ABSTRACT

In the past decade, policy-making around the world has increased its attention to behavioural insights (BI). The European Commission (EC) identified this trend early on and has incorporated BI to its policy-making over several years. However, this experience has not been formally documented, or systematically analysed, from a policy studies perspective, leaving a large amount of experience-based knowledge on behavioural governance untapped. Our contribution aims at closing this gap, clarifying the practices by which BI are gaining epistemic authority and contributing to the European Union's (EU) policy instruments. This paper presents the evolution of BI thinking inside the EC, illustrates how BI are introduced in the policy cycle, and explores future challenges to and opportunities for mainstreaming BI at every level and stage of policy-making in the EU.

1. Introduction

Policy-making around the world is paying increasing attention to behavioural insights (BI). Contributions from cognitive psychology, anthropology, social psychology, behavioural economics, sociology and other behavioural sciences are reshaping public policy interventions and debates in a number of policy fields. From health to environmental issues, from labour to consumers, from financial instruments to agriculture, more and more policy programmes are designed keeping BI in mind. This was however a gradual process for policy-making, with many examples of early adoption across the world in the early 2000s (Afif et al., Citation2019). For example, the first formal and publicly known case, now emblematic of an era, was the recruitment of Cass Sunstein as the head of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) in 2009. The following year, the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) was created in the UK Cabinet Office. Currently the BIT is a global social purpose company with offices around the globe and over 750 projects under their belt. That experience paved the way for many other national behavioural units, in the United States, Canada, Australia, Netherlands, Austria, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, India, Indonesia, Peru, and Singapore. Many countries have created BI groups and units, while others have similar projects in the pipeline. The same approach has been followed by international institutions, such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World Bank, and agencies of the United Nations, notably the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF).

The European Commission (EC), with the Joint Research Centre (JRC, the EC's science and knowledge service), embraced this trend early on, supporting and informing EC services intending to apply this approach. This effort eventually led to the creation of a dedicated team at the JRC, the Competence Centre on Behavioural Insights.

Whereas much is known about the functioning and evidence produced by some behavioural teams across the world (Della Vigna & Linos, Citation2020; Halpern, Citation2016), less up-to-date information is available about the application of BI within the EC. Having been involved in this process inside the EC since the start, we aim at filling this gap in the literature. What follows is a subjective perspective that takes stock of what has been achieved, placing it in a broader context, while being reflective and self-critical at the same time. Section 2 positions the paper, and the way BI are applied to policy-making at the EC, in relation to existing work in this field. Section 3 describes how BI became increasingly present across policy areas. It does so by breaking this process down in three different phases – exploration, development and consolidation – and providing a selection of examples. Section 4 clarifies how BI apply to the different phases of the policy process, in particular within the Better Regulation framework. Finally, section 5 takes a forward-looking perspective and tackles future challenges and opportunities. Section 6 concludes.

2. The European Commission's approach in context

BI's prominence in policy-making has created many expectations, but has also raised some concerns. One of them is that the role of the state as a behavioural change agent may have a depoliticising effect (Leggett, Citation2014). Nudging, for one, does not explicitly address inequality and the distribution of wealth (Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2008). Moreover, BI present citizens as fallible, which could undermine their role as empowered and deliberative agents in a democracy.

These concerns do not apply to the way the EC seeks to incorporate BI. Instead of becoming another behavioural change agent, the EC seeks to improve people's lives through regulation informed by BI. This too shapes people's behaviour and attitudes, but it is more of a shove than a nudge (Leggett, Citation2014). BI have helped identify problems with how people process financial information, for example, leading to standards on how it should be presented. These changes can be long lasting, unlike nudges whose effect can wane after time due to e.g. habituation.

The EC also uses BI to protect citizens against attempts by third parties at shaping behaviour to their own advantage (budging; Oliver, Citation2015). The choice architecture is seldom neutral and often reflects the activity of commercial actors wanting consumers’ attention and money. The state is the only actor that can legitimately push back against powerful corporate behaviour change seekers, through regulation (Leggett, Citation2014). BI may play a role in designing the regulatory instruments or in helping identify the questionable private sector practices that need attention.

BI can also help evaluate the long-term behavioural effects of EC policies, and possibly anticipate them. This is especially relevant in some policy areas such as the labour market, fiscal policy, environmental protection, and health, where shared attitudes and social norms can have a significant impact on behaviour. For example, do gender-based quotas change attitudes towards women in the workplace? What would happen if they were removed? This is a prospective assessment that is worth making.

Another concern is the relationship between the behavioural turn in policy-making and free market economics. Some see BI as a vehicle for extending neoliberalism. A popular claim is that, for all its opposition to standard economic theory, which has contributed to its success (Berndt, Citation2015), BI supports the orthodoxies of the free market (Whitehead et al., Citation2017). Theoretically, it shifts attention away from market failure to behavioural failure – i.e., markets could work well if people's behaviour was different (Leggett, Citation2014). BI may imply a reduced role for the state and greater responsibility on people for their own well-being (neoliberal governmentality; Carter, Citation2015). As such, it appears to be an attack on the welfare state (Jones et al., Citation2010).

