new aids are not allowed to be granted or unlawful aids need to be recovered.

Explaining the outcomes of formal investigations

Balancing the Commission's interests

The open formulation of the treaty provisions grants the Commission a relatively large degree of discretion in deciding how to apply state aid rules (Doleys, Citation2013, p. 24). While it has developed a body of soft law based on its previous decisions and rulings by the CJEU over the last decades, it still has room for maneuver in applying rules to individual cases (Cini & McGowan, Citation2009, p. 166; Jones & Sufrin, Citation2016, p. 2). The application of the rules also takes place in a politically sensitive environment as decisions directly target member states and may lead to considerable public attention (Blauberger, Citation2011, p. 28; Kassim & Lyons, Citation2013). These two characteristics offer ample room for conflicts to arise about the interpretation of rules in individual cases. In a case study on subsidies to Volkswagen, Thielemann (Citation1999) describes how this conflict even resulted in talks between the Commission and Germany at the highest political level.

Within this context, the Commission aims to ensure a well-functioning internal market by preventing market distortion (European Commission, Citation2012). At the same time, it also depends on member states’ support for the delegation of competences in state aid control as well as for other tasks. Too strict enforcement can endanger this support; member states have several formal and informal mechanisms at their disposal that they can use to challenge the Commission (Doleys, Citation2013, p. 27). For example, member states may decide to challenge the Commission's decision by initiating annulment cases and subject a decision to judicial review by the CJEU (Adam, Citation2016, p. 87).Footnote5 They may also use informal channels to challenge the Commission's decisions by not complying with the rules. In addition, member state resistance can manifest itself outside the scope of the state aid regime. Zahariadis (Citation2013, p. 148) argues that too strict enforcement may lead individual member states (to threaten) to withdraw their support for Commission policy initiatives in other areas.

Based on the broader EU enforcement literature (e.g., Fjelstul & Carrubba, Citation2018; Steunenberg, Citation2010), we assume that the Commission makes an assessment of the political costs and benefits involved in taking a decision. This assessment already affects the initial decision to open a FI: while the Commission formally has to take a decision within two months after the start of a preliminary investigation, the procedure is often delayed. Typically, the Commission attempts to find compromises with member states on how to adjust measures in order to secure compatibility with the internal market (Einardsson & Kekelis, Citation2015, p. 42). However, if these attempts fail, the Commission has the legal obligation to initiate a FI.

According to Cini and McGowan (Citation2009, p. 174), the procedure becomes ‘unambiguously adversarial’ from this moment onwards, as the stakes become higher. A careful assessment of the costs and benefits of taking a negative decision will become even more important for the Commission. To foretell when the benefits outweigh the costs or vice versa and what effect this has on the eventual decision being taken, we discuss several factors below.

Firstly, we present several variables that increase the benefits related to taking a negative decision. We argue that these variables can be found at the state aid case level. Secondly, insights from the recent study of Finke (Citation2020), as well as from the EU enforcement literature, are used to identify variables that increase the potential costs related to taking a negative decision. These variables can be found at the member state level.

The benefits of undistorted competition: state aid case level explanations

As discussed above, the Commission aims to prevent distortion of the internal market. As the capacity available to the Commission is limited, it is forced to focus enforcement on ‘cases with the biggest impact on the internal market’, i.e., in areas that the Commission considers most distortive (European Commission, Citation2012, p. 7). This latter argument can be linked to findings that the Commission's policy preferences affect its inclination to initiate infringement procedures (König & Mäder, Citation2014; Steunenberg, Citation2010). We assume that this also applies to state aid decisions and that the benefits of taking negative decisions differ for different types of aid. We test this for several types of aid measures.

One measure that is considered highly distortive is aid with the objective of rescuing and restructuring firms in difficulty. These aids are important to member states because of their use in preserving firms (and therewith jobs) that are crucial to their national economies, but are unpopular with the Commission, because they prevent uncompetitive firms from exiting the market (Adam, Citation2016, p. 96). For these objectives, it can be expected that the Commission considers the benefits of taking a negative decision to be higher than for other aid objectives, such as promoting regional and sectoral development.Footnote6 This leads to the following hypothesis:

H1: FIs of cases of which the objectives are rescuing and restructuring firms in difficulty are more likely to be met by a negative decision.

