ABSTRACT

This article reviews the literature on the institutional position of national parliaments in the EU. It focuses on new institutional developments, explanations, and effects discussed over the course of the last decade. Existing datasets on parliamentary oversight institutions in EU affairs and economic governance have been extended to 2020 to inform the discussion. A systematic overview of new analyses of the effects of oversight institutions in EU and domestic politics is offered as well. Cutting across the debate as to whether parliaments are multi-level or domestic players in the EU, this review concludes that the last decade has seen growing policy specialization in the institutional position of national parliaments at the European and national levels, and that the causes and consequences of this development remain largely unstudied.

Introduction

This article reviews the literature on the institutional position of national parliaments in the EU. It complements research on parliamentary behavior, which has received most attention recently (Auel et al., Citation2015b; Rauh & De Wilde, Citation2018; Senninger, Citation2017; Winzen et al., Citation2018), by highlighting important developments, analytical progress, and areas for further research regarding the formal role and rights of national parliaments in the EU. About a decade after the last review articles (Goetz & Meyer-Sahling, Citation2008; Raunio, Citation2009; Winzen, Citation2010) and data collections (Auel et al., Citation2015a; Karlas, Citation2011; Winzen, Citation2012), and following major integration crises, this is an appropriate moment to review and suggest next steps for this research agenda.

The following three sections respectively focus on developments in and explanations and effects of the institutional position of national parliaments. A decade ago, scholars called for more systematic data and analysis, and asked whether formal rules mattered at all. There has been significant progress regarding these concerns. In particular, new datasets on EU-related parliamentary rights and debates have been created and analyzed (Auel et al., Citation2015a; Rauh & De Wilde, Citation2018; Winzen, Citation2012), and use has been made of related data on outcomes such as position-taking and voting in the Council of Ministers or European Parliament. New questions have emerged as well. Most importantly, recent years have been characterized by growing policy specialization in national parliamentary institutions domestically and at the EU-level. This review provides new data on these developments, but open questions remain as to their explanations and consequences.

Institutional developments

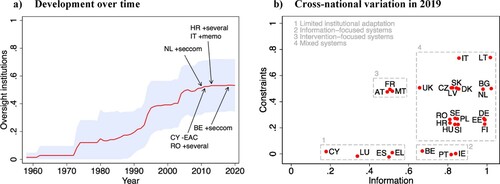

National parliaments’ institutional position has developed in the domestic arena and at the European level. Considering the domestic level first, it is known that parliaments rely on ‘oversight institutions’ to monitor EU affairs, gain information, and constrain and influence the government. shows the main institutions discussed in the literature. Scholars have noted increasing use of and cross-national convergence on these institutions (Buzogány, Citation2013; Jungar, Citation2010; Karlas, Citation2011; Raunio, Citation2009), although around 2010 significant variation remained (Auel et al., Citation2015a; Winzen, Citation2012). We can chart these institutions, individually or aggregated (see rules in ), for an empirically grounded discussion of recent developments. To this end, data in Winzen (Citation2012) have been extended to 2020, as explained in Appendix 1.

Table 1. Key parliamentary oversight institutions in EU affairs.

(a) shows long-term growth in oversight institutions. Since 2010, incremental reforms have strengthened sectoral committee involvement and information supply. Romania enacted a broader reform that had been delayed since accession. In 2013, the Croatian parliament followed other post-2004 member states by adopting strong oversight institutions (Jungar, Citation2010; Karlas, Citation2011). The only case of weakening stems from Cyprus combining the EAC and other committees. That several reforms strengthened sectoral committees accords with claims that EU scrutiny has become sectorally ‘mainstreamed’ (Gattermann et al., Citation2016), although institutionally this trend began in the 1990s (Winzen, Citation2012, p. 667).

Figure 1. Variation in parliamentary oversight institutions.