However, this claim is overstated. In line with a behaviouralist approach to neuroliberal forms of government (Whitehead et al., Citation2017), the EC considers BI as simply another tool available to policy-makers. It is convinced that a sustained dialogue between the behavioural sciences and policy-making can lead to better policies. BI offer effective diagnoses and pragmatic solutions to policy problems, and their application need not assume serious political implications about the role of the state or the merits of the free market. Applying BI simply means drawing on evidence from the behavioural sciences to shed light on issues that previously did not have this empirical underpinning.

Incorporating BI into EC policy-making is part of a rationalist tradition that believes in the potential of science to address many social problems, and adheres to formal notions such as the policy cycle. At the same time, it resonates with an incrementalist tradition, and realises that there is an art to bringing evidence into policy-making (Feitsma, Citation2020). It is a process that seeks the highest level of rigour in the science that underpins policies, but acknowledges that there is a knowledge brokerage aspect to the task as well. The rationalist narrative provides the frontstage, while the actual process of feeding behavioural science to policy-making occurs in the backstage (Feitsma, Citation2019). This article includes both perspectives in an attempt to provide a full picture.

3. The evolution of behavioural insights thinking inside the European Commission

In the beginning was the pledge, and the pledge was for consumers, and consumers were the ultimate authority. In other words, at the onset, the rationale for BI in European policy-making was to better understand consumer behaviour.

At European level, the first implicit attempts of incorporating BI in policy-making were cases of debiasing through law. The right of withdrawal, found in much of the EU consumer acquis, and the health claims proposal are two early examples (Ciriolo, Citation2011; Frank & Purnhagen, Citation2015). The right of withdrawal – or cooling-off period, i.e., the time span during which customers have an unconditional right to cancel the contract – is a remedy to avoid consumer regrets due to myopia or impulse buying (EC, Citation1997). Similarly, Regulation N° 1924/2006 lays down harmonised rules for the use of health or nutritional claims (such as ‘low fat’, ‘high fibre’ and ‘helps lower cholesterol’) on foodstuffs based on nutrient profiles (EC, Citation2006). This relates intrinsically to the framing effect or bias, in this case consisting of misleading information based on an artificial reference point (a 20% fat cheese was often packaged as 80% fat-free). Notwithstanding the novelty of such cases, these fall within the category of behaviourally-aligned initiatives (see Lourenço et al., Citation2016), and explicit recognition of BI and collection of ad hoc behavioural evidence to inform policy initiatives had not yet seen the light.

In 2007, a newly appointed Commissioner for Consumer Protection, Meglena Kouneva, embraced the idea that a better understanding of consumer behaviour was a sine qua non condition to design more effective consumer policies. In the same year, former EC's Directorate-General for Health and Consumer Protection (DG SANCO) recruited a behavioural economist and gradually started to apply behavioural evidence explicitly in policy-making. A posteriori, one can identify three sequential phases in this process: an exploratory phase, a development phase and a consolidation phase. In what follows, we provide a description of each of them, also indicating some key milestones.

3.1. An exploratory phase (2007–2011)

At the turn of the century, the EU witnessed a deepening of market integration and a concomitant liberalisation of network industries (mainly energy and telecom). If such developments were expected to generate growth and jobs, they also required an active demand side, with confident and empowered consumers (EC, Citation1992). With a significant widening of choice (of providers and tariff schemes) and increasingly complex information, the very concept of ‘average consumer’ came to be challenged (Howells, Citation2005; Incardona & Poncibò, Citation2007). By this time, it was clear that consumer preferences were not just revealed (one of the postulates of microeconomics) but instead influenced by the choice context (see Ariely et al., Citation2003).Footnote1 In addition, significant academic developments and the 2007–2008 financial crisis called for a change in the mainstream analytical framework, and gave further impetus to BI. Simply put, market bubbles would not happen if economic agents were rational and asset prices were always ‘right’ (Thaler, Citation2009). The crisis, on the contrary, proved that even the most informed, competent and aware investors failed to make optimal choices, and displayed some kind of bounded rationality (Taleb, Citation2010).

In this context, the EC became conscious that a reality check was needed, and that this could come from behavioural evidence. From a policy perspective, relying on unrealistic, or at least partial, assumptions about people's behaviour may have severe consequences. If people's suboptimal choices are due to lack of knowledge or information, then conventional education or information campaigns could constitute an appropriate remedy. On the other hand, if people's behaviour reflects fundamental aspects of human nature (such as default bias, present bias, loss aversion, overconfidence, etc.), a better approach would require considering biases when designing policies.

At first, behavioural evidence was collected to inform solutions to problems related to consumers, as well as competition policy. More specifically, the work on consumer policy consisted in informing the EC Proposal for the Directive on Consumer Rights (EC, Citation2008), while the work on competition policy touched upon the apparent abuse of a dominant position in the web browsers market. Even back in 2008, there was ample evidence on the impact of defaults.Footnote2 Such evidence was submitted to a team of lawyers working in former DG SANCO. This eventually resulted in Article 22 of the Consumer Rights Directive, adopted by the European Union in 2011, and entered into force in 2014 (EC, Citation2011). Article 22 limits the use of default options in consumer contracts, insofar as it requires sellers to obtain express consent from consumers for any payment that is in addition to the payment for the main contractual obligation. This protected EU consumers from practices such as the abuse of pre-checked boxes for ancillary services (e.g., travel insurance when buying an airline ticket). In Commissioner Kuneva's words, it ensured that consumers’ money stayed by default in their pockets, unless they decided otherwise (Kuneva, Citation2008).