H2: FIs of cases in which the instrument is a tax measure are more likely to be met with a negative decision.

H3: FIs that originate from unlawful aid are more likely to be met with a negative decision.

The costs of losing member state support: member state level explanations

Apart from the benefits of taking a negative decision, there are also costs for the Commission that result from the prospect that member states will challenge a negative decision. Drawing on enforcement and management approaches to compliance, we expect the likelihood of a challenge to depend on member states’ willingness and ability to comply with state aid rules (Tallberg, Citation2002).

In the literature, we find two type of approaches that explain this willingness: a preference-based and a legitimacy approach (Börzel et al., Citation2010). Within a preference-based approach, a member state's decision to comply depends on its cost–benefit analysis of its consequences (Downs et al., Citation1996). A first relevant factor to consider is therefore the preferences of a government on state intervention (Finke, Citation2020; Zahariadis, Citation2013). We expect that governments that are more prone to intervene in the economy also consider the benefits of granting state aids as higher and will also be more willing to challenge a (possible) negative decision by the Commission. Governments that consider the benefits as less important will be less willing to challenge, and in fact might even (tacitly) welcome a negative decision.Footnote8 As a challenge increases the costs for the Commission to take a negative decision, it will be less likely to do so. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H4: The more interventionist a member state's government, the less likely the Commission will take a negative decision.

H5: The more powerful a member state, the less likely the Commission will take a negative decision.

H6: The more pro-EU a member state's government, the more likely the Commission will take a negative decision.

H7: The higher a member state's level of public trust in the Commission, the more likely the Commission will take a negative decision.

Altogether, this will lead to a stronger legal defense of an aid measure, which increases the Commission's costs of taking negative decisions. This results in the following hypothesis:

H8: The larger a member state's administrative capacity, the less likely it is the Commission will take a negative decision.

Control variables

When testing for the impact of these factors, several other factors need to be controlled for. A first factor is the Directorate General (DG) responsible for the assessment in a FI. Assessments are executed by different DGs and characteristics of these organizations may affect the outcomes of FIs. Two other factors that have to be controlled for are time-related: firstly, the Commission that was responsible for taking a decision. The research period (2004–2018) covers FIs decided on by three different Commissions. Secondly, the introduction of the amended Procedural Regulation in 2013 may have had an effect.Footnote9 This reform, part of the broader State Aid Modernization (2012–2016), granted the Commission larger competences to obtain case-specific market information (Dilkova, Citation2014). This may have strengthened its information position, increasing the likelihood of negative decisions in the post-reform period.Footnote10

Methods and data

Data collection

The hypotheses are tested on the basis of a self-developed dataset. This dataset consists of all FIs opened and decided on by the Commission between January 2004 and December 2018. The enlargement of the EU in 2004 underlined the need to reduce the administrative costs of EU state aid control, eventually leading to the State Aid Action Plan initiatives in 2005. In 2005, the Commission introduced its ‘refined economic approach’ that was intended to lead to a more consistent and systematic application of rules (European Commission, Citation2005). Apart from capturing the new post-reform situation, taking January 2004 as a starting point also allows us to keep the population of member states against which FIs can be initiated relatively constant. The dataset was constructed on the basis of the publicly accessible Commission's State Aid Register (Register, Citation2019). As the Commission uses the objective criterion of having ‘doubts about’ or experiencing ‘serious difficulties in determining’ the compatibility of aid when opening a FI, we assume that all cases have the same starting position and there are no large differences between them in terms of the probability that these cases receive negative decisions (European Commission, Citation2013, p. 58).Footnote11

Initially, the dataset consisted of 563 FIs. This dataset was further specified by deleting all FIs for which no decisions had been taken yet on 1 January 2019 (n = 66), FIs that were withdrawn from the procedure by member states because they no longer intended to grant aid (n = 53) and FIs that were closed by the Commission (n = 5). Applying these exclusion criteria resulted in a final dataset consisting of 439 cases.