Note: Panel (a) charts the strength of oversight institutions over all member states (±one standard deviation). Panel (b) shows countries along dimensions of oversight institutions in 2019. Close dots have been separated for legibility but are identical. See the last row of Table 1 for measurement details.

Cross-national differences remain significant ((b)). Some parliaments do not go beyond basic committee structures. A second group emphasizes information and a third relies more on instruments to intervene in government position-taking. However, most parliaments have mixed systems and even this group varies. Hence, the popular distinction between ‘mandating’ and ‘document’ systems does not capture observed structures well (see also House of Commons, Citation2013, p. 14). Indeed, while groupings have heuristic value, the figure suggests that variation in oversight systems should generally be seen as gradual rather than categorical.

There have been changes not captured in these data. Parliaments have reacted to new rules of the Lisbon Treaty (Auel & Neuhold, Citation2017). Many parliaments have adjusted their rules to incorporate new opportunities for monitoring subsidiarity under the Early Warning Mechanism (e.g., Cooper, Citation2012; Malang et al., Citation2019; Miklin, Citation2017). Moreover, many parliaments now require that governments obtain approval before agreeing to simplified treaty revisions and transitions from unanimity to qualified majority voting under certain provisions of the Lisbon Treaty.

However, the main question in recent years has been whether national parliaments react to EU reforms of Economic and Monetary Union. de Wilde and Raunio (Citation2018) argue that parliaments should focus more on economic governance (see also Crum, Citation2018; Lord, Citation2017). Behavioral studies examine whether parliaments debate facets of economic governance (Hallerberg et al., Citation2018; Kreilinger, Citation2018; Maatsch, Citation2017; Rasmussen, Citation2018). To assess institutional adaptation, data on parliamentary rights in the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and the European Semester (ES), first presented in Rittberger and Winzen (Citation2015), have been extended to 2020 based on the scheme in in (see also Appendix 1).

Table 2. Parliamentary rights in the ESM and European Semester.

shows considerable variation in parliamentary rights in economic governance. About half of the Euro area parliaments have noteworthy formal rights in ESM decision-making, and half of all member state parliaments have some formal role in the European Semester. Only few parliaments, and only one outside of the Euro area, have instituted extensive monitoring of the European Semester. Yet, it should be kept in mind that some parliaments might deem existing oversight systems sufficient to accommodate economic governance. The Finish parliament, for example, explicitly refrained from reform for this reason (Kreilinger, Citation2018, p. 330).

Figure 2. Variation of parliamentary rights in economic governance in 2019.

Note: Updated from Rittberger and Winzen (Citation2015). The color scheme encodes the values in Table 2: Dark blue=1. Light blue=0.5. Red=0. Countries outside of the Euro area are listed separately starting with Denmark (DK).

In addition to domestic oversight, there have been developments at the European level. Already before 2010, interparliamentary meetings of Speakers, EACs, and other committees, and coordination for monitoring subsidiarity, and more generally the tentative emergence of a ‘field’ of interparliamentary relations had been highlighted (Cooper, Citation2006; Crum & Fossum, Citation2009). Yet, interparliamentary cooperation had remained informal and weak overall (Raunio, Citation2009). Since 2010, three new, policy-specific interparliamentary conferences have given greater formality to interparliamentary relations () (Cooper, Citation2016, Citation2017; Fromage, Citation2018; Hefftler & Gattermann, Citation2015; Herranz-Surrallés, Citation2014; Wouters & Raube, Citation2012). Except for the JPSG, which has stronger information rights and delegates an observer to the Europol board, these conferences’ competences are restricted to monitoring and debate. Interparliamentary cooperation has thus gained in institutionalization but not formal authority.

Table 3. New interparliamentary conferences.