In the same years, the Directorate-General for Competition (DG COMP) also paved the way for a novel policy approach, using behavioural evidence to solve competition cases. The European antitrust interventions had traditionally relied on heavy fines to remove barriers to free trade and competition (e.g., the case of Media PlayerFootnote3). In 2008, various web browsers raised the same concern with respect to Internet Explorer (IE). This time around, however, DG COMP decided to explore the possibility to increase competition by tapping on the demand side. The result of such an approach came to be known as the ‘IE ballot box’, an update for all Windows users, giving them the chance to download, install and use a different browser. This information-based intervention embodied various elements designed to avoid choice overload, loss aversion and primacy bias.

These first relatively successful policy applications of BI at European level constituted the cornerstone of subsequent activities. Aside from hosting two international conferences (2008 and 2010), a first behavioural study was carried out to investigate consumers’ decision making in retail investment services in 2010. This study, based on three experiments (two online and one in the lab), was to inform the review of the Packaged Retail Investment Products (PRIPs) regulation. Results pointed to the effectiveness of simplification and standardisation for more comparable product information and ultimately better choices (EC, Citation2010).

3.2. A development phase (2012–2015)

The EC was an early starter with respect to other international organisations, and even national governments. However, the first two policy applications of behavioural evidence showed that a system to collect appropriate behavioural data was needed. To compensate for limited internal resources, the EC started to approach external partners – through public procurement procedures – to collect, analyse and interpret behavioural data.

This phase saw the execution of compelling research, such as the study on behaviour around tobacco – which informed the Tobacco Products Directive, (EC, Citation2014a) – and the study on online gambling – which informed the Recommendation on Online Gambling (EC, Citation2014b). Between 2012 and 2015, BI started to be increasingly considered and valued in policy-making. Within the EC, the resources allocated to foster this approach kept growing, as did the popularity of BI. Correspondingly, the JRC increased its involvement in this field, and started to conduct research in various fields such as taxation, health, social norms and digital privacy, to name but a few. This phase led to some prominent scientific work in support of policy and was crucial to structurally introduce BI in the EC. However, the overall approach needed to be further consolidated and a more ambitious project was envisioned.

3.3. A consolidation phase (2016-present)

In 2015 the EC boasted significant behavioural capacity, counting nine behavioural experts in the JRC (spread out over two different sites, Ispra and Seville), and one working in former DG SANCO. Such dispersion of capacity constituted a challenge and hindered the growth of a structured and systematic approach in the application of BI to EU policy-making. The growth in the demand for behavioural evidence across the EC called for a coordinated strategy.

By 2016, a newly created Unit for Foresight and Behavioural Insights at the JRC came to host all EC behavioural capacity. In parallel, an ambitious project was launched to review a wealth of policy initiatives – across 32 European countries – which were either implicitly or explicitly informed by BI (Lourenço et al., Citation2016). The publication of this report marked the beginning of a new consolidation phase. A set of objectives explicitly laid out in the report itself recognised that:

there was growing appetite to apply BI to policy-making at European level, and that a proper strategy should be adopted;

the links between policy-making and academic communities should be strengthened;

a systematic application of BI throughout the policy cycle could advance evidence-based policy-making; and

there was a need for more research on the long-term impacts of policy interventions.

Each of these objectives was pursued in the years that followed the publication of the report. First, new projects were launched in untapped policy fields proving the value of BI, for example in gender policy. This stream of work aimed at delivering better value for money to the EC co-funding of local gender initiatives to combat gender stereotypes, gender discrimination and gender violence. EC funding used to be bestowed paying more attention to the output to be generated (e.g., volume of printed brochures, number of awareness campaigns, etc.) than to the outcome to be observed (i.e., the actual impact of the proposed interventions). This approach was ill suited, as the EC and local stakeholders could not find out what worked and what did not, nor could they acquire a proper understanding of the best policy measure for each specific target group. The application of BI implied a more thorough design of gender policy initiatives, with a clear description of target groups in project proposals, a precise identification of policy measures and expected outcome for each target group. Consequently, the evaluation of the proposals submitted in the related calls reflected this new focus (Almeida et al., Citation2017) and paved the way to a new approach named ‘better spending’.

Previous collaborations also indicated that the call for behavioural evidence came late in the policy process, at a stage when it was sometimes difficult to provide timely support. In parallel, interaction with colleagues highlighted the need to build some basic capacity around BI across the EC, also to guarantee the acquisition of a common vocabulary. This specific need was met with the launch of a quarterly two-day training session on BI, which is up and running since early 2017.

Behavioural economics increasingly becoming mainstream – as evidenced by the Nobel Prize for Economics to Thaler in 2017, and then to Banjeree, Duflo and Kremer in 2019 – further favoured the uptake of behavioural evidence in policy cycles. This led to increased demand for training and specific support to EC services (as documented in the next sections). Simultaneously, this trend justified more resources. This whole process culminated in 2019 with the establishment of the more autonomous Competence Centre on Behavioural Insights (CCBI) at the JRC.

4. Integrating behavioural insights in the EC policy-making process

Today at the EC, BI are clearly present in policy-making. They are embedded in the policy cycle, attempting to improve the overall quality of EU policy instruments. They are incorporated into policy discussions at all levels, from bilateral meetings between Directors-General to everyday meetings of policy officers by the water cooler. More formally, they are included in the Better Regulations guidelines, a set of principles and practices for preparing, implementing and evaluating policies, measures and financial programmes.