Operationalization

Dependent variable

The dependent variable, a negative decision in a FI, was measured by creating a dichotomous variable. Negative decisions were coded 1; all other decisions (no aid, positive and conditional) were coded 0. Decisions in which parts of the state aid measures were decided on negatively (n = 43) were also coded 1. This means that all state aid measures that had to be abolished or could not be implemented by member states are captured by this measure. The information was obtained from the Register (Citation2019).

Independent variables

Values on state aid characteristics were obtained from the Register (Citation2019). Firstly, the variable objective of aid resulted in a dummy variable for the state aid objectives ‘restructuring firms in difficulty’ and ‘restructuring firms in difficulty’ as opposed to other objectives. Secondly, the variable aid instrument was measured as a dummy for all aid instruments that consisted of ‘tax rate reduction’, ‘tax deferment’, ‘tax base or rate reduction’, ‘tax allowance’, ‘tax advantage or tax exemption’ and ‘other forms of tax advantage’ as opposed to other aid instruments. Finally, the variable origin of aid was measured as a dummy variable consisting of all cases for which the origin was ‘unlawful’ as opposed to ‘notified’ or ‘existing’.

To measure the intervention position of a government, we followed Finke (Citation2020, p. 13) by taking the average of positions on state intervention in the economy of the parties in office relative to their seat share. Earlier studies on the relationship between government preferences and state aid spending considered partisanship as a relevant indicator, but Zahariadis (Citation2013) shows that findings of the relationship between partisanship and state aid spending have been inconclusive. Finke's measuring of this variable builds upon Lowe’s et al. (Citation2011) scaling of party positions in manifestos on the basis of the logarithm of odds ratios. For measuring the intervention position of a government, Lowe’s et al. (Citation2011, p. 139) dimensions on ‘state involvement in the economy’ were used. Data were obtained from the 2018 dataset of the Comparative Manifesto Project (Volkens et al., Citation2018).

We operationalized member state power as the political power of a member state within the EU. These variables were measured by using the Shapley Shubik Index, indicating the frequency of a member state playing a pivotal role in forming majorities under qualified majority rules in the Council of Ministers (Antonakakis et al., Citation2014).

We also followed Finke (Citation2020, p. 13) in measuring the EU position of a government as the average of positions on the EU of the parties in office relative to their seat share on the basis of the same logarithm of odds ratios. The EU position for each party was established by weighing the number of positive and negative statements of EU integration in parties’ manifestos. These data were also obtained from the 2018 dataset of the Comparative Manifesto Project (Volkens et al., Citation2018).

To measure public trust in the European Commission, we obtained data on public trust in the Commission from the autumn European Barometer report. For all years from 2004 to 2018, the variable reflects the percentage of respondents in a member state that ‘tends to trust the European Commission’ (Eurobarometer, Citation2019).

We operationalized administrative capacity as the quality of a member state's bureaucracy. This variable is captured by Kaufmann et al.’s (Citation2010) index on government effectiveness, which covers bureaucratic quality components such as the civil service's quality and the capacity of a government to effectively design and implement policies. For all years, the data for this variable were obtained from the World Bank (Citation2019).

To control for the DG responsible for the assessment of cases, we included a dummy variable consisting of all FIs assessed by DG competition as opposed to DG Agriculture and DG Fisheries.Footnote12 The effect of different Commissions on the outcome of FIs was controlled by including dummies for the Commissions responsible for decision-making. Finally, the effects of the State Aid Modernization (SAM) reform were controlled by constructing a dummy for the pre- and post-reform period. An overview of the operationalization of the variables included can be found in the online appendix.