Finally, in the shadow of the above developments, parliamentary bureaucracies have been strengthened in many countries and now also encompass officials based in Brussels (Högenauer et al., Citation2016; Högenauer & Neuhold, Citation2015; Neuhold & Högenauer, Citation2016). Parliamentary bureaucracies often select EU affairs priorities for parliamentary attention and thus occupy a potentially significant agenda-setting position. Recent studies have thus raised questions about intra-parliamentary delegation relationships, but systematic data on the organization of these relationships remains rare (Christiansen et al., Citation2014; Winzen, Citation2014).

Summing up, while variation in oversight institutions persists, the main trend of the past decade points towards more reliance on specialized expertise and policy-specific procedures – or what could be called ‘policy specialization’. With few exceptions, sectoral committees are partly or strongly involved in domestic oversight, special mechanisms for economic governance have emerged, and policy-specific interparliamentary conferences have been created. Specialized EU affairs bureaucracies have been reinforced to support these developments.

Explanations

Efforts to explain the institutional position of national parliaments in the EU often start by asking which parliamentary actors might be motivated and able to strengthen domestic oversight. A difficulty is that opposition parties might be motivated but unable whereas governing parties might be able but unmotivated to do so. One response is that the EU weakens oversight for majority parties and aggravates oversight problems under coalition and minority governments (Benz, Citation2004; Bergman, Citation2000; Saalfeld, Citation2005). Early studies also expect reforms where parliamentarians are accustomed to significant oversight rights and face pressure from Eurosceptic electorates (Benz, Citation2004; Dimitrakopoulos, Citation2001; Raunio, Citation2005).

Recent literature offers a new perspective. Parties are assumed to hold beliefs about the appropriate and democratic design of the EU (Jachtenfuchs et al., Citation1998) and consider the necessity of parliamentary reform against the background of these beliefs if the EU gains authority (Rittberger, Citation2003). Motivation for reform thus becomes independent of being in government or opposition, but instead depends on the ‘constitutional preferences’ of parties – in particular, on whether they deem national parliamentary oversight democratically necessary for the EU and whether they consider the empowerment of the EP sufficient to overcome democratic deficits (Winzen, Citation2017; Winzen et al., Citation2015). Pre-existing parliamentary rights, in this view, reflect past constitutional conflicts and preferences that have become shared across most parties (Dimitrakopoulos, Citation2001). Pre-existing rights, if codified constitutionally, could also be extended to EU affairs by courts rather than parties (Kiiver, Citation2010).

As Raunio (Citation2009) already observed, there is some convergence in the literature that existing parliamentary institutions and, if less consistently across studies, popular Euroscepticism are relevant explanatory factors. Recent studies highlight party positions in addition. Yet, comparing the importance of these factors remains ambiguous because operationalizations vary. This seems to reflect different timepoints at which studies were conducted (and thus variation in available data and approaches), lack of accepted data (e.g., on domestic parliamentary rights), and different ideas for measurement. In comparison to other areas of EU studies (and beyond), this is hardly unusual but still reminds us to aim for convergence not only in theory but also in measurement whenever reasonably possible.

There has also been renewed attention to similarity between parliaments. The diffusion of oversight institutions has been discussed for some time, but evidence had initially remained rare (Buzogány, Citation2013; Jungar, Citation2010; Raunio, Citation2009, p. 319). One recent study suggests that new member states and young democracies adopt oversight systems from culturally alike and successful parliaments (Bormann & Winzen, Citation2016). Senninger (Citation2020) argues that diffusion is likely if parliamentary majority parties share constitutional preferences, thus developing a more political argument compatible with the theoretical perspective above. In both studies, a ‘shortage’ of member states and institutional changes poses analytical challenges. Further research at the levels of parliamentarians and mechanisms might thus be desirable.