BI are popular at the EC because they are appealing and intuitive, but also because the JRC has made a concerted effort to promote their application. This approach is somewhat different to that of specialised BI teams in the so-called Anglo-Saxon tradition (Feitsma, Citation2019). Applying BI to national, regional or local governance does not necessarily transpose to a supranational regulating body like the EU. There are differences in areas of competence (subsidiarity only allows the EU to focus on policy issues where a joint EU approach is warranted), policy instruments (the EU produces regulation, albeit at varying degrees of prescription), and proximity to the citizen (the EU being typically furthest removed).

4.1. BI in the policy cycle

Adopting BI in policy-making implies questioning the assumption that human behaviour is rational, explicit in economics and implicit in much of policy thinking. Policies designed expecting rational behaviour may fail to meet their objectives. Instead, the assumption of rationality needs to be replaced with embedded systematic departures from the rationality paradigm. Policies also need to take into account evidence of how individuals and societies are likely to react to an intervention. A more comprehensive understanding of human behaviour, and the formal inclusion of BI in policy-making, can therefore improve policy outcomes. This is captured in the literature as responsive behavioural regulation (Purnhagen, Citation2015) and is in line with a behaviouralist approach (Whitehead et al., Citation2017).

However, the process of bringing behavioural evidence to policy-making is not straightforward and value-free. It is simply not the case that the right scientific evidence will find its way into the right hands and have an impact on policy. For one, policy-makers are subject to biases as well (Feitsma, Citation2018). Moreover, there is a political dimension to this process, where stakeholders compete to achieve influence. Here, evidence is ammunition.

Policy-makers could rely on a number of practices to obtain the evidence they want. They could cherry-pick the favourable pieces of evidence and discredit the unfavourable ones. They could pressure researchers into providing favourable evidence and put constraints on those who provide unfavourable evidence (Ingold & Monaghan, Citation2016). To avoid these practices, the EC has formal guidelines and procedures, open to public scrutiny, in order to ensure due process. It also can count on the JRC to provide independent scientific advice and support to EU policy.

This is the background for the Better Regulation framework. This initiative was launched under the Juncker Commission in 2015 and is currently undergoing a process of review and stock-taking.Footnote4 The main objective of the better regulation system is to commit to evidence-based policy-making, through guidelines and a toolbox, as well as increasing participatory processes. More formally, the Better Regulation framework states that political decisions should be prepared in an open, transparent, manner, informed by the best available evidence and backed by the involvement of stakeholders. This approach increases trust in government in general and in behavioural public policy in particular (Sunstein et al., Citation2019). It lies at the heart of evidence-based policy-making.

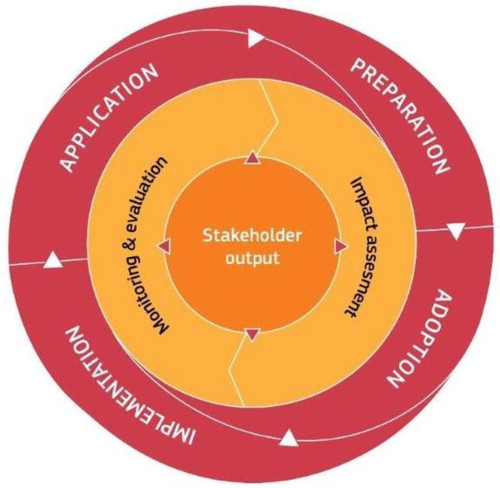

If applying BI to policy-making in the EU is a case of rationalised incrementalism, adhering the notion of a policy cycle corresponds to the ‘rationalist’ part (Feitsma, Citation2020). According to the Better Regulations framework, the policy cycle consists of six closely interrelated phases: policy design and preparation, adoption, impact assessment, implementation, application, and monitoring and evaluation (). For each phase of this cycle, there are a number of better regulation principles, objectives, and procedures to make sure that the EU has the best policy possible, while avoiding unnecessary burdens and bureaucratic complications. In practical terms, these are formulated in a set of guidelines, supported by a set of tools. The main guidelines set out mandatory requirements and obligations for each step in the policy cycle, while the toolbox provides additional guidance, generally not binding. More in detail, the guidelines help in preparing new initiatives and proposals, and manage existing policies and legislation.Footnote5

In theory, BI have the potential to contribute to all phases (Troussard & van Bavel, Citation2018). They can help identify and understand the policy problem at the preparation phase. In addition, they can contribute to policy options at the adoption, implementation and application phases. In practice, however, the Better Regulations guidelines mainly include BI in the impact assessment (IA) process. This process is about gathering and analysing evidence to support policy-making. First, it verifies the existence of a problem, identifies its underlying causes, assesses whether EU action is needed, and analyses the advantages and disadvantages of available solutions. A properly delivered IA promotes more informed decision-making and contributes to better regulation. This should deliver the full benefits of policies at minimum cost, while respecting the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality.

The Better Regulations guidelines suggest a four-step approach for EU policy officers wishing to apply BI to the IA process. These are the key sequential actions for successfully applying a behavioural approach to policy-making:

Identify the relevant behaviour. For a behavioural approach to bear fruit there must be a behavioural element to the policy problem. Policy officers should identify it with precision and analyse how it is relevant to the policy problem. Do they want to change it or just understand it better? Not all policy problems have a behavioural element, so this step is key in determining whether BI can add value or not.