Method of analysis

Because the dependent variable is dichotomous, logistic regression models were used to estimate the effects of explanatory factors. In addition, as the assumption of independence of errors was violated by the hierarchical structure of our data (state aid cases and member states), we used multilevel logistic regression modeling. This takes into account the two-level structure of our data and allows us to more accurately estimate the standard errors related to the effects of independent variables. This reduces the risk that we draw the conclusion that there are significant effects, while in reality, these significant effects are absent (type 1 errors) (Hox, Citation2010).

To test our hypotheses, two models were estimated: (1) a multilevel logistic model including all state aid level variables; and (2) a multilevel logistic model including all state aid level and member state level variables.Footnote13,Footnote14

Results

Descriptive results

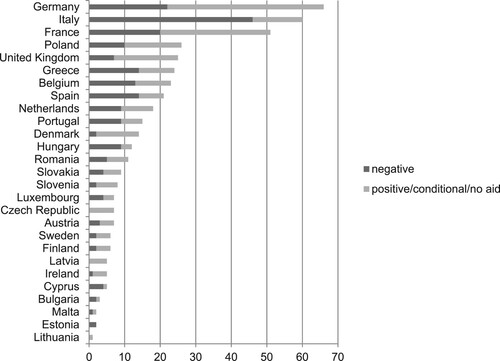

depicts the number of FIs opened and decided on between 2004 and 2018 and the share of FIs decided negatively on per member state. There is a large variation in the number of FIs that were decided on between member states. France, Germany and Italy are together responsible for 43 per cent (n = 177) of all FIs. At the same time, for 8 countries, less than 5 FIs were opened during the research period.Footnote15

Figure 1. Outcomes for FIs opened between 2004 and 2018 per member state. Source: Register (Citation2019).

The share of FIs that resulted in a negative decision also significantly differs between the member states. For all member states with five or more FIs opened and decided on during the research period, Italy (n = 60), Hungary (n = 12), and Spain (n = 21) stand out for facing the highest share of negative decisions as a share of the total number of FIs against that member state (respectively 76.7, 75.0, and 66.7 per cent). The Czech Republic (n = 7), Denmark (n = 14), and Slovenia (n = 8) faced the lowest proportion of negative decisions (respectively 0.0, 14.3, and 25.0 per cent).

Explanatory results

The results of the multilevel logistic regression models are shown in . Before estimating and interpreting our models, we first calculated the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC). This parameter indicates what share of the variance in the outcome of FIs can be explained by member state relative to individual state aid cases characteristics. The ICC in our null model was 0.116, meaning that 11.6 per cent of the variance in the outcome of FIs is explained by member state characteristics.Footnote16 Furthermore, the estimate of the variance at the member state level was significant, meaning that estimating multilevel logistic regression models has added value over ordinary logistic regression at one level.Footnote17

Table 1. Multilevel logistic models of the effects of variables on outcome of FIs (2004–2018).

Turning to the interpretation of the effects of the individual variables, shows that 2 out of 3 variables at the level of state aid cases are associated with a significantly higher likelihood of being met with a negative decision. These effects are relatively similar in both models. For cases consisting of tax measures, the odds ratios are equal to 2.11–2.16, meaning that these cases are 2.11–2.16 as likely to be met with a negative decision than cases consisting of other instruments. This means that hypothesis 2 is confirmed. For cases originating from unlawful aid, the odds ratios are equal to 2.42–2.44. This means that unlawfully granted aid is 2.42–2.44 more likely to be met with a negative decision. This confirms hypothesis 3. No evidence was found for rescue and restructuring objectives having an effect. This means that hypothesis 1 can be rejected.

Moving to the member state variables, the willingness-related variables turn out not to be significant in model 2.Footnote18 No evidence was found for either member state power, the position of a government on intervention in the economy or on the EU, or public trust in the Commission having an effect on the outcomes of FIs. This means that all hypotheses on willingness-related member state variables (hypotheses 4–7) can be rejected. However, our ability-related member state characteristic, administrative capacity, turns out to have a significant effect on the likelihood of taking a negative decision. If the value on administrative capacity of a member state increases by one point, this is related to an odds ratio of 0.48.Footnote19 This means that member states with a one point higher value on administrative capacity are less than half as likely to be met with a negative decision. The means that hypothesis 8 is confirmed. Finally, none of the control variables added to the models had a significant effect on the likelihood of taking a negative decision.