Analyses of parliamentary rights in economic governance are still rare. Rittberger and Winzen (Citation2015) find that ESM rights are lacking in parliaments with weak budget rights and EU oversight institutions. Institutional weakness in domestic and EU affairs thus seems to extend to this area. They find no explanation for European Semester adaptation, however. Kreilinger (Citation2018) and Maatsch (Citation2017) suggest that parliamentary rights in budget or EU matters are a prerequisite for parliamentary involvement in the European Semester. Rasmussen (Citation2018) concludes that pre-existing oversight institutions facilitate parliamentary involvement in the European Semester, while Euro area members are not more involved than outsiders. In contrast, Hallerberg et al. (Citation2018) find that Euro area membership matters. These studies examine a variety of institutional or behavioral outcomes, often in the early years of the European Semester, and cover various countries. More comparative and recent data might thus resolve some divergent findings. Given the salience of economic governance in recent years, party and popular Euroscepticism might also deserve further attention, although some of the above studies find mixed or no evidence (Hallerberg et al., Citation2018; Rittberger & Winzen, Citation2015).

Finally, what explains the emergence of interparliamentary conferences? The aims and competences of these conferences have remained modest due to interparliamentary disagreements. There is a link to arguments on constitutional preferences in that disagreement seems to reflect different preferences on the role of the EP and national parliaments in the EU (Cooper, Citation2016). Analyses of parliamentary debates, interviews, and contributions to COSAC further suggest that many parliamentarians consider domestic oversight and debate rather than interparliamentary cooperation their priority (Kinski, Citation2020; Raunio, Citation2011). It has also been argued that parliaments are least willing to strengthen interparliamentary conferences if they have domestic oversight rights already and salience is low – for example, if they are in a favorable macroeconomic position in the area of economic governance (Rittberger & Winzen, Citation2015). These studies share a focus on the competences of interparliamentary conferences but leave open why these conferences exist. In this respect, Herranz-Surrallés (Citation2014) considers the conference in CFSP a compromise – instead of empowerment of the EP or domestic oversight – between competing authority claims by the EP and national parliaments. Further tests of this or other arguments remain rare, however.

Overall, there has been significant progress in all strands of the literature. Across the literature, the question that appears to have remained most ambiguous is why different types of oversight institutions emerge. Within countries, most research focuses on the aggregate strength of oversight institutions, but we saw earlier that there are also different mixes of institutions. Similarly, why certain countries and not others create specific rights in economic governance (and only in economic governance) and why certain policy areas rather than others feature interparliamentary conferences remains unclear.

Some ways to address the above questions empirically seem relatively clear. First, future studies could disaggregate the dependent variable. Instead of aggregate measures of the strength of oversight institutions, it seems promising to focus on variation in specific institutions – e.g., the involvement of sectoral committees – or intermediary steps in the causal chain such as parliamentarians’ perceptions of institutional reform (as in some of the studies cited above). Second, in particular to explain the emergence of interparliamentary conferences or policy-specific domestic oversight, comparisons across policies seem promising. Which policy characteristics, possibly in interaction with domestic factors, explain (the absence of) institutional changes at the European level and in national parliaments?

Theoretically, these strategies might create leverage on existing and new explanations. For example, it has been argued that EU oversight institutions reflect existing institutions. Do we see sectoral committees closely involved or specialized parliamentary bureaucracies where these already existed? Moreover, the observation that parliaments create distinct domestic and European-level rules in some areas indicates that certain policy characteristics might matter. For example, interparliamentary conferences have evidently emerged in the EU’s core state policies (Genschel & Jachtenfuchs, Citation2014). This could be a decisive policy feature. Yet, it is less clear why interparliamentary conferences emerged long after the EU first obtained authority in core state policies. Finally, new developments such as interparliamentary conferences or parliamentary rights in economic governance constitute an opportunity to relate this literature to the far-flung debate on differentiated integration (Holzinger & Schimmelfennig, Citation2012). If parliaments are less exposed to EU authority because they have opted-out of the Euro area, internal security, or foreign and defense policies, does this influence their institutional preferences and reform choices?