Understand the behaviour. This step implies an empirical component of some sort. Either through literature review or first-hand data collection, policy officers should seek the underlying cause of people's behaviour.Footnote6 For example, are they exhibiting some inherent cognitive bias or are external factors influencing them? A better understanding of behaviour will allow policy to address it more effectively.

Design policy options using BI. As noted above, BI can contribute to designing policy options (and implementing them, though this is not part of the IA process). These options can take the form of behavioural remedies, or nudges, or can be more traditional policy instruments, like regulation. Either way, BI can help design the policy instrument so that it addresses the target behaviour most effectively.

Pre-test policy options. Applying BI to policy-making is more than introducing a more nuanced understanding of behaviour. It is also about using experimental methodology to pre-test policy initiatives before they are rolled out (Lunn, Citation2014). Policies that fail to meet their objectives are expensive policies. Therefore, it makes sense to devote some resources to increasing the chance that they will succeed.

On this last point, the Better Regulations guidelines do not put forward a single best method for observing and testing behaviour. Instead, they claim that the research question should determine the best method. In so doing, they sidestep one of the criticisms of BI as currently applied to policy-making, namely its over-reliance on experimental methodology (Whitehead et al., Citation2017). In some instances, mixed methods will be appropriate to uncover relationships between the different elements of complex research questions, and even behavioural data linking can be pursued.Footnote7

In practice, however, the Better Regulations guidelines presents the following methods as options for policy officers seeking to observe behaviour and test policy options empirically.

Literature reviews. An often-undervalued method of empirical research, which can prove invaluable in helping identify the value of a behavioural approach. Should be conducted before any other empirical work.

Qualitative research. Typically comprising focus groups, interviews and some sort of participant observation, often used in preliminary phases of research to better understand the underlying causes of behaviour.

Surveys. The social research method in policy-making par excellence, also useful in behavioural studies, with a notable limitation, namely that it records what people say they do, not what they actually do.

Experiments. The method most commonly associated with BI. These seek difference in behaviour between people assigned to different groups, who are exposed to a different situation. This should account for differences in behaviour, if any.

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Also commonly associated with BI, these are interventions, using an experimental method, in real-life settings.

In the EC, behavioural studies using these methodologies are either conducted in-house by the JRC or outsourced. In the latter case, the JRC provides expert support, monitoring, reviewing and controlling the quality of the outsourced studies. These studies are publicly available and can be accessed through the EC website.Footnote8

5. Challenges and opportunities

While the use of BI in the policy-making process has grown in the EC, it is still not the norm. Ideally, the whole process would include BI in a more systematic and timely fashion. BI should complement and shape policy-making, rather than being an alternative approach to other interventions. They should inform more comprehensive policy approaches, combined with regulation and financial incentives. The more behavioural knowledge spreads across policy areas, the more policy integration would succeed in developing comprehensive policy approaches. To design effective behavioural interventions, BI experts need to have a good understanding of policy implementation and identify the policy instruments available to reach the desired outcomes.

Currently, the use of BIs in the EC can be described as a ‘centralised’ model (Mukherjee & Giest, Citation2020). The CCBI holds the expertise on BI and interacts bilaterally with other DGs at different stages of the policy cycle. For what concerns responding to policy needs, a DG can formally request the CCBI to consider a behavioural approach for their policy initiative. This often comes at the early stages of planning a policy initiative (as an input to the Impact Assessment). At times, however, DGs request input into their policy proposals at inter-service consultation, which is the procedure for requesting the formal opinion of other DGs. Introducing BI at this stage of the process, however, does not allow for a tailored empirical input, since there is not enough time to conduct a behavioural study. In order to make sure that behavioural evidence is interpreted correctly and behavioural interventions are used appropriately within the EC, consultation with BI experts should happen throughout the different stages of the policy process, as illustrated in section 4.1. The effective application of BI depends, indeed, on the correct interpretation of scientific findings and the appropriate use of empirical evidence (Kuehnhanss, Citation2019). A better option could be a mixed model, where the CCBI works as reference point, but behavioural capacity is also present in the DGs where BIs are more relevant and commonly used. Here BI can be metabolised, translated and contextualised by policy-makers (Feitsma, Citation2019). The CCBI is working in this direction by developing a network of policy-makers (BI Champions) who are knowledgeable on, or at least aware of, the potential of BI.

Introducing behavioural capacity in the DGs also aims at effectively communicating to policy-makers that behavioural science goes beyond nudging, and that they should move towards a more comprehensive approach. Nudges are cost effective, not very controversial and can be relatively successful. This might tempt policy-makers to substitute conventional regulation with nudges when political or budget constraints make other approaches less feasible. Admittedly, nudging is by far the best-known and most influential way of introducing BI into policy-making. It lies at the core of many governments’ attempts at shaping and governing human behaviour (Feitsma, Citation2019; Whitehead et al., Citation2017). However, it is only one way. Focussing exclusively on it paints a caricature of the behavioural turn in public policy and undermines the diversity of possible approaches (Feitsma, Citation2018).