Conclusion and discussion

This study aimed to explain the outcomes of FIs by assessing the impact of state aid case and member state characteristics. Their impact was tested by employing multilevel logistic regression analyses on the basis of a newly created dataset of all FIs initiated and decided on between January 2004 and December 2018.

The results show that the likelihood of taking a negative decision is higher for FIs originating from unlawful state aid and for FIs of state aid that consists of tax measures. This indicates that the Commission regards the benefits of counteracting these types of aid higher than other types of aid. We also found evidence for higher levels of administrative capacity reducing the likelihood of the Commission taking a negative decision. In these situations, the Commission considers the costs of taking a negative decision as higher. No evidence was found for willingness-related member state characteristics having an effect on the outcomes of FIs. This last finding seems to suggest that these characteristics are less important in FIs than in the infringement procedure (see Börzel et al., Citation2010; Hofmann, Citation2018). Although there may be some discretion available to the Commission in applying rules in the state aid regime, this discretion may be less considerable due to the larger degree of legalization of the state aid procedures.

This last finding, however, contradicts those of Finke (Citation2020), who did find effects for these characteristics. The difference in results may be explained by the use of different methods of analysis (strategic statistical modeling). Alternatively, these differences could arise from using different time periods (2004–2018 instead of 2000–2018). Methodologically, including cases from before January 2004 more than doubles the size of the dataset, increasing the likelihood of finding significant effects. A substantive explanation, however, is that the reforms that were implemented in the state aid regime after 2004, most importantly the introduction of the ‘refined economic approach’, have led to a more consistent and systematic application of rules, thereby reducing the importance of member states’ political attributes (European Commission, Citation2005). These differences may also stem from the inclusion of state aid case level and ability-related member state variables in the analysis.

Whereas the functioning of the infringement procedure under article 258 TFEU has been object of a larger number of studies, political science research on the state aid procedures is still rare. This study constitutes one of the first steps in uncovering day-to-day enforcement in the EU state aid regime. In addition to statistical analyses, case studies are needed to investigate Commission-member state interaction in more detail. Such research can help to uncover how identified variables exactly influence decisions and what other, less easily quantifiable factors, play a role.

The literature on state aid in political science research is likely to grow in the coming years as the relevance of state aid policies will increase due to the economic consequences of the COVID-19 crisis. After the dust of the crisis settles, both the state aid responses and the post-crisis institutional relations between the Commission and member states are worthy of further study. This study may offer a valuable starting point to develop new directions in future research.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (78.5 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Daniel Finke for providing us with data on some of the independent variables and Pieter Kuypers, Johan van de Gronden, Ellen Mastenbroek, and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ruud van Druenen

Ruud van Druenen is a PhD candidate at the Institute for Management Research at Radboud University (the Netherlands).

Pieter Zwaan

Pieter Zwaan is Assistant Professor at the Institute for Management Research at Radboud University (the Netherlands).

Notes

1 Currently, these legal requirements are covered by respectively Regulation 651/2014/EU and Regulation 1589/2015/EU.

2 In addition, this competence also applies to the services of general economic interests under article 106(2) TFEU.

3 FIs can also be opened for existing aid that has been already approved by the Commission but is no longer compatible with the internal market. FIs for existing aid are relatively rare (n = 7/439) in our dataset.

4 In the case of a conditional decision, the measure is deemed compatible with EU law, but only if specific conditions are met.

5 In addition, article 108(2) allows the Council of Ministers to unanimously reverse a Commission decision on the prohibition of aid in exceptional circumstances (see Botta, Citation2016).

6 However, member states have not completely refrained from using these instruments. Although the chance of getting approval is lower, the benefits of getting a positive decision are considered high. A similar argument applies to tax measures and unlawful aid.