Effects

Do oversight institutions and other parliamentary rights have effects on European and domestic politics? Formal rules and rights create opportunities for parliamentary actors and requirements for governments. Yet, since party politics and other factors are bound to influence the behavior of these actors strongly, scholars have long wondered whether formal rules really matter – and, if so, for which outcomes (e.g., Auel, Citation2007; Pollak & Slominski, Citation2003).

In the last decade, many relevant studies have appeared. To convey a systematic overview, Table A2 (Appendix 2) collates all journal publications until November 2020 that (1) cite Auel et al. (Citation2015a) or Winzen (Citation2012) and (2) examine the effects of oversight institutions.Footnote1 Among the 29 publications, three main groups exist. Eight studies examine governmental preferences, bargaining success, and voting as well as voting in the EP. Eight contributions focus on national parliamentary activities such as issuing resolutions or devoting time to EU documents. Finally, five articles examine parliamentary debate specifically. Other outcomes include implementation, opposition behavior, reasoned opinions, role perceptions, media coverage, and support for inter-parliamentary cooperation. Turning to the results of these studies, 14 report an effect of oversight institutions, eight find an effect but with some qualifications, and seven find no effect. The envisaged mechanisms vary but often indicate that strong institutions facilitate parliamentarians’ awareness of EU policymaking. For example, Hagemann et al. (Citation2019) suggest that parliaments with strong oversight procedures might notice ‘no’ votes in the Council, which motivates governments to cast such votes. Auel et al. (Citation2015b) argue that strong rights ‘facilitate’ various activities in EU affairs. Winzen et al. (Citation2018) claim that strong rights mean that parliamentarians regularly receive information and thus pay attention to EU affairs. For the media, institutionally strong parliaments might also appear more relevant (Auel et al., Citation2018). More discussion than possible here, would certainly be desirable. Yet, clearly, the literature now offers a better sense than a decade ago of the effects oversight institutions might have theoretically – and some reason for confidence that some of these effects do in fact exist.

It is likely that research in the above areas will continue to appear. In addition, two new areas of interest in the study of the effects of parliamentary rights in the EU can be identified. First, we still know little about the implications of recent institutional developments – that is, parliamentary adaptation to economic governance and the emergence of interparliamentary conferences. The consequences of different mixes of domestic oversight institutions also remain largely unstudied. Second, of the 29 studies almost all examine parties, parliaments, or governments rather than parliamentarians. This could be an unused opportunity. Oversight institutions and interparliamentary conferences might have the strongest effects at the individual level by shaping the information, and policy and political beliefs of the actors involved.

In particular, studies at the individual level promise analytical opportunities that are not readily available at more aggregate levels. Drawing for example on parliamentary speech, new outcomes of interest could be conceptualized and measured such as legitimacy beliefs, the informational and deliberative quality of speeches, or degrees of support or opposition to the government. Large literatures in legislative studies and some studies cited here already offer practical tools. For scholars interested in the effect of parliamentary institutions in EU affairs, these new outcomes open up new research design opportunities. For example, do parliamentarians’ legitimacy beliefs change depending on participation in interparliamentary conferences, EU affairs committees, or sectoral committees with varying formal roles in EU affairs? How do outcomes for these parliamentarians differ from others who are not or less involved in EU oversight institutions at the national or European level?

Conclusion

Recent years have seen debate about whether national parliaments are becoming ‘multi-arena’ actors, remain focused on domestic oversight, or turn towards interparliamentary cooperation (Auel & Neuhold, Citation2017; Kinski, Citation2020; Raunio, Citation2011). This review highlights an institutional trend that crosscuts these alternatives. The last ten years have been characterized by growing policy specialization in the institutional position of national parliaments (see also Gattermann et al., Citation2016). Oversight institutions in EU affairs have developed in this direction, special rights in economic governance have emerged, and policy-specific interparliamentary conferences have been created. Specialized bureaucracies have grown in parallel. How we might explain these developments, and what effects they might have at the EU and domestic levels, remains open to debate.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (121.1 KB)Acknowledgements

For insightful comments, I thank Roman Senninger.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Thomas Winzen

Thomas Winzen is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Government of the University of Essex.