One of the main challenges of applying behavioural science to policy is to avoid the use of BI with an ideological and pre-conceptual approach, exploiting the relative high acceptance of nudging as a low-cost tool. The role of BI in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic is a good example of how difficult it is to find the right balance in the application of behavioural science. On one hand, behavioural principles and interventions are undoubtedly helpful in influencing and encouraging behaviours such as washing hands or social distancing. On the other, the over-reliance on, or the misuse of, this approach can be very risky and can damage the credibility and reputation of the whole field. This risk holds for every scientific approach or theory, but BI are particularly subject to abuse or misapplication because behavioural evidence is easy to grasp and results are often quite intuitive. This is why practitioners in this field should always adopt a rigorous methodological approach and never oversell the potential of behavioural interventions. In addition, applying BI to policy is more than just knowledge transfer (as in a ‘supply push’ archetype; Knight & Lyall, Citation2013). This is particularly true because policy-makers generally do not have a background in behavioural sciences.

The CCBI has envisaged a number of initiatives in the short and medium term to ensure good practice in the application of BI within the EC: these are not only meant to foster a holistic behavioural approach to policy making, but also to anticipate and resolve challenges that are common to BI policy-making.

5.1. Widening the scope of BI at the EC

The application of BI at the EC should go beyond consumer protection towards more interventions aimed at collective behaviours (Feng et al., Citation2018). BI can effectively contribute to the new priorities of the EC, aimed at leading the transition to ‘a fair, climate-neutral, digital Europe’.Footnote9 The current use of BI to inform policies on gender discrimination in the labour market and vaccine hesitancy goes in this direction. The same applies to encouraging the use of BI in environmental policy. The CCBI has consolidated collaborations with DGs in the domain of consumer protection, financial investment, health, agriculture, and energy. However, relations with other policy areas – such as employment, structural reforms, environment, education, development and cooperation – are still not fully developed and will need to be actively promoted.

5.2. More exploratory and in-house research

The CCBI plans to increase its role in promoting evidence-based behavioural policy advice by conducting more anticipatory research on relevant topics, rather than limiting its contribution to responses to policy requests. This aspect of its work can be critical to how BI influence policy and goes into the direction of having an impact at the definition stage of the policy problem. In-house and anticipatory research also prevents the risk of running studies with a preconceived expectation on results, in the attempt to justify one policy or the other.

Following this line of reasoning, the JRC is creating its own platform to run on-line experiments independently, without resorting to external providers. This platform will be instrumental to the CCBI's long-term objective to incorporate BI in the whole policy cycle. It will allow the CCBI to conduct experiments with a certain degree of flexibility and to inform each phase of the policy process in a timely fashion. Less outsourcing will also ensure greater quality control over the whole data collection process.

5.3. Collaboration with Member States, private sector and academia

In order to widen its scope of action, including running RCTs, the EC needs to increase external collaborations. The CCBI has recently started direct collaboration with Member States on issues like taxation and sustainable finance. It sees opportunities to collaborate with national or local authorities to carry out field experiments. This would allow widening its coverage to areas such as employment and social benefits, which do not lie primarily under EU competence. While it is not in the mandate of the JRC to work with single Member States or local authorities, studies carried out to inform EU policy-making need to take into account heterogeneity within the EU. Coordinating collaborations on behavioural studies between Member States is a way to ensure representativeness. A network of national BI policy-makers exists in Europe and gathers once a year. The existence of such a network helps identifying opportunities for additional cross-national field studies. One such plan is currently being explored, and consists in following up an on-going online experimental study on vaccination hesitancy by a complementary field study across various countries.

Similarly, a new area of collaboration in which the CCBI sees good opportunities is the one with the private sector. Applying BI to research in collaboration with the private sector can illustrate how markets function and how decisions and strategies are taken by private agents including employers, employees and consumers. In this type of research, the unit of observation can be workers or the firm itself. The CCBI can reap benefits from establishing partnerships with firms and engaging in primary data collection.

Finally, the input from academic research into policy-making should increase. The JRC is ideally placed to build bridges between policy-making and academic research. Through the JRC, policy-makers are updated on the latest relevant scientific findings, and are often given the opportunity to inform researchers about evidence needed for policy. The DGs sometimes revert to expert advice from the academia on BI, but the CCBI wishes to go the extra mile by transforming the collaboration with academia into a more systematic and bidirectional exchange. In line with this aim, the CCBI is establishing Collaborative Doctoral Partnerships with a few selected universities.

6. Conclusion

The EC was one of the first public institutions to have behavioural evidence inform its policy decisions, with the JRC playing a key supporting role. This paper positioned the way BI are applied to policy-making in the EU in relation to existing work in this field. It also presented the progress towards mainstreaming BI in the EC in three stages (exploration, development and consolidation). It described how BI can be applied to the different phases of the EU policy-making process, explaining how they can contribute to defining the policy problem, understanding the reasons behind certain behaviours or phenomena, helping design policy interventions, and pre-testing policy options. The paper also assessed future challenges and opportunities for the application of BI to EU policy in general and to the work of the CCBI in particular.

Across all sections, the authors caution about managing behavioural insights. They can be successfully used to inform policy-making on a wide range of policy problems and to assess expected behavioural effects of traditional policy instruments (Gopalan & Pirog, Citation2017). However, they are only one of many tools available for supporting policy-making.

The considerations presented in this paper should also apply to other behavioural units, especially those in international organisations. They can help shape the vision for, and provide realistic expectations of, the work needed for the successful application of BI to the policy-making process.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Fabiana Scapolo, Alessandro Borsello and three anonymous reviewers for helping us improve the quality of this paper.