7 We believe that both Franchino and Mainenti (Citation2016) and Finke (Citation2020) wrongly use unlawful state measures as a proxy for measuring illegal aid. This is only a violation of procedural requirements under 108(3) TFEU and every unlawfully granted aid case first has to be assessed in a preliminary investigation before a FI can be opened. In addition, only 55 per cent of unlawfully granted aid cases for which a FI was opened was declared illegal, indicating that these measures also often constitute legal aid.

8 This may hold true for some specific cases, but we expect that the chance that this occurs will be lower for governments that are more willing to intervene in the economy than governments that are less willing to do so.

9 Regulation 734/2013/EU.

10 In order to control for organizational capacity available to the Commission, models were also estimated including year dummies. This did not change the results for our theoretical variables.

11 In addition, from a practical point of view, no distinction between legally ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ cases for which a FI is opened can be made at the time at which a FI is initiated.

12 The latter two were combined into one category, because of the low number of cases for these categories (respectively n = 24 and n = 8).

13 In both models, missing cases were deleted listwise.

14 Apart from these fixed slope models, models were also estimated for random slopes and several interaction terms. However, as no significant results were found in these models, these have not been included.

15 This group also included Croatia (no FIs opened).

16 As no level 1 variance is estimated in logistic regression models, we assumed that this variance was equal to the standard logistic distribution (= π2/3). This resulted in a ICC of (= 0.433/(0.433 + 3.29)) 0.116.

17 The p value for the variance estimate was 0.053 on the basis of a two-tailed test. This value cannot take a value below 0, meaning this value can be halved (= 0.027).

18 Also when adding the member state variables minus administrative capacity, no results were found for willingness-related variables.

19 The mean value on this variable is 1.14 with a standard deviation of 0.59.

References

- Adam, C. (2016). The politics of judicial review: Supranational administrative acts and judicialized compliance conflict in the EU. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Antonakakis, N., Badinger, H., & Reuter, W. H. (2014). From Rome to Lisbon and beyond: Member states’ power, efficiency, and proportionality in the EU Council of Ministers. Working paper no. 175. Vienna University of Economics and Business.

- Blauberger, M. (2009). Of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ subsidies: European state aid control through soft and hard law. West European Politics, 32(4), 719–737. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380902945300

- Blauberger, M. (2011). State aid control from a political science perspective. In E. Szyszczak (Ed.), Research handbook on European state aid law (pp. 28–24). Edward Elgar.

- Börzel, T. A., Hofmann, T., Panke, D., & Sprungk, C. (2010). Obstinate and inefficient: Why member states do not comply with European law. Comparative Political Studies, 43(11), 1363–1390. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414010376910

- Börzel, T. A., & Sedelmeier, U. (2017). Larger and more law abiding? The impact of enlargement on compliance in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(2), 197–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1265575

- Botta, M. (2016). Competition policy: Safeguarding the Commission’s competences in state aid control. Journal of European Integration, 38(3), 265–278. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2016.1140156

- Buts, C., Jegers, M., & Joris, T. (2011). Determinants of the European Commission’s state aid decisions. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 11(4), 399–426. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-010-0091-0

- Carrubba, C. J. (2009). A model of the endogenous development of judicial institutions in federal and international systems. The Journal of Politics, 71(1), 55–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S002238160809004X

- Checkel, J. T. (2001). Why comply? Social learning and European identity change. International Organization, 55(3), 553–588. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/00208180152507551

- Cini, M. (2001). The soft law approach: Commission rule-making in the EU’s state aid regime. Journal of European Public Policy, 8(2), 192–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760110041541

- Cini, M., & McGowan, L. (2009). Competition policy in the European Union. Macmillan.

- Dilkova, P. Y. (2014). The new procedural regulation in state aid – whether “modernisation” is in the right direction? European Competition Law Review, 2014(2), 88–91.

- Doleys, T. J. (2013). Managing the dilemma of discretion: The European commission and the development of EU state aid policy. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 13(1), 23–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-012-0140-y

- Downs, G. W., Rocke, D. M., & Barsoom, P. N. (1996). Is the good news about compliance good news about cooperation? International Organization, 50(3), 379–406. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300033427

- Einardsson, K., & Kekelis, M. (2015). Time’s up: Procedural delays in state aid cases: An overview of the case law. European State Aid Law Quarterly, 14(1), 130–142.