Notes

1 These two articles have been chosen because they are linked to the two most commonly used data sources – one was introduced above and the other is a cross-sectional dataset collected by the OPAL project around 2010-12. It focuses on parliamentary behavior, but also includes information on national parliaments’ institutional rights.

References

- Auel, K. (2007). Democratic accountability and national parliaments: Redefining the impact of parliamentary scrutiny in EU affairs. European Law Journal, 13(4), 487–504. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0386.2007.00380.x

- Auel, K., Eisele, O., & Kinski, L. (2018). What happens in parliament stays in parliament? Newspaper coverage of national parliaments in EU affairs. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(3), 628–645. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12685

- Auel, K., & Neuhold, C. (2017). Multi-arena players in the making? Conceptualizing the role of national parliaments since the Lisbon treaty. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(10), 1547–1561. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1228694

- Auel, K., Rozenberg, O., & Tacea, A. (2015a). Fighting back? And, if so, how? Measuring parliamentary strength and activity in EU affairs. In C. Hefftler, C. Neuhold, O. Rozenberg, J. Smith, & W. Wessels (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of National Parliaments and the European Union (pp. 60–93). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Auel, K., Rozenberg, O., & Tacea, A. (2015b). To scrutinise or not to scrutinise? Explaining variation in EU-related activities in national parliaments. West European Politics, 38(2), 282–304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.990695

- Benz, A. (2004). Path-dependent institutions and strategic veto players: National parliaments in the European Union. West European Politics, 27(5), 875–900. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0140238042000283283

- Bergman, T. (2000). The European Union as the next step of delegation and accountability. European Journal of Political Research, 37(3), 415–429. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00520

- Bormann, N.-C., & Winzen, T. (2016). The contingent diffusion of parliamentary oversight institutions in the European Union. European Journal of Political Research, 55(3), 589–608. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12149

- Buzogány, A. (2013). Learning from the best? Interparliamentary networks and the parliamentary scrutiny of EU decision-making. In B. Crum & J. E. Fossum (Eds.), Practices of inter-parliamentary coordination in international politics (pp. 17–32). ECPR Press.

- Christiansen, T., Hogenauer, A.-L., & Neuhold, C. (2014). National parliaments in the post-Lisbon European Union: Bureaucratization rather than democratization? Comparative European Politics, 12(2), 121–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2012.38

- Cooper, I. (2006). The watchdogs of subsidiarity: National parliaments and the logic of arguing in the EU. Journal of Common Market Studies, 44(2), 281–304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2006.00623.x

- Cooper, I. (2012). A “virtual third chamber” for the European Union? National parliaments after the Treaty of Lisbon. West European Politics, 35(3), 441–465. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.665735

- Cooper, I. (2016). The politicization of interparliamentary relations in the EU: Constructing and contesting the “article 13 conference” on economic governance. Comparative European Politics, 14(2), 196–214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2015.37

- Cooper, I. (2017). The emerging order of interparliamentary cooperation in the post-Lisbon EU. In D. Jancic (Ed.), National Parliaments After the Lisbon Treaty and the Euro Crisis (pp. 227–246). Oxford University Press.

- Crum, B. (2018). Parliamentary accountability in multilevel governance: What role for parliaments in post-crisis EU economic governance? Journal of European Public Policy, 25(2), 268–286. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1363270

- Crum, B., & Fossum, J. E. (2009). The Multilevel parliamentary field: A framework for theorizing representative democracy in the EU. European Political Science Review, 1(2), 249–271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773909000186

- de Wilde, P., & Raunio, T. (2018). Redirecting national parliaments: Setting priorities for involvement in EU affairs. Comparative European Politics, 16(2), 310–329. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2015.28