Disclosure statement

The authors are employees of Joint Research Centre (JRC), the European Commission's science and knowledge service, and are themselves alone responsible for the views expressed in the article, which do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the European Commission.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marianna Baggio

Marianna Baggio is a researcher at the European Commission's Joint Research Centre.

Emanuele Ciriolo

Emanuele Ciriolo is the head of the CCBI at the European Commission's Joint Research Centre.

Ginevra Marandola

Ginevra Marandola is a researcher at the European Commission's Joint Research Centre.

René van Bavel

René van Bavel is a senior researcher at the European Commission's Joint Research Centre.

Notes

1 Later, further research corroborated this finding, in particular in relation to commercial practices (e.g., see Trzaskowski, Citation2011; Purnhagen & van Herpen, Citation2017) and the EC guidelines (EC, Citation2016) explicitly acknowledged such evidence.

2 See for example the work of Beshears et al. (Citation2008), Johnson et al. (Citation1993, Citation2002), Johnson and Goldstein (Citation2003), Whan Park et al. (Citation2000).

3 Commission Decision of 24.03.2004 relating to a proceeding under Article 82 of the EC Treaty (Case COMP/C-3/37.792 Microsoft). Official Journal of the European Union.

4 Information and documentation on the stock-taking and review process can be found at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/news/better-regulation-principles-2019-apr-15_en.

5 More information on the Better Regulations guidelines and toolbox can be found here: https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-making-process/planning-and-proposing-law/better-regulation-why-and-how/better-regulation-guidelines-and-toolbox_en

6 Writ large, to include how they think and feel as well.

7 Behavioural data linking consists in connecting behavioural economics experiments, of any type, with longitudinal surveys, administrative data, biomarker banks, apps, mobile devices, scan data, and other big data sources (Andersen et al., Citation2015 and Galizzi & Wiesen, Citation2018).

8 See https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/consumers/consumer-protection/evidence-based-consumer-policy/behavioural-research_en (accessed 26.06.20).

9 The six priorities of the EC are: (i) A European Green Deal; (ii) A Europe fit for the digital age; (iii) An economy that works for people; (iv) A stronger Europe in the world; (v) Promoting our European way of life; and, (vi) A new push for European democracy.

References

- Afif, Z., Islan, W. W., Calvo-Gonzalez, O., & Dalton, A. G. (2019) Behavioural science around the world: Profiles of 10 countries (English) (eMBeD brief). Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

- Almeida, S. R., Lourenço, J. S., Dessart, F. J., & Ciriolo, E. (2017). Insights from behavioural sciences to prevent and combat violence against women: Literature review. JRC Working Papers, JRC103975.

- Andersen, S., Cox, J. C., Harrison, G. W., Lau, M., Rutström, E. E., & Sadiraj, V. (2015). Asset integration and attitudes to risk: Theory and evidence (Working Paper No. 2012-12). Atlanta, GA: Experimental Economic Center.

- Ariely, D., Loewenstein, G., & Prelec, D. (2003). “Coherent arbitrariness”: Stable demand curves without stable preferences. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 73–106. https://doi.org/10.1162/00335530360535153

- Berndt, C. (2015). Behavioural economics, experimentalism and the marketization of development. Economy and Society, 44(4), 567–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147.2015.1043794

- Beshears, J., Choi, J., Laibson, D., & Madrian, B. (2008). The importance of default options for retirement saving outcomes: Evidence from the United States. In S. J. Kay & T. Sinha (Eds.), Lessons from pension reform in the Americas (pp. 59–87). Oxford University Press.

- Carter, E. D. (2015). Making the blue zones: Neoliberalism and nudges in public health promotion. Social Science and Medicine, 133, 374–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.01.019

- Ciriolo, E. (2011, January). Behavioural economics in the European Commission: Past, present and future. Oxera Agenda. https://www.oxera.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Behavioural-economics-in-the-EC_1.pdf

- Della Vigna, S., & Linos, E. (2020). RCTs to Scale: Comprehensive evidence from two nudge units. unpublished paper.

- EC. (1992). Consumer policy in the European Community – An overview, Memo/92/68.

- EC. (1997). Directive 97/7/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 May 1997 on the protection of consumers in respect of distance contracts.

- EC. (2006). EU Regulation 1924/2006 on nutrition and health claims made on food.

- EC. (2008). Proposal for a Directive on consumer rights, 20008/0196 (COD).

- EC. (2010). Consumer decision making in retail investment services: A behavioural economics perspective.

- EC. (2011). Directive 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on consumer rights.

- EC. (2014a). Tobacco Products Directive, 2014/40/EU.

- EC. (2014b). Commission Recommendation of 14 July 2014 on principles for the protection of consumers and players of online gambling services and for the prevention of minors from gambling online, 2014/478/EU.

- EC. (2016). Guidance on the implementation/application of Directive 2005/29/EC on unfair commercial practices, SWD(2016) 163 final.

- Feitsma, J. N. P. (2018). The behavioural state: Critical observations on technocracy and psychocracy. Policy Sciences, 51(3), 387–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-018-9325-5

- Feitsma, J. N. P. (2019). Brokering behaviour change: The work of Behavioural Insights experts in government. Policy & Politics, 47(1), 37–56. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557318X15174915040678

- Feitsma, J. (2020). ‘Rationalized incrementalism’. How behavior experts in government negotiate institutional logics. Critical Policy Studies, 14(2), 156–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2018.1557067

- Feng, B., Oyunsuren, J., Tymko, M., Kim, M., & Soman, D. (2018). How should organizations best embed and harness behavioural insights? A playbook. Toronto: Behavioural Economics in Action at Rotman (BEAR) Report series.