- Eurobarometer. (2019). Standard Eurobarometer 2004–2018 [Data set]. https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Archive/index

- European Commission. (2005). State aid action plan: A roadmap for state aid reform 2005–2009.

- European Commission. (2012). EU state aid modernization (SAM).

- European Commission. (2013). State aid: Manual of procedures. Internal DG competition working document on procedures for the application of Articles 107 and 108.

- European Commission. (2020a). Task force tax planning practices. https://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/tax_rulings/index_en.html

- European Commission. (2020b). Commission adopts temporary framework to enable member states to further support he economy in the COVID-19 outbreak. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_496

- Finke, D. (2020). At loggerheads over state aid: Why the Commission rejects aid and governments comply. European Union Politics, 21(3), 474–496. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116520916248

- Fjelstul, J. C., & Carrubba, C. J. (2018). The politics of international oversight: Strategic monitoring and legal compliance in the European Union. American Political Science Review, 112(3), 429–445. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000096

- Franchino, F., & Mainenti, M. (2013). Electoral institutions and distributive policies in parliamentary systems: An application to state aid measures in EU countries. West European Politics, 36(3), 498–520. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.757081

- Franchino, F., & Mainenti, M. (2016). The electoral foundations to noncompliance: Addressing the puzzle of unlawful state aid in the European Union. Journal of Public Policy, 36(3), 407–436. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X15000343

- Halpin, P., & Humphries, C. (2016, September 6). Ireland to join Apple in fight against EU tax ruling. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eu-apple-taxavoidance-ireland-idUSKCN1180WR

- Hofmann, T. (2018). How long to compliance? Escalating infringement proceedings and the diminishing power of special interests. Journal of European Integration, 40(6), 785–801. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2018.1500564

- Hox, J. (2010). Multilevel analysis. Techniques and application. Routledge.

- Hurd, I. (1999). Legitimacy and authority in international politics. International Organization, 53(2), 379–408. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/002081899550913

- Jones, A., & Sufrin, B. (2016). EU competition law: Text, cases, and materials. Oxford University Press.

- Karagiannis, Y. (2010). Political analyses of European competition policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 17(4), 599–611. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501761003673633

- Kassim, H., & Lyons, B. (2013). The new political economy of EU state aid policy. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 13(1), 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-012-0142-9

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2010). The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5430.

- König, T., & Mäder, L. (2014). The strategic nature of compliance: An empirical evaluation of law implementation in the central monitoring system of the European Union. American Journal of Political Science, 58(1), 246–263. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12038

- Lowe, W., Benoit, K., Mikhaylov, S., & Laver, M. (2011). Scaling policy preferences from coded political texts. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 36(1), 123–155. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-9162.2010.00006.x

- Register. (2019). State aid register. https://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/register/

- Schmälter, J. (2018). A European response to non-compliance: The Commission’s enforcement efforts and the Common European Asylum System. West European Politics, 41(6), 1330–1353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2018.1427947

- Steunenberg, B. (2010). Is big brother watching? Commission oversight of the national implementation of EU directives. European Union Politics, 11(3), 359–380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116510369395

- Tallberg, J. (2002). Paths to compliance: Enforcement, management, and the European Union. International Organization, 56(3), 609–643. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/002081802760199908

- Thielemann, E. R. (1999). Institutional limits of a Europe with the regions: EC state-aid control meets German federalism. Journal of European Public Policy, 6(3), 399–418. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/135017699343595

- Volkens, A., Krause, W., Lehmann, P., Matthieß, T., Merz, N., Regel, S., & Weßels, B. (2018). Manifesto Project Dataset version 2018b [Data set].

- World Bank. (2019). World Bank world development indicators [Data set]. https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators

- Zahariadis, N. (2013). Winners and losers in EU state aid policy. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 13(1), 143–158. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-012-0143-8