- Dimitrakopoulos, D. G. (2001). Incrementalism and path dependence: European integration and institutional change in national parliaments. Journal of Common Market Studies, 39(3), 405–422. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00296

- Fromage, D. (2018). A comparison of existing forums for interparliamentary cooperation in the EU and some lessons for the future. Perspectives on Federalism, 10(3), 1–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2478/pof-2018-0029

- Gattermann, K., Högenauer, A.-L., & Huff, A. (2016). Studying a new phase of europeanisation of national parliaments. European Political Science, 15(1), 89–107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/eps.2015.56

- Genschel, P., & Jachtenfuchs, M. (2014). Beyond the regulatory polity? The European integration of core state powers. Oxford University Press.

- Goetz, K. H., & Meyer-Sahling, J.-H. (2008). The Europeanisation of national political systems: Parliaments and executives. Living Reviews in European Governance, 3(2). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12942/lreg-2008-2

- Hagemann, S., Bailer, S., & Herzog, A. (2019). Signals to their parliaments? Governments’ use of votes and policy statements in the EU council. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 57(3), 634–650. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12844

- Hallerberg, M., Marzinotto, B., & Wolff, G. B. (2018). Explaining the evolving role of ational parliaments under the European semester. Journal of European Public Policy, 25(2), 250–267. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1363273

- Hefftler, C., & Gattermann, K. (2015). Interparliamentary cooperation in the European Union: Patterns, problems and potential. In C. Hefftler, C. Neuhold, O. Rozenberg, & J. Smith (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of National Parliaments and the European Union (pp. 94–115). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Herranz-Surrallés, A. (2014). The EU’s multilevel parliamentary (battle)field: Inter-parliamentary cooperation and conflict in foreign and security policy. West European Politics, 37(5), 957–975. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.884755

- Högenauer, A.-L., & Neuhold, C. (2015). National parliaments after Lisbon: Administrations on the rise? West European Politics, 38(2), 335–354. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2014.990698

- Högenauer, A.-L., Neuhold, C., & Christiansen, T. (2016). Parliamentary Administrations in the European Union. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Holzinger, K., & Schimmelfennig, F. (2012). Differentiated integration in the European Union: Many concepts, sparse theory, few data. Journal of European Public Policy, 19(2), 292–305. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2012.641747

- House of Commons. (2013). Reforming the European Scrutiny System in the House of Commons. Twenty-fourth Report of Session 2013-14. Retrieved November 2020. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201314/cmselect/cmeuleg/109/109.pdf.

- Jachtenfuchs, M., Diez, T., & Jung, S. (1998). Which Europe? Conflicting models of a legitimate European political order. European Journal of International Relations, 4(4), 409–445. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066198004004002

- Jungar, A.-C. (2010). The choice of parliamentary EU scrutiny mechanisms in the new member states. In B. Jacobsson (Ed.), The European Union and the Baltic States (pp. 121–143). Routledge.

- Karlas, J. (2011). Parliamentary control of EU affairs in central and Eastern Europe: Explaining the variation. Journal of European Public Policy, 18(2), 258–273. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.544507

- Kiiver, P. (2010). The Lisbon judgment of the German constitutional court: A court-ordered strengthening of the national legislature in the EU: European Law Journal. European Law Journal, 16(5), 578–588. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0386.2010.00523.x

- Kinski, L. (2020). What role for national parliaments in EU governance? A view by members of parliament. Journal of European Integration, 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1817000

- Kreilinger, V. (2018). Scrutinising the European Semester in national parliaments: What are the drivers of parliamentary involvement? Journal of European Integration, 40(3), 325–340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2018.1450402

- Lord, C. (2017). How can parliaments contribute to the legitimacy of the European semester? Parliamentary Affairs, 70(4), 673–690. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsx017

- Maatsch, A. (2017). Effectiveness of the European Semester: Explaining domestic consent and contestation. Parliamentary Affairs, 70(4), 691–709. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsx021