- Frank, J.-U., & Purnhagen, K. (2015). Homo economicus, behavioural sciences, and economic regulation: On the concept of man in internal market regulation and its normative basis. In K. Mathis (Ed.), Law and economics in Europe, foundations and applications (pp. 329–366). Springer.

- Galizzi, M., & Wiesen, D. (2018). Behavioural experiments in health economics. In J. H. Hamilton, A. Dixit, S. Edwards, & K. Judd (Eds.), Oxford research encyclopaedia of economics and finance. Oxford research encyclopaedias. Oxford University Press.Retrieved 5 Apr. 2021, from https://oxfordre.com/economics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190625979.001.0001/acrefore-9780190625979-e-244.

- Gopalan, M., & Pirog, M. A. (2017). Applying behavioral insights in policy analysis: Recent trends in the United States. Policy Studies Journal, 45(S1), S82–S114. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12202

- Halpern, D. (2016). Inside the nudge unit: How small changes can make a big difference. WH Allen.

- Howells, G. (2005). The potential and limits of consumer empowerment by information. Journal of Law and Society, 32(3), 349–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6478.2005.00328.x

- Incardona, R., & Poncibò, C. (2007). The average consumer, the unfair commercial practices directive, and the cognitive revolution. Journal of Consumer Policy, 30(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-006-9027-9

- Ingold, J., & Monaghan, M. (2016). Evidence translation: An exploration of policy makers' use of evidence. Policy & Politics, 44(2), 171–190. https://doi.org/10.1332/147084414X13988707323088

- Johnson, E. J., Bellman, S., & Lohse, G. L. (2002). Defaults, framing and privacy: Why opting in–opting out. Marketing Letters, 13(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015044207315

- Johnson, E. J., & Goldstein, D. G. (2003). Do defaults save lives? Science, 302(5649), 1338–1339. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1091721

- Johnson, E. J., Hershey, J., Meszaros, J., & Kunreuther, H. (1993). Framing, probability distortions, and insurance decisions. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 7(1), 35–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01065313

- Jones, R., Pykett, J., & Whitehead, M. (2010, December). Big Society’s little nudges: the changing politics of health care in an age of austerity. Political Insight, 85–87.

- Knight, C., & Lyall, C. (2013). Knowledge brokers: The role of intermediaries in producing research impact. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 9(3), 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426413X14809298820296

- Kuehnhanss, C. R. (2019). The challenges of behavioural insights for effective policy design. Policy and Society, 38(1), 14–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2018.1511188

- Kuneva, M. (2008). Opening speech at the First European Commission Behavioural Economics Conference, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_08_660.

- Leggett, W. (2014). The politics of behaviour change: Nudge, neoliberalism, and the state. Policy and Politics, 42(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557312X655576

- Lourenço, J. S., Ciriolo, E., Rafael Almeida, S., & Troussard, X. (2016). Behavioural insights applied to policy: European Report 2016. EUR 27726 EN. https://doi.org/10.2760/903938

- Lunn, P. (2014). Regulatory Policy and Behavioural Economics. OECD Publishing.

- Mukherjee, I., & Giest, S. (2020). Behavioural Insights teams (BITs) and policy change: An exploration of impact, location, and temporality of policy advice. Administration & Society, 52(10), 1538–1561. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399720918315

- Oliver, A. (2015). Nudging, shoving, and budging: Behavioural economic-informed policy. Public Administration, 93(3), 700–714. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12165

- Purnhagen, K. (2015). Why do we need responsive regulation and behavioural research in EU internal market law? In K. Mathis (Ed.), European perspectives on behavioural law and economics (pp. 51–69). Springer.

- Purnhagen, K. P., & van Herpen, E. (2017). ‘Can bonus packs mislead consumers? A demonstration of how behavioural consumer research can inform unfair commercial practices law on the example of the ECJ’s Mars judgement’. Journal of Consumer Policy, 40(2), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-017-9345-0

- Sunstein, C. R., Reisch, L. A., & Kaiser, M. (2019). Trusting nudges? Lessons from an international survey. Journal of European Public Policy, 26(10), 1417–1443. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1531912

- Taleb, N. N. (2010). The black swan: The impact of the highly improbable. Penguin.

- Thaler, R. H. (2009, August 4). Markets can be wrong and the price is not always right. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/efc0e92e-8121-11de-92e7-00144feabdc0

- Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press.

- Troussard, X., & van Bavel, R. (2018). How can behavioural insights be used to improve EU policy? Intereconomics, 53(1), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-018-0711-1

- Trzaskowski, J. (2011). Behavioural Economics, neuroscience, and the unfair commercial practises directive. Journal of Consumer Policy, 34(3), 377–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10603-011-9169-2

- Whan Park, C., Jun, S. Y., & MacInnis, D. J. (2000). Choosing what I want versus rejecting what I do not want: An application of decision framing to product option choice decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(2), 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.37.2.187.18731

- Whitehead, M., Jones, R., Lilley, R., Pykett, J., & Howell, R. (2017). Neuroliberalism: Behavioural government in the 21st century. Routedge.