- Malang, T., Brandenberger, L., & Leifeld, P. (2019). Networks and social influence in European legislative politics. British Journal of Political Science, 49(4), 1475–1498. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123417000217

- Miklin, E. (2017). Beyond subsidiarity: The indirect effect of the early warning system on national parliamentary scrutiny in European Union affairs. Journal of European Public Policy, 24(3), 366–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1146323

- Neuhold, C., & Högenauer, A.-L. (2016). An information network of officials? Dissecting the role and nature of the network of parliamentary representatives in the European Parliament. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 22(2), 237–256. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2016.1163884

- Pollak, J., & Slominski, P. (2003). Influencing EU politics? The case of the Austrian parliament. Journal of Common Market Studies, 41(4), 707–729. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00442

- Rasmussen, M. B. (2018). Accountability challenges in EU economic governance? Parliamentary scrutiny of the European semester. Journal of European Integration, 40(3), 341–357. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2018.1451523

- Rauh, C., & De Wilde, P. (2018). The opposition deficit in EU accountability: Evidence from over 20 years of plenary debate in four member states. European Journal of Political Research, 57(1), 194–216. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12222

- Raunio, T. (2005). Holding governments accountable in European affairs: Explaining cross-national variation. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 11(3–4), 319–342. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13572330500348307

- Raunio, T. (2009). National parliaments and European Integration: What we know and agenda for future research. The Journal of Legislative Studies, 15(4), 317–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13572330903302430

- Raunio, T. (2011). The gatekeepers of European integration? The functions of national parliaments in the EU political system. Journal of European Integration, 33(3), 303–321. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2010.546848

- Rittberger, B. (2003). The creation and empowerment of the European parliament. Journal of Common Market Studies, 41(2), 203–225. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00419

- Rittberger, B., & Winzen, T. (2015). Parlamentarismus nach der Krise: Die Vertiefung parlamentarischer Asymmetrie in der reformierten Wirtschafts- und Währungsunion. Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 56(3), 430–456. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5771/0032-3470-2015-3-430

- Saalfeld, T. (2005). Deliberate delegation or abdication? Government backbenchers, ministers and European Union legislation. Journal of Legislative Studies, 11(3-4), 343–371. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13572330500273547

- Senninger, R. (2017). Issue expansion and selective scrutiny – how opposition parties used parliamentary questions about the European Union in the national arena from 1973 to 2013. European Union Politics, 18(2), 283–306. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116516662155

- Senninger, R. (2020). Institutional change in parliament through cross-border partisan emulation. West European Politics, 43(1), 203–224. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2019.1578095

- Winzen, T. (2010). Political integration and national parliaments in Europe. Living Reviews in Democracy. Online article (cited 04/01/2011): http://www.livingreviews.org/lrd-2010-5.

- Winzen, T. (2012). National parliamentary control of European Union affairs: A cross-national and longitudinal comparison. West European Politics, 35(3), 657–672. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2012.665745

- Winzen, T. (2014). Bureaucracy and democracy: Intra-parliamentary delegation in European Union affairs. Journal of European Integration, 36(7), 677–695. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2014.944180

- Winzen, T. (2017). Constitutional Preferences and Parliamentary Reform: Explaining National Parliaments’ Adaptation to European Integration. Oxford University Press.

- Winzen, T., de Ruiter, R., & Rocabert, J. (2018). Is parliamentary attention to the EU strongest when it is needed the most? National parliaments and the selective debate of EU policies. European Union Politics, 19(3), 481–501. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116518763281

- Winzen, T., Roederer-Rynning, C., & Schimmelfennig, F. (2015). Parliamentary co-evolution: National parliamentary reactions to the empowerment of the European parliament. Journal of European Public Policy, 22(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2014.881415

- Wouters, J., & Raube, K. (2012). Seeking CSDP accountability through interparliamentary scrutiny. The International Spectator, 47(4), 149–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2012.733219